The History of Art: An Artist's Personal Journey Through Time

Dive into the history of art through my eyes! This isn't just a dry timeline; it's a personal journey through periods, movements, and styles, sharing why it matters to me as an artist, how materials and patronage shaped creativity, and how it might spark your own inspiration. From ancient wonders and global traditions to today's vibrant scene, let's explore together.

The History of Art: An Artist's Personal Journey Through Periods, Movements, and Styles

Okay, let's talk about the history of art. For a long time, maybe like you, I thought it was just about memorizing dates, names, and stuffy facts. But honestly? Diving into art history has been one of the most eye-opening, inspiring, and sometimes, yes, even funny journeys I've taken as an artist. I remember standing in front of a tiny, ancient Egyptian sculpture once, maybe just a few inches tall, and feeling this weird, electric jolt – a direct line connecting me, a modern artist messing around with paint and pixels, to someone thousands of years ago who felt the same urge to shape something beautiful or meaningful out of the world around them. It wasn't a date or a name that hit me, but the sheer, persistent humanity of it. It's not just a record of what people made; it's the sprawling, messy, utterly human story of creativity across time and cultures. It's a unique window into the values, beliefs, fears, and aspirations of societies and individuals – a reflection of everything from technological leaps to philosophical head-scratchers, religious fervor, political drama, and that persistent, beautiful human drive to just make things and find pleasure in looking at them.

Understanding what art is often feels like it starts here, with the echoes of the past. This guide? It's my attempt to walk you through the major periods, movements, and key developments, mostly focusing on the Western path because that's where my own formal study began, but absolutely acknowledging the incredible global tapestry it's woven into and how those threads sometimes intertwine. I wanted to create this guide because I believe a foundational understanding isn't just for academics; it's fuel for anyone who loves art, makes art, or just wants to see the world a little differently. Studying art history can unlock incredible art inspirations and deepen our connection to the wild, messy, beautiful human experience. So, if you've ever wondered why any of this matters, especially to someone like me who spends their days in a studio, the next section is for you.

Why I Think Studying Art History is Totally Worth It (And Maybe You Will Too)

Forget the dusty textbooks for a second. For me, art history isn't about rote memorization. It's about gaining superpowers:

- Time Travel (Seriously): Art objects are like little time capsules. They reveal the beliefs, values, and daily lives of the people who made and saw them. Looking at a Roman bust or a medieval altarpiece? It's the closest I get to actually feeling what it was like to live back then. I remember seeing a Roman portrait bust in a museum once, and the sculptor had captured this guy's slightly grumpy expression and thinning hair with such precision, I felt like he could just sigh and tell me about his day. That connection across millennia? Mind-blowing.

- Tracing the Human Heartbeat: See how fundamental human concerns – life, death, love, power, spirituality – have been wrestled with and expressed visually for thousands of years. It's a reminder that we're all part of a long, ongoing conversation.

- Spotting the Shifts: Art is often right there on the front lines, reflecting and sometimes even causing social, political, and technological transformations. Want to understand a historical moment? Look at the art they were making.

- Leveling Up Your Eyes: Learning to analyze and interpret visual information – composition, color, form – is crucial in our image-saturated world. It's like learning how to read a painting, and it makes looking at any image, historical or contemporary, so much richer.

- Appreciating the Craft: Understanding the evolution of artistic styles, materials, and techniques gives you a whole new appreciation for the sheer skill and innovation involved. How did they do that?!? (Seriously, try grinding pigments for fresco sometime. It's a workout.)

It's a journey of discovery, and honestly, it just makes the world feel bigger and more connected.

Prehistoric Art (c. 40,000 – 4,000 BCE): The First Marks

This is where it all begins, way back in the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods. Imagine the world then – raw, untamed, full of mystery. And humans, in the midst of it all, felt compelled to make marks. It blows my mind. They used natural pigments like ochre and charcoal, applying them to cave walls or shaping small figures from bone or stone. The materials were literally the earth around them. How did they get paint onto those high cave ceilings? We think they might have used their hands, chewed up pigment and spat it on, or even blown it through hollow reeds – connecting the physical act of making directly to the breath of life.

- Key Examples:

- Cave Paintings: Think Lascaux or Chauvet in France, or Altamira in Spain. Magnificent, dynamic depictions of animals – bison, horses, deer. Were they about hunting magic? Shamanic visions? We don't know for sure, and that mystery is part of the magic. The sheer scale and skill on rough cave walls are incredible.

- Portable Sculptures: Small, often exaggerated female figures like the Venus of Willendorf. Fertility was clearly a big deal, and these little objects feel so personal, so tactile. Made from stone or ivory, they were meant to be held and carried.

- Megalithic Structures: Monumental stone arrangements like Stonehenge in the UK. How did they even move those stones? It speaks to organized labor, maybe astronomical knowledge, or rituals we can only guess at. This is architecture as art, shaping the landscape itself.

- Themes: Survival, fertility, magic, ritual, the raw power of the natural world.

- Significance: This art is proof of early humanity's capacity for symbolic thought and representation. They weren't just surviving; they were thinking, believing, and creating. It shows the fundamental human need to leave a mark, to communicate visually, a drive that still fuels artists today.

Ancient Art (c. 4,000 BCE – 400 CE): Civilizations Rise and Connect

Now we're talking about the art of the first great civilizations in the Near East and Mediterranean. Order, power, religion – these become massive forces shaping creativity. And the patronage of rulers and religious institutions dictates much of what gets made. This era also saw early forms of cultural exchange, with ideas and artistic motifs traveling between regions, laying groundwork for later interconnectedness.

Mesopotamian Art

Flourishing in the fertile crescent (modern Iraq/Syria), successive cultures like the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians left behind incredible artifacts. Art here was often commissioned by rulers or temples to glorify gods, kings, and the state. Materials like durable stone, clay, and glazed brick were chosen for their longevity and ability to convey authority.

- Characteristics: Think massive ziggurats (those stepped temple platforms reaching for the sky – architecture as a link between heaven and earth), intricate cylinder seals (like ancient signatures, carved into stone, used to mark property or documents, often intertwined with the development of cuneiform writing, showing how art and communication were linked from the start), and powerful narrative relief sculptures (often showing rulers being heroic or battles being won, like on the Stele of Hammurabi). And who could forget the vibrant blue Ishtar Gate of Babylon? It's all about projecting power and divine connection through durable materials.

- Focus: Religion, the authority of rulers, law, mythology, and recording history.

- Why it matters today: Mesopotamian art gives us some of the earliest examples of complex narrative and monumental architecture, showing how art was used to build and maintain powerful societies. It's a reminder that art has always been intertwined with power structures.

Egyptian Art

Remarkably consistent for nearly 3,000 years – talk about sticking to a style! This was driven by deep religious beliefs about the afterlife and the divine status of the Pharaoh. Eternity was the goal, and art served this purpose, commissioned almost exclusively by the Pharaoh and the priesthood. Materials like durable stone (granite, basalt), gold, and pigments derived from minerals were chosen for their longevity. Egyptian artistic conventions, while rigid, were incredibly effective at conveying their worldview and even influenced later cultures like the Greeks.

- Characteristics: Monumental architecture that still dwarfs us today (the pyramids, temples like Karnak – built to last forever). A strict visual code using hierarchical scale (bigger means more important, obviously) and composite view (head in profile, eye and torso frontal, legs in profile – a bit like a visual checklist!). Elaborate tomb paintings and reliefs, often using vibrant mineral pigments on plaster, were meant to equip the deceased for the next life. You see scenes of farming, banquets, and daily life, meticulously depicted so the person could enjoy them forever. Sculptures were stylized, aiming for timelessness over realism. Think of the incredible detail in a sarcophagus or a painted papyrus scroll.

- Focus: The afterlife, gods, pharaohs, cosmic order, and achieving eternity.

- Why it matters today: Egyptian art is a masterclass in consistency and purpose. It shows how deeply art can be integrated into a belief system and how powerful visual symbols can remain potent for millennia. Plus, those pyramids? Still mind-boggling. And their influence on early Greek sculpture is a fascinating example of cross-cultural artistic borrowing.

Greek Art

Hugely influential, laying so many foundations for what we call Western aesthetics. The focus shifts towards humanism and idealism – celebrating the perfect human form. Patronage came from city-states, wealthy citizens, and religious sanctuaries. Materials were primarily marble, bronze, and clay.

- Archaic Period (c. 800-480 BCE): Early attempts at depicting the human form, a bit stiff, often with that enigmatic 'Archaic smile'. Think Kouros (male youth) and Kore (female youth) statues carved from marble, and stylized pottery (like black-figure and red-figure vases).

- Classical Period (c. 480-323 BCE): This is often seen as the peak. Idealized, yes, but with a growing naturalism. The invention of contrapposto – that relaxed, weight-shifted stance that makes figures look alive – was a game-changer. Imagine a figure standing with one leg straight, bearing weight, and the other bent and relaxed, causing the hips and shoulders to subtly shift in opposite directions, creating a gentle S-curve in the body. It feels so much more natural than the stiff Archaic pose! Sculptors like Phidias (responsible for the Parthenon sculptures) and Polykleitos (Doryphoros) sought perfect proportions in bronze and marble. Architecture, too, aimed for harmony and balance (the Parthenon again – a masterpiece of proportion, using marble). Painting, though less survives, was highly valued.

- Hellenistic Period (323-31 BCE): Following Alexander the Great's conquests, Greek culture spread, and the art changed. It became more emotional, dramatic, dynamic, and realistic. Think the swirling drapery of the Winged Victory of Samothrace or the intense suffering depicted in Laocoön and His Sons. It's less about calm idealism, more about feeling. Materials remained marble and bronze, pushed to new expressive limits.

- Focus: Humanism, idealism, beauty, order, mythology, and later, emotion and drama.

- Why it matters today: Greek art gave us ideals of beauty and proportion that echoed for centuries. Concepts like contrapposto are still fundamental to figure drawing. It's where the focus really shifts to celebrating human potential. Their architectural orders (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian) still pop up in buildings everywhere.

Roman Art

The Romans were brilliant engineers and administrators, and their art reflects that practicality and focus on empire. They absorbed Greek styles but put their own spin on things, often commissioned by emperors, the state, and wealthy private citizens. They mastered materials like concrete (revolutionary!), marble, and bronze.

- Characteristics: Incredible realism in portrait busts and statues of emperors and citizens – you feel like you could meet these people! Seriously, some of those Roman faces are so specific, with their wrinkles and stern looks, you just know they had very strong opinions about traffic or taxes. Large-scale public works were everywhere – the Colosseum, aqueducts, baths, triumphal arches, and columns covered in narrative reliefs like Trajan's Column, telling stories of military victories. Illusionistic fresco paintings, like those preserved in Pompeii, show a desire to bring the outside world (or fantasy worlds) indoors, using pigments on wet plaster. Roman mosaics, using small pieces of stone or glass, were also widely used for floors and walls, depicting everything from mythological scenes to everyday life.

- Focus: Empire, power, civic duty, ancestor veneration, and documenting history.

- Why it matters today: Roman art shows the power of art as propaganda and a tool for social cohesion. Their architectural innovations, particularly with concrete and the arch, still influence building today. And those portraits? They feel surprisingly modern in their directness. It makes you think about how leaders use imagery today.

Medieval Art (c. 400 – 1400 CE): Faith, Feudalism, and the Divine Light

Also known as the Middle Ages, this period in Europe was heavily shaped by the rise and dominance of Christianity. Art's primary purpose was often religious instruction and devotion – telling biblical stories to a largely illiterate population. The Church was the dominant patron, commissioning vast amounts of art and architecture. While focusing on the spiritual, this era also saw incredible technical innovation, particularly in architecture and glasswork.

Early Christian & Byzantine Art (c. 400-1453)

The focus shifts from earthly realism to the spiritual realm. Figures become more stylized, elongated, and often float against shimmering gold backgrounds symbolizing the divine light. Key forms include stunning mosaics (especially in Ravenna, Italy, using small pieces of glass or stone to create luminous, jewel-like images), revered icons (portable images of saints or Christ, often painted in tempera on wood panels, meant for devotion), intricately decorated illuminated manuscripts (parchment pages painted with vibrant colors and gold leaf, preserving knowledge and illustrating religious texts), and centrally planned churches like the awe-inspiring Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul) – a space that still feels otherworldly, showcasing incredible architectural and mosaic work. Byzantine art, with its emphasis on flat, symbolic forms and gold backgrounds, had a lasting influence, particularly on Eastern Orthodox art.

- Characteristics: Stylized figures, gold backgrounds, mosaics, icons, illuminated manuscripts, domed architecture.

- Focus: Religion, salvation, biblical narratives, the divine realm.

Romanesque Art (c. 1000-1200)

This style is tied to the growth of monasteries and pilgrimage routes. Think massive, solid stone churches with heavy walls and rounded arches supporting barrel vaults. They feel like fortresses of faith! Sculpture is often found on the church portals, especially the tympanums above the doors, depicting dramatic religious scenes in a robust, often stylized manner. Materials were primarily stone for architecture and sculpture, and fresco for wall painting. The architecture was designed to accommodate large numbers of pilgrims and create a sense of solemnity and awe.

- Characteristics: Massive stone churches, rounded arches, barrel vaults, monumental portal sculpture.

- Focus: Pilgrimage, monasticism, religious narratives, architectural solidity.

Gothic Art (c. 1150-1400)

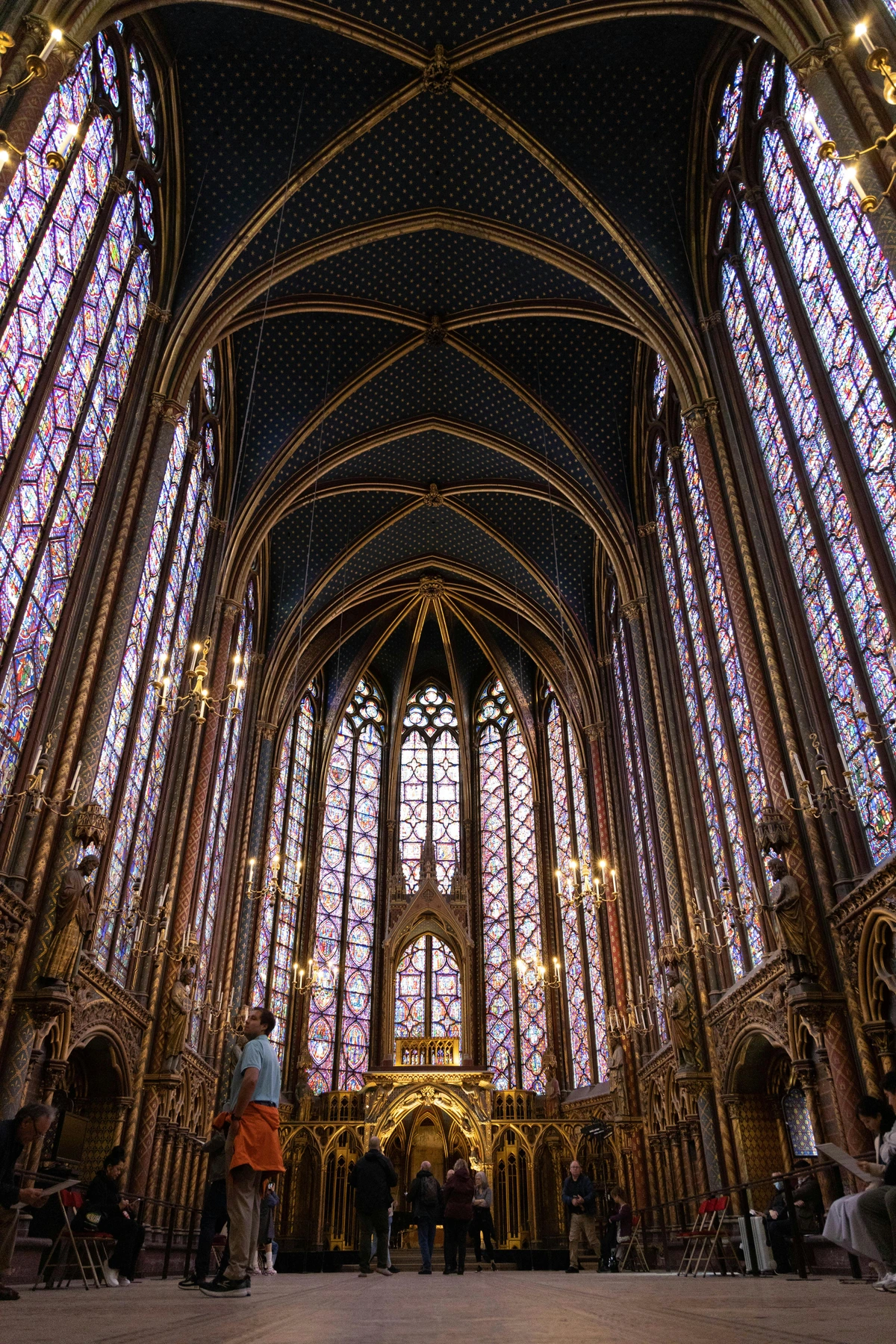

A revolution in architecture and light! The goal was height and luminosity, reaching towards the heavens. Innovations like the pointed arch, ribbed vault, and flying buttress allowed for thinner walls and enormous stained-glass windows that flooded the interiors with colored light (like stepping into a jewel box!). Sculpture became more elongated and gradually more naturalistic over time, often integrated into the architecture. The great Gothic cathedrals (Chartres, Notre Dame de Paris, Reims) are incredible achievements, embodying complex theology in stone and glass. They still take my breath away. Just imagine the sheer scale of human effort, faith, and ingenuity required to lift those stones and create those soaring spaces, all for the glory of God. The development of stained glass as a major art form is a key material innovation here, transforming light itself into a sacred element.

- Characteristics: Pointed arches, ribbed vaults, flying buttresses, stained glass windows, soaring height, elongated sculpture.

- Focus: Religion, salvation, biblical narratives, the power of the Church, divine light.

- Why it matters today: Medieval art shows the incredible power of shared faith to inspire monumental creative efforts. It also highlights how art can function as a primary means of communication and education. And Gothic cathedrals? Pure awe-inspiring engineering and artistic vision. The way light is used in these spaces still feels incredibly modern and impactful.

The Renaissance (c. 1400 – 1600): Rebirth, Humanism, and the Rise of the Artist

Ah, the Renaissance! The name means "rebirth," and it truly felt like one, starting in Italy. There was a passionate renewed interest in classical antiquity (Greek and Roman art and philosophy), a focus on humanism (the potential and achievements of humanity), and a surge in scientific inquiry that directly impacted art. Patronage shifted, with wealthy families (like the Medici), city-states, and the Church all commissioning work, often competing for the best artists. This era also saw the artist's status begin to rise significantly.

Early Renaissance (Florence, c. 1400s)

This is where the magic really starts happening. Artists figure out linear perspective – a mathematical system to create convincing illusions of depth on a flat surface (thanks, Brunelleschi and Alberti!). It's like unlocking a cheat code for realism, making the flat surface feel like a window into another world. There's intense study of anatomy, leading to more naturalistic figures. Artists like Masaccio revolutionized fresco painting (applying pigment to wet plaster before it dries, requiring speed and precision), Donatello brought sculpture back to life (his David is a game-changer, showing contrapposto again!), and Botticelli gave us ethereal beauty (Birth of Venus, often painted in tempera, a fast-drying, egg-based paint). The increasing use of oil paint, particularly in the North, allowed for richer colors, smoother blending, and finer detail than tempera, fundamentally changing painting possibilities.

- Characteristics: Linear perspective, anatomical accuracy, naturalism, revival of classical forms, fresco, tempera, early oil paint.

- Focus: Humanism, classical ideals, scientific observation, realism.

High Renaissance (Rome/Florence/Venice, c. 1490-1527)

The peak of classical ideals – harmony, balance, idealized beauty, emotional restraint (mostly!). This is the era of the titans, artists considered among the top artists ever: Leonardo da Vinci (Mona Lisa, Last Supper – minds still reel at his genius, experimenting with materials like fresco and oil), Michelangelo (the power of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the perfection of the David sculpture – mastering fresco and marble), and Raphael (the clarity and grace of School of Athens – a master of fresco). It's an era that set a standard that artists would react to for centuries. The artist is now seen as an intellectual, a genius, not just a skilled laborer.

- Characteristics: Harmony, balance, idealized forms, emotional restraint, monumental scale.

- Focus: Perfection of classical ideals, human potential, artistic genius.

Northern Renaissance (Flanders, Germany)

Developing alongside the Italian Renaissance but with its own distinct flavor. They shared the interest in realism but achieved it through incredible mastery of oil painting (allowing for rich colors and fine detail, layering glazes) and a fascination with the everyday world and complex symbolism. They were particularly obsessed with rendering texture and surface detail – the way light hits velvet, the gleam of a jewel, the subtle variations in skin tone – with breathtaking realism. Artists like Jan van Eyck, Albrecht Dürer, Hieronymus Bosch (the weirdest and best!), and Pieter Bruegel the Elder created worlds of stunning detail and often hidden meaning on wood panels and canvas. Their focus on detail and everyday life offers a different, equally fascinating window into the era.

- Characteristics: Mastery of oil paint, intense detail, focus on everyday life, complex symbolism.

- Focus: Realism, religious devotion, moralizing themes, portraiture.

Mannerism (c. 1520-1600)

A reaction against the perceived perfection and harmony of the High Renaissance. Mannerist artists got a bit... extra. Think artificiality, elongated limbs (limbs that go on forever!), complex, twisting poses, unusual, sometimes jarring colors (colors that clash just because!), and heightened emotional intensity. It's art that feels self-aware and stylish, almost like the art world's awkward teenage phase. Artists like Pontormo, Bronzino, Parmigianino, and El Greco (in Spain) pushed boundaries in fascinating ways, often using oil paint to achieve their effects. It's a style that prioritizes the artist's invention and skill over naturalistic representation.

- Characteristics: Artificiality, elongated forms, complex poses, unusual colors, heightened emotion.

- Focus: Artistic invention, style over substance, reaction against High Renaissance ideals.

- Why it matters today: The Renaissance gave us concepts like perspective and anatomical accuracy that became fundamental to Western art education. It's also the period where the artist's status began to shift from skilled craftsperson to intellectual genius. The innovations in materials like oil paint continue to influence painting today.

Baroque and Rococo (c. 1600 – 1780): Drama, Delight, and Dynamic Power

These styles are all about impact, reflecting the religious and political shifts of the time – the Catholic Counter-Reformation, powerful monarchies, and later, the refined tastes of the aristocracy. Patronage came heavily from the Church (especially in Catholic countries) and royal courts, but also a rising merchant class in places like the Dutch Republic. This led to a wider range of subjects and a more diverse art market.

Baroque (c. 1600-1750)

Drama! Emotion! Movement! Grandeur! This style grabs you by the collar. It's characterized by strong diagonals, intense contrasts between light and dark (chiaroscuro, and the even more dramatic tenebrism used by Caravaggio – think figures emerging dramatically from deep shadow, lit by an unseen, powerful source!), and theatricality. It feels dynamic and powerful, designed to evoke strong emotions and awe. Materials included oil paint, marble, bronze, and stucco, often used together in elaborate architectural settings.

- Italy: Caravaggio with his gritty, dramatic realism and intense light; Bernini whose sculptures and architecture (Ecstasy of Saint Teresa) are pure, ecstatic theater.

- Flanders: Peter Paul Rubens – energy, swirling forms, and incredibly rich color.

- Dutch Republic: A different vibe here – a focus on everyday life, portraits, and landscapes for a burgeoning merchant class. Patronage came from private citizens, leading to popular subjects like still life, genre scenes (depicting daily life), and landscapes. Rembrandt with his profound psychological portraits and biblical scenes; Vermeer with his intimate genre scenes and unparalleled depiction of light. Both masters of oil paint, but with a focus on capturing the nuances of light and texture in a more subdued, domestic setting compared to the Italian Baroque grandeur.

- Spain: Velázquez, the court painter, master of realism and capturing the dignity of his subjects, using oil paint with incredible subtlety.

- Characteristics: Drama, emotion, dynamism, strong chiaroscuro/tenebrism, theatricality, grandeur.

- Focus: Religious fervor (Counter-Reformation), monarchical power, emotional impact, everyday life (Dutch Republic).

Rococo (c. 1720-1780)

Primarily a French style, associated with the aristocracy and their elegant salons. It's like Baroque's playful, lighter, more decorative cousin. Think pastel colors, delicate, swirling S-curves and C-curves, and ornate, asymmetrical details. Common motifs include shells, flowers, and chubby little cherubs (putti). Themes often revolve around love, leisure, and lighthearted mythology. Artists like Watteau, Boucher, and Fragonard created worlds of charm and fantasy, often using oil paint on smaller canvases or for decorative panels. Patronage was almost exclusively aristocratic, reflecting a focus on pleasure and luxury.

- Characteristics: Lightness, elegance, pastel colors, delicate curves, asymmetry, decorative motifs.

- Focus: Aristocratic leisure, pleasure, fantasy, decoration.

- Why it matters today: These periods show how art can be a powerful tool for emotional impact and social display. The dramatic lighting of Baroque art still influences photography and film. Rococo reminds us that art can also be purely about beauty, charm, and delight, a counterpoint to more serious themes.

The Age of Revolution & The 19th Century (c. 1760 – 1900): Upheaval and the Road to Modernism

This period is a whirlwind of social change, scientific discovery, and artistic upheaval. It's where the ground is laid for the radical experiments of Modern Art. Artists are grappling with a rapidly changing world, and patronage becomes more diverse, including public exhibitions, private collectors, and dealers, alongside traditional sources.

This is also the century where the invention of photography fundamentally changed things. Painters were no longer the primary tool for recording likeness or events, freeing them up to explore subjective experience, emotion, and abstraction in new ways. It was a technological leap that forced artists to redefine the purpose of painting.

Neoclassicism (c. 1760-1830)

A reaction against Rococo's frivolity, inspired by the rediscovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum and the ideals of the Enlightenment (reason, order, morality). It looked back to classical forms (Greek and Roman) for inspiration, emphasizing clarity, stability, patriotism, and civic virtue. Artists like Jacques-Louis David (Oath of the Horatii) and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres with his precise lines embodied these ideals, often using oil paint with smooth, polished finishes, almost hiding the hand of the artist.

- Characteristics: Clarity, order, balance, classical forms, smooth finish, moral themes.

- Focus: Reason, civic virtue, patriotism, classical revival.

Romanticism (c. 1800-1850)

A powerful counter-movement to Neoclassicism's rationality. Romanticism championed emotion, individualism, imagination, the awe-inspiring power and beauty of nature (the Sublime!), exoticism, and a longing for the past. It's dramatic, passionate, and often turbulent. Think of the fascination with the exotic or the sublime in nature – the feeling of being overwhelmed by a storm at sea in a Turner painting, or the quiet, spiritual solitude of a figure contemplating a misty landscape in a Friedrich. Artists include Théodore Géricault (Raft of the Medusa – pure drama!), Eugène Delacroix (Liberty Leading the People), and landscape painters like J.M.W. Turner (capturing atmospheric light and weather with loose brushwork) and John Constable (celebrating the English countryside). Caspar David Friedrich gave us moody, introspective landscapes. Oil paint was the primary medium, often applied with visible brushstrokes to convey emotion and energy.

- Characteristics: Emotion, individualism, imagination, the Sublime in nature, dramatic subjects, visible brushwork.

- Focus: Feeling, intuition, nature, the exotic, the past.

Realism (c. 1840-1870)

A desire to depict the world as it is, without idealization or romantic drama. Realist artists focused on ordinary people, everyday life, and often tackled social or political issues head-on. It was considered quite radical at the time, often causing controversy by depicting subjects previously deemed too mundane or unpleasant for "high art"! Artists like Gustave Courbet (The Stone Breakers), Jean-François Millet (The Gleaners), and Honoré Daumier (known for his social satire) brought the unvarnished reality of modern life into art, typically using oil paint. They aimed for objective representation, though their choice of subject matter was inherently political.

- Characteristics: Depiction of everyday life, ordinary people, social commentary, objective representation.

- Focus: Reality, social issues, the present moment.

Impressionism (c. 1870s-1880s)

This is where things really start to shift towards the modern era. The Impressionists were fascinated by capturing the fleeting impression of a moment, especially the effects of light and color. They used visible brushstrokes, often painted outdoors (en plein air), and depicted modern urban life, landscapes, and leisure activities. Think Claude Monet (light on water, haystacks, cathedrals), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (figures in dappled light), Edgar Degas (dancers, racehorses), Camille Pissarro, and **Berthe Morisot. The development of pre-packaged paint tubes and portable easels made painting outdoors much easier – a material innovation with a huge impact! Interestingly, they were also influenced by Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e), which offered new perspectives on composition, cropping, and flat areas of color, showing how global art traditions were starting to intersect.

![]()

- Characteristics: Visible brushstrokes, focus on light and color, en plein air painting, modern subjects, influence of Japanese prints.

- Focus: Capturing fleeting moments, perception, modern life.

Post-Impressionism (c. 1880s-1900s)

Not a single unified style, but a group of diverse artists who built upon Impressionism's use of color and brushwork but sought different goals. They wanted more structure, more emotional expression, more symbolism. This group includes giants like Paul Cézanne (seeking underlying geometric structure, a precursor to Cubism), Vincent van Gogh (intense emotion and color – see his Starry Night! Looking at Starry Night always feels like witnessing the night sky having a nervous breakdown, but in the most beautiful, swirling, empathetic way.), Paul Gauguin (symbolism, flat forms, exotic subjects, influenced by non-Western art), and Georges Seurat (link) who developed Pointillism (using tiny dots of color to build form, based on color theory). These artists are foundational to everything that comes next, pushing the boundaries of oil paint and color theory.

![]()

- Characteristics: Diverse styles building on Impressionism, emphasis on structure, emotion, symbolism, color theory.

- Focus: Subjective experience, formal experimentation, symbolic meaning.

- Why it matters today: The 19th century is the bridge to modern art. It's where artists really start questioning traditional ways of seeing and painting, leading to the explosion of styles in the 20th century. Impressionism, in particular, remains hugely popular and accessible, and the Post-Impressionists laid the groundwork for abstraction and expressionism.

Modern Art (c. 1900 – 1970): The Great Experiment and Global Influences

Okay, buckle up. Modern Art is where tradition gets thrown out the window (or at least seriously questioned). It's a period of radical experimentation, driven by countless avant-garde movements challenging traditional representation, perspective, and subject matter. It's exciting, sometimes confusing (and it's okay if it feels confusing at first!), and incredibly fertile ground for new ideas. (Want to dive deeper? Check out my Guide to Modern Artists and Understanding Modern Art).

This is where the evolution of materials and techniques really accelerates, too. The invention of photography in the 19th century freed painters from the need to simply record reality, pushing them towards abstraction and subjective experience. New synthetic pigments expanded the available color palette. Later, industrial materials and techniques would become part of the artistic vocabulary. Patronage diversified further, with independent galleries, collectors, and eventually, modern museums playing key roles. This era also saw a significant increase in the influence of non-Western art traditions on Western artists, as seen in the impact of African sculpture on Cubism or Japanese prints on Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

Modern Art is generally considered to run from the late 19th century up to around the 1970s. It's distinct from Contemporary Art primarily by its timeframe, though the lines can be blurry. Think of Modern Art as the revolutionary period that broke from the past, and Contemporary Art as everything that's happened since, building on those breaks.

- Key Movements (A whirlwind tour!):

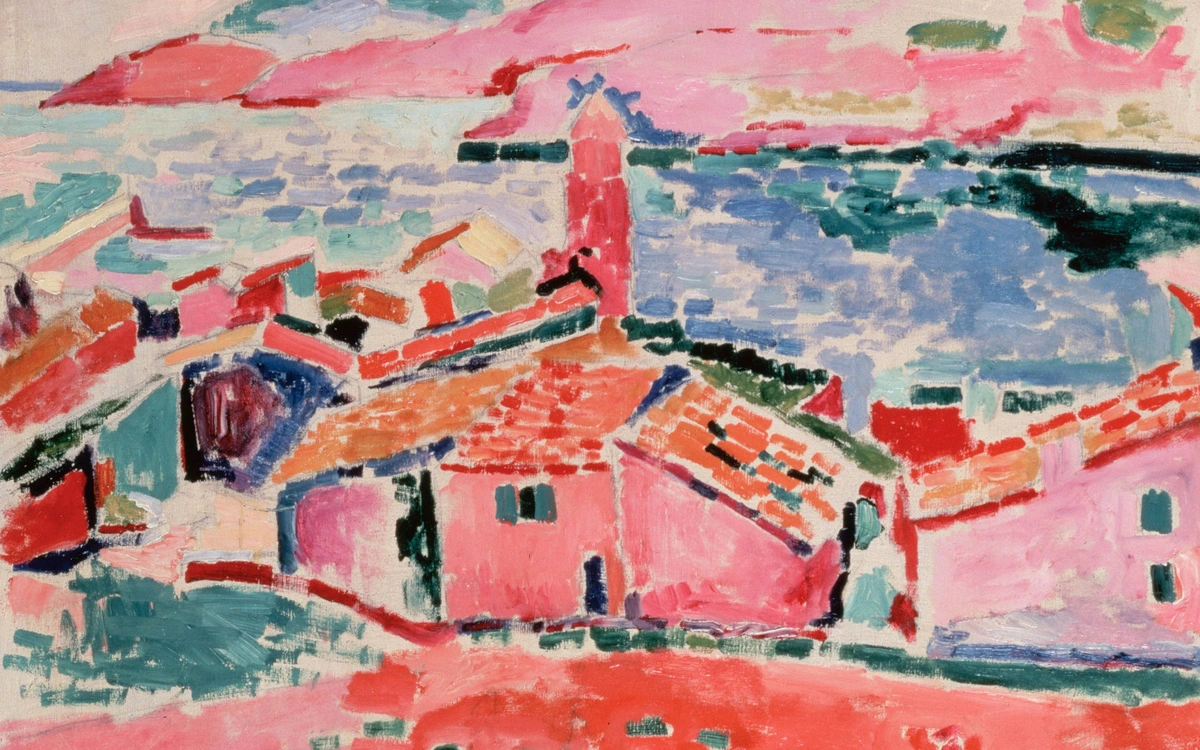

- Fauvism (c. 1905): "Wild Beasts"! All about bold, non-naturalistic color used for emotional effect. Think Matisse (link) and his vibrant, joyful canvases, often using oil paint with expressive brushwork. Color becomes an independent element, not just descriptive.

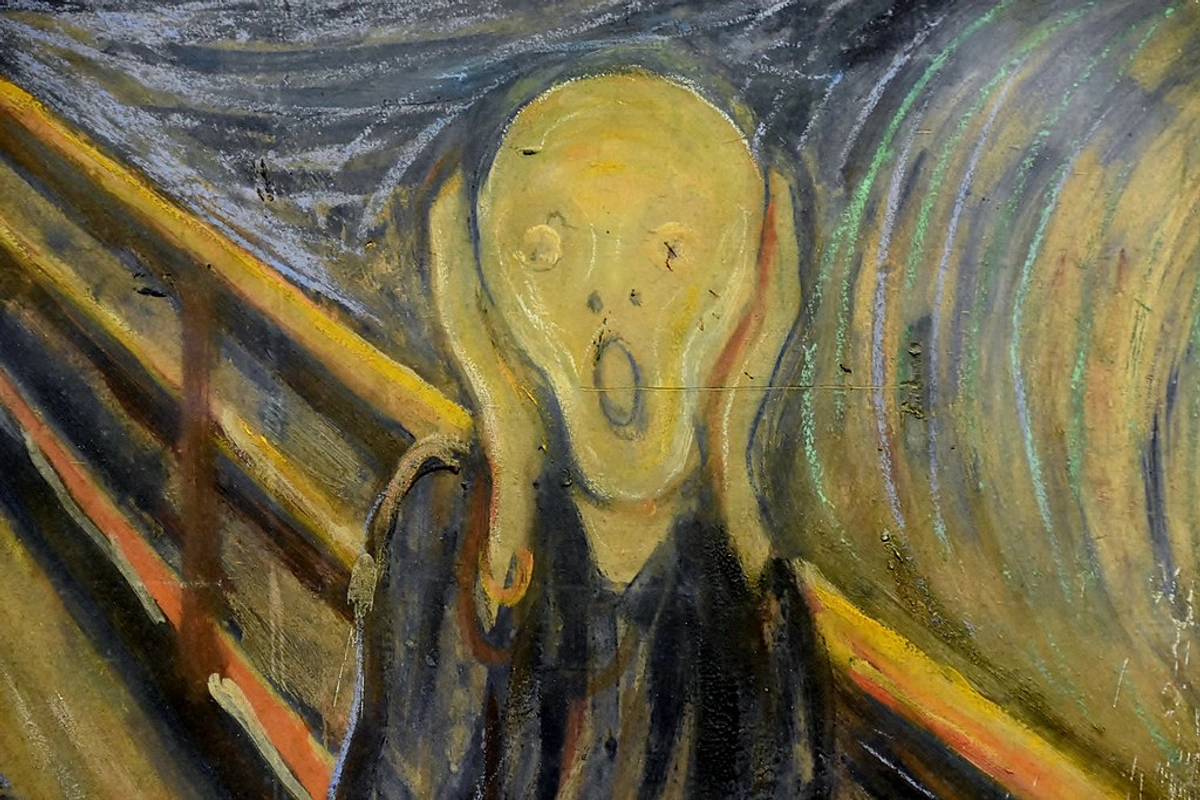

- Expressionism (c. 1905-20s): Focused on subjective emotion and inner experience over objective reality. Often intense, distorted, and psychological. Munch (The Scream!), Kirchner, Kandinsky (link). Artists used bold colors and distorted forms to convey feeling, working in paint, printmaking, and sculpture. It's about expressing the artist's inner state.

- Cubism (c. 1907): Shattering reality! Breaking objects down into geometric forms and showing them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. Revolutionary! Picasso (link), Braque. They experimented with collage, incorporating materials like newspaper and wallpaper into their paintings, blurring the lines between painting and sculpture. Cubism was also significantly influenced by African sculpture, which offered new ways of representing form and perspective, demonstrating another crucial intersection of global art histories.

- Futurism (c. 1909): Celebrating dynamism, speed, technology, cars, planes, the city! Often aggressive and nationalistic (yikes). Boccioni. They used fragmented forms and dynamic lines to convey movement, working in painting, sculpture, and even performance. It was about embracing the future and rejecting the past.

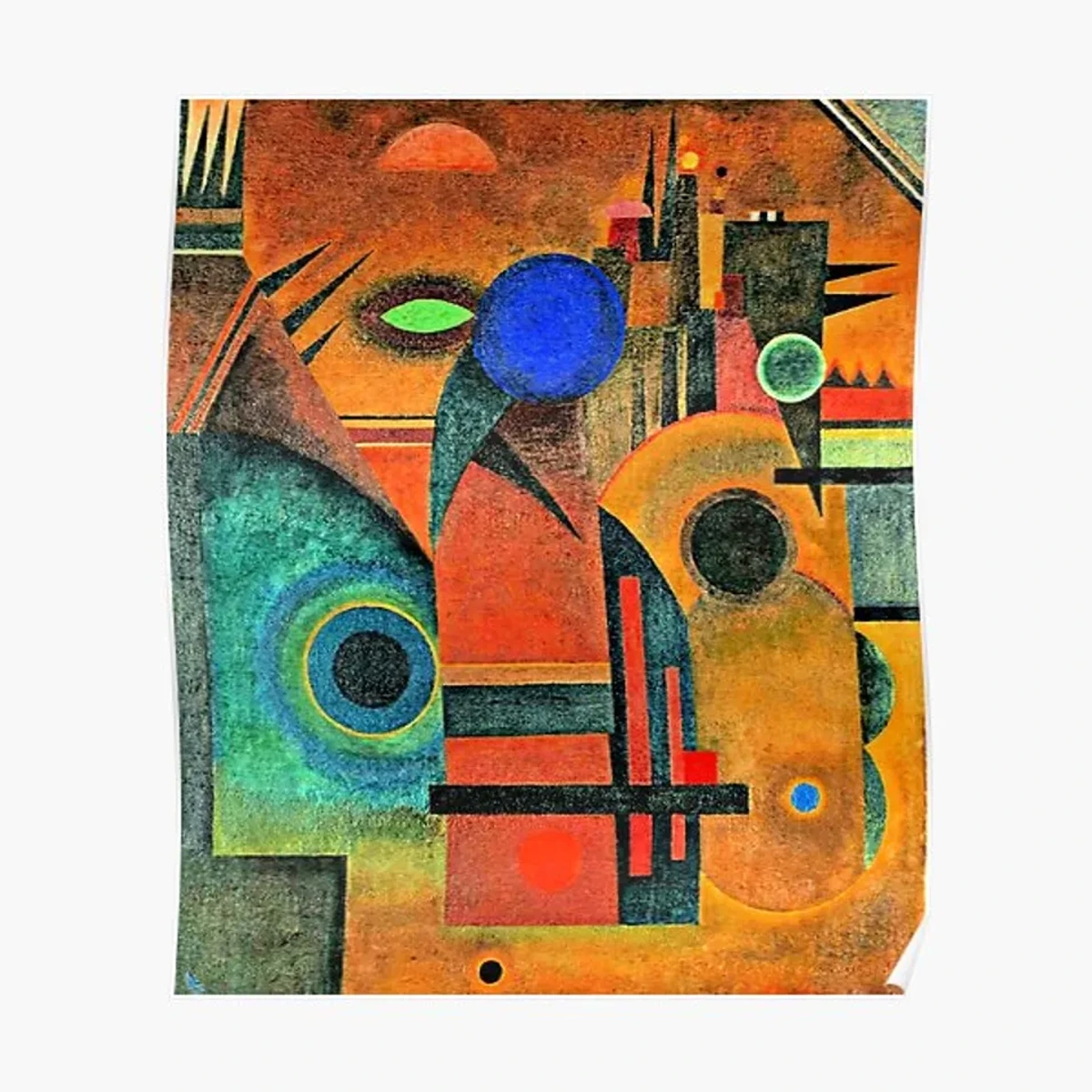

- Abstraction (c. 1910s onwards): Art that doesn't represent external reality. Explores form, color, line, and composition for their own sake. A huge, diverse field! There's a vast variety within abstraction, from the geometric purity of Mondrian to the gestural energy of Abstract Expressionism. Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian (link). This is a lineage that directly impacts my own work – understanding these pioneers is key to understanding why abstract art is so compelling today (link). Early abstract artists experimented with pure color and form, often influenced by music or spiritual ideas, seeking a universal visual language.

- Dada (c. 1916): Born out of the absurdity of WWI. Anti-art, anti-logic, embracing chance and nonsense. A rebellious, playful, and critical movement. Duchamp (hello, urinal!). They used readymades (everyday objects presented as art), collage, and performance to challenge traditional notions of art and authorship. It questioned the very definition of art.

- Surrealism (c. 1924): Exploring the subconscious, dreams, irrationality, and the bizarre, influenced by Freud. Dalí (melting clocks!), Magritte (pipe that isn't a pipe), Miró. Surrealists worked in painting, sculpture, photography, film, and writing, using techniques like automatic drawing to tap into the unconscious. It sought to liberate creativity from rational control.

- Abstract Expressionism (c. 1940s): The first major American art movement, emerging after WWII. Focused on spontaneous gesture (Action Painting like Pollock) or large fields of color (Color Field painting like Rothko - link). Intense, emotional, often monumental. As an artist, I'm fascinated by the sheer physicality of Action Painting – the dance of the artist around the canvas – or the deep emotional resonance Rothko achieves with just color and scale. Artists used large canvases and new materials like acrylic paint alongside oil, emphasizing the process of creation and the artist's presence.

- Pop Art (c. 1950s): Turning to mass culture, advertising, and everyday objects for subject matter. Bold, graphic, often ironic. Warhol (soup cans, celebrities!), Lichtenstein (comics). Artists used commercial techniques like screen printing and materials like acrylic paint to mimic mass production. It blurred the lines between fine art and popular culture.

- Minimalism (c. 1960s): Stripping art down to its essential forms, often using industrial materials and geometric shapes. Rejecting expression and illusion. Judd. They used materials like metal, plastic, and fluorescent lights, focusing on the object's presence in space and the viewer's experience of it.

- Conceptual Art (c. 1960s): The idea is the art. The concept behind the work is more important than the finished object itself. LeWitt, Kosuth. This movement could use any material or no material at all, emphasizing text, instructions, or documentation. It shifted the focus from the aesthetic object to the intellectual process.

Modern art is a wild ride, a constant questioning of what art can be. It's where the seeds of so much contemporary practice were sown.

- Focus: Experimentation, challenging tradition, subjective experience, social commentary, exploring new materials and ideas, global influences.

- Why it matters today: Modern art fundamentally changed our understanding of what art is and can be. It opened the door for the incredible diversity we see today and continues to influence contemporary artists. The focus on concept, material, and subjective experience are still central to artmaking.

Contemporary Art (c. 1970 – Present): The Ever-Expanding Now

This is the art being made in our lifetime, from the latter half of the 20th century right up to this moment. It's characterized by incredible diversity, globalization, and a willingness to engage with new technologies and pressing social issues. The increasing interconnectedness of the world means the idea of a single "Western" art history is less and less relevant; art is being made and influenced across continents simultaneously. (Curious about who's making waves today? See my guide to the Best Contemporary Artists).

- Postmodernism: Emerging around the 1970s, it's often marked by a skepticism towards grand narratives, a playful use of irony, pastiche (mixing styles), and appropriation (using existing imagery – think Richard Prince). It questions authorship and originality, often using diverse media and referencing art history itself. It's like art history having a conversation with itself, sometimes with a wink.

- Diversity of Media: The boundaries have dissolved. Art isn't just painting and sculpture anymore. We see installation art (transforming spaces), performance art (using the body and action), video art, digital art, street art (link), and so much more. Artists use whatever medium best serves their idea, from traditional paint and canvas to cutting-edge technology and ephemeral materials. I've seen contemporary artists use everything from human hair and chocolate to live insects and blockchain technology – the material possibilities are virtually limitless, driven entirely by the concept.

- No Dominant Style: Unlike previous eras, there isn't one single look or movement that defines contemporary art. There's a vast range of coexisting art styles and approaches, often overlapping and influencing each other. This can feel overwhelming, but it's also incredibly freeing – there's something for everyone.

- Key Themes: Contemporary artists grapple with globalization, identity (gender, race, sexuality), politics, technology, environmentalism, social justice, and the complexities of modern life. Art is often a way to process and comment on the world around them, acting as a mirror or a catalyst for discussion.

- Notable Trends/Movements (Just a few examples!): Neo-Expressionism, Feminist Art, Street Art, the Young British Artists (YBAs), Digital Art, Relational Aesthetics (art focused on human interaction). The scene is constantly evolving, with many top living artists pushing boundaries and redefining what's possible. And yes, vibrant abstract art remains a significant and exciting part of this landscape – it's where I live and breathe as an artist! The exploration of color, form, and non-representational expression continues to evolve.

- Focus: Diversity, globalization, social and political issues, new technologies, questioning established norms, interdisciplinary approaches.

- Why it matters today: Contemporary art is our art. It reflects the world we live in, challenges us to think, and shows the endless possibilities of human creativity in the face of constant change. It's a dynamic, ongoing conversation that we are all a part of.

The Artist's Journey: Status, Materials, Patronage, and Preservation Across Time

One of the most fascinating threads running through art history is the evolution of the artist themselves. It's a journey that resonates deeply with me as someone making art today. Knowing this history makes me feel less alone in my studio; I'm part of a long, messy, brilliant lineage of people who just had to make things. This journey is intertwined with changes in materials, the sources of patronage, and even the efforts to preserve art for future generations.

In the Prehistoric and much of the Ancient world, artists were often anonymous craftspeople. Their skill was valued, but their individual identity wasn't the focus. Think of the builders of the pyramids or the painters of Lascaux – we know their work, but not their names. Art served a collective purpose, whether religious, political, or magical. Materials were limited to what was readily available from nature – earth pigments, stone, bone, clay.

During the Medieval period, artists were primarily seen as artisans working for the Church or nobility. They were part of guilds, highly skilled but still largely anonymous in the grand scheme. Their role was to serve God and illustrate scripture or glorify their patrons. Materials were precious and often controlled by patrons or guilds, like the expensive gold leaf used in mosaics and manuscripts or the complex process of creating stained glass.

The Renaissance marked a significant shift. Artists like Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael weren't just craftspeople; they were celebrated as intellectual geniuses, thinkers, and innovators. Vasari's Lives of the Artists cemented this idea of the artist as a singular, brilliant individual. Patronage became a relationship, sometimes fraught, between powerful figures and these rising stars. The mastery of materials like oil paint and techniques like perspective elevated their status and allowed for new forms of artistic expression.

The Baroque and Rococo periods saw artists working closely with powerful patrons – kings, popes, aristocrats. Court painters like Velázquez held high social standing. The Dutch Republic, with its burgeoning merchant class, offered a new kind of patronage and allowed artists like Rembrandt and Vermeer to develop independent careers, focusing on subjects appealing to private buyers. This period saw further refinement in the use of oil paint to achieve dramatic effects or subtle realism.

The 19th Century brought further changes. The rise of public exhibitions (like the Paris Salon) and independent dealers meant artists had new ways to reach an audience, sometimes bypassing traditional patronage altogether. The Impressionists, famously, showed their work outside the official Salon system. This era saw the artist as a keen observer of modern life, a social commentator, or a solitary genius exploring their inner world (think Van Gogh). New materials like pre-packaged paint tubes and the revolutionary impact of photography also changed artistic practice.

With Modern Art, the artist often became the avant-garde rebel, challenging societal norms and artistic conventions. Movements like Dada and Surrealism actively questioned the status of the art object and the artist's role. The idea behind the art became as important, or more important, than the skill of execution in movements like Conceptual Art. New materials, from industrial steel to found objects and synthetic pigments, expanded the possibilities and further blurred the lines between art and life.

In Contemporary Art, the artist's status is incredibly varied. Some are global superstars, others work locally or within specific communities. The role can be that of a social activist, a researcher, a technologist, a storyteller, or still, a painter or sculptor. The relationship with patronage is complex, involving collectors, galleries, museums, corporations, and public funding. The choice of materials is virtually limitless, driven by the artist's concept, incorporating everything from traditional media to digital code and ephemeral elements. The challenge of preserving this diverse range of materials for the future is a significant aspect of contemporary art history and conservation.

Understanding this evolution of the artist's role, the materials they used, who supported them, and the ongoing efforts to preserve their work adds a crucial human dimension to the timeline. It reminds us that art history isn't just about objects; it's about people – the people who made the art, the people who paid for it, the people who experienced it, and the people who work to ensure it survives.

How I (and You Can) Look at Art History: Tools for Seeing More

Art historians have developed some pretty useful tools over the years, and they're not just for academics. Thinking about these concepts can totally change how you experience art:

- Style Analysis: This is like learning the visual language of an era or artist. What are the typical forms, colors, compositions, and techniques? How do they use line, shape, texture? It helps you identify when and where something might have been made, and understand its visual DNA. When I look at a painting, I'm always trying to figure out the artist's 'hand' – how they applied the paint, the rhythm of their marks.

- Iconography/Iconology: This is about the meaning behind the images. What are the subjects? What symbols are used? What do those symbols mean in that specific culture and time? It's like being a detective, uncovering layers of meaning. Why is that saint holding that specific object? What does that flower symbolize in a Dutch still life? (link) This helps us understand the stories and beliefs embedded in the art.

- Contextual Analysis: Art doesn't exist in a vacuum. You have to look at the world around it. What was the social, political, economic, religious, and technological environment like when it was created? Who commissioned it? Who was the intended audience? Understanding the context unlocks so much. Knowing who paid for a Renaissance altarpiece tells you a lot about its likely message, just as knowing the political climate informs our understanding of protest art.

- Formalism: Sometimes, it's powerful to just focus on the visual elements themselves – the lines, colors, shapes, composition – independent of subject matter or context. How does the way it's made affect you? This is particularly relevant for abstract art. When I'm making my own work, I'm often thinking purely about how colors interact or how shapes balance. It's about the visual experience itself.

- Diverse Methodologies: Modern art history is thankfully moving beyond a single viewpoint. Perspectives from feminism, post-colonialism, queer theory, and more offer richer, more inclusive interpretations, challenging older narratives and bringing previously overlooked artists and artworks into the light. It's a reminder that history is always being re-examined, helping us see who was left out or misrepresented in older histories.

Using these tools, even informally, makes looking at art a much more active and rewarding experience. It's like having different lenses to view the past.

How to Keep Exploring Art History (My Personal Tips)

Ready to dive deeper? Awesome! Here's how I keep learning, and how you can too:

- Go See the Art! Seriously, there is no substitute for standing in front of a painting or sculpture. The scale, the texture, the color – it's a completely different experience than seeing it on a screen. Start local! Explore museums and galleries near you. Plan trips to major art cities with world-class museums and galleries. If you're ever near 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, come visit my museum! (link)

- Read What Sparks Your Interest: Don't feel like you have to start with a massive, intimidating survey book (unless you want to!). Find an artist, a period, or a movement that catches your eye and read specifically about that. Museum exhibition catalogues are often fantastic. Reputable art journals and magazines can keep you up-to-date on new discoveries and interpretations.

- Watch Documentaries: There are so many brilliant films and series about artists and art movements out there now. It's a great way to get a visual sense of the art and hear from experts.

- Take a Class (Even Online): Many universities, museums, and online platforms offer art history courses, from introductory surveys to deep dives into specific topics. Learning with others can be really motivating.

- Follow Your Curiosity: Don't feel pressured to learn everything at once. Find what genuinely excites you – maybe it's the drama of the Baroque, the colors of Impressionism, or the weirdness of Surrealism. Follow that thread! Tracing an individual artist's journey over their career (link) can also be incredibly illuminating and feel less overwhelming than tackling huge periods.

- Think About Materials: As an artist, I'm always fascinated by how things were made. Reading about the pigments used in ancient Egypt, the development of oil paint in the Renaissance, or the impact of synthetic materials in the 20th century adds another layer of appreciation. It makes you see the physical reality of the art.

- Follow Art on Social Media: Many museums, galleries, and art historians share daily doses of art history, highlighting specific artworks, artists, or historical facts. It's an easy way to keep art history popping up in your feed and sparking new interests.

It's a lifelong adventure, and there's always something new to discover.

Conclusion: The Unfolding Story of Human Creativity (And Where You Fit In)

The history of art is this immense, complex, and utterly captivating narrative. It's not a finished story; it's still unfolding, with contemporary artists adding new chapters every single day. From the primal marks left in ancient caves to the dynamic experiments of Modernism and the incredibly diverse expressions happening right now, art offers invaluable insights into who we are and who we've been. It provides profound aesthetic experiences that can move us, challenge us, and connect us across time and culture.

For me, understanding this history isn't just about knowing facts; it's about understanding the lineage of creativity that I'm a part of as an artist. It helps me see my own work, and the work of my contemporaries, within a much larger context. It's a reminder that every artist, in every era, is responding to their world and the art that came before them. It's a conversation across millennia, and we're all invited to join in. Whether you're a viewer, a collector, or a maker, you have a place in this ongoing story. Find your voice within it. And remember, the effort to preserve this history, through conservation and scholarship, is vital to keeping this conversation alive.

This guide is just a starting point, a personal invitation to begin your own journey of discovery through this rich tapestry. So go explore! Find what speaks to you. And remember, the history of art is ultimately the history of human imagination – a story we're all still writing, and perhaps, adding our own little mark to. And if you're looking to buy art, understanding its history can really inform your choices and help you find pieces that resonate with you. It's all connected!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- What are the main periods in Western art history? Okay, the big ones we usually talk about are: Prehistoric (those amazing early cave paintings!), Ancient (Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek, Roman – empires and gods!), Medieval (Early Christian/Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic – faith and cathedrals!), Renaissance (rebirth and humanism!), Baroque/Rococo (drama and decoration!), the 19th Century (Neoclassicism, Romanticism, Realism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism – a century of change!), Modern Art (all those wild movements like Cubism and Surrealism!), and Contemporary Art (the incredibly diverse art of today!).

- Who are considered the greatest artists in history? Oh, this is the fun, impossible question! "Greatest" is so subjective, right? But if we're talking about immense influence and mastery, names that always come up include Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, J.M.W. Turner, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp (he really made us think!), and Andy Warhol. But honestly, there are countless others who were revolutionary in their time and deserve recognition. My guide on the top artists ever dives into this a bit more!

- How does non-Western art fit into this history? That's such an important point! While this guide focuses on the Western timeline (because that's the framework I know best), art history is absolutely global. Rich and distinct artistic traditions developed independently and interdependently across Asia (think the incredible landscapes of China, the prints of Japan, the sculptures of India), Africa (ancient Nok, Benin bronzes), the Americas (Mesoamerican, Andean), Oceania, and the Islamic world. These histories are vital and often influenced Western art at key moments (like how Japanese prints impacted the Impressionists, or African sculpture influenced Cubism!). A truly comprehensive understanding means exploring these incredible traditions too.

- What is the difference between Modern and Contemporary Art? Good question, it can be confusing! The main difference is usually chronological. Modern Art generally covers the period from the late 19th century (say, the 1860s) up to around the 1970s. It's defined by a break from traditional representation and a focus on formal experimentation. Contemporary Art refers to art made from the 1970s to the present day. It's characterized by its incredible diversity, global reach, and engagement with current issues and technologies. Think of Contemporary Art as the art of our time, building on the foundations of Modern Art. (I've got guides on Modern Art and Best Contemporary Artists if you want more!).

- Why did art styles change so much over time? It's never just one thing! Styles change because of a complex mix of factors: evolving cultural values and beliefs (what was important to a society?), technological advancements (new materials like oil paint, the invention of photography, now digital tools!), social and political events (wars, revolutions, shifts in power), philosophical ideas, changes in patronage (who is paying for the art?), and, crucially, the innovations of individual artists who are reacting to, rebelling against, or building upon the styles that came before them. It's a constant conversation and evolution!

- Where can I see examples of art from different periods? The best place is always a museum! Large encyclopedic museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the Louvre (Paris), the British Museum (London), the Hermitage (St. Petersburg), and the National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.) have collections spanning many periods. But don't overlook smaller or specialized museums! My guide to the Top Museums Worldwide is a good place to start planning your visits.

- How can understanding art history help me appreciate art today? It gives you context! It helps you understand why contemporary artists are making the choices they are, recognize the historical threads they're pulling on, appreciate technical innovations, and decode complex themes. It trains your eye to look more closely and think more deeply. It's like learning the backstory of a great novel – it just makes the present story so much richer and more meaningful. It helps you see the connections between a cave painting and a digital installation, and that's pretty amazing. And if you're looking to buy art, understanding its history can really inform your choices and help you find pieces that resonate with you. It's all connected!

- How do art historians date artworks? Great question! Dating art is often like detective work, using several clues. They look at the style (does it fit the characteristics of a known period or artist?), the materials and techniques used (were these available at a certain time? For example, certain pigments or types of canvas weren't invented until specific dates), subject matter (does it depict a historical event or person from a known time?), provenance (the history of ownership, which can be traced through documents), and sometimes scientific analysis (like carbon dating for organic materials, or analyzing pigment composition). Often, it's a combination of these methods that helps pinpoint when an artwork was created.

- What's the difference between an art movement and an art style? Think of a movement as a group of artists who share a common philosophy, approach, and goals, often working together or influencing each other over a specific period (like Impressionism or Surrealism). A style refers to the visual characteristics of the artwork itself – the way it looks, the techniques used, the forms, colors, and composition (like the Gothic style or the Baroque style). A movement often creates a distinct style, but a style can also be broader, encompassing work by different artists or even across different movements that share visual similarities.

- How is art history preserved? Preservation is crucial! It happens through conservation (the physical care and restoration of artworks to prevent deterioration), documentation (cataloging, photographing, and researching artworks and their history), archiving (collecting and maintaining records related to artists, galleries, and movements), and housing art in museums and collections with controlled environments. Digital technologies are also playing a growing role in documentation and even virtual preservation. It's a constant, often challenging, effort by conservators, curators, and historians to ensure these pieces of human history survive.