Modern Artists: An Artist's Personal Guide to the Revolution (1860s-1970s)

As an artist, I dive into the world of Modern Artists (c. 1860s-1970s). Explore the revolutionary break from tradition, key movements, iconic works, and how this era fundamentally shaped art today, through my personal, often quirky, lens.

Modern Artists: The Ultimate Guide to Key Figures & Movements (c. 1860s-1970s) - An Artist's Perspective

Okay, let's talk about "Modern Artists." For me, as someone who spends their days wrestling with paint and ideas, looking back at this era feels less like a history lesson and more like studying the foundations of the very language I speak. This wasn't just a shift; it was a seismic upheaval, a revolutionary group of creators who fundamentally reshaped the landscape of Western art and, honestly, paved the way for everything I do now. Spanning roughly from the 1860s to the 1970s, this period, often called Modern Art, was defined by a radical break from tradition and an unprecedented spirit of innovation and experimentation. Artists challenged established norms, explored new ways of seeing the world, experimented with form, color, and materials, and responded to the dramatic social, technological, and philosophical shifts of their time. It's like they collectively decided, "You know what? Let's just throw the rulebook out the window and see what happens." And boy, did things happen.

I remember the first time I saw a Rothko in person. It wasn't just a painting; it was an experience. The colors seemed to hum, to envelop me, and it hit me – this is what they meant by pushing boundaries, by seeking something beyond mere representation. Understanding the key figures and movements associated with modern artists isn't just essential to grasping the trajectory of art history; it's essential to understanding the DNA of contemporary art. It's appreciating the wild, messy, brilliant experiments upon which my own practice, and so many others, are built. This ultimate guide provides a comprehensive overview of influential modern artists, grouping them within their significant movements, exploring their characteristics, and highlighting their enduring impact. Think of it as my personal tour through the minds that blew art wide open.

Defining "Modern Artists": A Necessary Break with the Past

So, what exactly separates a "Modern Artist" from, say, someone painting portraits in the 17th century? It's more than just a date on the calendar. It's a mindset, a rebellion, a whole new way of engaging with the world and the canvas.

- Rejection of Tradition: This is huge. Modern artists deliberately moved away from the strict rules of academic art, particularly the powerful Salon system that dictated taste and prioritized historical subjects, realistic representation, and idealized forms. Artists like Courbet and the Impressionists famously bypassed or were rejected by the Salon system, deciding to show their work on their own terms. It was a declaration of independence, a refusal to play by the old rules.

- Emphasis on Innovation: Originality wasn't just a bonus; it was the point. Value was placed on experimentation, pushing artistic boundaries, and finding entirely new visual languages. It's the artistic equivalent of constantly asking, "What if?" and then actually trying it.

- Changing Role of the Artist: The artist wasn't just a skilled craftsman or someone working for wealthy patrons or the church anymore. They became independent innovators, social commentators, philosophers with paintbrushes, and explorers of the inner world. Their personal vision became paramount, shifting the focus from what was depicted to how and why.

- Focus on Formal Elements: There was increased attention paid to the intrinsic qualities of art itself – color, line, shape, texture, composition – sometimes even over realistic depiction. This is where things get really interesting for me. Understanding how to read a painting shifted dramatically because the 'story' wasn't always the main thing; sometimes, the how was the story. The rise of photography also played a role here; with cameras handling realistic depiction, painters were freed up to explore other aspects of vision, emotion, and form. Photography itself also emerged as a significant modern art medium during this period, with pioneers exploring its unique expressive potential.

- Subjectivity and Expression: Art became a powerful vehicle for personal expression, emotion, and individual perception. It wasn't just about showing the world as it is but showing the world as I feel it or as I see it through my unique filter. This emphasis on the artist's inner state was a radical departure.

- Engagement with Modern Life: Artists weren't hiding in ivory towers. They responded to the changing world around them – urbanization, industrialization, new technologies, the trauma of world wars, the revelations of psychoanalysis. Modern life, in all its messy glory, became valid subject matter, depicted with honesty and often raw emotion.

- Time Period: Generally, the Modern Art period stretches from the mid-to-late 19th century (Impressionism) up to the 1960s or 1970s (Pop Art, Minimalism, Conceptual Art marking transitions towards the contemporary). It's a long, wild ride!

It's important to distinguish Modern Artists from Contemporary Artists, who generally emerged after the 1970s and continue to work today, often building upon or reacting against Modernist principles. (See also: Top Living Artists Today). Contemporary art is the house built on the modernist foundation, often with some seriously weird extensions.

The Dawn of Modernism: Breaking with Tradition (Late 19th Century)

Alright, diving into the 'who's who' of modern art can feel like tumbling down a rabbit hole of isms and manifestos. But getting to know the key players is where the real fun begins. The seeds of Modernism were sown by artists challenging the status quo in the latter half of the 19th century, pushing back against the rigid academic system. Let's meet some of the revolutionaries who decided the old ways just weren't cutting it anymore.

From Realism to Impressionism

This was the initial crack in the academic facade, focusing on depicting ordinary life and the fleeting moment.

- Gustave Courbet: A key Realist painter who rejected idealized subjects in favor of depicting ordinary life and laborers. He really kicked the door open, insisting art should show the real world, warts and all. His painting The Stone Breakers (sadly destroyed in WWII) was a stark, unsentimental look at manual labor, a subject previously deemed unworthy of grand painting.

- Édouard Manet: A pivotal figure bridging Realism and Impressionism, whose works like Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia shocked the establishment with their modern subject matter (nudes who weren't goddesses!) and flatter, more direct style. Manet was less about fluffy technique and more about capturing the unsettling coolness of modern encounters. He painted modern Paris, its cafes, its people, with a cool, detached eye that felt utterly new.

- Impressionism: Focused on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, often painting en plein air (outdoors) to directly observe the changing conditions. They embraced modern life as subject matter – cityscapes, leisure activities, portraits of ordinary people. Their core idea? Capture the impression of a moment, not just the detailed reality.

- Key Artists:

- Claude Monet: Famous for his studies of light, especially in series paintings like Water Lilies or Haystacks. Monet, for instance, wasn't just painting haystacks; he was chasing light itself, almost obsessively, something you feel when you see those series paintings. His painting Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise) gave the movement its name, initially as a term of derision. I mean, who names a whole movement after a blurry sunrise? These guys, that's who.

![]()

- Edgar Degas: Known for his dynamic compositions of dancers, horse races, and intimate moments of modern Parisian life. He had such an eye for the unguarded moment, the awkward grace. His ballet dancers, often shown backstage or rehearsing, feel incredibly real, capturing the effort behind the glamour.

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Celebrated for his joyful scenes, particularly sensuous figures and bustling social gatherings. Renoir just seemed to love painting life's pleasures, like the vibrant, sun-dappled crowd in Bal du moulin de la Galette.

- Berthe Morisot: A central figure whose delicate yet bold brushwork captured domestic scenes and the lives of women with a unique sensitivity often overlooked back then. She was truly painting her modern life, often from a perspective the male artists didn't have access to, like the quiet intimacy of The Cradle.

- Camille Pissarro: A mentor figure to many, known for his rural and urban landscapes, experimenting across Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist styles. Pissarro was like the wise elder of the group, always experimenting, always pushing.

Post-Impressionism: Diverse Reactions

Building on Impressionism but seeking more substance, structure, or emotional depth. This wasn't a unified movement but a collection of distinct styles – think of it as Impressionism's rebellious kids, each going their own way, often working in relative isolation or small, intense groups rather than a cohesive movement. Their core idea? Take Impressionism's color and light, but add back some form, structure, or emotional punch.

- Paul Cézanne: Focused on underlying geometric structures and multiple viewpoints, treating nature in terms of the cylinder, sphere, and cone. His work fundamentally paved the way for Cubism. He wasn't just painting apples; he was dissecting seeing itself, trying to show you the essence of the form, like in his many studies of Mont Sainte-Victoire.

- Vincent van Gogh: Used intense, arbitrary color and expressive, swirling brushwork to convey powerful emotions and his inner turmoil. His paintings feel alive, vibrating with energy – you can almost feel the wind in "The Starry Night". Check out our Ultimate Guide to Van Gogh for more. His Sunflowers series isn't just about flowers; it's about the intensity of yellow, the energy of life itself.

![]()

- Paul Gauguin: Employed bold, flat areas of color (Cloisonnism) and symbolic imagery, often inspired by his travels to Tahiti seeking a more "primitive" existence. Gauguin was searching for something deeper, more spiritual, away from European complexities, evident in works like Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?.

- Georges Seurat: Developed Pointillism (or Divisionism), a meticulous technique using tiny dots of distinct color that blend in the viewer's eye. It's almost scientific, yet the results can be incredibly luminous, like the monumental A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. (See: Ultimate Guide to Pointillism).

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Famous for his dynamic, graphic portrayals of Parisian nightlife, especially cabarets, theaters, and brothels. He captured the energy and sometimes the seediness of Montmartre with such unforgettable lines, particularly in his posters like Moulin Rouge: La Goulue.

This late 19th-century push set the stage. The door was open, and the 20th century was about to kick it wide open.

Influence from Beyond: Non-Western Art and Modernism

Before we plunge into the 20th-century explosions, it's crucial to pause and acknowledge a significant, often understated, influence on many modern artists: non-Western art. As European empires expanded and global trade increased, artists in Paris and other centers were exposed to art from Africa, Oceania, Asia, and the Americas in museums and ethnographic collections. This wasn't always a respectful engagement – often filtered through colonial lenses – but the visual impact was undeniable.

Artists were captivated by the formal qualities of these objects: the bold lines and simplified forms of African masks and sculptures, the unique perspectives and decorative patterns of Japanese prints (known as Japonisme, which heavily influenced the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists), the symbolic power of Oceanic carvings. These non-Western traditions offered alternatives to the European academic tradition that modern artists were trying to escape. Picasso's breakthrough into Cubism, for example, was profoundly influenced by his encounter with African masks at the Trocadéro Museum in Paris. Gauguin's search for a more spiritual art led him to Tahiti, where he incorporated Polynesian motifs and color palettes into his work. This cross-cultural exchange, however complex its history, was a vital catalyst for the formal and conceptual innovations of Modernism.

Radical Experiments: Early 20th Century Avant-Gardes

As the 19th century turned into the 20th, things really started to get wild. This period saw an explosion of radical movements pushing art in entirely new directions, questioning everything that came before. The world was changing rapidly, and artists were right there, trying to make sense of it all.

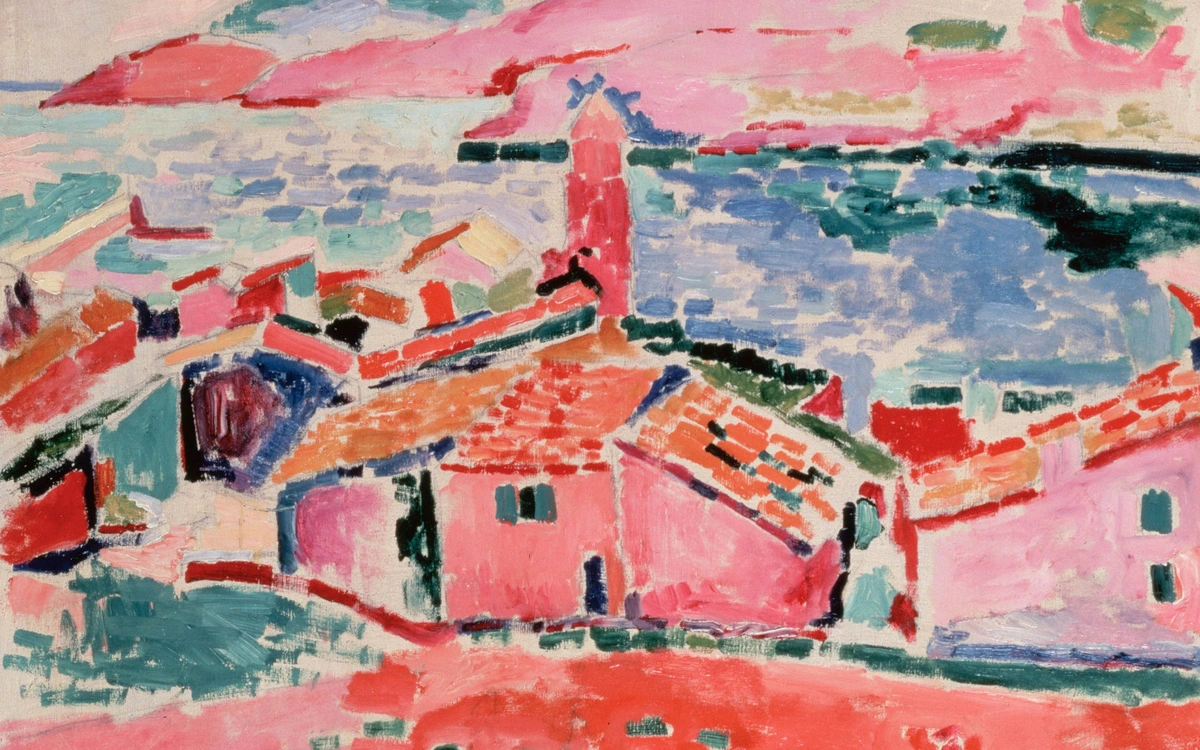

Fauvism (c. 1905-1908)

Core Idea: Unleash color from its descriptive role and use it for pure expression and emotional impact.

Characterized by its use of intense, non-naturalistic, arbitrary color for purely expressive purposes. The name, famously meaning "wild beasts," really captures the initial shock value. Looking at a Fauvist painting feels like the volume got turned up on the color dial. Techniques involved bold, direct brushwork and flat areas of vibrant color.

- Key Artists:

- Henri Matisse: A leader of the movement, known for his joyous use of color and line, aiming for an art of balance, purity, and serenity. Matisse could make color sing like few others; even his simplest lines feel full of life. His Woman with a Hat, with its vibrant, clashing colors, caused a sensation at the 1905 Salon d'Automne. Our Ultimate Guide to Matisse explores his journey.

- André Derain: Another key Fauve, known for vibrant landscapes and cityscapes, often painted alongside Matisse, like his colorful views of London.

- Focus: Liberation of color, simplified forms, emotional impact over realism. (See: Ultimate Guide to Fauvism).

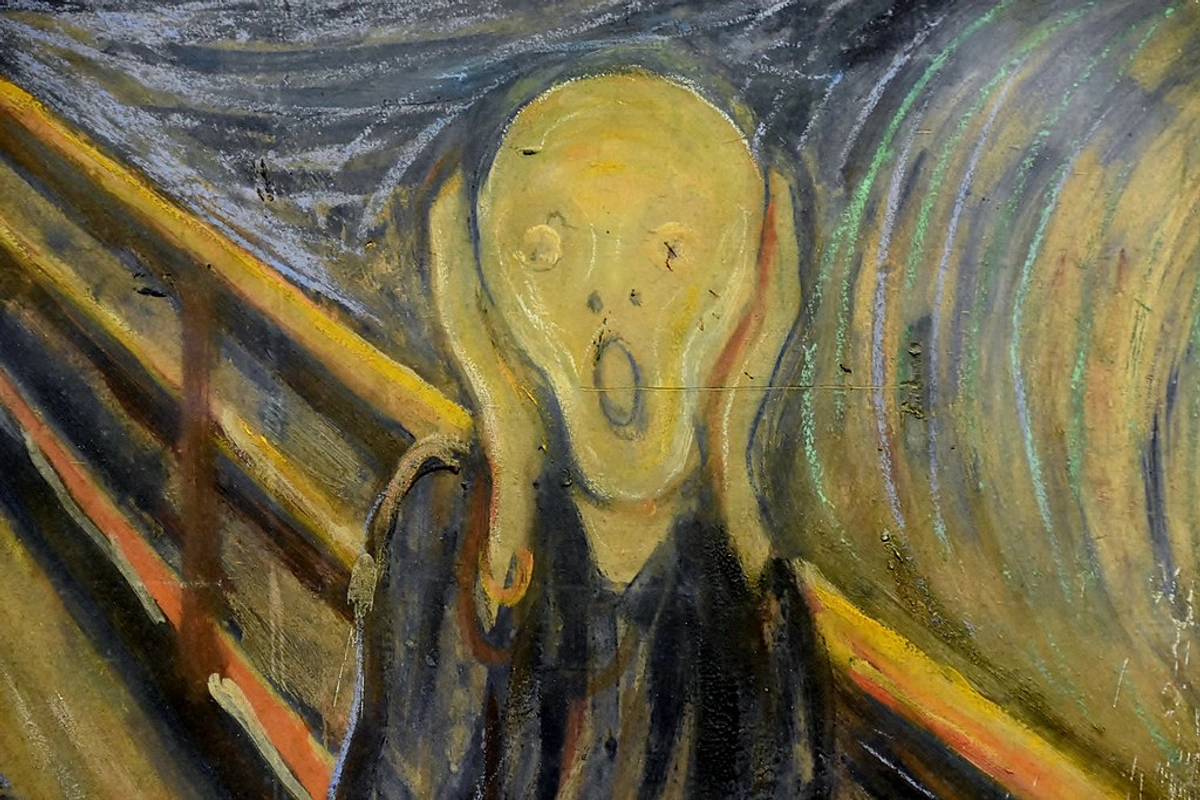

Expressionism (c. 1905-1920s)

Core Idea: Convey inner feelings and subjective experience rather than external reality, often through distortion and intense color.

Emerging partly in response to the anxieties of the burgeoning modern age and the lead-up to WWI, Expressionism emphasized subjective experience and emotional turmoil, often using distorted forms and bold colors to convey inner feelings rather than external reality. This was art straight from the gut, sometimes raw and unsettling. If Fauvism was turning up the color volume, Expressionism was turning up the emotional intensity.

- Key Groups/Artists:

- Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Germany: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde (intense, angular style, often depicting urban alienation and raw emotion).

- Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in Germany: Wassily Kandinsky (a pioneer of abstract art, seeking spiritual expression through color and form, as seen in Composition VII), Franz Marc (symbolic use of animals and color, like his famous Blue Horses). Kandinsky's early expressive works show his move towards pure abstraction.

- Other figures: Edvard Munch (Norway - his iconic The Scream perfectly encapsulates modern anxiety, a universal howl we all sometimes recognize), Egon Schiele (Austria - known for his intense, often disturbing psychological portraits and self-portraits with twisted lines that seem to expose the soul).

- Focus: Inner feelings, anxiety, spirituality, social critique. (See: Ultimate Guide to Expressionism).

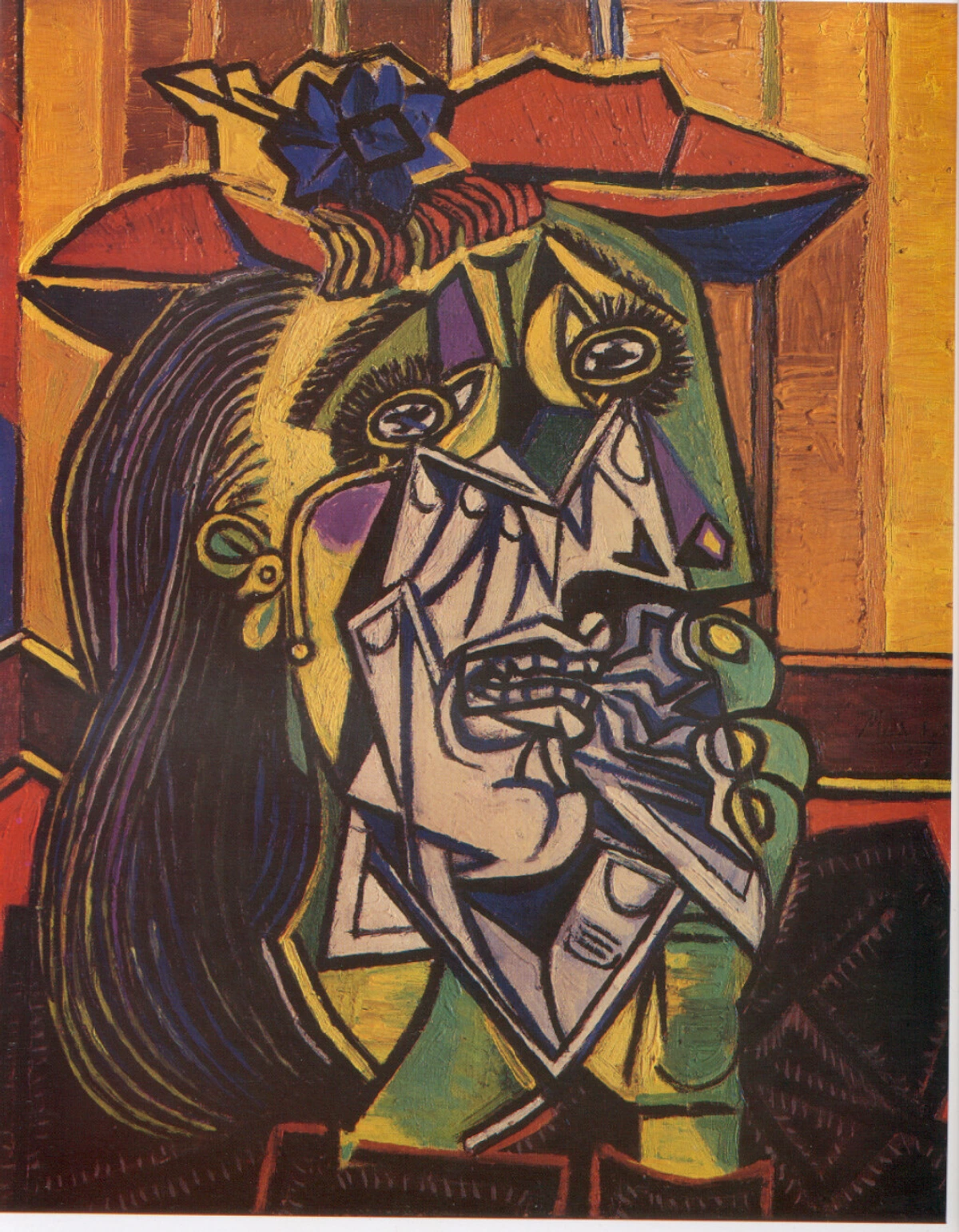

Cubism (c. 1907-1914)

Core Idea: Depict objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, fragmenting reality into geometric forms.

Revolutionized representation by depicting objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, fragmenting them into geometric shapes. This wasn't just a new style; it was a whole new way of thinking about space and form on a flat canvas. Trying to see all sides at once? My brain still struggles with parallel parking, let alone that! Their core idea? Shatter traditional perspective and show reality as a collection of fragments. Cubism also extended into sculpture, breaking down three-dimensional forms in similar ways.

- Key Artists:

- Pablo Picasso: Co-founder and arguably the most famous artist of the 20th century. His restless innovation drove Cubism and countless other developments. Picasso didn't just paint; he constantly reinvented what painting could be. His Les Demoiselles d'Avignon is often seen as a proto-Cubist work that shattered conventions. Explore his incredible range in our Ultimate Guide to Picasso.

- Georges Braque: Co-founder who worked closely with Picasso in developing Cubism, known for his more lyrical and structured approach. Braque was perhaps the more systematic thinker of the pair, meticulously analyzing form in works like Violin and Candlestick.

- Juan Gris: A key figure in Synthetic Cubism, known for his vibrant colors, collage elements, and intricate compositions, like his Portrait of Pablo Picasso.

- Phases:

- Analytic Cubism: Deconstruction of form, breaking objects into facets, use of a muted, monochromatic palette (browns, grays) to focus on structure.

- Synthetic Cubism: Building up forms using collage elements (like newspaper clippings or wallpaper) and brighter colors and simplified shapes. It's like reassembling the fragments into something new.

- Focus: Analyzing form, challenging traditional perspective, laying the foundation for much of later abstract art. (See: Ultimate Guide to Cubism).

Futurism (c. 1909-1914)

Core Idea: Celebrate the dynamism, speed, and energy of modern technology and urban life.

An Italian movement celebrating dynamism, speed, technology, machines, youth, and violence. Born from a fascination with the modern industrial world and a rejection of the past, they wanted to destroy museums and embrace the exhilarating chaos of modern life. Their manifestos were as loud as their art! Their core idea? Speed, noise, machines, the future!

- Key Artists: Umberto Boccioni (sculptures capturing movement, like Unique Forms of Continuity in Space), Giacomo Balla (paintings depicting speed, like Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash).

- Focus: Capturing movement, energy, violence, modern urban excitement.

These early 20th-century movements were like a series of explosions, each one shattering previous notions of what art could be.

Towards Abstraction and Beyond: Interwar and Mid-Century Innovations

The period between and after the World Wars saw further radical developments, including the rise of pure abstraction and movements questioning the very nature of art itself. Art got even more conceptual and mind-bending. The world had been through unimaginable trauma (WWI, the Great Depression, WWII), and art reflected that, sometimes by retreating inward, sometimes by questioning everything.

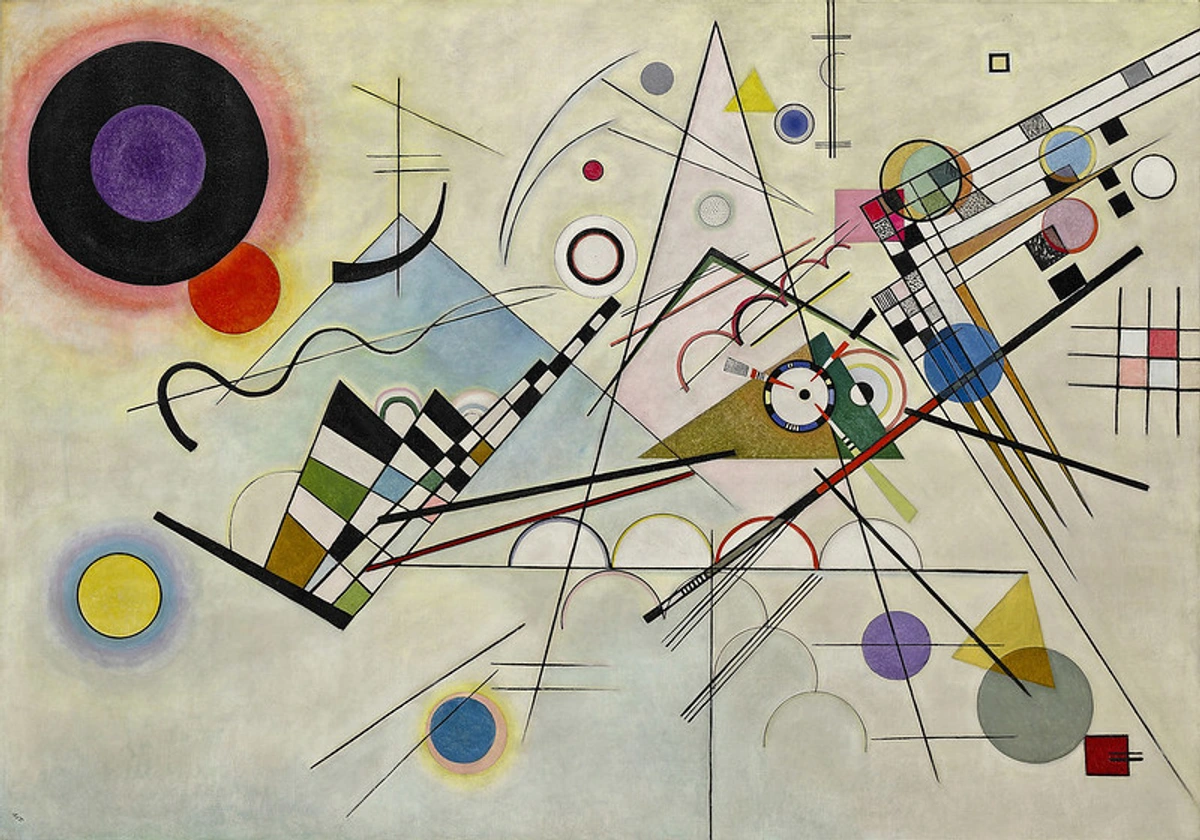

Early Abstraction

Core Idea: Abandon recognizable representation to focus purely on the elements of art itself – color, line, form.

Artists abandoned recognizable representation altogether, focusing purely on the elements of art: form, color, line, and texture. This was a monumental leap into the unknown. Why? For pioneers like Kandinsky and Malevich, it wasn't just a formal exercise; they sought to express spiritual truths, universal harmonies, or utopian ideals that they felt couldn't be captured by depicting the material world. It was art reaching for something beyond the visible. (See: History of Abstract Art).

- Key Pioneers:

- Wassily Kandinsky: Moved from expressive landscapes and Fauvist color to developing one of the first purely abstract styles, believing color and form alone could convey spiritual and emotional content. Seeing his work evolve is like watching someone learn a completely new language. His Composition VIII is a riot of abstract forms and colors.

- Kazimir Malevich: Founded Suprematism in Russia, aiming for the "supremacy of pure artistic feeling" expressed through basic geometric forms (squares, circles, rectangles) on a white background (e.g., Black Square). Radical simplicity taken to its extreme. It's hard to get more fundamental than a black square on a white canvas.

- Piet Mondrian: Developed Neoplasticism (associated with the De Stijl movement in the Netherlands) reducing his compositions to primary colors (red, yellow, blue), black lines (horizontal and vertical only), and white space, searching for universal harmony and order. His grids feel both rigid and somehow perfectly balanced, like Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow. De Stijl was the broader movement, while Neoplasticism was Mondrian's specific theory of abstract art within it.

- Focus: Exploring the fundamental elements of art, spiritual expression, utopian ideals. Understanding why abstract art is compelling often begins with these pioneers who dared to leave the visible world behind.

Dada (c. 1916-1924)

Core Idea: Reject logic, reason, and traditional aesthetics in protest against the madness of war and modern society.

An anti-art movement born out of disgust and protest against the perceived irrationality and brutality of World War I. It embraced irrationality, chance, absurdity, satire, and rejected traditional aesthetic values. Dada was art thumbing its nose at everything, including itself. It spread internationally from Zurich to Berlin, Paris, and New York, a global shrug of artistic shoulders. Their core idea? If the world is crazy, art should be too.

- Key Artists:

- Marcel Duchamp: A hugely influential figure who challenged the definition of art with his readymades (ordinary objects presented as art, like Fountain, a urinal). Duchamp basically asked, "What if the artist's idea is the art?" – a question that still echoes today. A readymade is like saying, "I didn't make this, but by choosing it and presenting it as art, I make it art." Mind. Blown. (See: What is Art?).

- Jean Arp: Known for his chance collages and biomorphic (curved, organic) abstract sculptures.

- Hannah Höch: A pioneering female Dadaist known for her incisive photomontages critiquing society and gender roles.

![]()

- Focus: Rejecting logic and traditional aesthetics, challenging art institutions, using humor and provocation, exploring the role of chance.

Surrealism (c. 1924 onwards)

Core Idea: Unlock the power of the subconscious mind and explore dreams, desires, and the irrational.

Officially launched in 1924 by André Breton, Surrealism was heavily influenced by Freudian psychology and aimed to unlock the power of the subconscious mind, exploring dreams, desires, and the irrational through unexpected juxtapositions and techniques like automatism (automatic drawing or writing, letting the hand move without conscious thought). Think melting clocks and impossible landscapes. Their core idea? The world of dreams is as real, maybe more real, than the waking world. Surrealism also manifested in sculpture and objects, bringing bizarre juxtapositions into three dimensions.

- Key Artists:

- Salvador Dalí: Famous for his meticulously rendered, bizarre dreamscapes and flamboyant personality. Dalí's technical skill combined with his wild imagination created unforgettable, often unsettling images, like The Persistence of Memory.

- René Magritte: Known for his witty and thought-provoking paintings that play with perception and reality, often featuring ordinary objects in strange contexts (like The Treachery of Images, "Ceci n'est pas une pipe"). Magritte messed with your head in the most elegant way.

- Max Ernst: Experimented with techniques like frottage (rubbing) and grattage (scraping) to create textured, fantastical images.

- Joan Miró: Developed a unique style of biomorphic abstraction with playful, symbolic forms floating in space.

- Frida Kahlo: While often associated with Surrealism (and she did exhibit with them), Kahlo herself said she painted her reality, not dreams. Her powerful, deeply personal self-portraits exploring pain, identity, and Mexican culture share Surrealism's exploration of the inner world, like The Two Fridas. She is a key figure whose work resonates deeply today.

- Focus: Dreams, the irrational, the subconscious, unexpected juxtapositions, psychological exploration, automatism. (See: Understanding Symbolism).

These movements delved into the mind and questioned reality itself, setting the stage for even more radical shifts.

Mid-Century Powerhouses: Abstract Expressionism (c. 1940s-1950s)

Core Idea: Express universal emotions or the sublime through large-scale abstraction, focusing on the act of painting itself.

Building on the ideas of abstraction and expression, Abstract Expressionism was the first major American avant-garde movement to achieve international influence, centered in New York City after WWII. The historical context of post-war anxiety and the Cold War certainly fueled a sense of existential angst and a desire for universal, non-representational expression. This marked a significant shift of the art world's center from Paris to New York. Characterized by large canvases, emotional intensity, and a focus on the act of painting itself. This was American art stepping onto the world stage with bold confidence. Their core idea? Art as a direct expression of the artist's inner state, writ large.

- Key Artists: Abstract Expressionism broadly splits into two main tendencies:

- Action Painting: Focused on the physical act of painting, gesture, and energy. It's about the process, the dance with the canvas.

- Jackson Pollock: Famous for his revolutionary drip paintings, where paint was poured, dripped, and splattered onto large canvases laid on the floor. It's pure energy made visible, like Convergence.

- Willem de Kooning: Known for his aggressive, gestural paintings oscillating between abstraction and fierce figuration (especially his Woman series). His brushstrokes feel raw and powerful.

- Franz Kline: Created powerful, large-scale black-and-white abstract compositions suggesting architectural structures or calligraphy.

- Lee Krasner: A key figure whose dynamic, often overlooked work evolved through various stages, from intricate webs to bold collages and expressive gestures. She was Pollock's wife but a formidable artist in her own right, constantly experimenting.

- Color Field Painting: Focused on large areas (fields) of flat, solid color to evoke contemplative or sublime emotions. It's less about gesture and more about the immersive power of color itself.

- Mark Rothko: Created iconic paintings with large, soft-edged rectangular fields of luminous color meant to engulf the viewer in an emotional or spiritual experience. Standing in front of a Rothko can feel incredibly immersive, almost like stepping into pure color, like his No. 14, 1960.

- Barnett Newman: Known for his large canvases dominated by fields of color broken by vertical lines he called "zips," seeking the sublime.

- Clyfford Still: Developed a unique style with jagged fields of color creating dramatic, fractured landscapes.

- Helen Frankenthaler: Developed the "soak-stain" technique, pouring thinned paint onto unprimed canvas to create luminous, fluid fields of color, bridging Abstract Expressionism and later Color Field painting.

- Joan Mitchell: Known for her large, energetic canvases filled with vibrant, expressive brushstrokes that often evoked landscapes or natural forms.

- Focus: Spontanety, subconscious expression, monumental scale, conveying universal emotions or the sublime, the physical act of painting. (See: Abstract Expressionism: Ultimate Guide to the Art & Artists).

Abstract Expressionism was intense, subjective, and deeply personal. Naturally, the next generation had something to say about that...

Late Modernism & Transitions to Contemporary (c. 1950s-1970s)

The later phases of Modernism saw reactions against the intense subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism and further blurring of lines between 'high' art and popular culture, paving the way for what we now call contemporary art. It's like art stepped out of the studio and onto the street, or into the supermarket.

Pop Art

Core Idea: Incorporate imagery from popular culture, mass media, and consumerism, often with irony or critique.

Emerged in the UK and US in the 1950s and boomed in the 1960s, incorporating imagery from advertising, comic books, mass media, and everyday consumer culture. Pop Art looked outwards at the world of stuff, celebrity, and advertising, often reacting against the perceived seriousness and introspection of Abstract Expressionism. Their core idea? Let's look at the world around us, the world of brands and celebrities, and make art about that. Techniques included screen printing (made famous by Warhol) and using Ben-Day dots (like Lichtenstein) to mimic commercial printing processes.

- Key Artists:

- Andy Warhol: The superstar of Pop, famous for his silkscreen prints of Campbell's Soup Cans, Coca-Cola bottles, and celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, exploring themes of mass production, consumerism, and fame. Warhol understood the power of the repeated image like no one else.

- Roy Lichtenstein: Known for his large paintings mimicking the style of comic book panels, complete with Ben-Day dots and speech bubbles, like Whaam!.

- Claes Oldenburg: Created large-scale, often soft, sculptures of everyday objects like hamburgers, typewriters, and lipstick tubes, making the mundane monumental.

- Richard Hamilton: A key British Pop artist, known for his collage Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing?, often considered one of the earliest Pop works.

- Focus: Critiquing or celebrating consumer culture, blurring high/low art distinctions, mechanical reproduction, imagery from popular culture.

Minimalism

Core Idea: Strip art down to its essential geometric forms and materials, emphasizing the object's presence and its relationship to the viewer and space.

Emerged in the 1960s, seeking to strip art down to its essential geometric forms, often using industrial materials and fabrication processes. It rejected expression and emphasized the artwork's relationship to the viewer and the space. Minimal art isn't about anything other than what it is: shape, material, space. It was another reaction against the emotional drama of Abstract Expressionism. Their core idea? Less is more. Let the materials and forms speak for themselves.

- Key Artists:

- Donald Judd: Known for his "specific objects," often stacked geometric boxes made from industrial materials like metal and Plexiglas.

- Dan Flavin: Created installations using commercially available fluorescent light tubes.

- Carl Andre: Famous for his floor sculptures made of arrangements of identical industrial units, like metal plates or bricks.

- Sol LeWitt: While also associated with Conceptual Art, his geometric sculptures and wall drawings based on instructions fit within Minimalist aesthetics.

- Focus: Objecthood, industrial aesthetics, interaction with space, removal of the artist's hand, geometric abstraction.

Conceptual Art

Core Idea: The idea or concept behind the artwork is more important than the finished object.

Emerged in the mid-1960s, prioritizing the idea or concept behind the artwork over the physical object or traditional aesthetics. The artwork could be instructions, text, photographs, or even just an idea. This really pushed the boundaries of what art could be. Their core idea? Art is in the mind, not just on the wall. Putting a urinal in a gallery? Honestly, some days I feel like my studio floor could qualify, but Duchamp's Fountain was about the idea of challenging the art world, not the object itself.

- Key Artists:

- Sol LeWitt: Famous for his wall drawings executed by others following his written instructions, emphasizing the idea over the execution.

- Joseph Kosuth: Explored the relationship between language, image, and reality, famously in works like One and Three Chairs.

- Lawrence Weiner: Known for his language-based works, often presented as text statements installed on walls or existing as text alone.

- Focus: Ideas, language, systems, philosophy, challenging traditional definitions and forms of art.

These late movements brought us right up to the edge of what we now call contemporary art, leaving a legacy of expanded possibilities.

Other Towering Figures of Modernism: Artists Who Forged Unique Paths

While many artists fit broadly within the movements above, some carved out such unique paths or bridged styles in ways that deserve special mention. Finding a neat box for everyone is tough, and maybe not even desirable! These figures are often among the most famous modern artists searched for, precisely because their individual vision transcended easy categorization or spanned significant periods.

- Georgia O'Keeffe: Developed a highly personal style known for her magnified paintings of flowers (Jimson Weed), New Mexico landscapes, and New York skyscrapers, blending abstraction and representation with a unique sensuality. Her giant flowers feel both abstract and intensely real.

- Edward Hopper: Captured the loneliness and alienation of modern American life in his realistic yet subtly unsettling depictions of urban and rural scenes. His paintings have a distinct mood, a quiet melancholy, like Nighthawks.

- Constantin Brâncuși: A Romanian sculptor who radically simplified form, seeking the essence of his subjects (like birds in flight or fish) through elegant, abstract shapes in stone, bronze, and wood. His work feels timeless, like Bird in Space.

- Alberto Giacometti: Swiss sculptor and painter known for his elongated, emaciated figures (Walking Man series) that seem to embody existential angst and the fragility of the human condition in the post-war era. His walking figures are hauntingly powerful.

These artists remind us that even within revolutionary periods, individual genius can forge its own path.

Key Characteristics Revisited: What Unites Modern Artists?

Despite the immense diversity across movements, certain threads connect many modern artists. These are the underlying principles that, for me, define this revolutionary era:

- Spirit of Innovation: A relentless drive to experiment and find new ways of making art. You can see how artists build on each other, tracing their own unique paths, much like exploring an artist's personal journey reveals their evolution. It's a constant push forward, a refusal to stand still.

- Break with Tradition: A conscious rejection or radical reinterpretation of past artistic conventions, particularly the academic Salon system. They weren't just tweaking the old masters; they were dismantling them.

- Subjectivity: An emphasis on the individual artist's perspective, emotion, or inner world. The artist's unique voice became central, making the personal universal.

- Formal Exploration: A focus on the elements of art itself – color (how artists use color), line, form, texture, composition (composition basics art viewers). How the art is made, and what those elements do, became as important as what is depicted.

- Modern Consciousness: An engagement with the realities and complexities of modern life – its speed, its anxieties, its new technologies, its changing social fabric. They weren't painting ancient myths; they were painting the world they lived in, for better or worse.

How to Appreciate Modern Artists: A Personal Take

Modern art can sometimes feel challenging or unfamiliar. Don't worry, you're not alone if you've ever stood in front of an abstract canvas and thought, "What am I supposed to be seeing here?" I've been there! I remember feeling completely lost in a room full of Abstract Expressionism until someone pointed out the energy of the brushstrokes. Here’s what helped me and what I think might help you:

- Know the Context: Understanding the specific art movement ([link: all-art-styles]), the artist's aims, and the historical background enhances appreciation. Knowing why Kandinsky went abstract or why Duchamp put a urinal in a gallery adds layers of meaning. It's like reading the liner notes before listening to a challenging album.

- Embrace the New: Recognize that modern artists were deliberately breaking rules. Try not to judge their work solely by the standards of earlier art (like perfect realism). They were inventing new languages. It's okay if it doesn't look like a photograph; it's not trying to. Ask yourself, what question was the artist asking?

- Look Beyond Likeness: If the work isn't representational, focus on how it's made – the use of color, the energy of the brushstrokes, the composition, the materials, the underlying concept. How does it make you feel? Sometimes the feeling is the point.

- See it in Person: Visit museums with strong modern collections. The scale, texture, and sheer presence of the artwork are often lost in reproduction. Experiencing diverse art, perhaps contrasting it with contemporary works (like some you might find for sale online) or visiting dedicated spaces like the artist's museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, broadens understanding immensely. I remember seeing a Rothko for the first time in person – the photos did not prepare me for how the colors seemed to hum and envelop you.

- Be Open and Curious: Ask questions: What was the artist trying to achieve? How does it make me feel? Why might it have been revolutionary or shocking at the time? Understanding why people like modern art often requires this curiosity, letting go of expecting everything to look like a photograph. It's a conversation, not a test.

Why is modern art sometimes controversial or difficult to understand?

Great question! It often boils down to that fundamental break from tradition. For centuries, art was largely about skill in realistic depiction and telling familiar stories (religious, historical, mythological). Modern artists challenged both of these things. They prioritized ideas, emotions, and formal experimentation over perfect likeness. They questioned the very definition of art itself (thanks, Duchamp!). This can be jarring if you're expecting something familiar. It requires a different kind of looking, a willingness to engage with the artist's intent and the artwork's formal qualities rather than just its subject matter. It's like expecting a novel and getting a poem – both are valid forms of literature, but you need to approach them differently.

The Legacy of Modern Artists

The impact of modern artists on art history and culture is immeasurable. They didn't just change art; they changed how we think about art and creativity itself:

- Foundation for Today: Nearly all contemporary art builds upon, reacts against, or dialogues with the innovations of Modernism. They set the stage for everything that came after. My own work, which is often abstract and uses color expressively, owes a massive debt to these pioneers.

- Expanded Definition of Art: They radically broadened what art could be, incorporating new materials (collage, found objects, light), techniques (drip painting, automatism, screen printing), and concepts (the idea as art). The possibilities exploded.

- Enduring Influence: Modernist ideas about form, function, expression, and abstraction continue to shape visual culture, design, architecture, and how we think about creativity itself. The unique journeys of these artists provide ongoing inspiration for creators today, myself included sometimes! Their willingness to fail, to experiment, to push boundaries is a constant reminder that making art is an ongoing process of discovery.

Conclusion: A Century of Revolution, Seen Through My Eyes

The modern artists, spanning from the Impressionists to the Conceptualists, represent a period of intense artistic upheaval and creativity. They dismantled old certainties, explored new frontiers of perception and expression, and grappled with the complexities of a rapidly changing world. Figures like Monet, Van Gogh, Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky, Duchamp, Kahlo, Pollock, Rothko, and Warhol, among countless others featured in this guide, didn't just create paintings or sculptures; they redefined the very nature and purpose of art. Exploring their work offers a fascinating journey through a century of revolution that continues to shape how we see and create today, reminding us that art is always evolving, always questioning, and always, always, deeply human. For me, understanding them isn't just about history; it's about understanding the roots of my own creative impulse.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Who are the most famous modern artists? This is subjective, but undisputed giants frequently cited include Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Andy Warhol. Others like Georgia O'Keeffe, Edward Hopper, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec are also incredibly well-known. Many appear on lists of the top artists ever.

- What is the difference between modern and contemporary artists? The main difference is time period. Modern artists generally worked from the late 19th century to around the 1970s. Contemporary artists are typically those working from the 1970s to the present day. Contemporary art often engages with globalization, digital technology, identity politics, and environmental concerns in ways that built upon or reacted against Modernism. Think of Modernism as the revolutionary foundation and Contemporary art as the diverse, ever-evolving structure built upon it.

- When did Modern Art start and end? There's no exact universal agreement, but it generally started around the 1860s/1870s with Realism's challenge and the rise of Impressionism, and ended around the 1960s/1970s with the emergence of Postmodernism and movements like Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and Pop Art signaling a shift.

- Was all modern art abstract? Absolutely not! While the development of abstract art was a major and crucial innovation within Modern Art, many significant modern movements remained figurative (representational) or semi-figurative. These include Impressionism, Post-Impressionism (Van Gogh, Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec), Fauvism, Expressionism (Munch, Schiele, Kirchner), Surrealism (Dalí, Magritte, Kahlo), and Pop Art. Modern art encompasses a vast range of styles, from pure abstraction to stylized realism.

- Why is modern art sometimes controversial or difficult to understand? As I touched on earlier, it's largely because it broke so dramatically with centuries of tradition that valued realistic representation and familiar subjects. Modern artists prioritized ideas, emotions, and formal experimentation, challenging the very definition of art itself. This requires viewers to engage with the work on different terms, looking beyond just what is depicted to understand the artist's intent, the historical context, and the formal qualities of the piece. It's a shift from passive viewing to active interpretation.

- Where can I learn more about specific modern art movements? You can explore our dedicated guides, such as those on Modern Art overall, Fauvism, Cubism, Pointillism, Abstract Art history, and guides to specific artists like Picasso, Matisse, Van Gogh, and Rothko.

- Where can I buy art by modern masters? Original works by famous modern artists are typically sold through major international auction houses (like Sotheby's, Christie's) and high-end galleries specializing in the secondary market. Be prepared, these works command very high prices (see understanding art prices). Original Prints (like lithographs, etchings, or screenprints) and editioned works created by the artists during their lifetime can sometimes be found at more accessible (though still often significant) price points through reputable print dealers, galleries specializing in works on paper, and auctions. Always ensure authenticity and provenance. (See: How to Buy Modern Art, Prints vs. Paintings). If you're looking for something more contemporary, perhaps inspired by these masters but created today, you might explore art for sale online from living artists.