Cubism: Shattering Reality, One Angle at a Time - Your Ultimate Guide

You know how sometimes you look at a piece of modern art, maybe something like Cubism art, and think, "Okay, what am I actually looking at here?" It feels… broken. Fragmented. Like someone dropped a perfectly good picture and glued the pieces back together slightly wrong. If that sounds familiar, especially when looking at a certain type of early 20th-century painting or even Cubist sculpture, then welcome! You've stumbled upon Cubism, and honestly, that initial confusion is totally valid. I remember the first time I saw a Braque still life – all those overlapping planes and muted browns – in a museum. My brain just went, "...Huh?" It felt less like looking at a painting and more like trying to solve a visual riddle I didn't have the key to. It was frustrating, sure, but also kind of thrilling once I leaned into the challenge, like finally seeing the hidden image in a Magic Eye poster after staring for ages. Or maybe you tried to sketch a simple object, like an apple, but felt like you were missing something, like the drawing only captured one fleeting moment from one spot. Cubism feels like it's trying to capture all those moments, all those angles, at once. It's a lot to take in!

It's easy to dismiss it as weird or even unskilled (though, trust me, the artists involved were anything but). But Cubism wasn't just about making things look strange for the sake of it. It was a revolution, a fundamental shift in how artists saw and represented the world. It's like they collectively decided the old rules of painting – the ones that had been around for centuries, focused on creating a perfect illusion of reality from one spot – just weren't cutting it anymore. They wanted to show something deeper, the underlying structure or the idea of an object, not just its surface appearance under specific lighting from one angle. And at the forefront of this visual earthquake? Two names you've almost certainly heard: Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. This movement didn't just change art; it changed how we see the world, permanently, and its echoes are still felt today, even in my own abstract art.

So, how did they do it? What were they really trying to achieve? And why does it still matter today? We'll explore its core ideas, meet the minds behind it, understand its different phases, and see why it changed everything – and maybe even how it can change how you look at the world.

What is Cubism, Really? The Big Idea

What if you could see all sides of something at once? At its heart, Cubism is about ditching the traditional idea of a single, fixed viewpoint. Think about how you experience an object in real life. You don't just see it from one static position, right? You walk around it, you see the front, the side, maybe a bit of the top, all in quick succession. Your brain pieces together this information to understand the whole object. Or think about trying to describe someone's personality – you can't capture it from just one interaction; you need to see them in different situations, from different angles, to get the full picture. Cubism tries to do that visually.

Cubist painters tried to capture this total experience on a flat canvas. Instead of painting a face from just the front, they might show you the profile and the front view simultaneously – a technique often called simultaneous perspective. Imagine watching a scene unfold through multiple camera angles all at once, or seeing a complex idea broken down into its core components and presented all at once. That's closer to the Cubist approach than a single photograph. It's a visual challenge, for sure, but also kind of liberating once you embrace the idea that reality isn't just one flat image.

They'd break down objects into geometric shapes – cubes, cones, cylinders (hence the name, possibly coined somewhat mockingly at first) – a process sometimes referred to as facetting. Think of it like cutting a gemstone to reveal its many surfaces, or seeing the underlying structure of an object, like an architectural blueprint or an X-ray, not just its surface skin. These facets, representing different angles and moments in time, were then reassembled, showing multiple perspectives at once. They were interested in the fundamental form.

Why do this? It wasn't just a stylistic quirk. It was a way to represent reality more completely, to show the idea and structure of an object, not just its surface appearance under specific lighting from one angle. They were challenging the illusion of depth that artists since the Renaissance had worked so hard to perfect. It sounds complicated, and visually it can be, but the core idea is about capturing a more dynamic, multi-faceted view of reality. Understanding what art is often means grappling with these shifts in perception.

Interestingly, the term "Cubism" itself wasn't meant as a compliment. It was first used dismissively by the French art critic Louis Vauxcelles in 1908, after seeing Georges Braque's landscapes painted at L'Estaque, like his Houses at L'Estaque. Braque had simplified the houses and trees into geometric forms, prompting Vauxcelles to describe them as reducing everything to "geometric schemas, to cubes." This initial, bewildered reaction from a prominent critic highlighted just how radical and challenging this new approach was to the established art world norms of the time. The name stuck, even if the artists didn't initially embrace it. This revolutionary approach, born from a desire to see beyond the surface, was about to shake the art world to its core.

The Birth of a Revolution: Paris, Precursors, Picasso, and Braque

Cubism didn't just pop up out of nowhere. It emerged in the vibrant, experimental atmosphere of early 20th-century Paris, a melting pot of artistic innovation. Artists were already pushing boundaries – think of the bold colours of Fauvism, championed by artists like Henri Matisse. Beyond painting, the revolutionary spirit of the age was also influencing other art forms like poetry (think Guillaume Apollinaire) and music (like Igor Stravinsky), exploring fragmentation and new structures. This was a time of rapid change, with industrialization, new technologies like photography and cinema, and scientific discoveries challenging traditional ways of seeing and understanding the world. It makes sense that artists, always sensitive to the pulse of their era, would seek new visual languages to match this shifting reality.

A crucial precursor, often called the "father of modern art," was Paul Cézanne. His later works, where he analyzed forms into geometric components and showed objects from slightly different viewpoints simultaneously, profoundly influenced Picasso and Braque. Cézanne's idea that all forms in nature could be reduced to the cylinder, sphere, and cone, and his exploration of flattened space, laid essential groundwork for the Cubist revolution. Look at a Cézanne landscape, like his views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, or his still lifes of apples and bowls – you see the forms broken into planes, the perspective feeling slightly off, as if he's showing you the object's form from several angles at once. This analytical approach to form was a direct inspiration for the early Cubists.

But the real catalyst came from the intense, almost symbiotic meeting of minds between the fiery Spaniard, Pablo Picasso, and the more reserved Frenchman, Georges Braque. Around 1907, they began an intense artistic dialogue, pushing each other's work in radical new directions. They worked side-by-side, visiting each other's studios daily, critiquing and inspiring one another. Braque famously said they were like "two mountaineers roped together." They were so close in style during this period that sometimes even experts have trouble telling their unsigned works apart. It was less a competition, more a shared exploration – a friendly rivalry fueled by mutual respect and a shared desire to dismantle artistic tradition. Can you imagine two artists working so closely, so intensely, that their styles almost merge? It's a fascinating thought, a kind of artistic mind-meld that feels incredibly rare.

A pivotal work often cited as Proto-Cubist (a crucial precursor, but not yet the fully developed style shared by Picasso and Braque) is Picasso's explosive Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907). Its fragmented figures, mask-like faces, and shattered sense of space shocked the art world and paved the way for true Cubism. I remember seeing a reproduction of it for the first time and just feeling... unsettled. It was raw, angular, and frankly, a bit terrifying. It didn't look like anything I'd been taught art should look like. The influence of African masks and Iberian sculpture on the distorted faces and angular bodies in Les Demoiselles is particularly striking – Picasso wasn't just copying forms, but drawing on the power and abstraction he saw in these non-Western objects to break away from traditional European representation, a fascinating example of the influence of non-western art on Modernism. While radical, Les Demoiselles still retained some traditional elements, like a sense of volume and depth in certain areas, which the later, more abstract Analytic Cubism would further dismantle. Braque saw it, was initially taken aback, but then incorporated similar ideas into his own landscapes, like those painted at L'Estaque, which, as we saw, earned the movement its name. It's important to remember Les Demoiselles was a stepping stone, a radical experiment that pointed the way, but the consistent, developed style we call Cubism came from their joint efforts that followed, starting around 1908.

Beyond painting, the Cubists were also influenced by the rapidly changing world around them. The advent of photography and early cinema, with their ability to capture multiple moments in time or different angles of a subject, subtly fed into the Cubist desire to represent a more complete, dynamic reality than traditional painting allowed. Photography, in particular, freed painting from its centuries-old task of simply documenting reality, allowing artists to explore new ways of seeing and representing the world.

And how was this radical new art received? Beyond Vauxcelles' initial quip, public and critical reactions were often bewildered, sometimes hostile. It challenged deeply ingrained ideas about beauty and representation. Many found it ugly, confusing, or even nonsensical. It wasn't an easy birth for the movement. But from this intense period of collaboration and radical experimentation, two distinct, yet related, phases of Cubism emerged.

The Two Flavours of Cubism: Analytic vs. Synthetic

Okay, so Cubism isn't just one monolithic style. It evolved, and art historians generally divide it into two main phases. It’s like learning levels in a game – first, you break things down, then you start building again. Let's look at the two main "flavours." Think of Synthetic Cubism as the artists taking the lessons learned from the intense deconstruction of Analytic Cubism and using that new visual language to build compositions back up, often in a clearer, more playful way. It's almost like they got restless after mastering the analysis and wanted to see what new visual structures they could synthesize from the fragments.

Phase 1: Analytic Cubism (Roughly 1908-1912)

Ready to see the world taken apart? This is the "breaking it down" phase. Think analysis. Picasso and Braque took objects – guitars, bottles, faces, landscapes – and meticulously dissected them into geometric facets. They looked at them from multiple viewpoints and then overlaid these views onto the canvas. This is where techniques like simultaneous perspective and facetting are most evident, creating complex, interlocking planes.

Imagine a simple object, like a guitar. Instead of painting it from the front, a traditional view, an Analytic Cubist might show you the curve of the body from the side, the fretboard from above, the soundhole from the front, and maybe even a glimpse of the back, all flattened and rearranged on the canvas. These different views are broken into smaller, angular planes or "facets," like shards of glass, and interlocked. It's not about creating a realistic picture, but about presenting a comprehensive visual report of the object's form and structure.

This phase also heavily utilized a technique called passage. This is where planes aren't sharply defined but blend into one another, blurring the distinction between object and space, allowing forms to flow across the canvas and further flattening the picture plane. Imagine the curve of a bottle's neck blending seamlessly into the background wall, making it hard to tell where the bottle ends and the space begins, almost like forms dissolving into smoke or merging like pools of water. It's a subtle but crucial element that adds to the complex, interwoven feel of Analytic Cubist works.

- Palette: Mostly muted colours – browns, greys, ochres. Colour wasn't the focus; form and structure were paramount. It was almost intellectual, analytical. It's like they stripped away the distraction of colour to focus purely on the architecture of vision. This limited palette actually helped emphasize the complex interplay of light and shadow across the fragmented planes, making the viewer focus on the form and structure rather than being seduced by vibrant hues. It forces your eye to work, to trace the lines and shapes and try to reconstruct the object in your mind. Painting with such a limited palette can feel stark, even mysterious, forcing you to find nuance in value and line rather than relying on the emotional punch of color. It's a real brain exercise! The primary medium was oil paint on canvas, applied with visible brushstrokes, which contributed to the textured, faceted look.

- Effect: Complex, dense compositions. Objects seem to merge with the background. It can be hard to decipher the subject matter sometimes – you have to hunt for clues. It's like looking at a reflection in a shattered mirror. Works like Picasso's Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910) or Braque's Violin and Candlestick (1910) are classic examples, challenging you to piece together the subject from a multitude of fractured planes and limited colour. In these works, you might see the front of a face blending into the side, or the neck of a violin dissolving into the background wall.

This phase required intense concentration, both from the artist and the viewer. I remember staring at a reproduction of a Braque Analytic Cubist piece once, feeling genuinely frustrated because I couldn't 'see' the object clearly. It felt like my brain was trying to assemble a 3D puzzle from 2D pieces that didn't quite fit. But then, slowly, fragments would emerge – a curve suggesting a bottle, lines hinting at a musical instrument. It's a different kind of looking, a more active engagement.

Phase 2: Synthetic Cubism (Roughly 1912-1919)

After intensely analyzing objects, Picasso and Braque (soon joined by others like Juan Gris) started to build images back up. Think synthesis. This phase is often seen as simpler and more direct, a response to the increasing abstraction and difficulty of Analytic Cubism. It felt like they had mastered the language of fragmentation and were now using it to construct new visual statements. It was a shift from deconstruction to reconstruction, using the fragmented language developed in the first phase to build something new and often more accessible.

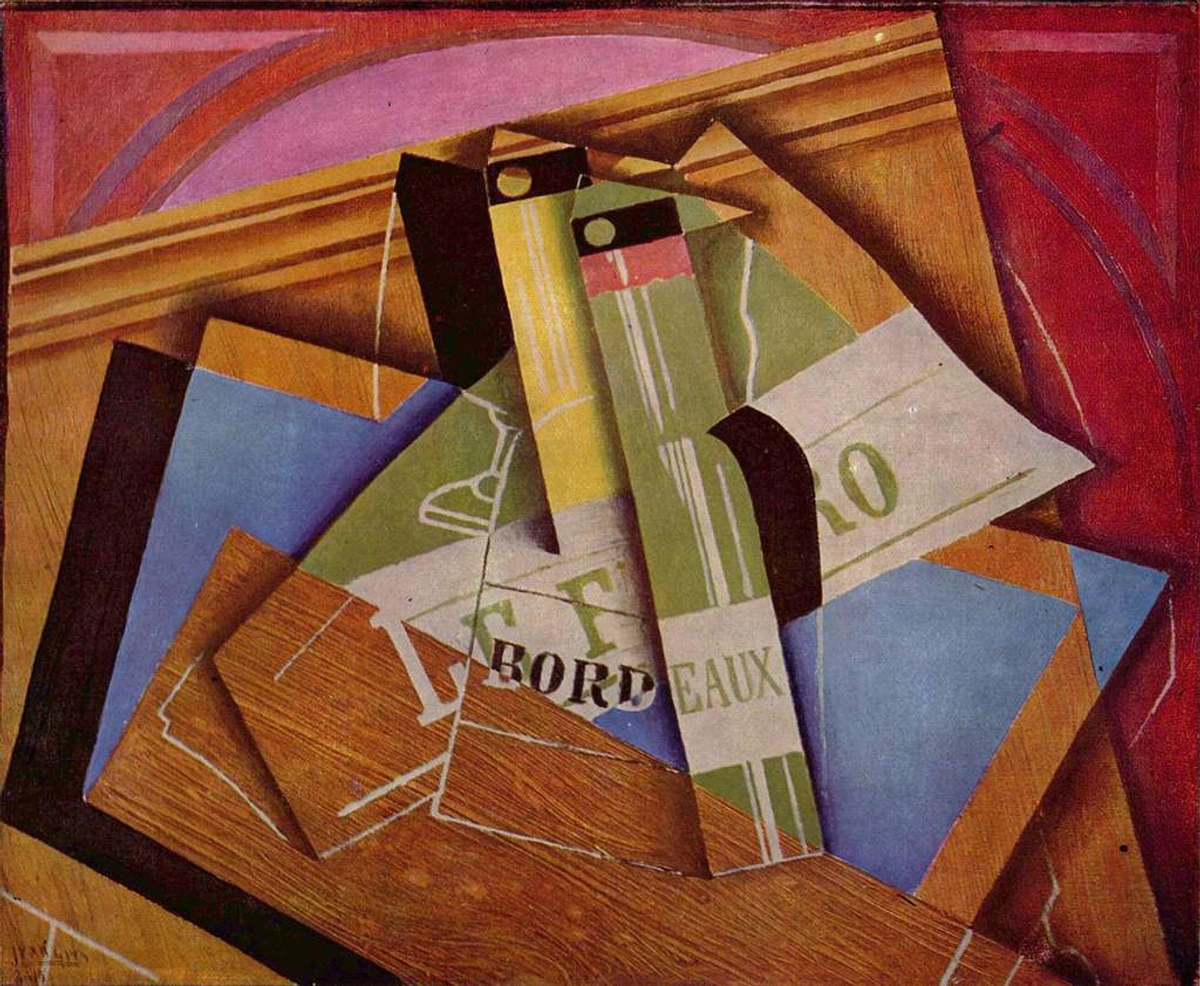

- Collage & Papier Collé: This is a key innovation. They started incorporating real-world materials directly onto the canvas – newspaper clippings, wallpaper, bits of labels (papier collé, or pasted paper). This wasn't just decorative; it played with ideas of reality and illusion. Is that real newspaper, or just painted? Is that printed text part of the artwork's subject, or is it actually printed text? They might use a piece of patterned oilcloth to represent a chair caning, or a scrap of newspaper to suggest a cafe table. Other materials could include fabric scraps, ticket stubs, or even sand or plaster for texture. These additions added new textures, patterns, and layers of meaning, blurring the boundary between art and reality in a playful, revolutionary way. There's something wonderfully playful, even rebellious, about sticking a piece of actual newspaper onto a canvas – it challenged the traditional hierarchy of art materials and blurred the lines between high art and everyday life. Picasso's Still Life with Chair Caning (1912), which includes a piece of oilcloth printed with a chair caning pattern, is considered the very first collage in fine art. It's a brilliant, playful trick that forces you to question what is 'real' within the painting.

- Colour: Brighter colours started to reappear, moving away from the strict monochromatic palette of the analytic phase. This made the works visually punchier and sometimes easier to read. While oil paint on canvas remained the base, the addition of collage elements introduced new visual and tactile dimensions.

- Forms: Shapes became larger, flatter, and more distinct, less fragmented than in Analytic Cubism. The compositions felt more constructed or "synthesized." You might still see multiple viewpoints, but the overall image is often easier to read.

- Subject: Still often focused on still lifes, but sometimes clearer and more playful.

Synthetic Cubism opened up new possibilities, directly leading to collage art as an accepted art form and pushing art further towards abstraction. It felt like a shift from deconstruction to reconstruction, using the fragmented language developed in the first phase to build something new and often more accessible.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 significantly impacted the movement. Many artists were called to serve, and the intense period of collaboration between Picasso and Braque ended. While Cubist ideas continued to evolve and spread, the war marked a turning point, leading to new artistic directions and a gradual decline in the movement's initial momentum by the end of the decade.

Beyond the Big Two: Who Else Was Shattering Reality?

While Picasso and Braque were undoubtedly the pioneers, did you know Cubism wasn't just a two-man show? Other artists made significant contributions and helped spread the movement. Exploring these figures is fascinating because it shows how the core Cubist ideas were interpreted and pushed in different directions, proving the style's versatility and impact.

Beyond the core duo, a crucial group were the Salon Cubists and the Section d'Or. These artists, including figures like Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, and Roger de La Fresnaye, were instrumental in bringing Cubism to a wider public audience by exhibiting works in the large, official Paris Salons. A "Salon" in this context was a major, often conservative, annual art exhibition, so showing Cubist works here was a bold, public statement. They also played a key role in theorizing the movement, publishing texts like Du Cubisme (1912) by Gleizes and Metzinger, which helped explain the ideas behind the style to a bewildered public and critical establishment. Their efforts helped solidify Cubism as a major force in the history of art.

Here are some other key figures who developed their own unique takes on Cubism:

- Juan Gris: Often considered the "third Musketeer" of Cubism, known for his more colourful, logical, and clearly structured Synthetic Cubist works. He brought a certain elegance and clarity to the style. For me, Gris's work often feels a bit more approachable than early Analytic Cubism; there's a sense of order and deliberate design even within the fragmentation. His Portrait of Pablo Picasso (1912) is a great example of applying the Cubist approach to portraiture with a distinct clarity.

- Fernand Léger: Developed a distinctive "Tubist" style, using cylindrical forms and bold colours to depict modern, machine-age subjects. Léger's work has a real sense of industrial energy, like the world is made of polished metal pipes and gears. His painting Nudes in the Forest (1909-10) shows this early exploration of cylindrical forms.

- Robert Delaunay & Sonia Delaunay: Developed Orphism (or Orphic Cubism), a more abstract and colourful offshoot focusing on pure form and colour interaction. Their work is less about breaking down objects and more about the dynamic interplay of colour and light – it's Cubism that wants to dance! Robert Delaunay's Simultaneous Contrasts (1912) is a prime example of this vibrant, abstract approach.

Cubist ideas also quickly influenced sculpture. Picasso himself began experimenting with constructing forms in three dimensions around 1909, creating pieces like Head of a Woman (Fernande). Other sculptors like Alexander Archipenko and Jacques Lipchitz also adopted Cubist principles, breaking down forms into geometric planes and exploring negative space, expanding the possibilities for sculpture beyond traditional carving or modeling and setting the stage for later developments in 3D art.

Looking at Cubism: Tips for Appreciation

So, how do you approach a Cubist painting without feeling completely lost? It's maybe less about immediate "understanding" and more about active looking. It can feel like a visual workout, but it's rewarding. Here's what I find helps when I'm faced with a Cubist work, especially after understanding the Analytic and Synthetic phases:

- Slow Down: My first tip, and maybe the hardest, is just to slow down. Don't expect to grasp it instantly. Spend time with the artwork. Let your eyes wander. It's okay if it feels like work at first – it's a new visual language! Think of it as learning to read a map that shows elevation, roads, and population density all on the same plane.

- Look for Clues: I find it helps to think of it like a visual treasure hunt. Try to identify fragments of recognizable objects – a guitar string, the curve of a bottle, an eye, letters from a newspaper. What familiar shapes or textures can you spot amidst the fragmentation? In Synthetic Cubism, look for actual pieces of paper or other materials!

- Embrace the Ambiguity: Accept that you might not be able to piece it all together perfectly. The fragmentation is part of the point. The artist isn't trying to hide the subject, but to show it in a new, more complex way. It's okay not to have a single, clear image pop out at you.

- Think About the Process: Imagine the artist analyzing the subject, breaking it down, showing different sides. What decisions did they make about which angles to show and how to arrange them? How did they use techniques like facetting or passage to connect different parts of the image? How did they build the image back up in Synthetic works?

- Consider the Composition: Look at how the fragmented shapes and planes relate to each other across the entire canvas. How do they create rhythm, balance, or tension? The overall arrangement is just as important as the individual pieces.

- Consider the Feeling: Even if the subject is hard to decipher, try to connect with the overall feeling or energy of the work. Is it dynamic? Stark? Playful? Cubism isn't purely intellectual; it has an emotional and dynamic quality too. The muted tones of Analytic Cubism can feel quite different from the brighter colours and textures of Synthetic works.

- Forget Realism: Judge it on its own terms, not by how accurately it depicts something. Focus on the composition, the shapes, the interplay of lines and planes. How do the forms relate to each other? How does the limited (or later, vibrant) colour affect the overall feeling? Learning how to read a painting involves adapting to different visual languages like this.

- Imagine You're the Artist: Try to put yourself in the artist's shoes. If you were trying to show everything about that object or person at once, how would you do it? What angles would you choose? How would you flatten and rearrange them? This can turn the viewing experience into a fascinating visual problem-solving exercise.

How Cubism Changed Art Forever: The Ripple Effect

Why should you care about Cubism today? It’s hard to overstate its impact. It wasn't just another art style; it fundamentally altered the course of Western art and beyond. It's like dropping a stone in a pond – the ripples just kept spreading.

- Shattered Tradition: It broke definitively with the realistic representation that had dominated art for centuries. By rejecting single-point perspective and fixed viewpoints, it freed artists from the obligation to simply mirror the visible world. It showed that art could be about form, line, and color in themselves, not just representations of things.

- Paved the Way for Abstraction: By breaking down objects and emphasizing form over realistic depiction, Cubism opened the door for purely abstract art. Movements like Futurism (which explored movement and dynamism through fragmented forms), Constructivism, Suprematism, and Vorticism owe a massive debt to Cubist innovations. Even artists like Marcel Duchamp, with works like Nude Descending a Staircase, explored the Cubist idea of representing movement and time through fragmented forms, pushing the boundaries in new directions.

![]()

- Influence on Design: Cubist principles of fragmentation, multiple viewpoints, and geometric forms didn't stay confined to painting and sculpture. They significantly influenced design fields across the board. Think of the dynamic, geometric sets of stage designers like Alexandra Exter, the way typography began to break down letters into geometric components, the bold compositions in graphic design and poster art of the era, and even the streamlined, geometric forms that led into architectural and decorative arts styles like Art Deco. It showed that this new way of seeing could be applied beyond the canvas, shaping the visual world around us in ways we still see today. Sometimes, its influence is so pervasive in modern visual culture – from graphic design to architecture – that we don't even notice its Cubist roots anymore. Understanding what is design in art often involves recognizing these historical shifts.

- Introduced Collage: Synthetic Cubism legitimized the use of non-traditional materials in fine art, directly leading to collage art becoming a major technique. I love thinking about the tactile nature of collage, the way real-world bits and pieces suddenly exist on the same plane as painted illusion. It's a simple idea with profound implications that artists still explore today.

- Influence on Sculpture: As mentioned earlier, Cubist ideas profoundly impacted sculpture, moving beyond traditional methods to embrace construction and fragmentation, influencing artists like Alexander Archipenko and Jacques Lipchitz.

- Influence Beyond Visual Arts: While primarily a visual art movement, Cubism's revolutionary spirit and exploration of fragmentation and multiple perspectives echoed in other fields. Think of the fragmented narratives in literature by writers like Guillaume Apollinaire or the rhythmic complexities and dissonances in music by composers like Igor Stravinsky. It was part of a broader cultural shift towards modernism.

- Enduring Influence: Its ideas about fragmentation, multiple perspectives, and geometric form continue to echo in contemporary art today. Artists still grapple with the questions Cubism raised about how we see and represent the world. For me, as an artist, the Cubist challenge to traditional perspective and its embrace of fragmentation are constant reminders to look beyond the obvious and to build compositions in unexpected ways. It makes you wonder what makes abstract art compelling, doesn't it? It's part of the long timeline of art influencing art.

(Above: Picasso's "Guernica" (1937) shows the enduring influence of Cubist fragmentation long after the main movement ended. Picasso used these Cubist-derived techniques of fragmentation and distorted forms to convey the horror and chaos of war with powerful emotional impact, making the visual chaos mirror the real-world suffering.) You can find more about key figures in modern art in our dedicated guide.

Key Characteristics Summarized

After diving deep, let's boil it down. What are the defining features to look for in a Cubism painting? This table offers a quick reference guide:

Feature | Description | Primarily Seen In | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject Matter | Common subjects include still lifes (especially musical instruments, bottles, newspapers), portraits, and landscapes. | Both Phases | Artists often chose everyday objects or familiar subjects to focus the viewer's attention on the revolutionary way of seeing, rather than the subject itself. Forms became clearer in Synthetic Cubism. |

| Multiple Viewpoints | Showing an object from several angles simultaneously on a flat surface (Simultaneous Perspective). | Both Phases | Instead of one static perspective, you see fragments from the front, side, top, etc., all at once, mimicking how your brain processes information in reality. |

| Geometric Shapes | Breaking down objects into basic forms like cubes, cones, spheres, cylinders (Facetting). | Both Phases | Objects are simplified and reduced to their underlying geometric structure, moving away from realistic rendering. |

| Fragmentation | The subject is fractured into pieces, visually shattering its form. | Analytic (more intense) | Objects are broken into small, overlapping planes, making them appear shattered or faceted. |

| Flattened Space | Rejecting traditional perspective; background and foreground often merge or interpenetrate. | Both Phases | The illusion of deep space is minimized, pushing forms forward onto the picture plane and blurring the distinction between subject and environment. |

| Monochromatic Palette | Use of limited, often muted colors (browns, greys, ochres) to focus on form. | Analytic | Colour is suppressed to emphasize the analysis of form and structure, preventing it from distracting from the complex composition. |

| Brighter Color & Collage | Introduction of vibrant colors and real-world materials (newspaper, wallpaper) onto the canvas. | Synthetic | Colour returns and actual materials are incorporated, adding new textures, patterns, and layers of meaning, playing with the boundary between art and reality. |

| Passage | Technique where planes blend into one another, blurring distinctions between object and space/background, allowing forms to flow into the space. | Both Phases | Edges between forms and the surrounding space are left open, creating a sense of continuity and further flattening the picture plane. Think of forms dissolving into smoke or merging like pools of water. |

Cubism FAQ: Quick Answers

- What is the main idea of Cubism? To depict subjects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously on a flat canvas, breaking them into geometric forms to represent a more complete idea of the object/person.

- Who were the main Cubist artists? Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were the pioneers. Juan Gris is also a major figure, followed by artists like Fernand Léger and the Delaunays (Orphism). The Salon Cubists also played a key role in exhibiting and theorizing the movement.

- What are the two types of Cubism? Analytic Cubism (c. 1908-1912), focused on deconstruction and a muted palette, and Synthetic Cubism (c. 1912-1919), characterized by collage, brighter colours, and simpler forms.

- Why is Cubism important? It revolutionized Western art by abandoning traditional perspective, introducing multiple viewpoints, paving the way for abstraction, legitimizing collage, and influencing design and sculpture. Its impact on how we see and represent reality is profound.

- Is Picasso the only Cubist artist? No! While he's the most famous and a key originator (along with Braque), many other artists contributed significantly to the movement and its variations. Check out our guide to Picasso for more on him specifically.

- Was Cubism only about painting? No, while painting was central, Cubist ideas also influenced sculpture, collage, graphic design, architecture, literature, and music.

- Where can I see Cubist art? Major museums with strong modern art collections worldwide will have Cubist works. Look for museums like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Tate Modern in London, or the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid (home to Picasso's Guernica). Many other large institutions also hold significant pieces. You can explore some of the best museums and best galleries in the world in our guides.

Conclusion: The World Reassembled

Cubism might seem like a puzzle initially, maybe even a frustrating one. I get it. Sometimes looking at art feels like work, and who needs more of that? But it's a puzzle worth engaging with. It marks a moment when artists fundamentally questioned how we see and challenged centuries of visual tradition. Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Juan Gris, and others didn't just paint objects; they dissected reality itself and put it back together in a way that forced viewers to look, really look, and think. They shattered the window onto the world that Renaissance artists had created and invited us to step inside the fragmented, multi-dimensional experience of seeing.

Understanding Cubism isn't just about ticking a box in art history; it's about appreciating a radical shift in human perception captured on canvas. It’s a reminder that there's always more than one way to see things – a lesson that feels pretty relevant, even today, in our complex, multi-faceted modern world where we're constantly bombarded with different perspectives and fragmented information. It certainly informs how many contemporary artists, myself included, think about form and space, even if the end result looks quite different from a 1910 Braque. It’s part of the long timeline of art influencing art. Maybe it even influences the way I approach creating pieces you might find in my art for sale collection, always looking for new angles. For instance, when I'm working on an abstract piece, I often think about how to layer shapes and colours to suggest depth or movement without relying on traditional perspective, a direct echo of Cubist principles. It's like taking the Cubist idea of showing multiple facets and applying it to pure form and color, building up a sense of space and energy from fragmented elements.

For me, as an artist, Cubism is a powerful reminder that the rules are meant to be broken, or at least bent and reshaped. It encourages me to look beyond the obvious, to consider multiple angles, and to not be afraid of fragmentation or abstraction in my own work. Maybe next time you're in a museum – perhaps even exploring the works at the Zen Museum in Den Bosch – you'll see the echoes of those fragmented perspectives in unexpected places, and the visual riddle won't feel quite so baffling anymore. Cubism didn't just change art; it changed how we see the world, permanently.