Richard Prince: Ultimate Guide to His Art & Controversies

Explore Richard Prince, the controversial appropriation artist. This ultimate guide covers his life, Cowboys, Nurses, Jokes, lawsuits, Pictures Generation context & legacy.

Richard Prince: The Ultimate Guide to the Appropriation Artist

Richard Prince (born 1949) is one of the most pivotal, provocative, and controversial figures in contemporary art. An American painter and photographer, he rose to prominence in the late 1970s and early 1980s as a key member of the Pictures Generation. Prince is best known for his radical use of appropriation – taking existing images from mass media and consumer culture and reframing them as his own artwork. His work consistently challenges notions of authorship, originality, and the value of images in a media-saturated world, making him both highly influential and frequently debated.

This ultimate guide delves into the complex world of Richard Prince, exploring his life, his groundbreaking artistic strategies, his most famous bodies of work, the recurring themes he investigates, the controversies surrounding his practice, his significant market presence, and his enduring legacy. Understanding Prince is crucial for understanding key developments in postmodern and contemporary art.

Biography: The Making of an Enigma

Prince's background and early experiences significantly shaped his artistic approach:

- Early Life: Richard Prince was born in 1949 in the Panama Canal Zone, an American territory at the time. This geographically specific, almost liminal birthplace perhaps foreshadowed his later interest in the constructed nature of American identity and imagery. His family later moved to a suburb of Boston.

- New York and Time Inc.: Prince moved to New York City in the 1970s, immersing himself in the burgeoning downtown art scene. Crucially, he took a job in the archives at Time Inc., clipping articles for the company's magazines. This role provided him with direct access to the discarded advertisements and images that would become the raw material for his early work. He began photographing sections of these ads, focusing on recurring motifs like luxury goods, idealized figures, and suggestive glances, removing the original text and context.

- Pictures Generation: By the early 1980s, Prince was exhibiting alongside artists like Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, and Barbara Kruger. These artists, collectively known as the Pictures Generation, shared an interest in deconstructing the images found in popular culture, advertising, and film, questioning their underlying messages and the nature of representation itself. Prince's re-photography became a signature strategy within this critical movement. (Related: Understanding Modern Art).

- Career Development: Throughout the 1980s and 90s, Prince expanded his practice beyond pure re-photography, incorporating text (Jokes), found objects (Hoods), and eventually, expressive painting techniques (Nurses, De Kooning series). He achieved significant critical and commercial success, exhibiting internationally and becoming a highly sought-after figure in the art market.

- Later Life: Prince is known for maintaining a degree of distance from the art world establishment, often working from his studio in Upstate New York. He continues to produce work, often engaging with new forms of media like social media, and remains a subject of intense discussion and debate. His decades-long career reflects the kind of sustained artistic exploration seen in many artists' journeys.

Artistic Style & The Power of Appropriation

Prince's artistic identity is built upon the foundation of appropriation:

- Appropriation Art: This is the practice of borrowing, copying, or altering existing images, objects, or ideas and presenting them within a new artistic context. Instead of creating something entirely "new," appropriation artists manipulate pre-existing cultural material to comment on it, critique it, or explore its hidden meanings. Prince is a master of this strategy.

- Re-photography: Prince's earliest and perhaps most defining technique is re-photography. He would literally photograph existing photographs, often advertisements found in magazines. By cropping, focusing on details, removing text, and presenting these images in a gallery context, he shifted their meaning, highlighting their constructed nature, latent desires, and cultural clichés. Works like the Cowboys series are prime examples.

- Source Material Obsession: Prince consistently draws from the vernacular of American popular culture:

- Advertising: Marlboro cigarette ads, luxury watch ads, fashion photography.

- Magazines: Biker magazines (Gangs), celebrity publications.

- Pulp Culture: Joke books, cartoons (Jokes), pulp romance novel covers (Nurses).

- Americana: Car culture (Hoods), symbols of masculinity and rebellion.

- Social Media: Instagram posts (New Portraits).

- Techniques Across Media: While starting with photography, Prince diversified his methods:

- Painting: Integrating silkscreened text, collage elements, expressive brushwork, often layered over appropriated imagery or book covers.

- Sculpture/Assemblage: Using found objects like fiberglass car hoods, transforming them through painting and context.

- Books: Prince has produced numerous artist's books, often treating the book itself as a medium for sequencing and contextualizing images.

Prince's aesthetic often mirrors the slickness of advertising but can also incorporate deliberate crudeness or painterly "noise," creating a tension between the mass-produced source and the unique art object.

But Why Appropriation? A Moment of Reflection

It's easy to get bogged down in the technical definition, but let's pause for a second. Why this method? When I first encountered Prince's work, maybe like you, I felt a strange mix of recognition and unease. "Haven't I seen this somewhere before?" followed quickly by, "Wait, is this allowed?" That jolt, that questioning, is precisely the point.

Think about it – we swim in a sea of images every day. Ads, social media, movie posters... they shape our desires, our ideas of cool, even our sense of self, often without us consciously realizing it. Prince, by grabbing these familiar images and isolating them, forces us to look again. He's like someone holding up a mirror to the culture that bombards us, asking, "See this? What does it really mean? Who decided this is what a hero/desire/joke looks like?"

It's not about laziness, though critics sometimes throw that word around. It's about engaging directly with the visual language that already exists, turning its own power back on itself. It's a strategy that feels particularly relevant now, perhaps even more than when Prince started. How many images have you scrolled past today without truly seeing them? Prince’s work, fundamentally, asks us to pay attention to the visual noise and question its source and effect. It challenges the very idea of what art is in an age of infinite reproduction.

Major Series and Bodies of Work

Prince's career is often discussed through his distinct and often overlapping series:

- Cowboys (late 1970s onwards): Perhaps his most iconic series. Prince re-photographed advertisements for Marlboro cigarettes, cropping out the branding and text to focus solely on the image of the rugged, heroic cowboy. These works deconstruct the myth of the American West and idealized masculinity as presented through advertising. By removing the product and isolating the archetype, Prince highlights how manufactured this "authentic" American symbol really is. The scale shift—from magazine page to large gallery print—also elevates the mundane ad into something monumental, forcing a different kind of contemplation.

- Gangs / Girlfriends (1980s): Prince appropriated photographs from biker magazines, often focusing on the girlfriends of gang members. These works explore themes of subculture, male gaze, sexuality, and female representation within specific social groups.

- Spiritual America (1983): This work involved the re-photographing of a controversial nude photograph of a young Brooke Shields taken by Gary Gross. It generated significant outrage and was withdrawn from exhibition shortly after its debut, highlighting the provocative nature of Prince's practice and the sensitive issues surrounding image ownership and exploitation.

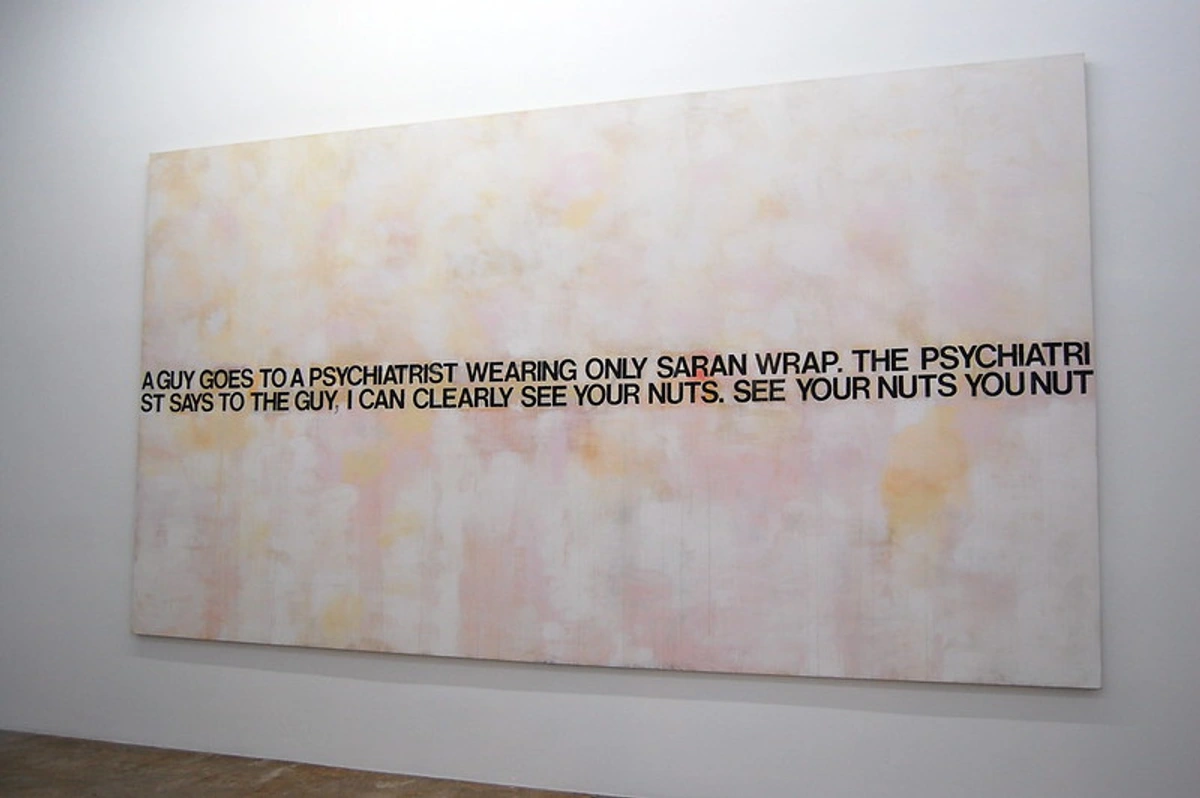

- Jokes (mid-1980s onwards): Prince began silkscreening text-based jokes, often sourced from magazines like The New Yorker or Borscht Belt comedians, onto monochrome canvases. These deadpan paintings remove the context of delivery, forcing viewers to confront the nature of humor, stereotype, and the relationship between text and image in the context of minimalist or conceptual painting. They question what constitutes a "painting" and who "authors" the joke. Seeing one in a gallery is a curious experience – you read it, maybe chuckle, maybe cringe, and then you're left wondering... is that it? The emptiness around the text, the stark presentation, makes the familiar joke suddenly alien, prompting thoughts about social codes, repetition, and why we find certain things funny (or offensive). It's humor stripped bare, laid out for dissection.

- Checks (late 1980s): Integrating canceled personal checks (often bearing celebrity signatures obtained through collecting) into abstract compositions, playing with notions of value, fame, and the everyday object as art material.

- Hoods (late 1980s onwards): Prince acquired fiberglass hoods from muscle cars and treated them as sculptural supports for painting, often applying abstract gestures or referencing minimalist aesthetics. They connect to car culture, masculinity, and the readymade tradition.

- Nurses (early 2000s onwards): Prince took covers from pulp romance novels featuring nurses, scanned them, transferred them to canvas via inkjet, and then heavily overpainted them with thick, often expressionistic layers of acrylic paint. The nurses' faces are often obscured by surgical masks (sometimes painted on by Prince) and dripping paint, exploring themes of eroticism, stereotype, concealment, and the act of painting itself. These works juxtapose the cheap, disposable nature of the pulp source with the high-art tradition of expressive painting. The layers of paint feel almost like a violation or a shrouding of the original image, adding a layer of darkness or mystery to the often-kitschy source material.

- De Kooning Paintings (2000s): Works that combine elements of Prince's re-photography (often depicting female figures) with vigorous, abstract brushwork reminiscent of Willem de Kooning, creating a collision between mass media imagery and high art painterly gestures.

- New Portraits / Instagram Series (2014 onwards): Prince printed out screenshots of other users' Instagram posts (often young women, sometimes celebrities), added his own cryptic comments below, and presented them as large-scale inkjet prints. This series ignited fresh controversy regarding copyright, consent, and appropriation in the digital age, commenting on social media performance, online identity, and the value placed on digital images. It felt like Prince adapting his core strategy for the 21st century – if magazines were the source material repository before, Instagram is the new archive of public/private personas. The minimal intervention (a screenshot, a comment) pushed the boundaries of "transformation" even further, sparking heated ethical debates.

Richard Prince and the Collector's Impulse

Beyond simply using found images, Richard Prince is a voracious collector. This impulse seems deeply intertwined with his artistic practice. Think about his source materials: pulp novels, joke books, biker magazines, celebrity memorabilia, even canceled checks. These aren't just random grabs; they represent specific veins of American culture, often the overlooked, the ephemeral, or the slightly disreputable.

His Time Inc. job wasn't just access; it was training in archiving and categorizing the detritus of popular culture. He learned to see patterns, repetitions, and underlying themes in the flood of images. This collector's mindset – the desire to gather, sort, preserve, and re-contextualize – informs series like the Jokes (collecting humor archetypes) or the Checks (collecting fragments of fame).

You could argue that his appropriation is a form of collecting, but one where the collected item is transformed and re-presented as art. He's not just hoarding; he's curating and commenting on his finds. Walking through an exhibition of his work can feel a bit like wandering through a meticulously organized, yet deeply strange, archive of cultural fragments. It highlights how artists often build their worlds from the things they gather around them, whether physical objects or digital images – a process that reflects a personal journey through influences and interests.

Key Themes Explored

Across his diverse series, Prince consistently probes several interconnected themes:

- Authorship and Originality: Who owns an image? What does it mean to be an "original" creator in a world saturated with pre-existing imagery? Prince's entire oeuvre questions these fundamental assumptions of art history.

- Consumer Culture and Advertising: He dissects the language and allure of advertising, revealing its constructed nature and its role in shaping desires and identities.

- American Identity and Mythology: Through Cowboys, cars, and subcultures, Prince explores and often critiques quintessential American myths and archetypes.

- Sexuality, Desire, and Gender: His work frequently engages with representations of sexuality, often highlighting stereotypes, the dynamics of the gaze (male and female), and the commodification of desire.

- Fiction vs. Reality: Prince delights in blurring the lines, using images that are already fictionalized (like ads or pulp covers) and further manipulating them, suggesting that our understanding of reality is heavily mediated by images.

- Collecting and Classification: His background as an archivist and his own collecting habits (jokes, books, memorabilia) inform his practice of gathering, sorting, and re-presenting cultural artifacts.

The Pictures Generation Context

Richard Prince is intrinsically linked to the Pictures Generation, a group of artists who emerged in New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

- Core Idea: These artists reacted against the perceived exhaustion of Minimalism and Conceptual Art by turning their attention to the power and pervasiveness of mass media images. They used photography and appropriation not necessarily to create new images, but to critically analyze existing ones from advertising, film, television, and print media.

- Key Peers: Alongside Prince, prominent figures include Cindy Sherman (exploring identity through staged self-portraits resembling film stills), Sherrie Levine (re-photographing works by famous male artists to question authorship), Barbara Kruger (combining found images with bold text overlays), and Louise Lawler (photographing art in institutional and private contexts).

- Prince's Contribution: Prince's specific contribution was his focus on re-photography as a primary medium and his deep dive into specific veins of American popular culture, particularly advertising and subcultures, exposing their underlying codes and desires. Their work paved the way for much of contemporary art's engagement with media.

Appropriation, Copyright, and Controversy

Prince's career has been punctuated by legal battles and ethical debates surrounding his use of appropriation.

- The Challenge: By taking existing images, especially copyrighted ones, and presenting them as his own work (often selling for vastly more than the original source), Prince directly challenges copyright law and notions of fair compensation for creators.

- Cariou v. Prince (Landmark Case): Photographer Patrick Cariou sued Prince in 2008 for copyright infringement over Prince's use of Cariou's photographs of Rastafarians in his Canal Zone series. Initially, a lower court ruled against Prince. However, on appeal in 2013, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals largely reversed the decision, finding that most of Prince's alterations constituted "transformative use" under the doctrine of fair use. This meant that Prince's work sufficiently altered the original's meaning, message, or aesthetic to be considered a new work, not merely a copy. This ruling has been highly influential (and debated) in subsequent copyright cases involving appropriation art.

- Instagram Backlash: His New Portraits series (2014) provoked widespread criticism, particularly from the individuals whose Instagram photos he used without permission (and allegedly without significant alteration beyond cropping and adding comments). While some sales were canceled and the ethics heavily questioned, major legal challenges similar to Cariou's did not immediately materialize, partly due to the complexities of Instagram's terms of service and the different nature of the source material.

- Ongoing Debate: Prince's work continues to fuel discussion about the boundaries of appropriation, fair use, artistic freedom, digital ownership, and ethical responsibility in contemporary art. Understanding these controversies is essential to grasping his impact.

The Two Sides of the Controversy Coin

It's worth explicitly laying out the core arguments that swirl around Prince:

- Arguments For (The "Transformative Use" Camp):

- Commentary & Critique: Prince isn't just copying; he's using the original image to comment on media, culture, authorship, or the source itself. His changes (cropping, scale, context, layering) create a new meaning.

- Artistic Freedom: Artists need the freedom to engage with and reference the culture around them, including existing images. Overly strict copyright could stifle critical artistic practices.

- Fair Use Doctrine: Copyright law includes "fair use" precisely for purposes like criticism, comment, and scholarship, which proponents argue covers much appropriation art. The Cariou decision leaned heavily on this.

- Arguments Against (The "Infringement & Ethics" Camp):

- Lack of Consent/Compensation: Prince often uses images without asking the original creator (photographer, Instagram user) and without offering payment, while his own works sell for millions. This feels fundamentally unfair to many.

- Minimal Transformation: Especially with works like New Portraits, critics argue the changes are too slight to be truly "transformative." Is adding a comment and blowing up an Instagram photo really creating a new work?

- Power Dynamics: A famous, wealthy male artist appropriating images, often of young women or less powerful creators, raises ethical red flags about exploitation and punching down.

- Potential Harm: Using someone's personal photo without permission can feel like a violation of privacy or misrepresentation.

There's rarely an easy answer, and where one draws the line often depends on the specific work and personal values. But acknowledging both sides is key to understanding why Prince remains such a lightning rod. Does the debate sometimes obscure the art? Maybe. Or perhaps the debate is part of the art's effect.

Market Presence and Collecting Richard Prince

Richard Prince is a major force in the contemporary art market.

- Blue-Chip Status: He is considered a "blue-chip" artist, meaning his work is highly valued, sought after by major collectors and institutions, and generally seen as a stable (though expensive) investment within the art world. Understanding art prices for artists like Prince involves tracking auction results, gallery representation, and critical reception.

- High Auction Prices: His works, particularly paintings from the Jokes and Nurses series and early Cowboys photographs, regularly command prices in the millions of dollars at major auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie's. He is consistently ranked among the top living artists by market value.

- Gallery Representation: Prince has been represented by some of the world's most powerful contemporary art galleries, including Gagosian and Gladstone Gallery, which manage sales of his new work and significantly influence his market.

- Collecting Prince: Acquiring significant unique works requires substantial resources and access, often through galleries or the secondary market at auction. Prints, photographs in editions, posters, and artist's books offer more accessible (though still often expensive) entry points for collectors. Given his methods and the related controversies, provenance (history of ownership) and authentication are particularly crucial when considering a purchase. It's vital to research the specific work and its history before buying, perhaps more so than with artists whose work doesn't engage appropriation so directly. Distinguishing between unique works and editioned prints is key. Exploring options to buy art prints online might yield some Prince editions, but always verify authenticity.

Influence and Legacy

Richard Prince's impact on the trajectory of art since the 1980s is profound:

- Legitimizing Appropriation: He was instrumental in establishing appropriation as a central and critically accepted strategy in contemporary art practice.

- Critique of Media Culture: His work provides an enduring critique of how mass media, advertising, and popular culture shape our perceptions, desires, and identities.

- Questioning Authorship: Prince fundamentally destabilized traditional notions of the artist as a sole creator, highlighting the collaborative and borrowed nature of culture.

- Influence on Later Artists: Countless younger artists working with found imagery, digital culture, branding, and critiques of representation owe a debt to Prince's pioneering work.

- Provocateur Role: He embraced the role of the artist as provocateur, using his work to spark debate and challenge viewers' assumptions about art, value, and ownership. His career arguably follows a path outlined in the broader history of art, where artists continually push boundaries.

Where to See Richard Prince's Art

Prince's work is held in the permanent collections of most major modern and contemporary art museums worldwide:

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Tate Modern, London

- Centre Pompidou, Paris

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

- Check listings for other top museums for modern art.

He is also regularly featured in exhibitions at major commercial galleries globally, particularly Gagosian Gallery and Gladstone Gallery. Seeing the work in person, surrounded by other art or in a dedicated show, often provides a different impact than seeing reproductions online.

Understanding and Appreciating Richard Prince

Approaching Richard Prince's work requires a willingness to engage with complex ideas:

- Context is Everything: Understand the source material Prince is appropriating. Knowing the original ad, joke, or photo is key to understanding his intervention.

- Focus on the Concept: Often, the idea behind the work (questioning authorship, critiquing media) is as important, if not more so, than the visual object itself. Learning how to read a painting in Prince's case involves reading the concept.

- Embrace Ambiguity & Provocation: Don't look for easy answers or comfortable aesthetics. His work is often intentionally slippery, challenging, and unsettling.

- Consider the Transformation: How has Prince altered the source image? Through cropping? Re-photography? Painting over it? Adding text? These interventions are where his "artistry" lies.

- Acknowledge the Controversy: Grappling with the ethical and legal questions surrounding his work is part of engaging with it fully. It provides potent art inspirations for debate.

Okay, But How Do I Look at It? A Practical Approach

Let's say you find yourself face-to-face with a Richard Prince piece in a gallery. Maybe it's a Cowboy or a Nurse. It can feel... intimidating? Underwhelming? Confusing? Here’s a non-expert, human way to try and engage:

- Just Look First: Forget the label, forget the controversy for a minute. What do you actually see? Colors? Textures (or lack thereof)? The scale? How does it feel hanging there on the wall? Slick? Crude? Familiar? Strange?

- Recognize the Source (If You Can): Does it ring a bell? Marlboro ad? Pulp novel? Instagram feed? That click of recognition is Step One of Prince's game. If you don't recognize it, that's okay too – sometimes the type of source is enough (generic ad, cheesy joke).

- Spot the Difference: Now, think about the original (or the idea of the original). What did Prince do?

- Crop? What did he cut out? What did he focus on? (e.g., Cutting the Marlboro text makes the Cowboy the subject, not the cigarette).

- Scale Change? Blowing up a small ad or screenshot makes it confrontational, almost absurd.

- Added Paint/Text? How does the messy paint interact with the smooth print underneath in a Nurse? Does the deadpan text of a Joke clash with the serious "painting" format?

- Removed Context? Taking an image out of a magazine and putting it on a gallery wall changes everything. Why this image?

- Ask "Why?": Why this source? Why these changes? What might Prince be trying to get you to think about? (Refer back to the Key Themes). Is it about masculinity? Desire? How media manipulates us? The silliness of art itself? There isn't always one right answer. Sometimes the question is the answer.

- Check Your Gut: How does it make you feel? Amused? Annoyed? Intrigued? Bored? Uncomfortable? Your reaction is part of the artwork's journey too. Prince often plays on that edge between attraction and repulsion, familiarity and strangeness. Don't dismiss your own response; it's valuable data!

Engaging with Prince isn't about instantly "getting it." It's more like wrestling with it. And sometimes, the most interesting art is the kind that leaves you with more questions than answers.

Conclusion

Richard Prince remains a vital and often vexing force in contemporary art. Through his relentless appropriation of American cultural imagery, he has forced crucial conversations about originality, authorship, and the pervasive influence of mass media. His work, from the iconic Cowboys to the controversial New Portraits, continues to reflect and refract our complex relationship with images in the modern world. While debated and legally challenged, his strategies have irrevocably shaped the landscape of art over the past four decades, securing his legacy as a defining artist of the Pictures Generation and a sharp, enduring commentator on contemporary life.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- What is Richard Prince best known for? He is best known for his pioneering use of appropriation, particularly his re-photography of advertisements (like the Cowboys series) and his text-based Jokes paintings and controversial Nurses and New Portraits series.

- Is Richard Prince's appropriation legal? It's complicated. The legality often hinges on the concept of "fair use" under copyright law, specifically whether Prince's work sufficiently "transforms" the original source material. The landmark Cariou v. Prince case found many of his works transformative, but the issue remains highly debated and context-dependent, especially with newer works like the New Portraits.

- Why is Richard Prince's work so controversial? His work is controversial primarily because he directly uses other people's images (sometimes copyrighted, sometimes personal photos from social media) without permission, raising fundamental questions about authorship, originality, copyright, consent, and artistic ethics. The high prices his appropriated works achieve often add fuel to the debate.

- Is Richard Prince part of the Pictures Generation? Yes, he is considered a central figure of the Pictures Generation, a group of artists who emerged in the late 1970s/early 1980s and critically engaged with mass media imagery through techniques like appropriation.

- What are Richard Prince's most famous series? His most recognized series include the Cowboys, Jokes, Nurses, Gangs/Girlfriends, Hoods, and the New Portraits (Instagram series).

- How much does Richard Prince's art cost? Richard Prince is a blue-chip artist, and his unique works (paintings, sculptures, early photographs) typically sell for hundreds of thousands to several million dollars at auction and through major galleries. Prices are influenced by series, size, date, condition, and provenance. For more on valuation, see understanding art prices.

- Where can I buy Richard Prince's art? Unique works are primarily sold through top galleries like Gagosian or Gladstone, or at major auction houses (Christie's, Sotheby's). Editioned photographs, prints, posters, and artist's books are more accessible (though still often expensive) and can be found through specialized print dealers, galleries handling editions, and auctions focused on prints and multiples. Due diligence regarding authenticity and condition is essential, regardless of the price point. Explore options for buying art, including prints that may be available online.

- What is "re-photography" in the context of Richard Prince? Re-photography for Prince specifically means photographing an existing photograph, usually from a magazine advertisement. He didn't just scan or copy; he used his camera to frame, crop, and capture the image again, often resulting in subtle shifts in focus, color, and grain, before presenting it as fine art.

- Did Richard Prince invent appropriation art? No, appropriation has roots much earlier in art history (think Duchamp's readymades or collage). However, Prince was a key figure in popularizing and legitimizing appropriation, particularly through photography, as a central strategy within postmodern and contemporary art during the late 1970s and 1980s, especially within the Pictures Generation.