Marina Abramović: Ultimate Guide to Her Performance Art, Life & Method

Dive deep into Marina Abramović's intense performance art, from the shocking Rhythm series and Ulay collaborations to 'The Artist is Present' and the Abramović Method. Explore her influences, controversies, and lasting legacy through a personal, introspective lens.

Marina Abramović: The Ultimate Guide to the Grandmother of Performance Art

Alright, let's talk about Marina Abramović. Even if you only vaguely follow the art world, chances are you've heard her name, maybe seen a picture of her staring intently at someone, or perhaps heard whispers of performances involving knives, fire, or just... sitting. It’s the kind of Marina Abramović art that lodges itself in your brain, whether you find it profound or profoundly baffling. It certainly lodged itself in mine, sparking questions about what art could be and pushing the boundaries of my own creative thinking, much like her work pushes the boundaries of the body itself.

Honestly, encountering Abramović's work for the first time can be a bit like suddenly realizing your quiet neighbour spends their weekends wrestling bears. It's unexpected, intense, and makes you question what you thought you knew. I remember first learning about her Rhythm series, particularly the sheer vulnerability of Rhythm 0, and feeling a mix of fascination and genuine discomfort – which, I suspect, is often the point. But understanding this artist Marina Abramović requires diving deeper than just the shock value. It requires sitting with the discomfort, letting it wash over you, and asking why. It's a process that, as an artist myself, resonates deeply with the often uncomfortable introspection required to create anything meaningful.

So, grab a metaphorical cup of tea (or something stronger), and let's try to unpack the world of one of the most influential and provocative contemporary artists alive today. This is your ultimate guide, seen through my slightly bewildered, deeply fascinated eyes.

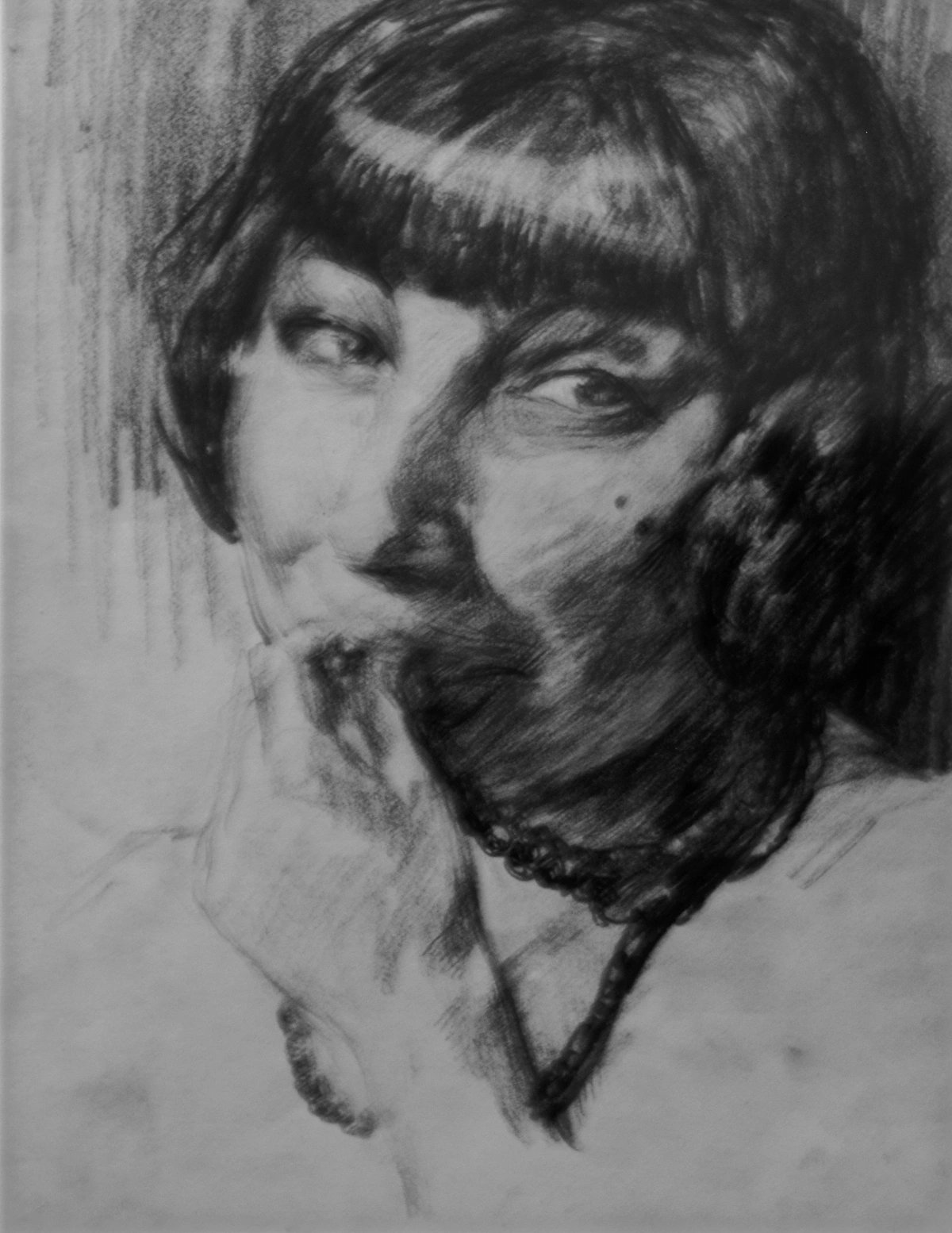

Who is Marina Abramović? The "Grandmother of Performance Art"

Born in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia) in 1946, Marina Abramović didn't exactly have a typical, quiet upbringing. Her parents were national heroes in post-WWII Yugoslavia, a background steeped in discipline, communism, and a certain intensity that arguably permeates her work. She studied painting initially, but found the canvas too limiting. It felt static, a flat, inert barrier between the artist's dynamic inner world and the viewer's experience. She needed something more immediate, more visceral, something that used the raw material of existence itself – the body, time, energy. She needed performance art.

She’s often called the "grandmother of performance art," not just because she's been doing it for decades (since the early 1970s!), but because she fundamentally shaped the medium, pushing its boundaries and demanding it be taken seriously alongside painting or sculpture. She didn’t just do performance art; she lived it, using her own body as both subject and medium. It was a radical act, especially at a time when the art world was still grappling with what art could be.

What is Performance Art (And Why Should You Care?)

Okay, quick detour. What is performance art, anyway? It's a tricky one to pin down, falling somewhere between theatre, visual art, and... life itself? Unlike traditional theatre with scripts and characters, performance art often involves the artist performing an action or series of actions, often testing physical or mental limits, right there in front of an audience (or documented for later viewing). It emerged prominently in the mid-20th century, partly as a reaction against the increasing commodification of art objects, offering an experience that couldn't simply be bought and sold.

It can feel alienating at first. "Why is this art?" is a question I’ve definitely asked myself, staring at documentation of someone doing something seemingly mundane or incredibly painful. But often, the power lies in the presence, the endurance, the vulnerability, and the energy exchanged between the artist and the viewer. It challenges our ideas about art, participation, and the limits of human experience. It’s less about a finished object and more about the experience. Think of it like feeling the 'vibe' of a room or a person, but amplified and intentionally focused. Or maybe like that moment you hold eye contact with a stranger for just a second too long – that tiny, charged interaction? Performance art takes that feeling and stretches it, twists it, and makes you really feel it. You can explore more about different art styles and movements here.

Early Explorations: The Shocking Rhythm Series

This is where Abramović burst onto the scene, and frankly, where things get intense. The Marina Abramović Rhythm series (1973-1974) was a raw exploration of bodily limits, consciousness, and danger. Learning about these felt like a punch to the gut – a necessary one, perhaps, but jarring nonetheless. These works were perceived as groundbreaking and genuinely shocking at the time, firmly establishing her as a fearless and provocative voice in the nascent performance art scene.

- Rhythm 10 (1973): Remember that game where you stab a knife quickly between your spread fingers? Abramović did that, recorded it, and then replayed the recording, trying to replicate the cuts and rhythms exactly, blurring the line between past and present pain. (Don't try this at home, seriously.) The sheer, deliberate repetition of self-inflicted risk is what stuck with me.

- Rhythm 5 (1974): She lay inside a large, burning wooden star. As the fire consumed oxygen, she lost consciousness and had to be rescued by audience members who realised the performance had tipped into real danger. This piece, for me, highlights the terrifying line she walked between performance and genuine peril.

- Rhythm 0 (1974): Perhaps the most infamous. Abramović stood passively for six hours, placing 72 objects on a table – including a rose, honey, scissors, a scalpel, and a loaded gun – with the explicit instruction that the audience could use them on her in any way they chose. It started gently, but escalated to violence, her clothes being cut off, and someone pointing the loaded gun at her head before others intervened. It was a terrifying study of human nature when constraints are removed, and the vulnerability she exposed herself to is almost unfathomable.

These early works established her fearlessness and her willingness to put her body on the line to explore complex psychological and social themes. They weren't just performances; they were confrontations. And after pushing her own limits to such extremes, what happens when you bring another person into that volatile space?

The Ulay Years: Collaboration, Conflict, and the Great Wall

From 1976 to 1988, Marina Abramović collaborated intensely with the German artist Ulay (Frank Uwe Laysiepen). Their personal and artistic lives became inseparable. Their work together explored themes of duality, identity, ego, and endurance, often pushing the boundaries of partnership itself. Anyone searching for "Ulay Marina Abramović" finds a story as epic and dramatic as any opera. Merging your life and work so completely with another person? I can barely decide what to have for dinner with someone, let alone create art that relies on that level of intertwined existence. It must have been exhilarating and utterly exhausting, a constant negotiation of self and other, amplified by the public nature of their creative output.

Key collaborative works include:

- Relation Works (1976-1977): A series including pieces where they sat back-to-back with their hair tied together for hours, or repeatedly slapped each other. These simple actions, drawn out, became profound statements on connection and conflict. It makes you think about the small, repetitive frictions and bonds in any long-term relationship, just... amplified to an extreme.

- Imponderabilia (1977): Visitors had to squeeze sideways between the naked bodies of Abramović and Ulay standing in a narrow museum doorway, forcing a choice and an intimate encounter. Imagine doing that on your way to see some nice landscapes! It forces you to confront your own boundaries and reactions, and maybe feel a little awkward, which is probably the point.

- Rest Energy (1980): A heart-stopping piece where Ulay held a drawn bow with the arrow aimed directly at Abramović's heart, her body weight keeping the string taut. Microphones amplified their accelerating heartbeats. The tension is palpable even in photos – a perfect metaphor for the fragile trust in any deep relationship. Just looking at images of this piece makes my palms sweat.

- Nightsea Crossing (1981-1987): A series of silent performances where they sat motionless across a table from each other for days on end in various museums worldwide. Pure, unadulterated endurance and presence. I can barely sit still through a movie, let alone days of silent staring. The mental discipline required is astounding.

Their relationship ended as dramatically as it was lived. Instead of just breaking up, they undertook The Lovers: The Great Wall Walk (1988). They started at opposite ends of the Great Wall of China and walked towards each other for three months, meeting in the middle to say goodbye. You can't make this stuff up. It was a monumental end to a legendary partnership, a physical manifestation of their separation. The complexities of their shared legacy, including later legal disputes over ownership of collaborative works, only add another layer to the story of how intertwined their lives and art became.

Solo Endurance: Pushing Limits Alone

After Ulay, Abramović continued her solo explorations, often focusing on long-durational performances and engaging with her personal history and cultural trauma. The shift from relying on a partner's presence and energy to drawing solely on her own must have been immense, a turning inward after years of intense outward connection. While the Ulay works explored relational endurance and trust between two people, her solo pieces often focused on confronting the self, personal history, and collective trauma through sheer individual physical and mental fortitude.

- Balkan Baroque (1997): At the Venice Biennale, she sat for days amidst a pile of 1,500 bloody cow bones, scrubbing them clean while singing folk songs from her childhood. It was a powerful, gut-wrenching commentary on the Bosnian War and the brutality she felt connected to her homeland. It won her the Golden Lion award. It's the kind of piece that sticks with you, the smell, the sound, the sheer, repetitive grief made visible.

- The House with the Ocean View (2002): For 12 days, she lived in three open-sided cubes installed in a New York gallery, visible to the public 24/7. She didn't eat or speak, only drank water, slept, sat, and showered. Visitors watched her every move, creating an intense energetic exchange. It makes you wonder about the sheer mental fortitude required to maintain that level of exposed presence, and also about the audience's role – what does it mean to simply watch someone exist like that?

These works solidified her reputation for extreme endurance and her willingness to confront difficult histories through her body. And perhaps the most famous example of this solo, long-durational focus came next.

The Artist is Present: Staring into the Soul of MoMA

Perhaps her most famous work, at least in recent memory, was The Artist is Present at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 2010. For three months, during the museum's opening hours (over 700 hours total), Abramović sat silently in a chair. Across from her was another chair, where visitors could sit, one at a time, for as long as they liked, meeting her gaze. An estimated 1,500 people sat opposite her during the exhibition's run, with countless others observing.

It sounds simple, almost boring, right? Just sitting. But it became a cultural phenomenon. People queued for hours, sometimes overnight. Many who sat opposite her were moved to tears, experiencing a profound sense of connection or self-reflection in her unwavering gaze. The silence, the duration, the focused attention – it created an incredibly charged space. In our hyper-connected, yet often disconnected, world, the simple act of truly seeing and being seen by another human, without distraction, is incredibly powerful. It makes me think about how rarely we allow ourselves that kind of focused presence, even with people we know well. It's a performance that, despite its stillness, felt incredibly active on an emotional and energetic level.

And yes, there was that moment: Ulay showed up unannounced, sat opposite her, and they shared a deeply emotional, tearful reunion across the table after decades apart. It went viral, naturally. It highlighted the power of shared history and human connection at the heart of much Marina Abramović performance, proving that even the most controlled performance can be pierced by raw, unplanned human emotion. This iconic performance and the story behind it were captured in the acclaimed 2012 documentary Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present.

The Abramović Method: Training Body and Mind

Over the years, Abramović developed the Abramović Method, a series of exercises designed to heighten participants' awareness, concentration, and endurance. These exercises formalized the rigorous physical and mental training she had developed for herself over decades of demanding performances, drawing inspiration from various disciplines including Jerzy Grotowski's experimental theatre techniques. Think exercises like slowly walking, separating and counting grains of rice and lentils for hours, or standing blindfolded in nature. It’s about preparing the body and mind for long-durational performance, but also about finding focus and presence in our hyper-distracted modern lives. What would it feel like, I wonder, to spend hours simply separating rice and lentils? Tedious, yes, but perhaps also incredibly centering, forcing the mind into a state of focused calm that's hard to achieve otherwise. I mean, my phone buzzes and I lose track of what I was doing, let alone counting tiny grains for hours. She now teaches this through workshops and the Marina Abramović Institute (MAI), which serves as a hub for performance art and her method.

Influences, Philosophy, and the Spiritual Dimension

Beyond the physical and psychological, Abramović's work is deeply informed by various philosophical and spiritual traditions. She's spoken about the influence of Tibetan Buddhism, particularly its focus on meditation, mindfulness, and the concept of impermanence. These resonated with her because her performances often involve extended periods of stillness, intense focus, and a confrontation with the transient nature of the body and the performance itself. Shamanism has also played a role, informing her understanding of ritual, healing, and altered states of consciousness – concepts directly explored in works involving pain, endurance, and transformation. Even the rigorous physical and mental training methods of Jerzy Grotowski's experimental theatre have left their mark on her approach to preparing the body and mind for performance, emphasizing discipline and presence.

These influences aren't just academic; they're woven into the fabric of her practice. The long durations aren't just about testing limits; they're a form of meditation, a way to transcend the physical and reach a heightened state of awareness. The rituals in her work often echo ancient practices, seeking transformation or catharsis. It's this blend of the intensely physical with the deeply spiritual that gives her work such a unique resonance. It makes me reflect on my own attempts at finding focus amidst the chaos of daily life and artistic creation – maybe I need to try counting some rice?

Beyond the Gallery: Opera, Film, and Public Projects

Abramović's work hasn't been confined to traditional performance spaces. She's explored other mediums and platforms, extending her reach and influence.

- Opera and Theatre: She has collaborated on and starred in theatrical productions, most notably The Life and Death of Marina Abramović (2011), a biographical opera directed by Robert Wilson. Seeing her life translated into the grand, dramatic scale of opera must be quite an experience – a different kind of performance, but still centered on her own narrative. I haven't seen it myself, but I imagine it adds a layer of theatricality that both complements and contrasts with the raw immediacy of her gallery work.

- Film and Documentaries: Her life and work have been the subject of numerous films, including the acclaimed documentary Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present (2012), which brought her to a wider global audience. Documentaries like this are often how many people, myself included, first encounter her work, offering a window into performances that are otherwise ephemeral.

- Public Projects: Beyond the MAI, she has engaged in other public-facing works. For example, her 2014 piece Cleaning the House involved participants undergoing the Abramović Method exercises in public spaces, bringing the principles of her practice directly to a wider audience outside the traditional gallery setting. Through the MAI, she continues to develop projects that engage the public and support other performance artists, solidifying her role as a mentor and institution-builder.

These ventures show an artist constantly evolving, finding new ways to communicate her core themes to different audiences.

Controversies and the Public Persona

Like many artists who push boundaries and gain significant fame, Abramović hasn't been without controversy beyond the initial shock of her early work. Criticisms have sometimes been leveled at the commercialization of her brand and method, questioning whether the intense, often anti-establishment spirit of performance art can truly coexist with mainstream success and high price tags. Some public statements she's made over the years have also sparked debate and backlash, including controversial comments about indigenous people and specific commercial ventures like her collaboration with Adidas or the high-profile MAI gala events. It's a complex aspect of her career – navigating the demands of being a global art icon while staying true to the radical roots of her practice. It reminds me that the art world, like any other, has its own set of complicated dynamics and public scrutiny.

Themes and Legacy: Why Does Her Art Matter?

So, after all the pain, endurance, sitting, and rice-counting, what's the takeaway? Why does Marina Abramović's art matter? What threads connect these disparate, often extreme, acts? Key themes in Marina Abramović art include:

- The Limits of the Body: Pushing physical and mental endurance to the breaking point.

- Risk and Trust: Placing herself in vulnerable or dangerous situations, often relying on the audience or a partner – a terrifying mirror to the risks we take in life and relationships.

- Presence and Consciousness: Exploring altered states of mind, the power of the present moment, and heightened awareness. How often are we truly present? It's a question her work constantly forces us to ask ourselves.

- Energy Exchange: The invisible, yet palpable, connection between performer and audience. It's like that feeling when you walk into a room and can immediately sense the atmosphere, but here it's intentional and central to the work.

- Ritual and Spirituality: Drawing on ancient traditions and creating modern rituals to explore transformation and transcendence.

- Pain and Trauma: Confronting personal and collective suffering, particularly related to her Balkan heritage.

- Time: Using long duration as a key element, forcing both artist and audience to experience time in a different, often challenging, way. Time becomes a material in itself.

Her legacy is immense. She brought performance art from the fringes into major institutions like MoMA, the Guggenheim, and the Tate Modern. Her work significantly influenced the institutional acceptance of performance art, paving the way for it to be collected, exhibited, and studied by major museums worldwide. She influenced generations of artists exploring body art, endurance, and audience participation. She proved that art could be an immaterial experience, a confrontation, a shared moment in time. You can see echoes of this exploration of experience in many forms of modern art and understand its impact through the lens of art history. Her willingness to be vulnerable and push boundaries paved the way for countless others.

Experiencing Abramović Today

While many of her most famous performances were ephemeral, they live on through photographs, videos, and written documentation. Major museums worldwide, including MoMA, the Guggenheim, and the Tate Modern, hold significant documentation of her work and often feature retrospectives (check out some top museums here). The Marina Abramović Institute (MAI) also works to preserve long-durational and performance art. Sometimes, her works are "re-performed" by other artists, raising interesting questions about authenticity and the nature of performance. Seeing a re-performance can be powerful, but it's never quite the same as the original, is it? It makes you appreciate the unique energy of that initial, unrepeatable moment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is Marina Abramović's art real? Did she really put herself in danger? A: Yes. The risks in works like the Rhythm series were absolutely real, often pushing the boundaries of safety. That's part of what makes them so challenging and discussed.

Q: Why is her work so controversial? A: It confronts viewers with difficult themes: pain, endurance, vulnerability, violence, the body. It challenges traditional notions of what art should be (beautiful, object-based) and can be physically and emotionally demanding for both the artist and the audience. Some controversies have also arisen from her public statements or later projects, adding layers to her public image.

Q: What happened between Marina Abramović and Ulay? A: After 12 years of intense artistic and personal collaboration, they ended their relationship with the symbolic Great Wall Walk performance in 1988. They had a famous, emotional reunion during her The Artist is Present performance in 2010, though later legal disputes over shared works arose.

Q: Where can I see Marina Abramović's work? A: Major museums often feature documentation (photos, videos) of her performances in exhibitions of contemporary art. Keep an eye out for major retrospectives. The Marina Abramović Institute (MAI) is another resource. You might occasionally find newer works or re-performances scheduled at galleries or performance art festivals.

Q: Is performance art like acting? A: Not exactly. While both involve performing for an audience, performance art typically doesn't involve playing a character or following a script in the traditional sense. The artist is often presenting themselves, their body, and their actions as the artwork itself. It's less about portraying someone else and more about being in that moment, often in a state of heightened presence or endurance.

Q: Can anyone practice the Abramović Method? A: While the full method is taught through workshops and the MAI, many of the core principles focus on simple exercises for concentration, presence, and endurance that can be adapted for personal practice. The MAI offers resources and programs accessible to the public.

Conclusion: The Enduring Presence

Marina Abramović isn't an artist you can be neutral about. Her work demands a reaction. It pushes buttons, challenges comfort zones, and forces us to confront fundamental questions about life, art, and human connection. Whether you find her work deeply moving, disturbingly provocative, or utterly bewildering, her impact on the history of art is undeniable.

She has spent a lifetime using her body to explore the very edges of human experience, inviting us, sometimes uncomfortably, to watch and participate. It's a bit like looking at some intense abstract art – it might not offer easy answers, but it certainly makes you feel something. And in a world saturated with fleeting images, that enduring presence, that willingness to truly be there, might be her most radical act of all. Her journey, pushing through physical and mental barriers, makes me think about my own creative timeline and the challenges I face in my studio. Perhaps exploring her work inspires you to seek out art that challenges you, whether in a museum near Den Bosch or available online.