Photography as Fine Art: A Curator's Historical Deep Dive

Join a curator's authoritative deep dive into photography's captivating journey from mechanical marvel to revered art form, exploring pivotal movements, key artists, ethical debates, and its transformative impact from its dawn to the digital age.

Photography as Fine Art: A Curator's Introspective Journey Through History

For this curator, photography's journey from a curious mechanical marvel to an exceptionally essential art form has always been utterly captivating – a path that resonates deeply with their own artistic explorations of form and light. It is a story that truly pulls the curator in, unfolding across centuries, from dark rooms and chemical wonders to the sleek digital realm of today. That initial precision was hailed as a scientific triumph, a perfect instrument for documenting reality. But its path to becoming a respected fine art medium? That, the curator has come to realize, was a complex, often contested ride, fueled by resistance from established art academies and shaped by relentless innovation, philosophical debates, and the sheer vision of artists who saw beyond mere mechanical reproduction. For the curator, tracing this transformative dance—watching photography shed its utilitarian skin and emerge as a powerful, expressive, and vitally important presence in the global art tapestry—is truly fascinating. The article explores the pivotal movements, the fiery debates, and the visionary artists who defined this incredible evolution, while also acknowledging the significant challenges photography faced in gaining artistic acceptance.

The Dawn of Photography: From Camera Obscura to Chemical Wonders

The human desire to capture images is ancient, predating photography by centuries, perhaps most notably seen in the camera obscura. This device, a darkened room or box with a small hole, projected an inverted image onto a surface—a precursor that demonstrated the principles of optics long before chemical fixation was possible. One can only imagine the mid-19th century; the birth of photography must have felt like pure science fiction! A moment promising to completely rewire how humanity saw and recorded the world.

Before Daguerre and Talbot, a lesser-known but equally pivotal figure, Nicéphore Niépce, achieved the first permanent photograph, a heliograph, in 1826 or 1827 – literally "sun drawing." It was a painstaking process, requiring hours, even days, of exposure, but it was there. This initial breakthrough quickly spurred the formation of early photographic societies, like the Calotype Club in Scotland or the Société Française de Photographie. These communities were crucial in fostering photography's initial growth and embedding it in a broader cultural conversation, even beyond the scientific labs. They provided vital forums for enthusiasts and pioneers to share techniques, debate aesthetics, and collectively champion the nascent art.

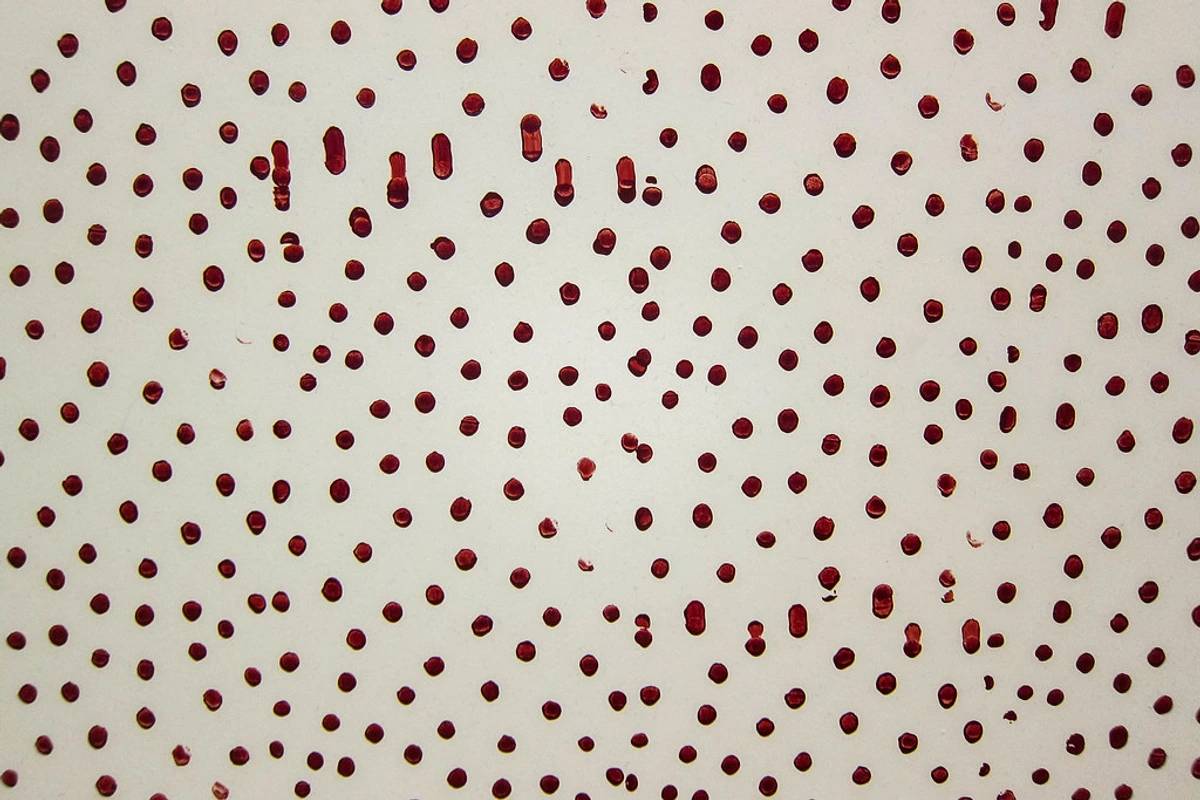

Building on this, pioneers like Louis Daguerre, with his revolutionary daguerreotypes, and William Henry Fox Talbot, with his more reproducible calotypes, unveiled the raw, incredible potential of capturing light itself. Daguerreotypes, though stunningly detailed, produced a unique, fragile positive image that couldn't be easily duplicated. On the other hand, William Henry Fox Talbot's more reproducible calotypes, utilizing paper negatives, allowed for multiple prints – a crucial step towards photography's democratization and challenging its perceived 'rarity' and singular artistic value. At its heart, it was a chemical miracle, often relying on the light-sensitive properties of silver halide compounds to literally etch reality onto a surface. It is often observed how the very limitations and affordances of these early processes humorously laid the groundwork for so many future artistic debates.

This burgeoning science didn't stay locked in artistic debates; it quickly permeated other fields. Photography became an invaluable tool for scientific illustration (documenting botanical specimens or medical conditions), exploration (capturing landscapes and peoples of newly discovered territories), and early forms of journalism (recording historical events or crime scenes). Around this same electrifying period, the Lumière brothers were pioneering motion pictures, adding the dimension of time and narrative to captured reality. This development, closely influenced by the scientific principles of still photography, further blurred the lines between mechanical reproduction and pure art, as photography's close cousin began to move. The sheer newness and electrifying potential of it all made pondering that era a thrilling exercise for the curator, almost like their own first attempts at abstracting reality, wondering where the boundaries even are. And for the wider public, the introduction of cameras like the Kodak Brownie in 1900, with its simple operation and affordable price, further cemented photography's place in the hands of the masses, moving it out of the exclusive realm of specialists and into every home, making everyone a potential image-maker.

Early Skepticism: A 'Soulless Copy'?

Yet, the initial wonder surrounding photography quickly curdled into skepticism for many in the established art world. As with any truly new thing, doubts abounded. And it wasn't just a quiet murmuring. The initial buzz often relegated photography to the 'scientific tool' box, or just a 'convenient way' to document things, snap a portrait, or study cultures. Its very mechanical nature, the fact it was so literal – a direct imprint of reality – led many to question its artistic soul. 'Where's the hand of the artist?' critics argued. 'It's just a soulless reproduction, lacking the manual skill and interpretive genius inherent in painting or sculpture!' It is easy to see why some dismissed it as a fancy photocopier, especially when early results resembled relics from a Victorian attic! This brings to mind Walter Benjamin's concept of the "aura" of an artwork, a unique, almost mystical presence that an original, handmade piece possesses. Benjamin argued that mechanical reproduction stripped away this aura, making photography seem less 'artful' in comparison to painting or sculpture.

Early art critics like Charles Baudelaire even dismissed photography as a 'humble servant of art and science,' explicitly stating it should 'never usurp the place of pure art.' The Royal Academy, a bastion of traditional art, famously refused to exhibit photographs as art, reinforcing this institutional resistance that mirrored similar rejections of nascent art movements at the infamous Salon des Refusés. Even in these early days, the notion of 'truth' in photography was already contested. Take, for instance, the carefully staged battlefield photographs of the American Civil War, used to create dramatic, often propagandistic narratives, or the infamous 'Cottingley Fairies' photographs, which famously duped a nation into believing in literal fairies. Early photographers also retouched portraits to smooth imperfections or enhance features, demonstrating that image manipulation was present long before digital tools. Yet, even in those early, clumsy days, some photographers intuitively understood the expressive power of the lens, composing scenes, playing with light, and quietly infusing their work with an aesthetic intent that, in retrospect, was clearly laying the groundwork for all the wild artistic journeys to come. It is often observed how revolutionary ideas frequently begin as mere curiosities or even outright threats before finding their stride. But how would photography ever overcome such ingrained doubt?

The Pictorialist Movement: Photography's First Artistic Assertion

So, how did photography begin to shed its utilitarian skin and demand a place on the gallery wall? The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought forth Pictorialism, photography's grand coming-out party. This was the first real, organized assertion that photographers were artists too. Pictorialists often looked to painting—their older, more established cousin—for inspiration, eager to capture the dreamy, aesthetic qualities of traditional art, often through allegorical scenes, atmospheric landscapes, and stylized portraits reminiscent of classical painting. It is fascinating how their aesthetic goals often intertwined with movements like Symbolism and Impressionism, aiming for mood and subjective experience over stark realism. The curator acknowledges the appeal of this style, even if it doesn't always align with their personal aesthetic; there’s a certain romance to that soft, ethereal look.

Challenging Established Academies & Techniques

Established art academies, steeped in centuries of painting tradition, often viewed photography with suspicion, if not outright disdain. The resistance stemmed from several factors: photography was seen as a purely mechanical reproduction, lacking the 'hand of the artist' and the interpretative skill inherent in painting. There was also an economic threat to traditional portrait painters, as photography offered a cheaper, faster alternative. Philosophically, many believed art required a transformation of reality, not just a literal copy. Pictorialists directly challenged these notions by intentionally making their photographs appear painterly and evocative, distancing them from mere mechanical records.

They weren't afraid to manipulate their negatives and prints artfully. Techniques like soft focus were common, giving images a wonderfully atmospheric, almost hazy feel. Crucially, they'd use processes like gum bichromate printing, which allowed for incredible manipulation of color and tone, making photographs look less like a cold record and more like an expressive painting. Beyond gum bichromate, they also favored luxurious processes like platinum prints and photogravure, which offered rich tonal ranges and a tactile quality, further distancing their work from mechanical reproduction. It was all about creating images that were intentionally painterly and evocative, rather than just purely descriptive. Take, for instance, Gertrude Käsebier’s famous work, 'The Manger' (1899). This soft-focused, sepia-toned image depicts a mother and child in a scene reminiscent of Renaissance Nativity paintings, clearly emulating the emotional depth and painterly aesthetic of traditional art rather than a stark, documentary photograph. Consider also the work of Alfred Stieglitz during his Pictorialist phase, whose soft-focused landscapes often evoked the mystical qualities of Symbolist painting, or Edward Steichen's early portraits, which sought to convey a sitter's inner life through evocative chiaroscuro and painterly compositions.

While Pictorialists were focused on elevating photography to fine art through painterly aesthetics, it's worth noting that other photographers during this era were also using the medium for vital social documentation, capturing urban life, poverty, and other societal conditions. This parallel development, though distinct in intent, further underscored photography's growing power as a visual language. Figures like Alfred Stieglitz, a true firebrand, tirelessly championed photography as fine art, setting up galleries and publishing influential journals like Camera Work to ensure its beauty was recognized. Julia Margaret Cameron and F. Holland Day were also instrumental, pushing the boundaries of what a photograph could convey. They were, in a way, trying to prove photography's worth by making it feel like what people already understood as art. But what happens when photography stops trying to be painting and embraces its own unique qualities?

Straight Photography: Embracing the Medium's Unique Qualities

Yet, the story didn't end with dreamy soft focus; there is always a pendulum swing in art. As the 20th century rolled on, a complete counter-movement burst onto the scene: Straight Photography. This wasn't about emulating painting anymore. Instead, it was photography looking itself in the mirror and declaring its unique voice. This assertive shift found its philosophical backbone in Modernism, with its emphasis on form, function, and objective representation. It resonated deeply with the dynamism of Futurism and the structural purity of Constructivism, both movements celebrating the machine age and the direct, unembellished depiction of form. This was all about stripping away the unnecessary and getting to the pure essence of the medium, a fascinating parallel to other artistic and architectural shifts of the era, such as the functionalism of Bauhaus architecture or the sleek design ethos emerging across industries.

Pioneers like Paul Strand, with his sharp, unmanipulated cityscapes and portraits, laid crucial groundwork, demonstrating that photography's strength lay in its objective, direct gaze. Other crucial proponents included Charles Sheeler, known for his precise depictions of industrial landscapes, and Edward Steichen, who, after an early Pictorialist phase, embraced sharp focus and unadulterated photographic vision. This move towards smaller, more portable cameras, like the Leica 35mm introduced in the 1920s, also liberated photographers from the studio, allowing for a more immediate engagement with the world, paving the way for candid street photography and photojournalism. This spirit also crystallized in groups like the f/64 Group, a collective of West Coast photographers including Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, who advocated for 'pure' photography, characterized by razor-sharp focus and deep depth of field (f/64 being an aperture setting that allows for maximum clarity and sharpness from foreground to background), and rich tonal values.

The Philosophy of Directness

Straight photographers championed photography's unique, almost brutally honest qualities: razor-sharp focus, an incredible tonal range, exquisite detail, and that unmistakable ability to objectively render reality. They believed that photography's true artistic potential lay precisely in its unadulterated, direct capture of the world. This movement asserted that a photograph, by its very mechanical origin, offered a unique "photographic gaze," an objective, unmediated window into reality that painting, with its inherent subjectivity, simply could not replicate. It was a profound celebration of photographic truth, urging viewers to appreciate the world as seen through the lens, unembellished. One might imagine the audacity: to say, 'Look at reality, in all its sharp, precise glory, and tell me it isn't art!' Their rationale for sharp focus and deep depth of field was to render every detail with utmost clarity, allowing the viewer to engage with the subject's inherent form and texture without interpretive blur or manipulation—to see the world as the camera objectively records it, thereby revealing its profound and often overlooked beauty.

Consider Edward Weston's iconic peppers – those perfectly sculpted forms, the rich textures, the way light plays across them – it was not just a vegetable, but a profound study in form and light. The curator often finds themselves lost in the sheer sensuality of Weston's peppers – a masterclass in finding the extraordinary in the ordinary, a pursuit reflected in their own abstract pieces for sale, where they seek to distill the essence of form and light onto a canvas. Or Ansel Adams, whose mastery of the Zone System allowed him such precise control over tonal values, capturing the stark grandeur of landscapes with a clarity that truly evokes the crisp mountain air. Studying his work, one realizes the immense control possible even in seemingly 'straight' capture—it's a revelation about shaping light, much like a painter shapes color. These artists proved that an unmanipulated photograph could be every bit as compelling and emotionally resonant as any painting or sculpture. This idea of finding such immense beauty in the world, exactly as it is, continues to mesmerize the curator.

This era also saw photography engaging with modern art movements, finding common ground with the fragmented precision of Cubism or the abstract qualities inherent in light and form. It echoed broader abstract art explorations in painting, proving photography's adaptability and intellectual depth. It was a powerful declaration: photography did not need to pretend to be anything else to be art. This movement fundamentally paved the way for photography's broader acceptance and diversification into countless new genres in the coming decades. What new territories would the lens explore next?

Photography's Mid-Century Expansion and Evolution

By the mid-20th century, photography had truly started stretching its legs, its artistic vocabulary expanding beyond what those early pioneers might have imagined. It's fascinating how even documentary photography and photojournalism, initially viewed as purely factual, began to gain serious artistic recognition.

Evolution of Genres & Documentary Power

Take the powerful, often harrowing work of W. Eugene Smith, whose photo essays for Life magazine, like 'Minamata' or 'Country Doctor,' transformed the journalistic image into profound artistic statements, brimming with emotional depth and compositional mastery. The technical development and increasing fidelity of color film in the mid-20th century also marked a significant turning point. Initially often seen as less 'artistic' than the gravitas of black and white, color photography rapidly carved out its own expressive territory, adding another vibrant dimension to the medium's evolving perception and eventually achieving equal artistic standing. Groundbreaking exhibitions, like MoMA's 'The Family of Man' in the 1950s, became a cultural phenomenon, showcasing profound human narratives captured by the lens and firmly asserting photography's capacity to communicate universal human experiences, greatly influencing its public perception as an art form. Photographers like Robert Frank, whose seminal work 'The Americans' (1958) captured the raw complexities of post-war American society—a stark, often unflattering portrayal that challenged idealized national myths and sparked controversy. His deeply personal, expressive vision demonstrated that journalistic intent could indeed coexist with artistic profundity, elevating documentary photography to fine art status. The camera also emerged as a potent tool for social activism, giving voice to the marginalized and driving change, proving its indispensable role not just in aesthetics, but in shaping society itself. And for the curator, that is often where the real magic happens, when art and life truly intersect.

Cross-Medium Influences and Cultural Reach

As photography matured, its embrace of diverse genres further solidified its artistic standing. Landscape photography, once a mere record of topography, evolved into the sublime, spiritual works of Ansel Adams. Portraiture moved from formal sittings to the psychological insights of Yousuf Karsh or Diane Arbus. Still life, traditionally painting's domain, found new precision and abstraction through the lens of Edward Weston. Even abstract photography, experimenting with light, form, and texture, established itself as a potent expressive mode, pushing the boundaries of what a photograph could 'depict'. This expansion of genres meant that there was a photographic equivalent for almost every traditional artistic pursuit, demonstrating its versatility and boundless potential. Beyond fine art, photography also influenced scientific illustration, where its precision allowed for detailed documentation.

But its reach extended further, subtly shaking up other creative realms. Painters like Edgar Degas weren't above using photographic references to study movement and gesture, directly influencing his dynamic compositions of dancers. Similarly, Pablo Picasso, particularly during his Cubist period, engaged with photography's ability to fragment and reassemble reality, exploring multiple perspectives in ways that echoed early photographic experiments in montage. Photography's visual language also deeply impacted advertising and fashion photography, establishing new aesthetic standards and influencing popular culture, blurring the lines between commercial utility and artistic expression. Beyond painting, photography also influenced literature, particularly the "New Journalism" movement, which used detailed, descriptive imagery to immerse readers, much like a photographic essay. It even impacted film cinematography and theatre set design, offering new perspectives on composition, lighting, and narrative structuring. The development of cinema itself, a direct descendant of photographic principles, shows this profound interplay of mediums, each pushing the other forward. It's a vivid reminder of how interconnected all creative endeavors truly are, each borrowing and building upon the other's innovations.

Conceptual Explorations and Critiques

The latter half of the century saw a deepening of conceptual exploration, blurring lines and pushing boundaries. Photography became a playground for artists to explore ideas, identity, and critique, often feeling a little subversive and challenging established norms.

Movements like Surrealism, already playing with dreams and the subconscious, offered photography a new, 'realistic' way to capture the unreal, presenting dreamscapes with photographic veracity. Simultaneously, the polished aesthetic of advertising began to bleed into fine art photography, especially as movements like Pop Art made audiences question consumerism by using commercial imagery in art – a cheeky move, really, taking the everyday and forcing viewers to see it anew.

Early avant-garde movements in Europe, such as Bauhaus and Constructivism, also profoundly influenced photography by emphasizing geometric forms, functional design, and experimentation. This led to innovations like photomontage and experimental typography, pushing photographers to explore abstract compositions and innovative printing techniques, much like how a painter might deconstruct forms. For example, artists like László Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus experimented with photograms (camera-less photographs) and unusual angles, directly applying functionalist and geometric principles to create abstract photographic works. And one should not forget how photography became a crucial tool for documenting ephemeral art forms like performance art. Think of someone like Marina Abramović – her challenging, often physically demanding performances were captured through the lens, allowing those fleeting moments to become lasting works of art, raising questions about presence, time, and documentation itself.

Conceptual photographers used the medium to challenge perceptions, question authenticity, and engage with massive cultural dialogues. For instance, artists like Cindy Sherman, with her 'Untitled Film Stills,' meticulously crafted images that mimicked cinematic tropes. By staging herself as various female archetypes from B-movies and media, she forced viewers to question the stereotypical portrayal of women in media and societal perceptions, revealing the constructed nature of images rather than presenting objective truth. Beyond individual artists, the typological work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, with their systematic photographic series of industrial structures, influenced a generation of conceptual photographers by emphasizing objective documentation as an artistic act – a surprisingly profound statement in its stark simplicity.

This period saw photography embracing the cool precision of Minimalism and the cerebral challenges of Conceptual Art. Artists like Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, and Jeff Wall became huge names, their large-scale, thought-provoking works often using elaborate staging and early digital manipulation to make their points. Take Andreas Gursky, whose large-format photographs of stock exchanges or consumer goods critiqued global capitalism by presenting familiar scenes with unsettling precision, revealing the vast, often alienating structures of modern life.

Photography's Integrated Role in Contemporary Art

Today, photography has fully arrived. It's not just a guest at the fine art party; it's practically hosting it! It's found front and center in major museums, commanding impressive prices at auction houses, and gracing the walls of prominent galleries. It no longer just 'stands shoulder-to-shoulder' with painting and sculpture; it sits comfortably, confidently, alongside all those traditional heavyweights, often even leading the conversation. The digital revolution has been a game-changer, pushing what a photograph can be into truly unprecedented territory. The control over manipulation, scale, and distribution is incredible. This allows contemporary photographers to innovate endlessly, exploring everything from purely documentary approaches to highly constructed and abstract visions. Just as the curator explores new forms and colors in abstract art or creates vibrant contemporary art with paint, photographers are constantly stretching the very limits of visual language. There is even talk of 'post-photography' or 'new media art' now, where the lines between what's a 'photo' and what's purely digital or even sculptural are gloriously blurred. For instance, a contemporary artist might create an immersive digital installation where viewer interaction subtly alters AI-generated photographic landscapes, or utilize augmented reality to overlay ephemeral photographic elements onto physical spaces, pushing the boundaries of photographic experience beyond the static print.

Ethical Considerations and New Horizons

This brings up something the curator often ponders: the ethical considerations. When does representation become manipulation, and where are the lines drawn? It's not a new debate; historically, photography has been used for everything from propaganda to outright fabrication, long before Photoshop. The curator has already noted how carefully staged battlefield photographs of the American Civil War created dramatic narratives, and how the infamous 'Cottingley Fairies' famously duped a nation. Even figures like Stalin's commissars famously retouched photographs to erase political rivals from history, showcasing how images could be used for political control and propaganda by systematically altering historical records and public memory. Now, with the rise of deepfakes, AI-generated imagery, and the ease of digital alteration, these ethical considerations are more pressing than ever, challenging viewers to critically examine what they see. However, digital technology also offers immense positive avenues, democratizing image-making, enabling unprecedented creative freedom, and allowing for new forms of expression like augmented reality photography or interactive digital installations. Furthermore, AI is increasingly being embraced as a powerful collaborator by artists, assisting in generating novel compositional ideas, creating unique textures, or even automating tedious processes, thus freeing up creative energy for conceptual development and pushing artistic boundaries in entirely new directions. And speaking of value, the economic aspect of photography as fine art has soared. The rise of specialized photography galleries and the increasing investment value of photographic prints have created a vibrant collector market, supported by dedicated photography dealers and major auction houses like Christie's and Sotheby's, an entire ecosystem of galleries, and dedicated institutions. Major photography fairs and biennials around the globe, like Photo London or Paris Photo, explicitly celebrate the medium's artistic and commercial vitality, all cementing photography's status not just artistically, but commercially too. For those considering entering this space, a beginner's guide to collecting photography as fine art can be particularly useful.

A Curator's Reflections: Unpacking Common Questions

As the curator reflects on this historical journey, common questions about photography's evolving role in art frequently arise. It’s always fascinating to step back and ponder the nuances of this incredible journey. Here are a few thoughts gathered along the way:

When did photography really start being considered fine art?

People often ask, 'When did photography really start being considered fine art?' And the curator always explains that it was a gradual climb, not an overnight event. For this curator personally, they truly started seeing it as legitimate fine art when first encountering the raw power of Straight Photography, the way it could capture such undeniable beauty without any pretense. That's when it clicked. It really began gaining significant momentum in the late 19th century with the Pictorialist movement, which consciously sought to create artistic images. Then, in the early 20th century, with the bold declarations of Straight Photography, exemplified by groups like the Photo-Secession and figures like Alfred Stieglitz, it truly gained significant traction by asserting its unique aesthetic value. By the mid-to-late 20th century, with major institutional milestones like MoMA establishing a dedicated photography department in 1940 and landmark exhibitions, its place was firmly cemented. This establishment of dedicated museum departments and prominent exhibitions signaled formal, institutional recognition, a significant turning point for the art world. But the debate about its exact boundaries and definitions continues to evolve, reflecting art's inherent fluidity – and that's what makes it exciting!

Who were some of the big names pushing for photography as art early on?

Oh, so many visionaries! If one looks at the Pictorialist camp, powerhouse figures like Alfred Stieglitz, Julia Margaret Cameron, and F. Holland Day were instrumental. They truly fought to make photography feel like 'art' in the classical sense. Then, for Straight Photography, which was a real game-changer – and probably more aligned with what the curator instinctively appreciates – artists such as Paul Strand, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams truly set the stage for what was to come. These are the names that shaped so much of how photographic art is viewed today, and their artistic timeline is definitely worth exploring.

What's the real difference between documentary photography and fine art photography?

Ah, the age-old question! It's a dance the curator has often found themselves in, and honestly, the lines are beautifully blurry. Traditionally, documentary photography aims for factual representation to inform or record events, while fine art photography prioritizes aesthetic and conceptual expression. But here's the kicker: many documentary works are absolutely considered fine art because of their powerful composition, emotional depth, and undeniable artistic intent. Take Dorothea Lange's 'Migrant Mother' (1936) – profoundly documentary, yes, but revered for its artistic composition and emotional resonance. Conversely, much fine art photography can carry strong documentary elements. Ultimately, the curator believes it often comes down to the photographer's intent, the impact on the viewer, and crucially, the context of its presentation. An image presented in a gallery or museum often invites a contemplative, aesthetic engagement, hitting differently than the very same image in a news publication, which might be viewed for information. It’s all about how one is invited to engage with it.

How much does the photographer's intent matter versus viewer interpretation when defining fine art photography?

This is a deep one, and something many artists – including the curator, with their own abstract pieces for sale – grapple with. While the photographer's intent absolutely shapes the creation and initial meaning of a fine art photograph—they are trying to convey something, after all—viewer interpretation is equally crucial. An artist's statement or accompanying text can certainly guide this, offering a valuable lens into their vision. However, art truly lives and breathes in that space between creator and observer. A truly powerful fine art photograph invites multiple interpretations, sparking personal dialogue within the viewer, even if it diverges from the artist's original explicit message. For example, a work like Robert Mapplethorpe's self-portraits may be created with specific intent, yet evoke profoundly varied and personal responses from different viewers, fostering critical dialogue. It's that subjective resonance, influenced by individual experiences and the context of encounter, that makes it art. In the curator's own abstract work, they often start with a concept, but the true 'art' for them is when a viewer finds their own narrative in the colors and forms, making it uniquely theirs. It’s a beautiful, sometimes messy, conversation.

How has digital technology changed the game for fine art photography?

It has been a complete revolution! Digital technology offers artists unprecedented control over image manipulation, color, and composition. It has blown open the doors for creative possibilities, allowing for incredibly intricate, large-scale works and completely new forms of expression. Perhaps most profoundly, it has enabled the democratization of image-making and distribution, putting powerful tools into countless hands. This spans everything from purely digital creations that never touch film to hybrid print forms that push boundaries even further. For the curator, as an artist exploring new mediums, it’s a constant source of inspiration – and sometimes, a bit of head-scratching! It's an exciting, challenging, and constantly evolving landscape.

Conclusion: Photography's Enduring Legacy

Looking back at photography's journey, it’s a compelling narrative of struggle, relentless innovation, and ultimately, magnificent triumph. It’s that same "transformative dance" mentioned at the beginning, a dance that continues to evolve with every click and pixel, firmly cementing photography's status as a profound and multifaceted artistic medium. For the curator and artist, the camera is no longer just an extension of the eye; it's a powerful, almost magical instrument of the artist's vision, capable of profound beauty, incisive commentary, and boundless creativity. This constant push to redefine what is possible, to challenge perceptions, and to find unexpected beauty in the world resonates deeply with the curator's own creative journey – whether they are experimenting with abstract forms in paint, seeking that perfect light with a lens, or curating the collections for the Zenmuseum in 's-Hertogenbosch. The interplay of light, shadow, form, and emotion in photography mirrors this curator's quest to distill complex ideas into vibrant, often abstract, compositions. It's a reminder that even in seemingly disparate mediums, the core artistic impulse to interpret and transform reality remains universal.

As one looks forward, the emergence of AI-generated imagery and advanced immersive technologies promises yet another paradigm shift. Will AI become a collaborator, a challenger, or an entirely new medium? For instance, if an AI can generate photo-realistic images of non-existent scenarios indistinguishable from real photography, it fundamentally challenges the notion of authorship, the role of human perspective, and even the definition of what constitutes a 'photograph.' The conversation around authenticity, authorship, and the very definition of a 'photograph' will undoubtedly deepen. AI's ability to simulate reality, or create entirely new ones, forces a re-evaluation of the human element in creation, fundamentally questioning where the artist's unique perspective and lived experience fit in, and how 'truth' is represented. It echoes the very skepticism photography faced at its inception, but on an entirely new scale. This incredible journey of photography continues to inspire artists, collectors, and art enthusiasts alike, firmly affirming its indispensable, ever-evolving place in the vibrant, glorious tapestry of global art. And frankly, the curator cannot wait to see what it does next, how it will push collective understanding of art, and perhaps even inspiring some new abstract pieces for sale for their next exhibition. It’s a reminder that art, in all its forms, is forever a work in progress, always pushing for 'what’s next'. What will be discovered in the next frame?