Dadaism's Enduring Relevance: Anti-Art, Rebellion, & Its Impact Today

Explore Dadaism's anarchic spirit, its radical challenge to art, and how this anti-art movement from a century ago still shapes contemporary art, digital culture, and my abstract studio.

Dadaism Today: Why This Anarchic Art Movement Still Matters

Sometimes, I look at a piece of art and feel a familiar tingle in my brain—that delightful disruption of expectation that makes me think, "What is this?" Not in a confused way, but in a delighted, utterly perplexed way that takes me back to the wild, chaotic, and utterly brilliant world of Dadaism. This feeling, this delightful perplexity, is precisely what drew me to Dadaism, and it always makes me wonder: why does an art movement from a century ago, born from the chaos of a world war, feel more relevant than ever today? This isn't just a dusty historical footnote; it's a mischievous wink, a gentle (or not-so-gentle) kick in the shins of convention that resonates powerfully in our own fragmented, information-saturated era. Honestly, I love it. It's this spirit of defiant questioning that continues to inspire, even in my own studio, reminding me that art's greatest power often lies in its ability to provoke, to question, and to break free.

What Was Dadaism Anyway? A Beautiful, Destructive Mess

To understand this enduring relevance, we first need to dive into the beautiful, destructive mess that was Dadaism itself. It emerged around 1916 in Zurich, Switzerland, a neutral haven during the ravages of World War I. This was a time of profound disillusionment across Europe, where the perceived rationality and progress of society had instead led to unprecedented global devastation. In this climate of societal collapse, artists and writers—figures like Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, and Hannah Höch—converged in places like the legendary Cabaret Voltaire. Here, they found common ground in their utter rejection of the logic and reason they believed had fueled the catastrophe. Their aim wasn't merely to create new art, but to vigorously challenge and ultimately destroy the very concept of art as it was known by the establishment, particularly the academic, bourgeois, and often nationalist art that seemed complicit in the societal ills they decried. They viewed traditional artistic skill, aesthetics, and the solemn reverence of museums as part of the problem. It was anti-art, anti-logic, and utterly, wonderfully absurd. Tristan Tzara, a central figure and chief provocateur, famously declared, "Dada means nothing." And honestly, who can blame them for embracing nonsense when the world around them seemed to be making no sense at all? Trying to explain it fully often feels like trying to describe a dream – the more you dissect it, the more its essential, delightful chaos slips away. Hugo Ball, for instance, would perform "sound poems" at Cabaret Voltaire, donning fantastical costumes and reciting nonsensical phonetic verses like Karawane – a deliberate assault on language and meaning designed to provoke.

From its neutral haven in Zurich, Dada's anarchic spirit quickly spread its wings, finding fervent proponents in other major cities, each adapting its core tenets to local conditions. In Berlin, fueled by the intense political instability and post-war disillusionment of the Weimar Republic, Dada took on a more overtly political and aggressive edge. Artists like Raoul Hausmann and George Grosz used photomontage to savage the corrupt establishment, creating unflinching satires like Grosz's Pillars of Society. In Cologne, figures like Max Ernst introduced more mystical and surrealist elements, laying groundwork for future movements. In Paris, it was deeply intertwined with literary circles, paving the way for Surrealism as artists like André Breton, initially a Dadaist, began to explore the unconscious mind. And in New York, figures like Marcel Duchamp introduced a more conceptual and intellectual brand of Dada, often focusing on readymades and the philosophical implications of art. The movement challenged not just aesthetic norms but also political, social, and moral conventions, pushing back against the very fabric of accepted reality.

At its core, Dada embraced a radical set of artistic strategies:

Technique | Description | Key Artists/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chance & Spontaneity | Allowing randomness and intuition to guide creation, challenging the artist's control and the idea of deliberate, logical composition. This was a direct defiance of the rational mind, often producing unexpected beauty or delightful chaos. | Tristan Tzara's method of creating poems by cutting up newspaper articles and reassembling them randomly, or Hans Arp's Collages Arranged According to the Laws of Chance, where torn papers fell onto a surface. |

| Readymades | Ordinary manufactured objects elevated to art simply by the artist's designation. This questioned traditional notions of skill, originality, and the very definition of what constitutes art, shifting focus from object to idea and forcing viewers to ponder "What is art, and who decides?". | Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (a porcelain urinal signed "R. Mutt") remains the most iconic and provocative example. Duchamp's choice of a utilitarian, mass-produced object, and specifically a urinal, was a deliberate act of challenging the artistic establishment's reverence for craft and beauty. It argued that the artist's intellectual choice and conceptual gesture were paramount, not manual skill. |

| Collage & Photomontage | Juxtaposing disparate elements, often sourced from newspapers, magazines, and discarded materials, to create new, often jarring, meanings – or deliberately, no coherent meaning at all. This technique mirrored the fragmented reality of their post-war era and offered sharp social commentary by deconstructing media narratives. | Hannah Höch’s intricate photomontages, such as Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, are masterpieces of satirical deconstruction. Höch was a pivotal, yet often overlooked, female Dadaist, whose work frequently critiqued gender roles and societal structures. |

| Performance Art | Raucous, nonsensical performances, poetry readings (including Hugo Ball’s sound poems like Karawane), and theatrical acts that challenged traditional artistic expression and often provoked audiences. Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich was the epicentre for these experimental, often chaotic, public displays, setting a precedent for much of 20th-century performance art and aiming to shock audiences out of their complacency. |

It was a brief but explosive movement, paving the way for many others. Surrealism emerged directly from Dada's ashes, adopting its embrace of the unconscious and irrational but with a more focused exploration of dreams and psychoanalysis. Dada also influenced movements like Futurism, sharing a rejection of the past and an embrace of modernity and shock, though Dada critiqued the very technological progress Futurism often celebrated. Similarly, it resonated with Constructivism's anti-bourgeois stance and experimentation, yet lacked their utopian or technologically optimistic visions. If you're interested in the broader context of art history, their story is a crucial chapter in the History of Modern Art.

![]()

Dada's Whispers and Shouts in Contemporary Art: A Persistent Provocation

But Dada wasn't just a historical footnote; its radical ideas didn't disappear. Instead, they permeated the art world, shaping the very way we create and consume art today. Now, you might be thinking, "Okay, cool history lesson, but how does a movement from a hundred years ago affect the vibrant, often abstract, art I see today, or even the pieces I create and offer for sale?" Ah, my friend, that's where the magic is. Dada didn't just fade away; it seeped into the very foundations of how we think about art, shaping the aesthetic landscape and philosophical underpinnings of much that came after. Its echoes are not always overt, but they are undeniably present, like a ghost in the machine of modern creativity, a persistent provocation that continues to challenge our expectations. And perhaps, more importantly, its defiant spirit feels incredibly timely in our own age of information overload and shifting realities, where questioning everything feels like a daily necessity. These echoes manifest in various compelling ways:

1. The Power of the Ordinary & Art as Idea: Conceptualism's Roots

Dada's radical declaration that anything can be art if the artist declares it so, fundamentally shifted our understanding of artistic value. This liberation from traditional materials and subjects paved the way for artists to use found objects, unconventional media, and even digital scraps. Simultaneously, Dadaists prioritized the idea behind the work over the aesthetic object itself – an anti-art stance that questioned the very necessity of a finished 'masterpiece'. This was a profound philosophical shift, moving art from a focus on craft and the "retinal" (what the eye sees) to a focus on the conceptual. This fusion was a direct precursor to conceptual art, where the concept is paramount. For me, this resonates deeply; it's less about the perfect brushstroke and more about the underlying message or emotion I'm trying to convey. Think of artists like Tom Sachs, who meticulously recreates consumer products with mundane materials, challenging our perceptions of value and beauty, or the raw, assemblage works of Robert Rauschenberg, which elevate the everyday. Contemporary artists often work in series that explore ideas, systems, or philosophical questions, rather than just creating beautiful images, a direct inheritance from Dada's intellectual rebellion.

2. Performance, Happenings, and the Experiential

The chaotic, often spontaneous performances at Cabaret Voltaire laid the groundwork for performance art as we know it, directly inspiring the happenings of the 1950s and 60s. Today, artists still use their bodies, actions, and interactive experiences to convey messages, often challenging the passive role of the viewer. It's about immersing you, the audience, in something that makes you feel or think, not just observe – an urgent call to engagement that echoes Dada's disruptive spirit. I sometimes wonder what Hugo Ball would make of modern immersive digital installations; I suspect he’d be both delighted and utterly confused, which I imagine is exactly what he’d want.

3. Challenging the System: Institutional Critique's Forebears

One of Dada's most enduring legacies is its fierce anti-establishment stance. They famously questioned museums, galleries, and the very gatekeepers of art, often through provocative exhibitions designed to mock traditional art salons. This spirit lives on vibrantly in artists who critique consumerism, politics, and the art market itself, using art as a weapon for social commentary and institutional critique. Think of provocative street art or installations that deliberately disrupt public spaces. Artists like Banksy or Ai Weiwei clearly carry this torch, refusing to let art exist in a vacuum, demanding it engage with the world's pressing issues. They’re shouting, not whispering, and it's a message Dada would applaud.

4. Collage and the Fragmented World: A Timeless Reflection

The Dadaist embrace of collage—cutting, pasting, and reassembling images and text, often sourced from newspapers and magazines—mirrors not only their fragmented post-war world but also our own modern, fragmented information age. This technique, pioneered by artists like Hannah Höch, allowed for a direct commentary on the media landscape, and crucially, foreshadowed how digital media would present information in a dislocated, often jarring way. Artists continue to use collage, both physical and digital, to explore identity, memory, and the overwhelming barrage of images we encounter daily. It’s a way to make sense of, or deliberately destabilize, our visual world, much like the Dadaists did when confronting the chaos of their time. For me, the process of layering and juxtaposing forms in my abstract work often feels like a spontaneous, intuitive collage, where disparate elements find an unexpected harmony.

5. The Abstract Path: Freedom from Representation's Chains

While Dadaism itself was not an abstract art movement, its radical rejection of traditional forms, narratives, and the very need for art to depict reality certainly opened doors for movements like Cubism and Abstract Expressionism to flourish. By championing irrationality, non-meaning, and the freedom from conventional aesthetics, the Dadaists inadvertently gave artists profound permission: the freedom to explore pure form, color, and emotion, liberating art from its representational shackles. It was a foundational act of anarchy that allowed subsequent abstract movements to build entirely new languages. The ability to make expressive lines and gestures without literal meaning owes a profound nod to this rebellion, and the ongoing exploration of non-representational works, which I often delve into when decoding abstract art, owes much to this early artistic anarchy.

6. Dada in the Digital Age: Art and Misinformation

Perhaps the most poignant connection between Dada and our current era lies in its response to a world reeling from "alternative facts." Born from a profound distrust of the logic that led to war, Dadaists embraced nonsense and paradox as a means of critique. They understood that by using absurdity, they could expose the absurdity of the "truths" presented by the establishment. Today, in an age saturated with misinformation and curated digital realities, the Dadaist spirit of questioning, deconstruction, and even playful absurdity offers a powerful lens through which to view and challenge the narratives presented to us. It’s a form of "truth-telling" through disruption. When I see an AI-generated image that blurs the line between real and fake, or a meme that perfectly distorts a political statement, I can't help but feel a mischievous Dadaist spirit at play, reminding us to question the authenticity and intent of every image and message we consume. It’s like they designed the internet before the internet even existed, and this constant interrogation of perception feels deeply relevant to how I, as an artist, approach expressing genuine emotion in a world of manufactured images.

Dada's Playfulness in My Abstract Studio: Embracing the Unforeseen

This pervasive influence isn't just something I observe in the wider art world; it's a spirit that actively informs my own creative process. When I'm in my studio, often lost in thought, the spirit of Dada sometimes creeps into my practice. It's not about making a direct Dadaist piece, but rather about embracing the freedom to experiment, to welcome accident, to challenge my own preconceptions of what a painting should be. You know that feeling when you're supposed to follow a recipe, but your intuition (or perhaps a tiny voice of defiance) whispers, "What if...?" That's the Dadaist spirit at play, and it’s a thrill. It's the moment when a drip isn't a mistake, but an unexpected gift, or when a bold, seemingly random mark adds an emotional layer I hadn't planned. This embrace of the unforeseen, of spontaneous action over rigid planning, feels like a subtle echo of that early 20th-century anarchy, an invitation to explore the art of intuitive painting. There's a liberating "aha!" moment when I realize that embracing chaos can lead to a deeper, more authentic expression than rigid adherence to a plan.

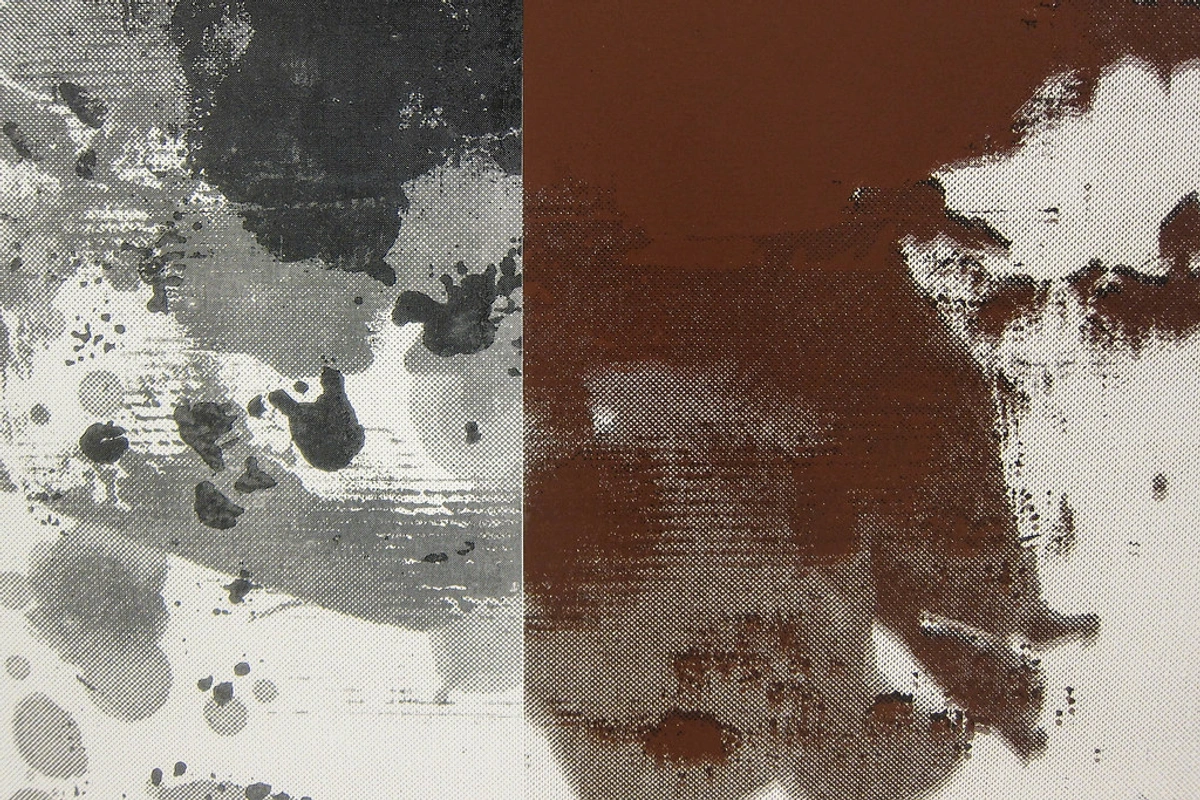

I often see echoes of this playful, deconstructive spirit in artists like Christopher Wool. While his work doesn't always feature literal "word paintings," his abstract compositions often incorporate stenciled elements, repetition, and a deliberate obscuring of legibility, brilliantly deconstructing not just language but also the very act of painting. His approach challenges traditional aesthetic notions and celebrates a raw, urban energy, much like Dadaists played with linguistic nonsense and societal critique. His work, and indeed the entire approach of the power of imperfection: embracing accidents and evolution in my abstract art, feels like a direct descendant of that rebellious interrogation of what art (and meaning) can be.

Similarly, Gerhard Richter, with his systematic yet abstract works, demonstrates how contemporary artists continue to question and deconstruct. Richter's famous 'squeegee' paintings, for example, intentionally remove the artist's 'hand' and traditional skill, introducing an element of chance and mechanical process that pushes against conventional notions of artistic creation, much like the Dadaists did in their time by rejecting the cult of the artist's genius. He even manages to introduce a subtle wink by playing with the viewer's expectations of what an abstract painting 'should' be, almost daring us to find logic in the beautiful chaos.

Another artist whose spirit feels delightfully connected to Dada's raw, deconstructive energy is Jean-Michel Basquiat. His art, often described as Neo-Expressionist, shares Dada's rebellious disdain for academic polish and its embrace of fragmented imagery, text, and everyday detritus. Basquiat's powerful works often combine street art aesthetics with profound social commentary, echoing Dada's use of art as a weapon against societal norms and its willingness to challenge notions of traditional beauty with a raw, almost childlike energy. He took the chaos of the streets and, like the Dadaists with their found objects, elevated it to high art, forcing us to confront difficult truths in unexpected ways.

Key Takeaways: Dada's Lasting Imprint

Dadaism, despite its brief lifespan as a cohesive movement, left an indelible mark on the trajectory of modern and contemporary art. Here are its core, enduring contributions:

- Radical Redefinition of Art: Challenged the very definition of art, skill, and aesthetic beauty, paving the way for anything to be considered art and fundamentally shifting focus to the artist's conceptual intent rather than manual craft.

- Emphasis on Concept: Prioritized the idea behind the artwork over the finished aesthetic object, a direct and essential precursor to conceptual art.

- Freedom from Representation: Liberated art from the necessity of depicting objective reality, opening doors for abstract movements to explore pure form, color, and emotion without narrative constraints.

- Fierce Critique of Institutions: Fostered a critical stance towards art institutions, consumerism, and societal norms, inspiring generations of artists to use art as a potent tool for social and political commentary.

- Embrace of Chance & Absurdity: Introduced randomness, humor, and non-logic as valid artistic tools for expression and provocation, deliberately defying rational control and questioning established meaning.

- Pioneer of Performance: Established early forms of performance art and happenings, influencing live art forms and promoting active audience engagement and disruption.

- Influence on Media & Technology: Utilized and commented on emerging mass media (like newspapers and photography), presciently foreshadowing our modern engagement with fragmented information and digital realities.

Unraveling Dada's Riddles: Common Questions

Of course, all this talk of anarchy and absurdity often sparks a few questions. Here are some common ones I hear when talking about this wonderfully eccentric movement:

- Was Dadaism serious? Oh, absolutely! While it embraced nonsense and absurdity, its underlying message was a deeply serious critique of war, nationalism, and the failures of society. It just chose unconventional, often humorous, methods to deliver that critique, understanding that absurdity could be a potent form of truth-telling against a world that had gone mad. This duality is one of its most fascinating, and frankly, most relatable aspects.

- What role did women play in Dada? While often overshadowed, women artists were crucial to Dada. Figures like Hannah Höch (renowned for her powerful photomontages that critically deconstructed the media and societal roles), Sophie Taeuber-Arp (known for her abstract textiles, marionettes, and performances, blurring the lines between fine art and craft), and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (a radical performance artist and poet, pushing boundaries of gender and decency with fierce originality) were central to the movement, challenging gender norms and artistic conventions with unwavering artistic courage.

- What are some key Dadaist artworks or manifestos I should know about? Beyond Duchamp’s

Fountain, consider Hannah Höch’s intricate collages, especiallyCut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany. For literary context, Tristan Tzara’sDada Manifestosare essential reads for their chaotic energy, as are Hugo Ball’s mesmerizing sound poems, such asKarawane, performed at Cabaret Voltaire. These works exemplify the movement's diverse, provocative, and often chaotic output. - How did Dadaism end? Dada didn't really "end" as much as it evolved. By the early 1920s, the initial fervor had dissipated, and many of its key figures transitioned into Surrealism, which built upon Dada's embrace of the unconscious and irrational but with a more focused exploration of dreams and psychoanalysis. Its influence, however, never truly ceased; it simply morphed, becoming a foundational tremor in modern art history that continues to ripple outwards.

- Is contemporary art still Dadaist? Not in its pure, historical form, but the spirit of Dadaism—its questioning of authority, its embrace of experimentation, its blurring of art and life, and its use of humor and irony—is undeniably alive and well in much of today's contemporary art. You can see it in protest art that uses shock tactics, performance pieces that challenge audience expectations, and digital art that playfully subvert meaning. It's a foundational tremor that continues to ripple through the art world, informing everything from conceptual installations to activist street art. We're still asking those questions, just with different tools.

- Can anti-establishment art like Dada become commercialized? Absolutely, and it's a fascinating paradox. While Dada explicitly rejected the commodification of art, its radical ideas and iconic works have, ironically, become highly valuable within the very art market it sought to dismantle. This ongoing tension between artistic intent and market forces remains a relevant discussion in the art world today.

- Can I incorporate Dadaist principles into my own creative practice? You absolutely can, and I wholeheartedly encourage it! Try embracing chance, using found objects, or deliberately breaking your own rules. It's a fantastic way to unlock new creative pathways and challenge your artistic comfort zone. Perhaps it’s a good excuse to see my own creative timeline evolve with such experimentations!

The Art of the Question Mark: Why Dada Still Matters (and Why I Love It)

Dadaism reminds us that art isn't just about beauty or skill; it's about asking questions, challenging assumptions, and perhaps, most importantly, about freedom. It’s about looking at a bicycle wheel and calling it art, or presenting a readymade bottle rack as a profound statement. It's the ultimate permission slip for creativity, a reminder that the most profound insights can sometimes come from the most absurd places. This ethos feels more vital than ever in a world constantly seeking order and meaning, especially when navigating the complexities of our digital age, where truth and fiction often dance a bewildering jig.

For me, that's a liberating thought. As an artist creating abstract works, it means embracing the unexpected drip, the unforeseen brushstroke, and the freedom to challenge my own artistic conventions. It means that the playful defiance I explore in my studio, often leading to vibrant abstract art for sale, is part of a century-long conversation. And as someone simply trying to navigate a world that often takes itself far too seriously, it’s a constant reminder to find joy, and even profound meaning, in the irrational.

So next time you encounter something that makes you scratch your head in delightful confusion, take a moment to thank the Dadaists. They kicked down the doors of convention, and the echoes of their joyful anarchy still make our artistic world a more interesting, unpredictable, and yes, delightfully perplexing place. Perhaps, even, to inspire a similar experience in my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, where art challenges and delights in equal measure, carrying that Dadaist torch into a new century.

For further reading and viewing, consider Dada: Art and Anti-Art by Hans Richter, or watch a documentary like Dadaism (2016) directed by Julian Ball, for a deeper dive into its fascinating history and enduring impact.