Ultimate Guide to Fauvism: The Art Movement of Wild Color & Intense Emotion

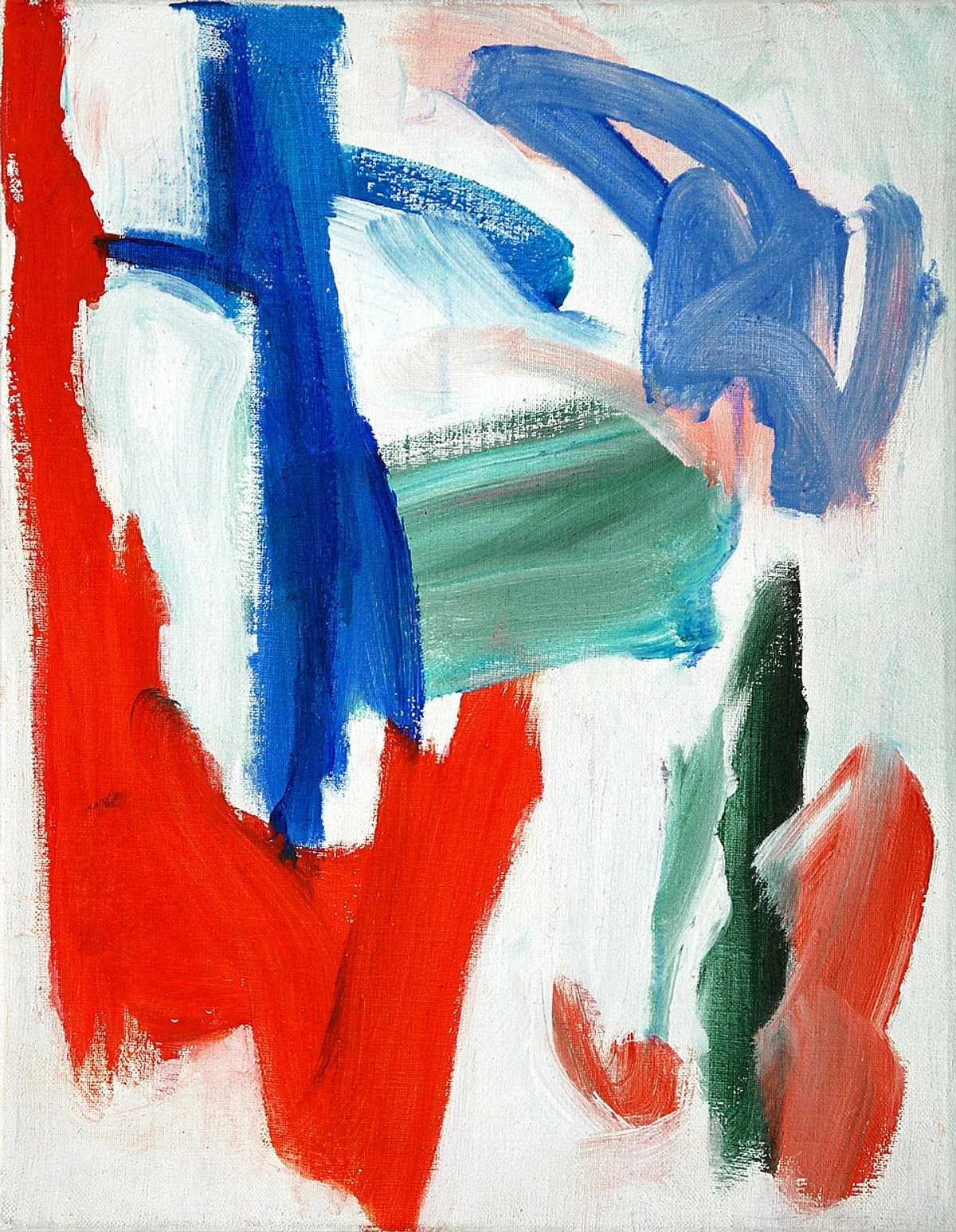

Step into the vibrant world of Fauvism! This ultimate guide, from an artist's perspective, explores the 'Wild Beasts,' their revolutionary use of intense color, key artists like Matisse & Derain, defining characteristics including bold outlines, its short but impactful history, and lasting influence on modern art and contemporary artists.

The Ultimate Guide to Fauvism: The Art Movement of Wild Color and Intense Emotion

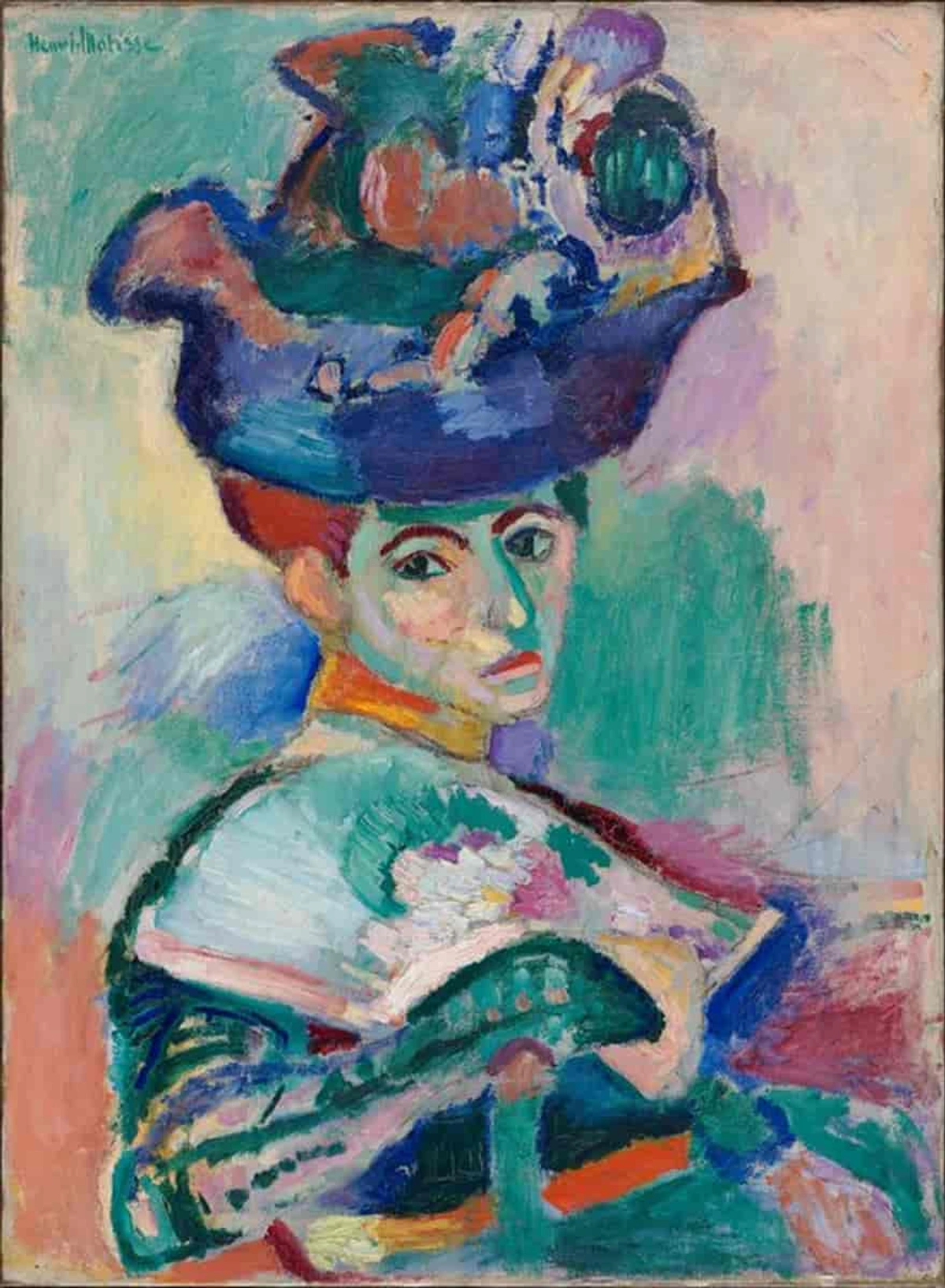

Have you ever looked at a painting and felt an immediate, visceral jolt of pure color? Like the artist just squeezed tubes of pigment directly onto the canvas, letting the hues sing (or maybe shout!)? That's the feeling Fauvism often evokes in me. I remember the first time I saw Matisse's Woman with a Hat in person – it wasn't just a painting; it was an experience. The sheer audacity of those colors, the green stripe down her nose! It felt like a direct challenge to everything I thought I knew about painting, and honestly, it was exhilarating. It's an art movement that didn't whisper; it roared onto the scene with a vibrant, shocking intensity in the swirling cauldron of early 20th-century Paris. Fauvism, though short-lived, fundamentally changed the course of Western art through its radical and joyous embrace of intense, non-naturalistic color and bold execution. It was the first major avant-garde movement of the new century, a crucial step in the development of Modern Art.

The name itself, derived from the French "Les Fauves" meaning "Wild Beasts," hints at the startled reaction it provoked. Coined by critic Louis Vauxcelles at the infamous 1905 Salon d'Automne exhibition, the term captured the raw, untamed energy and seemingly untutored application of color that characterized the style. It's easy to forget now, looking back, just how confrontational this art seemed. Imagine a public accustomed to the subtle nuances of Impressionism or the strict rules of academic painting being faced with Matisse's Woman with a Hat, where green stripes ran down the sitter's nose and patches of seemingly random color defined her face. Critics used words like "madness," "barbarism," and "a pot of paint flung in the face of the public." You can almost picture a stern, corseted Parisian lady clutching her pearls in horror! Honestly, sometimes I think that kind of pearl-clutching is the highest compliment you can pay truly revolutionary art. If it doesn't make someone a little uncomfortable, is it really pushing boundaries? The Fauves certainly weren't playing it safe.

This guide offers a comprehensive journey into the world of Fauvism. We'll explore its origins, delve into its defining characteristics, meet its key artists, examine influential artworks, understand its historical moment, and appreciate its lasting legacy.

Origins and Influences: Seeds of the Wild

Fauvism didn't emerge in a vacuum. It was born from a specific set of influences and reactions within the rapidly evolving art world of turn-of-the-century Paris:

- Reaction Against: The Fauves sought greater personal expression than they found in the optical realism of Impressionism or the systematic, almost scientific approach of Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism). They wanted art to be more direct, more emotive. We often see this pattern, don't we? One generation meticulously builds a system – like the Impressionists capturing light, or the Pointillists with their dots – and the next feels an urge to smash it, or at least shake it up considerably. It's less about rejection and more about needing room to breathe and shout in your own voice. It reminds me a bit of finding my own artistic path; you learn the rules, you study the masters, and then there's this undeniable pull to just... do it your way, to let your own internal landscape dictate the brushstrokes. The Fauves felt that pull with color.

- Key Influences: They looked back to Post-Impressionist masters who had already begun to liberate color and form:

- Vincent van Gogh: His highly emotional use of intense color and visible, energetic brushwork was a major inspiration. You can almost feel the direct line from Van Gogh's swirling skies and intense yellows to the Fauvist palette.

- Paul Gauguin: His use of flat planes of symbolic, non-naturalistic color and simplified forms pointed towards a more subjective approach.

- Paul Cézanne: While the Fauves were less concerned with structural rigor, Cézanne's emphasis on building form with color and challenging traditional perspective was influential.

- Gustave Moreau: As a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, Moreau taught Matisse and several other future Fauves, encouraging them to explore color and follow their individual instincts. Moreau was known for his Symbolist paintings and a less rigid, more imaginative teaching style than many of his academic contemporaries. He didn't just teach technique; he encouraged his students to look inward, to trust their feelings, and to see color not just as a descriptive tool but as a means of expression in itself. Imagine having a teacher who basically tells you to break the rules – what a catalyst! This kind of mentorship, focusing on personal vision over strict adherence to tradition, was clearly foundational for the Fauvist mindset.

- Influence of Japanese Prints (Ukiyo-e): Many artists in Paris at the time were captivated by Japanese woodblock prints. The Fauves, like others, were influenced by their flattened perspective, bold outlines, decorative patterns, and often non-naturalistic use of color. This exposure encouraged them to move away from traditional Western realism and embrace a more graphic, expressive approach to composition and color.

- Influence of Non-Western Art: While perhaps more directly impacting later Cubism, the growing exposure in Paris to African sculpture and other forms of non-Western art also contributed to the avant-garde's willingness to break from European academic traditions, particularly in the simplification and distortion of form. This broader trend towards looking beyond the Western canon for inspiration was part of the fertile ground from which Fauvism sprang. It's fascinating how artists are always absorbing influences from everywhere, isn't it? Like creative sponges, soaking up ideas from different cultures and times, then squeezing them out in entirely new ways.

- The Parisian Scene: Paris at the turn of the century was a hotbed of artistic activity. The official Salon system was losing its grip, and independent exhibitions and smaller galleries were gaining prominence. Alongside the Salon d'Automne, the Salon des Indépendants was another crucial venue for avant-garde artists, offering a space free from academic juries where they could exhibit their work directly to the public. Artists were exposed to a wider range of influences, including non-Western art and folk art, which encouraged a move away from academic realism. There was a palpable sense of wanting to break free from the past and forge a new visual language for a rapidly accelerating world.

Defining Characteristics: The Fauvist Style

What makes a painting recognizably Fauvist? Several key elements define the style:

- Intense, Arbitrary Color: This is the absolute hallmark of Fauvism. Color was freed from its traditional descriptive role (grass didn't have to be green, skies didn't have to be blue). Instead, artists used pure, often unmixed colors, sometimes straight from the tube, choosing hues for their emotional and expressive potential. Startling juxtapositions and vibrant contrasts were common, aiming for immediate visual impact.Think pure joy, shock, or heat translated directly into pigment. It wasn't about what the color was, but what it felt like. Imagine painting a sunny day not with realistic yellows and blues, but with fiery oranges, hot pinks, and electric greens because that's how the feeling of intense sunlight hits you. Understanding these art elements like color theory becomes crucial here, but the Fauves used it intuitively, emotionally. They weren't just painting with color; they were painting emotion as color. This radical approach to color is fundamental to How Artists Use Color.While the use of color was deeply personal and expressive, it also served a decorative purpose. The Fauves aimed to create visually harmonious (or intentionally dissonant) compositions where the interplay of colors created a beautiful or impactful surface, independent of realistic representation. It's a fascinating duality – color as raw emotion and color as a building block for a visually pleasing (or arresting) design.

- Bold, Expressive Brushwork: Paint was often applied in energetic, visible strokes. The texture of the paint and the dynamism of the application became part of the artwork's expressive force. Brushwork could be short and dabbed, or long and flowing, but rarely smooth and blended in a traditional manner. You can see the energy, the speed, the decision-making right there on the canvas. It's like seeing the artist's hand dancing across the surface. This use of visible brushwork built upon the techniques of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism but pushed them towards greater emotional intensity.

- Simplified Forms & Flattened Perspective: Realism was abandoned in favor of simplification and distortion. Details were often omitted, and traditional perspective was flattened, creating planes of color that emphasized the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Why bother with fussy details when the color itself carries the weight of the emotion? Forms were often reduced to their essential shapes. Think of it like looking at a scene and deciding which parts are most important to the feeling you want to convey, then stripping away everything else until you're left with just the core shapes and colors. It's less about creating a window into a realistic world and more about building a vibrant, self-contained world on the canvas surface.

- Strong, Often Contrasting Outlines: A noticeable feature in many Fauvist works is the use of bold lines, often in contrasting colors, to outline forms. This technique further emphasizes the simplified shapes and flattens the sense of space, contributing to the decorative quality of the painting and separating areas of intense color.

- Emotional Expression over Realism: The primary goal was to convey the artist's subjective feeling about the subject matter, rather than depicting it accurately. The decorative quality of the painting – its harmony or dissonance of color and form – was paramount. It's art that hits you in the gut before it engages your analytical brain. This focus on inner feeling connects Fauvism to the broader trend of Expressionism.

- Subject Matter: While the style was radical, the subjects were often quite traditional: landscapes (especially the sun-drenched south of France where Matisse and Derain worked together), portraits, still lifes, and interiors. It was the treatment of these subjects that was revolutionary. They painted the world around them, but painted it through their feelings.

Techniques and Materials: The Painter's Arsenal

How did they achieve this look? Part of it was attitude, sure, but materials played a role too. The increasing availability of pre-mixed paints in tubes was a game-changer. Unlike previous generations who often had to grind their own pigments (imagine the sheer effort!), the Fauves could grab tubes of brilliant, ready-to-use Cadmium Yellow, Cobalt Blue, or Vermilion Red and apply them directly, often without extensive mixing on the palette. This encouraged spontaneity and the use of pure, saturated hues. They often worked alla prima (wet-on-wet), applying paint in layers before the previous ones dried, which contributed to the energetic brushwork and vibrant color mixing directly on the canvas. Working alla prima means making decisions quickly, letting the colors blend and interact right there on the surface, which perfectly suited their spontaneous, expressive approach. Sometimes they even left areas of raw canvas exposed, letting the white ground contribute to the overall brightness and vibrancy, creating a stark contrast with the thick impasto (thickly applied paint) elsewhere. There was often little to no underpainting; the color explosion happened right there on the surface. It sounds a bit messy, doesn't it? Like a kid let loose with a box of crayons, but with incredible intention and feeling behind it.

The Key Fauves: Masters of Wild Color

While several artists were associated with the movement, three figures stand out, whose works would famously converge at the Salon d'Automne:

- Henri Matisse (1869-1954): Often seen as the central figure and intellectual leader. Matisse used color to create harmony, balance, and a sense of decorative pleasure, even amidst the intensity. His Fauvist works aimed for an "art of balance, of purity and serenity." (Matisse: Harmony and Joy). You can trace his journey on pages like an artist's timeline, seeing how Fauvism was a crucial, explosive phase in his lifelong quest for color's essence. He is undoubtedly one of the Top Artists Ever.

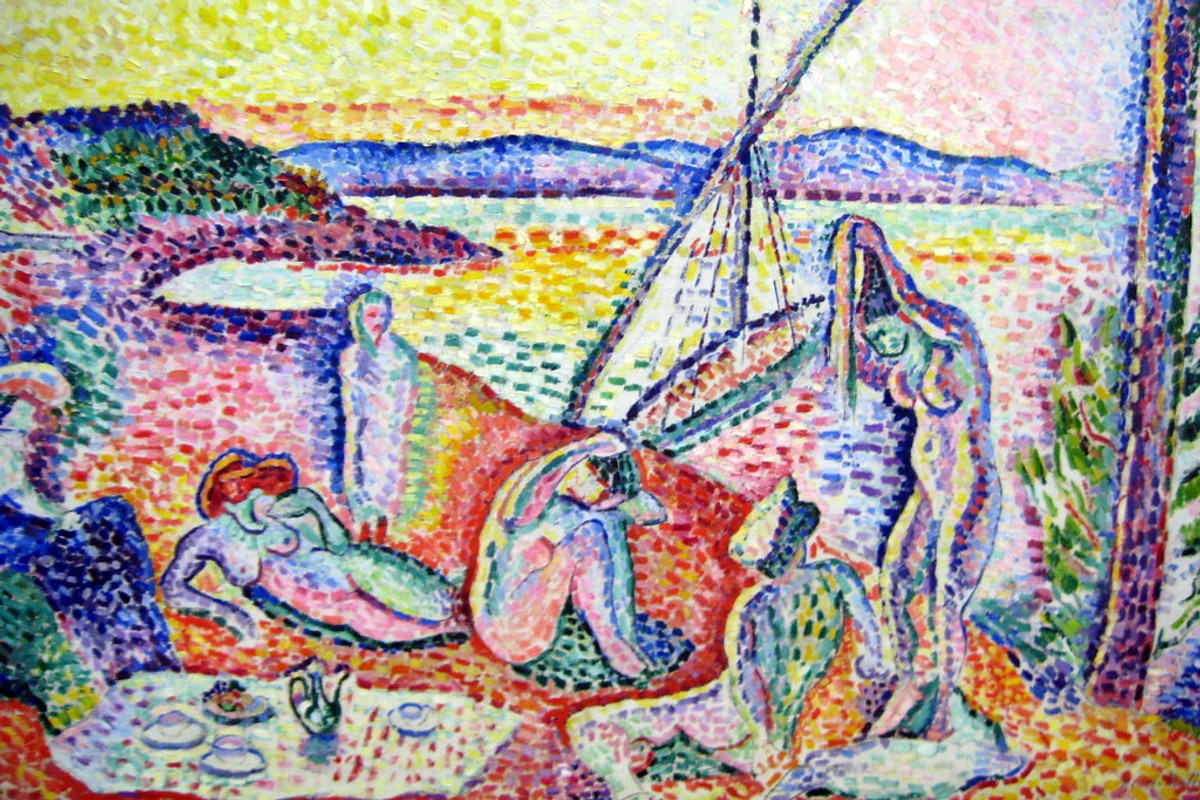

- Key Works: Woman with a Hat (1905), The Joy of Life (Le bonheur de vivre) (1905-06), Luxe, Calme et Volupté (1904 - a key transitional work showing Neo-Impressionist influence).

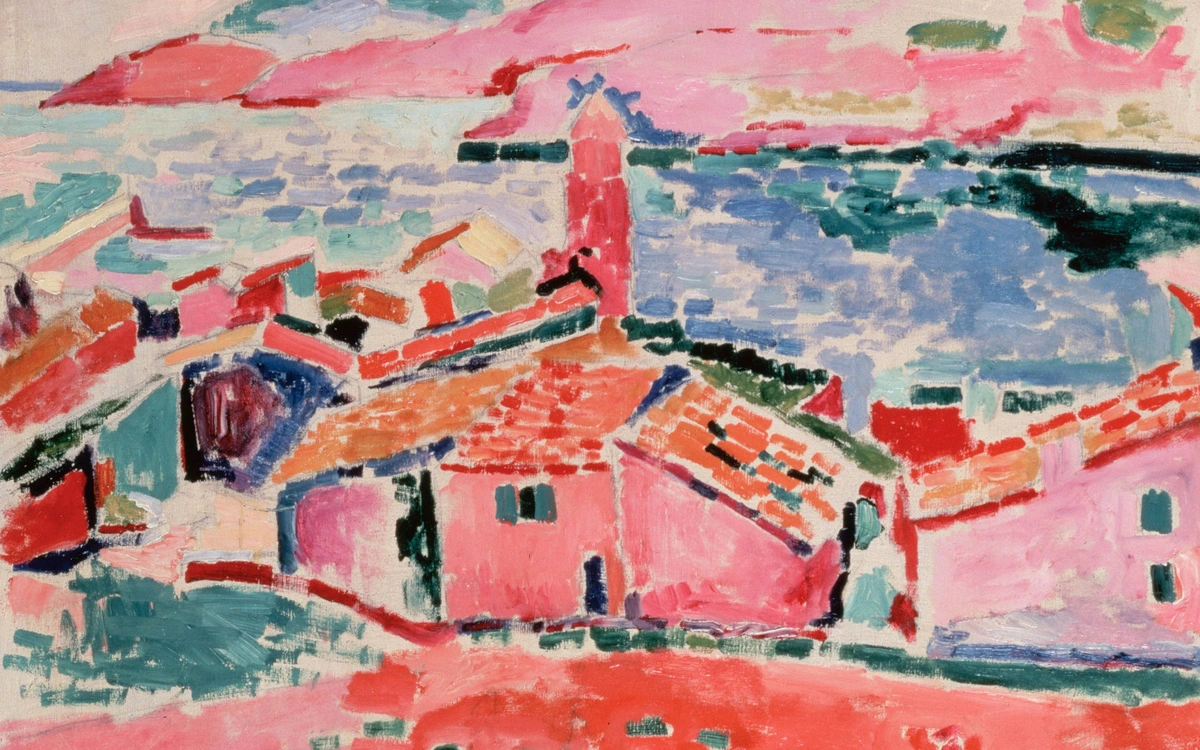

- André Derain (1880-1954): A close collaborator with Matisse, particularly during their summer working in Collioure in 1905. Derain's Fauvist works are known for their dazzling light and vibrant depictions of landscapes and cityscapes, using bold color patches and dynamic lines. His London series, in particular, transforms the often grey city into a riot of color. Derain once described color as "cartridges of dynamite" – a perfect, punchy analogy for the explosive effect the Fauves aimed for! (Derain: Dazzling Light and Energy).

- Key Works: Mountains at Collioure (1905), Charing Cross Bridge, London (1906), The Turning Road, L'Estaque (1906).

- Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958): Perhaps the most instinctive and fiery of the core Fauves. He famously declared he wanted to burn down the École des Beaux-Arts with his cobalts and vermilions. His work features thick paint application (impasto) and extremely bold, often clashing color contrasts, conveying raw energy. Less calculation, more pure painterly passion. (Vlaminck: Raw Passion and Impasto).

- Key Works: The River Seine at Chatou (1906), Restaurant de la Machine at Bougival (1905).

- Other Important Figures associated with Fauvism include Raoul Dufy (known for his light, airy, and decorative style), Georges Braque (who exhibited with them before co-founding Cubism with Picasso), Kees van Dongen (famous for his sensuous portraits with intense color), Albert Marquet (often depicted Parisian scenes and ports with a more subdued Fauvist palette), Jean Puy, Othon Friesz, and Henri Manguin. While maybe not as famous as the 'big three', their contributions helped define the breadth of the movement.

The 1905 Salon d'Automne: Birth of the "Wild Beasts"

The autumn of 1905 was Fauvism's dramatic public debut. Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, Marquet, Manguin, Puy, and others exhibited their radically colored canvases together in Room VII of the Salon d'Automne in Paris. Amidst these vibrant works stood a relatively traditional Renaissance-style sculpture by Albert Marque. On seeing this juxtaposition, the critic Louis Vauxcelles famously exclaimed, "Donatello au milieu des fauves!" ("Donatello among the wild beasts!"). The name stuck, initially used derisively but quickly adopted by the artists themselves.

Scandal and Support: The Reaction

The exhibition caused a scandal, shocking the public and conservative critics but also attracting the attention of adventurous collectors like Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo. The Steins, particularly Gertrude, were early champions of avant-garde art in Paris and provided crucial support and validation when the establishment was still reeling. This early patronage was vital for the artists' confidence and survival. It's a reminder that new art often needs brave patrons as much as it needs brave artists. The reaction wasn't universally negative, but the shock value was undeniable. Imagine walking into that room in 1905, expecting muted tones and careful brushwork, and instead being hit by a wall of screaming, clashing colors and raw energy. It must have felt like stepping into another dimension! It challenged everything people thought they knew about how painting should look. I can almost hear the gasps and indignant whispers echoing through the gallery – a symphony of disapproval that, in hindsight, sounds a lot like the fanfare for a revolution.

Key Fauvist Artworks: A Closer Look

To truly understand Fauvism, let's look at a few iconic examples and see how they embody the movement's principles:

- Woman with a Hat (Henri Matisse, 1905): This is the painting that arguably sparked the "Fauves" label. It's a portrait of Matisse's wife, Amélie, but instead of realistic skin tones, her face is a patchwork of green, yellow, and red. Her hat is a riot of clashing colors. The brushwork is loose and visible. The bold, non-naturalistic colors here aren't just random; they convey a sense of vibrant energy and the subjective experience of seeing her in that moment, perhaps even reflecting the lively atmosphere of the Salon itself. It's not about capturing a likeness in the traditional sense, but about conveying the feeling or impression of the sitter and the vibrant atmosphere of the Salon itself through pure, expressive color. It's a bold, almost defiant use of color that announced a new era.

- View of Collioure (Henri Matisse, 1905): Painted during the pivotal summer Matisse spent with Derain in the southern French town of Collioure. This landscape is a prime example of Fauvist color applied to a traditional subject. The sea isn't just blue; it's patches of pink, green, and purple. The trees are vibrant orange and red. The buildings are outlined in bold strokes. The perspective is simplified. The intense, almost glowing colors here capture the feeling of the bright Mediterranean sun and the sheer joy the artists felt painting in this location. It's a celebration of the intense Mediterranean light and the sheer joy of painting, translated into pure color.

- Charing Cross Bridge, London (André Derain, 1906): Part of Derain's series commissioned by Ambroise Vollard, depicting London scenes. Derain took the famously foggy, grey city and transformed it into a vibrant spectacle. The Thames is a brilliant blue, the sky is yellow and pink, and the bridge is a patchwork of bold colors. It's a perfect illustration of how the Fauves used color subjectively, imposing their emotional response onto the scene rather than depicting its optical reality. The unexpected, high-key palette makes the familiar London scene feel fresh, energetic, and full of life, conveying Derain's excitement about the bustling city. It makes you wonder what other cities would look like through Fauvist eyes. Maybe my own city, 's-Hertogenbosch? I can see the canals in vibrant blues and greens, the buildings in warm oranges and reds... a fun thought experiment! Or perhaps imagining a simple still life – a bowl of fruit where the apple is a shocking blue and the banana a fiery red, capturing the energy of the fruit rather than its exact appearance.

- The River Seine at Chatou (Maurice de Vlaminck, 1906): Vlaminck's work often feels more raw and less harmonious than Matisse's or Derain's. This landscape is characterized by thick impasto, bold, almost violent brushstrokes, and clashing color combinations – intense reds, blues, and yellows applied with visceral energy. The raw, unmixed colors and heavy texture convey a sense of untamed nature and raw emotion, embodying the "wild beast" spirit perhaps more literally than his colleagues. It feels less like an observation and more like an explosion of feeling onto the canvas.

- Woman with a Fan (Kees van Dongen, 1905): Van Dongen, known for his portraits, applied the Fauvist approach to figure painting with striking results. In Woman with a Fan, the sitter's face is rendered with bold, non-naturalistic colors – greens, reds, and blues – while her dress and the background are a riot of vibrant hues and patterns. The forms are simplified, and the brushwork is loose and energetic. The daring color choices and simplified forms create a portrait that is less about psychological depth and more about capturing a sense of vibrant presence, sensuality, and decorative flair through the sheer power of color. It shows how the Fauvist palette could be used to create sensuous and lively depictions of people, not just landscapes.

A Short-Lived Phenomenon (c. 1905-1908)

Despite its explosive impact, Fauvism as a unified movement was remarkably brief, essentially lasting only three years. There was no single manifesto, and the artists involved were primarily linked by their shared desire for expressive color rather than a rigid doctrine. It was more of a shared moment of discovery than a structured school. By 1908, the core artists began pursuing individual paths: Matisse developed his unique style focused on line, simplified form, and harmonious color; Derain moved towards a more structured, Cézanne-influenced style; Braque teamed up with Picasso to forge Cubism.

Why such a short lifespan? From the artists' perspective, it seems they felt they had rapidly and thoroughly explored the potential of pure, non-naturalistic color expression in this specific, intense way. The initial burst of energy and discovery was immense, but perhaps the style itself, with its focus almost solely on color and simplified form, didn't offer enough avenues for continued exploration for every artist. New ideas were also constantly bubbling up in Paris; the emergence of Cubism, with its radical approach to form and space, presented a fresh, compelling challenge that drew artists like Braque and, indirectly, influenced others. Like a supernova, it burned incredibly brightly but couldn't sustain that exact intensity indefinitely. It makes me think about how some creative bursts are intense but fleeting, while others evolve over a lifetime. Both are valid, I suppose, just different rhythms. Maybe they just got bored? Or maybe they realized that once you've been that wild, you need a new kind of challenge to keep things interesting. Who knows what goes on in the mind of a 'wild beast'?

Legacy and Influence: The Enduring Roar

Though short-lived, Fauvism's impact was profound and lasting. So why, over a century later, does Fauvism still feel relevant? Let's explore its enduring roar:

Liberation of Color

This is Fauvism's most crucial legacy. By demonstrating that color could be used arbitrarily and subjectively for purely expressive and decorative purposes, the Fauves broke centuries of tradition and opened up vast new possibilities for artists. They showed that color didn't just have to describe the world; it could be the world, or at least the emotional experience of it. It was a pivotal moment in the story of Modern Art. They basically gave color its freedom papers. This paved the way for countless artists who would explore color's abstract potential, directly influencing the development of pure color abstraction in later movements.

Influence on Expressionism (and Key Differences)

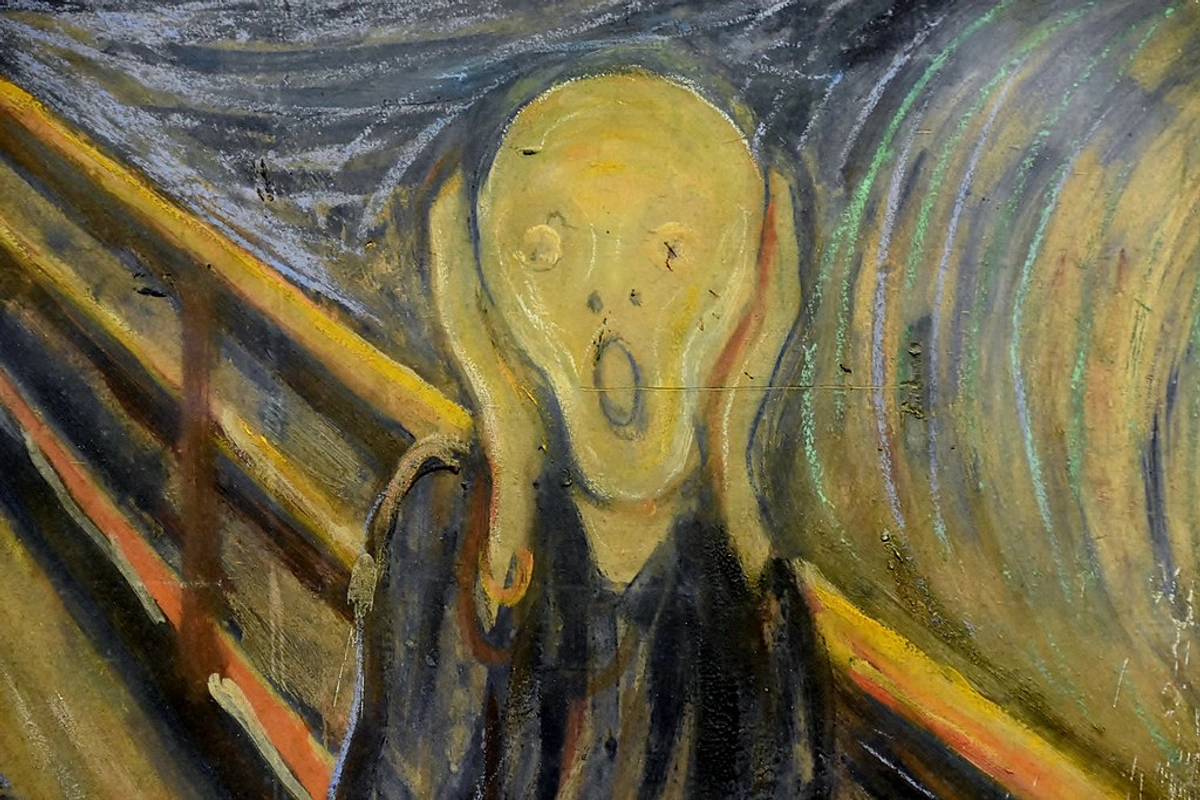

The Fauvist emphasis on intense color and emotional directness heavily influenced subsequent movements, most notably German Expressionism (groups like Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter). Fauvism can be seen as a direct precursor, showing artists that color and form could be distorted to convey inner states. Both movements embraced intense color and distorted forms to convey inner feelings rather than objective reality. However, their emotional tenor often differed. The Fauves, particularly Matisse and Derain, often focused on harmony, pleasure, and the sensuous beauty of the Mediterranean landscape or decorative interiors. Their wildness felt more joyous, a celebration of pure visual sensation. German Expressionists (like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, or Edvard Munch even earlier) frequently channeled more angst, psychological tension, and social critique. Their colors could be jarring and dissonant, reflecting the anxieties of modern urban life or deeper spiritual turmoil. Think of the difference between a sun-drenched Derain landscape and the sharp, edgy energy of a Kirchner street scene, or the raw anguish in Munch's The Scream. Both used color emotionally, but the emotions themselves often came from different places. It's like two people shouting, but one is shouting with joy and the other with pain.

Here's a quick comparison:

Feature | Fauvism | German Expressionism |

|---|---|---|

| Color Use | Intense, arbitrary, often harmonious | Intense, arbitrary, often dissonant/jarring |

| Emotional Tone | Joy, pleasure, sensuality, visual delight | Angst, psychological tension, social critique |

| Subject Focus | Landscapes, portraits, still lifes, interiors | Urban life, psychological states, social issues |

| Goal | Express subjective feeling, decorative effect | Express inner turmoil, social commentary |

Matisse's Foundation

For Henri Matisse, Fauvism laid the groundwork for his lifelong exploration of color as the primary means of expression, solidifying his place as one of the most significant artists in history. His later work, while evolving, retained that fundamental belief in color's power.

Contemporary Resonance & Personal Connection

The Fauvist spirit – the bold, intuitive, joyous use of color – continues to resonate. Many contemporary artists exploring color and abstraction owe a debt to the breakthroughs of Les Fauves. This liberation of color is fundamental to much of the vibrant, colorful contemporary art available today. Their revolutionary approach remains a potent source of art inspirations.

Beyond Expressionism, the Fauves' fearless use of color echoed in later movements like Orphism (Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay), which focused on pure abstraction through color and form. Even today, you can see the Fauvist legacy in artists who prioritize color's emotional impact and decorative power. Think of contemporary painters who use saturated, non-naturalistic palettes to evoke mood or build form, or even street artists whose vibrant murals transform urban spaces with pure, uninhibited color. It's a direct lineage from those "wild beasts" in Paris.

For me, it’s that unapologetic embrace of feeling through color. In a world that can sometimes feel overly complex, cynical, or just plain grey, there’s something incredibly refreshing about the Fauvist belief in the direct emotional power of pure pigment. It reminds us that art doesn’t always have to be about deep intellectual concepts or painstaking realism (though those have their place too!). Sometimes, it can just be about the unadulterated pleasure in looking – of experiencing yellow that feels like sunshine, blue that feels like deep water, red that feels like heat or passion.

This idea that color can directly communicate emotion is, I think, fundamental to why abstract art can be so compelling. It taps into something primal. When I'm working in my studio, trying to capture a feeling or an idea, playing with color is often the most direct route. Sometimes you just need that blast of orange or that calming field of blue to say what words can't. The Fauves were pioneers in trusting that instinct, in letting the 'wild beasts' of color lead the way. Their legacy isn't just in museums; it's in every designer who uses a bold color palette, every artist who lets emotion dictate their hues, and maybe even in that bright scarf or vibrant print you choose to liven up your day. It’s a reminder that sometimes, being a little bit 'wild' with color is exactly what we need. You can see echoes of this joy in color in much of the contemporary art for sale today.

Experiencing Fauvism: Where to See the Art

To truly grasp the impact of Fauvist color and energy, seeing the works in person is essential. Major collections can be found in:

- Key Museums:

- Centre Pompidou, Paris

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

- The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- Tate Modern, London

- Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

- Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

- Musée d'Orsay, Paris (for Post-Impressionist influences)

- Find these and others in lists of the best museums for modern art and top museums worldwide.

- Tips for Appreciation:

- Let the Color Wash Over You: Don't immediately try to interpret what is depicted. Focus on how the colors make you feel. Do they make you feel energetic, calm, uneasy? The Fauves wanted a direct emotional response.

- Observe Color Interactions: Notice how adjacent colors vibrate or contrast. How does Matisse create harmony compared to Vlaminck's clashing tones? See how colors are used to model form or flatten space.

- Appreciate the Brushwork: Look at the texture and direction of the strokes. How do they contribute to the painting's energy and the artist's hand? You can often see the speed and spontaneity of the application, almost feeling the artist's presence. This visible hand is a key part of the expressive power.

- Embrace Simplicity: Note the simplification of forms and flattening of space. How does this enhance the impact of color? Pay attention to how the simplified composition and flattened perspective work with the bold color to create the overall visual effect, rather than trying to create a realistic illusion. Adapt skills from how to read a painting to focus on these elements.

- Remember the Context: Imagine seeing these paintings in 1905 – understand their radical nature at the time. They were a shock to the system! It helps to appreciate just how brave these artists were.

Conclusion: A Brief Blaze, A Lasting Light

Fauvism was more than just bright colors; it was a declaration of artistic freedom. In a brief but brilliant blaze of creativity, Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and their colleagues unleashed color from its descriptive chains, prioritizing raw emotion and decorative power. Though the movement itself was short-lived, its revolutionary spirit echoed through the 20th century and continues to inspire artists who believe in the profound expressive potential of pure color. Fauvism remains a vital and joyous chapter in the ongoing story of art, a reminder that sometimes, the wildest ideas are the ones that truly set things free. For me, the Fauves are a constant reminder to trust my instincts, to be bold with my palette, and to always let the emotion lead the brush. Their wildness wasn't chaos; it was a deliberate, joyful rebellion that still makes my heart sing with color.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- What does "Fauvism" mean? It comes from the French phrase "Les Fauves," meaning "The Wild Beasts." This name was given by a critic in response to the perceived wildness and non-naturalistic intensity of the colors used by the artists at the 1905 Salon d'Automne.

- Who were the main Fauvist artists? The core figures generally considered the leaders are Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck. Others associated include Raoul Dufy, Georges Braque, Kees van Dongen, and Albert Marquet.

- What is the most important characteristic of Fauvism? The most defining characteristic is the use of intense, non-naturalistic (or arbitrary) color chosen for its emotional and expressive impact rather than for realistic depiction.

- When was the Fauvist movement? Fauvism flourished as a cohesive movement primarily between 1905 and 1908.

- How is Fauvism different from Impressionism? Impressionism aimed to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere using dabs of relatively naturalistic color to create an overall impression. Fauvism used bold, arbitrary, often unmixed color applied in flat areas or energetic strokes to express emotion and create decorative compositions, abandoning realistic representation.

- How is Fauvism different from Expressionism? Both used intense color and distortion for emotional effect. However, Fauvism (especially French Fauvism) often focused on visual pleasure, harmony, and decorative qualities, inspired by light and landscape. German Expressionism frequently explored darker themes of angst, psychology, and social commentary, often using harsher, more dissonant color combinations. Fauvism is considered a precursor and influence on German Expressionism.

- Did Fauvism influence later art movements? Yes, Fauvism significantly influenced German Expressionism and contributed broadly to the liberation of color in Modern Art, impacting many subsequent artists and movements that explored expressive or abstract color, such as Orphism and pure color abstraction.

- Where can I see Fauvist art? Major collections are held in leading modern art museums worldwide, including the Centre Pompidou (Paris), MoMA (New York), Tate Modern (London), the Hermitage (St. Petersburg), and the Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia). Check listings for the best museums for modern art.

- What kind of subjects did the Fauves paint? Despite their radical style, the Fauves often painted traditional subjects like landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and interiors. Their innovation lay in how they painted these subjects, using color and form expressively rather than realistically.

- What techniques did Fauvist artists use? They often used pure, unmixed colors directly from the tube, applied with bold, visible brushstrokes (sometimes impasto). They frequently worked alla prima (wet-on-wet) and sometimes left areas of raw canvas exposed to enhance vibrancy. Their focus was on spontaneous application rather than meticulous layering or blending.

- What is the relationship between Fauvism and Cubism? While distinct movements, there is a connection. Georges Braque, a key Fauvist artist, transitioned from Fauvism to co-found Cubism with Pablo Picasso. Fauvism's simplification of form and emphasis on the two-dimensional surface may have indirectly influenced the Cubist exploration of form and space, although Cubism moved away from Fauvism's intense, arbitrary color palette towards more muted tones initially.