Ultimate Guide to Art Styles & Movements: From Byzantine to AI Art

Explore art styles & movements through a personal lens. From Byzantine mosaics to AI art, understand definitions, characteristics, and find what resonates with you. Includes contemporary & global styles, plus FAQs on classification, developing style, and more.

Types of Art Styles: A Comprehensive Guide for Art Lovers

The world of art is incredibly diverse, filled with countless ways artists express themselves. Understanding different art styles is like learning a visual language – it deepens your appreciation, helps you analyze paintings, and guides you in discovering what truly resonates with you. This guide will primarily explore the rich tapestry of Western art history, offering a glimpse into influential styles from the medieval period through to the dynamic landscape of contemporary art, while also acknowledging the vast and vital traditions that exist beyond the West. My hope is that by navigating these styles, you'll not only gain knowledge but also find a deeper personal connection to the art that moves you and feel more confident navigating the art world, whether you're looking to buy art for your home or simply deepen your appreciation.

I remember feeling completely lost walking into museums as a teenager, just staring blankly at canvases, wondering why some were so famous and others I'd never heard of. It felt like everyone else had the secret handshake. Learning about styles was my 'aha!' moment – seeing how the bold, non-naturalistic colors of Fauvism or the fragmented perspectives of Cubism weren't just random but part of a deliberate visual language. I mean, who decided painting a face from three angles at once was a good idea? It initially baffled me, but the sheer audacity of it was also thrilling. It didn't just change how I looked at art; it fundamentally changed how I felt about it, and eventually, how I started making my own abstract work, exploring that same freedom from strict representation. Whether you're a seasoned collector or just beginning your art journey, knowing the characteristics of various styles unlocks a richer understanding of art history and contemporary practice.

But first, what exactly is an art style? It's a distinctive manner of creating art associated with a specific artist, group (art movement), period, or culture, characterized by particular techniques, subject matter, and philosophical underpinnings. It's different from an art medium (like painting or sculpture) or an art genre (like landscape or portraiture). Think of it like this: painting is the medium, landscape is the genre, and Impressionism is the style. This guide explores key art styles, providing context and clarity. Need help with terms? Check our Art Jargon Explained: Simple Glossary.

Artist Styles vs. Movement Styles: The Personal Touch

While we often talk about broad art movements like Impressionism or Cubism, it's crucial to recognize the individual artist's style. Think of a movement as a general philosophy or set of techniques shared by a group, but each artist brings their unique personality, experiences, and hand to the canvas. It's like a shared language, but each person has their own accent and vocabulary. To use a simple analogy, it's like two chefs both cooking Italian food – they share the 'movement' of Italian cuisine, but one's marinara sauce just has that thing the other's doesn't. That's the individual style. Understanding an artist's individual style can be key to identifying their work or recognizing how their vision evolved over time, adding another layer to appreciation or research.

For instance, both Monet and Renoir were Impressionists, focused on light and fleeting moments. Yet, Monet's style often emphasizes landscapes and the atmospheric effects of light with distinct, separate brushstrokes, while Renoir frequently focused on figures, parties, and a softer, more blended application of paint. Same movement umbrella, wildly different artist styles.

![]()

Similarly, within Post-Impressionism, compare the swirling emotional intensity of Van Gogh's brushwork and color to the structured, geometric approach of Cézanne or the flat, symbolic planes of Gauguin. Wildly different personal visions emerging from a shared starting point.

![]()

Developing a unique artist style is often a long journey, a process of absorbing influences, experimenting, and finding your own visual voice. It’s like learning musical scales (the movements) before composing your own symphony (the personal style). My own abstract work, for example, clearly sits within the broader abstract movement, drawing on traditions like Abstract Expressionism and Color Field, but it has its own unique stylistic signature developed over years of practice. You can see how influences shape an artist over time by exploring an artist's personal timeline. When researching artists, understanding both their connection to broader movements and their individual stylistic signature is key. It's also worth noting that sometimes, a truly unique artist's style can be so groundbreaking that it influences or even leads to the formation of a new movement, like how Cézanne's late work, with its focus on breaking down forms into geometric components, profoundly influenced the development of Cubism.

Broad Categories: A Starting Point

Okay, let's start simple. Before diving into specific movements, it's helpful to understand three overarching categories. Even these broad strokes can feel a bit overwhelming at first glance, but they give us a basic framework. Think of them as the major continents on our art style map.

- Representational Art: Aims to depict subjects realistically, as they appear in the visible world. This includes styles like Realism and Figurative Art. The goal is recognition. You see a dog, it looks like a dog. Simple enough, right? Think of a classical portrait like the Mona Lisa. This category is where most people start their art appreciation journey, finding comfort in the familiar. It's the foundation, showing art's power to mirror the world around us. My own journey started here, trying (and often failing!) to draw things exactly as I saw them. It's a crucial skill, even if you later move away from it.

- Abstract Art: Departs from realistic representation. It uses shapes, colors, forms, and gestural marks to achieve its effect, focusing on internal realities, emotions, or purely aesthetic concerns rather than visual accuracy. This website's artist specializes in vibrant, contemporary abstract pieces, exploring the compelling nature of abstraction. Think of a Jackson Pollock drip painting. It asks you to engage with the visual elements themselves, rather than looking for something you recognize. For me, this is where the real freedom lies, translating feelings and ideas directly into visual energy without being tied to depicting the 'real' world. It's a different kind of truth. Within Abstract Art, you can also distinguish Non-Objective Art, which has no recognizable subject matter from the external world at all, focusing purely on form, color, and line.

- Conceptual Art: Prioritizes the idea or concept behind the work above traditional aesthetic and material concerns. The execution is often secondary to the underlying thought process. Sometimes this feels a bit like being told the punchline before the joke, but the intellectual journey can be incredibly rewarding. Think of a Marcel Duchamp readymade like Fountain. It challenges our assumptions about what art is and can be. It's art that makes you think, sometimes more than it makes you feel or admire skill. It pushes the boundaries and asks big questions, which is vital for art to stay alive. I remember scratching my head the first time I encountered Conceptual Art – 'That's it?' I thought. But the more I learned about the why behind it, the more fascinating it became. It's a different kind of engagement, less about the visual feast and more about the mental puzzle.

These categories aren't always rigid boxes, and many artworks might blend elements – contemporary art especially loves to mix things up – but they offer a useful way to begin organizing the vast world of visual expression we're about to explore.

A Quick Look at Different Approaches: Realism vs. Impressionism vs. Cubism vs. Abstract Expressionism

Before we dive into the historical timeline, let's pause for a moment and think about how different styles can approach the same subject matter in fundamentally different ways. This isn't exhaustive, but it helps highlight the core shifts in artistic thinking:

- Realism: The goal is to show the world as it is, objectively and truthfully. If a Realist painted a bowl of fruit, you'd see every apple and orange with accurate color, shape, and texture, perhaps even a bruise or two. The focus is on observable reality, often including everyday or unglamorous subjects. It's about fidelity to visual appearance.

- Impressionism: The goal shifts from objective reality to subjective perception. An Impressionist painting of that same bowl of fruit would focus on the fleeting effects of light and color at a specific moment. The forms might be less defined, the brushstrokes visible, capturing the feeling or impression of the fruit bathed in light, rather than its precise botanical detail. It's about capturing the visual sensation.

- Cubism: Here, the goal is to explore the underlying structure of the subject and depict it from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. A Cubist bowl of fruit would be broken down into geometric facets, showing parts of the apples and oranges from the front, side, and top all at once. Color might be muted (especially in early Cubism) to emphasize form. It's about analyzing and reconstructing visual reality.

- Abstract Expressionism: This style moves away from depicting recognizable objects entirely. If an Abstract Expressionist were inspired by a bowl of fruit, they wouldn't paint the fruit itself. Instead, they might use the feeling or energy the fruit evokes – perhaps the vibrant colors, the sense of abundance, or even the process of decay – and translate that directly into non-representational forms, colors, and gestures on the canvas. It's about expressing an internal response or pure visual energy, not depicting an external subject.

See how different that is? It's not just about what is painted, but how the artist chooses to see and represent it. This fundamental difference in approach is what defines many of the styles we'll explore.

A Journey Through Key Western Art Styles

Art history is a tapestry of evolving styles, often reacting to or building upon what came before. The broad categories we just discussed – Representational, Abstract, and Conceptual – manifest differently across these historical periods. For example, while Byzantine art is representational, its approach to representation is vastly different from Renaissance Realism. Abstract elements appear in decorative arts across centuries before pure Abstract Art emerges in the 20th century, and Conceptual Art challenges the very definition of art in a way earlier periods couldn't have imagined. While this overview focuses primarily on Western visual art from the Gothic period onwards, remember it's just one thread in a much larger global textile. Our History of Art Guide offers broader context. Honestly, trying to pin down every style is a fool's errand, and this is by no means an exhaustive encyclopedia, but getting familiar with the big players makes navigating the art world much less intimidating.

Before Gothic: Laying the Groundwork

Before the soaring cathedrals of the Gothic era pierced the sky, European art already had deep roots. Skipping straight to Gothic is like starting a movie halfway through – you miss crucial character development! Two major styles set the stage, building on earlier classical and regional traditions:

- Byzantine Art (c. 4th Century - 1453): Flourishing in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium), centered in Constantinople (modern Istanbul), this style was heavily influenced by its position linking Europe and Asia. It's known for its rich, often gold-background mosaics (like those in Ravenna, Italy, or Hagia Sophia), stylized religious icons with elongated figures and serene, otherworldly expressions, and grand domed architecture. Think less about realism and more about conveying spiritual authority and divine mystery. The figures often feel flat and symbolic, floating in a golden haze – designed to inspire awe and contemplation, not necessarily to replicate earthly appearances. Representation of human figures in religious contexts was often discouraged due to concerns about idolatry, which pushed artists to focus their incredible skill on intricate patterns, symbolism, and conveying spiritual essence rather than earthly likeness. There's an enduring spiritual power and visual richness to Byzantine art that feels so distinct from modern aesthetics; it transports you to a different mindset. Its influence stretched far, impacting Russian Orthodox art and even elements of early Italian painting. A key example is the Mosaics of San Vitale in Ravenna, where the figures of Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora, though stylized, convey immense imperial and divine authority through their gaze and rich robes. The primary purpose of Byzantine art was often religious devotion and the glorification of the divine and imperial power.

- Romanesque Art (c. 1000 - 12th Century): Dominating Western Europe before the Gothic, Romanesque art and architecture feel solid, grounded, and often quite robust. Think massive stone churches with rounded arches (borrowed from Rome, hence the name!), thick walls, barrel vaults, and relatively small windows. Sculpture, often found carved into church portals (like at Saint-Lazare in Autun, France) or on capitals topping columns, tends to be quite stylized, energetic, and sometimes almost cartoonish in its storytelling, focusing on biblical narratives and moral lessons. Figures can be distorted to fit the architectural space or to emphasize emotional impact. Compared to Byzantine elegance, Romanesque often feels earthier, more muscular – built to last and impress through sheer solidity. That sense of sheer, unadorned power is quite compelling. A notable example is the Tympanum of the Last Judgment at Autun Cathedral, where the sculptor Gislebertus uses dramatic distortions and expressive lines to convey the terror and awe of judgment day, making the figures feel intensely alive despite their stylized forms. The main purpose of Romanesque art was often to educate a largely illiterate populace about biblical stories and Christian doctrine through visual means, as well as to create imposing structures for worship.

Understanding these precursors helps you appreciate how Gothic builders reached for the heavens – they were literally building upon (and reacting against) the solid foundations and spiritual focus of what came before.

International Gothic (c. Late 14th - Early 15th Century)

Bridging the late Gothic and early Renaissance, the International Gothic style was a courtly, elegant phase that spread across Europe. It blended elements from Northern Europe (meticulous detail, rich colors, interest in naturalism) and Italy (increasing spatial awareness, graceful figures). Think of beautifully illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings featuring elongated, graceful figures, elaborate costumes, and detailed depictions of nature, often set in idealized landscapes or courtly interiors. It's a style that feels refined, decorative, and focused on beauty and narrative clarity, often commissioned by wealthy patrons and royalty. The Limbourg brothers' Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is a prime example, with its exquisite detail, vibrant colors, and charming depictions of aristocratic life and peasant labor across the seasons. International Gothic built on the naturalism of late Gothic while adding a new level of elegance, detail, and international exchange.

- Characteristics: Elegant, elongated figures; rich colors and decorative patterns; meticulous detail (especially in nature and textiles); increasing naturalism and spatial awareness; focus on courtly life, religious narratives, and nature. It's art that feels precious and refined, like a jewel box. The primary purpose was often to serve as devotional objects or status symbols for wealthy patrons and royalty, showcasing piety and refined taste.

- Key Artists/Works: Limbourg brothers (Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry), Simone Martini, Gentile da Fabriano (Adoration of the Magi).

Proto-Renaissance (c. Late 13th - Early 14th Century)

Also bridging the gap, primarily in Italy, the Proto-Renaissance saw artists beginning to experiment with greater realism, emotion, and spatial depth, laying crucial groundwork for the Renaissance proper. Figures started to gain weight and volume, appearing more grounded and human. Think of artists like Cimabue and Duccio, who began to move away from strict Byzantine conventions, and especially Giotto, often considered a key figure for his revolutionary approach to depicting figures with emotional intensity and creating a sense of three-dimensional space on a flat surface. His frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua are a prime example, showing figures with believable weight and dramatic interactions. It feels like art is starting to breathe, doesn't it? The primary purpose was still largely religious, but with a new emphasis on conveying biblical stories with greater human drama and emotional resonance.

- Characteristics: Increased naturalism compared to Byzantine/Gothic; figures gaining weight and volume; early attempts at creating spatial depth; focus on human emotion and narrative clarity. It's like seeing the first hints of spring after a long winter. The primary purpose was religious, aiming to make biblical narratives more relatable and emotionally impactful through increased realism.

- Key Artists/Works: Giotto (Scrovegni Chapel frescoes), Cimabue, Duccio.

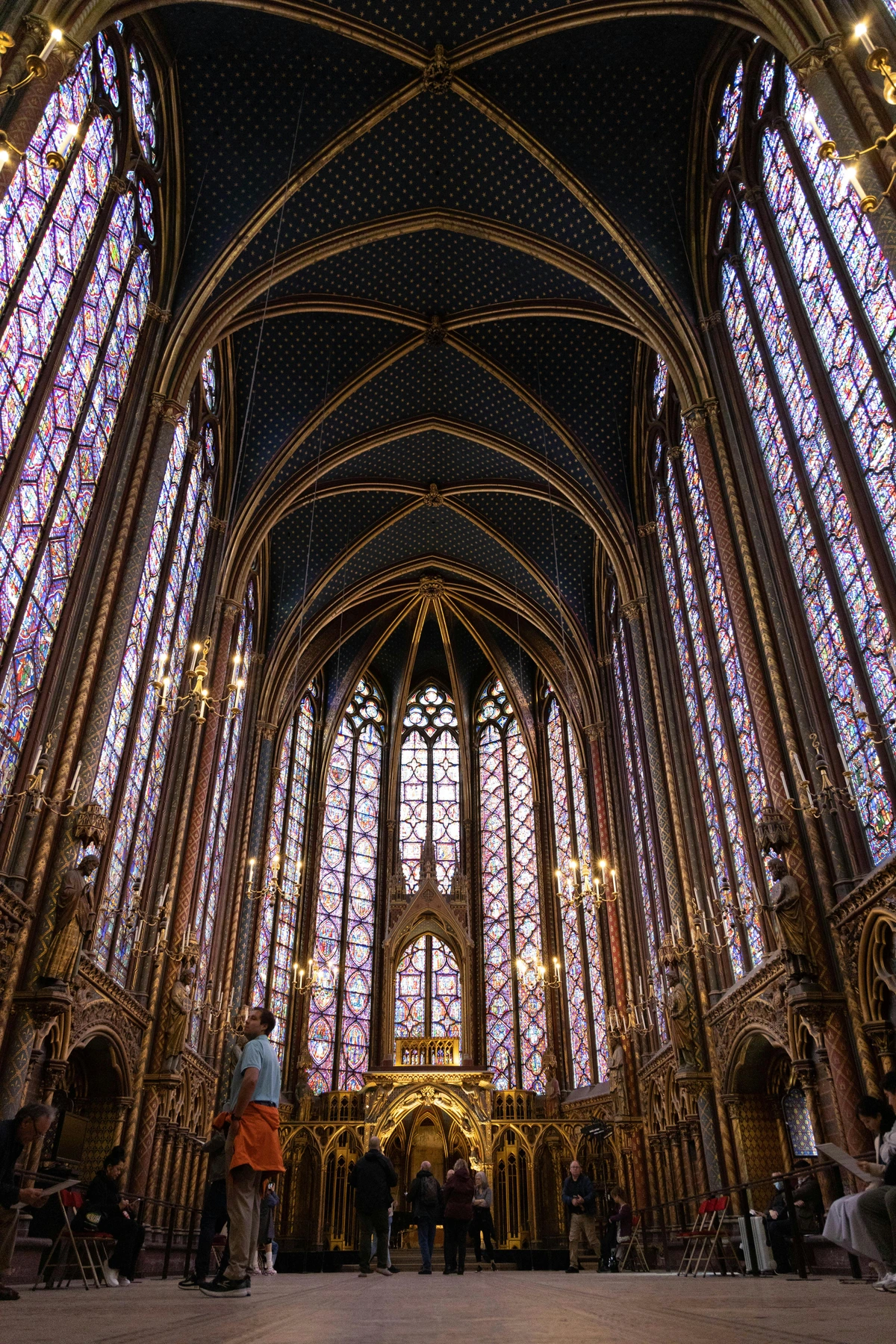

Gothic Art (c. 12th - 15th Century)

Emerging in Northern France, this style is perhaps most famous for its architecture (think soaring cathedrals like Notre Dame in Paris, Reims, or Cologne), but also influenced sculpture, painting, and manuscript illumination. The sculptural programs on cathedral facades, like the portal sculptures at Chartres Cathedral, became increasingly naturalistic over time, telling biblical stories to a largely illiterate populace – a key development paving the way for the Renaissance's focus on realism. It aimed for height, light (thanks to stained glass), and often, a strong sense of divine drama. The detailed narratives and exquisite craftsmanship in illuminated manuscripts, like those by the Limbourg brothers (Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry), really show the era's devotion and skill – makes my grocery list look rather pathetic. Gothic art built upon Romanesque solidity but aspired to greater verticality and light, creating spaces designed to elevate the spirit towards the divine.

- Characteristics: Pointed arches, ribbed vaults, flying buttresses (in architecture) allowing for thinner walls and larger windows; elongated and stylized figures in sculpture and painting (though becoming more naturalistic than Romanesque); increased naturalism compared to earlier periods; rich color, especially in stained glass. You kind of feel small and awestruck looking up in a Gothic cathedral, which was probably the point. It's architecture that feels like it's trying to float. The primary purpose was the glorification of God and the Virgin Mary, creating awe-inspiring spaces for worship and visually narrating religious stories.

Renaissance (c. 14th - 16th Century)

After the spiritual heights of the Gothic, a new focus emerged. Meaning "rebirth," this period, originating in Italy, marked a revival of interest in the classical art and ideals of Ancient Greece and Rome. It emphasized humanism, naturalism, and scientific inquiry. It’s where artists started becoming famous as individual geniuses. Getting perspective right suddenly became a really big deal – they were figuring out how to make flat surfaces look convincingly three-dimensional using linear perspective, which sounds basic now but was revolutionary then. They also developed techniques like sfumato (Leonardo da Vinci), the subtle blending of colors or tones so subtly that they melt into one another without perceptible transitions, creating soft, hazy effects, and refined chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark, notably mastered by Caravaggio later, but used effectively in the Renaissance to model forms and create drama). We often distinguish between the Early Renaissance (experimental phase, think Donatello, Botticelli) and the High Renaissance (peak mastery, the big three: Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael). And yes, they really were that good. Architects like Filippo Brunelleschi, figuring out the dome for Florence Cathedral, were engineering rock stars of their time. The Late Renaissance saw the emergence of Mannerism as a reaction. The Renaissance built on the increasing naturalism of the late Gothic but added a new intellectual rigor and focus on human potential, drawing inspiration from antiquity and fueled by archaeological discoveries like the rediscovery of ancient Roman sites like Pompeii and Herculaneum, which provided direct inspiration for classical forms and motifs.

- Distinguishing Features:

- Italian Renaissance: Focused heavily on humanism, classical proportion, anatomical accuracy, linear perspective. Florence and Rome were key centers. Key artists include Leonardo da Vinci (Mona Lisa), Michelangelo (David, Sistine Chapel ceiling), Raphael (School of Athens), and Titian (Venetian School). Early on, a key distinction emerged between the Central Italian focus on disegno (drawing/design, emphasizing line and form) and the Venetian School's emphasis on colore (color, prioritizing the effects of light and pigment). This wasn't just a technical difference; it reflected different artistic philosophies. Think of Raphael's School of Athens, a masterpiece of perspective and balanced composition, celebrating classical philosophy and human intellect. The primary purpose was often to celebrate humanism, classical ideals, and religious themes with newfound realism and technical mastery, commissioned by wealthy patrons, the Church, and civic bodies.

- Northern Renaissance (Flanders, Netherlands, Germany): While also interested in realism, artists like Jan van Eyck (Arnolfini Portrait) or Albrecht Dürer (Melencolia I) often emphasized meticulous detail, surface textures, complex symbolism, and developed oil painting techniques to achieve luminous effects. Less focus on classical antiquity initially, more on intense observation of the natural world and everyday life alongside religious themes. Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait, for example, is famous for its incredible detail, from the textures of fabric and fur to the tiny reflection in the mirror, making the everyday feel sacred. The primary purpose often included detailed religious scenes, portraits, and genre scenes for a growing merchant class, showcasing technical skill and symbolic depth.

- Characteristics: Realism and naturalism in depicting human anatomy and emotion; development of linear perspective (creating the illusion of depth on a flat surface); harmony, balance, and proportion; influence of classical mythology and Christian themes. Think Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael – the ninja turtles of art history, basically. Plus, that calm, almost idealized beauty that makes everything look rather noble. The primary purpose was to celebrate humanism, classical ideals, and religious themes with newfound realism and technical mastery.

- Key Artists/Architects: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian (Venetian School), Jan van Eyck (Northern Renaissance), Albrecht Dürer (Northern Renaissance), Brunelleschi (architecture).

Mannerism (c. 1520 - 1600)

Bridging the High Renaissance and the Baroque, Mannerism emerged in Italy as a reaction against the harmonious ideals associated with artists like Raphael. Think elongated figures, weird postures, and slightly unsettling color palettes – it's like the Renaissance artists decided to get a bit weird and dramatic before the Baroque fully took over. I find it fascinatingly awkward sometimes, full of artificial qualities, stylized poses, and ambiguous settings. It's less naturalism, more style for style's sake. It feels awkward or unsettling precisely because it deliberately departs from the Renaissance ideals of balance and naturalism, perhaps reflecting the period's political and religious upheaval. Figures are twisted into unnatural poses, space is compressed or distorted, and colors can be jarringly bright or sickly. It's art that feels self-conscious and virtuosic, showing off the artist's skill while creating a sense of unease. Pontormo's Descent from the Cross, for instance, features figures with strangely elongated limbs and contorted bodies, arranged in a swirling, gravity-defying composition with acidic pinks and greens. Mannerism reacted against the perceived perfection of the High Renaissance by introducing tension, artificiality, and emotional complexity. Does this deliberate departure from harmony feel like a refreshing push against convention, or just... well, mannered? It certainly makes you look twice.

- Characteristics: Elongated limbs, exaggerated musculature, stylized facial features, unusual perspectives, acidic or artificial colors, complex allegories, emotional intensity bordering on the theatrical. The primary purpose was often to showcase the artist's virtuosity and inventiveness, appealing to sophisticated patrons who appreciated its departure from classical norms.

- Key Artists: Pontormo (Descent from the Cross), Bronzino (Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo and Her Son), Parmigianino (Madonna with the Long Neck), El Greco (late period - The Burial of the Count of Orgaz).

Baroque (c. 1600 - 1750)

Following the Renaissance (and Mannerism), Baroque art, originating in Italy, embraced drama, emotion, and grandeur. Often associated with the Counter-Reformation (the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation, seeking to reassert its power and inspire piety through awe-inspiring art) and absolute monarchies, it aimed to awe and inspire. If the Renaissance was about calm perfection, Baroque was about the wow factor. It wasn't monolithic, though; Italian Baroque (Caravaggio, Bernini) often had intense religious drama and dramatic chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark that creates drama and volume), Dutch Baroque (Rembrandt, Vermeer) focused more on domestic scenes and portraits with incredible light, Spanish Baroque (Velázquez) balanced realism with royal grandeur, and French Baroque (Poussin, Palace of Versailles) leaned towards classical order mixed with opulence. You also had the Venetian School continuing strong, with artists like Tiepolo known for their light-filled, decorative frescoes and emphasis on colore (color) over disegno (design/drawing) - a characteristic often associated with Venetian art since the Renaissance. Different flavors of spectacular, you might say. Which flavor resonates most with you – the intense drama of Italy, the quiet light of the Netherlands, the solemn grandeur of Spain, or the opulent spectacle of France? Baroque art built on the emotional intensity of Mannerism but channeled it into grand, dynamic compositions designed to engage the viewer viscerally. Makes my studio look rather minimalist by comparison!

- Characteristics: Dynamic movement, intense emotions, rich color, dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro - the strong contrast between light and dark that creates drama and volume), ornate decoration, often large scale. Walking into a Baroque church can feel overwhelming, like stepping into a gold-plated opera set designed to blow your mind. Caravaggio's The Calling of Saint Matthew is a prime example of chiaroscuro, where a single beam of light dramatically illuminates Christ and Peter pointing towards Matthew in a dark tavern, highlighting the moment of divine calling. The primary purpose varied, from serving the Counter-Reformation by inspiring piety and devotion, to glorifying monarchs and states, and catering to the tastes of a wealthy merchant class with portraits and genre scenes.

- Key Artists: Caravaggio (The Calling of Saint Matthew), Rembrandt (The Night Watch), Peter Paul Rubens (The Elevation of the Cross), Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Ecstasy of Saint Teresa), Velázquez (Las Meninas), Tiepolo (late Baroque/Rococo - Venetian School).

Rococo (Early to Mid-18th Century)

Originating in France, Rococo was a lighter, more ornate and playful reaction against the heavy grandeur of Baroque. Often associated with the aristocracy, it favored intimate scenes, pastel colors, and elaborate decoration. Think fancy parties and flirtatious encounters. It's like Baroque's younger, more frivolous sibling who just wants to have fun. Does this perceived frivolity diminish its artistic merit, or does it make it charming in its own right? It certainly offers a different kind of beauty. Fragonard's The Swing perfectly captures the feeling – a young woman kicks off her shoe while swinging in a lush garden, her suitor hidden below, all rendered in soft pastels and delicate brushwork, evoking a sense of playful romance and secrecy. Rococo softened the drama of the Baroque, focusing on elegance, charm, and pleasure.

- Characteristics: Light colors (pastels), asymmetrical designs, curved lines ('S' curve), themes of love, nature, and lighthearted entertainment; emphasis on decoration and intricate detail. The primary purpose was to adorn aristocratic interiors and depict scenes of leisure and romance, reflecting the refined tastes of the French court and elite.

- Key Artists: Jean-Antoine Watteau (Pilgrimage to Cythera), François Boucher (The Toilet of Venus), Jean-Honoré Fragonard (The Swing).

Neoclassicism (Mid-18th - Early 19th Century)

After the party, it was time to get serious again. A return to the perceived order, reason, and seriousness of classical Greek and Roman art, reacting against the perceived frivolity of Rococo. Often associated with the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, it originated in Rome and emphasized virtue, patriotism, and rationality. This return to classical forms also manifested strongly in architecture (Neoclassical architecture), think grand public buildings with columns and domes – like putting a Roman temple facade on your bank (think the Panthéon in Paris or Monticello in the US). Key figures like Jacques-Louis David used classical subjects to convey contemporary political messages, as seen in his iconic Oath of the Horatii. This renewed interest in antiquity was significantly fueled by archaeological discoveries, particularly the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which provided artists and designers with a wealth of authentic classical examples. Does this emphasis on reason and order feel refreshing after the drama and playfulness of the preceding styles, or does it feel a bit stifling? It makes you question whether art needs to be serious or virtuous, or if diverse expression is the point. David's Oath of the Horatii exemplifies the style with its clear lines, shallow space, stoic male figures taking an oath, and dramatic but restrained emotion, all drawn from Roman history to inspire revolutionary fervor. Neoclassicism rejected Rococo's ornamentation and embraced the perceived rationality and moral seriousness of antiquity.

![]()

- Characteristics: Emphasis on line and form; restrained emotion; themes from classical history and mythology; clarity, simplicity, and symmetry. Think heroic poses and stoic expressions. The primary purpose was often didactic and moralistic, promoting civic virtue, patriotism, and rationality, serving the ideals of the Enlightenment and revolutionary movements.

- Key Artists: Jacques-Louis David (Oath of the Horatii), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (La Grande Odalisque), Antonio Canova (Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss), Peter von Cornelius (The Israelites Resting in the Desert).

Romanticism (Late 18th - Mid-19th Century)

Reacting against Neoclassicism's emphasis on reason, Romanticism, originating across Europe (especially Germany, England, and France), championed emotion, individualism, imagination, and the power of nature. It explored themes of awe, horror, sublime beauty, and the exotic. Basically, all the feelings Neoclassicism tried to keep bottled up. Think dramatic shipwrecks like Géricault's Raft of the Medusa or Turner's turbulent seas. This era also saw the rise of specific Regional Schools, like the Hudson River School in America (Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand), who applied Romantic ideals to grand depictions of the American landscape. It's like saying, "Our mountains are just as sublime as your Alps, thank you very much!" The power of emotion in art, whether awe-inspiring or terrifying, really resonates with viewers; it taps into something fundamental about the human experience. I know I find immense inspiration and a sense of awe when I'm surrounded by nature, and seeing artists capture that feeling is powerful. While it championed intense emotion, Romanticism wasn't always dramatic; it also encompassed quiet contemplation of nature or individual introspection, reflecting the diverse ways artists experienced and expressed feeling. Géricault's Raft of the Medusa is a powerful example, depicting the raw emotion and suffering of shipwreck survivors with dramatic lighting and composition, focusing on a contemporary tragedy rather than a classical ideal. Romanticism offered an emotional counterpoint to Neoclassicism's rationality, celebrating subjective experience and the power of the natural world.

![]()

- Characteristics: Intense emotion, dramatic scenes (often historical or contemporary events), emphasis on nature's power (sometimes threatening), interest in the medieval and the exotic, looser brushwork than Neoclassicism. It's art that wants you to feel something big. The primary purpose was to express intense emotion, explore the sublime in nature, celebrate individualism and imagination, and sometimes engage with contemporary political events through a dramatic lens.

- Key Artists: Eugène Delacroix (Liberty Leading the People), Caspar David Friedrich (Wanderer above the Sea of Fog), J.M.W. Turner (The Fighting Temeraire), Francisco Goya (The Third of May 1808), Théodore Géricault (The Raft of the Medusa), Thomas Cole (Hudson River School - The Oxbow).

Realism (Mid-19th Century)

As the industrial age roared on, a different kind of reaction was brewing in France. Reacting against Romanticism's idealization, Realism sought to portray contemporary subjects and situations with truth and accuracy, including the unpleasant aspects of life. No more heroes on horseback (unless they looked really tired). It was about showing life as it actually was, warts and all, for ordinary people. Courbet really wasn't messing around; his painting The Stone Breakers (sadly now lost) showed the harsh reality of labor without any sugar-coating, depicting ordinary workers in a straightforward, unheroic manner. Across the Channel, the Barbizon School in France (Millet, Rousseau) focused on realistic depictions of rural life and landscape, influencing later movements. There's a certain bravery or importance in depicting everyday life truthfully, isn't there? It forces us to look at the world around us, not just idealized versions. Think of it as American Realism hitting the bustling streets. There's a raw energy and wealth of human stories found in urban environments that these artists captured so well, a feeling I connect with when I see the vibrant chaos of a city street. Realism rejected Romanticism's focus on emotion and the exotic, turning instead to the observable, often challenging, realities of contemporary life.

- Characteristics: Unidealized subjects (often working class), focus on everyday life, accurate detail, sometimes social commentary. Painterly brushwork here tends to be visible but serves to capture texture and form accurately, unlike the more expressive brushwork of Romanticism or the later Impressionism. The primary purpose was to depict contemporary life truthfully, often with a focus on social issues and the working class, challenging academic conventions and Romantic idealism.

- Key Artists: Gustave Courbet (The Stone Breakers), Jean-François Millet (The Gleaners), Honoré Daumier (printmaker, painter - The Third-Class Carriage).

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (c. 1848 - late 19th Century)

Okay, a bit of a detour back in time, overlapping with Realism but with a different vibe entirely. This British group rejected the Mannerist-influenced art taught at the Royal Academy (seeing Raphael as the point where art took a 'wrong turn'). They aimed for the detail, intense color, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian art (Italian art from the 1400s, before Raphael), often tackling literary, historical, or religious themes with a kind of intense, jewel-like realism and symbolism. Think medieval knights, tragic heroines like Millais' Ophelia floating amongst painstakingly rendered riverbank flora, and incredibly detailed nature. It's very earnest, sometimes a bit dramatic, and the level of detail is frankly astonishing – you feel you could count every blade of grass. It makes you wonder about the dedication (or perhaps obsession?) required for such painstaking work. They also had connections to the Aesthetic Movement and Symbolism, sharing an interest in beauty for its own sake, complex symbolism, and literary themes. Millais' Ophelia is a perfect example, with its almost photographic detail of the plants and water, contrasting with the tragic, symbolic subject matter drawn from Shakespeare. The Pre-Raphaelites reacted against academic conventions by looking back to earlier Renaissance art for inspiration, combining intense realism with symbolic themes.

- Characteristics: High detail, intense colors, complex compositions, subjects from literature (Shakespeare, Keats), mythology, religion, and medieval themes; strong emotional content, often moralistic or sentimental. The primary purpose was to reform art by rejecting academic norms and returning to what they saw as the sincerity and detail of early Renaissance art, often conveying moral or literary narratives.

- Key Artists: Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Proserpine), John Everett Millais (Ophelia), William Holman Hunt (The Light of the World).

Arts and Crafts Movement (c. 1880 - 1920)

Around the same time, but shifting focus from painting to design, came the Arts and Crafts Movement. Less a single style, more an international design philosophy reacting against industrial production. Led by figures like William Morris in Britain, it championed traditional craftsmanship, simple forms, and often used medieval, romantic, or folk styles of decoration. It aimed to reunify art and craft, believing beautiful, well-made objects improved society. Think handcrafted furniture, textiles, wallpaper with intricate natural motifs – the opposite of mass-produced stuff. There's a real integrity to it, a sense of valuing the maker's hand. In today's world of mass production, there's a renewed appreciation for the value of handmade objects, isn't there? Its influence can be seen in later movements like Art Nouveau and even Modernism's emphasis on functional design. It also sparked important conversations about the value of craft vs. fine art, a distinction that has blurred considerably over time, thankfully. The Arts and Crafts movement reacted against industrialization by advocating for a return to traditional craftsmanship and the integration of art into everyday life.

- Characteristics: Emphasis on craftsmanship, traditional techniques (woodworking, weaving, printing), simple forms, stylized natural motifs, integration of art into everyday objects, often socialist undertones (critique of industrial labor). The primary purpose was to reform design and manufacturing, promoting the value of skilled craftsmanship and creating beautiful, functional objects accessible (ideally) to a wider audience, as a reaction against the perceived poor quality and dehumanizing effects of industrial production.

- Key Figures: William Morris (textiles, wallpaper), Charles Rennie Mackintosh (also Art Nouveau related - furniture, architecture), Gustav Stickley (American Craftsman style - furniture).

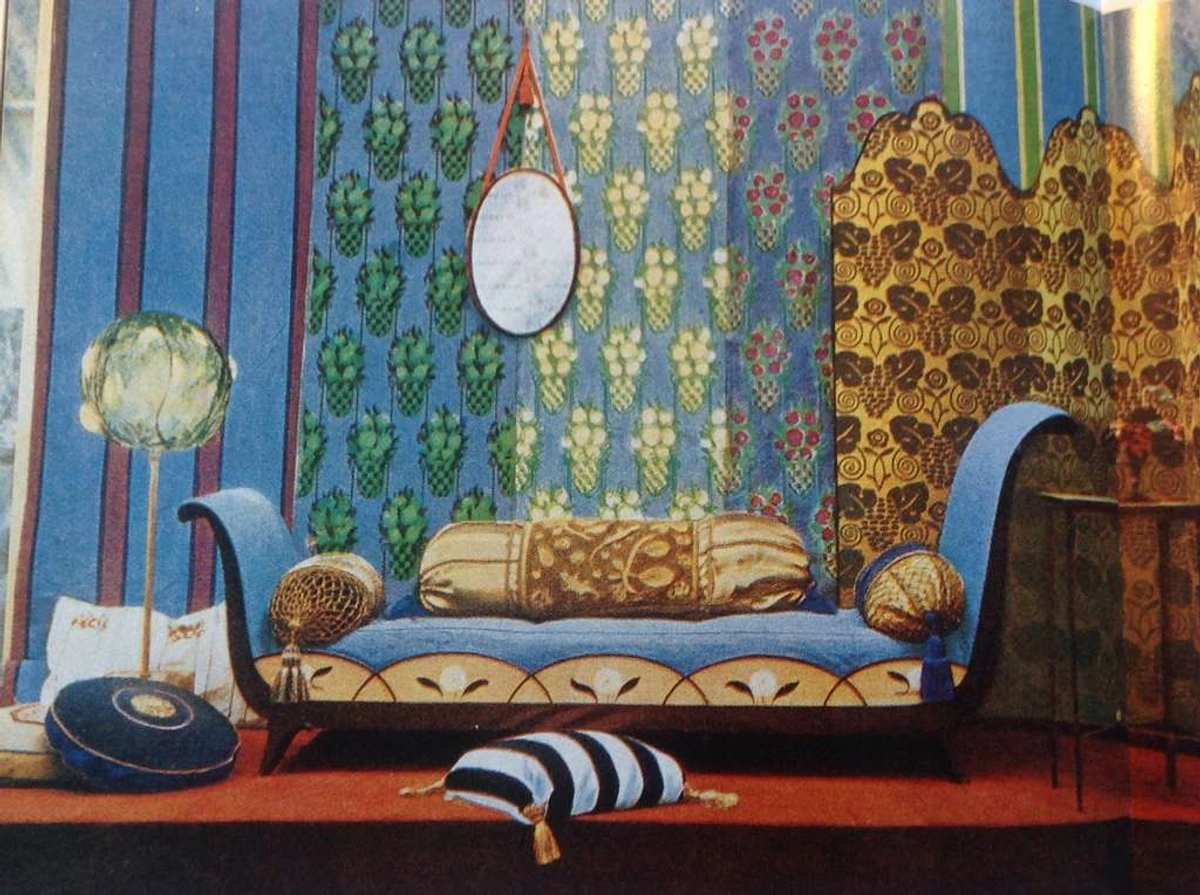

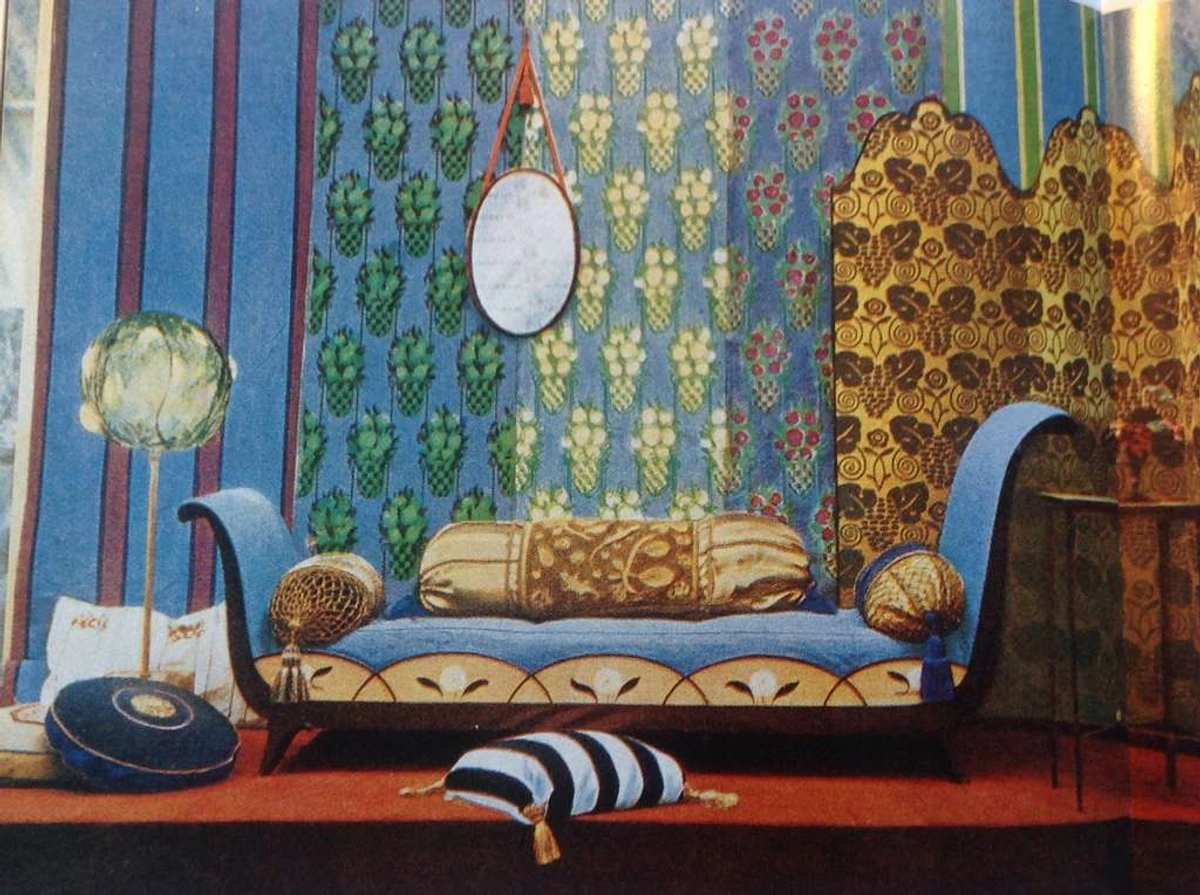

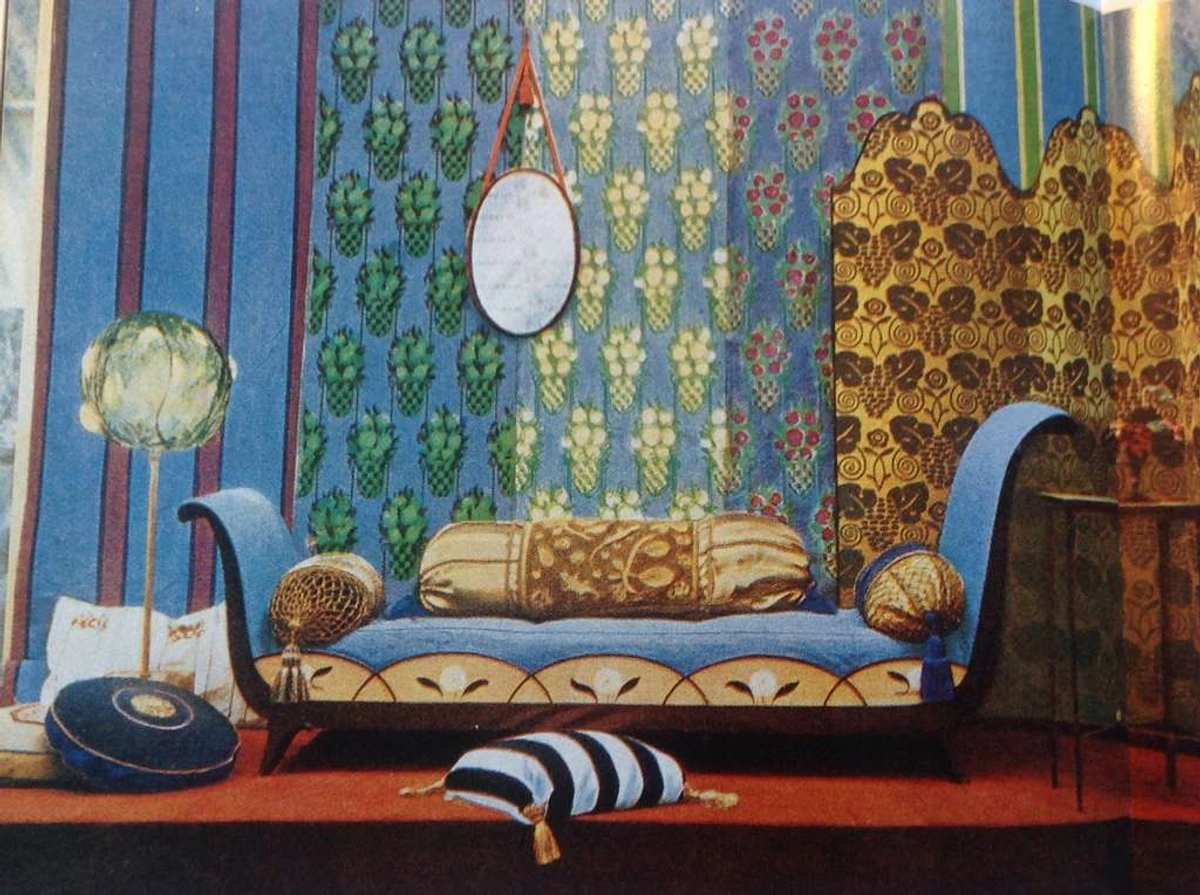

Note: The image below shows an Art Deco interior, a style that emerged later but was influenced by Art Nouveau's emphasis on modern design and decorative arts.

Impressionism (c. 1870s-1880s)

After the intense focus on detail and social commentary, artists began craving something different. Originating in France, Impressionism focused on capturing the fleeting impression of a moment, particularly the effects of light and color. It was revolutionary – critics initially hated it, which is often a good sign in art history. It's easy to love Impressionism now, but imagine seeing it for the first first time – all blurry and unfinished-looking! It must have felt like looking at the world through rain-streaked glasses after centuries of crisp detail. It really captures that feeling of a moment, doesn't it? The influence of Japonisme – the fascination with Japanese art (especially Ukiyo-e prints) that swept Europe in the late 19th century – is visible here, in the flattened perspectives, asymmetrical compositions, and focus on everyday scenes seen in works by Degas and others. Revolutionary ideas in art are often initially met with resistance, a pattern we see repeated throughout history, even with contemporary art today. As an artist, trying to capture fleeting light is a constant challenge and joy. Impressionism reacted against the academic focus on historical subjects and precise detail, turning instead to modern life and the subjective experience of seeing.

![]()

- Characteristics: Visible, often short painterly brushstrokes (applied loosely and quickly to capture the fleeting moment, unlike the tighter brushwork of Realism); emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities; ordinary subject matter; inclusion of movement; often painting en plein air (outdoors) to capture direct light and atmosphere. Monet's Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise) is the painting that gave the movement its name, capturing the hazy, atmospheric effect of the sun rising over the harbor with loose, visible brushstrokes. The primary purpose was to capture the fleeting moment and the subjective visual experience of light and color, often depicting scenes of modern life, landscapes, and leisure activities.

- Key Artists: Claude Monet (Impression, soleil levant, Water Lilies series), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Bal du moulin de la Galette), Edgar Degas (dancers, racehorses), Camille Pissarro (landscapes, cityscapes), Alfred Sisley (landscapes), Gustave Caillebotte (Paris Street; Rainy Day), Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt.

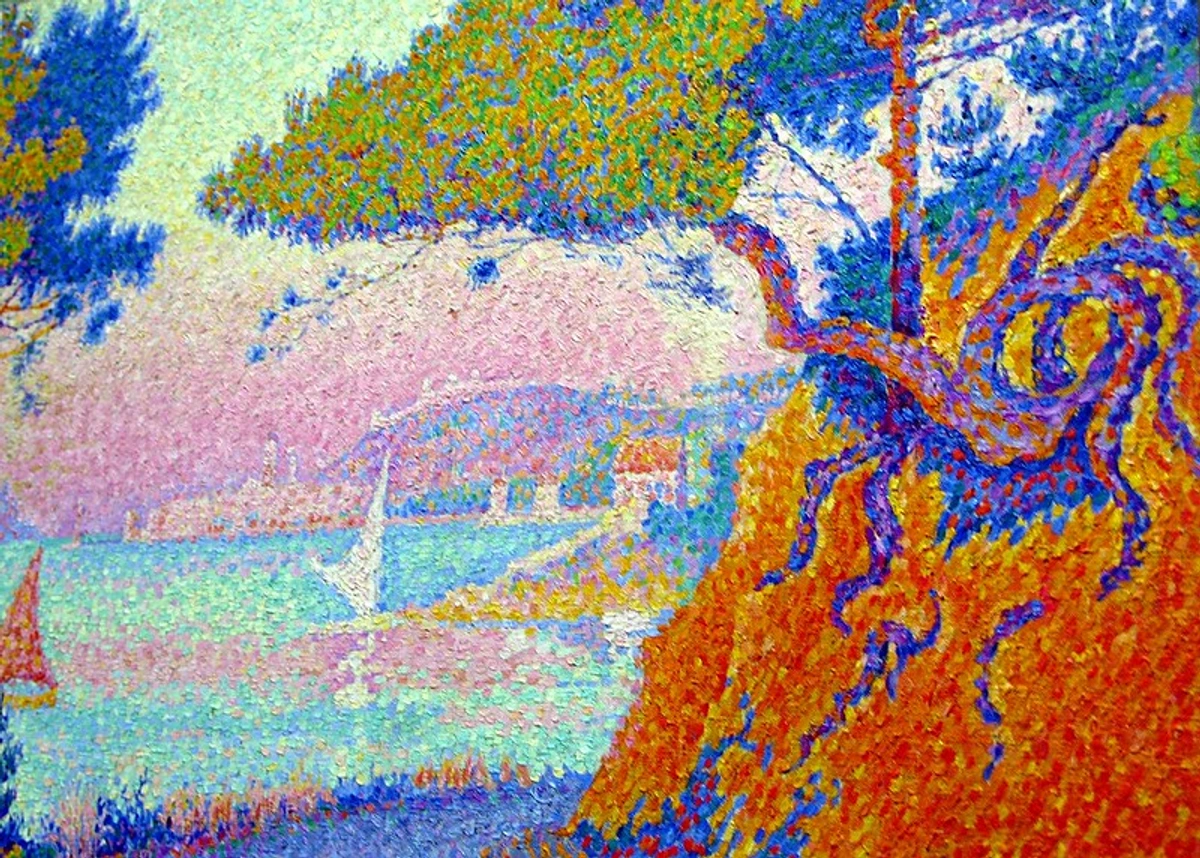

Post-Impressionism (c. 1886-1905)

After the Impressionists broke the mold, the artists who followed took things in different directions. Not a single style, but a term encompassing diverse artists, primarily in France, who emerged after Impressionism, pushing its boundaries. They liked Impressionism's color but wanted more substance, structure, or emotion. It’s less a unified movement and more a collection of brilliant individuals going their own way, using Impressionism as a launchpad. This highlights the power of individual vision after a collective movement has paved the way. The impact of Japonisme continued here too, notably in the flat planes and bold outlines of Gauguin or the decorative patterns found in Van Gogh's backgrounds. Post-Impressionism built on Impressionism's use of color and modern subject matter but sought to add greater structure, symbolism, or emotional intensity.

![]()

- Characteristics: Varied widely – symbolic and personal meanings (Gauguin), emphasis on structure and form (Cézanne), heightened color and emotional expression (Van Gogh), scientific approach to color (Seurat, Signac - Pointillism). Cézanne's Mont Sainte-Victoire series, for example, shows his focus on breaking down forms into geometric components and building up the image with structured brushstrokes, laying groundwork for Cubism. The primary purpose was diverse, ranging from exploring the scientific application of color (Pointillism) to conveying subjective emotional states or symbolic meanings, often seeking more structure or permanence than Impressionism.

- Key Artists: Vincent van Gogh (The Starry Night), Paul Gauguin (Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?), Paul Cézanne (Mont Sainte-Victoire series), Georges Seurat (A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte), Paul Signac (The Port of Saint-Tropez), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (posters, Parisian nightlife).

Symbolism (c. 1880s - 1910)

Overlapping with Post-Impressionism, Symbolism offered a different path away from objective reality. Reacting against Realism and Impressionism, Symbolism, originating in France and Belgium, prioritized ideas, emotions, and subjective experience over objective reality. Artists used symbols, myths, dreams, and imagination to suggest deeper meanings. It's often mysterious, sometimes a bit spooky or decadent, and feels like a doorway into the subconscious, paving the way for Surrealism later on. The enduring human fascination with dreams and the subconscious makes Symbolism feel timeless. If you find hidden meanings intriguing, learn How to Understand Symbolism: A Practical Guide to Interpretation. Gustave Moreau's The Apparition is a classic Symbolist work, depicting a biblical scene (Salome and the head of John the Baptist) with intense detail and jewel-like colors, creating a sense of decadent, dreamlike mystery rather than historical accuracy. Symbolism rejected the focus on external reality found in Realism and Impressionism, turning inward to explore the realm of ideas and emotions.

- Characteristics: Emphasis on suggestion rather than direct description, use of symbolic imagery, interest in mythology, dreams, spirituality, and the exotic; often subjective and personal interpretations. The primary purpose was to express subjective experience, emotions, and ideas through symbolic means, often exploring themes of spirituality, myth, and the subconscious, as a reaction against positivism and materialism.

- Key Artists: Gustave Moreau (The Apparition), Odilon Redon (Cyclops), Edvard Munch (also Expressionist - The Scream), Gustav Klimt (also Art Nouveau - The Kiss), Fernand Khnopff (I Lock My Door Upon Myself).

Art Nouveau (c. 1890-1910)

As the 19th century drew to a close, a new decorative style emerged. An international style of art, architecture, and applied art that first appeared in France just before World War I. It influenced the design of buildings, furniture, jewelry, fashion, cars, etc., combining modern styles with fine craftsmanship and rich materials. Think elegant curves and stylized plant motifs – it aimed to integrate art into everyday life. Major figures included architects like Victor Horta in Brussels, known for his whiplash lines in ironwork and interiors (e.g., Hôtel Tassel), Antoni Gaudí in Barcelona with his fantastical, nature-inspired buildings like Sagrada Familia or Casa Batlló, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow with his distinctive geometric take on the style. In applied arts, think of Tiffany lamps with their stained-glass shades mimicking natural forms, or the posters of Alphonse Mucha. It really tried to make beauty a part of everything, influencing not just posters but also book illustrations, jewelry, and furniture design. I admire the way Art Nouveau integrated beauty into everyday objects, blurring the lines between fine art and design. It feels so organic and flowing, like nature decided to become architecture and furniture. Art Nouveau sought to create a new, modern style that broke from historical revivalism, drawing inspiration from natural forms and integrating art into all aspects of life.

- Characteristics: Whiplash curves (long, sinuous, organic lines), stylized natural forms (plants, flowers, insects), use of modern materials (iron, glass), integration of design across different media (furniture, jewelry, posters, lamps). Feels very elegant, sometimes a bit like nature decided to get really dressed up. The primary purpose was to create a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk) that encompassed all forms of design, bringing beauty and style into everyday objects and architecture, as a reaction against historicism and industrial mass production.

- Key Artists/Designers: Gustav Klimt (The Kiss), Alphonse Mucha (posters), Antoni Gaudí (architecture), Hector Guimard (Paris Metro entrances), Victor Horta (architecture), Charles Rennie Mackintosh (architecture, design), Louis Comfort Tiffany (glass).

Note: The image below shows an Art Deco interior, a style that emerged later but was influenced by Art Nouveau's emphasis on modern design and decorative arts.

Ashcan School (Early 20th Century)

Across the Atlantic, American artists were looking at their own rapidly changing world. Emerging in the US around the turn of the century, these artists focused on depicting gritty, everyday urban life in New York City, often in a painterly, realistic style. They weren't afraid to show the less glamorous side – crowded streets, bars, boxing matches. Think of George Bellows' Stag at Sharkey's capturing the brutal energy of an underground fight club with raw, energetic brushwork. It feels very immediate and journalistic, capturing the energy and sometimes the squalor of the modern city without overt sentimentality. Think of it as American Realism hitting the bustling streets. There's a raw energy and wealth of human stories found in urban environments that these artists captured so well. I connect with that sense of finding beauty and narrative in the everyday hustle and bustle of a city. The Ashcan School brought a focus on urban realism to American art, depicting the unvarnished reality of city life.

- Characteristics: Focus on urban scenes, working-class subjects, painterly brushwork (visible and loose, conveying the immediacy of the scene), often darker palettes, sense of immediacy and observation. The primary purpose was to depict the realities of modern urban life in America, including its less glamorous aspects, as a reaction against academic idealism and genteel subject matter.

- Key Artists: Robert Henri (Snow in New York), George Bellows (Stag at Sharkey's), John Sloan (McSorley's Bar), Everett Shinn, George Luks.

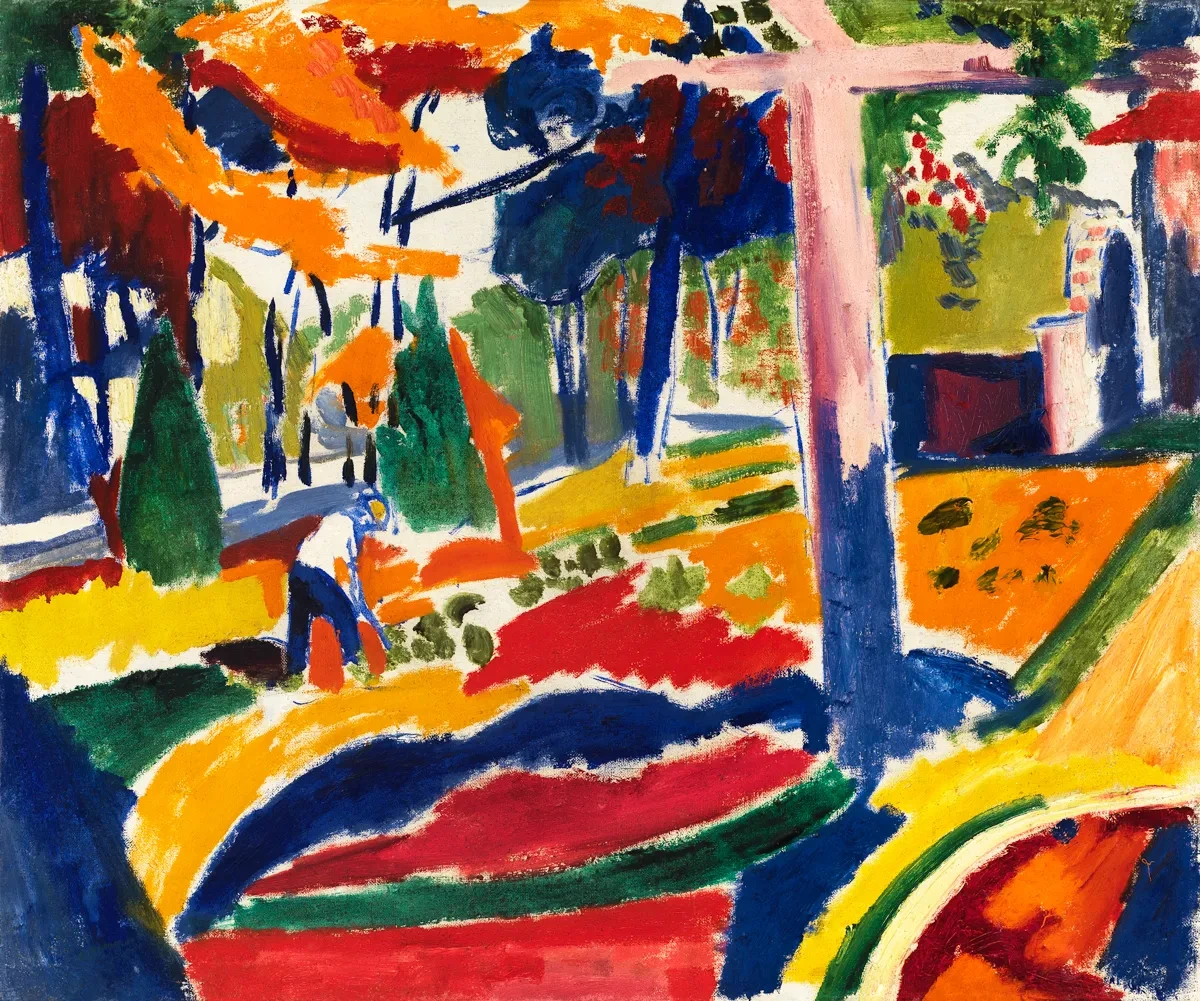

Fauvism (c. 1905-1908)

Back in France, color was about to explode. Originating in France, Fauvism is characterized by strong, vibrant colors and fierce brushwork, prioritizing painterly qualities over representational values. The name means "wild beasts" in French – which tells you something about the initial reaction! The influence of Primitivism – an interest in the art of non-Western cultures (particularly Africa and Oceania) seen as more direct and emotionally expressive – can be detected in the simplified forms and raw energy of some Fauvist works. There's a sheer joy or shock in seeing such bold, non-naturalistic color used purely for expression; it feels incredibly liberating. Fauvism and Expressionism, which followed, shared an interest in color theory and a move away from purely optical perception towards subjective experience, though Fauvism often retained a sense of joy or decorative quality that Expressionism sometimes eschewed for darker themes. Explore more in our Ultimate Guide to Fauvism. Matisse's Woman with a Hat is a prime example, using jarring, non-naturalistic colors like green and purple for a portrait, prioritizing emotional impact and visual energy over realistic depiction. Fauvism pushed the expressive potential of color beyond the descriptive use of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

- Characteristics: Intense, often non-naturalistic color; simplified forms; painterly texture. The primary purpose was to express subjective feeling through the bold, non-naturalistic use of color and vigorous brushwork, prioritizing emotional impact over realistic representation.

- Key Artists: Henri Matisse (Woman with a Hat), André Derain (The Pool of London), Maurice de Vlaminck, Raoul Dufy, Henry Lyman Sayen, Robert Antoine Pinchon.

Expressionism (Early 20th Century)

Originating primarily in Germany, this style aimed to express subjective emotions and responses rather than objective reality. It's art that wears its heart (often a troubled one) on its sleeve. Think intense, raw feeling translated directly onto the canvas, sometimes jarringly so, as in Munch's The Scream. Key groups included Die Brücke (The Bridge - Kirchner, Nolde) in Dresden, known for intense color and angular forms, and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider - Kandinsky, Marc) in Munich, exploring spiritual dimensions and leaning towards abstraction. The power of art to convey deep, sometimes difficult, emotions is profound; Expressionism doesn't shy away from the challenging aspects of the human psyche. Expressionism and Fauvism, which preceded it, shared an interest in color theory and a move away from purely optical perception towards subjective experience, though Expressionism often delved into darker, more psychological themes. Explore more in our Ultimate Guide to Expressionism. Munch's The Scream is perhaps the most iconic Expressionist image, using swirling lines and intense colors to convey a feeling of existential dread. Expressionism built on the emotional intensity seen in Symbolism and Fauvism, focusing on conveying inner feelings through distorted forms and vivid colors.

- Characteristics: Distortion of form for emotional effect; vivid, often jarring colors; swirling or exaggerated brushstrokes; themes of anxiety, alienation, and inner turmoil. It's art that screams (sometimes literally). The primary purpose was to express the artist's inner feelings and subjective experience of the world, often reflecting anxieties and psychological states, as a reaction against naturalism and Impressionism.

- Key Artists: Edvard Munch (The Scream), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (Die Brücke - Street, Dresden), Emil Nolde (Die Brücke), Wassily Kandinsky (Der Blaue Reiter - Composition VIII), Franz Marc (Der Blaue Reiter - Blue Horse I), Egon Schiele (portraits), Oskar Kokoschka, Marsden Hartley.

![]()

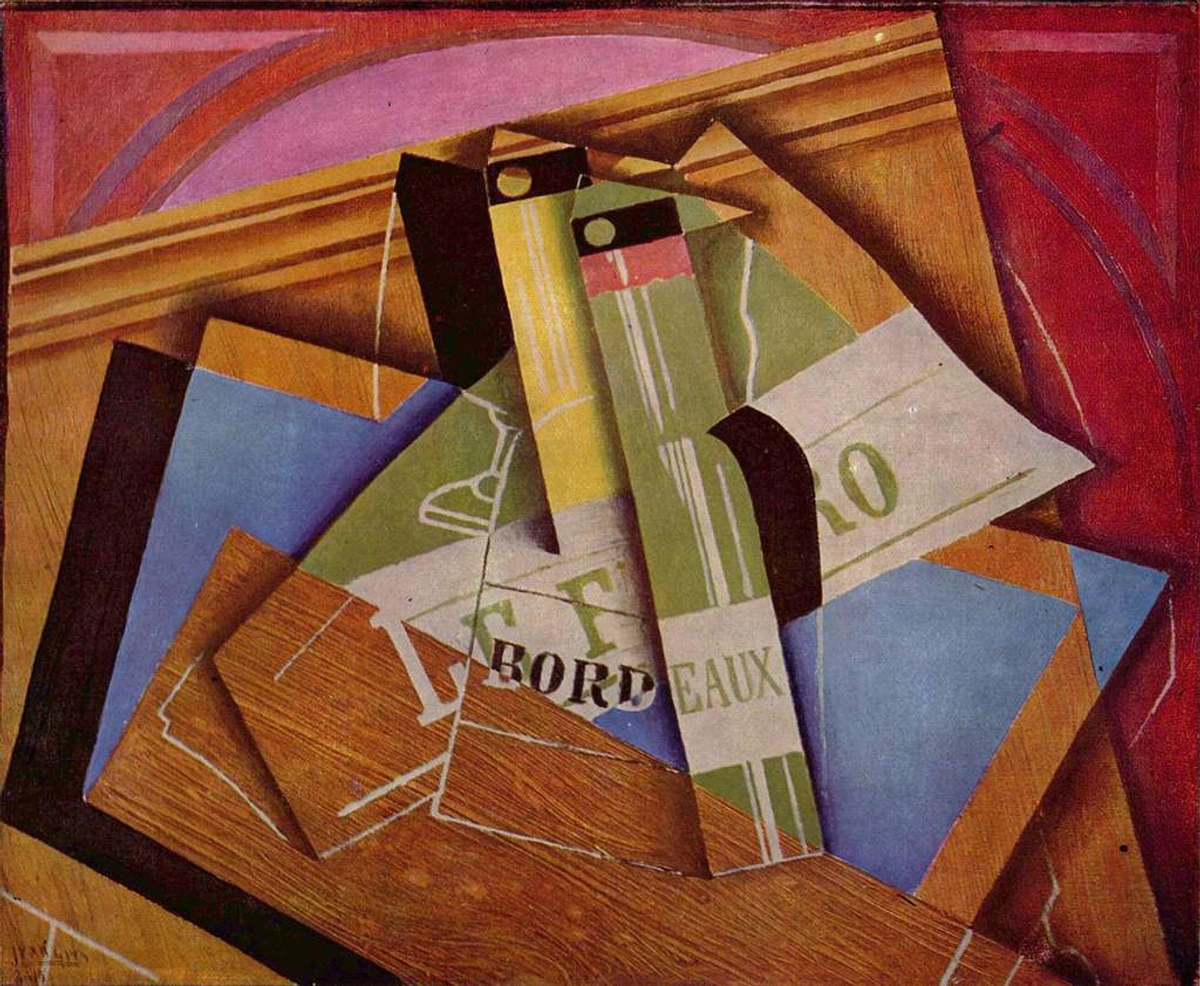

Cubism (c. 1907-1914)

Meanwhile, in Paris, Picasso and Braque were busy shattering reality. Originating in Paris, Cubism revolutionized European painting and sculpture; depicted subjects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, fragmenting objects into geometric forms. It's like seeing all sides of a box at once, shattering the traditional single perspective. Pioneered by Picasso and Braque, works like Picasso's groundbreaking Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) are iconic milestones. Braque's early Cubist landscapes and still lifes were equally crucial in developing the style. The influence of Primitivism, particularly African masks with their abstracted features, is strongly evident in early Cubist works like Les Demoiselles. Cubism fundamentally changed the way we see and depict reality, challenging our conventional understanding of space and form. Explore more in our Ultimate Guide to Cubism.

Cubism is often divided into two phases:

- Analytical Cubism (c. 1908-1912): Objects are broken down into smaller, overlapping facets, analyzed from multiple viewpoints, and reassembled into a fragmented image. The palette is typically restricted to muted tones of browns, grays, and blacks to emphasize form and structure over color. Subjects are often difficult to recognize.

- Synthetic Cubism (c. 1912-1914): This phase simplified forms, used brighter colors, and introduced collage elements like newspaper, wallpaper, or fabric (papier collé). Instead of analyzing objects, artists built up compositions from these fragments, creating flatter, more decorative effects.

Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon is a key example, depicting five female nudes with fragmented bodies and mask-like faces, showing multiple viewpoints simultaneously and drawing heavily on Iberian and African art. Juan Gris's Still Life with a Bottle of Bordeaux is a good example of Synthetic Cubism, using flatter, more distinct shapes and incorporating text. Cubism broke from the tradition of single-point perspective, offering a radical new way to represent form and space.

- Characteristics: Geometric shapes, interlocking planes, depiction from multiple viewpoints; muted palettes (Analytical) vs. brighter colors and collage (Synthetic). The primary purpose was to explore new ways of representing reality by depicting objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, analyzing their structure and form rather than their surface appearance.

- Key Artists: Pablo Picasso (Les Demoiselles d'Avignon), Georges Braque (Violin and Candlestick), Juan Gris (Still Life with a Bottle of Bordeaux), Fernand Léger (Nudes in the Forest).

Orphism (c. 1912-1914)

A style that emerged from Cubism, primarily associated with Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay. Orphism (also known as Orphic Cubism) moved towards pure abstraction, focusing on vibrant colors and geometric forms to evoke sensations and musicality, rather than analyzing objects. It was a bridge between Cubism's fragmentation and pure abstract art. Think of swirling, colorful discs and planes. It feels like Cubism decided to have a party and invite all the colors. Orphism built on Cubism's geometric forms but prioritized color and abstraction, aiming for a more lyrical and sensory experience.

- Characteristics: Pure abstraction, vibrant colors, geometric forms (often circles and discs), focus on light and color relationships, sense of rhythm and movement. The primary purpose was to create a pure, abstract art form based on color and form, evoking sensations and musicality.

- Key Artists: Robert Delaunay (Simultaneous Contrasts), Sonia Delaunay (Prismes Électriques).

Futurism (c. 1909-1914)

Inspired by the dynamism of Cubism but with a very different agenda, Futurism roared out of Italy. An Italian movement celebrating dynamism, speed, technology, machines, and violence. They loved the modern world, maybe a bit too much. Their art tried to capture the energy and motion of modern life, sometimes looking like a blur of movement, like in Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (sculpture) or Balla's Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (painting). They even wrote manifestos about it! The complex relationship between art and technology/progress is a theme that continues to this day. It's worth noting that Futurism later had a problematic association with fascism, adding a layer of complexity to its legacy. Boccioni's sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space embodies the Futurist ideal of capturing movement and speed, depicting a striding figure that seems to melt into the air around it. Futurism embraced the dynamism of the modern industrial age, seeking to represent speed, technology, and motion in art.

- Characteristics: Rhythmic patterns, depiction of movement and energy (lines of force), focus on modern urban life, machines, speed, simultaneity of vision. The primary purpose was to celebrate modernity, technology, speed, and dynamism, rejecting the past and advocating for a new art that reflected the energy of the industrial age.

- Key Artists: Giacomo Balla (Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash), Umberto Boccioni (Unique Forms of Continuity in Space), Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo.

Suprematism (c. 1913 - 1920s)

Across Europe, abstraction was taking hold in various forms. One of the earliest and most radical developments in abstract art, originating in Russia with Kazimir Malevich. It focused on basic geometric forms (squares, circles, lines) and a limited range of colors, aiming for the "supremacy of pure artistic feeling" rather than depicting objects. Think Malevich's iconic Black Square – about as pure as abstraction gets. It feels stark, philosophical, almost spiritual in its reduction. There's a philosophical challenge or meditative quality in pure geometric abstraction that can be surprisingly compelling. Suprematism, alongside Constructivism, was deeply connected to the Russian Revolution and the utopian/revolutionary ideals of the time, seeking a new art for a new society. Malevich's Black Square is a foundational work, presenting a simple black square on a white background as a radical break from representation, intended to evoke pure feeling. Suprematism sought a pure, non-objective art based on fundamental geometric forms, aiming to convey spiritual feeling.

- Characteristics: Pure geometric abstraction, limited color palettes (often black, white, red), focus on fundamental shapes, non-objective (no reference to the real world), emphasis on spiritual purity. The primary purpose was to achieve a pure, non-objective art that transcended the material world and conveyed spiritual feeling through the simplest geometric forms and colors.

- Key Artists: Kazimir Malevich (Black Square), El Lissitzky (also Constructivist - Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge).

Constructivism (c. 1913 - 1930s)

Originating in Russia alongside Suprematism, Constructivism also embraced geometric abstraction but rejected the idea of autonomous art ("art for art's sake"). Instead, it favored art as a practice for social purposes and functional design. Art with a job to do, often influencing architecture, graphic design (like Rodchenko's posters), and theatre (like Tatlin's Monument to the Third International project). They believed art should serve the revolution and the new society. The idea of art serving a social purpose is a powerful one that resonates through many later movements. Constructivism, alongside Suprematism, was deeply connected to the Russian Revolution and the utopian/revolutionary ideals of the time, seeking a new art for a new society. Tatlin's Monument to the Third International was a never-built architectural proposal, envisioned as a massive, spiraling tower of iron, glass, and steel, symbolizing the dynamism of the revolution and intended to house government functions. Constructivism applied abstract forms to practical purposes, aiming to integrate art into the service of society and the revolution.

- Characteristics: Geometric abstraction, industrial materials (metal, glass, plastic), emphasis on construction and utility, rejection of traditional easel painting, influence on graphic design and architecture, focus on social function. The primary purpose was to create art that served a social function, contributing to the development of the new socialist society through design, architecture, and propaganda, rejecting the idea of art as a purely aesthetic pursuit.

- Key Artists: Vladimir Tatlin (Monument to the Third International), Alexander Rodchenko (posters, photography), El Lissitzky, Alexandra Exter, Naum Gabo.

Bauhaus (1919-1933)

Though not strictly a style, the Bauhaus was a hugely influential German school of art, design, and architecture that operated from 1919 to 1933. Founded by Walter Gropius, it aimed to unify art, craft, and technology, advocating for functional design and mass production while maintaining artistic quality. Drawing on ideas from Constructivism and De Stijl, Bauhaus artists and designers explored geometric forms, primary colors, and industrial materials, applying these principles to everything from buildings and furniture to typography and textiles. Its impact on modern design and art education worldwide is immeasurable. The Bauhaus believed in the power of design to shape society and improve everyday life. Learn more about the Bauhaus artists and their influence and discover some underappreciated artists from the Bauhaus movement.

- Characteristics: Integration of art, craft, and technology; emphasis on functionality and mass production; geometric forms, primary colors, and industrial materials; interdisciplinary approach. The primary purpose was to rethink art education and design for the industrial age, creating functional and aesthetically pleasing objects and architecture for a modern society.

- Key Figures: Walter Gropius (founder), Johannes Itten, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (last director).

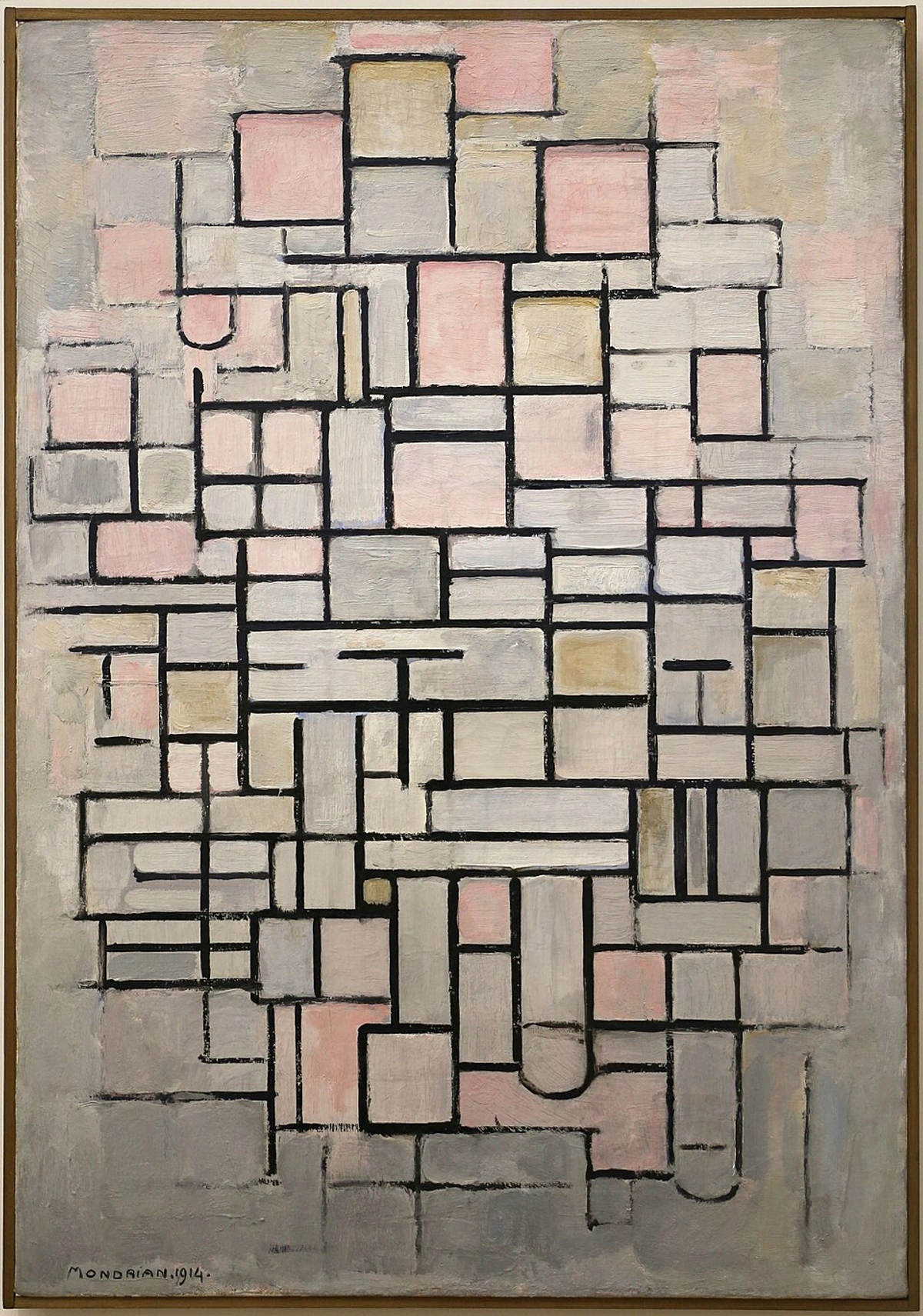

De Stijl (The Style) (1917 - 1931)

Across the border in the Netherlands, another form of geometric abstraction was developing. A Dutch movement (also known as Neoplasticism) advocating pure abstraction and universality by reducing art to its essential forms and colors. Think strict horizontal and vertical lines and only primary colors plus black and white. Mondrian is the star here, with iconic works like Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow. It aimed for harmony and order, a kind of visual utopia. Feels incredibly clean and structured, almost like a mathematical equation made beautiful. The pursuit of universal harmony through strict rules is a fascinating artistic goal. Theo van Doesburg, another key figure, later introduced diagonal lines, leading to a split in the movement. Mondrian's Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow is the quintessential example, using only black lines, white, and the three primary colors in a balanced, asymmetrical arrangement. De Stijl sought universal harmony and order through pure geometric abstraction and primary colors.

- Characteristics: Use of straight horizontal and vertical lines; restriction to primary colors (red, yellow, blue) and non-colors (white, black, gray); abstract, geometric forms; pursuit of universal harmony and order. The primary purpose was to create a universal visual language based on pure abstraction and geometric harmony, reflecting a desire for order and spiritual clarity in the wake of World War I.

- Key Artists: Piet Mondrian (Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow), Theo van Doesburg, Gerrit Rietveld (architecture/design - Schröder House).

Dada (c. 1916 - 1924)

Born out of the chaos and despair of World War I, Dada was less a style and more an anti-style. An avant-garde movement born out of negative reaction to the horrors of World War I, primarily centered in Zurich, Berlin, Paris, and New York. Dada rejected logic, reason, and aesthetics, embracing nonsense, irrationality, and intuition. It was anti-art, questioning the very definition of art. Feels like the art world's rebellious teenager, tearing up the rulebook – sometimes you get it, sometimes you just nod along. Dada was a radical reaction to the perceived rationality that led to the war, making their embrace of irrationality and absurdity a form of protest. Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917), a urinal presented as art, remains one of its most provocative and defining statements. Talk about challenging expectations! Key figures like Hannah Höch used photomontage (creating a new image by cutting and pasting together fragments of photographs) to critique society, while Kurt Schwitters created intricate collages (Merz art) from found materials. The importance of challenging conventions, even through nonsense and absurdity, feels particularly relevant in chaotic times. Dada was a radical reaction to the absurdity of war and the perceived failure of reason, rejecting traditional art values and embracing chaos and irrationality.

![]()

- Characteristics: Use of readymades (found objects presented as art - e.g., Duchamp's Fountain), collage, photomontage, chance operations, absurdist performances and publications, critique of society and convention, anti-rationality. The primary purpose was to protest against the war and the bourgeois society that was seen as causing it, by creating anti-art that challenged logic, reason, and traditional aesthetics.

- Key Artists: Marcel Duchamp, Jean Arp, Man Ray, Hannah Höch (Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany), Kurt Schwitters (Merz collages), Tristan Tzara (writer).

Surrealism (1920s-1940s)

Growing directly out of Dada's embrace of the irrational, Surrealism delved deeper into the mind. Originating in Paris, Surrealism sought to unlock the power of the imagination by exploring the subconscious mind and dreams. Influenced by psychoanalysis (Freud) and spearheaded initially by writer André Breton, it aimed to resolve the contradictory conditions of dream and reality. If you find hidden meanings intriguing, learn How to Understand Symbolism: A Practical Guide to Interpretation. Think melting clocks (Dalí's The Persistence of Memory) and impossible landscapes – it's where logic goes on vacation. Does your own dream life ever resemble a Surrealist painting? Exploring the subconscious unlocks endless possibilities for art. There are two main streams: Automatism (spontaneous creation, like Joan Miró's playful forms or using techniques like frottage - rubbing textures - or decalcomania - pressing paint between surfaces - as developed by Max Ernst) and Veristic Surrealism (highly detailed, dreamlike scenes, like Salvador Dalí's meticulous nightmares or René Magritte's unsettling juxtapositions). They also used collaborative games like Exquisite Corpse to tap into collective subconscious creativity. Dalí's The Persistence of Memory is iconic, depicting melting clocks draped over objects in a desolate landscape, creating a vivid, unsettling dream image rendered with meticulous detail. Surrealism built on Dada's irrationality but focused on exploring the subconscious mind as a source of creativity.

- Characteristics: Dreamlike and bizarre scenes, illogical juxtapositions, automatism (drawing/painting spontaneously using techniques like frottage, decalcomania) vs. veristic (detailed, realistic rendering of dream imagery), exploration of desire, mystery, and the uncanny, influence of psychoanalysis. The primary purpose was to liberate the imagination and explore the subconscious mind, creating art that went beyond conscious control and rational thought, often with political or psychological undertones.

- Key Figures: Salvador Dalí (The Persistence of Memory), René Magritte (The Treachery of Images), Max Ernst (Europe After the Rain II), Joan Miró (The Farm), André Breton (writer/theorist), Yves Tanguy (Mama, Papa is Wounded!), Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo.

Art Deco (1920s-1930s)

While Surrealism explored the inner world, Art Deco celebrated the modern, glamorous outer world. A style of visual arts, architecture, and design that first appeared in France just before World War I. It influenced the design of buildings (like the iconic Chrysler Building in New York), furniture, jewelry, fashion, cars, etc., combining modern styles with fine craftsmanship and rich materials. Think Great Gatsby glamour. It drew influences from Cubism, Futurism, and even ancient Egyptian and Aztec art, resulting in a sleek, geometric, and often luxurious aesthetic. The elegance and optimism the style evokes still feels glamorous today. Tamara de Lempicka's paintings, like Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti), perfectly capture the Art Deco spirit with their sleek lines, bold colors, and glamorous subjects. Art Deco built on Art Nouveau's decorative impulse but adopted a more geometric, streamlined aesthetic inspired by modern technology and diverse cultural sources.

- Characteristics: Rich ornamentation, geometric and stylized forms, symmetry, bold colors, luxurious materials (lacquer, exotic woods, chrome), influences from Cubism, Futurism, and ancient Egyptian and Aztec art. The primary purpose was to create a modern, elegant, and luxurious style for architecture, interiors, and decorative objects, reflecting the optimism and glamour of the interwar period.

- Key Designers/Artists: Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (furniture), René Lalique (glass), Erté (fashion), Tamara de Lempicka (painting - Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti)).

Regionalism (c. 1930s)

During the Great Depression in the US, some artists turned inward, focusing on American life. An American realist modern art movement that depicted scenes of rural and small-town America, primarily in the Midwest. It arose during the Great Depression, often celebrating (or sometimes satirizing) heartland values and landscapes as a form of American identity. Think Grant Wood's famous American Gothic – instantly recognizable, right? It felt like a turning inward, focusing on distinctly American subjects. The power of art to capture a specific time and place, a cultural identity, is one of its great strengths. Many Regionalist artists benefited from commissions through the WPA Federal Art Project, a New Deal program designed to employ artists during the Depression, often creating murals for public buildings that celebrated American life and history. Grant Wood's American Gothic is the quintessential image, depicting a farmer and his daughter in front of a farmhouse, capturing a sense of stoic American resilience. Regionalism offered a distinctly American response to the challenges of the Depression, focusing on familiar rural scenes.

- Characteristics: Realistic depiction of rural life, landscapes, and people of the American Midwest and South; often conveys a sense of nostalgia or nationalism; rejection of European abstraction. The primary purpose was to create a distinctly American art that celebrated the values and landscapes of the heartland, often supported by government programs during the Great Depression.

- Key Artists: Grant Wood (American Gothic), Thomas Hart Benton (America Today mural series), John Steuart Curry (Baptism in Kansas).

Social Realism (c. 1930s-1940s)

Overlapping with Regionalism but often more politically charged, Social Realism, originating in the US and other countries, focused on the lives, hardships, and struggles of the working class and poor, frequently carrying a message of social or political critique. It aimed to expose injustice and advocate for change, using realistic depiction as a tool for commentary. Think murals depicting labor struggles (like those by Diego Rivera) or paintings highlighting poverty – art with a definite point to make. The role of art in social commentary and activism is a vital one, giving voice to important issues. Like Regionalism, Social Realism also found support through the WPA Federal Art Project. It was also significantly influenced by the powerful Mexican Muralism movement (Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros), which used large-scale public art to tell the story of Mexico's history and revolution, often with strong social and political themes, emphasizing public access and political messaging. Social Realism used realistic depiction as a tool for social and political commentary, highlighting the struggles of ordinary people.

- Characteristics: Depiction of working-class life, social inequality, political struggle; realistic style; often conveys a critical or sympathetic message; influenced by Mexican muralists (like Diego Rivera). The primary purpose was to use art as a tool for social and political change, depicting the hardships of the working class and advocating for social justice.

- Key Artists: Ben Shahn (The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti), Dorothea Lange (photography - Migrant Mother), Philip Evergood, Diego Rivera (Mexican muralist, influential - Man at the Crossroads).

Forces Shaping Art Styles

Art styles don't just appear out of nowhere; they are shaped by a complex interplay of factors. Beyond the direct influence of one style on another, broader forces in society, technology, and the art world itself play crucial roles.

The Impact of Photography

We can't talk about stylistic evolution, especially from the mid-19th century onwards, without mentioning photography. Its invention threw a massive spanner in the works for painting. Suddenly, capturing reality accurately wasn't painting's unique selling point anymore. Some say this pushed painting towards exploring things photography couldn't do – emotion (Expressionism), subjective perception (Impressionism), underlying structure (Cubism), pure form and color (Abstraction). Others embraced photography, using it as a reference or incorporating photographic aesthetics (Photorealism). It was – and still is – a complex relationship, a constant dialogue between capturing the world and interpreting it. You could say photography freed painting to be more... well, painterly. The rise of photography also led to the development of photography as an art form in itself, with its own styles and movements (like Pictorialism, which aimed to make photos look like paintings, or Straight Photography, which embraced the medium's sharp focus and detail), often exhibited in dedicated spaces like The Photographers' Gallery.

The Role of Art Criticism

Another engine of change and definition is Art Criticism. Critics don't just review shows; they often frame movements, champion artists, and provide the theoretical language we use to understand styles. Think of Clement Greenberg promoting Abstract Expressionism and formalism, or Harold Rosenberg focusing on the 'action' in Action Painting. Their words shaped perception and influenced the market, sometimes controversially. While artists create the work, critics often help write the first draft of its history, for better or worse. It adds another layer to understanding how styles become recognized and valued. You can explore the evolving impact of Art Critics Today.

The Art Market's Influence

And let's not forget the art market. Galleries, collectors, auction houses – they all play a significant role in which styles and artists gain visibility and perceived importance, especially in the contemporary scene. Market trends can influence what artists create and what gets shown, adding another layer of complexity to the evolution of styles. It's a business, after all, and money talks, for better or worse. Understanding art prices and navigating the secondary art market are part of this reality.

Post-War to Contemporary: A Shifting Landscape

Abstract Expressionism (1940s-1950s)