Cindy Sherman: Identity, Self-Portraiture & Art's Unsettling Mirror

Dive into Cindy Sherman's iconic photography: a personal exploration of identity, performance, and societal roles. Discover her critique of archetypes, the male gaze, and lasting influence on contemporary art.

Unpacking Cindy Sherman: A Personal Deep Dive into Identity and Art

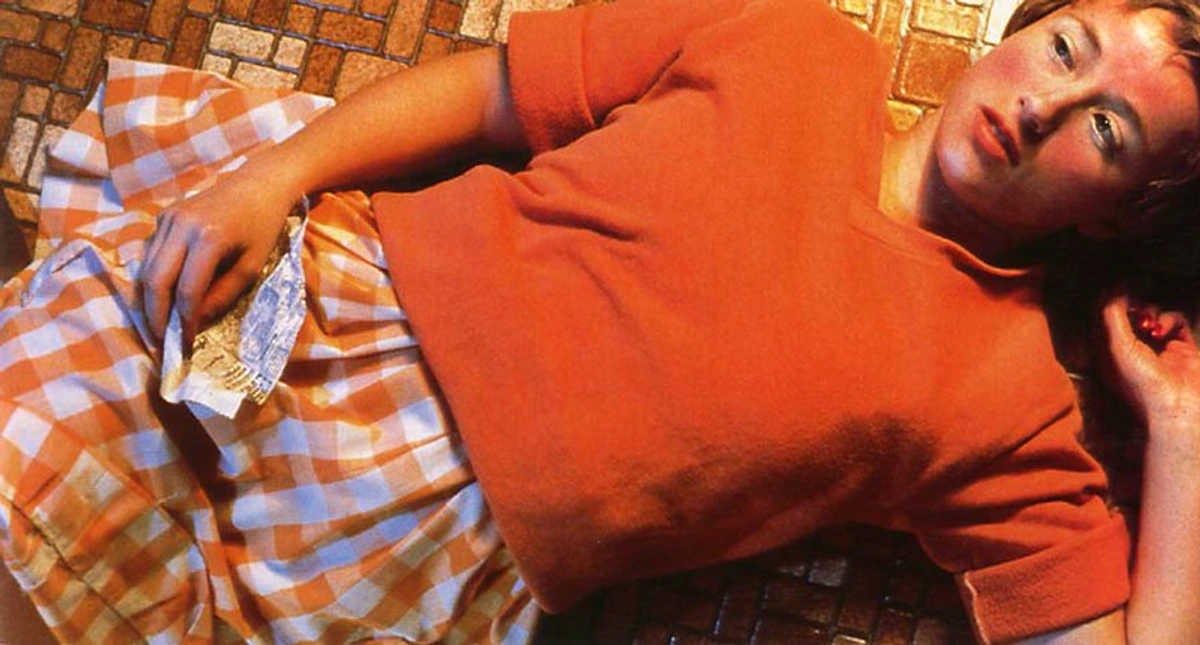

What truly defines 'you'? Is it an inherent core, or a collection of roles, perceptions, and performances? Sometimes, you stumble upon an artist whose work just... gets you. Not in a cozy, comforting way, but in that unsettling, 'oh, you see it too?' kind of way, like a quiet echo in your own psyche. For me, that artist is undeniably Cindy Sherman. I still remember the visceral jolt the first time I saw one of her Film Stills in a book – perhaps 'Untitled #21,' the blonde bombshell on the roadside, evoking a sense of vulnerability or flight, or 'Untitled #96,' the lonely housewife in the kitchen. These small, intimate black-and-white photographs of a solitary figure, often with a look of vague anxiety, created an immediate sense of unease that pulled me in. It was like looking at a funhouse mirror that somehow managed to show me a truth about myself, even though the distorted reflections were entirely of someone else. It wasn't just unease; it was a sudden, quiet question: 'Have I felt that exact way before, even if I couldn't name it?' So, let's dive in and explore the layers of her iconic series, see how her profound influence ripples through art, and connect her insights to our own lives and creative journeys, because her work truly is about the endless performance we all engage in, sometimes consciously, often not. And boy, does she nail the raw, unsettling truth of performance. Frankly, trying to capture her immense impact in words feels a bit like trying to photograph smoke, but here we go anyway, delving into her entire, fascinating career.

Who is Cindy Sherman, Really? (And Why Does She Matter to Me?)

Cindy Sherman, born in 1954 in New Jersey, later studied at Buffalo State College, where the burgeoning conceptual art movement profoundly influenced her. Even as a child, Sherman was drawn to disguises, costumes, and role-playing – a nascent fascination that would later blossom into her iconic transformations. Perhaps it was this innate curiosity, coupled with an early exposure to avant-garde film and photography from figures like Hans Bellmer (known for his unsettling doll photographs exploring the grotesque and uncanny body, often blurring lines between human and object) or Claude Cahun (whose self-portraits profoundly explored gender identity, fluidity, and performance through radical transformations), and a deep fascination with Hollywood's glamorous yet often reductive archetypes and narrative cinema, that honed her unique observational eye and performative inclination. These artists, through their radical approaches to the figure and self, laid a subconscious groundwork for Sherman's own fearless embrace of disguise and the constructed self. Unlike traditional self-portraits by artists like Rembrandt or Frida Kahlo, which often aim to reveal an inner world or physical likeness, Sherman uses herself as a blank canvas, completely disappearing into countless characters. She transforms herself into various archetypes – often unsettling, sometimes mundane, always thought-provoking. She’s the ultimate chameleon, but the real magic is that it's never really her you're looking at, but a representation of something much larger – society’s expectations, the gaze of the media, our own internal narratives. It makes you wonder: how much of 'me' is actually 'me,' and how much is a performance for the various audiences in my life, even when I'm alone? She physically alters her appearance to such an extent that she becomes utterly unrecognizable, embodying the complete dissolution of her own identity into the character. It makes me tired just thinking about the sheer effort of those transformations, like trying to get my hair to cooperate on a humid day, but for art! This transformation allows her to embody 'everyone else' or 'no one specific,' inviting you to project your own understanding onto the constructed facade.

Her process, where she's photographer, model, stylist, and makeup artist all rolled into one, is a testament to her singular vision and deeply solitary method. I imagine her working alone in her studio, perhaps with a remote shutter release and no assistants on set for the actual shoot, a chaotic explosion of wigs, props, and half-eaten sandwiches, all in service of that singular vision. It’s a bit like when I'm trying to figure out a new painting – sometimes I just have to put on all the hats myself to get it just right. It’s messy, it's personal, and it's exhilarating. And in that solitary space, crafting these varied selves, there's an intimacy and control that makes her exploration of identity even more potent, unlike the often collaborative nature of other art forms. This deeply personal method, while singular, places her firmly within conceptual art, a movement where the idea behind the work is more important than the finished art object itself. Her deliberate transformation, focusing on the concept of identity and societal roles rather than a literal self-portrait, is a prime example of this. For me, it's like obsessing over the concept of a piece – the emotional resonance or the intellectual question it poses – long before touching a brush to canvas, letting the concept guide the form rather than the other way around.

Her emergence in the late 1970s positioned her at the forefront of the Pictures Generation, a group of artists who critically examined how mass media images shape our perceptions and construct reality. At the time, photography was often primarily regarded as a documentary tool or for commercial use, rather than a fine art medium capable of deep conceptual exploration. This context makes Sherman’s radical conceptual approach to photography even more groundbreaking. This movement was deeply intertwined with postmodernism, which questioned grand narratives and embraced skepticism towards objective truth. A key strategy of postmodern artists like Sherman was appropriation, where artists take existing images or objects and recontextualize them to create new meaning, often to critique mass media or established cultural norms. Simultaneously, feminist art challenged patriarchal structures and gave voice to women's experiences. Sherman's work, by deconstructing media stereotypes, perfectly embodied this critical spirit, cementing her place as a pivotal figure in contemporary art. She truly redefined the possibilities of photography as a critical art form, becoming a cornerstone in the world of famous contemporary art.

The Unseen Layers: Diving into Her Iconic Series

Ready to peel back the layers? Cindy Sherman’s career is a fascinating progression through different series, each exploring new facets of identity and representation. Each distinct series marks a deliberate artistic evolution, a continuous pushing of boundaries and deeper introspection into the human condition. It’s like watching someone meticulously peel back the layers of an onion, except the onion is humanity, and she’s holding the camera, revealing not just superficial beauty, but often uncomfortable truths. To truly appreciate her genius, let's journey through her most pivotal series, each a profound exploration. To provide a quick roadmap through her diverse output, here's an overview of her most significant series:

Series | Dates | Key Themes | Visual Aesthetic/Look |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untitled Film Stills | 1977-1980 | Female archetypes, media representation, constructed identity | Gritty B&W, cinematic, ambiguous |

| History Portraits | Late 1980s | Challenging art historical canon, reinterpretation, humor | Humorous, deconstructive, painterly, prominent color |

| Disasters & Fairy Tales | Late 1980s-early 1990s | Grotesque, unsettling narratives, dark fantasy, abjection | Distorted, visceral, often disturbing, simulated bodily fluids |

| Sex Pictures | 1990s | Taboos, sexuality, objectification, abjection | Explicit, unsettling, artificial (dolls/prosthetics) |

| Fashion Series | Various | Critique of commercialism, superficiality, industry gaze | Critical, revealing, often awkward |

| Headshots | 2000s | Commercial pressures, aging, authenticity, digital self | Heavily made-up, desperate, larger scale |

| Society Portraits | 2000s | Societal pressures, aging, status, performance of self | Lavish, often grotesque, poignant |

| Clowns | 2000s | Masks, forced merriment, underlying despair, performance | Paradoxical, eerie, exaggerated |

| Social Media Series | 22010s-Present | Digital identity, filtered selves, online performance | Exaggerated, highly filtered, contemporary |

Film Stills: The Archetypes We All Play

Her breakthrough came with the Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980), a prolific series of 69 black-and-white photographs where she poses as various female archetypes from B-movies or film noir – a genre known for its cynical tone, femme fatales, and dark, shadowy cinematography. The series immediately cemented her status as a crucial voice in contemporary art, challenging conventional notions of identity and representation by demonstrating how identity is fluid, constructed, and often mediated by external societal and media forces, rather than being an inherent, fixed concept. Critics immediately hailed it as a groundbreaking examination of media's influence and the performative nature of gender. Think damsels in distress, seductive femmes fatales, or lonely housewives like in Untitled #96. These works, often relatively small in scale (typically 10x8 inches), draw the viewer closer, creating an intimate, almost voyeuristic experience, forcing a direct confrontation with the staged ambiguity. It's uncanny how familiar these characters feel, even though they're entirely fabricated. The genius lies in their ambiguity – the narrative is never fully explained, forcing you, the viewer, to fill in the blanks, to project your own anxieties or desires onto these staged moments. It makes me think about how many of the roles I play day-to-day are influenced by the movies and TV shows I consume – like that time I accidentally adopted a dramatic sigh from a French film just to get a coffee order right. Are we all just living out bad scripts, unconsciously mimicking what we've seen?

Disasters & Fairy Tales: Beyond the Pretty Picture

Later, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Sherman ventured into more grotesque and unsettling territory with her Disasters and Fairy Tales series. Often exhibited together as a powerful, unsettling duo, this marked a deliberate and bold shift, a clear artistic evolution beyond the glamorous facades of the Film Stills. It was perhaps a response to the very success and critical analysis of her earlier work, or simply a desire to push boundaries further and explore the darker, uncomfortable aspects of human experience that lie beneath the surface of popular culture—a testament to her fearless artistic spirit. These works were created during a period of significant cultural shifts, including the AIDS crisis, and emerged as a direct response to the intense “Culture Wars” in the US, which brought issues of morality, censorship, and the body into sharp public debate, reinforcing their provocative intent. She deliberately moved from the accessible to the grotesque, often employing larger formats than her earlier Film Stills, using elaborate prosthetics, mannequins, and even simulated bodily fluids to force viewers to confront disturbing narratives and the dark side of fantasy, often engaging with the concept of abjection – the psychological process of casting out elements that disturb identity and order, like the repulsive or the uncanny. While some critics were initially startled and even repulsed by the stark departure, many eventually recognized these works as unsettling yet powerful critiques of societal anxieties and the dark underbelly of fantasy, solidifying her reputation as an artist unafraid to challenge and provoke. I can only imagine my own reaction if I'd walked into a gallery cold and seen Untitled #175 (1987), a disturbing tableau featuring a figure amidst debris and vomit, or her unsettling forest scenes, like Untitled #153 (1985), that twist familiar narratives into nightmares. It’s definitely not for the faint of heart, and I remember feeling a genuine shiver looking at some of them. But that's the point, isn't it? She challenges our comfort, forcing us to confront the darker undercurrents of fantasy and reality. It’s a brutal reminder that not everything is as idyllic as it seems, a lesson I often try to weave into my own art, though perhaps with less... blood, and maybe a touch more delightful unease.

Society Portraits & Clowns: The Masks We Wear

In her Society Portraits (2000s), such as Untitled #465 (2007-08), Sherman critiques the aging female elite, using heavy makeup, wigs, and elaborate costumes to create almost caricatured versions of women who are desperately trying to maintain an illusion of youth and status. These works, often presented at a larger scale to emphasize their performative grandeur, brilliantly dissect societal pressures around aging, beauty standards, class, and the art world's own performative elite, revealing the often-painful performance required to maintain an image. Beneath the layers of makeup and carefully constructed facades, there's often a poignant sense of vulnerability, a quiet desperation to cling to a disappearing ideal. It’s brilliant, hilarious, and a little bit heartbreaking all at once. It reminds me of the subtle performance we all engage in, perhaps even just trying to look presentable for a video call, or the careful curation of an online persona. It's exhausting, trying to maintain a facade for unseen audiences. And then there are her Clowns – disturbing, unsettling figures that make you question the nature of joy and despair. In works like Untitled #410 (2000-02), clowns, with their painted smiles, are inherently paradoxical, embodying both forced merriment and underlying sadness or fear. It’s a poignant exploration of the masks we wear, not just for society, but sometimes, for ourselves. Are we ever truly ourselves, or always just playing a part?

Beyond the Archetype: Later Works and Enduring Relevance

Sherman's prolific career continued to evolve, consistently challenging the boundaries of self-representation and societal critique through a continuous and deliberate progression in her approach to self-portraiture and technical methods.

Reimagining History and Challenging Taboos

Her History Portraits (late 1980s) saw her reinterpreting famous paintings from the Renaissance or Baroque periods, often with a humorous or grotesque twist. In works like Untitled #205 (1989), where she transforms into a grotesque Bacchus-like figure with artificial breasts and painted stubble, she challenged the male-dominated art historical canon by inserting herself as a contemporary female artist into historically male-dominated narratives, often with a sly, irreverent humor that poked fun at the very grandeur it mimicked. Crucially, Sherman often employed deliberately cheap or anachronistic costumes and props in these works to further emphasize the artificiality and humor in her critique of historical grandeur and the constructed nature of "authenticity." It was the sheer audacity of it, really – taking these hallowed figures and twisting them into something both recognizable and utterly absurd. While some initial critical reactions were surprise or even shock at this bold departure, the series quickly gained recognition for its witty subversion of art historical norms. As an artist, I sometimes feel that same mischievous urge to disrupt established forms, to wink at tradition while creating something fresh. It's like finding unexpected humor in the sacred. This highlighted the artificiality and constructed nature of historical portraiture itself, poking fun at the supposed grandeur of the old masters. Crucially, in these larger-format works, her use of color became more prominent, adding another layer of theatricality and often an unsettling vibrancy to the staged scenes, deliberately amplifying the artifice.

Later, series like her Sex Pictures (1990s) were even more explicit and controversial. Developed during a time when public discourse around sexuality, censorship, and the body was highly charged, these works resonate with the cultural anxieties of the era. Rather than using human models, Sherman employed medical prosthetics, dolls, and mannequins to construct disturbing tableaux. These pieces, such as Untitled #261 (1992), which depicts a crude, disjointed doll with simulated bodily fluids, were deeply unsettling and intentionally challenged taboos around sexuality and the grotesque. By creating these highly artificial and uncomfortable scenes, she not only challenged taboos but also forced viewers to confront their own discomfort and complicity in the objectification of the body, turning the gaze back on them with unsettling precision, often drawing upon the concept of abjection in their visceral impact. Frankly, viewing some of these pieces felt like a psychological workout – a testament to her fearless pushing of discomfort's boundaries. It's a reminder that true artistic exploration isn't always pretty, and sometimes, you just have to lean into the weird.

Critiquing Contemporary Media and Digital Selves

But what about the screens we stare at every day? How do they shape our identities? Her Fashion Series (1980s and 90s), originally commissioned by magazines, playfully critiqued the fashion industry's gaze and superficiality, often presenting models in awkward or unflattering poses, as seen in Untitled #119 (1983). Her influence also extends beyond photography, notably shaping contemporary fashion photography by injecting a critical, often subversive perspective into a commercial realm that often prioritizes idealized beauty. The Headshots (2000) explored the commercial pressures of portrait photography and the struggle of older women to present themselves authentically, featuring heavily made-up, somewhat desperate characters. Here, the subtle shift in focus to the scale of the works often heightened the sense of intimacy or confrontation, and her eventual embrace of digital manipulation in these and later works marked a significant technical evolution from her earlier analog practice, further emphasizing the constructed, rather than documentary, nature of the images. It reminds me a bit of those days when I try to look effortlessly chic for an online meeting, only to realize I've got paint on my nose – the performance of trying to appear authentic, even when you're anything but.

More recently, she has explored the aesthetics of social media, including heavily filtered selfies and exaggerated poses of older women navigating online identity, such as in her Untitled #574 (2016) or Untitled #602 (2019) series, often referred to as her Social Media Series. These works are particularly compelling as they directly address the modern performance of self in the digital age, a direct evolution of her lifelong exploration of constructed identity, proving her enduring relevance and critical eye on contemporary culture. How much of what we present online is truly us, and how much is a meticulously crafted persona for an invisible audience? This also subtly touches on the fascinating tension between artistic integrity and commercial viability, something many artists, myself included, grapple with as they build a presence. It's a tricky tightrope to walk, trying to stay true to your vision while also, you know, paying the bills.

What Makes a Sherman a Sherman? (And Why Can't I Stop Looking?)

Beyond the shifting appearances, the true power of Cindy Sherman’s work lies in its conceptual depth, its sly humor, and its profound influence on how we understand art and identity. Her meticulous process, acting as photographer, model, and stylist, allows her to fully control the narrative, dissecting the very act of looking and blurring the lines between observer and observed, performer and audience. This deliberate control also challenges notions of authorship and originality, asking whose story is truly being told.

Crucially, Sherman’s work actively challenges the male gaze – that pervasive way women are often depicted in art and media from a masculine, objectifying perspective, reducing them to visual spectacles rather than subjects with agency. It’s like noticing how often female characters in movies are framed purely for aesthetic appeal rather than their thoughts or actions. Sherman subverts this by becoming the object herself, but doing so with agency, transforming the gaze from objectification into critical observation. She makes you acutely aware of your own gaze, of how you consume images, and how your perception is shaped by cultural constructs. It’s like when I catch myself subtly adjusting my posture during a video call, even if I'm the only one on screen, just in case someone might see the recording later – that subtle awareness of being watched, that quiet performance for an unseen audience.

While Sherman's work is widely celebrated, it hasn't been without its critiques. Some have occasionally labeled her work as repetitive due to her consistent use of self-portraiture as a vehicle. Yet, this very consistency is what allows her to meticulously dissect and re-examine the nuances of identity, proving that repetition can be a profound form of exploration rather than a limitation. Other critiques have pointed to a perceived 'coldness' or 'lack of overt emotion' in her characters. However, this detachment is precisely her point: by avoiding overt emotionality, she prevents viewers from empathizing with 'Cindy Sherman' and instead forces them to engage with the archetype and the societal constructs it represents, making the critique all the more incisive. While some call it cold, for me, that very detachment is precisely what makes her work so unsettlingly effective, forcing a different kind of engagement than mere empathy.

Furthermore, while Sherman herself has often refrained from explicitly calling herself a 'feminist artist,' her work is undeniably foundational to feminist art and gender studies. By pioneering the deconstruction of media stereotypes and the male gaze through her transformative self-portraits, she provided critical visual language for understanding and challenging patriarchal representations of women in society and art. Her work gave agency to the depicted female figure, even when she was acting as the subject, shifting the focus from passive object to active performer, thereby offering powerful new avenues for feminist critique. Her immense influence on contemporary art is also reflected in her soaring market value. With pieces fetching millions at auction, she has solidified her status not just as an artistic titan, but also a commercial one. This sustained high market value reflects her undeniable critical acclaim, the enduring interest of collectors, and photography's ascent as a legitimate and highly valuable art form – a shift Sherman herself played a pivotal role in.

Her work also significantly contributed to elevating photography from a mere documentary tool to a powerful medium for conceptual art, questioning its very claim to objective truth and challenging the viewer's own assumptions about what they see. She demonstrated that photographs are constructed realities, not mere reflections of truth, thereby opening doors for countless artists to explore performative and conceptual photography beyond traditional portraiture. She makes you question: what is identity anyway? Is it inherent, or is something we construct, perform, and have projected onto us? For me, as an abstract artist, this translates to the layers I build in my paintings – each brushstroke a choice, each color a persona, each piece a question about the inherent truth of form. Her influence also extends beyond photography, inspiring countless performance artists and those using the body as a medium, to explore themes of identity, gender, and the performative self, often with a similar blend of vulnerability and critique. I often find myself thinking about her approach when I'm developing my own pieces. The idea of capturing an emotion, a feeling, or a moment that resonates beyond the literal subject – that's a goal I constantly strive for in my art for sale.

Sherman's Echoes in My Studio: A Personal Artistic Dialogue

In a strange way, Cindy Sherman’s work resonates with my own artistic journey. Her work isn't just for art historians; it profoundly impacts how I, as an artist, approach my own craft, connecting deeply with my own journey of self-discovery and expression through abstract art. While I don't photograph myself in elaborate costumes (unless you count my painting clothes, which, let's be honest, are a performance in themselves, especially when I'm trying to look 'artistically disheveled' for a gallery opening!), her exploration of constructed identity deeply informs how I approach my abstract art. Just as Sherman layers costumes and personas to create a constructed identity, I layer translucent colors to build a sense of shifting emotion, or use fragmented shapes to hint at the fractured nature of memory, much like her characters hint at unseen narratives. For instance, in my recent 'Echoes' series, the subtle overlays of conflicting hues were a direct nod to Sherman's Clowns series, aiming to evoke that same unsettling paradox of forced cheerfulness over underlying unease, but in a non-representational form. Similarly, when I wrestled with a recent abstract piece, 'Fractured Reflections,' trying to convey the elusive nature of memory through disjointed shapes and overlapping lines, I found myself thinking of Sherman's Film Stills – how she captures a moment of unresolved tension, inviting the viewer to piece together the unspoken narrative. It's about capturing that elusive feeling of self that is always being built and perceived. It's a bit like learning how to abstract art – finding freedom within structure, even when it feels like a chaotic explosion, and sometimes feeling completely lost in the process, wondering if anyone will ever 'get' what I'm trying to say. My journey as an artist, documented in my timeline, has been about finding my own voice amidst all the influences and expectations.

Her bold exploration of the self, even when portraying others, encourages me to be more fearless in my own abstract expressions. It's a reminder that art isn't always about comfort; sometimes, it's about asking uncomfortable questions, poking at the edges of what we think we know. It's often through discomfort that genuine breakthroughs occur, both in art and in life.

FAQs: Burning Questions About Cindy Sherman

You know, sometimes I find myself endlessly Googling an artist, and still have a few lingering questions. So, I figured I'd try to answer some of the ones that always come up when I'm talking about Cindy Sherman.

What medium does Cindy Sherman primarily use?

Cindy Sherman primarily uses photography, specifically self-portraiture. She is known for staging elaborate scenes where she is the sole model, transforming her appearance through costumes, makeup, and prosthetics.

What specific techniques does Cindy Sherman employ in her photographic process, beyond just being the model and photographer?

Cindy Sherman's meticulous process involves extensive pre-production, where she meticulously selects and often customizes costumes, wigs, and prosthetics to transform herself into various personas. She often researches historical periods, film genres, or societal archetypes to inform her character development. On set, she works alone, using a remote shutter release, often experimenting with lighting, angles, and expressions to capture the desired nuance of her characters. She primarily uses analog photography, maintaining a traditional darkroom practice for much of her career, though she has also explored digital manipulation in later works, particularly in her Headshots and social media series, further blurring the lines between reality and artifice. The time spent on a single piece can vary wildly, from a few hours for a simple Film Still to weeks or months for more elaborate History Portraits or Clowns with complex setups and prosthetics.

How does Cindy Sherman choose her characters or develop her personas?

Sherman’s characters often emerge from a deep engagement with media, cultural archetypes, and societal roles. She doesn't usually plan them out extensively in advance, but rather allows them to evolve organically through the process of dressing up and experimenting with props and expressions. Her inspiration can come from film stills, fashion magazines, art history, or social media trends, all filtered through her critical lens. She focuses on embodying the types of characters that populate our collective consciousness, rather than specific individuals, to highlight the constructed nature of identity.

What is the difference between a self-portrait and a Cindy Sherman photograph?

While Cindy Sherman appears in almost all of her photographs, she intentionally doesn't create traditional self-portraits. A self-portrait typically aims to reveal the artist's inner self or actual likeness. In contrast, Sherman uses herself as a 'blank canvas' or a model, transforming into various fictional characters and archetypes. Her goal is not to express her own identity but to critique societal roles, media representations, and the constructed nature of identity itself. She disappears into the character, making the photograph about the archetype, not about 'Cindy Sherman.'

What is Cindy Sherman's most famous work?

Her most famous and influential series is undoubtedly the Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980). These black-and-white photographs depict her in various clichéd female roles from B-movies and film noir, exploring themes of identity, representation, and the gaze.

Why are many of Cindy Sherman's works titled "Untitled"?

Cindy Sherman intentionally titles many of her works "Untitled" followed by a number to avoid imposing a specific narrative or interpretation on the viewer. This artistic choice encourages the audience to actively engage with the image, form their own conclusions, and reflect on the themes presented without being overtly guided. By withholding a descriptive title, she invites deeper personal introspection and highlights the ambiguity inherent in constructed identities.

What is the message behind Cindy Sherman's art?

Sherman's art critiques and explores a wide range of messages, including:

- The construction and fluidity of identity

- Societal roles and gender stereotypes

- The pervasive influence of media and popular culture

- The objectification of women and the 'male gaze'

- The nature of representation and photographic truth

- The performance inherent in daily life

She often uses her transformations to question the authenticity of images and the roles we play.

What is Cindy Sherman's connection to feminist art?

While Cindy Sherman herself has often avoided the explicit label 'feminist artist,' her practice profoundly aligns with and contributes to feminist discourse. Through her radical deconstruction of female archetypes and media stereotypes, she provides a crucial visual critique of the pervasive 'male gaze' in art and popular culture. By embodying and subverting these roles, she empowers the depicted female figure, transforming her from a passive object into an active, critical performer, thereby offering powerful new avenues for understanding gender and representation.

How has Cindy Sherman's work influenced the role of photography in contemporary art and broader artistic practice?

Cindy Sherman revolutionized the perception of photography in contemporary art meaning. Before her, photography was often seen as a documentary tool, aiming for objective truth. Sherman's work, however, fundamentally challenged this notion by staging every aspect of her images, proving that photography could be a powerful medium for conceptual art, deeply subjective explorations of identity, and critical social commentary. She demonstrated that photographs are constructed realities, not mere reflections of truth, thereby opening doors for countless artists to explore performative and conceptual photography beyond traditional portraiture. Her influence extends beyond photography, inspiring countless performance artists and those using the body as a medium, to explore themes of identity, gender, and the performative self.

Has Cindy Sherman received any significant awards or recognitions?

Yes, Cindy Sherman has received numerous prestigious awards throughout her career, solidifying her status as one of the most important contemporary artists. These include a MacArthur Fellowship (often called the "Genius Grant") in 1995 and the Praemium Imperiale for painting (a global arts prize) in 2016. These accolades underscore her immense influence and critical acclaim.

What is the significance of Cindy Sherman's market value?

Cindy Sherman's consistently high market value, with works frequently fetching millions at auction, signifies several things in the art world. Firstly, it solidifies her undeniable critical acclaim and recognition as a contemporary master. Secondly, it reflects the sustained interest of collectors and institutions in her groundbreaking contributions to photography and conceptual art. Lastly, it highlights photography's ascent as a legitimate and highly valuable art form, moving beyond its historical perception as a mere documentary tool, a shift Sherman herself played a pivotal role in. Her commercial success is a testament to the enduring power and relevance of her artistic vision.

What are Cindy Sherman's current artistic activities or recent exhibitions?

Cindy Sherman continues to actively create new work and exhibit globally. While she maintains a degree of privacy regarding her process, her recent series often engage with digital photography, social media aesthetics, and the changing landscape of self-presentation in the digital age. Major galleries like Metro Pictures (her long-time representative) and Hauser & Wirth frequently showcase her new pieces, and large-scale retrospectives of her work are regularly organized by prominent museums for modern art worldwide. It's always worth checking the exhibition schedules of major contemporary art institutions like MoMA, Tate Modern, or The Broad for her latest shows. While Sherman herself doesn't maintain an official artist website (a minor inconvenience for us deep divers!), staying updated on her latest works and exhibitions is best done by following major contemporary art news outlets or the websites of her representing galleries like Metro Pictures or Hauser & Wirth.

Where to Experience Her Work

Cindy Sherman's work is held in major museums and galleries worldwide. Notable institutions include The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tate Modern in London, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Many of these institutions frequently feature her work in their permanent collections or temporary exhibitions, making it accessible to a global audience. Whether you're interested in her early black-and-white Film Stills or her later, more elaborate Clowns, there's likely an opportunity to experience her transformative vision firsthand.

If you're ever near the Den Bosch Museum in the Netherlands, it's a personal favorite of mine and always worth checking their program for contemporary exhibitions! For those seeking more, you might also find relevant information about the best galleries in the US or best galleries in the world. And if you're specifically in the Netherlands, don't miss exploring the best galleries in the Netherlands.

Wrapping It Up: My Continued Fascination

Cindy Sherman's work continues to captivate me, not just as an artist, but as a human trying to navigate the complexities of identity in a world saturated with images. We've explored her groundbreaking Film Stills, her challenging Disasters and Fairy Tales, and her incisive Society Portraits, all revealing how she holds up a mirror, not to her face, but to the collective faces we present to the world, and the silent performances we all enact. Her prophetic vision, particularly evident in her early explorations of constructed identity, feels more relevant than ever in an age dominated by social media filters and AI-generated personas. And for that, I'm endlessly grateful. What masks do you wear, even unconsciously, in your daily life? Her art is a reminder that there's always more than meets the eye, and sometimes, the most profound truths are found in the most unexpected transformations – both in art and in ourselves. And perhaps, in exploring her work, you'll find new ways to unpack your own layers, just as I continue to do through my art, even if it's just trying to decide if my paint-splattered studio clothes are an intentional fashion statement or just evidence of a messy morning. It's all part of the performance, right?