Surrealism Explained: An Artist's Personal Guide to the Art of Dreams & the Unconscious

Dive into the weird & wonderful world of Surrealism! An artist's personal guide exploring its origins, meaning, key artists (Dalí, Magritte, Carrington), techniques, influence on film/fashion/politics/music & its global reach. Discover why it still matters today, connecting it to my own creative process.

Diving Headfirst into the Weird: My Personal Guide to Surrealism

Ever wake up from a dream so vivid, so utterly bizarre, that the real world feels a bit... off for a while? Like you accidentally left the weird filter on? That delightful (or sometimes unsettling) disorientation often makes me think of Surrealism. It emerged from a world grappling with the chaos and irrationality that led to World War I, a time when faith in pure reason felt shattered. The sheer scale of the destruction and the seemingly senseless loss of life forced a profound questioning of the rational systems and societal norms that were supposed to prevent such a catastrophe. If logic and reason led to this, perhaps the answers lay elsewhere – in the irrational, the subconscious, the dream. The war exposed the deep, unsettling chasm between the ordered, rational world society claimed to be, and the chaotic, violent reality it had become. Surrealism was born from this disillusionment, a radical attempt to find a deeper, more authentic reality by plumbing the depths of the human psyche.

Surrealism wasn't just an art movement; it was a radical response to a world that felt fundamentally broken. Born in the aftermath of WWI, it rejected the rationalism and bourgeois values that many believed had led to the conflict. Influenced heavily by the burgeoning field of psychoanalysis, particularly Sigmund Freud's work on the unconscious, dreams, and repressed desires, Surrealists sought a new way to understand reality – one that embraced the irrational, the subconscious, and the dreamlike. Freud's model of the mind – the primal id (our instinctual drives), the rational ego (our conscious self navigating reality), and the moralistic superego (our internalized societal rules) – provided a theoretical map. Their goal was to bypass the ego and superego to tap directly into the raw energy and truth of the id, as revealed in dreams and spontaneous thought. Freud's analysis of dreams, seeing them not as random noise but as coded messages from the unconscious, provided a theoretical framework for the Surrealist exploration of the dream world as a valid, even superior, reality. They were also loosely influenced by earlier movements like Symbolism, which had already begun to explore the power of symbols and the subjective inner world, hinting at the irrational realms Surrealism would later fully embrace.

So, grab your own metaphorical melting clock, and let's wander through the dreamscape of Surrealism together. This isn't going to be a dry lecture – think of it more like me rambling thoughtfully about art that decided logic was overrated.

What Even Is Surrealism, When You Get Down to It?

Okay, the official story goes something like this: Surrealism kicked off in Paris around the 1920s, spearheaded by writer André Breton. It was born out of the ashes of Dadaism, a movement that rejected logic and reason in the face of WWI's absurdity. While sharing Dada's anti-rational stance, Surrealism had a more constructive goal: to explore the unconscious as a source of truth and creativity, to synthesize dream and reality into a 'super-reality' (sur-reality). The weirdness in Surrealism isn't random; it's a tool to bypass the rational mind and access deeper psychological truths. The juxtapositions are meant to spark new associations and insights in the viewer, tapping into their own unconscious. It's a carefully constructed weirdness, if that makes sense. Think of a lobster on a telephone – it's not just random; it forces your rational mind to stumble, opening a door to unexpected connections and symbolic interpretations from your subconscious.

This vision was formally laid out in André Breton's First Surrealist Manifesto (1924), which defined Surrealism as "pure psychic automatism... to express the actual functioning of thought... in the absence of any control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation." It was a call to arms for the imagination, a declaration that the dream world held as much, if not more, truth than waking life. A Second Surrealist Manifesto followed in 1930, which saw Breton place a greater emphasis on the political dimension of Surrealism, aligning the movement more explicitly with revolutionary ideals and the Communist Party, though this relationship remained complex and often fraught.

Key figures like Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard, and Benjamin Péret were also instrumental in shaping the early movement alongside Breton.

Within Surrealism, two main approaches emerged: Veristic Surrealism, which aimed to depict dreamlike scenes with realistic, often academic precision, making the impossible seem disturbingly real; and Abstract Surrealism, which used biomorphic shapes, abstract forms, and automatist techniques to evoke the feeling or energy of the unconscious without depicting recognizable objects.

But for me? Surrealism is about permission. Permission to be illogical. Permission to let those bizarre connections your brain makes in the dead of night see the light of day. It’s about acknowledging that reality isn't always as neat and tidy as we pretend it is. Sometimes, reality is a lobster on a telephone, and that’s okay. It's the art world saying, "Hey, that weird thought you just had? That fleeting, nonsensical image? That's valid. Explore that."

It’s a rebellion against the mundane, a celebration of the uncanny. Think about it – how often do you have a thought that seems to come from nowhere, a strange image flashing in your mind? Surrealism says, yes, pay attention to that. It's about giving voice and form to the subconscious whispers, the stuff that bubbles up when the logical censor is asleep. It's less about depicting external reality and more about depicting the inner reality, the landscape of the mind and dreams.

A key concept for the Surrealists, particularly for Breton, was "convulsive beauty" (beauté convulsive). This wasn't about traditional aesthetics; it was about finding beauty in the unexpected, the unsettling, the bizarre, and the irrational – moments where the ordinary is disrupted by the extraordinary, often with a sense of shock or revelation. It's the beauty found in a chance encounter, a strange juxtaposition, or a sudden, inexplicable image. Think of the unsettling beauty of a lightning strike illuminating a familiar landscape, or the strange, compelling symmetry of certain deep-sea creatures – these can evoke a sense of convulsive beauty, disrupting our normal perception and revealing something both beautiful and slightly terrifying.

Surrealism vs. Other Movements: A Quick Distinction

Sometimes people look at Surrealism and think, "Okay, but is it just random?" And it's a fair question! On the surface, it can seem chaotic, like a bunch of unrelated strange things thrown together. But there's a method to the madness. The weirdness isn't the point itself; it's a tool to bypass the rational mind and access deeper psychological truths.

Let's break down the differences between Surrealism and some related movements:

Feature | Dadaism | Surrealism | Magical Realism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | WWI (c. 1916) | Post-WWI (c. 1924) | Primarily 20th Century Literature (often Latin America), later visual arts. |

| Core Aim | Reject logic, reason, bourgeois society; provoke, dismantle. | Explore the unconscious; synthesize dream & reality into a 'sur-reality'. | Integrate magical/fantastical elements into everyday reality without explanation. |

| Approach | Anti-art, absurdity, spontaneity, chaos. | Automatism, dream analysis, juxtaposition; often meticulous technique. | Realistic depiction of the world where the magical is simply part of it. |

| Focus | Reaction to external chaos; destruction. | Exploration of internal psyche; creation of a new reality. | Depiction of reality where the extraordinary coexists with the ordinary. |

| Example Vibe | A chaotic, angry protest. | A strange, symbolic dream made real. | A normal day where something impossible just happens, and no one questions it. |

The key difference between Surrealism and its predecessor, Dadaism, is intent. Dada was born out of disillusionment and often aimed to shock and dismantle traditional art and societal norms through absurdity and anti-art. Think of Marcel Duchamp's Fountain) (a urinal signed 'R. Mutt') – it was a gesture of defiance, questioning the very definition of art. Surrealism, while sharing Dada's anti-rational stance, had a more constructive goal: to explore the unconscious as a source of truth and creativity, to synthesize dream and reality into a 'super-reality' (sur-reality). The weirdness in Surrealism isn't random; it's a tool to bypass the rational mind and access deeper psychological truths. The juxtapositions are meant to spark new associations and insights in the viewer, tapping into their own unconscious. It's a carefully constructed weirdness, if that makes sense.

Another point of confusion can be the difference between Surrealism and Magical Realism. While both can feature bizarre or fantastical elements in otherwise realistic settings, Magical Realism typically integrates these elements into the fabric of everyday reality without questioning the nature of reality itself or aiming to disrupt the viewer's perception. The magical is presented as simply part of the world, often with a sense of wonder or acceptance. Surrealism, however, is fundamentally about exploring the inner world, the subconscious, and often deliberately juxtaposes elements to disrupt our perception of reality and reveal the irrational beneath the surface of the mundane. The debate around artists like Frida Kahlo often centers here: while her work is deeply personal and symbolic, drawing heavily on her physical reality, pain, and Mexican culture (which includes elements often perceived as magical), it's argued that she wasn't aiming to depict a 'sur-reality' of the subconscious in the strict Surrealist sense defined by Breton (rooted in automatism and dream analysis), but rather her lived, albeit extraordinary, reality. This aligns more closely with Magical Realism, even though her visual language shares thematic overlaps with Surrealism's exploration of the psyche. Does that distinction make sense, or does it just add another layer of delightful confusion? For me, it highlights how art often defies neat categorization, much like dreams themselves.

The Dream Weavers: Key Surrealist Artists and Their Worlds

When you think of Surrealism, certain names probably pop into your head, often accompanied by equally popping images. These artists weren't just painting weird stuff; they were meticulously crafting windows into their (and our) subconscious. They were explorers of the inner world, using paint, sculpture, photography, film, and other mediums to map the uncharted territory of the mind.

As mentioned, they broadly fell into two camps:

- Veristic Surrealism: Realistic depiction of the unreal, making the impossible seem disturbingly plausible.

- Abstract Surrealism: Using abstract forms and automatist techniques to evoke the feeling or energy of the unconscious.

It's also worth noting the influence of precursors like Giorgio de Chirico, whose Metaphysical Painting (Pittura Metafisica) with its eerie, empty cityscapes, strange juxtapositions of objects, and deep shadows, profoundly impacted the atmosphere and imagery of early Surrealism, particularly for artists like Dalí and Tanguy. His work created a sense of unsettling mystery and a reality just slightly off, which resonated deeply with the Surrealist sensibility.

Let's look at a few who really defined the movement. Note that this list is by no means exhaustive, but highlights some of the most influential figures:

Salvador Dalí: The Master of Melting Clocks (Veristic)

Ah, Dalí. The name itself conjures images of melting clocks, bizarre landscapes, and a magnificent mustache. Dalí was perhaps the most flamboyant face of Surrealism, and his work is instantly recognizable. He called his method the "paranoiac-critical method," which basically meant he'd induce hallucinatory states (often through intense focus or lack of sleep – maybe like that morning coffee disorientation I mentioned?) to access subconscious imagery, then meticulously paint these visions with academic precision. It's like painting a dream with the detail of a photograph, making the impossible seem disturbingly real. I remember seeing The Persistence of Memory for the first time in person, and the small scale, combined with the intense detail, made the melting clocks feel even more unsettling, like a tiny, perfect window into madness.

His most famous work, The Persistence of Memory, with its drooping timepieces, perfectly captures the fluid, distorted nature of time in dreams. But look at something like The Enigma of Desire: My Mother, My Mother, My Mother. It's a landscape of strange, biomorphic forms and text, deeply personal and unsettling. Dalí wasn't just painting; he was performing his subconscious for the world, often with a flair for the dramatic that made him a celebrity. He also created iconic Surrealist Objects, like the Lobster Telephone or the Mae West Lips Sofa, bringing the bizarre juxtapositions into three dimensions.

René Magritte: The Mystery of the Everyday (Veristic)

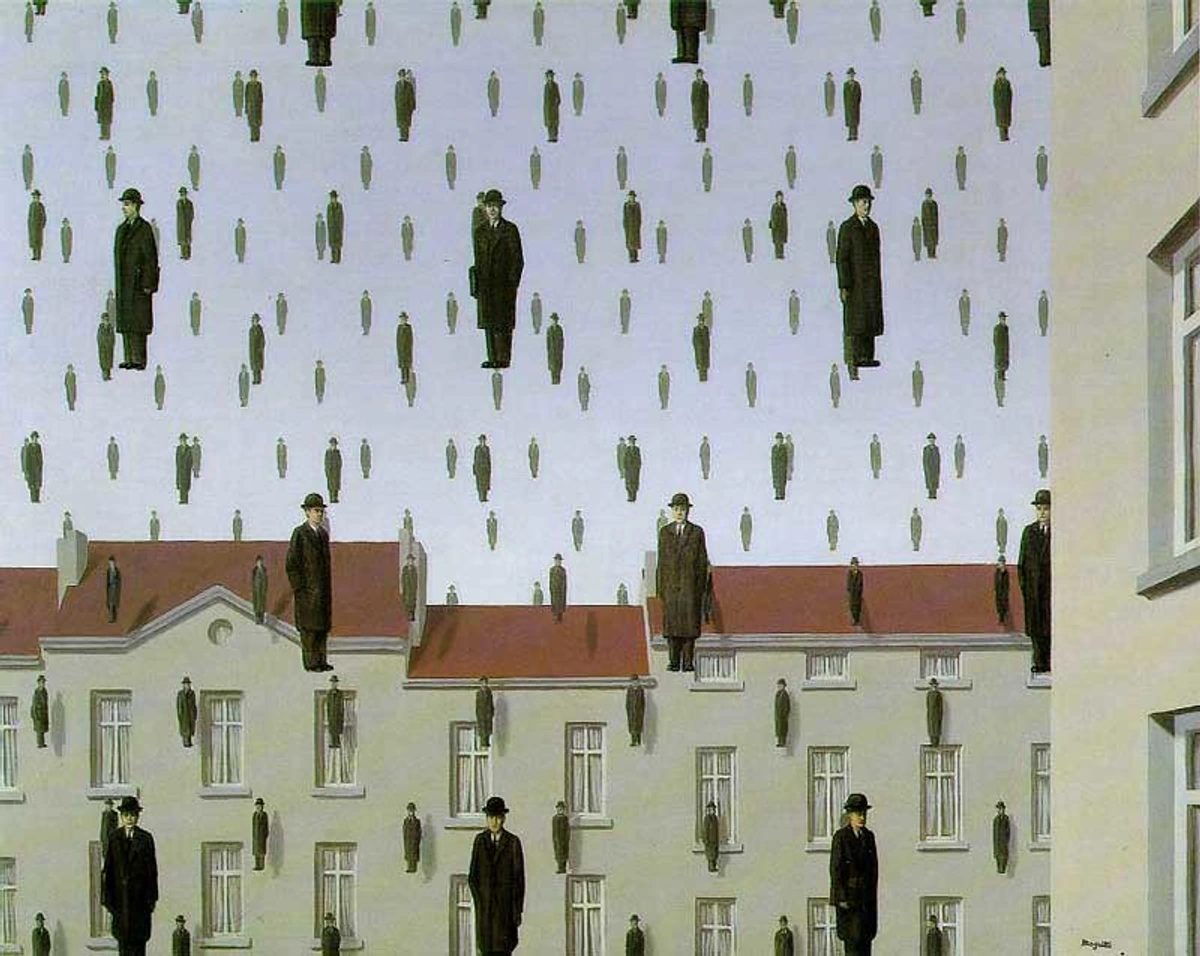

Magritte is the guy who painted apples in front of faces and trains coming out of fireplaces. Unlike Dalí's wild visions, Magritte's work often takes ordinary objects and places them in unexpected, unsettling contexts. His style is clean, almost illustrative, which makes the bizarre juxtapositions even more jarring. He makes you question the reality of the things you see every day, suggesting that even the most familiar things hold hidden mysteries. Seeing a Magritte always feels like a polite, philosophical punch to the gut – it looks so normal, and then... it isn't. It forces you to pause and really look.

The Son of Man (the apple face one) is iconic, but consider Golconda, where men in bowler hats rain from the sky. Or The False Mirror, an eye reflecting a cloudy sky. Magritte's genius lies in making the impossible look utterly plausible, forcing you to confront the strangeness hidden within the familiar. He presents the illogical with such deadpan realism that it feels like a glitch in the matrix of everyday life.

Leonora Carrington: Myth, Magic, and the Feminine (Veristic/Narrative)

A truly unique voice, Leonora Carrington brought a deep engagement with mythology, alchemy, and the occult to Surrealism, often filtered through a distinctly feminine and autobiographical lens. Her paintings are like vivid, complex dreams or scenes from forgotten fairy tales, populated by hybrid creatures, animals, and mysterious rituals. Works like Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) or The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg) are rich with symbolism and narrative, drawing on her experiences and explorations of esoteric knowledge. Her contribution challenged the often male-centric narratives of early Surrealism, offering powerful visions of female agency and transformation. Her work feels ancient and deeply personal at the same time.

Joan Miró: The Playful Biomorphist (Abstract)

Miró's work feels different – more abstract, more playful, like doodles from a cosmic kindergarten. He was deeply interested in automatism, letting his hand move freely to tap into the unconscious. His canvases are often filled with vibrant colors, strange biomorphic shapes, stars, and eyes. It feels less like a literal dream narrative and more like the feeling or energy of dreaming, a direct line from the subconscious onto the canvas. Looking at a Miró always makes me feel a sense of childlike wonder and freedom, like the rules of gravity and form have been temporarily suspended.

Works like Harlequin's Carnival or pieces from his Constellations series perfectly capture this sense of spontaneous, joyful exploration of form and color, populated by whimsical, almost childlike figures and symbols. Miró invited viewers to enter his playful, internal universe.

Max Ernst: Explorer of Technique (Abstract)

Max Ernst was a true innovator of Surrealist techniques. He was a pioneer of frottage (rubbing over textured surfaces to create images) and decalcomania (pressing paint between two surfaces and pulling them apart), using these methods to generate unexpected forms and textures that sparked his imagination. His work often features unsettling, hybrid creatures and dense, dreamlike landscapes, like in Europe After the Rain II. Ernst's approach felt more about discovering the unconscious through the materials and processes themselves, letting chance play a significant role.

Yves Tanguy: Landscapes of the Mind (Veristic)

Yves Tanguy created vast, desolate landscapes populated by strange, elongated, bone-like forms. His paintings, like The Ram, The Spectral Cow, evoke a sense of alien worlds or the deep, silent spaces of the subconscious. There's a quiet, eerie stillness to his work, a feeling of being adrift in a dream where familiar laws don't apply. His precise, smooth painting style makes these impossible landscapes feel strangely real and infinite.

Other Notable Surrealists

Beyond these giants, many other artists, both men and women, made significant contributions, expanding the movement's reach and diversity across various mediums. While the movement was officially founded by men, women artists like Carrington, Remedios Varo, Meret Oppenheim, Dorothea Tanning, and Claude Cahun were integral, though they often faced challenges in gaining equal recognition and their unique perspectives sometimes diverged from Breton's strict definitions.

Hans Arp (biomorphic sculpture) explored biomorphic forms in sculpture and collage, often using chance in his compositions. His organic, flowing shapes feel like they emerged directly from nature or the subconscious. André Masson (automatic drawing) was a key figure in developing automatic drawing, letting his pen move freely across the page to tap into subconscious imagery, which heavily influenced Abstract Expressionism. His frenetic, spontaneous lines capture the raw energy of the unconscious mind.

Among the women, Remedios Varo (alchemical narratives), a close friend of Carrington, created intricate, dreamlike narratives featuring ethereal figures engaged in mysterious, alchemical, or scientific pursuits within fantastical architectural settings. Works like Sympathy (The Angora Cat) or Creation of the Birds feel like illustrations from a forgotten book of magic, filled with quiet, purposeful strangeness. Meret Oppenheim (provocative objects) is known for her provocative objects, most famously Object (Le Déjeuner en fourrure) (a teacup, saucer, and spoon covered in gazelle fur), which perfectly embodies the Surrealist principle of uncanny juxtaposition. Dorothea Tanning (psychological depth) evolved from unsettling domestic scenes to more abstract, fleshy, and intertwined forms, always maintaining a sense of mystery and psychological depth. Claude Cahun (identity through photography) used photography for striking self-portraits exploring gender and identity, anticipating later performance art. Lee Miller (surreal photography, war documentation), a photographer, captured surreal juxtapositions in everyday life and documented the horrors of war with an unflinching eye. These artists, whether working in veristic or abstract styles, collectively pushed the boundaries of what art could depict and how it could be made.

Unlocking the Unconscious: Surrealist Techniques

So, how did these artists actually do it? How did they bypass that pesky rational mind to access the raw material of the unconscious? They developed and employed a range of techniques designed to loosen conscious control and allow the subconscious to surface. Think of them as keys to the dream world, methods for inviting happy accidents and unexpected connections. From a psychological perspective, these techniques work by disrupting habitual thought patterns and conscious control, allowing random input or spontaneous action to spark associations and imagery that would normally be filtered out by the rational mind. It's about creating conditions where the unconscious can 'speak'. It's important to note that these techniques weren't always used in isolation; they were often employed in combination or as starting points for a work, which would then be refined by the conscious mind.

Here are some of the key methods they used:

- Automatism: This is like automatic writing, but with art supplies. The artist tries to clear their mind and let their hand move spontaneously across the canvas or paper, creating lines, shapes, or words without conscious planning. The goal is pure, unfiltered expression directly from the unconscious, bypassing the critical filter of the conscious mind (the ego). It's about trusting instinct over intention, letting the id speak directly. I've tried automatism myself – just letting my hand scribble without thinking. It's surprisingly difficult to truly turn off the internal editor, but fascinating what shapes and feelings emerge when you try. It feels a bit like trying to catch smoke with your bare hands – elusive but potentially revealing.

- The Paranoiac-Critical Method: Developed by Salvador Dalí, this technique involved inducing a state of paranoid delusion (or intense focus) to systematically explore subconscious associations and interpret ambiguous images. Dalí would use this state to perceive multiple images within a single form, which he would then meticulously render with hyper-realistic detail. It was a way of actively engaging with and formalizing the irrational. It's like finding faces in clouds, but then painting them with the precision of a Renaissance master.

- Exquisite Corpse (Cadavre Exquis): A collaborative game where participants take turns adding to a drawing or text, each person only seeing the very end of what the previous person did. The result is often a bizarre, unexpected, and collectively unconscious creation. It's a fun way to see what happens when logic takes a backseat and multiple subconscious minds collide, tapping into a shared, unpredictable creative space. It's like a visual game of telephone, but the message is from the collective id.

- Frottage: Developed by Max Ernst, this involves placing paper over a textured surface (like wood grain or leaves) and rubbing with a pencil or crayon to create an image. The resulting textures and patterns can then be incorporated into a larger work, sparking new ideas from the accidental forms. It's a way of finding images in the world, rather than inventing them, letting the external world trigger internal associations. I imagine this feels a bit like finding shapes in clouds, but with a pencil.

- Decalcomania: This technique involves spreading thick paint on a surface (like paper or glass) and then pressing another surface onto it and pulling them apart. The resulting patterns are often organic and unpredictable, resembling natural forms or textures, which the artist can then use as a starting point for a painting. It's controlled chaos, letting the material itself suggest the form.

- Fumage: A technique where the artist uses the smoke from a candle or lamp to create patterns on paper or canvas, which are then used as a basis for a painting. It's another way of inviting chance and unexpected forms into the creative process.

- Grattage: Developed by Max Ernst, this involves scraping paint off a canvas to reveal the texture or color underneath, often after placing a textured object beneath the canvas. It's like reverse painting, uncovering hidden images.

- Collage and Assemblage: Collage (assembling different images or materials) and Assemblage (creating three-dimensional works from found objects) are other ways to introduce chance and unexpected juxtapositions into the creative process, allowing the artist to react to unplanned elements and discover meaning in accidental arrangements. Like frottage and decalcomania, they rely on chance to provide the initial spark, bypassing conscious decision-making.

- The Surrealist Object: Beyond paintings and sculptures, Surrealists created objects by combining unrelated items in unexpected ways. These objects, like Oppenheim's fur-covered teacup or Dalí's Lobster Telephone, aimed to disrupt the viewer's expectations and evoke a sense of the uncanny, transforming the mundane into something bizarre and symbolic. They are physical manifestations of the bizarre juxtapositions found in dreams. The concept of the uncanny (Unheimlich), as explored by Freud, is deeply relevant here – it's the feeling of something familiar being made strange and unsettling, which is a hallmark of many Surrealist objects and images.

These techniques weren't just gimmicks; they were serious attempts to access a deeper truth, a different kind of reality than the one dictated by logic and convention. They were tools for psychological exploration.

Try This At Home: Grab some paper and a pencil and just draw without thinking for five minutes. Let your hand move freely. Don't try to draw anything specific. See what emerges. This is a simple form of automatism, a way to let your subconscious make marks without your conscious mind interfering. It might surprise you – you might find a hidden corner of your own mind peeking through.

Try This At Home Too: Find three completely unrelated objects around your house right now. A spoon, a sock, and a houseplant, maybe? Put them together in a way that feels strange or unexpected. What kind of story or feeling does that combination evoke? That's a mini-Surrealist object!

Surrealism's Enduring Influence and Global Reach

The techniques and philosophy of Surrealism weren't confined to painting and sculpture. Its influence seeped into almost every creative field, proving that the principles of accessing the unconscious and embracing the illogical had universal power. It wasn't just an art movement; it was a way of thinking, a cultural force that sought to challenge the status quo in art, society, and politics.

Influence in the Arts

In literature, automatic writing was a core practice, leading to stream-of-consciousness narratives and unexpected linguistic connections. André Breton's novel Nadja, for instance, blurs the lines between reality and hallucination, documenting encounters in a dreamlike, non-linear fashion. It's about the raw, unfiltered flow of words from the subconscious. Poets like Paul Éluard and Louis Aragon also explored subconscious imagery and linguistic freedom.

Film became a perfect medium for Surrealist ideas, allowing for dreamlike sequences, jarring edits, and symbolic imagery that defied linear storytelling. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí's short film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) is a prime example, famous for its shocking opening scene (the eye slicing) and illogical progression of disturbing and symbolic images. It operates purely on dream logic. Think also of the unsettling atmosphere in films by David Lynch, which often feel deeply indebted to Surrealist principles, or the visual inventiveness of Michel Gondry's music videos.

In music, while perhaps less direct than in visual arts or film, Surrealism's emphasis on the irrational, the subconscious, and unexpected juxtapositions influenced experimental composers and musicians. Figures like Erik Satie (though pre-dating the official movement, his unconventional approach resonated with Surrealists) and later, artists exploring chance operations (like John Cage) or dream logic in their compositions, show echoes of Surrealist thought. The movement's spirit can be felt in genres that prioritize atmosphere, unconventional structure, or the exploration of psychological states.

In theatre, figures like Antonin Artaud, though later breaking with Breton, were profoundly influenced by Surrealist ideas, particularly the focus on the subconscious and challenging conventional reality, leading to concepts like his "Theatre of Cruelty" which aimed to shock the audience into confronting their primal instincts.

Photography also embraced Surrealism, with artists like Man Ray experimenting with techniques like solarization (partially developing a print to reverse tones) and rayographs (placing objects directly onto photographic paper and exposing it to light) to create uncanny and abstract images that distorted reality and revealed hidden forms. His iconic Le Violon d'Ingres, a photograph of a woman's back with f-holes drawn on it, is a simple yet powerful Surrealist transformation of the human body into a musical instrument. Photographers like Claude Cahun used the medium to explore fragmented identity through staged self-portraits. Lee Miller's war photography, while documentary, often captured moments of stark, almost surreal juxtaposition.

Surrealist principles also influenced fashion, advertising, and design. Think of Elsa Schiaparelli's famous collaborations with Dalí on fashion items like the 'Lobster Dress' or the 'Shoe Hat', bringing the bizarre and dreamlike directly into wearable art. Even today, you see the echoes of Surrealism in music videos, advertising campaigns that use bizarre imagery, or fashion that plays with unexpected forms and juxtapositions. That slightly unsettling, dreamlike quality? That unexpected pairing of images? That's Surrealism still at play, reminding us that the irrational holds a strange power.

Political and Social Dimensions

Beyond the arts, Surrealism had a strong political dimension. Many early Surrealists were fiercely anti-bourgeois, anti-colonial, and anti-fascist, aligning themselves with revolutionary politics, including communism. They saw the liberation of the mind as intrinsically linked to the liberation of society from oppressive rationalism, convention, and political systems. Figures like Breton were politically active, for instance, signing manifestos against French colonialism and fascism. Their anti-rational stance was inherently a challenge to the established political order, which they saw as built on flawed logic that led to war and oppression. The relationship with the Communist Party was often fraught due to the Surrealists' emphasis on individual freedom and irrationality, leading to expulsions and internal conflicts. They were vocal against colonialism and racism, seeing them as products of the same oppressive rationalism they rejected.

Global Spread

The movement's global spread meant it adapted to local political and cultural contexts. While centered in Paris, Surrealism quickly gained traction internationally. In Latin America, artists like Frida Kahlo and Remedios Varo found a receptive environment, even if their work wasn't always strictly aligned with Breton's definition, drawing on indigenous mythologies and local realities that often blurred the lines between the real and the fantastical. In Mexico, Surrealism resonated with the country's rich history of myth and magic, influencing artists beyond Kahlo. The movement also spread to Japan, the Caribbean, and beyond, often merging with local revolutionary or indigenous movements, demonstrating its adaptability and universal appeal. The core Surrealist group's main period is generally considered to be from the mid-1920s through the 1940s, though its influence continued long after, evolving and merging with other movements.

The Lasting Legacy: Why Surrealism Still Matters Today

While the core Surrealist group dispersed or evolved over time, particularly after World War II, the movement's impact on art, culture, and thought is undeniable and continues to resonate. Its influence can be seen in the development of later movements like Abstract Expressionism (through automatism and the focus on the unconscious), Pop Art (interest in popular culture and mass media imagery, often with a surreal twist), and Conceptual Art (challenging traditional notions of art and emphasizing ideas). Surrealism fundamentally changed how artists thought about creativity and the source of inspiration.

Its exploration of the subconscious paved the way for greater acceptance of psychological themes in art and literature. The emphasis on dreams and irrationality influenced fields like psychology and philosophy, contributing to discussions about the nature of reality, perception, and the human mind. The Surrealist challenge to conventional norms also had a lasting effect on social and political thought, encouraging questioning of authority and established systems.

In popular culture, the visual language of Surrealism is ubiquitous, from album covers and music videos to advertising and film special effects. The idea that the bizarre and unexpected can be powerful and meaningful is a direct legacy of the movement. Surrealism gave artists and thinkers permission to embrace the weird, and that permission continues to inspire. The spirit and core principles of Surrealism – the exploration of the unconscious, the embrace of the irrational, the power of juxtaposition, and the challenge to conventional reality – continue to be explored and reinterpreted by contemporary artists across all mediums today.

Finding Surrealism in Your World & My Own Weird Corner

So, is Surrealism still relevant today? Absolutely. Its direct influence might be less visible in mainstream art movements, but its spirit is everywhere. It taught us the power of the irrational, the importance of dreams, and the potential for creativity when we let go of rigid control.

Just look around! You see it in:

- Film: From the dream sequences in Christopher Nolan's Inception to the visual absurdity and unsettling atmosphere of David Lynch's work, filmmakers continue to draw on Surrealist techniques to depict altered states of consciousness and challenge conventional narrative. Think also of the bizarre, symbolic visuals in music videos by artists like Björk or Lady Gaga.

- Music Videos: The often bizarre, non-linear, and highly symbolic imagery in many music videos owes a huge debt to Surrealism. Consider the work of Michel Gondry or the visual style of artists like FKA twigs.

- Advertising: Advertisers frequently use surreal juxtapositions to grab attention and create memorable, if illogical, connections between products and desires. Think of those ads that make absolutely no sense but stick in your head – often a direct descendant of Surrealist object theory.

- Fashion: Designers constantly play with scale, form, and context in ways that echo Surrealist objects and imagery. A dress made of meat? A hat shaped like a shoe? Pure Surrealism. Elsa Schiaparelli's collaborations with Dalí were just the beginning; contemporary designers like Iris van Herpen continue to push boundaries in ways that feel deeply surreal.

- Psychology and Philosophy: Surrealism's exploration of the unconscious continues to resonate, influencing therapeutic approaches and philosophical discussions about the nature of reality and perception.

- Everyday Life: That moment when you see something completely out of place, a strange coincidence, or have a sudden, inexplicable thought – that's a little flicker of everyday surrealism. Like seeing a single, bright red balloon tied to a lamppost on a grey, rainy day. It disrupts the mundane and makes you pause.

And on a personal level, Surrealism encourages us to pay attention to our own inner lives. To notice the strange connections our minds make. To value our dreams, not just as random noise, but as potential sources of insight and creativity. It's a reminder that there's a vast, fascinating landscape within each of us, waiting to be explored. It gives you permission to embrace your own weirdness, a permission that has been vital to my own journey as an artist.

Sometimes I'll be halfway through my morning coffee before I shake off the image of, I don't know, my cat reciting tax law while riding a unicycle made of cheese. It's that feeling, that delightful (or sometimes unsettling) disorientation, that makes me think of Surrealism. This idea of depicting the inner reality, the landscape of the mind and dreams, resonates deeply with my own artistic practice, where I often try to give form to internal feelings and fleeting thoughts. As an artist, I find the core ideas of Surrealism incredibly liberating. While my work might lean more towards abstract art or contemporary art, that permission to explore the illogical, to trust the images that surface from somewhere deep inside, is fundamental to my process. I don't necessarily paint melting clocks, but I often start with a feeling, a color, or a vague shape that comes from that non-rational place. It's about letting the subconscious guide the initial marks on the canvas, much like automatism, before the conscious mind steps in to refine and structure. Sometimes, I'll have a strange, persistent image pop into my head – maybe a specific color combination that feels 'wrong' but compelling, or a shape that doesn't exist in the real world – and I'll just start painting it, trusting that it comes from somewhere meaningful, even if I don't understand it yet. It's like my own little paranoiac-critical method, minus the actual paranoia. It's about systematically exploring those irrational sparks. For example, a recent series of paintings started with the persistent image of floating geometric shapes interacting with organic forms – something that felt completely nonsensical but led to a fascinating exploration of structure and fluidity on the canvas. It's about keeping that 'weird filter' on, even when the world tells you to turn it off.

![]()

My journey as an artist, which you can see a bit of on my timeline, has been about finding my own voice, and part of that is embracing the unexpected connections and visual thoughts that don't always make logical sense. Sometimes, the most compelling pieces come from those moments of allowing the weird filter to stay on. It's about being brave enough to put that 'cheese unicycle cat' thought onto the canvas, in whatever abstract form it takes. If you're curious to see how these ideas manifest, you can explore some of my art for sale. And if you're ever near 's-Hertogenbosch, you can see some of my work in person at my museum – maybe you'll find something there that speaks to your own subconscious!

Key Surrealism Concepts & Terms Summary

Term / Concept | Explanation | Key Figures / Related Ideas |

|---|---|---|

| Surrealism | Art & cultural movement exploring the unconscious mind and dreams to create a 'sur-reality'. | André Breton, Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Sigmund Freud |

| Sur-reality | The synthesis of dream and reality, seen by Surrealists as a higher form of reality. | André Breton |

| Automatism | Technique of spontaneous creation without conscious control, aiming to access the unconscious directly. | André Masson, Joan Miró |

| Paranoiac-Critical Method | Dalí's technique of inducing a state of delusion to systematically interpret ambiguous images. | Salvador Dalí |

| Exquisite Corpse | Collaborative game where participants add to a work without seeing the whole, revealing collective unconscious. | André Breton, Yves Tanguy, Joan Miró, Man Ray (used by many Surrealists) |

| Veristic Surrealism | Depicting dreamlike or irrational scenes with realistic, often academic precision. | Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Yves Tanguy, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo |

| Abstract Surrealism | Using abstract forms and automatist techniques to evoke the feeling/energy of the unconscious. | Joan Miró, Max Ernst, André Masson, Hans Arp |

| Convulsive Beauty | Finding beauty in the unexpected, unsettling, or irrational; moments where the ordinary is disrupted. | André Breton |

| The Uncanny (Unheimlich) | The psychological feeling of something familiar being made strange and unsettling. | Sigmund Freud (concept), applies to many Surrealist works and objects. |

| Surrealist Object | Combining unrelated items to create a new object that disrupts expectations and evokes the uncanny. | Meret Oppenheim, Salvador Dalí |

| Influence of Freud | Psychoanalysis, particularly theories of the unconscious, dreams, id/ego/superego, provided theoretical basis. | Sigmund Freud (psychologist, not artist), central to Surrealist theory. |

| Influence of Dada | Surrealism emerged from Dada's rejection of reason but sought a more constructive exploration of the psyche. | Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara (Dada figures), André Breton (transitioned from Dada) |

| Political Dimension | Anti-bourgeois, anti-colonial, anti-fascist stances; link between mental and societal liberation. | André Breton, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard (early political engagement) |

Diving Deeper into the Dream

Surrealism is more than an art movement; it's a way of looking at the world, a reminder that logic isn't the only lens through which to view reality. It encourages us to pay attention to our dreams, our spontaneous thoughts, the uncanny moments in everyday life. It's permission to be weird, to make strange connections, and to find beauty and truth in the illogical.

Whether you're exploring modern art galleries or just letting your mind wander during your morning coffee, the spirit of Surrealism is there, waiting for you to dive in. It's a call to embrace the mystery, the unexpected, and the wonderfully bizarre landscape of your own mind. It's about finding the 'sur-reality' in your own life and perhaps, like me, letting it fuel your creativity. After all, the most interesting discoveries often happen when you dare to look beyond the obvious.

credit, licence