The Enduring Allure of Still Life: Art, History, and Personal Meaning

Join an artist's personal journey through still life painting, from ancient symbolism and Dutch masterpieces to modernist experiments and contemporary digital art. Discover its timeless appeal and profound meaning.

The Enduring Allure of Still Life: A Personal Journey Through Time and Canvas

I'll be honest with you, still life painting wasn't always my jam. For the longest time, when someone mentioned "still life," my mind immediately conjured dusty bowls of fruit or melancholic arrangements of dead game. It felt... well, a bit stuffy, like something from a neglected corner of an old art history textbook that didn't quite speak to my more modern, abstract sensibilities. (I mean, who really wants to stare at wilting flowers and a decaying lemon for hours? My own patience often runs out just looking at a wilting fern on my windowsill.) But, as I've found with so many things in art (and life, if I'm being truly honest), my initial dismissal was a sign of my own limited understanding. The deeper I looked, the more I realised still life isn't just about depicting objects; it's about intention, narrative, and finding profound meaning in the seemingly mundane. It's about taking a moment, literally, and freezing it for eternity. So, in this article, I'm inviting you on a journey through the evolution of still life, from its ancient roots to its vibrant contemporary forms, exploring its enduring relevance, profound symbolism, and the diverse ways it has been reimagined across centuries. My aim is to show you why this humble genre continues to captivate artists and viewers alike, and how it mirrors our own quest for meaning in the everyday.

What Even Is Still Life, Anyway? A Reconsideration

So, what exactly are we talking about when we say "still life"? At its core, it's a work of art depicting inanimate objects, typically common ones. Sounds simple, right? But the magic happens in the arrangement, the lighting, the symbolism, and the story the artist chooses to tell. It’s an incredibly deliberate act where every object's placement, light, and context are carefully chosen to craft a narrative or evoke a feeling. Think of it like setting a stage for a tiny play, where each prop speaks volumes without uttering a word. I remember feeling a bit like a detective when I first started truly seeing still life paintings – trying to decipher the clues left by the artist in every object placement. It's not just about what you see, it's about what you don't see, or what's implied.

Echoes from Antiquity: Where Did It All Begin?

Believe it or not, still life isn't some invention of European painting. We see glimpses of it way back in ancient Egyptian tombs, where depictions of food and offerings ensured the deceased would have provisions in the afterlife. Even earlier, in Mesopotamian art, stylized depictions of offerings or banquet scenes on cylinder seals or monumental reliefs hinted at this tradition. The Romans were also quite taken with it, often using still life elements in frescoes and mosaics to showcase hospitality or abundance. Think of those beautifully rendered pomegranates, fish, bread, or even amphorae in Pompeii and Herculaneum – practical, yes, but also a testament to observing the world around them. And here's a fascinating detail: the Romans were also masters of trompe-l'œil still life. This "trick of the eye" created illusions that made objects seem incredibly real, almost inviting you to reach out and touch them, hinting at the genre's potential for engaging viewers beyond mere documentation. Beyond Egypt and Rome, hints of still life appeared in ancient Greek funerary art and later in Etruscan tombs, often depicting everyday items to accompany the deceased or to decorate living spaces. And even earlier, the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations adorned their palace frescoes with vibrant depictions of flora, fauna, and marine life – think dazzling dolphins, intricate lilies, or exotic birds – capturing the aesthetic beauty and cultural importance of carefully observed natural elements, often hinting at spiritual or ceremonial significance. It's fascinating to me how even then, the arrangement of everyday items held cultural weight.

Beyond the Mediterranean, we find rich still life traditions in ancient Chinese art. Far from mere decoration, objects in Chinese still life often carried deep philosophical and spiritual meaning. Think of paintings of bamboo, symbolizing resilience; orchids, representing scholarly purity; or chrysanthemums, embodying nobility. These weren't just pretty pictures; they were visual poems, often steeped in Daoist or Buddhist principles, reflecting a profound connection to nature and a contemplative worldview. While these works weren't always isolated still lifes in the Western sense, their meticulous focus on specific objects and their symbolic resonance laid a powerful foundation, distinct from the more purely functional or religious depictions often seen elsewhere.

From these early, often functional or deeply symbolic beginnings, still life spent centuries as a supporting act. It wasn't considered a major genre, often relegated to the background of larger historical or religious scenes, or used as a foundational exercise in art schools to train aspiring artists in observation and technique. It was a humble, quiet presence for a long, long time. But all that was about to change. It wasn't until a specific era – you guessed it, the Dutch Golden Age – that it truly stepped into the spotlight, becoming a celebrated and deeply symbolic genre in its own right.

The Golden Glow of the Dutch Golden Age

Now, if you ask most people about the peak of still life, they'll likely point to the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age, and rightly so. This era was a veritable explosion of still life mastery. The rise of Protestantism in the Netherlands, which discouraged grand religious art, created a vacuum. Instead, a burgeoning merchant class desired art for their homes, seeking pieces that reflected their prosperity, domestic values, and newly acquired global tastes, leading to a flourishing of secular genres like still life. This new patronage celebrated domesticity, everyday life, and the nation's newfound wealth and global reach.

Artists like Willem Kalf and Jan van Huysum, but also the masterful Pieter Claesz with his muted 'breakfast pieces' and the vibrant floral arrangements of Rachel Ruysch, elevated the genre to incredible heights. Claesz's "breakfast pieces," for example, often featured humble, half-eaten meals – a crust of bread, a glass of wine, pewter plates – rendered with exquisite realism, focusing on the transient beauty of simple objects, subtly reminding viewers of the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures and life itself, even amidst abundance. Ruysch, on the other hand, was celebrated for her intricate and scientifically accurate floral still lifes, often including tiny insects and dew drops, highlighting the ephemeral nature of beauty and life itself. Her work, alongside others, also mirrored the precision of contemporary botanical illustrations and anatomical studies, reflecting the era's fascination with natural history and scientific discovery, proving that art and science often dance hand-in-hand. It was also a time of immense global trade for the Dutch, bringing exotic new objects – from spices to rare shells and porcelain – into everyday life, and consequently, onto canvases. These new, intriguing objects added layers of intrigue, symbolism, and a rich exploration of texture and materiality, reflecting the nation's burgeoning wealth and international reach. Artists painstakingly rendered the gleam of silver, the delicate translucence of a grape, the softness of a feather. This wasn't just about depicting what was seen; it was about the sensation of these objects, their tangible presence.

But here’s the kicker: those luscious fruits, gleaming silver goblets, and exotic flowers weren't just pretty pictures. Oh no. The Dutch masters were absolute maestros of symbolism.

Take a vanitas painting, for example. I'm sure you've seen them: skulls, decaying fruit, snuffed-out candles, maybe an hourglass or a wilting flower. A classic example like Harmen Steenwyck's 'Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life' often uses these elements to subtly, sometimes not-so-subtly, remind us of life's fleeting nature, the inevitability of death, and the futility of worldly possessions. Other common vanitas symbols included bubbles (representing the brevity of life), musical instruments (the transience of earthly pleasures), and books (the limited nature of human knowledge). It's a profound, if slightly heavy, message for a dinner table, making you ponder what truly lasts. It’s a far cry from just a bowl of apples when you realize those apples might be a metaphor for the passage of time. Beyond their profound philosophical messages, these works were highly sought after, reflecting not just moral lessons, but also serving as luxury items and status symbols that showcased a patron's wealth and sophisticated taste, making them highly desirable for their collectible value and market appeal. Owning a beautifully rendered vanitas wasn't just about contemplating mortality; it was a statement of intellectual and financial standing.

In a strange way, even when I'm working on something entirely abstract, I often find myself thinking about composition and the interplay of elements, much like a still life painter arranges objects. For me, it's all about making sense of the visual world, even if that sense is purely aesthetic or emotional, rather than strictly representational. You can learn more about how artists wrestle with these foundational concepts in articles like what is design in art.

Still Life's Shifting Sands: The 18th and 19th Centuries

As we rolled into the 18th and 19th centuries, still life continued to evolve, albeit often taking a backseat to historical and portraiture painting. Despite being considered a "lesser" genre by academic hierarchies, it quietly gained traction as a subject worthy of serious study and exhibition in the burgeoning salons. Artists found ways to infuse it with fresh perspectives. Think of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin in France, whose humble domestic scenes of simple foodstuffs and kitchen utensils, like "The Ray" or "Basket of Wild Strawberries," elevated the everyday to an art form, reflecting the quiet dignity of bourgeois life, and often implying moral virtues of order, frugality, and honest labor within the home. Or consider the detailed botanical illustrations of the era, which blended scientific observation with artistic precision, creating still life works of immense clarity and beauty. The humble table setting started to reflect bourgeois life, or perhaps a more scientific, detailed observation of nature. Towards the end of the 19th century, even the Impressionists dabbled in still life, using familiar objects like flowers and fruit to experiment with light, color, and brushwork, capturing fleeting moments and atmospheres rather than rigid forms.

Yet, as artistic trends continued their relentless march through the art world, still life would soon undergo an even more radical transformation, moving beyond mere representation to become a laboratory for perception itself. The stage was set for a true revolution.

The Modernist Revolution: Still Life as Experiment

But the true earthquake in still life arrived with the modernists, and boy, did they shake things up! The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw artists like Paul Cézanne using still life to explore form, color, and perspective in revolutionary ways. He wasn't just painting apples; he was dissecting their very essence, making them look like they'd been through a geometry lesson! He challenged how we perceive three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface. His approach, particularly his "passage" technique where forms visually merge and bleed into one another – almost blurring the edges between objects and their backgrounds – and his focus on underlying geometric forms and structure, was a pivotal step that directly paved the way for abstraction. Cézanne's innovative use of multiple viewpoints within a single composition and his reduction of objects to their fundamental geometric shapes directly challenged centuries of traditional perspective, essentially handing the baton to the Cubists.

![]()

Even earlier, the Fauves, like Henri Matisse in his vibrant early still lifes, used objects as a pretext for expressive, non-naturalistic color, proving that a bowl of fruit could be an explosion of emotional intensity, a riot of feeling rather than just a study in light and shade.

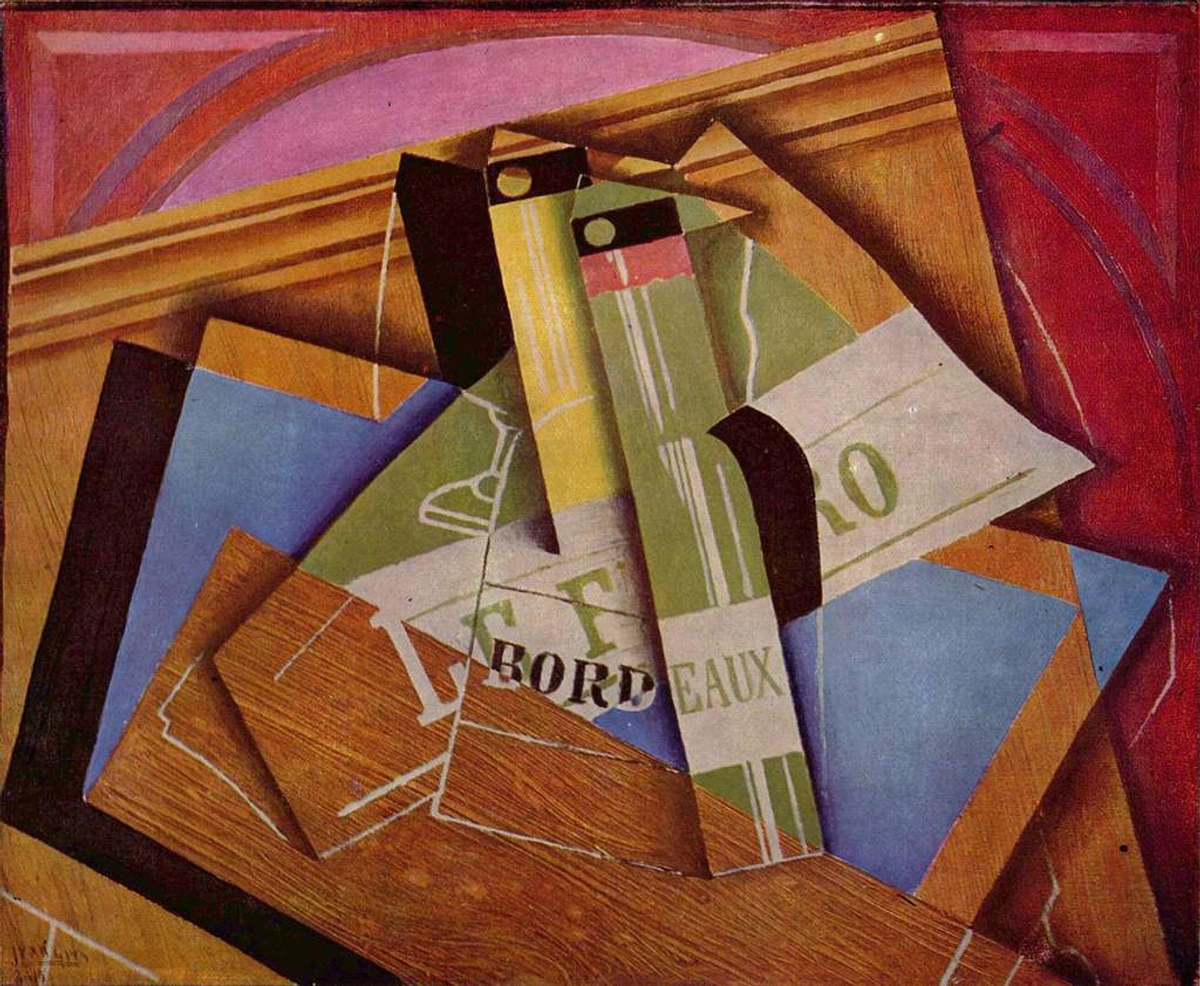

This deconstruction of objects, breaking them into multiple facets and views, directly informed the revolutionary approach of Cubism. My article on the ultimate guide to Cubism delves deep into how artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque took this deconstruction even further, often using still life objects as their experimental playground.

Braque, in particular, with his more muted palettes and emphasis on tactile sensation, helped to define Analytical Cubism's quiet revolution, showing how still life could be a laboratory for new ways of seeing. His frequent use of everyday objects like musical instruments, pipes, and bottles in fragmented compositions transformed the mundane into a profound intellectual puzzle.

The 20th century really took still life on a wild ride. Surrealists twisted everyday objects into dreamlike scenarios, often questioning reality itself, much like René Magritte's iconic "The Treachery of Images" which, though not a traditional still life, famously stated "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" beneath a painting of one, forcing us to ponder the very nature of representation and how we see and name objects in art, challenging the viewer's comfortable assumptions about what a still life truly presents. Pop Artists, like Andy Warhol, turned commercial products into iconic works of art. Suddenly, a can of soup was as valid a subject as a bowl of fruit! It was a brilliant, cheeky commentary on consumer culture and the nature of art itself. If you're curious about how art can make such bold statements with everyday items, check out my ultimate guide to Pop Art.

And so, still life, ever adaptable, continued its journey into the present, finding new expressions in our increasingly complex world...

Contemporary Still Life: The Everyday Transformed and Reimagined

Fast forward to today, and still life is more vibrant and diverse than ever. Contemporary artists are using everything from discarded junk to digital detritus. Imagine an AI-generated still life depicting a scattered array of glitching digital icons, broken hyperlinks, abandoned social media profiles, discarded emojis, and pixelated fragments of advertising – essentially, the everyday "junk" of our digital lives – exploring themes of digital consumption, online identity, and the ephemerality of online existence. We see hyperrealistic food sculptures, photographic assemblages, and even digital still life compositions generated by AI. Photographic assemblages, for instance, involve artists meticulously arranging physical objects for a photograph (where the resulting image is the artwork), or creating collages from found photographic elements. Performance-based still life, on the other hand, sees artists interacting with or arranging objects in a live setting, with the action itself (or its documentation) forming the core of the artwork. These new tools and subjects reflect our modern concerns, blurring the lines between the tangible and the virtual, the ephemeral and the permanent. The genre is also increasingly global, with artists from cultures like East Asia often drawing on rich traditions of symbolic objects in arrangements – think the contemplative beauty of Chinese scholar's rocks, the precise, meaningful arrangements of Japanese ikebana, or traditional Chinese paintings depicting auspicious flowers like peonies (symbolizing wealth and honor) or plum blossoms (representing resilience and perseverance). This contrasts with historical Western still life, where a lemon might symbolize bitterness, a skull mortality, or a single snuffed candle, the fleeting nature of life, often with a moralizing undercurrent. In East Asian traditions, the emphasis is more on harmony, spiritual contemplation, and the inherent beauty of nature, often devoid of overt moral judgment.

They're playing with scale, context, and the very idea of what constitutes an object worthy of artistic attention. It’s less about perfect rendering and more about concept, emotion, or social commentary. Artists now often tap into the psychological aspect of how objects, through their arrangement and context, can evoke specific feelings, memories, or subconscious associations – perhaps a forgotten toy conjuring childhood nostalgia, or a mundane tool hinting at unspoken labor. The exploration of texture and materiality also remains paramount, with artists employing diverse media to highlight the tactile qualities and physical presence of their chosen subjects.

I often think about my own artistic process, even though I create mostly abstract works. There's a certain "still life" element to arranging colors, shapes, and textures on a canvas. It's about creating a balanced, compelling composition out of disparate elements, much like a still life painter arranges objects. It’s about finding harmony, or sometimes intentional discord, within a defined space. For me, these arrangements become reflections of internal states, emotional landscapes rather than physical ones. It's a way of saying, "Here are these elements; what story do they tell?" Sometimes, a discarded piece of paper or a collection of random tools on my studio floor will spark an idea, not for a literal painting of those items, but for the feelings they evoke, or the interplay of their forms. It's a modern, abstract take on the traditional still life impulse: seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary, transforming the mundane into the magnificent. If you're curious to see how I approach these ideas in my own work, particularly how abstract compositions can tell their own 'still life' stories, you can explore pieces I have for sale or delve into my personal artist journey. And if you're ever in the Netherlands, you can experience the tangible presence and emotional impact of these concepts in person at my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch.

credit, licence

What everyday objects in your own life might hold a hidden story, just waiting to be observed? How might they tell a tale of your specific time and place?

Why Does Still Life Endure? A Timeless Appeal.

So, after all this journey, why does this humble genre, once dismissed, continue to captivate artists and viewers alike? I've come to believe it boils down to these core strengths, woven through centuries of artistic practice, that truly explain its lasting appeal:

- Accessibility: We all understand objects. They’re universal. A bowl of fruit, a pair of shoes, a cup of coffee – these resonate across cultures and time. This inherent relatability makes still life instantly engaging. Think about how a still life can capture the essence of a specific time or place through the objects depicted – like a Dutch breakfast piece showing the wealth of a merchant home, or a contemporary digital assemblage reflecting our screen-filled lives – acting as a historical or cultural snapshot of an era.

- A Playground for Technique and Materiality: For artists, it's a fantastic way to hone skills in composition, lighting, texture, and color. It's where you learn how artists use color to evoke feeling and form, and how to represent the tactile qualities of different materials – the sheen of metal, the softness of velvet, the translucence of glass, the roughness of stone – and master the illusion of three-dimensionality on a flat canvas, not least through the meticulous study of light and shadow. It's also a fundamental exercise, a kind of artistic "scales" or "warm-up" that allows an artist to refine their eye and hand before tackling more complex subjects like grand historical narratives or portraits. In fact, still life remains a cornerstone of art education for developing observational skills and understanding principles of still life composition. Its presence in the background of portraiture and genre painting, where objects subtly convey a sitter's status, profession, or a scene's narrative, further underscores its versatile importance.

- Metaphorical and Psychological Depth: As we saw with the vanitas paintings and contemporary explorations, objects can be incredibly powerful symbols. They allow for layers of meaning and storytelling, tapping into collective cultural narratives or individual psychological responses without needing human figures, exploring themes from domestic comfort and warmth to poignant unease or even outright philosophical despair.

- A Moment of Pause: In our fast-paced world, a still life forces us to slow down, to observe closely. It asks us to appreciate the beauty, the design, or the inherent meaning in everyday things. It's a quiet rebellion against the constant noise, a moment of contemplative stillness in a chaotic existence. Honestly, who doesn't need a bit of that sometimes?

So, what do you think? Has my journey convinced you to take a second look at the quiet power of still life? I hope so. Because when you do, you'll find a world of stories just waiting for you, frozen in time.

FAQ: Your Still Life Questions, My Humble Answers

Curious for a bit more? Here are some common questions I get about still life, and my honest thoughts:

Q: Is still life still relevant in contemporary art?

A: Absolutely! More than ever, I'd argue. Contemporary artists are pushing the boundaries, using still life as a vehicle for conceptual art, social commentary, and explorations of identity. It's all about reimagining what an "object" can be and what story it can tell.

Q: What's the main difference between a classical still life and a modern one?

A: While classical still life often focused on realism, symbolism (especially moral or religious), and technical virtuosity, modern still life (think Cézanne or Cubism) began to prioritize formal qualities like shape, color, and perspective, often deconstructing objects. Contemporary still life then expands this further, often embracing found objects, digital media, and conceptual ideas over purely aesthetic representation.

Q: Can abstract art be considered a form of still life?

A: That's a fantastic question, and one I ponder often! While not literally depicting inanimate objects, I believe there's a strong conceptual overlap. When I arrange abstract shapes, colors, and textures on a canvas, I'm creating a composition – a deliberate arrangement of elements within a defined space. In a way, it's an abstract still life, freezing a moment of visual thought or emotion much like a traditional still life freezes a physical scene. The key here is the deliberate compositional intent – the artist's mindful choices about placement and relationship – that defines both genres, whether representational or not. Think of Paul Cézanne's later works, which, even without explicit objects, maintain a profound sense of arranged form and material presence, or the compositional balance in Georges Braque's analytical cubist still lifes. This focus on composition as the essence of still life, whether representational or abstract, is key. You can see this tension between objective reality and inner vision in much of abstract expressionism and the definitive guide to understanding abstract art from cubism to contemporary expression.

Q: Did still life influence other art forms, like portraiture or genre painting?

A: Absolutely. Still life elements frequently appeared as background details or symbolic additions in portraits, often conveying the sitter's status, profession, or moral character. In genre painting, still life set the scene, adding realism and narrative clues to everyday domestic life. It was a versatile tool for artists across many genres, demonstrating its fundamental importance.

Q: What are some common challenges artists face when creating still life, and how do they overcome them?

A: Oh, plenty! One big one is making inanimate objects feel alive and engaging. Artists often overcome this by playing with unusual compositions, dramatic lighting, or incorporating symbolic elements that add narrative depth. Another challenge is avoiding 'boring' – which is where abstract principles come in, focusing on the interplay of shapes, colors, and textures rather than just literal representation. A particularly tricky aspect is avoiding sentimentality or cliché when depicting common objects, and instead capturing their unique essence or spirit. Artists often tackle this by using unexpected contexts, ironic juxtapositions, or by infusing the work with a strong conceptual framework that elevates it beyond mere prettiness. It’s about finding the inner rhythm of the objects, not just their outer shell, much like I try to find the inner rhythm in my own abstract compositions.

Q: What's the best way to start appreciating still life painting?

A: My advice? Don't overthink it. Find a still life painting that catches your eye. Then, really look at it. What objects are there? How are they arranged? What colors do you see? What mood does it evoke? And then, if you're up for it, dig a little into the historical context or the artist's intent, perhaps even seeking out the artist's personal connection to the objects depicted. You'll be amazed at the layers you uncover.

The Stillness That Speaks Volumes

So there you have it, my somewhat rambling, deeply felt appreciation for the art of still life. I started this journey as a skeptic, finding the genre "stuffy" and irrelevant to my own artistic leanings. But it’s a genre that taught me not to judge a book by its cover, or a painting by its apparent simplicity. It's shown me that profound stories and complex ideas can be hidden in plain sight, residing in the quiet arrangement of everyday things. It’s a testament to the power of observation and the endless ways we find meaning in the world around us. Perhaps the greatest lesson of still life is that if we only slow down enough, the world around us is always telling a story, waiting for us to listen, much like I've learned to listen to the quiet stories in my own art. It's a journey well worth taking, and I hope you're now a little more inclined to pause and look closely at the "still life" moments in your own life.