Texture in Art: Actual vs. Implied, Psychological Impact & Sensory Depth

Unravel the profound power of texture in art. Explore tangible actual textures and the masterful illusions of implied texture. Discover how artists evoke emotions, create depth, and forge deep sensory connections across diverse styles, from impasto to digital art, and even in abstract compositions, inviting a truly haptic experience.

Texture in Art: A Deep Dive into Sensory Experience

I often find myself wondering if we, as humans, are simply a symphony of senses, constantly trying to make sense of the world around us. Touch, I believe, is arguably our most fundamental, primal sense, don't you think? The smooth coolness of a ceramic mug, the rough bark of an old tree, the almost-too-soft fur of a sleeping cat. But when it comes to art, we often get so fixated on what we see that we forget about what we feel, or more accurately, what we imagine we feel. This deep dive isn't just about observation; it’s about activating our haptic memory – that internal library of touch sensations – allowing the artwork to create an almost physical echo in our minds. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll journey through the fascinating world of texture in art, exploring its tangible actual and illusory implied forms, uncovering its profound psychological impact, and revealing why it's such a fundamental element in connecting with art on a deeper, more sensory level. As an artist, I aim to pull back the curtain on this often-overlooked element, showing you how artists manipulate surfaces to evoke powerful responses and how you can, in turn, experience art more fully, even within the vibrant, often abstract, compositions I create.

What is Texture in Art? Actual vs. Implied

I remember once, as a kid, I saw a painting of a rusty old car. I swear I could feel the grit and flaking paint just by looking at it. My mum had to physically pull my hand away before I smeared it all over the canvas – a memory that perfectly encapsulates the magic of implied texture. Texture in art isn’t merely about what’s physically there, but crucially, what our minds perceive to be there. It's about how the surface quality of an artwork invites us in, activating our haptic memory even when we can't physically touch it. This brings us to the two main types of texture in art:

Actual Texture: The Tangible Truth

Actual texture is, well, pretty straightforward, isn't it? It's the physical surface of the artwork itself – the bits that stick out, the parts you'd actually feel if you were allowed to touch it (which, let's be honest, you usually aren't, and for good reason – sorry, mum, and apologies to any exasperated museum guards out there!). Think of the thick, luscious dollops of paint that build up on a canvas, a technique known as impasto. Artists like Vincent van Gogh were masters of this, making their sunflowers almost leap out at you, physically demanding attention. The sheer audacity of applying paint so thickly, letting it dry into mountainous ridges, transforms a flat surface into a topographical landscape.

And then there's the truly tactile experience of mixed media, where artists literally glue or attach different materials to their surface. We're talking sand, fabric, bits of newspaper, even broken pottery. Consider the intricate woven patterns and varied yarn thicknesses in fiber art, creating surfaces that beg to be explored by touch. Sculptors, too, are masters of actual texture, shaping raw materials like clay, stone, wood, or metal to have inherent surface qualities. Think of the raw grit of unprimed canvas, the subtle tooth of handmade paper, or the distinctive grain of natural timber – each material carries its own tactile story. From polished smoothness to rugged abrasiveness, these inherent qualities are integral to the artwork's identity, inviting a multi-sensory engagement that goes beyond mere sight. Sometimes, artists even choose textures that are deliberately abrasive, jagged, or unsettling, aiming to evoke unease or a sense of struggle, challenging our innate desire for comfort. This physical manipulation not only enhances the visual plane but also creates a tangible, three-dimensional presence, inviting more than just the eye to explore.

https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/53064827119_1b7c27cd96_b.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

Take a look at the incredible textures created by Jean-Michel Basquiat, where the raw energy of his brushstrokes and layered materials practically jump off the canvas, telling a story of intense creative process. The deliberate roughness and accumulation of materials here don't just add physical depth; they narrate a chaotic, vibrant interior world.

https://heute-at-prod-images.imgix.net/2021/07/23/25b32e7b-0659-4b35-adfe-8895b41a5f89.jpeg?auto=format, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

While actual texture offers a direct, physical engagement, artists also possess a remarkable ability to suggest texture, creating illusions that are just as powerful, entirely through visual means.

Implied Texture: The Illusionists' Art

Now, this is where things get really clever, almost like a visual magic trick. Where actual texture gives you the literal bumps, implied texture gives you the suggestion of how something feels, created entirely through visual means. No actual bumps or ridges, just pure, masterful illusion. It’s what makes you think that painted silk dress is soft and flowing, or that a depicted stone wall is rough and unyielding, all without a single millimeter of physical depth. Artists achieve this through a myriad of techniques, masterfully playing with light, shadow, line, color temperature, and value to create convincing illusions. For instance, short, choppy brushstrokes or sharp, angular lines might convincingly suggest the harshness of a rock face or the prickliness of thorns. Conversely, soft, blended gradients and flowing, continuous lines can beautifully mimic the smooth, cool feel of glass or the delicate drape of silk. It’s also fascinating how artists use color temperature to play with our haptic perception. Warm colors (reds, oranges, yellows) tend to advance and can often suggest a rougher, more immediate texture, like sun-baked earth or the fiery glow of molten metal, perhaps because they evoke associations with heat and dense materials. Cool colors (blues, greens, violets), on the other hand, recede and often evoke smoother, more distant, or fluid sensations, like calm water or a cool metal surface, linking to our perception of cold and light materials. Similarly, manipulating value – the lightness or darkness of a color – can create compelling illusions: a stark contrast between dark shadows and bright highlights can convey extreme roughness or deep crevices, while a gradual, subtle shift in value suggests smoothness and gentle curves.

Think about how a painter uses short, choppy brushstrokes to suggest rough fabric, or long, smooth ones for glass. Or how a skilled draughtsman can make a fluffy cloud feel, well, fluffy, just with delicate lines and shading. Cross-hatching, stippling (like those incredibly patient pointillist artists, whose unwavering focus must have been legendary, or maybe they just liked repetitive tasks – I get it!), and varying line weights are all tools in the illusionist’s toolkit. These techniques also contribute to an artwork's visual weight: areas with more perceived texture can draw the eye and feel 'heavier,' almost physically anchoring elements and creating a powerful sense of depth and perspective on a flat canvas, pulling elements forward or pushing them back within the composition. It’s like how a richly textured, dark area might feel more substantial than a smooth, light one, subtly guiding your gaze around the piece.

https://live.staticflickr.com/2871/13401855525_81707f0cc8_b.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

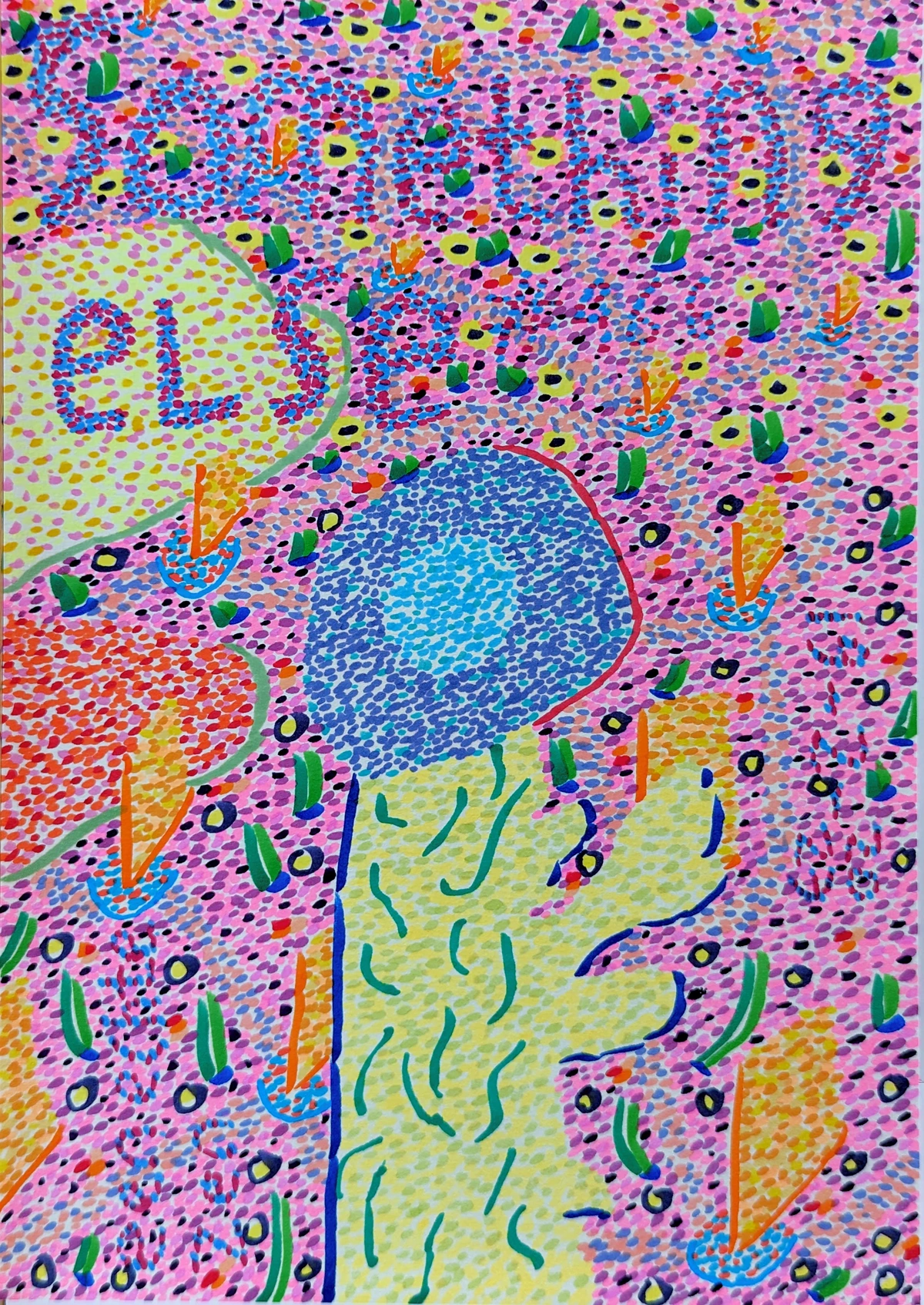

Even in abstract compositions, implied texture can play a crucial role, creating visual depth and interest where there might not be physical substance, almost tricking your eye into perceiving layers that aren't actually there. It's a testament to the artist's ability to manipulate perception itself. How often do you find yourself 'feeling' a texture that isn't physically there when looking at a painting?

Why Texture Matters: Beyond the Surface

So, why should we, as viewers (or as artists, for that matter), even care about texture? Beyond the sheer technical brilliance, texture does something profound: it pulls us in, making the artwork a tactile experience even from a distance. It adds a layer of sensory richness that transcends mere observation, engaging our imagination and haptic memory. And it's not just about what you feel; texture is a master illusionist for depth and perspective in two-dimensional art, too. By manipulating the perceived roughness or smoothness, artists can make elements appear to advance or recede, creating a profound sense of space on a flat surface. It can also subtly influence our perception of an artwork's age or authenticity – a beautifully preserved, smooth surface might suggest timelessness, while a cracked, weathered texture can hint at a rich history or vulnerability.

Psychologically, texture has a deep, often subconscious impact. Our brains are wired to associate certain tactile qualities with specific emotions or states. Rough, jagged textures might subtly evoke feelings of anxiety, age, struggle, or even discomfort and unease, triggering a primal sense of caution. A gnarly, uneven surface, for instance, might echo the challenges of life, the passage of time, or even a sense of decay and rawness. Conversely, smooth textures can promote calmness, sophistication, purity, or even a sense of comforting predictability – the sleek, cool surface of polished marble might suggest control and detached perfection, or perhaps even artificiality. This is why, in my own work, I often use texture not just for visual interest, but to guide the viewer’s emotional response, creating a specific feeling I want to convey. For example, in a piece like 'Urban Decay', I intentionally layered thick, crumbling textures, mixing sand with heavy acrylics, to evoke the sense of crumbling infrastructure and forgotten stories, aiming for a visceral feeling of struggle and resilience.

Texture also plays a fascinating role in influencing the perceived temperature of an artwork. Rough, highly textured surfaces can visually feel warmer, almost radiating an internal heat, perhaps because they absorb light differently or remind us of natural, organic materials. Conversely, smooth, reflective surfaces often feel cooler, reminiscent of glass, metal, or ice.

And this brings us to the subtle, powerful interplay between actual and implied texture. Sometimes, an artist might use actual texture (like thick impasto) to emphasize an implied texture (like a rough fabric), doubling down on the sensory message. Other times, they might create an implied texture (a silky drape) on a surface that has a subtle actual texture (the grain of the canvas), creating a dynamic tension or adding another layer of visual deception. It's a nuanced interplay where one can amplify, contradict, or enhance the other, adding depth and narrative complexity.

A heavily textured piece can feel raw, immediate, almost aggressive, demanding your attention and making you want to reach out. Conversely, a smooth, polished surface might convey calm, precision, or even a serene, almost detached beauty. It evokes emotions, tells stories without words, and creates a powerful sense of place or character. It's like the subtle nuances in someone's voice – it changes the entire meaning of what's being said, adding layers of interpretation and emotional resonance. Texture is not just about what you see; it's about what you feel with your eyes, and then with your mind. It transforms a passive viewing experience into an active, almost haptic, exploration, making the art personal and unforgettable. Moreover, texture can offer a unique entry point for individuals with visual impairments, allowing them to engage with art through touch where allowed, reaffirming its primal connection to our senses. How does texture speak to your inner self, creating echoes of touch in your mind?

Texture Across Artistic Styles: A Historical Perspective

Texture is a universal language in art, consistently reinterpreted across every style and era. It's a testament to the fact that artists, regardless of their philosophy, inherently seek to engage our senses beyond simple representation. How texture is used can also vary significantly across cultures, with some traditions emphasizing highly ornate, tactile surfaces for spiritual connection, while others prioritize smooth, meditative forms. The historical evolution of texture's prominence offers a fascinating journey.

Consider early art forms: in Gothic sculpture, intricate carvings created highly tactile surfaces, designed to be felt as much as seen, drawing worshippers closer to sacred narratives. Later, masters like Michelangelo, even when aiming for idealised forms, deliberately varied the texture of marble – from the polished sheen of skin to the subtly rough drapery of garments, or even the intentionally 'unfinished' surfaces that highlight the struggle of the stone, giving his works a raw, emerging quality. Renaissance frescoes, while seemingly flat, often employed subtle fresco techniques to give the illusion of texture in drapery or architecture, aiming for a refined, idealised reality. Moving into the Baroque period, artists like Caravaggio used dramatic chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) to create a palpable sense of three-dimensionality and implied texture in his figures' skin and fabrics, making them feel startlingly real and present. Later, Romantic painters like Caspar David Friedrich captured the rugged, untamed textures of nature – jagged mountains, dense forests – evoking a powerful sense of awe and sublimity. Then, Impressionists like Claude Monet, with their visible, broken brushstrokes, used texture to capture the fleeting quality of light and atmosphere, making you feel the wind ripple across a field of poppies. Their focus wasn't just on the subject, but on the feel of the moment, a direct invitation to sensory experience.

![]()

https://www.rawpixel.com/image/547292, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

On the other hand, Abstract Expressionists, with their dramatic gestures and experimental application, used texture as a direct expression of emotion and raw energy. Think of Willem de Kooning's agitated surfaces or Jackson Pollock's splattering and dripping paint to create surfaces that are a visceral testament to the artist's intense physical engagement with the canvas. Even minimalist artists, who might seem to eschew complexity, often pay meticulous attention to the subtle textures of their chosen materials – the cool sheen of metal, the inviting grain of wood, the perfectly smooth coolness of a pristine, prepared surface. Here, texture speaks volumes through its very restraint, highlighting the inherent qualities of the material itself.

In printmaking, texture is fundamental: the deep bite of an etching needle into a copper plate creates raised lines that you can feel on the finished print, while the distinct grain of a woodcut block leaves its unique textural signature, whether rough or smooth. Similarly, in ceramics and textile art, artists manipulate materials to achieve specific tactile experiences. In ceramics, glazes can result in glossy, iridescent, or matte, almost powdery surfaces, while the hand-thrown nature of a pot often leaves subtle ridges. Textile artists use diverse weaving patterns, knotting techniques, and yarn thicknesses to create highly varied, intricate surfaces – from the rough, natural feel of burlap to the luxurious softness of silk tapestry, each inviting a different kind of touch. What historical or cultural uses of texture in art do you find most intriguing?

Texture Beyond Traditional Media

But the dance of texture isn't confined to traditional canvases and carved stone. It spills over into almost every creative discipline, proving its adaptability and fundamental importance in engaging our senses.

In photography, light and shadow are the artist's primary tools for revealing or flattening textures, making a craggy rock face appear rugged and ancient or a silk dress luminous and flowing. A skilled photographer can make you feel the sharp edge of a shadow or the softness of diffused light, all through visual manipulation. Digital artists and 3D modelers expertly simulate textures, using sophisticated software to create hyper-realistic surfaces or fantastical, impossible tactility in everything from video games to animated films. Think of the incredible detail in CGI, where every pore and wrinkle is rendered to perfection, engaging our haptic memory even on a screen, blurring the lines between reality and illusion. Even in the ephemeral realms of sound art or interactive digital art installations, while not physically touchable, the quality of sound (smooth, jarring, layered) or the projection of light can evoke a powerful sense of perceived texture, creating an immersive, multi-sensory experience that engages our haptic memory through abstract means.

Even in collage, a technique perhaps pioneered and certainly popularized by artists like Henri Matisse with his vibrant paper cut-outs, the slight edges and overlaps of materials create a subtle, actual texture that differentiates it from a flat print. And extending even further, in performance art or installation art, the very environment can become a textural element, inviting the audience to physically interact with varying surfaces, from soft fabrics to gritty floors, creating an immersive, multi-sensory experience. It transforms the viewer from a passive observer into an active participant, doesn't it? Beyond the gallery, think about architecture and interior design: the rough exposed concrete of a brutalist building, the smooth, cool glass of a skyscraper, or the soft, inviting textures of upholstery and natural wood in a living space – all are deliberate choices to evoke specific moods and functional experiences through texture. What other unconventional art forms invite a tactile journey?

https://live.staticflickr.com/6090/6059309027_476779f1de_b.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

My Own Journey with Texture

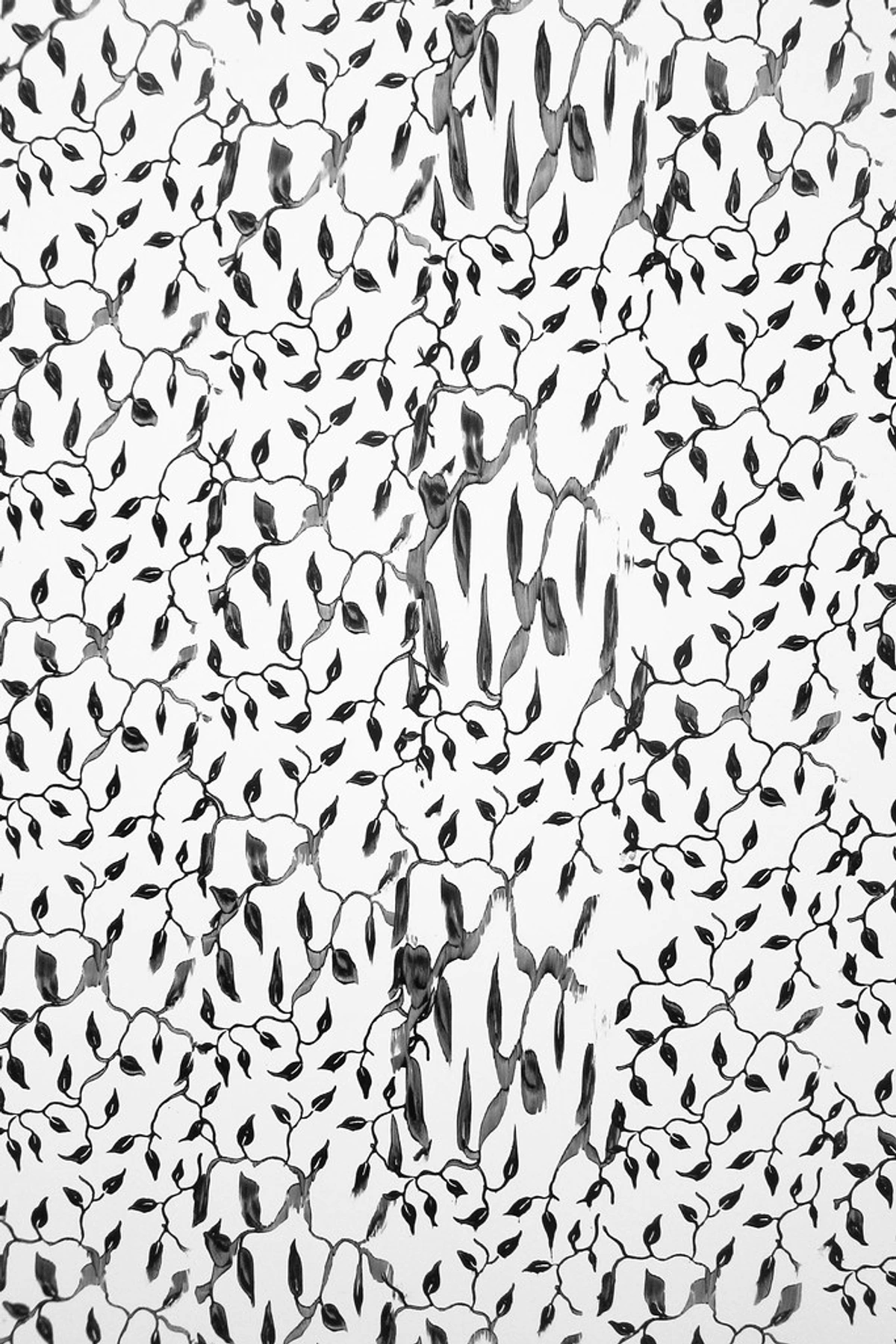

As an artist, especially one drawn to the abstract and the vibrant, texture has become a kind of silent partner in my creative process. It's like that slightly eccentric friend who always adds unexpected flair, sometimes intentionally, sometimes through a happy accident that my ego was willing to admit to at the time. While my prints are flat on the surface, the initial paintings often involve a dance with different mediums – acrylics, gels, even some gritty pastes. I build layers, sometimes with reckless abandon, then scrape them back, letting the history of the piece reside in those subtle tactile shifts. The imagined tactile experience of the viewer is always a consideration for me; even if you can't touch it, I want you to feel it.

There was this one time I was trying to create a deeply cratered effect in a piece I called 'Lunar Landscape'. I was using a palette knife, trying to get just the right amount of cragginess, and ended up accidentally sticking a paintbrush handle to the canvas – not in a dramatic, artistic statement way, but a genuinely clumsy, 'oh, for goodness sake' kind of way. What started as pure frustration transformed into a unique, accidental ridge that, once dried, felt just right, perfectly embodying the rough, uneven surface of the moon I was aiming for. It was a humbling reminder that sometimes, the most profound textural elements emerge not from rigid planning, but from embracing the unexpected and the spontaneous chaos of creation – a lesson I'm still learning, and probably always will be.

I love how a tiny raised line or a deliberate pooling of color can invite a closer look, changing the viewer's experience from a distant glance to an intimate exploration. It's my way of adding a whisper of the tangible to the purely visual, inviting you to connect on a deeper, more haptic level, even if it's just in your mind. If you're curious about how I explore these ideas and what forms they eventually take, feel free to check out some of my art for sale or learn more about my artistic journey.

Zen Dageraad, https://zenmuseum.com/

Frequently Asked Questions about Texture in Art

Navigating the rich landscape of texture in art can raise a few questions. Here are some common inquiries to help deepen your understanding:

Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What are the two main types of texture in art? | The two main types are actual texture (the physical surface you can feel) and implied texture (the visual illusion of texture created by an artist). |

| How do artists create actual texture? | Artists create actual texture through techniques like impasto (thick paint application), mixed media (adding materials like fabric, sand, or found objects), sculpting, printmaking techniques, using textured mediums, or incorporating natural materials. |

| How do artists create implied texture? | Implied texture is created using visual techniques such as varied brushstrokes, cross-hatching, stippling, careful shading, and manipulating light, shadow, color temperature, and value to suggest a surface quality. Think of how sharp lines suggest hardness or blended gradients suggest smoothness. |

| Why is texture important in art? | Texture adds depth, visual interest, and can evoke strong emotional and psychological responses. It creates a sense of realism or illusion, guides the viewer's eye, and makes art more engaging, multi-sensory, and even offers accessibility for those with visual impairments. |

| Can abstract art have texture? | Absolutely! Abstract art often heavily relies on texture – both actual and implied – to create dynamism, express emotion, and provide visual interest without relying on recognizable subjects or forms. |

| How can texture create a sense of movement or dynamism in an artwork? | Both actual and implied texture can create a sense of movement. For actual texture, swirling, thick impasto brushstrokes, like in Vincent van Gogh's 'Starry Night,' directly imply the restless motion of the sky. The physical ridges and valleys create visual paths for the eye. For implied texture, contrasting rough and smooth areas or using directional brushstrokes (e.g., long, sweeping lines) can create a dynamic push-and-pull, guiding the eye through the composition with energy, making it feel alive and in motion, even on a flat surface. |

| Which artists are renowned for their innovative use of texture? | Many artists are celebrated for their use of texture across diverse mediums and styles. Think of Vincent van Gogh for his revolutionary impasto, Jean-Michel Basquiat for layered mixed media, Gerhard Richter for his scraped, built-up surfaces, and Constantin Brâncuși for the exquisite smoothness of polished bronze sculpture. For implied texture, consider the masterful rendering of fabrics and skin by Renaissance painters like Jan van Eyck, the detailed still lifes of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin who made you feel the texture of fruit and pewter, or the intricate etchings of Albrecht Dürer. Henri Matisse for the subtle physical texture in his paper collages, and photographers like Ansel Adams for capturing the intricate textures of natural landscapes through light and shadow. Contemporary abstract artists also push boundaries, using texture to add depth and expression without relying on representation. |

| Are there ethical considerations regarding texture in art, especially for conservation? | Absolutely. While artists create tactile experiences, the "do not touch" rule in museums is paramount for conservation. Oils from skin, dust, and general wear can degrade artworks, especially those with delicate actual textures like impasto or fragile mixed media. The ethical consideration is balancing public engagement with the long-term preservation of cultural heritage, ensuring future generations can also experience these works. |

Conclusion: The Tactile Aesthetics of Art

So there you have it: texture, the unsung hero of the art world, silently working to engage our senses and deepen our connection to a piece. It's that subtle invitation to look closer, to imagine, to feel even when you can't touch. It reminds us that art isn't just about what's presented to our eyes, but about the rich tapestry of sensory experiences it can evoke, fostering what we might call a 'tactile aesthetic.' This growing appreciation for the haptic qualities of art encourages us to move beyond purely visual interpretation and to appreciate the intricate craftsmanship involved. So next time you encounter an artwork, take a moment. Don't just look; let your eyes feel, let your mind wander across its surface, and truly experience the depth texture can bring. And sometimes, just sometimes, understanding these nuances makes you appreciate the artist's creative choices and their journey through the tactile world even more. If you're curious to see how I explore these tactile ideas in my own work, I invite you to browse my art for sale or visit my museum. So, what tactile discoveries will your eyes make next, and how will they speak to your soul?