How Non-Western Art Sparked the Modernist Revolution: An Artist's View

Explore how African masks, Japanese prints, and other non-Western art forms profoundly influenced Modern masters like Picasso, Matisse, and Van Gogh, reshaping Western art forever. An artist's personal take.

Beyond the West: How Non-Western Art Ignited the Modernist Revolution

Let's be honest, when we think of Modern Art – Cubism, Expressionism, wild colours, broken shapes – it often feels like a purely European or American affair. Something cooked up in Paris studios or New York lofts. But, like discovering your favourite underground band actually had a massive marketing budget, the story is far richer and, frankly, more complicated.

Modernism wasn't just a reaction against Western tradition; it was fueled by a fascination, a sometimes problematic obsession, with art from outside the West. It turns out, the revolutionary spirit of artists like Picasso and Matisse owed a significant debt to African masks, Japanese prints, and Oceanic sculptures.

It's a bit like that feeling when you're stuck in a creative rut – maybe you've been painting the same way for years, or like me, sometimes staring at a blank canvas feeling like your brain has gone on vacation. You need something new, a different perspective. For many Modern artists, that jolt came from encountering radically different ways of seeing and representing the world.

This is the story of that encounter – a journey into how 'foreign' aesthetics didn't just inspire Modern art, they fundamentally reshaped it.

What Exactly Do We Mean by "Non-Western Art"?

Okay, let's address the elephant in the room. "Non-Western Art" is a bit of a clumsy, catch-all term, isn't it? It defines vast, incredibly diverse cultures primarily by what they aren't (i.e., not European or North American). It lumps together the intricate wood carvings of Central Africa, the serene ink paintings of Dynastic China, the dynamic sculptures of Oceania, and the symbolic art of Indigenous Americas under one umbrella. It’s like calling everything outside your own city 'not-my-city'.

It's important to remember the sheer diversity we're talking about. While the term is problematic today, reflecting a Western-centric view, it's the historical lens through which these influences were often framed. We'll mainly focus on the influences most prominent in early Modernism, particularly:

- African Art: Especially masks and sculptures from West and Central Africa.

- Oceanic Art: Art from the islands of the Pacific, including Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia.

- Japanese Art: Specifically Ukiyo-e woodblock prints from the Edo period.

It's worth noting that other traditions, like Islamic art (think intricate geometric patterns and calligraphy) or Indian miniatures (with their vibrant colours and narrative detail), also held fascination for some Western artists, though perhaps less centrally to the initial explosion of Modernism than African or Japanese art. Pre-Columbian art from the Americas also offered compelling forms. These were all part of a broader, albeit often unequal, global exchange of visual ideas.

Keeping the breadth and depth of these individual traditions in mind is crucial, especially when we talk about how they were interpreted (and sometimes misinterpreted) by Western artists. So, given this vast world of art outside their own bubble, why did Western artists suddenly start paying attention?

The "Discovery": Why Did Western Artists Suddenly Look Elsewhere?

So, why the sudden interest around the turn of the 20th century? It wasn't just random chance. Several factors converged:

- Dissatisfaction with Tradition: Many avant-garde artists felt stifled by the rigid rules and realistic focus of academic European art. They were searching for more direct, expressive, and 'authentic' forms. Think of it as being tired of only hearing classical music and suddenly discovering jazz or blues – the raw energy is captivating.

- Colonial Expansion: This is the uncomfortable part. European colonialism was at its peak. While horrific in its impact, it flooded Europe with artifacts and objects from colonized regions, filling ethnographic museums and private collections. Artists encountered these objects, often stripped of their original context and meaning.

- World Fairs & Exhibitions: Events like the Paris Universal Exposition brought cultures from around the globe (or at least, European interpretations of them) to a wider audience, including artists.

- Opening of Japan: After centuries of isolation, Japan opened to the West in the mid-19th century, leading to a craze for Japanese goods and art (Japonisme).

- Photography: The rise of photography perhaps pushed painters away from pure realism, freeing them to explore form, colour, and emotion more abstractly.

Artists weren't just looking for new subjects; they were searching for entirely new visual languages. They found them in the bold abstractions, the flattened perspectives, and the perceived spiritual intensity of art from Africa, Oceania, and Japan. This search for new ways to see and represent the world directly fueled the emergence of groundbreaking movements like Primitivism and Japonisme, which we'll dive into next.

The Raw Power: How "Primitivism" Shook Things Up

One of the most significant, and debated, streams of influence falls under the banner of Primitivism. This term itself is loaded, often reflecting a romanticized, condescending, and naive Western view of non-Western cultures as being more 'elemental,' 'instinctive,' or 'spiritual' – closer to the supposed origins of humanity. It's crucial to understand that while the artists were genuinely inspired by the forms they saw, their understanding of the meaning and sophisticated traditions behind these objects was often minimal or non-existent. The term 'Primitivism' is problematic today precisely because it frames complex, developed art forms through a biased Western lens.

Despite its problematic origins, the formal impact was undeniable. Artists were struck by:

- Abstraction and Simplification: African and Oceanic carvings often reduced forms to their geometric essentials, discarding naturalistic detail for expressive power. Imagine seeing a face carved into wood, not aiming for a perfect likeness, but for the essence of a feeling or spirit. That's powerful.

- Distortion for Emotional Effect: Features might be exaggerated or altered not for realism, but to convey feeling or spiritual force. Think of eyes widened in awe or mouths contorted in ritualistic cries – these weren't mistakes, they were deliberate choices for impact.

- Directness of Material: A visible engagement with the wood, stone, or other materials used. You could often see the marks of the tools, a raw honesty that felt miles away from the polished finish of academic sculpture.

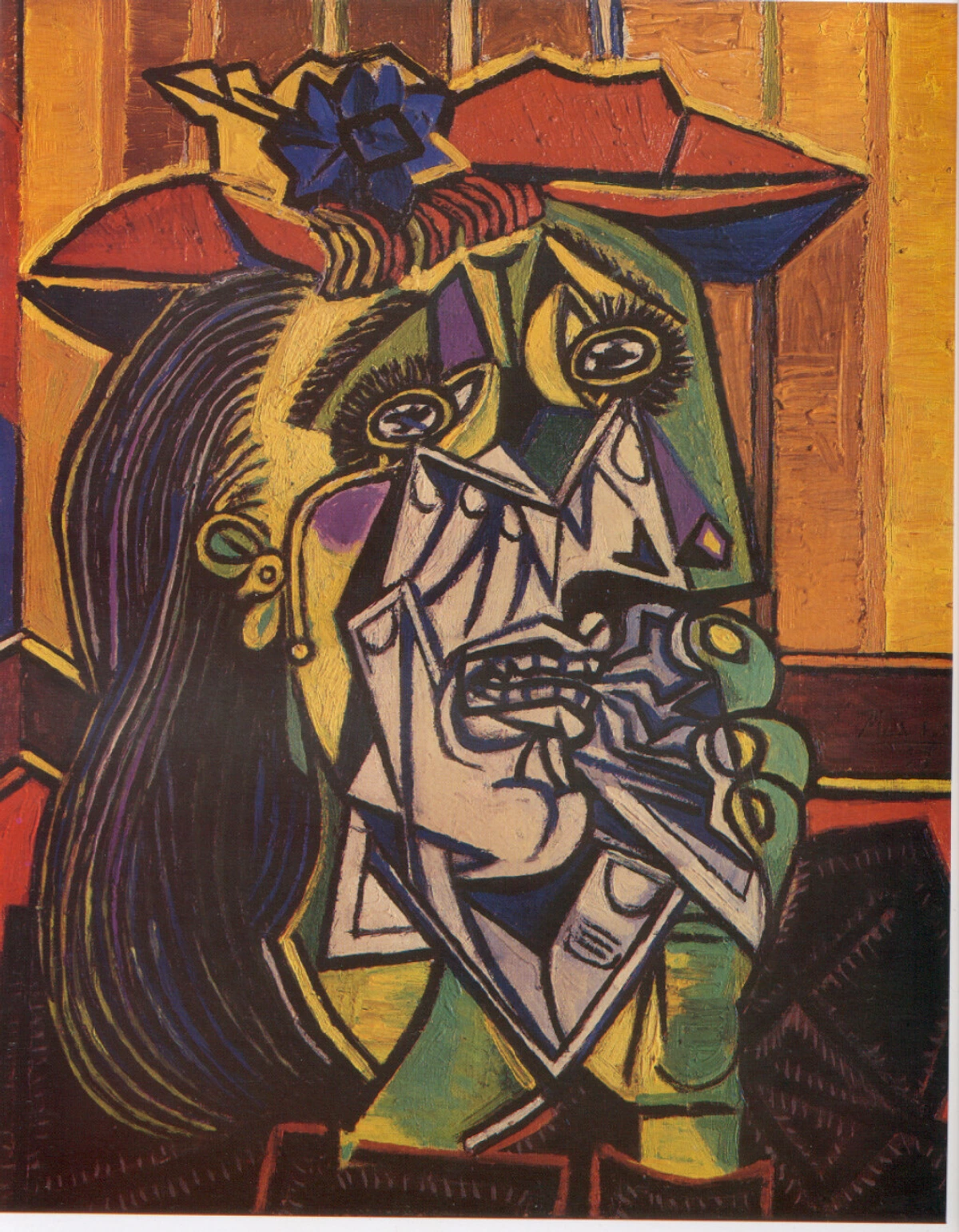

Picasso and the African Mask: The textbook example is Pablo Picasso's encounter with African art around 1906-1907. Seeing Iberian sculptures and African masks (likely in Paris's Trocadéro ethnographic museum) was a revelation. He later described the masks as being 'intercessors... against everything... against the unknown, against everything that's frightening'. This wasn't about understanding the masks' original function or meaning (he likely knew very little); it was about borrowing their formal power – the fractured planes, the bold lines, the conceptual rather than purely visual representation – to shatter traditional European representation and pave the way for Cubism. The faces of the two figures on the right in his groundbreaking work Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) directly reflect this influence, using the visual language of the masks to depict a raw, confrontational energy.

Other Key Figures:

- Henri Matisse: Though initially sharing Picasso's interest, his engagement, particularly in Fauvism, drew on the vibrant colour and expressive forms, seeking a similar directness. His sculpture Reclining Nude (Aurora) (1907) shows a clear simplification and elongation of form reminiscent of African carvings, moving away from classical ideals towards a more elemental representation of the body. His painting The Dance (1910) also uses simplified, bold figures and non-naturalistic color that echoes the expressive power seen in some non-Western art forms.

- Amedeo Modigliani: His iconic elongated figures and mask-like faces, seen in portraits like Jeanne Hébuterne with Hat and Necklace (1917) or his numerous caryatid sculptures, are perhaps the most direct and sustained example of African sculpture's influence on a single artist's style. He adopted the simplified features, almond-shaped eyes, and long necks to create a distinctive, almost totemic presence in his subjects.

- Constantin Brancusi: His radically simplified, often polished sculptures, such as Sleeping Muse (1910) or Bird in Space (begun 1923), echo the reduction of form to its essential core found in African carvings and other non-Western art, seeking universal, timeless shapes. His focus on the inherent qualities of the material also aligns with the directness seen in many non-Western traditions.

- German Expressionists: Groups like Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) were heavily inspired by African and Oceanic art seen in ethnographic museums, admiring its perceived rawness, emotional intensity, and spiritual connection, which aligned with their own goals of expressing inner feeling over external reality (see our Expressionism guide). Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner incorporated the angularity and bold forms into paintings like Street, Dresden (1908), while Emil Nolde's vibrant, sometimes grotesque figures in works like Mask Still Life III (1911) directly reference ethnographic objects, seeking a primal, emotional force. Franz Marc's use of symbolic color and simplified animal forms in works like Blue Horse I (1911) also shows a move towards a more intuitive, less naturalistic representation, influenced by various folk and non-Western art forms.

![]()

Primitivism offered a way out of the perceived constraints of Western naturalism, providing tools for radical formal experimentation. It was a visual vocabulary that felt fresh, powerful, and capable of expressing something beyond mere appearances.

The Charm of the East: Japonisme's Elegant Revolution

Running parallel to Primitivism was Japonisme, the European fascination with Japanese art and culture that swept across the continent, particularly in the latter half of the 19th century. This influence was perhaps less about perceived 'primitiveness' and more about a sophisticated, alternative aesthetic system.

Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, by artists like Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Utamaro, were imported in large numbers (sometimes even as packing material for other goods!). Western artists were captivated by their unique aesthetic qualities:

- Flattened Perspective: Abandoning single-point perspective for areas of flat colour and pattern. It's like looking at a scene not through a window, but seeing it laid out on a surface, where depth is suggested by placement and overlap rather than vanishing points. It feels... different, maybe like seeing something from an unexpected angle, like looking down from a height or across a wide, flat plain.

- Bold Outlines and Strong Compositions: Clear lines defining forms, giving images a graphic punch.

- Asymmetrical Arrangements: Dynamic, off-center compositions that felt fresh compared to the often balanced, pyramidal structures of Western art.

- Unusual Cropping and Viewpoints: Inspired by photographic framing, images might cut off figures or objects abruptly, creating a sense of immediacy and candidness.

- Everyday Subjects: Scenes of daily life, landscapes, theatre – subjects previously considered too mundane for 'high art' in the West.

![]()

Who Was Inspired?

- Impressionists: Artists like Monet, Degas, and Mary Cassatt adopted the flattened perspectives, unusual cropping, and everyday subject matter (check the Impressionism guide). Monet's series paintings, like the Haystacks or Rouen Cathedral series, often employ compositions influenced by Japanese prints, focusing on repeated forms seen from slightly different, sometimes elevated, viewpoints. Degas's paintings and pastels of dancers frequently use dramatic, asymmetrical compositions and sharp cropping that feel directly inspired by Ukiyo-e's dynamic framing. Mary Cassatt, who was a keen collector of Japanese prints, incorporated their flat planes of colour, bold lines, and intimate domestic subjects into her own work, particularly her series of colour prints from 1890-91, like The Bath, which show clear Japanese influence in their design and technique.

- Post-Impressionists: Vincent van Gogh was famously obsessed, collecting prints and incorporating their style into works like Almond Blossoms and his portraits, even painting copies of Ukiyo-e prints. Paul Gauguin also absorbed Japanese aesthetics, particularly the use of flat colour and strong outlines, which fed into his Synthetist style, aiming for a symbolic rather than purely descriptive representation.

- Art Nouveau: The flowing lines, organic forms, and decorative patterns of Japanese art heavily influenced this movement, seen in everything from architecture to jewellery and graphic design. Artists like Aubrey Beardsley and Gustav Klimt show clear echoes of Japanese print aesthetics.

- James Abbott McNeill Whistler: His paintings often feature Japanese motifs and compositions, and he titled many of his works as "arrangements" or "harmonies," reflecting an interest in the formal, decorative qualities admired in Japanese art, moving away from narrative or realistic representation.

Japonisme offered a different kind of escape from Western conventions – one focused on elegance, design, and a different way of structuring pictorial space. It felt sophisticated, modern, and visually exciting.

Beyond the Surface: Seeking Deeper Meaning and Alternative Realities

The influence wasn't just about new shapes and compositions. For many artists, non-Western art seemed to possess a spiritual depth, emotional honesty, or connection to fundamental human experience they felt was lacking in the increasingly industrialized and materialistic West. It was like they were looking for a soul in art, and they thought they found it elsewhere.

This search for something 'more' manifested differently. For the Expressionists, the raw energy perceived in African sculpture resonated deeply with their goal of expressing inner turmoil and intense feeling. They weren't just copying shapes; they were trying to tap into that perceived primal force to express their own feelings about the modern world. The bold, non-naturalistic colours used in many non-Western traditions likely emboldened the Fauves in their own radical use of colour – if art from other cultures could use colour so freely for expressive or symbolic purposes, why couldn't they?

Paul Gauguin's move to Tahiti, for instance, wasn't just a search for exotic subject matter. It was partly a quest for a 'simpler,' more 'spiritual' existence, which he tried to express through his art inspired by Polynesian culture (though his perspective was heavily filtered through his own desires and Western lens). He sought a connection to something he perceived as more authentic, more deeply felt, than the bourgeois European life he left behind. His painting Vision After the Sermon (1888), while not directly referencing Oceanic art, uses flattened space, bold colour, and symbolic forms inspired by Japanese prints and folk art to depict a spiritual, non-naturalistic reality – a direct link between formal borrowing and the search for deeper meaning.

Beyond Africa and Japan, other traditions offered different kinds of inspiration. Islamic art, with its intricate geometric patterns and calligraphy, appealed to artists like Matisse and the Art Nouveau designers, offering a model for complex, non-representational decoration and a different approach to space and form. Indian miniatures, with their vibrant palettes and detailed narrative scenes, fascinated artists interested in color and storytelling, though their influence was perhaps less widespread in the initial phase of Modernism. Pre-Columbian art from the Americas, with its monumental sculpture and complex symbolism, also provided compelling examples of alternative artistic systems.

This engagement represented an alternative way of being and seeing, a departure from Western rationalism towards intuition, symbolism, and direct feeling. Understanding how to read a painting involves appreciating these less tangible influences too – the feeling, the perceived spirit, the emotional resonance that artists were trying to capture, often inspired by what they saw in non-Western art.

A Complicated Legacy: Inspiration vs. Appropriation

We can't talk about this topic without acknowledging the ethical complexities. Was this cross-cultural borrowing genuine appreciation, or was it appropriation rooted in colonial power dynamics? Honestly, it's often a messy mix of both. It's the art historical equivalent of a difficult family history – you can admire the achievements, but you can't ignore the uncomfortable truths.

- Lack of Context: Artists frequently took forms and motifs completely out of their original cultural, spiritual, and social contexts. An African mask wasn't just a striking object; it had specific functions and meanings often ignored by the borrower. Imagine someone taking a religious icon from your culture and using its shape purely for decoration, without any understanding of its sacred purpose. That's kind of what was happening.

- Power Imbalance: European artists were borrowing from cultures often under colonial rule or perceived as 'lesser.' The exchange was rarely on equal terms. The objects themselves were often acquired through violent or exploitative means, ending up in European museums as 'artifacts' rather than 'art' in the Western sense.

- Stereotyping: The 'Primitivist' gaze often reinforced stereotypes about non-Western peoples being exotic, savage, or hypersexual, projecting Western fantasies onto complex cultures.

Thinking about this makes me pause. It's easy to admire the aesthetic breakthrough of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, but harder to ignore the context in which those African forms were 'discovered' and utilized. It doesn't negate the artistic innovation, but it adds layers of meaning and responsibility. It forces us to consider the agency and sophistication of the source cultures themselves – these weren't simple, naive objects, but products of rich, complex artistic traditions with their own histories, purposes, and aesthetic principles, often developed over centuries. Western artists were encountering the tip of a very deep iceberg, and often only saw what they were looking for – a tool to break free from their own traditions – rather than the full, nuanced reality. It connects to broader questions about what makes art 'important' – is it purely aesthetics, or does context and ethics play a role?

This conversation continues today, particularly in contemporary art. Many contemporary artists, especially those from the African diaspora or other formerly colonized regions, are actively engaging with this history, reclaiming narratives, and challenging the Western gaze. Exploring the work of artists highlighted in our spotlight on contemporary African diaspora artists offers powerful examples of this ongoing dialogue.

The Lasting Impact: A Permanent Shift in Art

Problematic or not, the influence of non-Western art on Modernism was profound and irreversible. It:

- Shattered Traditional Representation: Provided tools and justification for moving beyond naturalism.

- Fueled Abstraction: Showed that art could be powerful without mimicking reality, paving the way for movements like Abstract Expressionism and the broader history of abstract art.

- Expanded Visual Language: Introduced new approaches to form, colour, composition, and material.

- Challenged Western Supremacy: Implicitly questioned the idea that the European tradition was the only valid form of 'high art'.

These encounters fundamentally changed the history of Western art. The seeds sown by these interactions continue to bear fruit, influencing artists globally. Perhaps even influencing the kind of bold, abstract art you might find available here. My own journey as an artist (see my timeline) has involved looking at countless sources, sometimes finding unexpected sparks in places I didn't anticipate – a pattern in a textile, the composition of a photograph, the raw energy of a child's drawing. It's a reminder that inspiration is a global, messy, wonderful thing.

Where Can You See These Connections?

Many major museums worldwide have collections that allow you to see these dialogues firsthand. Look for Modern art sections in institutions like:

- The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York (Best Galleries in New York)

- Centre Pompidou, Paris (Best Galleries in Paris)

- Tate Modern, London (Best Galleries in London)

- Major ethnographic museums often hold the source objects. Look for institutions like the British Museum in London or the Musée du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac in Paris.

Even smaller regional museums, like the one showcasing some of my own work near 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, can reveal surprising connections if you look closely at how artists absorb and transform influences throughout their artistic journey.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What is Primitivism in art?

- A: Primitivism refers to the fascination of Western Modern artists with the art of non-Western cultures (particularly from Africa, Oceania, and prehistoric peoples), which they often viewed, through a biased lens, as more 'elemental,' 'instinctive,' and 'authentic.' They borrowed formal elements like abstraction and simplification, though often without understanding the original context and sometimes reinforcing stereotypes. It's a term now widely seen as problematic.

Q2: Which Modern artists were most influenced by non-Western art?

- A: Key figures include Pablo Picasso (African masks, Iberian sculpture), Henri Matisse (African sculpture, Islamic textiles), Paul Gauguin (Oceanic art, Japanese prints), Vincent van Gogh (Japanese prints), Amedeo Modigliani (African masks), Constantin Brancusi (African, Oceanic, folk art), and the German Expressionists (African and Oceanic art).

Q3: What is Japonisme?

- A: Japonisme was a French term coined in the late 19th century to describe the craze for Japanese art and design in the West following Japan's opening to international trade. It heavily influenced Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Art Nouveau through elements like flattened perspective, bold outlines, and asymmetrical compositions found in Ukiyo-e prints.

Q4: Was the use of non-Western art by Modernists cultural appropriation?

- A: It's complex and often debated. By today's standards, much of it would be considered appropriation. Artists often took forms without understanding or respecting their original meaning, operating within a colonial power dynamic where the exchange wasn't equal. However, it also led to significant artistic innovation. It's a legacy we're still grappling with, and one that contemporary artists from source cultures are actively addressing.

Q5: How did non-Western art influence Cubism?

- A: African sculpture, particularly masks, and ancient Iberian sculpture were crucial influences on the development of Cubism. Artists like Picasso were struck by their geometric simplification of forms, fragmented perspectives, and conceptual approach to representation (showing not just what is seen, but what is known about an object), which directly fed into Cubism's break from naturalism.

Q6: Did other non-Western traditions influence Modernism?

- A: Yes, while African and Japanese art were perhaps the most prominent influences in early Modernism, traditions like Islamic art (geometric patterns, calligraphy), Indian miniatures (color, narrative), and Pre-Columbian art from the Americas also fascinated some Western artists and contributed to the broader shift away from purely Western academic traditions.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Dialogue

The story of Modernism is incomplete without acknowledging the vital spark provided by art from Africa, Asia, and Oceania. It wasn't a simple case of 'inspiration'; it was a complex, sometimes fraught, interaction that nonetheless revolutionized Western art.

It forced artists (and viewers) to question their assumptions about what art could be, breaking open possibilities for abstraction, expression, and new ways of seeing. Recognizing this history allows us to appreciate the resulting art – from Picasso's jagged forms to Van Gogh's vibrant lines – with a deeper understanding of the global currents that shaped it. It reminds us that finding inspiration often means looking beyond the familiar, even if the journey is complicated. It's a dialogue that continues, hopefully with more awareness and respect for the incredible richness of art traditions worldwide.