What is Watercolor Paint? A Beginner's Guide to Water's Magic

What is watercolor paint? Dive into its unique transparency, luminosity, and versatile magic. This guide covers properties, differences from other paints, and why artists love it. Embrace the flow!

The Luminous World of Watercolor: A Comprehensive Beginner's Guide to Artistry and Expression

Welcome, fellow traveler on the artistic path! If you've ever been captivated by the sheer brilliance of a watercolor painting, or perhaps a little intimidated by its ethereal glow, then you've absolutely landed in the right spot. I remember the first time I truly understood watercolor, not as a paint, but as a living, breathing entity on the paper. It wasn't in a stuffy art history class, nor was it from reading a technical manual. It was a Saturday morning, sun streaming through my window, and I was just messing around with a cheap pan set and some thick paper. I laid down a wash, and instead of opaque coverage, the light seemed to dance through the pigment, reflecting off the white paper beneath. It was a revelation! That's the magic of watercolor, isn't it? It's not about hiding; it's about revealing. It’s a medium that truly breathes with light and movement, a conversation between you, the pigment, and the water – a constant dance of surrender and control.

This delicate interplay of water and pigment is what makes watercolor so captivating, but also, let's be honest, sometimes a little intimidating for beginners. The very transparency that gives it its glow can feel elusive, and the fluid nature of water, well, it has a mind of its own! But don't let that deter you! It's an incredibly approachable medium that profoundly rewards curiosity, a willingness to experiment, and an openness to embrace its unique, often unpredictable, qualities. For those embarking on their artistic journey, understanding the subtle science, the rich history, and the boundless creative potential of watercolor paint is absolutely key. It's a journey into fluidity and light, a medium that truly sets itself apart from all others, offering a unique avenue for both delicate realism and bold abstract expression. This guide aims to be your definitive resource, answering all your burning questions and inspiring you to fearlessly explore the luminous world of watercolor. Consider this your ultimate companion for exploring essential supplies, mastering basic techniques, troubleshooting common challenges, delving into its rich history, and even venturing into advanced mixed media applications, all designed to empower you to create with confidence and joy. By the end, you'll not only understand watercolor, but hopefully, feel a little of its magic for yourself – and maybe even learn to coax it into creating exactly what you envision, or perhaps, even more wonderfully, something entirely unexpected!

Key Characteristics: Understanding Your Paint's Personality

Before we dive into the fundamental components, let's quickly touch on a few key characteristics that define how watercolor pigments behave. Knowing these will give you a head start in anticipating your paint's personality and making informed choices for your artwork. Think of it as getting to know a new friend – each pigment has its quirks, strengths, and subtleties, and understanding them is like learning their love language. This intimate knowledge empowers you to choose the perfect paint for the mood, texture, and intensity you envision in your artwork.

Tinting Strength: How Much Punch Per Drop

Tinting strength refers to a pigment's power to impart its color to a mixture. Think of it as the pigment's inherent 'loudness.' A pigment with high tinting strength, like Phthalo Blue, means a tiny amount will intensely color a large amount of another pigment or water. It's like a concentrated essence – a little goes a very, very long way. Low tinting strength pigments, on the other hand, require more paint to achieve a similar intensity, behaving more like a gentle whisper in a mix. Knowing your pigments' tinting strengths is crucial for efficient color mixing, preventing accidental over-saturation, and saving paint. It allows you to anticipate how a color will behave in a mix, enabling you to build up color gradually for subtle effects or achieve bold statements with minimal effort. I've certainly learned the hard way that a tiny dab of Phthalo Blue goes a very long way, often overpowering other colors if you're not careful!

Granulation: The Textured Whisper

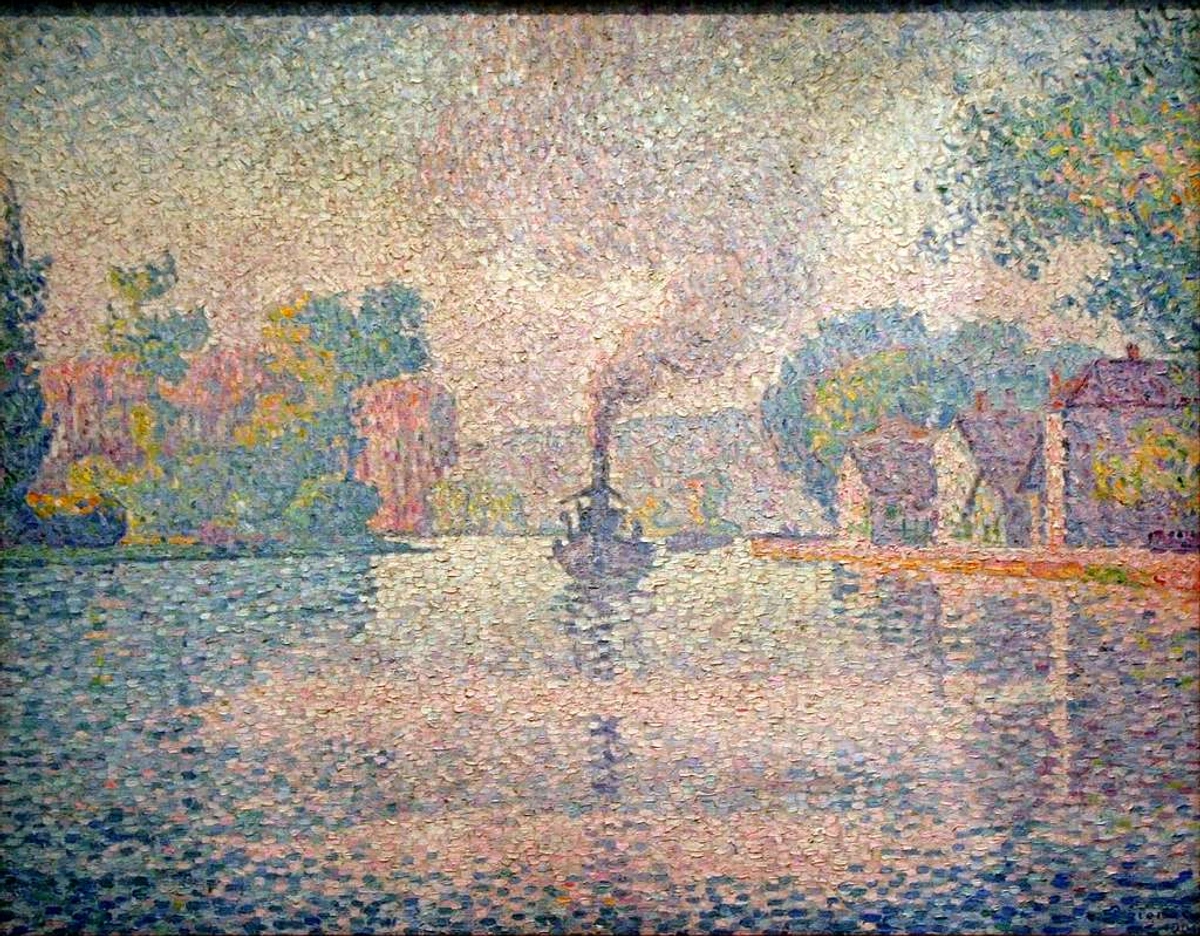

Granulation is a captivating characteristic where pigment particles visibly settle and separate on the paper's surface as the watercolor dries, creating a beautiful, subtle, and often organic texture. Think of it as tiny specks of color clustering together, leaving behind a slightly mottled or sandy appearance, rather than a smooth, uniform wash. This happens because some pigments have larger or heavier particles that don't stay suspended evenly in the water. Ultramarine Blue is a classic granulator, creating a wonderful, almost dusty texture. Other pigments, like Phthalo Blue, are finely milled and disperse smoothly, resulting in flat, even washes. Understanding granulation allows you to harness it for stunning effects – imagine creating the rough texture of ancient stone, the subtle shimmer of sand, or the dappled light on distant foliage, all with the inherent properties of your paint! It's one of those delightful quirks of watercolor that can transform a simple wash into a visually rich and engaging surface, adding character and depth that's hard to replicate otherwise.

Viscosity and Flow: The Paint's Natural Movement

Related to tinting strength is a paint's viscosity—how thick or fluid it is when mixed with water. This impacts its flow across the paper. Imagine honey versus water; that's the range of viscosity we're talking about with pigments. Different pigments inherently have different viscosities, even when mixed with the same water ratio. A thicker, more viscous paint might offer more control for detail work, allowing you to create sharp lines or build textured layers, while a very fluid paint is excellent for broad, even washes, covering large areas with seamless color. Understanding this will help you choose the right pigment for the right technique. For instance, I might grab a more viscous earth tone for textured rocks, allowing it to hold its form and create interesting granular effects, but a free-flowing Viridian for a calm, expansive sky, letting it spread and blend effortlessly. This subtle yet profound difference in flow is a key factor in choosing the right paint for the right artistic intention, from crisp botanical details to expansive, atmospheric landscapes.

The Essence of Watercolor: Pigment, Binder, and a Dash of Magic

At its heart, watercolor paint is incredibly simple, yet capable of profound complexity. Like all paints, it's essentially made of two primary components: pigment and a binder. The magic, as always, is in the details, and with watercolor, it's largely about the binder and how it interacts with water to suspend and release the pigment, transforming it from a dry, inert substance into a vibrant, flowing medium. It's this delicate balance that allows for both precise control and spontaneous, fluid effects, making each brushstroke a potential revelation.

Water is also undeniably a core component of the paint itself, not just a diluent. It's the essential vehicle that brings the pigment and binder to life, enabling the unique flow, transparency, and luminosity that defines watercolor. Without water, it's just colored dust. With water, it becomes a living, breathing entity on your paper, ready to dance.

Pigments: The Soul of Color

Just like in oil paint or acrylic paint, the pigment in watercolor is what gives it its color. These are the finely ground, often microscopic, particles of natural or synthetic materials that absorb certain wavelengths of light and reflect others, giving us the glorious hues we see. Think of vibrant blues from lapis lazuli (or a modern synthetic equivalent) or earthy siennas from iron oxides, each with its own unique origin story and chemical makeup. Pigments can be broadly categorized as organic (derived from carbon compounds, often synthetic, offering high tinting strength and vibrancy, like a brilliant Phthalo Green) or inorganic (derived from minerals or metal oxides, often more subdued, earthy, and famously granulating, such as Ultramarine Blue or a warm Burnt Sienna). Historically, natural pigments were painstakingly ground from minerals, plants, and even insects, a tradition that continues to influence some modern paints, often commanding higher prices for their rarity and unique character. Today, however, synthetic pigments often offer remarkable consistency, a vast spectrum of colors, and frequently boast superior lightfastness, ensuring your artwork endures for generations. The origin of a pigment can tell you a lot about its historical use and its specific properties, from its geological beginnings to its journey through alchemical labs or modern chemical synthesis. For instance, the deep reds and browns of iron oxides have been used since prehistoric cave paintings, while brilliant synthetic pigments like the Phthalos are a marvel of 20th-century chemistry, offering unparalleled saturation and lightfastness. This blend of ancient and modern gives us an incredibly rich palette to work with, each color carrying its own story.

The pigment load—the sheer amount of pigment packed into the binder—is a huge factor in a paint's intensity and vibrancy. It directly impacts how much punch your color has and how far it can spread, dictating how much watercolor magic you get from a single squeeze of a tube or dab of a pan. The quality of the pigment itself—its fineness (how smoothly it disperses), its lightfastness (how well it resists fading over time when exposed to light, a crucial factor for artists selling their work, as we'll discuss later), its intensity, and its particle size—all contribute profoundly to the quality and behavior of the paint. Some pigments are naturally more staining, others lift easily, and some, delightfully, granulate, creating beautiful textures as they dry. Think of a high pigment load as having more concentrated color available to you, meaning you need less paint to achieve vivid results. This high concentration is a key differentiator in artist-grade paints, offering a richness and depth that student-grade alternatives often lack, ultimately providing more value and longevity, making that initial investment truly worthwhile.

You'll often hear about single-pigment paints versus convenience mixes. Single pigments, as their name suggests, contain just one type of pigment. They offer pure, vibrant color and predictable mixing, allowing you to create a vast spectrum of harmonious hues from a small, carefully chosen palette. Convenience mixes, on the other hand, are pre-blended hues, sometimes containing two, three, or even more pigments to achieve a specific shade. While they can be convenient for specific shades when you're in a hurry, for beginners, a mix can initially seem easy, but as you grow in your practice, single pigments quickly become your best friend for clean color mixing and truly understanding color theory. This foundational knowledge empowers you to create any hue you desire without unwanted muddiness. Learning to mix your own colors from a limited palette of single pigments is one of the most rewarding aspects of watercolor, giving you unparalleled control and understanding of your hues. It’s like learning to cook from scratch instead of relying on pre-made sauces – it truly deepens your understanding and allows for endless customization and nuanced expressions.

Pigment Ponderings: Organic vs. Inorganic

Characteristic | Organic Pigments | Inorganic Pigments |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Carbon compounds (often synthetic, from dyes/coal tar) | Minerals, metal oxides, clays (natural or synthetic) |

| Vibrancy | Often very bright, intense, high tinting strength | Tends to be more subdued, earthy, but can be vibrant |

| Transparency | Can be highly transparent or semi-opaque | Often semi-opaque to opaque (e.g., Cadmiums, Cobalts) |

| Granulation | Less prone to granulating, tend to be smooth | Many are famously granulating (e.g., Ultramarines, Cobalts) |

| Staining | Many are strong stainers (e.g., Phthalos, Quinacridones) | Can be staining or non-staining (e.g., Iron Oxides vs. Cadmiums) |

| Lightfastness | Varies, many modern synthetics are excellent | Generally very good, some historical inorganic pigments can be poor |

| Examples | Phthalo Blue, Quinacridone Rose, Hues | Ultramarine Blue, Burnt Sienna, Cadmium Yellow, Cobalt Blue |

This table gives you a quick reference, but remember that individual pigments within each category can still vary wildly in their specific characteristics. For example, not all organic pigments are staining, and some inorganic pigments, like the Cobalts, can be incredibly vibrant. The nuances of each pigment are part of the lifelong learning and discovery in watercolor. Knowing these general tendencies, however, empowers you to predict how a color will behave in a wash or a mix, leading to more intentional and less frustrating creative sessions. It’s about building an intimate relationship with your colors, understanding their personalities so you can truly bring out their best in your artwork.

The Binder: Making it Stick (and Flow)

This is where watercolor really sets itself apart, giving it its unique re-wettability and luminous flow. The primary binder is typically gum arabic, a natural resin derived from acacia trees. Gum arabic is water-soluble, which is absolutely crucial for watercolor's distinctive properties. It acts like a temporary glue, holding the pigment particles together in a dry state (in a pan) or a paste (in a tube). But as soon as you add water, it happily releases them, allowing them to flow freely across your paper with your brush. It's this remarkable property that allows watercolor to be re-wetted so easily, even after drying for years – a practical joy for artists, offering unparalleled flexibility. The quality of the gum arabic itself is also a crucial factor; higher-grade gum arabic, free from impurities, contributes to a smoother flow, better pigment dispersion, and ultimately, more luminous and vibrant washes. Inferior binders can lead to cracking, poor re-wetting, or a dull, chalky finish, diminishing the inherent beauty of the pigments. Other ingredients might be added to fine-tune the paint's behavior, influencing everything from its drying time to its spread and shine:

- Glycerin: Often included in watercolor formulations to keep the paint moist, prevent cracking in pans or tubes (especially in drier climates), and significantly improve re-wetting properties. It acts as a humectant, meaning it attracts and retains moisture from the air, and can subtly extend drying time, which can be a distinct advantage for techniques requiring a longer 'open window' for blending. For pan paints, glycerin is especially vital as it allows the dried paint to readily re-absorb water, making them instantly pliable and responsive with a single brushstroke, transforming a solid block of color into liquid brilliance. Think of it as the paint's personal moisturizer, keeping it supple and ready for action. Beyond just flexibility, glycerin also influences the open time of the paint, meaning how long it stays workable on the palette and on the paper before drying. A slightly longer open time can be invaluable for wet-in-wet techniques or for blending large washes, giving you that precious extra moment to finesse your strokes before the paint sets.

- Ox Gall (or Synthetic Dispersants): A traditional additive (now often synthetic, and animal-free) that acts as a wetting agent. Think of it as a tiny helper that smooths things over. It reduces the surface tension of water, allowing the paint to spread more smoothly and evenly across the paper's surface, preventing frustrating beading, blotchiness, or splotches. It's often essential for achieving those beautiful, unblemished, even washes and can also enhance the luminosity and flow of certain pigments, making the colors appear more vibrant, cohesive, and less likely to shy away from the paper's fibers. Without it, your paint might just sit there, stubbornly refusing to spread, like a shy dancer at a party. The right amount of wetting agent also enhances the color's luminosity, allowing the light to interact more freely with the pigment and paper, intensifying that characteristic watercolor glow. It's truly a subtle but powerful player in achieving professional-looking washes.

- Preservatives: Small amounts are often added to prevent mold growth, especially in tube paints, which contain more moisture and are more susceptible to microbial activity. This ensures the longevity and hygiene of your precious paints, protecting your investment and keeping your studio safe and pleasant. After all, nobody wants fuzzy watercolors! It's the silent guardian against unwelcome biological invaders. While natural alternatives exist, modern preservatives ensure consistent quality and safety, protecting your paints from degradation and allowing you to focus purely on your creative process without worry.

- Fillers/Extenders: In student-grade paints, inexpensive fillers like chalk, dextrin, or even corn syrup may be added to increase volume and lower costs, often at the expense of pigment intensity, vibrancy, and lightfastness. Artist-grade paints, on the other hand, minimize or completely avoid these fillers, ensuring a higher pigment load and pure, concentrated color. This is why a tube of artist-grade paint often costs more but delivers far more concentrated pigment, ultimately providing more value and superior artistic results. It's this intricate balance of binder and additives that makes each brand and even each pigment within a brand unique. Some manufacturers guard their binder recipes closely, leading to subtle but discernible variations in how paints re-wet, flow, and interact with the paper across different brands. Experimenting with various brands can reveal subtle but delightful differences in handling and final appearance, and it's a journey many artists undertake to find their perfect match, much like a chef seeking the perfect ingredient. This delicate interplay of binder, pigment, and additives is what creates the unique 'feel' of a particular watercolor, making the choice of brand a very personal and artistic decision.

The Silent Partner: The Crucial Role of Water

I can't emphasize this enough: water is not just a mixer in watercolor; it's an active participant, a co-creator. It's the solvent that activates the pigment, the vehicle that carries it across the paper, and the force that dictates flow, blending, and texture. Mastering watercolor is less about mastering paint and more about understanding and harnessing the unique properties of water itself. It's truly a dance, where the water leads as often as you do. The ratio of water to pigment is everything, determining the intensity (value) and transparency of your color. Too little water, and your colors will be dense and sticky; too much, and they'll be faint and lack vibrancy. Finding that sweet spot, that perfect milky consistency, is a lifelong pursuit, and part of the joy.

Even the type of water you use can subtly impact your results – and this is where some artists get quite particular! While tap water is generally fine for everyday practice, some artists prefer distilled water to avoid minerals, chlorine, or other impurities that might affect sensitive pigments, especially when working with very delicate colors or in areas with exceptionally hard water. Impurities in tap water can sometimes alter the subtle nuances of certain pigments (causing a slight shift in hue or dullness) or even affect the paper's archival qualities over very long periods. The temperature of your water can also subtly influence flow and re-wetting; slightly warmer water can help re-wet dried pan paints more easily, making them more pliable and releasing pigment more readily, as the warmer water molecules are more active and can break down the dried binder more efficiently. Conversely, colder water might slow down the drying process slightly, giving you more working time for complex blends, or even creating interesting textural effects as it interacts with the paper. Experimenting with these subtle variables can truly unlock new expressive possibilities – sometimes a minor tweak makes all the difference, revealing a new dimension to your artistic voice! I often find that the temperature of my water can subtly shift the mood of a wash, with warmer water encouraging a more expansive, flowing quality, and cooler water allowing for a slightly more controlled, slower diffusion. It's these minute details, this constant dialogue with the elements, that elevates watercolor from a mere painting technique to a profound artistic conversation.

Beyond the Basics: Understanding Watercolor Paint Characteristics

Before we dive into the truly unique properties that define watercolor, it's worth taking a moment to understand some other characteristics that impact how the paint behaves on your paper. This isn't just technical jargon; these qualities will profoundly influence your artistic choices and the final look of your piece. Think of it as knowing your instruments intimately before you compose a symphony. You can learn even more about paint types in our definitive guide to paint types for artists.

Working Time: The Art of the Open Window

Related to a paint's viscosity and the paper's absorbency is its working time – essentially, how long you have to manipulate the paint on the paper before it dries and sets. Some pigments, combined with specific paper types (like slower-drying cotton rag paper) and environmental conditions (high humidity or cooler temperatures), offer a longer 'open window' where you can blend, soften edges, or perform delicate lifting. Others, however, dry almost instantly, demanding swift and confident strokes, almost like a race against time. Understanding and anticipating a pigment's working time is crucial for choosing the right technique; you wouldn't try a complex wet-on-wet blend with a fast-drying pigment on highly absorbent paper unless you're aiming for a very specific, quick, textural effect. For me, it's about knowing when to linger, enjoying the slow dance of colors, and when to make a decisive, confident move before the paint sets forever. Environmental factors, like the humidity in your studio or even the ambient temperature, play a huge role here. In a dry climate, paints dry incredibly fast, demanding speed and efficiency. In humid conditions, you might have a much longer working window, allowing for more expansive wet-on-wet exploration. I’ve certainly learned to adjust my pace when painting on a humid summer day versus a dry winter afternoon – it’s a constant dance with nature’s whims!

Staining vs. Non-Staining (Lifting Properties)

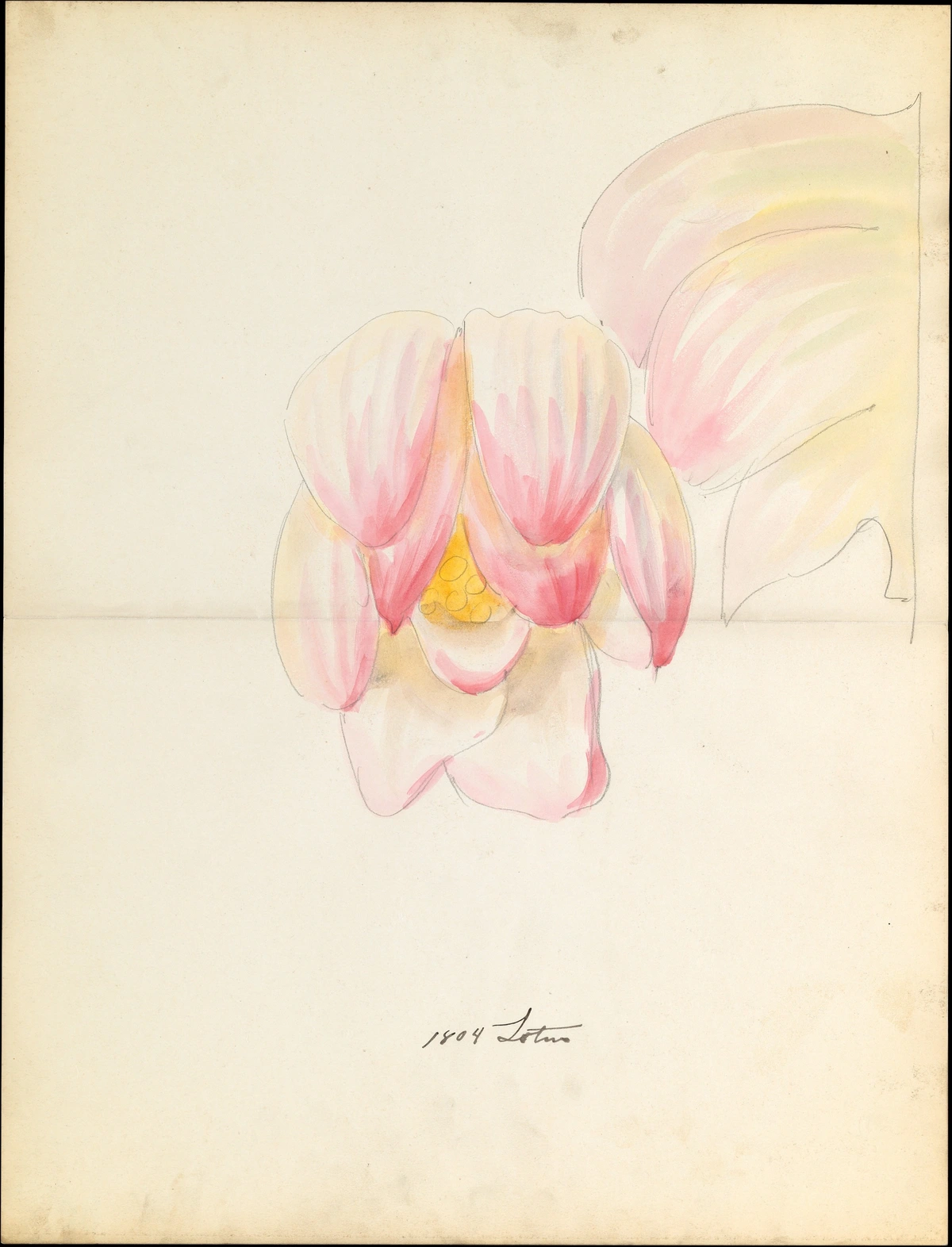

This is a big one that relates directly to the lifting technique we'll discuss later, and it's a characteristic that dramatically impacts your ability to make corrections or create specific effects. Staining pigments (like Phthalo Blue, Alizarin Crimson, or Quinacridone Rose) essentially dye the paper fibers themselves. Once they're down and dry, they're difficult or impossible to completely remove without damaging the paper. They become an intrinsic part of the paper, creating intense, vibrant colors that are hard to disturb, offering incredible permanence and luminosity. On the other hand, non-staining pigments (like Ultramarine Blue, Cadmium Yellow, or Cobalt Blue) sit more on the surface of the paper, making them much easier to lift or remove, even after drying. They're often the ones that granulate beautifully, creating interesting textures, and offer more flexibility for softening edges or pulling out highlights. Knowing this distinction is like having an invisible 'undo' button for some colors, but not others! For instance, if I’m painting a delicate sky and want the option to gently lift clouds or soften a horizon, I’ll often reach for a non-staining pigment like Cobalt Blue. But for a rich, vibrant botanical illustration where I want bold, permanent color, a staining Quinacridone Rose might be my choice. This knowledge becomes a powerful strategic tool in your artistic arsenal, guiding your color choices based on both hue and desired working properties.

Transparency vs. Opacity

While watercolor is famous for its transparency, which is truly its defining characteristic, not all pigments are created equal in this regard. Some pigments are naturally more transparent, allowing light to pass directly through them, bounce off the pristine white paper surface, and reflect back to your eye – this is what creates that signature luminosity and glow. Others are more opaque (like Cadmium colors, Naples Yellow, or certain earth tones), meaning they block more light and create a more solid, covering layer. A slightly opaque pigment can be surprisingly useful for subtle corrections, adding a sense of density, or creating a more solid focal point or highlight that wouldn't typically be achieved with pure transparent washes. However, generally, true transparency is the hallmark and most celebrated quality of watercolor. Understanding this spectrum is crucial. A transparent pigment like Hansa Yellow can create brilliant glazes, allowing previous layers to shine through, while a semi-opaque pigment like Cadmium Yellow (often used for its strong tinting power and vibrancy) will create a more solid, covering layer. Even within transparency, some pigments are more 'dye-like' (strong stainers), while others are more 'particulate' (prone to granulation), offering endless nuanced possibilities.

Permanence and Lightfastness: The Unsung Hero of Archival Art

We touched on lightfastness earlier when discussing pigment quality, but it’s absolutely worth reiterating here, because it's a silent destroyer of artwork if ignored. A paint's permanence refers to its overall ability to resist change over time, encompassing not just fading (which is what lightfastness addresses specifically) but also resistance to humidity, atmospheric pollutants, and chemical reactions with other materials. Always, always choose artist-grade paints with good lightfastness ratings (often indicated by ASTM ratings like I, II, or III, or stars on the paint tube/pan) if you want your artwork to endure for decades, or even centuries. I've heard too many stories of beautiful works fading into ghosts, slowly diminishing into pale echoes of their former selves, and it's always a heartbreak. Imagine pouring your heart into a painting, only for its vibrant hues to gradually disappear – that's the tragedy of non-lightfast pigments. Prioritizing lightfastness is an act of preserving your artistic legacy, ensuring your creations can be enjoyed by future generations. Trust me, few things are more heartbreaking than seeing a cherished piece of art fade into a pale ghost of its former self. Always, always check those ASTM ratings – it's a small step that makes a monumental difference in the life of your art. (You'll find a more detailed table on lightfastness ratings and archival best practices in the 'Care & Preservation' section of this guide, so you can make truly informed and conscientious choices for your masterpieces.)

Dispersion, Flocculation, and Sedimentation

This is a bit more technical, but absolutely fascinating and crucial for understanding how pigments settle on your paper! Dispersion refers to how evenly the pigment particles spread out in the water. Some pigments disperse very smoothly, creating uniform washes, perfect for calm, unblemished skies. Others, however, tend to clump together or flocculate (form tiny aggregates of pigment), especially as they dry, contributing to a more textured, slightly uneven wash. This isn't necessarily a bad thing; in fact, it's often a beautiful characteristic that adds visual interest, particularly with granulating pigments. Think of the subtle, organic textures you see in an old, weathered wall or a misty, distant landscape; flocculation can beautifully replicate these natural surfaces. Closely related is sedimentation, which is when heavier pigment particles literally settle out of the water and collect at the bottom of a wash as it dries, also contributing significantly to granulation and textured effects. Understanding dispersion, flocculation, and sedimentation can help you anticipate precisely how a pigment will behave in a wash and prevent unexpected results – or, more excitingly, harness them for intentional artistic effects! For example, a controlled flocculation can create the varied textures in a distant forest, the dappled light on foliage, or the natural unevenness of an old stone wall, adding immediate character and depth to your scene. Learning to observe how different pigments flocculate and settle can open up a whole new world of textural possibilities, transforming what might seem like a 'defect' into a deliberate and sophisticated artistic choice.

Blooms or Cauliflowers: Embracing or Avoiding Water Marks

Also known as water marks or backruns, these are irregular, often feathery-edged dark patches that appear in a wash when new water or wetter paint is introduced into a drying, but still damp, wash. They happen because the fresh, wetter solution pushes the pigment at the edge of the damp area, causing it to concentrate and bloom outwards. While often seen as a beginner's mistake – and trust me, I've had my share of unintentional cauliflowers that left me pulling my hair out! – experienced artists frequently embrace blooms intentionally for textural effects, like the soft, ethereal edges of clouds, the organic feel of distant foliage, or the rugged texture of rocky landscapes. Learning to control or prevent them, however, is key for achieving smooth, even washes when desired, but don't be afraid to lean into them for intentional texture! I've had more than one happy accident turn into a beautiful cloud formation or a uniquely rugged mountain texture that I could never have planned. Sometimes, the 'mistake' is the invitation to discover a new technique.

If you're asking me, the distinct personality of watercolor stems from a few key properties. These aren't just technical specifications; they're the very characteristics that define the experience of painting with it. Let's delve into what truly makes watercolor, watercolor.

Re-wettability: The Gift of Infinite Workability

One of the most uniquely practical and forgiving characteristics of watercolor, and one that sets it apart from acrylics or oils, is its remarkable re-wettability. This simply means that even after the paint has dried, sometimes for years, you can reactivate it with water. This is thanks to the gum arabic binder, which never becomes truly insoluble. For artists, this is an immense gift. It means you can easily go back to a dried palette and reactivate your colors, minimizing waste. On paper, it allows for various lifting techniques (which we'll explore in the techniques section) and offers a degree of flexibility for adjustments that other mediums simply don't. I've often returned to a dried painting a day later, and with a clean, damp brush, been able to gently soften a hard edge or lift a subtle highlight, almost like magic. This endless capacity for re-activation makes watercolor incredibly forgiving and efficient, allowing for a freedom of practice that is truly liberating. It’s a testament to the medium’s inherent pliability and responsiveness, always ready to dance again with water.

Transparency and Luminosity: Light Through Color

This is the big one, the defining characteristic, the very soul of the medium. Unlike opaque mediums, watercolor is inherently transparent. When you apply a wash, the light passes through the layer of pigment, bounces off the pristine white surface of your paper, and reflects back to your eye, picking up the color on its way out. This unique interplay of pigment, water, and paper is what gives watercolor its incredible luminosity and glowing quality – it’s truly like painting with captured light itself, a truly ethereal experience. It’s why watercolorists often talk about preserving the white of the paper – that untouched white is your ultimate light source, your purest highlight, and once it's gone, it's gone. Think of it like a beautiful stained-glass window: the light shines through it, not just on it, creating a vibrancy and depth that's difficult to replicate with other paints. This transparency also means that underlying pencil lines or even previous layers of paint will subtly show through, adding to the depth and complexity of your work, creating a rich visual history within your painting. Indeed, the adage "preserve your whites" is almost a mantra among watercolorists, a constant reminder that the paper itself is your most brilliant light source, and its untouched purity is irreplaceable once covered. This careful planning around light, rather than painting it on, is a foundational difference and a beautiful challenge that watercolor presents.

Mastering this takes practice, but the luminous, glowing results are truly worth the effort.

The Art of the 'Happy Accident' (Water's Unpredictable Nature)

This is a phrase you'll hear often in watercolor circles: "happy accidents." And truly, they often are! The very nature of watercolor, with its fluid, unpredictable water component, means that sometimes the most beautiful, organic, and captivating effects happen when you surrender a little control and let the medium do its thing. Learning to let go and work with the water, rather than rigidly against it, is perhaps the most profound lesson watercolor teaches. I’ve certainly had moments where a planned wash went wonderfully rogue, only to morph into a stunning cloud formation, a uniquely textured foreground element, or a serendipitous blend of colors that I could never have intentionally engineered. Embrace the way colors bloom and mingle, the unexpected soft edges, or the surprising textures that emerge from the interaction of water and pigment. Sometimes, the 'mistake' is actually the most interesting part, leading you to discover new artistic paths and expanding your creative vocabulary! It’s this joyful surrender to the medium that truly differentiates watercolor from more controlled forms of painting, inviting a fresh sense of discovery with every piece.

Essential Watercolor Supplies: Your Starting Toolkit for the Luminous Journey

Alright, you're hooked, you're ready to dive in! But what do you actually need to get started on this luminous journey? The beauty of watercolor is that you don't necessarily need a huge initial investment, but a few quality basics, thoughtfully chosen, can truly make all the difference in your enjoyment and results. I've been there, staring at a wall of tantalizing supplies, wondering where to even begin and what was truly essential versus merely tempting. Let me guide you through the essentials, helping you build a toolkit that sets you up for success.

Paper: The Foundation of Your Luminous Work

This is, arguably, the most important element after the paint itself – yes, even more so than fancy brushes! Watercolor paper isn't just any paper; it's a specially engineered surface designed to withstand significant amounts of water without buckling, bleeding, or losing its structural integrity. Choosing the right paper will dramatically impact your results, your enjoyment of the process, and your overall sanity. Trust me, cheap, poorly-sized paper is a recipe for immense frustration, warped paintings, and a premature end to your artistic enthusiasm!

- Weight: Measured in pounds (lb) or grams per square meter (gsm). This refers to the thickness and density of the paper. Aim for at least 140 lb (300 gsm) paper for most projects. Lighter papers buckle easily – I remember early on trying to save a buck with lighter paper, only to end up with a wavy, unworkable surface after my first wash, which completely derailed my efforts! For extremely wet techniques or very large washes, 300 lb (640 gsm) paper is an absolute dream, as it rarely buckles at all, even without stretching. It's a more significant investment, but can be incredibly liberating for ambitious pieces. Using watercolor blocks, where the paper is glued on all four sides, also brilliantly prevents buckling, as the paper is held taut while drying. Once your painting is dry, you simply use a palette knife or thin blade to separate the top sheet from the block. The heavier the paper, the less likely it is to warp, providing a smoother, more predictable, and ultimately more enjoyable surface for your delicate washes.

- Composition: The fibers that make up your paper dramatically impact its performance and longevity.

- Cotton (Rag) Paper: The gold standard, often labeled as '100% cotton' or 'rag' paper. This is the top tier. 100% cotton paper is incredibly absorbent, allows for beautiful lifting, retains its strength even when saturated, and is far less prone to buckling. It's an investment, but absolutely worth it for its superior performance, beautiful texture, and archival qualities. The long, strong cotton fibers are what give it this exceptional durability, allowing the paper to handle repeated wetting, lifting, and scrubbing without disintegrating or pilling.

- Wood Pulp Paper (Cellulose): More affordable and readily available, but generally less forgiving. Often labeled as 'student grade' or 'cellulose paper,' it can be quite prone to buckling and may not allow for the same level of subtle lifting or layering that cotton paper offers. While it's great for initial sketches or experiments, its shorter and less robust fibers make it less durable when wet. Wood pulp paper is more prone to pilling or tearing if overworked, and it may absorb paint too quickly, leading to duller colors.

- Blends: Some papers are a blend of cotton and wood pulp, offering a compromise between performance and cost. These can be a good stepping stone between student and artist grade papers, providing a slightly better experience than pure wood pulp without the full investment of 100% cotton.

- Sizing: This refers to chemicals (often gelatin, starch, or synthetic agents) added during manufacturing (internal sizing, mixed into the pulp) or applied to the surface (external sizing). Sizing is critical because it controls the paper's absorbency. Without adequate sizing, watercolor paper would absorb paint like a sponge, leading to dull, flat colors and a complete lack of control, almost like painting on blotting paper. Good sizing allows the paint to sit on the surface for a brief period, maintaining vibrancy and allowing you to manipulate the paint before it soaks in. Too much sizing can make the paper repel water, causing it to bead up and resist your brushstrokes, creating frustratingly uneven results. Conversely, too little sizing, and the paper drinks the paint too quickly, leading to dull colors and a complete loss of control over your washes and blending. It's truly a Goldilocks situation – too much and paint beads frustratingly, too little and it's absorbed too fast – just right is absolutely key for that sweet spot of control and luminosity! Without proper sizing, your beautiful transparent washes would simply disappear into the paper, leaving behind dull, lifeless pigment. It’s the invisible shield that holds the magic on the surface, allowing the water and pigment to dance and mingle before finally settling into their final, luminous embrace.

- Surface pH (Acid-Free): Always, always look for paper labeled acid-free or archival quality. This means the paper has a neutral pH (typically 7 or higher), preventing it from yellowing, becoming brittle, or degrading over time due to acid content. This is absolutely vital if you want your artwork to last for decades, or even centuries, without self-destructing. Using non-acid-free paper is a silent killer of artwork, causing it to slowly deteriorate and lose its vibrancy, often a heartbreaking realization years down the line. It's a non-negotiable for any artwork you want to endure.

- Cotton (Rag) Paper: The gold standard, often labeled as '100% cotton' or 'rag' paper. This is the top tier. 100% cotton paper is incredibly absorbent, allows for beautiful lifting, retains its strength even when saturated, and is far less prone to buckling. It's an investment, but absolutely worth it for its superior performance, beautiful texture, and archival qualities. The long, strong cotton fibers are what give it this exceptional durability, allowing the paper to handle repeated wetting, lifting, and scrubbing without disintegrating or pilling. The natural cellulose in cotton also interacts uniquely with watercolor, promoting luminous washes and vibrant color retention.

- Wood Pulp Paper (Cellulose): More affordable and readily available, but generally less forgiving. Often labeled as 'student grade' or 'cellulose paper,' it can be quite prone to buckling and may not allow for the same level of subtle lifting or layering that cotton paper offers. While it's great for initial sketches or experiments, its shorter and less robust fibers make it less durable when wet. Wood pulp paper is more prone to pilling or tearing if overworked, and it may absorb paint too quickly, leading to duller colors and less predictable blending. The lack of robust sizing in many student-grade wood pulp papers means they can often 'drink' the paint, resulting in less vibrant and less controllable washes.

- Blends: Some papers are a blend of cotton and wood pulp, offering a compromise between performance and cost. These can be a good stepping stone between student and artist grade papers, providing a slightly better experience than pure wood pulp without the full investment of 100% cotton. They aim to balance the archival qualities and workability of cotton with the affordability of wood pulp, often a good choice for serious students or for larger practice pieces where cost is a factor.

- Texture: The surface texture, or 'tooth,' of watercolor paper is another crucial choice, dramatically affecting how your paint behaves and the final look of your piece. Each texture offers unique advantages:

- Hot Press: This paper has a smooth surface, with very little or no 'tooth,' created by pressing it between hot rollers. This makes it fantastic for detailed work, fine lines, precise washes, and smooth gradations. Colors appear very vibrant and intense on hot press paper because there's less texture to diffuse the light. It's perfect for botanical illustration, realistic portraits, crisp graphic styles, ink and wash techniques, or even calligraphy, where sharp lines are desired. For me, hot press is where clarity and crispness reign, allowing for those intricate details that make a piece truly sing. It's also excellent for techniques like dry brush when you want minimal texture and a more 'broken' line, or for adding layers of precise glazes without disturbing underlying textures. However, its smooth surface can sometimes make large, even washes more challenging for beginners, as there’s less tooth for the water to 'grab' onto, potentially leading to streaks if not applied swiftly and confidently.

- Cold Press: This is the most popular and versatile choice for watercolor artists, offering a medium texture. It's created by pressing the paper between cold rollers. It provides a good balance of detail and washes, with enough 'tooth' to allow for some beautiful granulation and absorption, while still offering a relatively smooth surface for brushstrokes. This is my personal go-to for most general painting, offering incredible versatility and forgiving qualities, making it ideal for beginners and experienced artists alike. It's the dependable friend in your artistic toolkit. The texture of cold press paper provides just enough grip for the pigment to settle beautifully, allowing for wonderful granulation and varied wash effects. It's also more forgiving for lifting and corrections compared to hot press, making it a favorite for many artists exploring a range of subjects and styles.

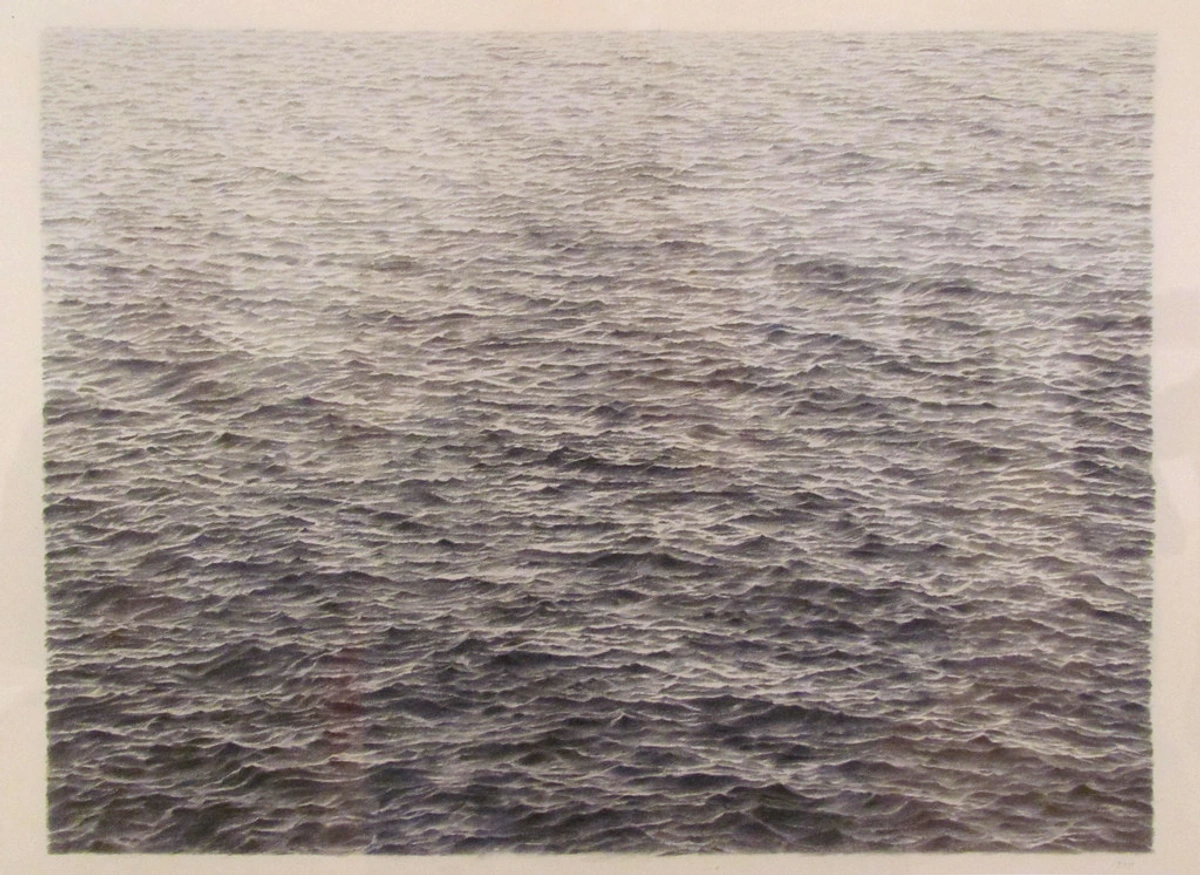

- Rough: As the name implies, this paper has a heavily textured, pronounced tooth. It creates strong granulating effects, allowing pigments to settle beautifully into the valleys of the paper, and highlights the tooth of the paper wonderfully with dry brush techniques. This surface is fantastic for capturing rough textures in landscapes, like craggy rocks, turbulent water, or stormy skies, and for bold, expressive washes where texture is a key element. The deep valleys of the paper often remain white, creating a brilliant, sparkling effect with dry brush techniques, adding an immediate sense of character and depth. When I want that raw, untamed texture, rough paper is my first choice. It demands a confident hand, as delicate details can be lost in its valleys, but for expressive, textural work, it’s simply unmatched. I particularly love how dry brush on rough paper creates a scintillating effect, almost like light sparkling on a textured surface, adding incredible depth and character to a landscape or abstract piece.

Paper Grain: Direction and Impact

Beyond texture, watercolor paper also has a grain, referring to the direction in which the paper fibers are aligned during manufacturing. This isn't usually a critical factor for smaller pieces, but for larger works or when tearing/folding paper, it can be important. Paper tears more cleanly along the grain, and folds are sharper. While not as overtly impactful as texture, understanding grain is part of a holistic appreciation for your paper's properties. Sometimes, the grain can subtly influence how a wash spreads or how the paper reacts to wetness, especially in larger sheets. It's another layer of subtle interaction between you, your materials, and the final artwork, often only noticed by the most seasoned artists, but worth a quiet nod in our comprehensive guide.

Paper Texture | Characteristics | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Hot Press | Smooth, very low tooth, colors appear vibrant, sharp lines | Detailed botanical work, portraits, ink & wash, calligraphy |

| Cold Press | Medium texture, versatile, balanced absorption, good for granulation | General painting, balanced washes, details, beginners, landscapes |

| Rough | Heavy texture, pronounced tooth, encourages granulation, highlights dry brush | Expressive landscapes, rocks, stormy skies, abstract textures |

I always tell beginners, and I can't emphasize this enough: "Don't skimp on paper!" Even student-grade paints look dramatically better and are more enjoyable to work with on good paper. You can find more in-depth advice in our guide to best watercolor paper for artists. Selecting the right paper is truly about empowering your brushstrokes and ensuring your efforts are beautifully preserved. It's the silent partner that absorbs, or resists, your creative intentions, setting the stage for all your watercolor adventures.

Brushes: Extensions of Your Artistic Intent

You don't need dozens of brushes, don't get me wrong, but a few quality ones make an exponential world of difference. A good round brush (size 8 or 10) and a flat wash brush (1/2 inch or 1 inch) will get you surprisingly far, allowing you to explore a vast array of techniques with confidence. I always recommend investing in the best brushes you can reasonably afford, as they are truly an extension of your hand, providing better control, superior water retention, and impressive durability. Taking good care of your brushes, which we'll cover in detail right now, will ensure they last a lifetime and remain trusted companions on your artistic journey.

Brush Care: Making Your Tools Last

Proper brush care is often overlooked, and I know it can feel like a chore sometimes, but it's absolutely crucial for the longevity and optimal performance of your brushes. Think of them as delicate instruments that need a little love! Immediately after painting, rinse your brushes thoroughly in clean water until absolutely no pigment comes off. You can gently swirl them in your 'dirty' water container and then run them under a tap. Crucially, avoid scrubbing them harshly against the bottom of your container or leaving them sitting bristles-down in water, which can permanently bend the hairs and loosen the ferrule (the metal part that connects the bristles to the handle). Once rinsed, gently reshape the bristles with your fingers to their original point or chisel edge – this helps maintain their intended shape. Then, let them dry flat or brush-side down (using a brush holder, if you have one, or just propped carefully) – never resting on their ferrules, which can cause water to seep into the handle and loosen the glue, shortening their lifespan. Crucially, never, ever let paint dry in the bristles, as this can permanently damage them and make them stiff, splayed, and ultimately unusable. A well-cared-for brush can truly last you for years, becoming a trusted and responsive companion in your artistic journey. For more detailed tips, you might enjoy our guide on cleaning and caring for your paint brushes. I've seen countless artists lose their favorite brushes prematurely due to improper cleaning; it's a small investment of time that pays huge dividends in the longevity and performance of your tools. Remember, your brushes are an extension of your creative intention, treat them with the respect they deserve, and they will faithfully serve your artistic vision.

- Natural Hair: Often sable (like Kolinsky sable, considered the gold standard for its exceptional snap, point, and capacity) or squirrel (known for holding truly enormous amounts of water, perfect for large, flowing washes). These brushes typically hold an incredible amount of water and pigment and release it smoothly and evenly. They are generally more expensive but offer a true joy to use for their responsiveness and capacity, especially for traditional watercolor techniques. Kolinsky sable, in particular, is prized for its exceptional snap and ability to hold a fine point, making it ideal for both broad, juicy washes and intricate details. Other natural hairs like squirrel offer incredible water retention, perfect for large, flowing washes with minimal re-loading, while goat hair can provide a unique softness for blending and atmospheric effects. Each natural hair type brings its own subtle magic to the brushstroke, inviting a deeply tactile and responsive painting experience.

- Synthetic Hair: Excellent modern alternatives, often more affordable, durable, and cruelty-free. Advances in synthetic fiber technology mean they mimic natural hair properties remarkably well, offering good spring, control, and pigment release. Many artists, myself included, find synthetics to be incredibly versatile and reliable workhorses, sometimes even preferring them for their consistency and resilience. They're a fantastic choice for any artist, from beginner to professional. Many modern synthetics are specifically engineered to replicate the properties of natural hairs, offering excellent spring, good water capacity, and impressive durability. They are also often more resilient to harsh pigments and repeated scrubbing, making them ideal workhorses for daily practice and robust techniques. I often mix natural and synthetic brushes in my own toolkit, leveraging the strengths of each for different aspects of a painting.

- Blends: A mix of natural and synthetic fibers, designed to combine the best properties of both – often a good compromise between performance, water retention, and cost. They can be fantastic all-rounders, offering some of the benefits of natural hair with the durability and affordability of synthetics. These hybrid brushes often strike a wonderful balance, providing good snap and water retention without the premium price tag or delicate care requirements of pure natural hair, making them a superb option for a versatile and reliable brush collection.

Beyond hair type, brush shape is also key, each designed for specific marks and purposes – choosing the right shape can make a huge difference in achieving your desired effect:

- Round Brush: The most versatile and often a beginner's first brush. Thanks to its pointed tip and broad belly, it's great for everything from fine lines (with the tip) to broader washes (with the belly) and details, all depending on the size and pressure you apply. A good size 8 or 10 round is indispensable for everything from subtle shading to crisp outlines. The sheer versatility of a well-made round brush means it can perform the duties of several other brush shapes, making it a foundational tool for any watercolor artist. I often find myself reaching for my trusted round brush for almost every step of a painting, from initial washes to final delicate details.

- Flat Wash Brush: As the name suggests, this brush is ideal for laying down even washes over large areas, creating crisp, straight edges, or for more geometric shapes. Comes in various widths, like 1/2 inch or 1 inch, perfect for covering ground quickly or for creating strong, angular forms in architectural sketches or bold abstracts. Their sharp, straight edge is also invaluable for lifting color or creating distinct, geometric shapes, offering a different kind of control than a round brush. For expansive skies or calm bodies of water, a large flat wash brush can lay down a seamless, even wash with remarkable efficiency.

- Mop Brush: A large, soft, absorbent brush (often squirrel hair or a high-quality synthetic equivalent) perfect for soaking up excess water, laying down very soft, even washes, or creating soft-edged blooms. They hold a tremendous amount of liquid, making them excellent for large, fluid applications, especially when you want a smooth, ethereal effect. Their incredibly soft bristles are gentle on the paper, making them ideal for delicate blending and avoiding harsh brushstrokes. I often use a mop brush for initial large washes or for absorbing excess water from a wet area, almost like a thirsty cloud, bringing a unique softness to the work.

- Liner/Rigger Brush: These are long, thin brushes with a very fine point, originally designed for painting the rigging on ships (hence 'rigger'). They are perfect for very fine lines, delicate details, signatures, and long, flowing calligraphic strokes (think delicate tree branches, long blades of grass, or intricate patterns). They excel at continuous, unbroken lines. Their long, slender bristles allow for a remarkable amount of paint to be held, enabling you to draw extended, consistent lines without reloading the brush, which is crucial for those intricate details that demand precision and flow. Think of painting the delicate tendrils of a vine or the intricate patterns on a butterfly's wing; a rigger is your perfect companion.

- Fan Brush: This brush has splayed bristles resembling a fan. It can be used for soft blending, creating organic textures like grass, distant foliage, hair, or fur, or for controlled spattering effects. It's a specialist brush, but wonderfully expressive for organic, feathery marks, adding a touch of natural spontaneity. I’ve found it invaluable for creating the texture of distant foliage, soft grass, or even the gentle ripples on water, offering a unique mark-making capability that’s hard to replicate with other brushes. It’s a tool that encourages a looser, more impressionistic approach, inviting you to play with texture and suggestion.

For more on choosing the right tools, check out our essential watercolor supplies for beginners article. And don't forget, the quality of your paper, brushes, and paints all work in concert to influence your final outcome – they're a team, and the weakest link can sometimes affect the whole. Choose wisely, care for them well, and they'll serve your artistic vision beautifully.

Palettes: Your Color Mixing Sanctuary

Anything non-porous and white (or a very neutral light gray) works as a palette! Seriously, I've used everything from a fancy ceramic palette to the lid of a takeout container in a pinch (don't judge, inspiration strikes, right?). Ceramic or porcelain palettes are often preferred for their satisfying weight, smooth non-staining surface, and how beautifully colors appear true to their hue and are easy to re-wet. Plastic palettes are lightweight and portable, though some can stain over time and may cause water to bead up slightly. Metal palettes (often found in pan sets) are also common and can be very durable, but check for rust resistance to avoid unwanted discoloration. The key is that the surface is non-absorbent, allowing your pigments to remain vibrant and easily accessible for dilution and mixing without them soaking in or altering their appearance. A white background helps you accurately see the true hue and value of your mixed colors, which is vital for precise color choices. Cleaning your palette regularly is also key to preventing muddy mixes, and covering your palette when not in use can prevent dust or pet hair from settling into your precious paints, keeping your colors fresh and vibrant. For me, a clean palette is a clear mind, and it ensures the purity of my abstract color mixes, preventing any unintended dullness. Different palette materials, from smooth porcelain to practical plastic, offer varied experiences. Porcelain provides a beautifully non-staining surface that makes colors appear true to hue, while plastic palettes are lightweight and durable for travel. Regardless of material, the key is a non-porous surface, allowing your pigments to remain vibrant and easily accessible for dilution and mixing without them soaking in or altering their appearance. Regular cleaning isn't just about aesthetics; it's about preserving the integrity of your colors and preventing unwanted muddying in your next masterpiece. And a little trick I've learned: covering your palette when not in use can prevent dust or pet hair from settling into your precious paints, keeping your colors fresh and vibrant for your next session!

Water Containers: Two is Better Than One

This simple tip is a complete game-changer, and it's one of the first things I share with anyone starting out! Always, always keep two containers of water: one for rinsing off most of the paint from your brush (your designated 'dirty' water), and one for clean water to dilute your colors or create fresh washes (your designated 'clean' water). This crucial distinction prevents your pristine mixes from inadvertently turning muddy and ensures your colors remain vibrant and true. You'd be amazed how quickly that single clean water container becomes a murky soup if you don't maintain this separation, and muddy colors are, as we'll discuss, the arch nemesis of any watercolorist! Any jar or cup will do, but I often opt for wider containers that allow for easy rinsing without banging the brush against the sides, and a heavier base can prevent accidental tipping. It’s a small habit, but it reaps huge rewards in clarity and color purity. Trust me, I've learned this the hard way more times than I care to admit, ending up with unintended muted tones when I was aiming for brilliance! The distinction between your 'dirty' rinse water and your 'clean' diluting water is a small habit that yields monumental results in the clarity and vibrancy of your colors. A wide-mouthed container also makes rinsing much easier, preventing you from banging your brush bristles against the sides and preserving their delicate shape. It's a simple organizational tweak that will dramatically elevate your painting experience and the purity of your hues.

Other Essential Watercolor Supplies: The Supporting Cast

Artist Tape / Gummed Paper Tape: The Buckle Buster

While we've discussed stretching paper to prevent buckling, artist tape or gummed paper tape is the unsung hero that facilitates this process. Artist tape (sometimes called painter's tape, but ensure it's low-tack and specifically designed for art) is excellent for temporarily securing paper to a board for smaller works or for creating crisp, clean borders around your painting. Gummed paper tape, however, is the traditional and most effective method for stretching paper. It's water-activated, incredibly strong, and creates a drum-tight surface once dry, completely eliminating buckling, even with heavy washes. I always keep a roll of good quality gummed tape in my studio; it's an indispensable tool for ensuring a perfectly flat working surface, especially when I'm tackling larger pieces or intense wet-on-wet techniques. It's the silent engineer behind many a perfectly flat watercolor. Remember to choose archival quality tapes to ensure they won't damage your paper over time.

While paint, paper, brushes, and water are the undeniable stars of the show, and rightly so, a few other items can significantly enhance your watercolor experience, make your life easier, and expand your creative possibilities. Think of them as the unsung heroes and loyal supporting cast members of your studio – they might not always be in the spotlight, but they're indispensable!

Masking Fluid (Liquid Frisket): The White Preserver

This is a brilliant liquid latex-based product that you apply to areas you want to keep pristine white (or any underlying color) and completely free of paint. Once it's dry, you paint over it with your watercolor washes, and after your paint is completely dry, you gently rub or peel off the masking fluid to reveal the untouched area beneath. It’s invaluable for preserving delicate highlights, creating sharp edges for complex shapes, or protecting intricate areas you simply don't want paint to touch. I always keep a dedicated, old brush or a silicone shapers just for masking fluid, because it can be tough on bristles and dries incredibly quickly! You can also use a fine-tipped applicator, a ruling pen, or even a toothpick for very precise lines. A rubber cement pickup or even a clean finger can be used to gently remove dried masking fluid without damaging the paper. Remember to remove masking fluid only when the paint is completely dry to avoid tearing the paper or lifting unintended areas of pigment – patience is key here, too! For me, masking fluid is an absolute game-changer for preserving those crisp, intentional moments of white in my abstract compositions, allowing the surrounding colors to truly sing. It's a tool that requires a bit of practice to master its application and removal, but the results — sharp, untainted whites amidst flowing color — are truly worth the effort. Always remember to use an old brush or a silicone tool, as it can be incredibly tough on delicate bristles, and clean your applicator immediately after use to prevent drying and damage. This small precaution will save you many brushes in the long run!

Sponges: Organic Textures and Soft Edges

Natural sea sponges or synthetic sponges can be surprisingly fantastic for creating organic textures (like dappled foliage, rough stone, or misty effects), softening edges, or even lifting large areas of paint for clouds, highlights, or corrections. Experiment with different levels of dampness and pressure to see the incredible variety of marks you can make – they're surprisingly versatile! A small, damp natural sponge can be a revelation for creating natural cloud forms, misty atmospheric effects, or even the texture of distant trees. Each sponge has a unique porosity and texture, so it's absolutely worth experimenting to find your favorites and discover their unique mark-making capabilities. I've found them indispensable for adding an organic, almost accidental texture that mimics natural forms. A natural sea sponge, with its irregular pores, can create beautifully random textures, perfect for dappled light through trees or the rough surface of rocks. Synthetic sponges, on the other hand, can offer more uniform patterns or be cut into specific shapes for unique marks. Experimenting with dry, damp, and wet sponges, and varying the pressure, will unlock a surprisingly vast array of textural possibilities, transforming what might seem like a simple tool into a versatile texturizing agent.

Paper Towels/Rags: Your Silent Assistants

Absolutely, unequivocally essential! Never underestimate the power of a clean, absorbent paper towel or a dedicated cotton rag – they are your unsung best friends for control, blotting excess water from your brush, cleaning up drips, correcting small mistakes by lifting, or even creating soft, subtle textures. I literally always have a roll nearby, as they're indispensable for maintaining clean work, precise control over your water, and immediate troubleshooting. Beyond blotting excess water from your brush or lifting stray drops, a gently twisted corner of a paper towel can be used to lift small highlights from a damp wash, creating delicate cloud forms or sparkling reflections. It’s an incredibly versatile and often underappreciated tool that offers both control and correctional power. They're like the ever-present, ready-to-help assistant in my studio, always there to prevent a disaster or refine a delicate wash.

Pencils and Erasers: The Light Touch of Planning

For light preliminary sketches that will guide your painting without dominating it. Use a hard lead pencil (like a 2H or H, or even a mechanical pencil with a light lead) so the lines are faint and won't show through your transparent washes. You want lines that suggest, not dominate your delicate watercolors. A kneaded eraser (that pliable, putty-like eraser) is perfect for gently lifting pencil marks without damaging the paper's surface, as it "lifts" graphite rather than rubbing and potentially abrading. A firmer rubber eraser can be used carefully on dry paint for stronger lifts, but always test it first on a scrap piece to avoid abrading the paper. An eraser shield can also be handy for protecting surrounding areas while erasing, ensuring you only remove what you intend to. The fainter and lighter your initial sketch, the more seamlessly it will integrate into your luminous watercolor, disappearing into the finished piece. My own process often begins with the lightest whisper of a pencil line, just enough to guide the flow. For me, the sketch is a silent conversation with the paper, a preliminary dance before the pigment arrives. I prefer a very light touch, almost invisible, ensuring the transparency of the watercolor isn't compromised by dark graphite lines. A kneaded eraser is a watercolorist's best friend for gently lifting excess pencil marks without disturbing the paper's surface, preserving its integrity for the washes to come.

Drawing Board/Support: The Stable Foundation

While not explicitly a 'supply' for the paint itself, a rigid drawing board (like Masonite, Gatorboard, or even a thick piece of plywood) is absolutely invaluable for several reasons. You can tape your paper to it to prevent buckling (especially lighter papers), or simply have a stable, portable surface to work on, whether at your desk or en plein air. Many boards also come with clips or can be propped up. Having a slight incline on your board (even just propping up one end with a block or book) can significantly aid in smooth wash application, letting gravity gently pull the wash downwards and preventing unwanted puddles or hard edges. It's a simple trick that can make a huge difference, especially for those challenging graded washes! Drawing boards can be made of various materials, including wood, Masonite, Gatorboard, or even acrylic, each offering different levels of portability and durability to suit your needs. I rarely paint without a slight incline, it feels like I'm collaborating with gravity itself! The stable surface of a drawing board is also crucial for preventing warping if you're not stretching your paper, or for simply providing a firm foundation for your artistic gestures. Whether you're working at a desk or en plein air, a reliable support makes all the difference in the comfort and control of your painting experience.

Spray Bottle: The Moisture Controller

A small, fine-mist spray bottle is incredibly useful for a surprising number of tasks. It's fantastic for re-wetting dried paints on your palette, preventing them from completely drying out during a painting session. You can also gently mist your paper to keep washes damp for longer periods, which can be invaluable for large, complex wet-on-wet techniques, giving you more working time. It's also great for creating interesting wet-on-wet effects directly on your paper, or for subtly softening hard edges after a wash has dried, giving you more flexibility and control over your washes and blends. Just make sure it's a fine mist, not a jet! I've used a spray bottle to create a dreamy, misty atmosphere in a landscape, almost like painting with fog. Beyond re-wetting paints and extending working time, a fine mist can also be used to pre-dampen paper for smoother washes, or even to create subtle textural effects by encouraging pigment movement on a partially dry wash. It’s a deceptively simple tool that offers a surprising amount of control over moisture and atmospheric effects.

Fixative: The Finishing Shield

While not always necessary if your work will be framed under glass (which provides its own protection), a light spray of archival fixative can be a useful extra layer of protection. It shields finished watercolors from dust and minor smudges, especially if they won't be framed immediately or if you're layering other dry media (like pastel or colored pencil) on top. Ensure it's a specialized watercolor or pastel fixative (often called a 'workable fixative') that is designed to be clear and won't react with the delicate paint layers or alter their transparency. Always test on a scrap piece first to check for any unwanted changes to color or sheen! There are also different finishes, from matte to satin, so choose one that complements your artwork without dulling its inherent luminosity. For pieces that might be handled before framing, a light fixative offers invaluable peace of mind. While not a substitute for proper archival framing under glass, a good quality fixative can provide an interim layer of protection against minor abrasions, dust, and smudging, especially if you're transporting or exhibiting your work unframed. Always ensure it's a 'workable' fixative if you plan to layer other dry media on top, as this allows for further modifications without reacting with the watercolor.

- Masking Fluid (Liquid Frisket): This is a brilliant liquid latex-based product that you apply to areas you want to keep pristine white (or any underlying color) and completely free of paint. Once it's dry, you paint over it with your watercolor washes, and after your paint is completely dry, you gently rub or peel off the masking fluid to reveal the untouched area beneath. It’s invaluable for preserving delicate highlights, creating sharp edges for complex shapes, or protecting intricate areas you simply don't want paint to touch. I always keep a dedicated, old brush or a silicone shapers just for masking fluid, because it can be tough on bristles and dries incredibly quickly! You can also use a fine-tipped applicator, a ruling pen, or even a toothpick for very precise lines. A rubber cement pickup or even a clean finger can be used to gently remove dried masking fluid without damaging the paper. Remember to remove masking fluid only when the paint is completely dry to avoid tearing the paper or lifting unintended areas of pigment – patience is key here, too!

- Sponges: Natural sea sponges or synthetic sponges can be surprisingly fantastic for creating organic textures (like dappled foliage, rough stone, or misty effects), softening edges, or even lifting large areas of paint for clouds, highlights, or corrections. Experiment with different levels of dampness and pressure to see the incredible variety of marks you can make – they're surprisingly versatile! A small, damp natural sponge can be a revelation for creating natural cloud forms, misty atmospheric effects, or even the texture of distant trees. Each sponge has a unique porosity and texture, so it's absolutely worth experimenting to find your favorites and discover their unique mark-making capabilities.

- Paper Towels/Rags: Absolutely, unequivocally essential! Never underestimate the power of a clean, absorbent paper towel or a dedicated cotton rag – they are your unsung best friends for control, blotting excess water from your brush, cleaning up drips, correcting small mistakes by lifting, or even creating soft, subtle textures. I literally always have a roll nearby, as they're indispensable for maintaining clean work, precise control over your water, and immediate troubleshooting.

- Pencils and Erasers: For light preliminary sketches that will guide your painting without dominating it. Use a hard lead pencil (like a 2H or H, or even a mechanical pencil with a light lead) so the lines are faint and won't show through your transparent washes. You want lines that suggest, not dominate your delicate watercolors. A kneaded eraser (that pliable, putty-like eraser) is perfect for gently lifting pencil marks without damaging the paper's surface, as it "lifts" graphite rather than rubbing and potentially abrading. A firmer rubber eraser can be used carefully on dry paint for stronger lifts, but always test it first on a scrap piece to avoid abrading the paper. An eraser shield can also be handy for protecting surrounding areas while erasing, ensuring you only remove what you intend to. The fainter and lighter your initial sketch, the more seamlessly it will integrate into your luminous watercolor, disappearing into the finished piece.

- Drawing Board/Support: While not explicitly a 'supply' for the paint itself, a rigid drawing board (like Masonite, Gatorboard, or even a thick piece of plywood) is absolutely invaluable for several reasons. You can tape your paper to it to prevent buckling (especially lighter papers), or simply have a stable, portable surface to work on, whether at your desk or en plein air. Many boards also come with clips or can be propped up. Having a slight incline on your board (even just propping up one end with a block or book) can significantly aid in smooth wash application, letting gravity gently pull the wash downwards and preventing unwanted puddles or hard edges. It's a simple trick that can make a huge difference, especially for those challenging graded washes! Drawing boards can be made of various materials, including wood, Masonite, Gatorboard, or even acrylic, each offering different levels of portability and durability to suit your needs.

- Spray Bottle: A small, fine-mist spray bottle is incredibly useful for a surprising number of tasks. It's fantastic for re-wetting dried paints on your palette, preventing them from completely drying out during a painting session. You can also gently mist your paper to keep washes damp for longer periods, which can be invaluable for large, complex wet-on-wet techniques, giving you more working time. It's also great for creating interesting wet-on-wet effects directly on your paper, or for subtly softening hard edges after a wash has dried, giving you more flexibility and control over your washes and blends. Just make sure it's a fine mist, not a jet!

- Fixative: While not always necessary if your work will be framed under glass (which provides its own protection), a light spray of archival fixative can be a useful extra layer of protection. It shields finished watercolors from dust and minor smudges, especially if they won't be framed immediately or if you're layering other dry media (like pastel or colored pencil) on top. Ensure it's a specialized watercolor or pastel fixative (often called a 'workable fixative') that is designed to be clear and won't react with the delicate paint layers or alter their transparency. Always test on a scrap piece first to check for any unwanted changes to color or sheen! There are also different finishes, from matte to satin, so choose one that complements your artwork without dulling its inherent luminosity.

Basic Watercolor Techniques: Your Artistic Building Blocks

Once you have your essential supplies gathered, it's truly time to play! These fundamental techniques are your artistic building blocks, the vocabulary of watercolor. Mastering them will unlock a world of possibilities and allow you to translate your vision onto paper. And honestly, the best way to learn is just to do – grab your brush, get some water, and start experimenting!

Loading Your Brush: The First Stroke of Control

Before we dive into techniques, let's talk about loading your brush – a seemingly simple step that is absolutely fundamental to successful watercolor painting. It's the art of picking up just the right amount of water and pigment from your palette. Too little, and your brush will be dry and streaky; too much, and your wash will be weak and uncontrollable. The goal is to achieve a juicy, consistent mixture that your brush can hold generously, ready to release its luminous color onto the paper. Practice swirling your brush in your paint mixture until the bristles are fully saturated and come to a beautiful point (for a round brush) or a clean chisel edge (for a flat brush). The ideal consistency often resembles warm tea or milk for lighter washes, and rich cream for more concentrated color. This initial act of loading your brush with intention and precision sets the stage for every stroke that follows, directly influencing the vibrancy, flow, and success of your washes. I often spend a moment just observing the loaded brush, feeling the weight of the water and pigment, anticipating its release – it’s a moment of quiet preparation that makes all the difference.

Washes: The Heartbeat of Watercolor

A wash is a layer of diluted color applied evenly over an area. Mastering washes is absolutely fundamental to watercolor, as they form the backbone of many paintings, establishing atmosphere, setting the mood, and laying down large fields of color. It’s all about controlling the water-to-pigment ratio and cleverly working with gravity and the wetness of your paper. Think of washes as the very canvas of your watercolor painting, setting the mood and initial tones before you even begin to add details – they are the atmosphere, the light, the very foundation upon which everything else is built.