Impressionism: An Artist's Guide to Light, Moment & Revolution

Dive into Impressionism with an artist's personal guide. Explore Monet, Renoir, Degas, key techniques like en plein air, and the movement's lasting impact on art history and how we see the world.

Impressionism: Your Ultimate Guide to the Art of Light & Moment (Through an Artist's Eyes)

Have you ever tried to capture a feeling? That split second when the light hits just right, or the blur of movement as someone rushes past? It’s tough, right? Often, by the time you grab your phone or even just fully register it, the moment’s gone. Vanished. That fleeting, almost intangible quality of a moment is, in many ways, the heart of Impressionism. It's something I think about constantly in my own work – how do you bottle that feeling, that specific light, that energy, before it evaporates?

It's easy to dismiss Impressionist paintings as just 'blurry' or 'pretty landscapes,' maybe something nice your grandma would hang up. And sure, they can be pretty. But dive a little deeper, and you find a revolution – a radical break from centuries of tradition, driven by artists determined to paint what they saw, how they saw it, in that very instant. This isn't just about haystacks and water lilies; it's about a whole new way of seeing the world and capturing its vibrant, messy, beautiful reality. Stick around, and let's explore why this art movement still feels so fresh and alive today. This is your ultimate guide to understanding, appreciating, and maybe even falling in love with Impressionism, seen through the lens of someone who spends their days wrestling with paint and light.

What Exactly Is Impressionism? Beyond the Blurry Edges

So, what ties all these paintings of dancers, landscapes, and Parisian cafés together? At its core, Impressionism was about capturing the impression of a scene, rather than a detailed, realistic rendering. Think of it like a quick glance rather than a long stare. The artists were fascinated by light and color, and how they changed constantly. They wanted to paint the feeling of a moment, the atmosphere, the way sunlight danced on water or filtered through leaves.

This was a big deal back in the mid-19th century. The art world was dominated by the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, which favoured highly polished, historically themed, or mythological paintings. Think smooth surfaces, clear lines, and 'important' subjects – gods, heroes, grand historical events. The Impressionists, with their visible brushstrokes, everyday subjects, and focus on fleeting effects, were rebels. They dared to suggest that a stack of hay or a busy street corner was just as worthy a subject as a scene from ancient mythology. Honestly, good for them. Breaking those rigid rules is often where the most exciting art happens.

The name itself actually came from a critique. When Claude Monet exhibited a painting called "Impression, soleil levant" (Impression, Sunrise) in 1874, the critic Louis Leroy mockingly used the term "Impressionists" to describe Monet and his circle. He meant it as an insult, suggesting their work was unfinished, mere sketches. But, like rebels often do, the artists embraced the name, and it stuck. Sometimes, the best names come from your detractors, don't they? It's a good reminder that not everyone will 'get' what you're doing at first.

![]()

The Birth of a Revolution: Context & Origins

Impressionism didn't just pop up out of nowhere. It was brewed in the specific conditions of mid-to-late 19th century France, a period of rapid change and innovation. Paris was undergoing massive changes under Baron Haussmann, with wide boulevards replacing medieval streets – creating new cityscapes to paint and new ways for people to interact and be observed. Before Haussmann, Paris was a maze of narrow, often dark and unsanitary streets. The new, open spaces, cafes, and parks became prime subject matter for artists capturing modern life.

Photography was emerging, challenging painting's traditional role as the primary way to record reality. This freed painters to explore other aspects of vision and experience. Photography also influenced compositional ideas, leading to the Impressionists' use of cropping and unusual angles, much like a snapshot.

Crucially, pre-mixed paints became available in tubes. This sounds minor, but it was huge! Before this, artists had to grind their own pigments, a time-consuming process that tied them to the studio. Tubes meant portability. Suddenly, artists could easily pack up their supplies and head outdoors to paint directly from nature, or en plein air, as the French say. This was fundamental to capturing the changing light they were so obsessed with. Imagine the freedom! Though, as we'll see, it wasn't without its challenges.

Artistically, they were influenced by the Realism movement (think Courbet), which focused on depicting ordinary life and working-class subjects, a departure from academic ideals. They also drew inspiration from the Barbizon School painters, who emphasized landscape painting outdoors. Impressionism built on Realism's subject matter and the Barbizon School's outdoor practice but diverged by focusing less on precise depiction and more on the subjective sensory experience of light and color.

A key moment that highlighted the growing dissatisfaction with the academic system was the Salon des Refusés ("Exhibition of Rejects") in 1863. So many artists were rejected by the official Salon that year that Emperor Napoleon III allowed them to hold their own exhibition. It caused a scandal but gave artists like Manet (a crucial precursor to Impressionism, whose modern subjects and style shocked the establishment) wider exposure and signaled a growing desire for artistic independence. You can find more about these shifts in the broader history of art.

Key Characteristics: How to Spot an Impressionist Painting (Even if You're Just Pretending)

Alright, let's get practical. How do you recognize an Impressionist painting when you see one? Here are the key ingredients, the visual language they spoke:

- Visible Brushwork: Forget smooth, blended surfaces. Impressionists used short, thick, broken strokes of paint. They wanted to capture the energy and immediacy of the moment, and the texture of the paint itself became part of the experience. Sometimes it feels like you can almost see the artist's hand moving quickly across the canvas, trying to keep up with the light. Look closely at a Monet haystack painting – the surface is alive with texture.

- Emphasis on Light (Luminism): This is paramount. They studied how light affects color and form at different times of day and in different weather conditions. Shadows weren't just black or grey; they were filled with reflected color. Monet's series paintings (like his Haystacks or Rouen Cathedral series) are prime examples of this obsession with capturing specific light effects – painting the same subject repeatedly to observe how light transformed it.

- Vibrant Color Palette: They often applied complementary colors side-by-side directly onto the canvas, letting the viewer's eye "mix" them (optical mixing). This created more vibrant, shimmering effects than mixing on a palette. They largely avoided using black paint, preferring to mix dark tones from other colors, believing pure black didn't exist in nature's light-filled world. This love for bold, unmixed color carries through into later movements like Fauvism.

- Everyday Subject Matter: No more gods, heroes, or grand historical events (mostly). Impressionists painted modern life: bustling city streets, cafés, dancers rehearsing, racetracks, picnics in the park, quiet domestic scenes, and landscapes. They found beauty and interest in the ordinary world around them. Renoir's paintings of people enjoying leisure time, like Bal du moulin de la Galette, or Degas' depictions of dancers backstage, are perfect examples.

- Unconventional Compositions: Influenced by photography and Japanese prints (Japonisme), which were becoming popular in Paris, Impressionists often used asymmetrical compositions, cropped figures at the edges of the canvas, and unusual viewpoints (looking down from above, for example). It often feels like a snapshot, a captured moment rather than a formally arranged, balanced scene. Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas were particularly influenced by the bold outlines, flat areas of color, and unique perspectives found in Japanese prints.

- En Plein Air Painting: As mentioned, painting outdoors was central. This allowed them to directly observe and capture the fleeting effects of natural light and atmosphere. You can almost feel the breeze or the warmth of the sun in some of these landscapes. This practice directly led to the visible brushwork and focus on light.

The Masters of the Moment: Key Impressionist Artists

While they shared common goals, each Impressionist had their own distinct style and focus. Let's meet some of the key players who defined this era:

Claude Monet (1840-1926): The Father Figure

Often considered the quintessential Impressionist. Monet was relentless in his pursuit of capturing light and atmosphere, most famously in his series of Haystacks, Poplars, Rouen Cathedral, and his beloved Water Lilies painted in his garden at Giverny. His "Impression, Sunrise" gave the movement its name. He stuck with Impressionist principles his entire career, constantly exploring how light transformed the world around him. Seeing his series paintings together is a masterclass in observation.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917): Dancers, Racehorses, and Modern Life

Degas stood slightly apart. While he exhibited with the Impressionists, he preferred to call himself a "Realist" or "Independent." He was less interested in en plein air landscape painting and more focused on scenes of modern Parisian life – ballet dancers (The Ballet Class), cafés, racetracks, laundresses. He was a master draftsman, emphasizing line more than some of the others, and known for his innovative compositions and viewpoints, often influenced by photography and Japanese prints. His cropped figures and unusual angles give his work a dynamic, almost voyeuristic feel.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919): Joyful Scenes and Soft Figures

Renoir is known for his vibrant, light-filled paintings depicting people enjoying life – dancing (Bal du moulin de la Galette), boating, socializing. His figures often have a soft, sensual quality, and his brushwork can be feathery and delicate, capturing the warmth and pleasure of human interaction. While his early work is purely Impressionist, he later moved towards a more classical style with clearer forms, but his love for light and color remained.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903): The Mentor and the Landscape

A key figure and mentor to many younger artists (including Cézanne and Gauguin). Pissarro was the only artist to exhibit in all eight Impressionist exhibitions. He primarily painted landscapes and rural scenes, often exploring different techniques, including a period working with the Pointillist style (check out our guide to Pointillism for more on that). His work provides a consistent thread through the movement's evolution.

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) & Mary Cassatt (1844-1926): Leading Women Impressionists

These two women were central figures in the movement, overcoming significant societal barriers to become respected artists. Morisot (Manet's sister-in-law) created intimate scenes, often featuring women and children in domestic settings or gardens (The Cradle), with a delicate, feathery brushstroke that perfectly captured light and atmosphere. Cassatt, an American living in Paris, was known for her portraits and depictions of the private lives of women, particularly mothers and children (The Child's Bath), often influenced by Japanese prints in her compositions and use of line.

Alfred Sisley (1839-1899): The Dedicated Landscapist

Born in Paris to British parents, Sisley remained perhaps the most consistent landscape painter among the core Impressionists. His work focuses almost exclusively on capturing the atmosphere and light of the Île-de-France region near Paris, often featuring rivers and subtle weather effects. His dedication to landscape painting en plein air is evident in the freshness and immediacy of his canvases.

Other Notable Figures:

Édouard Manet (1832-1883) also deserves mention. Though he never exhibited with the core Impressionists, his paintings like Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia were hugely influential with their modern subject matter and flatter painting style, breaking sharply from academic tradition and inspiring the younger generation. He was a pivotal link between Realism and Impressionism.

Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894) was another important figure, known for his depictions of urban Paris, often using unique, elevated perspectives and a more realistic style than some of his peers, as seen in his famous Paris Street; Rainy Day. He was also a crucial patron and organizer of the Impressionist exhibitions.

Frédéric Bazille (1841-1870) was an early member of the group, painting figures in landscapes with a strong sense of light and color before his untimely death in the Franco-Prussian War. His work shows the early promise of the movement.

Beyond the Canvas: The Experience of Impressionist Techniques

We've touched on some techniques, but let's look closer at what it was like to work this way, and what it means for us looking at the art today.

- En Plein Air: Imagine setting up your easel in a field, battling wind, insects, curious onlookers, and the constantly changing light. Painting outdoors forced artists to work quickly to capture the fleeting moment before the sun shifted or clouds rolled in. This speed contributed to the characteristic loose brushwork and sense of immediacy. It sounds romantic, and it can be, but practically speaking, it was often a race against time, a battle against the elements. I sometimes feel that pressure even in the studio when a particular mood strikes – you have to get it down before it evaporates, but at least I don't have bugs landing in my paint! They often used smaller canvases outdoors for portability, reserving larger works for the studio, sometimes based on outdoor sketches.

- Optical Mixing: Instead of carefully blending blue and yellow on a palette to make green, an Impressionist might place small dabs of blue and yellow next to each other on the canvas. From a distance, your eye naturally blends these dabs, perceiving them as green. This technique aimed to create brighter, more luminous colors that vibrated with light, capturing the intensity of natural light in a way traditional blending couldn't. It's like their canvases shimmered.

- Capturing Transience: How do you paint wind, or the momentary reflection on water, or the blur of a passing train? Impressionists used broken color, dynamic brushstrokes, and sometimes less defined forms to convey movement and the ephemeral quality of their subjects. They weren't painting the thing itself as much as the experience of seeing the thing in a specific moment.

- The Impact of Photography: The snapshot aesthetic influenced Impressionism. Cropped figures at the edge of the frame, unusual angles, and a sense of capturing a slice of life can be seen as parallels to early photography. It wasn't about competing with photography, which could capture detail perfectly, but perhaps learning from its way of seeing – focusing on composition and the immediate visual impact rather than just documentation. You can explore different ways of reading a painting to better understand these compositional choices.

- Materials: Beyond the tubes, they often used commercially prepared canvases, which were more readily available. While they experimented with pigments, their focus was less on the chemical properties and more on the visual effect of color interaction and light.

Critical Reception: From Mockery to Mainstream

As we know, the initial reaction to Impressionism was not exactly glowing. Louis Leroy's famous review was just one example of the widespread mockery and disdain from the art establishment and many critics. Their work was seen as unfinished, sloppy, and lacking the seriousness and technical skill of academic painting. The visible brushstrokes, the 'everyday' subjects, the focus on fleeting moments rather than timeless narratives – it all flew in the face of centuries of tradition.

However, the Impressionists continued to exhibit together (holding eight independent exhibitions between 1874 and 1886), building their own audience and collectors. Figures like art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel were crucial in supporting and promoting their work, particularly in the United States and Britain, where reception was sometimes warmer than in France. Over time, as viewers became more accustomed to their style and the radical nature of their approach became clearer, critical opinion began to shift. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Impressionism was not only accepted but highly popular and influential, fetching high prices and entering major museum collections. It's a classic story of artistic innovation initially being rejected before becoming the new standard.

Impressionism's Legacy: How a Fleeting Moment Changed Art Forever

Impressionism might have seemed radical and unfinished to contemporary critics, but its impact was profound and lasting. It fundamentally shifted the focus of art from historical or mythical subjects to everyday life, and from objective representation to subjective perception. It opened the door for artists to explore personal vision and the act of seeing itself.

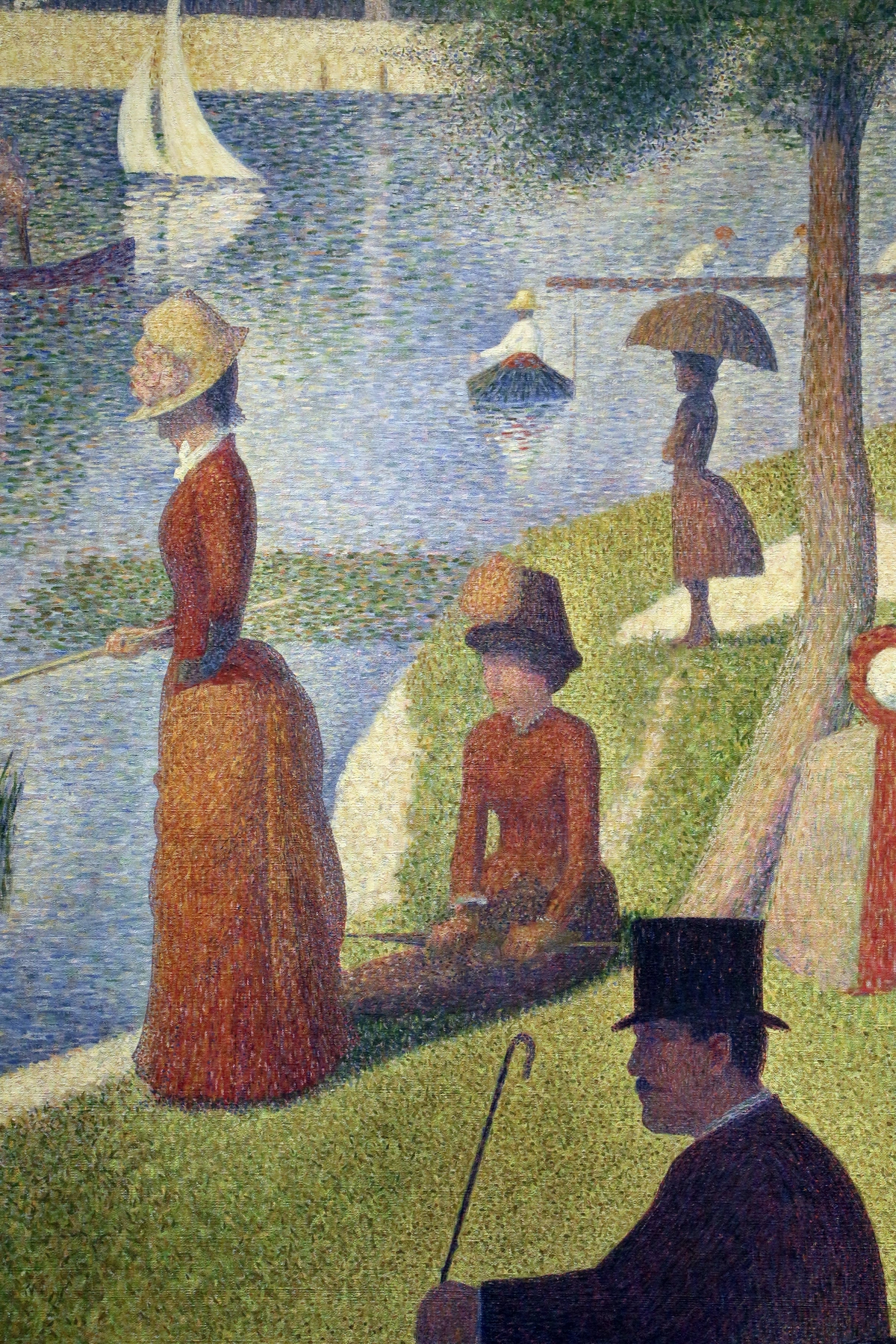

- Paving the Way for Post-Impressionism: Artists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Georges Seurat built upon Impressionism's foundations but pushed art in new directions. They explored emotion, structure, symbolism, and scientific color theory, leading directly to the revolutions of Modern Art. You can see Impressionism's DNA in movements like Fauvism (with its bold color) and even early Cubism (in its questioning of traditional perspective and form).

- A New Way of Seeing: Impressionism taught viewers (and artists) to appreciate the beauty in the everyday, the importance of light, and the validity of personal perception. It democratized subject matter and technique. It encouraged people to look at the world around them with fresh eyes.

- Influence on Other Mediums: While primarily a painting movement, its emphasis on capturing fleeting moments and subjective experience resonated. Sculptors like Auguste Rodin, for instance, were sometimes described as 'Impressionist' in how they captured movement and light on textured surfaces, leaving chisel marks visible.

- Enduring Popularity: Why do we still love Impressionism? Maybe it’s the accessible subjects, the vibrant colors, the feeling of light and air. Perhaps it connects to our own desire to hold onto fleeting moments. It feels human, relatable. Even in contemporary abstract art, like some of the pieces you might find for sale here, the lessons learned from the Impressionists about color, light, and capturing a feeling still resonate. My own artistic journey has certainly been informed by studying how these masters broke the rules and chased the light.

Visiting Impressionism: Where to See Masterpieces

Experiencing Impressionist paintings in person is truly the best way to appreciate their texture, color, and light. Many of the world's best museums have incredible collections:

- Musée d'Orsay (Paris): Housed in a stunning former railway station, this museum holds arguably the world's most important collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art. A must-visit if you're in Paris (check out other top Paris galleries too). Seeing the light stream through the station's windows onto the paintings feels particularly fitting.

- Musée Marmottan Monet (Paris): Home to the world's largest collection of works by Monet, including "Impression, Sunrise" and many of his later Water Lilies. A more intimate setting than the Orsay.

- The National Gallery (London): Features a strong collection, including works by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Degas, and Manet. See our guide to the best London galleries.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York): Boasts an extensive collection of European paintings, including many Impressionist masterpieces. Find more NYC spots in our NYC galleries guide.

- Art Institute of Chicago: Known for having one of the finest collections of Impressionist art outside of Paris, including major works by Monet, Renoir, and Caillebotte.

- National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.): Offers a significant collection, including the only Degas wax sculpture displayed during his lifetime. Explore more DC galleries here.

And of course, visiting Monet's Garden in Giverny, France, offers a unique chance to see the landscapes that inspired so many of his later works. Even seeing local art, like at the Zen Museum in Den Bosch, can be enriched by understanding the historical context provided by movements like Impressionism.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Got more questions buzzing around your head? Let's tackle a few common ones:

- What is the main goal of Impressionism? The main goal was to capture the fleeting impression of a moment, particularly the effects of light and color, rather than creating a detailed, realistic depiction. It focused on the artist's subjective perception of reality – how the world felt and looked in that instant.

- Why is it called Impressionism? It was initially a derogatory term coined by critic Louis Leroy after seeing Monet's painting "Impression, Sunrise" (1872). He meant to imply the work was unfinished, just an "impression." The artists, however, adopted the name, turning an insult into an identity.

- Who are the 3 most famous Impressionist painters? While fame is subjective, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas are often considered among the most famous and central figures of the movement.

- Is Van Gogh an Impressionist? No, Vincent van Gogh is generally classified as a Post-Impressionist. While deeply influenced by Impressionism (especially its color and brushwork), he used art to express intense emotion and personal vision, moving beyond the Impressionists' focus on objective optical perception. Learn more in our guide to Van Gogh.

- What came after Impressionism? Post-Impressionism immediately followed, with artists like Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, and Seurat extending Impressionism's ideas while exploring new directions (emotion, structure, symbolism). This paved the way for Fauvism, Cubism, and other Modern Art movements.

- Why don't Impressionist paintings look realistic? They weren't trying to look perfectly realistic in the traditional sense. Their goal was to capture the sensation or impression of a moment, including how light dissolves forms and how colors appear to the eye quickly. The visible brushwork, focus on light effects over detail, and subjective viewpoint contribute to their less-than-photographic appearance. It's a different kind of reality they were after – the reality of perception.

- What was the typical size of Impressionist paintings? While they painted works of various sizes, many of the paintings created en plein air were relatively small due to the practicalities of working outdoors and needing to capture fleeting light quickly. Larger works were often completed in the studio based on outdoor sketches and studies.

- Did Impressionists paint portraits? Yes, absolutely! While landscapes and scenes of modern life are perhaps most iconic, artists like Renoir, Degas, Cassatt, and Morisot painted many portraits, applying their characteristic techniques of visible brushwork, focus on light, and capturing the sitter's presence and atmosphere rather than just precise likeness.

Conclusion: More Than Just Pretty Pictures

So, Impressionism. It was more than just French painters obsessed with sunlight. It was a pivotal moment that blew open the doors of artistic possibility. By daring to paint their fleeting perceptions of the world around them, with all its light, movement, and everyday energy, they changed the course of art history.

They remind us that beauty isn't just in grand subjects but in the light on a puddle after rain, the bustle of a city street, a quiet moment at home. They showed us a new way to look, to appreciate the transient nature of experience. And maybe, just maybe, they encourage us to pay a little more attention to those fleeting moments in our own lives, even if we don't have paints and an easel ready to capture them. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the impression is everything. It's a lesson I try to carry into my own work every day – chasing that feeling, that light, that moment, and trying to translate it onto the canvas, or into a print you might hang on your wall.