Henri Matisse: Master of Color, Joy & Modern Artistry

Dive into the vibrant world of Henri Matisse: master of color, joyful simplicity, and revolutionary forms. Explore his journey from Fauvist to cut-out innovator, and his enduring legacy in modern art, through a personal lens.

Henri Matisse: The Ultimate Guide to the Master of Color and Joy

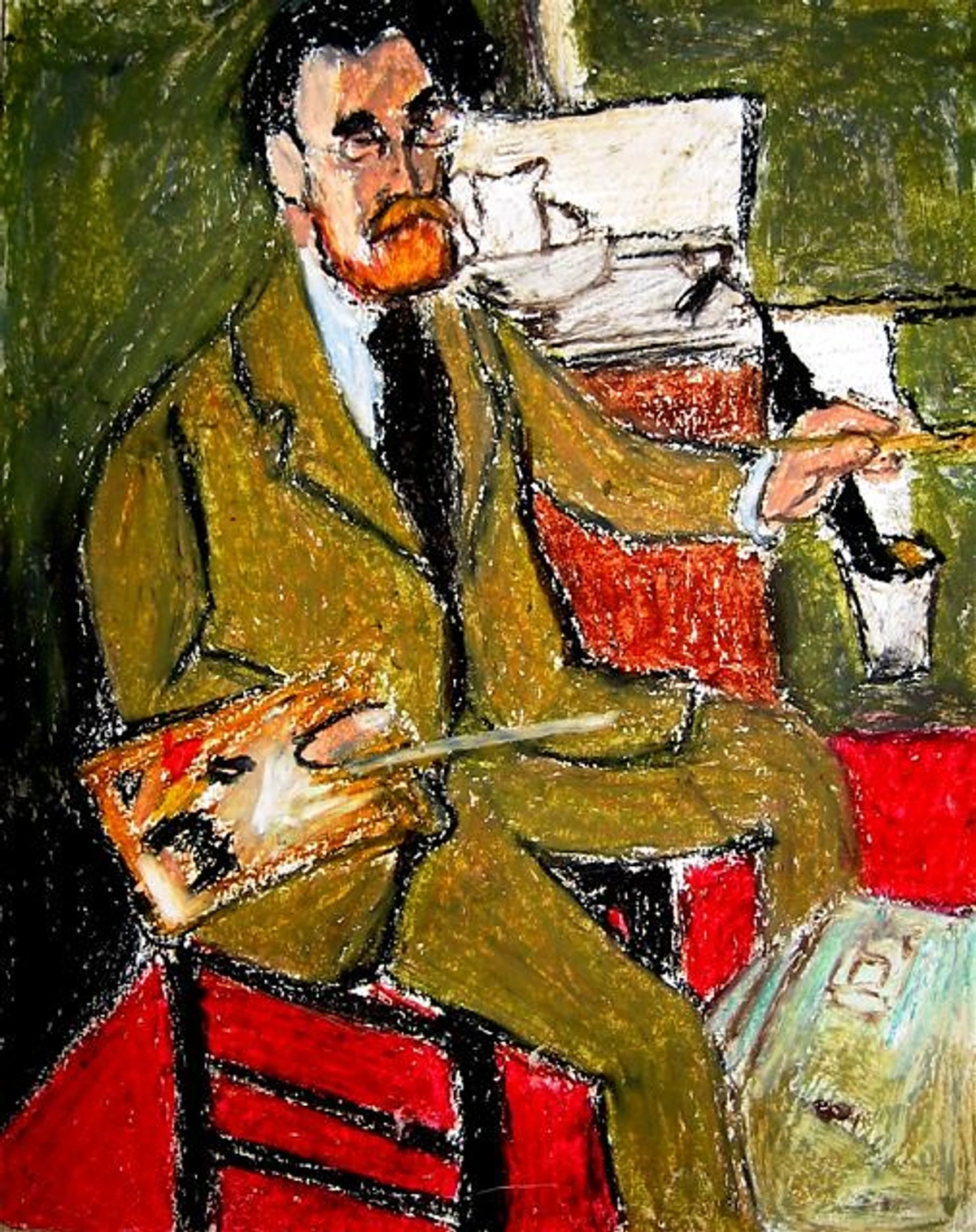

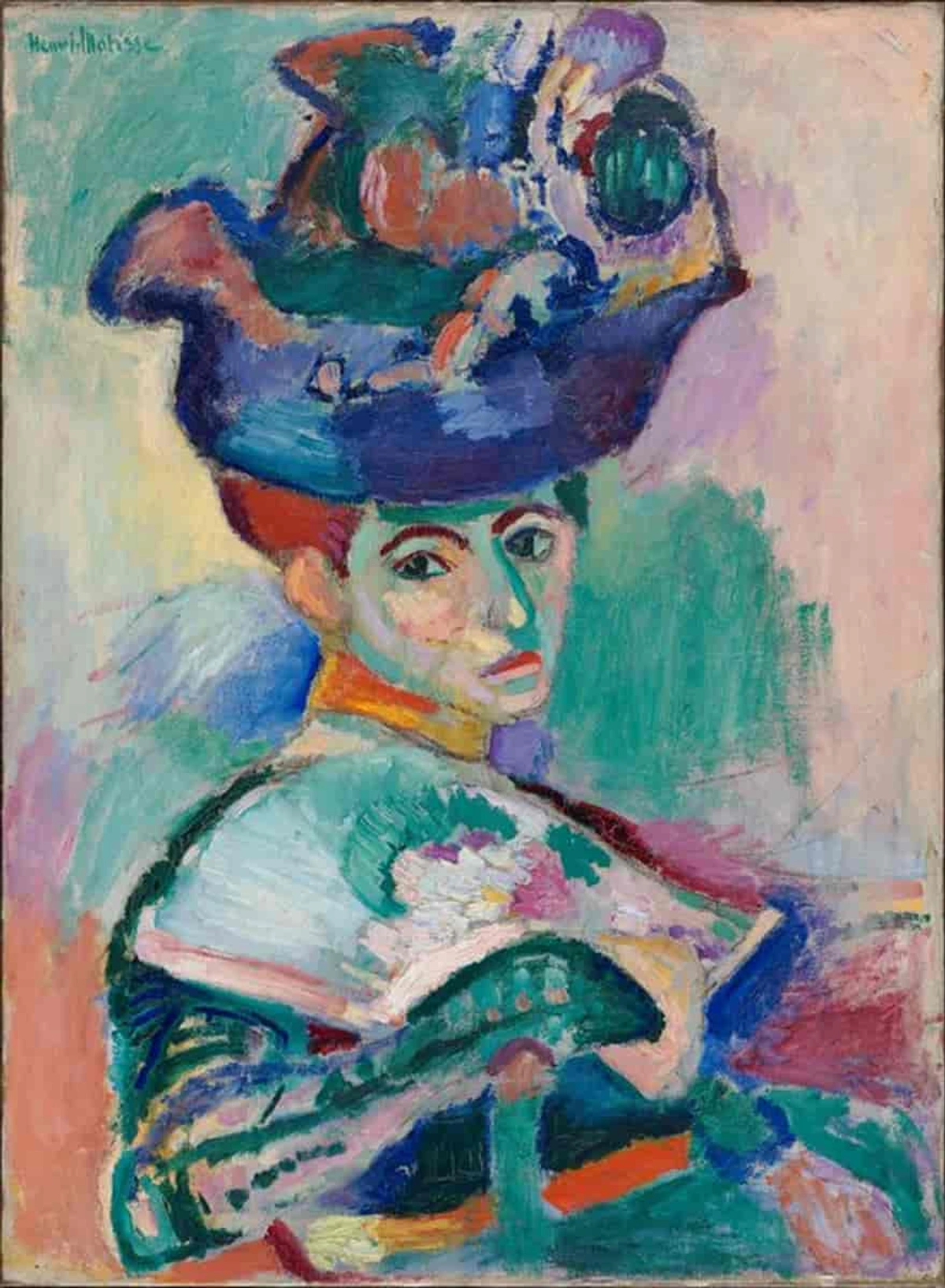

Sometimes, you stumble upon an artist, and their work just clicks. Instantly. Other times, it takes a bit more… well, looking. Maybe even some reading, which, let's be honest, can feel like homework sometimes. For me, Henri Matisse initially fell into that second category. His work seemed deceptively simple, almost childlike. I remember seeing reproductions of his cut-outs, like the Blue Nudes, and thinking, "Is that it? Just some shapes cut out of paper?" Or perhaps seeing a painting like Woman with a Hat (1905) and wondering about the seemingly arbitrary splashes of color. It felt so effortless, so easy, that I initially missed the profound depth and revolutionary spirit lurking beneath the surface. It took time, and yes, some reading, to understand that the apparent simplicity was the result of a lifetime of searching, refining, and distilling his vision. Unlike, say, a Caravaggio, whose dramatic chiaroscuro hits you like a lightning bolt, Matisse's brilliance often requires a gentle unfolding. It’s almost funny, isn't it, how sometimes the most profound things can initially appear so unassuming, making you feel a bit silly for not 'getting it' right away?

Matisse wasn't just painting pretty pictures; he was fundamentally changing the way we see color, shape, and emotion in art. He wrestled with tradition, embraced radical ideas, and ultimately crafted a visual language dedicated to joy, serenity, and the pure pleasure of seeing – a revolutionary pursuit of visual delight. Forget the misconception that art is dull; Matisse is proof that it can be an electrifying, life-affirming experience. So, let's dive into the world of a man who famously wanted his art to be like a "good armchair" – comforting, yes, but profoundly revolutionary in its insistence on art as a source of peace and restorative beauty in a turbulent modern world.

From Law Books to Paint Brushes: Who Was Henri Matisse?

Born Henri Émile Benoît Matisse in 1869 in northern France, a career in art wasn't exactly preordained. He actually started out studying law, presumably a much more 'sensible' and predictable legal path. Before Paris, he initially studied law in his hometown, Le Cateau-Cambrésis, and began his formal art training at the local drawing school in Saint-Quentin. Imagine telling your parents, "Actually, I'm ditching this stable legal career to mess around with paint." Takes some guts, right? This feeling of a seismic shift, from a structured path to a vibrant artistic one, resonates deeply with my own experience of finding my creative calling – that familiar pull towards something less certain but infinitely more me. The structured, predictable world of law versus the messy, uncertain, but vibrant world of art – finding your true calling often feels less like a gentle nudge and more like a seismic shift. And honestly, who needs a respectable law practice when you can create a literal paradise with a paintbrush? (For some, that stability is their paradise, and that's perfectly valid, but it never quite clicked for me.)

A bout of appendicitis in 1889 changed everything. While recovering, his mother gave him a paint box to pass the time. He later described this moment as discovering a "kind of paradise." And what a paradise it must have been! The sheer tactile pleasure of squeezing paint from tubes, the way colors blend or clash on a palette, the magic of making a flat surface come alive with just a few strokes – it’s a visceral experience. I can almost feel the fresh joy of that first brushstroke, the quiet thrill of seeing something new emerge from nothing. It’s that feeling of finding a place where the world makes sense, where every choice, every mark, feels profoundly right, even if it’s just for a moment. Isn't it wild how sometimes the most significant pivots in life come from the most mundane, unexpected places – like a quiet recovery from an illness?

The law books were quickly forgotten, and Matisse dedicated himself to art, moving to Paris to study formally (at the Académie Julian and later the École des Beaux-Arts) and informally, absorbing the influences buzzing around the city. Despite the immediate draw, his early years in Paris weren't without their struggles; he initially faced financial hardship and the challenge of establishing himself in a competitive art world, selling few works and often returning to his hometown for support. This wasn't just a career change; it was the beginning of a journey that would place him alongside figures like Picasso as a titan of modern art. You can see parallels in many artists' journeys, that moment of finding their true calling, a theme that resonates deeply with any creative path, sometimes even visible in a creative timeline.

Matisse's personal life, while often kept private, was intertwined with his art. He married Amélie Parayre in 1898, and she became one of his most frequent and recognizable models, appearing in numerous paintings throughout his career. They had three children, Marguerite, Jean, and Pierre. While the focus of his work remained firmly on artistic exploration rather than narrative, the presence of his family, particularly Amélie, adds a quiet human dimension to his vibrant interiors and portraits. Later in his career, after his separation from Amélie, his relationship with his assistant Lydia Delectorskaya became incredibly significant, not just personally but artistically. Lydia became a key model for many of his later paintings, including works like Large Red Interior (1948) and La Blouse Roumaine (1940), and was instrumental in the creation of the cut-outs, managing the studio and assisting with the physical process. This highlights how the people closest to an artist can profoundly shape their work, sometimes in ways history doesn't always fully acknowledge. It’s a reminder that inspiration isn’t just some abstract lightning bolt; it often stems from the deep, complex connections we forge with the people around us, their presence a quiet, constant force shaping our creative output. Perhaps the patient presence of my loved ones, simply listening or observing, subtly influences the flow of my own creative process, leading to unexpected insights.

The Evolution of Matisse: Key Artistic Periods

Matisse's career wasn't static; it was a constant evolution, a searching.

- Early Years & Learning the Ropes (c. 1890-1904): Like many artists, Matisse started by learning from the masters. He absorbed lessons from [Impressionism] and [Post-Impressionism], particularly artists like [Van Gogh], Cézanne, and Gauguin. You can see him experimenting with brushwork and color, still relatively traditional but hinting at the boldness to come. A notable early work like La Desserte (The Dessert) (1897) shows his traditional training in composition and perspective, even while hints of his burgeoning interest in color and surface are present. While his early exhibitions didn't always garner widespread critical acclaim, they marked his entry into the public art scene, gradually building the foundation for his later, more radical breakthroughs.He studied initially at the Académie Julian and later was admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts, where he became a student of the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau. Moreau was, by all accounts, a rather liberal teacher for the time, encouraging his students to find their own paths and even visit the Louvre to copy the Old Masters while developing their individual styles. Moreau's liberalism wasn't just about freedom; he emphasized the importance of imagination and personal expression over strict academic rules. He reportedly told his students, "You must think color, you must be able to dream in color." This focus on the expressive and imaginative potential of color, rather than just its descriptive function, seems to have deeply resonated with Matisse and laid crucial groundwork for his later breakthroughs.Matisse spent time studying and copying works by artists like Chardin, Raphael, and Poussin, honing his foundational skills in composition, form, light, and figure drawing before he would later make his more radical breaks. It's fascinating to think how this early encouragement and rigorous traditional training might have nurtured Matisse's later willingness to break radically from tradition – he was mastering the rules before breaking them. It reminds me of the countless hours I spent on foundational drawing exercises, thinking, "Is this really going to help?" only to realize much later how deeply those roots support the wildest branches of experimentation.This formal training grounded him, and later, between 1908 and 1911, Matisse himself would run the Académie Matisse, a free art school in Paris, where he mentored a new generation of artists, including figures like Max Weber and Hans Purrmann, sharing his radical approaches to color and form. His long-time dealer, Ambroise Vollard, played a crucial role in promoting his early works and establishing his reputation, purchasing many of his pieces and giving him his first solo exhibition in 1904.

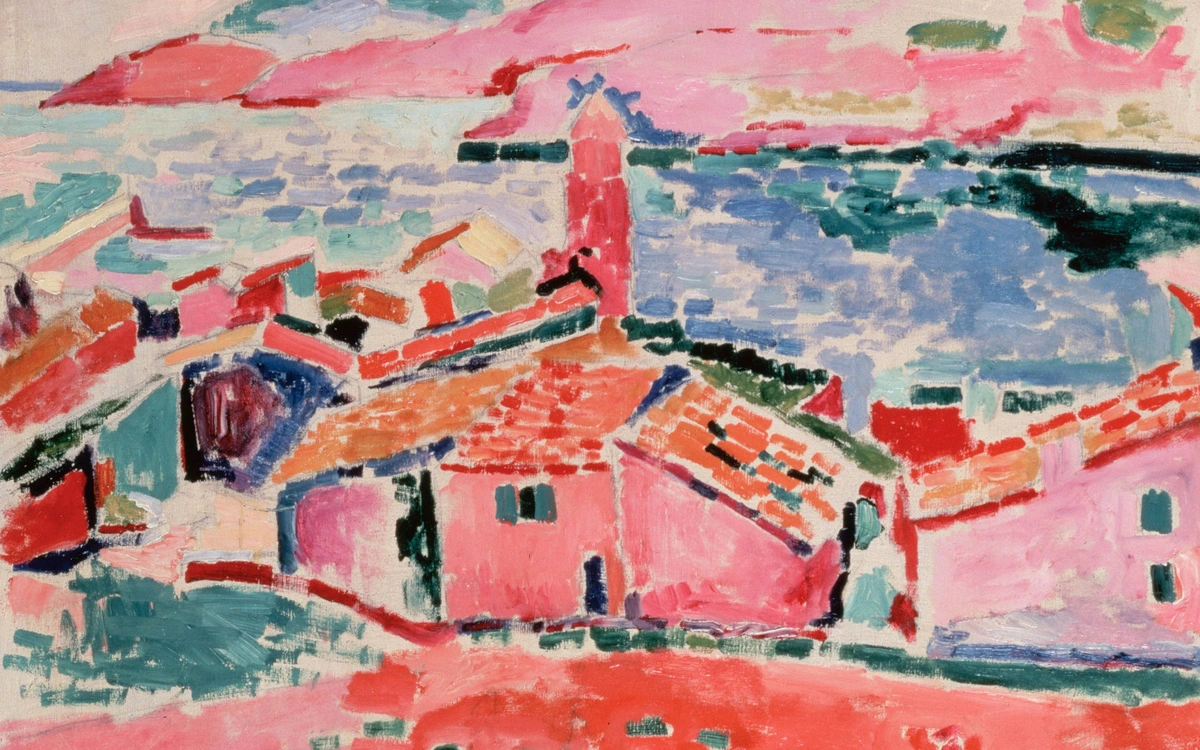

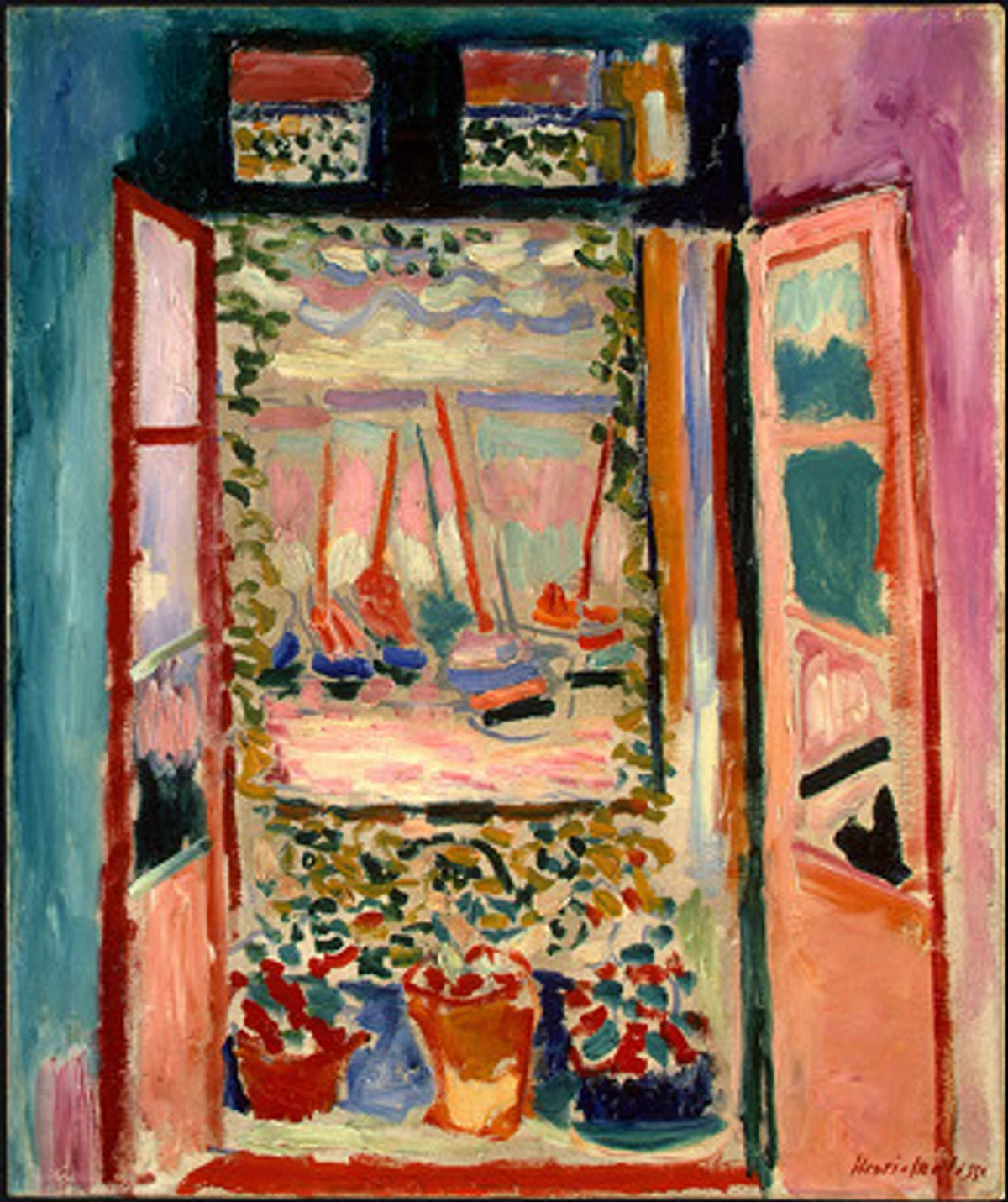

- The Fauvist Explosion (c. 1905-1908): This is where Matisse truly burst onto the scene. Working alongside artists like André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, he unleashed Fauvism (from the French fauves, meaning "wild beasts") upon a shocked Parisian art world. Characterized by intense, non-naturalistic color and bold brushwork, this style aimed to express emotion directly. Think paintings where skies are orange, trees are blue, and faces are patches of vibrant, clashing hues. Technically, they achieved this intensity by often applying paint directly from the tube, using thick, visible brushstrokes, and placing complementary colors (like red and green, or blue and orange) side-by-side to create maximum vibration and intensity, making the colors almost sing on the canvas – like a visual hum that vibrates right off the canvas. Consider the shocking juxtapositions of orange and blue on the face in Woman with a Hat (1905) or the vibrant, expressive landscape of View of Collioure (1905). Key works like these and The Joy of Life (1905-1906) define this electrifying period.

It's hard to overstate the jolt Fauvism delivered to the establishment. Imagine the Salon d'Automne in 1905: polite society expecting pleasant landscapes and portraits, suddenly confronted with canvases that screamed with color. It must have felt like walking into a quiet library expecting hushed tones and finding yourself in the middle of a vibrant, clashing street festival. Critics were aghast, with one prominent critic, Louis Vauxcelles, famously dubbing them "wild beasts" after seeing their paintings surrounding a traditional-looking sculpture, exclaiming, "Donatello au milieu des fauves!" (Donatello among the wild beasts!). One particularly scathing review described Woman with a Hat as having colors flung arbitrarily at the canvas. Can you imagine the pearl-clutching? It's almost funny now to think how genuinely shocking it was, like someone turned the volume up way too high on the color dial! What if I had been a critic there? I probably would have been just as confused, before the 'aha!' moment hit. I mean, my first reaction to abstract art was often, "What is that?" only for it to slowly, beautifully, reveal its profound logic over time. But Matisse and his colleagues weren't just being provocative for the sake of it. They were exploring the expressive power of color, its ability to evoke feeling and structure a composition independently of realistic depiction. It was a radical departure, suggesting that the artist's internal feeling, expressed through color and form, was more important than slavishly copying nature. Looking at Woman with a Hat now, it's easy to see the genius, but I can only imagine the sheer shock it must have caused back then. This idea underpins so much of what makes abstract art compelling even today. Dive deeper into this movement with our Ultimate Guide to Fauvism.

After the Fauvist intensity, Matisse's style continued to evolve, moving into a period of deeper experimentation and refinement.

- Post-Fauvist Experimentation & Travel (c. 1908-early 1940s): After the initial Fauvist explosion, Matisse didn't rest on his laurels. He travelled, absorbing influences from Islamic art (patterns, decoration) and spent considerable time in Nice on the French Riviera. His travels, especially to Morocco in 1912 and 1913, were profoundly influential. It wasn't just a holiday; it was an immersion. Think about stepping into a completely different visual world – the intensity of the Mediterranean light, the specific architecture of Nice with its balconies and patterned tiles. Islamic art, in particular, with its emphasis on pattern, flatness, and decorative surface – think intricate zellij tilework, vibrant arabesques, or rich textiles – provided a powerful example of how a composition could be built on surface decoration rather than illusionistic space, resonating with Matisse's desire to move beyond traditional Western perspective. The inherent aniconism (lack of representational imagery) in much Islamic art likely also reinforced his move towards abstraction and pattern over strict realistic representation. He wasn't just observing; he was absorbing a different way of structuring visual experience, one that embraced pattern and surface as primary elements.This focus on surface, pattern, and flatness was a profound break from the Western tradition of illusionistic perspective (think the deep, receding spaces of a Renaissance painting). These recurring motifs – the Open Windows framing vibrant exterior scenes, and even the simple motif of Goldfish in a bowl (a subject he returned to multiple times, exploring not just its contemplative qualities but also the play of light, reflection, and the interplay between interior and exterior space through the transparency of the glass) – became hallmarks of his Nice period. He also engaged with African sculpture during this time, appreciating its simplified, powerful forms, particularly its directness, frontality, and reduction of anatomical detail to essential, rhythmic volumes. This embrace of non-Western aesthetics is a recurring theme in the history of art guide, showing how cross-cultural exchange can spark immense creative inspiration. Travel always seemed to spark something new in me, too; it's almost like a visual reset button, isn't it? That feeling of returning home with a kaleidoscope of new impressions, ready to shake up your usual approach.

- The Nice Period: Sensuality & Decoration (c. 1918-early 1940s): Matisse's time in Nice was more than just a change of scenery; it was an immersion in a different quality of light and a relaxed atmosphere that profoundly shaped his work. You can almost feel the Mediterranean warmth and languid sensuality infusing his depictions of Odalisques, figures like those in Odalisque with Magnolias (1923) or Odalisque with a Tambourine (1926), where figures recline in comfortable interiors adorned with rich textiles and patterns. While these works have sometimes sparked discussion about exoticism or the male gaze, for Matisse, they were primarily vehicles for exploring form, light, and color in a sensual, decorative setting, allowing him to endlessly arrange patterns and figures within confined spaces. This approach is often contextualized within Orientalism, a broader 19th and early 20th-century artistic trend that depicted the cultures of the Middle East and North Africa through a Western, often romanticized or exoticized, lens. The vibrant textiles and patterns that adorn his interiors, and the way light seems to saturate every surface, invite the viewer into a world of relaxed sensory pleasure.Works from this period, like The Red Studio (1911), often feature flatter perspectives, rich decorative patterns, and a continued exploration of interior spaces infused with light and color. This era also saw the emergence of key patrons who recognized Matisse's genius early on. The American writer Gertrude Stein and her family (Leo and Michael Stein, and Michael's wife Sarah) were among the first and most important collectors of his work, acquiring pieces like Woman with a Hat and The Joy of Life. Their Parisian salon became a crucial meeting place for avant-garde artists and intellectuals. Equally significant were the Russian collectors Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, wealthy Moscow businessmen who commissioned major works like The Dance and Music (for Shchukin) and amassed incredible collections of Matisse and other modern masters, now forming the core of collections at the Hermitage and Pushkin museums. Having such supportive patrons, especially during periods when critical reception was still mixed, must have been incredibly validating – a reminder that sometimes you just need a few people who truly get what you're doing. It's a period of refinement and consolidation, but still deeply innovative. It's worth noting that while the revolutionary cut-outs would come to dominate his final years, Matisse continued to paint and draw in Nice well into the late 1930s and early 1940s, creating a period of overlap and transition between these distinct phases. He also experimented with photography during this time, sometimes using it as a reference tool, and his compositions occasionally show a photographic influence in their cropping or perspective. For instance, he might compose a scene with a sharply cropped figure or an asymmetrical balance, mimicking the way a casual photograph might capture a moment.

- The Revolutionary Cut-Outs (c. 1941-1954): Later in life, facing severe ill health due to duodenal cancer and subsequent surgery in 1941, which left him largely confined to a bed or wheelchair, Matisse didn't stop creating – he reinvented his process entirely. The context of World War II also played a role; the war years brought isolation and hardship, and his physical limitations coincided with this period. Turning inward, he began "drawing with scissors," cutting shapes from sheets of paper painted with vibrant gouache by his assistants. He called this technique gouaches découpés (cut-outs). These weren't mere collages; they were a new medium, allowing him to synthesize line, color, and form with stunning simplicity and scale.He essentially found a way to paint without a brush, to draw directly into color. Imagine the intense physical process: Matisse, often in bed or a wheelchair, would wield large shears, directing his assistants (like Lydia Delectorskaya) as they painted large sheets of paper with vibrant gouache. He would then arrange and rearrange these cut shapes on the walls of his studio, pinning them until the composition felt right. The rhythmic snip-snip-snip of scissors through vast sheets of paper, the constant rearrangement of forms on the wall – it was a choreography of creation, often with his assistants playing a vital role in preparing the materials and executing his precise instructions. The cut shapes were sometimes stored in large boxes, ready to be arranged and rearranged. It was a truly collaborative process, with Matisse as the conductor of this vibrant orchestra of color and form. This method allowed him to work on a monumental scale despite his physical limitations. It was a testament to his unwavering creative drive, finding a new method of expression even as his body failed him. It makes you reflect on the incredible resilience and adaptability of the creative spirit – how limitations can sometimes force us to find entirely new, powerful ways to express ourselves. I’ve certainly faced creative blocks where the usual tools just don't work, and sometimes, those frustrations have pushed me to unexpected breakthroughs, discovering new materials or processes I wouldn't have otherwise.

The Jazz portfolio (1947), with its vibrant circus and mythological themes accompanied by his handwritten text, wasn't just a book; it was a manifesto of this new technique. He titled it Jazz not because it depicted musicians, but because he felt the cut-outs had a rhythmic, improvisational quality, much like the energy of jazz music. Other major examples from this period include the large-scale, abstract The Snail (1953), where colored shapes spiral outwards, and Memory of Oceania (1953), evoking sensations of his travels through simplified forms. The iconic Blue Nudes series (1952), and the designs for the Rosary Chapel (Chapel of the Rosary / Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence) in Vence represent the triumphant culmination of his lifelong quest for expression. For the Chapel, he designed nearly everything, from the stark black-and-white St. Dominic panel and ceramic murals to the stunning Tree of Life stained-glass window design, which bathes the interior in blue, green, and yellow light, and even the priests' vestments. He undertook this monumental project late in life as a thank you to the Dominican nun, Sister Jacques-Marie, who had nursed him through illness. It’s a powerful reminder of finding creative inspiration even amidst limitations. This wasn't a lesser form of art due to his infirmity; it was arguably the purest distillation of his ideas about color and form.

Matisse's Three-Dimensional Explorations: Sculpture as a Dialogue with Painting

While less famous than his paintings, Matisse's sculpture was a crucial part of his artistic exploration, often working through formal problems in three dimensions that would inform his two-dimensional work. He physically wrestled with volume, mass, and the reduction of the figure, often working in bronze, clay, and plaster. This process directly fed into the simplified forms and bold lines of his paintings and later cut-outs. It's almost jarring to think of the master of vibrant color also meticulously chipping away at stone or molding clay, yet his sculptural output is a testament to his holistic vision. While sculptors like Rodin emphasized narrative and emotional intensity in individual works (and indeed, Matisse briefly studied with Auguste Rodin in 1900, though their approaches quickly diverged), Matisse's sculptural journey, particularly in his series, was about a methodical, almost scientific, investigation into form and its progressive simplification. His engagement with African sculpture, mentioned earlier, with its emphasis on simplified, powerful forms and reduction of anatomical detail, profoundly reinforced his own sculptural explorations and his move towards abstraction in his painted figures, seeking a universal quality rather than mere representation.

Key works include The Serf (c. 1900-1904), a powerful, roughly textured figure showing early influences but already moving towards expressive distortion. The series of five portrait heads, Jeannette (I-V) (1910-1913), shows a fascinating progression from a relatively naturalistic representation to increasingly abstract and fragmented forms. This series, in particular, was a deep investigation into the human face, exploring how form could be simplified and abstracted while retaining its expressive power. Perhaps his most monumental sculptural achievement is The Back Series (I-IV), four large bronze reliefs of a female nude back, created over two decades (c. 1909-1930). Each iteration becomes progressively more simplified, abstract, and monumental, tracing his evolving understanding of form and reduction. It's like watching his thought process solidify in bronze – a real testament to his dedication to exploring an idea fully. Seeing that clear, multi-decade visual record of an artist's evolving thought process in solid bronze is truly awe-inspiring. You can see how the simplified, monumental forms in The Back Series relate to the bold, curvilinear shapes he would later explore in his cut-outs, demonstrating a clear dialogue between his work in different media and how his sculptural explorations directly informed his later two-dimensional innovations.

Beyond the Canvas: Matisse's Multidisciplinary Art

While painting, sculpture, drawing, and prints are his most recognized forms, Matisse also ventured into other media, demonstrating his holistic approach to art and design. Beyond the ceramics and stained glass for the Vence Chapel, he designed tapestries, such as Polynesia, The Sky and Polynesia, The Sea (both 1946), and worked on projects involving ceramics and textiles throughout his career, particularly later in life. He also famously designed costumes and sets for the Ballets Russes production of Le Chant du Rossignol (The Song of the Nightingale) in 1920, applying his vibrant palette and simplified forms to the stage. These designs, lauded for their innovative use of color and abstract forms, significantly influenced contemporary stage design by moving away from literal representation towards a more expressive, symbolic visual language. Furthermore, Matisse undertook significant book illustration projects beyond Jazz, illustrating works like Stéphane Mallarmé's Poésies (1932) with elegant etchings and Henry de Montherlant's Pasiphaé (1944) with powerful linocuts. These explorations allowed him to apply his principles of color, line, and form to functional or performative objects, further blurring the lines between fine art and applied arts. It's truly admirable how he was willing to apply his vision across such diverse fields – a real challenge and inspiration for artists today. It speaks to a profound artistic curiosity and a refusal to be confined by labels. This willingness to jump between disciplines and apply a cohesive aesthetic vision is something I deeply admire, and frankly, struggle with myself – how do you make all your different creative urges sing in harmony?

Decoding Matisse: Key Aspects of His Art

Ready to peek behind the curtain? What are the essential ingredients that make a Matisse a Matisse? Let's break down the core elements that define his unique vision.

- The Power of Color: This is perhaps his most defining feature. Matisse liberated color from simply describing reality. For him, color was expressive, conveying emotion, creating light, and structuring the composition. He used bold, often unexpected hues side-by-side to create harmony or tension. He wasn't painting a red room; he was painting the feeling of red. Think about your favorite color – what feeling does it evoke for you? Matisse understood and harnessed that power on the canvas. As he stated in his influential "Notes of a Painter" (1908), "The chief aim of color should be to serve expression as well as possible." Understanding this is key to reading his paintings. Think of how a musician uses notes and chords to create feeling; Matisse used color in a similar way, creating a visual symphony. He even explored the power of black, not as an absence of color, but as a color in its own right, capable of luminosity and structure. Look at a work like The Painter's Family (1911), where areas of deep black aren't voids but active, vibrant elements that push and pull against the other colors, giving the composition structure and depth. He also used black in his cut-outs, like the Blue Nudes, where the stark black background makes the vibrant blue figures pop with incredible intensity, demonstrating its power to enhance other colors and define space. As an artist, one often finds themselves wrestling with color, trying to push it beyond mere representation, to make it feel something. It’s a constant dance between intuition and control, and seeing how Matisse fearlessly embraced color as pure emotion is a profound lesson.

- The Eloquence of Line: Matisse's line is deceptively simple, fluid, and incredibly descriptive. His mastery wasn't just in painting; he was a prolific draughtsman and printmaker, able to capture the essence of a figure or object with an extraordinary economy of means – making every single line count. Whether in drawings, prints, or paintings, he could capture the essence of a figure or object with just a few graceful curves. His cut-outs are the ultimate expression of this – line and shape becoming one. Beyond the famous Jazz portfolio, he produced numerous series of drawings, like the Themes and Variations (1941-1942), where he explored subjects through repeated, subtly different line drawings, revealing his process of refinement. A specific example from this series, like Theme A, Variation 1 (a portrait of a woman), shows his ability to capture form and character with minimal, elegant lines. He also created hundreds of etchings, lithographs, and linocuts, often focusing on portraits, nudes, and still lifes, showcasing his linear skill in different graphic mediums. A well-known example is his lithograph series of Odalisques from the 1920s, where his fluid line captures the sensuality and form of the reclining figures with apparent ease. These often reveal the rigorous underpinning of his seemingly effortless painted lines – you see the searching, the refinement, the absolute control behind the apparent ease. It looks so simple, but try drawing something complex with just a few lines yourself – you'll quickly appreciate the difficulty of achieving such apparent fluidity and descriptive power. I once spent an entire week trying to capture the essence of a bird with just three lines. The sheer frustration, and then the quiet triumph when it finally clicked, gave me an entirely new appreciation for Matisse’s deceptive simplicity.

- Seeking Serenity and Joy: Matisse often spoke of wanting his art to be calming, a source of pleasure and tranquility for the viewer. "What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter," he wrote in "Notes of a Painter" (1908). This pursuit of joy and equilibrium feels deeply connected to the "good armchair" idea – art that provides a sense of comfort and uplift, a visual respite from the world's complexities, and is palpable in his work, especially in the vibrant harmony of his later pieces. It's a quality many seek when looking to buy art for their homes. For me, the serene figures in The Dance or the calming palette of Memory of Oceania often bring this quiet uplift. This philosophy felt particularly poignant in the early 20th century, a time marked by global conflicts and seismic social shifts. Matisse’s insistence on art as a haven, a place of peace and restorative beauty, was a radical counterpoint to the anxiety of his era, and perhaps, our own. Can you think of a piece of art, any art, that has brought you a sense of comfort or uplift?

- Flattening Space, Embracing Decoration: Matisse challenged traditional perspective. He often flattened the picture plane, emphasizing surface patterns and decorative elements. This focus on surface, pattern, and flatness was a profound break from the Western tradition of illusionistic perspective (think the deep, receding spaces of a Renaissance painting), where artists aimed to create the illusion of a window into another world. Influenced by non-Western art forms, as explored previously, he saw the potential for pattern and color to structure a composition as effectively as realistic depth, proving that decoration could be a primary element of a serious artwork. This links strongly to broader trends in modern art movements. Look around your own space right now – notice the patterns on fabrics, the textures on surfaces. Matisse brought that same appreciation for the visual world as surface into his paintings. In my own abstract compositions, I often find myself playing with that tension between suggesting depth and celebrating the flat surface of the canvas. It's a fascinating challenge, making a two-dimensional plane feel both expansive and utterly present.

Matisse's Masterpieces: A Few Icons

Okay, let's talk about the heavy hitters – the works you absolutely need to know. Trying to pick Matisse's "most famous" works is tough, as his output was vast and influential across many periods. But here are just some iconic examples that showcase his innovation and enduring appeal.

Work | Year(s) | Key Significance | Primary Museum/Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Woman with a Hat | 1905 | A key Fauvist work; scandalous at the time for its wild, non-naturalistic color. Purchased by Gertrude Stein. | San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) |

| The Joy of Life | 1905-1906 | Ambitious scale, radical color, idyllic subject matter. Also acquired by the Steins. | Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia |

| The Dance | 1910 | Iconic depiction of primal energy and movement through simplified forms & color. Commissioned by Sergei Shchukin. | State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg |

| The Red Studio | 1911 | Immersive interior, flattening space, using bold color to unify the scene. Features many of Matisse's own earlier works. | Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York |

| The Painter's Family | 1911 | A complex interior scene showcasing his family, notable for its bold use of black as a structural and expressive color. | State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg |

| Jazz portfolio | 1947 | Seminal example of the cut-out technique, combining vibrant images and text, named for its improvisational feel. | Various collections, including MoMA, Tate Modern, Bibliothèque Nationale de France |

| Blue Nude series | c. 1952 | Pinnacle of the cut-out technique; simplified, powerful female forms created from cut blue paper. | Various collections, including Centre Pompidou, MoMA, Philadelphia Museum of Art |

| Rosary Chapel (Vence) | 1948-1951 | A complete environment designed by Matisse – architecture, stained glass (like the Tree of Life window), ceramic murals (including the St. Dominic panel), altar, crucifix, candlesticks, and even priest's vestments. A testament to his holistic artistic vision. Also known as Chapel of the Rosary or Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence. | Vence, France |

| The Snail | 1953 | Large-scale cut-out demonstrating pure abstraction through arrangements of colored paper shapes, evoking a spiral form. | Tate Modern, London |

| The Back Series (I-IV) | c. 1909-1930 | Monumental series of four bronze reliefs showing the progressive abstraction of the female back over two decades, demonstrating the dialogue between his sculpture and painting. | Tate Modern, London; Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York; Philadelphia Museum of Art (variations) |

Have you ever seen The Dance in person? It's electric! The sheer exuberance of The Dance is infectious; it's impossible not to feel a surge of pure, unadulterated joy when I see it. Looking at The Red Studio makes me wonder what my own creative space would look like if I painted it entirely in one color. The intensity of that specific blue against the stark background in the Blue Nudes is breathtaking. If you ever get the chance to stand before a large Matisse cut-out, like The Snail, take a moment. The sheer scale, the vibrant color, the seemingly simple shapes – it's an experience that photos can't quite capture. It feels both monumental and incredibly light, a testament to finding joy in pure form. When approaching a large-scale Matisse, I find it helps to first take it all in from a distance, letting the colors and forms wash over you as a whole. Then, gradually move closer to appreciate the incredible precision of the cuts, the textures of the gouache, and the subtle interplay of shapes.

Exploring these works in top museums for modern art offers an incredible experience. Major collections reside at MoMA (New York), the State Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg), the Centre Pompidou (Paris), and the Tate Modern (London), among others. Don't forget the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, which holds an unparalleled collection of Matisse's work, particularly from his Nice period, offering a unique opportunity to see many masterpieces together. Also, the Matisse Museum in Nice, and the Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, his birthplace, houses a significant collection donated by the artist and his family, offering unique insights into his origins and development. These are distinct institutions, each offering a different perspective on his vast oeuvre.

Matisse in the Art Market

It's a strange thought, isn't it? The quiet act of creation in a studio, transformed into multi-million dollar transactions decades later. While the purity of artistic pursuit feels miles away from the clamor of the auction house, understanding Matisse's market status highlights his enduring importance and desirability – a testament to the power of his vision. It probably goes without saying, but owning an original Matisse painting is the domain of major museums and ultra-high-net-worth collectors. His works command enormous prices at auction, often selling for tens of millions of dollars, firmly placing him in the blue-chip category of the art market. For instance, his work Nu couché (Reclining Nude) sold for a staggering $170.4 million in 2015, demonstrating the immense value placed on his masterpieces. Factors like the period, subject matter, size, condition, and provenance (like having been owned by Shchukin or the Steins) heavily influence value, as explored in understanding art prices. Sadly, my own artistic aspirations don't currently extend to purchasing a Matisse, but one can dream, right? However, his prolific output as a printmaker means that original Matisse lithographs, etchings, and linocuts are somewhat more accessible, though still significant investments. You can learn more about the differences between prints versus paintings and the world of buying art prints elsewhere on our site. For most of us, experiencing Matisse means visiting museums or appreciating high-quality reproductions, but understanding his market status highlights his enduring importance and desirability – a testament to the power of his vision. Thinking about art as an investment? Matisse is a case study in long-term value appreciation, though passion should always be the primary driver when you buy art. It’s a fascinating, sometimes bewildering, tension between the purity of artistic pursuit and the realities of commercial value. A disconnect, perhaps, but also a measure of how deeply his vision resonated and continues to resonate.

Matisse's Lasting Impact: Influence on Modern Art

Matisse's influence on the course of 20th-century art is immense. It's hard to overstate his importance. His legacy can be seen across various fields:

- Painting: His radical use of expressive color directly influenced countless artists, paving the way for Abstract Expressionism (think Mark Rothko and his fields of color, who explicitly acknowledged Matisse's impact on his own journey towards color as the primary vehicle of emotion) and Color Field painting. American painters like Milton Avery, with his simplified forms and harmonious color palettes, clearly absorbed Matisse's lessons. He showed that color could be the primary subject of a painting. Beyond color, his emphasis on decorative elements and patterned surfaces also left a significant mark, influencing artists who embraced ornamentation and the flatness of the picture plane. More recent artists continue to draw inspiration from his bold use of color and pattern; you can see echoes in the work of contemporary painters who prioritize vibrant palettes, decorative elements, and expressive simplicity. As an artist, I often find myself revisiting Matisse’s approach to color – how he makes a single hue vibrate with life or how he orchestrates an entire composition around seemingly clashing tones. It’s a constant well of inspiration, reminding me that the power of color is boundless.

- Sculpture: While perhaps less direct than his painting influence, his sculptural work, particularly the progressive abstraction seen in The Back Series, offered a model for artists exploring form and volume, contributing to the broader dialogue around modern sculpture.

- Graphic Arts & Design: As a leader of Fauvism, he helped usher in one of the first major avant-garde movements of the 20th century, signaling a definitive break from artistic tradition. His prolific output in drawing and printmaking, and especially the late-career invention of the gouaches découpés (cut-outs), demonstrated that profound artistic statements could be made with humble materials and direct methods. The cut-outs, in particular, had a significant impact on collage art, graphic design, and even decorative arts, influencing everything from textile patterns to album covers and children's book illustration, thanks to their simplified forms and bold color blocking. His vivid palette and bold, simplified forms have echoed far beyond the gallery, influencing graphic designers with his use of flat color and strong outlines, fashion houses with his organic, repeating motifs, and interior decorators who embraced his vibrant color blocking and decorative flair. The Californian painter Richard Diebenkorn, particularly in his figurative and Ocean Park series, demonstrates a profound engagement with Matisse's sense of structure, light, and color within simplified compositions, showing how his influence spanned different media and continents.

Matisse and His Contemporaries: A Rivalry Forged in Respect

You can't really talk about Matisse's place in modern art without mentioning Pablo Picasso. Their relationship was one of the great artistic dialogues – and rivalries – of the century. They were friends, yes, but also competitors, constantly watching, reacting to, and pushing each other. Picasso, seeing Matisse's Fauvist breakthroughs, responded with the revolutionary Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, pushing towards Cubism. Matisse, in turn, absorbed Cubism's lessons about structure, though always bending them to his own ends.

I find their dynamic fascinating. They were like the North and South poles of modern painting: Matisse seeking harmony, sensuality, and colour; Picasso exploring fragmentation, intellectual rigor, and often darker themes. Yet, they deeply respected each other. Picasso reportedly said, "All things considered, there is only Matisse," and acknowledged Matisse's mastery of color. Matisse, for his part, recognized Picasso's relentless innovation. Their back-and-forth spurred both to greater heights, shaping the very landscape of art in the 20th century. It's kind of amusing, isn't it, to imagine these two giants constantly trying to one-up each other, their competitive energy fueling some of the most important art of the era? It makes me think about the role of friendly rivalry in my own creative life – that subtle push, the quiet challenge from another artist’s success that makes you sharpen my own tools and dig a little deeper. They remain benchmarks against which many top artists ever are measured.

While the Matisse-Picasso relationship looms large, Matisse also maintained important connections with other artists. His friendship with Pierre Bonnard, another master of color and intimate interior scenes, is particularly noteworthy. Though stylistically different – Bonnard's color was perhaps more shimmering and atmospheric, Matisse's bolder and more structural – they shared a deep mutual respect and engaged in thoughtful correspondence about their work. They both explored domestic subjects, light, and the expressive potential of color, albeit arriving at different solutions. It’s a quieter dialogue than the one with Picasso, perhaps, but it highlights the rich network of artistic exchange happening at the time and reminds us that not all influential artistic relationships are defined by intense rivalry; sometimes, mutual admiration and shared interests are just as powerful. Beyond these close bonds, he also participated in key exhibitions and groups that shaped the Parisian avant-garde, interacting with figures across various movements, which further cemented his pivotal position. His friendship with other early modernists, even those who took different paths, speaks to a collegial spirit that often gets overlooked in the narrative of individual genius. It makes me wonder about the quiet collaborations and supportive friendships among artists today that might never make the headlines but are crucial to their growth. Sometimes, the most profound influence comes from a silent understanding, a shared love for the craft.

He remains one of the top artists ever discussed in the history of art guide.

Why Matisse Still Matters (Maybe More Than Ever?)

So, why spend time with Matisse today? In a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming, his dedication to finding joy, balance, and serenity through art feels incredibly relevant. His work isn't about escaping reality, but about transforming it through the power of seeing, color, and line. It reminds us of the pleasure in simple forms, the emotional resonance of color, and the possibility of finding harmony even in unexpected combinations.

His journey, from law student to artistic revolutionary, also speaks to the power of following your passion, even when it seems unconventional. It's a reminder that the "good armchair" he sought wasn't about passive comfort, but about an active engagement with beauty that provides solace and uplift. For me, as an artist, his unwavering dedication to his vision, even when it was misunderstood or when his body failed him, is a profound source of personal inspiration. It reminds me, as an artist striving to find my own voice and overcome creative blocks, that the act of creation itself can be a source of immense joy and resilience, a personal paradise you can carry with you, scissors and paper in hand, no matter the circumstances.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Got quick questions? Here are some common ones:

- What are the key aspects of Henri Matisse's art? Matisse's art is defined by his revolutionary use of expressive color (including black), his fluid and simplified line, his focus on joy and serenity, the flattening of perspective, his embrace of decorative patterns (influenced by non-Western art and Orientalism), his significant sculpture, his late-career gouaches découpés (cut-outs), and his work in other media like tapestries, ceramics, textiles, and costume design.

- What was Henri Matisse's philosophy or main aim in art? Matisse famously sought to create an "art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter." He wanted his art to be like a "good armchair" – a source of comfort, tranquility, and visual pleasure for the viewer, transforming reality through harmony of color and form.

- What is the significance of Matisse's 'good armchair' quote? The "good armchair" quote signifies Matisse's desire for his art to provide viewers with comfort, relaxation, and mental repose, acting as a soothing visual experience that offers a retreat from daily anxieties, rather than provoking or disturbing. It emphasizes art's role as a source of peace and harmony.

- What are the most famous works by Henri Matisse? Some iconic works include Woman with a Hat, The Joy of Life, The Dance, The Red Studio, The Painter's Family, the Jazz portfolio, the Blue Nudes series, sculptures like The Back Series, and his designs for the Rosary Chapel (Chapel of the Rosary / Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence) in Vence.

- What were Henri Matisse's main artistic techniques and innovations? His innovations include co-founding Fauvism (bold, non-naturalistic color), developing a unique approach to simplified line and form through painting and mastery of drawing, absorbing influences like Cubism and Islamic art, contributing significantly to modern sculpture (often in bronze, clay, and plaster), and inventing the gouaches découpés (cut-outs) technique, spurred by his severe illness in 1941.

- How did Henri Matisse influence modern art? Matisse profoundly influenced modern art by liberating color, impacting movements like Abstract Expressionism (Mark Rothko) and Color Field painting. His simplification of form, embrace of decoration (especially through bold color blocking and organic patterns), sculptural work, and innovation (cut-outs) impacted generations of artists like Milton Avery and Richard Diebenkorn. His influence is also seen in graphic design, fashion, textiles, and children's book illustration, and he mentored artists at the Académie Matisse.

- What are the main periods of Henri Matisse's artistic career? His career includes Early Years (learning, c. 1890-1904), the Fauvist period (intense color, c. 1905-1908), Experimentation and the Nice Period (refinement, travel influences, patrons, decorative focus, sculpture, c. 1908-early 1940s), and the Cut-Outs period (late-career innovation, c. 1941-1954).

- Where can I see major works by Henri Matisse? Major collections are held at MoMA (New York), the State Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg), the Centre Pompidou (Paris), the Tate Modern (London), the Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia), the Matisse Museum in Nice, and the Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis. See our guide to the best museums for modern art.

- Did Matisse only paint? No, he was also a highly accomplished sculptor (e.g., The Back Series, often in bronze, clay, and plaster), draughtsman (e.g., Themes and Variations), printmaker (etchings, lithographs, linocuts), book illustrator (e.g., Mallarmé's Poésies, Montherlant's Pasiphaé), and pioneered the gouaches découpés (cut-outs) technique. He also worked in textiles (e.g., Polynesia, The Sky) and costume/set design, notably for the Ballets Russes.

- Who were some of the key artists or movements that influenced Matisse's early work? In his early years, Matisse was influenced by [Impressionism] and [Post-Impressionism], studying works by artists like [Van Gogh], Cézanne, and Gauguin. He also briefly studied with Auguste Rodin and was taught by the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, who encouraged imaginative use of color.

- How did Matisse's personal life influence his art? Matisse's personal life profoundly influenced his art through the presence of his family, particularly his wife Amélie Parayre, who frequently modeled for him. Later, his assistant Lydia Delectorskaya became a crucial model and collaborator, instrumental in the creation of his cut-outs. His severe illness in 1941 also directly led to the invention of the cut-out technique, showcasing his resilience and adaptability.

- Who coined the term "Fauves"? The art critic Louis Vauxcelles coined the term in 1905, intending it as an insult, after seeing the brightly colored works at the Salon d'Automne.

- Who was Ambroise Vollard? Ambroise Vollard was an influential art dealer who played a significant role in promoting many modern artists, including Matisse, giving him his first solo exhibition and purchasing many of his early works, helping to establish his reputation.

- What was the Académie Matisse? The Académie Matisse (1908-1911) was a free art school in Paris run by Matisse himself, where he mentored a new generation of artists and shared his radical approaches to color and form, highlighting his role as a teacher and theorist.