Wassily Kandinsky: The Maverick Who Taught Art to Sing (Expanded Guide)

Uncover Wassily Kandinsky's revolutionary path: from synesthesia & inner necessity to his evolving abstract styles, spiritual philosophy (Theosophy, Bauhaus), and profound legacy shaping modern art and beyond. A deep dive into why his art still sings.

Wassily Kandinsky: The Maverick Who Taught Art to Sing

You know, when I first stumbled upon Wassily Kandinsky's work, it wasn't just another artist's portfolio; it was like the static on my mental radio cleared, and a whole new frequency of understanding art resonated deeply within me. It felt like a door creaked open into a universe of possibilities I hadn't known existed. This isn't just about admiring pretty pictures; it’s about understanding a radical shift, a genuine revolution in how we perceive art. Kandinsky, alongside trailblazers like Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian, is widely recognized as one of the pioneers of abstract painting. For me, though, he was the artist who dared to ask, "What if art could sing without words, express emotion without depicting a single recognizable thing?" His daring leap from representational forms didn't just change modern art's path; it forged a new one where color, line, and shape conveyed meaning and emotion entirely independent of external reality. It was a liberation, a journey I find myself returning to again and again. In this article, we’ll explore the life and revolutionary art of Wassily Kandinsky, tracing his journey from law to abstraction and understanding why his work continues to resonate so deeply, not just with me, but hopefully, with you too.

The Path to Abstraction: When Colors Started Singing

Born in Moscow in 1866, Wassily Kandinsky initially pursued what felt like a truly formidable, almost dry, career in law and economics. Honestly, if you'd told me then that this future lawyer would become the guy who taught art to sing, I probably would have laughed! But all that rigorous intellectual groundwork actually proved incredibly useful for his later artistic theories. Sometimes, though, life has a way of subtly nudging you onto a completely different path, and for Kandinsky, a series of profound experiences irrevocably shifted his focus to art. A pivotal moment, almost an epiphany, occurred when he encountered Claude Monet's "Haystacks" in Moscow. I imagine he wasn't just impressed; he was deeply moved by how Monet explored color's independent power, detached from precise subject matter. It was as if the colors themselves held the message, not the bales of hay.

Later, even more significantly, a performance of Richard Wagner's opera Lohengrin reportedly triggered a powerful instance of synesthesia—a neurological phenomenon where the stimulation of one sensory pathway leads to automatic experiences in another. Imagine hearing music and suddenly, you're not just hearing the symphony, you're seeing it – a riot of vibrant colors and dynamic forms exploding behind your eyes, corresponding to the orchestral music. For Kandinsky, this wasn't just a fleeting moment; it was a profound realization, a vivid demonstration of how abstract forms could communicate directly to the soul. He wasn't just seeing colors; he was experiencing a direct emotional and spiritual resonance, where specific notes and harmonies translated into dynamic visual compositions – a true blueprint for his future abstract language. These formative experiences weren't just fleeting moments of inspiration; they laid the groundwork for a profound connection Kandinsky perceived between sensory experience and spiritual resonance, which became the cornerstone of his entire artistic philosophy. This conviction solidified his belief that art could evoke emotions and spiritual responses directly through non-representational means, much like music. This belief became the bedrock of his revolutionary artistic philosophy, freeing art from its traditional tether to objective reality and directing it towards the expression of inner states. It was a monumental shift, a daring declaration that art could be profoundly meaningful without showing us anything recognizable. This liberation of color and form paved the way for his deep exploration into the spiritual dimensions of art, which would soon define his life's work. For a broader understanding of this pivotal shift, I highly recommend exploring the definitive guide to the history of abstract art or the ultimate guide to abstract art movements.

Zen Dageraad, licence

The Spiritual in Art: Kandinsky's Quest for the Soul

That profound connection Kandinsky perceived between sensory experience and spiritual resonance became the cornerstone of his entire artistic philosophy. He wasn't just making pretty pictures; he was on a mission. He posited that art possessed a transcendent, spiritual purpose, a mission articulated in his foundational treatise, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911). I think of this work as his "aha!" moment put into words, a deeply personal quest for meaning in a world he felt was becoming increasingly materialistic and spiritually impoverished. He was reacting to a Europe rapidly industrializing, yes, but also one where the pursuit of scientific materialism often overshadowed deeper human values, eroding traditional spiritual frameworks and leading to a sense of profound emptiness. For Kandinsky, this spiritual void was alarming; art, for him, was the antidote, a necessary bridge to re-establish humanity's connection with its deeper self and universal truths. It’s worth noting that Kandinsky's profound spiritual views were often influenced by contemporary esoteric movements, particularly Theosophy and Anthroposophy. These philosophies emphasized the spiritual evolution of humanity, the interconnectedness of all things, and a belief in hidden spiritual realities—ideas that deeply resonated with his conviction that art could reveal a deeper, non-material truth. In his book, he systematically explored the theoretical underpinnings of non-objective art, arguing for its capacity to uplift the soul.

In this book, Kandinsky argued that authentic art emanates from an inner necessity—an intrinsic, spiritual compulsion within the artist to express inner truths rather than merely replicate external appearances. Think of it as that deep, undeniable urge to create something that comes from your core, your spirit. For me, it's that feeling when an idea grabs hold, and I simply have to get it out, even if it feels messy at first. It's not about pleasing anyone else; it's about being true to that profound, intrinsic drive. An artist, he believed, recognizes this necessity as an undeniable internal pressure, a quiet yet persistent voice demanding expression, often when words fail. He viewed the prevailing materialism of his era as a spiritual impediment, and art, in his eyes, was the essential force capable of guiding humanity toward a more enlightened, spiritual future. This conviction imbued his paintings with a profound sense of purpose, reflecting creation from the soul rather than purely from visual perception. It's a challenging concept, isn't it? To trust that inner voice so completely, even when the world is screaming for something else.

Printerval.com, licence

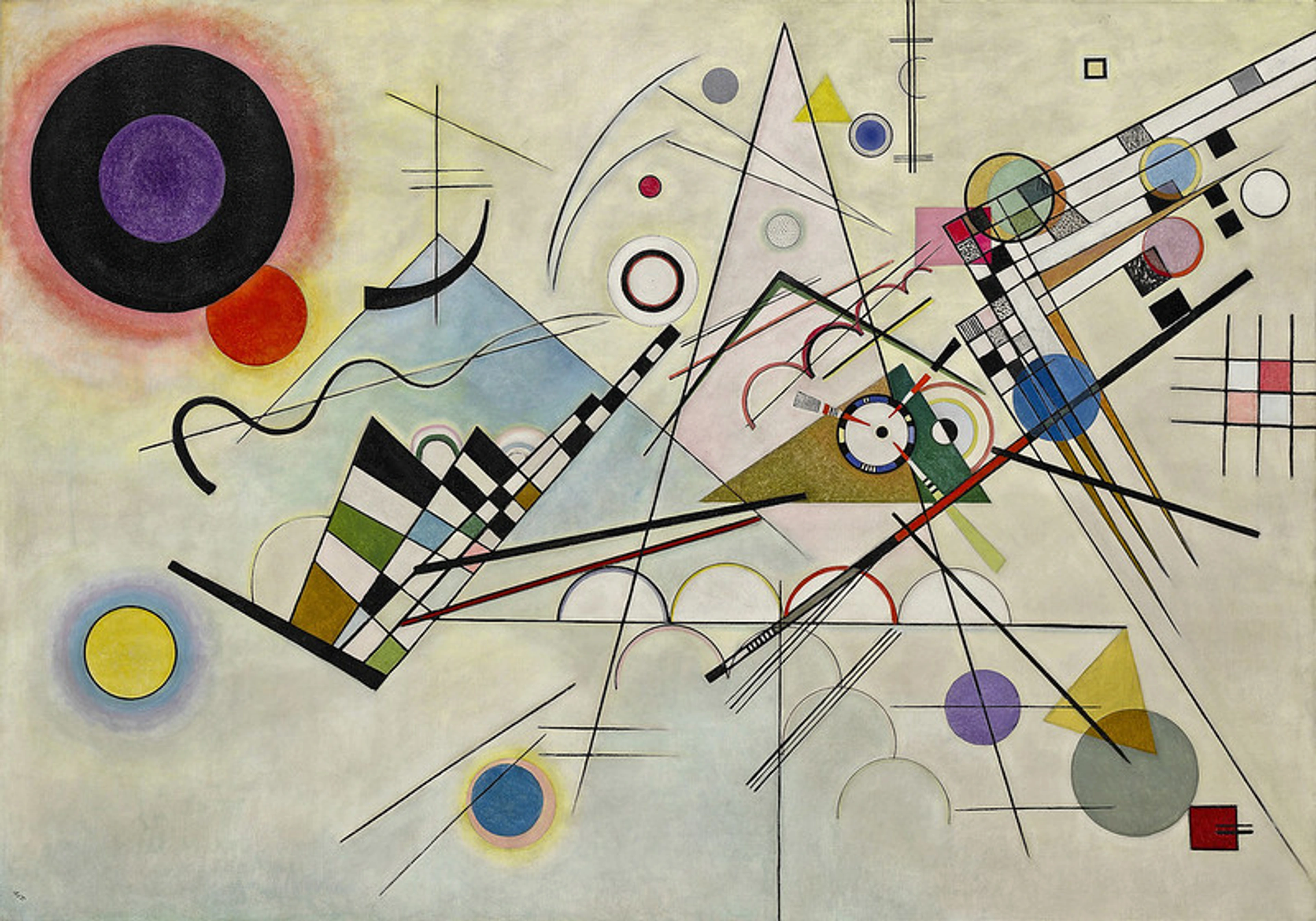

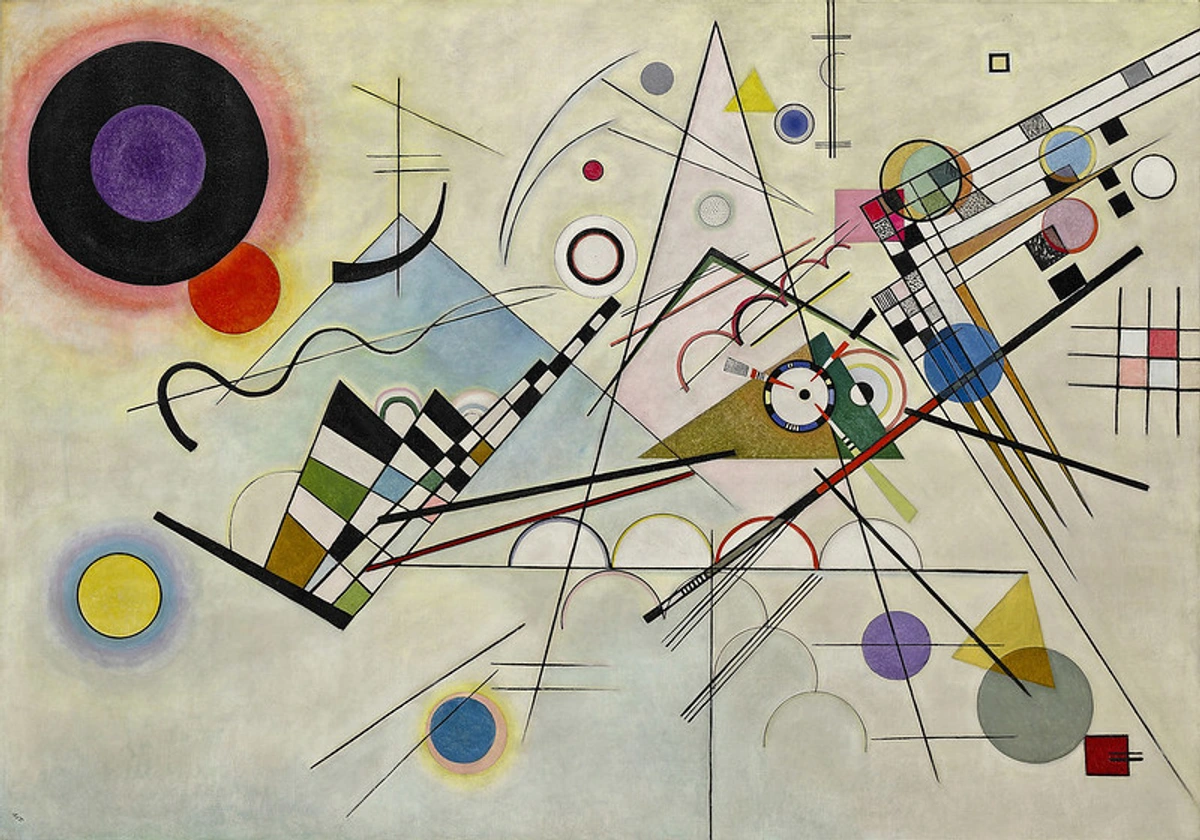

For Kandinsky, colors and forms were not arbitrary splashes or random doodles; they possessed intrinsic expressive power, functioning akin to musical notes in a symphony. He saw red, for example, not just as a color, but as a vibrant shout, a call to attention, symbolizing passion, vitality, and even danger. Blue conveyed spirituality, calm, and depth, while yellow represented earthly joy and warmth. Similarly, geometric forms like circles, triangles, and squares were not mere abstract shapes but potent symbols infused with psychological and spiritual significance. The circle, often representing the spiritual cosmos, embodied peace and perfection, while the triangle suggested dynamic aspiration. It felt like he was giving a secret language to every dot and dash, creating a universal grammar for the soul. But that was Kandinsky's genius – finding the universal in the specific. Through such deliberate choices, he constructed a visual language capable of directly impacting the viewer's emotions and spirit, mirroring his synesthetic experiences of perceiving color in music. For example, in his Compositions series, he sought to create visual symphonies, where the energetic interplay of reds and yellows might evoke the joyful clang of brass, while deep blues and flowing lines could conjure the contemplative swell of strings. This wasn't about illustrating music, but about translating its emotional power into a purely visual form. These meanings, while often consistent, were not rigidly fixed and could be influenced by their interplay within a specific composition or the artist's evolving theories. It's a dynamic language, not a static dictionary. For further exploration of these concepts, consider articles on the psychology of color in abstract art or the symbolism of geometric shapes in abstract art. How do you imagine art speaking directly to your spirit, bypassing all rational thought? This blend of precision and spiritual aspiration is something I find myself constantly striving for in my own work.

Kandinsky's Artistic Evolution: A Journey Through Abstraction's Uncharted Territory

Kandinsky's artistic trajectory wasn't a straight line; it was a dynamic exploration, characterized by distinct phases in which he progressively refined his groundbreaking visual language. Tracing this evolution is crucial to understanding the development of abstract art itself, and honestly, it’s a fascinating ride through one artist’s persistent quest for deeper meaning. It's almost like watching a musician slowly discover a whole new instrument, note by note.

Early Years (Pre-1908): Figuration with a Foreshadowing

Before his full commitment to abstraction, Kandinsky's early work, spanning approximately 1900 to 1908, displayed influences from post-Impressionist styles. He experimented with Fauvism, evident in his use of bold, non-naturalistic colors for emotional impact – almost as if he was already testing the limits of color's power. He often borrowed Fauvist techniques like broad brushstrokes and simplified forms, emphasizing pure, saturated hues over realistic depiction. He also explored elements of Expressionism, characterized by emotional distortion rather than objective reality, using jagged lines and intense contrasts to convey psychological states. While still rooted in landscape and figurative subjects, these early pieces, like Gabriele Münter Painting in Kallmünz (1908), already showcased an intense use of color and a growing disregard for conventional representation that clearly presaged his later breakthroughs. This period highlights a crucial transitional phase where the artist began to prioritize inner emotional expression over strict objective representation. He wasn't just flipping a switch; it was a slow, deliberate dance away from the familiar. Interestingly, early critics were often perplexed by this departure, finding his bold use of color and increasingly distorted forms jarring, a common challenge for pioneers. What personal breakthroughs have slowly reshaped your own path?

The Breakthrough – Lyrical Abstraction (1908-1914): Painting the Unseen

This period marks Kandinsky's pivotal breakthrough into pure abstraction, where he systematically abandoned discernible objects to achieve a purer expression of inner states. He categorized his works into three distinct series, reflecting varying degrees of external influence and internal deliberation:

Impressions: These felt like quick sketches of the soul, works with a clear reference to external reality, filtered through his subjective emotional lens – a fleeting thought captured on canvas.Improvisations: More spontaneous and unconscious expressions of inner feelings, often inspired by specific events or spiritual states, showing less direct ties to objective reality – I imagine these as spontaneous jam sessions on canvas, pure creative flow. Improvisation 28 (1912) is a fantastic example, a swirling vortex of color and line that feels like raw emotion.Compositions: His most ambitious and meticulously planned large-scale works, where emotional and spiritual content was carefully structured, representing the culmination of his theories – these were his meticulously crafted visual symphonies, where every element played its part. Imagine a "Composition" not just as a painting, but as a carefully orchestrated emotional journey, using color as a conductor and shapes as the instruments, guiding your spirit through vibrant highs and contemplative lows. Composition VII (1913) is often considered a magnum opus from this period, a dense, apocalyptic vision of swirling forms and intense colors.

This progression demonstrates Kandinsky's commitment to art stemming from inner necessity, ranging from immediate sensation to profoundly considered structures. During this era of radical artistic innovation, he co-founded the influential Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) almanac and movement with Franz Marc. The name itself, "The Blue Rider," held deep symbolic meaning for both artists: blue represented spirituality and the masculine principle, while the horse symbolized dynamic movement and breaking free from convention. Together, the blue rider embodied their spiritual quest to liberate art from material constraints and express profound inner truths through symbolism and color.

Zen Dageraad, licence

The Russian Interlude & Artistic Crossroads (1914-1921)

The outbreak of World War I prompted Kandinsky's return to Russia in 1914. During the subsequent years of war and the Russian Revolution, he engaged deeply with the burgeoning avant-garde movements, contributing significantly to art education reforms and holding prominent positions in cultural institutions. He was, in a way, trying to shape the future of art in a newly formed society, collaborating with figures from Suprematism and Constructivism like Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin. However, the increasingly rigid ideological demands of the new Soviet art, particularly the emphasis on Socialist Realism and Constructivism – movements that prioritized art for practical, societal purposes, glorifying labor and revolution – ultimately proved incompatible with his spiritual and expressive philosophy. Socialist Realism, championed by official decrees, demanded art serve the state by depicting idealized communist values and everyday life realistically, often in a heroic, propagandistic style. Meanwhile, Constructivism, while abstract, focused on utilitarian art for industrial design and mass production, seeing art as a tool for social engineering. Both clashed fundamentally with Kandinsky's belief in art as a vehicle for individual spiritual expression, untethered from external reality or political agenda. For him, art was about inner liberation, not state indoctrination. It was a stark clash of ideals: art for the soul versus art for the state. This intellectual and artistic friction led him to seek new artistic freedoms abroad, a deliberate decision to find an environment more conducive to his non-objective vision, a decision that would profoundly impact his next phase. Have you ever had to leave something familiar behind to protect your core beliefs?

The Bauhaus Years and Geometric Abstraction (1921-1933): Structure and Soul

Following his Russian interlude, Kandinsky accepted an invitation to join the faculty of the Bauhaus, the visionary German art school renowned for its innovative integration of art, craft, and technology. This integration was groundbreaking precisely because it sought to bridge the perceived gap between fine art and functional design, aiming to create a "total work of art" (Gesamtkunstwerk) that permeated all aspects of daily life, from architecture to furniture. Kandinsky's contribution was pivotal; he taught fundamental design courses, developing his influential theories on the elements of form and color within this unique multidisciplinary environment. He believed that even functional objects could possess spiritual resonance if designed with an understanding of these intrinsic principles, contributing directly to the Bauhaus ideal of uniting art and life. Imagine Kandinsky, the spiritual explorer, now immersed in a world of precise lines and functional design – it must have been quite the creative crucible! His pedagogical approach, detailed in his treatise Point and Line to Plane (1926), systematically analyzed the expressive qualities of basic geometric shapes and primary colors, linking them to specific psychological effects. His teaching introduced foundational principles of design, exploring how elements like the point, line, and plane could be organized to create specific emotional and spiritual effects—lessons applicable not just to painting, but to architecture, furniture, and textile design, reinforcing the Bauhaus's holistic vision.

During this period, Kandinsky's artistic output underwent a notable shift towards Geometric Abstraction. His compositions became more structured, incorporating precise geometric forms—circles, triangles, and lines—often arranged with a mathematical clarity that nonetheless retained a profound emotional and spiritual resonance. This phase is characterized by a masterful synthesis of rational design principles with the expressive spontaneity of his earlier work. His painting 'Composition VIII' (1923) stands as a quintessential example, showcasing a dynamic equilibrium of precise forms and vibrant color harmonies, each element carefully positioned to create a vibrating tension and visual symphony. Another significant work, 'Yellow-Red-Blue' (1925), masterfully juxtaposes these primary colors and shapes, illustrating his theories on their innate expressive power. It's a fascinating blend, isn't it? The precision of geometry meeting the wildness of the spirit. I often think about the challenge of expressing something as fluid as emotion using such strict structures – it’s a bit like trying to write poetry with only blueprints, but he made it sing. For those interested in the broader impact of this pivotal institution, the Bauhaus movement's enduring influence on modern design and art provides comprehensive insights. This rigorous exploration of form and color deeply resonates with my own artistic journey, striving for balance between structure and intuitive expression.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/gandalfsgallery/24121659925, licence

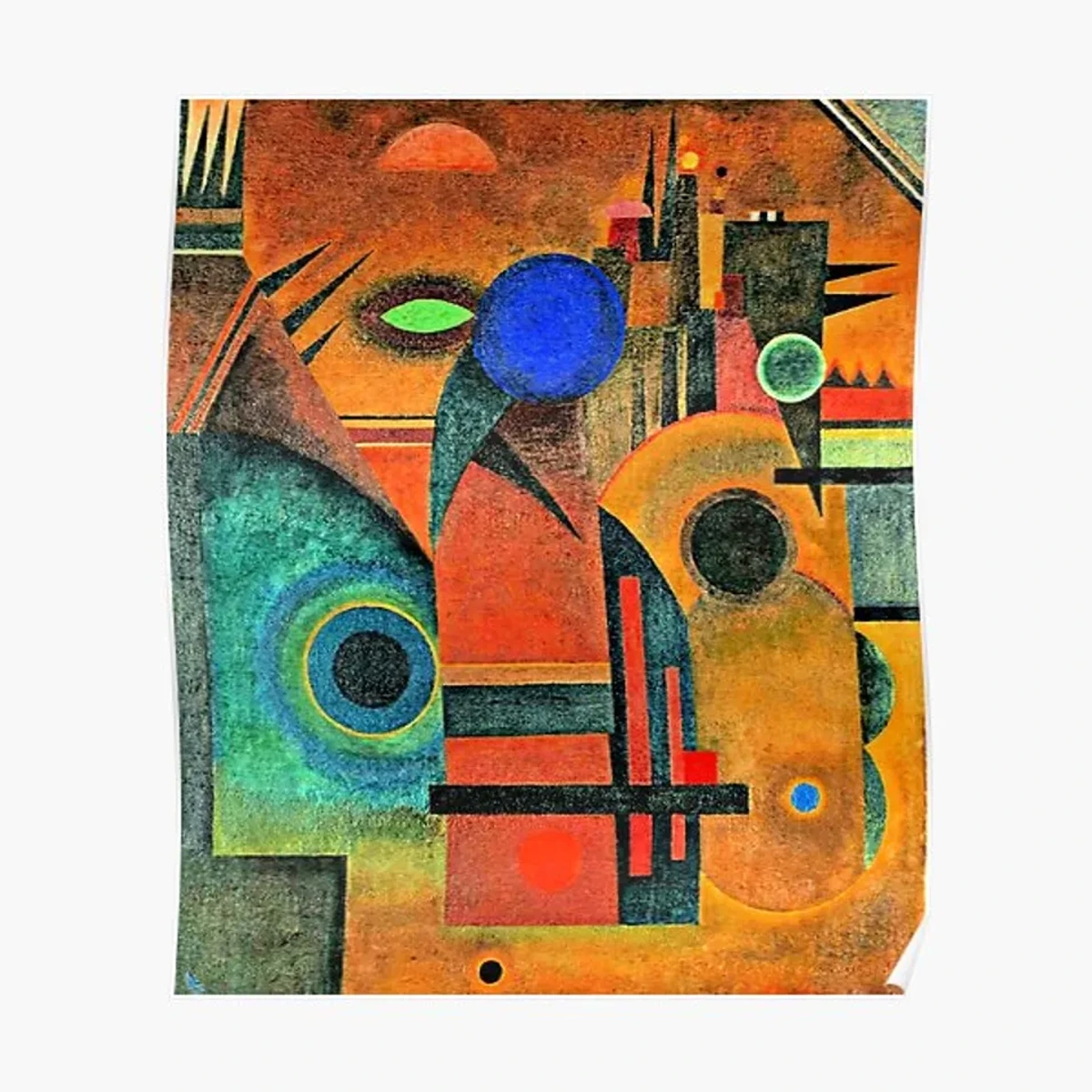

Paris Years (1933-1944): Biomorphic Echoes in a Turbulent World

In 1933, with the ominous rise of Nazism in Germany, the Bauhaus was forced to close. Kandinsky's art, along with other forms of modern expression, was shamefully condemned as "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst). The Nazis targeted abstract art and other avant-garde movements not just because they were "un-German" or "chaotic," but because they fundamentally challenged the regime's ideology of order, racial purity, and traditional, representational art that served the state. They viewed abstract art as a symptom of cultural decay and intellectual anarchy, a dangerous expression of non-conformity. It was an appalling rejection of artistic freedom, and a dark shadow fell over European art. This official denouncement led to the confiscation and destruction of many of his works from German museums and galleries, forcing him to flee to Paris. Even when the world tried to silence him, Kandinsky kept painting, kept exploring, like a stubborn seed pushing through concrete. His resilience in the face of such adversity is, to me, incredibly inspiring.

During his final Paris Years (1933-1944), Kandinsky's style continued to evolve. He began to integrate softer, biomorphic shapes—forms suggestive of living organisms, like amoebas, cellular structures, or embryonic forms—alongside his characteristic geometric elements. These organic motifs, such as undulating curves and fluid shapes, often appeared against lighter, more ethereal backgrounds, creating a dreamlike, almost playful quality. They felt softer, more ethereal, almost as if his forms were breathing. An example like 'Sky Blue' (1940) demonstrates this fusion, where whimsical, floating biomorphic entities intermingle with precise geometric lines and circles, creating a delicate dance between the organic and the ordered. Unlike the stark, structured geometry of his Bauhaus period, these biomorphic forms brought a renewed sense of fluidity and organic life to his compositions, perhaps reflecting a deeper, more introspective spiritual search in a turbulent world. This late period reflects a subtle, beautiful shift in his visual vocabulary, maintaining his spiritual quest while embracing new forms of expression until his death in 1944. How does an artist maintain their vision when the world tries to shut them down?

Zen Dageraad, licence

Kandinsky's Enduring Legacy and Contemporary Resonance: Still Teaching Art to Sing

Wassily Kandinsky's legacy is immense and multifaceted, fundamentally reshaping the trajectory of 20th-century art. His radical assertion that art could express spiritual and emotional truths independently of objective reality shattered centuries of artistic convention. He legitimized abstract art as a profound vehicle for human expression, opening doors for subsequent movements like Abstract Expressionism. The raw, gestural energy and emphasis on the artist's subjective experience in works by artists like Jackson Pollock can be directly traced to Kandinsky's pioneering focus on inner experience, automatism, and the spiritual dimension of art. Even later Color Field painting, with its focus on the immersive, emotional power of pure color, owes a profound debt to his pioneering spirit and systematic exploration of chromatic impact. Despite facing early criticism, incomprehension from the public, and ultimately political persecution, Kandinsky remained unwavering in his conviction regarding the inner necessity of art. His influential writings, such as Concerning the Spiritual in Art and Point and Line to Plane, provided a crucial theoretical framework that underpinned the development of abstract art and continue to be studied by artists, designers, and art theorists globally.

Today, Kandinsky's principles resonate deeply, influencing not only visual artists but also fields such as design, music, and even color psychology in therapeutic contexts. His exploration of how color and form directly impact human emotion laid groundwork for modern understandings of sensory perception and artistic communication. In art therapy, for instance, his ideas about the intrinsic emotional qualities of colors can guide patients in expressing feelings non-verbally, helping them articulate inner states. Furthermore, his exploration of synesthesia continues to inspire interdisciplinary collaborations between artists and musicians, pushing boundaries in performance, digital art, film, and animation. His work serves as a testament to the enduring power of an artist's vision to transcend material reality and speak directly to the soul.

And for me, well, his insistence on the "inner necessity" is a constant reminder that art isn't just about what we see, but about what we feel and what we need to express. When I look at the abstract prints and paintings we offer here, I can't help but see echoes of Kandinsky's brave new world and the liberation he championed. You can even trace my own journey through art on my artist's timeline. The profound impact of abstract works found in institutions, such as the museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, often traces its lineage back to Kandinsky's revolutionary insights. Even today, his insistence that art is not merely for visual consumption but a deep spiritual experience continues to inspire and challenge me, and I hope, you too.

Frequently Asked Questions about Wassily Kandinsky

Curious to dive deeper into the world of Wassily Kandinsky? Here are some common questions and my take on them:

What is Kandinsky best known for?

He's the guy who basically said, "Hey, what if we didn't have to paint what we see?" and then showed us how incredibly powerful that could be. Kandinsky is best known as one of the pioneers of abstract art. He is widely credited with painting some of the very first purely abstract works, believing that art could express spiritual truths and emotions through color and form alone, without depicting recognizable objects. He also co-founded the influential Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) movement and wrote extensively on his theories, most famously in Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which became a foundational text for non-objective artistic expression.

Why is Kandinsky so important in art history?

For me, he's important because he gave us permission to explore the inner landscape, to trust our gut feelings and translate them into something visually stunning. His importance lies in his revolutionary departure from representational art. He not only created groundbreaking abstract works but also provided a robust theoretical framework that demonstrated art's potential to be purely non-objective. His pivotal shift moved art's focus from external representation to internal experience, fundamentally altering the course of modern art and inspiring generations of artists to explore the inner world through abstract forms.

What were Kandinsky's main artistic periods?

Kandinsky's artistic journey can generally be divided into a few key periods:

- Early Period (pre-1908): Influenced by Impressionism, Fauvism, and Expressionism, still featuring discernible subjects but with bold, expressive color – when he was finding his feet.

- Lyrical Abstraction (1908-1914): His breakthrough into pure abstraction, characterized by fluid forms and vibrant colors, seen in his

Impressions,Improvisations, andCompositionsseries – when he really started to let loose! - Russian Interlude (1914-1921): A period of engagement with Soviet avant-garde and art education reforms, eventually clashing with ideological demands. He worked to shape art in a new society, but ultimately found the focus on utilitarian art incompatible with his spiritual vision.

- Geometric Abstraction (1921-1933): During his time at the Bauhaus, his forms became more structured, incorporating precise geometric shapes like circles, triangles, and lines – when he got a bit more structured, but still with that soulfulness.

- Late Period / Paris Years (1933-1944): Fleeing Nazi Germany, he settled in Paris, where his work featured softer colors and biomorphic (organic, amoeba-like) shapes alongside his geometric elements – a beautiful, resilient final evolution.

What is "inner necessity" in Kandinsky's philosophy?

Think of it as that deep, undeniable urge to create something that comes from your core, your spirit. It's not about pleasing anyone else; it's about being true to yourself. For Kandinsky, "inner necessity" was the driving force behind true art. It is the artist's innate, spiritual urge to express their internal life, emotions, and connection to universal truths through their work, rather than depicting external reality. This profound, intrinsic drive dictates the choice of colors, forms, and composition, ensuring the art resonates spiritually with the viewer. It is about creating from the soul, from an authentic, internal compulsion, not merely from what the eye sees or what is fashionable.

Did Kandinsky paint music?

Well, no, not literally with musical notes, but he sure tried to make his paintings sing! He wanted them to hit you in the soul the way a powerful piece of music does. While he did not literally paint musical notes, Kandinsky strongly believed that painting could evoke feelings and spiritual experiences analogous to music. He often spoke of colors and forms having musical qualities—a "visual symphony." His Compositions series, in particular, aimed to be visual equivalents of musical structures and emotional impact, translating music's emotional power into a purely visual form. His aim was to create art that bypassed intellectual understanding and directly affected the viewer's emotions and spirit, much like a profound piece of music does. This concept was deeply rooted in his personal experience of synesthesia, where he perceived colors and shapes when listening to music.

How did Kandinsky approach the creation of abstract art?

It's a common question, and I imagine many artists wonder about the journey from idea to abstract canvas. Kandinsky's process wasn't arbitrary; it was a deeply intuitive yet theoretically informed exploration, almost like a carefully guided improvisation. He began not by observing the external world, but by tuning into his inner necessity—a spiritual impulse or emotion he felt compelled to express. This inner feeling would then guide his selection of colors and forms. He believed each color and shape had its own spiritual vibration and psychological effect, much like notes in a musical scale. He would then arrange these elements, often through an iterative process of sketching and refining, not to depict a recognizable scene, but to create a harmonious or dissonant "visual symphony" that directly spoke to the viewer's soul, aiming for a composition that was both emotionally potent and spiritually resonant. It was a conscious construction of an inner world, made visible.

What do colors and shapes mean in Kandinsky's abstract art?

He was like a poet, but instead of words, he used colors and shapes to paint feelings and ideas. It's not a rigid dictionary, but more of a feeling, a resonance, and often dependent on the context within a composition. For Kandinsky, colors and shapes constituted a profound language, each imbued with spiritual and psychological meaning. He did not use them randomly. For example:

- Blue: Often represented spirituality, peace, and the infinite, drawing the viewer inward.

- Yellow: Associated with earthly joy, warmth, and sometimes aggression.

- Red: Symbolized passion, vitality, and often dangerous energy.

- Green: Indicated calm, but a more earthly, passive calm than blue.

- Circle: Seen as the most perfect and peaceful form, representing the spiritual cosmos.

- Triangle: Dynamic and aggressive, pointing upwards to spiritual aspiration.

- Square: Embodied solidity and material existence.

These meanings, however, were not entirely rigid; their interplay and context within a composition were crucial to their emotional impact, much like different notes combine to form a chord, and his understanding evolved over time. It's a living language, not a static rulebook.

How are Kandinsky's theories relevant today in fields beyond fine art?

It's fascinating how his ideas about color and form still pop up everywhere, from how we design websites to how we think about healing. It just goes to show how deeply connected art is to everything. Kandinsky's pioneering theories on the intrinsic power of color and form extend far beyond the canvas, influencing diverse contemporary fields. In design, his systematic approach to geometric elements and color psychology informs principles of visual communication and user experience. Art therapy often draws upon his concepts of color's emotional resonance and symbolic meaning to facilitate expression and healing; for instance, encouraging the use of blue to evoke calm or red for energy. Furthermore, his exploration of synesthesia continues to inspire interdisciplinary collaborations between artists and musicians, pushing boundaries in performance, digital art, film, and animation. His emphasis on art's spiritual dimension encourages a holistic view of creativity, impacting discussions in well-being and contemplative practices.