Frida Kahlo's Unfiltered World: Art, Pain, Politics & Enduring Legacy

Dive into Frida Kahlo's raw art, chronic pain, and fierce Mexicanidad. Explore iconic works, her political fire, feminist impact, and why her unfiltered legacy still inspires today. A personal journey.

Frida Kahlo: My Unfiltered Journey into Her World, Art, and Enduring Legacy

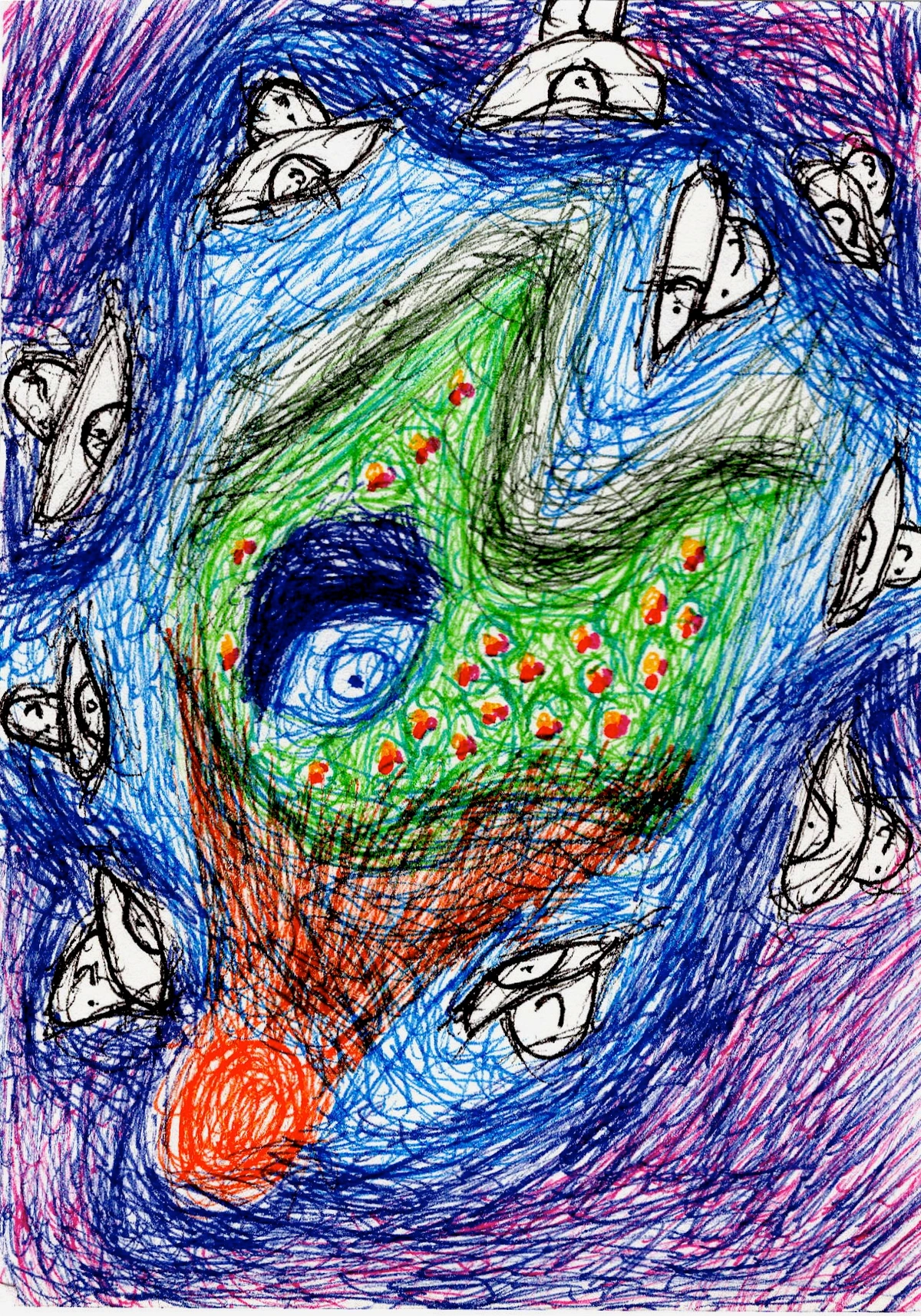

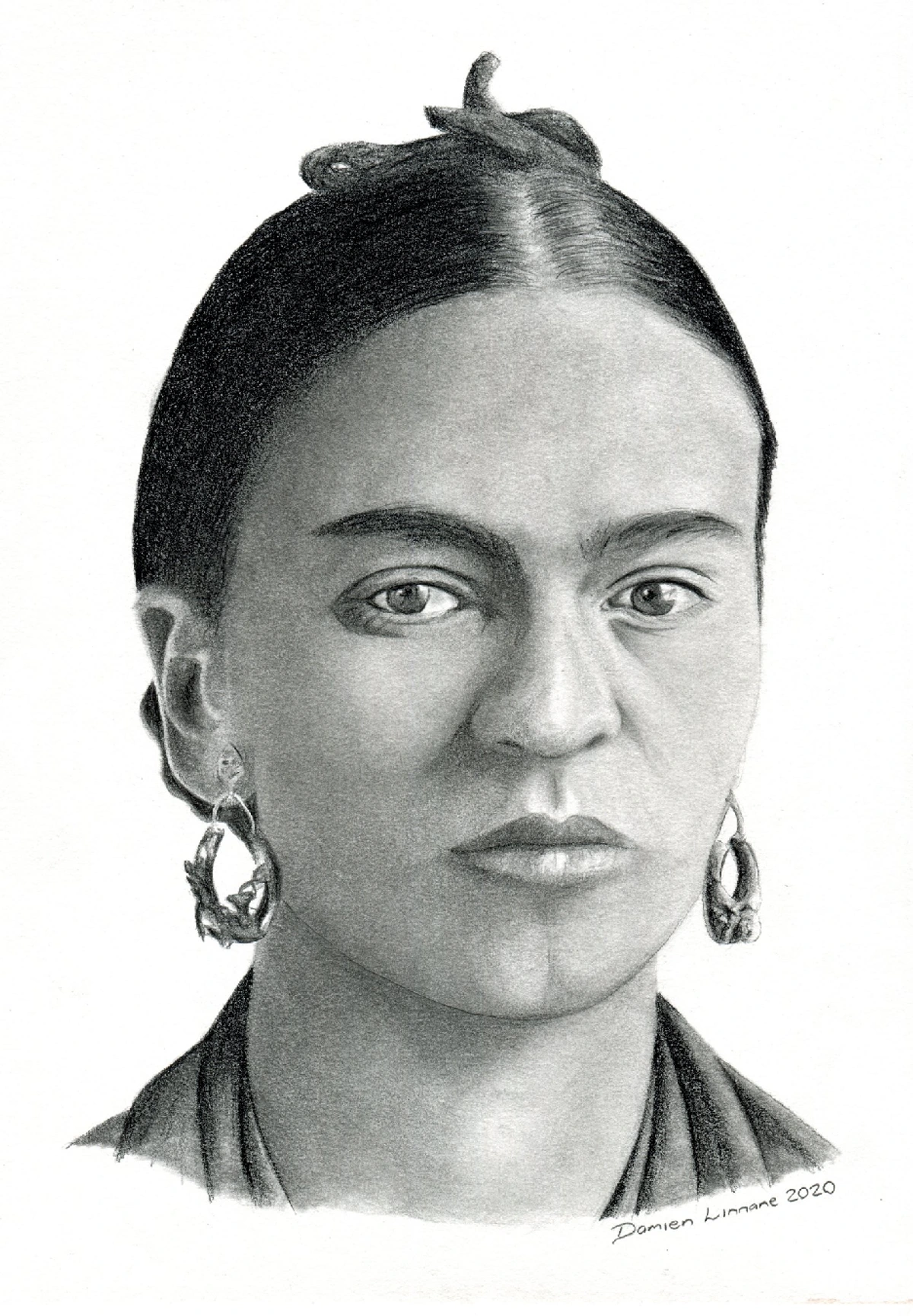

I’m going to be honest with you: for the longest time, Frida Kahlo was just that artist with the intense stare and the famous monobrow, emblazoned on tote bags and coffee mugs. My bad, I know. But then I actually dove into her world, and let me tell you, it was like finding an entire universe packed into a vibrant, painful, and utterly compelling teacup. Her story and her art are not just famous; they are raw, unapologetic, and often uncomfortable – which, funnily enough, is exactly why I adore her. Through her extraordinary life, unique artistic style, and potent cultural force, we'll explore why Frida's art continues to inspire, even resonating with how much of my own abstract work seeks to express an equally raw, unfiltered reality. Together, we'll journey through her extraordinary life, dissect her unique artistic style, and reflect on why she remains such a potent cultural force today.

More Than Just a Monobrow: The Woman Behind the Brush

Early Life and Formative Years

Frida Kahlo’s journey began in Coyoacán, Mexico City, in 1907, an environment steeped in Mexico’s rich cultural tapestry. Growing up in the midst of the Mexican Revolution and its aftermath, her family's life, like many, was profoundly impacted by the upheaval. This environment, combined with her parents' differing heritage, exposed her early to the complexities of identity and politics, further solidifying her fierce embrace of Mexicanidad. Born to a German father, Guillermo Kahlo, and a mestiza mother, Matilde Calderón y González, Frida navigated a complex heritage that profoundly shaped her identity. Growing up with this mixed European and indigenous heritage in post-revolutionary Mexico meant she inhabited a unique cultural space, often dealing with conflicting societal expectations that ultimately fueled her fierce embrace of Mexicanidad. Her father, a photographer, encouraged her artistic leanings, while her mother instilled a deep connection to Mexican traditions. I can only imagine what it must have been like to grow up surrounded by such vibrant history in their home, the Casa Azul (Blue House) – filled with traditional Mexican art, pre-Columbian artifacts, and the echoes of a burgeoning national identity. This early exposure deeply ingrained a fierce pride in her Mexican roots, which would later explode onto her canvases, making her a powerful symbol of this concept.

Mexicanidad, more than just Mexican identity, embodied a post-revolutionary embrace of indigenous heritage, traditional folk art, and a rejection of European cultural dominance – a deliberate political and cultural statement against European colonial influence, making Frida's fervent embrace of it even more significant. Frida fiercely championed this, often incorporating elements like pre-Columbian deities such as Xolotl (a dog-like god), fertility symbols from ancient ceramic figures, and even traditional patterns from indigenous textiles directly into her works. But she also drew inspiration from retablo and ex-voto paintings, small devotional works portraying miracles, infusing her personal pain with universal narratives in a deeply Mexican visual language, an artistic tradition I find incredibly powerful in its directness and emotional honesty.

A Life of Pain and Resilience

Her life, if we’re being blunt, was brutal. I mean, first, she contracts polio as a child, leaving her with a lifelong limp. Then, as a teenager, she’s in a horrific bus accident that leaves her with debilitating injuries, including a broken spinal column, pelvis, and more. My own minor struggles, like convincing myself a papercut was a fatal injury, truly pale in comparison. This woman was literally rebuilding herself, piece by piece, often in excruciating chronic back pain, nerve pain, and enduring dozens of surgeries throughout her life, including multiple spinal fusions and prolonged periods encased in plaster and steel corsets. The psychological toll of constant pain and recovery is hard to fathom, leading to profound introspection that would directly fuel her art, and the thought of such relentless physical torment just stops me in my tracks.

Yet, with an almost defiant spirit, Frida transmuted her personal anguish, both physical and emotional, into universal statements on vulnerability and strength. She often depicted her fragmented body or isolated self as a direct visual metaphor for her inner world, forcing us to confront discomfort. Her sheer resilience is something I constantly think about when I face my own struggles, big or small; it's a testament to the transformative power of art in the face of suffering.

The Tumultuous Love with Diego Rivera

And then there was Diego Rivera. Oh, that relationship! Talk about a rollercoaster of epic proportions. My own relationships have their fair share of ups and downs, but hers? Honestly, if my text message history was as dramatic as their marriage, I'd probably just throw my phone into the ocean. It was a seismic event, a storm of passion, infidelity, and undeniable connection. He was her “fat toad,” her great love, and her deepest wound. Their relationship, marked by two marriages and countless affairs, was a deeply emotional landscape that profoundly influenced her art, often spilling onto the canvas like an open wound.

Beyond the personal drama, their relationship unfolded in the public eye, a tumultuous spectacle of two colossal figures in the Mexican art scene. Their shared communist ideology and deep commitment to Mexican culture meant their personal and political lives were inextricably intertwined. Diego, an established muralist, encouraged Frida's painting, recognizing her unique talent and bold approach to self-expression, while Frida, in turn, inspired his own dedication to indigenous Mexican forms and challenged some of his more conventional artistic views. Their lives and art were inextricably intertwined, reflecting and fueling each other in ways that are still fascinating to dissect. It’s a testament to how our biggest heartbreaks and most complicated loves can fuel our greatest creations.

Political Firebrand and Cultural Icon

She wasn’t just about personal drama, though. Frida was a political firecracker, always advocating fiercely for Mexico, for communism, for indigenous rights. She believed art had a profound role in social justice, actively participating in the post-revolutionary Mexican cultural renaissance. Her communist beliefs weren't just theoretical; she was a fervent supporter of workers' rights, a staunch opponent of fascism, and a champion of the dignity of Mexico's indigenous population. She actively participated in public demonstrations and cultural programs, viewing art as a tool for social change. This commitment was palpable in her own image – she often wore traditional Mexican Tehuana dresses – and in her art, where she incorporated indigenous motifs and explicitly fused personal suffering with political convictions. For example, she opened her home, Casa Azul, to political exiles like Leon Trotsky, and it became a vibrant hub for intellectuals, artists like Isamu Noguchi, and political figures of the era, hosting passionate discussions and creative collaborations. This positioned Casa Azul not just as a home, but as a crucial political and artistic sanctuary during a time of global unrest. Works such as Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick show her personal anguish literally healing under the banner of a new political ideology. It reminds me that art isn’t just about creating pretty pictures; it can be a catalyst for social change, a powerful voice for the voiceless, a shout in a silent room. Her unwavering conviction that art must serve a higher purpose, that it's a tool for liberation and self-discovery, deeply resonates with my own belief in the transformative power of creative expression. She used her platform, her brush, and her very being to speak truth to power, and that’s something I deeply admire, constantly inspiring my own explorations into art’s capacity to convey deeper truths.

Painting Her Pain, Claiming Her Power: Frida’s Artistic Style

Having explored the fierce spirit that defined her life, I think it's time we dive into how that spirit manifested itself on canvas. Frida Kahlo's artistic style is as distinctive and unforgettable as her life story. It's a bold, often unsettling, fusion of personal narrative, Mexican folk art, and raw psychological depth. While many elements of her work might appear fantastical, her primary aim was always to depict her lived experience with unflinching honesty. Beyond the obvious influences of Mexican folk art and her pre-Columbian artifact collection, scholars also note subtle nods to European Renaissance portraiture in her formal compositions, particularly her direct, unwavering gaze in self-portraits, echoing classical frontal portraits. She masterfully adopted these formal elements to lend a monumental quality to her deeply personal narratives, grounding her emotional intensity in established artistic traditions. Her stark realism also shows an awareness of early photography, demonstrating a broader artistic awareness. I also find her use of color fascinating; she often employed a vibrant, almost audacious palette of deep cerulean blues, cochineal reds, and earthy ochres, colors deeply rooted in traditional Mexican folk art, to evoke intense emotional states rather than simply rendering reality. Red, for instance, often symbolized life, blood, or passion, while specific shades of blue could convey melancholy or a divine connection. Her command of color was intuitive yet deliberate, evolving to serve the emotional rather than literal truth of her subjects. Let's break down the key elements that make her canvases so instantly recognizable and profoundly impactful:

- Unflinching Self-Portraits: Over a third of her works are self-portraits, making her oeuvre a profound visual diary.

- Rich Symbolism: Her canvases are packed with deeply personal and cultural symbols, from animals and plants to medical imagery and pre-Columbian artifacts.

- Intense Emotional Honesty: She depicted pain, love, loss, and identity with an unparalleled directness, often blurring the lines between physical and emotional suffering.

- Mexicanidad: A proud celebration of Mexican culture, history, and indigenous heritage, seen in her vibrant colors, traditional dress, and mythological references.

A Brush with Reality (and Surrealism)

It's common for art critics and historians to lump Frida in with the Surrealists. Her use of fantastical and symbolic elements certainly explains why many still draw parallels with the movement, which aimed to unlock the unconscious mind through dreamlike imagery. However, Frida famously rejected that label, stating, “I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.” And honestly, I get it. I mean, have you ever had one of those days where reality feels so bizarre, you wonder if you're just dreaming? When I’m trying to capture an emotion or an experience on canvas, it doesn’t feel like some far-off dream; it feels very, very real, even if the final abstract result might appear dreamlike. Her reality was so vivid, it often bordered on the surreal, naturally leading her to self-portraits as a means to process and document her intense inner world. While her work shares a visual vocabulary with Surrealism, her fundamental intent—to document her intensely personal truth rather than explore theoretical dreamscapes—sets her apart. She was, in essence, her own movement. If you're curious, you can dive deeper into the ultimate guide to surrealism and compare.

The Self-Portrait as a Diary

She painted herself, constantly. I mean, who else can you truly rely on to sit still for hours, right? But it wasn't vanity; it was an act of profound introspection, a way to process unimaginable pain, to document her shifting identity, to grapple with her relationships. It’s like her entire body of work is one giant, beautiful, painful visual diary. This really resonates with me as an artist, as someone who often uses art to explore their own inner world and complex feelings. My own canvas often becomes a space for that quiet reflection. Like Frida, I find that looking inward, even at the messiest parts, can be the most authentic source of artistic expression, a way to map the contours of one's soul. Her self-portraits are invitations into her soul, offering an unflinching gaze at her inner turmoil and outer resilience, often serving as a vivid catalog of her inner landscape and symbolic language.

Symbolism and Storytelling

Frida’s canvases teem with a rich tapestry of personal and cultural symbols. Animals like monkeys (often representing her 'children' or sometimes Diego's mischievous nature), parrots (symbolizing communication or her beloved pets, but also a connection to nature), and Xoloitzcuintli dogs (linking to pre-Columbian mythology and companionship) often appear; a monkey might signify a 'child' or Diego's mischievous side, while a parrot could represent communication or a beloved pet, and the ancient Xoloitzcuintli often linked to pre-Columbian mythology and companionship, sometimes even embodying protection or fertility. These, along with pre-Columbian artifacts, medical imagery, indigenous costumes, vibrant flora, and even her tears, form a complex visual language. Each symbol was deeply personal yet steeped in Mexican culture, creating layers of meaning that invite continuous deciphering. It makes me think about how deeply artists use color to convey emotion, and how consistently animals in art history carry such immense cultural and personal weight. Her paintings are intricate stories, waiting to be deciphered, each symbol a word in her profoundly visual autobiography.

Iconic Works, Intimate Narratives

Let's take a closer look at some of her most compelling works, where her personal narratives become universal truths.

The Two Fridas (Las Dos Fridas, 1939)

My god, this one. The Two Fridas is like seeing your past and present self, or perhaps two conflicting parts of your soul, sitting side-by-side, their hands clasped, connected by a vein... while one bleeds profusely. This large oil on canvas (approximately 173.5 x 173 cm) immediately captured my attention. Painted in 1939, it starkly reflects the emotional pain of her impending divorce from Diego Rivera, portraying two aspects of her identity: the traditional Tehuana Frida, representing the strong, indigenous Mexican identity Diego adored (the Tehuana dress being a symbol of matriarchal power and cultural pride from Oaxaca), and the European-dressed Frida, symbolizing the more conventional, rejected self she felt after their divorce. The exposed hearts, linked by veins that run from the traditional Frida's portrait to the European Frida's severed artery, powerfully symbolize her profound emotional vulnerability and the lifeblood connection she felt to both parts of herself and to Diego, even in the pain of separation. It’s such a raw, powerful depiction of duality, of emotional pain, and of the enduring, sometimes fractured, bond to oneself, isn't it? How does this vivid portrayal of inner conflict resonate with your own experiences of self?

The Broken Column (La Columna Rota, 1944)

This one hits hard, really hard. Visually, it’s intensely impactful. You see Frida’s body, literally falling apart, held together by a medical corset, with her exposed spinal column replaced by a crumbling Ionic column. This oil on masonite painting (approximately 39.8 x 30.5 cm) is a literal and harrowing portrayal of her physical suffering following yet another spinal surgery. The Ionic column, a classical architectural symbol of idealized order, beauty, and strength, tragically crumbles within her. This stark contrast powerfully highlights the immense physical fragility she endured and critiques conventional notions of female beauty and physical integrity, shattered by her suffering. It makes you realize how much pain she endured daily, and how she transmuted that into something so profoundly beautiful and disturbing. You can read more about The Broken Column and its poignant message of endurance. What does this unflinching depiction of pain communicate to you about the limits and endurance of the human spirit?

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (Autorretrato con Collar de Espinas y Colibrí, 1940)

Another heavy hitter, this oil on canvas (approximately 62.2 x 47.6 cm) presents a stoic Frida adorned with a necklace of thorns, digging into her neck. From it hangs a dead hummingbird, a significant symbol in Mexican folklore often associated with the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli, representing fallen warriors, the sun, or battle. In Mexican tradition, hummingbirds can also symbolize love, beauty, or a spirit that has passed on, making its lifeless depiction here even more poignant, explicitly symbolizing the death of love or hope after her tumultuous separation from Rivera. She is flanked by a black cat (often a symbol of bad luck or death) and a monkey (a common symbol for Frida, sometimes representing Diego or her 'children' – her pets). It's just layers of meaning about pain, nature, sacrifice, and perhaps, her often-painful relationship with Diego. Seriously, dive into Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird sometime. It’s a masterpiece of subtle agony and powerful symbolism. How do these intertwined symbols speak to the complex interplay of love, loss, and spiritual endurance?

And honestly, we could go on and on. There's the equally poignant Diego and I, her famous and deeply personal Henry Ford Hospital piece, and even the politically charged Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick. Each painting is a chapter in her extraordinary, often tragic, but always defiant life. She was part of a vibrant generation of Mexican artists, alongside muralists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. But also contemporary female artists such as María Izquierdo, who, like Frida, often depicted Mexican identity and female experience, collectively forging a powerful national art movement and laying groundwork for future generations of artists exploring themes of identity and heritage in Mexico and beyond.

Her Enduring Legacy: Why We Still Talk About Frida

The very works we've just explored, each a fragment of her soul laid bare, directly contribute to the powerful and multifaceted legacy Frida Kahlo forged—a legacy that ensures she remains not just an artist, but an icon, plain and simple. She stands as a feminist symbol, a champion of Mexican identity, an emblem of resilience against unimaginable odds, and a pioneer in expressing personal pain and female experience on canvas. Her unapologetic portrayal of female subjectivity and bodily autonomy, groundbreaking for her era, continues to resonate deeply. She gave a voice to suffering and showed the world that vulnerability, far from being a weakness, could be an immense superpower. Her canvases are not just beautiful objects; they are teaching tools, used globally to educate on Mexican history, indigenous rights, and the complexities of human identity. Over time, her art has been interpreted through various lenses—feminist, post-colonial, queer theory—each new perspective underscoring its multifaceted relevance and enduring power.

Her influence on contemporary art, fashion, and culture is undeniable. While often overshadowed by Rivera during her lifetime, Frida did achieve significant recognition, exhibiting her work in Paris and New York, and gaining the admiration of artists like Marcel Duchamp and André Breton. Today, you see echoes of her bold self-expression everywhere, from high fashion runways, inspiring designers like Jean Paul Gaultier, Dolce & Gabbana, and even contemporary independent brands, to countless artists and pop culture references. She has also become a powerful figure for feminist and LGBTQ+ communities, her defiance of gender norms, her exploration of gender fluidity, and her celebration of her authentic self speaking volumes across generations. Her art has achieved global superstardom, making her one of the most recognizable and commercially successful female artists in history. It's a strange thing, seeing her image so widely commercialized today, from t-shirts to pop art – a testament to her enduring appeal, but sometimes I wonder if the intensity of her raw, unfiltered message gets lost in the commodification. Yet, even through that lens, her spirit persists. Frida's courage to express her unique vision inspires my own artistic journey, and if you're curious about that, you can see my own artistic timeline or perhaps explore some of the abstract and colorful art for sale that I create. It’s always inspiring to see how others break boundaries, and Frida certainly set a high bar for that.

What Frida taught the world is that true strength often lies in confronting our deepest pains and expressing them with unflinching honesty. And if you ever find yourself wandering through the Netherlands, don't forget to stop by our own museum in 's-Hertogenbosch to experience art that also aims to connect deeply with the human experience. Frida teaches me, constantly, that art isn't about chasing some unattainable perfection; it’s about honest, courageous expression. And sometimes, that honesty is messy, painful, and absolutely, unequivocally beautiful. What does Frida Kahlo’s legacy mean for your understanding of art and resilience today? I'd love to hear your thoughts, or perhaps you'll find your own inspiration for creation.

Frequently Asked Questions About Frida Kahlo

What makes Frida Kahlo so famous?

Frida Kahlo's fame stems from a potent combination of factors: her intensely personal and symbolic art that unflinchingly depicted her physical and emotional suffering, her indomitable spirit in the face of immense pain, her tumultuous marriage to muralist Diego Rivera, and her strong identification with Mexican folk culture and political beliefs. She broke traditional molds, presenting an authentic and often shocking self-narrative, and her iconic image has permeated popular culture and fashion globally.

What was Frida Kahlo's most famous painting?

While it's difficult to pick just one, The Two Fridas is arguably her most iconic and widely recognized work. Other extremely famous and pivotal paintings include The Broken Column and Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird.

What influenced Frida Kahlo's art?

Frida Kahlo's art was profoundly influenced by several key factors:

- Chronic Pain and Health Issues: Resulting from polio and her devastating bus accident, including multiple surgeries and the use of orthopedic corsets, leading to constant physical and emotional suffering.

- Diego Rivera: Her tumultuous and passionate relationship with him, which also fostered significant artistic and intellectual exchange and mutual inspiration.

- Mexican Culture: Traditional Mexican folk art, pre-Columbian artifacts, the concept of 'Mexicanidad,' and influences from retablo and ex-voto painting, all deeply integrated into her aesthetic.

- Political Beliefs: Her strong communist ideals and commitment to social justice, viewing art as a powerful tool for social change and empowerment.

- Personal Identity: Her complex heritage, bisexuality, and defiant self-expression, exploring themes of gender fluidity, female subjectivity, and a rejection of societal norms.

Was Frida Kahlo a Surrealist?

While her works often share visual characteristics with Surrealism due to their dreamlike and symbolic qualities, Frida Kahlo herself famously rejected the label. She asserted that she painted her own reality, not dreams, making her work distinct from the core tenets of the Surrealist movement as defined by André Breton. Many art historians, however, still categorize some of her work within the broader Surrealist sphere due to its strong psychological and symbolic content.

What is the significance of Casa Azul (The Blue House)?

Casa Azul, Frida Kahlo's childhood home in Coyoacán, Mexico City, holds immense significance as it was not only where she was born, lived much of her life, and eventually died, but also served as a source of deep inspiration for her art. It housed her extensive collection of Mexican folk art and pre-Columbian artifacts, directly influencing her unique aesthetic and deep connection to Mexicanidad. Beyond her personal life, it was also a vital hub for political and artistic discourse, hosting figures like Leon Trotsky and Isamu Noguchi, and fostering a vibrant intellectual environment. Today, it stands as the Frida Kahlo Museum, offering an intimate glimpse into her world and creative process.

How did Frida Kahlo's bisexuality influence her art and identity?

Frida Kahlo was openly bisexual, an aspect of her life that was progressive for her time and is reflected in her art through its exploration of fluid identity and defiance of conventional norms. While not always explicit, her relationships with both men and women informed her complex understanding of love, desire, and self, contributing to the rich tapestry of her personal narrative that she so unflinchingly presented on canvas. Her defiance of traditional gender roles and her embrace of authentic self-expression made her a significant figure for LGBTQ+ communities.

How has Frida Kahlo influenced popular culture and fashion?

Frida Kahlo's distinct visual style – her elaborate hairstyles, traditional Tehuana dresses, and iconic unibrow – along with her defiant spirit, have made her an enduring fashion and pop culture icon. Her image is widely recognized, appearing on merchandise, influencing designers like Jean Paul Gaultier and Dolce & Gabbana, and inspiring countless artists and celebrities who admire her authenticity, resilience, and unique aesthetic. Her unapologetic embrace of her Mexican heritage and personal struggles has made her a powerful symbol of individuality and cultural pride.

How did Frida Kahlo influence feminist art and identity politics?

Frida Kahlo is widely regarded as a proto-feminist icon and a significant figure in feminist art history. Her groundbreaking and unflinching depiction of female experience, suffering, identity, and sexuality on canvas, often through highly personal and symbolic self-portraits, challenged traditional male-centric narratives in art. She explored themes of reproduction, abortion, miscarriage, physical pain, and gender fluidity with a raw honesty that was revolutionary for her time, paving the way for future feminist artists to reclaim the female body and experience as valid subjects for art and political discourse. Her work is central to discussions on female agency, bodily autonomy, and self-representation.

How did Frida Kahlo navigate the male-dominated art world of her time?

Frida Kahlo often operated somewhat independently from the mainstream art institutions, heavily supported by Diego Rivera's reputation initially. However, she was known for her unyielding personality and her refusal to compromise her artistic vision or personal style, even when it challenged the conservative norms of the era. Her distinct voice and unique subject matter, often centered on female experience, pain, and identity, carved out a space for her that transcended traditional gender barriers, though not without struggle. She forged her own path, becoming a powerful example of female artistic agency and influencing artists and critics who recognized the profound authenticity and power in her work.

How did Frida Kahlo challenge traditional notions of beauty and the female body in her art?

Frida Kahlo radically redefined beauty by rejecting idealized forms and instead embracing her authentic, often suffering, body on canvas. Through unflinching self-portraits, she depicted her physical disfigurements, medical corsets, and the realities of menstruation, miscarriage, and surgery – subjects traditionally considered taboo or un-beautiful in art. This audacious honesty challenged patriarchal beauty standards, celebrating a more raw, vulnerable, and ultimately powerful representation of the female form and experience. She transformed personal pain into a universal statement on human resilience and self-acceptance, creating a profound dialogue around body image and female agency that continues to resonate today.