Modern Art History: An Artist's Personal, Engaging Guide to the Revolution

Dive into the history of modern art through an artist's personal lens. Explore the revolutionary movements, key figures, and the social shifts that sparked innovation from Impressionism to Abstract Expressionism, and discover why it still matters today. Includes insights on collecting and museums.

The Wild Ride: My Personal Journey Through the History of Modern Art

Okay, let's talk about modern art. For a long time, I admit, it felt like a bit of a puzzle. Like walking into a room where everyone was speaking a language I hadn't quite mastered yet. You know that feeling? Standing in front of a canvas that's just... blocks of color, or maybe some squiggly lines, and thinking, "This is famous? Why?" If you've ever felt that, trust me, you're not alone. But diving into the history of modern art? That's where the magic happens. It's not just a list of dates and names; it's a story of rebellion, innovation, and artists trying to make sense of a world that was changing faster than anyone could keep up. It's a journey that feels deeply personal to me, like uncovering the roots of my own artistic language. It's the DNA of contemporary art, really.

Think of it as a grand, slightly chaotic family tree, starting roughly in the late 19th century and shaking things up well into the mid-20th. It's the era where art decided it didn't just have to look like the world, it could feel like it, question it, or even just be itself. It's a history that's deeply personal to me as an artist, because it's the foundation of so much of what we see and create today. If you're curious about the bigger picture, my History of Art Guide might be a good starting point, but let's focus on the modern revolution.

The Spark: Breaking Away from the Rules

Before modern art, things were... well, pretty structured. Art was often about depicting reality as accurately as possible, telling stories, or serving religious/political purposes. Think grand historical paintings or detailed portraits. This was the era of Academic art and movements like Realism, where artists like Gustave Courbet focused on depicting everyday life without idealization, or the Barbizon School painters who took their easels outdoors but still aimed for naturalism. It was skilled, often beautiful, but it largely adhered to established rules. It was art that knew its place, depicting the world as it was expected to be seen.

Interestingly, even before the full break, movements like Romanticism (roughly late 18th to mid-19th century) started chipping away at the strict rules, emphasizing individual emotion, imagination, and the sublime in nature. While still often traditional in form, this focus on subjective experience set a subtle stage for the intense personal expression we'd see later. It was like the first cracks appearing in the dam of tradition.

Then came the late 19th century, and everything started to shift. The world was industrializing, cities were growing, and photography arrived, suddenly doing the job of realistic depiction much faster and cheaper than a painter ever could. This wasn't just a technical shift; photography also changed how artists saw. It offered new perspectives, captured fleeting moments, and even influenced composition and cropping. Suddenly, the artist wasn't just a recorder of visible reality; they had to find a new purpose.

But it wasn't just technology; society itself was changing, with new scientific discoveries (like understanding color and light differently, thanks to figures like Michel Eugène Chevreul, whose work directly influenced the Impressionists and Pointillists) and philosophical ideas challenging old ways of thinking. Think of the seismic shifts brought by Charles Darwin's theories on evolution, Friedrich Nietzsche's questioning of traditional morality (which you can definitely see echoing in the rebellious spirit of Dada and the raw emotion of Expressionism), or the burgeoning field of psychoanalysis pioneered by Sigmund Freud (whose exploration of the subconscious would become the bedrock for Surrealism). These ideas filtered into the collective consciousness, suggesting that reality wasn't as fixed or rational as previously believed, and that the inner world was just as complex and worthy of exploration as the outer one. Artists had to ask themselves: what is art for now? What is the meaning of art? It was a perfect storm of change, demanding a new kind of art.

Impressionism: Chasing the Light

This is often seen as the unofficial start. Instead of painting detailed scenes in a studio, artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas went outside. They tried to capture the fleeting moment, the effect of light and color right now. It wasn't about perfect form; it was about the impression. Think of Monet's famous Impression, soleil levant – it's less about the boats and more about the hazy, atmospheric light. I remember trying to paint outside once – the light changes every five minutes! It gives you a whole new appreciation for what they were doing. It was radical then, focusing on subjective perception and the transient nature of modern life, and it paved the way for so much more. If you want to dive deeper, check out my Ultimate Guide to Impressionism.

![]()

What fleeting moment are you trying to capture today?

Post-Impressionism: Structure and Emotion

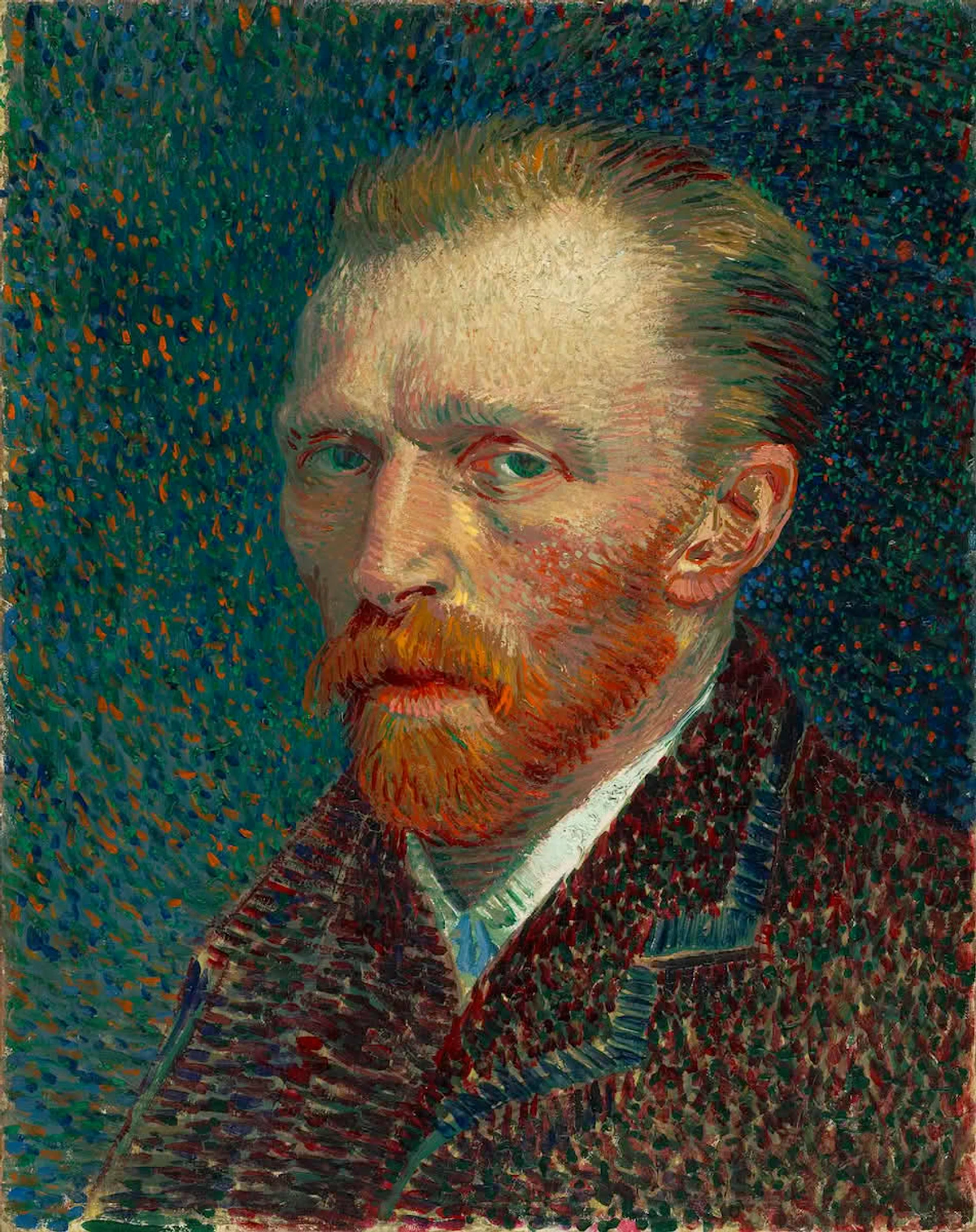

Reacting to Impressionism, but in wildly different ways, came the Post-Impressionists. Artists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Paul Gauguin took the Impressionists' ideas about color and light but added more structure and, crucially, more personal emotion or symbolic meaning. Van Gogh's swirling skies and intense colors weren't just what he saw, but what he felt. His work, like The Starry Night, is a raw, emotional punch, and it resonates so deeply. My guide to Vincent van Gogh explores this more. Cézanne, on the other hand, was obsessed with structure, breaking down forms into geometric shapes and analyzing space in a way that laid the groundwork for Cubism. He sought a more permanent, underlying reality than the fleeting impression. Gauguin moved towards symbolism and the expressive use of color, seeking deeper meaning beyond mere observation, often inspired by non-Western cultures. Georges Seurat brought a scientific approach with Pointillism, using tiny dots of color to build up an image, like in A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. It's fascinating how these artists reacted to Impressionism in such different ways – some seeking order, others seeking deeper feeling or meaning. It's a reminder that artistic progress isn't linear; it's a complex conversation, a branching path rather than a straight line.

How does art make you feel?

The Revolution Explodes: Early 20th Century Chaos

The turn of the century was like an artistic explosion. Artists were questioning everything. What is color? What is form? What is reality? New movements popped up, each pushing boundaries further, often influenced by the rapid technological advancements and the growing awareness of diverse global cultures (though sometimes through problematic colonial lenses – something modern art history grapples with). Meanwhile, movements like Art Nouveau were exploring organic forms and decorative styles, showing just how diverse the artistic landscape was becoming.

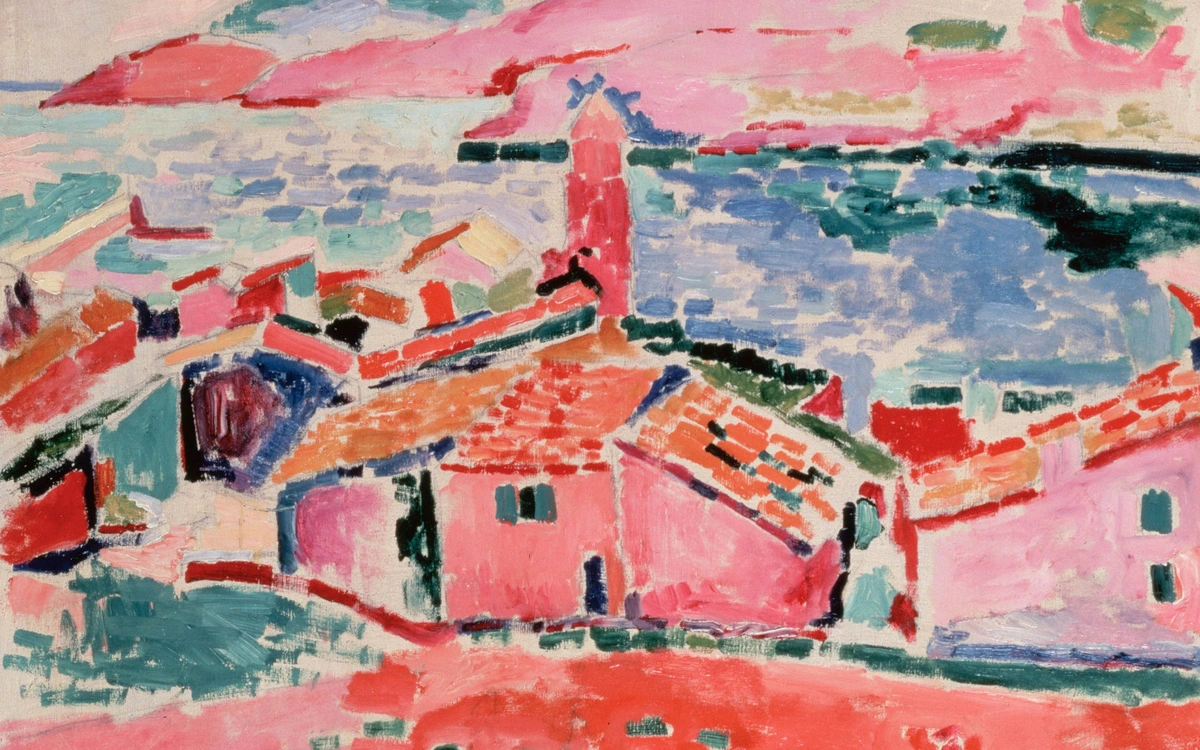

Fauvism: Unleashing Wild Color

What happens when color breaks free from reality? Henri Matisse and the Fauvists decided color didn't have to match the visible world at all. They used vibrant, non-naturalistic colors to express feeling and create harmony. Think bright reds for trees or electric blues for faces, like in Matisse's Woman with a Hat. It was shocking! Like turning the saturation way up on the world, or maybe seeing the world through the eyes of a slightly mad genius. It felt incredibly liberating when I first saw how they used color so boldly, purely for its emotional impact. My Ultimate Guide to Fauvism dives into this colorful rebellion.

Ready to see the world in electric blue?

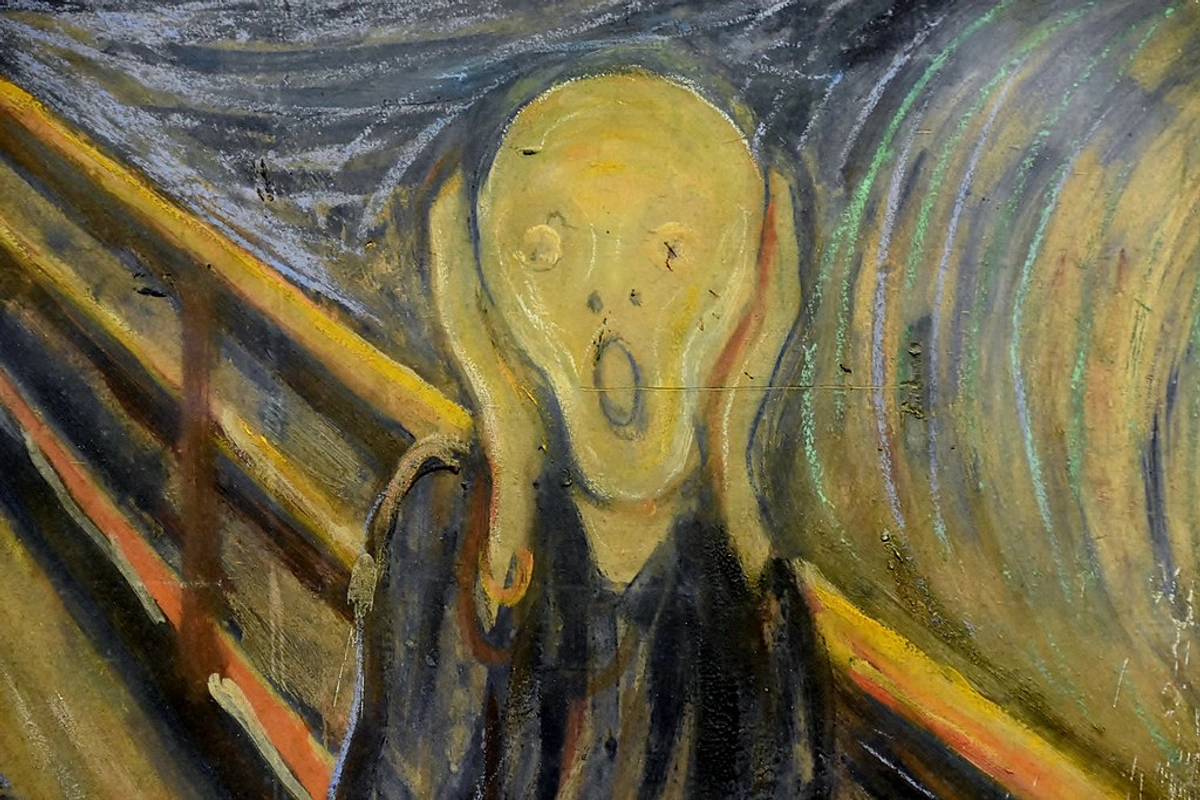

Expressionism: Art from the Gut

Meanwhile, in Germany and elsewhere, Expressionists like Edvard Munch, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Franz Marc were focused on conveying intense emotion and psychological states. Reality was distorted to show inner turmoil or feeling, often reflecting the anxieties of the rapidly changing, pre-war world. The Scream by Munch is the most famous example – that swirling, anxious landscape isn't just a place; it's a feeling made visible. Expressionism is art that feels deeply, often raw and unsettling. It's art that screams back at the world, a direct response to the emotional weight of modernity. I remember seeing The Scream for the first time and feeling a jolt of recognition – that raw anxiety felt incredibly human.

What does your inner world look like?

Cubism: Shattering Reality

Ready to have your mind bent? Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque looked at objects and broke them down into geometric forms, showing multiple viewpoints at once. It's like looking at something from the front, side, and top all at once, then reassembling the pieces on a flat surface. Think of Picasso's revolutionary Les Demoiselles d'Avignon or portraits by Juan Gris. It fundamentally changed how artists thought about depicting space and form, influenced partly by Cézanne's structural analysis and the geometric forms seen in African and Iberian sculpture. It felt like a visual puzzle, challenging everything I thought I knew about drawing and perspective. My Personal Guide to Shattering Reality (Cubism) explains this mind-bending movement.

Can you see the world from every angle at once?

Dadaism: Art of the Absurd

Born out of the horrors of World War I, Dada wasn't really an art style as much as an anti-art movement. Artists like Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Höch, and Tristan Tzara were so disillusioned with the society that led to such destruction that they rejected logic, reason, and traditional aesthetics. They made art out of readymades (everyday objects presented as art – yes, like a urinal, famously Duchamp's Fountain), collage, and nonsense. A readymade, just to be clear, is simply an existing manufactured object that an artist chooses and presents as art, challenging the very definition of what art can be. It was chaotic, nonsensical, and deliberately provocative. It's like they were saying, "If the world is crazy, why should art make sense? Let's just break things." Dada was short-lived but hugely influential, especially on Surrealism, proving that the idea behind the art could be more important than its execution.

![]()

Does art always have to make sense?

Other Radical Paths

The early 20th century was truly a melting pot of radical ideas. Futurism in Italy, led by figures like Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (its founder) and artists like Umberto Boccioni, celebrated speed, technology, cars, and violence, seeking to break free from the past and embrace the dynamism of modern life. Constructivism in Russia, with artists like Kazimir Malevich (who also founded Suprematism) and El Lissitzky, focused on geometric abstraction for social and political purposes, aiming to build a new society through art and design, seeing art as a tool for social change. The Bauhaus school in Germany, founded by Walter Gropius with key figures like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, aimed to integrate art, craft, and technology, applying artistic principles to industrial design and architecture, believing good design could improve society. These movements, though diverse, shared a common thread: a desire to break with tradition, engage with the modern world (whether celebrating it or critiquing it), and explore new forms and functions for art. They pushed the boundaries of what art could be, setting the stage for even more abstraction and conceptual approaches.

How does art intersect with technology and society today?

Between the Wars: Dreams, Logic, and Pure Form

The period between World War I and World War II saw artists grappling with the trauma of war and the rapid changes in society. Some turned inward, others sought universal order. It was a time of introspection and radical new ways of seeing, heavily influenced by the ongoing developments in psychology and physics. Think about how Einstein's theories of relativity, which challenged our understanding of fixed perspectives and reality, provided a scientific parallel to the artistic dismantling of traditional space and form seen in movements like Cubism and abstraction. The world wasn't as solid as it seemed, and neither was the canvas.

Surrealism: Tapping the Subconscious

Inspired heavily by Sigmund Freud's theories on the subconscious mind and dreams, Surrealists like Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, and Yves Tanguy explored dreams, the subconscious, and irrational juxtapositions. Think melting clocks (The Persistence of Memory by Dalí), strange creatures, and impossible landscapes. It's art that feels like a dream – sometimes beautiful, sometimes unsettling, always intriguing. It aimed to unlock the creative potential of the unconscious mind, believing it held a deeper truth than conscious reality. It's the kind of art that makes you ask, "What was the artist thinking?" (Probably not thinking, just feeling or dreaming). I remember seeing a Magritte for the first time and just feeling utterly disoriented, in the best possible way. It forces you to question your own perception.

What strange landscapes populate your dreams?

The Rise of Abstraction

While some explored dreams, others stripped art down to its core elements: line, shape, and color. Artists like Piet Mondrian (De Stijl) sought universal harmony through pure geometric abstraction, using only primary colors and straight lines, as seen in his Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow. Kazimir Malevich, founder of Suprematism, also pursued pure geometric abstraction, aiming for spiritual purity through simple forms like squares and circles (his Black Square is iconic). Wassily Kandinsky, often credited with creating the first purely abstract painting, believed colors and forms could evoke spiritual and emotional responses, like music. His approach was more intuitive and expressive, like in Composition VIII. And then there's Paul Klee, whose abstract work, while sometimes geometric, often felt more whimsical and deeply connected to nature and the subconscious, like little visual poems. It's art that doesn't represent anything from the visible world, but aims to communicate directly with your feelings. It's a leap of faith for both artist and viewer, asking you to feel rather than recognize. Think of it like listening to instrumental music – it doesn't show you a story, but it makes you feel one. If you're curious about this, my History of Abstract Art is a good starting point.

Can you feel the color?

Sculpture and Photography Find Their Modern Voice

While painting often dominates the narrative, sculpture and photography also underwent radical transformations in the modern era, often in parallel with these painting movements. Sculptors like Auguste Rodin, though starting in the academic tradition, pushed towards more expressive, less idealized forms in the late 19th century, influencing later artists. Constantin Brancusi pioneered modern abstract sculpture in the early 20th century, simplifying forms to their essence, seeking purity and timelessness in materials like marble and bronze (think Bird in Space), aligning with the move towards abstraction in painting. Photography, initially seen as a purely documentary tool, was championed as a fine art medium by figures like Alfred Stieglitz in the early 20th century, who opened galleries to exhibit photographic works alongside paintings, arguing for its artistic merit. Man Ray, associated with Dada and Surrealism, experimented with techniques like rayographs (photograms) and solarization between the wars, using photography to explore abstract and dreamlike imagery, mirroring the Surrealist painters' interests. These artists in other mediums were just as vital in challenging traditional notions of art and pushing towards abstraction and conceptual approaches.

How do different mediums change the message?

Post-War Shift: New York Takes the Stage

After World War II, the art world's center shifted dramatically from Paris to New York. Why? The war itself played a huge role; many European artists fled the conflict, finding refuge and a new creative environment in the US. But it wasn't just that. New York was also emerging as a global economic and cultural powerhouse. There was a growing network of galleries, collectors, and institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) actively promoting the new American art. This era saw the rise of the New York School, dominated by Abstract Expressionism.

Abstract Expressionism: Action and Emotion on a Grand Scale

Artists like Jackson Pollock (action painting, famously dripping paint onto canvases) and Mark Rothko (color field painting, creating large canvases of soft, rectangular color areas) created large-scale works that emphasized the process of creation and the emotional impact of color. Abstract Expressionism is characterized by its non-representational nature, large scale, and focus on the artist's gesture or psyche. Color field painting, specifically, is about large areas of flat color intended to evoke a contemplative or emotional response. Standing in front of a huge Rothko, like his No. 14, 1960, can be a truly immersive, almost spiritual experience. It's not about recognizing a subject; it's about feeling the presence of the color and the artist's gesture. It's art that demands you step in and feel it. I remember feeling completely enveloped by the color in a Rothko chapel – it's a physical experience, not just visual.

What colors move you?

The Bridge to Contemporary Art

The mid-20th century saw reactions to Abstract Expressionism, leading into what we now broadly call Contemporary Art. Movements like Pop Art, with figures like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, brought back recognizable imagery, often from popular culture and advertising, but with a modern, often ironic, twist. Minimalism, with artists like Donald Judd and Agnes Martin, stripped art down even further than abstraction, focusing on simple geometric forms and industrial materials, emphasizing the object itself and the viewer's experience of it in space. These movements, while distinct, built upon the modernists' foundation of challenging norms, exploring new materials and ideas, and redefining the relationship between the artwork, the artist, and the viewer. It's a direct lineage, a conversation across decades, a constant push and pull that continues to evolve today.

What everyday objects could be art?

Why Does It Matter? My Personal Take

So, why bother with all this history? For me, it's about understanding the why. Why did artists stop painting pretty pictures? Because the world wasn't pretty anymore. They were responding to industrialization, war, new ideas about the mind, and the sheer speed of modern life. Modern art is a mirror reflecting the anxieties, hopes, and radical shifts of its time. It's the visual soundtrack to a world in flux.

It taught artists (like me!) that you don't have to be bound by tradition. You can experiment, express your inner world, and challenge perceptions. I remember feeling frustrated trying to paint realistically, feeling like I was just copying. Seeing how artists like the Fauvists used color purely for emotion, or how Cubists dismantled perspective, felt like permission to break free. It was like a lightbulb moment – art could be about ideas and feelings, not just perfect representation. Learning about Abstract Expressionism, for instance, and the focus on gesture and emotion, profoundly influenced how I approach my own canvases, encouraging me to trust my intuition and let the process guide me. I used to struggle with composition, trying to force elements into a traditional structure, but seeing how artists like Mondrian built harmony from simple forms, or how Pollock found order in chaos, helped me loosen up and find my own way. That freedom is the legacy that allows artists today to explore everything from abstract forms to art with words or assemblage art. It's why I feel free to create the kind of colorful, abstract work I do today, work that aims to connect directly through color and form, much like those pioneers intended.

If you've ever looked at a piece of modern art and felt confused or even annoyed, that's okay! It was meant to challenge you. It asks you to look differently, to feel, to think. It's not always easy, and sometimes I still stand in front of a piece and think, "Okay, what am I missing here?" But the reward is a richer way of seeing the world. If you're still wondering, "Is Modern Art Really 'Bad'?", I explore that question too.

Experiencing Modern Art Today

For me, experiencing modern art today is less about ticking off a list of famous works and more about connecting with that revolutionary spirit. It's about visiting the places where these ideas live on and seeing how they continue to influence artists. Many of the world's greatest museums have incredible modern art collections. Places like MoMA in New York, the Tate Modern in London, or the Centre Pompidou in Paris are like time machines for this era, places where I can walk the halls and feel the echoes of those seismic shifts. My guides to the Best Modern Art Museums and Modern Art Galleries can help you plan a visit.

And if you're feeling inspired, you can even bring modern art into your own space. Collecting art, whether it's prints or originals, is a fantastic way to live with the energy and ideas of this period. My guides on How to Buy Modern Art or Where to Buy Art can get you started. Or, you know, you could always check out my own work if you're looking for something contemporary with roots in this incredible history. If you're ever near 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, you could even visit my museum to see how these historical threads weave into contemporary practice.

FAQ: Your Modern Art Questions Answered (Sort Of)

Modern art sparks a lot of questions. Here are a few I hear often:

- What's the difference between modern and contemporary art? Modern art generally refers to the period from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century. Contemporary art is art being made today. Think of it this way: Modern art was revolutionary for its time. Contemporary art is revolutionary for our time (or maybe just trying to pay the bills, who knows?).

- Why is modern art so controversial? Because it challenged everything people thought art should be. It rejected traditional skills, beauty standards, and clear subjects. It asked viewers to engage intellectually and emotionally in new ways, which can be uncomfortable! It still gets people talking, which I think is great. It means it's alive.

- Why does some modern art look so simple? Couldn't a child do that? Ah, the classic question! While some modern art appears simple, it's often the result of complex ideas, a deep understanding of composition and color, and a deliberate choice to strip away complexity. It's not about technical skill in the traditional sense, but about conveying an idea or emotion directly. Think of it like a brilliant chef making a simple dish – the simplicity is the result of mastery, not lack of skill. Or a composer using just a few notes to create a powerful melody. And honestly, if a child could do it, maybe that says something wonderful about the child, not something bad about the art! It's about the why and the context, not just the what.

- What's a "readymade"? A readymade is an ordinary manufactured object that the artist selects and presents as art. Marcel Duchamp is famous for this. It challenges the idea that art must be handmade or traditionally skilled. It's about the artist's choice and the idea behind the object, rather than its craftsmanship.

- Where can I see famous modern art? Major museums worldwide have significant modern art collections. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in NYC, the Tate Modern in London, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and many others are must-visits. Even smaller local galleries often have pieces from this era or works heavily influenced by it.

- Why is modern art in museums and considered valuable? Modern art is in museums because it represents a pivotal shift in human expression and thought. It's considered valuable not just in monetary terms (though the market is a factor), but for its historical significance, its profound influence on all subsequent art, and its ability to challenge perceptions and reflect the complexities of the modern world. It pushed boundaries and redefined what art could be, making it essential to understanding the full scope of art history.

- How did World War II specifically impact the shift of the art world to New York? WWII was a major catalyst. Many leading European artists, critics, and dealers fled the war and Nazi persecution, finding refuge in the United States, particularly New York. This influx of talent and influence, combined with America's growing economic power and institutions like MoMA actively supporting modern art, helped establish New York as the new global center for the art world, overshadowing post-war Paris.

- Are there any key female modern artists I should know? Absolutely! While historical narratives often centered male artists, women were vital to modern movements. Think of Mary Cassatt (Impressionism), Berthe Morisot (Impressionism), Hannah Höch (Dada, known for her photomontages), Georgia O'Keeffe (American Modernism, known for her flowers and landscapes), Frida Kahlo (Surrealism, though her work is deeply personal and transcends easy categorization), and Agnes Martin (Minimalism, though her work also has a spiritual, abstract expressionist quality). Their contributions were significant and continue to gain the recognition they deserve.

The Enduring Legacy

Exploring the history of modern art is like understanding the DNA of so much art that came after. It was a time of incredible bravery, experimentation, and a fierce belief in the power of art to change how we see the world – and ourselves. It taught me that art isn't just about making something look nice; it's about exploring ideas, pushing boundaries, and connecting on a deeper level. It's a history that continues to inspire me every day in my own studio. It's a reminder that the most exciting art often comes from questioning the rules and daring to see things differently. It's like learning the grammar and vocabulary of a new language – the language of modern visual expression. And that's a lesson that's just as relevant today as it was a century ago.