What Exactly is a Self-Portrait? A Deep Dive into the Artist's Mirror

Ever wondered why artists turn the canvas inward? This comprehensive guide explores the rich history, diverse forms, and profound psychology behind self-portraits, offering a unique, personal perspective on this timeless artistic endeavor. Discover why it's more than just a selfie.

The Self-Portrait: A Comprehensive Guide to the Artist's Enduring Mirror – Unveiling Humanity's Inward Gaze

You know, sometimes I find myself just staring into a mirror. Not to fix my hair or check for rogue breakfast crumbs (though, let's be honest, that happens too!), but just… looking. It’s a habit I picked up early on, almost unconsciously, a subtle inquiry into the face staring back. What story does it tell today? What lines have deepened? What fleeting emotion flickers in the eyes? I spend a lot of time observing the lines, the shadows, the fleeting expressions that cross my face when a thought sparks or an emotion stirs. It's a strangely intimate act, isn't it? That quiet, unadulterated moment of self-reflection, a deep, almost primal desire to understand the 'self'. It's precisely this primal urge, this unwavering human fascination with identity, that serves as the enduring bedrock of the self-portrait, a genre as old as humanity's self-awareness itself – and a profound subject we're about to explore in exhaustive detail. We're talking about more than just a picture; we're delving into a visual autobiography, a philosophical statement, and a historical record all rolled into one.

This genre is far more than a mere vanity project or a casual 'selfie' in paint or clay; it's a profound, often vulnerable, conversation an artist engages in with themselves, captured and presented for the world to witness. It's their unique way of declaring, "This is me, at this precise moment, perceived through my very own eyes." This emotional raw intensity is what draws us in, isn't it? Indeed, it touches upon deep philosophical questions about perception, existence, and the very nature of self, acting as a visual testament to the human condition itself. And what an utterly fascinating journey this particular artistic genre has undertaken throughout the sprawling landscape of art history! From ancient whispers of presence in cave art to the bold, fragmented declarations of modernism, the self-portrait continually reinvents itself, mirroring our evolving understanding of who we are, and who we think we are.

From ancient civilizations subtly asserting presence to modern masters dissecting identity, the self-portrait has consistently mirrored humanity's evolving self-awareness, making it an invaluable lens through which to view human history and psychology. It's a journey from the pragmatic to the profound, a visual record of our collective and individual quests for meaning and recognition. Understanding self-portraiture isn't just about art history; it's about understanding ourselves.

As an artist, I've spent countless hours in that internal dialogue, both with myself and with the history that informs my work. And let me tell you, the self-portrait is a rich, intricate tapestry, woven with threads of ego, introspection, and societal reflection. So, let's peel back the myriad layers and truly delve into what it signifies when an artist chooses to turn their perceptive gaze inward, making themselves both the creator and the subject. We'll explore its rich history, its deep psychological motivations, and its surprising evolution across diverse mediums, aiming to make this the ultimate, most comprehensive guide to understanding self-portraiture you'll find anywhere. Seriously, by the time you're done here, you'll be seeing yourself (and every artist's 'self') in a whole new light, and perhaps even feel inspired to pick up a brush or a camera yourself.

Key Takeaways: What You'll Discover About Self-Portraits – Your Roadmap to Understanding

Aspect | Traditional Definition | Deeper Meaning (Artistic Intent) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Concept | An artist's depiction of themselves. | A deliberate act of introspection, self-discovery, and visual storytelling by the artist. |

| Historical Role | Signature, skill demonstration, available model. | Evolution from status symbol to psychological exploration and social commentary. |

| Purpose | Documentation, practice, legacy. | Vehicle for identity exploration, emotional processing, and universal human inquiry. |

| Mediums & Styles | Primarily painting, drawing, sculpture. | Expansive, including photography, performance, digital art, and abstract representations of inner states. |

| Distinction from 'Selfie' | Intentional, introspective, artistic. | Casual, often for immediate sharing, less focused on deep conceptual or emotional exploration. |

| Key Questions Explored | Who am I? What do I look like? | How do I feel? What do I believe? How do I fit into the world? What is the human condition? |

| Audience Impact | Recognition, appreciation of skill. | Invitation to empathy, challenge to societal norms, shared human experience. |

| Artistic Movements | Representational, academic styles. | Adapted to every major art movement, from Cubism's fragmentation to Expressionism's raw emotion. |

| Influence on Society | Reflection of individual genius. | Powerful tool for social commentary, challenging norms, and asserting marginalized identities. |

| Evolving Forms | Traditional mediums for physical likeness. | From performance art to digital avatars and abstract expressions of inner states. |

More Than Just a Selfie: Defining the Self-Portrait – A Core Concept

At its simplest, a self-portrait is an artistic representation of an artist, created by that very artist. Sounds straightforward, right? But like many things in art, the simplest definitions often hide the deepest complexities. And for me, an artist who often tries to capture fleeting emotions in abstract forms, that "simplest definition" is just the beginning of a rabbit hole. The magic, and indeed the profound complexity, resides in that seemingly simple phrase: 'artistic representation.' This isn't just about snapping a quick photo, mind you; it’s about deep intent, about quiet introspection, and about a series of intensely deliberate artistic choices that coalesce into a singular vision. It’s a purposeful act of creation, not merely a spontaneous capture. Think of it as a meticulously crafted visual essay on the self, rather than a fleeting diary entry. This distinction is crucial, as it elevates the self-portrait from casual observation to profound artistic inquiry, often touching on deep philosophical questions of phenomenology – how we experience and interpret the world, including ourselves. It's about a deliberate act of choosing how to present oneself, acknowledging that the 'self' is not a fixed entity but a dynamic, subjective experience. This inherent subjectivity is precisely what makes each self-portrait a unique universe, an intimate glimpse into one person's world, filtered through their own consciousness, and presented for others to ponder. It challenges the viewer to look beyond the surface, inviting a deeper engagement with the artist's inner landscape and their chosen mode of representation. It’s a profound act of visual philosophy, where the artist grapples with identity, perception, and existence itself, inviting you to join in the inquiry.

The self-portrait, in essence, is a profound act of self-narration. It's the artist's opportunity to define, or redefine, their story. This can range from a straightforward visual record to a complex psychological exploration, or even a performative act of identity. This visual storytelling can be a powerful antidote to external narratives, allowing the artist to assert their own truth. It's a way of saying, "You might think you know me, but this is how I see myself – my triumphs, my vulnerabilities, my evolving sense of who I am." This becomes especially vital for artists from marginalized groups, where self-portraiture can become a potent act of reclaiming agency and challenging dominant stereotypes, asserting a voice that might otherwise be silenced. It's a declaration of existence and self-worth.

This deliberate act of self-narration, whether overt or subtle, is what truly sets the self-portrait apart from a mere likeness. It demands intention, a dialogue between the artist's inner world and the external canvas, allowing for profound declarations of identity, belief, and emotion that transcend simple physical features.

This deliberate act of self-narration, whether overt or subtle, is what truly sets the self-portrait apart from a mere likeness. It demands intention, a dialogue between the artist's inner world and the external canvas, allowing for profound declarations of identity, belief, and emotion that transcend simple physical features. It’s a visual autobiography, but one deeply intertwined with philosophy – specifically, phenomenology, the study of consciousness and subjective experience. It asks: How do I experience being myself, and how can I translate that experience into a visual form for you to experience?

The Artist's Gaze: Observer, Subject, and Narrator – A Multi-faceted Mirror

When an artist creates a self-portrait, something truly fascinating happens. They step into multiple roles simultaneously: they are the observer, studying their own features with an almost clinical detachment; they are the subject, presenting themselves to the world; and crucially, they are the narrator, shaping the story of that observation through their chosen medium. This multi-layered perspective is what gives self-portraits their unique power. It’s not just what is seen, but how it is seen, and why it is being shown. It’s a dance between objectivity and radical subjectivity, a visual testament to the artist's singular vision. My own journey with abstract art often feels like this, a navigation of observer and subject, where the canvas becomes a mirror to my internal landscape, reflecting not just what I see, but what I feel and believe at that moment. It's a constant negotiation, a dance between revealing and concealing, much like the careful staging of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, that artists have employed for centuries to sculpt a figure from the void, drawing out its emotional core. It's a profound self-dialogue, a visual soliloquy that invites the viewer into the artist's most intimate reflections.

Beyond Resemblance: Capturing the Inner World

Think about it: when I create something, anything, whether it's an abstract swirl of colors or a meticulously rendered figurative piece, I'm making hundreds of decisions. What colors to choose? What lines to emphasize? What mood do I want to evoke? When the subject of that intense scrutiny happens to be me, those decisions become incredibly personal, almost raw. Every brushstroke, every carefully placed shadow, every deliberate distortion tells a story—not merely of what I look like on the surface, but of what I feel, what I think, what I project from the deepest parts of myself. It’s a dialogue between the internal and external, an attempt to bridge the visible and the invisible through artistic form. I often find that my most honest self-portraits, whether literal or abstract, emerge from a place of deep vulnerability, pushing beyond mere aesthetics to reveal a deeper truth about the complex, often contradictory, nature of self. It's an act of courageous honesty, a visual autobiography in the making, where every choice, from the tilt of the head to the background elements, contributes to the overarching narrative.

This kind of deep dive into the self through visual language is what allows the self-portrait to transcend mere depiction, transforming into a philosophical statement on existence, a meditation on the very fabric of being.

It’s a truly unique form of communication, a potent window into the artist's soul that extends far beyond mere physical resemblance. It's almost as if the artist is embarking on a philosophical inquiry, asking themselves, "Who am I, really?" and attempting to answer that monumental question on canvas, film, or through any chosen medium. And often, it's not just the face that speaks volumes; the posture, the gesture, the subtle tilt of the head, and even the surrounding elements can convey a powerful narrative about the artist's inner world, much like interpreting body language in portrait art in a broader sense. This intense focus distinguishes it from general portraiture, where the artist primarily interprets another's identity. In a self-portrait, the artist is both the observer and the observed, leading to a unique kind of subjective truth that is rarely achieved when depicting others. It's a mirror held up to the soul, not just the face. And speaking of bridging the visible and invisible, it's often in this introspective process that artists grapple with universal concepts, even touching on the psychology of color in abstract art to subtly convey their inner world without explicit representation, exploring fundamental questions of consciousness, existence, and the very fabric of identity. It's a profound self-examination that resonates universally, revealing the subtle interplay between the conscious and unconscious self. I mean, how often do you really stop to consider the hidden aspects of yourself, the parts that surface in dreams or unexpected moments of intuition? That's what a deep self-portrait can tap into.

A Storied Past: The Evolution of Self-Portraits Through Art History – A Visual Timeline

Oh, the history of self-portraits is a rich, intricate tapestry, truly. And trust me, it wasn't always about deep psychological exploration, mind you. In the very beginning, the artist's depiction of themselves was often about proving skill, a way to 'sign' one's work, or even just the simple practicality of having a cheap, readily available model (namely, oneself!). The journey from a humble mark to a profound existential statement is one of art history’s most compelling narratives. It’s a journey that continually reminds us that art is not just about aesthetics, but about deep connection, profound inquiry, and the endless unfolding of human identity.

Oh, the history of self-portraits is a rich, intricate tapestry, truly. And trust me, it wasn't always about deep psychological exploration, mind you. In the very beginning, the artist's depiction of themselves was often about proving skill, a way to 'sign' one's work, or even just the simple practicality of having a cheap, readily available model (namely, oneself!).

It's fascinating to think of artists throughout history, from those subtly hinting at their presence to those boldly asserting their identity, all contributing to this incredible visual conversation.

Early Origins and Development: Tracing the Glimmers of Self-Representation

The Echoes of Antiquity: Prehistoric and Ancient Glimmers of Self-Assertion

Even before the formal concept of 'self-portraiture' existed, humanity has shown an innate desire to leave its mark, to assert individual presence. Think of the handprints on cave walls dating back tens of thousands of years – a primal 'I was here' statement, perhaps the very first abstract self-portraits! While not portraits in the modern sense, these early marks represent a fundamental assertion of self. As societies grew more complex, particularly in ancient Egypt, artists or artisans might subtly incorporate their likeness into the elaborate tomb paintings or sculptures they created for pharaohs and nobles. These weren't center stage, of course, but often appeared as smaller figures amongst the main narrative, a quiet claim of authorship and a hope for immortality through their craft. It was a humble, yet persistent, whisper of individual identity within a vast, collective undertaking, reflecting the enduring influence of ancient traditions. We also see this in ancient Mesopotamian and Indus Valley civilizations, where personal seals or small figures might hint at individual representation, even if the primary focus was on deities or rulers, suggesting a universal human impulse to leave a personal trace, however subtle. This subtle inclusion of the artist’s hand in their work is a fascinating precursor to the overt self-portrait.

Ancient Greek and Roman Self-Representation: Beyond the Ideal

Even in cultures obsessed with idealized forms, like ancient Greece and Rome, there are fascinating hints of self-representation. While direct self-portraits were rare, artists might sign their works with an image of themselves, or more intriguingly, subtly insert their own features into the faces of minor characters or mythological figures. Think of it as a sly, artistic wink—a way for the creator to claim authorship and a fleeting moment of personal presence in a world dominated by gods and heroes. Roman funerary busts, while often commissioned by patrons, sometimes depict individuals with such distinctive, almost unflattering realism that one can imagine artists applying a similar unflinching gaze to their own features when the opportunity arose. It’s a far cry from the emotional depth of a Rembrandt, but the seed of self-acknowledgement was certainly there.

During the Medieval period, particularly in illuminated manuscripts, artists sometimes inserted small, often devotional, self-representations. These were less about ego and more about humble prayer or signing their work within the sacred narrative, a visual petition for spiritual grace. We even see echoes of early self-representation in religious frescoes, where artists might include themselves as humble witnesses to sacred events, often in the bottom corners or obscured positions, sometimes even gazing out at the viewer, subtly breaking the fourth wall. It was a slow burn, this idea of the artist as a worthy subject. Even in the very early modern period, you find artists like Jan van Eyck or Robert Campin subtly inserting their likenesses into religious scenes, often as onlookers or even as patron saints. Van Eyck's 'Arnolfini Portrait' famously includes a mirror reflecting the artist himself, a meta-commentary on presence and perception, an early example of the artist consciously engaging with their own image within a larger narrative. It's a testament to a growing sense of individual authorship, a quiet but persistent claim of 'I was here, I made this.' This journey, from subtle inclusion to explicit self-assertion, would eventually lead to the vibrant individualism of the Renaissance, much like how the influence of Byzantine art laid critical groundwork for later developments in artistic realism and emotional depth.

The Northern Renaissance: A New Era of Self-Consciousness – Dürer's Bold Declarations

It was in the Northern Renaissance that the self-portrait truly began to take its distinct form, moving beyond mere anecdotal presence to a focused exploration of individual identity. Artists like Albrecht Dürer (who we mentioned earlier) were pioneers in this, transforming the self-portrait into a vehicle for intellectual and spiritual assertion. His iconic self-portraits are not just records of his appearance but profound statements about his status as an artist and thinker. Dürer's meticulous detail and psychological depth set a new standard, influencing generations to come. In the Low Countries, artists such as Rogier van der Weyden and Hans Memling also created subtle yet powerful self-portraits, often embedded within larger altarpieces, hinting at the artist's burgeoning self-awareness and importance within the commission.

The Renaissance Awakening: Skill, Status, and the Dawn of Individualism

By the Northern Renaissance, however, something truly shifted. Artists like Albrecht Dürer, bless his meticulous soul, were creating incredibly detailed and psychologically insightful self-portraits. His 1500 self-portrait, for instance, presents him frontally, almost Christ-like, a bold statement not just of his technical mastery but of his intellectual and spiritual status, asserting the artist's elevated position in society. He used himself as a subject to experiment with new techniques, perfect anatomy, and explore his own identity, setting a powerful precedent for generations to come, elevating the genre to a serious artistic endeavor. This was a radical act of self-assertion, placing the artist firmly at the center of their own narrative, a testament to the burgeoning humanist ideals of the era.

In the Italian Renaissance, the humanist focus, celebrating individual achievement and potential, provided fertile ground for the self-portrait to flourish. We see artists like Leonardo da Vinci incorporating his likeness into anatomical studies, or the enigmatic Giorgione potentially including himself in 'The Three Philosophers' – subtle assertions of intellectual and artistic presence. Artists like Raphael and Michelangelo also made subtle or implied self-references in their grand compositions, solidifying the artist's status as a genius worthy of recognition and remembrance. The self-portrait moved from a humble signature to a profound exploration of identity and artistic prowess, marking a significant evolution in the artist's self-perception.

The Unseen Gaze: Pioneering Female Self-Portraitists – Breaking Through Barriers

While much of art history has traditionally focused on male masters, the Renaissance also saw the rise of extraordinary female artists who fearlessly turned the canvas inward. Think of Sofonisba Anguissola or Artemisia Gentileschi. Anguissola, an Italian Renaissance painter, created a number of captivating self-portraits, often depicting herself in everyday settings or with family members, subverting expectations and asserting her intellectual and artistic prowess in a world that often limited women to domestic roles. Gentileschi, a formidable Baroque painter, used her self-portraits (like her powerful "Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting") not just to display skill, but to bravely address personal trauma and societal constraints, transforming personal suffering into universal statements of resilience. These artists, through their self-portraits, weren't just painting faces; they were battling for recognition, challenging norms, and forging a path for future generations of women in art, asserting their place in a world often hostile to their ambitions. Other notable female self-portraitists include Lavinia Fontana, known for her detailed and expressive self-portraits, and Elisabetta Sirani, whose technical skill and assertiveness challenged conventions of her time. Their contributions are a vital, though often under-recognized, part of the self-portrait's rich history, demonstrating resilience and breaking ground in a male-dominated art world. These artists used their self-portraits not just as artistic endeavors but as powerful statements of intellectual capability and professional legitimacy.

The Baroque and Rococo Eras: Drama, Emotion, and Self-Assertion – From Grandiosity to Intimacy

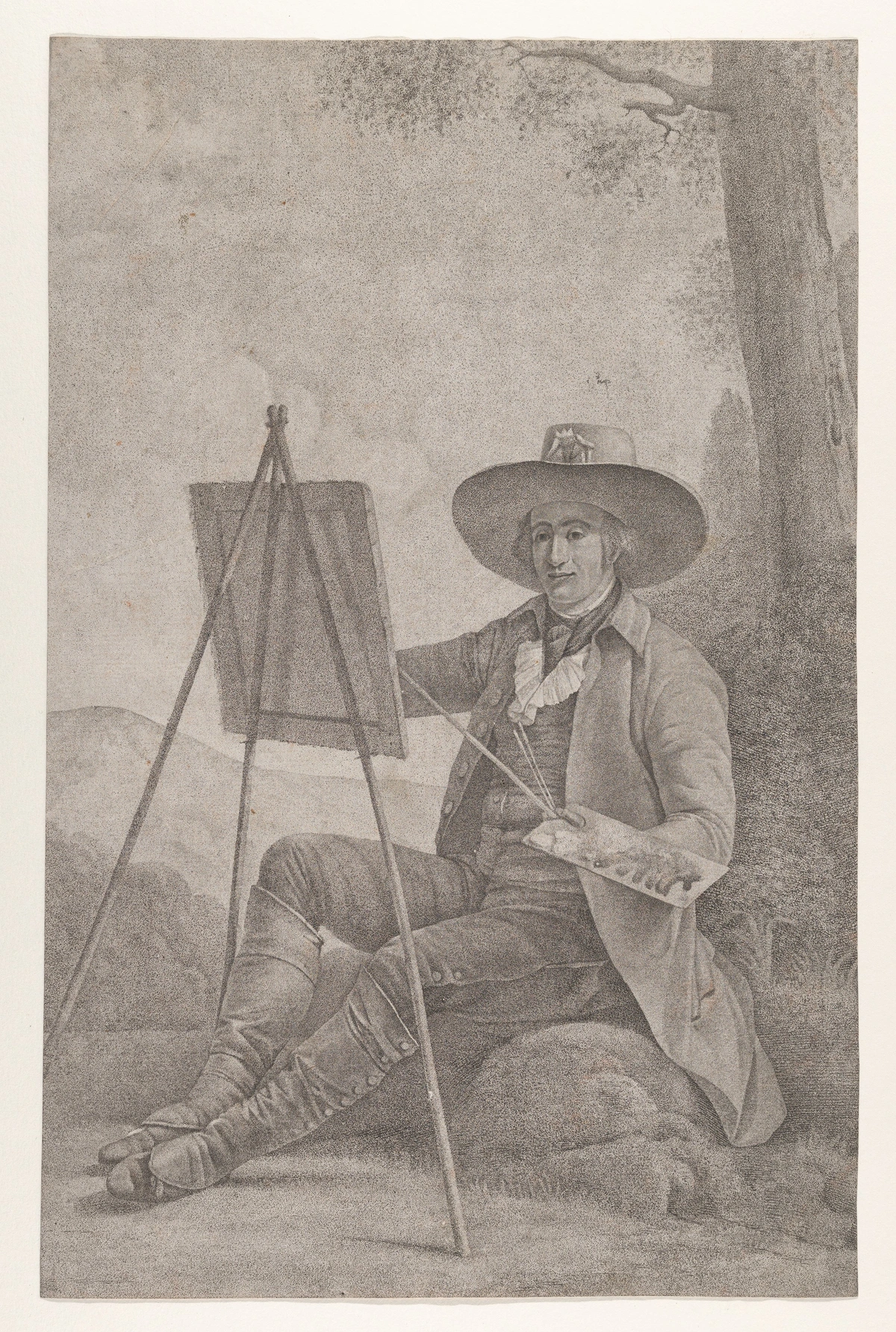

Moving into the Baroque period, self-portraits took on a new theatricality and emotional intensity. Artists like the aforementioned Artemisia Gentileschi and the monumental Rembrandt van Rijn explored the raw depths of human emotion through their own visages. Rembrandt, especially, used his face as a lifelong canvas for existential inquiry, charting the ravages of time and fortune with unflinching honesty. The Baroque emphasis on drama, light, and shadow made the self-portrait a perfect vehicle for exploring the inner turmoil and spiritual struggles of the artist. During this period, self-portraits often served to elevate the artist's status, placing them among nobles and patrons. The "artist in the studio" became a popular motif, showcasing not just the artist's face, but also their tools, their environment, and their intellectual pursuit. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci (though earlier, his influence carried through) subtly inserted their likeness into larger works or created singular self-portraits that exuded intellectual gravitas, a quiet assertion of genius. Think of the sheer audacity in that! Beyond the grandiosity, the Baroque era also saw a deeper dive into human vulnerability, with artists like Judith Leyster creating compelling self-portraits that exuded confidence and skill while subtly challenging gender roles, presenting herself not just as an artist, but as an individual of intellect and agency, adding a crucial layer to the evolving narrative of self-representation.

By the Rococo era, with its lighter, more decorative aesthetic, artists like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun created elegant, confident self-portraits that often depicted them at work, subtly asserting their professional status and artistic grace within courtly circles, even while conforming to the prevailing stylistic trends. Other significant Baroque self-portraitists include Peter Paul Rubens, who presented himself with aristocratic elegance, and Diego Velázquez, who famously inserted himself into his monumental 'Las Meninas,' a clever act of self-assertion within a royal portrait. The Rococo, with its focus on intimacy and charm, saw artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin creating humble yet profound self-portraits that captured everyday moments with quiet dignity. These works often presented a more approachable, less overtly dramatic self, reflecting the changing social landscape and artistic tastes of the era. It was a subtle, yet powerful, assertion of the artist's place within the domestic and intellectual sphere.

The 17th Century: Golden Age of Introspection and the Artist's Evolving Status

Speaking of individual journeys, sometimes I imagine these historical figures, easel set up, peering into a small mirror, just trying to capture that fleeting moment of their own existence. It’s a very human endeavor, isn't it? A quiet, intense conversation between the artist and their reflection, translating the ephemeral into the enduring.

The 17th century, particularly the Baroque era, witnessed an explosion of self-portraiture, with artists turning to their own image for profound psychological exploration. This was the era of Rembrandt van Rijn, who, bless his prolific soul, made hundreds of self-portraits throughout his life. I mean, can you imagine dedicating your entire artistic life to documenting your own journey? He used them almost like a visual diary, a profound visual record documenting his aging, his changing fortunes, and his evolving emotional states. For him, the self-portrait was a continuous, lifelong experiment in capturing the nuanced, often raw, tapestry of the human condition, with himself serving as the most accessible, and perhaps most honest, subject. His explorations went beyond mere likeness, delving into the depths of human emotion, much like his profound work on pieces like The Night Watch. It’s a masterclass in vulnerability and unflinching self-examination. But Rembrandt was not alone. Artists like Johannes Vermeer, though less prolific in self-portraits, is believed by some to have included himself in paintings like 'The Art of Painting,' subtly asserting his presence and mastery. Artemisia Gentileschi, a formidable Baroque painter, used her self-portraits (like her powerful 'Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting') not just to display skill, but to bravely address personal trauma and societal constraints, transforming personal suffering into universal statements of resilience.

The Enlightenment and Neoclassicism: Reason, Self-Improvement, and Grandeur – The Thinking Artist and Entrepreneur

With the Enlightenment, the focus shifted towards reason, individualism, and the pursuit of knowledge. Self-portraits of this era often depicted artists as intellectuals, engaging in study or presenting themselves with a calm, rational dignity. Neoclassicism, following the grand ideals of ancient Greece and Rome, saw artists like Jacques-Louis David creating self-portraits that conveyed a sense of moral integrity and classical restraint, often with a hint of stoicism. It was a time when the artist's intellect was as celebrated as their craft, and self-portraits reflected this new emphasis on the thinking, rational individual, subtly asserting their societal role as thinkers and innovators. This was also an era where artists began to assert more independence from traditional patronage, increasingly seeing themselves as professionals and even entrepreneurs. We also see artists like Angelica Kauffman creating self-portraits that combined grace with intellectual seriousness, navigating the expectations for female artists in a period of grand historical narratives, and subtly asserting their intellectual prowess in a male-dominated academy. Her works embody the Enlightenment ideals of reason and self-improvement, even for women artists, and subtly reflect a growing sense of professional autonomy.

Romanticism and Realism: Emotion Unbound and the Everyday Self – Inner Worlds and Social Statements

Later, with movements like Romanticism and Realism, artists like Francisco Goya, with his intense, introspective self-portraits, reflected not only his own internal struggles but also the tumultuous political landscape of his time, often imbued with a sense of the sublime or the tragic. And then there was Gustave Courbet, who used his self-portraits to challenge academic norms and assert his place as an ordinary individual, even a rebel, often depicting himself in unglamorous, everyday scenarios, championing the common man. It was a defiant stance against idealized artistic conventions, a raw and unvarnished glimpse into the artist's authentic self, whether filled with Sturm und Drang or the quiet dignity of labor. Other Romantic artists like Eugène Delacroix created dramatic self-portraits filled with passion and exoticism, while Realists like Édouard Manet offered cool, detached self-studies that focused on observation rather than overt emotion, challenging the idealism of the past with a direct engagement with contemporary life. Both movements used the self-portrait to either heighten personal drama or ground it in gritty reality, forging new paths for self-expression. I often wonder, what were they really thinking as they gazed into that mirror, knowing the world was changing so rapidly around them?

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: The Subjective Gaze and Inner Turmoil – Light, Color, and Psyche

Then came Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, where the focus shifted dramatically. Artists like Vincent van Gogh poured their raw, often turbulent, emotions onto the canvas, using their own faces as an urgent vehicle for intense expression, driven by a profound desire to communicate his inner world. It became less about meticulous likeness and much more about capturing raw feeling, about showing the inner turmoil or fleeting ecstasy that defined their moment. It’s a shift from 'how I appear' to 'how I feel', a deliberate focus on the artist's subjective perception of themselves in a particular instant of light and emotion. Paul Cézanne, with his numerous self-portraits, used himself as a subject to rigorously experiment with form and color, pushing the boundaries of representation towards what would become Cubism. His self-portraits are less about psychological revelation and more about the formal problems of painting, using his own visage as a landscape for formal innovation. Claude Monet, while not known for extensive self-portraiture, occasionally depicted himself within his landscapes, emphasizing the artist's subjective interaction with nature, while Paul Gauguin used his self-portraits to explore symbolic and spiritual self-identity, often portraying himself in exotic or allegorical guises. It’s almost as if they were saying, "My inner world is as important as the external one, and I'll use every color and brushstroke to prove it!"

Modern and Contemporary Perspectives

Era/Movement | Key Characteristics of Self-Portraits | Example Artists (and why) |

|---|---|---|

| Renaissance/Baroque | Assertion of artist's status, skill demonstration, early psychological depth. Often formal, depicting the artist in their studio or alongside patrons. | Albrecht Dürer: Early psychological insight, technical mastery. Rembrandt van Rijn: Lifelong visual diary, deep emotional exploration, aging. |

| Romanticism/Realism | Emphasized individuality, emotion, and sometimes social critique. More focus on the artist's personal narrative and lived experience. | Gustave Courbet: Portraying himself as an outsider, a common man. Francisco Goya: Introspective, reflecting personal demons and societal turmoil. |

| Impressionism/Post-Impressionism | Focus on subjective experience, light, color, and raw emotion. Less about objective likeness, more about the artist's internal state. | Vincent van Gogh: Intense emotional expression, vibrant color. Paul Gauguin: Exploring symbolic self-identity, spiritual quest. |

| Expressionism | Radical distortion of reality to convey emotional truth. Often stark, unsettling, and focused on inner psychological states. | Edvard Munch: Depicting anxiety and existential dread. Egon Schiele: Raw, confrontational, exploring vulnerability and sexuality. |

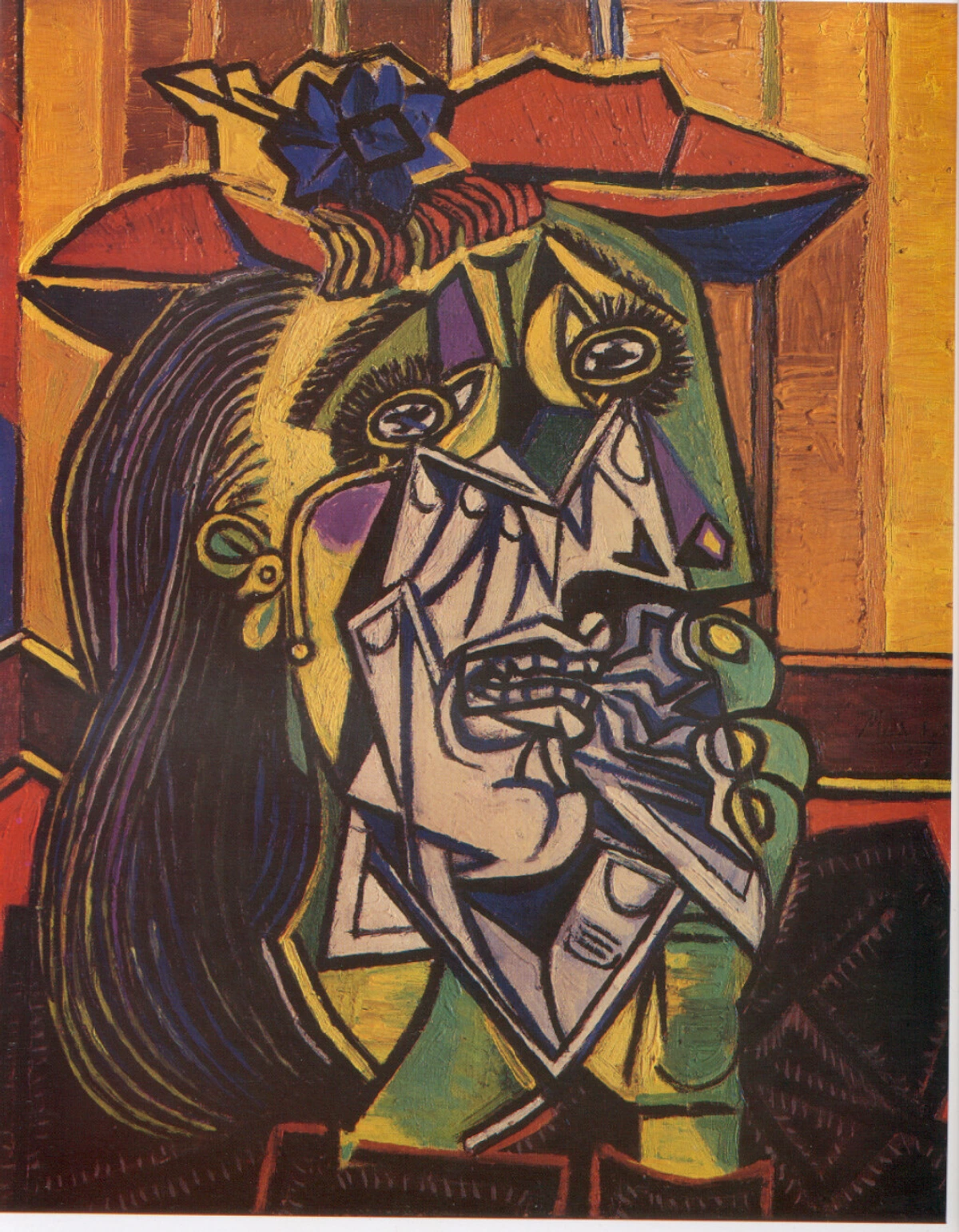

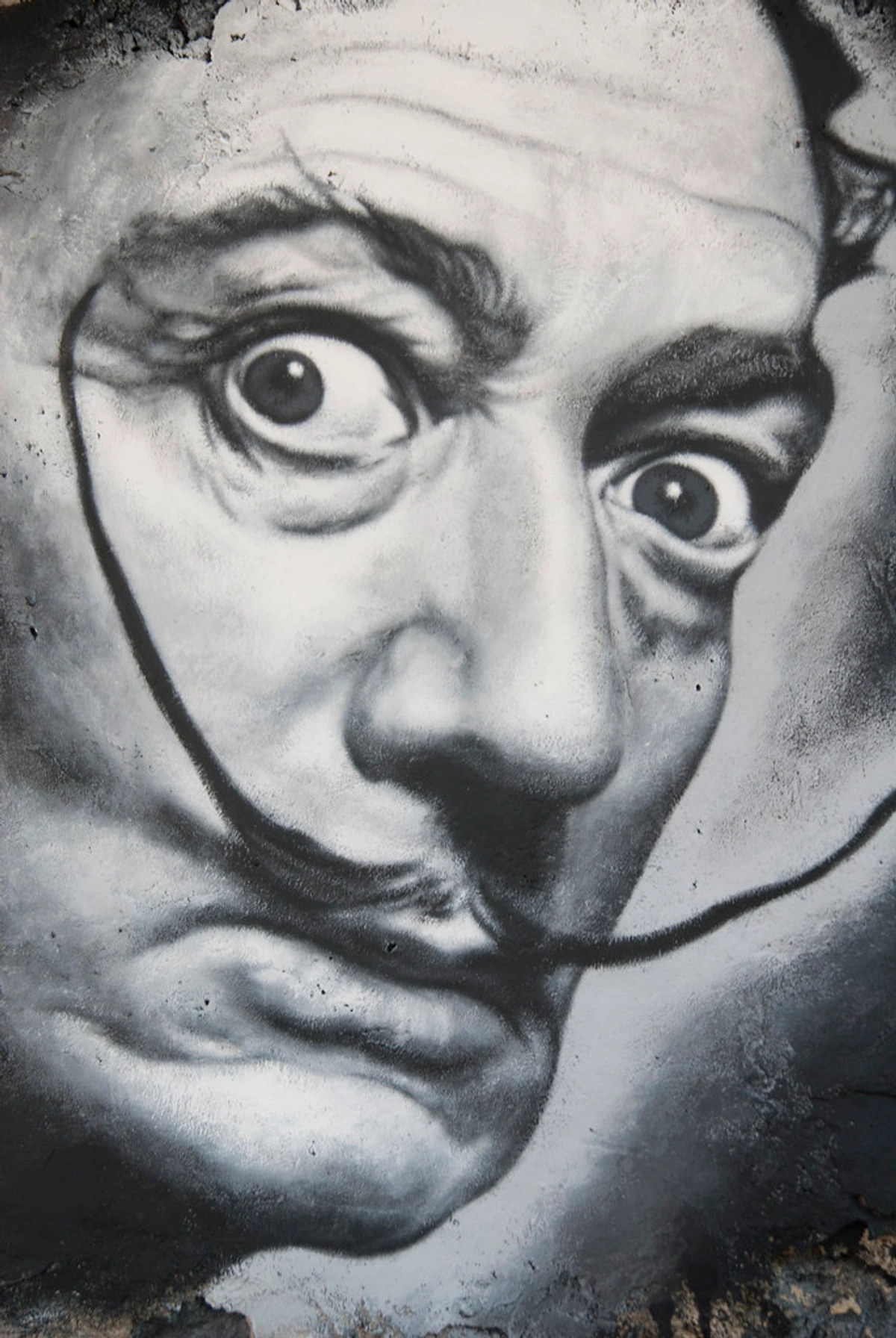

| Cubism/Surrealism | Fragmented forms, multiple perspectives (Cubism); dreamlike imagery, unconscious mind (Surrealism). Self-portraits as conceptual explorations of identity. | Pablo Picasso: Deconstructing identity through fragmented planes. Salvador Dalí: Exploring the subconscious, often with symbolic elements. |

| Contemporary Art | Expansive, challenging traditional notions of identity through performance, photography, digital media, and social commentary. Focus on persona, gender, race, and cultural critique. | Cindy Sherman: Invented characters, social archetypes. Frida Kahlo: Exploring pain, identity, and cultural heritage. Ai Weiwei: Documenting political dissent and personal resilience through performative self-portraits. |

The 20th Century and Beyond: Deconstructing Identity and Embracing Plurality

Modern and Contemporary Perspectives: Deconstructing Identity and Embracing Plurality

And then, with a sort of rebellious energy, we reach the modern era, where artists truly began to dismantle traditional notions of identity. It's a fascinating progression, isn't it? The 20th century, with its seismic shifts in societal norms and psychological understanding, saw the self-portrait evolve into a tool for radical experimentation and profound social commentary, often serving as a visual manifesto for new artistic movements and philosophical ideas, grappling with themes of war, industrialization, psychology, and evolving social structures. This was a period where the very concept of the 'self' was fractured and reassembled, opening up a universe of possibilities for artistic exploration.

Early 20th Century Movements: New Ways of Seeing (and Being Seen) – The Rise of Modernism

Before the fragmentation of Cubism or the dreamscapes of Surrealism, movements like Fauvism exploded with color, using it not for realistic depiction but for raw emotion. Artists like Henri Matisse created self-portraits that were explosions of vibrant, non-naturalistic hues, asserting a new freedom of expression. Concurrently, German Expressionism delved into the psychological, distorting forms and colors to convey inner turmoil and societal angst. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Max Beckmann created stark, often unsettling self-portraits that reflected the anxieties of a turbulent Europe. These were not pretty pictures, but powerful declarations of internal states. Other Expressionists like Paula Modersohn-Becker used self-portraiture to explore themes of motherhood, femininity, and identity with a profound, almost primal honesty, often depicting herself nude or semi-nude, challenging societal norms and offering a deeply personal and vulnerable vision of womanhood. Their work captures the rawness of inner experience, often with a stark emotional intensity that still resonates today.

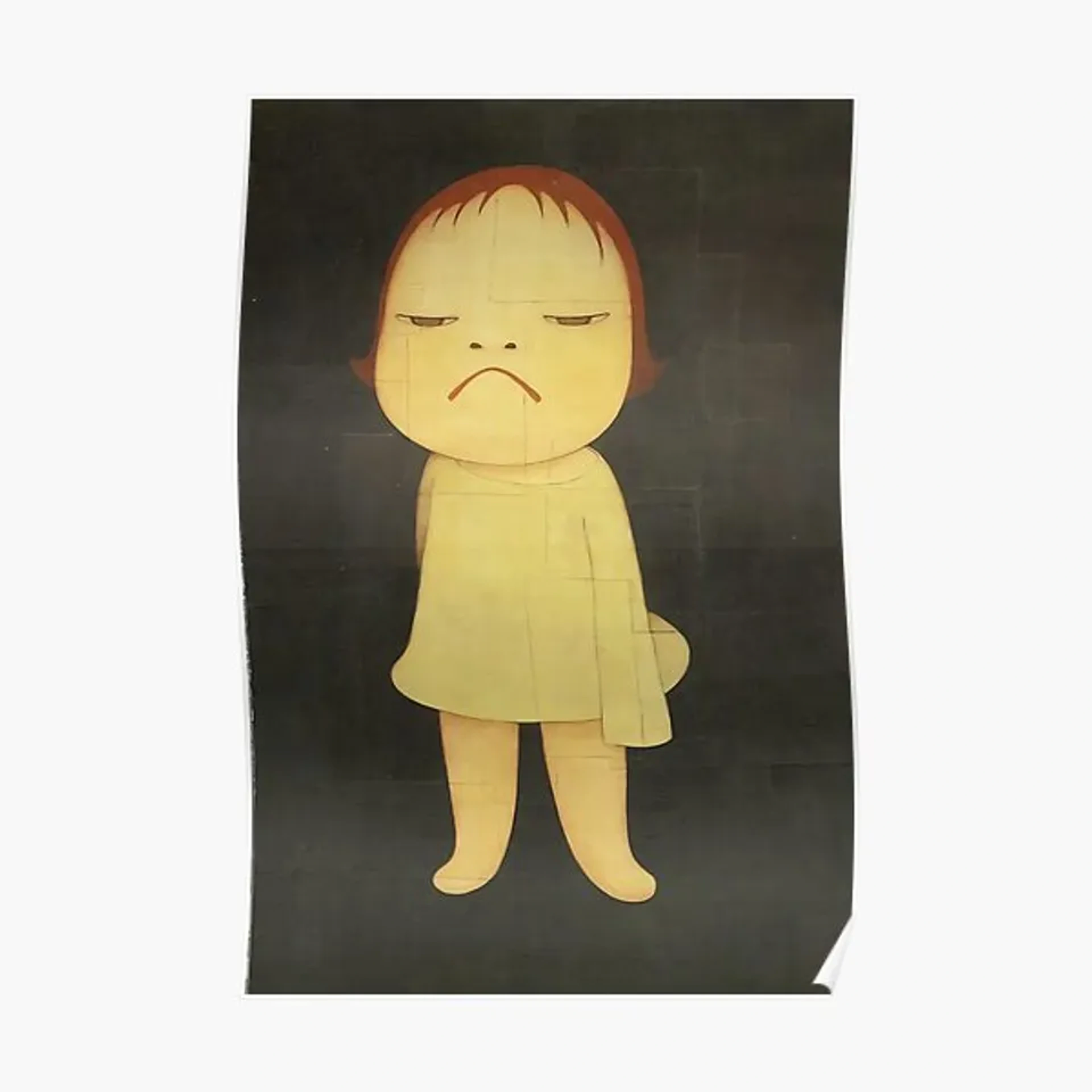

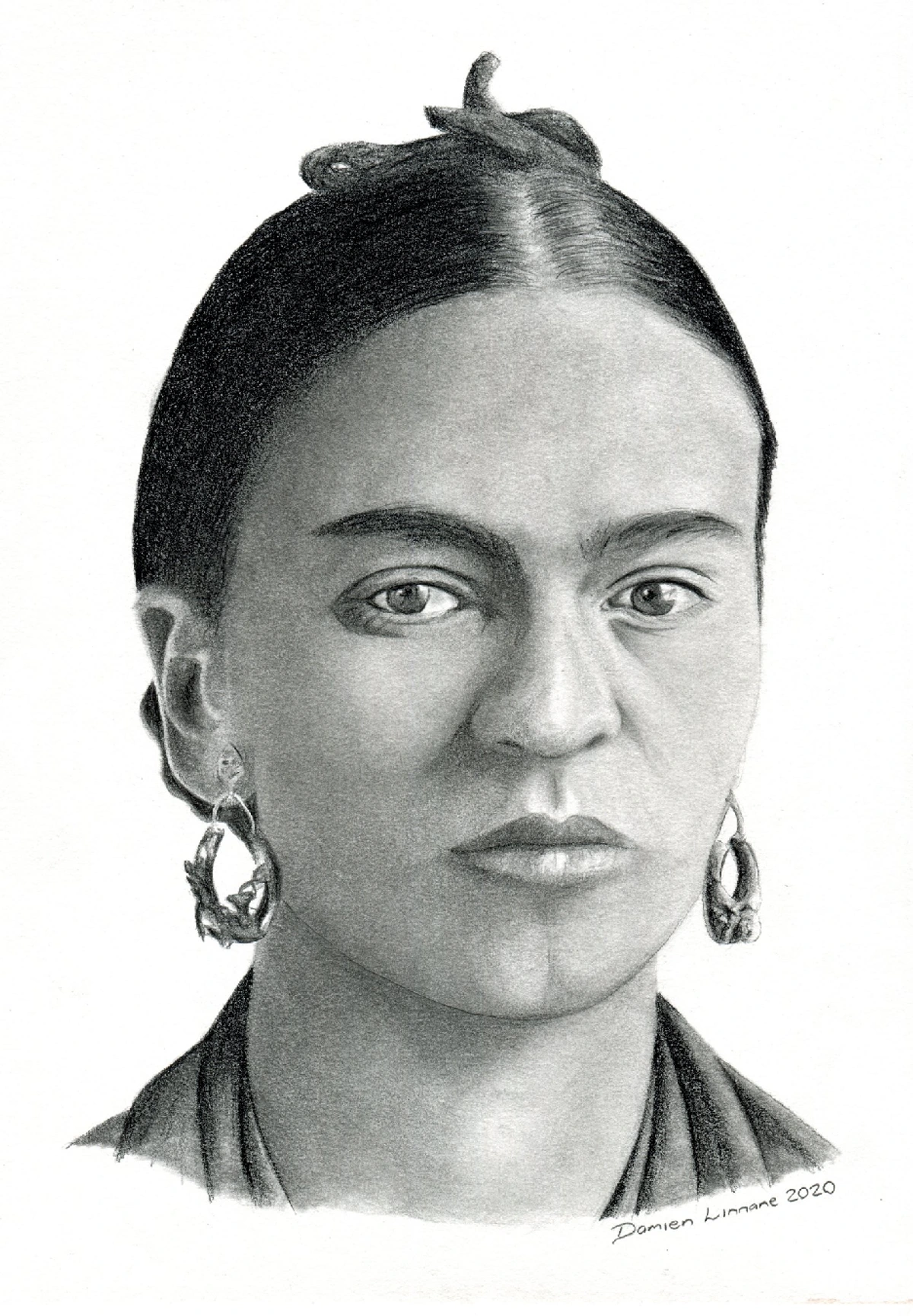

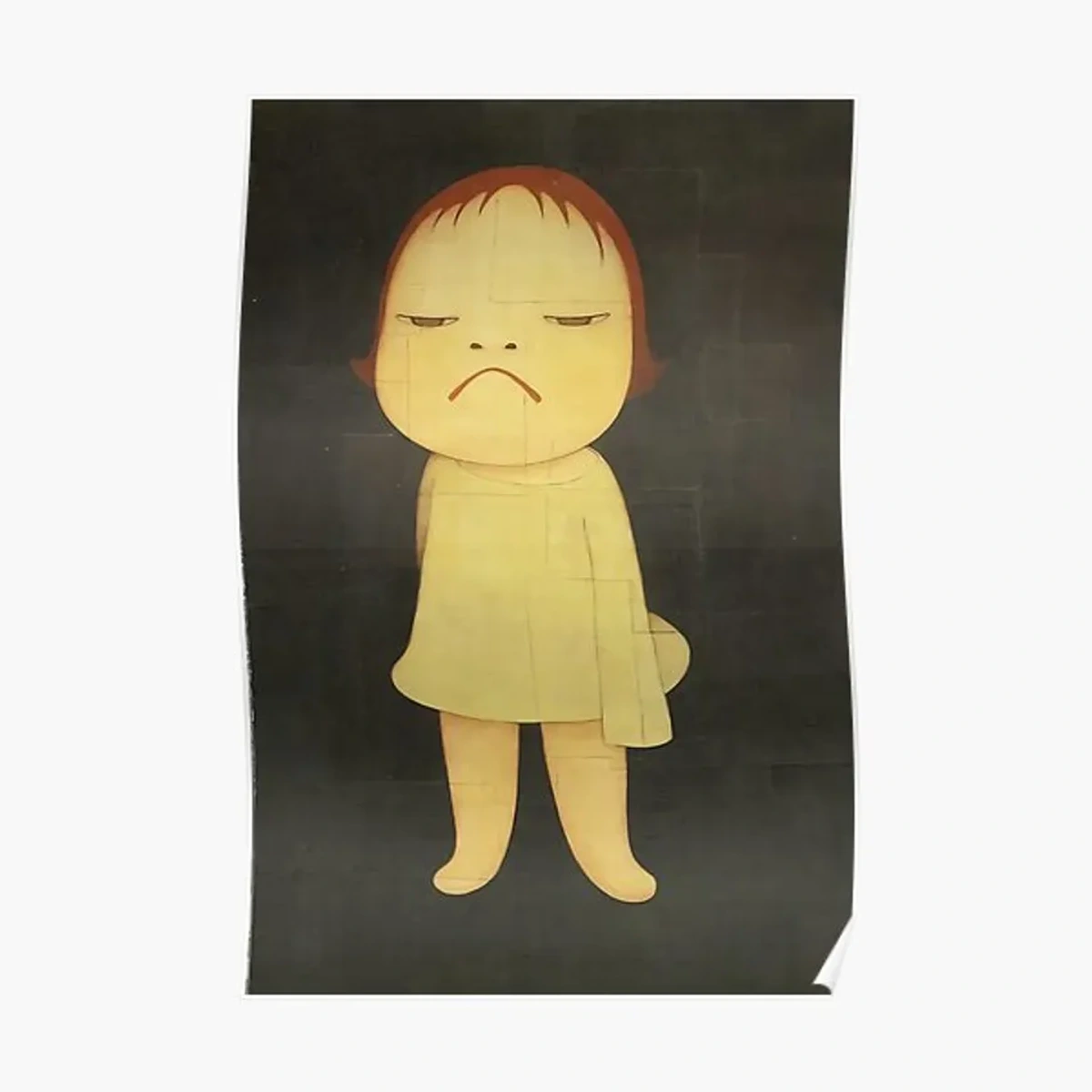

Think of someone like Frida Kahlo, whose self-portraits are utterly iconic. She used her image not just to depict herself, but to explore profound themes of physical and emotional pain, complex identity, rich Mexican culture, and unwavering resilience, creating powerful, often surreal, narratives that resonate deeply even today. Her work is a testament to the power of personal narrative in universal storytelling, making her one of the most celebrated and influential self-portraitists of all time. Before we dive deeper into Frida's incredible work, it's worth noting how artists like Edvard Munch (whose "The Scream" is almost a universal self-portrait of anxiety, isn't it?) used self-portraits to capture the raw, often unsettling emotional landscape of the individual, a hallmark of Expressionism. This was less about external appearance and more about internal, psychological truth, often distorted and highly stylized.

Before we dive deeper into Frida's incredible work, it's worth noting how artists like Edvard Munch (whose "The Scream" is almost a universal self-portrait of anxiety, isn't it?) used self-portraits to capture the raw, often unsettling emotional landscape of the individual, a hallmark of Expressionism. This was less about external appearance and more about internal, psychological truth, often distorted and highly stylized.

Then, artists like Pablo Picasso used self-portraits to explore identity through the fragmented lenses of Cubism. His early self-portraits, from the realistic to the more abstracted, offer a stunning visual diary of an artist constantly reinventing himself and the way he saw the world. These distortions weren't accidental; they were deliberate acts of questioning and redefinition, breaking down the traditional gaze to explore multiple facets simultaneously, reflecting the fractured nature of modern experience. It's almost like he was saying, "You think you know me from one angle? Let me show you all the angles at once!" Other Cubists, like Georges Braque, also implicitly explored self-representation through their formal experiments, even if not always explicitly labeled as self-portraits, using fragmented planes to convey a multi-faceted sense of being. This radical approach challenged viewers to see beyond conventional realism, inviting a more intellectual and conceptual engagement with the self. It shattered the notion of a single, fixed perspective, mirroring the psychological fragmentation and complexities of the modern world. This led to a profound shift in how identity could be portrayed, opening the door for future avant-garde movements and permanently altering how we conceive of the self in art. It forced us to confront the idea that identity isn't singular, but a complex, shifting construction.

It's this deliberate deconstruction that allows for such profound, multifaceted statements about identity, moving beyond superficial resemblance to a deeper conceptual exploration of the self.

Post-War European Art: Existential Angst and Abstraction

Following the two World Wars, European art saw a profound shift towards existential themes and abstraction in self-portraiture. Artists grappled with the trauma of conflict and the questioning of human values. Figures like Francis Bacon, with his visceral, distorted self-portraits of screaming popes and isolated figures, captured the anguish and alienation of the post-war era. His work is a powerful visual expression of the human condition under duress, often depicting himself in isolated, almost cage-like spaces, mirroring internal torment. Concurrently, movements like Art Informel and Tachisme in Europe saw artists like Jean Fautrier and Wols creating abstract works that, while not literal self-portraits, were deeply personal expressions of their inner psychological states, their raw gestures and textures acting as a visual record of their being.

American Art of the Mid-20th Century: Action Painting, Pop Icons, and Feminist Voices

Across the Atlantic, American art was coming into its own, with Abstract Expressionism dominating the scene. While not traditionally self-portraiture, the action paintings of artists like Jackson Pollock are often seen as performative self-portraits, a direct record of the artist's physical and emotional engagement with the canvas. The canvas became an arena for self-expression, a mirror to the artist's psyche. Later, Pop Art ushered in a new era where celebrity culture and mass media heavily influenced perceptions of self. Artists like Andy Warhol became masters of self-promotion, using silkscreen self-portraits to explore themes of fame, consumerism, and the constructed nature of public image. His self-portraits often blurred the lines between advertising and fine art, inviting viewers to question authenticity in an increasingly mediated world. Simultaneously, the Feminist Art Movement utilized self-portraiture as a powerful tool for social and political commentary. Artists like Hannah Wilke or Carolee Schneemann used their own bodies and images to challenge patriarchal norms, confront objectification, and assert female agency, transforming personal experiences into universal statements about gender, power, and identity. Other Pop artists like Roy Lichtenstein subtly infused elements of self into their comic-book-inspired works, while in Feminist Art, Judy Chicago used self-portraiture as part of her larger narratives exploring women's experiences and histories, creating an indelible mark on art history through personal revelation and collective empowerment. It's truly amazing how artists adapt and redefine what a "self" can be in art.

Artists like Salvador Dalí, another master of self-portrayal, employed the dreamlike narratives of Surrealism to delve into the subconscious, creating self-portraits that are often enigmatic, symbolic, and deeply psychological. He wasn't just painting his face; he was painting his dreams, his fears, his fantasies. His self-portraits are like visual riddles, inviting us to explore the hidden depths of his mind, blurring the lines between waking life and the fantastical realms of the subconscious. Other Surrealist artists like René Magritte also explored the mystery of identity through self-portraiture, often concealing his face to question the nature of representation itself.

Her work is a testament to the power of personal narrative in universal storytelling, making us confront the realities of pain and resilience, and inviting a deeper empathy from the viewer. It's a raw, unflinching look at the self, transformed into a universal statement, and continues to influence contemporary artists exploring identity and the body.

The Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries: Identity Politics and Digital Selves

The Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries: Identity Politics, Performance, and Digital Selves

As the 20th century drew to a close and the new millennium began, self-portraiture continued to expand its boundaries, embracing new technologies and deepening its engagement with identity politics. More recently, conceptual artists like Cindy Sherman have taken the self-portrait to entirely new, fascinating places. She doesn't depict herself in the traditional sense of revealing her 'true' identity, but rather brilliantly uses her own body as a versatile canvas to portray a multitude of invented characters and social archetypes. It’s a masterful blend of critique, performance, and a profound exploration of identity all at once. Her work challenges us to question what we see, and how easily we project meaning onto images, especially in an age saturated with mediated images. She makes us ask, 'Whose story is this, really?' This post-modern approach dismantles the notion of a fixed self, replacing it with a fluid, performative one, reflecting the complexities of identity in a media-driven society, making her one of the most influential contemporary artists working with self-representation. Her work probes the construction of femininity, celebrity, and social stereotypes, often with a subtle, disquieting humor that forces a re-evaluation of what we assume to be 'truthful' in images.

Artists like Ai Weiwei also use performative self-portraits, often involving photography and video, to document political dissent and personal resilience. He transforms his body and his actions into a powerful statement against oppression, making the self-portrait a tool for global human rights discourse. His work reminds us that the personal is often deeply political, challenging viewers to consider their own complicity or empathy, transforming individual experience into a collective call for justice. His iconic 'Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn' or 'Study of Perspective' series, while not always direct facial self-portraits, embody his presence and philosophical stance through his actions and body.

Global Perspectives: Self-Portraiture Beyond the Western Canon – A World of Selves

It's crucial to remember that self-portraiture is not exclusively a Western phenomenon. While Western art history often focuses on its individualistic trajectory, many non-Western traditions have rich, albeit different, approaches to self-representation. In some Asian art forms, for example, artists might subtly embed their presence within a vast landscape, or express their inner self through calligraphic brushstrokes that embody their spiritual state rather than their physical likeness. Indigenous artists worldwide have used various forms of self-depiction, from ceremonial masks to personal totems, to explore identity within communal and spiritual contexts. These diverse approaches remind us that the 'self' and its representation are culturally constructed, offering a richer, more nuanced understanding of this universal human impulse. For instance, in Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, artists like Hokusai occasionally included self-caricatures within their landscapes, humorously asserting their presence. In various African traditions, masks or sculptures might embody ancestral spirits or community roles, which, while not individualistic self-portraits, speak to a collective identity and connection to the self within a broader spiritual framework. These global perspectives enrich our understanding, showing that the urge to represent oneself is universal, even if its forms and meanings diverge dramatically. Consider the detailed court paintings of Mughal India, where artists might discreetly include their image among courtiers, or the subtle presence of the artist's hand in traditional Chinese landscape painting, where the brushwork itself is seen as a direct extension of the artist's being and spiritual state.

Beyond the overtly political, artists like Gillian Wearing use self-portraits to explore the complexities of identity and memory, often through re-enactment or by adopting the personas of others. And think of Yayoi Kusama, whose self-portraits, often within her immersive infinity rooms, speak to themes of self-obliteration and cosmic unity, turning the personal into the universal on a grand scale. The contemporary self-portrait is a vibrant, ever-evolving landscape of inquiry into who we are, individually and collectively, utilizing an array of innovative techniques and conceptual approaches to articulate the multifaceted nature of the modern self. Artists like Sam Taylor-Johnson (formerly Sam Taylor-Wood) explore vulnerability and emotional states, while Tracey Emin uses her self-portraiture as a raw, confessional exploration of her own life and experiences, breaking down boundaries between art and autobiography. The landscape of identity is constantly shifting, and self-portraiture is the artist's most immediate tool for charting its ever-evolving contours.

Her work is a powerful reminder that every image, especially those of ourselves, is a construction, inviting us to look beyond the surface.

Why Do Artists Paint Themselves? The Psychology and Purpose – Unveiling the Inner Drive

This is where it gets really juicy, isn't it? Why, out of all the countless, inspiring subjects in the world, would an artist consistently choose themselves? It’s a question I’ve pondered often, and my conclusion is that it's rarely about simple ego; in fact, it's quite often the opposite. It’s about the profound accessibility and intimacy of the self, a wellspring of endless complexity and narrative. For many, it's a necessary act of creation, a fundamental part of their artistic practice. Here's what I've observed and experienced through my own creative journey and studying others:

Self-Expression and Communication: A Visual Language of the Soul

At its heart, isn't all art a form of communication? And when the subject is the artist themselves, that communication becomes intensely personal, raw, and often deeply resonant. Self-portraits are a primary vehicle for artists to articulate their inner world – their joys, their sorrows, their struggles, their triumphs – in a visual language that transcends words. It's a way of making the invisible visible, of translating complex emotions and ideas into tangible form. For me, an abstract artist, this is particularly true. Even without a recognizable face, my canvases are often self-portraits of my emotional state, a direct conduit for my innermost thoughts and feelings to be expressed and shared. It’s about building a bridge between one soul and another, inviting empathy and understanding, offering a glimpse into the human experience that is both intensely personal and universally relatable. It’s like a visual diary where the words are colors and forms, speaking directly from the heart.

Self-Therapy and Emotional Processing: A Visual Confession

Sometimes, the canvas or the lens isn't just a surface; it's a confessional booth, a private space where an artist can wrestle with their inner demons, celebrate their triumphs, or simply process the sheer, overwhelming complexity of human emotion. Creating a self-portrait, for many, is a deeply cathartic act. It’s a chance to externalize intense feelings—grief, joy, anxiety, wonder, even the existential dread we sometimes feel—and give them tangible form. It's a way of saying, "This is what it feels like right now," without needing words, a silent scream or a quiet song rendered in paint or clay. I've often found my own abstract pieces, with their wild colors and chaotic strokes, to be direct conduits for emotional release, a form of self-portraiture of my inner turmoil, even if no face is present. It’s art as therapy, pure and unadulterated, a visual confession that can lead to profound healing or simply a deeper understanding of one's own emotional landscape. This profound emotional processing is one of the most compelling reasons artists turn the lens inward, transforming personal struggle or ecstasy into universal human narratives. It’s a brave act of vulnerability, offering a path to healing not just for the artist, but for the viewer who connects with their truth.

Introspection and Self-Discovery: The Artist as Philosopher

For many, including myself, the act of creating a self-portrait is a deeply meditative, almost ritualistic process. It's a forced moment of stillness, of truly seeing oneself without the filters we usually apply – the masks we wear for the world, the self-judgments that cloud our perception. You're not just drawing or painting what's physically there; you're interpreting it through your own internal landscape, adding layers of emotion, memory, and aspiration, sometimes even delving into the subconscious. It really can feel like therapy without the hourly fee, a concentrated journey inward to understand the complex tapestry of thoughts and feelings that make you you. It’s a raw, honest confrontation with self, a moment where the internal and external briefly align, pushing beyond surface appearance to psychological depth, forcing you to ask, 'What truly makes me tick?' and 'What hidden aspects of myself am I ready to reveal?' This process can be akin to a visual journaling, a record of evolving self-awareness over time. It’s a raw, honest confrontation with self, a moment where the internal and external briefly align, pushing beyond surface appearance to psychological depth, forcing you to ask, 'What truly makes me tick?' and 'What hidden aspects of myself am I ready to reveal?' This mindful approach can transform the act of self-portraiture into a meditative practice, fostering a deeper connection with your inner self, much like exploring mindful moments-how-abstract-art-can-be-a-gateway-to-inner-peace-and-reflection. It’s about cultivating an honest gaze, a radical act of self-acceptance and profound observation, and ultimately, a journey towards self-knowledge, a deeply personal and often transformative experience.

Practice and Mastery: The Perpetual Student

Let's be honest, finding a good model can be a hassle! And expensive. The most convenient model an artist has is always themselves. It's a fantastic way to hone skills, experiment with how artists use color, explore composition and balance, or practice challenging techniques like perspective. From mastering chiaroscuro to understanding anatomical nuances, the self-portrait provides an endlessly patient subject. There's no pressure from a client, just the pure joy of learning and developing your craft. I mean, who's going to complain if I spend an entire day trying to get the light just right on my own nose? It's a low-stakes, high-reward learning environment, perfect for pushing boundaries, refining rendering skills, or even just mastering proportions. This is especially true for experimenting with light and shadow, chiaroscuro, or dramatic tenebrism – techniques that can transform a simple likeness into a profound emotional statement, and even experimenting with new materials, much like exploring oil sticks for expressive mark-making. It's a tireless, ever-present model ready for any artistic challenge, from mastering the intricacies of a hand to capturing the subtle play of light on skin, and always willing to pose for just one more hour. This constant practice is what hones an artist's craft, preparing them for more complex commissions and deeper conceptual explorations. It's a tireless, ever-present model ready for any artistic challenge, from mastering the intricacies of a hand to capturing the subtle play of light on skin, and always willing to pose for just one more hour. And sometimes, it's about pushing the boundaries of traditional representation, moving towards the definitive guide to understanding gestural abstraction-from-action-painting-to-contemporary-expression to capture the very act of feeling.

Identity and Persona: Crafting the Self in Public and Private

Our identities aren't static; they shift and evolve, often in subtle, sometimes dramatic, ways. A self-portrait can be a potent way to capture a specific facet of that ever-changing identity or to deliberately explore different personas. Artists might ingeniously use costume, makeup, symbolic elements, or even dramatic settings to portray who they are, who they aspire to be, or even to offer a biting critique of societal expectations. It's a powerful tool for self-definition, for narrative building, and for experimenting with how one is perceived versus how one truly feels. It's like trying on different selves, visually, inviting both introspection and external interpretation. This play with persona can be incredibly liberating, reminding us that identity is often a performance, a fluid narrative rather than a rigid fact. This act of self-construction can be deeply empowering, allowing artists to challenge established norms and redefine their place in the world. It’s like trying on different selves, visually, inviting both introspection and external interpretation. This play with persona can be incredibly liberating, reminding us that identity is often a performance, a fluid narrative rather than a rigid fact.

Sometimes, the self-portrait delves into the hidden aspects, the roles we play, or the emotions we typically keep veiled. It's a chance to unmask, or paradoxically, to create a new mask that reveals a deeper truth about the fluidity and multiplicity of identity. It can be an act of audacious vulnerability or a clever masquerade, both equally revealing, engaging in a dialogue with Jungian archetypes or the Freudian unconscious. It's the artist as both actor and director in the theatre of their own self.

Sometimes, the self-portrait delves into the hidden aspects, the roles we play, or the emotions we typically keep veiled. It's a chance to unmask, or paradoxically, to create a new mask that reveals a deeper truth about the fluidity and multiplicity of identity. It can be an act of audacious vulnerability or a clever masquerade, both equally revealing, engaging in a dialogue with Jungian archetypes or the Freudian unconscious. It's the artist as both actor and director in the theatre of their own self.

Social and Political Commentary: The Personal as Political

Sometimes, a self-portrait transcends personal introspection to become a powerful act of social or political commentary. Artists from diverse backgrounds have used their own image to challenge stereotypes, expose injustices, or make bold statements about power, gender, race, and class. Think of artists using their self-portraits to reclaim narratives, protest oppression, or simply assert their presence in spaces where they might have been historically marginalized. For instance, during the Harlem Renaissance, artists used their self-portraits to assert Black identity and challenge prevailing racist caricatures, offering powerful images of dignity and strength and celebrating their cultural heritage. More recently, queer artists have used self-portraiture to explore themes of sexuality, gender identity, and the body in ways that challenge heteronormative narratives and demand visibility, fostering a sense of community and understanding. It's a way of saying, "I am here, and my experience matters," often with profound implications for broader society, sparking dialogue and promoting social change. From the feminist art movement to civil rights activism, and even in post-colonial contexts, the self-portrait has been a potent weapon in the fight for visibility and justice, turning the individual experience into a collective statement and a powerful instrument of protest and affirmation.

credit,

licence This strategic use of self-representation can dismantle existing power structures and advocate for a more inclusive future. From the feminist art movement to civil rights activism, and even in post-colonial contexts, the self-portrait has been a potent weapon in the fight for visibility and justice, turning the individual experience into a collective statement and a powerful instrument of protest and affirmation. It’s an undeniable assertion that "my existence is a statement, and my art is my voice."

credit,

licence This strategic use of self-representation can dismantle existing power structures and advocate for a more inclusive future. From the feminist art movement to civil rights activism, and even in post-colonial contexts, the self-portrait has been a potent weapon in the fight for visibility and justice, turning the individual experience into a collective statement and a powerful instrument of protest and affirmation. It’s an undeniable assertion that "my existence is a statement, and my art is my voice."

Challenging Societal Norms and Power Structures: The Personal as Political

Building on social commentary, self-portraits can directly confront and dismantle entrenched societal norms, biases, and power structures. When an artist, especially one from a marginalized group, asserts their image and narrative, it can be a profoundly radical act. It challenges who gets to be seen, who gets to define beauty, and whose stories are considered worthy of art. Think of artists using their self-portraits to critique colonial legacies, expose gender inequality, or simply exist defiantly in spaces that seek to erase them. It's a visual manifesto, a declaration of presence and self-worth that ripples far beyond the canvas, inviting viewers to question their own complicity in upholding or challenging these structures. It’s an undeniable assertion that "my existence is a statement, and my art is my voice." This is not merely an artistic statement but a powerful form of activism, using the visual medium to catalyze change and foster critical dialogue.

Legacy and Documentation: A Conversation Across Time and a Visual Artist's Statement

Every self-portrait is, at its core, a snapshot in time—a tangible declaration from the artist saying, "I was here. This was me." For centuries, it was one of the few enduring ways artists could ensure their own image, and by extension, their narrative, would survive beyond their lifetime. It contributes significantly to their personal story, their artistic timeline, and solidifies their indelible place in history, allowing future generations to connect directly with the creator. When you look at an artist's self-portraits compiled over many years, you literally see their life, their struggles, their triumphs, and their evolution unfold before you, which is just incredible to witness. It's a conversation across time, from them to us, a profound act of self-preservation and communication, a visual legacy passed down through generations. This enduring visual autobiography offers a unique window into the human spirit's journey through time. This mirrors our own existential questions, making the artist's personal journey a shared one.

Interestingly, the motivations behind a self-portrait often align closely with the very essence of an artist's statement. Both are deliberate acts of self-definition, attempts to articulate personal vision, process, and meaning. A self-portrait, in this sense, can be a visual artist's statement, a pictorial declaration of their artistic identity and philosophical stance. It’s where the visual language speaks volumes about the very intentions and core beliefs that an artist might otherwise put into words, offering a complementary layer of understanding. It's a powerful way to leave your mark, both literally and figuratively.

The Many Faces of a Self-Portrait: Mediums and Styles – An Expansive Palette

This journey into self can sometimes even manifest as an exploration of the unconscious, a visual dreamscape of the artist's psyche. Perhaps it's a way to wrestle with the existential questions of human existence, or simply to capture the raw, fleeting essence of a moment. Just like there's no single way to be a person, there's no single way to create a self-portrait. The beauty is in the boundless possibilities of mediums and styles. I mean, I love working with vibrant colors, so even some of my abstract pieces, though not literal self-portraits, feel like reflections of my inner world. It's about finding the language that best articulates that inner landscape.

Let's look at some popular avenues:

Common Motifs and Symbolism in Self-Portraits – Decoding the Artist's Hidden Language

Beyond the artist's face, self-portraits are often rich with symbolism and recurring motifs that offer deeper insights into their identity, beliefs, and circumstances. Artists frequently incorporate objects like brushes or palettes to signify their profession, or books to represent their intellect. Animals might symbolize aspects of their personality or spiritual beliefs, much like the symbolism of animals in contemporary art. Mirrors, of course, are a classic motif, directly referencing the act of self-observation and the elusive nature of perception. Skulls or fleeting images can serve as memento mori, reminders of mortality, adding a layer of philosophical depth. The setting itself, whether a cluttered studio, a lush garden, a desolate landscape, or even an imagined space, can become a powerful extension of the artist's inner world or their societal role. Even the clothes worn, or the lack thereof, can convey complex messages about status, vulnerability, defiance, or a deliberate rejection of societal norms. Understanding these visual cues unlocks layers of meaning beyond mere resemblance, transforming the portrait into a visual narrative replete with hidden messages and profound insights. It's like a carefully constructed visual poem, with each element a deliberate word or phrase, designed to tell a deeper story about the artist's inner world and their interaction with the external.

The Anatomy of a Self-Portrait: Beyond the Face – Decoding the Visual Language

It's not just the artist's literal face that forms the self-portrait. Think of the gaze itself: direct, averted, challenging, vulnerable. This is a crucial element. Then there's the pose—heroic, melancholic, casual, defiant, or introspective. The setting can range from a cluttered studio, speaking to the artist's craft and dedication, to a vast, allegorical landscape that mirrors inner turmoil or grand aspirations, or even an empty void emphasizing isolation. Objects placed within the frame, whether a skull signifying mortality, a specific tool of their trade, a personal memento, or an unexpected prop, act as visual footnotes to the artist's life and philosophy, often enriching the narrative with layers of personal and cultural meaning. Even the light can be symbolic, casting dramatic shadows to evoke mystery or struggle, or bathing the figure in a soft glow to convey serenity or idealism. And, of course, the color palette itself, from somber monochromes to vibrant explosions, speaks volumes about the artist's emotional state or artistic intent. Each element is a deliberate choice, a word in the artist's visual language, all contributing to the larger narrative of who they are, or who they wish to be perceived as, making the self-portrait a deeply coded and rich form of communication.

The Canvas of Self: Mediums and Styles

Just like there's no single way to be a person, there's no single way to create a self-portrait. The beauty is in the boundless possibilities of mediums and styles. I mean, I love working with vibrant colors, so even some of my abstract pieces, though not literal self-portraits, feel like reflections of my inner world. It's about finding the language that best articulates that inner landscape. Each medium offers a unique set of tools and a distinct voice for communicating that inner world.

Let's look at some popular avenues:

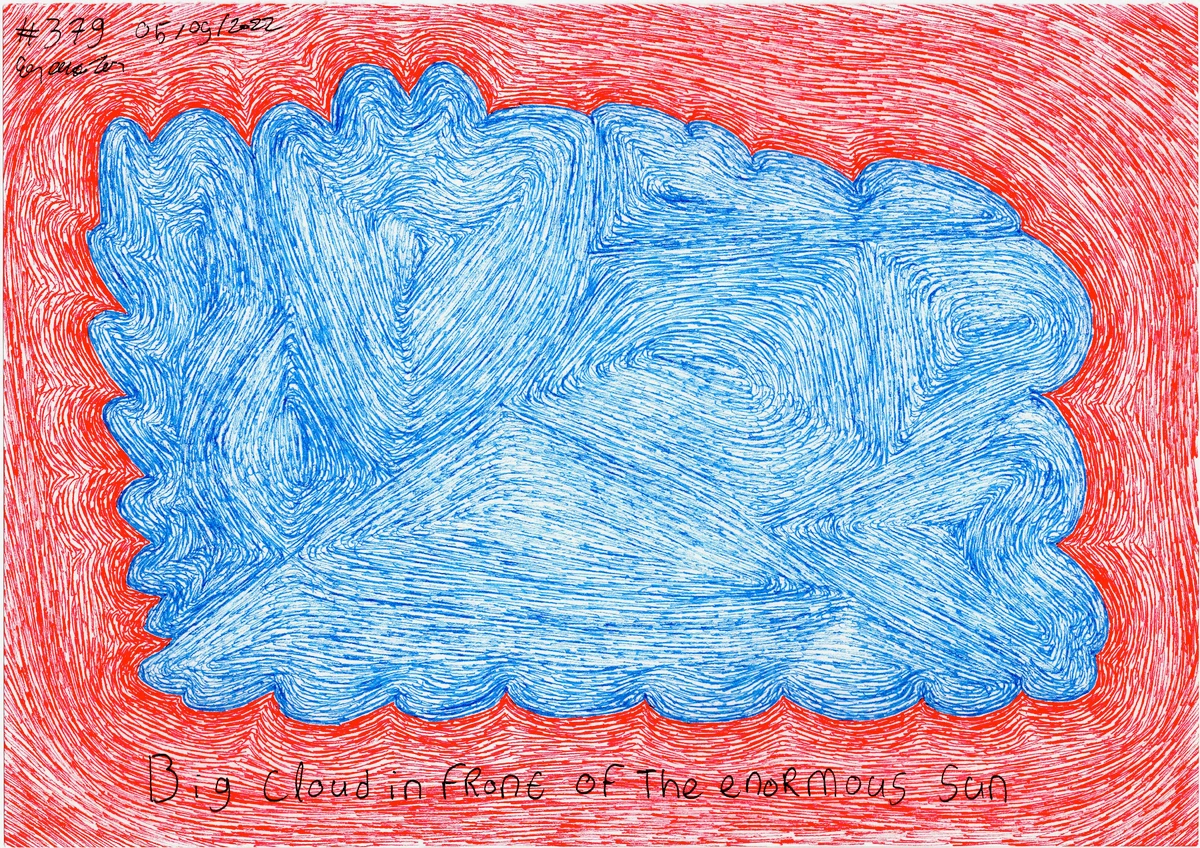

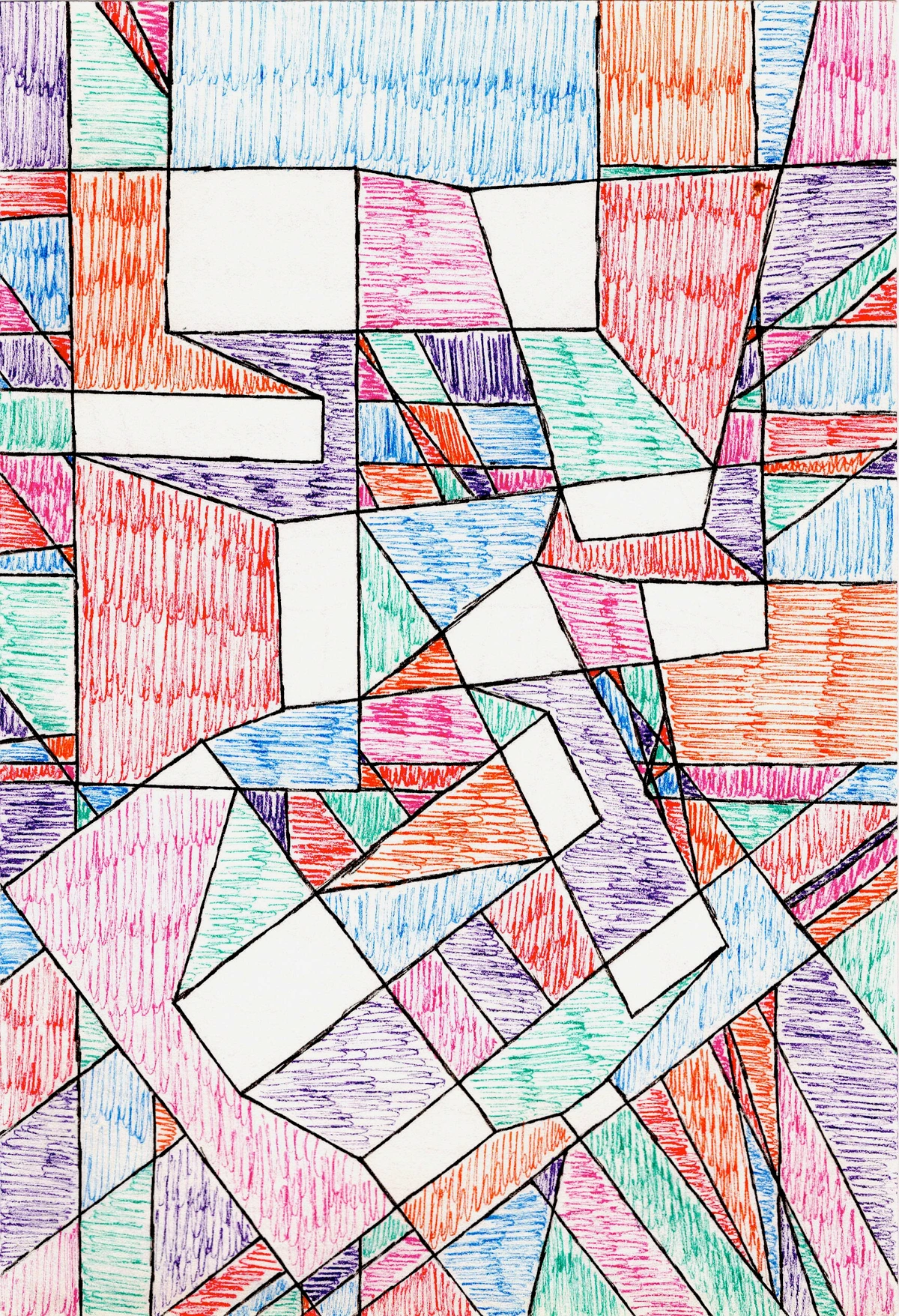

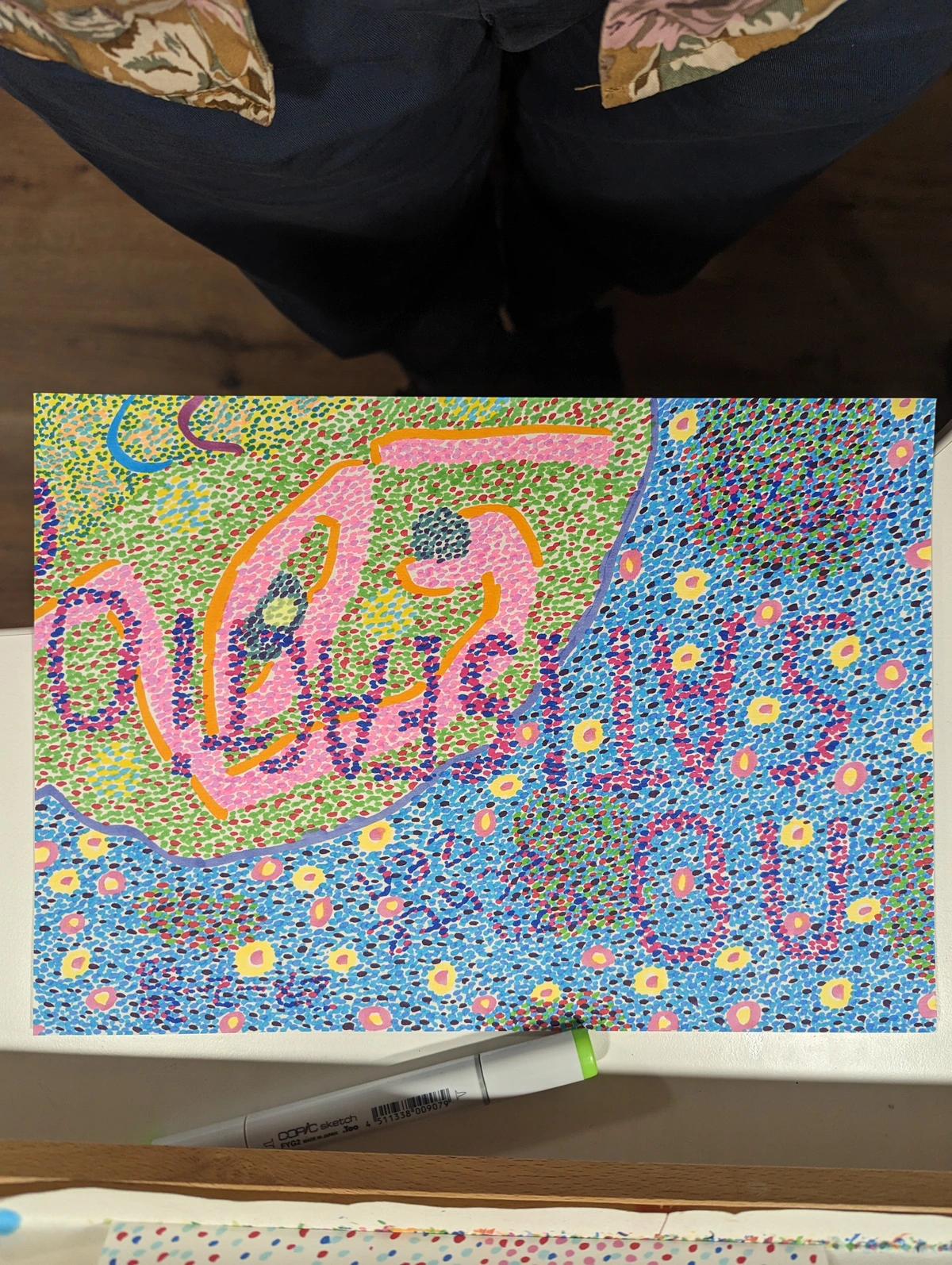

- Painting: This is, arguably, the most traditional and enduring medium for self-portraiture. From the meticulous, detailed oils of the Old Masters to the raw, expressive strokes of Expressionism or the bold, vibrant colors of Fauvism, painting allows for incredible depth, nuance, and emotional resonance. You can employ anything from hyper-realistic rendering to wild, abstract interpretations, each offering a distinct window into the artist's psyche. Consider the luminous self-portraits of Frida Kahlo or the intense, textural works of Vincent van Gogh. Techniques like glazing (building up thin, transparent layers of paint), impasto (applying thick, textured paint), scumbling (dry-brushing thin layers over a textured surface), or even fresco (painting on wet plaster), each offer unique possibilities for self-expression, allowing the artist to manipulate light, shadow, and surface to convey their deepest truths. Even a seemingly abstract piece, like 'When The Music Is Over', can be seen as a self-portrait of an emotional state, a feeling I experienced, translated through color and form, making the canvas a direct extension of my inner world. The versatility of paint allows for both grand, allegorical self-portraits and intimate, introspective studies, capturing the full spectrum of human experience. And sometimes, it's about pushing the boundaries of traditional representation, moving towards the definitive guide to understanding gestural abstraction-from-action-painting-to-contemporary-expression to capture the very act of feeling.

Sometimes, a self-portrait doesn't even need to be a human form. It can be a vibrant landscape of colors and textures that embodies the artist's inner world, much like this piece that evokes motion and emotion, a true reflection of the artist's internal landscape and the definitive guide to understanding color harmonies in abstract art. This is where abstract art truly shines, allowing for a profound connection between the artist's inner world and the viewer's perception, often exploring the concept of the definitive guide to composition in abstract art through an emotional lens. It emphasizes that a self-portrait isn't solely about objective reality but about subjective experience and the myriad ways to convey it, tapping into the definitive guide to understanding abstract art-styles.

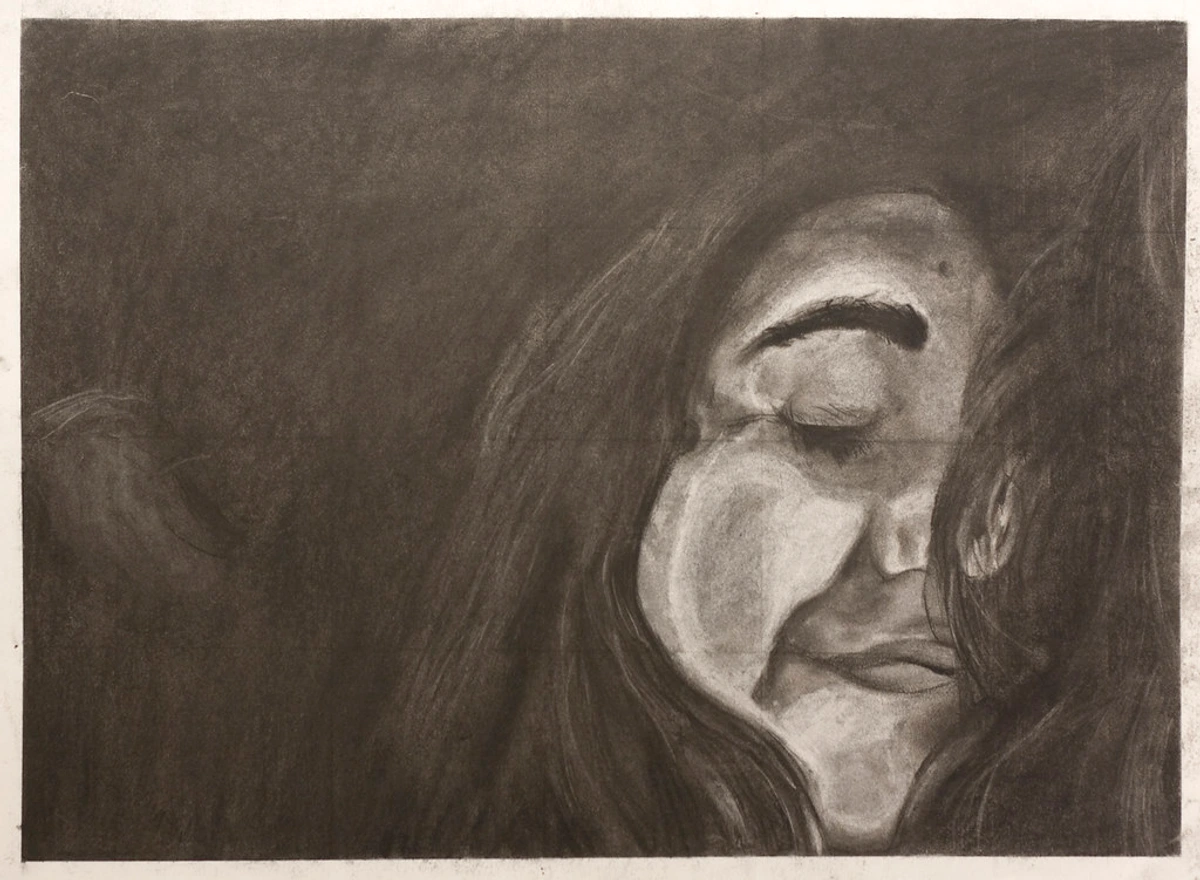

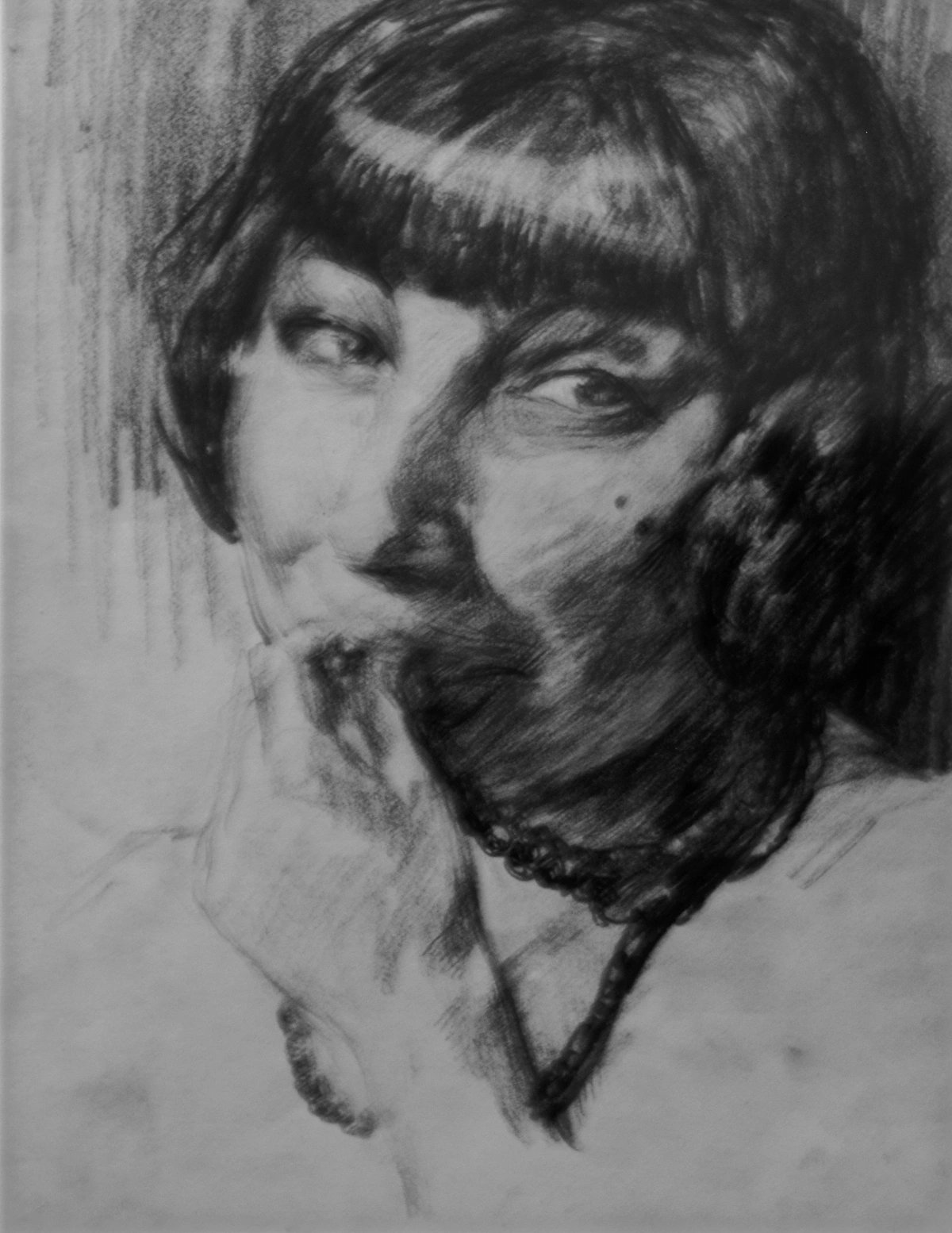

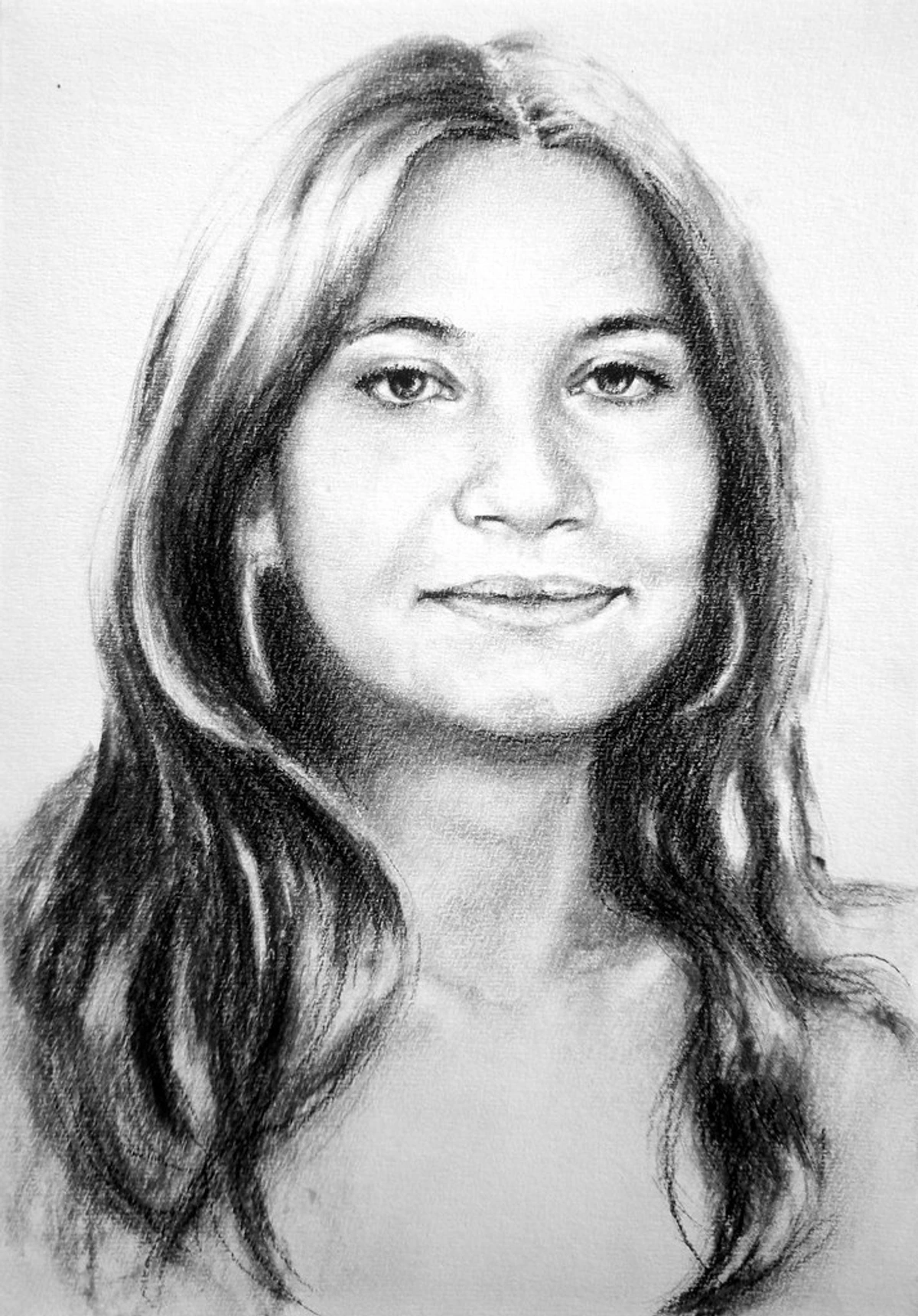

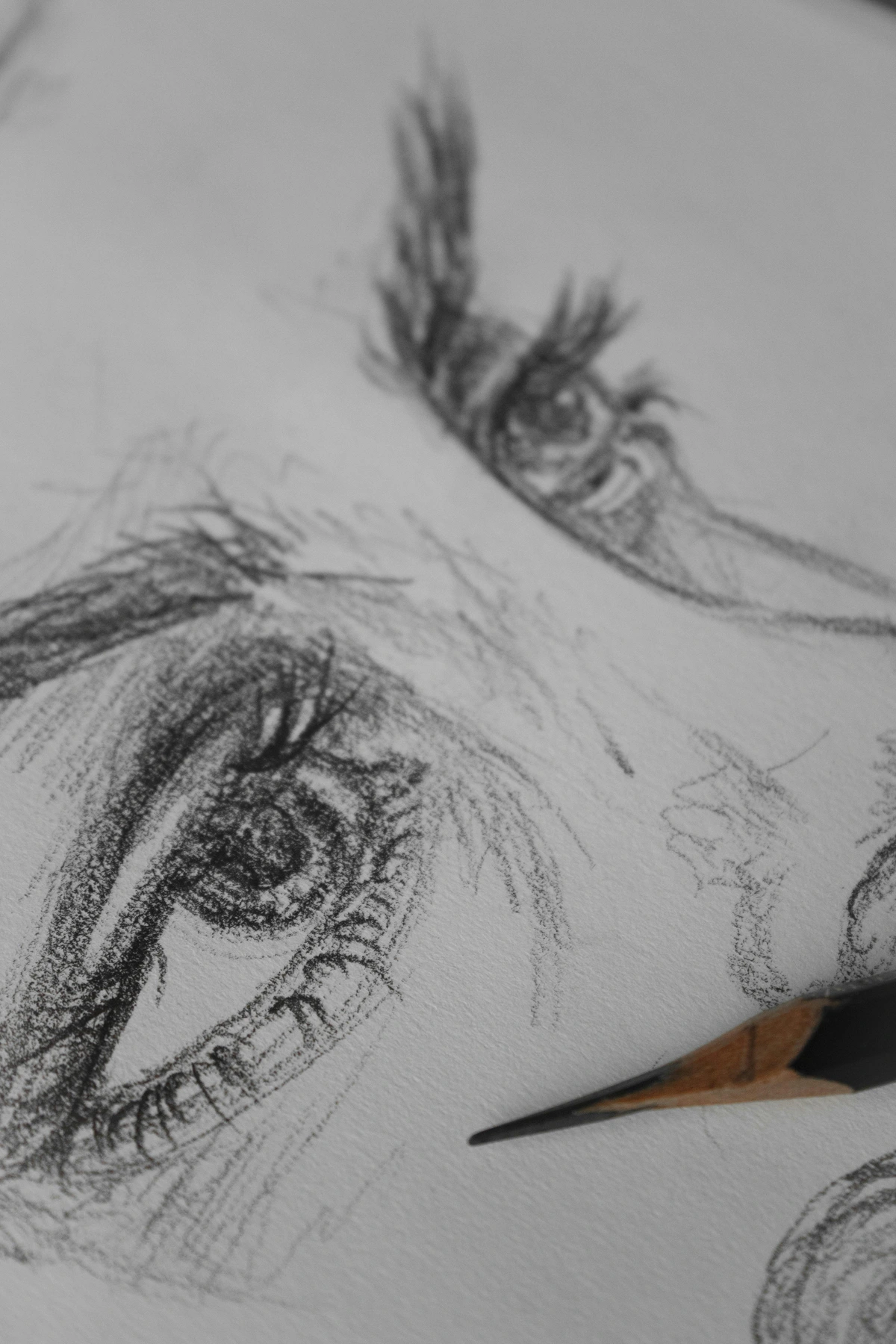

- Drawing: Charcoal, pencil, pastels (oh, I love the buttery richness of pastels!), ink – these mediums offer an incredibly immediate, direct, and often intimate connection between the artist's hand and the paper. I find charcoal particularly powerful for capturing raw emotion and rich texture, don't you? It's incredibly versatile, allowing for both delicate, precise detail and dramatic, shadowy forms, making it a favorite for quick studies and profound explorations of self. Consider the intense charcoal self-portraits of Käthe Kollwitz, which convey profound empathy and suffering, or the meticulous pencil drawings of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, showcasing anatomical perfection. It’s like a visual stream of consciousness, a direct translation from mind to material, often revealing the very process of thought and observation, and capturing a spontaneity that painting sometimes can't. The immediacy of drawing allows for a raw, unfiltered expression, capturing fleeting thoughts and emotions with unparalleled directness, offering a profound glimpse into the artist's transient states of being.

credit, licence  credit,

licence

credit,

licence

Sometimes the most intricate details, like the human eye, can become a world in itself in a self-portrait, revealing vast depths of emotion through subtle shading and texture, much like an abstract artist might explore the definitive guide to understanding line in abstract art-from-gestural-marks-to-geometric-forms to convey internal states. It reminds me how even a small detail can hold immense expressive power, conveying a narrative far beyond its literal form.

- Sculpture: Creating a three-dimensional likeness of oneself, whether in clay, bronze, marble, wood, or found objects, is an ancient and enduring form of self-portraiture. It offers a tangible, physical presence, allowing the artist to explore form, volume, and how their identity occupies space, inviting viewers to walk around and experience the self from multiple angles. Think of ancient Roman busts, which were often strikingly realistic, or modern artists like Auguste Rodin, who explored intense emotion and psychological depth even in his sculptural self-representations, capturing fleeting moments of internal struggle or profound thought. Contemporary sculptors, like Charles Ray or Ron Mueck, push the boundaries further, creating hyper-realistic or subtly distorted figures that challenge our perceptions of the human form and identity. It's a conversation with material, giving weight and form to the intangible self, making the artist's presence undeniably concrete, a powerful assertion of physical and conceptual presence in the world.

Even a portrait of an animal, through the artist's unique style and emotional connection, can become a kind of self-reflection, a projection of tenderness or intensity, a subtle self-portrait of the artist's empathy or personality. It reminds me of how the definitive guide to understanding form and space in abstract art-principles-perception-and-practice can reveal the artist's intent even without literal representation. It's about capturing a kindred spirit, a reflection of the artist's inner world projected onto another being.

- Mixed Media and Collage: Combining different materials like paint, paper, fabric, photographs, found objects, or digital elements allows for a highly textured, layered, and often fragmented exploration of identity. Think of tearing down and reassembling images, much like we often do with our own self-perceptions, creating a visual metaphor for the constructed nature of self. Artists like Hannah Höch, a pioneer of Dadaism, used collage as a powerful tool to critique society and explore fragmented identities, especially in post-war Germany, reflecting the shattered realities of the time. Her photomontages, often featuring her own image, challenged traditional notions of beauty and female representation, asserting a radical new vision of self. Think also of Robert Rauschenberg's 'combines,' which blended painting and sculpture with found objects, creating a chaotic yet cohesive self-representation of his environment and experiences. It’s like creating a visual diary from a collection of moments and textures, a more complex and nuanced understanding of who you are, or who you're pretending to be, a veritable archaeological dig into the self, reflecting the my journey with mixed-media:-blending-materials-for-abstract-expression of contemporary artists.

This multidisciplinary approach allows for an expansive and inclusive definition of self-portraiture, capable of capturing the complex realities of modern identity, blurring the lines between disciplines and challenging conventional artistic boundaries.

- Photography: Beyond mere casual snapshots, photographic self-portraits can be incredibly sophisticated, requiring meticulous planning. The very invention of photography in the 19th century offered artists a new, seemingly objective tool for self-representation, opening up a whole new realm of possibilities. Early pioneers quickly turned the lens on themselves, experimenting with this novel medium. Artists employ elaborate staging, nuanced lighting, costume, and increasingly, digital manipulation to convey complex ideas, construct personas, or perform identity. Think of Man Ray's surrealist self-portraits, or Florence Henri's experimental works with mirrors and reflections. Cindy Sherman, whom I mentioned earlier, is an undisputed master of this genre, turning the camera inward to explore outward archetypes and challenge media representations of women. But think also of Robert Mapplethorpe's stark, powerful self-portraits, which often explored themes of sexuality and identity with unflinching directness, or Nan Goldin's raw, intimate visual diaries that chronicle personal life and subcultures, capturing a deeply personal and often vulnerable self. Photography offers an immediate, yet endlessly malleable, way to represent the self, blurring the lines between documentation and artifice, and contributing significantly to the history of photography as fine art, allowing for both candid immediacy and meticulously constructed narratives of self. Other photographers like Francesca Woodman explored themes of identity, femininity, and the body in haunting and poetic self-portraits, often within decaying environments, while Dawoud Bey creates large-scale, intensely present self-portraits that engage with issues of race, community, and representation. The photographic self-portrait, in its myriad forms, remains a powerful medium for both documentation and profound artistic inquiry, an ever-evolving reflection of the self in the digital age.

- Performance Art/Video Art: In contemporary art, the artist's body itself can become the living, breathing medium, with the self-portrait evolving into a live or recorded performance. These dynamic forms explore identity, temporal experience, and direct interaction, often challenging the audience to confront preconceived notions of selfhood and representation. Think of Marina Abramović's demanding, often painful, self-explorations, where her endurance and presence become the essence of the self-portrait, pushing the very definition of what art can be, and often inviting audience participation to further explore boundaries. Or consider Vito Acconci's early video works that turned the camera on himself in intimate, sometimes unsettling ways, exploring the boundaries of public and private self and the nature of surveillance. These artists transform their bodies and experiences into living sculptures and narratives, making the act of being, itself, a work of art. It's the ultimate act of turning oneself into art, in real-time, often pushing physical and psychological limits to reveal deeper truths about the human condition and the ephemeral nature of existence. Other notable performance artists using their bodies for self-portraiture include Ana Mendieta, who explored themes of identity, feminism, and spiritual connection through her 'earth-body' works, and Chris Burden, whose often dangerous and provocative performances directly confronted physical and psychological limits. These radical approaches redefine the boundaries of self-portraiture, transforming the artist's very existence into a dynamic and provocative work of art.

- Conceptual Self-Portraits: Moving beyond literal visual resemblance, these works prioritize the idea or concept of self. They might use text, found objects, interactive installations, or even absence to explore identity, memory, or presence without a direct visual likeness. It's about provoking thought rather than depicting an image. For instance, an artist might present a collection of objects that are deeply personal to them, allowing the viewer to construct a 'portrait' of the artist through these chosen artifacts. Or they might use a series of written statements, or even the absence of a physical image, to prompt reflection on identity. It's like a scavenger hunt for identity, where the meaning is constructed as much by the viewer as by the artist, making the audience an active participant in the creation of meaning. These are often the most intellectually stimulating self-portraits, challenging our very definitions of what a "portrait" can be, moving beyond the visual to the purely conceptual realm of ideas and associations. Artists like Felix Gonzalez-Torres, through his 'portraits' made of endlessly replenishable candy piles or stacks of paper, transformed personal narratives into poignant conceptual statements on love, loss, and memory, where the absence of a literal image speaks volumes about the individual.