Interpreting Body Language in Portrait Art: An Expanded Artist's Guide

Unlock the silent stories in painted faces and figures. My expanded artist's guide to interpreting body language in portrait art, from posture, hands, and gaze to facial nuances, clothing, context, and the artist's hand.

How to Interpret Body Language in Portrait Art: An Expanded Artist's Guide

Have you ever stood in front of a portrait, maybe in a quiet museum hall or even just a print on someone's wall, and felt like the person in the painting was trying to tell you something? Not with words, obviously, but with a tilt of the head, the set of their jaw, or the way their hands are clasped? That's the magic of body language in art, and honestly, it's one of my favorite things to 'read' when I'm looking at portraits. It's like a silent conversation across centuries. Sometimes, I think my best training for reading portraits is just people-watching in cafes – you see the same tells, just in motion, though perhaps less deliberately posed! It's fascinating how a few brushstrokes can capture a whole mood, a personality, or even a hidden thought. You can find art that tells stories in unexpected places, too, like local cafes or boutiques, which is a bit like finding these silent narratives on canvas (finding art in unexpected places).

I remember standing in front of a Renaissance portrait once – I think it was in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, years ago (best galleries in florence). The sitter, a woman, was posed formally, but the way her fingers were intertwined, almost hidden, and the slight tension around her eyes, spoke volumes. It wasn't just a depiction of her likeness; it felt like a window into her inner world, a quiet tension beneath the surface of societal expectation. That moment really solidified for me how much narrative is packed into those non-verbal cues. This guide focuses primarily on painted portraits, though many principles apply to photographic ones too, with some key differences we'll touch on. It's also worth noting that interpreting historical body language isn't always straightforward; our modern understanding can sometimes clash with centuries-old conventions, adding another layer to the mystery. It's like trying to decipher a language where some of the slang has been lost to time.

As an artist, I spend a lot of time thinking about how to convey feeling and narrative without relying on literal representation. Even in abstract work, it's about form, color, and composition speaking a kind of silent language (art elements). But in portraiture, that silent language becomes incredibly specific – it's the language of the human body. It reminds me that even in my own abstract pieces, the gesture of the paint, the posture of a shape, is trying to communicate something visceral. It's all about that non-verbal communication, isn't it? It's like the canvas itself has body language. Sometimes, when I'm struggling to capture a certain emotion in a figure, I'll actually try the pose myself in the mirror. It feels a bit silly, but understanding the physical tension or relaxation in my own body helps me translate it onto the canvas. It's a strange, physical empathy.

Let's dive into how you can start interpreting these silent signals and connect with portraits on a deeper level. It's less about being an art historian (though a little context helps!) and more about being a keen observer of people, which, let's be honest, we all are to some extent! Think of it as learning how to read a painting, but with a specific focus on the human form.

Why Body Language Matters in Art

Think about meeting someone new. Before they even say a word, you're already getting information from them, right? Their posture, their handshake (or lack thereof), the way they hold themselves. Art is no different. A portrait isn't just a visual record of what someone looked like; it's often a carefully constructed narrative about who they were, or at least, who the artist (or the sitter) wanted them to appear to be. It's a deliberate act of visual storytelling.

Body language adds layers of meaning that go beyond just facial features. It can reveal power dynamics, vulnerability, confidence, anxiety, or even defiance. It's the artist's way of giving the figure a voice, even in silence. It's a crucial part of the overall composition and narrative. Understanding these non-verbal cues in art can even sharpen your observation skills in everyday life, helping you connect more deeply with the people around you, just as you connect with the figures on the canvas. It's a skill that keeps giving, both in the gallery and on the street.

Reading the Visual Cues: Signals from the Figure and the Canvas

So, what specifically should you look for when you're trying to 'read' a portrait? It's a bit like being a detective, piecing together clues from the canvas. We can break it down into signals coming directly from the figure's body and those coming from the broader context the artist provides.

Signals from the Figure

These are the most direct forms of body language, emanating from the person depicted. Pay close attention to these key areas:

Posture and Stance

How is the person holding themselves? Is the person standing tall and rigid, or relaxed and leaning? Are their shoulders back, chest out (suggesting confidence or authority), or are they slumped (perhaps indicating weariness or humility)? A figure seated squarely and upright might convey formality or importance, while someone lounging might suggest informality or ease. Even the angle of the head – tilted slightly, held high, or bowed – can add layers of meaning, suggesting contemplation, pride, or submission. The way weight is distributed, the curve of the spine, the tension in the neck – these all contribute to the overall physical story.

And what about the lower half? If the legs and feet are visible, their position can be incredibly telling. Are the feet planted firmly, suggesting stability and rootedness? Are they pointed towards something or someone, indicating interest or intention? Crossed legs might imply a closed-off attitude or simply comfort, depending on the context. A figure depicted mid-stride or with one foot forward might suggest readiness for action or movement, even if frozen in time. Think of a portrait where the sitter's upper body is formal, but their feet are casually crossed or angled away – that subtle detail can create a fascinating tension or hint at a personality trait beneath the formal facade.

Consider the stark contrast in posture between two famous works. In Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, her relaxed, slightly turned posture and folded hands convey a sense of calm presence and perhaps inner contemplation, inviting the viewer in. Compare this to the rigid, upright, almost confrontational stance often seen in official portraits of monarchs or military figures from the Baroque era, like Hyacinthe Rigaud's portrait of Louis XIV, where every element, including his posture, is designed to project absolute power and authority (dramatic art styles). Or think about the classical contrapposto pose, where a figure stands with most of their weight on one foot, creating a subtle asymmetry in the body – a relaxed, natural-looking stance. This pose, popular since antiquity and revived in the Renaissance, often suggests relaxation, potential movement, and a sense of naturalism, contrasting sharply with the stiff, frontal poses of earlier periods.

Or think about the deeply affecting hunched posture in Picasso's "The Old Guitarist". The way his back is curved, his head bowed over the instrument, speaks volumes about weariness, poverty, and profound sorrow. It's not just that he's old and playing guitar; it's how he holds himself that tells the story of a life burdened by hardship.

Posture is the foundation of the figure's presence on the canvas; it sets the initial tone for how we perceive them.

Physical Condition and Life Stage

Beyond posture and texture, the artist's depiction of the figure's physical condition and life stage tells its own story. Is the figure depicted in the bloom of youth, robust health, or showing the signs of age, illness, or weariness? An artist might use subtle cues like the rendering of skin tone, the prominence of bones, the way the body holds itself under the weight of years, or even signs of physical labor or injury to convey a narrative about the sitter's life and experiences. Think of the vibrant energy captured in portraits of young people, often depicted with dynamic poses and smooth skin, versus the quiet stillness and visible lines of experience in portraits of the elderly. This adds another layer of 'body language' – the story the body itself carries through time and through its lived state.

Hands and Arms

Hands are incredibly expressive! As an artist, I can tell you they are also notoriously difficult to paint well, which is perhaps why artists put so much effort into making them count. Sometimes getting a hand right feels like solving a tiny, expressive puzzle. I've spent hours just trying to get the angle of a thumb or the tension in a knuckle to look right, only to realize how much emotion even a slightly tense finger could convey. It's a subtle language all its own (artists who mastered drawing hands). Are they open and relaxed, clenched into fists, or hidden? Are they gesturing, holding an object, or resting? Clasped hands can suggest piety, nervousness, or contemplation. Hands holding a tool or book might indicate their profession or interests. Hidden hands can sometimes imply distrust or concealment.

But there's so much more! Consider the 'orator's pose', common in classical and Renaissance art, where a hand is raised with fingers slightly curled, as if in mid-speech or argument – a clear signal of intellectual engagement or authority. Hands placed firmly on the hips can convey confidence, assertiveness, or even defiance. Arms crossed might suggest defensiveness, skepticism, or simply a closed-off posture. And the objects held can be deeply symbolic: a flower might represent beauty or fleeting life, a skull a reminder of mortality (a memento mori), or a mirror a symbol of vanity or self-reflection (understanding symbolism).

Beyond these general gestures, specific objects held in the hands carry significant meaning depending on the era and context. In Renaissance portraits, holding a pair of gloves often signified wealth and status, as gloves were expensive accessories. A single coin or a small pile of coins could denote prosperity or a merchant's profession. A prayer book or rosary clearly indicated piety, while a compass or scientific instrument pointed to intellectual pursuits or specific trades. Even the way an object is held – delicately, firmly, or casually – adds nuance. A hand resting lightly on a sword hilt projects a different kind of power than a hand gripping it tightly. These small details, often overlooked, are packed with symbolic body language.

Look at how hands are depicted in older portraits. In many Renaissance portraits, like those by Leonardo da Vinci or Raphael, the precise, almost performative placement of fingers or the holding of an object like a book or glove carries specific meaning about the sitter's character, education, or status. A hand pointing upwards might signify divine inspiration or direction, while an open palm could indicate honesty or offering. In contrast, consider the hands in a portrait by Egon Schiele, where they might be contorted or angular, reflecting the sitter's psychological state or inner turmoil, aligning with the Expressionist focus on emotion over realism (ultimate guide to expressionism). Or look at the specific hand mudras in traditional Indian miniature paintings, which are highly codified gestures conveying spiritual states, emotions, or narratives – a fascinating example of culturally specific body language in art (how different cultures depict symbols in art).

Hands are often secondary focal points after the face, carrying significant symbolic weight and adding layers of narrative.

Facial Expression

Okay, this one seems obvious, but it's more than just a smile or a frown. Subtle shifts in the eyes, the corners of the mouth, or the tension in the brow can convey a huge range of emotions. Is the smile genuine (crinkling around the eyes) or forced? Is there a hint of sadness behind a neutral expression? Artists are masters at capturing these fleeting moments, sometimes even hinting at complex psychological states or inner conflict through subtle facial cues. Sometimes, the expression isn't meant to be easily readable at all, creating a deliberate ambiguity that invites the viewer to project their own feelings or interpretations onto the face.

Beyond the eyes and brow, the mouth is a surprisingly powerful indicator. Is it relaxed, slightly open, or tightly pursed? Pursed lips can signal disapproval, tension, or secrecy. A relaxed jaw might suggest ease or contemplation, while a tight jaw can indicate stress or determination. Even the subtle visibility of teeth can change the perceived emotion – a wide, toothy grin versus a closed-mouth smile tells a different story. Capturing the exact curve of the lips or the tension around the mouth is one of those small details that can make or break the emotional impact of a portrait. It's tricky to get right, but when an artist nails it, it feels like they've captured a whole inner world. I've definitely spent ages just on the mouth, trying to get that tiny hint of a smirk or that shadow that suggests a furrowed brow. It's maddening and magical.

Artists can also capture or imply incredibly subtle muscle movements – the tiny tightening around the eyes that signals genuine joy, the slight quiver of the lip before tears, or the almost imperceptible clenching of the jaw that betrays inner frustration. These microexpressions, though perhaps not consciously painted stroke-by-stroke, can be suggested through the artist's keen observation and rendering of light and shadow, adding layers of psychological depth to the portrait.

It's interesting to note the historical shift in depicting emotion. In earlier periods, like the Middle Ages or early Renaissance, facial expressions were often more stylized and symbolic, conveying general states like piety or nobility rather than specific, nuanced emotions. Think of the serene, almost uniform expressions in many Byzantine icons. As art progressed through the Renaissance and into the Baroque and Romantic periods, artists became increasingly interested in capturing the full range of human feeling, leading to more psychologically complex and emotionally charged facial depictions. The Romantic era, in particular, embraced dramatic expressions of passion, despair, and ecstasy, making the face a primary vehicle for conveying intense inner states (dramatic art styles).

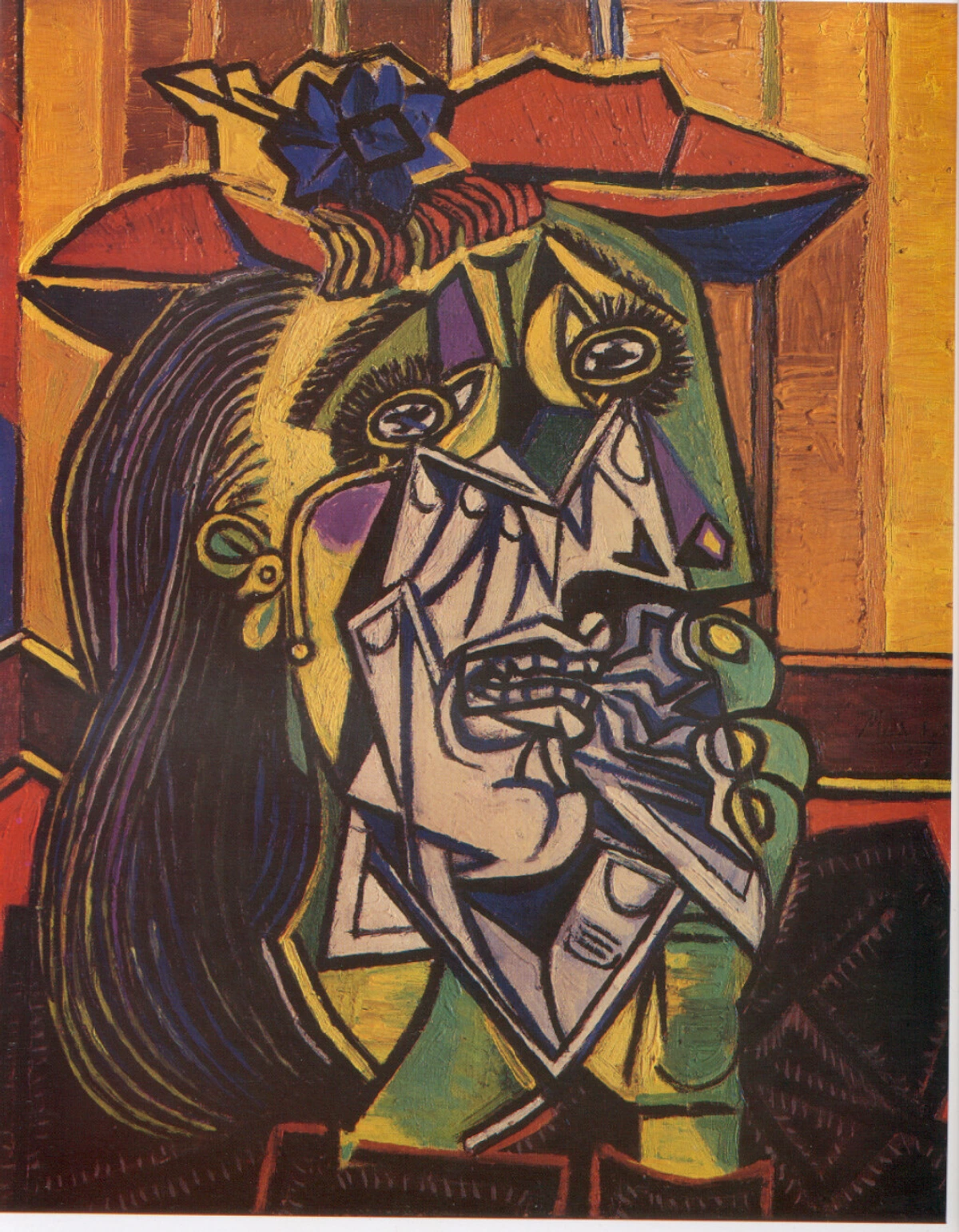

Picasso's portraits, even his Cubist ones, often have incredibly expressive faces, despite the distortion. Think of the raw emotion in his "Weeping Woman". Even with fragmented features, the angle of the head and the lines around the eyes scream anguish. It's a powerful example of how expression can transcend realistic depiction (ultimate guide to cubism).

The face is usually the primary point of connection, but its expression is deeply intertwined with the rest of the body's signals and the subtle nuances captured by the artist.

Gaze and Eye Contact

Where are the eyes looking? Are they meeting yours directly, looking away shyly, or gazing into the distance? Direct eye contact creates an immediate connection and can convey confidence, challenge, or intimacy. Averted eyes might suggest humility, introspection, or avoidance. Looking into the distance can imply contemplation, hope, or detachment.

Sometimes, the eyes follow you around the room! This isn't magic, but a clever trick of perspective. Because the portrait is a flat, 2D image, the direction of the gaze is fixed relative to the canvas. Your brain, used to processing a 3D world, interprets this fixed gaze as following you as you move. It's a fascinating optical illusion, but it certainly adds to the feeling of being observed or connected to the subject.

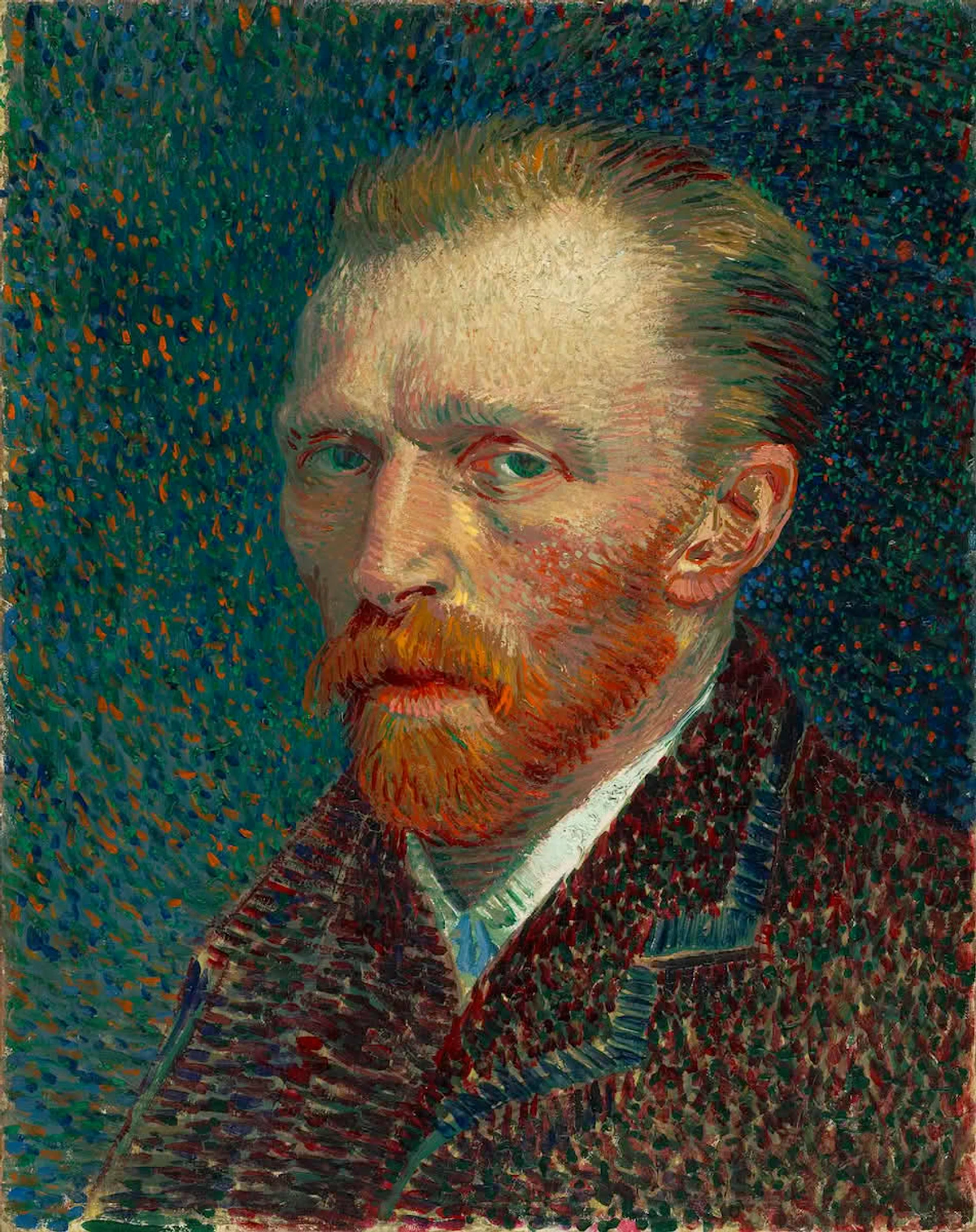

Consider the intense, direct gaze in many self-portraits, like those by Vincent van Gogh, which often feels confrontational and deeply personal, pulling you into his emotional world. In contrast, the downcast or averted gaze in many religious paintings of saints or the Virgin Mary conveys piety and humility. Or think of a portrait where the subject is looking intently at something within the painting itself – perhaps a letter they hold, a pet on their lap, or another figure in a group portrait. This directs your gaze, the viewer's, into the narrative space of the painting, forcing you to consider what has captured their attention and interpret that interaction. This subtle interaction between figures, even in a single portrait (like a mother holding a child and looking down at them), adds another layer to the body language narrative.

The direction of the gaze is a powerful tool for the artist to control the viewer's interaction with the portrait and hint at connections within or beyond the frame.

Signals from the Canvas and Context

While not strictly 'body language' in the physical sense, other elements within the portrait profoundly influence how we interpret the figure's physical presence and emotional state. Think of them as the stage and atmosphere surrounding the actor, providing crucial context that shapes our understanding of the body language on display. These elements work in concert with the figure's pose and expression to build the complete narrative.

Clothing and Props

The way clothing is worn (tightly buttoned vs. loose), the style of dress itself, or the objects the person holds (a sword, a flower, a book, a pet) are not just decorative. They are deliberate choices by the artist and sitter that add context and emphasize aspects of their body language or status. A sword might reinforce a powerful stance, while a delicate flower could soften a stern expression or highlight vulnerability. The richness or simplicity of clothing speaks volumes about social standing, which in turn influences how a pose is perceived. Think of the elaborate lace collars and stiff fabrics in Dutch Golden Age portraits, like those by Rembrandt or Frans Hals, which dictate a certain formality of posture, contrasting with the more flowing garments and relaxed poses sometimes seen in Rococo portraits.

Sometimes, the clothing or a prop creates a fascinating contrast with the figure's body language, adding complexity. Imagine a figure with a relaxed, almost casual posture, perhaps leaning slightly, but simultaneously holding a symbol of immense power or authority, like a crown or scepter. This juxtaposition creates a tension – are they comfortable with their power, or is the casual pose a deliberate subversion of expectation? Or consider a portrait of a child dressed in stiff, formal adult clothing, their small body looking uncomfortable and constrained despite a perhaps neutral facial expression. The clothing here amplifies a sense of vulnerability or imposed formality that the posture alone might not fully convey.

Clothing and props are visual cues that reinforce or contrast with the physical signals, adding layers of social, symbolic, and personal meaning.

Texture and Drape

The depiction of texture – the rendering of skin, fabric, hair, or objects – also subtly influences how we perceive the figure's physical presence and state. Smooth, polished skin might suggest youth or idealized beauty, while visible wrinkles or rough texture can convey age, hardship, or vulnerability. The heavy folds of velvet or the delicate lace of a collar don't just show wealth; they can influence the perceived weight and formality of the figure's posture. A rough, textured background might make a figure feel more grounded or rugged, while a smooth, ethereal rendering could enhance a sense of grace or detachment. Texture adds a tactile layer to the visual language, making the figure feel more real or deliberately stylized.

Crucially, the drape and texture of clothing itself acts as a form of body language. Heavy, stiff fabrics like brocade or thick wool often necessitate and reinforce a rigid, formal posture, conveying status and immobility. Think of the elaborate gowns and suits in 17th-century portraits – the clothing itself seems to hold the sitter in place. In contrast, light, flowing fabrics like silk or linen allow for more relaxed, dynamic poses and can suggest ease, movement, or even sensuality. The way fabric folds and falls can echo the lines of the body, emphasizing its form, or create a sense of volume and presence that dominates the figure. Tight clothing can imply constraint or tension, while loose garments might suggest freedom or informality. The artist's skill in rendering these textures and drapes is key to how the figure's physical state and social context are perceived.

Composition and Framing

How the figure is placed within the canvas, and how much of them is shown, dramatically impacts how we read their body language (art composition). Is it a tight head-and-shoulders portrait, forcing focus entirely on the face and subtle expressions? Or a full-body portrait, where the entire stance and interaction with the environment become paramount? A figure placed centrally and filling the frame often suggests importance and dominance, while a figure off-center or small within a large canvas might imply isolation, vulnerability, or a focus on the surrounding narrative.

Consider a portrait where only the hands are visible, perhaps engaged in a task. This framing choice immediately shifts the focus of 'body language' to the dexterity, tension, or grace of the hands alone. The artist's decision on what to include and exclude, and how to arrange it, is a fundamental layer of interpretation.

The angle from which the figure is viewed also plays a significant role. A frontal view can feel confrontational or direct, inviting immediate engagement. A profile view might suggest introspection, detachment, or a focus on something outside the frame. A three-quarter view is often considered more dynamic and natural, allowing the artist to capture both facial expression and body posture effectively. This compositional choice influences the viewer's perceived relationship with the subject – are you being directly addressed, observing from a distance, or invited into their space?

Composition provides the visual structure that guides our reading of the figure's physical presence.

Color and Light

The artist's use of color and light profoundly influences the mood of the portrait and, consequently, how we interpret the figure's expression and posture (how artists use color, how artists use light and shadow dramatically). A figure with a slightly melancholic expression might appear devastated if bathed in dark, somber shadows and muted colors, but merely pensive if rendered in soft, warm light and brighter tones. Dramatic chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) can heighten a sense of drama, tension, or inner conflict, making even a still pose feel charged with energy.

Think of the difference between a brightly lit Impressionist portrait, capturing a fleeting moment of light and ease (ultimate guide to impressionism), versus a Rembrandt portrait where a face emerges from deep shadow, suggesting introspection and complexity. The color palette – warm reds and yellows versus cool blues and greens – also sets an emotional stage that colors our perception of the figure's physical state. You can dive deeper into this in my guide on how artists use color.

Color and light are the emotional atmosphere surrounding and influencing our reading of the body.

Absence and Negative Space

Sometimes, what isn't there is as important as what is. The space around the figure, the negative space, can amplify the feeling conveyed by their body language (role of negative space abstract art). A small figure in a vast, empty room or landscape might feel isolated or overwhelmed, even if their posture is outwardly confident. Conversely, a figure tightly framed with no background might feel confined or intensely present.

Consider a portrait where a figure is turned away from the viewer, showing only their back. This deliberate absence of the face forces us to read the story purely through their posture, the tension in their shoulders, or the way their head is tilted. It creates mystery and shifts the focus entirely to the physical form's expressive potential. It's a powerful way to make you feel the weight of their stance or the direction of their unseen gaze.

Negative space and absence are silent partners to the figure's body language, shaping its meaning.

Setting and Background

Is the person in a grand hall, a natural landscape, an intimate room, or against a plain backdrop? The setting is never neutral. It influences how we perceive their posture and expression. A relaxed pose in a formal setting might feel rebellious or confident, while the same pose in a garden feels natural and serene. A stormy sky behind a figure can amplify a sense of drama or inner turmoil, while a peaceful domestic interior reinforces a calm demeanor. The background provides the stage upon which the body language performs.

Consider Thomas Gainsborough's portraits, where sitters are often placed in lush, natural landscapes. This setting complements their relaxed, elegant poses and flowing garments, suggesting a connection to nature and a certain aristocratic ease. Contrast this with the plain, often dark backgrounds favored by artists like Hans Holbein the Younger for his portraits of Tudor courtiers. The lack of a distracting background forces the viewer to focus intensely on the sitter's face, hands, and clothing, making their subtle body language and the details of their attire even more significant in conveying their status and personality.

Sometimes, the setting creates a deliberate contrast with the figure's body language, highlighting a specific message. Imagine a figure with a powerful, assertive stance, perhaps even clenching a fist, but placed against a backdrop of ruins or a desolate landscape. This contrast could suggest defiance in the face of adversity, a struggle against decay, or a commentary on the fleeting nature of power. Or picture a figure with a vulnerable, slumped posture, but surrounded by symbols of immense wealth and luxury – this might speak to the emptiness of material possessions or a hidden sorrow despite outward success.

The setting is the environment that contextualizes and amplifies the figure's physical presence, adding crucial narrative depth.

The Artist's Signature

Even the placement of the artist's signature or mark can subtly interact with the portrait's body language. Is it prominently placed, almost like another element in the composition, perhaps near the figure's hand or eye, drawing attention to the act of creation or the artist's presence? Or is it discreetly tucked away, suggesting humility or a focus solely on the sitter? While not body language of the figure, this final 'gesture' by the artist on the canvas can influence how we perceive the finished work and the artist's relationship to the subject. It's a final, quiet statement.

Historical and Cultural Context: The Silent Rules

Understanding the era and culture in which a portrait was created is absolutely vital. Body language isn't universal; it's shaped by societal norms and artistic conventions. What was considered a dignified or appropriate pose in the 16th century might look stiff or unnatural to us today. It's like trying to understand slang from a different decade – the words are the same, but the meaning has shifted. Understanding the history of art and different art styles helps immensely here.

Here's a quick look at some typical conventions across different eras:

Era / Movement | Typical Body Language Conventions | Examples / What to Look For |

|---|---|---|

| Renaissance & Baroque | Formality, idealized poses, emphasis on piety, power, virtue. Highly symbolic hand gestures. Rigid, upright posture for status. | Orator's pose, hand on chest (sincerity/loyalty), specific finger arrangements (blessing/theology). Stiff postures in portraits of royalty/nobility. Dramatic poses in Baroque art. |

| 18th & 19th Centuries | Slightly more relaxed poses, but still conveying respectability, wealth, intellect. Integration with props (books, globes). Rise of emotional postures in Romanticism. | Hand-in-waistcoat gesture (calmness/authority). Leaning on objects. Figures gazing into distance (contemplation/hope). Visible distress/passion in Romantic portraits. |

| Modernism and Beyond | Shift towards candid, everyday postures. Capturing fleeting moments. Body distortion to express inner states. Challenging conventions. | Informal poses (Renoir). Psychological intensity through distortion (Expressionism). Body used to challenge norms (Modern art). |

Cultural nuances also play a role. While Western art history dominates many museum collections (best museums in europe, best galleries in the world), looking at portraits from other traditions reveals different visual languages. For instance, the use of specific hand mudras in Indian miniature painting conveys spiritual states or narratives, a system very different from European traditions. Similarly, the emphasis on stillness and specific ceremonial postures in some East Asian portraiture reflects different cultural values around presentation and selfhood. Consider the significance of specific head coverings, ways of sitting (like kneeling or cross-legged), or even the direction a figure faces relative to others or the viewer in non-Western traditions – these are all forms of culturally coded body language that require specific knowledge to interpret accurately (how different cultures depict symbols in art). Acknowledging these diverse traditions reminds us that 'body language in art' is a vast, global conversation.

Furthermore, the purpose of the portrait heavily influenced body language conventions. A formal state portrait intended for public display demanded a pose conveying authority, dignity, and stability, often involving specific regalia or symbols of power. A marriage portrait might emphasize harmony and connection between the sitters, perhaps through linked hands or proximity. A private portrait for family could allow for more relaxed, intimate poses. Memorial portraits sometimes depicted the deceased in idealized or symbolic states. Understanding why the portrait was commissioned provides crucial context for interpreting the chosen body language. It wasn't just about capturing a likeness; it was about fulfilling a specific social or political function.

It's also important to consider how age and gender conventions historically shaped acceptable body language in portraits. Women were often depicted with poses emphasizing modesty, grace, or domesticity, frequently with hands clasped or holding symbolic objects like flowers or prayer books. Men's poses often conveyed assertiveness, intellect, or power, showing them with swords, books, or hands on hips. Children were typically shown in poses suggesting innocence, playfulness, or simply as miniature adults, depending on the era's view of childhood. These conventions weren't rigid rules but strong societal expectations that artists and sitters navigated, sometimes adhering to them strictly, and sometimes subtly subverting them.

Understanding these 'silent rules' of the time and place helps you discern what was conventional versus what might have been a deliberate choice by the artist or sitter to convey something unique or even subversive. It's like learning the grammar of a visual language that changes over time and across borders.

Self-Portraits: The Artist as Subject

Interpreting body language takes on a unique dimension in self-portraits. Here, the artist is both the creator and the subject, navigating the complex interplay of self-perception, desired presentation, and artistic intention. When an artist paints themselves, the body language isn't just a reflection of the sitter's state; it's a deliberate statement by the artist about their identity, mood, or status. It's a strange, introspective process, trying to capture your own essence and decide how you want the world to see you, or perhaps how you truly see yourself, flaws and all. Think of:

- Vulnerability vs. Confidence: Does the artist present themselves confidently, perhaps with a direct gaze and strong posture (like many of Dürer's self-portraits emphasizing his status), or do they show vulnerability, weariness, or introspection (like many of Van Gogh's later self-portraits)?

- Tools of the Trade: Are they depicted with brushes, palettes, or other tools? This isn't just a prop; it's body language emphasizing their profession and skill, often with hands prominently displayed. It's like saying, "These hands? These are the hands that make things." I've definitely painted myself looking utterly exhausted after a long day in the studio – that's a kind of body language too!

- Psychological Exploration: Some artists use self-portraits to delve into their own psychological state, using posture, expression, and even distortion to convey inner turmoil or complex emotions. Egon Schiele's contorted self-portraits are prime examples of this intense introspection. It's like they're using their own body on the canvas as a way to work through what's going on inside.

- Artist's Mood: The artist's own mood or state of mind while painting can subtly seep into the work and influence the perceived body language of the subject, even if that subject is themselves. If I'm feeling anxious, that tension might unconsciously translate into tighter brushstrokes or a more rigid rendering of my own form in a self-portrait. It's a fascinating feedback loop between the creator's physical and emotional state and the resulting image.

Self-portraits offer a fascinating window into the artist's mind, where the body language is a carefully curated form of self-expression. It's like they're having a silent conversation with themselves on the canvas, and we get to listen in. You can see some of my own journey as an artist reflected in my timeline.

Interpreting Body Language in Group Portraits

Reading body language gets even more complex – and fascinating – in group portraits. Here, it's not just about the individual, but about the relationships between the figures. Look at:

- Proximity: How close or far apart are people standing or sitting? Closeness can suggest intimacy or alliance, distance might indicate formality or tension.

- Interaction: Are they looking at each other, touching, or ignoring one another? Eye lines and gestures can create connections or reveal divisions within the group. Who is leaning towards whom? Who is physically turning away?

- Hierarchy: Who is positioned centrally? Who is higher or lower? Who is making direct eye contact with the viewer? These spatial cues often reflect social status or importance within the depicted group, or perhaps a deliberate subversion of that hierarchy by the artist.

- Unified vs. Disconnected: Does the group feel cohesive, with similar poses or a shared focus, or do the figures seem isolated, each lost in their own world? This can tell you a lot about the dynamic the artist intended to portray – a harmonious family, a tense political meeting, or a collection of individuals brought together by circumstance.

Think of Dutch Golden Age group portraits, like Rembrandt's "The Night Watch" or Frans Hals' The Officers of the St. George Militia Company. These aren't static lineups; the figures are engaged in conversation, gesturing, and interacting. Hals, in particular, was a master at capturing the lively, almost boisterous energy of these militia groups. You see officers turning to speak to each other, hands resting on shoulders, varying levels of formality in posture and gaze – all working together to create a sense of dynamic collective identity and individual personality within the group, a far cry from the more static, formal group portraits of earlier eras. Or consider a family portrait where one member is slightly turned away or has a different expression – what might that subtle difference signify about their relationship to the others or their inner state?

Group portraits turn the reading of body language into a study of human relationships and social dynamics on canvas, making them incredibly rich sources for interpretation.

The Artist's Hand: Interpretation and Intention

It's important to remember that the body language we see in a portrait isn't always a perfect, objective capture of the sitter's natural state. The artist plays a significant role. They might:

- Direct the Pose: The artist often instructs the sitter on how to stand, sit, or hold their hands to convey a specific message or adhere to artistic conventions of the time. Think of how many formal portraits feature sitters in very similar, almost prescribed poses. This was often a collaboration, with the sitter wanting to be portrayed in a certain light, and the artist using their skill to achieve that, sometimes subtly injecting their own perspective. Sometimes you want them to look profound, and they just want you to hide their double chin... it's a delicate balance! I've definitely had moments in my own work where I'm trying to capture a certain feeling, and the pose just isn't cooperating, or the sitter's natural inclination is different from the narrative I'm trying to build. It's a constant negotiation between observation and intention.

- Interpret and Emphasize: An artist's style and perspective can influence how they render subtle cues. They might exaggerate a certain posture or expression to emphasize a trait they see (or want to portray). This is particularly evident in styles like Expressionism, where emotion is amplified through distortion. As an artist myself, I know that even when trying to capture a likeness, my own feelings about the subject, or the mood I want to evoke, inevitably influence the lines I draw and the colors I choose. It's never a purely neutral act.

- Reflect the Commission: The purpose of the portrait (e.g., official state portrait, intimate family painting, self-portrait) heavily influences the choices made about pose and expression. A portrait intended for public display will likely feature more formal, controlled body language than one meant for a private collection. Was the artist commissioned to flatter, to reveal truth, or to capture a specific moment?

- Project Their Own Feelings: Sometimes, an artist might unconsciously (or consciously) project their own feelings or biases onto the sitter, influencing the perceived mood or personality in the final work. This is where the artist's own 'body language' comes into play, not physically, but through their style and choices. Looking at an artist's self-portraits can be incredibly revealing because they are both the subject and the interpreter, navigating these layers of intention themselves.

- Sitter's Status and Power: The social status and power of the sitter also significantly influenced the artist's freedom. Painting royalty or powerful patrons often meant adhering to strict conventions and idealizing the subject, limiting the artist's ability to capture candid or vulnerable body language. A portrait of a less powerful individual or a self-portrait might allow for more experimentation and a more 'realistic' depiction of physical and emotional states. The power dynamic in the studio could directly impact the body language on the canvas.

Understanding the artist's background, the historical context, and the likely purpose of the portrait adds another layer to your interpretation. It's a dialogue between the sitter, the artist, and you, the viewer.

While this guide focuses primarily on painted portraits, the principles of reading body language extend to photographic portraits too. However, there's a key difference: a photograph captures a moment, while a painting is a construction over time. A photographer might capture a spontaneous gesture, but they also direct poses, choose lighting, and select the final image, all of which influence the perceived body language. A painter has even more control, building the pose stroke by stroke, potentially combining elements observed over many sittings or even inventing them entirely. The implications for interpretation are significant – in a painting, every tilt of the head or placement of a hand is a deliberate choice built over time, whereas in a photograph, it might be a fleeting instant, albeit one chosen and framed by the photographer. It's like the difference between catching a candid snapshot and meticulously choreographing a scene. Both mediums use body language to tell a story, but the artist's hand (or eye) shapes that story in distinct ways.

It's also worth acknowledging the inherent subjectivity and potential challenges in interpreting historical body language. Our modern understanding of gestures, postures, and expressions is shaped by our own cultural context and experiences. A gesture that seems neutral or even negative to us today might have had a specific, positive meaning centuries ago. Conventions that were widely understood at the time might be lost to us now. This means our interpretations are always, to some extent, filtered through our present-day lens. While historical research and understanding context help bridge this gap, there's always a degree of educated guesswork involved. It's a reminder that art interpretation is an ongoing conversation, not a fixed science.

Reading the Clues: A Step-by-Step Approach

Ready to put on your detective hat and try interpreting a portrait yourself? Here's a simple way to approach it, applying the concepts we've just discussed. Don't worry about getting it 'right' – it's about engaging and finding your own connection. Remember, interpretation is a blend of observation, context, and your own intuition.

- Observe the Whole: First, just take it in. What's your initial feeling about the person? Do they seem powerful, sad, happy, mysterious? Don't overthink it yet. Let your gut react. Sometimes that first impression, before your brain kicks in with analysis, is the most honest. Also, pay attention to your own physical reaction – do you feel drawn in, pushed away, intrigued? Your body language as a viewer can mirror or contrast with the subject's. How does your physical position relative to the portrait – standing close, far away, looking up or down at it – influence your initial feeling?It's also important to acknowledge that your own cultural background, personal experiences, and even current mood will inevitably influence how you interpret the body language in a portrait. Someone who has experienced hardship might read weariness into a posture that someone else sees as merely relaxed. A specific gesture might trigger a personal association. This isn't a flaw in your interpretation; it's part of the dynamic interaction between the viewer and the artwork. Embrace your unique perspective, while also being open to learning about the historical and cultural context that shaped the artist's and sitter's world.

- Focus on Key Areas: Now, look specifically at the Signals from the Figure (Posture, Physical Condition/Life Stage, Hands, Facial Expression, Gaze) and the Signals from the Canvas and Context (Clothing/Props, Texture/Drape, Composition/Framing, Color/Light, Absence/Negative Space, Setting/Background, Artist's Signature). What do these individual elements seem to be saying? Note any tension, relaxation, openness, or concealment. Are there any contradictions that make the portrait more intriguing? For instance, a figure with a confident stance but hidden hands, or a serene expression in a chaotic setting. As you do this, try to consider the relationship between these different elements – how does the hand gesture relate to the facial expression? How does the setting contrast with the posture? They're all working together.Here's a quick cheat sheet for the figure's signals:| Element | What to Look For | Potential Interpretations (Context is Key!) | | :------------------ | :------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | :----------------------------------------------------------------------------- | | Posture/Stance | Upright, slumped, leaning, weight distribution, head angle, spine curve, legs/feet position | Confidence, humility, weariness, formality, relaxation, contemplation, pride, readiness, intention | | Physical Condition/Life Stage | Skin tone, wrinkles, bone prominence, signs of labor/illness, age depiction | Health, age, hardship, experience, youth, vulnerability, resilience | | Hands/Arms | Open, clenched, clasped, gesturing, holding objects, arms crossed, hands on hips | Piety, nervousness, contemplation, profession, interests, distrust, authority | | Facial Expression | Subtle shifts in eyes, mouth corners, brow tension, jaw, visibility of teeth, microexpressions | Happiness, sadness, anxiety, determination, secrecy, ease, inner conflict | | Gaze/Eye Contact| Direct, averted, looking into distance, looking within the painting | Confidence, challenge, intimacy, humility, introspection, avoidance, detachment|

- Consider the Context: This is where you bring in the detective work. Who was this person (if known)? When and where was the portrait painted? What was the social, historical, or cultural context? What was the likely purpose of the portrait? Were there specific conventions for portraiture at that time or in that place, especially regarding age, gender, or social status? Understanding the history of art helps immensely here. For instance, knowing that a certain hand gesture was common in religious art might change your interpretation of it in a secular portrait. Consider the artist's background and the purpose of the commission – were they aiming for flattery, realism, or something else? How might the sitter's status have influenced the artist's choices?

- Piece it Together: Combine the visual clues from the figure and their surroundings with the historical and cultural context. Do the signals align? Are there contradictions? What story emerges when you look at all the pieces? It's like building a profile based on visual evidence. Be open to multiple possibilities; there isn't always one single 'correct' answer. Interpretation is subjective and layered, influenced by both the painting and your own perspective.

- Trust Your Gut: Finally, combine the visual clues and context with your own emotional reaction. Art is subjective, and your personal interpretation is valid. What does the body language feel like to you? Sometimes, the most profound insights come from that initial, intuitive response. Don't dismiss your own feelings just because you're not an expert. Your connection is real.

I remember once looking at a portrait that seemed quite stern at first glance. But then I noticed the slight curve at the corner of the mouth and the way one hand was gently resting on a pet, and the whole impression shifted to one of quiet strength and affection. It's all in the details, and sometimes you have to look past the obvious to find the subtle truths.

Practice Tip

The best way to get better at this is simply to look at more portraits! Visit a museum (or explore online galleries) with the specific goal of 'reading' the body language in just a few pieces. Pick one portrait and spend five minutes just observing the details we've discussed. What story does the body tell before you even know the sitter's name? Try comparing two portraits from different eras or styles, focusing only on how the figures hold themselves. What differences do you notice, and what might they tell you? Another great practice is to try sketching or quickly drawing a pose from a portrait, focusing only on the lines of the body. This helps you isolate the physical form and understand its expressive power without getting caught up in details like facial features or clothing. You could even try to mimic a pose you see in a portrait. Stand like the sitter, hold your hands like they do. How does it feel? Does it feel natural, strained, powerful, vulnerable? This physical empathy can give you a surprising insight into the sitter's potential state or the artist's intention. And don't forget to people-watch in everyday life! Observing how people hold themselves, use their hands, or express emotions subtly in a cafe or on the street is fantastic training for recognizing those same cues, frozen in time, on a canvas. You can even practice by visiting local art galleries and focusing on the portraits there.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How does the artist's style affect how we interpret body language?

Significantly. A realistic portrait might capture subtle nuances, while a stylized or expressionistic portrait might exaggerate certain features or poses to convey a more intense emotional state. Think of the difference between a detailed Renaissance portrait and a bold Fauvist one (ultimate guide to fauvism) – the interpretation of a similar pose could feel very different due to the artist's hand and use of color/form. Understanding different art styles helps.

How does historical and cultural context affect interpreting body language?

Immensely. What was considered polite, powerful, or emotional varied greatly throughout history and across cultures. A stiff, formal pose might have been required by convention in one era or culture, while a more relaxed pose was acceptable in another. Objects held, clothing worn, and even acceptable facial expressions were dictated by the times and cultural norms. The purpose of the portrait (state, marriage, private) and societal expectations around age and gender also played a huge role. Understanding the history of art and specific cultural nuances is crucial. Interpreting body language in a 17th-century Dutch portrait requires a different lens than interpreting it in a 21st-century photographic portrait.

Is the body language in a portrait always intentional?

Not always. Sometimes it's a natural pose the artist captured, sometimes it's carefully directed by the artist or the sitter, and sometimes it's the artist's own interpretation or projection onto the subject. It's a mix of conscious choice, artistic convention, cultural norms, and subconscious expression. It's rarely purely accidental, but the degree of intention can vary. It's also important to remember that our modern understanding of body language might lead us to misinterpret historical cues, and sometimes the sitter's own unconscious habits or comfort level might subtly influence the pose, adding another layer of complexity beyond just artist/sitter intent or convention. The sitter's social status or power could also limit the artist's freedom to capture a truly candid pose.

How does interpreting figurative body language relate to understanding abstract art?

That's a great question! While abstract art doesn't depict human figures, the principles of conveying emotion, energy, and narrative through visual elements are shared. In abstract art, the 'body language' is in the composition, the brushstrokes, the colors, the textures – how these elements interact and 'hold themselves' on the canvas. Just as a slumped posture conveys weariness in a portrait, a drooping line or muted color palette might convey a similar feeling in an abstract piece. It's about the artist using the visual language of form and color to evoke a response, much like a portrait artist uses the visual language of the body. My own abstract work, for instance, often focuses on the energy of lines and the mood of colors, trying to make the paint itself feel alive and expressive, much like a figure in a portrait. It's about the tension and flow within the composition, the 'stance' of the shapes, the 'gesture' of the brushstroke – a different kind of physical presence.

How do non-Western art traditions approach body language in portraits?

Non-Western traditions often have distinct and rich visual languages for depicting the body. As mentioned earlier, Indian miniature paintings use specific mudras (hand gestures) that are highly symbolic and convey spiritual states or narratives, a system very different from Western hand symbolism. In some East Asian traditions, emphasis might be placed on stillness, specific ceremonial postures, or the symbolic significance of clothing and accessories to convey status, virtue, or inner calm, rather than dynamic movement or overt emotional expression. The direction a figure faces, their position relative to others, or even the way they are seated (e.g., cross-legged, kneeling) can carry deep cultural meaning. Exploring these traditions highlights that body language in art is a diverse, global phenomenon, requiring specific cultural knowledge for accurate interpretation (influence of non-western art on modernism).

Interpreting body language in portrait art is a rewarding way to engage with paintings. It turns passive viewing into an active conversation across time and space. It's about looking closely, feeling, and connecting the dots. It's a skill that deepens your appreciation not just for portraiture, but for how artists use visual language in all its forms.

It's funny, sometimes I look at a portrait I've seen a hundred times, and suddenly a tiny detail – the way a shadow falls across a hand, or the subtle tension in a shoulder – unlocks a whole new understanding. It's a reminder that art, like people, is endlessly complex and always has more to reveal if you just keep looking, and keep feeling. It's this constant discovery that keeps me coming back to the canvas, both as a viewer and as a creator, trying to capture those fleeting moments of expression myself.

So next time you see a portrait, take a moment to look beyond the face. What is the body telling you? What about the hands, the clothing, the setting? What story does the composition frame? You might be surprised by the stories you uncover. And who knows, maybe it will even change the way you look at the 'body language' of abstract shapes and colors!

And hey, if you're looking for art that speaks to you, in its own unique way, feel free to browse my collection here.