The Definitive Guide to Abstract Art Movements: From Early Pioneers to Contemporary Trends

Sometimes, I stand before a blank canvas, or even just watch the clouds drift, and I feel a stirring, a sense of possibilities, shapes, and feelings that aren't quite 'real' in the conventional sense. It's much like abstract art itself – a dive into the non-representational, a journey beyond what our eyes traditionally expect. If you've ever felt a similar pull, or perhaps a touch of bewilderment, then you're in good company. This isn't just a historical overview; it's an invitation to embark on a journey through the vibrant, often revolutionary, world of abstract art movements. We'll explore their defining characteristics, most influential artists, and enduring impact on how we perceive art and the world. It’s a quest for understanding, a challenge to our perceptions, and perhaps, a mirror to our own inner landscapes, much like my own artistic timeline reflects a continuous search for expression and understanding of what is abstract art.

The Birth of a Revolution: Why Abstract Art Emerged

It’s truly a peculiar thing, isn't it? For centuries, art's primary role was to capture reality – creating portraits that perfectly mirrored a person, or landscapes you could almost step into. Then, as the 20th century dawned, something profound shifted. This wasn't a singular "eureka!" moment, but a complex tapestry of interconnected rebellions and innovations, profoundly shaped by the seismic changes of the era. The rapid advancements in new technologies—beyond just photography, consider the X-ray revealing hidden structures, or cinema introducing fragmented, dynamic views of reality—the relentless march of industrialization, and groundbreaking scientific discoveries that unveiled invisible forces and shattered notions of fixed realities (think Einstein's relativity reshaping our understanding of space and time, or Freud's subconscious mind hinting at unseen depths) all played a crucial part.

Even deeper, philosophical shifts were at play, moving away from strict positivism towards a greater emphasis on subjective experience, intuition, and the 'life force' espoused by thinkers like Henri Bergson. Artists, perhaps feeling a profound sense of an unraveling reality, or simply tired of mere representation, found these new ideas directly fueling their desire to visualize non-material dimensions. "What if art," they began to ask, with a mix of audacious curiosity and spiritual yearning, "could speak directly to the soul, bypassing the need for recognizable forms?" This profound questioning paved the way for a deeper history of abstract art, a move towards a language of pure form and color that could communicate what words and literal images could not. It was a time when the very fabric of reality seemed to be unraveling and re-stitching itself in new, unpredictable ways, and artists sought a new visual vocabulary to match.

Shattering Convention: Early Paths to Abstraction

Imagine a world where critics (and indeed, many viewers) scoffed at anything that wasn't a perfect depiction of life. These early abstract artists, driven by an inner vision, pushed forward anyway. It reminds me a bit of when I first started experimenting with purely abstract compositions in my own studio – there’s a certain vulnerability in presenting something that doesn’t 'look like anything' but feels profoundly meaningful to you. They had the audacity to redefine art itself, setting the stage for what would become some of the most influential art movements of the 20th century.

Cubism (c. 1907-1914): Deconstructing Reality

Ah, Cubism! When I first encountered Pablo Picasso's work, like his seminal "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" (1907), I thought, "Did someone drop the canvas?" But then you start to see the method in the madness. Rather than showing an object from one viewpoint, Cubists like Picasso and Georges Braque broke objects down into geometric shapes and reassembled them, showing multiple perspectives simultaneously. This approach was deeply influenced by the geometric simplification found in African and Iberian sculpture, whose directness and departure from Western naturalism resonated with artists seeking new visual languages. It also drew inspiration from the late works of Paul Cézanne, who had already begun to break down forms into their fundamental geometric components and to explore how perception of objects changed from different angles. Cubism allowed artists to explore form and space in entirely new ways. It was less about what you saw (perception) and more about what you knew to be true about an object conceptually, presenting a more complete, albeit fractured, understanding. It was revolutionary, fractured, and fascinating – a true intellectual challenge to the very idea of pictorial space.

Futurism (c. 1909-1916): Speed, Technology, and Dynamic Energy

While not purely abstract, Futurism certainly paved the way for abstraction, particularly in its embrace of dynamism and movement. Italian artists like Umberto Boccioni, with works like his iconic "Unique Forms of Continuity in Space" (1913), were obsessed with speed, technology, and the energy of modern life. They tried to capture motion itself, blurring forms and using lines of force (diagonal lines and visual pathways indicating movement) or simultaneity (showing multiple moments in time or perspectives at once) to convey a sense of rushing forward. It’s like trying to photograph a speeding train with a long exposure, or capturing the frantic energy of a city street in a single, vibrating image – you get streaks of light, a sense of kinetic energy, not a perfectly crisp still. Their manifestos championed the destruction of past artistic traditions and embraced the machine age, forever changing how artists thought about portraying time and space, and directly influencing later abstract movements that sought to depict energy and a fragmented reality. They wanted to inject life and raw energy into static art.

Orphism (c. 1910-1913): The Lyrical Power of Color

Emerging concurrently with some of these initial ruptures, Orphism, championed by artists like Robert Delaunay, offered a crucial bridge towards pure abstraction primarily through the expressive power of color. While retaining some figurative elements initially, Orphists focused on creating dynamic compositions using overlapping, translucent geometric shapes and vibrant, contrasting colors. They believed color itself could evoke emotion and convey movement, much like music – a symphony of hues and forms, moving beyond Cubism's more muted palette and analytical, form-based approach. It was, for them, a journey into the lyrical, a celebration of light and rhythm, aiming to create harmony through color relationships. I find myself returning to this idea often in my own work, exploring the emotional language of color in abstract art.

European Pioneers: The Quest for Pure Feeling and Universal Order

Even before Abstract Expressionism found its explosive voice in America, European artists were already grappling with abstraction as a means of expressing inner states and constructing new realities. This quest for internal truth resonates deeply with my own artistic process; sometimes, the canvas just needs to feel right, rather than look right, as if it’s tapping into a hidden layer of existence. This era was also heavily influenced by esoteric philosophies, notably Theosophy, which posited an underlying spiritual reality behind the material world, advocating for universal brotherhood and the evolution of human consciousness. This spiritual yearning fueled many artists' desire to visualize the unseen, to capture universal vibrations and cosmic truths through abstract forms.

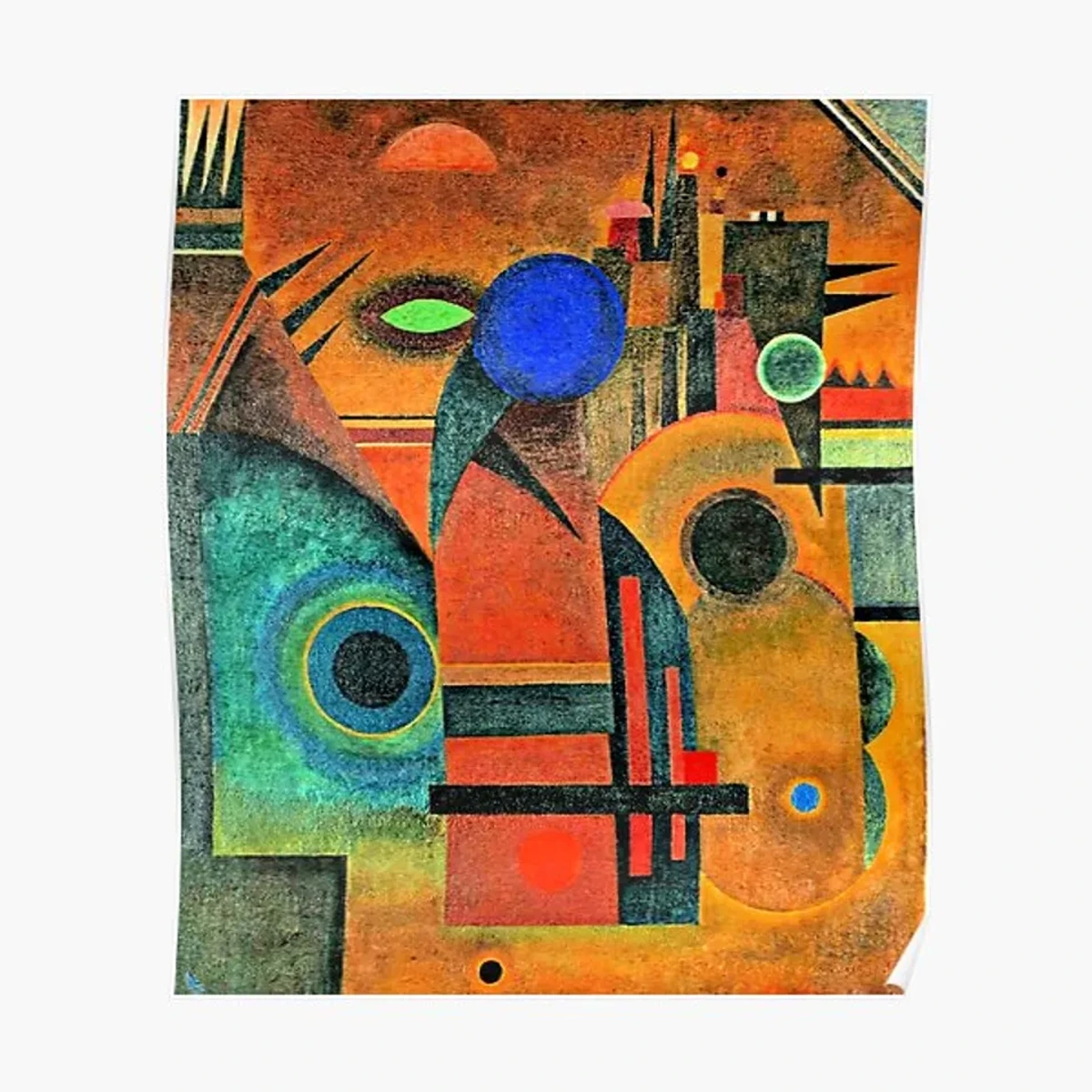

Wassily Kandinsky and Early Expressionism (c. 1910 onwards): Inner Necessity and Spiritual Abstraction

Often credited with creating the first purely abstract paintings, Wassily Kandinsky believed art should express the 'inner necessity' of the artist, much like music expresses emotion through sound. For him, colors and shapes could evoke emotions and spiritual states directly, akin to synesthesia, where one sense (sight) translates to another (feeling, sound). His early forays into abstraction, often associated with broader Expressionism, sought to liberate color and form from their descriptive duties, allowing them to communicate profound internal experiences and spiritual aspirations. Kandinsky's influential treatise, "Concerning the Spiritual in Art" (1911), articulated his theories on art as a spiritual language, advocating for a non-objective art that could transcend the material world. Works like "Composition VII" (1913) are a testament to his belief that art could reach for a spiritual realm, a concept deeply tied to his interest in Theosophy.

Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism (c. 1913 onwards): The Supremacy of Pure Feeling

Around the same time, Russian artist Kazimir Malevich introduced Suprematism, an art movement focused on fundamental geometric forms (squares, circles, triangles) painted in a limited range of colors. Malevich, also deeply influenced by spiritual ideas like Theosophy, sought to express "the supremacy of pure feeling or perception in pictorial art," reducing painting to its most basic visual elements to achieve a spiritual purity. He aimed to access what he called "the zero of form"—a state of pure, non-objective sensation beyond any worldly reference—to create a universal, unadulterated visual language. His iconic "Black Square" (1915) is a powerful symbol of this radical reduction to essence, a statement about the potential of non-objective art to convey profound truth and an almost cosmic void, transcending the material world entirely. It was a bold, almost confrontational act of artistic purification.

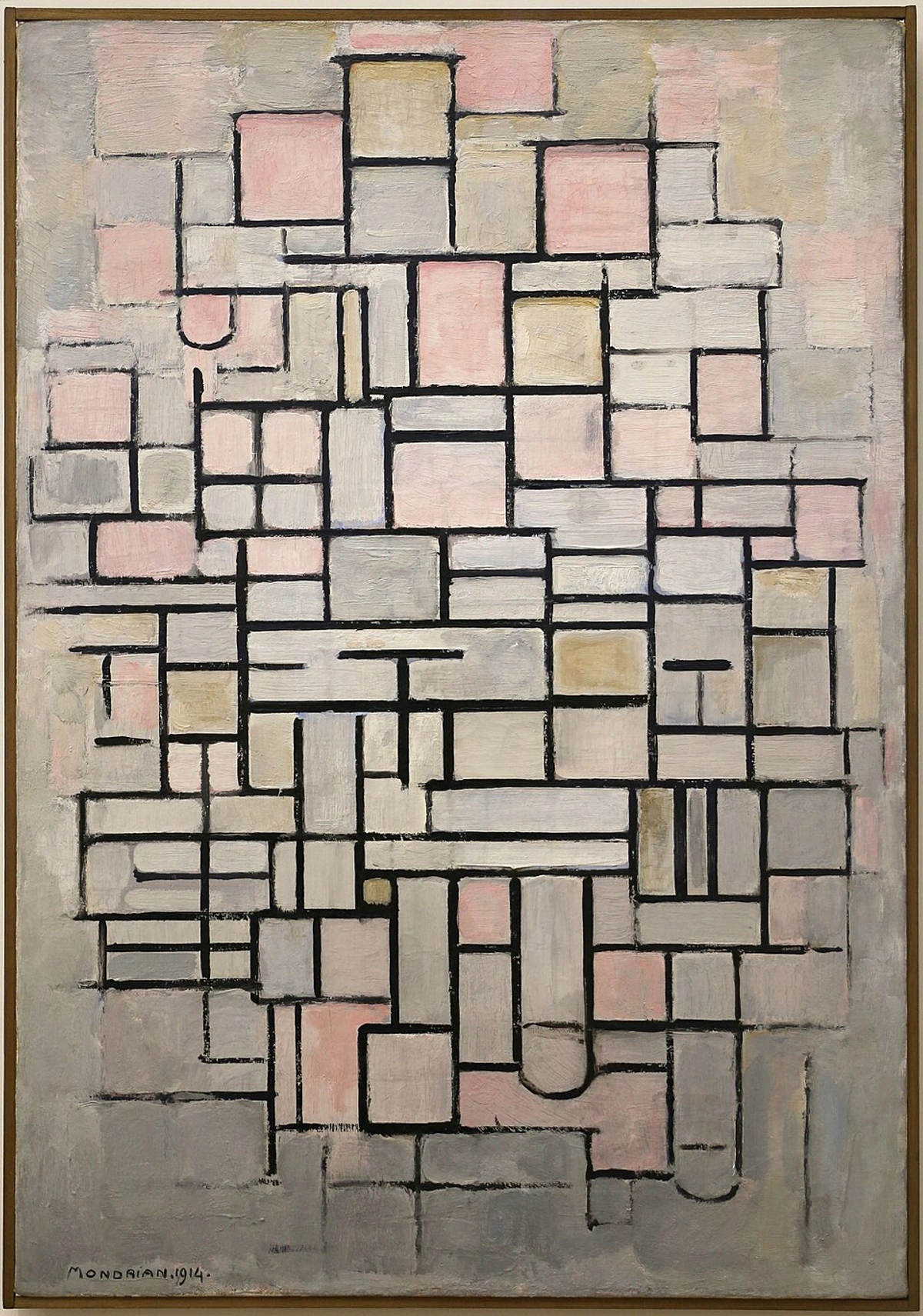

Piet Mondrian and De Stijl (c. 1917 onwards): Neoplasticism and Universal Harmony

Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, a key figure in the De Stijl movement, pushed abstraction towards universal harmony through severely simplified geometric forms. This specific style was known as Neoplasticism, a term Mondrian coined to describe his rigorous, grid-based approach. Using only primary colors (red, blue, yellow) and non-colors (black, white, gray) arranged in a precise grid of horizontal and vertical lines, Mondrian sought to reveal the underlying, universal order of the universe, a kind of utopian spiritual balance. This was not just an aesthetic principle but a philosophy aimed at creating a new, harmonious society, influencing not just painting but also architecture, furniture design, and typography. His "Composition No. IV" (1914) exemplifies this rigorous, almost architectural approach to abstraction, aiming for a balance that transcended individual emotion and offered a blueprint for a new, harmonious world. It was a rational, almost mathematical search for beauty and order, a stark contrast to the emotional outpourings of Expressionism.

Mid-20th Century: The American Ascent and Global Dialogue

World War II sent shockwaves through the art world, leading many European artists and intellectuals to flee to America, particularly New York. This seismic shift not only fostered an explosion of creativity but fundamentally changed art's global epicenter. The anxieties of the post-war era, combined with new intellectual currents, gave rise to some of the most iconic abstract movements that would define the latter half of the century. The continued evolution of abstract art after these initial European breakthroughs shows its enduring power and adaptability, constantly finding new ways to speak to the human condition.

Abstract Expressionism (c. 1940s-1960s): Emotion Unleashed and the Existential Canvas

If the early pioneers sought inner truth, Abstract Expressionists exploded with it. This was less about carefully constructed forms and more about raw emotion, spontaneity, and direct, often physical, engagement with the canvas. Deeply influenced by Surrealism's emphasis on automatism (spontaneous, automatic creation from the subconscious) and emerging from the anxieties of the post-war era, the movement broadly encompassed two main tendencies:

- Action Painting, exemplified by Jackson Pollock's energetic drip paintings like "Number 17A" (1948). These were less about painting an image and more about painting an event, a record of the artist's physical and psychological struggle. It was an existential act, a direct expression of the subconscious mind and raw human energy, often involving gestural abstraction and a focus on the process of creation itself.

- Color Field Painting, seen in Mark Rothko's expansive canvases of luminous, stacked color rectangles that invite deep contemplation and emotional immersion. Here, color itself becomes the subject, creating an overwhelming, almost spiritual experience for the viewer, meant to evoke the sublime. It's an art form that often feels intensely personal, even spiritual. You might feel a bit silly staring at a large canvas of just colors, but then, slowly, it washes over you, creating a profound emotional resonance. It's truly a transformative experience, where the sheer presence of color transports you. Want to dive deeper? Here's an ultimate guide to Abstract Expressionism.

Minimalism (c. 1960s-1970s): Less is More, or is it a New Form of More?

After the emotional intensity and subjective chaos of Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism emerged as a cool, intellectual counterpoint. Artists like Donald Judd, Frank Stella, Agnes Martin, and Robert Ryman stripped art down to its essential elements: simple geometric forms, often industrial materials, and a focus on the object itself rather than illusion, narrative, or overt emotion. My cynical side sometimes wonders, "Is this just a fancy way of saying 'not much happened'?" But then I realize the profound statement it makes about space, form, and the viewer's direct, unmediated experience. Minimalism challenged the very definition of art, embracing "literalism" – the idea that a work is simply what it is, a physical object in space, allowing the viewer to engage purely with its presence without distraction. It’s about being present with the object, pure and unadorned, challenging the viewer to consider what truly constitutes art and our own perceptions within the space it occupies. It asks us to confront the artwork as an undeniable presence, often making us hyper-aware of the gallery space, the lighting, and our own bodies within that environment.

![]()

Post-Painterly Abstraction (c. 1960s onwards): Precision and Purity of Color

This broad category encompasses a range of artists who explicitly moved away from the gestural intensity, emotional angst, and heavy impasto of Abstract Expressionism. Instead, they opted for cleaner lines, hard-edge forms, and a focus on color itself as the primary subject, applied with a new precision and clarity. Think of Helen Frankenthaler's groundbreaking soak-stain paintings, the vibrant fields of Morris Louis with his veil series, or the crisp, often minimalist compositions of Ellsworth Kelly. Hard-edge painting, a significant sub-movement, emphasized sharp, clear boundaries between areas of color, creating a flattened, often monumental effect, while Lyrical Abstraction, another offshoot, allowed for more fluid, gestural, yet still controlled, applications of color. The emphasis was on the pure optical experience of color and form, sometimes achieving a serene, almost meditative quality, prioritizing formal elements over personal expression. For me, this is where the definitive guide to color theory in abstract art really comes into its own, as artists meticulously explored the psychological and compositional effects of color. It was a return to order and a celebration of the picture plane as a flat surface.

Op Art (c. 1960s): Playing with Perception

Coinciding with Post-Painterly Abstraction, Op Art (Optical Art) also explored the optical experience, but with a distinct focus on manipulating the viewer's eye. Artists like Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley used precise, often geometric, arrangements of lines and shapes to create illusions of movement, vibration, or hidden images. It wasn't about emotional expression or symbolic meaning, but about the purely perceptual phenomenon, challenging how our brains process visual information and often creating dazzling, dizzying effects. It's a testament to how even the most calculated, seemingly emotionless art can provoke a powerful, visceral reaction.

Contemporary Trends: A Tapestry of Evolving Expression

Abstract art didn't stop in the 70s; it kept evolving, morphing, and questioning. Today, it’s a vast, diverse landscape, often blending with other forms and technologies. It's perhaps the most exciting time to be an abstract artist, or simply a lover of abstract art, because the boundaries are constantly being redrawn. This era is a testament to the idea that abstraction is not a singular style, but a continuous method of inquiry, a dynamic and open-ended dialogue with history and the present moment.

Neo-Expressionism (c. 1970s-1980s): The Return of Rawness

Almost as a reaction to the cool detachment and intellectual rigor of Minimalism and Conceptual Art, Neo-Expressionism brought back intense subjectivity, raw brushstrokes, and sometimes figurative elements, but often in an abstracted, emotional, and deliberately 'clumsy' way. Artists like Georg Baselitz (known for his upside-down figures), Anselm Kiefer, and Jean-Michel Basquiat explored history, mythology, and personal trauma with a powerful, almost aggressive energy, often using heavy impasto and symbolic materials. It's like the art world collectively took a deep breath after Minimalism and then let out a primal scream – a raw, unfiltered outpouring of emotion and narrative, even if fragmented.

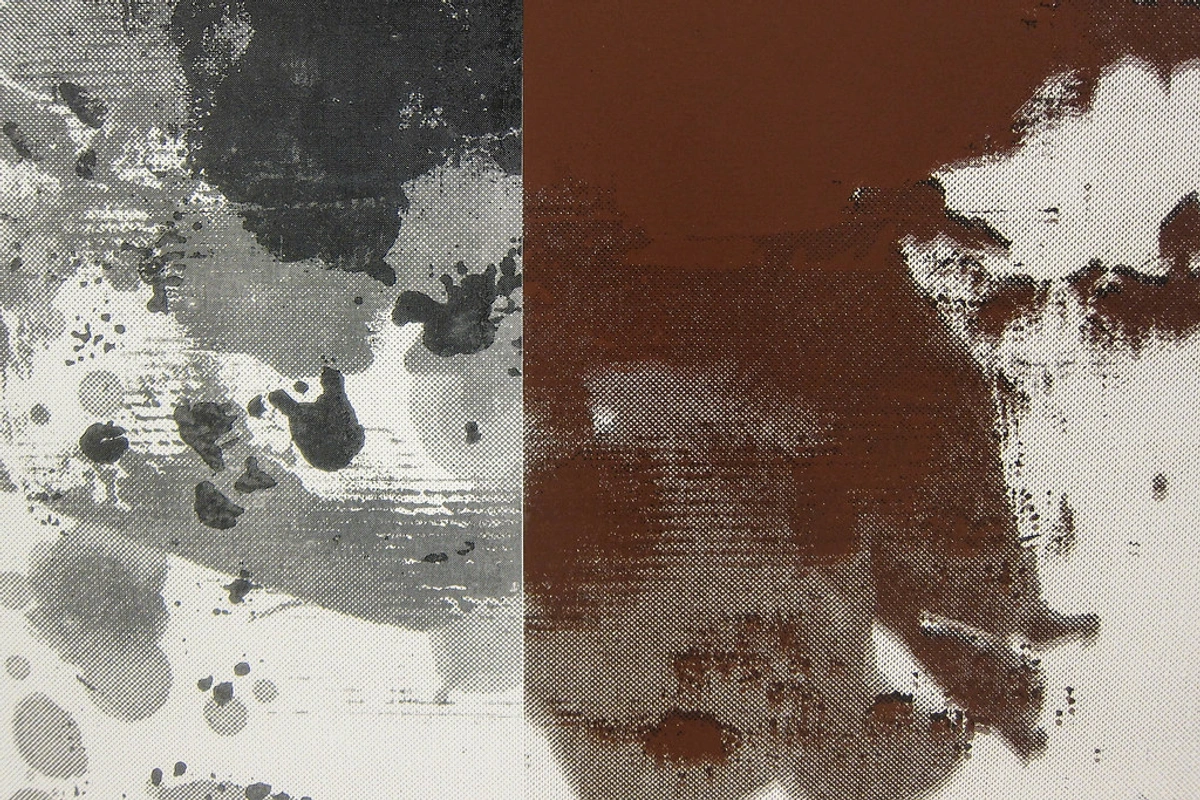

Contemporary Abstraction: No Rules, Just Evolving Expression

And then we arrive at today. Contemporary abstraction is a beautiful, messy, and exhilarating mix. Artists are free to draw upon any of the historical movements, combining elements, pushing boundaries, and creating entirely new dialogues. You see Gerhard Richter's breathtaking scraped paintings, blending chance and control (like his "Abstract Painting (726)"), or Christopher Wool's gritty, stencil-based word paintings that blur text and image. Influenced by movements like Process Art (emphasizing the act of creation, materials, and time, rather than the finished product) and Arte Povera (using 'poor' or humble, everyday materials to challenge consumerism and traditional art forms), contemporary artists often emphasize the materials and the act of creation itself, embracing imperfections and the inherent qualities of their chosen medium. They also increasingly engage with digital abstraction, using algorithms, generative art, and virtual reality to explore new visual languages and interactive experiences, pushing the boundaries of what a painting or sculpture can be. It’s art that can be minimalist, maximalist, geometric, organic, digital, analog – sometimes all at once. It's about personal vision, experimentation, and engaging with the complexities of our modern world without needing to literally depict it. It's where I, as an artist, find myself constantly inspired and challenged, always evolving my own approach, much like the broader scene in the definitive guide to contemporary art movements.

The Enduring Impact: Why Abstract Art Still Resonates (and Why You Should Care)

I often get asked, "But what does it mean?" And my answer is usually, "What do you feel?" Abstract art, perhaps more than any other form, invites participation. It's not passive viewing; it's an active engagement with color, form, texture, and the artist's intention (or lack thereof). It challenges our perception, sparks our imagination, and offers a different lens through which to view the world. Beyond aesthetic pleasure, it can also foster critical thinking and visual literacy, encouraging us to analyze, interpret, and make connections in non-literal ways. It reminds me that not everything needs to be literal to hold profound truth or beauty. Sometimes, the most honest expression is the one that bypasses explanation entirely. Abstract art has also historically challenged societal norms and conventions, pushing boundaries not just in art but in how we perceive reality and freedom of expression. Its influence can be seen beyond canvases, permeating modern design, architecture, fashion, and even inspiring musical compositions, demonstrating its pervasive cultural reach. If you're looking for art that resonates with your own inner landscape, that challenges you to feel and think differently, you might just find it in the abstract. You can explore some of my own creations right over at the art for sale section.

Frequently Asked Questions about Abstract Art Movements

Q: What was the first abstract art movement?

A: While movements like Cubism and Futurism contained strong abstract elements and were crucial precursors, Wassily Kandinsky is widely credited with creating the first purely abstract paintings around 1910. His work, often associated with broader Expressionism, focused on expressing inner spiritual realities through non-representational forms, laying the groundwork for later pure abstraction movements like Suprematism and De Stijl. For a more complete overview, don't miss the article on the evolution of abstract art.

Q: What's the difference between abstract art and non-objective art?

A: This is a great question often debated! Abstract art generally refers to art that derives from real objects or forms but is distorted, simplified, or fragmented from them. You might still be able to glimpse the original source, however abstract it has become. Think of early Cubism. Non-objective art (also called non-representational art), on the other hand, makes no reference to the natural world or physical reality. It is purely about form, color, line, and texture, with no recognizable subject matter. Kandinsky's later "Compositions" and Malevich's "Black Square" are prime examples of non-objective art. It's a subtle but important distinction, much like the difference between a poem inspired by a landscape versus one purely about the sound of words.

Q: Is contemporary abstract art still relevant?

A: Absolutely! Contemporary abstract art continues to be a vibrant and crucial part of the art world. It evolves with new technologies, materials, and cultural contexts, offering fresh perspectives on human experience and challenging our understanding of art itself. Artists like Gerhard Richter and Christopher Wool continue to push boundaries and find new ways to engage viewers. Its relevance lies in its ability to reflect and question our increasingly complex, non-literal world. It serves as a visual language for the unseen forces and fragmented realities of modern life.

Q: How can I start appreciating abstract art?

A: My best advice? Approach it with an open mind and don't try to 'figure it out' like a puzzle. Let the colors, shapes, and textures affect you emotionally. Research the artists and their intentions, and also consider their process, materials, or even the scale of the work as potential entry points for understanding. But most importantly, trust your own feelings. Over time, you'll develop your own language for understanding and appreciating it. And remember, it's okay if you don't 'get' every piece – art is a personal journey. Perhaps a visit to a museum, like my own Zen Museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, could be a great start for immersive appreciation!

Q: Are there common themes across abstract art movements?

A: While styles vary wildly, common threads often include a rejection of traditional representation, an emphasis on pure visual elements (color, line, form), a focus on emotional or spiritual expression, and an exploration of the artist's inner world. It's a continuous quest for new visual languages, often challenging what art is and can be, and continually seeking to communicate something beyond the purely tangible.

Q: How did abstract art influence other art forms (e.g., design, architecture, music)?

A: Abstract art's influence is far-reaching! Its principles of geometric simplification, color theory, and emphasis on form over function profoundly impacted modern architecture (think Bauhaus, De Stijl's architectural influence), graphic design (typographic experiments, logo design), and industrial design. In music, it inspired composers to explore atonality and experimental structures, moving beyond traditional harmony, much as abstract painters moved beyond traditional representation. It's about breaking down and rebuilding, finding new systems of order and expression.

Q: What are some common criticisms of abstract art and how can they be addressed?

A: Common criticisms often include: "My kid could do that," "It has no meaning," or "It's just random." These often stem from an expectation of literal representation. They can be addressed by understanding the historical context and the artist's intentions – abstract art wasn't arbitrary; it was often a deliberate, intellectual, or spiritual quest. Emphasize the skill in composition, color theory, and material handling, as well as the deep philosophical shifts it reflects. Ultimately, it invites subjective experience, rather than dictating a singular meaning, encouraging viewers to engage their own emotions and interpretations.

Q: Are there specific abstract art techniques I can try at home?

A: Absolutely! Many abstract techniques are accessible for beginners. You could try gestural painting (allowing your hand to move freely, focusing on emotion), color field studies (experimenting with large areas of color and their interactions), collage (combining different textures and images abstractly), or even automatic drawing (drawing without conscious thought, inspired by Surrealism). The key is to let go of the need for perfection and embrace experimentation. It's a wonderful way to connect with your own creative process: from concept to canvas in abstract art and see what emerges!

Key Abstract Art Movements at a Glance

Movement | Key Characteristics | Core Focus | Key Concepts/Philosophy | Key Artists |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubism (c. 1907) | Fragmented objects, multiple viewpoints, geometric forms. | Deconstructing reality, conceptual understanding of objects. | Analytical approach, simultaneity, multiple perspectives, redefinition of pictorial space, influence of Cézanne. | Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque |

| Futurism (c. 1909) | Speed, motion, technology, lines of force, simultaneity. | Capturing the dynamism of modern life. | Movement, machine age, destruction of the past, portrayal of time and space, kinetic energy. | Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla |

| Orphism (c. 1910) | Lyrical abstraction, vibrant colors, overlapping geometric shapes, musicality. | Pure color and light to evoke emotion and movement. | Color as subject, emotional resonance, rhythm, harmony through color relationships, synesthesia. | Robert Delaunay |

| Expressionism (c. 1910) | Inner necessity, spiritual states, liberation of color/form from description. | Expressing profound internal experiences and emotions. | Inner necessity, spirituality, emotional truth, non-objectivity, influence of Theosophy. | Wassily Kandinsky |

| Suprematism (c. 1913) | Basic geometric forms (squares, circles), limited color palette. | Supremacy of pure feeling, spiritual purity through reduction. | Zero of form, non-objectivity, spiritual essence, universal visual language, cosmic void. | Kazimir Malevich |

| De Stijl (c. 1917) | Primary colors, black/white/gray, horizontal/vertical lines, grid-based. | Universal harmony, underlying order of the universe, neoplasticism. | Universal harmony, utopian vision, elemental geometry, a new social aesthetic, rational order. | Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg |

| Abstract Expressionism (c. 1940s) | Raw emotion, spontaneity (Action Painting), luminous color fields (Color Field). | Unleashing subconscious emotion, direct engagement with canvas. | Existentialism, automatism, the sublime, raw gesture, emotional immersion, process over product. | Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko |

| Minimalism (c. 1960s) | Simple geometric forms, industrial materials, focus on object itself, pure experience. | Stripping art to essentials, challenging perception, objective presence. | Literalism, objecthood, viewer's experience in space, removal of narrative/illusion, anti-subjectivity. | Donald Judd, Agnes Martin |

| Post-Painterly Abstraction (c. 1960s) | Cleaner lines, hard-edge forms, focus on color as primary subject, precision. | Optical experience of color and form, formal purity over personal expression. | Formalism, color purity, flat picture plane, serenity, hard-edge painting, lyrical abstraction. | Helen Frankenthaler, Ellsworth Kelly |

| Op Art (c. 1960s) | Precise geometric arrangements, illusion of movement/vibration. | Manipulating viewer's perception, purely perceptual phenomena. | Optical illusion, perceptual engagement, visual dynamics, retinal art. | Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley |

| Neo-Expressionism (c. 1970s) | Intense subjectivity, raw brushstrokes, emotional, sometimes abstracted figurative elements. | Exploring history, mythology, personal trauma with aggressive energy. | Return to subjectivity, historical memory, raw expression, fragmented narrative, symbolism. | Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Jean-Michel Basquiat |

| Contemporary Abstraction (c. 1980s-Present) | Blending styles, digital/analog, process-oriented, conceptual, diverse materials. | Continuous inquiry, personal vision, engaging modern complexities without literal depiction. | Experimentation, process art, digital tools, blurring boundaries, co-creation of meaning, conceptual focus. | Gerhard Richter, Christopher Wool |

My Final Thoughts: A Never-Ending Conversation

Exploring these movements feels a bit like looking through an old photo album – each era tells a different story, yet they're all connected by the thread of human creativity and an unwavering desire to push boundaries. From the analytical dissections of Cubism to the explosive emotions of Abstract Expressionism, and right up to the diverse, boundary-pushing work happening today, abstract art has continually reinvented itself. It's a testament to the idea that art isn't just about what you see, but what you feel, what you think, and what possibilities lie just beyond the familiar. It’s a language that speaks of the unseen and the felt, constantly challenging and expanding our perception of reality itself. And for me, that's a conversation I hope never ends, much like my own artistic journey of finding my voice: the evolution of my abstract artistic style. I invite you to continue this journey of discovery, perhaps even finding your own connection to abstraction within my art for sale section.