Perspective in Art: An Artist's Personal Journey from Rules to Abstract Liberation

Join an abstract artist's candid exploration of perspective in art. Uncover how our brains perceive depth, delve into historical techniques, and witness how abstract art manipulates space, emotion, and visual reality. Discover a unique, introspective approach to art.

My Abstract Journey: Uncovering Depth and Perspective in Art

Sometimes, I just stop. You know that feeling? When you really, truly see the world around you, and a flicker of amazement sparks in your brain at the sheer complexity of it all. The way a distant mountain vanishes into a hazy blue, or how those railway tracks stretch out, stubbornly refusing to stay parallel, seemingly converging into a single, distant point – it's pure magic, isn't it? As an artist, especially one who often finds solace and expression in the abstract, that illusion of depth on a flat surface has always fascinated me. It’s what we call perspective, and while the Renaissance masters might have codified its rules, this "trick of the eye" is a universal language, constantly evolving. So, come with me. Let's peel back the layers of this captivating subject, not as a dusty academic lecture, but as a conversation between friends, a shared wonder, perhaps even a slightly confused but enthusiastic exploration. What if I told you that this very 'magic' is something we can not only understand, but actively manipulate on a canvas, to create entire new worlds, even in abstraction? This isn't just about technical rules; it's a profound exploration into how we see, how we feel, and how we construct our visual realities, from the strict geometry of history to the boundless freedom of contemporary abstraction. We'll navigate the psychological impact these visual choices have on you, the viewer, discovering how the canvas connects profoundly with your consciousness.

What Even IS Perspective, Anyway? (And Why Do We Care, Personally?)

At its heart, perspective in art is simply the technique artists use to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. It’s about making things look nearer or further away, larger or smaller, just as they appear to our eyes in the real world. For me, it's less about the 'how' and more about the 'why' – why do our brains fall for these tricks?

Our Brain's 3D Puzzle: Constructing Reality from Flat Information

Think about it: our eyes are constantly processing distance, size, and depth without us even consciously trying. This perception isn't just a delightful trick; it's a cornerstone of our survival, a primal ability that allowed our ancestors to judge the leap across a chasm, identify a predator lurking in the distance, or accurately aim a spear at prey. Imagine trying to catch a ball if your brain couldn't instantly process its speed and distance based on its changing size and your binocular vision – it’d be a chaotic mess! Our brains, yours and mine, aren't just passive receivers of visual data; they're active constructors, constantly piecing together fragments, filling in missing information, and even predicting what we should see. It's a beautiful, intricate dance between what our eyes see and what our brain interprets. You know that feeling when you're looking at one of those magic eye puzzles, trying to find the hidden 3D image? Our brains are doing that, but constantly, and with far more sophistication, piecing together fragments to build a coherent world. It’s also why our perception isn't entirely universal; cultural backgrounds and learned experiences can subtly shape how we interpret depth cues, making 'seeing' a wonderfully complex, individualized act.

Ever notice how your two eyes see slightly different things, creating that sense of stereopsis – the subtle magic of binocular vision that offers a richer, more detailed perception of depth by comparing those two slightly offset images? Or how distant objects appear smaller (relative size), overlap, or are higher in your visual field (relative height)? These are all cues our brains use to construct a 3D world from 2D input, actively building our perceived reality rather than passively receiving it. This active construction is key, especially when I later consider how abstract art can manipulate those very same deep-seated perceptual mechanisms to create new, unique experiences of space and depth, often evoking specific emotions or a sense of unease or wonder. This manipulation of perception can be incredibly powerful in art, intentionally creating effects that range from the deeply unsettling to the profoundly wondrous, guiding your emotional experience as much as your visual one. It's truly a profound connection between the canvas and your consciousness.

Beyond Cues: Gestalt Principles and the Mind's Shortcuts

But it's not just about individual cues. Our brains also employ broader organizational principles to make sense of the visual chaos. Think of Gestalt principles – like how we group similar objects together (similarity), or how objects that are close to each other are perceived as a single unit (proximity). Take, for instance, a series of overlapping squares; your brain doesn't just see a jumble. It intuitively groups them, interpreting the partially obscured squares as being behind the complete ones, establishing an immediate sense of depth. Or closure, where our mind fills in gaps to perceive a complete shape, even if it's only hinted at – like seeing a full circle from just a few arcs. In abstract art, I might suggest a form through incomplete lines, relying on your brain to 'close' the shape, implying a volume or presence that isn't fully rendered. And continuity, where elements arranged on a line or curve are seen as more related than elements not on the line or curve, creating implied paths or planes. I could use a broken series of dots, strategically aligned, to create a perceived 'edge' or a receding line in an abstract piece, guiding your eye along an invisible trajectory without drawing an explicit line. In my abstract work, I might intentionally use strong proximity of shapes to create a perceived 'cluster' that pushes forward, or similarity in texture to suggest a receding plane of related but distant elements, guiding your eye without any traditional vanishing points. Imagine a canvas where I’ve placed several vibrant red squares very close together in one corner, while scattering a few identical red squares sparsely across the rest of the painting. Your eye will immediately group the cluster of squares as a distinct, perhaps closer, entity, creating a subtle, immediate sense of spatial layering. These subconscious mental shortcuts help us perceive form and depth, even when the visual information is incomplete. When an artist nails perspective, they're essentially hacking your visual system, telling it, "Hey, this flat canvas? It's actually a window into another world!" And when they get it wrong, well, things can look a bit… off. Like a cartoon character with one eye on the side of their head and the other looking forward – charming in its own way, but not quite 'real', and I've certainly had my share of 'off' moments in the studio! My brain, after all, is always trying to complete the puzzle, and when a piece doesn't fit, it's jarring. How much of what you "see" is actually your brain's clever interpretation, rather than raw visual data? It's a question that never ceases to fascinate me.

A Little Trip Down Memory Lane: The History of Perspective (My Personal Take)

These subconscious shortcuts, this active construction of reality, are precisely what artists have intuitively played with throughout history, finding ingenious ways to represent or subvert what the eye perceives. For a long, long time, art didn't really bother with realistic perspective. Medieval paintings, for example, often showed important figures as larger, regardless of their actual distance from the viewer. It was more about symbolic meaning than visual accuracy. And honestly, for what they were trying to achieve, prioritizing symbolic resonance or spiritual narrative over strict optical accuracy, it was profoundly effective!

Echoes of Depth Before the Renaissance

Long before Brunelleschi, cultures had their own ingenious methods. Ancient Egyptian art, for example, used hierarchical scaling (larger figures for more importance) and overlapping to denote spatial relationships, not realistic recession. Roman frescoes experimented with rudimentary forms of linear perspective, though without the mathematical rigor of the Renaissance. Before the Renaissance, the development of oil paints also played a quiet, crucial role. Their slow drying time and ability to be layered in translucent glazes allowed artists to create unprecedented subtle gradations of light and color, laying the groundwork for more convincing atmospheric effects and richer modeling of form, even if a formal system of linear perspective hadn't yet emerged. Even Chinese landscape paintings often employed atmospheric perspective and multiple viewpoints to convey vast, intricate spaces rather than a single fixed gaze. And artists like Giotto, centuries before the Renaissance, experimented with creating more convincing, albeit intuitive, spatial boxes in his frescoes, hinting at the revolution to come. It's a reminder that 'realism' itself, what we consider visually 'true', is a culturally defined concept. I often think about how my own definition of 'real' in art has shifted over time; what felt essential years ago now feels like just one possibility among many.

The Renaissance Revelation: Unlocking a 'Secret Cheat Code'

But then, something shifted. In the early 15th century, during the Italian Renaissance, a brilliant architect named Filippo Brunelleschi started tinkering. He figured out the mathematical principles behind linear perspective, showing how parallel lines appear to converge at a single vanishing point on the horizon. This period, fueled by a renewed interest in classical antiquity, humanism, and a flourishing of scientific inquiry, saw patrons eager for art that mirrored the observable world, pushing artists towards greater realism and technical mastery. Leon Battista Alberti later codified these ideas, making them accessible to other artists. We also can't forget artists like Masaccio, whose frescoes applied these newfound principles to create astonishingly realistic architectural spaces, or Paolo Uccello, who obsessively explored the geometry of perspective in his dynamic battle scenes. It was like they discovered a secret cheat code for realism! I often imagine Brunelleschi, standing there with his mirrors and mathematical tools, a glint in his eye, the sheer awe of the crowd as he unveiled this "window into another world." It must have felt like unlocking a secret dimension, a feeling I sometimes chase in my own studio when a new technique finally clicks, transforming a flat canvas into something alive. Suddenly, paintings gained incredible depth and realism, drawing viewers into the scene in a way never before possible. Figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Piero della Francesca further refined these techniques, delving into the nuances of atmospheric perspective and anamorphosis – a clever trick that creates a distorted image which appears normal only when viewed from a particular, oblique angle, playing with our perception in a profound way. Think of the elongated skull lurking in the foreground of Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors – only revealing its true form when viewed from a specific, oblique angle. It's a fascinating memento mori that subverts and then reveals optical truth, a visual puzzle that still delights me. This mathematical rigor even influenced later developments, such as grand theatrical stage designs in the Baroque era, where elaborate backdrops created stunning illusions of deep space.

Modern Departures: Questioning the Fixed Viewpoint

The advent of photography in the 19th century further revolutionized how we understand and depict perspective. The camera's lens offered a mechanically precise, fixed viewpoint, influencing painters to either emulate this new 'realism' or actively rebel against it. Interestingly, early photographers often composed their shots with an eye towards the established 'rules' of painting, creating a fascinating feedback loop between the two mediums. Later, film and cinematography pushed boundaries further, allowing for dynamic perspectives, deep focus, and wide-angle distortions that became part of the visual language we now take for granted, subtly shaping our collective visual grammar. Moreover, the influx of Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e) into Europe in the mid-19th century profoundly influenced Western artists. Their use of flattened planes, bold outlines, unconventional cropping, and multiple viewpoints offered radical alternatives to Western linear perspective, deeply inspiring Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh and Impressionists like Degas to explore new ways of composing space. And even much later, artists like Paul Cézanne began to subtly question and fragment Renaissance perspective, breaking down forms into geometric components and showing objects from multiple angles, foreshadowing the seismic shifts of the 20th century. Before Matisse, Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, in works that flattened space for emotional intensity, or Paul Gauguin, with his symbolic, non-naturalistic color and forms, were already pushing against strict representational depth. Sometimes, artists even intentionally play with perspective for comedic or unsettling effect, like the delightful 'wrongness' in a M.C. Escher print or the distorted realities in a Salvador Dalí. This rich history shows us that perspective isn't a static concept, but a dynamic toolkit that artists continually adapt and redefine. And if you're eager to delve even deeper into this evolution, from Renaissance innovation to modern subversion, you might find my thoughts on the definitive guide to understanding perspective in art from renaissance to modern abstraction a compelling next step. Thinking about all these shifts, what historical development do you believe most profoundly altered how artists approach perspective?

Key Types of Perspective: The Artist's Toolkit (And My Favorites to Subvert)

Having explored the historical evolution of perspective, let's now delve into the specific tools artists have employed to conjure illusions of depth. From precise calculations to atmospheric whispers, artists have many ways to play with depth. Here are a few that often pop up, and how I sometimes think about them in my own practice:

Linear Perspective (The Classic Illusionist)

This is the big one, the one that relies on mathematical principles. It's all about vanishing points (where parallel lines seem to meet) and a horizon line (your eye level). We typically talk about:

- One-Point Perspective: Think of a long road stretching directly away from you, a single-lane tunnel, a long pier stretching out into the ocean, or even the view down a perfectly aligned train track. Everything recedes to a single point, creating a sense of directness, a powerful focus, or even a tunnel-like claustrophobia. It's great for creating a sense of directness or infinite depth.

- Two-Point Perspective: Imagine looking at the corner of a building from the street, or a book sitting open on a table, revealing two sides receding away. Now you have two vanishing points, one for each receding side. This adds more dynamism and a less rigid feel, feeling more dynamic and open, inviting the viewer to explore around a form.

- Three-Point Perspective: This one introduces a third vanishing point, usually above or below, to account for extreme up or down views, like looking up at a towering skyscraper from the sidewalk, or down from a helicopter at a sprawling cityscape. It’s a bit more advanced and can make you feel a bit dizzy if not handled well, evoking a sense of awe, grandeur, or even a dizzying instability! I remember trying to draw buildings in high school, meticulously measuring and extending lines, feeling a mix of frustration and profound satisfaction when it finally clicked. It's like solving a visual puzzle, albeit one that sometimes makes your eyes cross.

Atmospheric or Aerial Perspective (The Subtle Whisperer)

This type of perspective isn't about lines, but about how the atmosphere affects our perception of distant objects. Things far away tend to appear:

- Lighter and less saturated: Colors become muted.

- Less detailed: Fine features blur.

- Bluer or grayer: The air itself acts as a filter.

Think of a landscape with rolling hills. The closest ones are sharp and vibrant, but the ones in the far distance are soft, hazy, and tinged with blue. I often use this principle subconsciously even in my abstract works, playing with color intensity to suggest depth. It’s a lovely, almost poetic way to create a sense of vastness, evoking a calm or even melancholic mood. It’s often used in conjunction with linear perspective to create a more believable and immersive sense of a vast, natural world. What natural phenomenon have you observed that perfectly illustrates atmospheric perspective?

Oblique, Axonometric, and Isometric Perspective (The Precise Alternatives)

These are often seen in architectural drawings, technical illustrations, or video games. Unlike linear perspective, they don't use vanishing points, which means parallel lines remain parallel. This is a key difference: while linear perspective relies on central projection (imagine light rays converging to a single eye point, like a camera lens), these systems use parallel projection (where light rays are assumed to be parallel, like a distant sun casting uniform shadows). This absence of optical distortion means that while they might appear a bit 'stylized' or 'less immediately naturalistic' to an eye trained on Renaissance realism, they are incredibly useful for maintaining accurate measurements and proportions. Think of it like looking at a technical blueprint, an instruction manual diagram, or an old-school isometric role-playing game where maintaining spatial clarity is more important than optical realism. These types of projection were also crucial in the early days of computer graphics for rendering objects with consistent scale. It’s about a different kind of 'truth' – a functional, measurable truth, rather than an optical one. While often grouped, each offers a unique take: Isometric projection, a specific type of axonometric, uses three axes set at 120 degrees, maintaining consistent scale along them – ideal for precise technical drawings. Oblique projection, in contrast, allows one face of the object to be parallel to the plane of projection, while the receding lines are drawn at an angle, giving a slightly more 'front-on' feel. Think of how these precise methods are chosen not for visual trickery, but for clarity and fidelity in design. In contemporary abstract art, I sometimes find myself drawn to these methods for creating a sense of controlled, almost architectural abstraction, where forms exist in a clear, measurable relationship without the emotional pull of a vanishing point. Artists like Sol LeWitt in his geometric wall drawings, or the minimalist sculptures of Donald Judd, often employ principles akin to axonometric projection to create a sense of ordered, precisely defined space, albeit without the explicit goal of optical illusion. I might, for instance, create a series of stacked, offset cubes that feel structurally sound and measurable, even as they float in an ambiguous, colored void, inviting you to imagine their construction rather than their recession.

Curvilinear Perspective (The Embracer of Curves)

And if these precise alternatives offer a functional truth, then curvilinear perspective offers another kind of truth – one that embraces the natural curve of our vision or an exaggerated artistic vision. While less common in traditional painting, curvilinear perspective acknowledges that our peripheral vision isn't flat. Think of a fisheye lens, or the way a wide panoramic photograph subtly curves. This isn't a mistake; it's a deliberate artistic choice to mimic what we see through a curved lens, or to create a more immersive, all-encompassing view that warps straight lines and creates an almost dizzying sense of expansion or enclosure, mirroring the natural curvature of our peripheral vision or to evoke specific psychological states. Artists like M.C. Escher, though known for impossible constructions, sometimes used curvilinear elements to enhance the feeling of warped or infinite spaces. Beyond Escher, you see its spirit in panoramic photography, wide-angle lens effects in film, and even certain immersive digital art installations that wrap the viewer in a distorted field of vision, mirroring the natural curvature of our peripheral sight or emphasizing an expansive, dreamlike state. In abstract art, I might intentionally distort lines or horizons, perhaps through the use of curved canvases or painted elements that bend and arc, to create a feeling of movement, instability, or a dreamlike, expansive sensation that challenges the static flatness of the canvas. Imagine a piece where the very 'edges' of the composition seem to bow outwards, as if the painting is trying to hug you, pulling you into its soft, distorted depths. Or perhaps a series of geometric forms that, instead of receding straight back, curve around a central point, creating a 'tunnel' or 'fisheye' effect within the abstract space, inviting you to literally 'fall' into its warped, yet cohesive, logic.

Light and Shadow (Chiaroscuro): Sculpting Volume

While not a type of perspective in itself, the masterful use of light and shadow, known as chiaroscuro, is a fundamental technique for creating the illusion of volume and depth. By dramatically contrasting light and dark areas, artists can make objects appear to recede or advance, creating a powerful three-dimensional presence on a two-dimensional surface. Think of the intense drama of a Caravaggio painting, where figures seem to emerge from deep shadow. Even in my abstract work, I use stark contrasts of light and dark, or subtle gradations within a single color, to give shapes a sense of weight, form, and spatial anchoring, making them feel like tangible entities rather than flat cutouts. A bright highlight on one side of an abstract form, fading into a deep shadow on the other, instantly creates a sense of its three-dimensional existence, even if the form itself is purely imagined.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/42803050@N00/31171785864, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/

Forced Perspective (The Playful Manipulator)

While not strictly a drawing technique for canvases, forced perspective is worth a mention for its sheer cleverness. It’s an optical illusion that makes an object appear farther away, closer, larger, or smaller than it actually is, by manipulating the viewer's visual cues. Think of tourist photos 'holding up' the Leaning Tower of Pisa, or film sets that make miniatures look monumental. It’s a playful, often humorous, manipulation of perceived scale and distance that relies entirely on understanding how our brains interpret depth. In abstract art, I might evoke a sense of forced perspective by dramatically manipulating the relative scale of elements or placing them in unexpected juxtapositions, creating a visual 'trick' that makes you question distances and relationships, even without a literal scene. For example, a tiny, sharply defined form set against an overwhelmingly vast, soft-edged color field can create a disorienting sense of scale, making the small feel monumental and the monumental feel like an infinite void, forcing your eye to adjust its assumptions. What other clever ways have artists found to trick the eye?

To summarize these key distinctions, here's a quick reference:

Perspective Type |

|---|

| Linear |

| Atmospheric |

| Oblique/Axonometric/Isometric |

| Curvilinear |

| Forced |

| Chiaroscuro |

These tools are incredibly powerful, capable of conjuring entire worlds on a flat surface. But sometimes, as I've found, the very rules that grant us such control can also feel like a beautiful burden, a set of strictures that occasionally chafe against the desire for unbridled expression. Which of these tools do you find most intriguing for abstract exploration, and why?

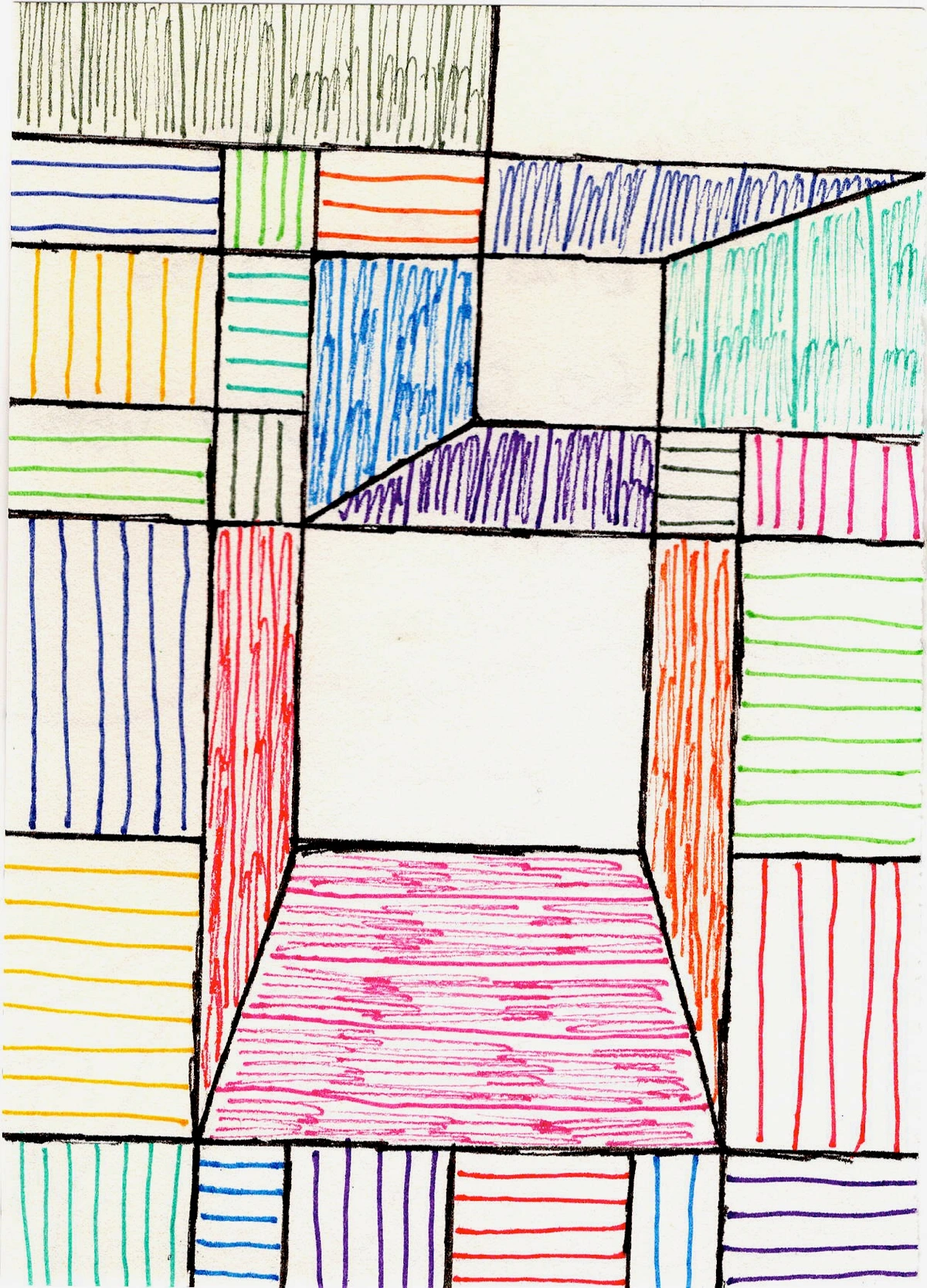

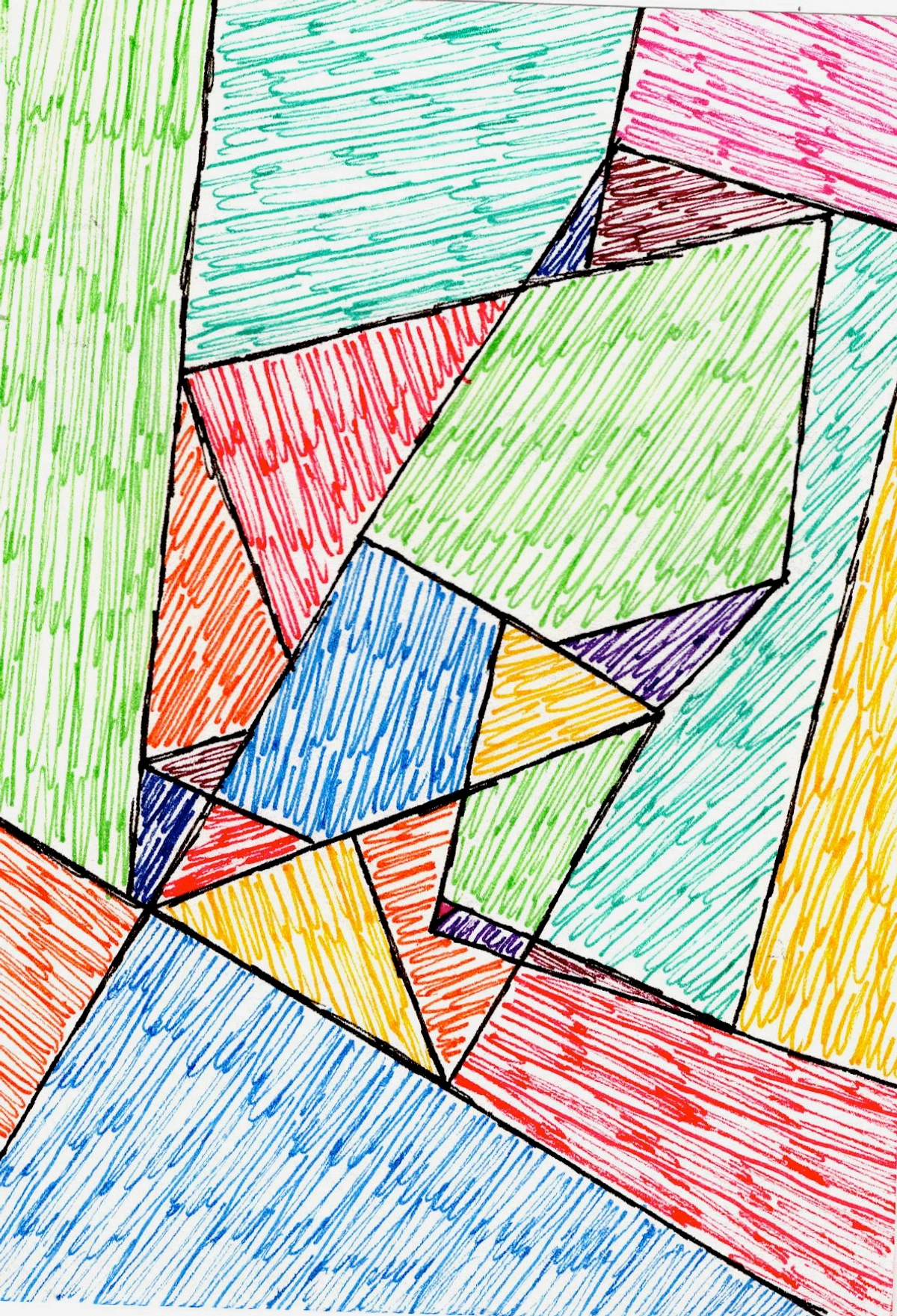

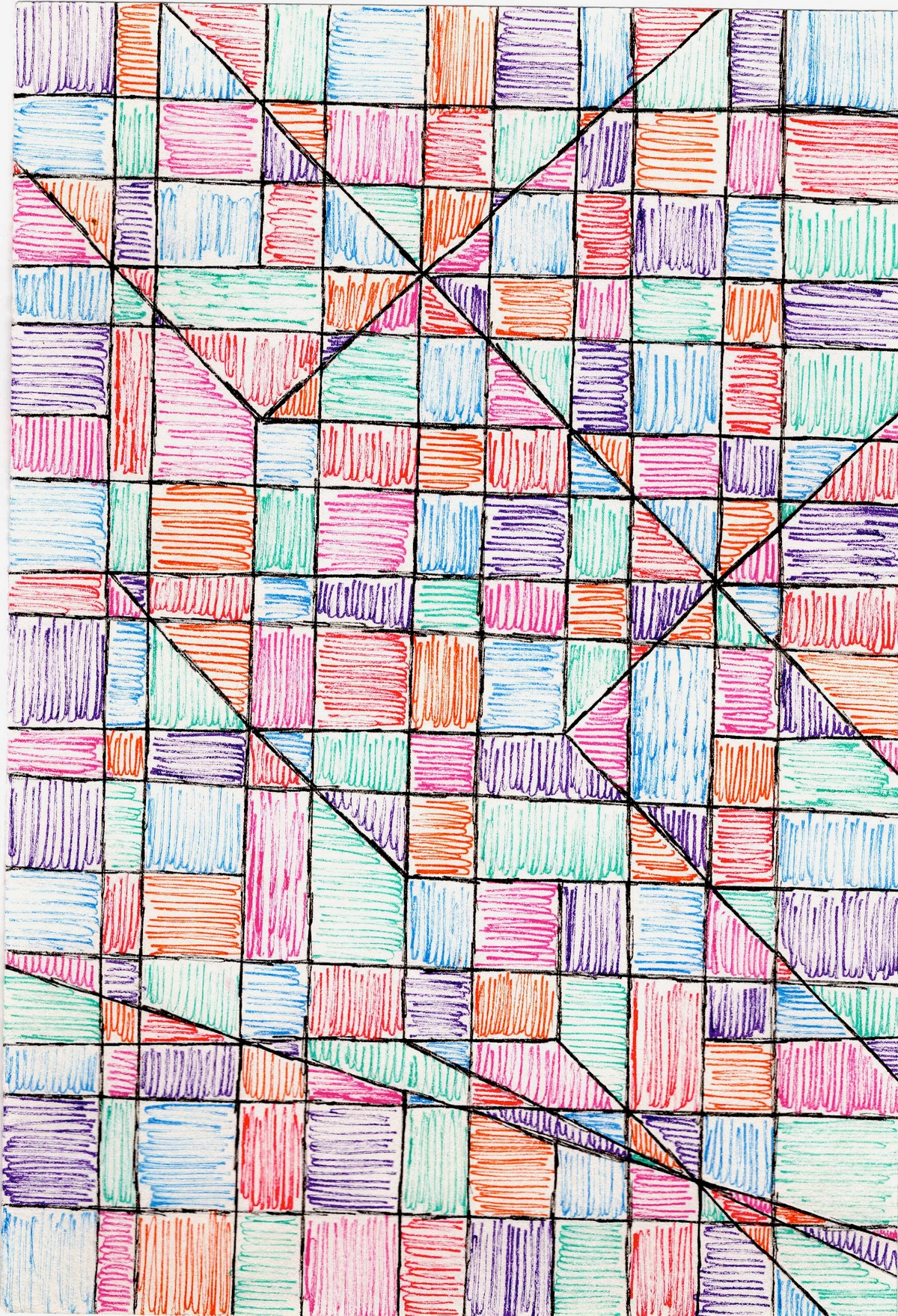

Beyond the Rules: When Abstract Art Reimagines Depth (My Liberation)

For me, as an abstract artist, the true liberation began when I started to see perspective not as a set of rigid rules, but as a playground of possibilities. My canvas often ignores the obvious, not out of ignorance, but out of a deliberate choice to explore a different kind of visual truth. Perspective isn't about perfectly rendered spaces; it's about the feeling of space, the suggestion of depth, the way elements interact to create a visual journey that isn't bound by a single viewpoint. It's a complete reimagining, a playground where the rules of reality bend to the will of emotion and intuition.

Sometimes, though, the very rules that grant us such control over illusion can start to feel like a cage, a beautiful but ultimately limiting framework. For me, the beauty of art isn't always in replicating reality, but in interpreting it, or even reimagining it entirely. What happens when you want to convey emotion or a conceptual idea that doesn't fit neatly into converging lines or fading horizons? I've found that sometimes, the precise geometry of traditional perspective can actually distract from the deeper emotional truth I'm trying to express. I remember one particular piece, a landscape I was attempting in my early days, where the rigid lines of a vanishing point felt like a physical barrier, preventing the raw, emotional energy of the storm I wanted to capture from breaking free. It was then I realized the beauty wasn't just in the replication, but in the reimagining. There have been moments in my studio, canvas staring back, where I felt trapped by the expectation of 'correct' depth, a mental straightjacket preventing the true feeling from emerging. This is where the dance truly begins – the dance between understanding the rules and knowing when, and how, to break them with intention.

Challenging Reality: How Abstract Artists Rebuild Space

Abstract artists intentionally manipulate or even outright defy traditional perspective to achieve different effects. Think of how a Cubist artist like Picasso might show a face from multiple angles simultaneously – fragmenting and reassembling forms to explicitly challenge single-point perspective and force you to see in a new, fractured way, reflecting a more complex, multi-faceted reality by breaking the illusion of a single, fixed viewpoint. This concept of "simultanity" was a radical departure, demanding a new way of seeing. Or consider the dreamlike, unsettling spaces created by Surrealists like Salvador Dalí, where perspective is distorted – perhaps a vast, empty landscape extending to an impossibly distant horizon, as seen in "The Persistence of Memory," creating a psychological space that mirrors the irrationality and fluid logic of the subconscious mind.

Even in movements like Abstract Expressionism or Color Field painting, while not explicitly using linear perspective, artists manipulate scale, color saturation, and texture to evoke immense, immersive spaces, or flat, confrontational surfaces. Consider the radical spatial explorations of Suprematist artists like Kazimir Malevich, whose 'Black Square' challenged traditional notions of space by presenting a pure, non-objective form, or the Constructivists who built dynamic, three-dimensional structures that redefined how art could occupy and interact with real space, often using geometric abstraction to build new, rather than depict existing, realities. Think of Mark Rothko's monumental color fields; their sheer size, pulsating hues, and the vibrating edges where colors meet (often through subtle shifts in value or color temperature, creating effects akin to optical mixing) don't depict a specific place, but they create an overwhelming, spiritual, or melancholic space around and within you, compelling you to immerse yourself in their emotional depth, often by filling your peripheral vision. This guides the viewer's emotional journey through non-representational means.

It’s about creating a universe with its own internal logic, where psychological or emotional space takes precedence over optical accuracy. This might manifest as a feeling of compression, expansion, or even an illogical layering that makes you question what you're seeing. It’s also crucial to acknowledge that your own physical position relative to the artwork can dramatically alter your perception of these abstract spaces, especially in large-scale works or installations. You can explore more about these movements in the definitive guide to understanding abstract art from cubism to contemporary expression. So, as you delve into abstract art, what 'rules' of perception do you find yourself questioning, or even joyfully breaking, to find new meaning?

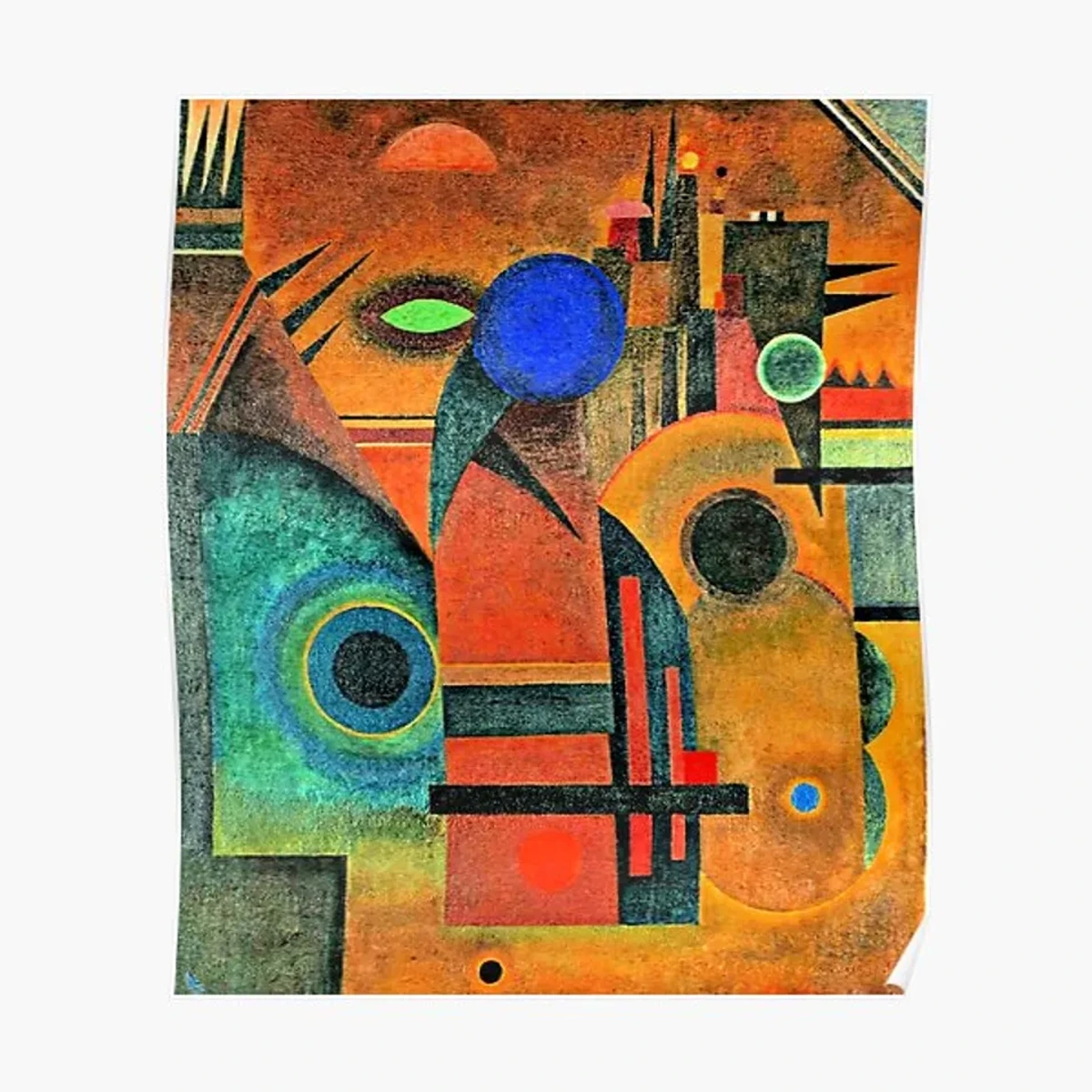

The Quiet Rebellion: Artists Deliberately Flattening Space

My own artistic heroes often found their freedom in similar acts of defiance. Artists like Henri Matisse, with his 'The Red Room' (Harmony in Red), deliberately flattened space and used color to create a different kind of visual order, prioritizing emotional impact over realistic depth, boldly challenging the very notion of a single, fixed viewpoint. Notice how the vibrant red of the walls extends onto the table, and the patterns seem to ignore any traditional recession, creating an inviting, enveloping surface rather than an illusion of deep space. Similarly, artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, pioneers of abstraction, often ignored traditional perspective entirely, allowing lines, shapes, and colors to create their own emotional and spiritual spaces, valuing subjective experience over objective reality.

https://live.staticflickr.com/4073/4811188791_e528d37dae_b.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Printerval.com, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

My own work often relies heavily on layering, creating a tactile depth that isn't about distance but about planes interacting. A sharp edge against a soft wash, a transparent layer over an opaque one – these create their own spatial narratives, guiding the eye without traditional vanishing points. It’s a process I delve into more in my process of building depth and narrative in abstract mixed media.

Just like atmospheric perspective uses color and value to suggest distance, abstract artists harness the inherent 'push and pull' of colors. Warm colors tend to advance, cool colors recede. High contrast can bring elements forward, while muted tones push them back. It's a psychological and optical game I play with every palette choice, guiding your eye through the work. If you're curious about this, I've written more on my approach to palette and emotion.

Manipulating scale, making a small element feel monumental or a large one insignificant, creates a sense of space that is emotional rather than realistic. And sometimes, the goal isn't clarity but intriguing ambiguity. Is that shape in front or behind? Is it floating or anchored? This deliberate questioning of space invites the viewer to participate, to complete the picture in their own mind. This intentional manipulation of space, where I craft a unique visual journey for you, is the pure joy of my artistic practice. It's freeing, exhilarating, and allows for infinite possibilities. It's how I build my own worlds, full of color and movement, which you can explore in my art for sale.

Putting Perspective into Practice: My Abstract Toolkit

Even in abstraction, understanding these fundamental principles is like knowing the rules of grammar before you write poetry. It allows you to break them with intention, not by accident. Here's how I often approach "perspective" in my own work, transforming classical ideas into my unique visual language:

- Start with a Flat Plane, Then Introduce Depth: I rarely begin with a vanishing point. Instead, I build layers. First a wash, then a gesture, then a solid shape. Each layer adds to the perceived depth, like digging through archaeological strata. For example, a soft, translucent layer underneath a vibrant, opaque form immediately suggests the latter is closer, transforming a flat surface into a perceived space. There was one time I was experimenting with a faint, almost ghost-like wash of blue across an entire canvas, then overlaid it with sharp, bold black lines. The blue instantly receded, creating an unexpected cavernous depth that felt both serene and dramatic, evoking the vastness of an open sky or a deep ocean trench. This approach helps me create a rich, multi-dimensional surface without resorting to literal depth. I might begin with a large, diffuse cloud of cerulean, then add a series of crisp, overlapping geometric forms in crimson and gold. The cerulean background instantly feels distant, a deep sky or ocean, while the sharp forms assert themselves in the foreground, creating a dynamic, yet non-representational, spatial narrative. I also consider texture here; rougher, more tactile textures tend to advance, drawing the eye forward, while smoother, more refined surfaces recede. This interplay of tactile qualities adds another dimension to perceived depth.

- Embrace Overlapping: Simple overlaps are incredibly powerful. Even in abstract forms, one shape slightly covering another instantly creates a foreground and background. It's an intuitive way to establish spatial relationships, mimicking how objects in real space occlude each other. In a recent piece, I had a large, muted orange shape that felt too dominant. By placing a smaller, more vibrant blue form partially over its edge, the orange instantly pulled back, becoming a vast backdrop, while the blue leaped forward, defining the immediate space. It's a subtle trick that works every time.

- Play with Edge Quality: Sharp, defined edges tend to advance; soft, blurred edges recede. It's a subtle trick, but incredibly effective in manipulating where the eye focuses and how it interprets closeness or distance. I often use a crisp, hard-edged line to bring a form aggressively forward, contrasting it with a hazy, brushed edge on an adjacent shape that melts into the background, like a distant cloud or a fading memory, creating a dynamic push-and-pull within the composition.

- Harness Color and Value Contrasts: My color choices aren't random; they're designed to create pushes and pulls, defining spatial relationships. Dark against light, vibrant against muted – these juxtapositions are key to creating dynamic depth in my compositions, a technique elaborated in my approach to palette and emotion. This inherent 'push and pull' of colors, where warm hues advance and cool hues recede, becomes a powerful, almost subconscious tool for guiding the viewer's eye through the spatial journey of the painting. I've found that a bright red shape can sing forward against a deep indigo background, even without any other traditional depth cues, simply because of its inherent chromatic energy. This includes effects like simultaneous contrast, where adjacent colors influence each other's appearance, often intensifying the 'push' or 'pull' of elements and creating a more vibrant, spatially dynamic composition.

- Utilize Negative Space: The empty or unoccupied areas around and between objects are just as important as the forms themselves. By carefully shaping these negative spaces – the empty or unoccupied areas around and between forms – I can imply forms, create a sense of enclosure or openness, and guide the eye to perceive depth and spatial relationships that aren't explicitly drawn. It’s like sculpting the air around my subjects, making the shape of the 'nothing' just as important as the 'something' in defining space and form. This allows the viewer's mind to actively complete the picture, filling in the blanks. Sometimes, a carefully crafted void between two energetic forms can create a powerful, silent tension or a sense of vast breathing room, pulling the eye into an imagined deep well or an infinite, expanding expanse. For example, if I paint a bold, irregular shape, and then surround it with an equally compelling 'empty' space, that void itself becomes a shape, pushing the primary form forward and creating an immediate sense of shallow depth, like a jewel sitting on velvet.

- Intuition over Calculation: While I understand linear perspective, my abstract process is far more intuitive. It's about feeling the balance of forms, the emotional weight of colors, and letting the composition guide the eye through the 'space' I'm creating. There was one time I was working on a piece and a perfectly placed accidental drip of paint, though defying all "rules," suddenly created an unexpected and powerful sense of recession, pulling the eye deep into the canvas – a moment of pure serendipity that a ruler could never predict. It’s a constant experiment, a constant experiment, a search for that 'aha!' moment where the canvas breathes with its own internal depth – though sometimes it feels more like an 'uh-oh!' moment where I've just painted myself into a corner, both literally and figuratively! But even those moments are part of the journey, teaching me to trust the unexpected insights that arise when I step away from rigid plans. If you're curious about this intuitive process, I share more in my journey of artistic evolution.

- Manipulate Scale for Emotional Impact: The sheer size of a canvas, or the relative scale of elements within it, profoundly influences how depth is perceived. A monumental work can envelop you, creating an immersive, almost physical sensation of space, while a miniature piece draws you into an intimate, contained world. I often play with this, making a tiny, intense detail feel like a distant star in a vast cosmos, or blowing up a seemingly insignificant mark to dominate a canvas, forcing you to confront its presence and question its proximity, perhaps evoking a feeling of sublime insignificance or overwhelming presence.

These techniques allow me to invite viewers into a unique visual landscape, where the illusion of space is felt, rather than strictly measured. It's about creating an experience, a journey through form and color, rather than a mere representation of the external world. If you want to delve deeper into how compositional elements guide the viewer's eye, check out my guide to composition in abstract art. How do these abstract 'rules' resonate with your own way of seeing and creating, or even just appreciating art?

The Limitations of Perspective (And the Boundless Freedom They Offer)

Even with all its power, traditional perspective has its limitations. It inherently imposes a single, fixed viewpoint, often a rigid frame through which to see the world. But what if the world isn't fixed? What if emotion, memory, or a multi-faceted truth needs more than a single vanishing point? This is where the so-called 'limitations' become boundless avenues for artistic freedom, allowing artists to explore a richer spectrum of human experience. By deliberately subverting, exaggerating, or ignoring traditional perspective, artists can:

- Emphasize symbolic meaning: Like medieval painters, making important figures larger regardless of distance, conveying spiritual or social hierarchy.

- Convey psychological states: Distorting space to reflect inner turmoil or dreamscapes, as seen in Surrealism, evoking unease or wonder.

- Challenge conventional reality: Presenting multiple viewpoints simultaneously, as in Cubism (the principle of "simultanity"), or even employing non-Euclidean geometry and impossible spaces (like those in Escher's work, but applied abstractly) to show a more complex, fragmented truth and stimulate new ways of seeing.

- Create immersive experiences: Using curvilinear forms, large-scale installations, or the overwhelming scale and color of abstract works to envelop the viewer, breaking the traditional frame and drawing them into a manipulated, often psychological, reality.

For me, these limitations aren't roadblocks; they're invitations to innovate, to push past what is merely seen and explore what is felt. They allow me to build worlds that might not be optically 'real' but are emotionally true, creating a deeper, more personal connection with the viewer. In the digital age, artists and designers working with 3D rendering and virtual reality continue to challenge and expand these traditional notions, creating environments where perspective itself can be dynamic and interactive, often exploring concepts of non-Euclidean geometry to create truly alien or fantastical spaces that defy our ingrained understanding of 'straight' and 'flat'. From interactive virtual galleries that warp space as you move, to augmented reality pieces that overlay digital depth onto the physical world, these technologies are pushing us to rethink what 'seeing' and 'experiencing space' truly mean. So, the next time you encounter an artwork that challenges your sense of space, lean into that disorientation – it might just be the artist's invitation to see the world anew. What new possibilities do you think these digital tools and concepts like non-Euclidean geometry bring to the conversation about perspective and how we experience art?

Concluding Thoughts: A World of Depth in Every View (And My Invitation to You)

From the meticulous calculations of the Renaissance to the intuitive layers of abstract expressionism, perspective in art is an endlessly fascinating subject. For me, it's a profound testament to how the human mind, and the artist's hand, can conjure and perceive entire worlds of depth and meaning on a flat surface, often without a single vanishing point in sight. It's a constant dialogue between the rules I've learned and the freedom I crave, a journey of discovery that continually reshapes how I understand and create depth. Whether you're meticulously rendering a street scene or intuitively layering colors on a canvas, the pursuit of depth, of leading the eye through a visual experience, is one of art's oldest and most captivating games. It reminds us that even on a flat surface, with a little intentional magic, the human imagination can conjure and perceive entire worlds of profound depth. It's a dialogue I'm constantly having with my own work, and one I sincerely hope you'll now join.

I hope this exploration has given you a fresh lens through which to view both the masterpieces of the past and the vibrant, often surprising, works of contemporary art. So next time you encounter a piece of art, take a moment. Don't just look at it, but look into it. Feel the depth, question the space, and let your eyes take their own journey – you might just discover an entirely new dimension of appreciation, or perhaps be inspired to create your own unique perspectives! If you’re curious to see how I translate these abstract ideas of perspective into tangible art, I warmly invite you to explore my art for sale. Or, if you ever find yourself in the charming city of 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, please feel free to visit my museum, where you can experience these layers and depths firsthand, and perhaps share your own thoughts on the magic of perspective. I’d genuinely love to hear them.