Gerhard Richter: Art's Paradoxical Master & Reality's Reimaginer

Dive into Gerhard Richter's world of paradox: from blurring photo paintings and abstract squeegee art to conceptual glass works. Discover how his lifelong inquiry into truth, perception, and the nature of art continues to redefine reality.

Gerhard Richter: The Artist Who Mastered Paradox & Redefined Reality

Have you ever found yourself utterly baffled by a work of art, only to have that initial bewilderment slowly, profoundly reshape your entire understanding of things? For me, that exhilarating, often disorienting, journey truly began with Gerhard Richter. I remember seeing an image of his Abstract Painting (724) for the first time, probably online, and thinking, "Is this just a bunch of scraped paint?" But that dismissive thought quickly dissolved into a profound fascination. He's an artist of profound paradoxes, where the objective often dissolves into the subjective, the clear becomes ambiguous, and planned gestures birth accidental truths. This constant interplay of opposites—especially the radical tension between disquieting photo-based realism (his paintings derived from photographs, not photographs themselves) and exhilarating pure abstraction—is a thread that runs through his entire, incredibly diverse body of work, even extending to his early conceptual pieces like Table (1962) or Ema (Nude on a Staircase) (1966), which systematically deconstructed visual truth long before his iconic blurred images, challenging the very notion of a single, fixed reality.

His unparalleled career has cemented his place as arguably the most important living German artist and one of the most significant figures in contemporary art globally. Why? Because he fearlessly synthesizes disparate art movements into a cohesive, lifelong philosophical inquiry, profoundly influencing generations of artists. The profound value placed on his challenging oeuvre is underscored by his consistent ranking among the world's most expensive living artists – a testament to his enduring critical acclaim, global appeal, and the scarcity of his groundbreaking pieces in a highly competitive market. It's a curious paradox, isn't it? How can art that deliberately blurs reality and questions truth fetch such astronomical prices? For me, it speaks to a universal human need to grapple with uncertainty, to find meaning in the ambiguous, and to recognize profound honesty even when it’s uncomfortable.

My first encounter with Richter’s work in person, a monumental abstract piece at the Tate Modern, was overwhelming. It wasn't just paint; it was a feeling, a whole universe of movement, light, and shadow that felt like watching a storm unfold or a distant galaxy coalescing. This immersive experience cemented my need to delve deeper into his art, not just intellectually, but personally.

Richter's Unfolding Journey: A Career Overview

To truly grasp the breadth and depth of Richter's vast and often surprising artistic journey, it's helpful to see his career as a series of interconnected explorations, each feeding into a larger, lifelong inquiry into perception and representation. Let's trace his major artistic periods chronologically:

- Early Conceptual Works & Capitalist Realism: His initial explorations questioning visual truth and critiquing consumer culture.

- Photo Paintings: The iconic period blurring reality, memory, and the perceived objectivity of photography.

- Abstract Paintings: Plunging into subjective experience through a deliberate dance between control and chance with his signature squeegee technique.

- Conceptual Turns (Color Charts & Glass Works): Pushing the boundaries of what painting can be through systematic explorations of color and light, even extending to sculptural forms.

- Later Innovations: Embracing new technologies like digital manipulation in his Strips series and revisiting profound historical reflections with works like Birkenau.

Who is Gerhard Richter, Really? A Life Beyond the Canvas

This relentless questioning of what we see and know didn't just appear out of thin air; it's deeply rooted in Richter's formative years. Born in Dresden, Germany, in 1932, Gerhard Richter's early life was profoundly marked by the tumultuous landscape of post-war Germany. He lived in East Germany, where he initially studied at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. Before this, he even trained as a sign and advertising painter, an experience that, though seemingly mundane, would later sharpen his keen eye for how images persuade, mislead, and shape public perception, almost as if he was unwittingly being trained to dissect the very visual propaganda he would later subvert.

Immersed in the rigid doctrines of Socialist Realism, which mandated a specific, idealized depiction of reality for propaganda, this early exposure to state-controlled art inevitably fueled his lifelong skepticism towards grand narratives, ideologies, and the very 'truth' presented by images. It laid the philosophical groundwork for his relentless questioning of visual representation, especially how images are used to construct and control reality.

Then, in 1961, just months before the Berlin Wall went up, he made the audacious decision to flee to West Germany. Imagine that leap of faith, leaving everything behind for an unknown future – I often wonder if I could muster that courage, or if the sheer force of circumstances would simply carry me. It’s a powerful testament to the yearning for freedom, a theme that subtly yet powerfully echoes throughout his entire career – freedom from artistic dogma, freedom to explore every facet of visual expression, and a deep-seated distrust of absolute truths, allowing him to defy categorization. This constant seeking, this deliberate refusal to be confined, showcases artistic evolution born from personal history; a journey I find endlessly fascinating, reminding me how our pasts undeniably inform our present creations, even when it feels like we’re trying to escape them.

Upon arriving in the West, he studied at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, where he would later become a professor (1971-1994), significantly influencing generations of German artists. Here, alongside fellow artists like Sigmar Polke and Konrad Lueg, he pioneered what they provocatively termed Capitalist Realism. This wasn't some grand political manifesto, but a sharp, ironic artistic movement that emerged in direct opposition to the East's Socialist Realism. The Wirtschaftswunder, or economic miracle, was transforming West Germany, filling it with consumer goods and American cultural influences, and Richter was there to hold a mirror up to it.

Capitalist Realism slyly mimicked and critiqued the burgeoning consumer culture of West Germany, the pervasive Americanization, and the increasing media saturation and superficiality of Western society. Richter basically took the glossy ads of the West and, with a sly wink, held a mirror up to them. He deliberately blurred the lines between high art and advertising, confronting the commercialization of art by turning its very aesthetics back on itself, perhaps even exposing their hollow promise. His works from this period, like Party (1963) or Aunt Marianne (1965), often mimicked the flat, detached aesthetic of candid snapshots or amateur photography, deliberately blurring the lines between high art and advertising. By presenting mundane, bourgeois scenes with an almost clinical detachment, he slyly exposed the inherent superficiality and commercialization hidden beneath the polished veneer of West German society.

This period also saw him engage with broader movements like Fluxus, an avant-garde art movement of the 1960s known for its experimental art events and focus on process over product, and Pop Art, which challenged traditions by featuring mass-media imagery and commercial products. Unlike Pop artists who often celebrated mass culture, Richter's engagement was more critical; he used their aesthetics to question the media-saturated reality they reflected, forcing viewers to confront their own perceptions and the constructed nature of reality. He wasn't just reflecting pop culture; he was dissecting it with his characteristic intellectual rigor.

This early period of relentless questioning, alongside his profound need to systematically categorize and analyze visual information, is best exemplified by his monumental, ongoing Atlas project. This isn't just a collection; it's a vast, ever-expanding visual encyclopedia of his mind, a lifelong archive of tens of thousands of images – photographs, clippings, sketches, studies – meticulously arranged on hundreds of panels. More than a source, it's a conceptual artwork in its own right, a testament to his methodical yet fluid approach, a visual diary of his relentless inquiry into how images shape our understanding, and how his seemingly disparate artistic periods are unified into one grand, evolving narrative. It’s almost as if he was trying to collect every fragment of visual reality, knowing each piece held a hidden question about truth and perception.

To truly grasp the context of Capitalist Realism, it's helpful to contrast it with its ideological counterpart, Socialist Realism, as shown below:

Feature | Socialist Realism | Capitalist Realism |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Propaganda, glorify state/party | Critique consumerism, media, art market |

| Subject Matter | Idealized workers, collective achievements | Everyday objects, media imagery, portraits |

| Style | Heroic, clear, didactic | Ironic, often blurred, mimicking advertising |

| Approach | State-mandated dogma | Playful subversion, questioning reality |

The Photo Paintings: Capturing Elusive Truths (or, Why is it Blurry?)

Have you ever found yourself wondering why an artist would deliberately blur a perfectly good image? It’s a question that often arises with Richter’s Photo Paintings, perhaps his most recognizable and, for some, most perplexing period. His early preoccupation with challenging the 'truth' of images and media portrayal, honed during the Capitalist Realism period, laid the groundwork for this groundbreaking exploration. "I don't think I'm doing anything other than pointing to an existing reality," Richter once said, "even if it's only the reality of a photograph." This simple statement encapsulates the complexity of his Photo Paintings.

Blurring Perception and Memory

Richter would project photographs – meticulously sourced from diverse origins like personal family albums, anonymous newspaper clippings, found images from advertisements, police mugshots, historical documents, or amateur snapshots – onto canvas. This varied sourcing itself is profoundly significant, highlighting how images, regardless of their origin or perceived authority, collectively shape our perception and memory, further blurring the lines between private recollection and public narrative, between what we know and what we think we know.

He would then paint them, often blurring or smudging the image with a dry brush or a squeegee. My initial reaction was usually, "Did he just forget his glasses?" or "Why would you do that to a perfectly good photograph?" (I admit, my art appreciation sometimes starts with a dash of skepticism, swiftly followed by profound realization).

When these works first emerged, they were seen as a radical challenge to both traditional painting and the objective authority of photography, sparking intense debate about the very nature of representation. Early critics grappled with his deliberate obscuring of photographic 'truth,' seeing it as either a profound commentary on perception or a radical act of artistic nihilism. Many found the blurring unsettling, accusing him of defacing images or denying the viewer clarity, yet it was precisely this discomfort that forced a deeper inquiry into how we construct reality. What does it mean for an image to be true, anyway? And what about our own memories – aren't they just as fuzzy and fleeting? It reminds me of those fleeting moments when I try to recall a vivid dream, only to find the edges blurring, the details slipping away. Or perhaps how memories of childhood, once sharp, soften over time, becoming more about the feeling than the precise visual. For me, this speaks to the inherent subjectivity of vision and the fragility of what we consider concrete reality.

This blurring isn't about hiding details; it's a deliberate artistic act aimed at questioning the very nature of perception, memory, and the supposed 'truth' of photography. While a photograph freezes a moment and claims objectivity, human memory is fluid, shifting, imperfect, and inherently subjective. Our memories aren't sharp, pristine snapshots; they're often faded echoes, hazy recollections, or a jumble of emotions and impressions, much like trying to recall a dream immediately after waking. Richter's blurred images mirror this human experience, creating a haunting echo of how we actually remember events and faces. He meticulously applied oil paint with both precise brushes for initial rendering and then broader tools like squeegees for the signature blurring effect.

Technique and Distinctive Works

He also explored Overpainted Photographs, a distinct yet related technique. To clarify: Photo Paintings begin with a projected photograph, which Richter then painstakingly renders from scratch onto canvas, often blurring it to question the image's inherent 'truth.' Overpainted Photographs, by contrast, involve painting directly over existing photographic prints, adding subjective, painterly marks onto a mechanically reproduced image. This radical approach further dissolved the boundaries between objective record and subjective interpretation. It's as if he could never quite settle on a single way to see the world, always needing to layer and reconsider, which, frankly, mirrors how my own thoughts often pile up when I'm wrestling with a complex idea.

Richter extended his photo-painting technique to an astonishing array of subjects, each imbued with his signature questioning gaze. Think of his iconic Betty (1988), a tender yet enigmatic portrait of his daughter looking away – it’s a photograph made painterly, yet it still feels intensely personal, a memory glimpsed rather than observed. He also painted numerous portraits of famous figures, such as John Cage or Queen Elizabeth II, further highlighting his detached yet penetrating approach to public imagery and celebrity. Then there's the solemn October 18, 1977 series, a poignant, unsettling reflection on the Baader-Meinhof Group, a German terrorist organization active in the 1970s. The paintings feel less like sharp journalistic records and more like faded, haunting memories of a turbulent era. This series sparked significant public discussion and ethical debates in Germany due to its sensitive subject matter and Richter's deliberately detached, yet deeply resonant, approach to recent history.

His mesmerizing Landscapes and Seascapes, like Seascape (Cloudy) (1969), transform familiar scenes into ethereal, dreamlike vistas. Even when depicting nature, his signature blur makes them feel like a distant memory or a sublime, overwhelming force, inviting you to truly feel the atmosphere, rather than just observe the scene. It’s like he’s capturing the essence of a place, rather than its precise contours, a concept that deeply resonates with my own attempts to convey mood over precise detail in my work.

Beyond these, his numerous portraits – including haunting self-portraits and those of other family members – delve into the psychological depth of fleeting moments, showing how time and perception subtly obscure even the most intimate faces. And then there's Candle (1982), a surprisingly traditional subject rendered with that signature blur. It's a poignant reminder that even the most mundane objects hold layers of meaning, obscured by time or perception. I often think about this when I'm trying to capture a fleeting emotion in my own art – sometimes, the less distinct, the more resonant, a truth I found surprisingly liberating.

The Abstracts: A Universe of Feeling – My Personal Journey

What is it about abstract art that pulls you in, making you feel something profound without a clear narrative? If his photo paintings explored the illusion of objective reality, then his abstract paintings plunge headfirst into the reality of subjective experience and the controlled chaos of artistic creation. My personal connection to Richter deepened significantly when I truly engaged with his Abstract Paintings. Many are monumental in scale, enveloping the viewer in a visual universe, transforming passive observation into an immersive experience. The sheer size of these works emphasizes the overwhelming physicality of the paint, the vastness of the chromatic landscapes, and the profound spatial depth created by his distinctive squeegee technique.

The Squeegee: A Dance of Control and Chance

Unlike many Abstract Expressionists (think Rothko, whose profound emotional resonance I also admire) who prioritized raw, spontaneous gesture and emotional outpouring, Richter's approach to abstraction is a deliberate dance between control and chance, rooted in a more intellectual and detached methodology. He brings a systematic rigor to seemingly chaotic results, setting him apart within the broader history of art guide of abstract art. It's not just about what he feels; it's about what the paint does when he forces it into new configurations. This blend of method and madness is what truly captivates me. While Rothko's emotion is often a crashing wave of pure, immediate feeling, Richter's is a meticulously constructed, yet deeply moving, architectural marvel of sound, emerging from the tension of his concepts and process, built layer by painstaking layer. Appreciating both is like listening to two different, equally profound symphonies.

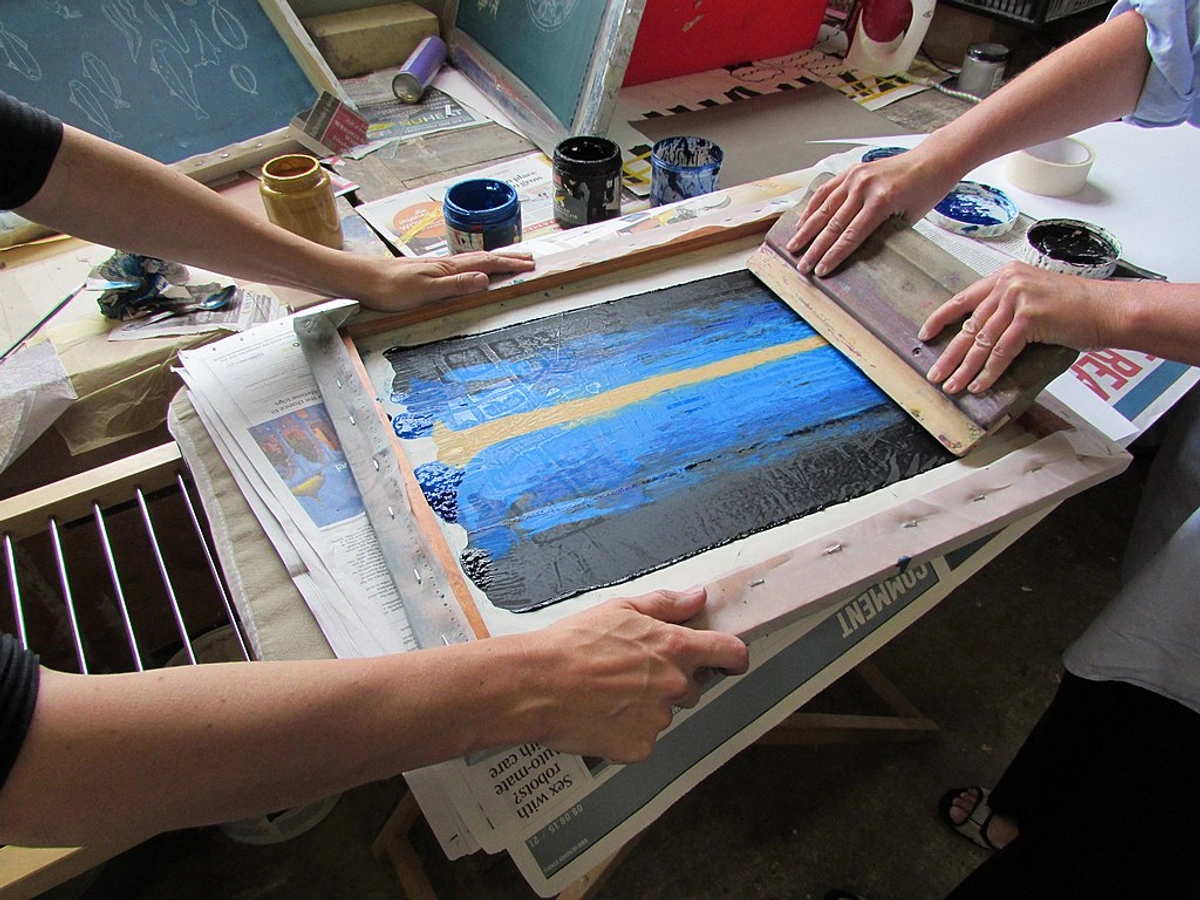

He applies multiple layers of oil paint, often in vibrant colours, then drags a large squeegee across the surface, scraping, revealing, and transforming the underlying colours. The physicality of this process is immense – layers of thick, buttery oil paint are built up over days or weeks, each allowed to dry to a certain tackiness before the next layer is applied, then violently, yet purposefully, scraped away. I imagine the sound of the squeegee, a low, resonant drag, revealing the complex history beneath.

This isn't a quick swipe; it's a carefully orchestrated preparation, sometimes using photography as initial source material and then methodically building layers before the 'chance' operation of the squeegee reveals its profound intellectual rigor. It’s a process of systematic destruction and creation, where the seemingly spontaneous result is, in fact, the culmination of meticulous layering, repeated interventions, and countless individual drags and pushes – a testament to deep intention within the realm of accident.

This deliberate dance between intention and relinquishing control is, for me, a profound statement about allowing the material to speak, mirroring life's own beautiful unpredictability. You might look at Abstract Painting (724) or Abstract Painting (599) and think, "That looks fun! Just push paint around." And while it might indeed be an exhilarating process, the true genius lies in the inherent tension, the rich, tactile textures, and the unexpected harmonies that emerge from this controlled chaos. It’s like watching a geological formation unfold in real-time, or perhaps a microcosm of the universe forming on canvas. For me, it evokes a sense of both the cosmic and the intimate, the feeling of witnessing something vast yet deeply personal.

My Resonance with Abstraction

As an artist who also explores abstraction, Richter's abstracts were a revelation. They taught me that abstraction isn't just about random splatters; it's about distillation, about expressing complex emotions or ideas through pure colour and form. It's like listening to a symphony without lyrics – the meaning is in the feeling. His willingness to embrace both absolute control and radical chance in his process resonated deeply with my own evolving approach to how to abstract art. I remember struggling to find a balance between structure and spontaneity in my early abstract pieces, always feeling too constrained or too chaotic. Seeing Richter’s meticulous layering followed by the 'uncontrolled' squeegee drag was a lightbulb moment, showing me that relinquishing some control can paradoxically lead to richer, more authentic expressions. It even inspired me to try using larger squeegees in my own work, experimenting with layering and scraping to reveal unexpected textures. Honestly, sometimes my own studio feels like a beautifully controlled disaster, and Richter makes me feel right at home with that paradox!

His abstracts feel like glimpses into a chaotic, yet ultimately beautiful, internal landscape. They remind me that sometimes, to truly see, you have to let go of needing to understand, to simply allow the layers of paint and meaning to wash over you. Each layer scraped back, each unexpected colour emerging, offers a fresh perspective, a new narrative to decipher or simply feel. It’s a profound testament to the notion that art can exist without explicit narrative, instead inviting a purely visceral, emotional response.

The Conceptual Turn: Color Charts and Glass Works

So, if Richter’s abstracts pull you into a world of pure feeling and illusion, what comes next? For an artist who painted 'truth' through blurring, then plunged into pure abstraction, the answer was, surprisingly, art that looks like... paint swatches? Or maybe just giant panes of glass? My first thought was, "Is this art or a paint shop catalogue?" But trust me, his Color Charts and Glass works are just as profound, if not more so, in their conceptual depth, pushing the boundaries of what painting can be.

His Color Charts, for instance, seem almost clinical – grids of meticulously painted squares. When I first saw his Color Charts, my inner critic snickered, "Is this a paint shop catalogue or art?" It felt so sterile, so unlike the emotional punch of his abstracts. But then it clicked – the genius wasn't in the emotion, but in the deliberate absence of it, the conceptual power of challenging subjectivity itself. Inspired by industrial color cards and paint sample books, these works, deeply aligned with the Minimalism and Conceptual Art movements of the 1960s – which championed simplicity, geometric forms, and ideas over emotional expression – are not just about color theory. They're a playful commentary on the commodification of art, a nod to industrial processes, and a deliberate rejection of subjective expression. Richter himself often employed a systematic, random selection process for the colors, further underscoring the objective, depersonalized nature he was exploring. It makes you wonder how far art can push the boundaries of what is considered subjective expression, and if even the act of selection implies a kind of concealed emotion. This kind of conceptual depth is why he's so important in the history of art guide.

His Glass works, ranging from massive reflective panels and monumental mirror installations to the breathtaking 11,263-square-foot stained glass window at Cologne Cathedral (2007) and pieces like 4 Panes of Glass (1967), further push the boundaries of perception. The Cologne Cathedral window, a mosaic of 11,500 hand-blown glass squares in 72 colors, stands as a monumental contemporary art installation within a sacred architectural context, transforming divine light into a dynamic, ever-changing abstract painting that truly demands physical presence. The genius of these works lies in their dynamic interaction with light, space, and the observer. As you move, the reflections shift, incorporating your own image and the surrounding architecture into the piece, creating an ever-changing, immersive experience. It's almost like walking into a painting itself, where the space around you becomes part of the composition, distorting and reflecting reality in a fascinating dance. I've felt this immersion firsthand in various museums – it’s a whole different experience from seeing prints online, where you're just looking at a flat screen rather than becoming part of the piece. It’s the kind of work that truly demands your physical presence, subtly altering your perception of the world around you, even disorienting it just enough to make you question what's real and what's reflection – which, for me, is the true mark of profound art.

This period also saw Richter dabble in minor sculptural works like Two Sculptures for a Room by Palermo (1971), further underscoring his boundary-pushing across mediums – a curious little side-quest in his prolific career that always makes me chuckle, thinking of an artist so focused on surface suddenly thinking in volume.

Later Innovations & Profound Legacy

What else did this relentless questioner explore? Even as he transitioned into semi-retirement from active painting, Richter's later career continued to push boundaries, embracing new technologies and revisiting fraught historical themes. This continuous evolution cemented his place as a truly enduring presence in the art world.

Later Works & Digital Explorations

He extensively explored printmaking, translating the themes and techniques of his paintings into editions, further demonstrating his relentless pursuit of new modes of expression and his systematic approach to how an image can be disseminated and experienced. Building on this exploration of imagery's dissemination, Richter also pursued his own independent photographic practice. This wasn't merely collecting images for source material; he used the camera as a medium in its own right, exploring its inherent qualities and further blurring the lines between objective observation and subjective interpretation, highlighting his constant questioning of visual representation. His later digital abstractions, known as the Strips series, further exemplify this continued engagement with new technologies and the manipulation of images.

These Strips are often derived from photographs of his own abstract paintings, digitally sliced into fine vertical strips and then reassembled. This intricate process creates a meta-commentary – a reflection on the very act of artistic creation and its digital reproducibility – on the impact of digital manipulation and the digital age’s influence on perception, turning his painterly gestures into something new and algorithmically generated. And in one of his most powerful and later series, Birkenau (2014), Richter returns to the fraught relationship between painting, photography, and historical memory, a poignant culmination of his lifelong inquiries. Based on blurred photographs taken by a prisoner in Auschwitz, these monumental abstract paintings powerfully synthesize his career-long exploration of abstraction, representation, and the unspeakable trauma of history. The series, while profoundly moving, also sparked discussions around the ethical limits of representation, questioning whether such immense human suffering should be abstracted or if abstraction offers a necessary pathway to confront the unspeakable without exploiting it. It’s a series that forces me to grapple with uncomfortable questions, reminding me that art can face the darkest truths without flinching, even when the answers remain elusive.

Enduring Legacy & Influence

Even in his later years, Richter has remained a formidable and influential presence. I often wonder about his studio, picturing the meticulous setup, the large squeegees leaning against walls, and the dedicated assistants, all underscoring his precise yet expansive vision and revealing a hidden structure behind his seemingly free artistic process. Furthermore, his careful approach to exhibition design and curation of his own work reveals his commitment to controlling the viewer's experience, often arranging his pieces to create specific dialogues between seemingly disparate series, ensuring a comprehensive narrative unfolds for the observer.

His monumental influence is also evident in his extensive exhibition history, with major retrospectives at prestigious institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York (notably his significant 2002 retrospective, "Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting"), the Tate Modern in London (whose major 2011 exhibition "Panorama" was equally impactful), and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, solidifying his global critical acclaim. While his market value often grabs headlines, the depth of his critical reception lies in how he consistently pushed the boundaries of painting itself, challenging its historical purpose and forging new paths for its future. Richter's willingness to constantly reinvent himself, to defy categorization, and to challenge our preconceptions about what art is has had an immense impact on contemporary art. He has influenced a wide range of artists, particularly those exploring the tension between painting and photography, the role of chance and control in abstraction, and the complex relationship between art and memory, such as those who challenge traditional media boundaries or explore the psychological impact of images.

He's often compared to other abstract masters like Rothko for his profound emotional resonance; however, while Rothko's emotion is often raw and immediate, Richter's is frequently more intellectualized, emerging from the tension of his concepts and process. For me, appreciating both is like listening to two different, equally profound symphonies – one a crashing wave of pure feeling, the other a meticulously constructed, yet deeply moving, architectural marvel of sound. His radical approach opened doors for countless artists, demonstrating that painting could be both a deeply personal expression and a rigorous conceptual inquiry. He’s one of those rare artists who can make you think deeply while also making you feel deeply, often simultaneously – a paradox he seems to relish.

As Richter himself once famously stated, "Art is the highest form of hope." For him, art isn't about definitive answers, but about the ongoing inquiry, the relentless search for meaning in a complex world. And for me, that hope lies in the continuous conversation, in the courage to keep asking questions, and in the enduring power of art to hold a mirror to our deepest uncertainties.

Richter's Enduring Questions: A Philosophical Journey

Gerhard Richter's extensive and varied oeuvre is unified by a consistent set of philosophical inquiries that he revisited and recontextualized across his many distinct periods. These are not questions he answered, but rather ones he continuously explored and invited his viewers to grapple with:

- The Nature of Truth and Representation: From his Photo Paintings to his Birkenau series, Richter relentlessly questioned the objectivity of images and the constructed nature of reality, asking: Can an image ever truly capture reality, or does it always distort it through the lens of perception, memory, or historical narrative?

- The Interplay of Control and Chance: Particularly evident in his Abstract Paintings, Richter embraced the tension between meticulous planning and the unpredictable outcomes of his squeegee technique. This inquiry extends to life itself: How much control do we truly have, and how much beauty emerges from relinquishing it to chance?

- The Subjectivity of Perception and Memory: Whether blurring photographs to mirror the fluidity of recall or creating glass works that actively incorporate the viewer's shifting perspective, Richter highlighted how personal experience profoundly shapes what we see and remember.

- The Role and Purpose of Painting in the Modern Age: In an era saturated with photography and digital media, Richter consistently reinvented painting, demonstrating its enduring relevance as a medium capable of profound conceptual inquiry and emotional resonance, often by engaging directly with these new forms.

- Art as Inquiry, Not Answer: For Richter, art is not about providing definitive solutions but about posing compelling questions. His work encourages a continuous, open-ended dialogue with the viewer, reflecting the complexities and ambiguities of existence itself.

My Continuous Journey with Richter

The more I engage with Richter’s diverse output, the more I see how each seemingly disparate phase — from the blurry Photo Paintings and the systematic abstraction of the squeegee works to the cool objectivity of his Color Charts and the reflective nature of his Glass works — is interconnected by his relentless philosophical inquiry into the nature of reality, perception, and art itself. Looking back at my personal journey with Richter, it feels less like a straight line and more like one of his abstract paintings – layers revealing themselves, unexpected colours emerging, always something new to discover. He taught me that true artistry isn't about mastering one style, but about relentlessly questioning, experimenting, and embracing the imperfect, even the uncomfortable.

His blurring reminds me that clarity isn't always the goal, and sometimes, ambiguity holds the deepest truths. This insight has been particularly influential in my own work, urging me to find beauty in the indistinct and to trust the subtle whispers of feeling over sharp definition – a lesson that often feels counter-intuitive but proves profoundly liberating. His squeegee abstracts, with their controlled chaos and inherent unpredictability, have truly freed my own approach to how to abstract art, showing me the profound beauty in relinquishing some control and trusting the process, allowing the material itself to speak. For those curious about my own explorations in this realm, some of my abstract art is for sale, a testament to how Richter's relentless questioning has informed my own artistic voice.

Richter's work doesn't just hang on a wall; it lives in your mind, shifting your perspective long after you've walked away, much like a persistent echo you can't quite shake, but wouldn't want to. Perhaps that's why he hits so hard. He doesn't offer easy answers. Instead, he offers a mirror, reflecting our own uncertainties, fragmented memories, and the ever-present dance between what we see and what we feel in a world saturated with images. His work continues to provoke and inspire, ensuring his place not just in art history, but in the ongoing conversation about what it means to see, to remember, and to create.

If this has piqued your curiosity, I highly recommend seeking out his work in person at a gallery or museum near you. The monumental scale of his abstracts, the subtle shifts of the blur in his photo paintings, or the immersive reflective quality of his glass works simply cannot be fully appreciated on a flat screen. Trust me, it’s a journey worth taking. If you're ever in the Netherlands, you might even find some of his remarkable pieces at the Den Bosch Museum. So, what will his beautiful ambiguities reveal to you about your own way of seeing the world? Dive in and discover.