Post-Impressionism: Art's Revolution, My Journey, & Modern Art's Roots

Explore Post-Impressionism through an artist's eyes. Uncover its emotional depth, structural innovations, key figures, and how this rebellious era ignited modern art and influences abstract creation today.

Post-Impressionism: An Artist's Guide to Art's Emotional & Structural Revolution

I've always been drawn to art that feels more than it just sees. There was a period in my own studio, early on, when I found myself meticulously trying to render reality – chasing the perfect shade, the exact curve. But something felt... hollow. It was only when I allowed my inner landscape, my emotions, to guide the brush, letting colors clash or forms dissolve, that my work truly came alive. This personal journey of breaking free from strict representation deeply resonates with the Post-Impressionist movement, a period where artists collectively decided the camera could capture the surface, but paint should delve into the soul. For me, finding solace and a little bit of beautiful chaos in my own abstract art – like a canvas where a seemingly random splash of crimson finds perfect harmony with a brooding blue – is a direct echo of that powerful shift. Post-Impressionism isn't just a bridge; it's a bustling marketplace of ideas that fundamentally challenged the very notion of what art should be. It was a bold rebellion against the limitations of Impressionism, paving the way for everything from Cubism to Expressionism. And, honestly, who doesn't love a good rebellion? Especially when it's as colorful, emotionally charged, and intellectually rigorous as this one – a glorious refusal to simply accept the status quo. In this comprehensive guide, we'll journey through the genesis of this pivotal era, intimately meet its principal figures and their groundbreaking works, delve into the diverse techniques that defined it, and ultimately explore its profound and lasting legacy on art, including my own creative journey.

From Fleeting Moments to Enduring Realities: The Genesis of a Movement

You know how sometimes you look at a beautiful sunset and just want to feel it, not just meticulously document every shade of orange? That, in a nutshell, is the heart of Post-Impressionism. For me, the way the sky bleeds from soft lavender to fiery orange at dusk isn't just a visual phenomenon; it's a visceral experience of time passing, of nature's profound, fleeting beauty, and I want my art to capture that deeper resonance. After the Impressionists had their glorious run capturing the fleeting moment – the transient effects of light and atmosphere, what the eye objectively sees (optical realism) – a new generation of artists emerged in the late 19th century feeling a bit… limited. This was building on earlier movements like Realism, which, while distinct from Impressionism, had already shifted focus to depicting contemporary life and social realities, further setting the stage for art to engage with the world in new ways. The advent of photography, for instance, challenged painting's role as a mere recorder of reality, prompting artists to ask what painting could do that photography couldn't. Interestingly, photography also started to inspire artists with its novel ways of cropping and framing subjects, influencing compositions in unexpected ways. This question, for me, remains eternally relevant: what can I express with paint that a lens cannot? Rapid industrialization was transforming cities, creating new social structures and psychological states that artists felt compelled to explore. And then there were the whispers of emerging psychological theories, hinting at the vast, unexplored depths of the subconscious mind – ideas from thinkers like Sigmund Freud, which encouraged a profound introspection, pushing artists to look inward, beyond the superficial to explore dreams, symbols, and underlying human motivations. The world was changing rapidly, and artists craved a deeper engagement than merely depicting the surface. Impressionism, with its focus on the objective visual sensation, started to feel insufficient. They wanted more than fleeting impressions; they yearned for depth, structure, personal expression, and symbolic meaning. Of these, the pursuit of personal expression and symbolic meaning resonates most profoundly with my own artistic journey; it's the core of why I paint abstractly.

![]()

It wasn't a unified school, mind you. More like a bunch of brilliant individuals, each wrestling with their own artistic demons and coming up with wildly different solutions. Trying to put them all in one box feels a bit like herding particularly vibrant, opinionated cats. This era was also marked by a bold rebellion against the established academic art world and its conservative Salons, leading to alternative exhibition spaces like the Salon des Indépendants, where these daring artists, often struggling for recognition, could showcase their work without censorship and on their own terms. But they all shared a common desire to push beyond Impressionism's emphasis on pure visual sensation. They wanted art to convey emotion, symbolism, and a more enduring, subjective reality. It was as if they collectively decided, "Okay, the camera can capture what the eye sees; now, what can the soul see, or what deeper truths can we express?" For me, as an artist, that question is eternally fascinating and foundational to my own work. This shift wasn't just stylistic; it was a profound philosophical reorientation of what art could achieve, laying crucial groundwork in the larger history of art. It's a philosophical stance that continues to fuel contemporary art's relentless quest for deeper meaning and personal truth, echoing in every brushstroke that dares to look inward.

The Mavericks and Their Masterpieces: When Rules Were Made to Be Bent

If Impressionism was a polite garden party, Post-Impressionism was a vibrant, slightly chaotic salon where everyone had a strong opinion and a unique way of expressing it. Let’s meet some of the main characters who shook things up.

Vincent van Gogh: The Heart on the Canvas

Ah, Van Gogh. The man who painted not just what he saw, but what he felt. His work is a raw, unadulterated outpouring of emotion, and frankly, I'm a sucker for that kind of intensity. You look at a Van Gogh, and you don't just see a landscape; you feel the wind, the heat, the sheer, boundless energy of the artist. His thick, swirling brushstrokes and vibrant, often clashing colors scream passion. I often find myself channeling his audacious use of impasto when I'm building up texture in abstract art, aiming for that same raw, tactile impact. It’s no wonder he has his own ultimate guide to Van Gogh.

![]()

Seriously, how do you not get lost in the swirling sky of "The Starry Night"? It's a universe unto itself. And "Starry Night Over the Rhône"? Pure magic, a peaceful yet deeply emotional evocation of twilight's mystery. He wasn't afraid to let his inner world bleed onto the canvas, and that takes courage.

His portraits, like his famous self-portraits, are equally gripping, full of texture and psychological depth. It’s almost like you can feel the scratchy beard and the intense gaze.

And his landscapes, like "Village Street in Auvers" or "Almond Blossoms," show that even in seemingly peaceful scenes, his unique vibrant energy is unmistakable. "Almond Blossoms," in particular, feels like an explosion of hope and renewal, a feeling I often strive to capture in my own spring-inspired pieces.

![]()

![]()

Van Gogh's legacy is a testament to the power of raw emotion, showing us how the canvas can become a direct extension of the artist's soul.

Paul Gauguin: The Symbolist Wanderer & Pioneer of Primitivism

Moving from intense emotion to profound symbolism, we encounter Paul Gauguin, the rebel who famously ran off to Tahiti seeking an "exotic" and "primitive" art, disillusioned with European society. His quest to escape the perceived artificiality of modern life for a more authentic, spiritual existence deeply resonates with the artistic longing for deeper meaning beyond the superficial. His unique style, known as Synthetism, involved simplifying forms, using large, flat areas of bold, often non-naturalistic color, and enclosing them with strong outlines. This approach, often called Cloisonnism, was directly influenced by Japanese woodblock prints and medieval stained glass, emphasizing decorative qualities over realistic depiction. It wasn't about capturing what the eye saw, but about synthesizing observed reality with the artist's memory, imagination, and subjective emotional response, conveying symbolic meaning and a spiritual quality. His work feels like a dream, a narrative told through color and form rather than realistic depiction, often drawing on non-Western art forms and spiritual beliefs, and showing a significant influence from Japonisme – Japanese woodblock prints with their flat areas of color and strong outlines. It’s a fascinating tangent that often leads to discussions about decoding abstract art: finding meaning in non-representational works. Gauguin's vibrant, often enigmatic compositions invite us to look beyond the surface, pushing us to find deeper, symbolic truths, and question the supposed superiority of Western civilization's artistic traditions.

Paul Cézanne: The Architect of Modern Art

Then there's Cézanne, the quiet revolutionary, often called the "father of modern art." He wasn't interested in capturing light or fleeting emotion in the same way. He was obsessed with structure, with reducing natural forms to their geometric essentials: cylinders, spheres, cones. He famously said he wanted to "make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of the museums," and he achieved this by meticulously analyzing and reconstructing forms. This intellectual pursuit of underlying structure – breaking down what you see to build it back up with a new understanding – often influences how I approach the composition of my own abstract pieces. It’s like searching for that foundational geometry within amorphous shapes, asking myself: how can I reveal the inherent stability or tension of a form, even if it's purely imagined? His landscapes and still lifes, with their fragmented planes and suggestion of multiple viewpoints, don't just depict; they deconstruct and reassemble reality, revealing its underlying geometry. This analytical approach, which allowed for seeing objects from several angles simultaneously and breaking them into their constituent parts, laid the undeniable groundwork for Cubism, profoundly influencing pioneers like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque by providing a new way to represent three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional canvas. It’s a different kind of intensity, a deep dive into the foundational elements of visual perception. Cézanne's enduring legacy lies in his radical rethinking of artistic space and form, inviting future generations to deconstruct and reconstruct reality.

Georges Seurat & Paul Signac: The Science of Color (and Dots)

On a completely different end of the spectrum, favoring scientific precision over raw emotion, we have Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, the masterminds behind Pointillism. This technique is a specific application of Divisionism, a broader theory rooted in scientific color principles (like those of chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul) that involves separating colors into individual, pure pigments applied in distinct strokes or dots. If Van Gogh was a volcanic eruption of emotion, these guys were meticulous scientists, painstakingly applying tiny dots of pure color to the canvas. The revolutionary idea was that your eye, not the artist's palette, would optically mix these juxtaposed dots of color, creating a more vibrant and luminous effect than traditional blending. It's truly fascinating, like they were saying, 'Let's use science to achieve unparalleled vibrancy and a dynamic interplay of color!' The sheer patience required for this approach is something I still marvel at.

To be clear about these terms:

- Divisionism: The scientific theory of separating colors into individual, pure pigments to be optically mixed by the viewer's eye.

- Pointillism: The specific technique of applying these pure, separated colors in small, distinct dots.

You look at a piece like Henri-Edmond Cross's "Les Pins" or "The Pink Cloud," and you just marvel at the sheer dedication and luminous effect achieved. "Les Pins" makes me think of the shimmering heat of a summer day, a feeling perfectly conveyed by those myriad tiny dots.

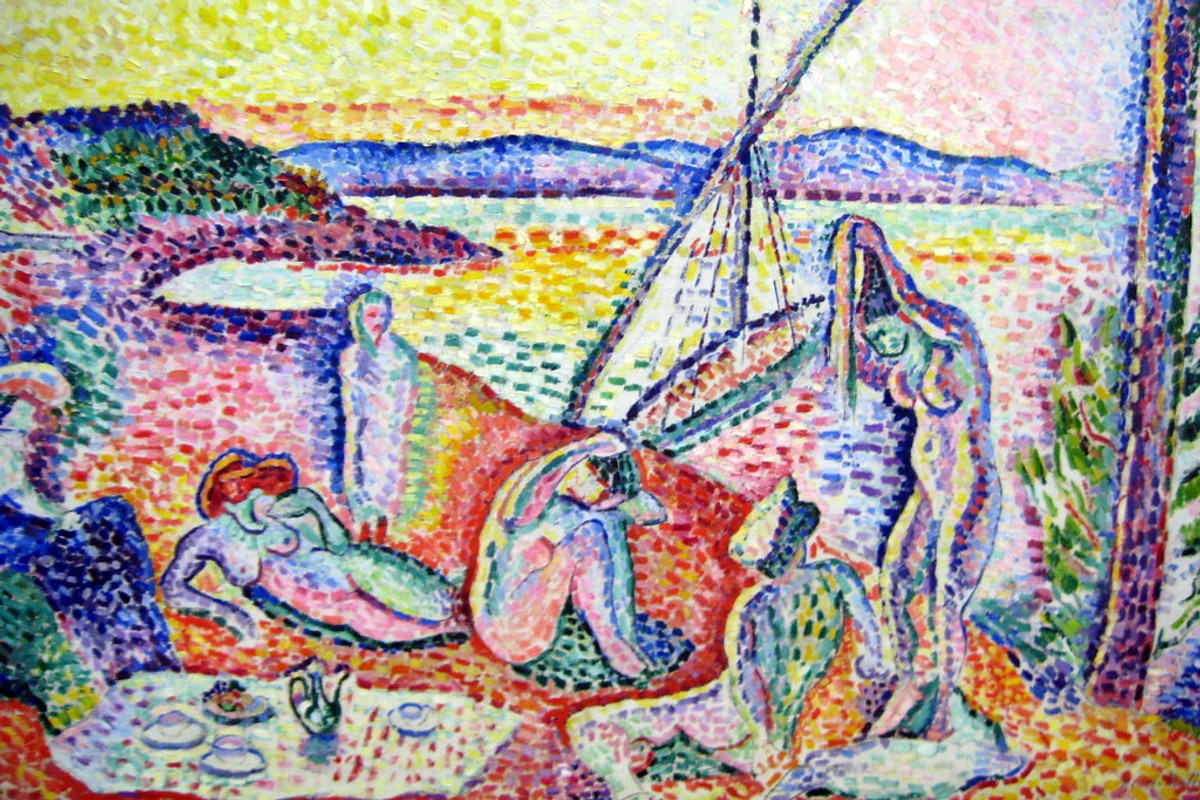

Or consider Henri Matisse's early Pointillist work, like "Luxe, calme et volupté," which shows how even future Fauvist masters explored these meticulous color theories, foreshadowing the bold color experiments that would define his later work.

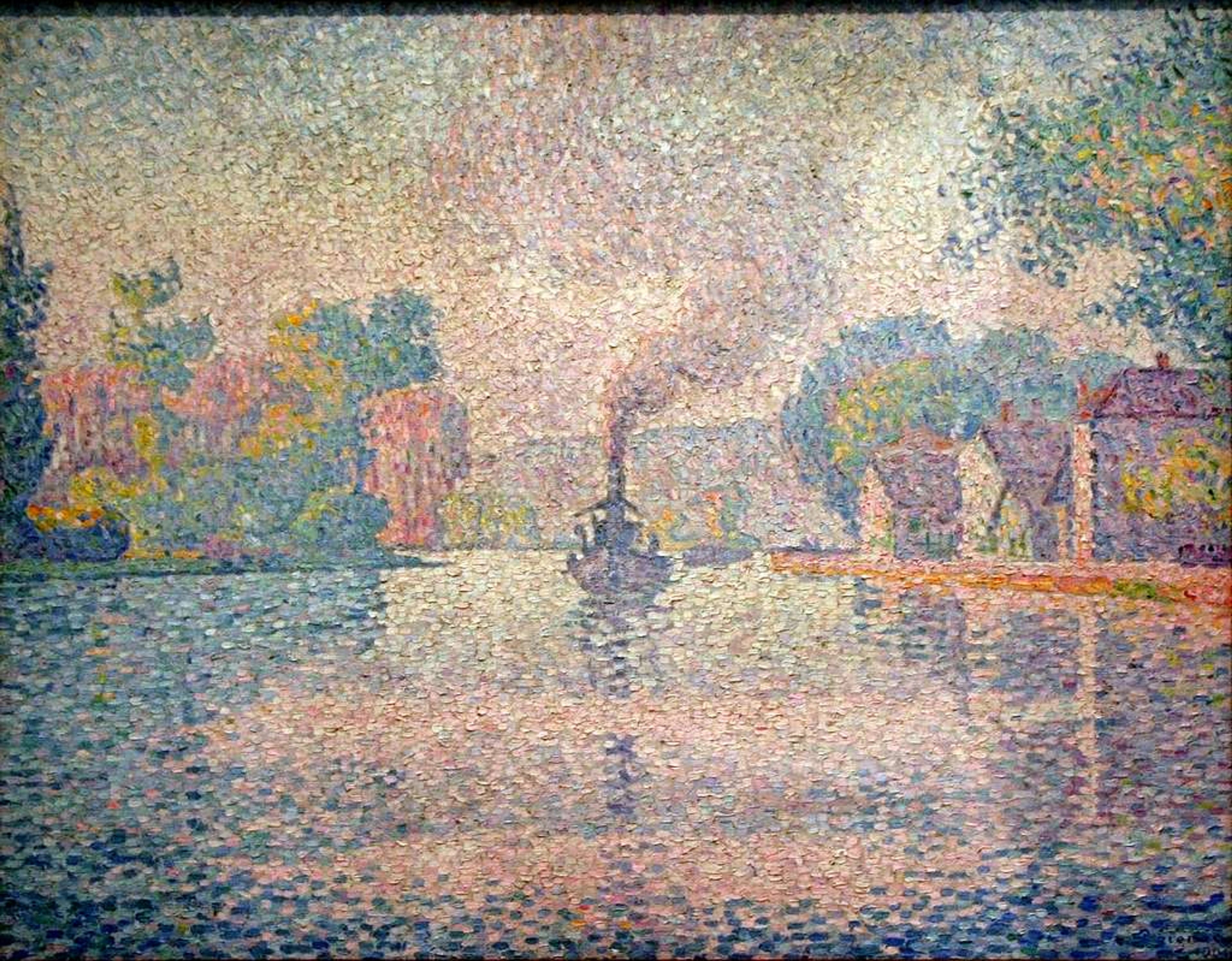

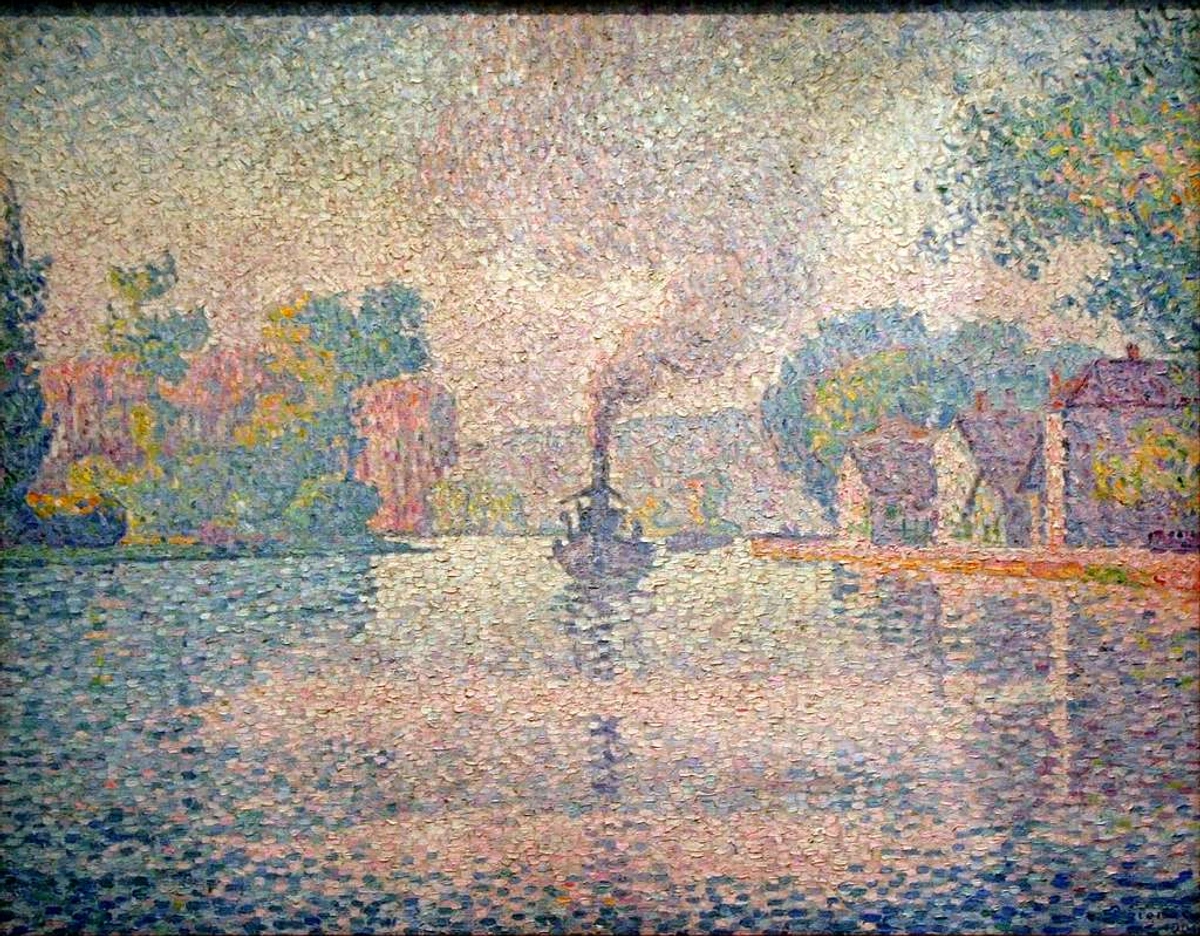

Signac's "Golfe-Juan" is equally mesmerizing, showing how this technique could be applied to coastal landscapes, creating a shimmering, almost vibrating quality that perfectly captures the play of light on water. The "luminous detail" of his "L'Hirondelle Steamer" on the Seine River, capturing a bustling scene with such precision, certainly makes you think differently about how artists use color in all its forms, and you can dive deeper into this fascinating method with our ultimate guide to Pointillism. Seurat and Signac demonstrated that art could be both deeply emotional and rigorously scientific, a beautiful blend of precision and optical illusion.

Beyond the Big Names: Other Voices in the Post-Impressionist Chorus

While the "big four" undeniably shaped Post-Impressionism, the movement was a fertile ground for many other artists who pushed boundaries in their own unique ways. One notable figure is Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose vibrant, often stark depictions of Parisian nightlife, dance halls, and brothels captured the essence of fin-de-siècle society. His distinctive style, characterized by strong outlines, flattened forms, bold, flat areas of color, and unconventional cropping (significantly inspired by Japonisme – Japanese woodblock prints with their flat areas of color and strong outlines), captured the raw energy and psychological depth of fin-de-siècle Parisian nightlife. What I find particularly compelling about Lautrec is his unflinching honesty and empathy in portraying the human condition, often with a poignant undercurrent beneath the glittering surface. He was also a pioneer in lithography, creating iconic posters that elevated advertising into an art form, making him a crucial chronicler of his era and a master of capturing movement and character with economy of line, truly bringing art to the public sphere and influencing graphic design for decades to come.

Further extending the symbolic and decorative possibilities were a group of artists known as The Nabis (from the Hebrew word for 'prophet'). Their name was no accident; they believed art should be a new kind of 'revelation' – a spiritual and decorative arrangement, intimately linked to emotion and spirit. This included figures like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard. Heavily influenced by Gauguin's Synthetism and his emphasis on flat planes of color and decorative patterns, the Nabis rejected the illusionistic tradition in favor of art that was intentionally ornamental, often drawing inspiration from Japanese prints and stained glass. Their willingness to blur the lines between fine art and decorative arts profoundly influences my own practice, where I see little distinction between a framed canvas and a beautifully designed, functional object; beauty and meaning can reside in both. They blurred the lines between fine art and decorative arts, seeing painting, posters, and book illustrations as equally valid expressions of a subjective, symbolic vision. Their work, often intimate and domestic, emphasized mood and atmosphere through simplified forms and rich color harmonies. This period also saw the broader influence of the Symbolist movement in literature and visual arts, which sought to express inner experiences and ideas through symbolic imagery, often drawing on mythology, dreams, and spiritual themes. This deeply resonated with the Post-Impressionist drive for meaning beyond mere observation and aligning perfectly with my own abstract exploration of internal landscapes.

A Spectrum of Styles: Key Innovations and Techniques

What makes Post-Impressionism so captivating is not just the individual genius of its artists, but the diverse array of stylistic innovations they pioneered. It truly was a period of intense experimentation, where artists felt free to forge their own paths. It reminds me a bit of my own studio on a particularly experimental day, a beautiful mess of possibility.

- Expressive Brushwork & Impasto: Think Van Gogh's thick, swirling applications of paint, where the texture itself conveys emotion and energy, creating a dynamic surface that's almost sculptural. For me, the physical act of building up impasto painting with a palette knife is a deeply satisfying, almost meditative process, where the materiality of the paint becomes as expressive as its color.

- Pointillism & Divisionism: As seen with Seurat and Signac, this involved meticulous application of small, distinct dots of pure color (Pointillism), or broader strokes (Divisionism), relying on the viewer's eye to optically blend them into luminous hues, based on scientific color theories.

- Synthetism, Cloisonnism & Flat Planes of Color: Gauguin's approach often involved simplifying forms and using large, flat areas of unmodulated, often non-naturalistic color, enclosed by strong outlines (Cloisonnism). This emphasized symbolic meaning, the artist's memory and imagination, and decorative qualities over realism, a deliberate move away from Impressionism's dissolved forms.

- Structural & Geometric Analysis: Cézanne's revolutionary method of breaking down forms into their underlying geometric components – cylinders, spheres, cones – sought to reveal the inherent structure of nature, laying the foundation for abstract and cubist art. His "Mont Sainte-Victoire" series, for example, reveals the enduring power of nature's underlying forms, almost like a geological X-ray.

- Symbolic & Non-Naturalistic Color: Beyond merely depicting light, color was employed to evoke mood, convey symbolic meaning, or express internal states, leading to vibrant, sometimes clashing, and emotionally charged palettes – a stark contrast to Impressionism's objective color application. I often find myself deliberately using non-naturalistic color, like a searing orange sky, to amplify a feeling of drama or urgency in my abstract landscapes.

- Emphasis on Line & Outline: In contrast to Impressionism's dissolved forms and indistinct edges, many Post-Impressionists, like Gauguin and Lautrec, reasserted the importance of strong lines and clear outlines, giving forms more definition and symbolic weight.

- Varied Subject Matter & Symbolist Influence: While Impressionists often depicted bourgeois leisure, Post-Impressionists explored a much broader range: from Seurat's scientific analysis of urban life ("A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte" with its curious blend of leisure and formal precision) to Gauguin's exotic, spiritual quests in Tahitian scenes often imbued with mythological and spiritual symbolism, the raw turmoil of Van Gogh's inner world conveyed through his landscapes and self-portraits (each a window into a soul on fire), Cézanne's foundational structure of nature in his still lifes and "Mont Sainte-Victoire" series, and Toulouse-Lautrec's gritty realities of modern Parisian nightlife (a masterclass in character study).

Common Threads: What United These Diverse Visionaries?

Given the incredible individuality of these artists, you might wonder what truly ties them together under the banner of Post-Impressionism. It's less about a unified style with a manifesto and more about a shared attitude – a collective spirit of rebellion and a direction taken by individual artists reacting against Impressionism. Here are the common threads that always jump out at me, revealing a collective desire for deeper artistic engagement:

- Subjective Expression & Emotion: This is perhaps the most significant departure. Instead of striving for objective optical reality, artists prioritized their personal feelings, psychological states, and interpretations. Art became a window into the artist's soul, not just a mirror reflecting the world. As an artist, navigating the balance between raw emotion and controlled execution is a constant, exhilarating challenge, a dance between heart and hand.

- Symbolic & Expressive Use of Color: Color was liberated from its purely descriptive role. It was used to evoke emotion, create mood, or convey symbolic meaning, often in a non-naturalistic way. Think of Van Gogh's intense, emotionally charged yellows or Gauguin's vibrant, unnatural hues telling a story. For me, color is not just a visual element; it's a primal language, capable of communicating profound depths without a single recognizable form.

- Structured Forms and Order: Many Post-Impressionists sought to reintroduce a sense of order, solidity, and intellectual rigor that Impressionism sometimes eschewed. While Cézanne and the Divisionists pursued a geometric or scientific order, even Van Gogh, in his swirling compositions, imposed an emotional order on chaos. In my own abstract work, even in its most spontaneous moments, I'm always subconsciously seeking an underlying structural integrity, a 'hidden' order that gives the chaos meaning.

- Emphasis on Line & Outline: While Impressionism famously dissolved forms with light and indistinct edges, many Post-Impressionists, like Gauguin and Lautrec, reasserted the importance of strong lines and clear outlines, giving forms more definition and symbolic weight.

- Rejection of Pure Naturalism: Across the board, there was a conscious move away from merely imitating nature. This wasn't a dismissal of reality, but a profound intention to transform, interpret, and imbue it with deeper meaning beyond simple mimesis. For me, this is the very essence of abstract art: to take reality, distill it, and present its core truth in a new, felt way.

- Embrace of Individual Artistic Freedom & Rejection of Academic Conventions: This was a period defined by artists forging their own unique paths, fiercely independent from the rigid rules and expectations of the traditional art academies and Salons. They prioritized personal vision over established norms.

- Diverse Techniques: From Van Gogh's swirling impasto to Seurat's precise dots to Gauguin's flat planes of color, there was no single "Post-Impressionist style." It was a rich tapestry of individual approaches, united by a shared goal of moving beyond mere impression.

So, what does this collective drive for deeper engagement mean for us today, as artists and viewers?

Why It Matters: The Genesis of Modern Art (and My Own Creative Journey)

Post-Impressionism wasn't just a fleeting moment in art history; it was a seismic shift, arguably the true genesis of modern art. It decisively opened the floodgates for the 20th century, proving that art didn't have to be a mirror reflecting objective reality. It could be a window to an inner world, a laboratory for scientific color theory, a blueprint for geometric deconstruction, or a vehicle for profound symbolic narrative. This era, emerging from a rapidly changing world – marked by industrialization, burgeoning psychological thought, and global cultural exchange – saw artists reflecting societal shifts through deeply personal and structural innovations, pushing against the artistic conservatism of the past.

Think about it: Without Van Gogh's pioneering emotional intensity and non-naturalistic color, would we have the raw power of Expressionism and Fauvism's bold hues? Without Cézanne's structural innovations, his geometric reduction of forms, and his concept of "passage" (where planes subtly merge rather than abruptly meet, bridging distinct areas), which profoundly influenced artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, would Cubism have emerged? This movement laid the essential groundwork for so much that followed, including, in a very direct way, the bold and expressive world of abstract art that I find myself immersed in. The Post-Impressionists taught us that subjective vision and emotional truth are as valid, if not more so, than objective representation. This ethos of internalizing and reinterpreting reality is precisely what fuels my own abstract practice, where color and form become a language for expressing the unseen. My "Echoes of Emotion" series, for instance, directly taps into the Post-Impressionist belief that color alone can convey profound feeling, using broad strokes and vibrant hues to evoke internal states rather than external scenes. It's all connected, you see – a grand, beautiful timeline of human creativity, where each bold step forward builds on the daring experiments of the past. You can even trace some of these influences in my artist journey timeline.

My Own Little Detour into Post-Impressionist Echoes: How it Sneaks Into My Studio

While my art leans heavily into the abstract, I often find myself reflecting on the bold decisions and sheer artistic courage of the Post-Impressionists. The freedom they took with color, the audacity to inject personal emotion into every brushstroke, the intellectual rigor in dissecting form – that resonates deeply with my own practice. For instance, in my "Chromatic Whispers" series, where expansive fields of color evoke particular moods, I'm undeniably channeling Gauguin's belief that color can carry profound emotional weight independent of realistic depiction. Or when I'm building up texture in abstract art with thick, deliberate strokes, aiming for a raw, tactile impact, I'm thinking of Van Gogh's impasto, allowing the paint itself to speak volumes. And in my "Deconstructed Landscapes" series, the way I break down natural forms into essential shapes, then reassemble them with an emphasis on color and line, is a direct echo of Cézanne’s analytical approach, albeit with a contemporary, abstract twist.

Sometimes, when I'm mixing a particularly audacious shade of blue or a fiery red, I'll think, "Would Van Gogh approve of this intensity?" (Probably, yes, with a nod and a slightly wild look in his eye). Or when I'm meticulously building up layers of color and considering the underlying forms, I wonder if Cézanne would appreciate the pursuit of structure, even if mine is more ethereal and implied. It’s a continuous dialogue between the masters of the past and my own contemporary explorations, a beautiful chaos of influence. And if you're curious to see how these echoes manifest, you can always explore my collection of available art or visit my museum space in 's-Hertogenbosch if you're ever in the Netherlands.

FAQs: Because We All Have Questions (and I'm Always Reflecting on the Answers)

Here are some common questions I hear, or sometimes even ask myself late at night when contemplating the universe and art history.

- What is Post-Impressionism in simple terms? It's an art movement, primarily from the late 19th century (roughly 1886-1905), where artists reacted against the Impressionists' focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere. Instead, they sought to express deeper emotions, use symbolic colors, introduce more structure, and embed personal interpretation into their work. Think of it as Impressionism's more rebellious, introspective, and often more geometrically inclined or symbolically charged offspring. It was a conscious effort to bring back substance and lasting meaning to art.

- Who are the main Post-Impressionist artists? The "big four" generally include Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Georges Seurat. Other significant figures include Paul Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and members of The Nabis like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, whose unique contributions collectively define the movement's rich tapestry. For more on one specific style, check out our ultimate guide to Pointillism.

- How is Post-Impressionism different from Impressionism? While Impressionism focused on capturing objective optical reality through light and color, often depicting everyday scenes with visible brushstrokes and dissolving forms, Post-Impressionism was more about subjective expression. Post-Impressionists emphasized emotion, symbolism, structure, and often used color more expressively and less naturalistically, actively rejecting the academic conventions of the past. Impressionists asked, "What does it look like right now?" Post-Impressionists asked, "What does it feel like, what deeper meaning does it convey, or what structure underpins it?" This fundamental difference marked a pivotal shift in artistic intent.

- How was Post-Impressionism received by the public and critics at the time? Like many avant-garde movements, Post-Impressionism initially faced considerable skepticism, ridicule, and even outright hostility from the conservative art establishment and a public accustomed to more traditional, realistic art. Their bold use of non-naturalistic color, distorted forms, and subjective expression was often seen as crude, childlike, or even degenerate – a direct challenge to established artistic and societal norms. However, a small but growing number of progressive critics and collectors began to recognize the profound originality and significance of these artists, laying the groundwork for their eventual widespread acclaim and crucial place in art history. It's a powerful reminder that truly groundbreaking art often challenges initial perceptions, demanding courage from both the artist and the viewer to embrace the new.

- What are some common misconceptions about Post-Impressionism? A common misconception is that Post-Impressionism was a single, unified style, rather than a diverse collection of individual artists reacting against Impressionism in distinct ways. Another is that their use of bold, sometimes non-naturalistic color was a sign of lack of skill, when in fact it was a deliberate choice to convey emotion or symbolic meaning, often backed by rigorous artistic theory or profound personal conviction. They weren't just being chaotic; they were forging new orders.

- Did Post-Impressionism have a big impact? Oh, absolutely! It was a crucial bridge between 19th-century art and 20th-century modern art. Its emphasis on personal expression, structured forms, and symbolic color directly influenced movements like Expressionism (with its intense emotionality) and Fauvism (with its bold, non-naturalistic use of color), and especially paved the way for Cubism and eventually abstract art. It taught us that art could be about so much more than just what the eye sees, fundamentally altering the trajectory of Western art, pushing it towards abstraction and deeper psychological engagement.

Conclusion: Beyond the Fleeting, Towards the Eternal

So, there you have it: my deeply personal exploration of Post-Impressionism, a movement that, for me, embodies the very essence of artistic courage. It was a period where artists dared to look at what was established and ask, "What if we did it this way instead? What if we pushed it further, deeper, more personally?" It's a profound reminder that art isn't just about technical skill or objective representation; it's about vision, emotion, structure, symbolism, and an unshakeable desire to communicate something profoundly human – a raw, unfiltered truth. This ethos of bold experimentation and personal truth-telling is a lesson I carry into my own studio every single day, a constant dialogue with these pioneering spirits who redefined what art could be and, in doing so, shaped my own artistic vocabulary. It's about leaving your unique, unmistakable mark on the world, much like I try to do with the art I create. Ultimately, Post-Impressionism reminds us that art is a living, breathing conversation across time, constantly evolving yet rooted in timeless human quests for meaning and expression.