The Bauhaus Effect: How Those Radical Artists Still Shape Your World (And Mine)

Step into the Bauhaus world with me. Discover how this radical movement, born from post-WWI chaos, blended art, craft, and life, shaping everything from architecture to the objects you use daily. It's more personal and pervasive than you think.

The Bauhaus Effect: How Those Radical Artists Still Shape Your World (And Mine)

Okay, let's be honest. When you hear "Bauhaus," maybe your eyes glaze over a little? You picture stark, minimalist buildings, maybe some geometric furniture, and think, "Yeah, okay, important history stuff." But as an artist who spends way too much time thinking about how things look and feel, I'm here to tell you that the Bauhaus wasn't just history. It was a revolution, born from a chaotic time, and the artists who were part of it? Their fingerprints are everywhere. Seriously, look around you. That clean font on your screen, the functional design of your coffee mug, the very idea that art and everyday objects aren't separate things – that's the Bauhaus talking. I remember walking into a friend's new apartment, all clean lines and functional furniture, and initially just appreciating the calm. Then, I noticed a simple, elegant lamp, and they mentioned it was 'Bauhaus-inspired'. Suddenly, the abstract concept clicked into place – this wasn't just a historical movement; it was a living, breathing influence on the objects I interacted with daily. It felt like discovering a secret language spoken by the objects and spaces we inhabit. And once you start to understand it, the world gets a little more interesting. It makes you wonder, how did a school that only lasted 14 years leave such a massive footprint? Let's dive in, shall we? Not like a dry history lesson, but more like a chat over coffee about some seriously cool, slightly rebellious folks who changed everything.

So, What Was This Bauhaus Thing Anyway? The Revolution Begins

Imagine Germany after World War I. Things were a bit... chaotic. The old world felt broken, and there was a real, urgent desire to rebuild, not just physically, but culturally and spiritually. The political climate of the Weimar Republic was volatile, marked by economic hardship, social unrest, and the rise of extremist ideologies, creating a fertile ground for radical ideas and a yearning for a new beginning. This intense period of upheaval and uncertainty fueled a desire for order, clarity, and a fresh start, which the Bauhaus aimed to provide through design. Before the Bauhaus, art movements like Expressionism had already challenged traditional forms, focusing on subjective experience and emotional expression, often with bold colors and distorted shapes. This paved the way for the Bauhaus's own break from the past, though the school would pivot towards a more rational, functional aesthetic. While Expressionism often sought to convey intense inner feelings through dramatic distortion and vibrant, non-naturalistic color, the Bauhaus, while appreciating this break from tradition, shifted its focus to clarity, structure, and the practical application of design principles. It was a response to the chaos, a belief that good design could help rebuild society itself.

There was a perceived disconnect between the 'fine' arts (painting, sculpture) and the 'applied' arts or crafts (furniture, textiles, architecture). The traditional guild system felt outdated, and artists often felt isolated from the practical needs of society. Walter Gropius, the visionary architect who founded the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1919, had this wild, utopian idea: tear down the walls between art and craft. Bring artists, architects, designers, and craftspeople together under one roof. Teach them to work together, using modern technology and industrial methods, to create beautiful, functional objects and buildings for everyone. Art for the people, not just the fancy folks. It sounds almost naive now, but imagine how revolutionary that must have felt back then – a genuine attempt to integrate creativity into the very fabric of daily life, to make the everyday beautiful and accessible. From my own perspective as an artist, the sheer audacity of this vision, especially in such a turbulent time, is breathtaking. It wasn't just about making pretty things; it was about fundamentally reshaping society through design.

It was radical. They weren't just teaching painting or sculpture in isolation. The curriculum itself was revolutionary, starting with the mandatory Vorkurs (Preliminary Course). Led initially by Johannes Itten, and later by artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, this foundational course stripped away traditional techniques and focused on the fundamental elements of art and design: material, form, color, texture, and composition. The revolutionary part? It forced students to confront the essence of design, to understand materials and forms intrinsically, rather than just copying historical styles or techniques. It was about freeing creativity and developing a personal understanding of design principles through hands-on experimentation, moving away from simply replicating old masters. I remember reading about one Vorkurs exercise where students were given various materials – paper, fabric, wood, metal – and tasked with exploring their textures and structural properties without trying to make anything representational. Another involved exploring the emotional impact of different color combinations or the dynamic tension created by simple lines and shapes on a page. It was purely about understanding the inherent qualities of the material and the visual language itself. Honestly, it sounds like the kind of mind-bending challenge that would either make you quit art forever or completely redefine how you see the world. I lean towards the latter, thankfully.

After the Vorkurs, students moved into specialized workshops. They had workshops for weaving, pottery, metalworking, typography, furniture design, and even theatre. The goal was a "total work of art" (Gesamtkunstwerk) – the idea that everything from the building itself to the doorknobs, the furniture, the textiles, and the posters on the wall should be part of a unified, thoughtful design. While the Sommerfeld House showed this ambition, the Bauhaus building in Dessau, designed by Gropius, truly embodied the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal for the school itself, integrating workshops, administrative offices, and student housing into a cohesive, functional structure. Form follows function was a key principle, emphasizing practicality, simplicity, and efficiency, often with an eye towards mass production. But it wasn't just about function; it was about making everyday life beautiful and harmonious. For instance, a Vorkurs exploration of material properties might lead a student in the metal workshop to design a teapot (like Marianne Brandt's iconic model) that is not only aesthetically pleasing with its geometric form but also perfectly balanced for pouring and efficient to manufacture. Or perhaps a student in the weaving workshop, after exploring the tactile qualities of different threads, might design a textile that uses innovative patterns and materials (like Anni Albers did with cellophane and horsehair) that are both visually striking and structurally sound for architectural use. The elegance of a well-designed chair, the satisfying feel of a functional doorknob – these were just as important as their utility.

It wasn't always smooth sailing, of course. The school faced constant political pressure and internal disagreements about its direction. It moved from Weimar to Dessau in 1925, a city more aligned with industrial production because of its existing factories and infrastructure, which shifted the school's focus further towards design for mass manufacturing. Gropius designed a new, iconic building in Dessau that perfectly embodied the school's principles with its glass curtain walls, asymmetrical layout, and functional workshops. Hannes Meyer took over as director after Gropius, pushing a more strictly functionalist and socialist agenda, emphasizing scientific analysis and collective work over individual artistic expression. This caused internal friction and led to his dismissal, partly due to his political activities clashing with the increasingly conservative political climate. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe became the final director when the school moved briefly to Berlin, focusing primarily on architecture before the Nazis, who saw the Bauhaus's modern, international style as a threat and labeled it "degenerate art," finally shut it down in 1933. "Degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst) was a term used by the Nazi regime to describe virtually all modern art, which they considered un-German, Jewish, or Communist, and which they believed corrupted German culture. The Bauhaus, with its progressive, international outlook and diverse faculty, was a prime target. The closure meant artists and teachers were forced to flee, often leaving their work and lives behind, scattering the Bauhaus seed across the globe. Figures like Josef and Anni Albers went to the US, teaching at Black Mountain College, while Gropius and Mies van der Rohe ended up at Harvard and the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) respectively, directly influencing design education in America.

The Mavericks: Bauhaus Artists Who Left Their Mark

So, that's the backdrop – a revolutionary school born from chaos, aiming to reshape the world through integrated art and design. But who were the people actually doing it? While Gropius set the stage, it was the incredible roster of artists teaching and studying there who truly brought the Bauhaus philosophy to life. These weren't just teachers; they were pioneers, pushing boundaries in every medium imaginable. Thinking about the history of modern art? You can't skip these names. These are some of the pivotal figures whose work and ideas are essential to understanding the Bauhaus story, and some whose influence resonates deeply with me personally.

Let's talk about a few who really resonate with me, and some others whose work you might recognize even if you didn't know the name:

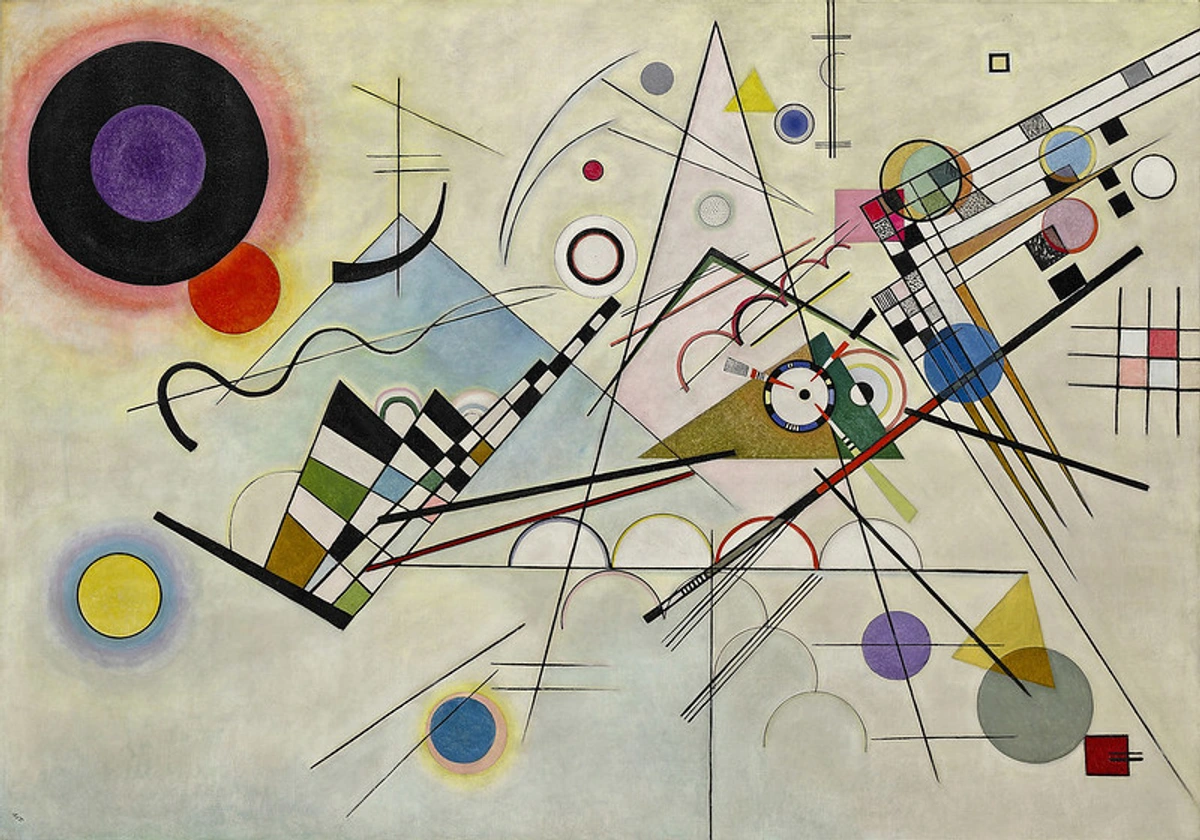

Wassily Kandinsky: The Spiritual Side of Abstract

Kandinsky was already a big deal in the world of abstract art before he came to the Bauhaus. But his time there, especially teaching the preliminary course and later his analytical drawing class, solidified his ideas about the spiritual nature of art and the psychological effects of color and form. He saw abstract painting not just as shapes and colors, but as a way to express inner feelings and connect with the viewer on a deeper level. His work, like "Composition VIII," feels like visual music – a symphony of lines and colors. Looking at "Composition VIII" makes me think about the deliberate placement of every element, how the colors vibrate against each other, and how it evokes a sense of dynamic energy, much like a complex musical piece. It makes me think about how my own abstract pieces aim to evoke a feeling or a sense of movement, much like a piece of music does.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/gandalfsgallery/24121659925, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

He taught students to analyze the fundamental elements of art – point, line, plane – and understand their inherent properties and emotional impact. His teaching materials, like his book Point and Line to Plane, systematically explored these concepts. It's something I think about constantly in my own work – how a simple line or a specific color choice can completely change the feeling of a piece. (Speaking of color, you might like my guide on how artists use color).

Paul Klee: The Poet of the Line

Klee was another giant. His work is harder to pin down – it's whimsical, deeply personal, and often feels like a dream or a child's drawing, but with incredible sophistication. He was fascinated by the process of creation, the journey of a line, and the way art could reveal the hidden structures of the world. His teaching at the Bauhaus was legendary; he encouraged students to explore their own unique vision rather than just copy a style. Works like "Ad Parnassum" showcase his intricate, almost musical approach to color and form. He believed that drawing was like taking a line for a walk. I love that idea. It reminds me that sometimes, the best way to start is just to make a mark and see where it leads. It's a philosophy that resonates with anyone trying to find their own personal art style.

Josef and Anni Albers: Masters of Material and Color

Josef Albers is famous for his "Homage to the Square" series, where he explored the interaction of colors within a consistent square format, and his groundbreaking book Interaction of Color. He taught that color is relative – how we perceive a color depends entirely on the colors around it. This isn't just an academic point; it's a profound truth about perception itself. Think about how a grey square can look completely different depending on whether it's placed on a bright yellow background or a deep blue one. Or how the color of a piece of clothing seems different under fluorescent light versus natural sunlight. It's a simple idea with profound implications, especially when you're trying to choose art based on room color. His systematic approach to color theory directly informed his teaching, encouraging students to understand color through empirical observation and experimentation. As an artist, his work feels like a scientific exploration of a deeply emotional subject – color. It makes me look at my own palette and think about the subtle shifts and interactions I can create.

Anni Albers, his wife, was a textile artist who elevated weaving from a craft to a fine art. She experimented tirelessly with materials, patterns, and structures, creating stunning, complex works that were both beautiful and functional, often designed for architectural spaces. She explored the structural possibilities of threads, creating innovative wall hangings and even designs for industrial production using materials like cellophane and horsehair. Her intellectual approach to weaving, treating threads as a form of language or building material, was revolutionary. Her influence on textile art is immense. Her dedication to exploring the inherent properties of her medium, thread, resonates deeply with my own process of understanding how paint behaves, how colors interact, and how texture can add depth. They were a power couple of material and color exploration, each pushing boundaries in their respective fields while sharing a deep commitment to the Bauhaus principles.

László Moholy-Nagy: The Visionary Designer

Moholy-Nagy was all about the future, technology, and the integration of art into everyday life. He worked across painting, sculpture, photography, film, and graphic design. He saw light and motion as new artistic mediums and experimented with industrial materials like Plexiglas and metal. His experimental approach and focus on industrial materials were hugely influential, especially in graphic design and typography. His "Light-Space Modulator" sculpture, designed to create dynamic light and shadow effects, is a perfect example of his fascination with light and motion as artistic tools. This focus on light and motion as legitimate artistic mediums was particularly radical for the time. He also pioneered the use of photomontage and exhibition design, creating immersive visual experiences. He later brought Bauhaus ideas to the US, founding the New Bauhaus in Chicago (which became the Institute of Design at IIT), directly impacting design education there. His teaching emphasized the use of new technologies and materials, pushing students to think beyond traditional artistic boundaries. His willingness to embrace new technology and materials is something I find incredibly inspiring – it's a reminder that art isn't static; it evolves with the world around it.

Marianne Brandt: The Metal Workshop Pioneer

Often mentioned among the "other" figures, Marianne Brandt deserves a spotlight. She was a student who rose to lead the metal workshop, a traditionally male-dominated field. Her designs for everyday objects like teapots, ashtrays, and lamps are now considered icons of Bauhaus design – functional, elegant, and designed for mass production. Her MT 49 teapot, with its geometric form and practical handle, perfectly embodies the Bauhaus ideal of bringing beautiful, functional design to the masses. Her success in a field dominated by men at the time was a significant achievement, demonstrating the school's commitment to elevating craft to the level of art and designing for the industrial age. Her focus on designing beautiful, functional objects for everyday use is a core part of the Bauhaus legacy that still feels incredibly relevant today.

Oskar Schlemmer: The Stage as a Laboratory

Schlemmer headed the theatre workshop, exploring the relationship between the human body, space, and form. His famous "Triadic Ballet" featured dancers in geometric costumes moving like puppets. It sounds weird, and it was! But it was also a fascinating exploration of how design, movement, and performance could merge, treating the stage as a laboratory for spatial and formal ideas. Beyond the ballet, the theatre workshop explored innovative stage design, lighting, and costume, influencing modern performance art and theatre production. It reminds us that art isn't just something static on a wall; it can be an experience, a performance, a living, breathing thing. His work pushes the boundaries of what "art" can be, which is a constant question I grapple with in my own practice.

Herbert Bayer: Master of Typography and Design

While many contributed to graphic design, Herbert Bayer's impact was particularly profound. He developed the Universal typeface, a geometric sans-serif font, and championed the use of lowercase letters exclusively for efficiency – a bold functionalist statement. His innovative layouts, use of photography, and integration of text and image laid much of the groundwork for modern graphic design and advertising, influencing later movements like Swiss Style. He also applied these principles to exhibition design, creating clear, impactful visual communication in three dimensions. His work embodies the Bauhaus principle of clarity and functionality in visual communication. Every time I choose a font for a website or design a simple layout, I see the echoes of Bayer's work.

Lucia Moholy: Documenting the Vision

Though not a master, Lucia Moholy's photography was crucial in shaping the world's perception of the Bauhaus. She meticulously documented the school's buildings, workshops, and products with a clear, objective style that mirrored the Bauhaus aesthetic itself. Her photographs became the primary visual record of the school's output and were widely disseminated, playing a significant role in spreading its influence globally. Her work highlights the importance of photography as both an artistic medium and a tool for design and documentation within the Bauhaus context. It's a reminder that documenting art is an art form in itself.

Other Key Figures: Design for Life

And beyond these, so many others contributed significantly. Marcel Breuer revolutionized furniture design with his tubular steel chairs, like the iconic Wassily Chair, inspired by bicycle handlebars – a perfect example of form following function using modern materials. His later architectural work, like the striking Breuer Building (now the Met Breuer) in New York, further cemented his legacy. Gunta Stölzl, the only female master at the Bauhaus, transformed the weaving workshop into one of the school's most successful, pushing abstract design and technical innovation in textiles. Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, though not a master, created influential designs for children's toys and furniture in the carpentry workshop, emphasizing simple, functional forms that encouraged creative play. Gertrud Arndt, known for her experimental photography, particularly her series of self-portraits, explored identity and form through the lens, pushing the boundaries of the medium within the Bauhaus context. Wilhelm Wagenfeld, also not a master, designed the famous Bauhaus lamp (MT8) in the metal workshop, another enduring icon of functional design.

These are just a few examples. The collaborative environment meant ideas flowed freely, and the impact of each individual multiplied. It's a bit humbling to think about how many brilliant minds were packed into that one school, all pushing the boundaries of what art and design could be. The sheer diversity of talent and focus, from painting and sculpture to weaving, metalwork, and theatre, truly underscores the interdisciplinary nature of the Bauhaus.

The Bauhaus Echo: How Their Influence Lives On

The Bauhaus school itself only lasted 14 years, but its impact is immeasurable. When it closed, its artists scattered, taking their ideas with them to Europe, the US, and beyond. They taught in new schools, designed buildings, created furniture, and influenced generations. The diaspora of Bauhaus masters and students ensured its principles weren't confined to Germany but became a global force, directly influencing later movements like the International Style in architecture and Swiss Style in graphic design.

Think about:

- Architecture: Clean lines, open floor plans, steel, glass, and concrete. The minimalist aesthetic you see everywhere? Thank the Bauhaus (and Mies van der Rohe's "less is more"). The idea of designing buildings that are functional, efficient, and integrated with their environment is a direct legacy. Look at modern skyscrapers or even many contemporary homes – the influence is clear. Think of the Seagram Building in New York by Mies van der Rohe, a prime example of the International Style rooted in Bauhaus principles. Or consider the simple, functional design of many modern apartment buildings.

- Furniture Design: From the chairs you sit on (like that ubiquitous cantilever chair, popularized by Breuer and Mies van der Rohe) to modular shelving systems, Bauhaus designers revolutionized how furniture was conceived and produced. They favored industrial materials and simple, ergonomic forms designed for comfort and mass production. The idea that furniture should be functional, durable, and aesthetically pleasing for everyone is a direct Bauhaus inheritance. Just look at the clean lines and practicality of furniture from places like IKEA – the Bauhaus DNA is definitely there.

- Interior Design: The Bauhaus approach extended beyond individual objects to the entire living space. They advocated for open, flexible floor plans, integrated storage, and the use of color and light to create harmonious and functional environments. The emphasis was on creating a cohesive Gesamtkunstwerk within the home, where furniture, textiles, lighting, and art all worked together as a total work of art. This holistic view of interior space planning is a key part of their legacy. Think about the popularity of open-plan living or built-in storage solutions today.

- Product Design: While often linked to industrial design, the Bauhaus influence is seen in the design of countless everyday objects, from kitchen appliances and lighting fixtures to electronics and even toys. The focus on simplicity, functionality, and suitability for mass production led to designs that were not only efficient to manufacture but also intuitive and pleasant to use. Even the simple, functional design of your smartphone has roots in this philosophy. Look at the clean, unadorned design of a modern toaster or a desk lamp. Or maybe that perfectly balanced, easy-to-grip vegetable peeler in your kitchen drawer? That's Bauhaus thinking in action.

- Graphic Design: The use of grids, sans-serif fonts, asymmetrical layouts, and the integration of text and image – standard practice today, revolutionary then, thanks to artists like Herbert Bayer and Moholy-Nagy. Their work laid the groundwork for modern visual communication, from book covers to advertising posters and website layouts, heavily influencing the development of Swiss Style graphic design. Look at the clean, clear design of public signage or corporate logos – the Bauhaus influence is undeniable. Even the layout of this very page owes something to their principles of clarity and hierarchy.

- Textile Design: Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl transformed weaving into a significant art form, exploring abstract patterns, textures, and the structural possibilities of threads. Their work influenced modern textile manufacturing and design, bringing abstract art principles into fabrics for both interiors and fashion. The use of geometric patterns and bold color blocking in modern textiles often echoes Bauhaus principles.

- Photography and Film: While not always highlighted, the Bauhaus, particularly through Moholy-Nagy and the documentation work of Lucia Moholy, explored photography as an independent art form and a tool for design. Experimentation with light, shadow, perspective, and photomontage pushed the medium forward. Early abstract and experimental film also found a home here, exploring rhythm, form, and light in motion. This experimental approach influenced later avant-garde film and photography. Think of the clean, compositional style of much modern product photography or the use of dynamic angles in film.

- Art Education: The Bauhaus approach to teaching, focusing on fundamental elements, experimentation, interdisciplinary work, and the integration of theory and practice, changed how art and design are taught worldwide. The Vorkurs model, in particular, was widely adopted by art schools globally because it shifted the focus from rote copying of historical styles to developing a fundamental understanding of materials, form, and color, fostering creative problem-solving and individual expression. The legacy of the workshop model, where students learned by doing and collaborating across disciplines, is also a cornerstone of modern design education.

It's kind of wild to think that a small school in Germany a century ago could have such a profound, lasting effect on the visual world we inhabit every single day. It makes you appreciate the power of ideas, doesn't it? And the power of artists who aren't afraid to break the mold. It makes me think about my own work and how I hope it connects with people's lives, not just as something to look at, but maybe something that subtly enhances their space or shifts their perspective, much like a well-designed chair or a perfectly balanced abstract painting can. It's a reminder that even small, focused creative movements can have ripple effects that last for generations.

Spotting the Bauhaus Around You (Beyond the Museum)

Ready to play detective? The Bauhaus influence is so woven into the fabric of modern life that you see it everywhere, once you know what to look for. So, how do you spot this "secret language" in the wild? Here are some key characteristics:

- Geometric Forms: Circles, squares, triangles, and straight lines are dominant. Why? They were seen as universal, pure forms, easy to reproduce, and embodying clarity and order.

- Primary Colors: Red, yellow, and blue, often used alongside black, white, and gray. Why? Like geometric forms, primary colors were considered fundamental and universal, creating bold, clear visual statements.

- Sans-serif Typography: Clean, simple fonts without decorative serifs. Why? Sans-serif fonts were seen as modern, legible, and functional, stripping away historical ornamentation for clarity.

- Functionality: Design is driven by the object's purpose. Why? The core principle of "form follows function" meant that the utility of an object dictated its design, ensuring efficiency and practicality.

- Simplicity & Minimalism: Avoiding unnecessary ornamentation. (Though remember, early Bauhaus had Expressionist leanings, and not everything was strictly minimalist!) Why? Simplicity was linked to functionality and mass production – less ornamentation meant easier, cheaper manufacturing and clearer design.

- Asymmetry: Often used in layouts and compositions to create dynamic balance, particularly in graphic design and architecture, contrasting with traditional symmetrical approaches. Why? Asymmetry was seen as modern and dynamic, reflecting the energy of the industrial age and breaking from static, historical compositions.

- Industrial Materials: Use of steel, glass, concrete, plywood, and other materials suited for mass production. Why? Embracing modern materials and industrial techniques was central to the Bauhaus mission of designing for the machine age and making good design accessible.

- Integration of Art and Technology/Industry: A core belief that art and design should embrace modern industrial methods and technology to create objects for mass production. Why? This was the foundational principle – bridging the gap between the artist's studio and the factory floor to create a better-designed world for everyone.

Look at the design of your smartphone – clean lines, focus on function. The layout of a magazine, the architecture of a modern office building, the simple elegance of a well-designed kitchen appliance. That's the Bauhaus legacy in action. I recently saw a public park bench – simple, metal, clean lines, clearly designed for durability and function. No fussy details, just pure utility and a quiet aesthetic. That's Bauhaus thinking, right there in the park. Or maybe you've seen a poster or book cover with bold, geometric type and a simple, striking layout? That's the Bauhaus graphic design influence staring right back at you. I even spotted it recently in the clean, modular design of a new coffee shop interior – the simple furniture, the geometric lighting fixtures, the uncluttered space. It's truly pervasive.

https://freerangestock.com/photos/159386/modern-dining-area-with-abstract-wall-art.html, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

While you can see incredible Bauhaus pieces in major museums around the world (like these best museums and galleries), their influence is so woven into the fabric of modern life that you see it everywhere. If you want to dive deeper, seek out museums with strong modern design collections. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Design Museum in London, and the Bauhaus Archive in Berlin are great places to start. The Bauhaus Dessau Foundation also offers incredible insights and access to the historical sites. But honestly, just start noticing the design around you. You'll see it. Maybe you'll spot a chair that reminds you of Breuer, or appreciate the clean lines of a building in a new way. It's like learning a new visual language.

And maybe, just maybe, it will inspire you to think differently about the objects you choose for your own space. About how art at home isn't just decoration, but part of creating a functional, beautiful, and personal environment. It makes me think about how my own abstract art, with its focus on color, form, and composition, aims to bring a sense of order and beauty into a space, much like the Bauhaus designers intended with their functional objects. (If you're looking to buy art for less that fits a modern aesthetic, you know where to look! Or perhaps consider a piece that plays with color and form in a way that feels distinctly Bauhaus-inspired, like some of my own abstract art).

Frequently Asked Questions About Bauhaus Artists and Design

What was the main goal of the Bauhaus school?

The main goal was to unify art, craft, and technology to create functional and beautiful designs for everyday life, often with an emphasis on prototypes for mass production. They aimed to bridge the gap between the artist and the craftsman and make well-designed objects accessible to everyone, believing good design could help rebuild society after the war.

Why was the Bauhaus considered revolutionary?

It was revolutionary for several reasons: its interdisciplinary approach combining fine arts, crafts, and technology; its focus on functionality and design for mass production; its innovative curriculum, particularly the foundational Vorkurs which emphasized material and form exploration over traditional techniques; and its utopian vision of integrating art into everyday life to improve society. It broke significantly from traditional art education and production methods.

Who were some of the most influential Bauhaus artists and designers?

Key figures include founder Walter Gropius (architecture), Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (architecture, final director), Marcel Breuer (furniture, architecture), Wassily Kandinsky (painting, color theory), Paul Klee (painting, drawing theory), Josef Albers (painting, color theory), Anni Albers (textiles), László Moholy-Nagy (photography, design, typography), Marianne Brandt (metalwork), Gunta Stölzl (textiles), Alma Siedhoff-Buscher (toys, furniture), Gertrud Arndt (photography), and Herbert Bayer (graphic design). Wilhelm Wagenfeld (metalwork) is also notable for his iconic lamp design. Lucia Moholy's photography was also highly influential in documenting the school.

How did the Bauhaus curriculum differ from traditional art schools?

Traditional schools often separated fine arts from crafts and focused on copying masters. The Bauhaus started with a mandatory preliminary course (Vorkurs) focused on fundamental elements (material, form, color) and experimentation, encouraging students to develop their own creative understanding before specializing in interdisciplinary workshops. This hands-on, experimental approach, combined with the workshop model, was revolutionary, emphasizing learning by doing and collaboration.

Did the Bauhaus have a political agenda?

While the Bauhaus was founded with utopian ideals of social improvement through design, it wasn't explicitly tied to a single political party. However, its progressive, internationalist, and sometimes socialist-leaning ideas (especially under Hannes Meyer) made it a target for conservative and nationalist forces, ultimately leading to its closure by the Nazi regime, who viewed its modernism as a form of "degenerate art." Its political stance was more about social reform through design than party politics.

What are some iconic examples of Bauhaus design?

Famous examples include Marcel Breuer's Wassily Chair and Cesca Chair, Marianne Brandt's MT 49 teapot, Wilhelm Wagenfeld's MT8 lamp, Herbert Bayer's Universal typeface, and the Bauhaus building in Dessau designed by Walter Gropius. These pieces exemplify the school's principles of functionality, simplicity, and innovative use of materials for mass production.

Where can I see Bauhaus art and design today?

Major art and design museums worldwide, such as MoMA (New York), the Design Museum (London), and the Centre Pompidou (Paris), have significant Bauhaus collections. The Bauhaus Archive in Berlin and the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation are dedicated specifically to the school's history and work. You can also see the influence in modern architecture and everyday objects globally – just look for those clean lines and functional forms! Many museums focusing on modern art or design will feature Bauhaus pieces.

My Final Thoughts: A Legacy of Integration

Thinking about the Bauhaus artists always makes me feel a bit... energized. They weren't content to stay in their lane. They wanted to break down barriers, experiment, and make art relevant to everyday life. That spirit of integration – of art, craft, design, and life – is something I deeply admire and try to bring into my own work and my own space. It's a reminder that creativity isn't confined to a canvas or a pedestal. It's in the chair you sit on, the book you read, the building you walk into. The Bauhaus artists didn't just create beautiful things; they created a way of thinking about the world that continues to inspire and shape us. And for that, I'm incredibly grateful.

Maybe next time you look at a simple, elegant object, you'll see a little bit of that Bauhaus magic too. It's there, waiting to be noticed. It's a quiet revolution still happening all around us. And perhaps, just perhaps, it makes you look at the art you choose for your own home differently, seeing it not just as decoration, but as part of that larger, integrated design for living. (Find art that speaks to you).

https://www.flickr.com/photos/romseyfestival/35895267135, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/deed.en