How Japanese Woodblock Prints (Ukiyo-e) Revolutionized Western Art

Dive into how Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e), once packing material, sparked the Japonisme movement, revolutionizing Western art with their bold composition, flat color, and expressive line, influencing masters like Monet, Van Gogh, and the Art Nouveau movement. Discover the visual lessons and lasting legacy.

How Japanese Woodblock Prints Blew the Minds of Western Artists (And Changed Everything)

Okay, let's talk about something that genuinely fascinates me, something that feels like a secret handshake across continents and centuries. You know those beautiful, often vibrant Japanese woodblock prints? The ones with the crisp lines, flat colors, and sometimes totally wild perspectives? Turns out, they didn't just stay in Japan. They traveled, they landed in Europe, and they basically blew the minds of a whole generation of Western artists. And honestly? They changed everything.

I remember the first time I really saw a Japanese print, not just as a pretty picture, but as something fundamentally different. It was a Hokusai, maybe one of his waves – perhaps the iconic Great Wave off Kanagawa. But it wasn't just the image; it was the feeling it evoked. The sheer energy in the line, the way the color was just there, flat and bold, no fussy shading. It felt so... modern, even though it was old. It felt like a visual punch to the gut, in the best possible way. It was like seeing the world through a new lens, one that stripped away the unnecessary and left only the powerful essence. And then I started seeing echoes of it everywhere in Western art from the late 1800s. It was like finding clues in a visual detective story, piecing together this incredible cross-cultural conversation.

This wasn't just a fleeting trend; it was a seismic shift. It helped artists break free from centuries of tradition and look at the world, and the canvas, in entirely new ways. Let's dive into this incredible story of influence, cultural exchange, and how a few pieces of paper packed around porcelain changed the course of art history.

So, What Exactly Are We Talking About? Ukiyo-e Explained (Simply)

So, what were these magical pieces of paper that caused such a stir? The prints that caused all this fuss are called Ukiyo-e, which translates roughly to "pictures of the floating world." Think of them as snapshots of Edo period Japan (roughly 17th to 19th centuries). They depicted the vibrant, transient world of:

- Beautiful courtesans and geisha: Icons of fashion and beauty, famously captured by artists like Utamaro, whose portraits often focused on the delicate lines and patterns of their clothing and hairstyles.

- Kabuki actors: Dramatic portraits capturing their roles and personalities, with Sharaku being a master of this genre, known for his bold, almost caricatured expressions.

- Sumo wrestlers: Celebrating strength and sport.

- Travel scenes and landscapes: Like Hokusai's famous Mount Fuji series or Hiroshige's views of the Tokaido Road, including prints like Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake. These captured the beauty and changing moods of the Japanese landscape.

- Scenes from history and folklore: Telling popular stories.

- Warrior prints (Musha-e): Depicting legendary samurai and historical battles, a genre mastered by artists like Kuniyoshi, known for his dynamic compositions and detailed figures.

- Ghost stories and supernatural themes (Muzan-e): Explored by artists like Yoshitoshi, adding a darker, more dramatic edge to the genre.

They were produced using a woodblock printing technique, which is a whole art form in itself. It was a highly collaborative process, involving distinct roles: an artist would draw the original design, a skilled carver would meticulously carve the design into wooden blocks (often cherry wood, known for its fine grain), one block for each color, plus a key block for the outline. The carving required incredible precision and skill to translate the artist's delicate lines into raised wood surfaces. Then, a printer would apply water-based pigments (which allowed for the characteristic flat, matte color) and press the paper onto the blocks, layer by layer, ensuring perfect registration for each color. Crucially, the publisher (hanmoto) played a central role, commissioning the designs, financing the production, and distributing the final prints. They were the entrepreneurs of the Ukiyo-e world, often dictating subjects and styles based on popular demand. This wasn't like Western etching or lithography, which often involved the artist more directly in the printing; Ukiyo-e was a true team effort, resulting in that characteristic bold outline and distinct areas of flat color. The nature of carving and applying ink to raised surfaces naturally lends itself to clear lines and defined color zones, a stark contrast to the blended tones achievable with paint or other printmaking methods. It's a process that forces a certain graphic clarity, a deliberate simplification that turned out to be revolutionary. It's fascinating to think of the precision needed for each block, the collaborative dance between artist, carver, and printer – a whole story in itself, captured on paper.

These weren't seen as 'high art' in Japan at the time; they were more like popular, mass-produced items, relatively affordable for the general public. This popular status, ironically, made them perfect for traveling the world tucked into crates of more valuable goods like porcelain and silk. Can you imagine unwrapping a precious vase and finding a Hokusai print cushioning it? It sounds like something out of a movie, but it happened. Who knew cheap packaging could change the world? This difference in perceived status between East and West also played a role in how Western artists approached them – less as sacred masterpieces and more as fascinating visual resources to be freely borrowed from. It's a funny thought, isn't it? That something considered almost disposable could hold the keys to unlocking a whole new artistic era.

The Arrival in the West: Japonisme Takes Hold

Fast forward to the mid-19th century. After centuries of relative isolation, Japan began opening up to trade with the West, partly due to events like the arrival of Commodore Perry's fleet in the 1850s. Goods started flowing, and among the porcelain, silks, and other exotic items, were these prints. Often, as we touched on, they were used as cheap packing material! Western artists and collectors, already looking for something new and different, were captivated. This wasn't the perspective-driven, realistic, often historically or religiously themed art they were used to.

This was flat, decorative, focused on everyday moments or dramatic natural scenes rendered with graphic power. It was fresh, it was exciting, and it sparked a craze known as Japonisme. Japonisme wasn't just about prints; it was a broader fascination with all things Japanese – textiles, ceramics, lacquerware, fans, and even garden design – that permeated Western culture and design. Key figures and events were instrumental in this introduction. The 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle is often cited as a pivotal moment, where Japanese art and objects were widely displayed, capturing the attention of artists and the public alike. Early collectors and artists like Félix Bracquemond and James Tissot were among the first to acquire and study these prints, sharing their discoveries within artistic circles. Dealers like Siegfried Bing in Paris became central figures, importing and selling vast quantities of Japanese art and objects, including prints, through his shop, L'Art Nouveau (which, funnily enough, gave the Art Nouveau movement its name). Exhibitions showcased these fascinating new aesthetics. Suddenly, Japanese fans, screens, ceramics, lacquerware, and especially prints, were highly sought after. Artists collected them, studied them, and started incorporating these new visual ideas into their own work. It was like a visual language barrier had been broken, and a flood of new possibilities rushed in, marking a significant transition towards modern art. It must have felt like discovering a secret cheat code for creativity!

What Did They Borrow? Key Visual Lessons Unlocked

So, what were the actual visual secrets they unlocked? What specific elements did Western artists pick up from Ukiyo-e? It wasn't just a general 'Asian' feel; there were concrete visual principles that offered a radical alternative to Western academic traditions. It's like finding a new tool you didn't know existed, and suddenly your whole approach changes.

Let's look at the contrast:

Aspect | Western Academic Tradition | Ukiyo-e Approach | Influence on Western Art |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition & Perspective | Linear perspective, single vanishing point, realistic depth | Flattened space, high horizon lines, diagonal lines, unexpected viewpoints, cropping | Experimentation with composition, dynamic arrangements, high viewpoints, cropped figures, breaking the 'window' illusion. |

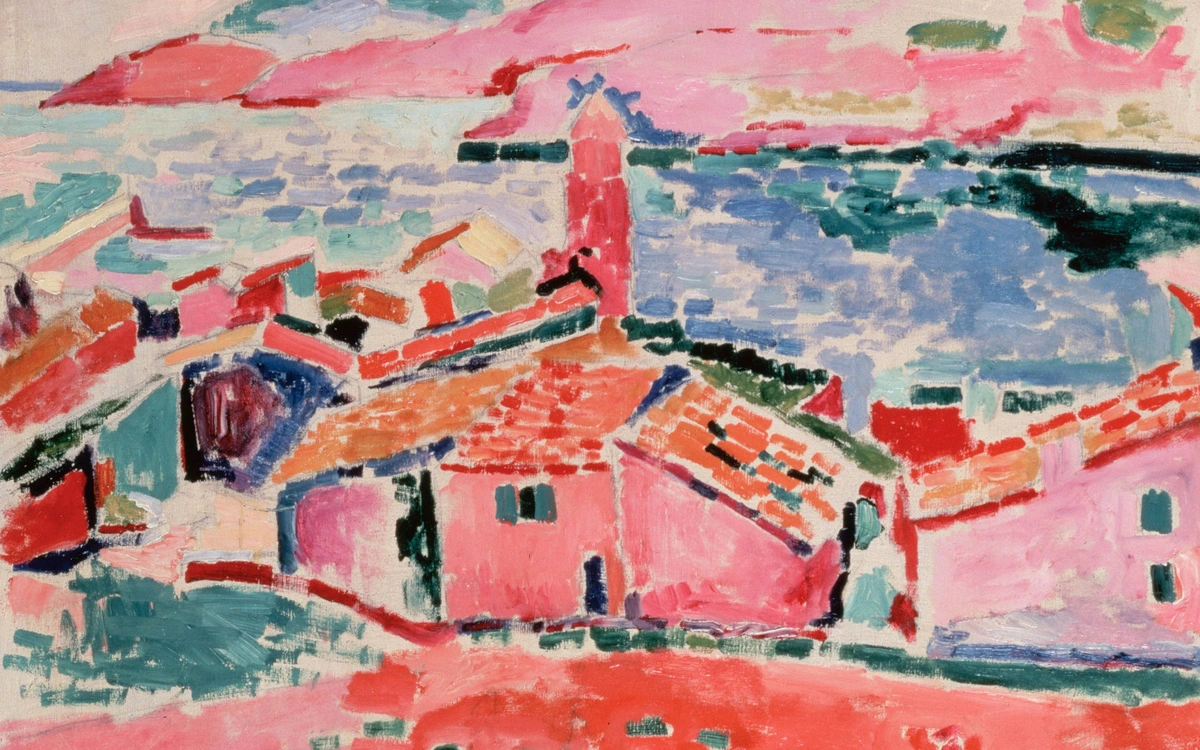

| Color | Subtle shading (chiaroscuro), blended tones, naturalism | Flat areas of vibrant, often non-naturalistic color, bold contrasts, limited palettes | Use of color for emotional/decorative effect, paving way for Fauvism, Expressionism; departure from strict modeling. |

| Line | Minimized visible outlines, blended edges | Strong, clean outlines, line as expressive element, graphic power | Emphasis on line, bold graphic shapes, influence on Art Nouveau, illustration; power of the graphic line itself. |

| Pattern & Decoration | Illusionistic depth prioritized over surface decoration | Embraced decorative patterns, focus on surface beauty | Increased use of pattern, decorative quality of the image surface, influence on Art Nouveau and decorative arts. |

| Asymmetry & Space | Favored symmetry or balanced arrangements, traditional use of negative space | Frequently employed asymmetrical compositions, dynamic use of negative space | New possibilities for arranging elements, visual tension, modern feel, deliberate use of empty space. |

| Subject Matter | Historical, mythological, religious themes, formal portraits | Everyday life, landscapes, portraits of ordinary people, transient world | Validation of contemporary subjects, focus on modern life, landscapes, and informal portraits. |

This table really highlights the fundamental differences. Western art was so focused on creating an illusion of reality, like looking through a window. Ukiyo-e offered a different way to build an image, one that was more about the flat surface, the power of line and color as design elements, and capturing the essence rather than perfect mimesis. It's like the Japanese prints gave them permission to break the rules of the picture frame and explore the canvas as a flat plane for dynamic arrangement.

Let's dig into a few of these key lessons:

Composition and Perspective: Western artists were bound by linear perspective, creating a sense of deep, realistic space. Ukiyo-e artists, however, freely used flattened space, high horizon lines that push the background forward, strong diagonal lines for dynamism, and unexpected viewpoints (like looking down from above or up from below). They also weren't afraid to crop figures or objects dramatically at the edge of the frame, creating a sense of immediacy and suggesting the scene extends beyond the canvas. This directly influenced Impressionists like Degas, who used high viewpoints in his ballet dancers, and Post-Impressionists seeking new ways to structure their images. It broke the illusionistic 'window' and made artists think about the picture plane as a surface for design. I remember struggling with creating depth early in my own artistic journey, feeling constrained by traditional perspective rules. Seeing how Ukiyo-e artists flattened space and used bold diagonals was incredibly liberating – it showed me there were other ways to guide the viewer's eye and create visual interest without relying on realism. It felt like a weight lifted, a permission to play with space in a way that felt more intuitive and expressive.

Color: The Ukiyo-e approach to color was a revelation. Instead of subtle shading (chiaroscuro) and blended tones to create volume and realism, Japanese prints used flat, unmodulated areas of vibrant, often non-naturalistic color. This wasn't just a technical limitation of the woodblock process; it was a deliberate aesthetic choice that allowed color to function decoratively and expressively, independent of realistic light and shadow. For artists like Matisse, this opened up a whole new world – using color for its emotional impact, its vibration, its pure visual joy, rather than just to describe the world accurately. This focus on color relationships and harmonies, independent of realistic light and shadow, paved the way for movements like Fauvism and Expressionism. As an artist myself, the idea of using color purely for its emotional or visual punch, rather than just to mimic reality, is incredibly liberating – a lesson I definitely see echoed from Ukiyo-e and one I constantly explore in my own work. (Learn more about how artists use color).

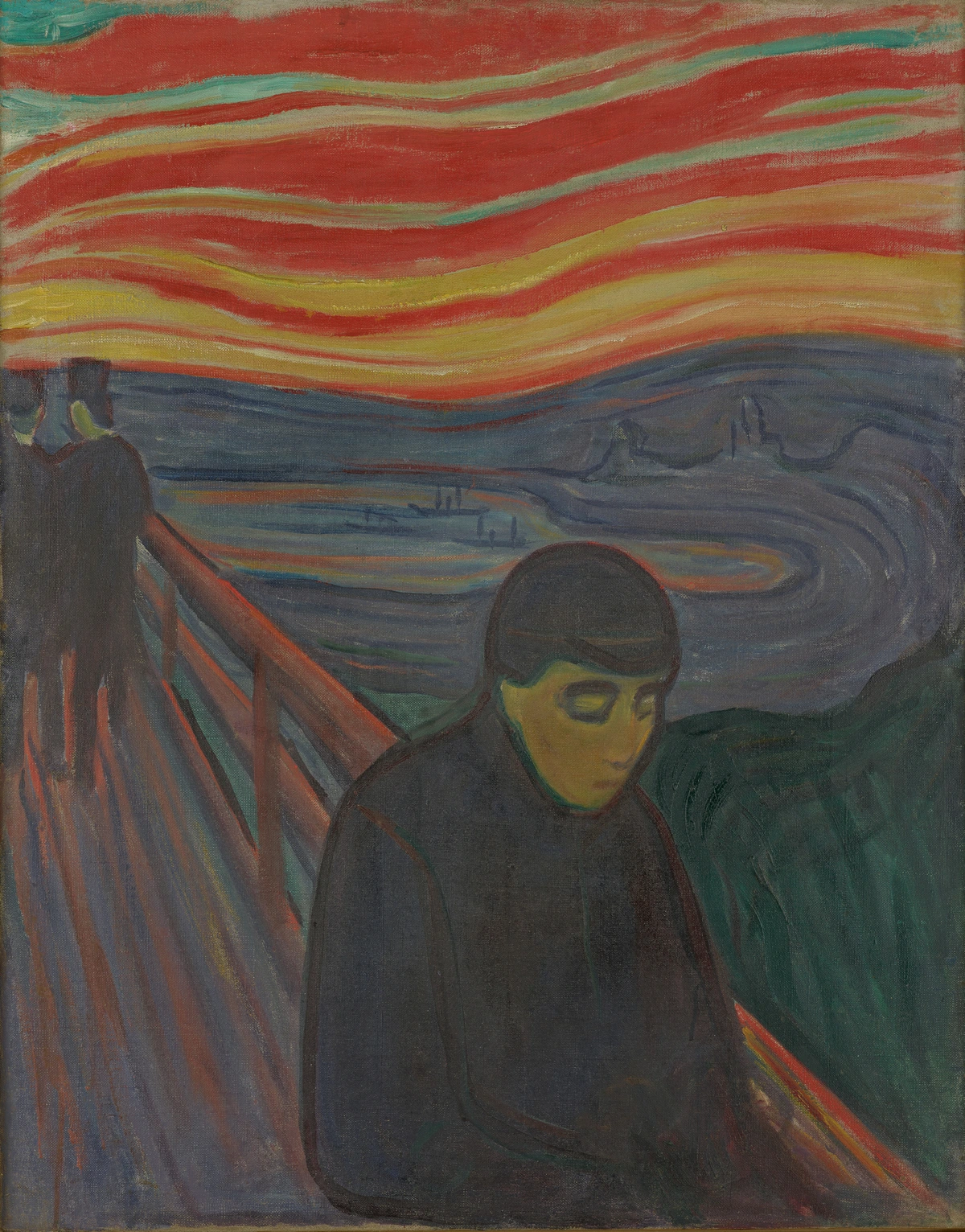

Line: Western academic art often minimized visible outlines, preferring blended edges. Ukiyo-e celebrated the line. The bold, graphic outlines were essential to the design, defining forms with clarity and energy. This emphasis on line as a descriptive and expressive element influenced artists like Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec, and became a key feature in Art Nouveau and later styles. It's about the power of the graphic line itself, not just as a boundary. The bold, graphic shapes created by these lines, and the deliberate use of negative space (the empty areas around and between subjects) to enhance composition, were also key lessons adopted in Western design and illustration. The thoughtful use of negative space, often asymmetrical, creates visual tension and directs the viewer's eye in unexpected ways. I find myself constantly thinking about the power of a simple, strong line and the impact of empty space in my own work – it's amazing how much energy they can hold. (Explore the role of negative space).

Pattern and Decoration: Unlike Western art which often prioritized creating an illusion of depth over surface decoration, Ukiyo-e prints reveled in decorative patterns. The intricate designs of kimonos, the textures of water or wood, and stylized natural forms were celebrated for their inherent beauty. This embrace of pattern and the decorative quality of the image surface was hugely influential on Art Nouveau and the decorative arts, validating the idea that beauty and design could be primary goals, not secondary to realistic representation.

Asymmetry and Space: Western compositions often aimed for symmetry or a clear, balanced arrangement. Ukiyo-e frequently employed asymmetry, placing the main subject off-center, using strong diagonals, and utilizing negative space dynamically. This created a sense of movement, spontaneity, and visual tension that felt incredibly modern and offered Western artists new ways to arrange elements on the canvas, breaking away from static, formal compositions. The deliberate and often asymmetrical use of empty space was particularly revolutionary, allowing elements to breathe and guiding the eye in unexpected, dynamic ways.

Subject Matter: While Western academic art focused on grand historical, mythological, or religious narratives and formal portraits of the elite, Ukiyo-e depicted the everyday life of the Edo period – courtesans, actors, sumo wrestlers, travelers, and landscapes. This validated contemporary, ordinary subjects as worthy of artistic attention, aligning perfectly with the goals of movements like Impressionism, which sought to capture modern life and fleeting moments.

The Artists Who Fell Under the Spell

So, who were the artists who actually put these lessons into practice? The list of Western artists profoundly influenced by Ukiyo-e reads like a who's who of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They weren't just copying; they were learning from the Japanese masters and integrating those lessons into their unique styles. This period marks a significant transition towards modern art.

- The Impressionists: Think Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro. They were fascinated by the Japanese focus on capturing fleeting moments, everyday life, and landscapes. They adopted the idea of unusual viewpoints, asymmetrical compositions, and cropping figures or objects at the edge of the frame, just like you'd see in a print. Look at Monet's series of the Japanese Footbridge in his Giverny garden, directly inspired by his collection of prints, or how his Haystacks series explores the changing light and atmosphere, echoing the Japanese masters' dedication to capturing nature's transient beauty. It's said that Monet was particularly struck by Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji and Hiroshige's Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, finding inspiration for his own landscape series in their approach to capturing the same subject under different conditions. Seeing how Monet used that high horizon line or cropped a scene feels like he's inviting you to step into the moment, just like those prints do. Degas's depictions of dancers and bathers often use high viewpoints and cut-off figures reminiscent of Ukiyo-e composition, creating a sense of candid, unposed reality. Consider his famous pastel "The Tub" (1886), where the high angle and cropped figure of the bathing woman feel distinctly influenced by the unexpected perspectives found in Japanese prints.

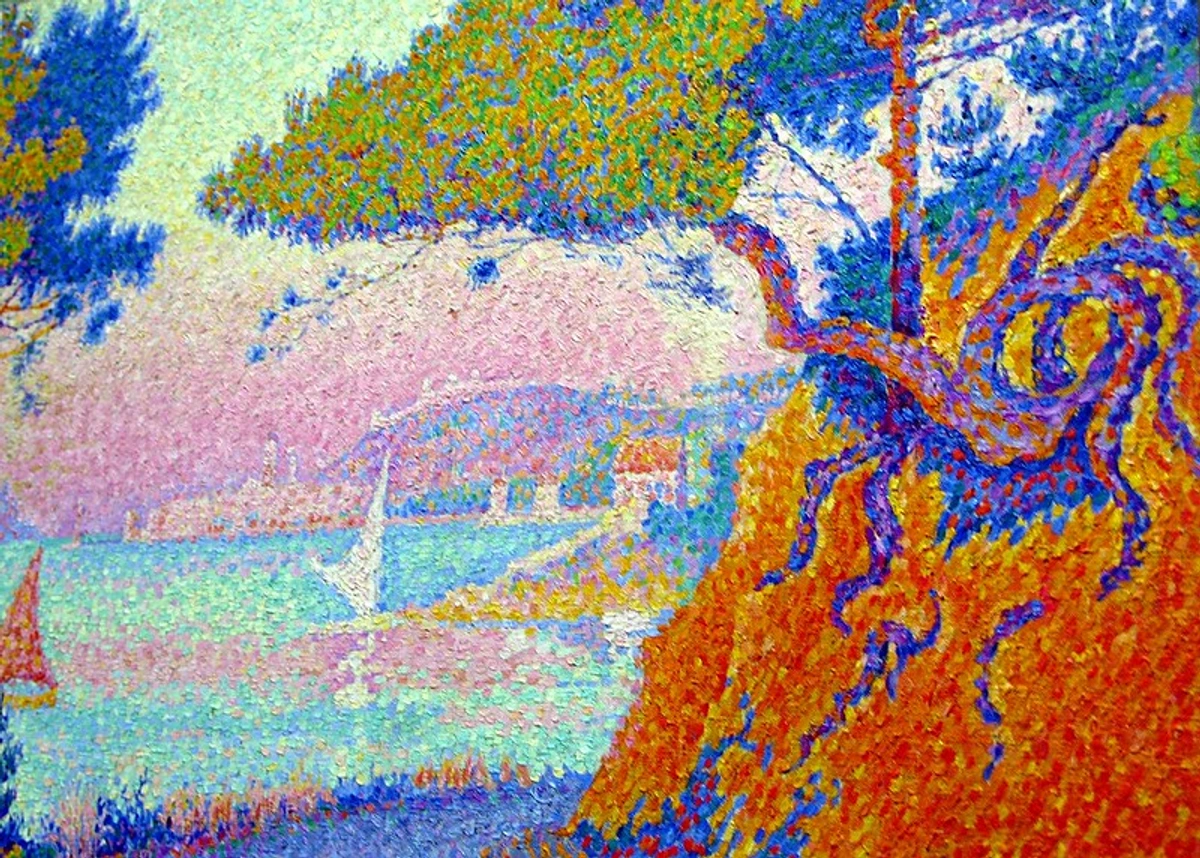

- The Post-Impressionists: Vincent van Gogh was perhaps the most vocal admirer. He collected hundreds of prints (some say over 400!) and even painted copies of them, like his versions of Hiroshige's "Bridge in the Rain" and "Flowering Plum Tree" (both from Hiroshige's One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series). You can see the influence in his bold outlines, flat areas of intense color, and expressive lines, particularly in works like "Starry Night Over the Rhône" or his portrait of Père Tanguy, where Japanese prints are visible in the background. The graphic power and emotional intensity of Ukiyo-e line and color deeply resonated with his expressive goals. Think about the swirling, dynamic lines in "The Starry Night" (1889) or the intense, non-local colors in "The Night Cafe" (1888) – these show a clear departure from traditional Western modeling, embracing the expressive potential of line and flat color blocks seen in Ukiyo-e. Van Gogh's lines feel like they're vibrating with the same energy I see in a Hokusai wave – pure, uncontained emotion. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was also heavily influenced, particularly by the focus on urban life, portraits, and dynamic compositions seen in actor prints by artists like Sharaku, evident in his famous posters with their strong lines and flat color blocks, designed to grab attention with graphic impact. Paul Gauguin, too, was part of this broader search for non-Western inspiration, finding in Japanese prints (among other sources) a validation for moving beyond European naturalism towards more symbolic and decorative forms.

- Art Nouveau: This decorative style, popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, owes a huge debt to Japanese art. The flowing, organic lines, decorative patterns, asymmetry, and emphasis on nature are all hallmarks of Ukiyo-e influence. Think of the work of artists like Aubrey Beardsley or Gustav Klimt, where decorative patterns and sinuous lines dominate, or the architectural designs and posters of the era. The bold, graphic quality and use of negative space in prints were particularly influential here. The way natural forms are stylized and flattened in Art Nouveau posters and illustrations directly echoes the approach in Ukiyo-e. Beyond prints, the influence of Japanese textiles and ceramics with their intricate patterns and organic forms was also significant for Art Nouveau designers. It's like Art Nouveau artists took the elegant lines and decorative flair of Ukiyo-e and turned the volume up to eleven.

- Other Notable Artists: James McNeill Whistler incorporated Japanese motifs and compositional ideas, notably in his "Peacock Room." Mary Cassatt, an American Impressionist working in Paris, was particularly inspired by prints depicting women and children, adopting their flattened perspective and intimate domestic scenes in her series of drypoint prints, often drawing parallels to the work of Utamaro. Even artists like Claude Debussy in music and the Symbolist poets were touched by the aesthetic and philosophical ideas associated with Japonisme.

This period, often called the transition to modern art, was a melting pot of ideas, and Japanese prints were a crucial ingredient.

Why Did It Resonate So Much?

But why these prints, and why then? The timing was perfect. Western art was at a crossroads. The advent of photography in the mid-19th century fundamentally challenged the need for painting to be purely representational. If a camera could capture reality with perfect accuracy, what was the painter's role? Academic traditions felt stale to many, bound by rigid rules of perspective, anatomy, and historical subjects. Artists were seeking new ways to express modernity, emotion, and subjective experience, moving beyond strict mimesis (the imitation of reality).

Ukiyo-e offered a completely different paradigm. It wasn't about perfect anatomical accuracy or illusionistic depth. It was about capturing the essence of a scene or person with graphic strength and decorative beauty. Its focus on line, flat color, and dynamic composition provided a ready-made visual language for artists looking to break free from the constraints of realism and academic rules. This resonated deeply with artists who wanted to explore the expressive potential of color, line, and form for their own sake, rather than solely in service of representation.

It was a breath of fresh air, a permission slip to break the rules and see the world through a different lens. And that, I think, is something every artist, or anyone creative, can relate to – the constant search for new ways to see and express. It reminds me of my own journey, constantly seeking new perspectives and techniques, sometimes finding them in the most unlikely historical corners. (See my timeline if you're curious about that journey.)

Interestingly, while Ukiyo-e was revolutionizing art in the West, its status in Japan began to decline during the Meiji era (1868-1912). As Japan rapidly modernized and sought to present itself as a modern nation on the world stage, there was a conscious effort to adopt Western technologies and cultural forms, including Western art styles. Ukiyo-e, associated with the Edo period and seen by some as old-fashioned or merely popular entertainment, fell out of favor domestically. Western painting techniques and subjects became fashionable, creating a fascinating, almost ironic, contrast with the simultaneous embrace of Ukiyo-e aesthetics in Europe and America. It's a strange twist of fate, isn't it? That something discarded at home could become the key to unlocking a revolution abroad.

The Lasting Legacy

The influence of Japanese woodblock prints wasn't just a passing phase. It fundamentally altered the trajectory of Western art. It contributed significantly to the development of modern art movements like Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Art Nouveau. It opened up new possibilities for composition, color theory, and the use of line. While Ukiyo-e was the primary driver, other Japanese art forms like textiles, ceramics, and lacquerware also contributed to the broader Japonisme aesthetic that permeated Western design, influencing everything from furniture to jewelry.

Even today, you can see echoes of Ukiyo-e in various forms of art and design, from illustration to graphic novels. Think of the dynamic panel layouts, bold character outlines, expressive use of flat color, and deliberate use of negative space in manga and graphic novels – these techniques owe a clear debt to the visual language perfected by Ukiyo-e masters centuries ago. The idea of using bold outlines, flat color, dynamic composition, and thoughtful use of negative space feels incredibly contemporary, a testament to the timeless power of those Edo-period snapshots.

It's a beautiful reminder that inspiration knows no borders, and sometimes, the most revolutionary ideas arrive unexpectedly, perhaps even tucked away as packing material. It makes you wonder what other hidden influences are waiting to be discovered, doesn't it? Maybe even in the art you encounter today. (Explore some contemporary art and see what resonates.) Or perhaps you'll find a piece that feels like it carries a whisper of that Edo-period revolution, right here in my own collection. It's a constant process of looking, learning, and letting unexpected visual conversations shape your own creative path, much like those Western artists did when they first encountered the magic of Ukiyo-e. It's a legacy that continues to inspire, proving that sometimes, the most profound shifts come from the most unexpected places.