My Enduring Journey Through the Dutch Golden Age: 5 Masterpieces and Their Timeless Echoes

Join my personal exploration of 5 iconic Dutch Golden Age masterpieces by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Hals, Steen & Ruisdael. Discover their history, groundbreaking techniques, and why they profoundly inspire contemporary art.

My Enduring Journey Through the Dutch Golden Age: 5 Masterpieces and Their Timeless Echoes

I remember standing, utterly mesmerized, before Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring, trying to unravel the secret held within that single, luminous pearl. It was a moment that ignited a lifelong fascination with the Dutch Golden Age, a period where art seemed to capture not just paint on canvas, but the very soul of a nation. This wasn't just a fleeting interest; it felt like time travel, a direct connection to a vibrant, bustling past that still informs every stroke of my brush today. What makes these strokes of genius, these canvases born in the Dutch Golden Age, still echo so profoundly in our modern world? It’s a question that often catches me, especially when I’m staring at a piece, trying to decipher its whispered secrets. My own journey through art, both as an admirer and a creator, has been profoundly shaped by this vibrant 17th-century period in the Netherlands—an era of unprecedented innovation, burgeoning wealth, and a cultural confidence that painted itself onto every canvas. I’ve often wondered how something so distant can feel so viscerally present, how it continues to inspire my artistic journey today. This article isn't just a historical dive; it's my personal exploration of five iconic Dutch Golden Age masterpieces, designed to illuminate their historical context, groundbreaking artistic techniques, and enduring legacy, ultimately connecting them to the principles that inform my own contemporary art practice.

Join me, and let’s explore five masterpieces that, for me, aren’t just paintings; they’re living conversations across centuries, offering a window into both history and the timeless human experience, and revealing the roots of much of what we value in visual storytelling today. And yes, I’ve gathered some answers to your most burning questions at the end.

The Dutch Golden Age: A Cultural Kaleidoscope Forged in Fire and Ingenuity

Picture this: it’s the 17th century, and the tiny Dutch Republic, having just fought a grueling Eighty Years' War for independence from the Spanish Habsburgs, is not just surviving—it’s absolutely thriving. This wasn't merely about picturesque canals and tulip fields, though those were charming elements. This was a global trading empire, forged in the crucible of conflict and resilience, with new trade routes established and a strong national identity shaped by its hard-won freedom. This economic engine was fueled by the formidable Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (WIC), which brought unprecedented wealth from exotic goods like spices, silks, and porcelain, directly funding an explosion in the arts and sciences, propelling the Netherlands onto the global stage. It was an era defined by the rise of capitalism, a strong Protestant work ethic (deeply influenced by Calvinism's emphasis on hard work, individual piety, and sobriety, which redirected artistic focus away from lavish religious displays and towards everyday virtues), and a post-war political stability, all conspiring to create incredibly fertile ground for the arts.

This economic boom, coupled with staggering scientific breakthroughs (think Christiaan Huygens and his pendulum clock and groundbreaking work on light, or Baruch Spinoza laying the groundwork for modern philosophy), cultivated an explosion where art became a central pillar of everyday society. Artists like Vermeer, for example, might have keenly observed developments in optics and perspective, potentially even using tools like the camera obscura, informing the meticulous rendering of light in their paintings. I sometimes think about how many minds were just exploding with new ideas at once; it must have been an intoxicating time to be an artist or a thinker.

Crucially, this wasn't an age where art was exclusively the domain of the church or the monarchy, oh no. The burgeoning merchant class, the wealthy burghers, became the new, enthusiastic patrons. And here’s where things get really fascinating: their Calvinist values, emphasizing humility, hard work, individual piety, and a focus on daily life, profoundly steered artistic themes. This often meant a deliberate move away from the lavish, idol-like religious spectacles common elsewhere in Catholic Europe. Instead, Dutch art championed earthly virtues, domesticity, and the quiet dignity of individual existence.

Patrons sought art that reflected their own world: meticulously rendered portraits of themselves and their families, delightful genre scenes (those everyday life snapshots, often subtly imbued with moral lessons about diligence, moderation, or indulgence, transforming mere depictions into rich storytelling), vast landscapes celebrating their hard-won dominion over water (a direct reflection of their industriousness and engineering prowess in reclaiming land like polders), and exquisite still lifes that, with their precise detail, often hinted at the transience of life (vanitas) or showcased earthly prosperity (pronkstilleven). This shift truly opened the floodgates for artists to explore new subjects and push boundaries, making it an incredibly dynamic period for the history of art.

The Vibrant Dutch Art Market

And the art market? It was a vibrant ecosystem! Unlike other parts of Europe where commissions from church and royalty dominated, the Dutch Republic saw the rise of a robust open market. Art dealers and auction houses flourished, making art surprisingly affordable and widely accessible, even for many in the middle class. Records indicate that even modest homes could boast several paintings, transforming art from an exclusive luxury into an integral part of home décor and a symbol of civic pride. This economic engine, fueled by global trade and an appreciative populace, cultivated an environment ripe for artistic innovation and specialization that we still marvel at today—a truly exciting time, fostering artistic freedom and a diversity of subject matter previously unseen.

Stepping into the Canvas: My Top 5 Iconic Masterpieces

Choosing just five iconic artworks from such a rich period feels a bit like trying to pick your favorite cloud in a vast, dramatic sky – almost impossible, yet utterly compelling to try! But these are the ones that, for me, truly capture the spirit, the innovation, and the enduring magic of the Dutch Golden Age. They represent a cross-section of the era's most celebrated genres and artistic temperaments: from grand group portraiture to intimate studies, from boisterous genre scenes to majestic landscapes. To guide our journey, here's a quick overview of these pivotal artworks, each a window into that extraordinary era:

Artwork Title | Artist | Year (approx.) | Key Characteristic / Significance | My Personal Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Night Watch | Rembrandt van Rijn | 1642 | Dynamic, narrative group portrait challenging static conventions | A living, breathing narrative, pushing boundaries of collective portraiture. |

| Girl with a Pearl Earring | Johannes Vermeer | c. 1665 | Enigmatic tronie with masterful handling of light and texture | Captures a profound, quiet intimacy and the sheer magic of reflected light. |

| The Laughing Cavalier | Frans Hals | 1624 | Spontaneous brushwork capturing fleeting expression and opulent detail | A vibrant spark of life, a personality leaping off the canvas with astonishing immediacy. |

| The Merry Family | Jan Steen | c. 1668 | Lively genre scene with embedded moral allegory and lively narrative | Humanity in all its messy, joyful, and sometimes admonishing, relatable glory. |

| The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede | Jacob van Ruisdael | c. 1670 | Majestic, atmospheric landscape symbolizing Dutch mastery over nature | Nature's grandeur and human resilience, rendered with breathtaking atmospheric mastery. |

1. Rembrandt van Rijn: The Night Watch

A Symphony of Light, Movement, and Audacious Narrative

Let's be honest, could I really start anywhere else? Rembrandt's The Night Watch isn't just a painting; it's a force of nature. Painted in 1642, this colossal, dynamic group portrait of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq's civic guard company was originally commissioned for the Kloveniersdoelen (the civic guard's headquarters). These civic guards, or schutterij, were volunteer militia companies that played a vital role in maintaining civic order and defense, but also served a significant social function, showcasing the unity and prominence of Amsterdam's burgher class. What makes it revolutionary is how it fundamentally challenged the conventions of its time. Traditional group portraits often featured stiff, posed figures lined up in neat rows, each given equal prominence. Rembrandt, however, gave us a bustling, animated moment frozen in time – a true narrative unfolding before our eyes, seemingly preparing for a parade. He broke the mold of traditional group portraiture by depicting the company in action, using light and shadow to create drama and focus on key figures.

I remember standing in front of it at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. It was less an observation and more an experience – a visceral rush of energy and drama that pulled me into its bustling scene. The sheer scale alone is breathtaking, but it’s his revolutionary use of chiaroscuro – that masterful play of dramatic light and shadow, a technique perfected in Baroque art – that truly grabs you. Figures emerge from the darkness, drawing your eye to Captain Frans Banninck Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch at the center. It’s not just light and shadow; it’s emotion, it’s narrative, it’s a vibrant window into a specific, living moment. This isn't merely a record of individuals; it's a story, an event, a palpable energy that anchors the legacy of Rembrandt van Rijn in art history. The way he balanced over a dozen figures, making each feel individual yet part of a coherent, dramatic whole, is a compositional masterclass. It's a painting that demands your engagement, pulling you into its dramatic space. And speaking of drama, it's a common misconception that the painting was always as dark as it appears today; centuries of dirt and varnish, later removed, initially contributed to its 'night watch' moniker, though its original lighting was indeed theatrical. This masterpiece is also a prime example of how light is fundamental to composition.

2. Johannes Vermeer: Girl with a Pearl Earring

The Enigma of the Gaze and the Alchemy of Light

From Rembrandt's dramatic grandeur and bustling energy, we pivot to Johannes Vermeer's world of quiet intimacy, and a painting that’s often hailed as the "Mona Lisa of the North": Girl with a Pearl Earring. Now, I confess, sometimes you just have to go see these things in person to truly feel them, right? And trust me, this is one of them. It earns its moniker not just for its fame, but for the captivating enigma of her gaze and the subtle interplay of light that makes her seem utterly alive, her identity a perpetual mystery.

Imagine this: a young woman, turning to face you over her shoulder, her lips slightly parted as if she's about to speak. Her eyes, wide and luminous, hold an almost unsettling directness. And that luminous pearl – it’s not just a detail, it’s a focal point, almost impossibly bright, catching the light against the deep shadow of her neck. This isn't a commissioned portrait of a specific individual. Instead, it's a tronie – a type of head study common in Dutch Golden Age painting, intended to explore facial expressions, interesting character types, or unusual costumes rather than depict an identifiable person. Artists used tronies as a way to hone their skills in capturing character, light, and texture, often selling them on the open market as more affordable pieces. While many artists like Frans Hals also created tronies, Vermeer's are distinctive for their profound psychological depth and ethereal rendering of light, elevating them beyond mere studies. Its immense popularity and the compelling nature of her gaze mean it functions like a portrait for countless viewers, blurring the lines between study and a deeply personal likeness. Vermeer imbues it with such life and mystery that it transcends a mere study.

He was a master of capturing light, making mundane domestic scenes glow with an otherworldly calm, almost as if he painted with pure air. His painstaking technique, often involving layers of translucent glazes and meticulous application of pigments like precious ultramarine, allowed him to render light with an almost photographic precision – some even speculate he used a camera obscura to achieve this specific luminescence and sharp focus. The subtle way the light plays on her skin, the texture of her turban, the simplicity of her gaze – it’s just captivating. These quiet masterpieces, they whisper rather than shout, and I find that absolutely compelling. You can typically find this breathtaking piece at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, but many incredible Golden Age works, much like this singular work, grace the halls of grand institutions worldwide. While we’re discussing Vermeer’s subtle genius, consider this thematically resonant work from another Baroque master.

3. Frans Hals: The Laughing Cavalier

The Electric Spark of Fleeting Emotion and Uninhibited Brushwork

If Vermeer gives us hushed secrets and introspective calm, Frans Hals bursts onto the scene with unbridled vivacity and a knack for capturing the fleeting spark of personality. While I don't have an image of The Laughing Cavalier right here, trust me when I say it embodies everything I love about Hals's work. Painted in 1624, this dashing young man, with his confident gaze and that enigmatic, almost-smile, is a testament to Hals's spontaneous and lively brushwork. He often employed an alla prima technique, painting wet-on-wet, which allowed for incredible immediacy and a vibrant, almost textural quality to his surfaces. This direct approach made his subjects feel astonishingly alive, as if caught in a split second. Though the true identity of the sitter remains a delightful mystery (and indeed, his title was added much later!), the painting is a celebration of the era's emerging middle-class confidence, challenging the stiffness of traditional portraiture. Hals was a master of capturing the spirit of his sitters, whether it was the dignified burghers, the jovial common folk, or even fellow artists. His portraits are famously devoid of formality, offering a "snapshot" of personality that feels almost photographic in its candidness, centuries before the invention of the camera.

What makes this particular piece so iconic isn't just the sheer technical brilliance, but the way Hals captures such a vivid, almost personal presence. Imagine a young man, resplendent in a richly embroidered silk doublet, with intricate gold thread shimmering across the fabric, his lace collar a snowy flourish at his throat, and his gaze direct and full of an almost mischievous confidence. The rich, intricate details of his silk sleeve, the delicate lace collar, and the elaborate cap all speak to the opulence of the era and the status of the sitter. But it’s the psychological depth, the sense that this is a real person, caught mid-thought, mid-expression, that makes it unforgettable. Is it confidence, arrogance, or simply a fleeting moment of amusement? The ambiguity is part of its lasting charm. Hals wasn't about the grand philosophical statements of Rembrandt or the serene calm of Vermeer; Hals was all about life, caught in a split second. His ability to make paint feel alive, to capture that twinkle in an eye or that slight smirk, a fleeting expression that reveals character, it's a testament to his genius. When I look at his portraits, I almost expect them to start talking, or maybe even burst out laughing! They feel incredibly modern in their psychological depth, decades, if not centuries, ahead of their time. From Vermeer's quiet contemplation, Hals delivers a jolt of joyful energy that is infectious.

4. Jan Steen: The Merry Family

Life's Joyful Chaos, Subtle Morality, and the Art of Visual Storytelling

If Hals captures the outward expression of individual life, Jan Steen invites us into the vibrant, sometimes gloriously chaotic, heart of the Dutch household, mess and all. The Merry Family, painted around 1668, is a perfect example of his boisterous genre paintings. Steen was so renowned for depicting chaotic, bustling households – often with children and adults indulging a bit too freely – that "a Jan Steen household" became a Dutch idiom for a messy, lively home. The original context often involved patrons commissioning these scenes for their homes, perhaps as a gentle, humorous reminder of the virtues of moderation, or simply to delight in the depiction of everyday life, a fascinating aspect of what is genre painting. The subtle narrative threads he weaves into these busy scenes are a masterclass in visual storytelling, presenting a truly human condition. Other artists like Gabriël Metsu and Nicolaes Maes also excelled in genre scenes, though often with a more refined touch, making Steen’s unique boisterousness all the more distinctive.

I've always had a soft spot for Steen. His paintings are like little plays unfolding before your eyes, full of detail, humor, and often, a subtle moral message about moderation or the consequences of indulgence. In The Merry Family, for instance, you see all these folks – eating, drinking, making music, probably making a bit too much noise. Yet, beneath the chaos, Steen often included visual cues, or moral allegories, to prompt reflection. Notice the pipe being offered to a child, a clear symbol of bad example; the young boy's tipsy grin as he raises a glass, mirroring adult behavior; or the proverb hanging above their heads ("As the old sing, so pipe the young"), a direct admonishment about setting a bad example for the next generation. Other common allegories in his work might include symbols of fleeting pleasure like scattered playing cards, or overturned tankards hinting at excess. For contemporary audiences, these visual proverbs and allegories weren't just decorative; they were widely understood, serving as a humorous, yet pointed, commentary on societal norms and the importance of virtue. It's chaotic, sure, but it's also incredibly relatable, even today, reminding me of family gatherings, perhaps a bit less wild, but definitely with that same bustling energy. He captures humanity in all its messy, joyful, and sometimes admonishing forms, making us smile even as we ponder the deeper meaning, showcasing a brilliant understanding of visual storytelling techniques in narrative art. From the spirited chaos of Steen's domestic scenes, we turn our gaze to the majestic, meticulously rendered outdoors.

5. Jacob van Ruisdael: The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede

An Ode to Dutch Ingenuity and the Majesty of the Landscape

Finally, we can't talk about the Dutch Golden Age without talking about their awe-inspiring landscapes – canvases that captured not just nature, but the very soul of the nation. And for me, Jacob van Ruisdael is simply unparalleled, with his iconic The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede (c. 1670). Again, I don't have this particular masterpiece in my immediate image collection, but its essence is easy to evoke. It's a painting that has sparked countless discussions about its powerful composition and symbolism.

This isn't just a picture of a windmill; it's a powerful ode to the Dutch landscape itself, a profound symbol of human ingenuity and resilience. Windmills, in the Netherlands, represent not just practical industry – grinding grain, draining polders (those remarkable tracts of low-lying land reclaimed from the sea or lakes, a monumental feat of engineering essential for a country so low-lying) – but also a deep national pride in shaping the land and harnessing nature's power. They became potent symbols of Dutch identity, representing perseverance, innovation, and the successful struggle against the forces of nature, particularly water. Ruisdael was a master of capturing atmosphere – those vast, dramatic skies often dominating two-thirds of the canvas, the low horizons emphasizing the flat Dutch terrain, and a profound sense of scale that makes you feel both tiny and profoundly connected to something immense. His innovative use of atmospheric perspective, creating a sense of depth and distance through subtle color and tonal shifts, combined with his skill in depicting specific weather conditions and light playing on water, contributed to the dramatic and realistic effect. He masters not just the appearance of the sky, but its feeling – the damp chill, the vastness, the way light breaks through dramatic cloud formations to illuminate a distant landscape. During the Golden Age, landscape painting truly came into its own as a distinct and highly valued genre, reflecting the Dutch people's close connection to their environment and their mastery over it. The way he paints those clouds, the light hitting the windmill just so, the gnarled trees, the shimmering water... it's breathtaking. He makes you feel the wind, the dampness in the air, the deep connection between the land and its people. It's a reminder that beauty isn't just in grand historical narratives or intimate portraits; it's in the world around us, if we just stop to truly see it. This piece, like so many others from its timeline, offers a glimpse into the significant events and artistic developments that shaped the era, embodying the deep pride of a nation over its environment. Another notable landscape artist was Aelbert Cuyp, known for his serene, light-filled river scenes, offering a different, yet equally masterful, perspective on the Dutch landscape.

Echoes in Capturing Nature's Essence, Then and Now

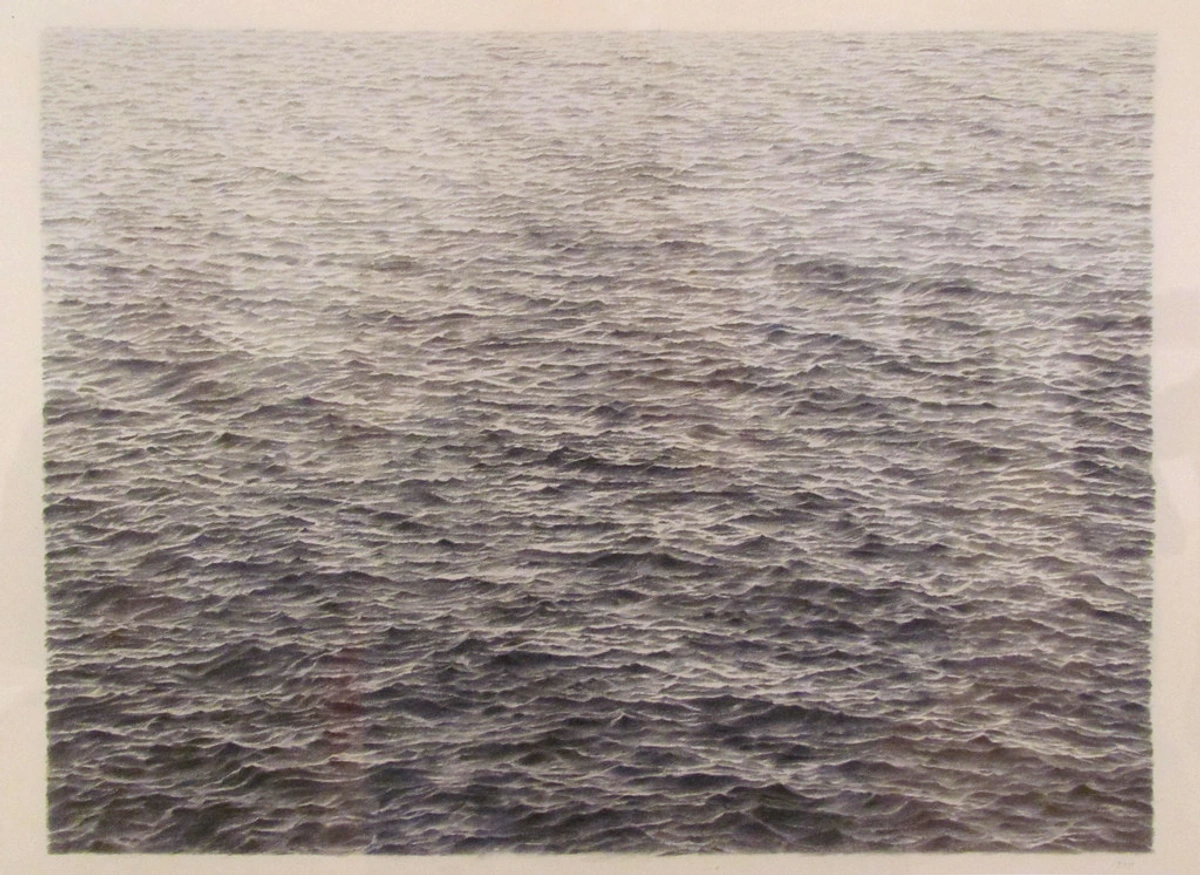

Just as Ruisdael masterfully evoked the vastness and power of nature in the 17th century, contemporary artists continue to find inspiration in the elements. The profound sense of atmosphere and movement he captured in his skies and waters is a testament to the timeless artistic pursuit of rendering the natural world's majesty. We might use different tools or embrace abstraction, but the core challenge of translating nature's dynamic presence onto a canvas (or paper, or screen) remains. When I look at Vija Celmins' meticulous graphite drawings of ocean waves, for example, I sense a similar profound dedication to capturing the subtle, overwhelming power of nature, a quiet contemplation that echoes Ruisdael's atmospheric intensity, despite their vastly different styles. In my own abstract landscapes, I often aim to capture that same sense of elemental power through vast washes of color and textured layers, seeking to evoke the feeling of wind whipping across an open plain or the quiet immensity of a cloudy sky, much like Ruisdael captured the atmosphere of his Dutch skies. By carefully layering analogous blues and grays, or by using energetic, sweeping brushstrokes for my textures, I try to convey the sensation of movement and depth, not just its literal depiction. It’s about conveying how it feels to be in that space, rather than a literal depiction.

Why These Masterpieces Still Matter Today: Echoes in My Art

After diving into these incredible works, it’s only natural to ask: why do these paintings, centuries old, still resonate with us so powerfully? I believe it's because they captured something universally human that transcends their specific time and place. Whether it's the raw drama of a civic guard, the enigmatic gaze of a girl, the infectious joy of a cavalier, the lively chaos of a family, or the serene majesty of a landscape, they show us glimpses of life, emotion, and identity that are deeply familiar. The raw drama of The Night Watch speaks to our innate sense of community and duty, while Vermeer's introspective gaze taps into our universal capacity for quiet contemplation and inner reflection, often evoking a sense of calm and mystery. Steen's lively chaos reminds us of the enduring, often messy, joy of human connection and family. These are not just historical artifacts; they are enduring dialogues about the human condition.

They also teach us about enduring artistic principles. Here are some of the key lessons that still inform my own artistic journey, and frankly, can inform anyone's appreciation or creation of art:

Mastering Light and Shadow: The Illusion of Reality and Emotion

The dramatic use of chiaroscuro to create emotional depth, as seen in Rembrandt's Night Watch, taught me how to guide the viewer's eye and amplify narrative tension, making a scene feel both urgent and deeply human. It's a powerful tool, not just for realism, but for creating a specific mood or directing focus. Likewise, Vermeer’s delicate interplay of light and shadow, evoking such profound intimacy in Girl with a Pearl Earring, showed me the sheer power of subtlety and nuanced observation, making her gaze feel alive with unspoken thoughts. For my own work, whether abstract or more representational, the balance between light and shadow, the way they define form and create atmosphere, is a constant fascination, a core element of composition and fundamental to understanding light in art. For instance, in my abstract piece "Luminous Divide," I use stark contrasts between deep indigo and bright gold to create a similar emotional drama, guiding the eye through the canvas just as Rembrandt illuminates his central figures.

The Human Condition Unveiled: Expression and Psychology

Frans Hals, with his expressive spontaneity of brushwork, captured character in The Laughing Cavalier in a way that truly liberated me. It's a testament to embracing vitality and less rigid forms in my own work. His ability to convey psychological depth with just a few swift strokes taught me that art doesn't have to be perfectly rendered to be profoundly true. His portraits feel like candid photographs, capturing that split-second flicker of personality that we often see in modern photography. I aim to convey raw emotion through bold gestures and energetic marks, rather than relying solely on precise rendering. In my abstract portraits, I use thick, impasto brushstrokes and vibrant, sometimes clashing, colors to capture a similar untamed energy, allowing the viewer to feel the presence of a personality rather than merely seeing a likeness. These works remind me that the essence of humanity – its fleeting emotions, its inner life – is a boundless source of artistic inspiration.

Narrative Through Everyday Life: Stories in the Mundane

Jan Steen's rich narrative detail in capturing human foibles, as he does in The Merry Family, reminds me that even abstract art can tell a story or evoke a human condition. His paintings are a masterclass in embedding meaning within seemingly simple scenes. Think also of artists like Pieter de Hooch or Gerard ter Borch, who excelled at capturing quiet domestic moments imbued with subtle social commentary. It’s about more than just depicting what’s there; it’s about revealing the hidden layers, the quiet dramas, or the humorous ironies of daily existence. This principle of visual storytelling—making the seemingly ordinary profound—is a core tenet of my approach to visual storytelling techniques in narrative art. In my own abstract narratives, I often layer seemingly disparate forms and colors, creating a chaotic yet harmonious composition that mirrors the beautiful messiness of human interaction, inviting the viewer to find their own stories within the canvas.

The Majesty of Nature: Connecting with the World Around Us

Finally, the atmospheric grandeur of Jacob van Ruisdael’s Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede, conveying such a profound connection to nature and human endeavor, has a direct parallel in my contemporary landscape abstracts. I often use layered washes and analogous colors to create a similar sense of vastness and emotional connection, evoking the sprawling scale of nature much like Ruisdael did with his commanding skies. The way I blend deep blues into lighter grays, or use textured greens and browns, directly aims to capture the damp chill and expansive feeling of a natural environment, much like Ruisdael captured the dramatic Dutch weather. It’s about capturing not just what a landscape looks like, but how it feels – the wind, the space, the sheer presence of the natural world. These masters remind me that art, whether a 17th-century masterpiece or one of my contemporary pieces, is about connection – connecting us to history, to emotion, and to each other. They make you feel something, and that, to me, is the ultimate goal of any artwork.

The Lasting Legacy: Dutch Golden Age Art's Impact on Art History

It's impossible to discuss the Dutch Golden Age without acknowledging its colossal influence on subsequent art movements and artists. This period wasn't just a golden moment in isolation; it laid foundational groundwork that echoed through centuries, setting precedents that continue to shape how we create and appreciate art today.

Here's a look at how this vibrant era cast its long shadow:

Aspect of Influence | Description | Later Art Movements/Artists Influenced |

|---|---|---|

| Shift in Patronage | The rise of a robust art market and middle-class patronage fundamentally altered the relationship between artist and buyer, moving from church/royalty commissions to an open market. This fostered artistic autonomy and specialization. | Prefigured modern art markets; encouraged diverse subject matter that appealed to broader audiences (e.g., 19th-century Realism, Impressionism's focus on contemporary life). |

| Everyday Life as Subject (Genre Painting) | The elevation of genre painting to a respected art form profoundly influenced later artists by demonstrating the richness and narrative potential of ordinary life, domestic scenes, and social interactions. | 19th-century Realists (e.g., Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet) and Impressionists (e.g., Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet) who likewise found inspiration in contemporary, mundane life. |

| Mastery of Light and Atmosphere | Techniques developed by Rembrandt (chiaroscuro) and Vermeer (subtle domestic light, luminous effects) in manipulating light and shadow became cornerstones of artistic training and inspiration for centuries. | Spanish Baroque masters (e.g., Velázquez), Romantic painters (e.g., J.M.W. Turner's atmospheric effects), Impressionists (e.g., Claude Monet's obsession with light), and even early photographers. |

| Landscape as a Primary Genre | The Dutch Golden Age established landscape painting as a standalone, respected genre, moving beyond mere background elements. Artists like Ruisdael depicted nature with dramatic realism and profound emotional resonance. | Romantic painters (e.g., John Constable, Caspar David Friedrich) who used landscape to evoke emotion and national identity; later influenced Abstract Expressionists (e.g., Mark Rothko's vast color fields as emotional landscapes). |

| The Power of the Individual Portrait | Hals's ability to imbue his portraits with vibrant personality and psychological depth, capturing fleeting expressions and inner life, pushed the boundaries of portraiture beyond mere status depiction. | Later portraitists seeking to capture psychological realism (e.g., Francisco Goya, Édouard Manet), and ultimately influenced the candidness of early photography. |

The Dutch Golden Age, therefore, isn't just a chapter in art history; it's a living dialogue, continuously informing how we perceive and create art, celebrating the profound beauty in the human experience and the world around us. Its legacy is etched into the very fabric of visual culture.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dutch Golden Age Art

What defines Dutch Golden Age art?

Oh, that's a fantastic question! For me, it's about a few key things that truly set it apart, reflecting the unique socio-economic and cultural landscape of the 17th-century Netherlands:

- Realism & Naturalism: Artists meticulously aimed to depict the world as it truly was, often with astounding detail, moving away from idealized forms found in much other European art. The era's advancements in optics and perspective, championed by thinkers like Snellius and Stevin, directly informed artists' ability to create convincing illusions of three-dimensional space and realistic light effects.

- Genre Painting: There was a huge boom in scenes of everyday life – from bustling taverns and lively households to quiet domestic moments or kitchen maids preparing food – often subtly conveying moral lessons. This directly reflected the values and interests of the burgeoning middle-class patrons and the influence of Protestantism (Calvinism), making genre painting a staple.

- Portraits: Both grand group portraits of civic guards (like The Night Watch) and intimate individual likenesses flourished, showcasing the wealth, status, and individual piety of the merchant class, often with profound psychological depth.

- Landscapes & Seascapes: A celebration of the unique Dutch environment, with vast, dramatic skies, iconic windmills, and dynamic seascapes. These often conveyed a strong sense of national identity and pride in their hard-won, reclaimed land and mastery over the elements. Marine painting, in particular, became a distinct and vital genre, celebrating the Dutch Republic's maritime power and global trade, often featuring ships, naval battles, and bustling ports.

- Still Lifes: Meticulously detailed arrangements of objects, often serving as vanitas (somber reminders of life's transience and memento mori, reinforcing the concept of contemptus mundi – contempt for the world) or showcasing earthly prosperity and luxury (pronkstilleven with exotic goods, silks, porcelain imported by the VOC and WIC). This is a rich area of study in the art of still life painting.

- The Art Market: Unlike other parts of Europe where the church and royalty dominated patronage, a thriving open market for art developed in the Netherlands, with dealers, auctions, and even traveling salesmen making art surprisingly accessible to the middle class. This profoundly influenced subject matter and artistic production, encouraging specialization within genres.

- Printmaking: The widespread use of printmaking made art accessible to an even wider audience, disseminating artistic styles, popularizing imagery, and spreading ideas efficiently.

- Unique Political Structure: As a republic rather than a monarchy, the Dutch Republic fostered a different kind of patronage and artistic freedom, leading to themes celebrating civic life and individual enterprise rather than solely royal or ecclesiastical grandeur.

- Protestant Reformation Influence: The tenets of the Reformation, particularly Calvinism, led to a shift away from grand religious altarpieces and highly stylized iconography towards more humble, relatable biblical scenes and an emphasis on virtuous daily life, profoundly impacting subject matter and artistic interpretation.

This period marked a significant shift where the middle class became major art patrons, rather than just the church or royalty, which profoundly influenced the subjects and styles artists pursued.

Who were the most famous artists of the Dutch Golden Age?

Well, as you've met some of my absolute favorites already, here’s a broader look at the giants of the era, whose interconnected works shaped an artistic revolution:

- Rembrandt van Rijn: A titan, practically synonymous with the era for his dramatic use of light (chiaroscuro), profound psychological insight, and revolutionary approach to portraiture and historical painting. His later self-portraits are masterpieces of introspection.

- Johannes Vermeer: The enigmatic master of capturing light and domestic tranquility, whose works feel like hushed secrets, known for his luminous interiors and enigmatic figures. His meticulous technique and masterful rendering of light transformed ordinary domestic scenes into moments of sublime beauty.

- Frans Hals: Renowned for his incredibly lively portraits that seem to breathe, capturing fleeting expressions and individual personalities with spontaneous, energetic brushwork (often alla prima). His portraits are celebrated for their direct, engaging portrayal of his sitters' personalities.

- Jan Steen: Known for his humorous and often moralizing genre scenes, offering lively, detailed narratives of everyday Dutch life, full of implied stories and gentle admonishments.

- Jacob van Ruisdael: Unparalleled for his incredible, atmospheric landscapes that make you feel the wind and damp air, elevating landscape painting to new heights of dramatic grandeur and national pride.

Beyond these titans, talents like Pieter de Hooch (whose serene domestic scenes are a masterclass in light and perspective, focusing on quiet interiors and spatial arrangements), Gerard ter Borch (known for his exquisite rendering of textiles and elegant genre scenes of courtship and polite society, often depicting the upper middle class), Willem Kalf (a master of opulent still lifes, or pronkstilleven, displaying luxurious imported goods like Chinese porcelain and precious silverware), Adriaen van Ostade (famous for his lively, often boisterous scenes of peasant life, offering a glimpse into the lower echelons of Dutch society), and Philips Wouwerman (renowned for his elegant equestrian scenes, battle pieces, and hunting parties, often featuring distinctive white horses) were also immensely skilled and contributed significantly to the era's diverse artistic output.

Where can I see Dutch Golden Age artworks?

The Netherlands, of course, is the absolute heartland! The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is an absolute must-see, home to The Night Watch, numerous Rembrandts (including The Jewish Bride), and countless other treasures, providing a comprehensive overview. The Mauritshuis in The Hague is where you'll find Girl with a Pearl Earring and a superb collection of other masterpieces in an intimate setting (including Fabritius's The Goldfinch). The Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem is, as you might guess, the place to immerse yourself in Hals's vibrant portraits, including his famous civic guard pieces. And then there are many other fantastic regional museums across the Netherlands that showcase incredible Golden Age works.

Beyond that, major art institutions worldwide – from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (with a significant collection including Vermeer's The Milkmaid and numerous Rembrandts), the National Gallery in London (housing works by Rembrandt, Frans Hals, and others), the Louvre Museum in Paris, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago – boast significant collections. Honestly, for the major works, it's often a pilgrimage worth making! I always recommend checking museum websites for specific artists or artworks before you go, as collections can shift for exhibitions.

What about common misconceptions about the Dutch Golden Age?

That's a fantastic point! One common misconception is that it was only about secular art. While religious themes were less dominant than in Catholic Europe due to Calvinism, biblical stories and mythological themes were still depicted, often in a more personal, less overtly dramatic style (e.g., Rembrandt's biblical scenes). Another myth is that it was a period of uninterrupted peace and prosperity; remember, the Eighty Years' War had just concluded, and political and economic challenges (like ongoing naval wars with England and fluctuating trade) were always present.

It's also a misconception that the Dutch Golden Age was solely about material wealth and ostentatious display. While prosperity certainly played a role, much of the art, particularly the genre scenes and still lifes, often carried underlying moral messages about humility, the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures (vanitas), or the dangers of excess. The art reflects a complex society grappling with its newfound independence and wealth, sometimes serving as a visual moral compass or a reminder of spiritual values. It was a vibrant, complex, and sometimes contradictory time, much like our own! Also, it's a misconception that all art produced was 'high art'; there was a broad spectrum, from refined masterpieces to more common, mass-produced prints and simpler genre paintings catering to various budgets, reflecting the widespread accessibility of art.

What role did light play in Dutch Golden Age painting?

Oh, light was absolutely paramount! Dutch Golden Age artists were unparalleled masters of rendering light, transforming it into a central element of their compositions. They didn't just illuminate a scene; they painted the light itself, making it feel tangible and atmospheric. This was partly due to the era's scientific curiosity and advancements in optics – the study of how light behaves – but also to a profound artistic sensitivity and understanding of color theory. Artists like Vermeer, for instance, became synonymous with capturing diffused, domestic light, making interiors glow with an almost sacred calm and creating a sense of peace and domestic sanctity, conveying quiet introspection and subtle drama. Rembrandt used chiaroscuro to dramatic effect, creating intense contrasts between light and shadow to heighten emotion, guide the viewer's eye, and sculpt figures with psychological depth, almost as if illuminating a theatrical stage. Even in landscapes, artists like Ruisdael masterfully depicted the changing qualities of natural light across vast skies and water, giving their scenes immense depth and realism. This mastery of light, and the way it was used to create both hyper-realism and profound emotional impact, profoundly influenced later movements, most notably Impressionism, where artists obsessed over capturing fleeting moments of light. Understanding how they manipulated light is key to appreciating the profound realism and emotional power of their work, and it's a technique that still informs how we perceive and create art today, as it's fundamental to definitive guide to understanding light in art.

What are some common themes and motifs in Dutch Golden Age art?

Ah, this is where the art truly speaks volumes about the society! You'll often spot recurring elements that carried deep meaning for contemporary viewers:

- Vanitas & Memento Mori: Skulls, extinguished candles, hourglasses, decaying flowers, and even bubbles were common in still lifes, serving as somber reminders of life's brevity, the transience of earthly pleasures, and the inevitability of death. They reinforced the concept of contemptus mundi (contempt for the world), urging viewers to focus on the spiritual over the material.

- Domesticity & Family: Many genre scenes celebrated home life, children, and the virtues of a well-ordered household, reflecting Calvinist values and the importance of the family unit, and the aspirations of the rising middle class to display their virtue and success. Proverbial sayings were often visually embedded as subtle moral lessons.

- Wealth & Trade: Exotic goods like imported silks, spices, porcelain, or intricate silver and glass items in still lifes, or opulent attire in portraits, proudly displayed the nation's immense prosperity gleaned from global trade. These pronkstilleven (ostentatious still lifes) were clear status symbols, yet often subtly warned against material excess, hinting at the fleeting nature of such riches.

- The Sea & Civic Pride (Marine Painting): Given the Netherlands' reliance on the sea for trade, defense, and even land reclamation, marine painting became a hugely popular and distinct genre. Depictions of ships, naval battles, and bustling ports symbolized national pride, maritime power, and the nation's hard-won independence. Artists like Willem van de Velde the Younger excelled in this genre.

- Moral Allegories: Beyond the obvious, many seemingly innocent scenes contained hidden moral messages or proverbs, encouraging diligence, moderation, or warning against vice. Look closely, and you'll often find a subtle teaching moment or a visual puzzle for the discerning viewer, a testament to the era's fascination with symbolism and layered meaning.

These motifs weren't just decorative; they were woven into the fabric of daily life and thought, offering both beauty and profound commentary.

How did Dutch Golden Age artists create their masterpieces?

It's fascinating to peer into their creative process! While each master had their unique flair, some common threads emerged, emphasizing both meticulous planning and technical skill:

- Underdrawings & Preparatory Work: Many artists would start with detailed underdrawings, often in chalk or charcoal, or preparatory sketches and cartoons, to plan their compositions meticulously before applying paint. This laid the foundation for their precise realism and complex arrangements.

- Oil Paints & Glazing: Oil paints were the dominant medium, allowing for rich, luminous colors and incredible detail. Artists often built up layers of thin, transparent glazes to achieve depth, subtle transitions, and that characteristic inner glow, especially evident in Vermeer's work. They would laboriously grind their own pigments (like lead white, vermilion, and precious lapis lazuli for ultramarine – a color so expensive it was sometimes reserved for specific, high-paying commissions!) and mix them with linseed oil.

- Impasto: Some, like Rembrandt and Hals, were masters of impasto, applying thick, textured paint, particularly in highlights or areas of textural interest (like the lace on a collar or the glint in an eye), to create a palpable sense of reality and dynamic energy. This made surfaces almost leap off the canvas.

- Studio Practice & Apprenticeships: Most artists worked from their studios, often using models for figures or carefully arranged still life setups. Apprenticeships were common, where young artists learned techniques by assisting their masters, grinding pigments, preparing canvases, and copying prints. It was a rigorous, hands-on education, emphasizing craft and observation. Artists were often members of local guilds, like the Guild of Saint Luke, which regulated artistic training, sales, and professional standards, ensuring quality and protecting members.

- Scientific Observation & Tools: There was a strong emphasis on keenly observing the world – light, shadow, anatomy, perspective – and translating that observation with remarkable accuracy onto the canvas. Some, like Vermeer, are even theorized to have used optical devices like the camera obscura to aid in rendering perspective and light effects with such precision. Their art was deeply rooted in the empirical spirit of the age, combining scientific inquiry with artistic expression.

A Timeless Echo in Our Modern World

So, whether you're standing before a colossal Rembrandt, pondering a quiet Vermeer, or simply reflecting on an image of a Ruisdael landscape, I hope you feel that profound connection too. This art isn't just history; it's a living, breathing testament to human creativity, ingenuity, and the endless pursuit of capturing beauty and truth. It truly makes you think about how we interpret the world around us – the light, the emotion, the narratives, both grand and intimate. Reflecting on these masters, I'm consistently inspired to translate that same spirit of deep observation and emotional resonance into my own contemporary works. The principles of light, narrative, and expressive form are not confined to the 17th century; they are the very foundations upon which I build my vibrant abstract pieces, seeking to create that same enduring connection with the viewer. By studying their masterful control of composition, their evocative use of color, and their dedication to conveying meaning, I find endless possibilities for my own artistic explorations.

These Golden Age masterpieces remind us that the core challenges and joys of art are timeless. They invite us not just to look, but to truly see—to observe the world with fresh eyes, to understand the depths of human emotion, and to find the extraordinary in the seemingly ordinary. So, I urge you to seek out these incredible works, whether in person or through further exploration. Immerse yourself in their stories, their light, their sheer humanity. And perhaps, like me, you'll find that their timeless echoes inspire you not just to appreciate art, but to create it. The canvas awaits your own unique dialogue with the world, ready for you to shape the next chapter of visual storytelling techniques in narrative art.