Expressionism: The Ultimate Guide to Art That Feels Deeply

Dive into Expressionism, the art movement that put raw emotion first. This ultimate guide explores its origins, key artists (Munch, Kandinsky, Schiele), defining characteristics, influence on film/music, the 'Degenerate Art' era, and why its intense focus on inner feeling still resonates deeply today. Includes personal reflections from an artist.

Expressionism: The Ultimate Guide to Art That Feels Deeply

Ever felt like the world outside doesn't quite match the storm, or the quiet intensity, brewing inside you? Like reality is just… too neat, too polite to capture the raw, messy truth of being human? If so, you might have a kindred spirit in Expressionism. It's an art movement that decided objective reality was, frankly, a bit boring. It's less about what the artist sees and more about what they feel, a direct line from their inner world to the canvas. As an artist myself, I often find this resonates deeply – the urge to push past mere representation to get to the emotional core of a subject, something you can see in my own paintings.

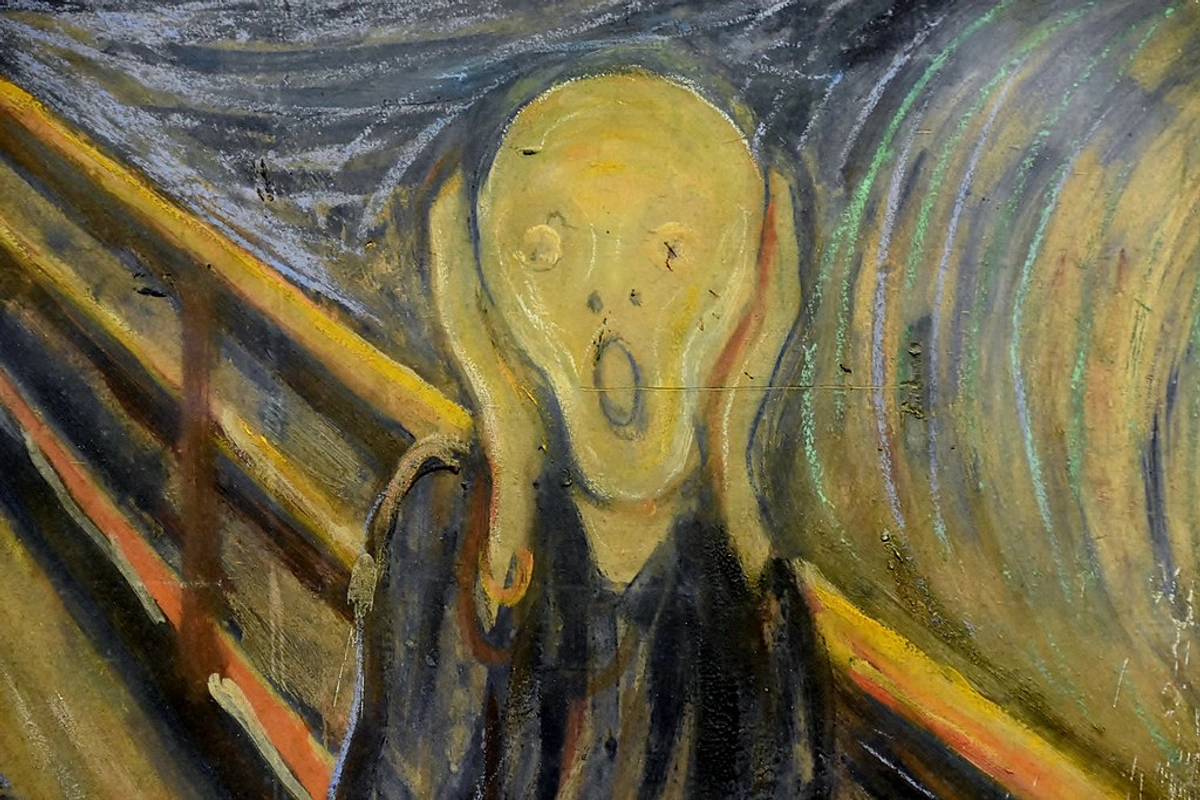

Think of it less as an art style and more as an art attitude. Expressionist artists cranked up the volume on subjective experience, using bold colours, distorted forms, and energetic brushwork to show us not just what they saw, but how they felt. It’s art with its heart, and sometimes its anxieties, worn firmly on its sleeve. It's like the difference between a polite smile and an uncontrollable sob – both are human expressions, but one definitely tells you more about the inner state. And honestly, who hasn't felt a bit like Edvard Munch's "The Scream" on a Monday morning?

This guide aims to be your companion in exploring this fascinating, sometimes challenging, but deeply rewarding corner of the art history landscape. We'll unpack what Expressionism is, where it came from, who the key players were, its defining characteristics, its reach beyond painting, and why it still feels so relevant today.

What Is Expressionism, Really? Beyond the Label

At its core, Expressionism is a tendency in art (primarily emerging in the early 20th century, especially in Germany and Austria) that prioritizes the artist's inner world – their emotions, psychological state, and subjective responses – over depicting the external world accurately or realistically. The term itself, first used in this context around 1910, often linked to critics like Herwarth Walden or Wilhelm Worringer, highlights this focus on 'expressing' inner feeling rather than 'impressing' external reality.

If Impressionism was about capturing the fleeting impression of light and colour on the eye, Expressionism was about projecting the enduring expression of the soul onto the canvas. It wasn't about making pretty pictures for the living room (though some are undeniably beautiful in their own way). It was about grappling with the big stuff: life, death, modernity, the human condition, and the anxieties brought on by rapid industrialization, burgeoning urbanization, and the tense political climate leading up to World War I. It's less "Here's a tree" and more "Here's how this specific tree makes me feel deep down in my gut, maybe because it looks like it's screaming." Sometimes, when I'm trying to paint a feeling, the shapes just have to twist like that – reality feels too rigid to hold the emotion.

Key ideas driving Expressionism include:

- Subjectivity Over Objectivity: The artist's feelings about the subject matter are more important than the subject matter itself. Reality is filtered through an emotional lens.

- Emotional Intensity: Art becomes a vehicle for conveying strong emotions – anxiety, fear, alienation, spirituality, ecstasy, despair.

- Distortion for Effect: Forms, colours, and perspectives are deliberately distorted to enhance the emotional impact, not because the artist couldn't draw 'correctly'. Think of the elongated figures in Schiele's portraits or the jagged cityscapes of Kirchner.

- Rejection of Bourgeois Values: Many Expressionists felt alienated by the conventional, materialistic society of their time and sought a more authentic, primal form of expression.

Where Did It Come From? Roots of Raw Emotion and Unease

Expressionism didn't just appear out of thin air. Like most significant art styles, it had roots and influences. The turn of the 20th century was a period of massive upheaval – rapid industrialization, burgeoning urbanization, rising social tensions, and a growing sense of unease that would eventually culminate in World War I. Artists felt this psychic turbulence deeply and sought new ways to express it.

This was also a time when the inner world was becoming a subject of intense interest, thanks to figures like Sigmund Freud exploring the subconscious. Expressionism, in a way, was the artistic counterpart to this psychological exploration, bringing the hidden depths of the psyche to the surface. Movements like the Vienna Secession, with its focus on subjective experience and decorative symbolism (think Gustav Klimt's influence on Egon Schiele), also contributed to this broader shift away from academic realism.

Key precursors and influences include:

- Vincent van Gogh: Although often categorized as Post-Impressionist, Van Gogh's swirling brushwork, intense colours, and emotionally charged depictions of landscapes and people were a huge inspiration. His art clearly showed his inner state, like in his "Starry Night Over the Rhône".

- Edvard Munch: The Norwegian painter's work, particularly "The Scream," is practically a manifesto for Expressionism, capturing primal fear and existential angst. His series "The Frieze of Life" explored themes of love, fear, and death with raw emotional power.

- Paul Gauguin: His use of symbolic colour and flattened forms, seeking a more "primitive" and spiritual expression, also paved the way.

- Fauvism: Emerging slightly earlier in France, the Fauves (link to Fauvism guide), like Matisse, used wild, non-naturalistic colours, which directly influenced the German Expressionists, though the Germans often imbued their colours with more angst and psychological weight. Think of Matisse's vibrant "Woman with a Hat" compared to Kirchner's intense palette.

- "Primitive" Art: Many Expressionists were fascinated by the art of non-Western cultures (African, Oceanic) and European folk art, seeing in them a directness, emotional power, and spiritual depth lacking in academic European traditions. This interest in the raw and unfiltered was a direct challenge to established norms, as explored in the influence of non-western art on modernism.

These threads combined in the fertile, if anxious, ground of early 20th-century Germany and Austria, giving rise to distinct Expressionist groups and individual artists who felt compelled to express the turbulent spirit of the age. This historical and psychological backdrop directly fueled the visual characteristics we see in their work.

Key Characteristics: The Look and Feel of Expressionism

So, how do you spot an Expressionist work? While diverse, certain visual traits tend to dominate, all serving the primary goal of conveying inner feeling. Paying attention to the details – the texture of the brushwork, the specific way colors clash or blend, the quality of the line – can reveal the emotional core the artist is trying to communicate:

- Colour: Often bold, intense, clashing, and non-naturalistic. Skies might be red, faces green, shadows purple – whatever colour best conveys the desired emotion, regardless of reality. Colour isn't just descriptive; it's emotive. It hits you viscerally, like a sudden mood swing. Ever seen a sky that just felt red, even if it wasn't? Expressionists painted that feeling. It's a deliberate choice, like picking a specific chord in music to evoke a mood.

- Brushwork: Typically vigorous, energetic, and visible. Strokes can be swirling, jagged, thick, or applied rapidly, adding to the sense of urgency and emotional intensity. Think less about smooth blending, more about direct impact and the artist's physical engagement with the canvas. This is where you really feel the artist's hand and energy, the raw act of creation.

- Form: Often distorted, elongated, angular, or simplified. Figures and objects might look 'wrong' or crude by traditional standards, but this distortion serves to heighten the emotional expression – a stretched figure might convey alienation (like in Schiele's self-portraits), sharp angles might suggest anxiety (seen in Kirchner's street scenes). It's not a mistake; it's a statement about how the inner world perceives the outer.

- Line: Used expressively, often thick, jagged, or fluid, contributing to the overall emotional tone and structure. Think of the stark, angular lines in Kirchner's cityscapes or the raw, nervous energy of line in Schiele's portraits. Line becomes a carrier of feeling.

- Perspective: Often flattened or skewed. The traditional rules of perspective might be ignored to create a more claustrophobic, unsettling, or dreamlike space, reflecting an internal rather than external reality. It pulls you into the artist's headspace.

- Subject Matter: Frequently focused on the inner life – psychology, spirituality, alienation, the intensity of urban life, primal emotions, and the darker aspects of human experience. Even landscapes or still lifes often feel imbued with intense feeling, reflecting the artist's state of mind rather than objective observation. Consider Franz Marc's animals, which he painted to express a spiritual purity he felt was lost in humanity.

These visual elements don't operate in isolation; they work together to create a unified emotional impact, making the artwork a direct channel for the artist's subjective experience. It's a total sensory and emotional assault, in the best possible way.

Expressionists also favored certain media that lent themselves to this raw, direct approach:

- Woodcuts: The bold lines and stark contrasts inherent in woodcut printing were perfectly suited to the Expressionist aesthetic, particularly for Die Brücke artists who revived this traditional German medium. It allowed for powerful, graphic images that felt raw and immediate, like a shouted message.

![]()

The Main Groups: Expressionism's Inner Circles

While individual artists worked in an Expressionist vein, two main groups in Germany became particularly influential and are synonymous with the movement. These collectives provided a space for artists to share ideas, exhibit together, and push the boundaries of art in a shared direction, though their approaches differed significantly.

Die Brücke (The Bridge) - 1905, Dresden

Founded by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, and Fritz Bleyl, Die Brücke aimed to bridge the past and the future, rejecting academic norms for a more direct, intense style. They were inspired by medieval German woodcuts and the art of Gauguin and Munch.

- Focus: Often depicted gritty urban life, cabarets, nudes (exploring themes of nature and freedom), and landscapes, often with a sense of raw energy and confrontation. Their work frequently felt like a direct response to the perceived artificiality and tension of modern urban existence.

- Style: Characterized by intense, often clashing colours, jagged lines, distorted forms, and a raw, sometimes aggressive energy. Their work can feel confrontational, reflecting the anxieties of modern life. It's like the city screaming back at you.

- Key Artists: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, Emil Nolde (joined later).

Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) - 1911, Munich

Co-founded by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, Der Blaue Reiter was a looser association united by a shared interest in spiritual and symbolic aspects of art, as well as the expressive power of colour and form. Other key members included August Macke, Gabriele Münter, and Paul Klee.

- Focus: More inclined towards spirituality, symbolism, the connection between humans and nature (especially animals for Marc), folk art, and the move towards abstraction. They sought a more harmonious, even mystical, expression compared to Die Brücke. It was less about the harshness of the city and more about finding deeper truths.

- Style: While still using intense colour, their approach could be more lyrical, symbolic, and abstract than Die Brücke. Kandinsky, in particular, pushed towards complete abstraction, believing colour and form alone could express spiritual truths (see History of Abstract Art).

- Key Artists: Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, Gabriele Münter, Paul Klee.

While both groups were Expressionist in their focus on inner experience, Die Brücke often felt like a raw, urban scream, confronting the viewer with the harsh realities and anxieties of modern life. Der Blaue Reiter, in contrast, leaned towards a more spiritual, abstract whisper, seeking harmony and deeper meaning through colour and form. It's the difference between a punch in the gut and a transcendental meditation.

Feature | Die Brücke (The Bridge) | Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) |

|---|---|---|

| Founded | 1905 | 1911 |

| Location | Dresden | Munich |

| Key Focus | Urban life, social critique, nature | Spirituality, symbolism, abstraction |

| Style | Raw, jagged, distorted, intense colour | Lyrical, symbolic, abstracting, vibrant colour |

| Key Artists | Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Heckel, Nolde | Kandinsky, Marc, Macke, Münter, Klee |

![]()

Meet the Expressionists: Key Figures

Beyond the groups, several artists are central to the Expressionist story, each bringing a unique intensity to the movement. These figures, some associated with the groups and others working independently, defined the diverse faces of Expressionism:

- Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944): A precursor whose work, particularly his series "The Frieze of Life," profoundly influenced Expressionism. His focus on themes of love, fear, death, and melancholy, expressed through swirling lines and intense colour, captured the psychological landscape of modern existence. "The Scream" remains his most iconic depiction of existential angst, but works like "Madonna" and "Anxiety" are equally powerful. He really laid the groundwork for art as emotional confession.

- Wassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944): A pioneer of abstract art and a leading figure in Der Blaue Reiter. Kandinsky believed in the spiritual power of colour and form, aiming to create art that resonated with the viewer's soul like music. His move towards pure abstraction was driven by this desire for spiritual expression, seen in works like "Composition VIII" and "Der Blaue Reiter". He wanted you to feel the colours and shapes, not just recognize objects.

- Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (German, 1880-1938): A founder of Die Brücke and a key chronicler of urban life in Berlin. His street scenes, like "Street, Berlin" and "Potsdamer Platz", with their jagged forms, clashing colours, and anxious figures, vividly capture the alienation and dynamism of the modern city. His style is raw, angular, and intensely expressive – you can almost hear the noise and feel the tension.

- Egon Schiele (Austrian, 1890-1918): Known for his raw, often unsettling portraits and self-portraits. Schiele used distorted forms, thin, nervous lines, and stark colours to expose the psychological vulnerability, sexuality, and inner turmoil of his subjects, including himself. His self-portraits, such as "Self-Portrait with Erotic Motifs" and "Seated Male Nude (Self-Portrait)", are intensely personal and confrontational. Looking at them feels like peering directly into someone's soul, even if it's uncomfortable.

- Franz Marc (German, 1880-1916): A co-founder of Der Blaue Reiter, known for his vibrant paintings of animals, which he saw as embodying a spiritual purity lacking in humanity. He developed a symbolic use of colour (blue for spirituality, yellow for joy, red for violence) to convey the inner essence of his subjects, famously in "Blue Horse I" and "The Fate of the Animals". His animals aren't just animals; they're symbols of a deeper connection to the world.

Expressionism Beyond Germany and Painting: A Wider Reach

While Germany and Austria were the heartland, the Expressionist spirit resonated elsewhere and influenced other art forms and media. It wasn't just confined to canvas and paint; the urge to express inner reality spilled into many creative fields, proving the power of this emotional approach.

- Painting Elsewhere: The focus on subjective experience and expressive distortion wasn't limited to German-speaking countries.

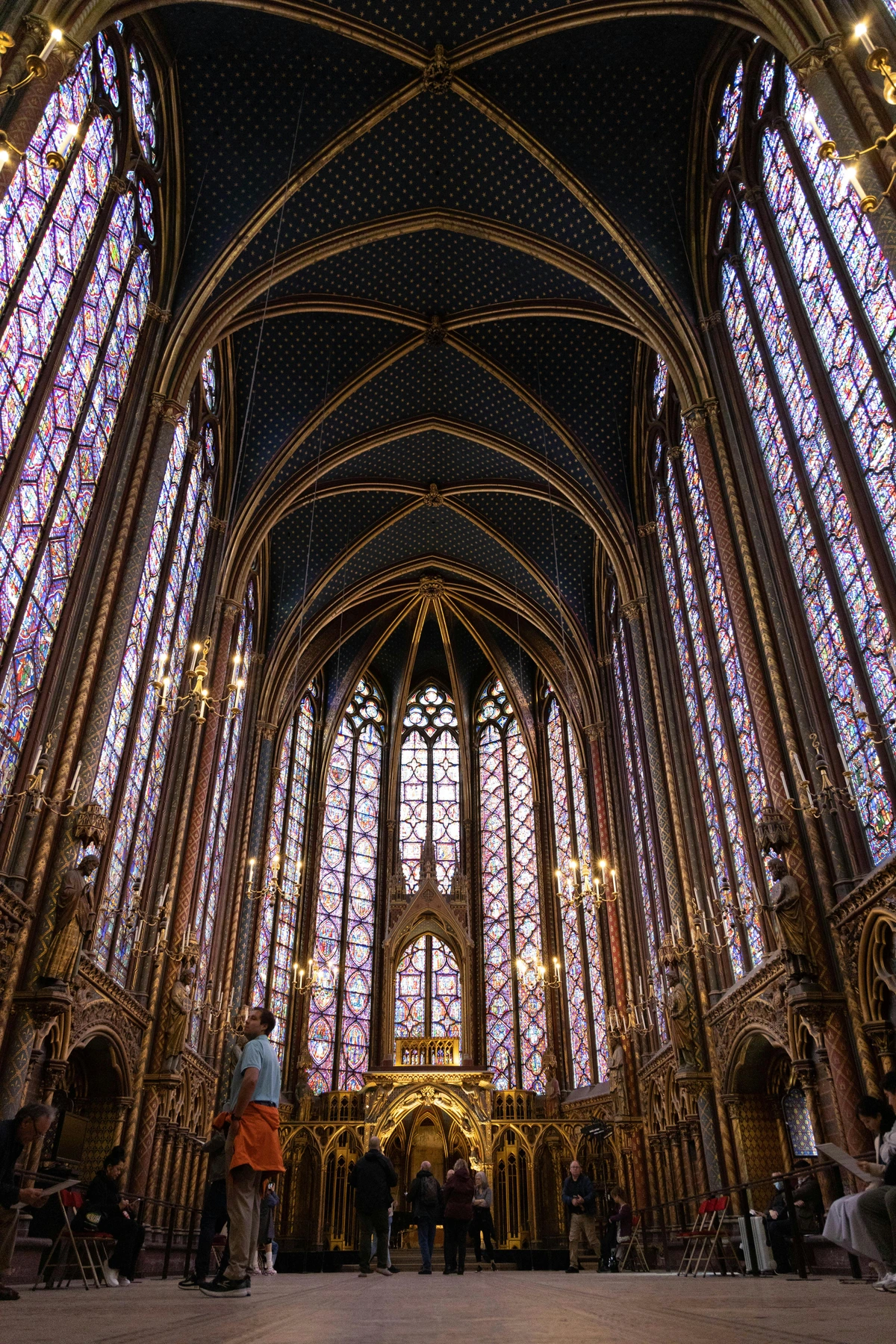

- France: Georges Rouault developed a powerful, deeply felt style with thick black outlines reminiscent of stained glass, often depicting religious themes, clowns, and judges with profound emotional weight. Chaïm Soutine, a Lithuanian-Jewish painter working in Paris, created intensely expressive landscapes and portraits with turbulent brushwork and distorted forms, conveying a sense of visceral emotion.

- Other Regions: While less cohesive movements, artists in other countries also adopted Expressionist tendencies, such as the Belgian James Ensor with his grotesque masks and unsettling crowd scenes, or the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian in his early, pre-De Stijl works like "Evening; Red Tree". Even American artists like Marsden Hartley showed strong Expressionist leanings in their landscapes.

- Other Visual Arts: The Expressionist impulse wasn't confined to painting. It profoundly impacted:

- Sculpture: Artists like Ernst Barlach created powerful, often simplified and monumental figures in wood or bronze, capturing intense emotional states like grief or ecstasy. Wilhelm Lehmbruck's elongated, melancholic figures also embody the Expressionist spirit. These weren't just static forms; they were emotional volumes.

- Printmaking: As mentioned, woodcuts, with their bold lines and stark contrasts, were particularly favored by Die Brücke artists for their raw, direct expressive potential. Linocuts and etchings were also used to create emotionally charged graphic works. The print medium allowed for wide dissemination of these intense images.

- Other Arts: The influence extended far beyond the visual realm, demonstrating the pervasive nature of the Expressionist mindset in early 20th-century culture:

- Film: German Expressionist cinema (e.g., The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu, Metropolis) used distorted sets, dramatic lighting (chiaroscuro), and exaggerated acting to create nightmarish, psychological atmospheres, mirroring the visual style and emotional intensity of the paintings. It's fascinating how they built physical sets to feel distorted, creating a world that matched the internal state.

- Literature & Theatre: Writers and playwrights explored subjective states, used fragmented language, and focused on inner conflict, alienation, and social critique, often with heightened emotional intensity. Playwrights like Georg Kaiser and Ernst Toller created 'Station Dramas' that followed a protagonist's emotional journey, focusing on their internal landscape. Think of the raw emotion in plays like Woyzeck.

- Architecture: Though less widespread and often more theoretical, Expressionist architecture featured distorted forms, jagged lines, and a focus on conveying emotion or spiritual ideas through structure, rather than purely functional design. Examples include Erich Mendelsohn's Einstein Tower, which feels almost organic and dynamic.

- Music: Composers like Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg explored atonality and dissonance to express intense psychological states, mirroring the emotional intensity and departure from traditional forms seen in visual Expressionism. It's like the musical equivalent of clashing colours and distorted forms, designed to make you feel the unease.

Why Does It Still Matter? Legacy, Influence, and Persecution

Expressionism's raw honesty and focus on inner experience had a massive impact on the trajectory of modern art and continues to resonate today. It was a radical break from the past, asserting the artist's right to express their internal world above all else.

- Paving the Way for Abstraction: Especially through Kandinsky and Der Blaue Reiter, Expressionism was a crucial step towards fully abstract art, demonstrating that colour and form could be expressive in their own right, independent of representational subject matter. It opened the door to a whole new way of seeing and feeling art.

- Abstract Expressionism: The post-WWII American movement, featuring artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, drew heavily on the Expressionist idea of art as a direct expression of the artist's psyche, albeit often in purely abstract terms. The focus remained on conveying deep emotion through non-representational means. They took the emotional core and blew it up to monumental scale.

- Neo-Expressionism: In the late 1970s and 1980s, artists like Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Jean-Michel Basquiat revived figurative painting with a raw, expressive energy, reacting against the perceived coolness of Minimalism and Conceptual art. They returned to subjective, often intense, subject matter and vigorous brushwork, proving the enduring power of the expressive figure.

- Influence on Later German Art: Even after the Nazi era, the expressive impulse remained strong in German art, influencing movements and artists grappling with the country's history and identity. Artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz, while often classified under Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), carried forward Expressionism's sharp social critique and distorted forms to depict the harsh realities of post-WWI Germany, showing how these ideas evolved.

- Persecution by the Nazis: The radical nature of Expressionism was seen as a threat by the Nazi regime in Germany. They labeled it "Degenerate Art" (Entartete Kunst), a term used to condemn virtually all modern art as un-German, Jewish, or Communist. In 1937, they organized the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition in Munich, showcasing Expressionist and other modern works alongside art by the mentally ill, intending to ridicule and condemn them. This was contrasted with the state-approved "Great German Art Exhibition." Many Expressionist artists were persecuted, forbidden to work, dismissed from teaching positions, or forced into exile, and their works were confiscated or destroyed. For example, Emil Nolde's work, despite his early support for the Nazi party, was heavily featured in the "Degenerate Art" exhibition. This dark chapter highlights just how powerful and challenging this art was considered at the time – art that could express inner truth was a threat to a totalitarian regime built on lies.

- Enduring Relevance: In a world still grappling with anxiety, alienation, and the search for meaning, Expressionism's willingness to confront uncomfortable truths and prioritize authentic feeling remains potent. It reminds us that art can be more than just decoration; it can be a vital way to process and communicate the complexities of being human. You can even find echoes of this emotional intensity in contemporary art available today, including in my own work where I strive to let the inner feeling guide the brush.

Experiencing Expressionism: Where and How to Look

Looking at Expressionist art requires a slight shift in perspective. Instead of asking "What is this of?", try asking "What does this feel like?". It's an invitation to connect on an emotional level.

- Engage Emotionally: Allow yourself to react to the colours, lines, and distortions. Does it make you feel uneasy, excited, sad, agitated? Why? There's no single 'correct' emotional response. Your feeling is valid. Pay attention to the texture of the paint, the visible brushstrokes – they are traces of the artist's physical and emotional energy. For instance, look at the green face in a portrait by Kirchner or Schiele. Instead of asking 'Why is it green?', ask 'What emotion does this green convey? Does it feel sickly, unnatural, vibrant in a strange way? What does that colour do to the feeling of the portrait?'.

- Look Beyond Realism: Don't get hung up on whether the anatomy is 'right' or the colours 'realistic'. Understand these are deliberate choices made for expressive impact. They are tools to convey the artist's inner state. You can learn more about analyzing art here.

- Consider the Context: Knowing a little about the artist's life or the historical period can deepen understanding, but the primary experience is the direct encounter with the work itself. Let it speak to you first.

- Where to See It: Many major museums worldwide have significant Expressionist holdings. Notable collections can be found in Germany (e.g., Brücke Museum Berlin, Lenbachhaus Munich), Austria (Leopold Museum Vienna), New York (MoMA, Neue Galerie), and elsewhere. Visiting museums, whether grand institutions or smaller spaces perhaps like the one near 's-Hertogenbosch where I have my own works, can offer powerful encounters and inspiration. Seeing the brushwork and scale in person makes a huge difference, allowing you to feel the raw energy the artist poured into the canvas.

Expressionism FAQ: Quick Answers

- Q: What's the main difference between Expressionism and Impressionism?

- A: Impressionism focuses on capturing the external visual impression of a moment (light, atmosphere). Think of it like taking a photo of a sunset. Expressionism focuses on projecting the internal emotional or psychological state of the artist. Think of it like painting how that sunset makes your soul ache. It's outside-in vs. inside-out.

- Q: Who are the most famous Expressionist artists?

- A: Edvard Munch, Wassily Kandinsky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Egon Schiele, Franz Marc are among the most recognized names associated with the core movement.

- Q: Is Expressionism always dark and angsty?

- A: While anxiety and turmoil are common themes, especially in Die Brücke and Austrian Expressionism, Der Blaue Reiter explored more spiritual and harmonious themes. Expressionism covers a range of intense emotions, not just negative ones.

- Q: Why are the figures and objects so distorted?

- A: Distortion is a key tool used by Expressionists to amplify emotion. By bending or breaking the rules of realistic representation, they could better convey inner feelings like tension, ecstasy, or despair. It's a deliberate expressive choice, not a lack of skill.

- Q: How does Expressionism relate to Fauvism or Cubism?

- A: Expressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism were all early 20th-century movements breaking from tradition. Fauvism shared Expressionism's use of intense, non-naturalistic color but focused more on decorative effect and joy rather than psychological depth. Cubism, led by Picasso, focused on fragmenting and reassembling forms to explore multiple perspectives, prioritizing intellectual analysis over emotional expression, though some Cubist works can certainly evoke feeling.

Conclusion: The Enduring Scream (and Whisper)

Expressionism might not always be easy viewing. It demands something from us, asks us to feel along with the artist, to look beyond the surface. Sometimes it feels like a scream, other times like an intense, vibrant whisper of the soul.

It reminds me that art isn't just about technical skill or replicating reality. It's about connection, communication, and the courage to show the world how things feel on the inside. It's a vital part of the story of art, and its echoes continue to shape how artists express themselves, including in my own journey trying to capture feeling on canvas. Whether you find it jarring or exhilarating, Expressionism's raw emotional power is undeniable. And in a world that sometimes feels too polished, a bit of raw honesty can be incredibly refreshing. It's a reminder that art, at its best, is a direct line from one soul to another, bypassing the polite facade to get to the messy, beautiful truth.