What is Art? Ultimate Guide to Definition, Meaning, History & Key Examples

Explore 'what is art?' Definitive guide covering definitions, philosophies (Western/Non-Western), history, movements (Cubism, Surrealism), key works, art world roles, controversies & appreciation.

What is Art? Exploring the Definition and Meaning

Art stands as a cornerstone of human culture, yet its precise definition continues to spark debate and diverse interpretations. At its essence, art functions as a fundamental form of expression, enabling individuals to convey ideas, emotions, and perceptions through a diverse array of mediums. These mediums span traditional forms like painting and sculpture to more contemporary expressions encompassing digital art, performance, and even everyday objects presented in a certain context. Trying to pin down exactly 'what is art' feels a bit like trying to catch smoke – just when you think you have it, it shifts. But maybe that elusiveness is part of its magic?

Major Categories of Art

While the boundaries can be fluid, art is often categorized into several main disciplines, each employing distinct mediums and techniques:

- Visual Arts: Primarily appeal to the sense of sight. This broad category includes:

- Painting: Applying pigment to surfaces like canvas or wood.

- Sculpture: Creating three-dimensional forms from materials like stone, metal, clay, or wood.

- Drawing: Using tools like pencils, charcoal, or ink on paper. (Some incredible famous sketch artists today continue to push this medium).

- Photography: Capturing images using light-sensitive materials or digital sensors.

- Printmaking: Creating artworks by transferring ink from a matrix (like woodblock or metal plate) onto paper.

- Architecture: Designing and constructing buildings, often considered both an art and a science.

- Film and Video Art: Using moving images and sound.

- Digital Art: Art created using digital technologies.

- Performing Arts: Involve performance before an audience. Examples include:

- Music: Organizing sound in time.

- Dance: Using body movement, often rhythmically and to music.

- Theater: Collaborative form involving live performers presenting real or imagined events.

- Performance Art: Artworks created through actions performed by the artist or other participants. Think of the intense commitment seen in works by artists like Marina Abramović.

- Literary Arts: Employing language as the primary medium, including poetry, fiction, and non-fiction writing. Think of art with words.

- Applied Arts: Incorporating design and aesthetics into objects of function and everyday use, such as industrial design, graphic design, fashion design, and interior design. Exploring how to incorporate art into spaces like your kitchen (How to Decorate a Kitchen) or living room (How to Decorate Your Living Room) falls under this intersection.

Distinguishing Art from Craft, Design, and More

The lines between art, craft, and design are often debated and can be blurry. I sometimes struggle with this myself – is a beautifully made object automatically art? Or does intention matter more? However, some general distinctions are frequently made:

- Art: Often emphasizes expression, concept, and aesthetics over practical function. Its primary goal might be to evoke emotion, provoke thought, or explore beauty. Originality and uniqueness are highly valued.

- Craft: Typically involves skilled making by hand, often focused on specific materials and traditional techniques (e.g., pottery, weaving, woodworking). While aesthetically pleasing, craft objects often retain a functional purpose or are rooted in tradition. Think of contemporary figures like ceramicist Edmund de Waal or glass artist Dale Chihuly, whose works often blur the line towards fine art installation but remain deeply rooted in craft processes.

- Design: Primarily concerned with functionality and problem-solving. Design seeks to create solutions (e.g., a user-friendly website, an ergonomic chair) where aesthetics serve the purpose of enhancing usability and appeal within specific constraints. Think of the iconic furniture of Charles and Ray Eames, which blended artistic form with innovative manufacturing and ergonomic principles.

It's important to note these are not rigid categories, and many works successfully blend elements of all three. Think of the Bauhaus movement in early 20th-century Germany, which famously aimed to unify art, craft, and technology. They believed good design should be aesthetically pleasing and functional, accessible to all. Similarly, figures like William Morris in the Arts and Crafts movement championed handcrafted quality and beauty in everyday objects, blurring the lines between the artisan and the artist.

Folk Art: Community Traditions

Distinct from Outsider Art, Folk Art encompasses artistic expressions rooted in specific cultural communities. It often reflects shared traditions, values, and aesthetics passed down through generations, frequently outside formal academic structures. Unlike the highly individualistic visions typical of Outsider Art, Folk Art emphasizes community identity and traditional forms, whether it's Amish quilts, Mexican Dia de Muertos sugar skulls, or Scandinavian wood carving. It's often functional or decorative, celebrating cultural heritage rather than purely individual expression.

Kitsch: The Art of Bad Taste?

Then there's Kitsch. Ah, kitsch... that category we often love to hate, or maybe secretly enjoy? Generally, kitsch refers to objects considered to be in poor taste due to excessive garishness or sentimentality, but sometimes appreciated in an ironic way. Think garden gnomes, velvet Elvis paintings, or souvenir snow globes. Philosopher Theodor Adorno critiqued kitsch as a formulaic, mass-produced imitation of genuine emotion, designed for easy consumption. While often positioned against 'serious' art, the line can blur, and artists sometimes intentionally incorporate kitsch elements to comment on popular culture and taste (think Jeff Koons).

The Unique Space of Outsider Art

It's also worth mentioning Outsider Art, or Art Brut (a term coined by Jean Dubuffet). This refers to art created by self-taught individuals, often outside the established art world structures – people perhaps living in isolation, in psychiatric hospitals, or otherwise disconnected from mainstream culture. Their work frequently possesses a raw, unconventional power, driven by intense personal visions rather than academic training or market trends. Think of artists like Henry Darger or Adolf Wölfli. While distinct from the established art scene, Outsider Art challenges conventional definitions and raises questions about who gets to define what art is. You can explore some fascinating best outsider artists here.

A defining characteristic of art lies in its inherent subjectivity. The perception and interpretation of art can vary significantly from one individual to another. What one person recognizes and appreciates as art, another might not consider as such. This subjective nature is not a weakness but rather a crucial aspect that fosters engagement and intellectual exploration. It invites personal interaction with the artwork and encourages dialogue and the exchange of perspectives.

Philosophical Perspectives on Art

Throughout history, philosophers have proposed various theories to define or understand the nature of art. It's like everyone wants a neat box, but art keeps spilling out. Maybe the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was onto something with his idea of 'family resemblance' – suggesting that things we call 'art' might share overlapping characteristics, like members of a family, rather than a single defining feature. It feels less like forcing a definition and more like acknowledging a network of connections.

- Mimetic Theory (Representation): Originating with Plato and Aristotle, this view holds that art is essentially an imitation or representation of reality. A good artwork accurately mirrors the world. Think of the incredible realism achieved in Renaissance paintings like Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, striving to capture the likeness of the subject and the natural world.

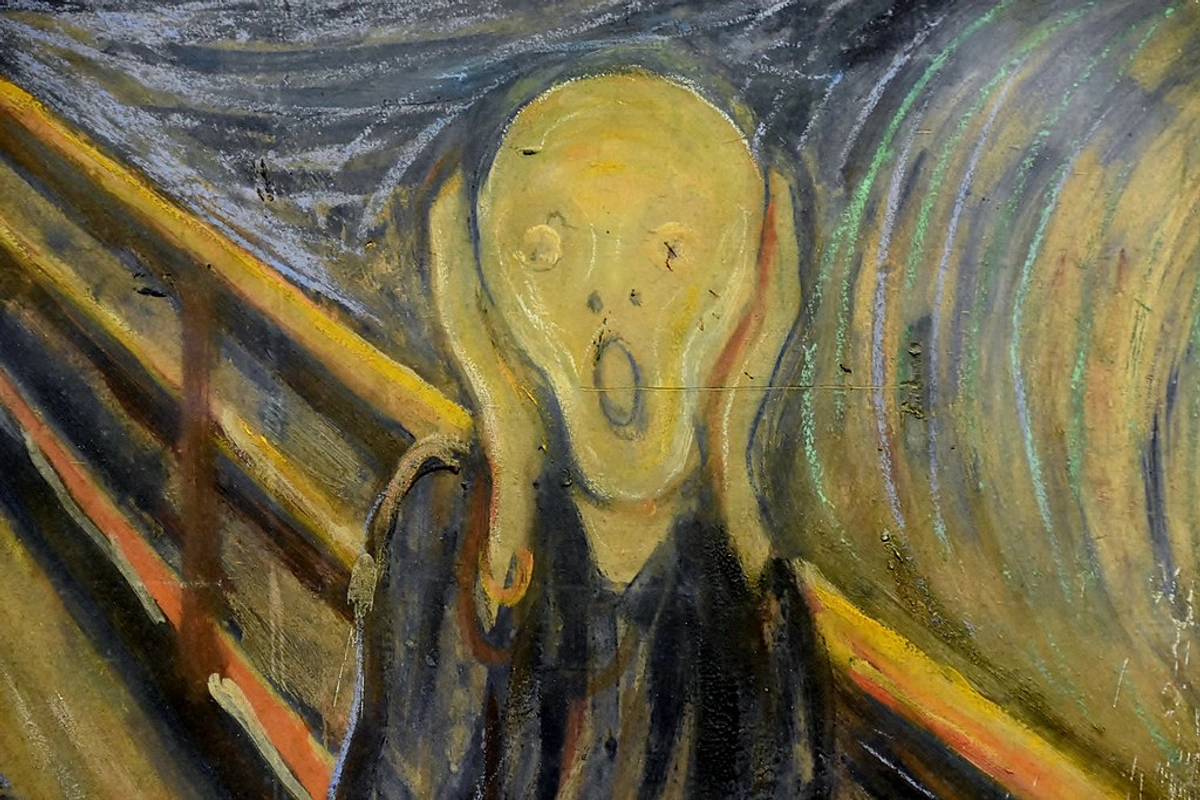

- Expressionist Theory: Popularized during the Romantic era and championed by thinkers like Leo Tolstoy and R.G. Collingwood, this theory posits that art's primary function is to express the inner emotions, feelings, or state of mind of the artist. The success of the art lies in its ability to convey these feelings authentically. Edvard Munch's The Scream is a powerful visual example of this theory in action, communicating intense psychological anguish. Dive deeper into this with the ultimate guide to Expressionism.

- Formalism: This perspective, prominent in the early 20th century (particularly relevant to understanding modern art) and heavily influenced by critics like Clive Bell and Roger Fry, argues that the value of art lies in its formal qualities – elements like line, shape, color, texture, and composition – rather than its subject matter or emotional content. Bell coined the term "Significant Form" to describe the combination of lines and colors that stir aesthetic emotions. Think of appreciating a Jackson Pollock drip painting not for what it represents, but for the energy of the lines, the balance of colors, the texture of the paint itself. Art should be appreciated for its structure and visual relationships. The influential American critic Clement Greenberg was a major proponent of formalism, especially regarding Abstract Expressionism.

- Institutional Theory: A more contemporary view, developed by philosophers like George Dickie and Arthur Danto (inspired by works like Marcel Duchamp's Fountain – a urinal presented as art in 1917), suggesting that something becomes art when it is recognized and designated as such by the "art world" – a complex network of artists, critics, curators, gallerists, and audiences. Context determines status. If it's in a gallery and the right people say it's art... well, then it is. It sounds cynical, but it acknowledges the social structures at play.

- Aesthetic Theory: Focuses on the capacity of art to produce an aesthetic experience – a particular kind of pleasure or perception derived from appreciating beauty, form, or sensory qualities. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant explored the idea of "disinterested judgment," suggesting we appreciate true beauty for its own sake, separate from any personal desire or practical use. American philosopher Monroe Beardsley further developed this, defining aesthetic experience by features like focused attention, felt freedom, detachment from ordinary concerns, and a sense of integration or wholeness evoked by the artwork.

These theories are not mutually exclusive and often overlap, reflecting the complexity of defining art definitively. Thinkers like Hegel also contributed significantly, viewing art as a crucial stage in the development of human spirit and consciousness.

Beyond Western Perspectives

It's crucial to remember that these philosophical frameworks largely stem from Western traditions. Many non-Western cultures have distinct and equally rich philosophies of art and aesthetics. For example:

- Japanese Aesthetics: Concepts like Wabi-Sabi embrace imperfection, transience, and understated beauty found in natural materials and processes. It values the patina of age and the asymmetry of the handmade. Think of traditional tea ceremony ware, heavily influenced by masters like Sen no Rikyū, or Zen gardens. Yūgen points towards a subtle, profound grace, an awareness of the universe that triggers emotional responses too deep for words.

- Islamic Art Principles: Often emphasizes intricate geometric patterns (like the stunning tilework found in the Alhambra palace in Spain), calligraphy, and vegetal designs (arabesques), reflecting concepts of unity, order, and the infinite nature of God. Representation of human figures is often avoided in religious contexts, leading to highly developed abstract and decorative forms.

- Indigenous Art Principles: Vary widely across cultures but often deeply intertwine art with spirituality, storytelling, connection to land, and community identity. Examples include:

- Aboriginal Australian Dreamtime paintings: Intricate works, like those by Emily Kame Kngwarreye or the Papunya Tula artists, that map ancestral journeys and spiritual beliefs onto the land.

- Native American totem poles: Monumental carvings conveying lineage, stories, and crests.

- African Art Forms: Diverse traditions like the ancient Nok Terracotta sculptures from Nigeria or the elaborate Benin Bronzes, which served royal, ceremonial, and historical functions. Art isn't just an object but a living part of cultural practice and knowledge transmission.

- Latin American Art: Rich traditions include the vibrant Mexican Muralism movement, featuring artists like Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros using large-scale public works for social and political commentary, and the intensely personal and symbolic work of artists like Frida Kahlo.

Acknowledging these diverse viewpoints helps us understand that the very question "what is art?" and the frameworks used to answer it are culturally situated. The meaning of art isn't universal in its specifics, even if the creative impulse might be.

The Psychology Behind Art

Why do we even make and respond to art? The psychology of art perception and creation offers some fascinating angles. Evolutionary psychologists suggest that our attraction to certain patterns, landscapes (like savanna-like environments offering prospect and refuge), or skilled craftsmanship might have ancient roots tied to survival and mate selection. Cognitive science explores how our brains process visual information, respond to color and form (Gestalt principles), and find pleasure in symmetry, complexity, or the resolution of ambiguity. Neuroscience investigates the brain activity associated with aesthetic experiences, often involving reward pathways and emotional centers. It seems our deep-seated need to create and appreciate art is wired into our very being.

Broader Purposes of Art

Beyond its role in personal expression, art often serves a multitude of broader societal purposes. It can act as a powerful tool for communication, conveying information and narratives across cultures and time periods. Art can also function as a catalyst for social commentary, prompting reflection and discussion on societal norms, values, and issues – critic John Berger's Ways of Seeing brilliantly explored how images shape our understanding of the world, particularly regarding gender and class. The murals of Diego Rivera, for instance, vividly depicted social struggles and celebrated indigenous culture. Furthermore, art plays a vital role in preserving cultural heritage, embodying the traditions, beliefs, and histories of different communities.

Additionally, art can simply provide entertainment and aesthetic pleasure, enriching our lives through beauty and creativity. The line between "Art vs. Entertainment" can be fuzzy. Is a blockbuster movie art? Is a pop song? Often, 'high art' is seen as challenging and complex, while entertainment aims for broad appeal and enjoyment. But I think great art can certainly be entertaining, and great entertainment can possess artistic merit. Maybe it's more of a spectrum than a strict divide?

Beyond these, art also finds practical application in fields like Art Therapy, where the creative process is used to improve mental and emotional well-being, and Art Education, which fosters creativity, critical thinking, and cultural understanding in learners of all ages.

Art, Power, and Control: Censorship and Iconoclasm

Because art can be so powerful in communicating ideas and challenging norms, it has often been subject to censorship (the suppression of art considered objectionable) and iconoclasm (the destruction of images, often for religious or political reasons). Throughout history, regimes have banned artworks deemed decadent, subversive, or blasphemous (think of the Nazi condemnation of 'Degenerate Art'). Religious conflicts have led to the destruction of statues and icons (like during the Byzantine Iconoclasm or the Reformation). Even today, debates rage over controversial artworks, triggering calls for removal or defunding, highlighting the ongoing tension between artistic freedom and societal sensitivities.

The Evolving Definition of Art

The concept of "art" itself has evolved significantly throughout history. Trying to apply today's art definition to the past doesn't always work neatly.

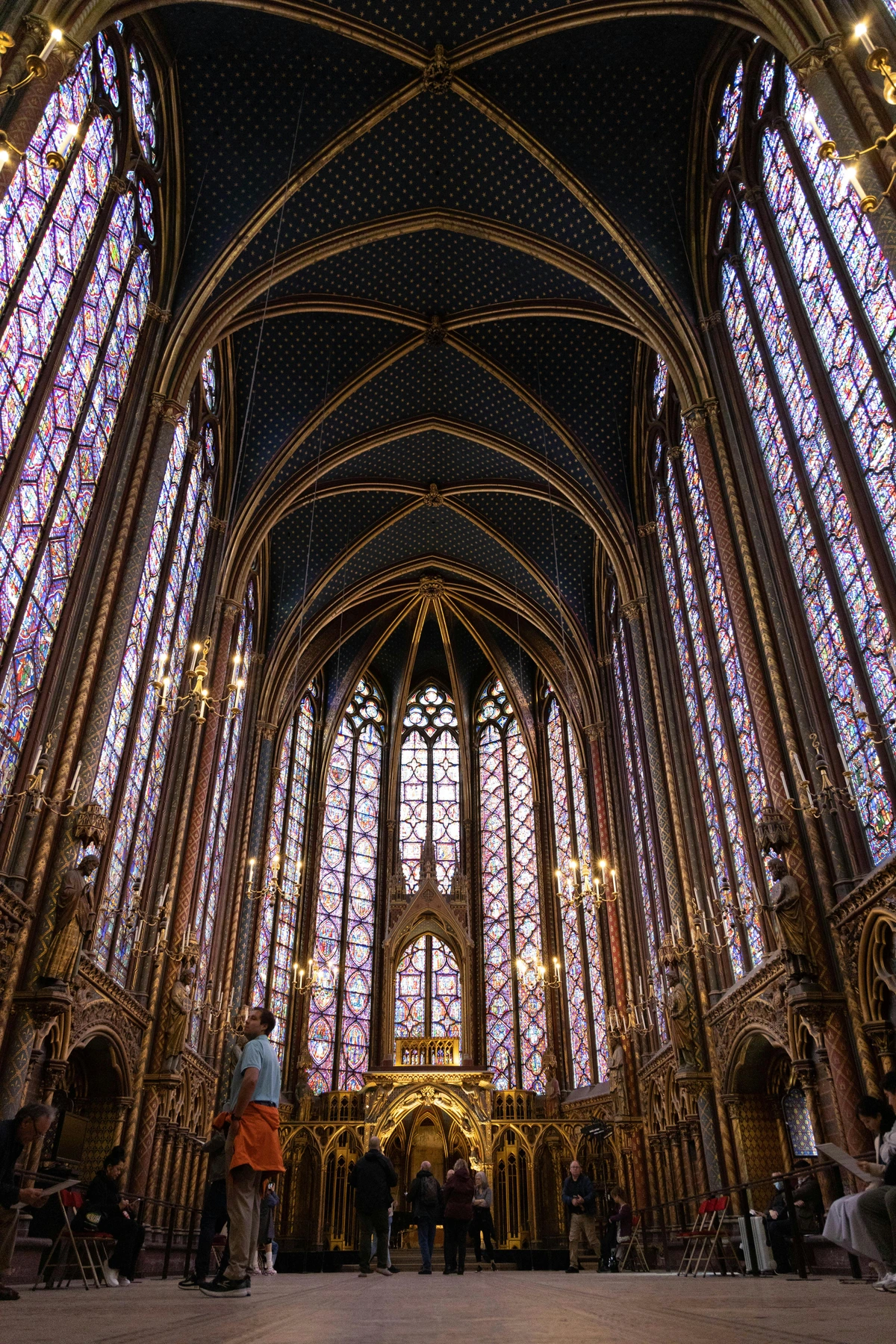

- Ancient & Medieval Times: Often linked closely with craft and skill (techne in Greek). Art served religious, ceremonial, or practical functions, with less emphasis on individual artist expression. Think Egyptian tomb paintings or the soaring stained glass and sculptures of Gothic cathedrals like Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.

- Renaissance: Saw the elevation of the artist from craftsperson to intellectual creator. Emphasis shifted towards realism, humanism, and individual genius. Works like Raphael's School of Athens exemplify this focus on intellect and idealized representation, fitting the Mimetic theory.

- 18th Century: The concept of "fine arts" (painting, sculpture, architecture, music, poetry) emerged, distinguished from crafts by their focus on aesthetics and intellectual engagement rather than utility. This period solidified the idea of art for art's sake, influenced by philosophers like Kant.

- Modernism (late 19th - mid-20th Century): Artists challenged traditional conventions, experimenting radically with form, material, and subject matter. Key movements pushed boundaries:

- Impressionism: Focused on capturing fleeting moments of light and color, often painted outdoors (en plein air). Think Claude Monet's Impression, soleil levant (which gave the movement its name) or his depictions of water lilies.

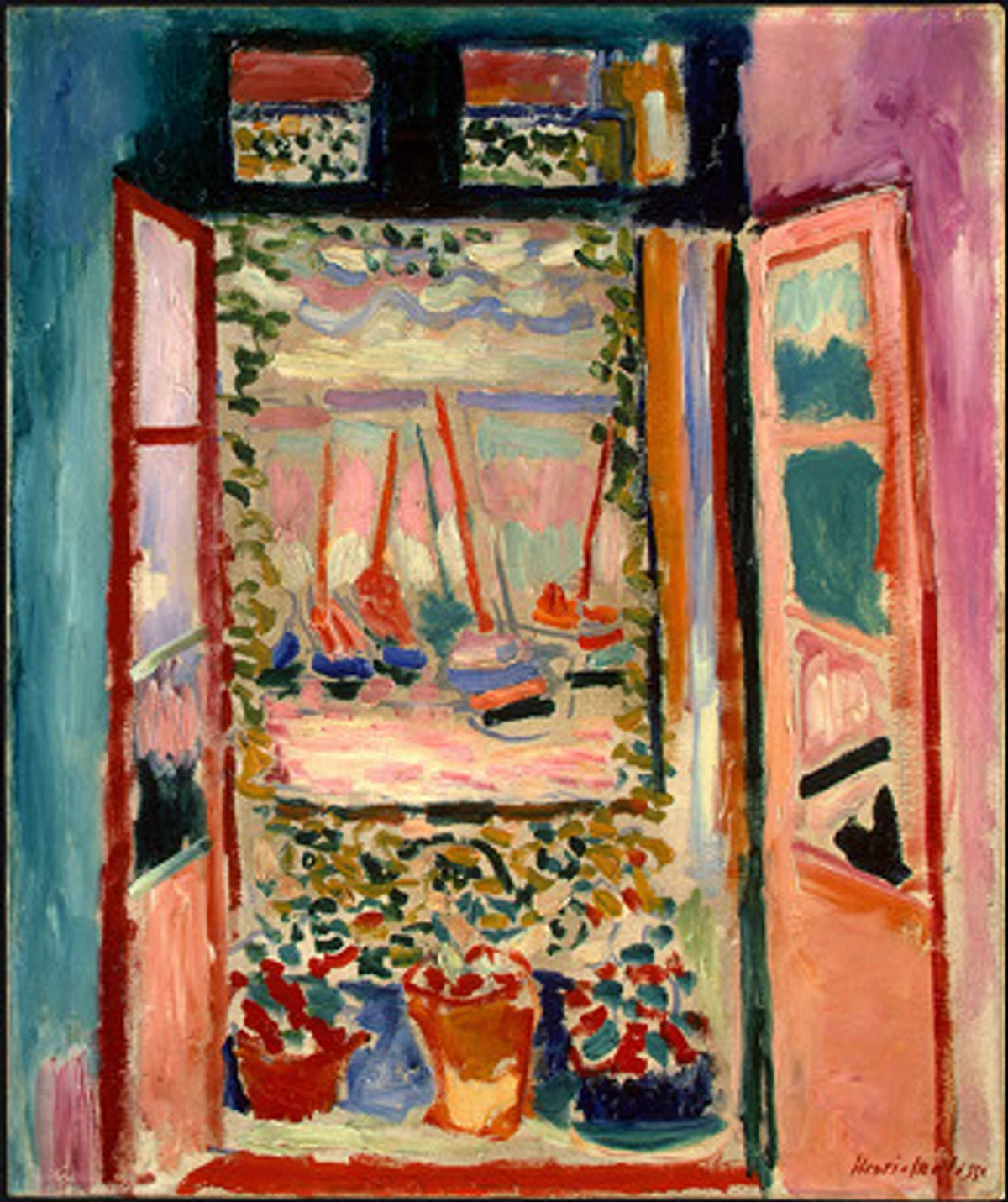

- Fauvism: Characterized by strong colors and fierce brushwork, prioritizing painterly qualities and subjective expression over realistic values (e.g., Henri Matisse's Woman with a Hat).

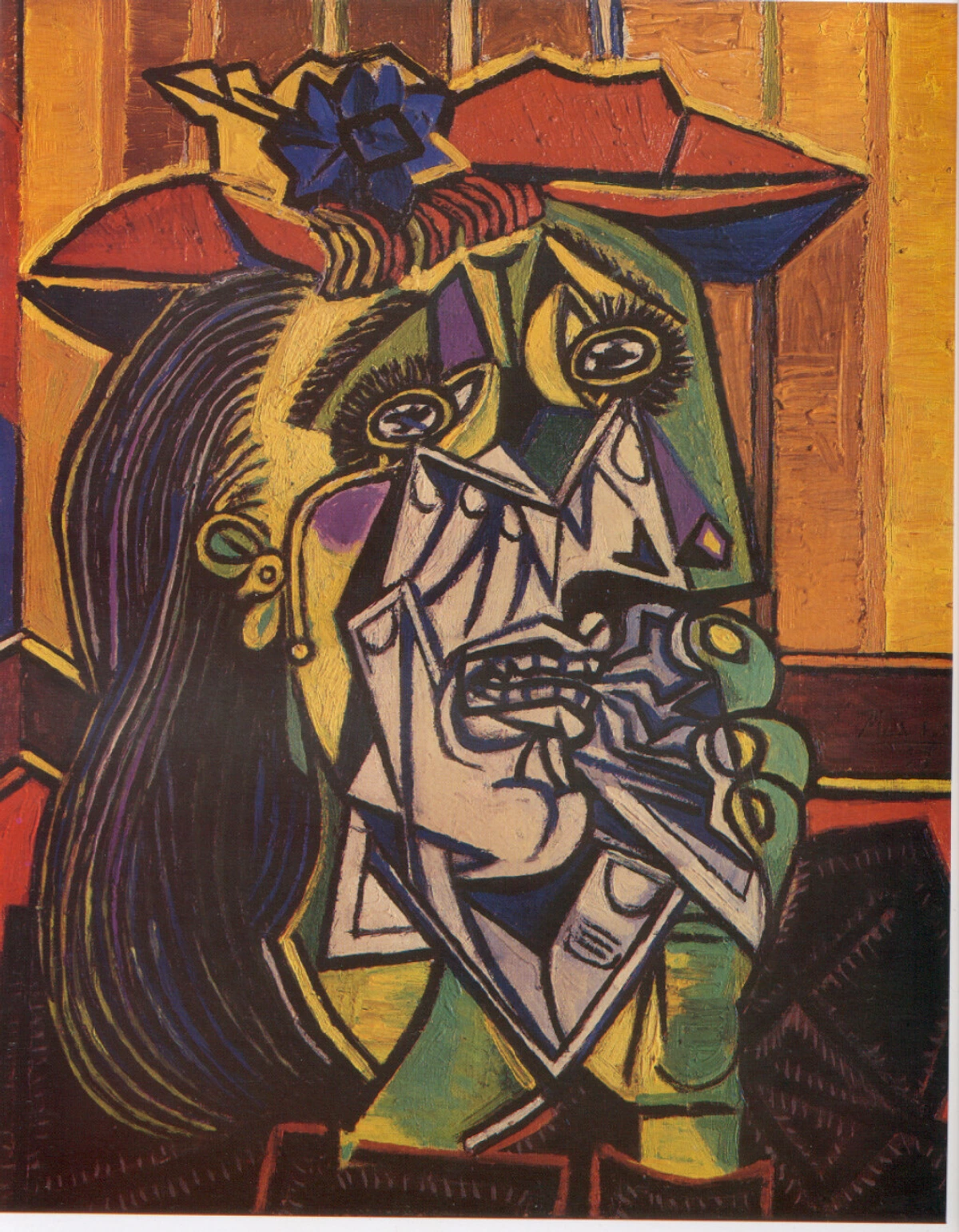

- Cubism: Revolutionized perspective by depicting subjects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, fragmenting forms into geometric shapes. Pablo Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon is a pivotal work, as is the work of Georges Braque and Juan Gris.

- Expressionism: Emphasized subjective experience and emotional expression over physical reality, often using distorted forms and intense colors (e.g., Munch's The Scream).

- Surrealism: Explored the subconscious mind, dreams, and irrationality. Salvador Dalí's The Persistence of Memory (with its melting clocks) is an iconic example.

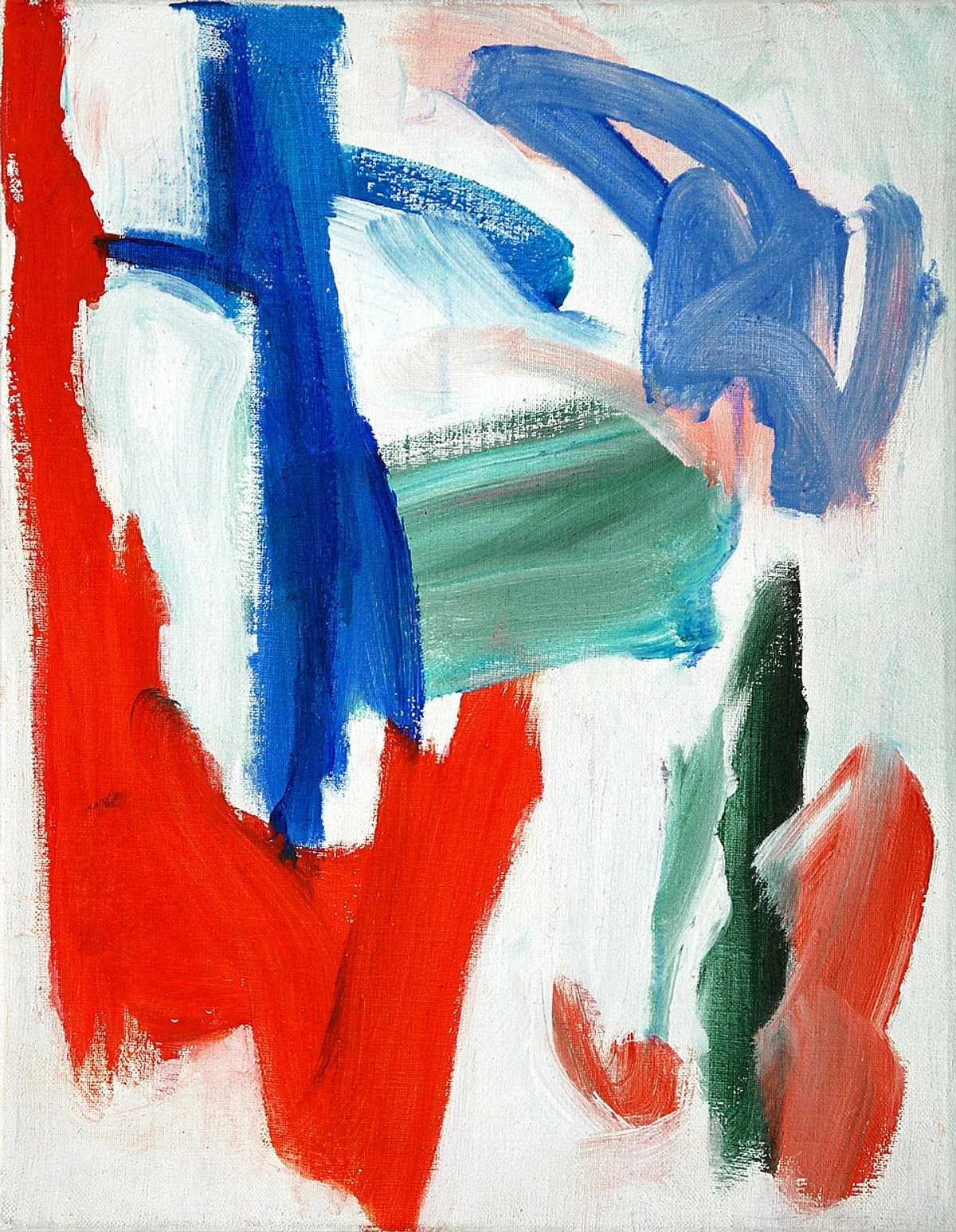

- Abstract Expressionism: Focused on gestural brush-strokes or large fields of color to convey emotion or spiritual states (e.g., Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko).

- Dadaism: Emerged during World War I, radically rejecting traditional artistic values and logic, embracing absurdity and chance (think Jean Arp, Kurt Schwitters, or the provocative ready-mades of Marcel Duchamp). Understanding this period is key to appreciating why people like modern art. Famous modern art often deliberately broke the rules.

- Postmodernism & Contemporary Art (mid-20th Century - Present): Characterized by pluralism, skepticism towards grand narratives, and the blurring of boundaries between high and low culture, art and life. Conceptual art, performance art, installation art, and digital media became prominent. The definition expanded drastically, often emphasizing the idea or concept over the physical object. Movements like Fluxus in the 1960s further blurred art and life with playful, often ephemeral events and objects. The question "But is it art?" became almost a cliché, often prompted by works designed to provoke. Key works include Joseph Kosuth's One and Three Chairs (1965), which presented a chair, a photo of the chair, and a dictionary definition of "chair," questioning representation and the nature of art itself.

![]()

Art That Tested Boundaries

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, numerous artworks have deliberately challenged the definition of art, sparking controversy and debate:

- Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917): As mentioned, submitting a standard urinal signed "R. Mutt" questioned authorship, originality, and the role of the institution.

- Carl Andre's Equivalent VIII (1966): A minimalist sculpture consisting of 120 firebricks arranged in a simple rectangle. Purchased by the Tate Gallery, it caused public outcry ("What? A pile of bricks?") forcing people to confront minimalist aesthetics and the idea of value in art.

- Andres Serrano's Piss Christ (1987): A photograph of a small plastic crucifix submerged in the artist's urine. It ignited furious debate about blasphemy, artistic freedom, and the use of bodily fluids, becoming a major flashpoint in the American "culture wars."

- Performances by Marina Abramović: Works like Rhythm 0 (1974), where she allowed the audience to use various objects on her body for six hours, pushed the boundaries of endurance, audience participation, and the artist's vulnerability, questioning the limits of performance art. You can find an ultimate guide to Marina Abramović here.

These controversies, while sometimes uncomfortable, are vital. They force us to re-examine our assumptions about what art should be, what it can do, and who decides.

Contemporary Developments

Today, art continues to evolve rapidly, influenced by technology and globalization. Key trends include:

- Digital Art & New Media: Utilizing computers, software, the internet, virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR). This includes sub-genres like Generative Art, where artists create systems (often code) that autonomously generate artworks based on algorithms or rulesets. The rise of NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) and Blockchain Art has also disrupted traditional ownership and sales models, creating new digital marketplaces and forms of verification, though not without debate about environmental impact and artistic value.

- AI Art: Art generated or assisted by artificial intelligence algorithms, raising new questions about creativity, authorship, and the very definition of an 'artist'.

- Installation Art: Creating immersive environments that viewers can enter and experience, often site-specific.

- Street Art: Art created in public spaces, often challenging traditional gallery settings. Think Banksy, Shepard Fairey, or local graffiti artists transforming urban landscapes.

- Conceptual Art: Where the idea or concept behind the work is paramount, often more so than the aesthetic or material form (Sol LeWitt's instructions for wall drawings are a classic example).

- Land Art / Earthworks: Art made directly in the landscape, sculpting the land itself or making structures in nature using natural materials. Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty (1970), a massive coil of rock built into Utah's Great Salt Lake, is a seminal example.

- Socially Engaged Art: Art projects that directly involve communities or address social issues, often focusing on collaboration and process over a final object. Examples might include projects working with homeless populations, environmental activism expressed through art (like Olafur Eliasson's Ice Watch), or community mural projects. Theaster Gates' work transforming abandoned buildings on Chicago's South Side is a prominent example of merging art, urban planning, and community development.

- BioArt: Art practices that use living tissues, bacteria, life processes, and biotechnology as mediums, often exploring ethical and philosophical questions about life itself. Artists like Eduardo Kac (known for his fluorescent bunny GFP Bunny) or the SymbioticA lab push these boundaries, sometimes controversially.

Many top living artists work across these diverse forms, refusing easy categorization.

The Role of Context and the 'Art World'

Where and how art is presented significantly impacts its perception and meaning. An object placed in one of the best museums – whether encyclopedic (like the Met or Louvre), dedicated to contemporary art (like MoMA or Tate Modern), or focused on a single artist (like the Van Gogh Museum) – or featured in prestigious galleries (like those found in major art cities) is perceived differently than the same object found on the street or in a home. The institutional context often confers the status of "art," as the Institutional Theory suggests. Major international exhibitions like the Venice Biennale or the Whitney Biennial also play a crucial role in shaping contemporary art discourse and anointing new talent.

The Influence of the Art Market

Beyond museums and non-profit spaces, the commercial art market plays a significant role in shaping perceptions and, arguably, definitions of what constitutes valuable or important art. This ecosystem includes:

- Commercial Galleries: Represent artists, exhibit their work, and facilitate sales (often taking a significant commission, typically 50%). They act as gatekeepers and taste-makers. You can explore best galleries for emerging artists or established ones in cities like New York or London.

- Auction Houses: Major players like Sotheby's and Christie's handle the resale of high-value artworks, setting public price benchmarks. Their sales results often make headlines and influence collector behavior. Navigating the secondary art market can be complex.

- Art Fairs: Events like Art Basel, Frieze, and TEFAF bring together galleries, collectors, curators, and critics, acting as major marketplaces and networking hubs. Visiting art fairs can be overwhelming but exciting.

- Collectors: Individuals, corporations, and institutions who buy art, sometimes for passion, sometimes as an investment, and sometimes for status (why do rich people buy art?). Their choices directly impact artists' careers and market trends. Understanding art prices is key here.

- Critics and Curators: While often operating within institutions or publications, their writings and exhibition choices influence how art is understood and valued, impacting both historical narratives and market perception. Feminist art historians like Linda Nochlin (with her seminal 1971 essay "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?") fundamentally challenged the established canon and critiqued the institutional biases that shaped previous definitions of "great art."

- Other Key Roles: Don't forget the crucial work of Art Conservators, who preserve and restore artworks, ensuring their survival for future generations (art care is vital!), and Art Advisors, who guide collectors through the complexities of the market.

This market system undeniably confers value (financial and cultural) and shapes careers, but it also raises questions about whether market success equates to artistic merit. Does a high price tag automatically make something "good" art? It's another layer in the complex question of defining art's meaning and value.

Similarly, historical, cultural, and social context is crucial for understanding an artwork's intended meaning and significance.

Ownership and Belonging: Repatriation Debates

The context of where art resides also brings up complex issues of ownership and belonging, particularly regarding artifacts removed from their cultures of origin, often during colonial periods. The ongoing debates surrounding the Repatriation of objects like the Elgin Marbles (taken from the Parthenon in Athens, now in the British Museum) or the Benin Bronzes (looted from the Kingdom of Benin, now dispersed in Western museums) highlight these ethical dilemmas. Should these objects be returned to their places of origin? Museums often argue they can provide better preservation and wider access, while source countries assert rights based on cultural heritage and historical justice. These aren't easy questions, and they force us to consider how historical power imbalances continue to shape our access to and understanding of global art history.

How to Appreciate Art

Appreciating art is a personal journey that involves more than just liking what you see. It's about engagement, curiosity, and being open to different experiences. Here are some ways to deepen your engagement:

- Look Closely: Spend time observing the details – the use of color, line, texture, composition. What elements of art stand out?

- Consider the Context: Learn about the artist, the historical period, and the cultural background. Why was it made? What was happening at the time? Reading an artist's story, perhaps like the journey detailed on a timeline, can add depth. Understanding the history of art provides invaluable perspective.

- Think About Intent vs. Interpretation: What might the artist have intended? How do you interpret it based on your own experiences and knowledge? Sometimes understanding symbolism (How to Understand Symbolism) can unlock layers of meaning.

- Engage Your Senses and Emotions: How does the artwork make you feel? What thoughts does it provoke? Does it remind you of anything? Don't be afraid to have an emotional reaction!

- Explore Different Genres and Styles: Don't limit yourself. Visit diverse exhibitions, from historical collections to contemporary installations, perhaps even at dedicated spaces like the Zen Museum in 's-Hertogenbosch. Define your own taste (How to Define Your Personal Art Style and Taste) by exploring widely. Look at all art styles!

- Read About Art: Familiarize yourself with basic art history and terminology (Art Jargon Explained). Guides on analysis, like how to read a painting, can be very helpful.

- Trust Your Response: While context is important, your personal connection matters. What resonates with you? Deciding what art you should buy often comes down to this connection, perhaps discovering colorful abstract pieces (available here) that speak directly to you. Sometimes, it's just a gut feeling, and that's perfectly okay.

Further Reading and Resources

If this exploration has piqued your interest (and I hope it has!), diving deeper is always rewarding. Here are a few starting points:

- Foundational Art History Texts: Classics like Gardner's Art Through the Ages or Janson's History of Art offer comprehensive overviews, though always read older texts with an awareness of potential biases. E.H. Gombrich's The Story of Art is also a highly accessible introduction.

- Key Art Publications: Magazines like Artforum, Frieze, and ArtReview offer insights into the contemporary art scene, reviews, and critical essays. Online platforms like Artsy, Artnet News, and Hyperallergic are also great resources.

- Museum Websites: Most major museums have extensive online collections and educational resources – explore their websites!

Ultimately, art represents a creative endeavor that seeks to establish a connection with our senses and our intellect. This connection can be forged through various means, whether it is the appreciation of beauty, the evocation of emotional responses, or the stimulation of intellectual thought. The concept of art is not static but rather dynamic and constantly evolving, adapting to new forms, technologies, and cultural contexts, ensuring its continued relevance and its ongoing enrichment of the human experience. The art definition remains wonderfully, frustratingly, beautifully open.