Still Life Art: History, Evolution, & My Artistic Journey

Explore still life art's fascinating evolution from ancient rituals to modern digital forms. Discover its hidden meanings, impact on artists like me, and why these quiet arrangements still speak volumes.

The Evolving Narrative of Still Life: From Ancient Rituals to Modern Artistry

Let's be candid for a moment. For years, the phrase “still life” brought to mind dusty fruit bowls or flowers that were, well, still. It felt a bit like the art world's beige wallpaper – present, but rarely thrilling. But here’s my confession: I was spectacularly wrong. As an artist constantly seeking deeper meaning in the mundane, that realization struck me like a perfectly placed highlight. Once I started digging, I discovered the history of still life isn't just a quiet parade of apples and dead game; it’s a vibrant, ever-evolving mirror of human life, philosophy, and our endless fascination with the objects around us. It's about unearthing profound narratives in the humblest of subjects. But as I delved deeper, I discovered that this seemingly simple art form is a rich tapestry woven through millennia of human history and thought. Join me as we unravel how still life transformed from ancient, practical depictions to a powerhouse of modern artistic experimentation, connecting us to stories both grand and intimately personal. Let's uncover why these quiet arrangements truly speak volumes.

The Quiet Beginnings: Still Life Before It Knew Its Name

It’s easy to think of still life as a purely European invention, but its roots stretch back further than you might imagine. It’s a realization that dawns on you, isn’t it? Humans have always been surrounded by objects, and we’ve always felt this urge to represent them, to give them a voice, a presence. We see glimpses of still life elements as far back as ancient Egyptian tombs, where depicted offerings of food, drink, and symbolic items like lotus flowers or geese were meant to sustain the deceased in the afterlife. These weren’t just pretty pictures; they were practical depictions imbued with profound spiritual significance, ensuring continuity beyond physical life. Beyond the Nile, ancient Greek pottery featured everyday items like fruit and ritual objects, integral to narratives or cultural practices. And then there are the incredible frescoes of Pompeii and Herculaneum, showing everyday items like fruit bowls, jugs, and game birds. These often decorated Roman villas, sometimes as a welcoming display known as xenia – a custom of hospitality where guests were presented with gifts of food and objects, often to demonstrate the host’s wealth and generosity. What a fascinating way to use art to convey social standing, right? While these weren’t ‘still life paintings’ in the modern sense—they were often decorative or part of a larger narrative—they certainly show an appreciation for rendering inanimate objects with remarkable skill. This skill in rendering textures and forms also served as vital artistic training for more complex narrative scenes.

And let’s not forget the rich, diverse traditions of still life elements in East Asian art. Centuries ago, Chinese ink wash paintings of flowers and birds emerged, celebrating nature’s transient beauty and symbolic power, often imbued with philosophical depth through intricate brushwork. Similarly, in Japanese ukiyo-e prints, we find exquisite depictions of domestic objects, food, and floral arrangements, integral to daily life and often conveying subtle cultural narratives or seasonal beauty. We also find intricate floral and domestic object depictions in Persian miniatures and Indian paintings, showcasing a universal human impulse to dignify the everyday. Moving through the medieval period, objects mostly served as potent symbols, embedded within religious scenes – a skull at the foot of a crucifixion, a book held by a saint, or a lily symbolizing purity. We also see early instances in illuminated manuscripts and altarpieces, where everyday objects or flowers were meticulously rendered, adding layers of symbolic meaning to sacred narratives. It wasn’t until the Renaissance that artists began to depict these elements with unprecedented naturalism and realism. This careful observation, this quiet dignifying of objects, prepared the ground for what was to come: still life blossoming into an independent and powerful art form, especially in the Netherlands. It’s almost like the art world was slowly, quietly getting ready for its big still life reveal, wouldn't you say? This early appreciation for the tangible world, whether for ritual, display, or training, laid the quiet groundwork for still life’s dramatic emergence as an independent genre.

The Golden Age Glow-Up: Dutch Masters and Memento Mori

But what happened when still life truly came into its own, becoming a genre worthy of deep contemplation? If still life painting had a coming-out party, it was definitely in the 17th-century Netherlands. This, I can tell you, was its Golden Age. These artists took the humble arrangement of objects and turned it into a major artistic genre. It’s fascinating, really, how a societal shift – the rise of a wealthy merchant class, the decline of extensive church patronage – led to such an explosion of domestic and secular art. Early innovators like Jan Brueghel the Elder, who infused his elaborate floral bouquets with symbolic meaning, paved the way for a generation of masters. Artists like Pieter Claesz, Willem Kalf, and even pioneering women like Clara Peeters, whose intricate arrangements defied expectations, not only created masterpieces but also navigated a male-dominated art world, often contributing significantly to the genre's development. This era also saw the flourishing of flower still lifes (bloemstukken), celebrating the transient beauty of nature, often with meticulously rendered botanical accuracy – a precision often influenced by the burgeoning fields of scientific illustration and botanical studies. It's as if they were painting both a beautiful picture and a scientific record, all at once! If you're as fascinated by this period as I am, you absolutely have to check out my deeper dive into the Dutch Golden Age of Painting.

Dutch and Flemish artists weren't just painting pretty pictures; they were masters of subtle, layered symbolism. Those lavish banquets, gleaming silver, exotic shells, and wilting flowers? They were often vanitas paintings – powerful, sometimes melancholic, reminders of life's fleeting nature, the inevitability of death, and the emptiness of worldly pleasures. Each object a whisper about time and mortality, if you only knew how to listen:

Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Skulls, hourglasses, extinguished candles | Direct symbols of mortality, the fleeting nature of life, and the unstoppable march of time. It really makes you pause, doesn't it? |

| Wilting flowers, decaying fruit | The ultimate metaphors for transience, decay, and the ephemerality of beauty – nothing lasts forever, even in a painting. |

| Half-peeled lemons | A personal favorite. This one speaks to life's bitterness, yes, but also sensory pleasure, inviting contemplation of both the good and the bad. |

| Open books | Often representing knowledge or spiritual life, but sometimes, ironically, the futility of worldly learning in the face of eternity. |

| Exotic shells, silver, fine textiles | The ultimate display of wealth and worldly pleasures, often contrasted with their ultimate emptiness and inability to stave off death. |

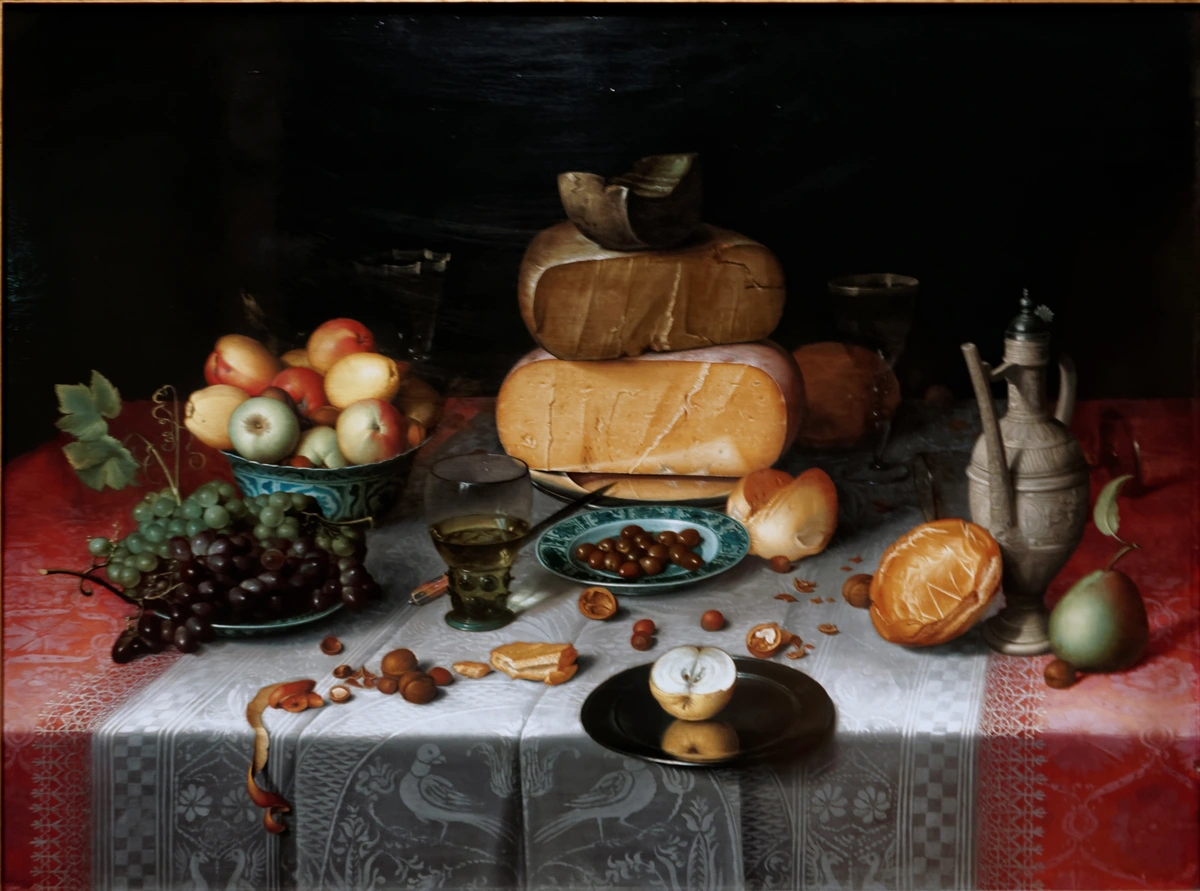

Floris van Dijck, licence

In contrast, pronkstilleven, or "ostentatious still lifes," were all about showcasing wealth and exotic goods, celebrating material abundance rather than critiquing it. Think opulent displays of imported spices, gleaming porcelain from China, elaborate silverware, and sumptuous textiles. While vanitas whispered of death, pronkstilleven shouted about success – a fascinating duality within the same genre! And then there were the simpler, elegant "breakfast pieces" (ontbijtjes) depicting everyday meals with exquisite realism, finding beauty in a humble loaf of bread or a glass of wine. It makes you think about what objects we surround ourselves with, doesn't it? And what stories they tell about us, intentionally or not.

Unknown, licence

This period was a masterclass in treating objects not just as subjects, but as characters in a larger human drama. From exotic shells symbolizing global trade to wilting flowers representing fleeting beauty, every element was carefully chosen. Sometimes, even surprising subjects made their way onto the canvas, like the fascinating detail in works depicting rayfish, reminding us of the rich diversity of life and the artists' remarkable ability to find beauty in the unexpected. This rich symbolic language and masterful technique set the stage for a more intimate exploration of the everyday, a path that would be further refined in the centuries to come.

A Touch of Enlightenment: Chardin and the Everyday Sublime

Fast forward to the 18th century, and the still life takes a more intimate, almost humble turn. After the opulent symbolism of the Dutch Golden Age, it found new poetry, particularly with the French master Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. He moved away from grand pronouncements, focusing instead on the quiet dignity of everyday objects – a loaf of bread, a bottle of wine, a simple ceramic pot. His paintings weren't about grand narratives or moralizing; they were about light, texture, and the sheer beauty of the mundane. Chardin was a master of his craft, often using a limited, subtle palette and building up incredible texture through masterful applications of impasto, making you almost feel the worn surface of a jug or the softness of a peach. He made you see the poetry in a half-eaten peach, the subtle sheen on a copper pot, or the worn texture of a simple jug, a way of seeing that I constantly strive for in my own art. Chardin's quiet mastery profoundly influenced later artists like Gustave Courbet, who championed realism, and especially Paul Cézanne, who found in Chardin's humble compositions a template for meticulous observation and the dignifying of everyday subjects, proving that domestic scenes could hold as much artistic weight as historical or mythological subjects. His work is a wonderful lesson in finding the extraordinary in the ordinary, a testament to the power of careful composition. Chardin's quiet revolution, this dignifying of the everyday, subtly paved the way for artists who would soon shatter conventions entirely, finding new ways to see and represent the objects around us. This quiet dignifying of the everyday laid the groundwork for a seismic shift in artistic perception, preparing the stage for the radical explorations of the modern era.

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, licence

Breaking the Mold: Still Life in the Age of Modernism

The 19th and 20th centuries? That’s when artists truly broke free, pushing the boundaries of what still life could be, transforming it from a canvas for quiet observation into a vibrant laboratory for radical artistic experimentation. It became a playground for exploring new theories of color, form, and perspective. While Impressionists like Monet and Renoir might be best known for their landscapes, they also dabbled in still life, capturing fleeting light and atmospheric effects on everyday objects, infusing them with a sense of momentary beauty. Then came Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh, who used still life to imbue humble objects with raw emotion and vibrant color, or Gauguin, who employed them for deep symbolic meaning in his exotic compositions. And then, there's Cézanne, with his meticulous studies of apples and oranges, who fundamentally changed how we perceive objects in space. He wasn't just painting what he saw; he was painting what he knows about the objects, exploring their underlying geometric structure and suggesting multiple viewpoints within a single composition. This meticulous deconstruction of reality, this idea of presenting an apple as if you’ve walked around it and seen it from every angle simultaneously, laid much of the groundwork for Cubism. Indeed, it directly influenced how artists like Picasso and Braque would later fragment and reassemble objects in their early Cubist still lifes, transforming the genre. It’s a fascinating thought, isn't it? How an artist can paint the idea of an apple rather than just its appearance.

Fauvism: A Riot of Color

Then came the Fauves, literally "wild beasts," who threw out conventional color in favor of intense, expressive hues. Imagine still life objects drenched in colors that don't match reality but scream emotion! Henri Matisse, a titan of Fauvism, often used still life arrangements to experiment with flat planes of vibrant color and decorative patterns, challenging the very idea of realistic representation. It's a fantastic example of art breaking free from literal depiction. If you’re curious about this vibrant movement, you can explore more in my guide to Fauvism.

Henri Matisse, licence

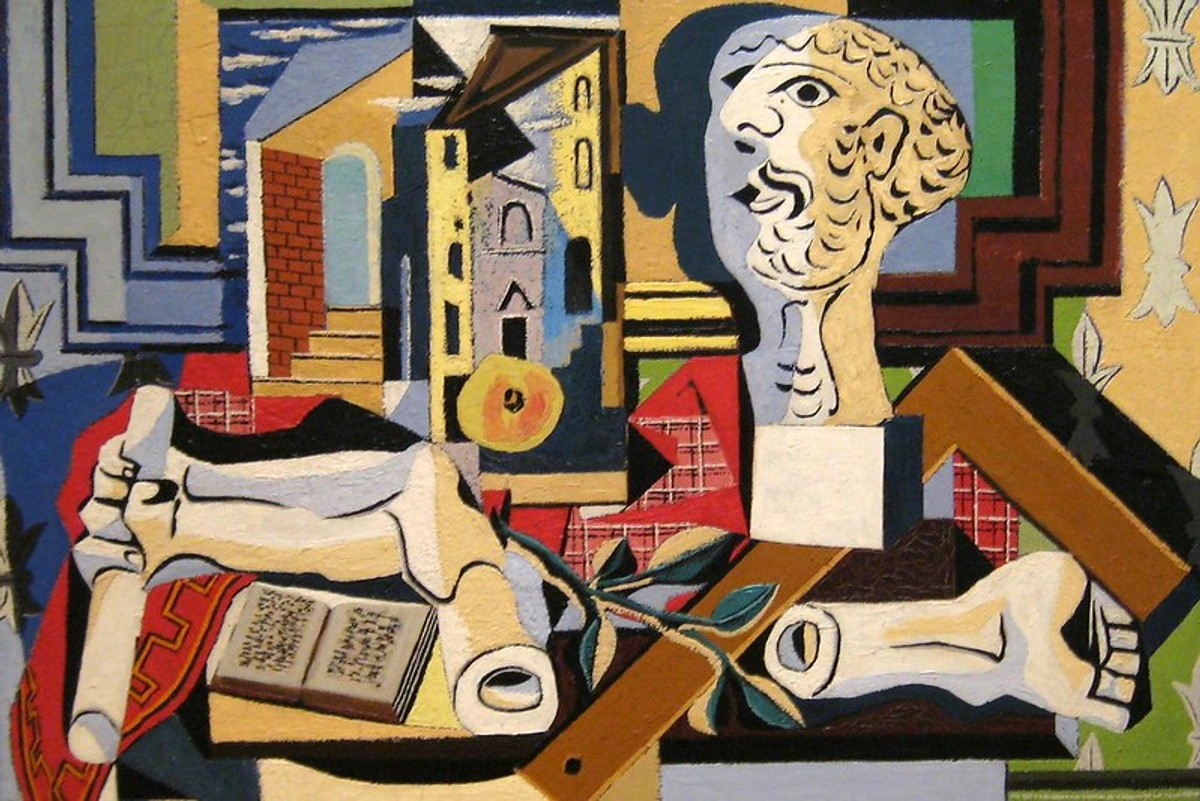

Cubism: Seeing Objects from All Sides

And then, Cubism. My goodness, Cubism completely shattered the traditional single viewpoint! Artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque took objects – guitars, bottles, fruit – and broke them down into geometric planes, reassembling them to show multiple perspectives simultaneously. It’s like looking at a sculpture from every angle simultaneously, but flattened onto a canvas. It was a revolutionary way of thinking about form and space, directly challenging the single-point perspective that had dominated art for centuries. It’s remarkable to think that this radical approach to art began with the humble still life. Dive deeper into this game-changing movement with my Ultimate Guide to Cubism and also check out The Definitive Guide to Understanding Abstract Art Movements.

Pablo Picasso, licence

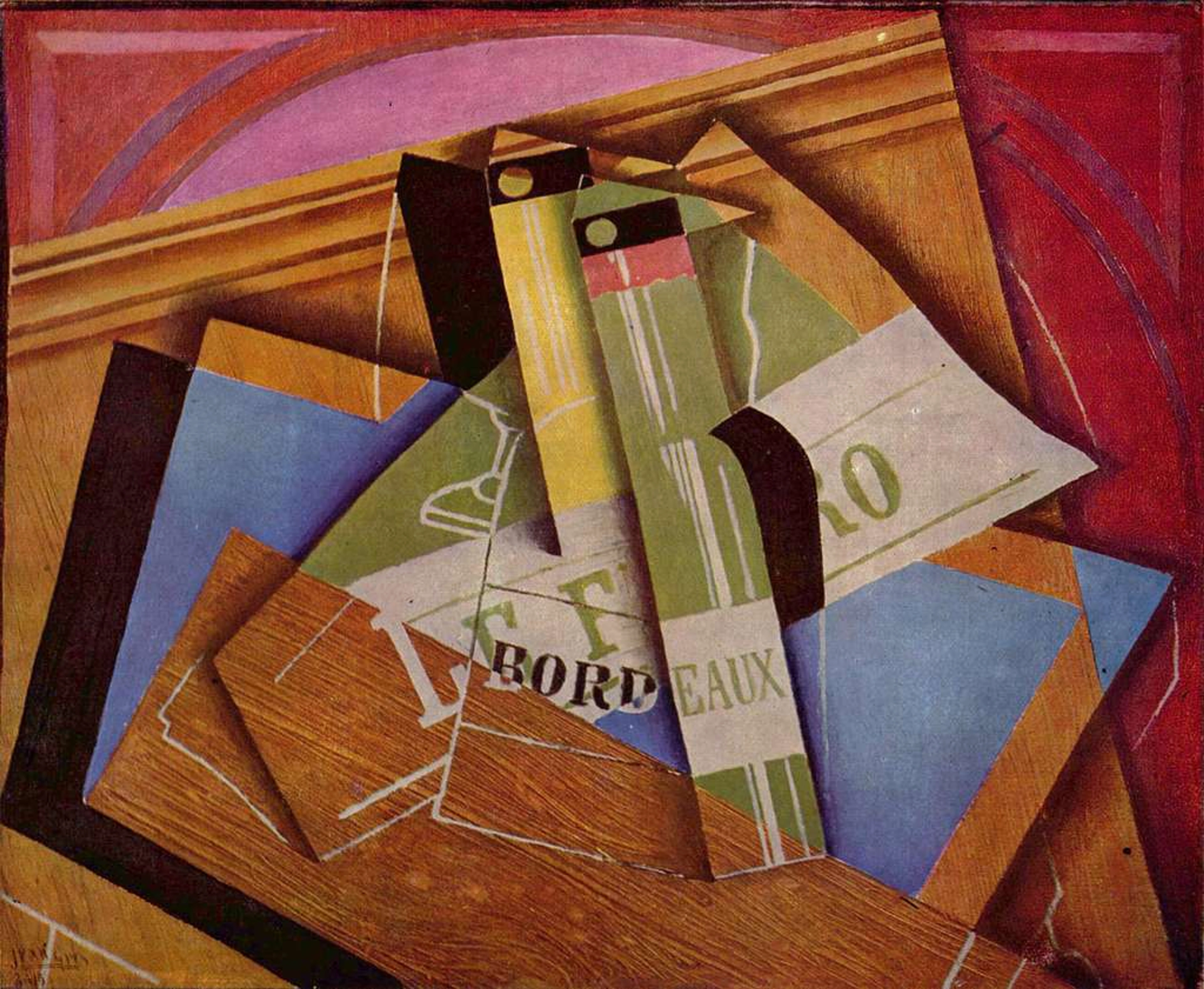

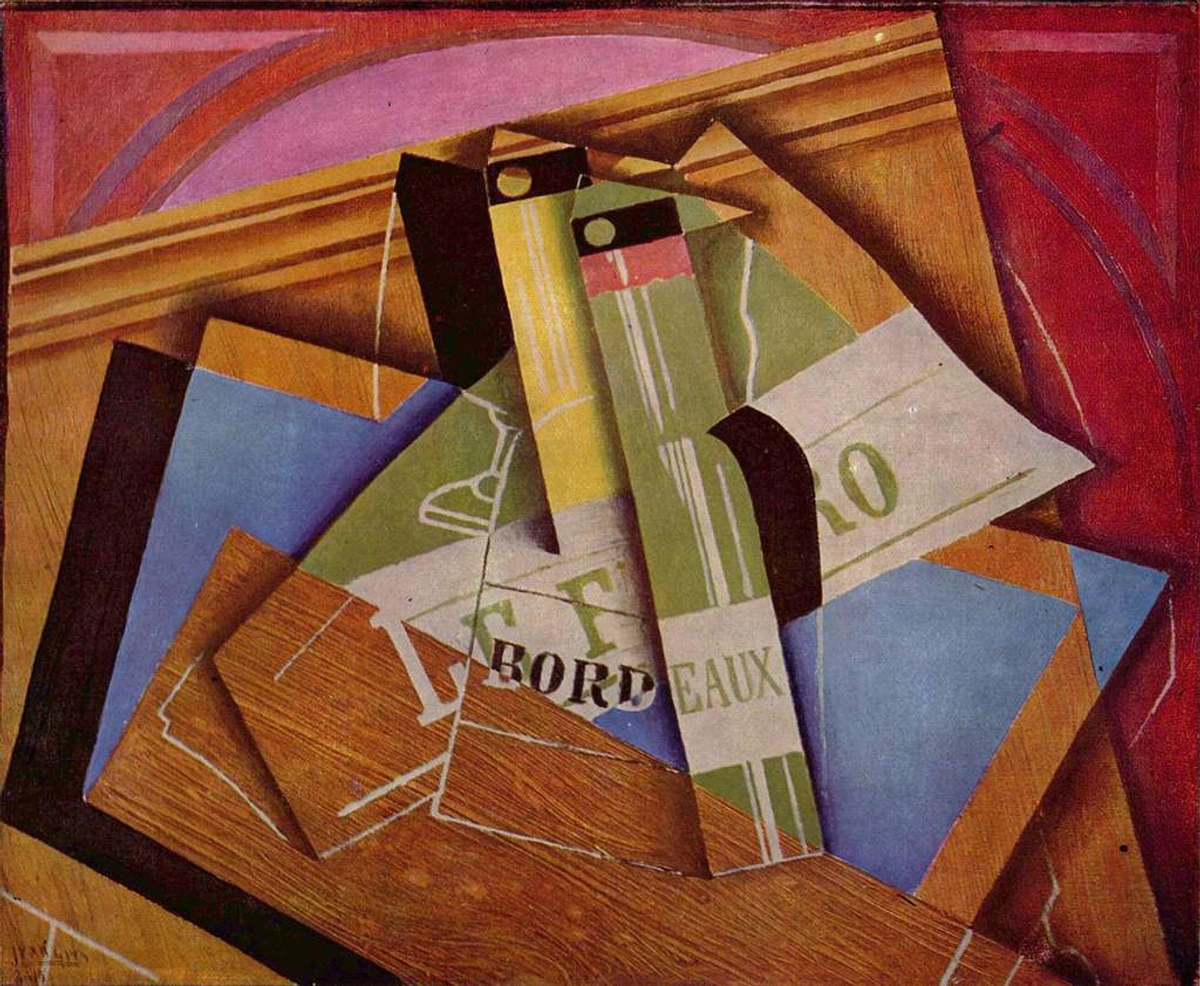

This fragmentation wasn't just about showing an object from all sides, but about conveying the idea of it, the essence of its form and presence in space, rather than a single fleeting view. Artists like Juan Gris brought a distinct elegance to this geometric deconstruction, often incorporating text and patterns to further blur the lines between reality and representation, inviting us to actively participate in piecing together the visual information.

http://www.digitale-bibliothek.de/, licence

Beyond these giants, the 20th century also saw Surrealist still life, where artists like Salvador Dalí used everyday objects in dreamlike, often unsettling arrangements to explore the subconscious mind. Surrealists gravitated towards still life because the inherent familiarity of everyday objects made their distortion all the more jarring and impactful, forcing viewers to confront the bizarre within the mundane. While Dalí's "melting clocks" are perhaps his most famous, works like Meret Oppenheim's iconic fur-covered teacup, saucer, and spoon showed how mundane objects, twisted into new realities, could challenge our very perception of reality itself. Think also of René Magritte's "The Treachery of Images" (Ceci n'est pas une pipe), a still life of a pipe that questions the very nature of representation. If you're curious to unravel more of these dreamscapes, my Ultimate Guide to Surrealism offers a deeper dive. It's a testament to the genre's incredible versatility, isn't it?

The advent of photography also profoundly impacted still life in the 20th century, not just as an influence on painting, but as a distinct medium in its own right. In its earliest days, photographers like William Henry Fox Talbot and Roger Fenton used still life compositions to explore the capabilities of the new medium, carefully arranging objects to master light, shadow, and composition. This parallel development influenced painters to push beyond pure realism towards conceptual or expressive interpretations, acknowledging that the camera could now handle documentary representation, freeing them to explore deeper meanings and subjective truths. Later, artists like Edward Weston's pepper series or Irving Penn's detailed arrangements elevated photographic still life to a high art form, proving its unique power to capture beauty and convey meaning. For a more complete picture, check out my article on The History of Photography as Fine Art.

These radical departures didn't just change how objects were depicted; they fundamentally altered the very purpose and potential of still life as an artistic genre, leading us to its current, multifaceted form.

The Echoes of Objects: Still Life Today and My Own Journey

So, what does "still life" even mean in a world that’s constantly in motion, saturated with digital images and fleeting trends? Still life is far from 'still.' It continues to evolve, pushing into abstraction, photography, installation art, and digital realms. Contemporary artists use it to comment on consumerism (think the hyperrealist paintings of supermarket aisles by artists like Tjalf Sparnaay, where the sheer detail elevates the mundane to a critical statement on abundance and waste, echoing the moralizing undertones of vanitas, or the meticulously arranged mass-produced packaging in installations by artists like Tom Sachs, who directly challenges our relationship with objects), identity (through personal objects, almost like a silent portraiture of objects revealing the owner's story, as seen in the work of Wolfgang Tillmans), and the environment (found objects, trash as subject matter, like the powerful assemblages of artists such as Vik Muniz). We even see its principles constantly in advertising, where meticulously arranged products, bathed in perfect light, vie for our attention. These contemporary critiques often echo the moralizing undertones of vanitas paintings, demonstrating how still life has always been a mirror reflecting our societal values, anxieties, and aspirations. It’s no longer just about rendering; it’s about questioning, provoking, and transforming. It's about how the objects we choose to highlight, even mundane ones, can speak volumes about our culture and ourselves. And as art expands into digital realms, we now see still life explored through AI-generated imagery, virtual reality experiences, and sculpture, further stretching its definition and impact.

As an artist myself, the principles of still life – thoughtful arrangement, light, texture, and symbolic weight – are foundational, even when my work ventures into abstraction. Just as Sparnaay might hyper-focus on a mundane object to provoke thought, I often start with a similar intense observation, but then transform it. It’s not just about balancing colors; it’s about capturing the essence of an object or a moment, even when translated into pure abstraction. It’s the quiet contemplation of form and its emotional resonance that drives my initial brushstrokes, a way of giving even unseen narratives a physical presence. Whether it's the careful balancing of colors or the deliberate placement of forms, the act of composing is still life's enduring legacy. And frankly, understanding the principles of still life composition is something every artist, regardless of genre, should explore. It informs so much of what I do. My abstract floral works, for instance, often begin with that same contemplative gaze at an object, a feeling, or an arrangement, transforming it through color and form into something new, yet still carrying the echo of its origin. It’s a bit like giving an old soul a new, vibrant outfit.

Zen Dageraad, licence

Still Life: More Than Just "Still"

So, my initial dismissiveness? Utterly misplaced. The journey of still life painting is a testament to art's ability to constantly reinvent itself, to find profound meaning in the overlooked, and to reflect the shifting tides of human experience. From ancient offerings to Dutch vanitas and pronkstilleven to Cubist deconstructions and even contemporary critiques of consumerism, still life has consistently offered artists a profound stage to explore big ideas through small, intimate subjects. It’s a silent conversation between objects, light, and the human condition, continuing to unfold even now, inspiring artists like myself to find profound echoes in the everyday. If you're curious about how these principles shape my own work, you might enjoy exploring my latest art for sale to see these ideas in practice, or learn more about my artistic journey and what inspires me. And if you're ever in the Netherlands, don't forget to visit my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch for a truly immersive experience where you can see these concepts come to life, and perhaps even inspire your own discovery of the extraordinary in the ordinary. Thank you for coming along on this little adventure with me. Keep looking for the extraordinary in the seemingly ordinary – it’s always there, waiting to be discovered.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Curious to solidify your understanding? Here are some common questions I hear about still life art:

What is a still life painting?

A still life painting depicts inanimate objects, typically common household items, natural objects (like food, flowers, dead animals), or man-made artifacts arranged on a surface. The term comes from the Dutch stilleven, meaning "still life" or "motionless model."

What is the purpose of still life?

The 'why' behind still life has shifted quite a bit over the centuries! Originally:

- Decorative or Symbolic: In Egyptian tombs or Roman xenia, for spiritual significance or hospitality.

- Moralistic: During the Dutch Golden Age (vanitas, pronkstilleven), conveying messages about mortality or wealth.

- Artistic Exploration: Later, a vehicle for artists to explore composition, light, texture, color, and form.

- Foundational Training: Crucially, it has always been a vital practice for artists to hone observational skills, hand-eye coordination, and an understanding of form, light, and composition. This rigorous practice is invaluable, sharpening an artist's eye to nuances of reality and serving as a critical stepping stone for more complex subjects like portraiture or landscape. Many masters started here!

- Social Commentary: In modern times, used to challenge perceptions and comment on society, identity, or the environment.

What are common symbols in Dutch Golden Age still life?

Dutch Golden Age still life is rich with symbolism. Common symbols include skulls, hourglasses, or extinguished candles (representing mortality and the fleeting nature of life – vanitas); wilting flowers or decaying fruit (transience, decay); half-peeled lemons (life's bitterness, but also taste/sensory pleasure); open books (knowledge, spiritual life); and exotic shells, silver, or fine textiles (wealth, worldly pleasures).

What is the difference between still life and other art genres?

Unlike portraiture (which focuses on depicting people), landscape (which depicts natural scenery), or genre painting (which illustrates scenes of everyday human life), still life painting is exclusively dedicated to the depiction of inanimate objects. These objects are typically arranged by the artist to create a specific composition, allowing for a focused exploration of form, light, texture, and symbolism.

What are the different types of still life?

While the umbrella term "still life" covers a broad range, common sub-genres and themes include: Vanitas (symbolic reminders of mortality), Pronkstilleven (ostentatious displays of wealth), Breakfast Pieces (ontbijtjes - humble meals), Flower Still Lifes (bloemstukken), Trompe l'oeil (to "deceive the eye" with hyperrealistic depictions), and Game Pieces (depicting hunted animals). Each type offers a unique lens through which to explore objects and their meanings.

Who are some famous still life artists?

Key still life artists include:

- Jan Brueghel the Elder (Flemish Baroque, early floral still lifes)

- Pieter Claesz (Dutch Golden Age, vanitas)

- Willem Kalf (Dutch Golden Age)

- Clara Peeters (Dutch Golden Age)

- Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (18th-century French Rococo/Neoclassicism)

- Paul Cézanne (Post-Impressionism, often called the "father of modern art")

- Henri Matisse (Fauvism)

- Pablo Picasso (Cubism)

- Juan Gris (Cubism)

- Salvador Dalí (Surrealism)

- René Magritte (Surrealism)

- Meret Oppenheim (Surrealist object art)

- Tjalf Sparnaay (Contemporary Hyperrealism)

- Wolfgang Tillmans (Contemporary photography, often object-based)

- Tom Sachs (Contemporary sculptor, known for installations with mass-produced items)

How has still life evolved?

Still life evolved from being a minor element in larger works (antiquity, medieval) to an independent, symbolic genre (Dutch Golden Age), then focused on realistic depiction of everyday life (18th century). In the modern era, it became a laboratory for artistic experimentation with color, form, and perspective (Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism), greatly influenced by photography from its earliest days, and later becoming a distinct photographic genre itself. Today it continues to be a versatile medium for expressing contemporary ideas and emotions, often merging with abstraction, photography, installation art, digital art, and remaining a vital tool for art education and commercial applications.

What are the key elements of a still life composition?

Effective still life composition typically involves careful consideration of several elements: arrangement (how objects are placed relative to each other to create visual balance and rhythm), lighting (how light and shadow define form and mood, guiding the viewer's eye), texture (the tactile quality of surfaces, adding realism and interest), color (palette choices and harmonies, evoking emotion), form (the three-dimensional shapes of objects), and space (positive and negative space, depth, to create a cohesive scene). The goal is to create visual harmony, guide the viewer's eye, and evoke a particular feeling or narrative.