The Silent Language: How Different Cultures Speak Through Symbols in Art - An Artist's Guide

Symbols in art are a silent, powerful language. Join an artist's journey exploring how different cultures, from ancient times to contemporary art, use symbols to convey deep meaning, history, and emotion. Discover the power, evolution, interpretation, and personal connection to visual language, including archetypes and artist responsibility.

The Silent Language: How Different Cultures Speak Through Symbols in Art

Symbols. They're everywhere, aren't they? From the mundane traffic signs that guide our daily commutes to the profound emblems that represent nations or beliefs. As an artist, I've always been captivated by how much meaning can be packed into a single shape, color, or figure. It's like a secret language, whispered across time and space, a hidden conversation happening just beneath the surface of what we see. For me, working with abstract forms and vibrant colors, understanding this silent language is key to infusing my own work with feeling and depth. It's not always about literal representation; sometimes, it's about tapping into something deeper, something universally felt yet culturally specific.

I remember standing in front of a piece years ago, a contemporary work that seemed simple on the surface – just a few bold shapes and colors. But something about it felt... weighted. Significant. It wasn't until later, reading about the artist's cultural background, that I realized those shapes weren't just shapes; they were echoes of ancient symbols, carrying stories I hadn't known how to 'read'. It was a powerful moment, like unlocking a hidden door. It made me realize just how much of the world's visual conversation happens beneath the surface. And it got me thinking about how this silent language isn't just for looking at, but for creating too. How do artists, myself included, tap into this deep well of meaning? It's a constant dance between conscious intent and intuitive flow, trying to capture something felt rather than just seen.

Sometimes, though, this silent language can be tricky. I recall seeing a beautiful, intricate pattern in a textile piece once and assuming it was purely decorative. Later, I learned it was a specific cultural symbol denoting status or lineage – something I had completely missed. It was a humbling reminder that my own cultural lens isn't the only one, and that without context, even the most beautiful forms can remain silent in ways I don't intend. It made me appreciate the layers, and sometimes the potential for misinterpretation, that symbols carry. It's like trying to read a map without a legend – you see the lines, but the meaning is lost. This experience really drove home the point that understanding the context is everything when it comes to symbols in art.

But what happens when this language enters the realm of art? How do different cultures, with their unique histories, beliefs, and ways of seeing the world, wield the power of symbols? That's what I've been pondering lately, and I'd love to take you on a little journey through my thoughts and discoveries. Have you ever looked at a simple shape, like a circle or a triangle, and felt it held more meaning than just its form? Or wondered why a certain color makes you feel a particular way when you see it in a painting? It's a fascinating rabbit hole to fall down, trust me. Sometimes I feel like I need a decoder ring just to look at a tapestry!

It's easy to look at a painting or sculpture and just see the surface – the colors, the forms, the technique. But often, beneath that surface lies a rich tapestry of symbols, woven by the artist to communicate something deeper. Something that transcends mere representation. It's like finding hidden notes in a piece of music, adding layers of complexity and emotion.

Maybe you've felt it too? Standing in front of a piece, feeling a connection, even if you can't quite articulate why. Sometimes, that connection comes from recognizing, consciously or unconsciously, the symbols at play. It's a conversation between you, the artwork, and the culture it sprang from. Understanding symbolism is like gaining a superpower when you're looking at art. It unlocks layers of meaning you might otherwise miss. It's something I touch upon when thinking about how to read a painting – looking beyond the obvious to find the narrative threads.

Ready to put on your own decoder ring? Let's dive in and see how this silent language speaks across the globe.

So, What Are These Silent Speakers? Defining Symbols in Art

At its core, a symbol in art is anything that stands for or suggests something else. It could be an object, a color, an animal, a gesture, or even an abstract shape. The key is that its meaning isn't inherent in its form alone; it's assigned by a culture, a tradition, or even the artist themselves. Think of it like a traffic light: the color red doesn't inherently mean 'stop' in nature, but we've all agreed that when we see a red light, we stop. Symbols in art work in a similar way, but often with far more layers and nuance. A simple geometric shape, like a spiral, can symbolize growth or the cosmos in one culture, or a journey in another. It's all about shared understanding.

Are symbols in art always intentional? Not always! Sometimes an artist might use a symbol consciously, drawing on established cultural meanings. Other times, a symbol might emerge from their subconscious, or viewers might interpret something as symbolic even if the artist didn't intend it. It's a complex interplay, sometimes wonderfully ambiguous, sometimes frustratingly opaque.

Think about it. A dove isn't just a bird; it's often a symbol of peace. A red color isn't just a pigment; it can symbolize love, passion, or danger. These meanings aren't universal, though. And that's where the fascinating cultural differences come in.

Closely related to symbolism is allegory. While a symbol is typically a single element representing something else (a dove = peace), an allegory is a more extended form, a narrative or visual representation where characters, objects, or events collectively represent abstract ideas or principles. It's like an extended metaphor, telling a story that has a hidden, symbolic meaning. Think of a painting depicting Justice as a blindfolded woman with scales – she's not just a woman; the whole figure and her attributes form an allegory for the concept of justice. Or a painting showing a figure battling vices; the figures and actions symbolize moral struggle. It's symbolism woven into a story, often used to convey moral, religious, or political messages. To put it simply, if a symbol is a word, an allegory is a whole sentence or paragraph using those words to tell a deeper story. A simple, non-art example? A fable like 'The Tortoise and the Hare' is an allegory – the characters and their race symbolize abstract ideas like perseverance versus overconfidence.

Why Do Cultures Use Symbols in Art?

Why bother with this 'silent language' at all? What makes symbols such a persistent and powerful tool in artistic expression across time and place? It's not just about making things look pretty; it's about communication, connection, and continuity. It's about packing centuries of thought or feeling into a single visual cue.

Cultures use symbols in art for a multitude of reasons, often intertwined:

Reason | Brief Explanation/Example |

|---|---|

| To Convey Complex Ideas | Difficult concepts expressed visually. Think of a Yin-Yang symbol representing balance – faster than an essay! |

| To Preserve History/Beliefs | Carry weight of generations, transmit stories, myths, doctrines. Medieval stained glass taught biblical stories to the illiterate. |

| To Evoke Emotion | Deeply tied to cultural emotional responses (reverence, fear, joy). A national flag evokes patriotism. |

| For Identification/Unity | Create belonging, collective identity. Family crests or tribal patterns. |

| Communicate Across Literacy | Powerful way to share messages when literacy is low. Early Christian art used symbols like the fish. |

| Spiritual/Religious Connection | Act as conduits to the divine, represent deities, sacred concepts. The cross in Christianity or Om in Hinduism. |

| Aesthetic/Decorative | Used for visual appeal, often retaining underlying meaning. Geometric patterns in Islamic art symbolize God's infinite nature. |

| Social/Political Commentary | Critique society, express dissent, make political statements. A broken chain symbolizing liberation or oppression. |

It's a powerful tool, this symbolic language. It allows art to be more than just decoration; it becomes a carrier of culture, history, and the human experience. It's a way for the past to speak to the present, and for artists to connect with something larger than themselves. Even outside of traditional art, think about the symbolism of national flags or heraldry – simple designs packed with history, identity, and shared values, instantly recognizable to those who share the culture.

The Power and Peril of Symbols

Symbols are powerful precisely because they condense complex ideas and emotions into easily recognizable forms. They can unite people, transmit knowledge, and evoke profound feelings. But this power also carries potential peril. As symbols evolve and are reinterpreted, their original meanings can be lost, distorted, or even weaponized. It's a bit like a game of telephone across centuries and continents – the message can get twisted.

As seen with the Swastika, symbols can be co-opted and twisted from their original positive meanings to represent hate and destruction. Historical symbols of power or identity can be used for propaganda or to reinforce oppressive regimes. In contemporary society, corporate logos become symbols of consumerism and global capitalism, sometimes critiqued or subverted by artists and activists. Think of how street artists use familiar symbols in new contexts to make political statements, as seen in street art. Or how political movements might adopt or adapt symbols to rally support, sometimes with divisive results. It's a constant battleground of meaning.

Symbols can also be misinterpreted across cultures or time periods, leading to misunderstandings or unintended offense. What is sacred in one context might be mundane or even taboo in another. This highlights the importance of context and knowledge when engaging with symbolic art. Without understanding the cultural background, you might miss the entire point – or worse, misread it completely. It's a humbling reminder that my own understanding is just one perspective in a vast, complex world of meaning. It's one thing for a symbol's meaning to shift naturally over time within a culture, and another for it to be deliberately taken and used for a purpose completely antithetical to its origin. Recognizing this difference is key to understanding the ethical dimension of using symbols.

Understanding the history and cultural context of a symbol is crucial, not just for interpretation, but for recognizing its potential impact and how it might be used or misused. It's a reminder that this silent language, while beautiful and profound, is also a potent force in shaping human perception and interaction.

A World of Symbols: A Journey Through Cultural Visual Languages

Exploring symbols across different cultures is like opening a series of treasure chests, each filled with unique and sometimes surprising meanings. These are just a few of the cultures whose symbolic languages have particularly opened my eyes and influenced my own thinking about visual communication. Ready to travel the world through symbols? Let's start way back...

Prehistoric Art: Early Marks of Meaning

Long before written language, humans were making marks that carried meaning. Cave paintings, like those at Lascaux or Chauvet, feature not only depictions of animals but also abstract signs – dots, lines, geometric shapes. While their exact meanings are debated, these marks are believed to have served symbolic or ritualistic purposes, perhaps related to hunting magic, shamanism, or recording observations. The Venus figurines, found across Eurasia, are potent symbols of fertility or a mother goddess. These early symbols show a fundamental human need to imbue the visual world with deeper significance, a practice that continues to this day.

Beyond representational forms, prehistoric art often features recurring abstract motifs that seem to hold symbolic weight across different sites and continents. Think of zigzags, often interpreted as representing water or lightning; spirals, suggesting growth, the cosmos, or journeys; and meanders, perhaps symbolizing rivers or winding paths. These simple, universal shapes appear again and again, hinting at shared human experiences and early attempts to map the world and the spiritual realm through visual language. It's fascinating to think about these ancient artists, using basic forms to communicate complex ideas about life, nature, and the unknown. As an artist who works with abstract forms, I find a deep connection to these early marks – they feel like the very beginnings of a universal visual language, tapping into something fundamental about how we perceive and organize the world through shape and line.

Ancient Egypt: Hieroglyphs, Deities, and Cosmic Order

Moving from the earliest marks, let's journey to a civilization where symbolism was intricately woven into every aspect of life. Ancient Egyptian art is absolutely packed with symbols, deeply integrated into their complex religious and social system. Their hieroglyphic writing system itself was deeply intertwined with imagery, where symbols represented not just sounds but also concepts. You see this everywhere, from grand temple walls to intricate sarcophagi and papyrus scrolls like the Book of the Dead. The reason symbolism was so central was its role in maintaining maat, the cosmic order and balance. Maat wasn't just a concept; it was the fundamental principle of truth, justice, and cosmic harmony that the pharaoh and the people were responsible for upholding. Art wasn't just decoration; it was a tool to ensure the world functioned correctly, to guide the dead, and to honor the gods.

Beyond writing, every element in their art often held symbolic weight. The scarab beetle symbolized rebirth and regeneration. The Ankh, a cross with a loop, represented life. The Eye of Horus symbolized protection and royal power. Colors had specific meanings too – green for new life, red for chaos or power, blue for the heavens or the Nile. Their art wasn't just pretty pictures; it was a system for maintaining cosmic order, communicating with the gods, and ensuring passage to the afterlife. Every pose, every object, every animal depicted served a symbolic purpose. Looking at the detailed carvings, like those found in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, you feel the weight of their beliefs, the intricate system designed to guide souls and maintain balance. I remember seeing an Ankh symbol for the first time and being struck by its simple elegance, yet knowing it held such profound meaning for an entire civilization. It makes you wonder what it must have felt like to live in a world where every image held such sacred weight. Egyptian symbolism shows us how art can be a vital, functional part of maintaining a worldview.

Mesoamerican Art: Cosmology, Deities, and Calendars

Journeying across the Atlantic, we find the rich and complex symbolic systems of Mesoamerica, particularly the Maya and Aztec civilizations. Their art, seen in monumental architecture, intricate carvings (like stelae), vibrant codices, and pottery, is deeply tied to their cosmology, religious beliefs, and sophisticated calendar systems. Symbolism was essential here for recording history, tracking astronomical events, and appeasing a complex pantheon of deities who governed every aspect of life.

- Feathered Serpent (Quetzalcoatl/Kukulkan): A major deity symbolizing creation, wind, wisdom, and the morning star. A powerful, composite symbol often depicted with both bird feathers and snake scales.

- Jaguar: Represents power, the underworld, and royalty. A creature of mystery and strength, often associated with rulers and night.

- Maize: Symbolizes life, sustenance, and the cycle of birth and death. Fundamental to their existence and often depicted as a sacred plant.

- Specific Glyphs: Their writing systems were logographic and syllabic, with many glyphs functioning as symbols representing deities, places, or concepts. A complex visual language in itself, often found carved into stone monuments or painted in books. Definitely need more than just a decoder ring for that!

Colors also held specific symbolic meanings tied to direction and cosmology – red for the East, black for the West, white for the North, and yellow for the South. Their art was not merely representational but served to reinforce social order, appease the gods, and record history and astronomical observations. The symbols are often layered and complex, requiring deep cultural knowledge to fully interpret. The sheer density of meaning in their carvings and codices is astounding; it feels like an entire universe captured in visual form. It makes you appreciate the incredible effort and knowledge embedded in every piece, often housed in places like the National Museum of Anthropology in Madrid. (Though, side note, the one in Mexico City is truly mind-blowing if you ever get the chance!). Mesoamerican art reminds us how visual language can be intricately tied to time, space, and the divine.

Indian Art: Spirituality, Mythology, and Philosophy

In the vast and diverse artistic traditions of India, symbolism is fundamental, drawing heavily from Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and other spiritual and philosophical systems. Art serves as a vehicle for devotion, storytelling, and conveying complex theological ideas, appearing in temple sculptures, miniature paintings, textiles, and ritual objects. Symbolism here is deeply tied to the path of spiritual liberation and understanding the nature of reality.

- Lotus: A ubiquitous symbol representing purity, spiritual awakening, and creation, often seen as the seat of deities. Rising clean from muddy water, it's a powerful image of transcendence.

- Mudras: Symbolic hand gestures in Buddhist and Hindu iconography, each conveying specific meanings (e.g., teaching, meditation, fearlessness). A silent language of the hands, crucial for understanding the meaning of deity depictions. Honestly, trying to learn all the mudras feels like learning a whole new sign language!

- Deities' Attributes: Objects held by gods and goddesses (like Shiva's trident, Vishnu's conch shell, Durga's weapons) are powerful symbols of their powers and roles. Each object tells a story about the deity's nature and function.

- Animals: Beyond attributes, animals like the elephant (strength, wisdom, royalty, associated with Ganesha), peacock (beauty, immortality, rain), and cow (sacredness, motherhood) carry significant symbolic weight.

- Mandala: Geometric configurations symbolizing the universe, used in meditation and ritual. A visual aid for cosmic contemplation and spiritual journey.

- Swastika: An ancient symbol of prosperity and good fortune (predating its horrific appropriation in the 20th century). A stark reminder of how symbols can be twisted.

Indian art is a visual language rich with layers of meaning, where every posture, color, and object contributes to the overall spiritual or narrative message. Visiting museums with extensive Indian collections, like the British Museum in London or the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC, offers a glimpse into this depth. The way spirituality is woven into the visual fabric is incredibly powerful and moving. You can find incredible examples in the best galleries and museums in India. Indian art shows us how symbols can be pathways to spiritual understanding and devotion.

East Asian Art: Nature, Philosophy, and Spirituality

In many East Asian cultures, particularly China and Japan, symbols drawn from nature are incredibly significant and deeply intertwined with philosophical and spiritual beliefs (like Taoism, Buddhism, and Shinto). These appear in everything from classical ink wash paintings (like those by masters of the Literati tradition) to ceramics, textiles, garden design, and calligraphy. Symbolism in this context often reflects a deep reverence for the natural world and its cycles, and a desire for harmony with it. There's a quiet wisdom in these symbols that always makes me pause and breathe a little deeper.

- Bamboo: Symbolizes resilience, flexibility, and integrity because it bends but doesn't break. A quiet strength I admire.

- Plum Blossom: Represents perseverance and hope, as it blooms in late winter. A beautiful reminder that beauty can emerge even in harsh conditions.

- Dragons: Often symbolize power, strength, and good fortune (unlike the often fearsome Western dragon). A dynamic, benevolent force associated with water and the heavens.

- Cranes: Symbolize longevity and immortality. Elegant and graceful creatures often depicted in pairs.

- Pine: Represents endurance and steadfastness, remaining green through winter. A symbol of constancy and longevity.

- Fish (especially Carp): Symbolize perseverance and success, due to their ability to swim upstream. A powerful metaphor for overcoming challenges.

- Calligraphy: While a form of writing, calligraphy in East Asia is also a high art form where the characters themselves become symbolic, representing not just words but also the artist's spirit, discipline, and connection to tradition. The brushstrokes, the composition, the ink's intensity – all carry symbolic weight.

These symbols are not just decorative motifs but carry centuries of cultural and philosophical weight. They often appear in subtle ways, requiring a quiet contemplation similar to appreciating the art itself. The elegance and depth of meaning in these natural symbols always strike me; they feel like quiet meditations on the world and our place within it. The use of negative space, or emptiness, in ink wash painting is itself a symbolic element, representing the void, potential, or the unmanifested, adding another layer of philosophical depth. You can explore this rich tradition in places like the Tokyo National Museum. East Asian art teaches us the profound symbolism found in the cycles and forms of nature.

Islamic Art: Geometry, Calligraphy, and Divine Unity

Islamic art, spanning a vast geographical area and many centuries, is characterized by its avoidance of figural representation in religious contexts, leading to a rich development of abstract and symbolic forms, particularly geometry and calligraphy. This focus stems from the belief that depicting human or animal forms could lead to idolatry. Symbolism here is a way to express the divine without representation, focusing on unity, order, and the infinite.

- Geometric Patterns: Intricate and repeating geometric patterns (stars, polygons, interlacing lines) are not merely decorative. They symbolize the infinite nature of God (no beginning or end), the order of the cosmos, and the interconnectedness of all things. Creating these complex patterns is seen as an act of meditation and devotion.

- Calligraphy: Arabic calligraphy is the most revered art form in Islamic culture. Verses from the Quran, sayings of the Prophet, or other significant texts are rendered in beautiful, often elaborate scripts. The act of writing these words is sacred, and the written word itself becomes a powerful symbol of divine revelation and beauty. Different scripts carry different associations and are used in various contexts, from monumental architecture to illuminated manuscripts.

- Arabesque: Flowing, rhythmic patterns of scrolling vines and leaves, often intertwined with geometric forms or calligraphy. These symbolize the infinite growth and abundance of nature, reflecting the beauty of God's creation.

- Color: While meanings can vary regionally, blue is often associated with the heavens and spirituality, green with paradise, and gold with divine light.

- Materials: Even the materials used can carry symbolic weight. The use of precious metals like gold can symbolize divine light or purity, while specific stones or woods might have regional or historical associations.

Islamic art uses these abstract and calligraphic symbols to create environments that inspire contemplation and reflect theological principles. The architecture of mosques, the decoration of manuscripts, the design of textiles – all employ this symbolic language to evoke a sense of divine presence and cosmic harmony. It's a powerful reminder that symbolism doesn't require representation; abstract forms can carry profound meaning. Islamic art demonstrates the power of abstraction to convey the divine and cosmic order.

African Art: Community, Status, and Ritual

Across the diverse cultures of the African continent, symbols in art are often deeply integrated into daily life, ritual, and social structure. They appear in masks, sculptures, textiles, pottery, and body art, conveying information about identity, status, lineage, spiritual beliefs, and historical narratives. Art is often functional, meant to be used in ceremonies or as markers of social roles. Symbolism here is less about contemplation and more about active participation in community life and connection to the spiritual world.

- Adinkra Symbols (Ghana): A collection of visual symbols, each with a distinct meaning and proverb, used in fabrics (like Kente cloth), pottery, and walls (e.g., Sankofa, meaning 'return and get it', symbolizing the importance of learning from the past; Gye Nyame, 'except for God', symbolizing God's omnipotence). A beautiful system of visual proverbs that communicate complex ideas concisely. It's like a whole philosophy woven into cloth!

- Yoruba Symbols (Nigeria/Benin): Symbols related to deities (Orishas), kingship, and social roles (e.g., the double axe of Shango, god of thunder; the bird on a king's crown, symbolizing ancestral power). Connecting the earthly and divine through visual language.

- Masks: Often highly symbolic, representing spirits, ancestors, or forces of nature, used in ceremonies to mediate between the human and spiritual worlds. More than objects, they are conduits for spiritual energy and transformation.

- Body Art and Scarification: Patterns and symbols applied to the body can signify tribal affiliation, social status, rites of passage, or spiritual protection. The body becomes a canvas for identity and belief.

- Animals: Animals often carry symbolic weight, representing specific traits, spirits, or social groups (e.g., the leopard symbolizing chieftainship among the Kuba people).

- Materials and Techniques: The choice of materials (wood, metal, beads, textiles) and techniques (carving, weaving, casting) can also be highly symbolic, tied to specific rituals, status, or spiritual power.

African art is incredibly varied, but a common thread is the functional nature of symbolism – it's not just for contemplation but actively used to maintain social cohesion, educate, and connect with the spiritual realm. The vitality and directness of this symbolic communication are truly striking. It's art that does something. You can see examples in major museums worldwide or explore contemporary connections through artists of the African Diaspora. African art reminds us that symbols are often meant to do something, not just be looked at.

Western Art: Religious, Mythological, and Allegorical Narratives

Moving from the structured narratives of African art, let's journey back to the West, where symbolism has also played a crucial, though often shifting, role. Western art history is rich with symbolism, though the dominant themes and styles have shifted dramatically over time. Symbolism often served religious, mythological, or political narratives. The purpose of symbolism here has often been to instruct, moralize, or tell stories from shared cultural texts like the Bible or classical myths.

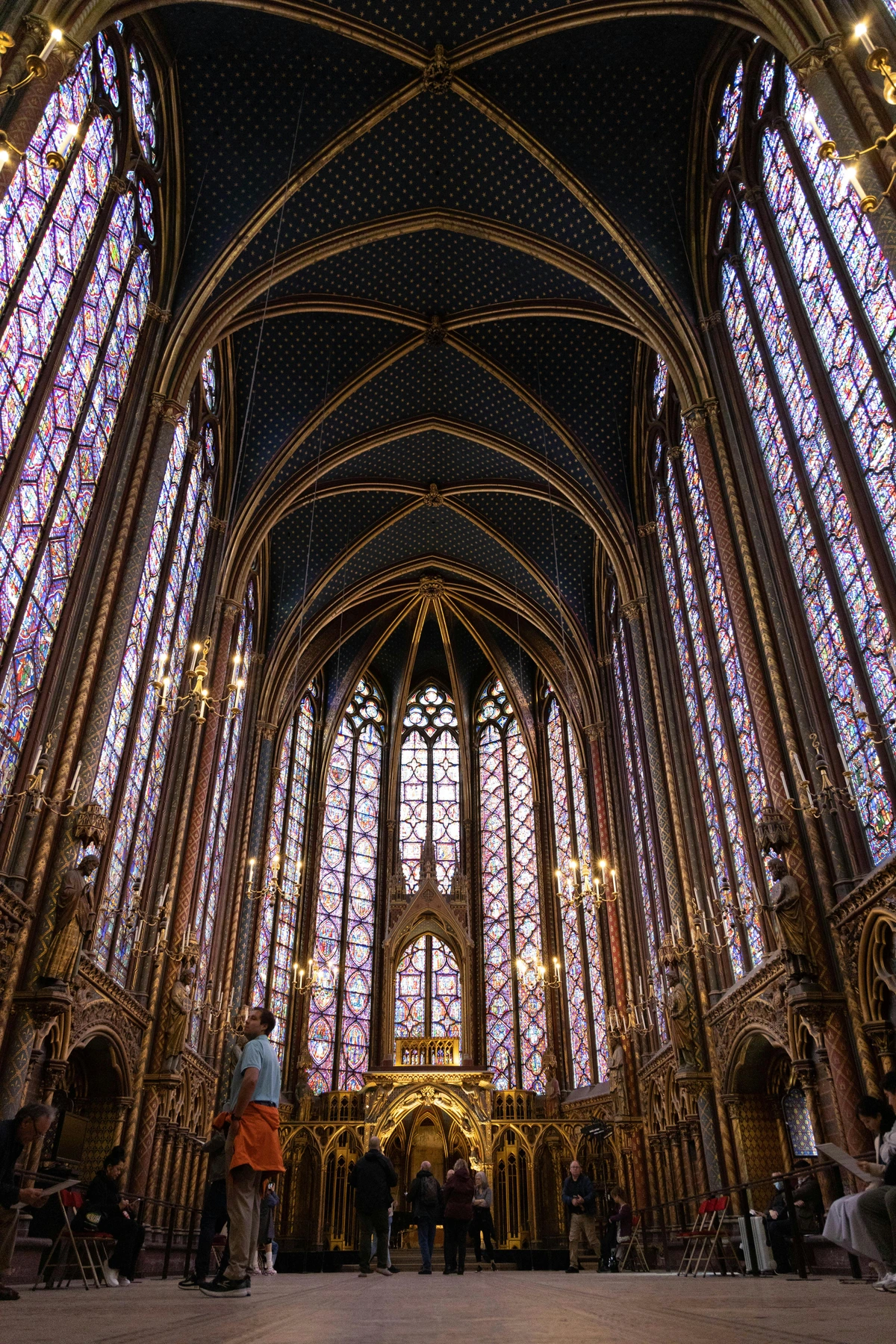

- Medieval and Renaissance: Christian symbolism was paramount. Lambs symbolized Christ, lilies purity, keys the authority of the Church. Colors held specific meanings (blue for the Virgin Mary, gold for divinity). Works like Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait are famously packed with hidden symbols related to marriage, faith, and social status. Sainte-Chapelle's stained glass tells biblical stories through symbolic imagery and light.

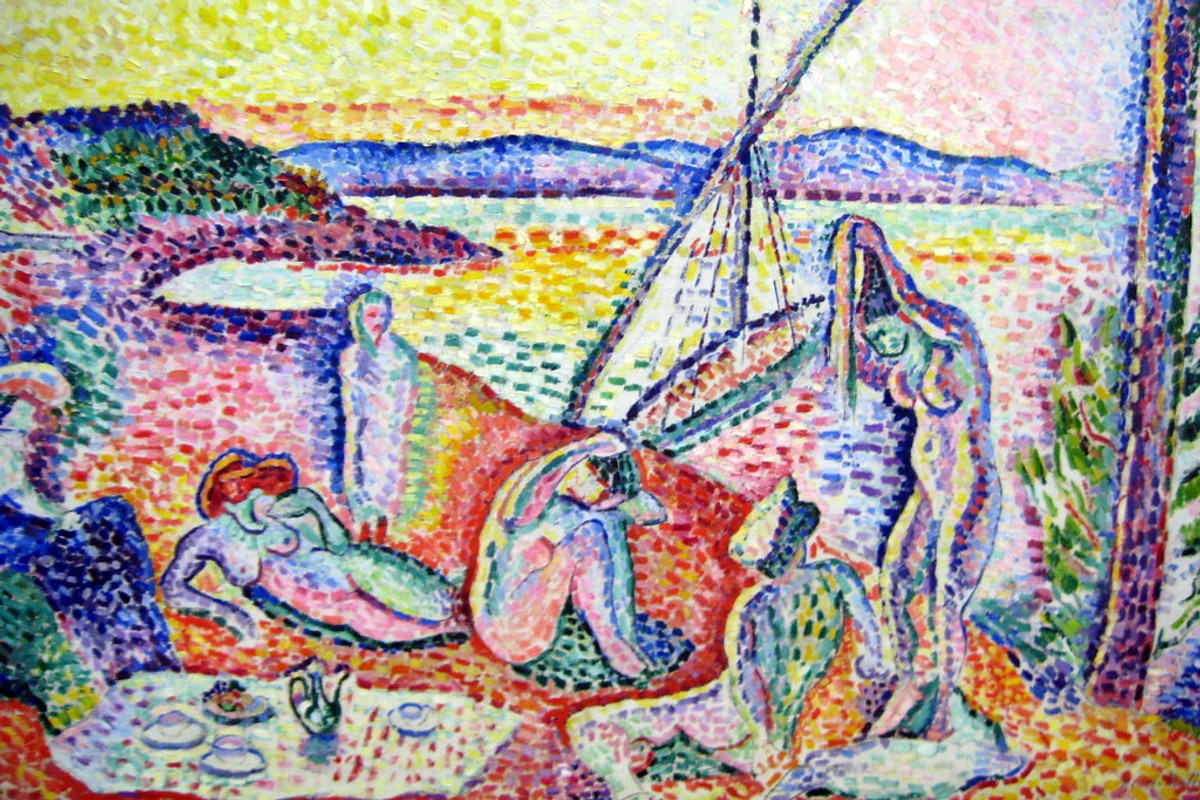

- Baroque and Romanticism: Artists drew heavily on classical mythology and allegory. Think of Justice, often depicted blindfolded with scales, or the personification of Liberty leading the people. Themes like the fleetingness of life (vanitas symbols like skulls, wilting flowers, or hourglasses) were common reminders of mortality. A painting like Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa became a powerful political allegory, using the suffering of shipwrecked sailors to comment on government failure.

, licence

- A Specific Example: Vanitas Still Life: Let's look closer at a vanitas painting. These still lifes, popular in the 17th century, are packed with symbols reminding the viewer of the transience of life, the futility of worldly possessions, and the certainty of death. Common symbols include: a skull (death), wilting flowers or decaying fruit (decay, fleeting beauty), an hourglass or clock (passage of time), extinguished candle (loss of life), bubbles (brevity of life), musical instruments or books (fleeting pleasures or knowledge), and sometimes coins or jewels (vanity of wealth). These paintings weren't just pretty arrangements of objects; they were visual sermons, using a shared symbolic language to encourage contemplation on mortality and the spiritual life. It's a powerful example of how everyday objects can be imbued with deep, moralizing meaning.

- Modern and Contemporary: The use of symbols becomes more varied, personal, and conceptual. While overt religious or mythological symbols might be less common, artists still use color, form, and objects to evoke ideas and emotions. Think of the emotional weight of color in a Mark Rothko painting, where abstract fields of color aim to evoke profound emotional or spiritual responses. Or the found objects in assemblage art, where everyday items are imbued with new symbolic meaning through their combination and context. Pop Art, for instance, turned consumer goods like Andy Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans into symbols of mass culture and consumerism. Conceptual artists use symbols to represent abstract ideas or critique systems. Performance art often uses symbolic actions or objects to communicate complex social or political messages. Even digital art can employ symbols, drawing on internet culture, emojis, or code itself as symbolic language. The use of symbols continues, even if the language becomes more personal, conceptual, or even fleeting. It's a tradition that keeps reinventing itself, sometimes in ways that might make you scratch your head, but that's part of the fun! You can see this evolution in museums like the MoMA in NYC or the Tate Modern in London. Western art shows us how symbolism can shift from explicit religious/moral narratives to personal and conceptual explorations.

Indigenous Australian Art: Storytelling, Land, and Ancestral Beings

Moving from the structured narratives of Western art, let's journey back to the vast landscapes of Australia, where symbols tell a different kind of story, deeply rooted in the earth itself and the spiritual realm. Indigenous Australian art, particularly the dot paintings from the Central Desert, is a profound example of symbolic language. These intricate patterns aren't just abstract designs; they are maps, stories, and records of the Dreamtime (the creation period and the spiritual realm). The Dreamtime isn't a linear historical period but an eternal present, encompassing the creation of the world by ancestral beings and the laws and customs that govern life. Symbols like concentric circles (representing waterholes, campsites, or fruit), straight lines (pathways or rivers), and animal tracks are used to depict the landscape, the journeys of ancestral beings, and important cultural knowledge. The use of dots often serves to obscure sacred information from those not initiated, adding another layer of meaning and protection. Symbols might also represent specific plants used for food or medicine, or the tracks of animals important for hunting.

Artists like Emily Kame Kngwarreye, while often seen as abstract, drew deeply from these traditional symbolic languages. Her swirling lines and fields of color can be seen as mapping the energy flows and topography of her country, embodying the ancestral stories rather than literally illustrating them. This connection between abstract form and deep, symbolic narrative is something that resonates strongly with me as an artist exploring abstraction. It shows how non-representational art can still be profoundly meaningful and rooted in a rich visual language. You can see some examples of my own abstract work if you buy art from me, and perhaps you'll find echoes of this idea of conveying feeling and place through form and color. Indigenous Australian art teaches us how abstract symbols can be deeply connected to land, history, and spirituality.

![]()

Other Rich Symbolic Systems

While we've explored some major examples, countless other cultures have developed rich symbolic languages in their art. Think of the intricate Celtic knotwork, with its endless loops symbolizing eternity, interconnectedness, and the spiritual world. Or the powerful Norse runes, which were not just an alphabet but symbols believed to hold magical and divinatory meanings, often carved into objects or stones. Native American art traditions also feature diverse and powerful symbolic systems, often tied to nature, spirits, and tribal identity, seen in pottery, textiles, totem poles, and paintings. These systems, like many others around the world, demonstrate the universal human drive to imbrue forms with meaning, creating visual languages that bind communities and connect them to their history and beliefs.

Symbols in Contemporary Culture

Moving beyond traditional art forms, symbols are just as prevalent and powerful in contemporary visual culture. Think about the ubiquitous nature of logos – they are symbols designed to instantly evoke brand identity, values, and associations, often carrying significant cultural weight (and sometimes becoming targets for critique or parody). Emojis are a rapidly evolving symbolic language, condensing complex emotions or ideas into simple icons. Memes often rely on shared visual or textual symbols to communicate humor, social commentary, or cultural references. Even the design of user interfaces and digital icons uses symbolic language to guide interaction. Political symbols, from flags and emblems to protest signs and street art, continue to be potent tools for communication and identity in the modern world. This shows that the human need for symbolic communication is alive and well, constantly adapting to new technologies and social contexts. It's a reminder that the silent language is still being written, all around us.

Do Symbols Speak the Same Language Everywhere? The Evolution of Meaning

One of the most fascinating things about symbols is that their meanings aren't fixed. They can evolve, change, or even be completely reinterpreted over time and across different contexts. But if symbols are a language, is it a dead language, or one that's constantly changing? Rarely are symbols truly universal. While some symbols might have similar meanings across a few cultures (like water often representing life or change), most are culturally specific. A symbol that's positive in one place could be negative in another. It's a good reminder not to assume anything when looking at art from a different background! So, how universal are symbols, really? Not very, it turns out. And that's what makes them so endlessly complex and interesting.

Consider the color blue. In some Western traditions, it symbolizes sadness or melancholy (hence 'feeling blue'). In Christianity, it can represent the Virgin Mary and purity. In ancient Egypt, blue (specifically lapis lazuli) was associated with the heavens and the gods. In China, it can symbolize immortality. In Korea, it's associated with mourning. In some Middle Eastern cultures, blue is seen as protective, warding off the evil eye. The same color, vastly different meanings depending on where you are and when. It's a powerful illustration of how deeply symbolism is tied to cultural context. You can dive deeper into this in my article on how artists use color.

Another striking example is the color white. In many Western cultures, white symbolizes purity, innocence, weddings, and new beginnings. It's the color of a bride's dress or a christening gown. However, in many East Asian cultures, white is traditionally associated with mourning, funerals, and death. It's the color worn at funerals as a symbol of grief and respect for the deceased. Imagine the profound cultural clash if someone unaware of this difference attended a wedding in one culture dressed for a funeral in another! This stark contrast underscores the importance of cultural literacy when interpreting symbols.

Another example is the serpent or snake. In Western Christian tradition, it's often associated with temptation and evil (the serpent in the Garden of Eden). However, in many ancient cultures (like Egypt, Greece, and Mesoamerica) and still in some modern contexts, it symbolizes healing, transformation, rebirth, or wisdom (think of the Rod of Asclepius, the symbol of medicine). Its ability to shed its skin makes it a potent metaphor for renewal. This duality highlights how a symbol's meaning can flip entirely depending on the cultural lens.

Symbols can also change meaning within the same culture over time. The meaning of a national flag might shift depending on the political climate or historical events. A symbol used by a counter-culture movement might eventually be adopted and commercialized by the mainstream, altering its original rebellious meaning. Even technological symbols, like emojis, evolve rapidly in their usage and interpretation within digital culture. This constant flux is what keeps the language of symbols alive and relevant.

Interpreting symbols, especially from cultures or time periods vastly different from our own, requires humility and a willingness to learn. We can't just assume our own cultural baggage applies. It's a reminder that art is a conversation, and sometimes, we need a translator.

Here's a quick look at how some common symbols vary:

Symbol | Western Meaning (Examples) | Egyptian Meaning (Examples) | Indian Meaning (Examples) | East Asian Meaning (Examples) | Other Meaning (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circle | Wholeness, Eternity, Unity | Sun Disk (Ra), Eternity | Mandala (Universe), Chakra | Harmony, Perfection, Void | Celtic: Eternity |

| Red | Love, Passion, Danger | Chaos, Power | Purity, Fertility, Marriage | Good Fortune, Happiness, Luck | |

| Blue | Sadness, Purity (Mary) | Heavens, Nile, Gods | Krishna, Divinity | Immortality, Mourning (Korea) | Middle East: Protection |

| Serpent | Evil, Temptation | Protection, Royalty, Magic | Kundalini, Rebirth, Power | Good Fortune, Wisdom, Power | Medicine: Healing |

| White | Purity, Innocence, Wedding | Joy, Sacredness | Purity, Widowhood | Mourning, Death |

The Artist's Relationship with Symbols

As an artist, my relationship with symbols is a complex one. Sometimes I consciously draw on established symbols, perhaps playing with their traditional meanings or placing them in new contexts. Other times, symbols emerge more intuitively from my process, from the shapes and colors themselves. I might start with an abstract idea or emotion, and a certain form or color combination just feels right, carrying a weight that resonates with something deeper. It's a bit like dreaming visually. It's less about a dictionary definition and more about an emotional or spiritual resonance. I remember working on a piece once, just letting the paint flow, and a particular cluster of shapes emerged that reminded me of ancient script, even though I wasn't consciously thinking of it. It felt like the painting was whispering its own story, a quiet, unexpected symbol appearing on the canvas.

Invented and Personal Symbols

Beyond drawing on established cultural or universal symbols, artists also create their own symbolic languages. This is particularly true in modern and contemporary art, where personal expression is highly valued. An artist might develop a recurring motif – a specific shape, object, or figure – that holds deep personal meaning, perhaps related to their history, experiences, or inner world. These symbols might not be immediately recognizable to a viewer, requiring context from the artist's statement or body of work to understand. Think of Frida Kahlo's use of specific animals or objects in her self-portraits, which are deeply personal symbols of her pain, identity, and Mexican heritage. Or the recurring motifs in my own abstract work; a certain combination of lines and colors might symbolize the feeling of wind over a landscape, or the quiet energy of a still moment, meanings that are personal but which I hope resonate on an emotional level with the viewer. Creating these personal symbols is like building your own visual vocabulary, adding new 'words' to the silent language of art.

Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

Some might say these intuitive forms tap into universal archetypes, deep psychological patterns that resonate across human experience, as proposed by thinkers like Carl Jung. These might include figures like the Great Mother, the Hero, the Trickster, or fundamental shapes like the circle or the cross. Jung believed these archetypes were part of a collective unconscious, influencing myths, dreams, and creative expression across cultures. While the specific cultural lens through which these archetypes are interpreted is key, the idea that certain forms or figures hold a deep, shared resonance across humanity is fascinating. For example, the archetype of the 'journey' might be symbolized by a spiral in prehistoric art, a winding river in East Asian painting, or a road in a contemporary landscape. My own abstract work often feels like an exploration of these underlying forms and energies, trying to capture something universally felt through a personal, visual language. It's a less explicit form of symbolism, perhaps, but no less powerful. It's about tapping into that shared visual vocabulary that exists beneath conscious thought.

Abstract art, in particular, often works on a symbolic or emotional level rather than a purely representational one. A bold red stroke might symbolize passion or anger, not just be 'red paint'. A swirling form could represent chaos or energy. When I'm creating, I'm not always thinking, "This shape means X." It's more about building a visual language that evokes feeling and thought, hoping that the viewer might find their own connections, perhaps tapping into universal archetypes or personal associations. You can see this exploration in my own abstract art – it's less about depicting objects and more about conveying energy, emotion, and form through color and shape. It's a constant dance between intention and intuition, trying to capture the unseen through the seen.

The Artist's Responsibility

Working with symbols, especially those from cultures different from your own, comes with a responsibility. It's crucial to approach such symbols with respect and a willingness to learn their original context and meaning. Simply borrowing a symbol for aesthetic purposes without understanding its depth can be seen as appropriation, stripping it of its cultural significance. Instead, artists can engage in appreciation – learning about the symbol, understanding its history, and perhaps using it in a way that acknowledges its origins or creates a dialogue with its traditional meaning. It's a delicate balance, requiring sensitivity and research, but it leads to richer, more meaningful work.

Consider an artist like Ai Weiwei. He frequently uses traditional Chinese materials and symbols – porcelain, wood from dismantled temples, bicycles – but places them in contemporary contexts to critique political systems, explore history, and comment on global issues. His use of these symbols is not merely decorative; it's deeply embedded in his message and cultural identity, creating powerful, layered works that resonate globally precisely because they engage with specific, yet universally understandable, themes of power, history, and individual experience. You can learn more about his work in my ultimate guide to Ai Weiwei.

Looking for Symbols in Art Today: Your Decoder Ring

So, the next time you're looking at a piece of art, whether it's in a grand museum like the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam or a small local gallery, take a moment to look beyond the surface. It might feel daunting at first, like learning a new language, but the more you look, the easier it gets. It's a rewarding practice. Think of yourself as a detective, looking for clues.

Here are some ways to start deciphering the silent language:

- Observe Recurring Elements: Are there any objects, animals, plants, or shapes that appear multiple times within a single artwork or across an artist's body of work? Repetition often signals significance.

- Consider Color: What colors are used, and what might they signify in the context of the artwork or the artist's culture? (You might find my thoughts on how artists use color helpful here). Remember, color symbolism is highly cultural!

- Look at Gestures and Postures: Especially in figurative art, hand gestures (mudras in Indian art, for example) or body postures can carry specific symbolic meanings. (Sometimes even body language in portrait art can be symbolic). Pay attention to how figures hold themselves or interact.

- Analyze Composition: Does the overall arrangement of elements suggest something beyond the literal? Is there a hierarchy, a sense of movement, or a particular balance? (Understanding art composition can offer clues). How does the artist guide your eye through the work?

- Tune into Your Feelings: What does the artwork feel like? Sometimes the emotional response is the key to unlocking symbolic meaning, even if you can't name the specific symbols. Your personal connection is valid and important.

- Research the Context: This is often the most crucial step. Look at the artwork's title, the artist's background, the time period, and the culture it comes from. Researching the artist's specific intent, if possible through interviews or statements, can also provide valuable insights into their personal symbol systems. Museum labels, exhibition catalogs, and online resources can provide invaluable information about intended symbolism or common interpretations within that context. Don't be afraid to do a little digging! Understanding the 'grammar' of a culture's visual language makes all the difference.

It's not about finding a single 'right' answer. Symbolism is often open to interpretation, and your own background and experiences will shape what you see. But by being aware that a silent language exists, you can open yourself up to a richer, deeper engagement with the artwork and the cultures that created it. It's a journey of discovery, one that continues every time I step into my studio or visit a gallery.

Conclusion

Symbols in art are far more than mere decoration; they are potent carriers of culture, history, belief, and emotion. From the earliest marks of prehistoric humans to the complex visual languages of ancient empires and the evolving signs of contemporary art, artists have used this silent language to communicate complex ideas, preserve traditions, and connect with viewers on a profound level. Understanding cultural symbolism unlocks new layers of meaning, transforming the act of looking at art into an an active conversation across time and space. For me, personally, delving into this world has not only enriched my appreciation for art history but has also profoundly influenced my own creative process, encouraging me to think about the deeper resonances of form and color in my abstract work. When you look at my abstract art, perhaps you'll see not just shapes and colors, but echoes of these ancient visual conversations, or tap into the intuitive symbols that emerge from my own journey. It reminds us that while visual forms might differ wildly across the globe, the human impulse to imbrue objects and images with deeper significance is a universal thread, connecting us all through the powerful, evolving language of art. It's a language worth learning, one brushstroke, one symbol at a time, unlocking those hidden doors to deeper understanding and a richer appreciation of the world's visual tapestry. Happy deciphering!