Georg Baselitz: Beyond the Flip – My Personal Journey into His Art

Dive deep into the world of Georg Baselitz with a personal guide. Explore his upside-down paintings, raw sculptures, and provocative journey through post-war German art and Neo-Expressionism.

Georg Baselitz: Beyond the Flip – My Personal Journey into His Art

Let's be honest, when you hear Georg Baselitz, the first thing that probably pops into your head is "the upside-down guy," right? And you wouldn't be wrong. It's arguably his most famous contribution, or at least, his most instantly recognizable move. I remember the first time I saw one – a visceral, heavily painted figure hanging defiantly inverted. My initial reaction was probably something like, "Huh. Okay... why?" It felt a bit like a gimmick, maybe? Like turning the volume knob up to eleven just because you can. (And honestly, who hasn't been tempted to do that in their own creative process?) But sticking with Baselitz, digging a little deeper, reveals so much more than just an orientation trick. He's a pivotal figure in post-war European art, a key player in Neo-Expressionism, and an artist who consistently challenges not just what we see, but how we see it. So, let's get past the initial head-tilt and explore the world of Georg Baselitz. It's a journey worth taking, even if it occasionally feels like you're viewing it standing on your head.

From East to West: Forging an Identity in a Divided Germany

Georg Baselitz wasn't always Baselitz. He was born Hans-Georg Kern in 1938 in Deutschbaselitz, Saxony, a place that would later lend him his adopted surname. Growing up in the shadow of World War II and in the subsequent German Democratic Republic (East Germany) undoubtedly shaped his worldview. The stark realities of post-war life, the division of his country, and the imposition of a new political order created a fertile ground for rebellion and introspection.

His early artistic path wasn't exactly smooth. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine and Applied Art in East Berlin in 1956, but was expelled after just two terms for "socio-political immaturity" – essentially, for being a non-conformist in a system that demanded ideological alignment. Being expelled for 'socio-political immaturity' sounds like something straight out of a rebellious teenager's diary, doesn't it? I guess challenging the status quo started early. It reminds me a bit of those times you feel like you just don't fit the mould – frustrating, maybe, but often the start of something more interesting. He hightailed it to West Berlin in 1957, immersing himself in a different artistic climate. West Berlin, though physically isolated, was a hub of Western artistic ideas, exposed to movements like Art Informel and Tachisme, which emphasized abstraction, spontaneity, and the artist's gesture. These styles, while dominant, felt detached and perhaps too 'clean' to Baselitz. He was grappling with the raw, messy history of Germany, and these abstract approaches, while dynamic, seemed to lack the weight and directness he needed to process that trauma and identity. He also encountered the lingering ghosts of German Expressionism, an earlier movement that sought to express inner emotion and subjective experience through distorted forms and vivid colors. This resonated more deeply with him; it offered a visual language for grappling with difficult realities, a lineage he would later acknowledge and twist.

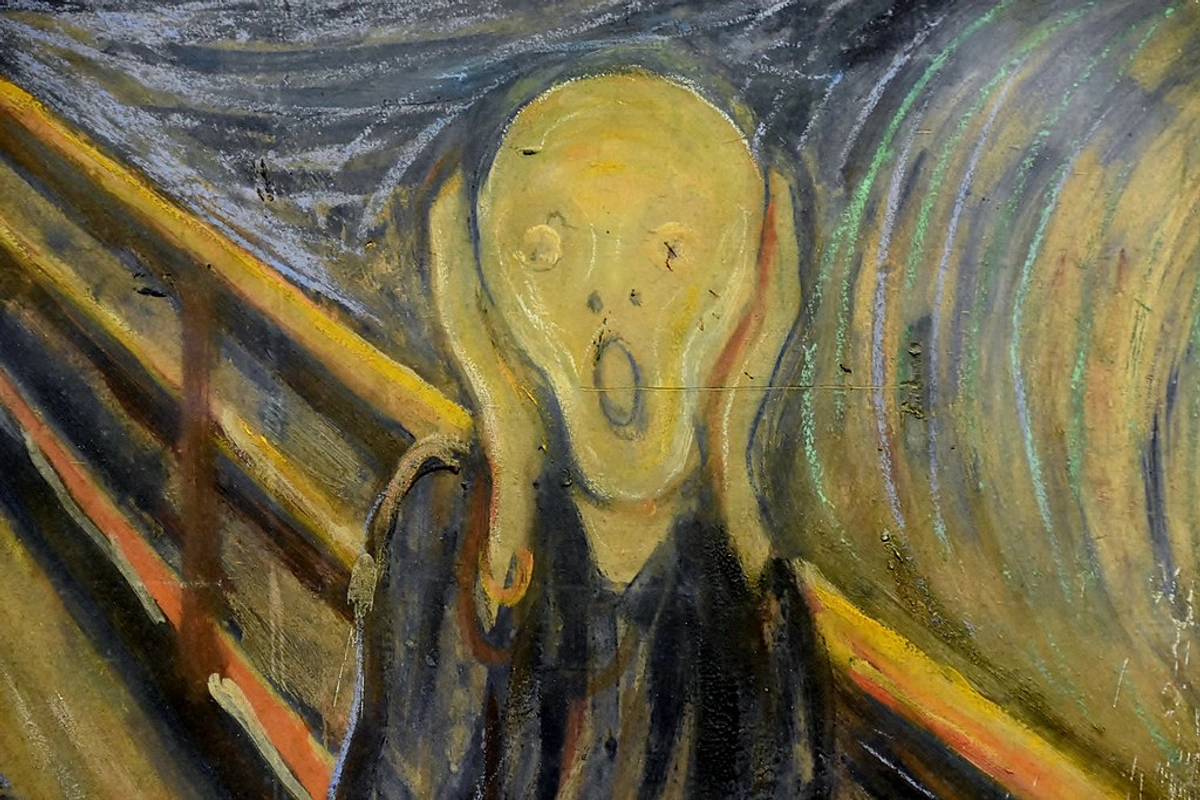

(Image: Edvard Munch's Expressionist work, like Baselitz's, sought to convey intense inner emotion, though through different means.)

He studied under Hann Trier at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in West Berlin, but even here, he wasn't content to just follow trends. He was already looking for a way out of the prevailing abstract styles, seeking something more direct, more raw, more... German, perhaps? He found kinship with fellow student Eugen Schönebeck, and together they began to forge a path away from abstraction, back towards figuration, but with a new, confrontational edge.

The Pandemonium Manifestos & Early Shockwaves

In the early 1960s, Baselitz and Schönebeck unleashed their "Pandemonisches Manifest" (Pandemonium Manifestos). These weren't polite artist statements; they were raw, aggressive declarations, almost like a punk-rock scream against the perceived elegance and detachment of Art Informel and Tachisme. They championed an art of ugliness, of dissonance, of confronting uncomfortable truths and the traumas of German history head-on. They called for a return to the 'primitive,' the raw, the unfiltered, using provocative language and imagery to shock the complacent art world.

This culminated in Baselitz's first solo exhibition in 1963 at Galerie Werner & Katz in Berlin. It caused an immediate scandal. Two paintings, "Die große Nacht im Eimer" (The Big Night Down the Drain) – depicting a figure resembling a boy masturbating – and "Der nackte Mann" (The Naked Man), were confiscated by the public prosecutor for being obscene. The titles themselves were provocative, hinting at societal decay and vulnerability. The style of these early works was raw and gestural, often employing a dark or muddy palette that amplified the visceral, uncomfortable nature of the subject matter. The charges were eventually dropped, but the incident cemented Baselitz's reputation as a provocateur. He wasn't just painting; he was throwing down a gauntlet, forcing a confrontation with societal norms and the lingering traumas of German history. It’s the kind of artistic risk that can define a career, pushing boundaries even when it’s uncomfortable – something you see throughout the history of art.

Flipping the Script: The Upside-Down Revelation

So, about that upside-down thing. In 1969, Baselitz began systematically inverting his subjects. Why? Was it just to grab attention after the early scandals? Baselitz himself has offered various explanations over the years, but the core idea seems consistent: to liberate the painting from its subject matter.

Think about it. When you see a portrait or a landscape, your brain immediately tries to interpret the story or the scene. You recognize the face, the trees, the house. Baselitz wanted to short-circuit that process. By turning the image upside down, he forces you to confront the act of painting itself – the colour, the texture, the brushstrokes, the composition – without getting bogged down by representation. He wasn't trying to destroy the image, but to make you see painting first. It's a bit like trying to read text upside down – you have to focus on the shapes of the letters, not just the meaning of the words.

"I was born into a destroyed order, a destroyed landscape, a destroyed people, a destroyed society. And I didn't want to reestablish an order: I'd seen enough of so-called order. I was forced to question everything, had to be 'naive', starting again." - Georg Baselitz

It’s a radical move. It forces you, the viewer, to work harder, to engage differently. Suddenly, a figure isn't just a figure; it's an arrangement of painted forms. A tree isn't just a tree; it's a collision of greens and browns. His technique often involves thick, impasto application, visible, energetic brushstrokes, and a palette that, while sometimes muted, can also feature jarring or intense colour combinations. The inversion emphasizes these formal qualities, making the viewer acutely aware of the paint on the canvas. While the subjects remained recognizable (portraits, landscapes, eagles), their inverted state stripped them of their conventional narrative weight, allowing the viewer to appreciate the painting as an object in itself. This approach continued and evolved over the decades, with variations in style and subject, but the core principle of inversion as a formal device remained central.

(Image: Baselitz's focus on the act of painting itself is evident in the raw energy of his brushwork and application.)

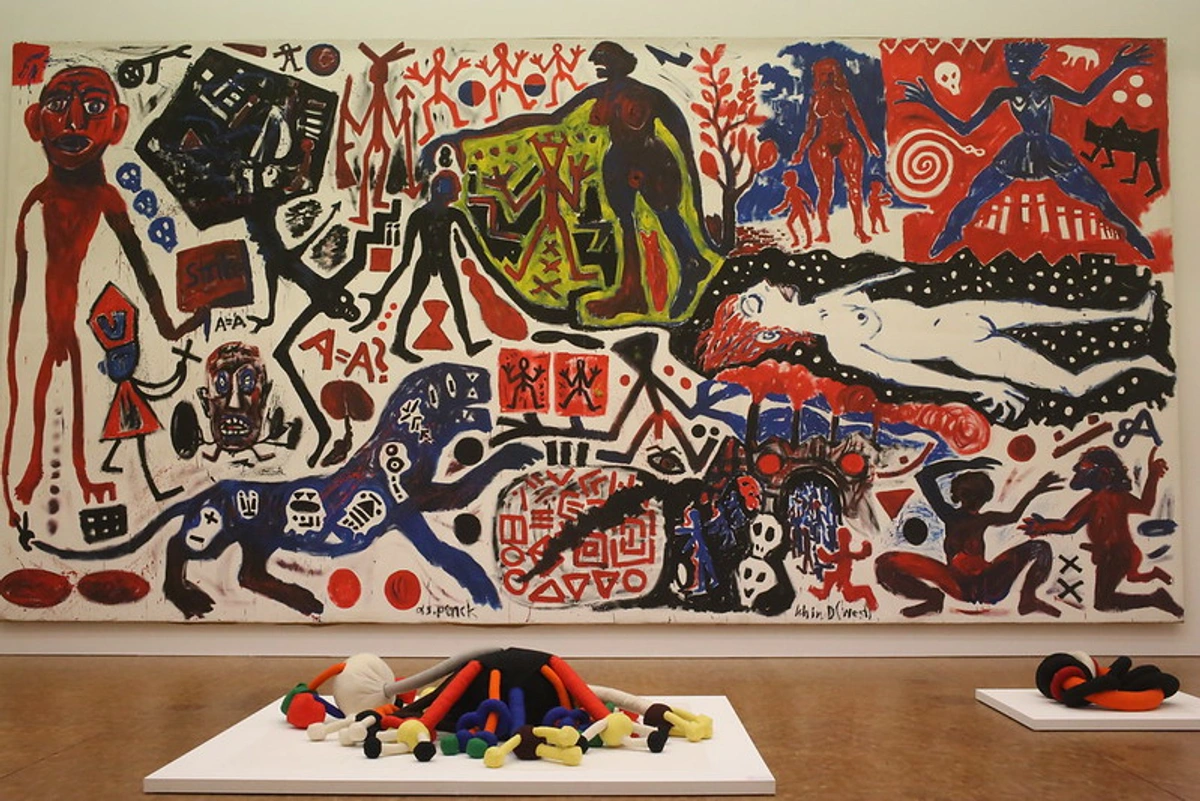

(Image: While not Baselitz, this painting by fellow German Neo-Expressionist A.R. Penck shares a similar raw energy and focus on expressive figuration, often seen in Baselitz's work.)

Key Themes and Motifs: History, Heroes, and Hewn Wood

Beyond the inversion, Baselitz's work is rich with recurring themes and motifs, deeply rooted in his German identity and post-war experience:

- The Helden (Heroes) / Neue Typen (New Types): Painted before the inversion (mid-1960s), these are powerful, often fragmented figures standing awkwardly in desolate landscapes. Works like Die großen Freunde (The Great Friends, 1965) or Der Hirte (The Shepherd, 1966) depict these figures not as triumphant heroes, but as broken, vulnerable individuals grappling with the aftermath of war and a fractured national identity. They are often heavy, almost clumsy figures, sometimes depicted with large, expressive hands, heavy boots, or tattered, ill-fitting clothes, standing rooted yet vulnerable in their ruined world. They seem to embody the struggle of a generation trying to find its footing in a ruined world. Artists like Anselm Kiefer would later explore similar themes of German history and myth.

- Eagles, Trees, Dogs, Figures: These motifs appear again and again, often rendered with aggressive, almost violent energy. The eagle, a symbol laden with German historical weight, is frequently depicted upside down, perhaps stripping it of its nationalistic connotations or presenting it in a state of vulnerability or fall. He takes the eagle, a symbol often associated with national pride or power, and flips it, presenting it not soaring, but grounded, vulnerable, perhaps even fallen – a direct challenge to traditional symbolism. Trees become gnarled, powerful forms, often appearing in fractured or desolate landscapes. Figures, whether self-portraits or others, are rendered with a raw, sometimes brutal physicality.

- Self-Portraits: Baselitz frequently turns his gaze upon himself, always inverted, always exploring the act of painting through his own image. These self-portraits, like the Elke series depicting his wife, become vehicles for formal experimentation as much as personal reflection.

- Confronting Art History: He often engages in dialogue with artists of the past, referencing figures like Edvard Munch or the German Expressionists, twisting their motifs into his own inverted language. This isn't mere imitation but a forceful reinterpretation, pulling historical forms into his contemporary, often unsettling, vision.

Beyond the Canvas: Sculpture and Printmaking

Baselitz isn't just a painter. He's also a significant sculptor and printmaker. His sculptures, typically carved from large, often massive blocks of wood using chainsaws and axes, possess a raw, primal energy. They are rough-hewn, often painted, and share the same expressive intensity as his paintings. There's a directness and physicality to them that connects back to traditional German woodcarving, yet feels utterly contemporary. The process itself, involving aggressive cutting and shaping, mirrors the forceful nature of his painting.

(Image: While not a Baselitz, this image shows a monumental sculpture in a gallery setting, hinting at the scale and presence of Baselitz's own raw, often wood-carved sculptures.)

His work in printmaking – particularly woodcuts and etchings – is equally important. These mediums allow for a different kind of mark-making, often emphasizing stark contrasts and linear energy. Exploring different mediums is common for artists; understanding the difference between, say, prints and paintings or different types of artwork can enrich your appreciation.

Legacy and Looking at Baselitz Today

So, what's the takeaway? Georg Baselitz is a major force in late 20th and early 21st-century art.

- He revitalized figurative painting in an era dominated by abstraction and conceptualism. This was significant because many artists felt that after the horrors of WWII and the Holocaust, traditional representation was no longer adequate or even morally permissible. Baselitz, however, insisted on bringing the human form and recognizable subjects back, albeit in a fractured, raw, and ultimately inverted way, to confront history and identity.

- He was central to the Neo-Expressionist movement, alongside artists like Anselm Kiefer, A.R. Penck, Markus Lüpertz, and Jörg Immendorff in Germany, and figures like Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat internationally. This movement marked a return to subjective expression, intense emotion, and often large-scale, gestural painting.

- His upside-down strategy remains a powerful statement about perception and the nature of painting, forcing viewers to look beyond narrative and engage with the formal elements.

- His raw, expressive style continues to influence contemporary artists today, particularly those working with figuration and materiality.

- His works command significant prices on the art market and are held in major museum collections worldwide (check out some top museums here).

While his artistic contributions are widely celebrated, it's worth noting that Baselitz has also faced criticism, particularly for controversial public statements. These included remarks perceived as dismissive of female artists, sparking debate about representation and inclusion in the art world. These instances, while separate from the work itself, add another layer to the public persona of an artist who has consistently courted controversy since the beginning of his career.

How should you approach his work?

Looking at a Baselitz painting can feel disorienting at first, and that's okay. That's part of the point. Instead of trying to 'right' the image in your mind or figure out the 'story,' try these approaches:

- Embrace the Disorientation: Acknowledge that it's upside down, and let that initial strangeness pass. Don't fight it.

- Focus on the Paint: This is where the real action is. Look closely at the texture – is it thick and lumpy (impasto)? Can you see the direction of the brushstrokes? What about the colours? How do they interact? Forget the subject for a moment and just see the paint as paint. Learning how to read a painting involves appreciating these formal qualities.

- Feel the Energy: Baselitz's work is often described as raw and energetic. Can you sense that energy in the lines, the colours, the overall composition? It's a visceral experience.

- Consider the Context (After the Initial Viewing): Once you've engaged with the painting on a formal level, then bring in the context. Remember his background, the post-war German setting, the rebellion against existing art forms. How does knowing the subject (a portrait, a landscape) change your perception after you've looked at the paint?

- Allow Yourself to Be Challenged: Baselitz's art isn't always meant to be pretty or easy. It's often confrontational, visceral, even unsettling. Allow yourself to feel whatever it evokes, even if it's discomfort. Sometimes, appreciating art that initially seems 'difficult' is incredibly rewarding. It pushes you to think differently, much like the artist intended. You might even discover something new in the process, perhaps finding art that speaks to you personally.

I remember the first time I tried painting upside down myself, just to see what it felt like. It was surprisingly freeing, but also incredibly difficult to control! It gave me a whole new appreciation for what Baselitz was doing – it's not just a trick, it's a fundamental shift in how you engage with the canvas.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Why did Georg Baselitz paint upside down? A: He started painting upside down in 1969 primarily to shift the viewer's focus away from the subject matter (like a figure or landscape) and towards the formal qualities of the painting itself – the colour, texture, composition, and the act of painting. It was a way to challenge perception and conventional ways of seeing, liberating the painting from its narrative content.

Q: What art movement is Georg Baselitz associated with? A: Georg Baselitz is a key figure in Neo-Expressionism, an art movement that emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s, characterized by intense subjectivity, highly textured brushwork, and a return to figurative painting, often with raw, expressive or distorted forms. He is considered one of the pioneers of German Neo-Expressionism, sometimes referred to as the Neue Wilden (New Wild Ones).

Q: What is Georg Baselitz's most famous work? A: It's difficult to pinpoint a single "most famous" work, as fame can be subjective. However, his early controversial painting "Die große Nacht im Eimer" (The Big Night Down the Drain, 1962/63) is historically significant due to the scandal it caused. His upside-down paintings as a whole are what he is most widely recognized for, with numerous inverted portraits (like the Elke series), landscapes, and eagles being iconic examples. His monumental wood sculptures are also highly regarded.

Q: Is Georg Baselitz still alive? A: Yes, as of late 2023, Georg Baselitz is still alive and actively working.

Q: Where can I see Georg Baselitz's art? A: His work is held in major public and private collections worldwide. You can find his paintings and sculptures in prominent museums such as the Tate Modern (London), MoMA (New York), Centre Pompidou (Paris), Guggenheim Museums, and numerous galleries across Germany like the Pinakothek der Moderne (Munich) and the Albertina (Vienna). Checking the websites of these major international galleries or top museums is a good start.

Q: What materials does Baselitz typically use? A: Baselitz is primarily known for oil painting on canvas. However, he is also a significant sculptor, often working with wood, carving with chainsaws and axes. His printmaking includes etchings and woodcuts.

Conclusion: More Than Just Inverted Images

Georg Baselitz did more than just flip paintings; he flipped perspectives. He forced a reconsideration of how we engage with art, demanding that we look at the painting, not just through it to the subject. His work is raw, powerful, sometimes uncomfortable, but always deeply engaged with the act of creation and the weight of history.

He reminds us that art isn't always about easy answers or pretty pictures. Sometimes, it's about the struggle, the energy, the confrontation. And maybe, just maybe, turning things upside down is exactly what's needed to see them clearly. It’s a bit like life, isn’t it? Sometimes the most confusing or challenging experiences are the ones that teach us the most. Baselitz just put that idea onto canvas, and wood, with unforgettable force. His journey, from expulsion in East Berlin to international acclaim, is a testament to the power of challenging norms and forging one's own path, even if it means viewing the world from a different angle. It makes me think about my own journey as an artist, the moments of doubt and defiance, and the constant search for a unique voice. You can see some of that journey reflected in my artist timeline or the art for sale on this site.