What is a Still Life? An Intimate Look at Everyday Objects Through Art

Ever wondered what makes a still life painting tick? Join me on a journey to uncover the history, profound symbolism, and enduring appeal of still life art, from ancient times to contemporary masterpieces. It’s more than just fruit in a bowl!

What is a Still Life? An Intimate Look at Everyday Objects Through Art

Have you ever dismissed a painting of a fruit bowl as just... a fruit bowl? I certainly did, for years! I remember the first time I truly saw a still life, and it wasn't in some grand museum gallery. No, no. It was a simple, dusty painting in a forgotten corner of an antique shop – a cluster of bruised apples, a chipped ceramic jug, and a half-eaten loaf of bread. Not exactly glamorous, right? Utterly devoid of typical "artistic drama." But something about the way the light fell, the palpable texture, and the sheer ordinariness of it all… it stopped me cold. It sparked a lifelong, almost obsessive, fascination. Before that, I admit, I probably dismissed still life as a bit, well, quiet. Just some fruit in a bowl, a decorative afterthought. Oh, how wrong I was! And if you've ever felt the same, believe me, you're in good company. Many assume still life is merely decorative, a background element in the grand tapestry of art history. But I'm here to tell you that this assumption couldn't be further from the truth. In fact, still life is a conversation – a silent, profound dialogue between artist, object, and viewer that has evolved over millennia. It’s an artist's meticulously curated universe on a canvas, a stage where every element plays a role, tells a story, or embodies a deeper truth. Join me, and let's unravel its enduring mystery together. Because, once you start truly looking, once you peel back the layers of varnish and intent, a fascinating narrative unfolds. This comprehensive guide aims to demystify the enduring appeal and profound depths of still life, offering insights for students, art enthusiasts, and anyone curious about finding the extraordinary in the everyday. This seemingly simple genre is, in my humble opinion, one of the most intellectually stimulating and emotionally resonant forms of artistic expression.

At ZenMuseum, our goal is to bring art to life, and what better way than through the lens of a genre that finds the extraordinary in the everyday? Consider this your definitive guide – a deep dive into the quiet power of still life, from its ancient origins to its vibrant contemporary forms. So, let's explore, shall we? You might just find yourself seeing the world (and your kitchen counter!) with a whole new appreciation. It's truly a journey of discovery, a whispered secret shared across centuries, and I, for one, am endlessly captivated by its timeless appeal. This seemingly simple genre is, in my humble opinion, one of the most intellectually stimulating and emotionally resonant forms of artistic expression.

Unpacking the Definition: What Exactly is a Still Life?

Before we embark on our artistic journey, let's lay down a clear foundation: what exactly is a still life? For me, it's more than just an arrangement; it's a deliberate act of choosing, composing, and imbuing inanimate objects with life, meaning, and emotion.

At its core, a still life (or nature morte, as the French so poetically call it, literally 'dead nature') is a work of art dedicated to depicting inanimate objects. And isn't that nature morte fascinating? I mean, it's not just 'dead nature' in the sense of inert, but rather, a profound, almost melancholic, nod to the transience of life itself, a pervasive theme we'll explore much deeper. It hints at the impermanence of all things, even as it immortalizes them on canvas, offering a poignant dialogue between presence and absence. These objects are typically commonplace items, which can be either natural elements like food, flowers, game, rocks, or shells, or man-made objects such as drinking glasses, books, vases, jewelry, or pipes. Sounds deceptively simple, doesn't it? As I see it, the beauty often lies in their very ordinariness, inviting us to look closer at what we often overlook.

It's also important to acknowledge that the definition of still life has expanded significantly over time. While traditional still life often refers to painted or drawn compositions, the genre now encompasses still life photography, sculptural still life (often involving assemblage or found objects), and even digital and video art. The key unifying factor remains the deliberate arrangement of inanimate elements to create meaning, beauty, or a particular message.

But here’s where the real magic, the profound artistry, truly happens: it's all about the arrangement and the intent behind that arrangement. A still life is a deliberate act of observation and introspection, transforming the mundane into the meaningful. Unlike a landscape, which captures a vast vista, or a portrait, which focuses on a living being, a still life provides a controlled, intimate stage for reflection. It's a particular branch of what we call genre painting, which focuses on scenes from everyday life. But here, the 'actors' are often silent, allowing for an intensity of focus on composition, symbolism, and the sheer beauty of form and light that other genres might not afford. This controlled environment allows the artist to manipulate every element, crafting a precise message or evoking a specific emotion, often in ways a grander scene cannot.

To further clarify, let's look at how still life stands apart from other major art genres:

Feature | Still Life | Portraiture | Landscape Painting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Inanimate objects (natural or man-made), deliberately arranged | Living beings (humans, animals), capturing likeness, personality, emotion | Natural scenery (mountains, rivers, forests, sky), capturing atmosphere and grandeur |

| Artist Control | Near-absolute control over arrangement, lighting, timing, symbolism | Significant control over pose, lighting, setting; less over inherent personality/mood | Limited control over natural elements (weather, light); focus on observation and interpretation |

| Primary Focus | Composition, symbolism, texture, light, form, philosophical themes (e.g., mortality, abundance) | Individual identity, emotion, social status, psychological insight | Nature's beauty, sublimity, human interaction with environment, specific geographic locations |

| Narrative | Often implied, symbolic, or allegorical through object relationships | Direct narrative through subject's expression, posture, or accompanying attributes | Evokes mood, sense of place; narrative can be implied by human presence or structures |

| Key Advantage | Offers a controlled 'laboratory' for artistic experimentation, deep introspection, and symbolic layering | Captures a moment of a living presence, deep psychological connection | Transports viewer to another place, evokes awe or tranquility, reflects on humanity's place in nature |

Artists meticulously compose these objects, paying exquisite attention to every nuance of light, shadow, texture, and color. It's not a casual toss of items into a basket; it's a deeply thoughtful, almost ritualistic, process of choosing, placing, and portraying. They are, in essence, creating a tiny, self-contained universe on their canvas, where every element serves a precise purpose – be it purely aesthetic, deeply symbolic, or often, both. It’s a quiet meditation on existence, asking us to slow down and consider the lives (or perhaps, the echoes of lives) of the objects that fill our world. In a way, it's a profound act of giving voice to the voiceless, prompting us to examine our own relationship with the material world around us and the stories they silently tell.

A Brief History: From Ancient Murals to Modern Reflections

Now, you might immediately associate still life primarily with those exquisite Dutch Golden Age painters – and you'd be absolutely right to a significant extent, they truly catapulted the genre into its own limelight. But the truth is, the story of still life has a much longer, richer history of still life painting than many realize, tracing its roots deep into antiquity. It's a journey, really, from the practical and spiritual necessities of ancient cultures to the profound philosophical statements of modernity. So, settle in, because this historical narrative is far more dynamic than you might expect from a genre focused on 'still' objects.

Even during the Medieval period, while still life as a standalone genre was rare, inanimate objects were frequently incorporated into religious works. Think of the elaborate altarpieces and illuminated manuscripts, where meticulously rendered chalices, flowers, or books often held profound theological significance, acting as silent symbols to enhance the spiritual narrative. These objects weren't just decorative; they were visual prayers, each element carefully chosen to deepen the viewer's understanding of sacred stories.

My own research (and quite a few deep dives into dusty art history books, I confess) reveals rudimentary forms of still life appearing in ancient Egyptian tombs as far back as the 15th century BC. Here, depictions of food, offerings, and domestic items weren't just pretty pictures; they were profoundly practical magical provisions, meant to sustain the deceased in the afterlife – an early, very tangible form of symbolism, if you ask me. We're talking about incredibly detailed, almost hyper-realistic, representations of everything from baskets of figs and grapes to perfectly rendered fish and fowl, alongside jars of wine and loaves of bread. Imagine, if you will, the painstaking detail applied to a basket of figs or a perfectly rendered duck, not just for aesthetic pleasure, but for an eternal purpose, ensuring eternal sustenance and comfort. These weren't mere decorations; they were vital necessities for the journey beyond, a tangible link between the earthly and the eternal. It's fascinating how a genre we often consider 'modern' has such ancient, practical, and spiritual roots, isn't it?

Fast forward to the Greeks and Romans, who also masterfully incorporated realistic paintings of everyday objects into their art, albeit with different cultural intentions. Think of those incredible frescoes and mosaics found in places like Pompeii, with bowls of fruit so vibrant and lifelike they almost seem to burst off the wall, or game birds depicted with stunning, almost tactile detail. These weren't always purely decorative, though they certainly adorned dining rooms and villas beautifully. They often celebrated abundance, hospitality, and the sheer, fleeting beauty of the natural world. The Romans, in particular, created what they called xenia, which were hospitality still lifes depicting food meant for guests – a charming and elegant touch, wouldn't you agree, an artistic welcome mat? This period also saw emblema, small, intricate still life motifs often used in mosaics for floor and wall decoration, and even earlier, Greek pinakes, painted tablets used for votive offerings to deities, and megalographia, large-scale decorative murals featuring everyday items, often with an almost monumental presence. It was here, too, that the seeds of trompe l'oeil – 'to deceive the eye' – began to flourish, with artists creating illusions so convincing you'd almost reach out to grab a painted grape.

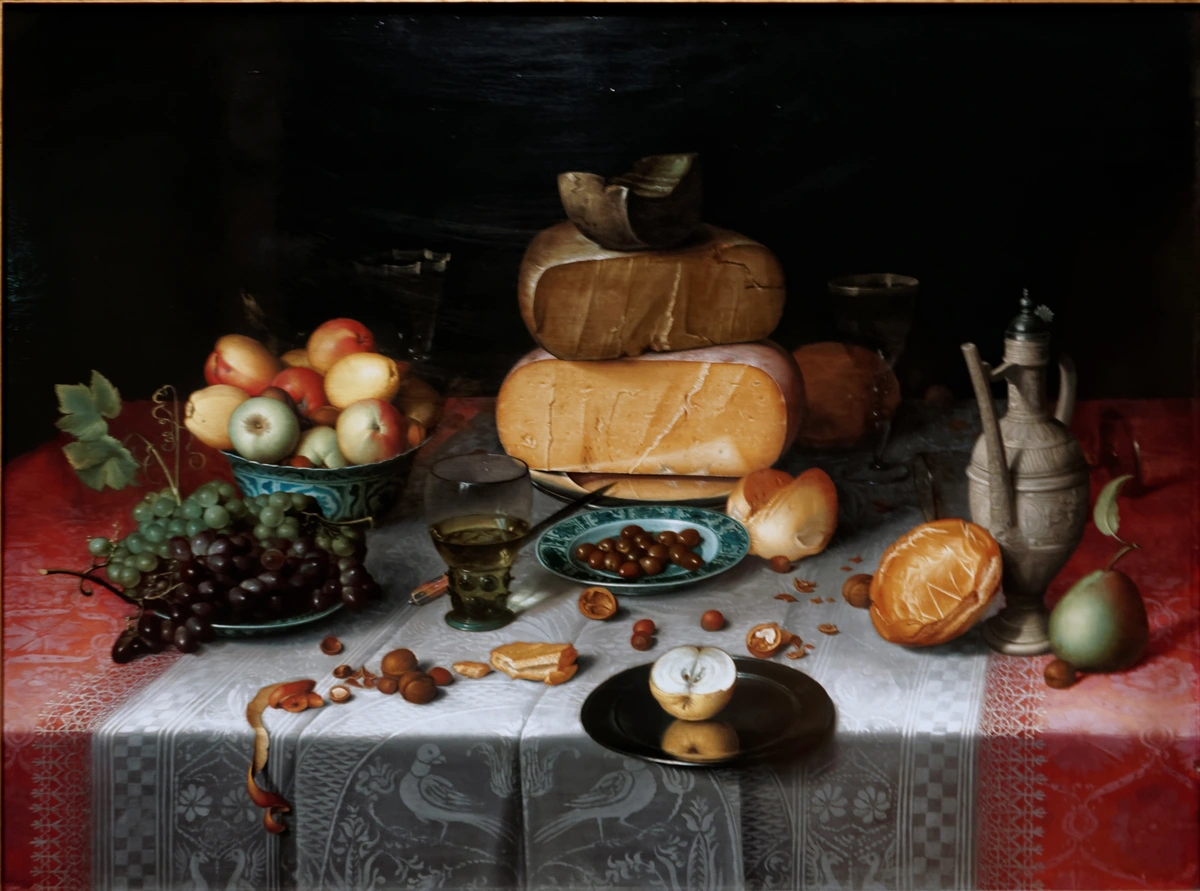

However, it was during the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age that still life truly soared, emerging as a celebrated and independent genre in its own right. Why the Netherlands, you ask? Well, several fascinating factors converged. The rapid rise of a wealthy merchant class, with newly acquired disposable income and a desire to display their affluence, coupled with a prevailing Calvinist ethos that often eschewed grandiose religious commissions, created a vibrant and eager market for art in private homes. This societal shift, moving artistic patronage from the church and nobility to private citizens, meant that artists needed to cater to new tastes. Still life, with its focus on domestic objects and often subtle moral messages, fit perfectly into this new cultural landscape. Suddenly, everyday objects – meticulously rendered and often imbued with rich moral and religious symbolism – became highly desirable. Artists like Floris van Dijck, Willem Kalf (whose opulent Pronkstilleven are simply breathtaking), Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Pieter Claesz., and Clara Peeters weren't just painters; they were visionaries who elevated the genre to an art form worthy of serious contemplation and significant patronage. These weren't just pretty pictures; they were simultaneously status symbols, moral compasses, and complex narratives disguised as domestic scenes. It was, indeed, a golden era for meticulously rendered apples, glistening cheeses, and reflective silver goblets, each detail painstakingly painted to perfection! If you're as fascinated by this period as I am, you might want to explore our article on 5 Iconic Artworks of the Dutch Golden Age for more context, or delve deeper into The History of Still Life Painting: From Antiquity to Modernism.

Within this vibrant period, several distinct sub-genres emerged, each with its own charm and message, reflecting the diverse interests and values of the Dutch society. These categories aren't always mutually exclusive, and many works blend elements from several:

Sub-Genre | Characteristics & Focus | Common Symbolism & Message |

|---|---|---|

| Pronkstilleven | Elaborate, opulent displays of exotic fruits, luxurious imported goods, fine glassware, intricate silverware, sometimes rare shells or live animals. | Wealth, status, abundance, luxury, but almost invariably a subtle hint at the fleeting nature of such earthly possessions and the dangers of worldly excess. |

| Vanitas | Highly symbolic compositions featuring objects that serve as reminders of mortality and the transience of life. Skulls, extinguished candles, wilting flowers, bubbles, scattered coins, decaying fruit, hourglasses. | The brevity of life, the futility of earthly achievements and pleasures, the inevitability of death, and the importance of spiritual values over material ones. |

| Ontbijtjes | Literally 'little breakfasts', these intimate scenes depict simple, everyday meals, often arranged on a plain table. Bread, cheese, butter, simple utensils. | Domesticity, the modest comforts of life, the quiet beauty of routine, temperance, frugality. Often invites viewers to appreciate the present moment and simple blessings. |

| Flower Pieces (Bloemstukken) | Focuses solely on elaborate floral arrangements, often featuring rare and exotic blooms in vases or baskets. | The ephemeral beauty of nature, the cycle of life and death, fertility, fragility. Individual flowers often carried specific symbolic meanings (e.g., lily for purity, rose for passion). |

| Fruit Pieces | Highlights the luscious forms and textures of various fruits, often depicted at different stages of ripeness or decay. | Abundance, temptation (apple), fertility (pomegranate), generosity (peach), transience and the passage of time (half-eaten or rotting fruit), the bounty of nature. |

| Game Pieces (Jachtstukken) | Showcases dead animals (birds, rabbits, fish) as hunting trophies or freshly caught food, often with extraordinary skill in rendering textures of fur and feather. | The bounty provided by nature, the owner's status or culinary tastes, life's fragility, the cycle of life and death, the hunt. |

| Kitchen Pieces (Keukenstukken) | Depicts bustling kitchen scenes or carefully arranged food items and cooking utensils, often with figures in the background. | Domesticity, the bounty of the land, the simple pleasures of home, daily sustenance. Often carried a subtle moralizing undertone about moderation or diligence. |

| Still Life with Insects | Features insects like butterflies, flies, or caterpillars often interacting with fruit or flowers. | Decay, resurrection and metamorphosis (butterflies), the fleetingness of life, the natural world's intricacies, temptation, corruption. |

These artists didn’t just paint objects; they painted stories, often layered with complex symbolism, inviting the viewer to look beyond the surface and engage in a dialogue with the artwork. It’s why I find these works so compelling – they’re a masterclass in subtlety and profound meaning, often revealing more about the society and values of the time than a direct historical painting might. They spoke a quiet language that was deeply understood by the people of their era, and still resonates today if you know how to listen. It's a testament to the power of the genre that it could convey such weighty philosophical and moral messages through seemingly simple arrangements. It truly was a golden age of quiet masterpieces.

These artists didn’t just paint objects; they painted stories, often layered with complex symbolism, inviting the viewer to look beyond the surface and engage in a dialogue with the artwork. It’s why I find these works so compelling – they’re a masterclass in subtlety and profound meaning, often revealing more about the society and values of the time than a direct historical painting might. They spoke a quiet language that was deeply understood by the people of their era, and still resonates today if you know how to listen. It's a testament to the power of the genre that it could convey such weighty philosophical and moral messages through seemingly simple arrangements. It truly was a golden age of quiet masterpieces.

Fast forward through the centuries, and the still life continued its remarkable evolution, mirroring broader shifts in artistic thought and societal values. The 18th century saw masters like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin elevate everyday household items – a simple glass of water, a loaf of bread, a humble pipe – into subjects of profound contemplation, often imbued with a quiet dignity and a meticulous focus on textural realism that still takes my breath away. Chardin's genius lay in his unparalleled ability to transform the mundane into the monumental, giving an almost sacred dignity to the simplest kitchen scenes. He wasn't just painting objects; he was painting the subtle interplay of light and shadow, the very essence of their presence, capturing the quiet poetry of domestic life. His work often felt like a hushed, intimate conversation, inviting us to see the profound beauty in the ordinary, a powerful, introspective counterpoint to the more grandiose, theatrical works of his contemporaries. It's the kind of art that teaches you to slow down and truly observe the world around you, a lesson I constantly revisit in my own abstract work.

While Chardin's introspective realism dominated, the Rococo period also saw still life integrated into decorative schemes, often lighter in tone, with delicate floral arrangements and porcelain figures mirroring the era's taste for elegance and whimsy. Later, the more austere and moralizing aesthetic of Neoclassicism brought a return to classical forms and principles, sometimes incorporating still life elements that emphasized simplicity, virtue, or historical themes, though the genre remained secondary to grand historical narratives during this time.

In the burgeoning 19th century, the Impressionists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Henri Fantin-Latour, with their radical obsession with capturing fleeting moments, subjective perceptions, and the ephemeral effects of light, found still life to be a perfect laboratory. They experimented with broken brushstrokes and vibrant, unblended palettes, making a vase of flowers sing with transient light and atmospheric nuance, dissolving solid forms into a dance of color. Think of Monet's haystacks or Rouen Cathedral series, where the subject was less the object itself and more the changing light upon it – a principle he applied equally to his still lifes of flowers. Renoir's lush floral arrangements, often brimming with vitality, captured the sheer joy of color and light.

Following them, Post-Impressionists took these innovations further, imbuing objects with intense personal emotion and psychological depth. Vincent van Gogh, with his raw, impassioned sunflowers and stark depictions of everyday objects (who could forget his iconic "Shoes"?), made a simple still life vibrate with inner turmoil and passion. His "Sunflowers" series, for example, transcends mere botanical study, becoming a vibrant testament to life, friendship, and artistic struggle. Paul Gauguin, on the other hand, used still life to explore exoticism, symbolic color, and a return to more primitive forms, often featuring fruits and artifacts from his travels, making them resonate with deep, personal meaning. This era truly proved that even the most 'still' objects could pulse with the artist's inner world.

Then came Paul Cézanne, a true titan who, through his iconic still lifes of apples, fruit bowls, and humble domestic scenes, fundamentally altered how we perceive art. He wasn't just painting apples; he was dissecting their form, their weight, their relationship to space, paving the way for Modernism and Cubism itself. He famously declared his intention to "treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone," essentially proposing that all forms could be reduced to basic geometric shapes. He completely deconstructed and reassembled objects in ways that challenged conventional perception, making you see them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. His meticulous study of form and color, breaking objects down into their geometric components, was revolutionary. Think about it: he wasn't interested in a perfect illusion, but in revealing the underlying, enduring structure of reality itself, effectively bridging the gap between traditional representation and abstract thought. For me, Cézanne is the ultimate bridge-builder, connecting the tangible world to the abstract language I often explore.

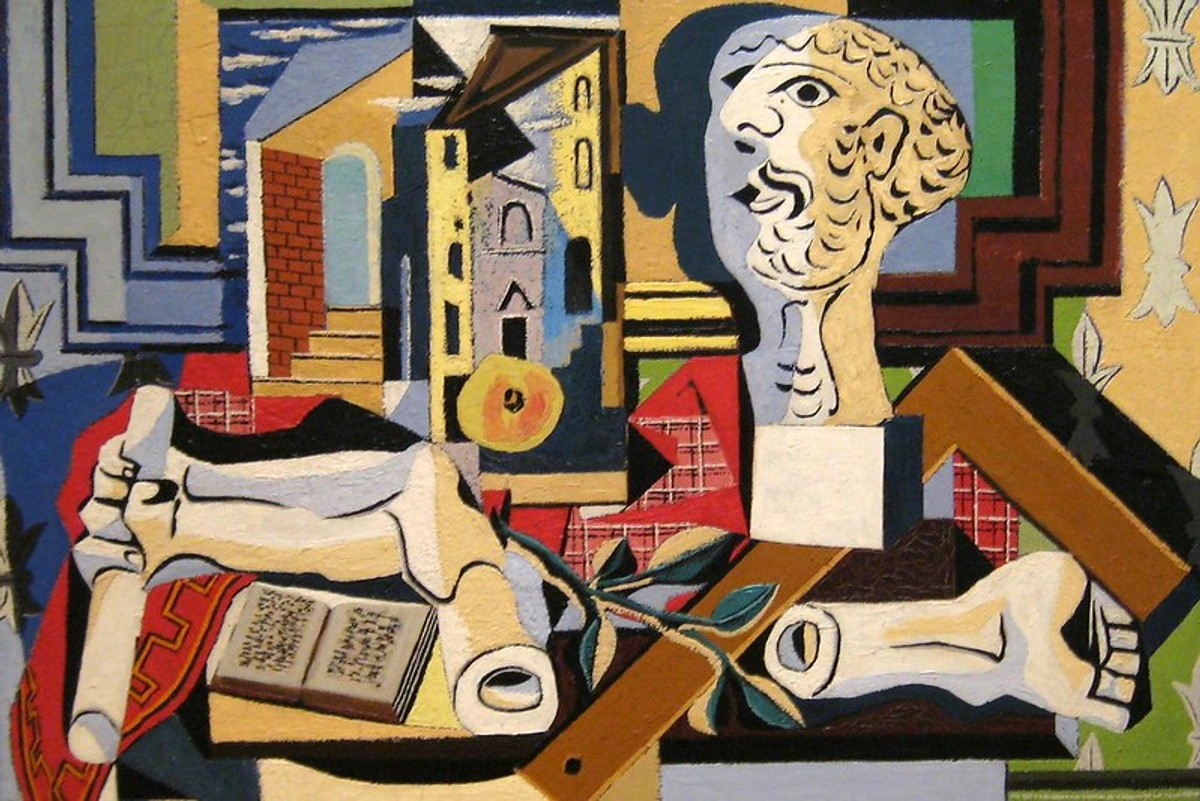

Picasso, for instance, a direct inheritor of Cézanne's revolution, created iconic Cubist still lifes, often alongside Georges Braque, that force you to see a guitar, a bottle, or a plaster head from every conceivable angle at once, fracturing reality into a multifaceted experience. It’s utterly mind-bending, in the best possible way! The 20th century then saw still life embrace even more radical shifts. Think of the vibrant, expressive colors and deconstructed forms of Fauvist still lifes, where artists like Henri Matisse used bold, non-naturalistic colors to convey emotion rather than literal representation, making a simple fruit bowl explode with joyous energy. Or consider the dynamic motion and technological celebration evident in Futurist compositions, where objects were depicted in constant flux, emphasizing speed and modernity.

Later in the century, Pop Art redefined still life by elevating everyday consumer objects – think Andy Warhol's iconic Campbell's soup cans or Brillo boxes – to high art, blurring the lines between commercialism and fine art and questioning consumer culture. This movement challenged traditional notions of what constituted 'artistic' subject matter. And let's not forget Hyperrealism (or Photorealism), which pushed the boundaries of realism to an almost unsettling degree, creating paintings of still life arrangements that could easily be mistaken for photographs, often commenting on the nature of perception itself. If you want to dive deeper into how this foundational shift led to one of art's most radical movements, our Ultimate Guide to Cubism is an essential read.

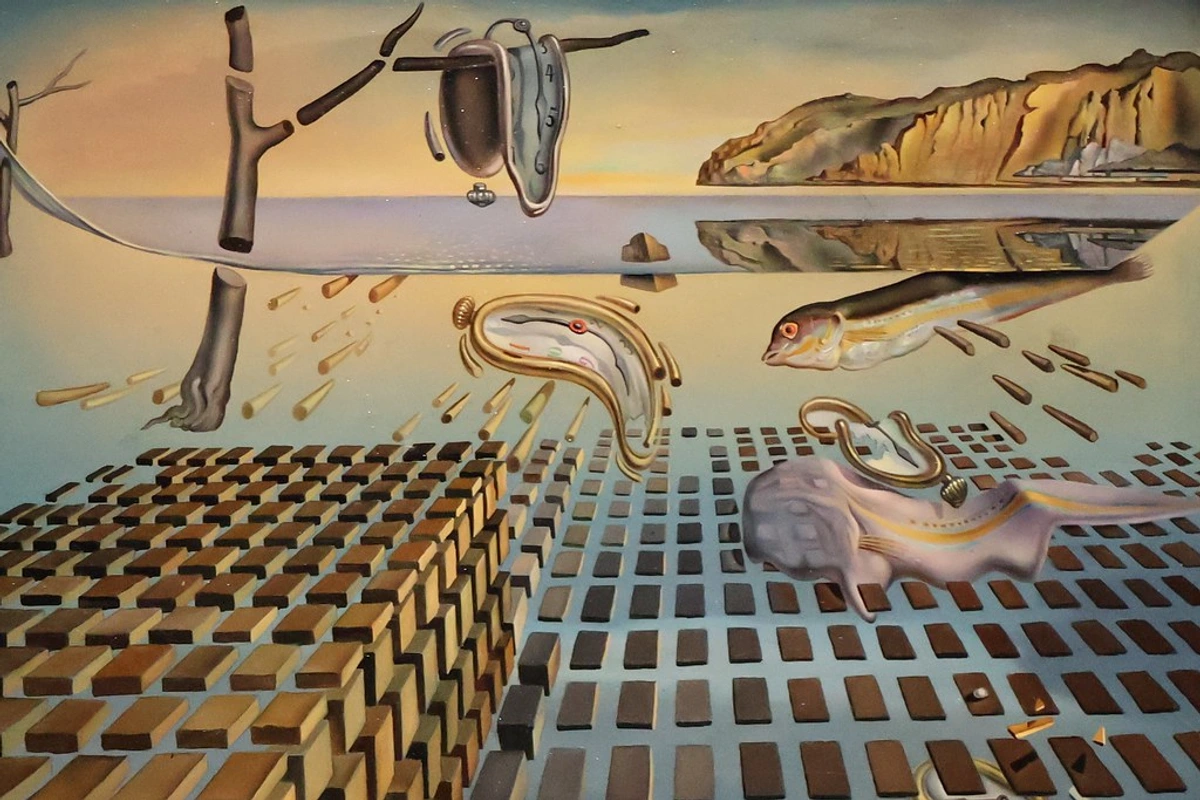

The journey didn't stop there; in fact, it only got wilder. The Surrealists, like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, twisted the concept of the inanimate into bizarre, dreamlike, and often disturbing psychological landscapes, proving that objects could hold the key to our subconscious, revealing hidden desires and anxieties. Dalí's melting clocks, for example, from "The Persistence of Memory," aren't just objects; they're profound symbols of the fluidity of time, the dream state, and the fragility of memory, forcing us to question the very nature of reality itself. Magritte, too, masterfully challenged our perceptions with his seemingly straightforward yet utterly baffling arrangements, often pairing disparate objects to create a sense of uncanny strangeness, or directly questioning the representation of objects and the relationship between words and images. This period truly dug deep into the psychology of things, didn't it, using the ordinary to unlock the extraordinary. Magritte's 'The Treachery of Images' with its iconic "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" (This is not a pipe) still makes me smile and think deeply about the relationship between art and reality, even in my own abstract compositions.

This incredible flexibility and enduring appeal of the still life format, its ability to adapt and reinvent itself across centuries and movements, is a profound testament to its power and its deep resonance with the human experience. It's a genre that refuses to stay 'still', continually reflecting and shaping our understanding of the world around us. In many ways, it's a silent cultural barometer, subtly shifting to reveal the concerns and aspirations of each era.

The Language of Objects: Symbolism in Still Life

This is where still life, for me, truly transcends mere aesthetic appeal and ventures into the realm of philosophy and psychology. It's not just about creating pretty pictures; it's about initiating unspoken conversations, challenging perceptions, and delving into the layers of meaning embedded in the everyday. Objects in a still life are almost never chosen at random; they are meticulously selected and placed, often laden with deep symbolic meanings. These symbols invite viewers to contemplate morality, the delicate balance of life, its fleeting nature, or conversely, the sheer abundance and generosity of the world around us. It's a subtle language, an artistic code, that has evolved and adapted across cultures and centuries, yet its core message remains potent: look closer, think deeper. It's like a secret handshake between the artist and the viewer, a shared understanding that there's more beneath the surface. As an artist, I find this conversation endlessly compelling, and it's a foundation that even my most abstract works build upon.

Symbolism Across Cultures and Eras

While we often focus on European still life symbolism, it's crucial to remember that objects hold profound cultural weight everywhere, speaking silent volumes across civilizations. From ancient Chinese depictions of auspicious fruits like peaches (longevity) and pomegranates (fertility), to Japanese kachō-ga (bird-and-flower paintings) with their seasonal and poetic connotations (e.g., cherry blossoms for transience, pine for endurance), or even indigenous cultures using carefully arranged natural elements in spiritual contexts – the impulse to imbue inanimate objects with deeper meaning is a universal human trait. The specific 'language' might change dramatically, but the fundamental grammar of symbolism persists, adapting seamlessly to local beliefs, philosophical currents, and historical events. It's a fascinating, global cross-cultural conversation, really, proving that humans everywhere seek meaning beyond the surface. For example, in many African traditions, specific natural objects or crafted items are imbued with spiritual power, acting as conduits for ancestral wisdom or protective energies, much like a carefully chosen skull in a European Vanitas painting might evoke mortality.

Across cultures, we can often categorize still life symbolism into broader themes:

Thematic Category | Common Symbolic Objects | Core Message & Interpretation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality & Transience | Skulls, extinguished candles, wilting flowers, rotting fruit, hourglasses, bubbles, smoke, watches. | Life is fleeting, death is inevitable, earthly pleasures are temporary. (Classic Vanitas theme) | ||||

| Abundance & Prosperity | Bountiful harvests of fruit and vegetables, overflowing cornucopias, exotic imported goods, fine glassware, full wine glasses, coins, jewelry. | Celebration of wealth, earthly blessings, nature's generosity, the fruits of one's labor, success. (Often seen in Pronkstilleven). | ||||

| Knowledge & Learning | Books (open or closed), maps, globes, writing implements, scientific instruments, scrolls, musical scores. | Intellectual pursuit, wisdom, education, the arts, the vastness of human understanding, exploration, worldly ambition (can also be a Vanitas element if hinting at vain knowledge). | ||||

| Spirituality & Faith | Chalices, bread, wine, specific flowers (e.g., lily for purity), religious texts, symbolic animals (e.g., lamb for sacrifice). | Devotion, sacrifice, purity, divine presence, specific religious doctrines, spiritual journey, essential sustenance. | ||||

| The Senses | Musical instruments (hearing), luscious fruit (taste), fragrant flowers (smell), velvet cloth (touch), mirrors or artworks (sight). | The pleasures and experiences of the physical world, often in allegorical still lifes representing the five senses. | ||||

| Domesticity & Home | Everyday household items, simple meals, kitchen utensils, humble fabrics, woven baskets. | The comforts of home, daily life, simple pleasures, family values, the rhythm of existence, often with subtle moral undertones of diligence or moderation. (Common in Ontbijtjes and Kitchen Pieces). | ||||

| Vanity & Earthly Pleasures | Jewelry, cosmetics, luxurious fabrics, playing cards, pipes, exotic foods, mirrors (often reflecting the viewer). | The seductive, yet ultimately hollow, nature of material possessions, self-adornment, and worldly indulgences; a warning against excessive pride or attachment to the ephemeral. | n | Change & Transformation | Butterflies (metamorphosis), wilting flowers, fruit at different stages of ripeness/decay. | The natural cycles of growth, decay, and renewal; the ever-present process of change in life and nature. |

Memento Mori: The Art of Remembering Mortality

One of the most famous and potent sub-genres is Vanitas painting, particularly prevalent in the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age. These works were far more than decorative; they were stark, often beautiful, reminders of the transient nature of life, the hollow futility of earthly pleasures, and the chilling inevitability of death. My personal take? They're essentially fancy artistic 'memento mori' – powerful reminders that we're all just passing through, and perhaps we should focus on the eternal rather than the ephemeral. They were a sophisticated way of saying, "Enjoy life, but don't forget the end." The inclusion of these symbols wasn't a subtle hint; it was a profound, often moralizing, statement. A combination of a skull (mortality), an extinguished candle (life's end), wilting flowers (fleeting beauty), and perhaps a book (vain knowledge) could weave a complex, sobering narrative. They were a mirror reflecting the viewer's own mortality, a sobering counterpoint to the era's burgeoning wealth and material indulgence. You can almost feel the weight of these existential questions in every brushstroke, and it always makes me pause and reflect on my own priorities.

Common Still Life Symbols and Their Meanings

Object | Common Symbolism |

|---|---|

| Skull | Death, mortality, brevity of life (classic Vanitas), human finitude |

| Hourglass/Clock | Passage of time, fleeting existence, temporal limits, countdown to eternity |

| Candle (extinguished) | Life extinguished, death, transience, lost hope, the end of light |

| Rotting Fruit | Decay, aging, impermanence, original sin, fleeting beauty, the cycle of life and death |

| Flowers (wilting) | Fragility of life, beauty's short span, rebirth, ephemeral nature, lost innocence |

| Bubbles | Brevity of life, fragility, emptiness, illusion, fleeting nature of human life, vanity |

| Books/Musical Instruments | Human knowledge, arts, intellectual pursuits (can also be vanity or worldly pleasure), learning, leisure, inspiration, transient pleasures of the senses |

| Coins/Jewelry | Wealth, earthly possessions, vanity, fleeting riches, material desire, earthly temptation |

| Peeled Lemon | Life's bitterness, deceptive allure, sourness of worldly pleasures, hidden truths, deceptive appearances |

| Insects (flies, butterflies) | Decay, resurrection (butterflies), fleeting life (flies), temptation, change, metamorphosis, corruption |

| Shells | Fragility, human existence, distant travels, isolation, beauty, natural world, the soul |

| Game/Meat | Flesh, earthly sustenance, mortality, physical appetite, sacrifice, the hunt |

| Musical Scores | Harmony, sensory pleasure, transient joy, artistic pursuits, fleeting melody, the ephemeral nature of sound |

| Mirror | Vanity, self-reflection, illusion of reality, self-awareness, truth, introspection |

| Empty Glass/Vessel | Emptiness, absence, the void, unfilled desires, purity, the receptacle of life |

| Wine Glass (full) | Pleasure, indulgence, prosperity, celebration, spiritual communion (religious context), the richness of life |

| Knife | Danger, violence, sacrifice, precision, cutting ties, tool for creation/destruction, the cutting edge of truth |

| Sword/Armor | Power, earthly struggles, vanity of war, human conflict, protection, aggression, transient glory |

| Bread | Sustenance, life, spirituality, simplicity, body of Christ (religious context), daily provision, essential nourishment |

| Wine | Pleasure, indulgence, blood of Christ (religious context), festivity, transformation, spiritual essence |

| Keys | Access, knowledge, freedom, hidden meanings, opportunity, authority, unlocking secrets |

| Snakes | Temptation, evil, rebirth, healing, wisdom, eternal life, forbidden knowledge |

| Drapery | Wealth, status, theatricality, sensuality, mystery, concealment, the flow of time |

| Globe/Maps | Worldly ambition, travel, knowledge, exploration, vastness, human endeavor, the vastness of human ambition |

| Smoke | Transience, fleeting existence, ephemerality, spiritual communication, dissipating hopes |

| Broken Glass | Fragility, destruction, loss, shattered dreams, disorder, vulnerability, the fragility of order |

| Watch/Clock | Passage of time, fleeting existence, temporal limits, precision, measurement, the unstoppable march of time |

| Feather | Lightness, air, freedom, intellect, soul, creativity, spirituality, delicate existence |

| Spider/Web | Fate, entrapment, patience, industry, creative power, mystery, diligence, the delicate balance of nature |

Even today, artists continue to harness the evocative power of everyday objects to tell profound stories. Think about the way a modern photograph of a discarded coffee cup and a newspaper can evoke feelings about solitude or the daily grind, speaking volumes without a single word. Or how a carefully curated Instagram flat lay of a meal can evoke a sense of aspiration or comfort. The language of objects is truly universal, even if the dialect shifts and evolves over time, adapting to new technologies and cultural contexts.

Beyond Vanitas: Other Symbolic Traditions

While Vanitas stands as a profoundly powerful example, not all still life symbolism is about mortality and decay. Far from it! Many works celebrated the abundance of nature, the simple joys of domestic life, or even intellectual pursuits.

Allegorical Still Life

Allegorical still lifes, for instance, meticulously used objects to represent abstract concepts like the five senses, the four seasons, the elements, or the arts and sciences. Imagine a painting featuring musical instruments (hearing), luscious fruit (taste), fragrant flowers (smell), a velvet cloth (touch), and a mirror (sight) to represent the senses – it's an invitation to a multi-layered, almost interactive, interpretation. Another might depict specific seasonal fruits and vegetables, alongside a scythe, to represent autumn and the harvest. It's a rich tapestry of meaning, where every chosen item contributes to a larger, often grand, narrative.

Consider the surrealist master René Magritte, whose profound still lifes often played with paradox, illusion, and the very mechanics of perception. He possessed an uncanny ability to take the most ordinary objects – an apple, a pipe, a rock, a shoe – and place them in unexpected, often unsettling, contexts, fundamentally challenging our very perception of reality. For example, his iconic painting 'The Treachery of Images,' depicting a pipe with the famously enigmatic caption 'Ceci n'est pas une pipe' (This is not a pipe), forces us to confront, with a wry smile, the fundamental difference between an object and its artistic representation, and indeed, the intricate, often deceptive, nature of language and image itself. It's a powerful, enduring reminder that sometimes, the most mundane items can become profound philosophical statements when viewed through an artist's ingenious lens, persistently questioning the boundary between representation and reality. His cleverness in making us question what we see always makes me chuckle, and then think for hours.

The Craft: Composition and Artistic Choices

Creating a compelling still life isn't just about picking interesting objects; it's about arranging them in a way that creates harmony, tension, or a specific narrative. This is where the artist's principles of still life composition truly shine, transforming a static collection into a dynamic visual choreography. The thoughtful consideration of elements like light, color, texture, arrangement, and perspective is what elevates a simple collection of items into a profound work of art.

I find it endlessly fascinating how a slight shift in an object's position, the play of light from a different angle, or a change in background color can completely alter the mood and message of a piece. It's a masterclass in control and intentionality, where every decision is a deliberate stroke in crafting the narrative. It truly highlights the artist's power to manipulate our perception and emotion through seemingly simple arrangements.

Artists often consider:

- Light and Shadow: Oh, where do I even begin with light? It’s not just about illumination; it's the magician of the composition. How light falls on objects creates form, reveals texture, carves out depth, and utterly dictates the mood. Think of chiaroscuro, that dramatic, often stark, contrast between light and dark, which can create incredible tension, mystery, and a powerful sense of three-dimensionality. Or consider tenebrism, a specific technique that plunges much of the scene into oppressive shadow, making a few brightly lit elements pop with intense, almost theatrical, drama, often used by Caravaggio and his followers. Then there's sfumato, a soft, hazy blurring of lines and colors, often associated with Leonardo da Vinci, which allows objects to gently emerge from shadow, creating an ethereal, dreamlike quality. We also talk about value, which is the lightness or darkness of a color, a fundamental element in creating the illusion of three-dimensional form. It's truly about shaping reality and guiding your eye, directing precisely where you look and how you feel. A master of light can turn a simple apple into a glowing orb of mystery, or a common jug into a monument of form, imbued with silent power. It's truly transformative, and for a deeper understanding, our Definitive Guide to Understanding Light in Art and The Definitive Guide to Understanding Value in Art: Light, Shadow, and Form are illuminating reads. I find myself constantly chasing that perfect interplay of light and dark in my own abstract compositions, trying to create depth and intrigue even without recognizable objects.

- Color Palette: The choice of colors, for me, is like setting the emotional temperature of the room, or orchestrating a visual symphony. Warm colors (reds, oranges, yellows) can bring energy, intimacy, and a sense of inviting closeness, while cool colors (blues, greens, purples) evoke calm, distance, or even melancholic contemplation. Artists might choose a monochromatic palette for serenity and unity, complementary colors for vibrant, attention-grabbing contrast, analogous colors for a harmonious, soothing blend, or even more complex triadic or tetradic schemes for richer, more dynamic visual narratives. It’s all about evoking a specific feeling or making a powerful visual statement – think of how a vibrant splash of red can punctuate an otherwise subdued composition, drawing the eye instantly. And it's not just the individual colors themselves, but how they interact with each other, vibrating against one another or melting into a soft, ethereal gradient. It's a symphony of hues, really, and I often use bold, unexpected color combinations in my own work to provoke emotion and thought. Understanding The Definitive Guide to Color Theory in Art, How Artists Use Color, and The Psychology of Color in Abstract Art: Beyond Basic Hues can truly open your eyes to the subtle, profound power of chromatic choices in still life.

- Texture: The tactile qualities of surfaces – from the inviting smoothness of polished glass to the rustic roughness of woven fabric, the delicate translucence of a grape, or the craggy, aged skin of an old pear – are profoundly crucial. Texture doesn't just create visual interest; it creates depth and a powerful sense of realism, almost begging your eye (and sometimes, your imagination!) to reach out and touch. It’s all about how light interacts with these varied surfaces, revealing every minute bump, subtle crease, or brilliant sheen, giving the objects a tangible, almost living, presence in the artwork. We're not just seeing; we're almost feeling the piece. Artists might use impasto, thick, sculptural applications of paint, to physically build up textures on the canvas, or employ meticulous, illusionistic brushwork to create the illusion of various surfaces, sometimes even verging on trompe l'oeil (literally 'to deceive the eye') – a technique so convincing it makes you doubt what's real. Think about how a plush velvet cloth absorbs and reflects light differently from a gleaming, shiny metal goblet, or the way the intricate, hand-woven patterns of a Persian rug can draw you in with their tactile promise. These details are rarely accidental; they are a fundamental part of the artist's deliberate, masterful craft. For more on this, check out The Definitive Guide to Understanding Texture in Art. In my own work, even when abstract, I strive to create that tactile invitation, that sense of something you want to reach out and experience with more than just your eyes.

- Arrangement: This is the choreography of the still life. The careful placement of objects guides the viewer's eye, creates a sense of harmony or intentional tension, and dictates the overall rhythm of the piece. Think of established compositional principles like the Rule of Thirds, the golden ratio (a timeless proportion found in nature and art), the Rule of Odds (using an odd number of objects to create a more dynamic and visually interesting composition), or using leading lines to draw the viewer deeper into the composition and guide their gaze. Whether the arrangement is deliberately symmetrical for a sense of calm, formality, and balance, or artfully asymmetrical to create dynamic tension and visual movement, every item’s position – its relationship to its neighbors, its scale, and its contribution to the overall shape of the composition – is a profoundly conscious decision. This is where the artist truly constructs their world, establishing a clear focal point to immediately grab attention, or inviting the eye to wander and discover hidden narratives. For a deeper dive into these essential concepts, you might find our guides on the principles of still life composition, Definitive Guide to Composition in Art, and Understanding Balance in Art Composition incredibly insightful. Speaking of arrangement, let's also talk about negative space – the often-overlooked area around and between the objects. It's just as important as the objects themselves, actively helping to define their shapes, create visual breathing room, and contribute to the overall balance and harmony. It’s a delicate, intentional dance between presence and absence, making the viewer's eye move exactly as the artist intended. I often approach my abstract compositions with a similar mindset, arranging shapes and colors like silent dancers on a stage.

- Perspective: This refers to the crucial angle from which the viewer observes the setup, profoundly influencing the sense of depth, space, and realism within the still life. Whether it’s a high vantage point looking down onto a table, an intimate eye-level view, or even a dramatic worm's-eye view looking up, perspective dictates how objects recede or project, adding to the compelling illusion of three-dimensionality on a two-dimensional surface. Artists master techniques like linear perspective (encompassing one-point, two-point, and even multi-point applications) and atmospheric perspective (using haziness, desaturation, and color shifts to subtly suggest distance and depth) to create incredibly convincing depth and spatial relationships. Understanding and manipulating perspective, including the dramatic, often challenging, effect of foreshortening where an object appears compressed due to its angle, is a key skill, and if you're curious about how artists achieve this, our guide on the definitive guide to perspective in art is a must-read. For me, even in abstract art, the sense of perspective, of objects receding or coming forward, is vital for creating a dynamic visual experience. The use of perspective also plays a significant role in establishing the elements of design such as space and form.

It takes a keen eye, endless practice, and a certain kind of profound patience to truly master the art of still life. But the result? A piece that can draw you in, hold your gaze, and make you think about something as simple as a pear with newfound depth and reverence. It's a rewarding challenge, believe me. If you're feeling inspired to try your hand at capturing the essence of everyday objects, remember that sometimes, the most profound statements come from the simplest arrangements. It’s about seeing, not just looking. And who knows, you might discover a hidden talent for bringing inanimate objects to life on your canvas.

To condense these crucial elements, here’s a quick overview of compositional principles in still life:

Compositional Principle | Description | Impact on Still Life |

|---|---|---|

| Balance | The distribution of visual weight within a composition, ensuring no single area feels too heavy or too light. Can be symmetrical (formal) or asymmetrical (dynamic). | Creates a sense of stability or dynamism, guides the viewer's eye evenly or towards a focal point, contributes to overall harmony. |

| Rhythm & Repetition | The use of recurring elements (shapes, colors, textures) to create a sense of movement, flow, and visual interest, leading the eye through the artwork. | Establishes a visual beat, helps to unify disparate objects, prevents the composition from feeling static or disjointed. |

| Emphasis (Focal Point) | Creating a dominant area or object that captures the viewer's attention first, making it stand out from the rest of the composition. | Directs the viewer to the most important element, establishes hierarchy, adds drama and interest, preventing the eye from wandering aimlessly. |

| Unity & Harmony | The feeling that all elements of the artwork belong together, creating a cohesive and aesthetically pleasing whole, where nothing feels out of place. | Ensures the still life communicates a clear, unified message or mood, making the composition feel complete and satisfying. Achieved through consistent style, color, or thematic elements. |

| Contrast | The juxtaposition of opposing elements (light/dark, rough/smooth, large/small, warm/cool) to create visual interest, drama, and define forms. | Adds visual excitement, defines shapes and textures, creates depth and dimension, highlights key features, prevents monotony. |

| Proportion & Scale | The relationship of sizes between elements within the composition and to the overall work. Proportion refers to relative size; scale compares objects to a standard (e.g., human size). | Creates realism or distortion, establishes a sense of depth and spatial relationship, can convey symbolic meaning (e.g., small objects made monumental). |

| Movement | The path the viewer's eye takes through the artwork, often directed by lines, shapes, forms, and colors. Can be implied or actual. | Guides the narrative, encourages exploration of the entire composition, adds dynamism and energy, prevents the scene from feeling entirely static. |

| Variety | The use of diverse elements (shapes, colors, textures, sizes) to prevent monotony and add interest, without compromising unity. | Keeps the viewer engaged, makes the composition visually rich and complex, adds depth and personality to the arrangement. |

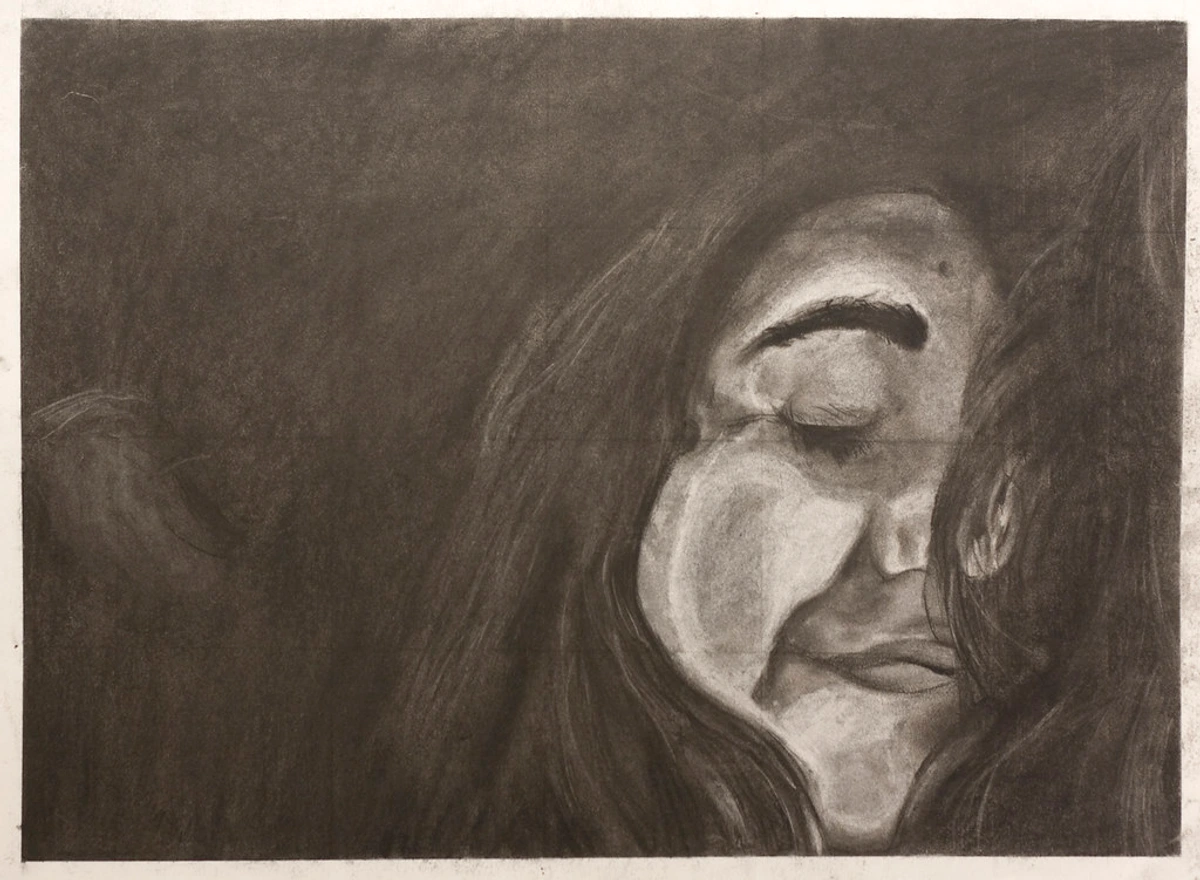

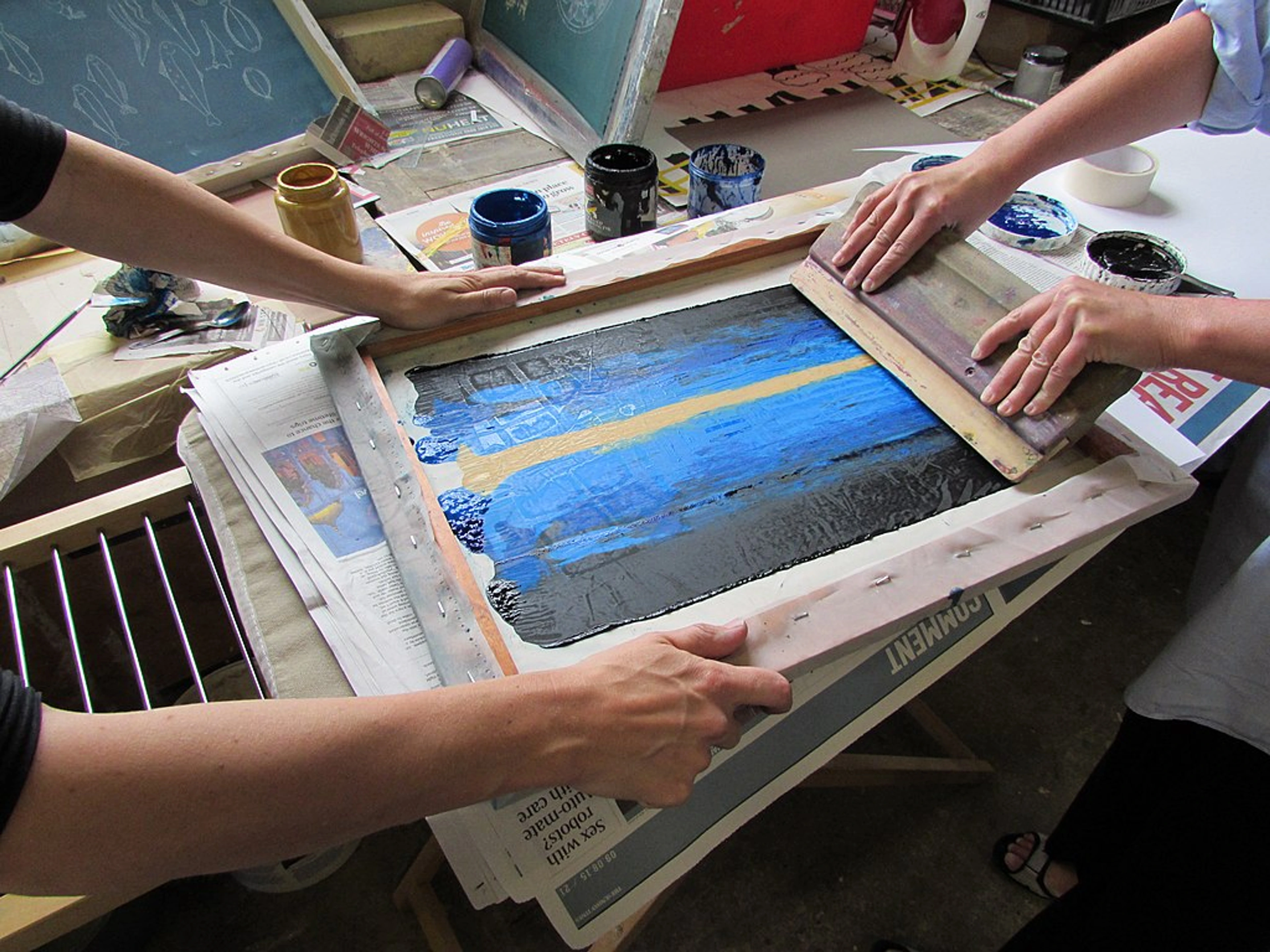

Mediums and Techniques

Still life isn't confined to a single medium; its adaptability is, in fact, one of its greatest strengths. Traditionally, oil paint on canvas or wood panel has been dominant, offering a rich depth of color, unparalleled luminosity, incredibly slow drying times ideal for seamless blending and subtle transitions, and the ability to build up translucent glazes that create incredible depth. But artists also eagerly embrace acrylics, valued for their vibrant, intense colors and much faster drying times, allowing for quick layering, impasto techniques, and bolder, more immediate strokes. Watercolors lend themselves beautifully to delicate washes, transparent effects, and capturing subtle nuances of light and atmosphere, perfect for ephemeral subjects. Beyond paint, pastels (with their soft, painterly quality), charcoal (excellent for dramatic chiaroscuro and texture), and pencil are frequently used for detailed drawings, quick studies, and emphasizing pure form, tone, and texture. Each medium brings its own unique qualities and challenges to the still life, profoundly influencing the mood, visual impact, and the artist's expressive capabilities. I often choose my medium based on the feeling I want to evoke, whether it's the raw intensity of charcoal or the fluid grace of watercolor.

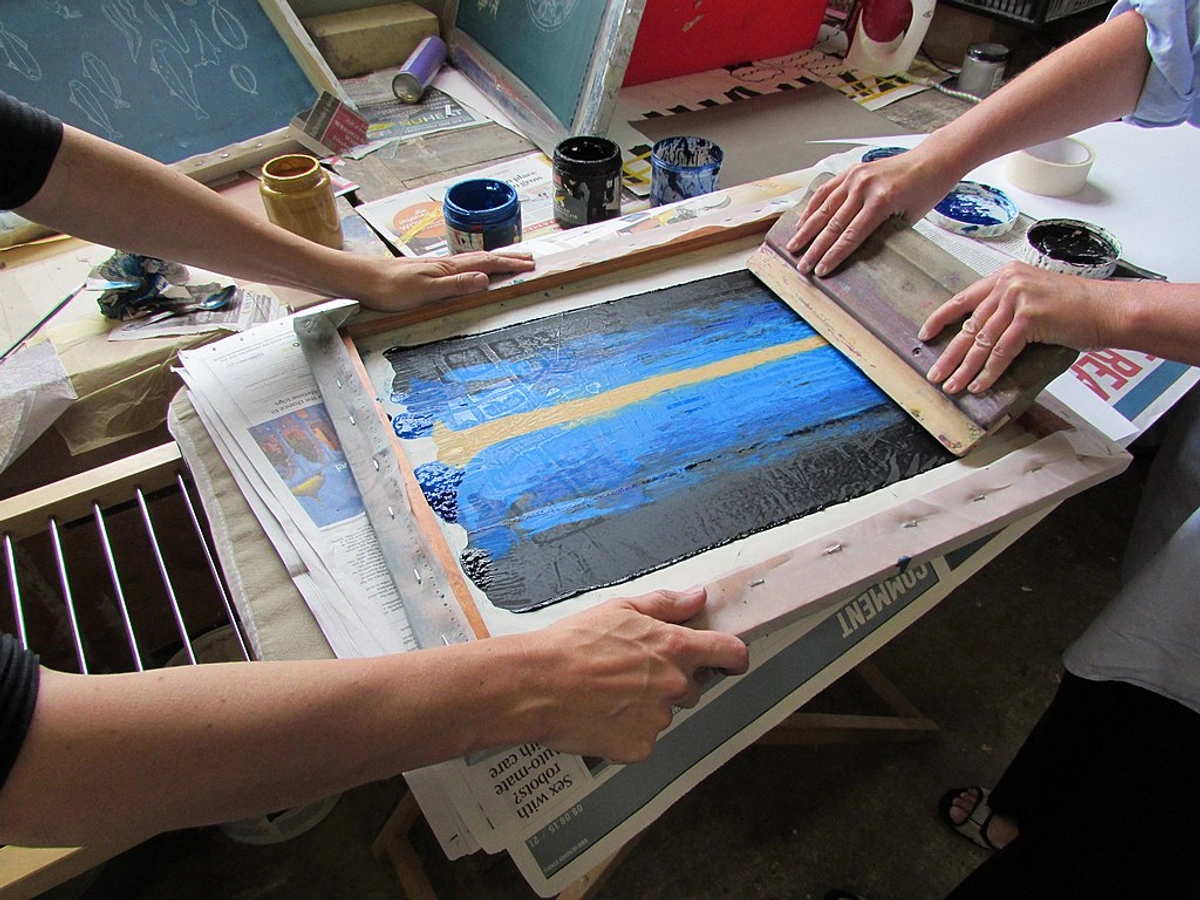

Moreover, the realm of still life extends far beyond traditional painting. Photography has become a powerful medium for still life, allowing artists to capture reality with breathtaking detail or manipulate images to create surreal and conceptual compositions. Sculpture also embraces still life, with artists arranging physical objects in three dimensions, often incorporating found objects or creating intricate assemblages that challenge our perception of everyday items. And in the 21st century, digital art and video installations are opening up entirely new frontiers for still life, allowing for dynamic, interactive, and evolving compositions that reflect our contemporary technological landscape.

The Artist's Process: Setting the Stage

Before even touching a brush, the still life artist engages in a deeply thoughtful, almost meditative, process of selection and arrangement. It's much like being a director staging a highly nuanced play, where every prop, every light cue, and every "actor's" (object's) position is absolutely critical. The objects are often chosen not just for their inherent aesthetic appeal, but for their rich symbolic resonance, their historical context, or simply their unique ability to interact interestingly with light and shadow. Imagine the artist meticulously shifting a single piece of fruit, rotating a seemingly insignificant vase, or adjusting a folds of drapery, all to find that perfect balance, that ideal narrative, that fleeting moment of compositional harmony. They might even make numerous preliminary sketches or conceptual studies to explore different possibilities before committing to the final setup. This preparatory stage is where the magic truly begins, transforming a mere collection of disparate items into a cohesive, meaningful whole. It's a profound, silent conversation between the artist's vision, their emotional intent, and the inherent qualities of the objects themselves. This is where the initial spark of inspiration is fanned into a carefully constructed, compelling visual statement, ready to tell its story. I actually find this stage almost as fulfilling as the act of painting itself; it's the genesis of the visual narrative.

Perhaps you're ready to pick up a brush yourself? If you're thinking of getting started, remember that the right tools can make all the difference. Check out /buy for art supplies to get you started on your own creative journey, or perhaps you'll find a piece that speaks to your soul and begs to be part of your collection. After all, what better way to appreciate this art form than by bringing a piece of it into your own space?

Still Life Today: Breaking Boundaries and Contemporary Relevance

Is still life still relevant in our fast-paced, digital world? Absolutely! In fact, I'd argue it's more relevant than ever. Contemporary artists are constantly pushing the boundaries of what a still life can be, using new media and addressing modern concerns. It's no longer just confined to oil on canvas; it's a dynamic, ever-evolving genre that reflects our current zeitgeist, from fleeting digital images to monumental installations.

Think about the explosion of meticulously styled food photography on social media – isn't that, at its heart, a modern form of still life? Or conceptual installations that utilize everyday objects to comment on pressing contemporary issues like consumerism, waste, or identity. Even performance art can incorporate still life elements, where arranged objects become silent witnesses or active participants in a fleeting narrative. The medium may change, but the core intention of highlighting the significance of objects endures.

Artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, while primarily known for his raw, powerful Neo-expressionism, frequently incorporated still life elements into his collaborations and solo works, transforming mundane objects into bold, often unsettling, symbolic statements that commented on culture, race, and power. Even Andy Warhol, the pop art titan, created numerous still lifes, transforming everyday products like Campbell's soup cans, Brillo boxes, and even dollar signs into iconic art, blurring the lines between commercialism and fine art and questioning consumer culture. Beyond them, artists like Jeff Koons (whose monumental, often shiny, sculptures of everyday objects challenge notions of taste and luxury), and Damien Hirst (whose Natural History series features animals preserved in formaldehyde, confronting mortality and the ephemeral nature of life), elevate everyday objects to high art, often with a cheeky wink, a provocative statement, or a profound, sometimes disturbing, meditation on life and death. And don't forget the incredible hyperrealist still lifes that challenge photography itself, achieving an almost unsettling level of detail! This, to me, is still life at its most provocative, constantly forcing us to re-evaluate what we consider 'art' and 'object.' It's a vibrant, often rebellious, conversation about our material world, pushing boundaries in exciting and sometimes uncomfortable ways.

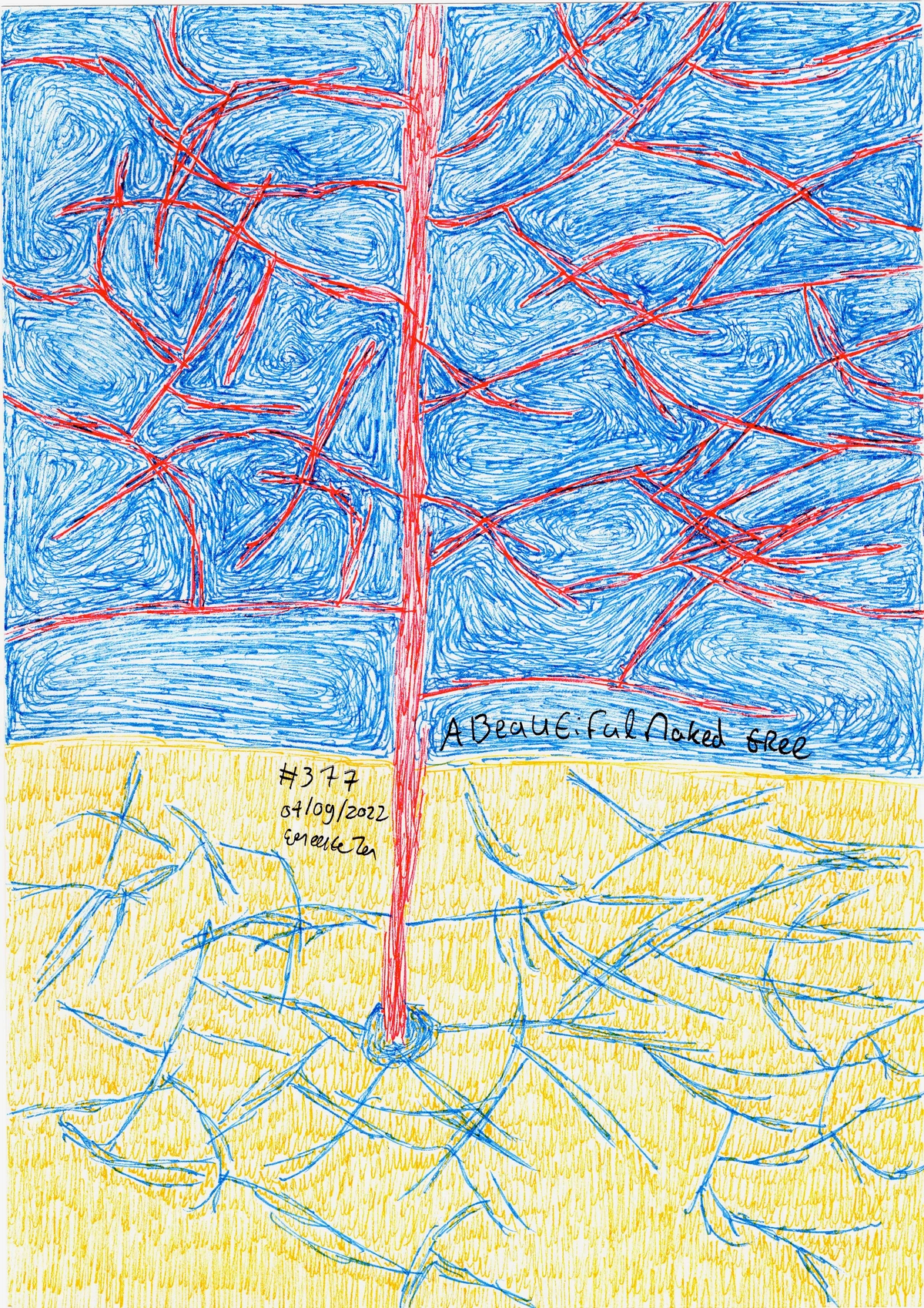

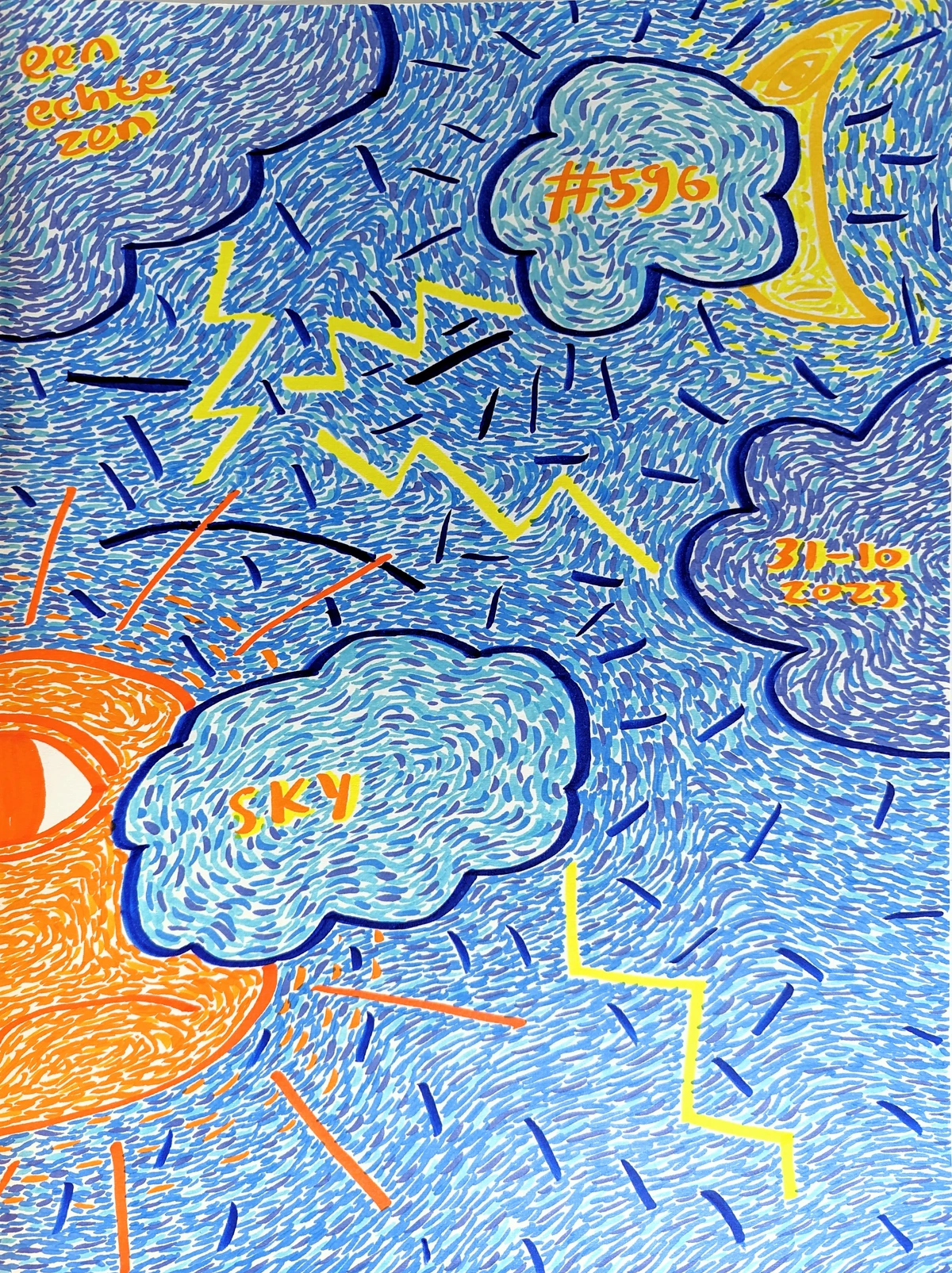

And when I consider the playful, yet profoundly thoughtful way Zen Dageraad Visser approaches abstract art, or finds beauty in bold simplicity and compelling composition, it reminds me that the spirit of still life – that intrinsic drive to find significance in arrangement and to extract meaning from the inanimate – is not only alive and well, but thriving in unexpected corners of the art world. It's about seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary, a lesson I try to carry into my own practice every single day. For more on how artists break boundaries, consider exploring the definitive guide to the history of abstract art to see how those principles apply across movements.

Even a simple photo of your breakfast, carefully arranged, carries the echo of centuries of artists trying to capture a moment, tell a story, or find beauty in the mundane. The art of still life painting is truly boundless. It reminds us that creativity isn't confined to grand gestures, but thrives in the thoughtful observation of our immediate surroundings.

Embracing New Technologies and Media

Beyond traditional painting and photography, contemporary artists are enthusiastically experimenting with digital art, video installations, and even augmented reality to create entirely new forms of still life. Imagine a dynamic digital still life that changes and evolves with the viewer's presence, or a virtual reality experience that immerses you within a meticulously constructed, highly symbolic arrangement, allowing for deep interaction. Augmented reality overlays that reveal hidden symbolic layers in a physical arrangement are no longer science fiction, but a tangible reality, adding dimensions of meaning. And yes, even the burgeoning, often tumultuous, world of AI art and NFTs – while I remain healthily skeptical of some of the hype and speculative bubbles, I do observe a fascinating, underlying impulse towards generated 'still' compositions. These innovations, regardless of their commercial viability, continue to push the boundaries of the genre, proving its incredible adaptability and enduring relevance in the 21st century. It's a testament to the fact that the core idea – finding profound meaning and beauty in objects – is timeless, regardless of the tools we use to express it. It reminds me that the human drive to create and find meaning is incredibly resilient, adapting to any new technology thrown its way.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

I get asked a lot of questions about still life, and it's always fun to clear up some common misconceptions or dive deeper into areas people are curious about. Given how broad and adaptable this genre is, it's natural to have questions! Here are a few I hear regularly, along with my take on them:

What is the origin of the term 'still life'?

The English term 'still life' is derived from the Dutch word stilleven, which became prominent in the 17th century. The French nature morte (dead nature), the Italian natura morta, and the German Stilleben all carry similar connotations. These terms emerged as the genre solidified its independent status, clearly distinguishing it from 'living' subjects like portraits or dynamic scenes. It's a name that, while perhaps a bit understated, perfectly encapsulates the genre's focus on inert objects and their quiet, often profound, presence. It's fascinating how a concept can be so universally understood despite variations in its linguistic roots.

What are some common still life subjects?

Honestly, almost anything can be a still life subject! Traditionally, you'd see a lot of food items (fruits, vegetables, bread, cheese, game), flowers, household items (vases, jugs, glassware, pottery, books, musical instruments), and symbolic objects (skulls, candles, hourglasses, coins, jewelry). But in contemporary still life, the possibilities are truly endless. Artists use everything from discarded consumer goods and industrial waste to digital avatars and virtual objects to make their statements. The key is the artist's intent and arrangement, transforming the mundane into the meaningful. I've even seen still lifes made of old tech gadgets, commenting on planned obsolescence – it just goes to show how adaptable the genre is!

Can still life be abstract?

Absolutely! While historically still life often emphasized realism, modern and contemporary artists have fully embraced abstraction within the genre. An abstract still life might focus on the interplay of shapes, colors, and textures derived from objects, rather than their literal representation. Think of a Cubist still life that breaks objects into geometric forms, or a vibrant abstract expressionist piece that captures the energy of an arrangement rather than its precise likeness. The core intention – to reflect on the meaning or aesthetic qualities of inanimate objects – remains, even when the visual language becomes abstract. Indeed, much of my own work, while abstract, still draws inspiration from the interplay of light and form found in still life!

How do still life artists achieve realism?

Achieving realism in still life is a profound technical challenge, requiring immense skill and observation. Artists typically focus on meticulous rendering of form and volume through precise drawing, masterful use of light and shadow (think chiaroscuro and tenebrism!), and accurate depiction of textures (the sheen of glass, the softness of velvet, the rough skin of a fruit). They also employ techniques like linear perspective to create believable depth and foreshortening to make objects appear to recede or project convincingly. It's a painstaking process of observation, analysis, and execution, all aimed at creating the illusion of three-dimensional reality on a two-dimensional surface. It's a testament to human perception and dexterity, truly a marvel to behold.

What is the significance of the artist's personal touch in still life?

The artist's 'personal touch' – their unique perspective, emotional investment, and stylistic choices – is absolutely paramount in still life, transforming mere depiction into profound expression. It's the artist's worldview, their aesthetic sensibility, and their individual narrative that imbues inanimate objects with meaning. A personal touch might manifest in unconventional arrangements, a distinctive color palette, a particular brushstroke, or a subtle symbolic choice that reflects their inner world or commentary on society. It's what differentiates one artist's fruit bowl from another's, making it a unique and irreplaceable statement. For me, it's about pouring a piece of myself into the quiet conversation between objects, making them resonate with a human truth.

What is the primary purpose of still life art?

Initially, still life served decorative and educational purposes, often conveying moral or religious messages. Think of those ancient Egyptian tomb paintings, intended to provide for the afterlife, or the Dutch Golden Age Vanitas paintings with their stark moral lessons. Today, its purpose has broadened significantly to include aesthetic appreciation, personal expression, social commentary, and exploring formal elements like light, color, and composition. Ultimately, I believe its enduring purpose is to invite viewers to pause, look closer, and find significance, beauty, and often profound meaning in ordinary objects, urging a deeper, more mindful connection with the material world. It's a call to mindfulness, if you will, a quiet meditation in a chaotic world. Moreover, it's a remarkably powerful vehicle for artistic experimentation, allowing artists to meticulously control every single aspect of the composition to explore formal elements like light, color, and texture, demonstrate technical mastery, and convey deeply personal expression. It's about revealing the hidden narratives that objects carry, and that, to me, is profoundly important.

What is a 'memento mori' and how does it relate to still life?

Ah, 'memento mori'! This Latin phrase translates to "remember that you must die," and it's a powerful artistic theme that has deep roots in still life, particularly in the Vanitas paintings of the Dutch Golden Age. A memento mori is any artistic or symbolic reminder of the inevitability of death. In still life, this often takes the form of objects like skulls, extinguished candles, wilting flowers, bubbles, or hourglasses – all chosen to remind the viewer of the transient nature of life, the fleetingness of earthly pleasures, and the ultimate certainty of mortality. While Vanitas is a sub-genre within still life that frequently employs memento mori, the concept itself can appear in broader art forms, always serving as that sober, yet beautiful, contemplation of human existence. It's a powerful artistic embrace of our own finite existence, a beautiful paradox within the 'stillness' of the art.

It’s a deceptively simple premise that allows for infinite complexity and meaning. The unparalleled ability to manipulate every element within the frame gives the artist immense control to express the most subtle nuances or make the boldest statements. This deliberate control is what truly differentiates it from the vastness of a landscape or the unpredictable, fleeting nature of a living portrait, offering a unique artistic laboratory for profound contemplation.

What are some famous still life paintings I should know?

Oh, where to begin! The history of still life is rich with masterpieces. Here are a few iconic works that come to mind and are truly worth exploring:

- "Still Life with Basket of Fruit" (c. 1599) by Caravaggio: A groundbreaking early still life, celebrated for its intense realism and dramatic lighting, capturing the fruit with an almost tactile presence.

- "The Ray" (c. 1728) by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin: A powerful and almost unsettling piece depicting a ray fish, masterful in its rendering of texture and its raw, unsentimental portrayal of a kitchen scene.

- "Still Life with Apples and Oranges" (c. 1895-1900) by Paul Cézanne: A quintessential example of Cézanne's revolutionary approach, where he deconstructs form and explores multiple perspectives, paving the way for Cubism.

- "Sunflowers" (various versions, 1888-1889) by Vincent van Gogh: More than just flowers, these vibrant and impassioned works pulse with the artist's intense emotional energy and unique vision.

- "Still Life with Guitar" (1912) by Pablo Picasso: A prime example of Cubist still life, fracturing and reassembling objects to challenge traditional perception and represent multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

- "The Treachery of Images" (1929) by René Magritte: The iconic painting of a pipe with the caption "Ceci n'est pas une pipe," which profoundly questions the relationship between an object and its representation.

- "Campbell's Soup Cans" (1962) by Andy Warhol: A defining work of Pop Art, elevating everyday consumer products to the status of high art and commenting on mass production and commercialism.

- "Still Life with a Herring" (1643) by Pieter Claesz.: A classic Dutch Golden Age Ontbijtje, showcasing meticulous detail, humble objects, and often subtle Vanitas symbolism.

These are just a few, but each one offers a unique lens into the profound and diverse world of still life art!

What are some common challenges in creating still life art?

Ah, the challenges! It might seem deceptively simple to paint a bowl of fruit, but mastering still life demands incredible skill. Artists often grapple with accurately rendering form and volume on a two-dimensional surface, capturing the subtle nuances of light and shadow, and achieving convincing textures. Beyond technique, the conceptual challenge lies in creating a compelling narrative or symbolic meaning from inanimate objects, making them 'speak' without words. It also requires immense patience for meticulous observation and arrangement. It's a true test of an artist's foundational abilities, believe me. I can tell you from experience, getting that perfect reflection on a glass, or the subtle bruise on an apple, takes an incredible amount of focused observation!

Are there different cultural interpretations of still life?

Absolutely! While the Western tradition, particularly the Dutch Golden Age, often dominates discussions of still life, the impulse to depict inanimate objects with meaning is universal. Different cultures have imbued still life with unique interpretations, reflecting their distinct philosophies, spiritual beliefs, and societal values.

- East Asian Traditions: In Chinese and Japanese art, still life elements often appear in bird-and-flower paintings (kachō-ga), where specific flora and fauna carry seasonal, poetic, or auspicious meanings. For example, bamboo symbolizes resilience, while chrysanthemums represent nobility. These are often about harmony with nature and the cyclical passage of time.

- Ancient Egypt: As we discussed, still lifes in tombs were practical-magical provisions for the afterlife, not merely decorative.

- Pre-Columbian Art: While not a standalone genre, objects with symbolic or ritualistic importance were often depicted in murals or pottery, imbuing them with spiritual power.

- Islamic Art: Due to aniconic traditions, still life often focused on abstract patterns, calligraphy, and elaborate depictions of textiles or architectural elements, valuing aesthetic beauty and mathematical precision.

These diverse interpretations highlight that while the core concept of still life is universal, its cultural expressions are wonderfully varied, offering a rich tapestry of human meaning-making.

Can still life incorporate living elements?

This is a fun one! While the core definition of still life (nature morte - dead nature) focuses on inanimate objects, it's not a strict, unbending rule. Many historical still lifes include elements that were once living but are now inert – think dead game, cut flowers, or fruit. However, some artists do incorporate living elements like a live insect, a small bird (though less common in painting, more in conceptual art), or even a human hand reaching into the composition. These are often used to introduce a dynamic element, a contrast to the stillness, or to add a layer of narrative or symbolism related to life and death. So, while typically focused on the inanimate, the genre is flexible enough for artists to play with this boundary. It's where the 'still' becomes surprisingly dynamic, challenging our expectations.

How does still life differ from portrait or landscape painting?

That's a great question! While all these genres depict subjects, their focus is distinct. Portrait painting centers on the likeness and personality of a living human or animal, often aiming to capture their emotional state or social standing. Think of a Rembrandt portrait, delving deep into the sitter's soul. Landscape painting focuses on natural scenery, capturing expansive views and atmospheric conditions, seeking to evoke the grandeur or tranquility of the natural world. Still life, in contrast, deliberately arranges and depicts inanimate objects. The artist has complete control over the subject matter and its arrangement, allowing for intense focus on composition, symbolism, and formal elements in a way that is less possible with living subjects or vast outdoor scenes. It's a controlled laboratory for artistic expression, in a sense, offering a unique opportunity for introspection and meticulous design. This precise control over every element, from lighting to arrangement, is what allows still life artists to delve so deeply into formal exploration and symbolic narratives.

What is the significance of the table or surface in still life?

The table or surface is far from incidental; it's a crucial, often unsung, element in still life composition! It acts as the stage upon which the 'drama' of the objects unfolds. Its texture, color, and angle can profoundly affect the mood and realism of the painting. A rich, draped velvet cloth, for instance, might signify luxury and depth, while a rough wooden table could evoke humility and domesticity. The surface also plays a vital role in establishing perspective and depth, guiding the viewer's eye into the arrangement. It's where objects sit, cast shadows, and reflect light, all contributing to the illusion of a tangible, three-dimensional world.

That's a great question! While all these genres depict subjects, their focus is distinct. Portrait painting centers on the likeness and personality of a living human or animal, often aiming to capture their emotional state or social standing. Think of a Rembrandt portrait, delving deep into the sitter's soul. Landscape painting focuses on natural scenery, capturing expansive views and atmospheric conditions, seeking to evoke the grandeur or tranquility of the natural world. Still life, in contrast, deliberately arranges and depicts inanimate objects. The artist has complete control over the subject matter and its arrangement, allowing for intense focus on composition, symbolism, and formal elements in a way that is less possible with living subjects or vast outdoor scenes. It's a controlled laboratory for artistic expression, in a sense, offering a unique opportunity for introspection and meticulous design.

What are some common themes found in still life paintings?

Common themes include the transience of life (the classic Vanitas, reminding us of mortality), the abundance of nature (celebrating harvests and natural beauty), human endeavors (e.g., scholarly pursuits represented by books, or pleasures like music), the beauty of everyday objects (elevating the mundane), and cultural or historical context (reflecting societal values and possessions of a specific era). Modern still lifes might explore themes of consumerism, identity, environmental concerns, social justice, or critiques of contemporary society. The beauty is that the genre is so flexible, artists can truly use it to comment on almost anything that matters to them, often reflecting the zeitgeist of their time. For example, contemporary still lifes might explore themes of consumerism, critiquing our relationship with material possessions, or address environmental concerns through arrangements of discarded items, like a broken plastic bottle next to a wilting flower. They can also delve into issues of identity and social justice by using culturally specific objects, or comment on political statements by arranging symbolic objects related to current events. It's a surprisingly versatile canvas for profound ideas, adapting its voice to the issues of the day, making it as relevant now as it was centuries ago.

What materials are typically used in still life art?

While still life can be created with virtually any artistic medium, traditionally, oil paint on canvas or wood panel has been dominant, especially from the Dutch Golden Age through to the present day. The richness and depth of oil paint lend themselves beautifully to capturing the textures and luminosity of still life subjects. However, artists also frequently use acrylics (which offer vibrant colors and faster drying times), watercolors (for delicate washes and transparent effects), pastels, charcoal, and pencil for drawings and studies. Each medium brings its own unique qualities to the still life, influencing the mood and visual impact. I've found that the medium itself can almost become part of the narrative, contributing to the overall feel of the piece.

In contemporary art, you'll see still life expressed through an incredibly diverse range of media. This includes photography (from traditional darkroom prints to sophisticated digital manipulation and composite images), sculpture (where objects are physically arranged in three dimensions, sometimes monumental in scale), mixed media (combining various materials and techniques within a single piece), digital art, video art, and even large-scale installations using real objects that viewers can walk around or interact with, becoming part of the artwork themselves. The choice of medium often profoundly impacts the final message and aesthetic, adding yet another layer to the artist's intentionality and expressive possibilities. It's truly a vast and ever-expanding playground for artistic experimentation! I find it liberating how artists today are unafraid to blur the lines between traditional and new media to tell their stories.

How has still life evolved in the 21st century?

The 21st century has seen still life explode into a truly boundless genre, fueled by new technologies and a continuing artistic desire to interpret our material world. We're witnessing a proliferation of digital still life, created using software and virtual tools, blurring the lines between physical and digital. This can include anything from hyper-realistic 3D renderings to abstract algorithmic compositions. Installation art frequently employs still life principles on a grand scale, arranging objects in gallery spaces to create immersive, conceptual experiences that might comment on consumerism, waste, or memory. And as I mentioned earlier, the pervasive influence of social media with its meticulously curated 'flat lays' and food photography, echoes the historical impulse of still life, democratizing the act of finding beauty and meaning in arranged objects. Furthermore, performance art can sometimes incorporate still life elements, where arranged objects become silent witnesses or active participants in a fleeting narrative. It's a dynamic, exciting time for the genre! I find it fascinating how the core human impulse to arrange and find meaning in objects adapts so readily to new platforms and technologies, from a Renaissance painting to an Instagram feed.

Who are some famous still life artists?

Key figures in the illustrious history of still life include Floris van Dijck, Willem Kalf, and Jan Davidsz. de Heem (the undeniable masters of the Dutch Golden Age), Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (the quiet genius of the 18th century), Paul Cézanne (the revolutionary Post-Impressionist, often considered the undeniable father of modern still life), Henri Matisse (Modernism's vibrant colorist, whose vibrant still lifes sang with pure, unadulterated color), and Salvador Dalí (the audacious Surrealist). Even Pablo Picasso created iconic still lifes during his groundbreaking Cubist period, deconstructing reality itself. Modern masters like Giorgio Morandi, with his quiet, contemplative, and almost spiritual arrangements of bottles and boxes, also stand out for their profound focus on form and color.