Modern Art Time Period: An Artist's Personal Guide to the Revolution (1860s-1970s)

Explore the modern art period (1860s-1970s) through an artist's eyes. Dive into Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, Pop Art, Minimalism, and more, understanding the revolution that shaped art today. Discover key movements, artists (including often overlooked voices), social context, challenges, and the enduring legacy of this transformative era, including its impact on the art market and design.

The Modern Art Time Period: A Personal Journey Through Revolution (1860s-1970s)EventListeners

Okay, let's talk about modern art. Not the stuff happening right now (that's contemporary, and we can dive into that another time, maybe starting with When Did Contemporary Art Start? The (Gloriously Fuzzy) Artist's Guide). I mean the period that kicked off a whole new way of seeing and making art, roughly from the 1860s through the 1970s. It's a massive chunk of time, packed with more 'isms' than you can shake a paintbrush at, and honestly, it changed everything. It's like art history's rebellious teenager phase – loud, experimental, and utterly transformative. Trying to wrap your head around it all can feel a bit like trying to paint the entire sky with one brushstroke – impossible and probably a bit messy. But that's part of the fun, isn't it? For me, this era feels less like a historical chapter and more like the moment art finally gave itself permission to breathe, to be messy, to be real. That permission slip to be yourself that I mentioned earlier? It was forged in this era.

For me, as an artist, understanding this era isn't just about memorizing dates and names. It's about tracing the lineage of ideas, seeing how artists started breaking the rules, and finding the roots of the freedom I feel in my own studio today. It's a revolution, and like any good revolution, it was messy, exciting, and full of passionate people daring to see the world differently. It's where the idea that art could be a direct expression of your inner world, your feelings, your self, really took hold. That's a powerful legacy.

What Exactly Is the Modern Art Period?

Think of it as a grand departure from tradition. Before this, art often aimed for realistic representation, historical narratives, or religious themes, often commissioned by wealthy patrons or institutions like the powerful Salons and Academies. There were rules, traditions, and a certain way things were 'supposed' to be done. Artists were trained in specific techniques and expected to adhere to established standards of beauty and subject matter. (You can get a sense of the long road we traveled in The History of Art: An Artist's Personal Journey Through Time).

Modern art said, "Nah, I'm good." Or maybe more like, "Hold my turpentine." Artists started questioning everything. What is art for? Who is it for? What can it look like? They experimented with new materials, techniques, and most importantly, new ways of seeing and interpreting the world. The rapid pace of industrialization and urbanization transformed daily life, presenting artists with new subjects like the dynamism of the city and a sense of a world in constant flux. Think of the bustling streets and smoky factories that appeared in paintings. The changing role of patrons, with artists increasingly working for a broader market or pursuing their own vision, also fueled this independence, freeing them from traditional constraints. The invention of photography, for instance, freed artists from the need to be human cameras, allowing them to explore subjective experience, emotion, and form in ways realism couldn't capture. Photography also influenced composition, sometimes leading artists to crop scenes in unexpected ways, much like a camera lens, or even capturing the blur of motion that the human eye doesn't always register. This shift wasn't just about what they painted, but how and why. It was about finding new visual languages to express a rapidly changing world.

Beyond depicting the visible world, modern artists embraced new subjects: the speed of technology, the complexities of the human psyche (hello, Freud!), and purely abstract ideas and emotions. They were also influenced by major intellectual shifts of the era, like Einstein's theories challenging fixed perspectives or Nietzsche's philosophy questioning traditional values, which seeped into the artistic mindset, encouraging radical new ways of seeing and thinking. Scientific discoveries, particularly in color theory, also directly impacted movements like Impressionism and Pointillism, leading artists to experiment with how colors interact on the canvas and in the viewer's eye. And let's not forget the profound impact of global events like World War I and World War II, which shook the foundations of society and led artists to question everything, fueling movements like Dada and Surrealism that grappled with absurdity and the subconscious.

It wasn't a single, unified style. Far from it! It was a cascade of movements, each reacting to or building upon the last. These movements often ended in "-ism" because they represented a distinct doctrine, theory, or practice adopted by a group of artists. While these 'isms' help categorize, remember that artists often blurred lines or moved between styles. It was about individual expression, subjective experience, and a fascination with the modern world – its speed, its cities, its psychology, and the seismic shifts brought about by industrialization and global conflict.

The Big Players: A Cascade of Movements (1860s - 1970s)

Ready to dive into the whirlwind? Trying to cover every single movement in this period would be like trying to paint the entire sky with one brushstroke – impossible and probably a bit messy. But let's hit some of the major ones that really shaped the landscape, roughly in chronological order, to see how one idea sparked the next. Remember, these dates are fuzzy, and many movements overlapped and influenced each other simultaneously.

Symbolism (c. 1880s-1900s)

Emerging in the late 19th century, Symbolism was a precursor to many later modern movements, reacting against Realism and Impressionism. Instead of depicting the external world, Symbolists sought to express inner truths, emotions, and mystical ideas through symbolic imagery and evocative forms. It was less about what you saw and more about what you felt or intuited. It's like stepping into a dream or a poem, where meaning is hinted at rather than stated directly. This focus on the inner world was a crucial step towards abstraction and subjective expression. (Understanding Symbolism: An Artist's Expanded Guide to Deeper Meaning)

- Key Artists: Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Gustav Klimt, Edvard Munch (also Expressionist).

- Key Characteristics: Focus on subjective experience, dreams, myths, and the spiritual; use of symbolic imagery; often melancholic or mysterious mood; rejection of objective representation.

- Influence: Paved the way for Expressionism and Surrealism by prioritizing inner reality and symbolic language over external appearance.

Symbolism's turn inward set the stage for art that wasn't just about the visible, but the felt.

Impressionism (c. 1860s-1880s)

Often seen as the gateway drug to modern art. These artists (Impressionism: An Artist's Guide to Light, Moment & Revolution) were obsessed with capturing the fleeting moment, the effect of light, and everyday subjects. Think visible brushstrokes, vibrant colors, and a sense of spontaneity. Claude Monet's "Impression, soleil levant" (Impression, Sunrise) even gave the movement its name. They were the rebels who got the ball rolling, taking their easels outdoors and capturing life as it happened. Standing in front of a Monet, I often feel like I're right there in that moment, feeling the breeze and seeing the light dance. It's a reminder that even the most ordinary scene can be extraordinary if you just look closely enough.

![]()

- Key Artists: Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt. Also notable sculptors like Auguste Rodin, whose expressive, less idealized forms broke from academic tradition around the same time.

- Key Characteristics: Focus on light and its changing qualities; visible, loose brushstrokes; open composition; emphasis on everyday subject matter like landscapes, city life, and portraits.

- Influence: Broke from academic tradition, paved the way for greater artistic freedom and subjective interpretation. Their focus on perception and light directly influenced the next wave. They were also influenced by Japanese prints (Japonisme), which offered new perspectives on composition and color.

Impressionism's focus on subjective perception and visible brushwork opened the door for artists to push further.

Post-Impressionism (c. 1880s-1900s)

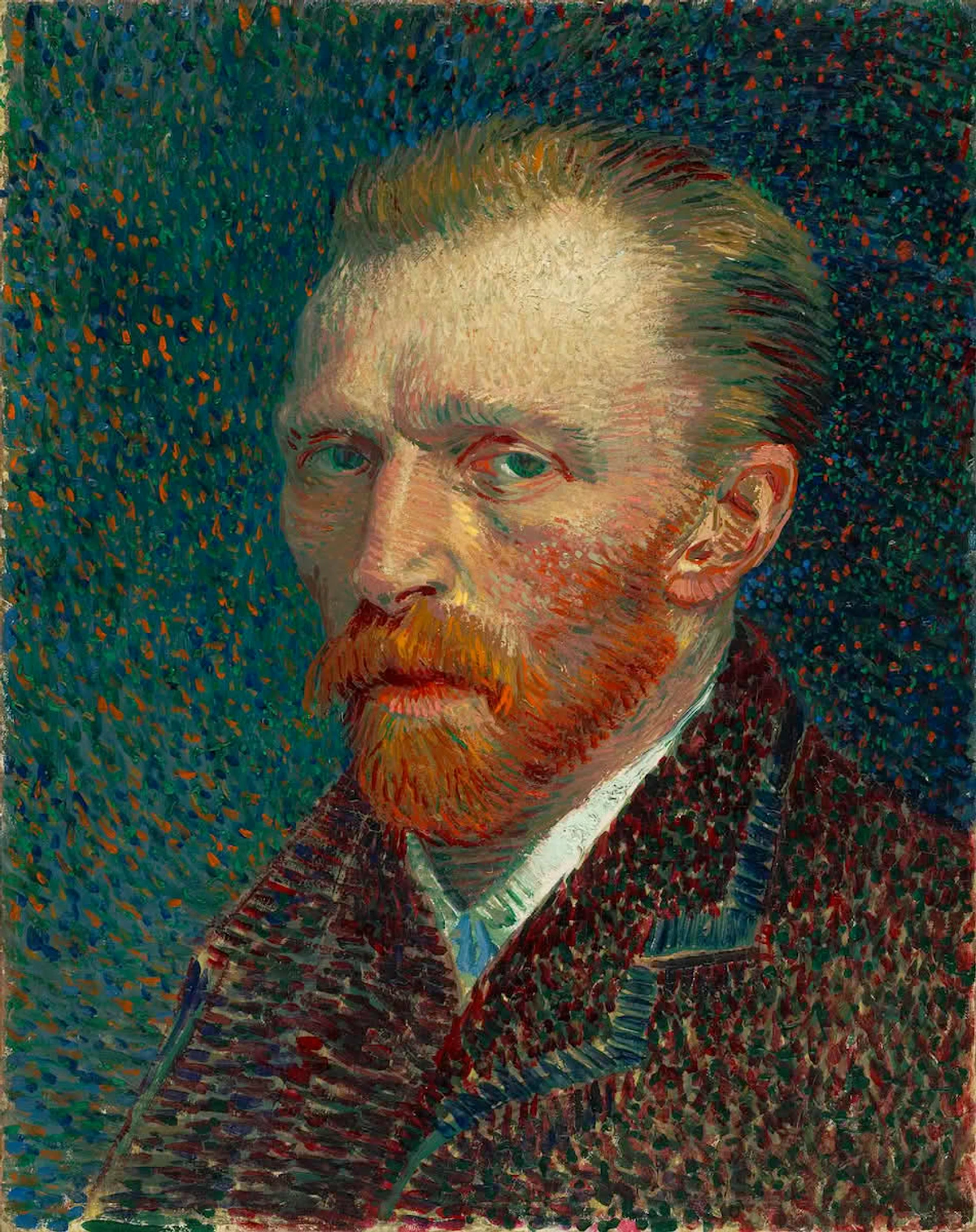

A reaction to Impressionism, but pushing its ideas further. Artists felt Impressionism lacked structure and emotional depth. Post-Impressionists used color and form not just to depict reality, but to express emotion or build structure. This era is incredibly diverse, laying groundwork for later abstraction. It's where things start getting really interesting and diverse, as artists like Paul Cézanne broke down forms into geometric shapes, paving the way for Cubism, while Vincent van Gogh (Vincent van Gogh: An Artist's Extended Guide to His Life, Art & Legacy) used swirling brushstrokes and intense color to convey raw emotion in works like "The Starry Night." Georges Seurat took a more scientific approach with Pointillism, using tiny dots of pure color (Pointillism: Ultimate Guide to the Art Movement, Technique & Legacy). Like the Impressionists, they also found inspiration in Japanese prints, particularly their flat areas of color and strong outlines.

- Key Artists: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat. Key works include Cézanne's Mont Sainte-Victoire series, Van Gogh's The Starry Night, Gauguin's Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, and Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

- Key Characteristics: Continued use of vibrant color, but with more emphasis on form, structure, and emotional expression. Techniques varied widely (e.g., Cézanne's geometric breakdown, Van Gogh's expressive brushwork, Seurat's Pointillism using tiny dots of color). Exploration of symbolic or emotional use of color.

- Influence: Directly influenced Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism by exploring the expressive potential of color and the structural possibilities of form. Cézanne's approach was particularly foundational for Cubism.

The Post-Impressionists showed that color and form could do more than just describe; they could express and structure, leading directly to the next explosion of color.

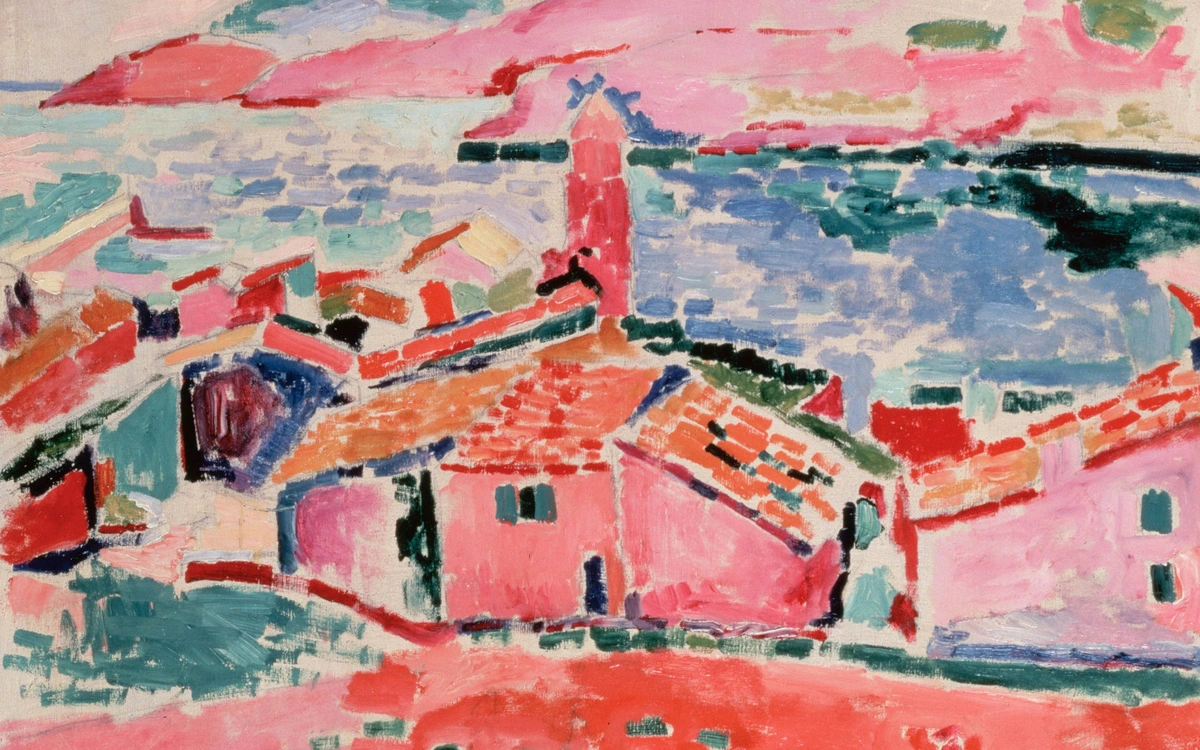

Fauvism (c. 1905-1908)

Short-lived but explosive! Fauvists (Ultimate Guide to Fauvism: The Art Movement of Wild Color & Intense Emotion) like Henri Matisse (Henri Matisse: The Ultimate Guide to the Master of Color and Joy) and André Derain used incredibly vibrant, non-naturalistic colors straight from the tube. They were called 'wild beasts' (fauves) because their use of color was so radical. Matisse's "Woman with a Hat" is a famous example, where a portrait is less about likeness and more about the sheer joy and energy of color. Derain's paintings of London bridges or harbors are riots of unexpected hues. It's pure, unadulterated visual joy (or sometimes, intense emotion). This fearless approach to color is something I constantly think about when mixing paints in my own studio (The Secret Language of Color: An Artist's Guide to How Pigment Speaks). It's like they just threw the rulebook out the window and decided color should just feel right.

- Key Artists: Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck. Key works include Matisse's Woman with a Hat and The Joy of Life, and Derain's The Pool of London.

- Key Characteristics: Intense, non-naturalistic color used for emotional effect rather than description; simplified forms; visible brushstrokes; subjects often included landscapes and portraits.

- Influence: Directly impacted Expressionism and the broader use of color in modern art. Their liberation of color was a shockwave.

The Fauvists' wild color paved the way for art that prioritized feeling over seeing, leading to Expressionism.

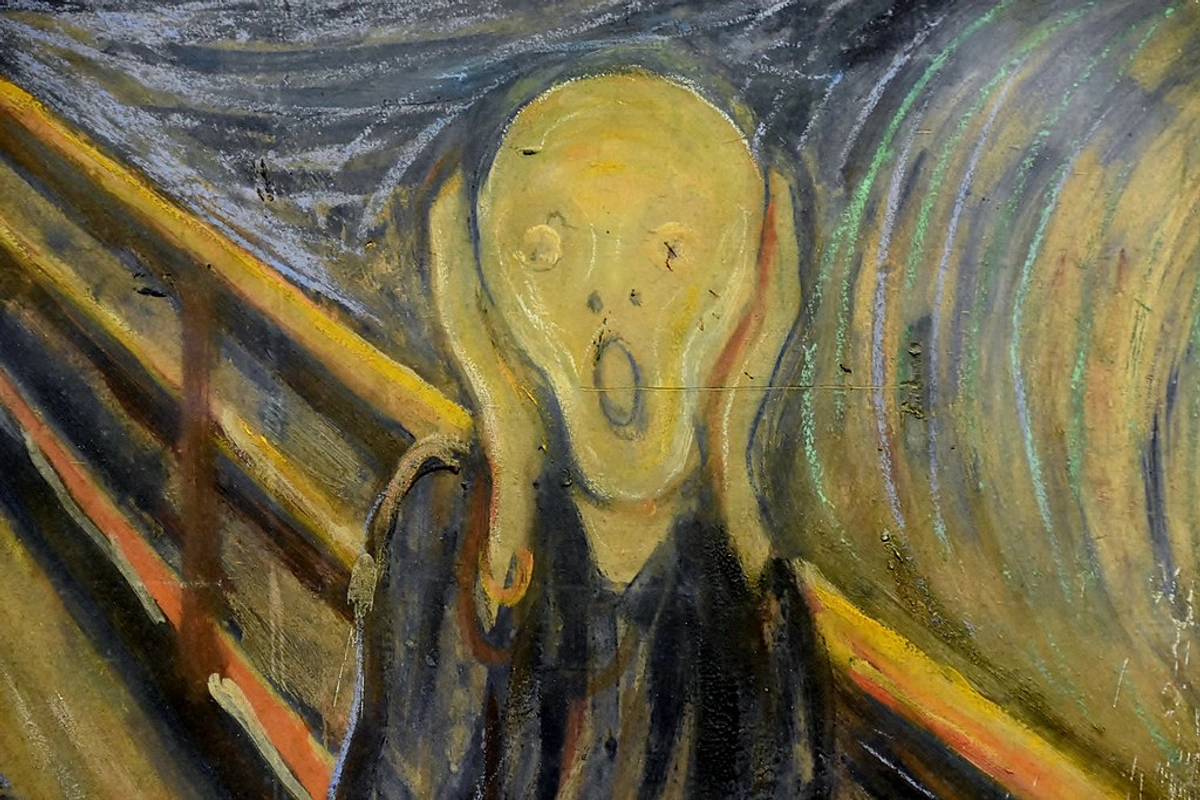

Expressionism (c. 1905-1920s)

Less about what the eye sees, more about what the soul feels. Emerging partly as a reaction to the perceived superficiality of Impressionism and the analytical nature of Cubism, Expressionists (Expressionism: Ultimate Guide to Art That Feels Deeply) sought to convey inner experience through distorted forms and intense colors. This movement often reflected the anxieties of the early 20th century, particularly around World War I and rapid social change. Munch's iconic "The Scream" is the quintessential example of this raw emotional intensity. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky explored the spiritual in art through color and form, moving towards abstraction. Franz Marc used color symbolically to depict animals and nature. Looking at an Expressionist piece can feel like being hit by a wave of pure emotion. It's art that doesn't just show you something; it makes you feel something, often something intense or unsettling, mirroring the turbulent times.

- Key Artists: Edvard Munch, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Egon Schiele. Key works include Munch's The Scream, Kandinsky's early Compositions and Improvisations, Marc's Blue Horse I and The Fate of the Animals, and Kirchner's Street, Berlin.

- Key Characteristics: Distortion of reality (figures, landscapes) to express subjective feelings; intense, often jarring colors; focus on emotional impact over aesthetic beauty; themes often included urban life, portraits, and psychological states.

- Influence: Paved the way for Abstract Expressionism and other movements prioritizing emotion and subjectivity. It solidified the idea that art could be a direct expression of the inner world.

Expressionism's deep dive into emotion and distortion happened concurrently with a radical rethinking of form and space in Cubism.

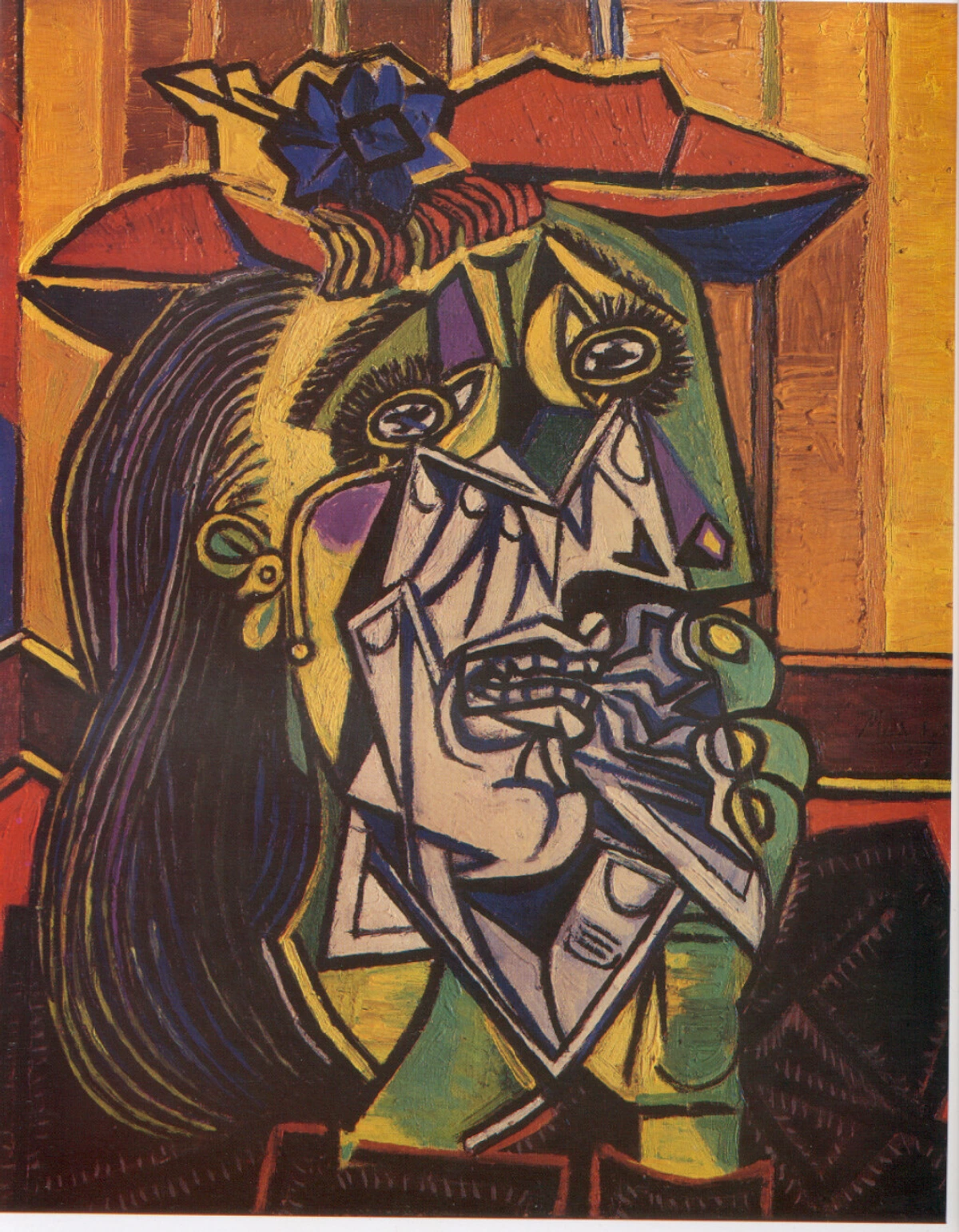

Cubism (c. 1907-1914)

Ready to see the world shattered and reassembled? Building on Cézanne's ideas about breaking down form, Pablo Picasso (Ultimate Guide to Picasso: His Life, Art Periods & Work) and Georges Braque shattered traditional perspective. They broke objects down into geometric forms and showed them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously (Cubism Art Explained: Your Personal Guide to Shattering Reality). This phase, Analytical Cubism, often used a limited, muted color palette (think browns, grays, blacks) to focus purely on form and structure, analyzing objects from all sides at once. Later, in Synthetic Cubism, they incorporated elements like collage and found materials, bringing in brighter colors and textures and building up forms from simpler shapes. Picasso's groundbreaking "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" is often cited as a precursor, showing fragmented figures influenced by African masks (a nod to the influence of non-Western art on modernism - How Non-Western Art Sparked the Modernist Revolution: An Artist's View). This influence wasn't just about copying; artists were drawn to the abstract qualities and expressive power of these forms, seeing them as a way to break free from Western naturalism. Key sculptors like Alexander Archipenko and Jacques Lipchitz also translated Cubist principles into three dimensions. It's like looking at something through a kaleidoscope that also happens to be a geometry textbook. Mind-bending and hugely influential, Cubism fundamentally changed how artists thought about space and form. As an artist, grappling with Cubism makes you question the very nature of representation – what happens when you show everything at once?

- Key Artists: Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger. Key works include Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and Guitar, Sheet Music, and Glass, Braque's Violin and Candlestick, and Gris's Portrait of Pablo Picasso.

- Key Characteristics: Objects are analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstracted form; multiple viewpoints are shown simultaneously; limited color palette (Analytical Cubism) or brighter colors and collage (Synthetic Cubism); subjects often included still lifes, portraits, and figures.

- Influence: Fundamentally changed how artists thought about space and form, directly influencing Futurism, Constructivism, and later abstract movements. It's hard to overstate Cubism's impact; it truly fractured traditional ways of seeing.

Cubism's dynamism and fragmentation directly inspired movements obsessed with speed and the modern world.

Futurism (c. 1909-1914)

Born in Italy, Futurism was obsessed with speed, technology, cars, airplanes, and the dynamism of the modern world. They rejected the past and glorified war and violence (which, looking back, is... problematic, to say the least). Influenced by Cubism's fragmentation, they sought to capture movement and energy on canvas. Imagine trying to paint the feeling of driving a race car or flying a plane – that's what they were after. Artists like Umberto Boccioni attempted to show objects in motion and the interaction between objects and their environment. It was loud, aggressive, and short-lived as a major painting movement, but its energy echoed. It's like they wanted to bottle the feeling of the 20th century and splash it onto a canvas.

![]()

- Key Artists: Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (writer), Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Giacomo Balla. Key works include Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (sculpture) and Dynamism of a Cyclist, and Balla's Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash.

- Key Characteristics: Depiction of speed, motion, and dynamism; fragmentation of form (influenced by Cubism); celebration of technology, industry, and the city; subjects often included trains, cars, dancers, and urban crowds.

- Influence: Impacted Art Deco, Constructivism, and later movements interested in technology and speed. Their embrace of the machine age was a distinctly modern stance.

Meanwhile, in Russia, artists were also pushing abstraction, but with different goals.

Suprematism (c. 1915-1920s)

Founded by Kazimir Malevich in Russia, Suprematism aimed for the "supremacy of pure artistic feeling" over the depiction of objects. It was one of the earliest and most radical movements towards pure geometric abstraction. Malevich's iconic "Black Square" is perhaps the most famous (and sometimes baffling) example – a simple black square on a white background, intended to represent pure feeling, free from any object. It's art stripped down to its absolute basics – form and color, aiming for something universal and spiritual. It makes you think about what art needs to be. El Lissitzky also developed Suprematist ideas, applying them to graphic design and architecture. It's like they were trying to find the absolute zero of art, the point where it's just pure visual energy.

![]()

- Key Artists: Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky. Key works include Malevich's Black Square and Suprematist Composition: White on White.

- Key Characteristics: Pure geometric forms (squares, circles, lines) in a limited range of colors, often on a white background; focus on spiritual or pure feeling rather than representation; subjects were non-objective.

- Influence: Hugely influential on Constructivism and the development of abstract art globally. It was a bold declaration of art's independence from the material world.

Suprematism's focus on pure form and feeling led directly to a related movement focused on social purpose.

Constructivism (c. 1915-1930s)

Also emerging in Russia around the same time as Suprematism, Constructivism was more focused on using abstract art for social purposes, particularly after the 1917 Revolution. Artists like Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, and Lyubov Popova used geometric forms and industrial materials (metal, glass, wood) to create works that were functional or served propaganda. They saw art as a tool for building a new society, applying their principles to design, architecture, photography, and theatre. Think bold posters, dynamic sculptures, and designs for buildings or sets. It's art with a purpose, aiming to be part of everyday life and social change. Sculptors like Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner explored space and volume with transparent and industrial materials. It's like they took the abstract ideas of Suprematism and said, "Okay, how can we use this to actually build something?" The political upheaval of the Russian Revolution heavily influenced their belief that art should serve a collective, rather than purely individual, purpose.

- Key Artists: Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, Naum Gabo, Antoine Pevsner, Lyubov Popova. Key works include Tatlin's Monument to the Third International (model), Rodchenko's posters and photographs, and Gabo's Constructed Head No. 2.

- Key Characteristics: Geometric abstraction; use of industrial materials (metal, glass, wood); emphasis on construction and structure; often functional or socially oriented (posters, architecture, design).

- Influence: Profound impact on graphic design, architecture, theatre design, and abstract sculpture internationally. It showed art could be both abstract and deeply engaged with the world.

While Constructivism aimed to build a new world, Dada reacted to the collapse of the old one with chaos and absurdity.

Dada (c. 1916-1924)

Born out of the disillusionment and absurdity of World War I, Dada was anti-art, anti-logic, and anti-establishment. It was chaotic, nonsensical, and deliberately provocative. Dada artists felt that if the world could descend into such madness, then art should reflect that absurdity. It was less about aesthetics and more about questioning everything, using satire, collage, and performance to critique society. Artists like Marcel Duchamp challenged the very definition of art with his "readymades" (everyday objects presented as art, like his famous urinal, "Fountain"). Hannah Höch pioneered photomontage, using fragmented images to critique society and gender roles. It makes you wonder, "Is this art?" which, trust me, is exactly what they wanted you to ask. It's the ultimate artistic shrug in the face of chaos, a direct response to the senseless violence and destruction of the war.

![]()

- Key Artists: Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Höch, Kurt Schwitters, Jean Arp, Tristan Tzara. Key works include Duchamp's Fountain and L.H.O.O.Q., Höch's Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, and Schwitters' Merz collages.

- Key Characteristics: Anti-rationality, absurdity, protest against war and bourgeois society; use of readymades (everyday objects presented as art), collage, assemblage, performance; subjects were often nonsensical or satirical.

- Influence: Paved the way for Surrealism and future conceptual movements by prioritizing the idea over the finished object. Dada's questioning spirit is still felt today.

Dada's embrace of the irrational and the subconscious directly led to Surrealism.

Surrealism (c. 1920s-1950s)

Emerging from Dada's embrace of the irrational, Surrealism was heavily inspired by psychoanalysis and dreams (thanks, Freud!). Artists like Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, and Joan Miró explored the subconscious mind, creating bizarre, illogical worlds that felt deeply personal yet universally unsettling or intriguing. Techniques like automatic drawing (drawing without conscious thought) and frottage (rubbing a crayon over a textured surface) were used to tap into the unconscious. Dalí's melting clocks in "The Persistence of Memory" are instantly recognizable symbols of this dreamlike exploration. Magritte's juxtaposition of ordinary objects in unsettling ways (like a train coming out of a fireplace) makes you question reality. Frida Kahlo, though often categorized uniquely, also shared strong connections with Surrealism's exploration of inner reality, using symbolic imagery to delve into her personal pain, identity, and Mexican heritage. Sculptors like Alberto Giacometti created elongated, solitary figures that evoke existential feelings. It's the art equivalent of that weird dream you had last night, but painted with incredible technical skill. It makes you question reality, which I find fascinating. The aftermath of WWI and the rise of psychoanalysis provided fertile ground for this movement, as artists sought to escape the confines of logic and reason that seemed to have led the world to disaster.

- Key Artists: Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Joan Miró, Max Ernst, Frida Kahlo, Alberto Giacometti. Key works include Dalí's The Persistence of Memory, Magritte's The Treachery of Images ("Ceci n'est pas une pipe"), Miró's The Farm, and Kahlo's The Two Fridas.

- Key Characteristics: Exploration of the subconscious, dreams, and the irrational; juxtaposition of unrelated objects (like melting clocks or men raining from the sky); use of techniques like automatic drawing and collage; subjects often included dreamscapes, fantastical creatures, and distorted figures.

- Influence: Impacted literature, film, theatre, and later art movements interested in psychology and fantasy. Its visual language is still instantly recognizable.

While Surrealism explored the inner landscape, Bauhaus focused on shaping the outer one.

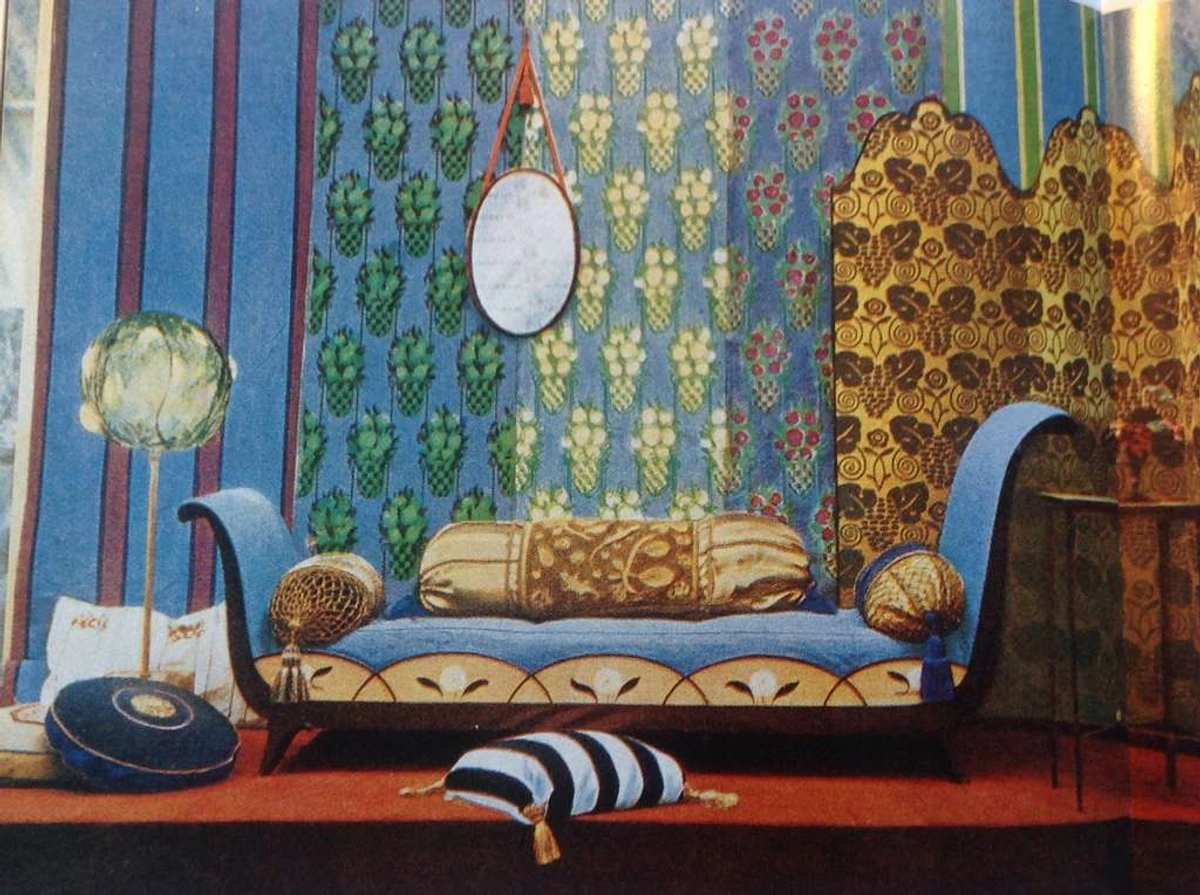

Bauhaus (c. 1919-1933)

More of a school and a philosophy than a single style, Bauhaus (Beyond the Icons: Unearthing Underappreciated Bauhaus Artists) aimed to unite art, craft, and technology. Founded in Germany by Walter Gropius, it emphasized functionality, clean lines, and mass production, seeking to rebuild society aesthetically after the war. It wasn't just about painting or sculpture; it was about designing everything from chairs to buildings, textiles, and typography. While short-lived due to political pressure and eventually closed by the Nazis, its influence on architecture, design (What is Design in Art? An Artist's Personal & Engaging Guide), and art education was immense and continues today. It showed that modern art wasn't just for galleries, but could be part of everyday life. Key figures like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky taught there, bringing their abstract painting theories into the curriculum, while Anni Albers revolutionized textile design and Marcel Breuer designed iconic furniture. It's like they took the revolutionary spirit of modern art and applied it to making your everyday life more beautiful and functional. Coming out of the devastation of WWI, there was a real desire to build a better future, and Bauhaus aimed to do that through design.

- Key Figures: Walter Gropius, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Anni Albers, Josef Albers, Marcel Breuer. Key works include Breuer's Wassily Chair and Albers' textile designs.

- Key Characteristics: Integration of art, craft, and technology; emphasis on functionality and simplicity; geometric forms; influence on architecture and design; subjects were often abstract or functional designs.

- Influence: Immense and lasting impact on modern architecture, industrial design, graphic design, and art education worldwide. Its principles of form follows function are everywhere.

Concurrent with Bauhaus, another movement in the Netherlands sought universal harmony through pure geometry.

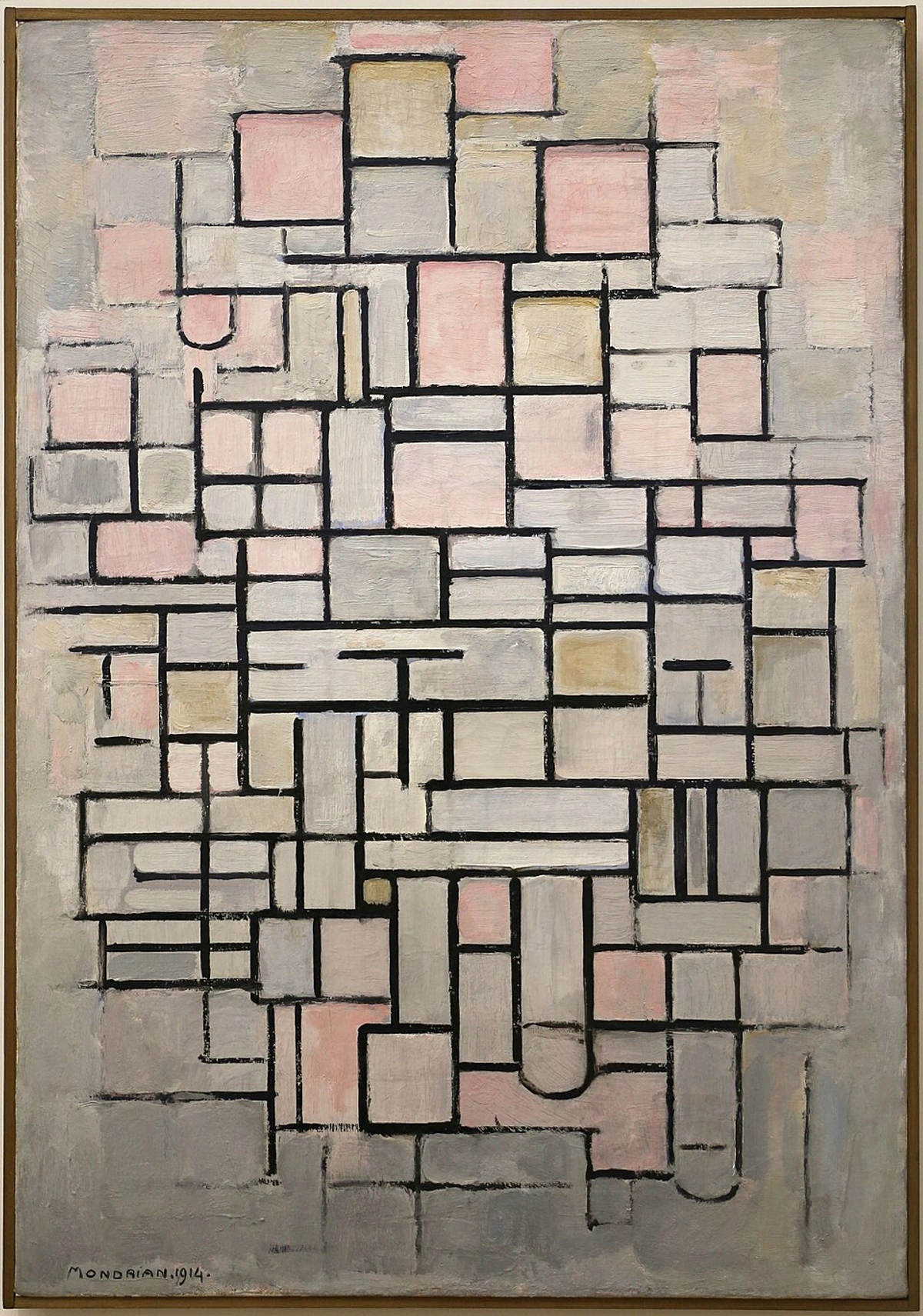

De Stijl (c. 1917-1931)

Dutch for "The Style," this movement, led by Piet Mondrian, sought pure abstraction using only horizontal and vertical lines and primary colors (red, blue, yellow) plus black, white, and gray. Mondrian's "Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow" is instantly recognizable. Theo van Doesburg was another central figure, though his ideas sometimes diverged from Mondrian's strict grid, incorporating diagonals. Gerrit Rietveld applied De Stijl principles to architecture and furniture, creating iconic pieces like the Red and Blue Chair. De Stijl aimed for universal harmony and order, a stark contrast to the chaos of the time. It's fascinating how reducing art to such basic elements could still feel so dynamic. It's like they believed that by finding the simplest, most universal visual language, they could create a sense of balance and order in a world that felt increasingly fragmented.

- Key Artists: Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Gerrit Rietveld. Key works include Mondrian's Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow and Rietveld's Schröder House and Red and Blue Chair.

- Key Characteristics: Pure geometric abstraction; use of only horizontal and vertical lines; limited palette of primary colors plus black, white, and gray; search for universal harmony and order; subjects were non-objective compositions.

- Influence: Significant impact on architecture, interior design, and graphic design. Its clean, geometric aesthetic is still influential today.

After the disruptions of WWII, the focus of the art world shifted dramatically, leading to a new kind of abstraction.

Abstract Expressionism (c. 1940s-1950s)

Post-WWII, the focus shifted to New York. Abstract Expressionists (Abstract Expressionism: Ultimate Guide to Art, Artists & Feeling) abandoned representation entirely, focusing on the act of painting itself (Action Painting, like Pollock's drip technique) or the emotional impact of color and form (Color Field Painting, like Rothko's glowing rectangles). This movement often reflected the post-war mood of both anxiety and possibility. Jackson Pollock's large-scale drip paintings emphasized the process and energy of creation. Mark Rothko (Mark Rothko: Ultimate Guide to His Immersive Color Field Art & Life) created vast canvases of shimmering color fields intended to evoke deep emotional or spiritual responses. Willem de Kooning explored dynamic forms, often returning to the figure in distorted ways. Helen Frankenthaler pioneered the soak-stain technique, letting color bleed into raw canvas. It's big, bold, and often feels like pure energy on canvas. Standing before a large Rothko can be an almost spiritual experience. It's like the artists were trying to process the trauma and uncertainty of the war through pure, unadulterated emotion on a massive scale.

- Key Artists: Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krasner. Key works include Pollock's Number 1A, 1948, Rothko's No. 14, 1960, and de Kooning's Woman I.

- Key Characteristics: Non-representational; emphasis on spontaneous gesture (Action Painting) or large fields of color (Color Field Painting); focus on expressing emotion and subjective experience; subjects were abstract forms and colors.

- Influence: Established New York as a major art center and profoundly influenced subsequent abstract movements. It was a powerful, often intense, expression of the post-war psyche.

Abstract Expressionism's intensity and perceived elitism led to a reaction that embraced the everyday.

Pop Art (c. 1950s-1960s)

A reaction against Abstract Expressionism's perceived seriousness and elitism. Pop artists turned to popular culture – advertising, comic books, everyday objects – for inspiration. They embraced mass production techniques like screen printing. Andy Warhol's "Campbell's Soup Cans" elevated the mundane to fine art, questioning notions of originality and mass culture. Roy Lichtenstein used comic strip panels and Ben-Day dots to create large-scale paintings. Claes Oldenburg created soft sculptures of everyday objects, playing with scale and material. Yayoi Kusama, while unique, is often associated with Pop Art due to her use of repetition, vibrant patterns (like dots), and engaging with popular culture and mass media through her installations and merchandise. It's witty, often ironic, and brought art crashing back down to earth (or maybe just into the supermarket aisle). It felt like a breath of fresh, slightly commercialized air after the intensity of Abstract Expressionism. It's like they looked at the world around them – the ads, the celebrities, the products – and said, "This is our reality now, let's paint this."

- Key Artists: Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Yayoi Kusama. Key works include Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans and Marilyn Diptych, Lichtenstein's Whaam!, and Oldenburg's Floor Burger.

- Key Characteristics: Use of imagery from popular culture, mass media, and advertising; often bold colors and graphic style; blurring the lines between fine art and popular culture; subjects included consumer goods, celebrities, and comic strips.

- Influence: Challenged traditional notions of subject matter and technique, influencing subsequent movements like Conceptualism and Postmodernism. It made art accessible and relatable in new ways.

Pop Art's focus on the object and mass culture paved the way for art that stripped away emotion and focused purely on form or idea.

Minimalism (c. 1960s-1970s)

Reacting against the expressive gestures of Abstract Expressionism and the subject matter of Pop Art, Minimalism sought extreme simplicity of form. Artists used industrial materials (like metal, plexiglass, and concrete) and geometric shapes, often arranged in series or grids. The focus was on the object itself, its materials, and its relationship to the space it occupied, rather than emotion or representation. Donald Judd created modular stacks and boxes. Frank Stella (Frank Stella: A Personal Guide to His Art, Paintings & Legacy) explored geometric patterns in painting. Agnes Martin created subtle, grid-based paintings. Dan Flavin used fluorescent light tubes to create installations. Carl Andre arranged industrial materials like bricks or metal plates directly on the floor. It's art that is exactly what it is, no more, no less. Standing near a minimalist sculpture, I often find myself thinking more about the space around it than the object itself – a strange and interesting shift. It's like the art is asking you to just be with it, without any narrative baggage. It stripped away the artist's hand and the emotional content, presenting the viewer with just the pure object and its presence.

- Key Artists: Donald Judd, Frank Stella, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre. Key works include Judd's Stacks, Stella's Black Paintings, and Andre's Equivalent VIII.

- Key Characteristics: Extreme simplicity of form; geometric shapes; industrial materials; emphasis on the object's physical presence and its relationship to the space; subjects were non-representational forms and structures.

- Influence: Influenced Conceptualism, Land Art, and later abstract sculpture. It pushed the boundaries of what could be considered art and how it should be experienced.

Minimalism's focus on the object and its context paved the way for art where the idea was paramount.

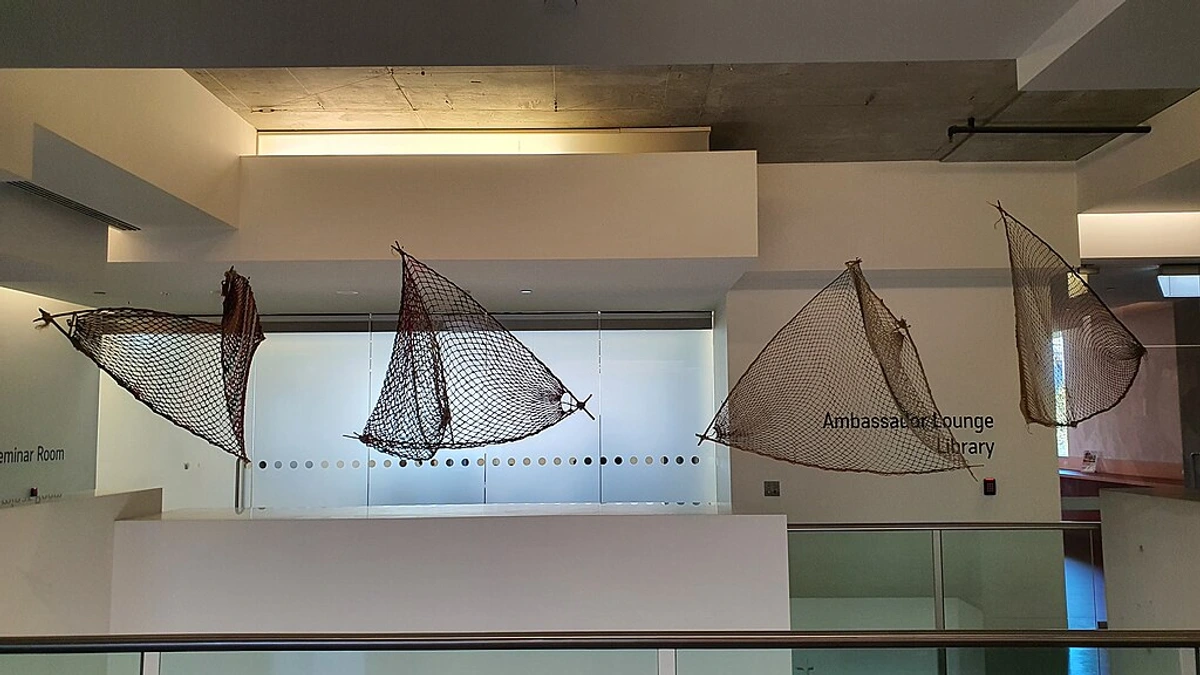

Conceptualism (c. 1960s-1970s)

Taking the Dada idea of prioritizing the concept even further, Conceptual art declared that the idea or concept behind the work was more important than the finished object itself. The physical manifestation might be minimal or even non-existent, existing as text, instructions, or documentation. It challenges the traditional notion of what art is and requires the viewer to engage intellectually. Joseph Kosuth's "One and Three Chairs" (a chair, a photograph of the chair, and a dictionary definition of "chair") is a classic example, exploring the relationship between object, image, and language. Sol LeWitt created wall drawings based on simple instructions. Lawrence Weiner's work often consists solely of text statements. Marina Abramović (Marina Abramović: Ultimate Guide to Her Performance Art, Life & Method) and Yoko Ono explored performance and ephemeral actions as art. It's art that makes you think, sometimes a lot, and I appreciate how it pushes those boundaries. It's less about looking and more about contemplating. It's like the artist is saying, "The real art is in your head, not just on the wall." This felt like a natural progression from Minimalism's focus on the non-object, pushing the idea to its logical conclusion.

- Key Artists: Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, Marina Abramović, Yoko Ono. Key works include Kosuth's One and Three Chairs and LeWitt's Wall Drawings.

- Key Characteristics: The idea is paramount; often uses text, instructions, or documentation; dematerialization of the art object; subjects are often philosophical questions or instructions.

- Influence: Profoundly influenced contemporary art, performance art, and installation art. It shifted the focus from the 'how' to the 'why'.

Finally, a movement focused purely on visual perception.

Op Art (Optical Art) (c. 1960s)

Focusing purely on visual effects, Op Art used abstract patterns and shapes, often in black and white or vibrant colors, to create illusions of movement, depth, or vibration. Artists aimed to stimulate the viewer's eye directly, exploring the nature of perception. While artists like M.C. Escher explored optical illusions earlier, Op Art specifically refers to the movement of the 1960s focused on abstract geometric patterns to create these effects. Bridget Riley's black and white paintings create dizzying effects, while Victor Vasarely used color and form to create illusions of three-dimensionality. It's art that plays tricks on your vision, making you question what you're seeing. It's a fascinating exploration of perception itself, a purely visual experience that bypasses narrative or emotion.

![]()

- Key Artists: Bridget Riley, Victor Vasarely. Key works include Riley's Movement in Squares and Vasarely's Vega-Nor.

- Key Characteristics: Abstract patterns and geometric shapes; creation of optical illusions of movement, flicker, or vibration; often black and white or high-contrast colors; subjects are non-representational visual effects.

- Influence: Influenced graphic design, fashion, and popular culture in the 1960s. It proved that pure visual sensation could be the subject of art.

Overarching Themes of Modern Art

Beyond the individual movements, several threads run through the entire modern art period, connecting these diverse styles:

- Move Towards Abstraction: A gradual shift away from representing the visible world towards exploring form, color, and line for their own sake (The History of Abstract Art: A Personal Journey & Expanded Guide). This wasn't a sudden leap, but a slow evolution driven by various factors.

- Subjectivity and Inner World: Prioritizing the artist's personal experience, emotions, and psychological state. Art became a vehicle for expressing internal realities, not just external ones.

- Experimentation and Innovation: A constant drive to break rules, use new materials and techniques (like collage, assemblage, industrial materials, photography, performance), and challenge established norms. This era was defined by its restless search for new ways to make and think about art.

- Critique of Modern Society: Often reflecting or reacting to the rapid changes, anxieties, and contradictions of industrialization, urbanization, global conflict (WWI, WWII, Cold War), and political upheaval. Art became a way to process and comment on the modern condition.

- Challenges and Controversies: Modern artists frequently faced rejection from traditional institutions, harsh criticism from the public and established critics, and even censorship, highlighting the truly revolutionary nature of their work. It wasn't an easy path!

- Changing Role of the Artist & the Art Market: Artists gained greater independence from traditional patrons, pursuing their own visions and engaging directly with a broader public and the emerging art market (galleries, dealers, critics, collectors). This shift fundamentally changed how art was made, shown, and valued (Understanding Art Prices: An Artist's Personal, Engaging Take on Value). The rise of the gallery system was crucial here.

- Influence of Non-Western Art: As mentioned with Cubism and Impressionism/Post-Impressionism (Japonisme), the influence of art from Africa, Asia, and Oceania was significant, providing new visual languages and challenging Western perspectives on representation (How Non-Western Art Sparked the Modernist Revolution: An Artist's View).

- Interdisciplinary Exploration: Modern artists often blurred the lines between painting, sculpture, architecture, design, theatre, and even early forms of performance art, seeking a 'total art' experience or applying artistic principles to everyday life (think Bauhaus, Constructivism). (What is Design in Art? An Artist's Personal & Engaging Guide)

These themes highlight the revolutionary spirit of the era and its lasting impact. For me, the theme of Experimentation and Innovation resonates most strongly. It's the permission to try new things, to fail, to push boundaries, that feels most vital to my own creative process.

Why Does This Period Still Matter?

So, why dedicate brain space to these movements and artists from decades ago? (Besides the fact that seeing it in person is amazing – check out Best Modern Art Museums: An Artist's Guide to Top Collections or Modern Art Galleries: Your Ultimate Guide to Visiting & Understanding). This era is foundational. It's not just history; it's the DNA of so much art being made today.

Here's why it resonates so deeply:

- It Broke the Mold: Modern art fundamentally changed the definition of what art could be. It wasn't just about skill or representation anymore; it was about ideas, feelings, and challenging norms. This paved the way for everything that came after, including the Contemporary Art Meaning: An Engaging Guide to Understanding that fills galleries today. For instance, the focus on performance in contemporary art owes a huge debt to the experiments of Dada and Conceptualism. The freedom to use any material? Thank modernism.

- It Celebrated the Individual: This era put the artist's unique perspective and inner world front and center. It's about seeing the world through their eyes, not just depicting it objectively. This focus on personal vision is crucial for any artist, myself included. It gave artists permission to be themselves.

- It Reflected a Changing World: The rapid industrialization, technological advancements, urbanization, and social upheaval of the time are all mirrored in the art. It's a visual history of a world in flux, grappling with new realities. Art became a way to process the chaos and excitement of modernity. It's a snapshot of a world reinventing itself.

- It's Just... Interesting! Seriously, look at a Dalí or a Picasso. They make you stop, think, and feel something, even if it's just confusion (which, trust me, is a valid reaction to some modern art!). If you've ever wondered, Is Modern Art Really 'Bad'? An Artist's Engaging Exploration, understanding this period is key to understanding why it looks the way it does. It challenges your perceptions and invites you to look deeper. It's a workout for your eyes and your brain.

For me, the freedom to explore abstraction (How to Make Abstract Art: Your Ultimate & Engaging Guide), use bold color, and focus on feeling in my own work is a direct legacy of these artists. My piece "Abstract Sky" (Abstract painting by Fons Heijnsbroek titled "Abstract Sky," featuring bold, gestural brushstrokes in red, blue, green, and white on a textured canvas.

credit, licence) for instance, owes a debt to the expressive use of color and form pioneered in this era. They dared to be different, to push boundaries, and that permission echoes through time, right into my studio today. You can see some of these influences, filtered through my own lens, if you explore my art for sale.

My Personal Takeaway

Walking through a modern art museum can sometimes feel overwhelming. So many styles, so many names! I remember feeling a bit lost the first few times. Is it okay to not 'get' it all? Absolutely. It's not about liking every single piece (I certainly don't!). It's about appreciating the courage, the innovation, and the sheer energy of this period.

I started looking for the threads – the shared desire to break free, the intense focus on color or form or emotion. I started seeing the connections, like how Fauvism's color paved the way for Expressionism's intensity, or how Cubism's fragmentation influenced abstract art and even design. It's a reminder that art isn't static; it's a living, breathing thing that constantly evolves, pushes boundaries, and reflects the messy, beautiful, complicated world we live in. It's a period I keep coming back to, finding new things to admire and be inspired by every time. If you're ever near 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, you could even visit my own museum (/den-bosch-museum) to see how these historical movements influence contemporary work!

Frequently Asked Questions About the Modern Art Time Period

Q: What are the exact start and end dates for the modern art period?

A: There's no single, universally agreed-upon date! It's generally considered to have started around the 1860s with Impressionism and ended around the 1970s with the rise of Postmodernism. It's more about a shift in attitude and approach than strict calendar dates. Many movements overlapped chronologically and influenced each other simultaneously.

Q: Is modern art the same as contemporary art?

A: No, they are different! Modern art refers to the period roughly 1860s-1970s. Contemporary art refers to art being made today or in the very recent past (generally from the 1970s onwards). Think of modern art as the parent and contemporary art as the child. You can read more about When Did Contemporary Art Start? The (Gloriously Fuzzy) Artist's Guide.

Q: Why did artists start moving away from realistic painting?

A: Many reasons! The invention of photography meant artists didn't need to be human cameras anymore. There was also a desire to express subjective experience, emotion, and the rapidly changing modern world in ways that realism couldn't capture. The rise of new patrons and the decline of traditional commissions also played a role, giving artists more freedom to experiment. Plus, honestly? Sometimes artists just want to try something new! The world was changing rapidly, and artists felt the need for new visual languages to reflect that.

Q: What makes the modern art period fundamentally different from previous eras?

A: The most significant difference is the fundamental questioning of art's purpose, subject matter, and form. Unlike previous eras where art often served religious, historical, or aristocratic purposes and aimed for realistic representation, modern art prioritized subjective experience, formal experimentation, and the artist's individual vision. It broke away from established academic rules and embraced innovation for its own sake, reflecting the radical changes of the modern world.

Q: Were there many women artists or artists from diverse backgrounds in these movements?

A: While the most widely recognized names from this period are often European or North American men, it's crucial to remember that women artists and artists from diverse backgrounds were active and made significant contributions, though they were often marginalized or overlooked by the mainstream art world at the time. This marginalization was often due to societal barriers that limited their access to formal training and exhibition opportunities (like the Salons), as well as historical biases in how art history was documented and taught. Figures like Berthe Morisot (Impressionism), Mary Cassatt (Impressionism), Hannah Höch (Dada), Frida Kahlo (Surrealism), and Anni Albers (Bauhaus) are just a few examples. Their work is increasingly being recognized and celebrated today.

Q: Is modern art difficult to understand? It sometimes feels like I'm missing something.

A: It can be, sometimes! Let's be honest, looking at a black square or a pile of bricks and being told it's profound can feel a bit... like you missed something. Or maybe like the artist is pulling a fast one. But it doesn't have to be difficult. Often, understanding the context – what the artists were reacting against (like the rigid academic system), what was happening in the world (like the impact of world wars or new psychological theories), and what question the artist was trying to ask – helps a lot. Don't feel pressured to 'get' everything instantly. Approach it with an open mind, look closely, and see how it makes you feel. Reading guides like this one (How to Read a Painting: An Artist's Guide to Deeper Art Understanding) can also give you tools to appreciate it more deeply. And remember, even artists sometimes scratch their heads! It's okay to be confused; that's often part of the point. It's a journey, not a test.

Q: How did modern art influence other fields like design or architecture?

A: Modern art movements had a profound impact on design and architecture. Bauhaus, for instance, directly integrated art and design principles, emphasizing functionality and clean lines that became hallmarks of modern design. De Stijl's geometric abstraction influenced architecture and furniture design. Constructivism impacted graphic design and theatre. The emphasis on form, color, and abstraction filtered into many creative disciplines, shaping the look of the modern world (What is Design in Art? An Artist's Personal & Engaging Guide).

Q: How did the art market change during the modern art period?

A: The modern art period saw a significant shift in the art market. As artists moved away from traditional commissions, the role of independent galleries, dealers, and critics became much more important. Artists began producing work for a broader public and a growing class of private collectors. This era laid the groundwork for the contemporary art market as we know it, where galleries play a central role in discovering, promoting, and selling artists' work, and where art's value is increasingly tied to critical reception and market demand rather than solely patronage (Navigating the Secondary Art Market: An Artist's Guide to Auctions & Resale).

Q: Did non-Western art influence modern art?

A: Absolutely! While this article primarily focuses on Western movements, the influence of non-Western art, particularly from Africa, Asia, and Oceania, was significant on many modern artists. Picasso and the Cubists, for example, were profoundly influenced by African masks and sculpture, appreciating their abstract forms and expressive power. Japanese prints (Japonisme) also heavily influenced Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. This cross-cultural exchange was a vital part of the modernist revolution, challenging Western artistic conventions and opening up new possibilities for form and expression. You can read more about this in How Non-Western Art Sparked the Modernist Revolution: An Artist's View.

Q: Where were the main geographical centers of modern art?

A: Initially, Paris was the undisputed center of the modern art world, home to Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism. However, after World War II, the focus dramatically shifted to New York City, which became the hub for Abstract Expressionism and subsequent movements like Pop Art and Minimalism. Other cities like Berlin, Vienna, and Moscow also played significant roles during specific periods.

Q: How did materials and techniques evolve during this time?

A: This period saw huge innovation in materials and techniques. Artists moved beyond traditional oil paint and canvas to embrace new possibilities. The invention of synthetic paints (like acrylics, though they became more widespread later) offered new vibrancy and speed. Artists incorporated industrial materials like steel, glass, and found objects (assemblage, readymades). Techniques like collage, screen printing, and automatic drawing opened up entirely new ways of creating art, reflecting the changing world and the desire to break from tradition.

Q: Where can I see modern art?

A: In major museums and galleries worldwide! Many have dedicated modern art wings or collections. Famous examples include MoMA in New York (Street view of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) building in New York City.

credit, licence), the Tate Modern in London (A view of the Tate Modern in London from the River Thames.

credit, licence), the Centre Pompidou in Paris (Panorama of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, France.

credit, licence), and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (Part of the Stedelijk (urban) museum in Amsterdam

credit, licence). Many smaller galleries also specialize in this period (Discover Local Art Galleries: Your Personal Guide to Finding & Enjoying Art). If you're ever near 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, you could even visit my own museum (/den-bosch-museum) to see how these historical movements influence contemporary work!

I hope this little journey through the modern art period sparks some curiosity for you too! It's a period that continues to inspire me, reminding me that art is a powerful force for change, expression, and seeing the world anew. It's messy, brilliant, and utterly human – much like the creative process itself. I keep coming back to it, finding new things to admire and be inspired by every time. You can see some of these influences, filtered through my own lens, if you explore my art for sale.