The Silent Narrator: Light's Profound Role in Art & Perception

Uncover light's essential role in art, from sculpting form and mood to guiding the eye. An artist's personal journey through history, color, and abstract techniques reveals its profound impact.

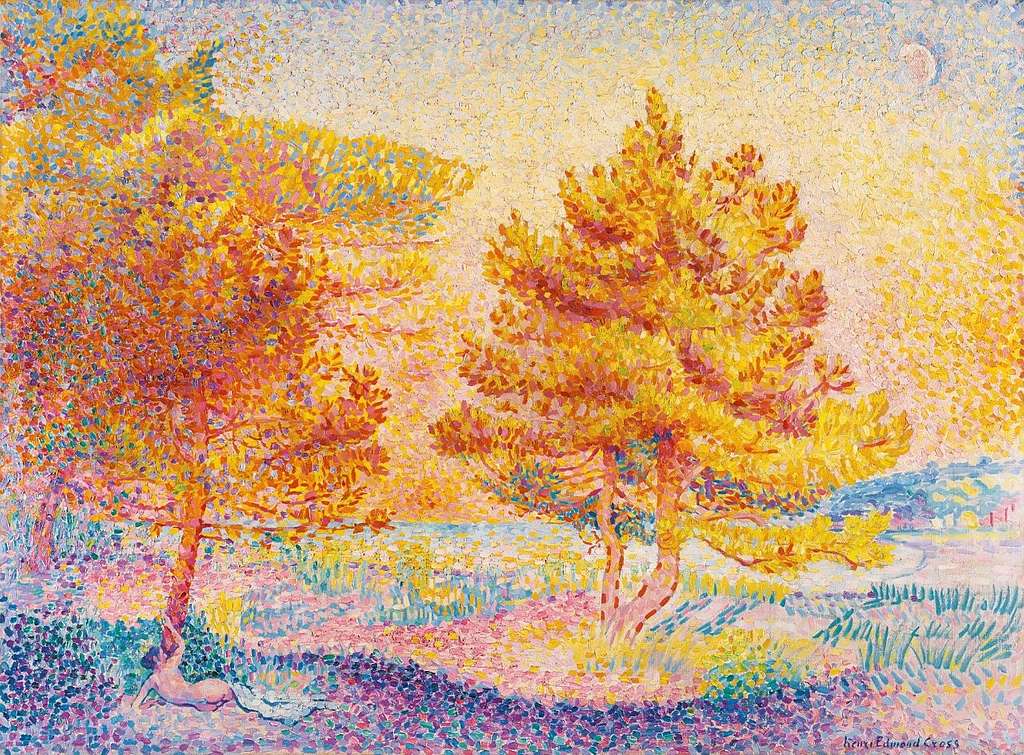

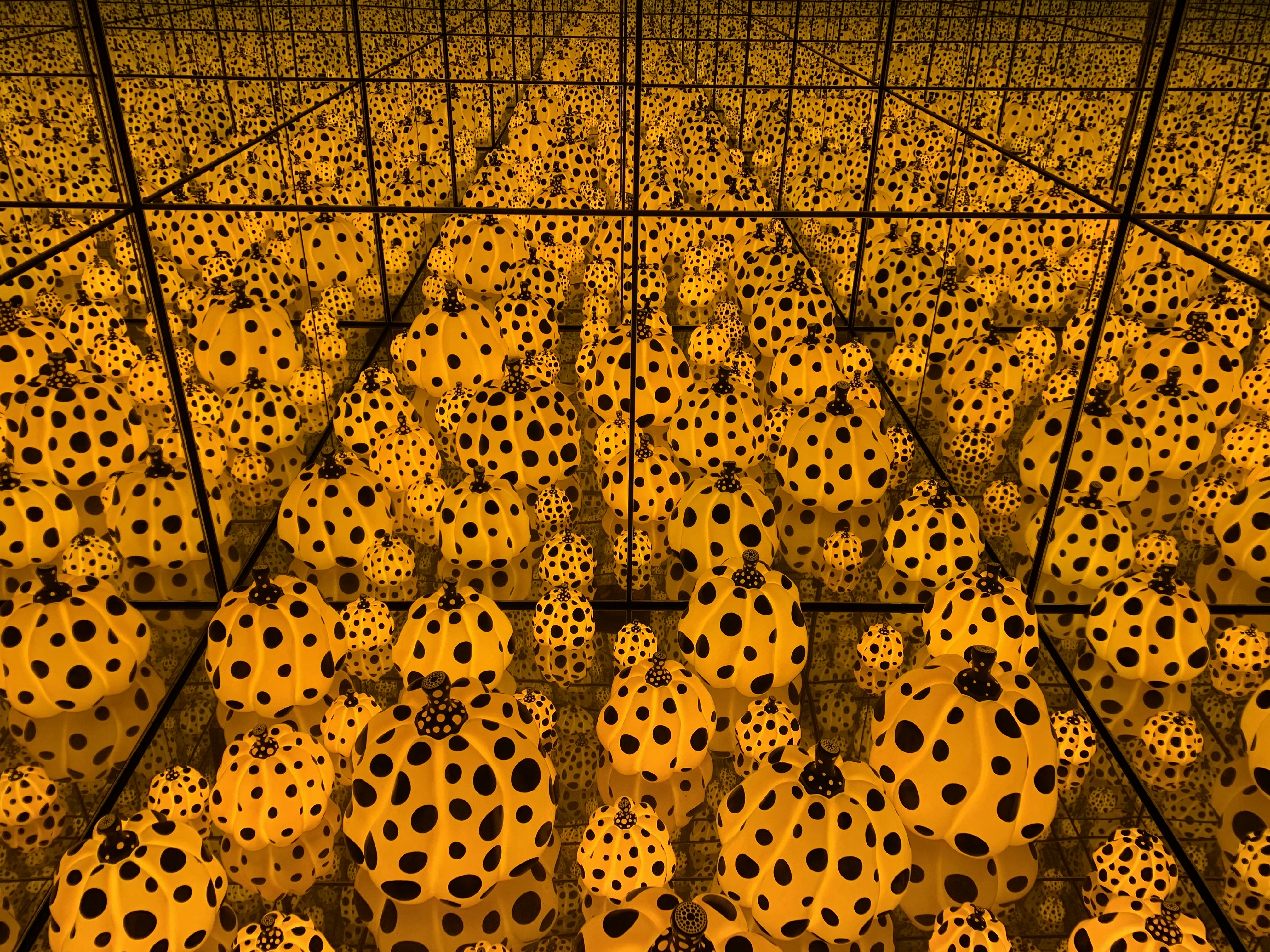

# Title <h1>The Silent Narrator: Light's Profound Role in Art & Perception</h1><p>Have you ever truly stopped to *see* light? Not just the objects it illuminates, but the light itself? For a long time, I’m going to be honest with you, I thought light in art was… well, just light. You put a sun in the sky, or a lamp in a room, and boom, you've got light. Easy, right? My younger self, bless her heart, was very efficient, if a little naive. But as I’ve stumbled through my own artistic journey, getting paint on everything from my clothes to my cat (don’t worry, she’s fine, just a bit more colorful now), I’ve realized something profound. It's like that moment when you first learn to truly *see* the subtle shifts in color in a sunset, observing the interplay of wavelengths and atmosphere, rather than just admiring the 'pretty sky.' Suddenly, a whole new dimension opens up. And that, my friend, is what understanding light in art feels like – a grand, beautiful opening, a lifelong journey into seeing. Light in art is everything. It’s not just illumination; it’s emotion, form, and story, all rolled into one radiant package. It's the silent narrator, the mood-setter, the sculptor of reality itself. It’s a profound, universal force that shapes everything we see and feel.</p><h2>My Personal Journey with Light: Why Illumination Matters So Much</h2><p>I often think about my early days, grappling with a blank canvas, wondering how to make something truly *sing*. It wasn't until I started actively contemplating light, not just as a source, but as a *tool*, that my art began to evolve. It’s funny, isn’t it, how something so fundamental can be so easily overlooked until you consciously decide to embrace it? My path, like many artists, has been a constant learning curve, a slow reveal of secrets that seem obvious in retrospect. If you're curious about the twists and turns of this sometimes messy, often exhilarating process, you can always peek at my [artistic journey](/timeline).</p><p></p><p>credit, [licence](/finder/page/the-definitive-guide-to-understanding-abstract-art-styles)</p><p>For me, especially in my [abstract work](/finder/page/the-definitive-guide-to-understanding-abstract-art-styles), light isn't about replicating reality; it's about creating a new one. It's about that feeling you get when a piece of music swells, or when a sudden ray of sun breaks through the clouds. It’s less about drawing the sun and more about evoking the *feeling* of sunlight, or the quiet mystery of twilight. It’s the internal glow, the atmosphere that pulls you in. It's truly a [personal philosophy](/finder/page/why-i-paint-abstract:-my-personal-philosophy-and-artistic-vision) for many of us who work in abstraction.</p><h2>The Many Hats of Light: Diverse Roles in Art</h2><p>Light, in the hands of an artist, is a chameleon, shifting its purpose to serve the narrative, the mood, or the very structure of the artwork. It's truly astonishing how versatile it is, capable of shaping everything from the tangible form of an object to the intangible feeling of a moment.</p><h3>Revealing Form and Space (Value & Contrast)</h3><p>But how does light actually perform this magic, making a flat surface suddenly sing with depth? This is perhaps the most fundamental job of light: to make things *real*. Without light and shadow, everything would be flat. Think about it: a sphere only looks round because one side is directly lit, another falls into shadow, and there are subtle gradients in between, including <strong>reflected light</strong> bouncing off surrounding surfaces, gently illuminating the shadow side. This interplay of light and dark, meticulously controlled, is known as <strong>chiaroscuro</strong> (a fancy Italian word for 'light-dark'), and it's the fundamental *technique* artists use to create the illusion of depth and volume.</p><p>The *type* of light source also makes a huge difference. A <strong>point light source</strong>, like a single lamp or the sun, creates sharp, defined shadows, emphasizing edges and contours. A <strong>diffuse light source</strong>, like an overcast sky or a large window, produces softer, more gradual shadows, which can make forms appear smoother and less dramatic. Knowing how to control these allows an artist to truly sculpt with illumination.</p><p>I remember trying to draw a simple apple in art school. For weeks, it looked like a flat, red disc. My professor, a stern but insightful woman who probably suspected I was more interested in the cafeteria's questionable chili, finally told me to stop looking at the color. “Focus purely on the *values*,” she commanded – the lightness and darkness. Suddenly, by ignoring the 'red' and focusing on the spectrum from white highlights to deepest shadows, the apple miraculously popped off the page, becoming a tangible, three-dimensional object. It wasn't about the color; it was about the light revealing its form. This is also where the concept of <strong>lost and found edges</strong> comes in, where areas of form subtly blend into shadow or background, only to reappear, creating a more dynamic and believable sense of depth by mimicking how our eyes naturally perceive forms emerging from and receding into their surroundings.</p><p>Beyond just individual objects, light also sculpts entire landscapes through <strong>atmospheric perspective</strong>. Distant mountains often appear lighter, less saturated, and bluer than closer ones because the atmosphere scatters light, making distant forms recede. Artists leverage this subtle effect to create a profound sense of expansive space, making you feel the vastness of a vista, rather than just seeing a flat backdrop. In abstract or stylized landscapes, artists might even exaggerate or simplify this effect, using sharp color contrasts or blurred transitions to achieve specific moods or compositional drama, transcending mere realism to evoke a feeling of infinite depth or stark flatness.</p><p></p><p>credit, [licence](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en)</p><p>Furthermore, artists subtly employ <strong>color temperature</strong>—the warmth or coolness of a color—to enhance this illusion of depth. Warm colors (reds, oranges, yellows) tend to advance, appearing closer to the viewer, while cool colors (blues, greens, violets) tend to recede. By painting a distant mountain in cooler, bluer tones, for instance, and a foreground object in warmer hues, the artist further amplifies the sense of space and dimension.</p><h3>The Direction of Light: Sculpting with Illumination</h3><p>The way light hits an object isn't just about brightness; it's profoundly about its *direction* and *intensity*. <strong>Frontal lighting</strong>, where the light source is directly in front of the subject, flattens forms and minimizes shadows, making things appear two-dimensional. Think of a passport photo – perfectly lit, perfectly flat. <strong>Side lighting</strong>, however, casts dramatic shadows, accentuating texture and creating a strong sense of volume and drama. It’s perfect for highlighting the ruggedness of a landscape or the wrinkles on an aged face. And then there's <strong>backlighting</strong>, where the light source is behind the subject, creating a striking silhouette or a radiant halo effect around the edges. Each direction tells a different story, sculpting forms in unique ways. Furthermore, the *intensity* of the light—how bright or dim it is—dramatically impacts how forms are perceived and the overall emotional weight of a piece.</p><h3>Light & Texture: Feeling the Surface</h3><p>Beyond just revealing form, light is crucial for conveying [texture](/finder/page/the-definitive-guide-to-understanding-texture-in-art). <strong>Raking light</strong>, for example, which hits a surface at a sharp, shallow angle, will exaggerate every bump, ridge, and indentation, making a rough wall appear even more rugged or the delicate weave of fabric incredibly palpable. Conversely, a very soft, diffuse light can smooth out textures, making surfaces appear uniform and unblemished. Artists also physically manipulate surfaces, using techniques like <strong>impasto</strong> (applying paint thickly) or <strong>scumbling</strong> (applying a thin, broken layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint) to create actual texture that catches or reflects light in specific ways, allowing you to not just *see* a surface, but almost *feel* its coarseness or silkiness, adding another layer of sensory experience to the artwork. Moreover, techniques like <strong>dry brushing</strong> can leave a broken, granular effect that catches light, emphasizing rough surfaces, while <strong>stippling</strong> (using small dots) can create shimmering, light-filled textures from a distance.</p><h3>Setting the Scene: Mood and Atmosphere</h3><p>Have you ever walked into a softly lit room versus a brightly lit one? Your mood shifts instantly. This isn't accidental; it taps into the deep <strong>psychology of light perception</strong> and the [psychology of color](/finder/page/the-psychology-of-color-in-abstract-art-beyond-basic-hues). Our brains are wired to interpret specific lighting conditions, associating them with certain emotions and situations. The same happens in art. Light is a potent emotional lever. <strong>Warm, golden light</strong> (high color temperature, like a sunset or a cozy fireplace) can evoke comfort, nostalgia, or joy. It speaks of quiet evenings and gentle warmth. <strong>Harsh, stark light</strong> (often cooler, lower color temperature, like midday sun or fluorescent bulbs) might suggest drama, tension, or even a sense of exposure and stark reality. <strong>Dim, murky light</strong> can create mystery, melancholy, or a dreamlike state. Artists masterfully use light to depict specific times of day or seasons, from the crisp, cool light of a winter morning to the hazy, golden glow of a summer afternoon, each imbued with its own emotional resonance. Light can also strongly convey sensations of heat (intense, red-orange light) or cold (sharp, blue-white light), influencing our physical and emotional response to a piece.</p><p>I find this endlessly fascinating. In my own work, I sometimes start with a feeling – say, the quiet hush of a dawn sky – and then think about what kind of light would embody that. It’s not just painting a blue sky; it’s painting a *hushed* blue sky, a feeling of awakening. It's all about the emotional resonance of that illumination, capturing not just a scene, but a specific, fleeting moment in time, a memory or a future longing.</p><h3>The Language of Color: Light's Intimate Dance</h3><p>Light and [color](/finder/page/how-artists-use-color) are inseparable partners. The color we perceive is simply the wavelengths of light reflected by an object. The red we perceive in an apple, for instance, is actually the red wavelength of light that *isn't* absorbed but rather reflected back to our eyes. But light itself also has color – think of the warm glow of a sunset or the cool blue of a cloudy day. This is known as <strong>color temperature</strong>: warm light has more reds/yellows, cool light more blues. Artists manipulate this relationship profoundly, understanding that ambient light can shift the perceived hue of an object. A white shirt under a warm sunset will appear golden, not pure white. They also differentiate between <strong>local color</strong> (the true, inherent color of an object in neutral light, like a 'red' apple) and <strong>optical color</strong> (the color an object *appears* to be due to the influence of light and surrounding colors). Mastery lies in showing the optical color while hinting at the local color, or, in abstract art, transcending local color entirely to create a new optical reality.</p><p>They also understand that placing <strong>complementary colors</strong> (like red and green, or blue and orange) next to each other, especially when one is bathed in a particular light, can make both appear more vibrant and intense. This phenomenon, known as <strong>simultaneous contrast</strong>, means colors influence each other's perceived luminosity and hue, enhancing the illusion of light and shadow by making adjacent colors seem brighter or duller, warmer or cooler, depending on their relationship.</p><p>Pointillists, like Seurat and Cross, took this to an extreme, placing tiny dots of pure color side by side, allowing the viewer's eye to 'mix' them and create the illusion of vibrant, shimmering light. It's a clever trick, making the viewer's brain do half the work! In my [abstract pieces](/buy), I often think about how different colors interact, not just next to each other, but how they might *feel* if bathed in a certain kind of light, or how they generate their own internal luminosity, creating their own world of [color and light](/finder/page/the-language-of-light:-how-illumination-shapes-my-abstract-compositions).</p><p></p><p>credit, [licence](https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/)</p><h3>Directing the Eye: Compositional Power</h3><p>Artists are, in a way, master puppeteers, guiding your gaze across the canvas. Light is one of their most powerful strings. Bright highlights draw immediate attention, while receding shadows lead the eye away or create a sense of depth and mystery. This creation of a visual hierarchy is further enhanced by <strong>color temperature</strong>; warm colors tend to advance, drawing the eye forward, while cool colors recede, creating depth and guiding the gaze deeper into the [composition](/finder/page/the-definitive-guide-to-composition-in-abstract-art). It’s all part of the subtle art of storytelling, creating a visual narrative. The interplay of luminous areas and darker regions forms pathways, ensuring the viewer's eye follows the narrative the artist intends. Sometimes, when I feel a piece isn't quite working, I'll ask myself, 'Where is the light leading the eye? Is it taking them on the journey I want, or are they getting lost in the visual wilderness?' Light can also be manipulated to imply movement, through techniques like blurring, streaking, or depicting the path of a light source, creating a dynamic energy within a static frame.</p><h3>The Power of Shadow: Absence as Presence</h3><p>It's tempting to think of shadows as merely the absence of light, but in art, they are active, dynamic compositional elements. Shadows define planes, connect forms, and create a sense of mystery or impending drama. They are not merely passive consequences of light but are intentionally shaped and deployed by artists to guide the eye, create psychological tension, establish spatial relationships, and, crucially, imbue objects with a sense of <strong>volume and weight</strong>, making them feel grounded and tangible. Think of how a deep, engulfing shadow can isolate a figure, or how elongated shadows can convey the passage of time. They are the quiet counterparts that give light its voice, making the bright areas truly sing.</p><hr><h2>Luminaries Throughout History: Artists Who Mastered Light (and the Lessons They Taught Me)</h2><p>Let's journey through time and learn from the masters who, with their brushes and keen eyes, transformed light from a mere phenomenon into a powerful artistic tool. The history of art is, in many ways, a history of light. From the dramatic theatricality of Baroque to the fleeting observations of Impressionism, artists have always been captivated by it, constantly finding new ways to harness its power. These are some of the artists who, through their mastery of light, profoundly shaped my understanding:</p><ul><li><strong>Leonardo da Vinci (Renaissance): The Precursor of Soft Light.</strong> Long before the Baroque masters, [Leonardo](/finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-leonardo-da-vinci) meticulously studied light and optics. His revolutionary technique, <strong>sfumato</strong>, blurred sharp outlines and blended colors seamlessly, creating subtle gradations of light and shadow that enveloped his subjects in a soft, ethereal atmosphere. This pioneering approach laid the groundwork for later artists, demonstrating light’s ability to create profound realism and emotional depth without harsh contrasts, a lesson in subtlety and gradual transition.</li><li><strong>Johannes Vermeer (Baroque): The Intimate Glow of Domesticity.</strong> Vermeer, a Dutch master, was unparalleled in his ability to capture the subtle, soft light filtering into quiet domestic interiors. His paintings are renowned for their delicate rendering of light reflecting off different textures – pearls, fabric, skin – creating an almost tactile realism. He demonstrated how even the most ordinary scenes could be imbued with profound beauty and psychological depth through a meticulous study of light's gentle touch, making every sunlit room a silent sanctuary, a moment of captured stillness.</li><li><strong>Caravaggio (Baroque): The Master of Psychological Drama.</strong> His use of extreme <strong>chiaroscuro</strong>, often referred to as *tenebrism*, didn't just define form; it plunged backgrounds into impenetrable shadow to spotlight figures with intense, almost blinding light, creating profound psychological tension and a sense of immediate, raw drama. He taught me that darkness isn't just an absence of light, but a powerful, active force in storytelling, a stage where profound human experience unfolds.</li><li><strong>The Impressionists (Monet, Renoir, Degas): Capturing the Fleeting Moment.</strong> These artists were obsessed with capturing the *effect* of light itself, almost scientifically. They didn't paint objects; they painted the light *on* objects, often working quickly ([en plein air](/finder/page/what-is-plein-air-painting)) to capture fleeting moments and changing atmospheric conditions. Their focus was on the ephemeral quality of light, how it alters colors and forms throughout the day, and how our perception of reality is constantly shifting. They showed me that painting is as much about seeing the invisible as it is about depicting the tangible, a dance with the momentary.</li></ul><p></p><p>credit, [licence](https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/)</p><ul><li><strong>Post-Impressionists (Van Gogh, Seurat): Emotion and Science.</strong> Building on the Impressionists, artists like Van Gogh used light to express intense emotion, making suns blaze with a frenetic, almost spiritual energy, imbuing landscapes with his inner turmoil. Conversely, Seurat, as mentioned earlier, dissected light into its pure color components, using his methodical [pointillist](/finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-pointillism) technique to create a shimmering, optically mixed luminosity, a more scientific exploration of light's properties. These two showed me the vast emotional and intellectual spectrum light can span, from raw feeling to precise calculation.</li><li><strong>Fauvists (Matisse, Derain): Light Through Pure Color.</strong> These '[Wild Beasts](/finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-fauvism)' used shockingly vibrant, non-naturalistic colors to convey emotion, often creating their own internal light source through pure color saturation. It's less about external light sources casting shadows and more about the light *within* the painting, emanating from the juxtaposition and intensity of the hues themselves. They taught me that color *is* light, and that art can create its own rules of illumination, a liberating burst of visual energy. [Henri Matisse](/finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-henri-matisse) is a prime example of this philosophy.</li></ul><p></p><p>credit, [licence](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)</p><ul><li><strong>Contemporary Art: Evolving Perceptions of Light.</strong> Even in contemporary art, light continues to be a central subject and tool. Artists like [Gerhard Richter](/finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-gerhard-richter), in his blurred abstract paintings, often create a sense of depth and atmosphere through the subtle play of light on textured surfaces and the blending of colors, evoking an internal glow and a profound sense of mood. <strong>James Turrell</strong>, on the other hand, makes light itself the tangible subject, bending our perception of space and color through precisely controlled light environments, turning galleries into immersive experiences. And <strong>Olafur Eliasson</strong>, another trailblazer, uses light, water, and air to create vast, often interactive installations that challenge our understanding of natural phenomena and our place within them, often evoking powerful sensory and emotional responses. <strong>Yayoi Kusama</strong>, with her immersive 'Infinity Mirror Rooms,' transforms light into an endless, pulsating experience of dots and reflections, turning simple illumination into a profound exploration of space and perception, a truly abstract and conceptual use of light.</li></ul><p></p><p>credit, [licence](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)</p><p>In the digital realm, artists leverage advanced rendering engines and software to simulate light with incredible realism and creativity, pushing the boundaries of what is possible, from hyper-realistic textures to ethereal, abstract illuminations. These artists remind me that light is an ongoing conversation, constantly evolving in its artistic expression, especially in abstract compositions where light often manifests as an inherent quality of the forms and colors themselves, creating its own visual rhythm and [language of light](/finder/page/the-language-of-light:-how-illumination-shapes-my-abstract-compositions). The deliberate use of <strong>artificial light</strong>, whether as neon, LED, or precisely focused stage lighting, is also a prominent feature, allowing artists to sculpt ephemeral environments or imbue their work with the distinct, often stark, qualities of modern life.</p><p></p><p>credit, [licence](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/)</p><hr><h2>Shining a Light on Your Own Art (or Appreciation): Practical Thoughts</h2><p>So, what does all this mean for you, whether you’re an aspiring artist or just someone who loves looking at art? It’s about cultivating a more discerning eye, a deeper connection to the visual world.</p><ul><li><strong>For the Creator:</strong> Stop 'drawing the sun' and start 'drawing the *effect* of the sun'. Observe light in your everyday life: how it falls on objects, how it changes colors, how shadows wrap around forms, and how it varies with direction and time. Experiment with <strong>value studies</strong> – simple black and white sketches can teach you volumes about form without the distraction of color (believe me, sometimes you just want to paint the pretty colors, but the professor insists on black and white!). Try sketching the same object under different lighting conditions (e.g., direct sunlight, diffused light, backlighting). And don't be afraid to embrace color as a light source itself. My own [contemporary, colorful pieces](/buy) often explore this idea; you can see what I mean by checking out my art for sale. What revelations about light did you uncover today? I'd love to hear about your own discoveries – share them with me!</li><li><strong>For the Viewer:</strong> When you look at a painting, ask yourself: Where is the light coming from? What time of day is it? What emotion does the light evoke? How does it define the forms? How does it affect the colors? Is it warm or cool? Is it natural or artificial? How do you think the artist created that sense of depth or atmosphere? Suddenly, a painting becomes a conversation, a puzzle, a rich tapestry of visual information, offering layers of understanding beyond the initial glance.</li></ul><p>Seriously, try this: just go outside and *look* at how the light changes throughout the day. It’s like a free, ever-changing art lesson, but with squirrels and maybe some questionable fashion choices from passersby. It's fascinating how a dull street can look magical under the right light, transforming the mundane into something extraordinary. So, grab your sketchbook, or simply pause and observe. You'll never look at the world (or a painting) the same way again.</p><h2>FAQ: Your Burning Questions About Light and Art, Answered (My Way)</h2><p>Here are some questions I've either been asked or pondered myself while covered in paint, coffee, or occasionally, a rogue feather from my cat.</p><ul><li><strong>Q: Is natural light always best for painting?</strong><ul><li><strong>A:</strong> Not necessarily, and frankly, a bit of a myth sometimes! While natural light (especially indirect northern light for studio work) is often preferred for its consistency and broad spectrum, artificial light offers incredible control. Think of Rembrandt's dramatic indoor scenes – all carefully controlled artificial light (candles, lamps). It depends entirely on the story you want to tell. Sometimes, the harsh fluorescent glow of a supermarket is exactly the mood you need to capture, or the focused beam of a spotlight is essential for drama. It's about intentionality, not purity.</li></ul></li><li><strong>Q: How do abstract artists use light if they're not painting realistic scenes?</strong><ul><li><strong>A:</strong> Great question! For abstract artists, light is often about the inherent luminosity of the colors themselves, the illusion of depth created by strong contrasts in value and hue, or the feeling evoked by warm versus cool tones. It's less about a literal external light source hitting an object and more about creating an internal glow or atmospheric quality *within* the piece. Artists skillfully use <strong>gradients and subtle color transitions</strong> to simulate the passage of light, or they leverage contrasting values and hues to create <strong>visual weight</strong> that pushes elements forward or pulls them back, forming spatial depth that is entirely self-contained. It's truly a [personal philosophy](/finder/page/why-i-paint-abstract:-my-personal-philosophy-and-artistic-vision) for many, allowing them to construct an entire world of light and shadow from imagination.</li></ul></li><li><strong>Q: Can light itself be the subject of a painting?</strong><ul><li><strong>A:</strong> Absolutely, unequivocally! Think of artists like James Turrell, who create entire installations focused purely on light and its effects, bending our perception of space and color. Or Impressionists trying to capture a specific moment of sunlight on water. For me, sometimes the very *idea* of 'light' – its warmth, its energy, its gentle fading, its transformative power – is the entire inspiration for a piece, even if it's expressed through abstract shapes and colors. It's a profound, universal force that artists can absolutely make the central character of any artwork.</li></ul></li><li><strong>Q: How do artists simulate different kinds of light across various mediums?</strong><ul><li><strong>A:</strong> This is fascinating because each medium has its strengths! In <strong>oil painting</strong>, artists use glazing (thin, transparent layers of paint) to build up luminosity and create a deep, glowing effect, while impasto (thick paint) can catch light and add texture. <strong>Watercolors</strong> achieve luminosity through the white of the paper shining through transparent washes, mimicking light and airiness. In <strong>digital art</strong>, artists have an incredible array of tools – from glow effects and layer blending modes to mimicking photographic lighting setups – allowing for unparalleled control over light's intensity, color, and direction. By understanding each medium's unique properties, artists can masterfully evoke the desired illumination.</li></ul></li><li><strong>Q: How do artists use light to convey specific emotions or psychological states?</strong><ul><li><strong>A:</strong> This is one of light's most powerful applications! Artists use a combination of factors: <strong>color temperature</strong> (warm for comfort/joy, cool for melancholy/tension), <strong>contrast</strong> (high for drama/starkness, low for mystery/gentleness), and <strong>direction</strong> (backlighting for awe/mystery, harsh frontal light for exposure). By deliberately choosing these elements, they can create an atmosphere that directly influences the viewer's emotional response, guiding them through a narrative of feeling, from quiet contemplation to explosive drama.</li></ul></li><li><strong>Q: How is light used to create a sense of movement or dynamism in a static artwork?</strong><ul><li><strong>A:</strong> Great question! Artists achieve this in several ways. They might depict blurred light trails, like streaks from a moving vehicle, or use radiating light rays to suggest energy emanating from a source. High contrast and strong directional light can create sharp shifts and leading lines that visually pull the eye, implying motion. Even the illusion of shimmering or flickering light, often through techniques like pointillism or varied brushstrokes, can give a static image a vibrant, active quality. It's about tricking the eye into perceiving what isn't literally there, creating a sense of unfolding action or kinetic energy.</li></ul></li></ul><h2>My Final Ray of Insight: It's All About Seeing</h2><p>Ultimately, understanding light in art isn't just about technical skill; it's about *seeing*. It’s about training your eyes to look beyond the obvious, to notice the subtle interplay of forces that bring an image to life. It’s a lifelong journey, this seeing thing, and honestly, one of the most rewarding parts of being an artist. Every new painting is an opportunity to chase that elusive glow, to coax a little bit of magic onto the canvas, to create my own light.</p><p>So next time you look at a piece of art, or even just glance out your window, take a moment. Don't just see what's there; see *how* the light is making you see it. It's a wonderful rabbit hole to fall down, and I promise, you'll never look at the world (or a painting) the same way again.</p><p>And if you're ever in 's-Hertogenbosch, feel free to drop by my [museum](/den-bosch-museum) to see how I try to capture a little bit of that magic myself. Or if you're feeling adventurous, explore my [latest creations](/buy) online.</p>