Pointillism: Ultimate Guide to the Art Movement, Technique & Legacy

Dive into Pointillism: Seurat's dots, Signac's evolution, scientific color theory (Divisionism), key artists (Van Rysselberghe, Luce), anarchist ties, Italian Divisionism & lasting influence on Modern Art (Fauvism, abstraction, mosaics). Explore the meticulous technique, variations in mark-making, conservation challenges & surprising legacy, including the role of new pigments and the labor involved.

Pointillism: The Ultimate Guide to the Art Movement & Technique

Step into a gallery featuring Pointillism, and you might initially see a shimmering haze of dots. It's like looking at a screen too close, all pixels and no picture. Step back, however, and those dots coalesce into luminous landscapes, vibrant portraits, and scenes bursting with light. Ah, there it is! Pointillism is more than just painting with dots; it was a revolutionary, scientifically-driven approach to color and perception that marked a pivotal moment in the development of Modern Art. It's a technique that demands you engage with it, literally asking you to step back and let your brain do some of the work. I find that fascinating – art that requires your active participation, even if it's just adjusting your viewing distance. It makes you wonder about the artist's intention, forcing you to see the world not just as a whole, but as a collection of tiny, deliberate choices. As someone who often gets lost in the minutiae of things, whether it's the tiny details in a painting or the endless possibilities in a blank canvas, I can appreciate the mindset required here. It takes a certain kind of patience, a willingness to build something grand from countless small acts. It's a challenge I relate to, even if my own attempts at meticulous detail sometimes devolve into impatient scribbles. It's a different level of commitment than I often manage, if I'm being honest. My own creative process tends to be a bit more... chaotic. You can see some of the results of my less-than-Pointillist approach in my art for sale.

This ultimate guide explores the fascinating world of Pointillism, delving into its origins as part of Neo-Impressionism, the scientific color theories that underpin it (Divisionism), the meticulous technique itself (and its surprising variations in mark application), its key artists like Georges Seurat (and his incredible drawings and color studies) and Paul Signac, iconic masterpieces, its reception (including specific criticisms and support), typical subjects, its connection to anarchist political leanings for some artists, the sheer labor involved, and its enduring legacy, including its influence on later movements and even modern technology. It's a journey from tiny dots to big ideas, and maybe a little peek into the minds of artists who had the patience of saints. Seriously, the sheer dedication required makes my own attempts at detailed work feel like scribbles. It's a different level of commitment.

What is Pointillism?

Pointillism is a painting technique developed in the mid-1880s, characterized by the application of small, distinct dots or marks of pure color directly onto the canvas. The core idea is that these dots, when viewed from a distance, optically mix in the viewer's eye to create the perception of blended colors and forms. Instead of mixing colors on a palette, Pointillist artists relied on the viewer's brain to do the blending work, believing this method would achieve greater luminosity and vibrancy than traditional techniques. It’s a fascinating answer to the question: what technique uses dots of color to create a specific optical effect? Pointillism is that technique. It's like they were trying to hack your visual system, which, honestly, is kind of cool. Think about your computer screen or phone display – those images are made up of tiny red, green, and blue pixels that blend together in your eye from a normal viewing distance. Pointillism is essentially the manual, analog version of that digital process, reinforcing the idea that they were deliberately manipulating visual perception. It turns the viewer into an active participant, completing the artwork in their own mind. It's a collaboration across time and space, between the artist's hand and your eye.

Historical Context: A Scientific Step Beyond Impressionism

Pointillism emerged in France during the 1880s as part of the broader Post-Impressionist movement. While deeply indebted to Impressionism's focus on capturing light and contemporary life, Pointillism represented a deliberate shift:

- Building on Impressionism: Artists like Seurat admired the Impressionists' vibrant palettes and depiction of light but sought a more structured, less spontaneous method. They saw the light, but wanted to bottle it, analyze it, and put it back together with scientific precision. You can learn more about the movement it built upon in the Ultimate Guide to Impressionism. It was less about capturing a fleeting moment and more about constructing a timeless, luminous reality. This tension between Impressionism's spontaneous capture of a moment and Pointillism's structured construction of reality feels like a fundamental artistic choice – do you chase the ephemeral or build the eternal? I think both approaches are valid, but the Pointillists definitely chose the path of deliberate construction.

- Seeking Structure and Science: Pointillism was a reaction against what some perceived as the formlessness or fleeting nature of Impressionism. Its pioneers aimed to ground painting in scientific principles of optics and color theory (Divisionism), creating a more calculated and enduring art form. It was a move from 'feeling the light' to 'calculating the light'. This desire for order and scientific grounding was a hallmark of the movement, reflecting a broader late 19th-century cultural context that celebrated science, progress, and rational systems. It was an era fascinated by understanding the world through empirical observation and systematic analysis, and the Pointillists brought that same spirit into the studio.

- Neo-Impressionism: Pointillism became the defining technique of Neo-Impressionism, the term coined by art critic Félix Fénéon in 1886 to describe the art of Seurat, Signac, and their followers who embraced these scientific theories. So, Pointillism is the how (the dots/marks), Neo-Impressionism is the who and when (the movement), and Divisionism is the why (the color theory). It was a relatively small but tightly-knit group, bound by shared artistic and often political ideals.

The Science of Color: Theories Behind the Dots

The development of Pointillism was heavily influenced by 19th-century scientific research into color and optics. This wasn't just artists messing around; they were reading scientific texts and trying to apply them rigorously. It's the kind of cross-disciplinary thinking I find really exciting – when art meets science in a tangible way. Artists, often seen as intuitive and emotional, deliberately applying scientific principles feels almost counter-intuitive from a modern perspective, but it's also incredibly exciting. It shows a different kind of creativity, one that finds inspiration in data and theory.

- Optical Mixing (Divisionism): The fundamental principle of Divisionism. Pointillists believed that placing small dots of pure color side-by-side would result in a more vibrant and luminous blend in the viewer's eye than mixing those same colors physically on the palette (pigment mixing). For example, blue and yellow dots placed together would optically mix to create a more vibrant green than pre-mixed green paint. It's like your brain is the final blender. This was the core hypothesis they were testing on canvas.

- Color Theory Influences:

- Michel Eugène Chevreul: A chemist whose work on "simultaneous contrast" demonstrated how adjacent colors influence each other's perception (e.g., placing complementary colors like red and green next to each other makes both appear more intense). This was huge – it meant the context of a color mattered just as much as the color itself. Chevreul's work provided a scientific basis for the Pointillists' careful juxtaposition of colors. He showed them why putting certain colors next to each other made them pop.

- Ogden Rood: An American physicist whose book Modern Chromatics analyzed light and color relationships, influencing the Neo-Impressionists' systematic approach. Rood gave them the rulebook, detailing how colors behave when light interacts with them. His analysis of additive and subtractive color was particularly influential.

- Charles Blanc: His Grammaire des arts du dessin also contributed ideas about color harmony and application. Blanc added the grammar to the visual language, providing a theoretical framework for composing with color.

These theories provided a framework for artists to approach color application methodically, aiming for scientifically accurate representations of light and hue. It wasn't just slapping paint on; it was a calculated experiment on canvas. They were trying to create a visual system as precise as a scientific diagram, but with the emotional impact of art. A tall order, but fascinating to witness. The ambition of trying to replicate the luminosity of light with opaque paint feels like a fascinating, almost alchemical pursuit – turning dull earth pigments into shimmering light through sheer will and scientific application. You can dive deeper into how artists use color in general with this guide: How Artists Use Color: An Artist's Guide to Theory, Emotion & Light.

Deeper Dive: Why Optical Mixing Felt Brighter

So, why all the fuss about dots? Why didn't Seurat just mix a nice green on his palette like everyone else? It boils down to the difference between additive and subtractive color mixing. This is where it gets a little science-y, but stick with me. It's actually quite intuitive once you think about it.

Think about light: If you shine a red light, a green light, and a blue light on the same spot, what do you get? White light. That’s additive mixing – combining light makes things brighter. Your computer screen works this way; tiny red, green, and blue lights (pixels) combine to create all the colors you see. More light equals more brightness. It's about adding energy.

Now think about paint: If you mix red, green, and blue paint together, you don't get white. You get a muddy, dark mess, probably closer to black. That’s subtractive mixing. Each pigment absorbs (subtracts) certain wavelengths of light and reflects others. When you mix pigments, you increase the amount of light being absorbed, resulting in a darker, less vibrant color. Less light equals less brightness. It's about removing energy.

The Pointillists, inspired by guys like Rood, figured (or perhaps, more accurately, hoped and theorized) that placing pure color dots side-by-side would trick the eye and brain into performing a kind of additive mixing. Instead of the pigments physically mixing and dulling each other on the palette (subtractive), the pure colors would hit your retina separately, and your brain would add their light sensations together, much like how your brain interprets the light from pixels on a screen. They aimed for the luminosity of light, not just the color of paint. Did it perfectly replicate additive light mixing? Probably not, physics is complicated, and paint still involves subtraction. But did it create a perceptibly more vibrant and shimmering effect than traditional blending? To many eyes, absolutely. It was a clever attempt to hack perception, using the viewer's own brain as part of the medium – a bit like trying to convince yourself that staring at a screen is the same as being outside in the sun. Maybe not quite, but an interesting experiment nonetheless. It makes you appreciate the thought process behind every single dot. They weren't just painting; they were conducting an optical experiment on a grand scale.

The Pointillist Technique: Dots in Practice

So, how did they actually put these scientific theories into practice? Executing a Pointillist painting required immense patience and precision. I can barely finish a sketch sometimes, so the sheer dedication here blows my mind. It wasn't a technique for the faint of heart, or the easily distracted. I imagine the internal monologue went something like, "Just... one... more... dot..." It certainly wasn't a technique for those seeking instant gratification.

- Application of Marks: Artists applied paint in tiny, distinct dots or short, comma-like brushstrokes using the tip of the brush. Consistency in mark size and placement was often crucial, especially for Seurat's early, more rigid works. However, as we'll see, there were variations in mark application among artists. It wasn't a one-size-fits-all approach, even within the core group. It's like they had the same rulebook but interpreted the font size differently. This variation shows the technique wasn't a purely mechanical process; individual artistic temperament still played a role.

- Pure Color: Ideally, colors were applied directly from the tube or with minimal mixing, preserving their individual intensity. No muddying the waters (or the paint). This was key to achieving the desired optical mixing effect.

- Juxtaposition: Colors were carefully placed next to each other based on color theory. Complementary colors were used to enhance vibrancy, while analogous colors could create smoother transitions. Dots of white might be interspersed to increase luminosity. It was like painting by numbers, but the numbers were complex color equations derived from scientific texts. Every dot had a purpose in the overall chromatic scheme.

- Structured Composition: Underlying drawings and compositional grids were often used to organize the placement of dots, leading to highly ordered and balanced designs. Seurat, in particular, was known for his almost mathematical approach to composition, sometimes employing principles like the golden ratio. He meticulously arranged figures in static, frieze-like formations, particularly evident in the almost processional arrangement of figures in La Grande Jatte, contributing to the sense of timeless order. He also utilized strong orthogonal lines (lines perpendicular to the picture plane) to create depth and structure, as seen in the receding perspective lines implied in works like Bathers at Asnières. It's structure on top of structure! It makes my brain hurt a little, but the result is undeniably impactful. This rigid structure contrasted sharply with the more spontaneous compositions of Impressionism. Understanding Art Composition: A Viewer's Guide to Seeing More Than Just Paint can help you spot these underlying structures.

- Preparatory Studies: Beyond the compositional drawings, artists like Seurat also created preparatory color studies or small painted sketches. These weren't just quick ideas; they were used to plan the complex chromatic relationships and test how different color juxtapositions would interact optically before committing to the large canvas. It was like doing small-scale color experiments before the main event, ensuring the final, painstaking application of dots would achieve the desired luminous effect.

- Building Form: Form and volume were suggested not through blended shading, but through the density and arrangement of different colored dots. Understanding the basic elements of art like color and form is key here. It's like sculpting with color dots, building up shapes and volumes purely through the interaction of hues and values created by the dots.

- Viewing Distance: The final effect is entirely dependent on the viewer standing at an appropriate distance, allowing the individual dots to visually merge. This is the part where you become part of the art-making process. The artist sets the stage, but the viewer completes the illusion. It's a unique dialogue between creator and observer.

Variations in Mark Application

While the term "Pointillism" suggests only dots, the artists actually employed a range of marks, and this evolved over time and varied between individuals. Looking closely at their work reveals these subtle but significant differences:

- Georges Seurat: The pioneer, known for his initial, most rigorous approach. His marks were typically small, relatively uniform dots or tiny, short brushstrokes. The goal was a precise, almost mechanical application to ensure the optical mixing occurred as theoretically predicted. The visual effect is often a fine, shimmering texture that resolves into clear forms from a distance.

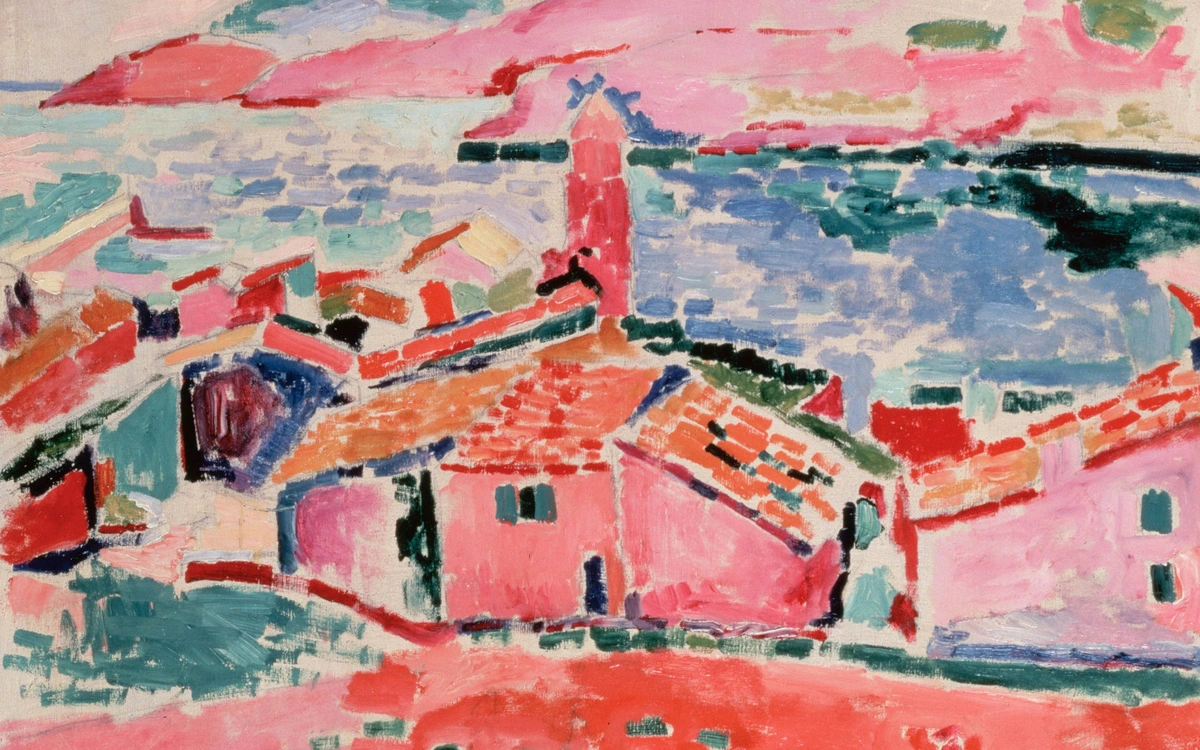

- Paul Signac: Initially followed Seurat's lead with small dots. However, especially after Seurat's death, Signac's marks became noticeably larger and more distinct. He moved towards more square or rectangular 'tesserae' (like small tiles in a mosaic). This allowed for a bolder application of color and perhaps a slightly less rigid feel, while still relying on optical mixing (Divisionism). The visual effect is often more vibrant and textured up close, with the optical blend happening over a slightly larger area. You can see this in works like The Port of Saint-Tropez (1901-02), where the individual blocks of color are quite visible up close but blend into radiant light from a distance.

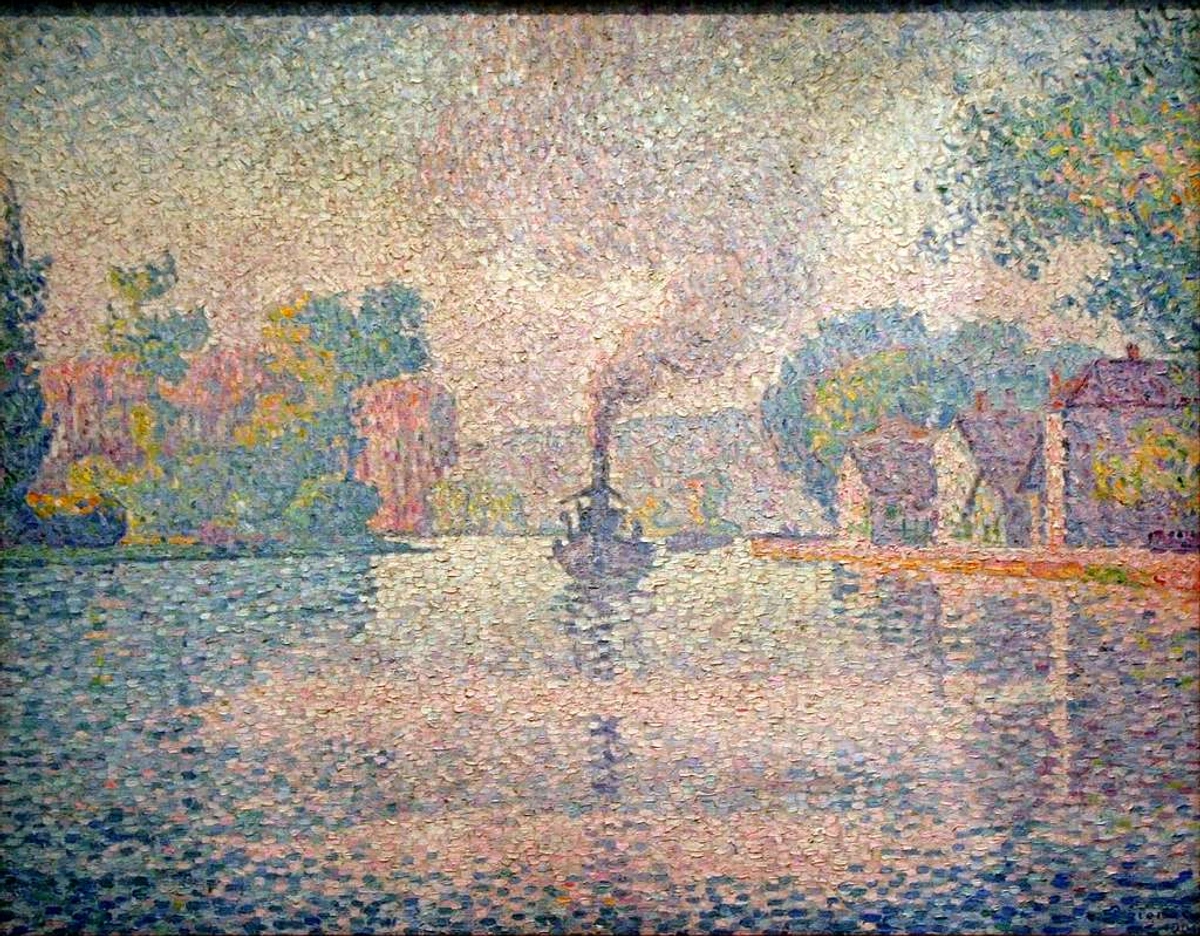

An example of Signac's earlier, more dot-focused style: L'Hirondelle Steamer on the Seine (1901)

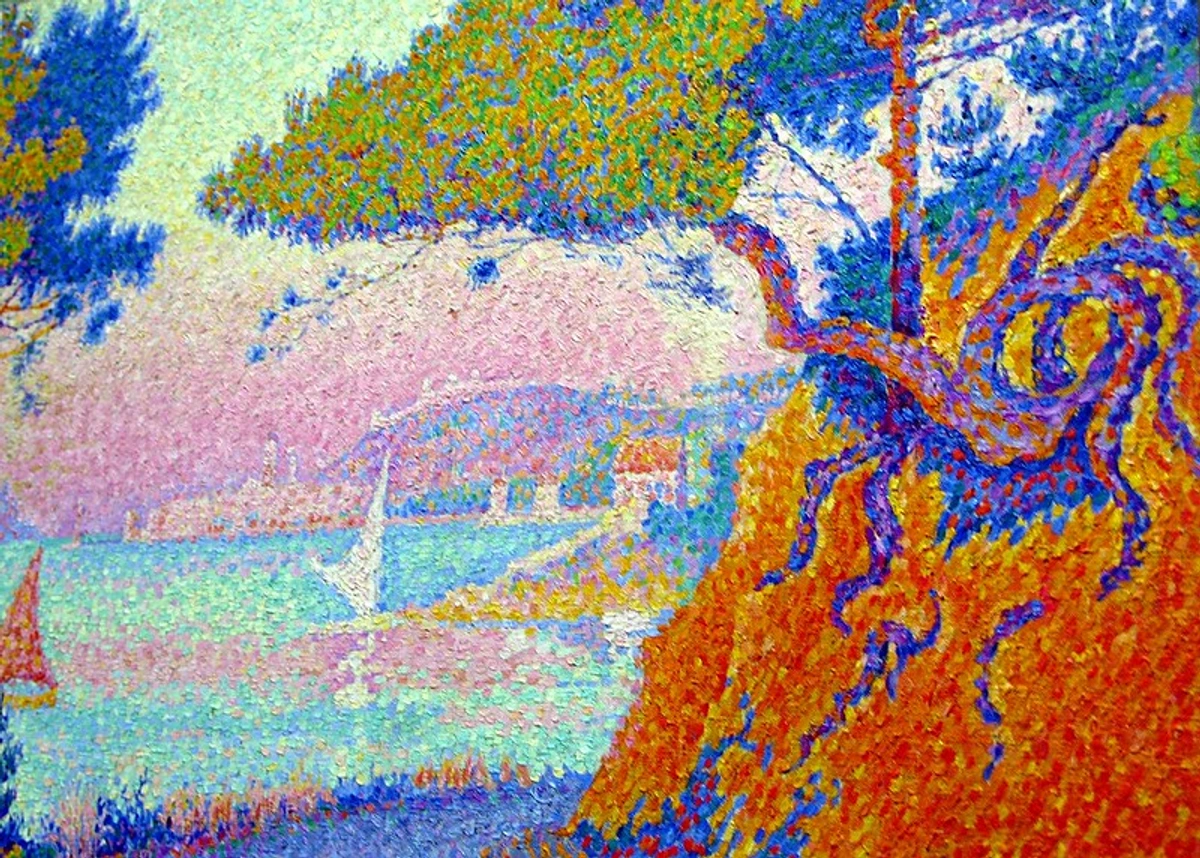

Signac's Golfe-Juan showing a move towards slightly larger marks

- Henri-Edmond Cross: A close associate of Signac, Cross also adopted larger, more distinct marks, often described as block-like or rectangular. His application could be looser than Seurat's, contributing to a more decorative and less austere feel in his radiant Mediterranean landscapes. The visual effect is a rich, mosaic-like surface where the individual color blocks vibrate against each other, as seen in works like Two Women by the Shore, Mediterranean (c. 1906-07). His later 'tesserae' are quite distinct from Seurat's finer dots, creating a different kind of shimmering texture. He brought warmth to the dots, a more sensual approach to the scientific principles.

Henri-Edmond Cross, Les Pins (c. 1897-99)

![]()

Henri-Edmond Cross, Two Women by the Shore, Mediterranean (c. 1906-07), showing his later, more block-like style.

- Maximilien Luce: While also using dots, Luce's application could be particularly dense and tightly packed, especially in his depictions of urban and industrial scenes. This created a powerful, almost gritty texture that suited his subject matter, capturing the intense, sometimes harsh, light of the modern city. The visual effect is often one of intense energy and solidity, with the close-packed marks building form and atmosphere, evident in paintings like The Steelworks (1895). He really showed the versatility of the technique beyond sunny landscapes, applying it to the harsh realities of the industrial age. Dots in the city, reflecting a different kind of light.

While known for industrial scenes, Luce also painted still lifes like this one.

These variations show that even within the seemingly strict framework of Divisionism, artists found room for individual expression and adapted the technique to their own artistic goals and temperaments. It wasn't just about the science; it was about the art they wanted to make with it.

Try Pointillism Yourself (If You Dare)

Feeling inspired by all these dots? Or maybe just morbidly curious about how tedious it really was? While tackling a full-blown Pointillist masterpiece might require more patience than most of us possess (I know I'd probably give up after one square inch and decide abstract expressionism is more my speed), you can definitely play with the basic principles. It's a good way to get a feel for the dedication involved and to see the color theories in action. It's a surprisingly meditative process, if you can quiet your inner voice screaming about how many dots are left. Prepare for hand cramps. Your inner perfectionist will either thrive or weep.

- Grab Some Color: You don't need fancy oils. Markers, colored pencils, crayons, or even basic acrylic or gouache paints will work fine for experimenting. The key is having distinct, relatively pure colors. Think primary and secondary colors to start. The purer the color, the better the optical mixing effect.

- Keep it Simple: Start with a simple subject – an apple, a basic landscape shape, maybe just abstract color fields. Don't try to recreate La Grande Jatte on your first go. Seriously. Your hand will thank you. Start small, understand the process, then maybe scale up if you're feeling brave (or masochistic). It's a good reminder that even the simplest artistic ideas can require immense effort in execution, a lesson I'm constantly relearning on my own artist's timeline.

- Think in Marks: Instead of blending, consciously place small marks of color next to each other. Want green? Place blue dots and yellow dots close together. Want orange? Try red and yellow dots. Want a darker area? Use denser dots or darker colors side-by-side. Lighter area? Fewer dots, more white space, or intersperse white/light yellow dots. It's like building an image pixel by pixel, just like a digital screen. Try experimenting with different types of marks – not just perfect dots, but maybe small dashes, squares, or even tiny cross-hatches – and see how the optical effect changes, linking back to the variations in mark application we discussed earlier. This is where you can channel your inner Signac or Cross!

- Play with Complements: Try putting marks of complementary colors (red/green, blue/orange, yellow/violet) next to each other to see if they vibrate or pop. This is where Chevreul's ideas come alive on your page. It's a simple way to see simultaneous contrast in action.

- Step Back! This is crucial. The magic (or attempted magic) happens from a distance. Keep stepping back to see how your marks are mixing optically. What looks like a mess up close might resolve into something interesting from afar. It's the payoff for all that dotting, the moment the illusion takes hold.

- Don't Stress Perfection: Remember, Seurat spent years. You're just dipping a toe. Have fun with it! See it as an exercise in understanding color relationships and patience. And maybe a good way to practice mindfulness, one dot at a time. Finding art inspirations often comes from trying things out, even the seemingly crazy, laborious ones. Or maybe you'll just gain a newfound appreciation for the painters who had the stamina to stick with it! It certainly makes me appreciate the ease of digital art sometimes. It's a good reminder of the physical effort behind historical art. If you do try it, I'd love to hear about your experience or even see your dotted creations! Share your attempts and reflections – it's part of the artistic journey.

Key Characteristics of Pointillist Paintings

So, what makes a Pointillist painting look like a Pointillist painting? When you see one, you'll know it (especially up close). They have a unique presence that sets them apart. After understanding the technique, these characteristics become much clearer.

- Enhanced Luminosity: They often seem to glow or shimmer due to the optical mixing effect (Divisionism). It's like they're lit from within, capturing the vibrancy of light itself rather than just the color of objects.

- Vibrant Color: Colors appear intense and saturated because they aren't physically dulled by mixing. Pure color, pure impact. The juxtaposition of pure hues creates a visual intensity that traditional blending couldn't match.

- Structured & Ordered: Compositions feel deliberate, stable, and often meticulously planned. As mentioned, artists like Seurat often employed specific compositional strategies, like the golden ratio or the explicit use of frieze-like arrangements (look at the stiff, parallel figures in La Grande Jatte) and strong orthogonal lines to create a sense of calculated order and rational space, enhancing this calculated feeling. It's art that feels like it was built, not just painted. There's a sense of underlying geometry and control.

- Static Quality: The precise, time-consuming technique can lend the paintings a sense of stillness or frozen time, contrasting with the dynamic brushwork of many Impressionists. Time seems to pause in a Pointillist world, capturing a moment with almost scientific detachment.

- Textured Surface: Close up, the multitude of dots creates a unique, granular surface texture. It's a tactile experience, even if you can't touch it. This texture is part of the visual effect, contributing to the shimmering quality from a distance.

- Typical Size: While some Pointillist paintings, like Seurat's La Grande Jatte, were monumental in scale (around 7 by 10 feet), others were smaller. However, even smaller works required significant time and precision due to the meticulous application of individual marks.

Key Artists of Pointillism

Who were the master dot-makers? While several artists experimented with the technique, two figures are central, and a few others are definitely worth knowing. It wasn't a huge club, but it was an influential one, and each member brought their own nuances to the shared principles. Thinking about them reminds me that even revolutionary ideas need a community to take root, even if that community is small and prone to arguments (which, let's face it, art movements often are).

Georges Seurat (1859-1891)

Considered the founder and driving force behind Pointillism and Neo-Impressionism. Seurat was deeply interested in scientific theories and applied them with rigorous methodology. His work is characterized by meticulous planning, formal structure, and a unique blend of modern life subjects with almost classical austerity. He was the scientist-artist, the one who wrote the original code, the one who truly believed in the systematic application of theory.

![]()

- Seurat's Preparatory Studies: More Than Just Sketches: Before the dots, there was darkness and light, and also color planning. We often focus solely on Seurat's paintings, but his distinctive drawings in black Conté crayon on textured Michallet paper are masterpieces in their own right and absolutely crucial to understanding his process. He made hundreds of them, often as preparatory studies for his major paintings like Bathers and La Grande Jatte. Using the side of the crayon stick, he built up forms not through lines, but through subtle gradations of tone, allowing the rough texture of the paper to create a "scumbled" effect, almost like a monochromatic version of Pointillism. Figures emerge from deep shadow into soft light, creating an atmosphere of quiet mystery and monumentality. These drawings demonstrate his profound understanding of light and form before he even considered color. Crucially, he also created small painted color studies or sketches, meticulously planning the chromatic relationships and testing the optical effects of different color juxtapositions before tackling the large canvas. These studies weren't just quick ideas; they were where Seurat worked out his compositional and color ideas with incredible sensitivity before translating them into the complex system of colored dots. Honestly, sometimes I find the Conté drawings even more haunting and atmospheric than the paintings – they have this incredible stillness. Seeing these monochromatic and small color studies changes my perception of his colorful paintings; they reveal a deeper, more fundamental artistic concern with light, shadow, form, and color interaction beneath the color theory. They show the soul behind the system, the underlying artistic sensibility beneath the scientific method.

- Major Works:

- Bathers at Asnières (1884): An early precursor, showing his interest in structure and modern leisure, though not fully Pointillist. Many Conté drawings and color studies exist for this work. You can see the ideas starting to form, the move towards depicting contemporary life with a sense of permanence.

- A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-1886): His masterpiece and the iconic Pointillist painting. A large-scale depiction of Parisian leisure, meticulously composed with countless dots. Its debut caused a sensation. Again, extensively prepared through drawings and color studies. This is the painting people think of when they hear Pointillism, a monumental achievement of patience and theory.

- The Circus (1891): One of his later works, exploring themes of entertainment and artificial light, left unfinished at his early death. A glimpse of where he might have gone, applying the technique to the dynamic, artificial world of the circus.

Paul Signac (1863-1935)

A close friend and collaborator of Seurat, Signac became the chief advocate and theorist of Neo-Impressionism after Seurat's death. He was passionate about sailing, and many of his works depict seascapes, harbors, and the effects of light on water. While initially adhering strictly to Seurat's dot technique (as seen in works like L'Hirondelle Steamer on the Seine (1901)), his later work often featured larger, mosaic-like squares or rectangles of color, moving away from the tiny dot and leaning more towards a broader interpretation of Divisionism. This shift is quite apparent when comparing his early works to later ones; the marks become bolder, the application perhaps a bit looser, though still based on optical mixing principles. This evolution allowed for perhaps greater expressive freedom while still relying on optical mixing. You can see this evolution clearly when comparing earlier pieces to later ones like The Papal Palace, Avignon (1900) or the radiant The Port of Saint-Tropez (1901-02), where the tesserae-like blocks of pure color build the vibrant Mediterranean light. It's like he kept the core idea but zoomed out a bit, maybe finding the pure dot just too painstaking after a while? I can relate. He was the movement's champion and adapter, ensuring its principles lived on and evolved.

Other Neo-Impressionists: More Than Just Seurat and Signac

While Seurat and Signac grab the headlines, it's easy to forget that Neo-Impressionism wasn't just a two-man show. Several other talented artists adopted the Divisionist approach, often bringing their own perspectives and subjects. Thinking about them reminds me that even revolutionary ideas need a community to take root, even if that community is small and prone to arguments (which, let's face it, art movements often are). Interestingly, several key figures, including Signac, Luce, and Pissarro (during his Neo-Impressionist phase), held strong anarchist political beliefs. This wasn't just a passing fad; they actively supported the cause. For example, Signac, Luce, Cross, and others frequently contributed illustrations to anarchist journals like Jean Grave’s Les Temps Nouveaux (The New Times) and La Révolte (The Revolt). Sometimes they donated artworks to raise funds for the cause or supported anarchist thinkers and activists. While not always overt in their art, this shared ideology perhaps fueled their desire for radical artistic change, their anti-establishment stance (seen in co-founding the Salon des Indépendants), and sometimes subtly informed their subject matter, particularly in Luce's focus on the working class. In La Grande Jatte, for instance, while not explicitly political, the depiction of different social classes enjoying shared leisure time on the island could be interpreted as a subtle reflection of utopian ideals or a vision of a harmonious society, aligning with some anarchist aspirations for a more equitable world. It adds another layer to their "scientific" approach – a desire for a rationally ordered society perhaps mirrored their rationally ordered canvases? Or maybe the desire for radical societal change paralleled their desire for radical artistic change? It's a surprising layer to the seemingly detached scientific approach. Food for thought. Art and politics, often intertwined, even in the seemingly detached world of scientific color theory.

- Camille Pissarro (1830-1903): The elder statesman of Impressionism had a surprising Neo-Impressionist phase from about 1885-1888. Encouraged by Seurat and Signac, he applied the dot technique to his characteristic rural scenes and landscapes. Good examples include Apple Harvest (1888) and the meticulous View from My Window, Éragny-sur-Epte (1886-88), where you can see him painstakingly applying the dots to capture the light on the fields and houses outside his window. You can feel his struggle – trying to reconcile his Impressionist sensibility with the rigid demands of Pointillism. He eventually abandoned it, finding it too slow and restrictive for capturing fleeting natural effects, but his brief foray lent significant credibility to the fledgling movement. Even the masters experimented, and his brief adoption showed the technique's potential, even if it wasn't for him.

- Henri-Edmond Cross (1856-1910): A key figure, especially after Seurat's death. Cross moved to the South of France and became known for his radiant Mediterranean landscapes like The Golden Isles (c. 1891-92) or Cypresses at Cagnes (1908). He was a close friend of Signac and his style evolved alongside Signac's, often using larger, more rectangular brushstrokes (closer to Divisionism than strict Pointillism) to create mosaic-like surfaces vibrating with color and light, as seen in Two Women by the Shore, Mediterranean (c. 1906-07). His work feels less austere than Seurat's, embracing a more decorative, almost idyllic quality.

- Maximilien Luce (1858-1941): Luce brought a different focus, often depicting urban and industrial scenes, as well as the lives of working-class people, using the Pointillist technique. His anarchist political leanings sometimes informed his subject matter, giving his work a social edge. His application of dots could be quite dense and tightly packed, creating powerful images of factories, steelworks (e.g., The Steelworks (1895)), and city streets at night (e.g., Paris Street at Night (1890s)), capturing both the grime and the artificial light of modern industry. Luce also painted still lifes using the technique, demonstrating its applicability to traditional genres, as seen in works like Still Life with Oranges (c. 1890-92).

- Théo van Rysselberghe (1862-1926): A leading figure in Belgian Neo-Impressionism. Van Rysselberghe travelled widely and applied the technique to portraits, seascapes, and North African scenes. His portraits are particularly notable, managing to combine the meticulous dot technique with a sense of psychological presence, such as in his famous Portrait of Octave Maus (1885) (Maus was the secretary of Les XX) or Maria Sèthe at the Harmonium (1891). He played a key role in spreading Neo-Impressionism beyond France, particularly through the avant-garde group Les XX (Les Vingt) in Brussels. Spreading the dots internationally, showing the technique wasn't confined to Paris.

- Other Minor Figures: While less central, artists like Albert Dubois-Pillet, Charles Angrand, and Hippolyte Petitjean also experimented with Divisionist principles and Pointillist techniques, further demonstrating the spread of these ideas beyond the core group. Dubois-Pillet, for instance, was a co-founder of the Salon des Indépendants alongside Seurat and Signac, and his landscapes and still lifes show a distinct, though sometimes less rigorous, application of the technique. Angrand's work, particularly his drawings and later paintings, explored tonal variations and color contrasts using Neo-Impressionist methods. Petitjean applied the technique to landscapes and figure studies with a delicate touch, often resulting in delicate, almost pastel-like effects despite the distinct marks. Their contributions, though perhaps less celebrated, reinforce that the scientific approach to color resonated with a wider circle of artists seeking new directions.

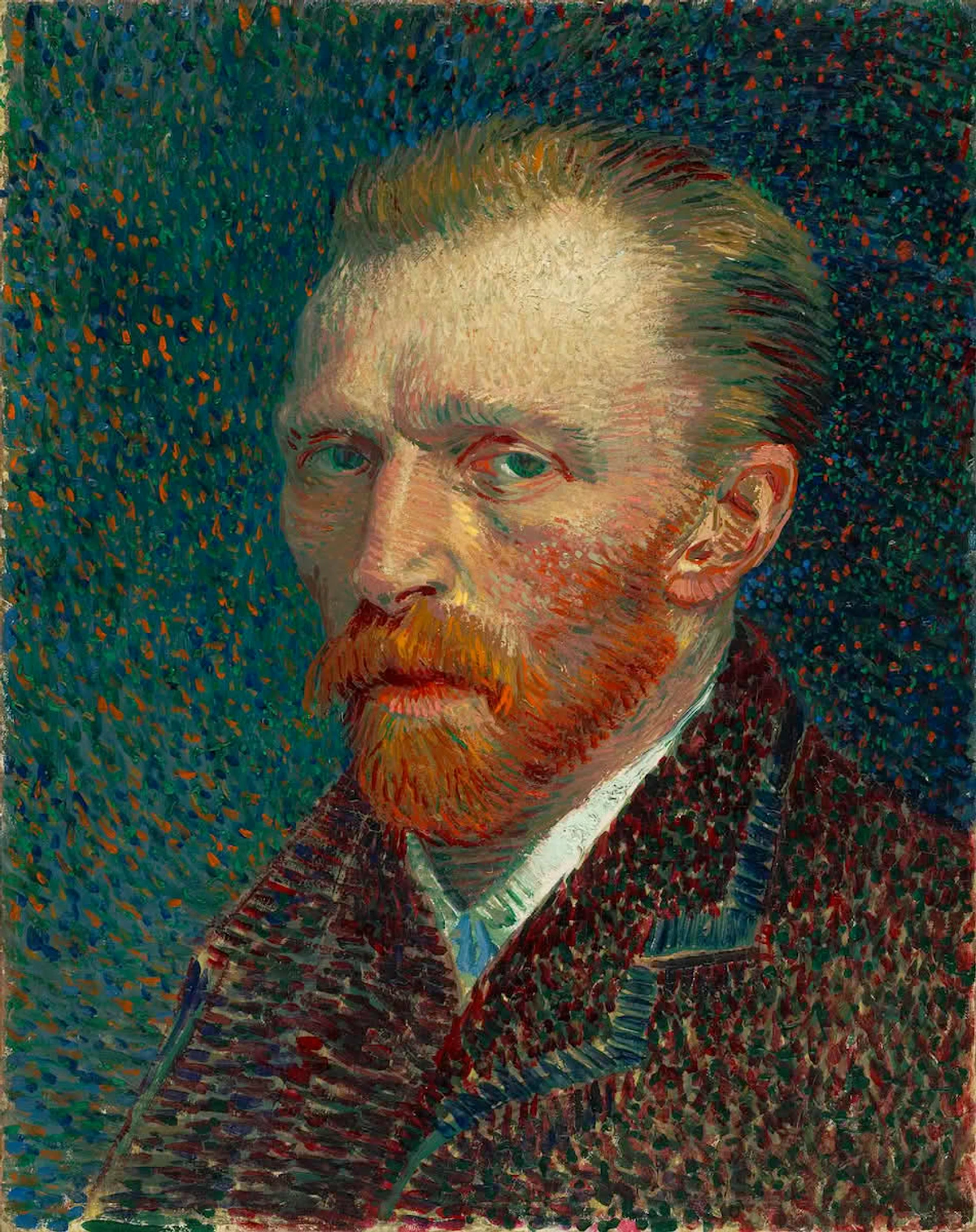

- Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890): Okay, Van Gogh wasn't a Pointillist in the strict sense. He never adopted the tiny, uniform dots or the rigid scientific adherence. However, his time in Paris (1886-1888) brought him into direct contact with Seurat, Signac, and Pissarro. You can clearly see the influence of Neo-Impressionism in his work from this period and shortly after. He started using brighter colors, juxtaposing complementary colors (like the blues and oranges/yellows in his self-portraits or Starry Night), and applying paint in distinct, separate brushstrokes – sometimes short dashes, sometimes swirls, but definitely not smoothly blended. He absorbed the idea of colors interacting dynamically (Divisionism) but applied it with his own unique, expressive energy. It’s like he took the scientific theory and ran it through his passionate, emotional filter. For more on his unique path, check out the Ultimate Guide to Van Gogh. Even Van Gogh got a little dotty, or at least, got influenced by the dots.

Seeing how these different artists adapted the core ideas really highlights the dynamism within Neo-Impressionism. It wasn't monolithic; it was a set of principles (Divisionism) that artists explored in individual ways. It makes the movement feel more alive, less like a rigid formula. It shows that even within a seemingly strict framework, there's room for personal expression and evolution.

Materials, Patience, and the Grind

Let's be honest, looking at La Grande Jatte makes my hand hurt just thinking about it. Pointillism wasn't just a theory; it was a labor-intensive process demanding monk-like patience. I imagine a lot of deep breaths were involved, maybe even some muttered curses under their breath. It certainly wasn't a technique for the faint of heart, or the easily distracted. I mean, applying millions of tiny dots? My wrist aches just contemplating it. I picture myself starting strong, full of scientific zeal, only to be found days later, slumped over the canvas, muttering about carpal tunnel and the futility of existence, surrounded by a mere square inch of completed dots. The sheer physical and mental toll must have been immense. It makes my own struggles with finishing detailed pieces feel... less dramatic, but still relatable. That feeling of the grind, the repetitive task building towards something larger – it's a universal creative challenge.

- Paints: Neo-Impressionists typically used oil paints, just like their Impressionist predecessors. However, the emphasis was on using pure pigments with minimal mixing on the palette. They needed a wide range of vibrant colors straight from the tube to achieve the desired juxtapositions. The availability of new synthetic pigments in the late 19th century was actually crucial here. Think vibrant cadmium yellows and oranges, intense cobalt blues, and synthetic ultramarine. These pigments, developed through advancements in chemistry, offered a level of purity, saturation, and lightfastness that older, earth-based pigments often couldn't match. Their chemical properties meant they could be used in their most brilliant, unadulterated form, perfectly suiting the Divisionist goal of maximizing luminosity through optical mixing. It was a perfect storm of scientific theory meeting chemical innovation. Some experimented with different binders or mediums to control drying time and consistency, but the core remained oil paint. They needed the brightest colors they could get their hands on to make those dots sing.

- Brushes: Small, often round-tipped brushes were essential for applying consistent dots. As noted, the size and shape of the mark could vary – Signac's later, larger squares or Cross's more block-like strokes demanded slightly different handling than Seurat's precise dots. You needed the right tool for your specific brand of dotting. Precision was key, but there was room for individual touch.

- Surface: They painted primarily on canvas, prepared with traditional grounds. The texture of the canvas wasn't as critical as for impasto techniques, as the effect relied on the dots themselves. The canvas was just the grid, the foundation for the optical illusion.

- The Time Factor: This is the big one. Imagine meticulously placing thousands, maybe millions, of tiny dots according to a complex color plan. Seurat worked on La Grande Jatte for two years. Two years! It required intense concentration and a systematic approach utterly different from the quick, alla prima methods of many Impressionists. It's not exactly the kind of technique you dash off on a whim. You had to be committed, perhaps even a little obsessive. It makes you wonder about the personalities drawn to such a demanding method – were they seeking order in a chaotic world, or just really, really patient? Maybe both. It's certainly not a technique for the easily bored, which, if I'm being truthful, probably includes me most days. The kind of focus required reminds me sometimes of the concentration needed to pull off intricate details in some contemporary artworks available today, though maybe without the rigid scientific overlay! It's a testament to their dedication, or maybe just stubbornness. It highlights the physical and mental labor involved in this seemingly simple technique.

- Cost and Accessibility: The new synthetic pigments, while brilliant, could also be more expensive than traditional earth pigments. Combined with the sheer amount of time and labor required for large-scale Pointillist works, this technique wasn't cheap or quick. This might have contributed to the relatively small number of artists who fully committed to it and potentially impacted its commercial viability compared to more rapidly produced Impressionist works. It was an investment in both materials and time, a commitment not everyone could make.

Framing the View: Seurat's Borders and Frames

It’s easy to focus just on the dots within the main image, but Seurat, in particular, paid careful attention to the transition between the painting and its surroundings. He often created painted borders directly on the canvas, composed of dots of complementary colors to those adjacent in the main scene. Think of it as an optical buffer zone, designed to intensify the colors within the painting and manage the transition to the frame and the wall. For La Grande Jatte, he even designed a specific plain white wooden frame, believing it wouldn't interfere with the optical effects the way a traditional ornate gilt frame might. It shows just how integrated his thinking was – the painting didn't stop at the edge of the scene; the entire viewing experience was considered part of the scientific system. It's a level of control that makes my head spin slightly, but you have to admire the dedication. He was thinking about the whole package, frame and all. It wasn't just about the canvas; it was about the entire presentation and how it affected perception.

Reception and Criticism: Dots Spark Debate

So, how did the world react to all these dots? When Seurat unveiled A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte at the pivotal 8th (and final) Impressionist exhibition in 1886 (an event held, by the way, in rooms rented above the prestigious Maison Dorée restaurant), and later that year at the Salon des Indépendants (an alternative exhibition space he helped found, reflecting perhaps some of that anarchist, anti-establishment spirit shared by others like Signac and Luce, who sought independence from the official Salon system), it didn't exactly get quiet nods of approval. It caused a stir. Imagine walking into a gallery expecting the hazy, fleeting brushstrokes of Monet or Renoir and being confronted with this enormous, meticulously dotted canvas. It must have felt... weird. Cold, even. Early exhibitions weren't limited to Paris; the work was shown by the Belgian avant-garde group Les XX (Les Vingt) in Brussels in 1887, and Neo-Impressionist works appeared in other independent group shows, helping spread awareness (and controversy). While initially some Neo-Impressionist works might have appeared briefly at established dealers like Galerie Durand-Ruel, the movement largely found its home in these alternative, artist-run salons. They were definitely shaking things up, challenging the established norms of the art world.

Critics were sharply divided. Some, like Félix Fénéon, who famously coined the term "Neo-Impressionism" in his review Les Impressionnistes en 1886 published in La Vogue, championed the scientific basis (Divisionism, or Chromoluminarism as Seurat sometimes preferred) and the luminosity achieved through optical mixing. Fénéon saw it as a logical, progressive step beyond Impressionism, a rational evolution of painting. He wasn't alone in his support; figures associated with the Symbolist literary movement, whom Fénéon also championed, were often intrigued. Writers like Gustave Kahn, himself a poet and critic interested in new forms, were generally supportive, seeing parallels between the analytical approach to color and their own experiments with language and sensation. The Symbolists' interest in suggestion, structure, and sensory experience beyond direct representation resonated with the Neo-Impressionists' methodical approach to building an image and sensation through calculated color interactions. While direct personal connections between artists like Seurat and major Symbolist figures like Stéphane Mallarmé or Paul Verlaine might be debated, they certainly moved in overlapping avant-garde circles, shared venues, and were discussed by the same critics, suggesting a shared intellectual climate. Early support also came from a few patrons or early collectors, though perhaps not in huge numbers initially. The Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren was an early admirer, and figures like Antoine de La Rochefoucauld, an artist and esoteric Symbolist himself, acquired works. Later, Paul Signac would become the movement's key theorist, codifying its principles in his influential book D'Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionnisme (1899), which traced a lineage for their color theories back to earlier masters. So, they had their champions, seeing the method and the science as the way forward, a new path for art.

Others, however, found the technique laborious, static, and overly systematic. Common criticisms included its perceived 'coldness' and 'lack of emotion' compared to the perceived warmth and spontaneity of Impressionism. Some felt the scientific approach stifled artistic expression, reducing painting to a mechanical formula. The term "Pointillism" itself was initially used somewhat derisively by critics like Arsène Alexandre, emphasizing the mechanical nature of the dot application – like calling someone "dotty," maybe? Influential novelist and critic Joris-Karl Huysmans, who had initially championed Impressionism, was famously scathing about La Grande Jatte, finding its figures rigid and lifeless, comparing them to toy soldiers. He saw it as a betrayal of Impressionism's vitality, a step backward into stiffness. Another critic, Octave Mirbeau, while sometimes supportive of individual artists, could also be critical of the perceived systematization. They saw the dots, but not the soul, or perhaps felt the soul was lost in the system.

Traditionalists were baffled, and even some fellow avant-garde artists kept their distance. Pissarro, as mentioned, tried it but found it too constraining, specifically arguing that the slow, methodical process made it difficult to capture the fleeting effects of light and movement that were central to his Impressionist aims. It's easy to imagine the arguments in Parisian cafes – "It's the future of painting!" versus "It's just soulless mechanics!" It reminds me of debates around new technologies today; initial skepticism and mockery often precede wider acceptance or influence. New, challenging art often faces ridicule before acceptance, doesn't it? It's a pattern that seems to repeat throughout history, drawing a parallel to contemporary art world reactions. I've certainly had my own work described in ways that felt... less than flattering, sometimes focusing on the technique or perceived lack of emotion rather than the intent. It's a reminder that putting something new out there, something that challenges expectations, is always going to invite strong opinions, both good and bad. Pointillism, despite its limited core practitioners, certainly forced people to think differently about how color and light could be represented, even if they didn't like the answer Seurat provided. It definitely wasn't boring, even if some found the paintings themselves a bit stiff. It sparked conversation, which is often a sign of something important, something that challenges the status quo. It's also worth noting that commercially, Pointillist works weren't an immediate sensation during the artists' lifetimes. While some found buyers, they didn't achieve the widespread popularity or market success of many Impressionist works, adding another layer to their challenging initial reception.

Common Subjects: Painting Modern Life, Dot by Dot

So, what did these patient dot-makers actually paint? Well, much like their Impressionist predecessors, the Neo-Impressionists were drawn to scenes of modern Parisian life and leisure. Think parks (La Grande Jatte), circuses (Seurat's The Circus), cafes, and seaside resorts. They continued the Impressionist interest in capturing the contemporary world rather than historical or mythological subjects. They painted what they saw around them, the world of the late 19th century. What aspects of modern life would you choose to render in a million tiny dots? I find myself wondering what a Pointillist take on a busy city street today, or maybe even a quiet moment with a laptop, would look like. Would the dots capture the glow of screens, the blur of traffic, or the stillness of concentration? It's a fun thought experiment, applying that meticulous approach to our own chaotic, pixelated reality.

However, the treatment of these subjects differed. Where Impressionism captured fleeting moments with loose brushwork, Pointillism's meticulous technique often resulted in a more frozen, timeless quality. The figures in La Grande Jatte feel almost like statues arranged in a formal composition, a stark contrast to the lively bustle often seen in Renoir's work. It's as if the scientific approach bled into the mood, creating scenes observed with a certain detachment or analytical coolness. Maybe the sheer effort involved made spontaneity impossible? I know if I spent two years on one painting, I'd probably want everything to hold perfectly still. It's the difference between a snapshot and a carefully posed photograph, a moment captured for eternity rather than a fleeting impression. It's fascinating how the meticulous technique transforms the depiction of modern life, making the ordinary feel monumental or timeless.

Landscapes and seascapes were also incredibly popular, especially for Signac and Cross, who were captivated by the intense light of the Mediterranean coast. The Pointillist technique (Divisionism) was well-suited to capturing the shimmering effects of sunlight on water and foliage, breaking down the light into its constituent colors. The dots really lent themselves to capturing that intense, vibrating light, making the landscapes feel alive with color and energy.

Beyond these, Neo-Impressionists also tackled more traditional genres. Portraits were painted by artists like Théo van Rysselberghe, who managed to combine the meticulous dot technique with a sense of psychological presence, such as in his famous Portrait of Octave Maus (1885) or Maria Sèthe at the Harmonium (1891). Still lifes were also rendered in the Pointillist style, as seen in works by Maximilien Luce or Van Rysselberghe, applying the color theories to arrangements of objects rather than figures or landscapes. Maximilien Luce, as noted earlier, stands out for his focus on urban labor and industrial landscapes. He used the dot technique to depict factories, workers, and construction sites, bringing a social-realist edge to Neo-Impressionism that was less common among the others (perhaps linked to his anarchist views). He used the dense, tightly packed dots to convey the grime and energy of industrial scenes, making the technique feel grounded and powerful, not just airy and luminous. It shows the technique wasn't just limited to sunny afternoons in the park or traditional subjects; it could also be applied to the grittier side of modern life, reflecting the artists' engagement with the social issues of their time. Exploring these different themes helps us understand how to read a painting and see beyond just the technique. It's about the subject and the style, and how they interact.

Pointillism vs. Divisionism vs. Neo-Impressionism: Clarifying Terms

These terms are often used interchangeably but have distinct nuances. It can feel a bit like learning a secret code, but it's worth clarifying to understand the movement precisely. Think of it as the difference between a specific tool, the theory behind using it, and the group of people who used it.

Term | Focus | Description | Example Relation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pointillism | The Technique | Applying small, distinct dots or marks of color. | How it's painted. |

| Divisionism (aka Chromoluminarism) | The Color Theory | Separating color based on scientific principles (like simultaneous contrast) for optical mixing. | Why colors are chosen. |

| Neo-Impressionism | The Art Movement | The broader group of artists (led by Seurat/Signac) who used Divisionist theory, often via Pointillism. | The historical group. |

Essentially, Pointillism was the primary technique (though with variations in mark-making) used by Neo-Impressionist artists to achieve the effects described by Divisionist theory. Got it? Good. Now you're in the know. It's a useful distinction for understanding the intellectual rigor behind the dots.

Legacy and Influence of Pointillism

While the strict application of Pointillism was relatively short-lived and adopted by relatively few artists due to its laborious nature, its impact was significant and, in some ways, quite surprising. It wasn't just a dead end; it planted seeds that grew into vibrant new movements. It's like the dots scattered and took root elsewhere, influencing artists who might not have used the technique but absorbed its core ideas about color and light. It was a catalyst for change.

- Liberation of Color: Its emphasis on pure, unmixed color (Divisionism) was arguably its most potent legacy. It showed artists that color could be broken down, analyzed, and used scientifically or purely for its own sake. This directly paved the way for the Fauves (like Matisse and Derain) around 1905. They took the idea of intense, non-naturalistic color and ran with it, ditching the scientific theory and the tiny dots for bold, expressive brushstrokes and wild color choices. You could say Pointillism built the launchpad, and Fauvism was the rocket. It's almost funny how the meticulous, scientific approach of the Pointillists led to the 'wild beasts' of Fauvism, who seemed to throw the rulebook out the window! (See: Ultimate Guide to Fauvism). Check out the Ultimate Guide to Henri Matisse for more on one of Fauvism's key figures. Color unleashed! The Fauves took the Pointillists' vibrant palette and used it for emotional expression rather than scientific accuracy.

- Influence on Abstraction: The focus on color relationships, structured composition, and the very idea that the application of paint (the dot itself) could be a visible, fundamental element contributed to early abstract movements. Think about Orphism (Robert Delaunay), with its vibrant discs of pure color interacting. Even aspects of Cubism, while visually very different, shared a certain analytical, structured approach to breaking down form, perhaps echoing Neo-Impressionism's methodical deconstruction of color. (See: Ultimate Guide to Cubism). The journey towards pure abstraction often involved dissecting the elements of painting – color, line, form – and Pointillism was an early, crucial step in analyzing color as its own force, independent of representational form. Delve deeper into the history of abstract art. Beyond these direct links, the analytical approach to breaking down visual information into constituent parts can be seen as a precursor to later abstract artists who explored geometric forms and color relationships, like Piet Mondrian (though his work is far removed visually) or even the systematic exploration of visual effects in Op Art. Breaking down color led to breaking down form, paving the way for non-representational art and later explorations of pure visual phenomena.

- The Italian Divisionists: In Italy, a distinct branch of Divisionism flourished around the same time and into the early 20th century. Artists like Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, Angelo Morbelli, and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo adopted the core principle of optical mixing (Divisionism) but often used different techniques than the French Pointillists. Instead of dots, they frequently employed long, filament-like brushstrokes or threads of pure color placed side-by-side. The effect could be less 'dotted' and more shimmering or fibrous. Thematically, Italian Divisionists often leaned towards Symbolism, tackling subjects like rural life, allegory, and social commentary with this luminous technique. Segantini's Alpine landscapes (like The Punishment of Lust (1891)), Previati's large-scale historical or symbolist works, and Pellizza da Volpedo's monumental painting The Fourth Estate (1901), depicting a workers' strike, are powerful examples of this related, yet distinct, movement. It’s fascinating how the core scientific idea spread and was adapted to different national contexts and artistic temperaments, showing the flexibility of the underlying theory. How could the same fundamental principle be interpreted and applied so differently across countries and artistic temperaments? It's a testament to the richness of artistic exploration. The dots went international, changing form along the way.

- Modern Analogies (The Unforeseen Echo): It's fascinating, almost ironic, how Pointillism finds echoes in modern technologies Seurat could never have dreamed of. Color television screens, computer monitors (pixels), and four-color halftone printing all rely on small, distinct units of color (dots or pixels of red, green, blue for screens; cyan, magenta, yellow, black dots for printing) that blend optically in our eyes to create a full spectrum of colors and a complete image. Seurat was trying to achieve with painstaking brushwork what technology now does instantly. It makes you wonder what he’d think of a high-resolution digital display – perhaps a validation of his theories, or maybe a bit depressing that a machine could do it so easily? There's a sense of wonder and irony in how a painstaking manual technique foreshadowed ubiquitous digital technology. Beyond screens and printing, you can see similar principles of optical mixing at play in textile design, where different colored threads are woven together to create blended hues from a distance, or in mosaic art, where small tiles (tesserae) of different colors are arranged to form images that blend in the viewer's eye – much like Signac's later technique! It's a reminder that artistic experiments, even those that seem niche or overly technical at the time, can sometimes foreshadow future ways of seeing and creating across various mediums. Understanding this connection makes looking at both a Seurat and a modern screen or a mosaic a richer experience, doesn't it? Art predicting technology, in a way, or at least exploring the same principles of visual perception. As a contemporary artist, seeing this analytical approach to color and its unexpected echo in digital pixels feels both validating – that the fundamental principles of visual perception are timeless – and slightly surreal. It's a fascinating historical note that connects the painstaking manual labor of the past to the instant digital displays of today.

- Enduring Fascination: The unique visual appeal – the shimmering light, the vibrant color, the tension between the tiny dots up close and the coherent image from afar – continues to fascinate viewers. It’s a technique that actively engages our perception. It also provides ongoing art inspirations for contemporary artists exploring color theory, pattern, digital aesthetics, or simply the meditative quality of repetitive mark-making. You might even see echoes in some digitally-inspired contemporary artworks available today. The spirit of the dot lives on, in different forms, proving that even a seemingly rigid framework, like the one explored at the artist's museum near 's-Hertogenbosch, can spark endless creativity.

So, while you won't find many artists today meticulously placing millions of dots according to Chevreul's laws, the core ideas – analyzing color, understanding optical effects (Divisionism), structuring composition – resonated far beyond the Neo-Impressionist circle. It was a short-lived movement with a long shadow, a scientific experiment that unexpectedly fueled the future of art. While the technique was short-lived, the ideas behind it were revolutionary and continue to resonate. It was a bold experiment that changed how we see color, even if the dots themselves eventually faded into the background of art history. It reminds us that sometimes the most radical ideas come from unexpected places, like a scientist's lab or a meticulously dotted canvas.

Appreciating Pointillist Art: Tips for Viewers

To fully experience Pointillist paintings, you need to engage with them actively. It's not just about looking; it's about how you look. It requires a bit of effort on your part, but the payoff is worth it. What secrets do these dots hold if you just take a moment to really see them?

- Play with Distance: Move back and forth. Observe how the dots merge into forms and colors from a distance, then step closer to admire the intricate application and individual hues. Notice the variations in mark-making if you're looking at works by different artists like Signac or Cross compared to Seurat. This is the essential Pointillist dance, the key to unlocking the optical effect. Think of this playing with distance as the "secret handshake" of Pointillism, the required interaction between the viewer and the artwork.

- Focus on Light: Notice how effectively the technique captures the vibration and luminosity of light, whether on water, foliage, or figures. They were trying to paint light itself, and the dots are their way of breaking down and reconstructing it.

- Analyze Color: Look for the deliberate juxtaposition of complementary and analogous colors. How do they interact to create the overall effect? Consider Seurat's painted borders if present – how do they influence the main image? It's a masterclass in color theory (Divisionism) in action, a visual demonstration of scientific principles.

- See the Structure: Appreciate the underlying compositional order and balance, often a hallmark of the style. Look for those frieze-like arrangements or orthogonal lines mentioned earlier. Understanding how to read a painting involves recognizing these structural choices. It's not just random dots; it's a carefully constructed world, built on a foundation of geometry and planning.

- Visit Museums: See major Pointillist works in person at institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago (La Grande Jatte), MoMA New York, Musée d'Orsay (Paris), and the National Gallery (London). The Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands also has a fantastic collection. Experiencing art live, whether historical movements or contemporary works (like those available here or seen in dedicated spaces like the artist's museum near 's-Hertogenbosch), offers unparalleled insight. Explore guides to the best museums for modern art. Seeing the dots up close and then stepping back is an experience you can only get in person, truly appreciating the scale and detail. When I look at these works, I'm always struck by the tension between the micro and the macro – the incredible detail up close and the cohesive, luminous image from afar. It's a constant reminder that the whole is truly greater than the sum of its parts, and that sometimes, you need to step back to see the full picture.

A Note on Conservation: Preserving the Dots

Looking after these dotted marvels presents some unique conservation challenges. Firstly, some pigments popular at the time, like zinc yellow or certain cadmium reds, in addition to zinc white (zinc sulfide), which Seurat sometimes used for its brightness, have unfortunately proven unstable and can darken or change color over time when exposed to light and humidity, altering the intended color balance. This degradation often occurs due to chemical reactions, such as the pigment reacting with sulfur compounds in the air or other pigments, leading to the formation of darker compounds. Imagine spending two years getting the dots just right, only for chemistry to betray you a century later! It's a heartbreaking thought for both the artist and the conservator. Secondly, the textured surface created by the multitude of distinct dots makes cleaning tricky. Dust and grime can easily get trapped between the dots, and traditional surface cleaning methods might risk flattening or disturbing the carefully applied paint points. Conservators need specialized techniques, often involving careful work under magnification, to clean these works without damaging their unique character. It’s a reminder that preserving art involves not just appreciating the artist's vision, but also understanding the physical materials they used and the challenges they pose over time. It's a delicate balance, much like the paintings themselves, requiring immense skill and patience, much like the original creation. My heart goes out to the conservators battling against time and chemistry to keep these shimmering surfaces intact. Fortunately, ongoing research and technological advancements in art conservation are continually developing new, less invasive methods to address these specific challenges, offering a note of hope for the long-term preservation of these unique works. You can learn more about the challenges of preserving different types of art in guides like Comprehensive Painting Care Guide or When to Restore Artwork.

Conclusion: A Calculated Radiance

Pointillism, though a demanding and relatively short-lived technique in its purest form, represents a crucial moment in art history. Spearheaded by Georges Seurat – whose Conté drawings and color studies reveal the depth of his planning and sensitivity – and championed by Paul Signac, it fused artistic vision with scientific inquiry, attempting to capture light and color with unprecedented vibrancy and rationality. By meticulously applying dots or marks of pure color (though with subtle variations in technique among artists like Cross and Luce), the Neo-Impressionists created works of shimmering luminosity and structured beauty that challenged Impressionist spontaneity. They explored a range of subjects, from modern leisure and landscapes to portraits and still lifes, and even the grittier realities of industrial life. Despite facing sharp criticism from figures like Huysmans alongside praise from Fénéon and Symbolist-aligned critics, and despite the inherent conservation challenges (including issues with certain pigments like zinc yellow and cadmium reds), Pointillism paved the way for future explorations of color and form in Modern Art, including movements like Fauvism and the related Italian Divisionism, and even influencing later abstract trends. Its unique visual language, controversial reception, theoretical underpinnings (Divisionism / Chromoluminarism), connection to anarchist ideals for some practitioners, and influential legacy (echoed even in modern technology like pixels, textiles, and mosaics) ensure Pointillism's enduring fascination and importance within the broader history of art. While the technique itself was short-lived, the ideas behind it were revolutionary and continue to resonate. It was a bold experiment that changed how we see color, even if the dots themselves eventually faded into the background of art history. It reminds us that sometimes the most radical ideas come from unexpected places, like a scientist's lab or a meticulously dotted canvas. And honestly, the sheer, stubborn dedication required? That's something I can appreciate, even if my own artistic journey takes a different, less dotted path. It makes me think about my own artist's timeline and the choices that shape a creative life.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- What is the main idea behind Pointillism? The main idea is optical mixing (Divisionism): using small dots or marks of pure color that blend in the viewer's eye to create perceived colors and forms, aiming for greater luminosity than mixing pigments on a palette. It's about letting your brain do the blending, turning the viewer into an active participant in the creation of the image. It's the why behind the dots.

- Who invented Pointillism? Georges Seurat is credited as the inventor and main pioneer of the Pointillist technique and the Neo-Impressionist movement. His extensive Conté crayon drawings and color studies were essential preparatory works, showing the rigorous planning behind the dots. He was the mastermind behind the dots, the one who codified the system.

- What's the difference between Pointillism and Impressionism? Impressionism generally uses looser, quicker brushstrokes to capture fleeting moments and light effects intuitively. Pointillism uses tiny, distinct dots or marks applied methodically based on scientific color theory (Divisionism), resulting in more structured and static compositions. Think feeling vs. formula, though that's a bit simplistic! It's the difference between a spontaneous sketch and a calculated mosaic, a fleeting impression versus a constructed reality.

- What's the difference between Pointillism and Divisionism? Pointillism refers specifically to the technique of using dots or marks (though mark-making varied slightly). Divisionism (also called Chromoluminarism by Seurat) is the underlying color theory about separating colors for optical mixing based on scientific principles like simultaneous contrast. Pointillism is the main way Divisionist theory was put into practice by the Neo-Impressionists. Think how (dots/marks) versus why (optical mixing theory). One is the method, the other is the science that justifies it.

- Is Pointillism hard to do? Yes, creating a large-scale Pointillist painting is extremely meticulous, precise, and time-consuming due to the need to apply countless individual dots according to a specific plan. It requires immense patience – maybe the kind you develop waiting for software updates, but applied to paint. Definitely not for the impatient, or those who prefer quick results. It's a test of endurance as much as skill.

- What kind of paint and materials did Pointillists use? They primarily used oil paints on canvas. The key was using pure pigments (often newly available synthetic ones like cadmiums for brightness, though some like zinc white, zinc yellow, or certain cadmium reds caused later conservation issues due to chemical reactions causing darkening or color change) with minimal mixing on the palette and applying them with small, often round-tipped brushes. No special secret materials, just a lot of patience and a good understanding of color theory (Divisionism). And maybe a magnifying glass for those tiny dots. The materials were traditional, but the application was revolutionary.

- Did all Pointillists paint using the exact same dots? No. While Seurat is known for his relatively uniform dots, artists like Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross evolved to use larger, more square or block-like marks later in their careers, still based on Divisionist principles. Maximilien Luce sometimes used denser dotting. So, there were variations in mark application within the movement. They had their own handwriting, even in dots, showing that individual style could still emerge within the shared framework.

- Who were some important critics or supporters of Pointillism? Félix Fénéon was a key supporter who coined "Neo-Impressionism." Other critics like Gustave Kahn were generally positive, sometimes linking it to Symbolist ideas due to shared interests in structure and sensory experience. However, critics like Joris-Karl Huysmans and Arsène Alexandre were often harsh, finding it cold or mechanical. Camille Pissarro initially tried the technique but later rejected it as too restrictive. A few early patrons like Emile Verhaeren and Antoine de La Rochefoucauld also offered support. It definitely wasn't universally loved, sparking significant debate in the art world.

- Were Pointillist artists involved in politics? Yes, several prominent Neo-Impressionists, including Paul Signac, Maximilien Luce, Camille Pissarro (during his phase), and Henri-Edmond Cross, held strong anarchist beliefs. They sometimes contributed illustrations or funds to anarchist publications like Les Temps Nouveaux. This political stance also manifested in their approach to the art world, notably in their involvement in founding the Salon des Indépendants, an alternative exhibition space free from the strictures of the official Salon, allowing artists to show their work without jury approval – a truly anti-establishment move. Art and activism, side by side, showing that their desire for radical change extended beyond the canvas.

- What conservation challenges do Pointillist paintings face? Pointillist paintings face unique challenges due to the materials and technique. Some pigments used, like zinc yellow or certain cadmium reds, can be unstable and darken or change color over time, altering the intended optical mix. Additionally, the textured surface created by the distinct dots makes cleaning difficult, as dust can get trapped and traditional methods might damage the paint points. Conservators require specialized techniques to preserve these works.

- Why did Pointillism as a movement end? Several factors contributed. Seurat's early death in 1891 removed its primary innovator. The technique was extremely laborious, discouraging many artists (even Pissarro found it too slow). The cost of materials and labor was also a factor. And perhaps most importantly, new art movements like Fauvism and Cubism emerged in the early 1900s, capturing the avant-garde imagination with more expressive or radically different approaches to form and color. Artistic tastes simply moved on, as they always do. It wasn't a failure, just part of the evolution of art history. The art world is always moving, always seeking the next new thing.

- Was Pointillism considered successful? It depends on how you define "successful." As a dominant, long-lasting movement, maybe not – few artists fully committed to it, and its peak lasted less than two decades. Commercially, it wasn't a huge immediate hit either, often facing ridicule and specific criticisms about being 'cold' or 'mechanical' from critics like Huysmans. However, in terms of influence, it was hugely successful. Its ideas about color theory (Divisionism) and optical mixing directly impacted subsequent movements like Fauvism and Orphism, and its structured approach contributed to the analytical trends leading towards abstraction. It also gained international exposure through groups like Les XX in Brussels and inspired related movements like Italian Divisionism (Segantini, Pellizza da Volpedo). So, while maybe not a blockbuster in its own day, its ideas had legs and significantly shaped the course of Modern Art. I guess success in art isn't always about immediate popularity; sometimes it's about planting seeds that bloom later. A quiet success, perhaps, but a profound one.

- Are there modern Pointillist artists? While Pointillism as a distinct movement largely ended in the early 20th century, contemporary artists sometimes utilize dot techniques within their work. However, this is often for textural effects, pattern creation, referencing digital pixels (like Chuck Close's portraits, though that's more grid-based), or exploring process, rather than strictly adhering to Neo-Impressionist optical mixing theories (Divisionism). You might see echoes in pop art (like Lichtenstein's Ben-Day dots) or digital art, but it's rarely 'Pointillism' in the Seurat sense. Some artists today might explore similar ideas through different means, perhaps visible in online galleries. The spirit of the dot lives on, in different forms and contexts.

- Where can I see famous Pointillist paintings? Major examples can be found in top museums worldwide, including the Art Institute of Chicago (La Grande Jatte), the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the National Gallery in London, and the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands. Explore guides to the best museums for modern art. Seeing them in person really lets you do the "step back, step close" dance! It's the best way to truly appreciate the technique and the scale of these works.

- How large are Pointillist paintings? Pointillist works vary in size, but some of the most famous, like Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, are monumental. La Grande Jatte measures approximately 7 by 10 feet (about 2 by 3 meters). This large scale is a significant aspect of their impact and highlights the incredible labor involved in covering such a vast surface with tiny dots. Other works were smaller, but still demanded significant time and precision. Imagine the sheer physical undertaking! It adds another layer of awe when you see them in person.

- Did Pointillist artists paint outdoors (en plein air)? While Neo-Impressionists, like the Impressionists before them, often studied light and color effects outdoors, the meticulous and time-consuming nature of the Pointillist technique (Divisionism) usually required the paintings to be executed in the studio. Unlike the quick, spontaneous brushwork of en plein air Impressionism, applying countless tiny dots according to a complex plan was a process best suited to the controlled environment of the studio. So, they gathered observations and made studies outdoors, but the final, large-scale works were typically studio creations.