What is Plein Air Painting? An Artist's Personal Guide to Painting Outdoors

An artist's personal guide to plein air painting, covering its definition, history, benefits, challenges, mediums, and how to get started.

What is Plein Air Painting? An Artist's Personal Guide to Painting Outdoors

Ah, plein air painting. Just saying the words conjures up images, doesn't it? Think sun-drenched fields, rugged coastlines, bustling city squares, all captured right there, in the moment, by an artist with an easel and a dream. It sounds incredibly romantic, doesn't it? And often, it truly is. But like anything worth doing, it comes with its own unique set of joys and... well, let's just say 'character-building opportunities'. I remember my first time trying it, perched precariously on a rocky outcrop, convinced I was channeling Monet, only to be humbled by a sudden gust of wind that sent my canvas tumbling. Ah, the romance!

For me, the idea of painting outdoors has always held a certain allure. It's the direct connection to the subject, the challenge of capturing fleeting light, the sheer experience of being immersed in the environment you're trying to depict. It's a far cry from the controlled environment of my studio, where the light is constant (mostly!) and the only wildlife is the occasional dust bunny. It's also a practice that fundamentally changes how you see the world and approach painting, even when you're back inside.

In this guide, I want to share my personal journey with plein air – what it is, why I (and countless others) are drawn to it despite the inevitable chaos, and how you can get started yourself, armed with practical tips and a healthy dose of realism about the 'character-building opportunities' you'll encounter. So, what exactly is plein air painting? Let's dive in.

What Exactly is Plein Air?

At its heart, plein air (pronounced 'plen air') is simply a French term meaning "outdoors". So, plein air painting is the act of leaving your studio behind and painting in situ (in its original place), directly from life, in the open air. It's about capturing the scene as you see it, with all its complexities, light, and atmosphere. Think of it like this: painting from a photograph is like writing a letter based on a description someone gave you; painting plein air is like writing that letter while standing right there in the scene, feeling the breeze and smelling the flowers (or the exhaust fumes!).

While the practice of sketching or making studies outdoors has existed for centuries – think of artists like John Constable capturing the English countryside or the Impressionists painters working directly in the forest of Fontainebleau – the idea of completing a finished painting entirely outdoors really gained traction with the Impressionists in the 19th century. Before them, artists often made sketches outdoors but did the actual painting back in the studio. Why? Partly due to the limitations of materials – paint had to be ground and mixed fresh, and portable easels weren't common. Their artistic goals also often focused on creating polished, finished works in the controlled environment of the studio. The development of portable easels and pre-packaged paint tubes made it much more practical to complete works outside. The Impressionists, however, were obsessed with capturing the effects of light and color at a specific moment in time, and they quickly realized the only way to truly do this was to be there. Think of Monet's haystacks or his water lilies – painted repeatedly at different times of day to show how the light changed everything.

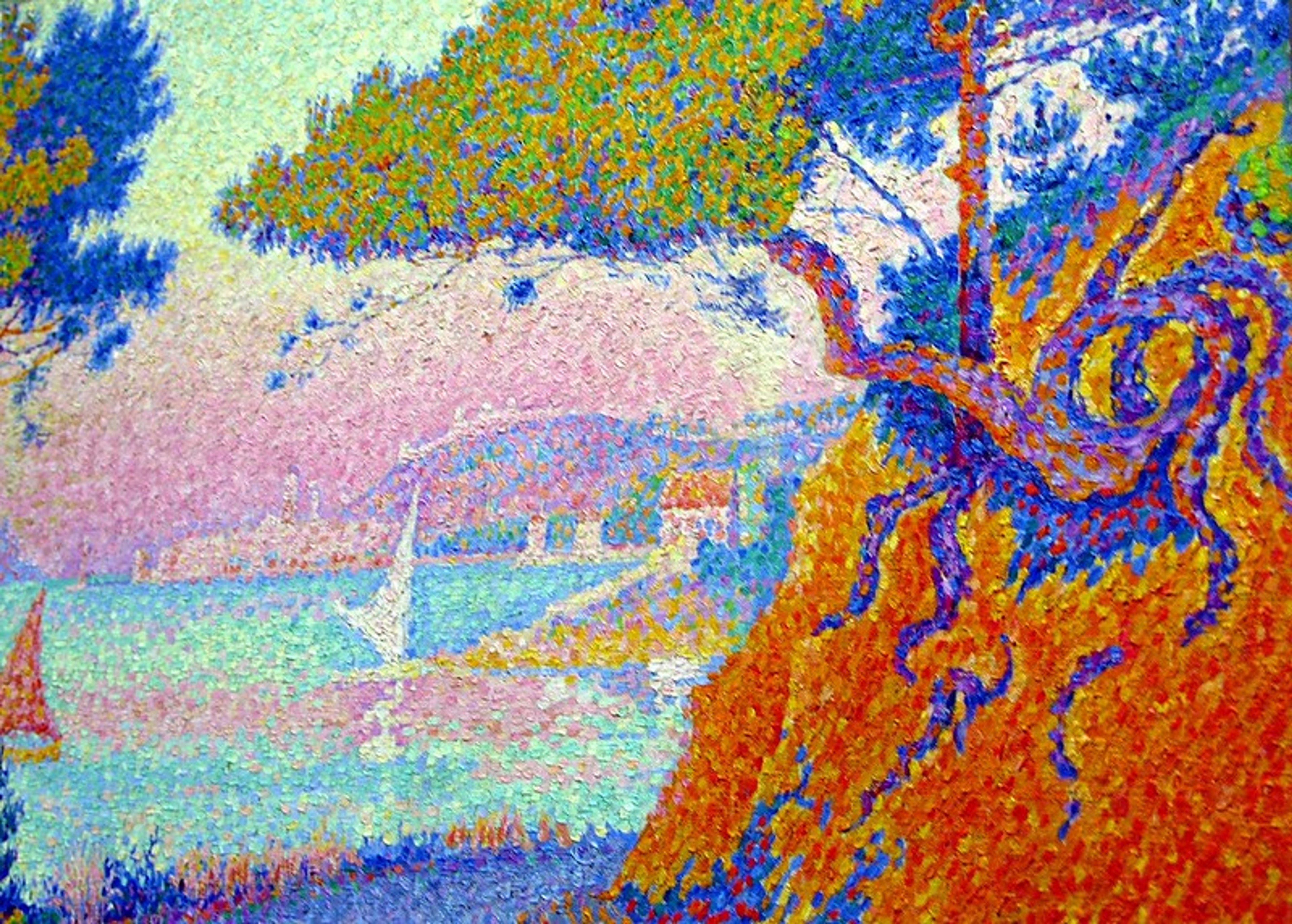

![]()

It wasn't just the Impressionists, though. Many artists throughout history have worked outdoors, but the Impressionists really championed it as a core practice, influencing countless art styles and artists that followed. Artists like John Singer Sargent, known for his dazzling portraits and watercolors, often worked outdoors, capturing figures and landscapes with a fresh, direct approach. Winslow Homer, particularly in his later works, masterfully captured the power and light of the sea in his watercolors, often painted en plein air. This tradition continues today with countless contemporary landscape painters.

Why Paint Outdoors? The Magic and the Madness

So, why put yourself through all that? Why would anyone willingly subject themselves to the whims of nature, the scrutiny of strangers, and the existential dread of a rapidly changing scene? Ah, that's where the magic lies! For me, the biggest draw is the light. Studio light is controlled, predictable. Outdoor light is alive! It shifts, it changes color temperature, it casts incredible dynamic shadows, and it reveals nuances you just can't get from a photograph or memory. A camera flattens the scene; your eyes, immersed in the environment, perceive depth, subtle color shifts, and the feeling of the light in a way technology can't replicate. I remember one afternoon, painting a simple field, when the sun suddenly broke through the clouds after a shower. The way the light hit the wet grass wasn't just brighter; it was a completely different kind of green, vibrating with intensity I'd never noticed before. That's the magic.

Beyond the visual, there's the full sensory immersion. The smell of damp earth after rain, the sound of wind rustling leaves, the warmth of the sun on your back, the chill of a sudden breeze – these aren't things you get in a studio. They feed into your perception of the scene and can subtly (or not so subtly) influence your color choices and brushwork. It's about capturing the feeling of being there, not just the appearance. I recall painting near a bakery once; the faint smell of fresh bread somehow made me choose warmer yellows for the sunlit wall. It sounds odd, but those sensory inputs become part of the experience you're trying to translate.

Here are some of the key benefits I've found:

- Capturing the Moment: There's an immediacy to plein air. You're trying to capture a specific moment, a specific feeling of the place. It forces you to work quickly, make decisions, and trust your instincts. It's exhilarating and terrifying all at once.

- Atmosphere and Color: Being immersed in the environment allows you to truly feel the atmosphere – the temperature, the sounds, the smells. This translates into a richer understanding of the colors and how they interact in that specific light. You see subtle shifts in hue and value that a camera often flattens out. (Speaking of color, you might like my guide on The Secret Language of Color).

- Connection to Nature (or City Life): Whether you're painting a serene landscape or a bustling street, you become part of the scene. You observe details you'd never notice otherwise. It's a form of active meditation, a deep engagement with the world around you.

- Improved Observation Skills: Because the light and conditions are constantly changing, plein air forces you to become a much sharper observer. You learn to quickly identify the most important elements and capture their essence before they change.

- Benefits for Studio Work: The skills honed outdoors – speed, decisive brushwork, keen observation of light and value, simplifying complex scenes – directly translate and improve your studio practice, even if you work in abstract styles. You learn to see value patterns and color relationships more accurately, which is invaluable regardless of subject matter.

The Character-Building Opportunities (aka Challenges)

Okay, let's be real. Plein air isn't always a sun-drenched picnic. There are challenges that can test your patience and resolve. But facing them head-on is part of the adventure, right?

- The Weather: Wind is the enemy of easels. Rain is the enemy of... well, everything. Sun can cause glare and dry your paints too fast. You learn to check the forecast religiously and embrace imperfection. I once spent an hour setting up on a beautiful day, only for a rogue cloudburst to send me packing within five minutes, leaving me with a soggy canvas and a bruised ego. Or the time a sudden gust flipped my easel, sending my palette flying like a colorful, greasy frisbee. Good times.

- Changing Light: That beautiful shadow you started painting? Five minutes later, it's moved. This is the core challenge and the core lesson – learn to capture the essence of the light quickly, or focus on a shorter session (typically 1-3 hours). It teaches you to make bold decisions and not get bogged down in tiny details. You have to be decisive, almost ruthless, about what information you capture before the scene transforms. This is where a quick value study or thumbnail sketch before you start painting is invaluable. A value study is a simple sketch focusing only on the different levels of light and dark in the scene, ignoring color. It helps you lock down the main light and shadow patterns before they shift, giving you a roadmap for the painting. Remember, values (how light or dark something is) are often more stable than the specific colors as the light changes.

- Bugs and Critters: Mosquitoes, flies, spiders, birds who think your paint is food... they all want a piece of the action. Bug spray becomes your best friend. I've had more than one painting feature an unintended fly footprint. And don't even get me started on the ants who seem determined to climb your easel legs. My most memorable encounter involved a persistent bee who seemed convinced my cadmium yellow was a giant flower. It was a tense standoff.

- Curious Onlookers: Most people are lovely and just want to see what you're doing. Some can be... less lovely, or just distracting. You develop a thick skin or learn to find more secluded spots. Learning to politely engage or gently signal you need to focus is part of the process. I've had people stand so close they almost leaned on my easel, or offer unsolicited critiques that were... let's just say 'creative'. It's a performance art piece you didn't sign up for. The most awkward? Someone asking if I was painting their house, which was clearly not in the scene.

- Hauling Gear: Easels, paints, brushes, palette, canvas, water, rags, umbrella, bug spray, snacks, water bottle... it adds up! Packing light is an art form in itself. Trying to navigate a rocky path with a backpack full of wet canvases and a tripod easel is a workout and a half. You learn to appreciate every ounce. My back still remembers that hike up a hill with a full oil setup. And don't forget the walk back with wet paintings!

- Lack of Amenities: When nature calls, nature really calls. Finding a restroom can be a major logistical challenge, especially in remote locations. Access to water for cleaning or drinking can also be limited. And sometimes, just finding a flat, stable, comfortable spot to set up feels like winning the lottery. I've definitely had moments of mild panic realizing I was miles from the nearest public facility.

- The Mental Game: Working outdoors, against the clock of changing light and the elements, can be mentally taxing. You have to be adaptable, resilient, and willing to accept that not every piece will be a masterpiece. It's about the process and the learning, not just the finished product. It's a constant negotiation between your artistic vision and the reality of the environment. There's also the pressure of feeling like you should be producing something amazing because you're out there, which you have to learn to let go of.

Despite these hurdles, overcoming them makes the successful moments even sweeter. There's a real sense of accomplishment when you manage to capture something beautiful despite the elements.

Beyond the Landscape: Other Plein Air Subjects

While landscapes are the most common subject, plein air isn't limited to fields and trees. The core principle is simply painting outdoors, directly from observation. This opens up a world of possibilities beyond the traditional vista. So, what scene calls to you when you step outside? Maybe it's the buzz of the city, the endless horizon of the sea, or even just a quiet corner of your own space.

- Urban Sketching: Capture the energy of city streets, buildings, and people. Think bustling cafes, architectural details, or quiet park benches. The challenge here is often the speed of movement and the sheer volume of visual information. You learn to quickly capture gestures and essential forms. Finding a safe, unobtrusive spot is key. I remember trying urban sketching for the first time in a busy market square – it was exhilarating chaos, forcing me to simplify everything down to quick lines and color notes.

- Marine Painting: The ever-changing sea, boats, harbors, and coastlines offer unique challenges and rewards. Capturing the movement and transparency of water, the reflections, and the specific light over the ocean requires quick observation and confident brushwork. Be prepared for wind and salt spray! Painting by the sea has a completely different feel than painting a field; the light bounces differently, the sounds are constant, and the air itself feels different.

- Figures and Portraits: Painting people outdoors, capturing them in natural light and their environment. This can be tricky as people move, but capturing a figure interacting with their surroundings in natural light can be incredibly compelling. Finding willing models or capturing candid moments quickly is the main hurdle.

- Still Life: Even a simple arrangement of objects can be painted outdoors, allowing you to study how natural light interacts with forms and textures in a controlled setting, but with the added complexity of changing light and potential weather. Keeping your setup stable and protected from wind is crucial.

- Interiors with Natural Light: Plein air doesn't have to mean being fully outdoors. Painting indoors while observing a scene illuminated by natural light (through a window, for example) is also a form of plein air. It offers a more controlled environment but still presents the challenge of changing light as the sun moves. Finding a location with good natural light and permission to set up is the first step.

Each subject brings its own set of considerations, from the speed of movement in urban scenes to the reflections on water, but the core principle of direct observation remains.

Choosing Your Medium for Plein Air

The best paint for plein air really depends on your personal preference, your goals for the session, and the conditions you'll be working in. Each medium has its own unique characteristics when used outdoors. I've experimented with most of these, sometimes with hilarious results (like trying to keep acrylics wet on a scorching hot, windy day!).

Medium | Pros | Cons | Typical Outdoor Drying Time | Portability | Specific Gear Considerations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oils | Slow drying (great for blending), rich color, traditional feel | Requires solvents (or water-mixable oils), longer cleanup, requires wet transport solutions (carriers/boxes to prevent smudging) | Hours to Days | Medium | Wet panel carrier, solvent container, potentially odorless mineral spirits | Longer sessions, detailed work, capturing subtle light shifts |

| Acrylics | Fast drying (good for layering/quick studies), water cleanup, durable | Dries very quickly in heat/wind (can be frustrating), prone to 'color shift' (dries darker than it appears wet) | Minutes to Hours | High | Stay-wet palette, spray bottle for water | Quick studies, layering, portability, working on multiple pieces |

| Watercolors | Highly portable, fast drying, minimal gear, beautiful transparency | Difficult to correct mistakes, requires specific paper, can be challenging in wind/rain | Minutes | Very High | Water container, absorbent paper towels, specific watercolor paper block or pad | Sketches, light studies, travel, capturing atmospheric effects |

| Pastels | Immediate vibrant color, no drying time, highly portable | Messy (requires careful handling), fragile (requires fixative/framing), can be affected by humidity | N/A (no drying) | High | Fixative spray, rigid support, way to protect finished work (glassine paper) | Quick sketches, vibrant color studies, capturing texture and light effects |

| Gouache | Opaque (can layer light over dark), water-based cleanup, portable, dries quickly (but can be re-wet) | Can dry with a 'chalky' finish, colors can lighten slightly when drying, requires specific paper/surface, can be reactivated by rain | Minutes | Very High | Water container, absorbent paper towels, suitable paper or board | Urban sketching, quick studies, portability, opaque effects with water ease |

For beginners, watercolors, gouache, or a small acrylic set can be less intimidating due to easier cleanup and portability. Oils offer a different experience, allowing more time to blend and refine, but require more gear and careful handling of solvents (even odorless ones). Ultimately, the best way to find your preferred medium for plein air is to experiment! Don't be afraid to try something new, even if it means a few frustrating attempts before you find your rhythm.

Getting Started with Plein Air: Practical Tips from the Field

Thinking of giving it a try? Don't let the challenges scare you off! You don't need fancy gear to start. Grab a small sketchbook, some pencils or watercolors, and head to your local park or even your backyard. The key is to just do it. Don't wait for the perfect setup or the perfect day – they rarely happen. Just pack a few essentials and go. What's the worst that can happen? You get a funny story out of it!

Essential Gear Checklist (Start Simple!)

So, what do you actually need to haul out there? Here's a basic list of what I've found helpful over the years, but remember you can adapt this based on your medium and budget:

- Portable Easel: You need something to hold your surface. A lightweight tripod easel is a popular choice because it's easy to carry. Pochade boxes are great compact options that hold your palette and panels, perfect for smaller studies. French easels are sturdier but heavier – maybe for when you're not hiking far! My first easel was a cheap, wobbly thing, but it got the job done until a strong breeze decided it was time for an upgrade (mid-painting, naturally).

- Painting Surface: Small canvases, panels, or a sketchbook suitable for your medium. Smaller is often better when starting out, both for portability and managing time. I usually work on panels no larger than 12x16 inches outdoors.

- Paints: A limited palette is best for learning color mixing on the fly and keeping your gear light. Start with a few key primaries (a warm and cool version of each), plus white and maybe a dark. Less is definitely more when you're hauling everything! Trust me, you don't need 50 tubes.

- Brushes/Tools: A small selection of brushes or palette knives. Choose versatile shapes and sizes. I tend to favor flats and filberts for blocking in shapes quickly.

- Palette: A portable palette. For acrylics, a stay-wet palette is a game-changer in dry, windy conditions to keep your paint workable. For oils, a glass or wooden palette works well. Many plein air artists prefer a neutral grey palette as it helps judge color mixtures more accurately than white. I've used everything from a fancy glass palette to a simple plastic lid – whatever works!

- Solvent/Water: Depending on your medium. Bring enough for painting and cleanup. For oils, consider odorless mineral spirits. For acrylics/watercolors/gouache, just water. And maybe extra water just for drinking! Don't forget the drinking water.

- Rags/Paper Towels: Lots of them. Essential for cleaning brushes and wiping mistakes. I always bring more than I think I'll need. They also double as emergency napkins.

- Painting Umbrella: Crucial for shading your work and palette from direct sun or light rain. Seeing accurate color is impossible with direct sun glare! This was a game-changer for me – suddenly, my colors weren't all washed out. It also makes you look like a pro, which is a bonus.

- Wet Panel Carrier: Essential for transporting wet oil paintings safely without smudging them. These are boxes or carriers designed to hold panels or canvases with space between them so the wet paint doesn't touch anything. Acrylics and watercolors/gouache dry fast, so this is less critical. Don't learn this lesson the hard way like I did, ending up with a beautiful sunset painting smeared across my backpack. It was... abstract.

- Trash Bag: A small bag to collect all your trash (rags, paper towels, paint tubes, snack wrappers). Leave no trace!

- Comfort Items: Hat, sunscreen, bug spray, water, snacks, a comfortable stool if you don't have a French easel. Don't underestimate comfort – being miserable makes painting hard! A wide-brimmed hat is my best friend on sunny days. And snacks are non-negotiable.

Ready to pack your bag and head out? Great! Now let's talk about making the most of your time outdoors.

Strategies for Working Outdoors

Dealing with the unpredictable nature of painting outside requires a few specific strategies. These are things I've learned through trial and error (mostly error, if I'm honest!).

- Finding Your Spot and Composition: Look for interesting light, a compelling composition, and maybe a bit of shelter from the wind or sun. Pay attention to the direction of the light and how it hits your subject. Scouting locations beforehand or returning to the same spot at different times can be incredibly insightful.When choosing your view, don't try to paint everything. Simplify the scene! Identify the main elements that drew you in and focus on those. Think about how to frame the scene within your canvas – what to include, what to leave out. Look for strong shapes and values. Squinting helps simplify the scene into basic value masses. You can also use a small viewfinder (even just making a rectangle with your fingers) to isolate potential compositions. Bringing a simple value scale or gray card can also help you accurately judge the relative lightness and darkness of elements in the scene, which is crucial when the light is constantly shifting. Sometimes the most beautiful scene is also the most awkward to set up in – like that time I tried to paint a stunning view from a narrow, sloping path. My easel spent more time trying to slide downhill than standing upright.

- Working with Changing Light and Quick Techniques: This is the big one. The light will change. Embrace it. Here are a few strategies:

- Work Fast: Focus on capturing the overall impression, the large shapes, and the main light and shadow patterns quickly. Don't get bogged down in detail early on. This is where blocking in large areas of color and value first is key. Get the 'big shapes' down before they shift.

- Focus on Values: Light changes color, but values (how light or dark something is) are more stable for a while. Get your value structure right first. A quick grayscale or limited-color thumbnail sketch focusing only on values can be a lifesaver.

- Set a Time Limit: Decide beforehand you'll only work for 1-2 hours. This forces you to be decisive and accept the light as it was during that specific window.

- Embrace Wet-into-Wet (Alla Prima): For oils, working wet-into-wet (applying new paint layers onto wet paint) allows you to blend colors directly on the canvas and capture the scene quickly before paint dries or light shifts too much. For watercolors/gouache, mastering quick washes and layering before areas dry is essential.

- Take Notes/Sketches: Make quick thumbnail sketches or jot down color notes to remember fleeting effects you might want to refine later in the studio. Sometimes, the best outcome of a plein air session is a set of studies and notes that inform a larger piece back home.

- Handling Greens: Greens in nature can be overwhelming! They change dramatically with the light. Avoid using tube greens straight. Learn to mix your greens using blues and yellows, adding touches of red or purple to gray them down or make them warmer/cooler. Observe the subtle variations – sunlit grass is different from grass in shadow, and the green of a distant tree is different from one up close. It's a constant process of observation and mixing.

- Capturing Water and Reflections: Water is notoriously tricky. It's not just blue! It reflects the sky, the surrounding landscape, and can be transparent or opaque depending on depth and movement. Observe the shapes of the reflections and the values of the water itself. Quick, confident strokes are often better than hesitant ones when trying to capture moving water.

- Simplifying Foliage: Don't try to paint every leaf. Look for the large masses of light and shadow within trees and bushes. Observe the overall shape and texture. Use varied brushstrokes to suggest leaves and branches rather than meticulously painting each one. Squinting helps here too, turning complex foliage into simpler shapes.

Finding Locations and Permissions

Deciding where to paint is part of the adventure. Parks, beaches, hiking trails, urban squares, even your own backyard are all possibilities. Consider accessibility – how far do you have to carry your gear? Is the ground stable? Is there any shelter from potential rain or harsh sun?

In some locations, especially public parks or private property, you might need permission or a permit to set up an easel, particularly if you're part of a group or plan to be there for an extended period. It's always a good idea to check local regulations beforehand to avoid any awkward encounters. I've found that a friendly smile and keeping a low profile usually works wonders, but it's better to be prepared!

Joining a Plein Air Community

Painting alone outdoors can be a wonderful, meditative experience, but joining a local plein air group or attending 'paint-outs' can be incredibly rewarding. It's a fantastic way to learn from more experienced artists, get feedback, discover new locations, and simply enjoy the camaraderie of painting alongside others who understand the unique joys and frustrations of the practice. Sharing stories about wind disasters or bug invasions with fellow artists is surprisingly therapeutic!

Plein Air Exercises for Beginners

Ready to dip your toes in? Here are a few simple exercises to get you started without feeling overwhelmed:

- Value Study: Choose a simple scene or object. Using only black, white, and one or two shades of gray (or a single color and white), paint or sketch the scene focusing only on capturing the different levels of light and shadow. Ignore color completely. This is fundamental to understanding form and light.

- Limited Palette Study: Pick just 3-4 colors (e.g., a warm yellow, a cool blue, a red, and white). Paint a simple scene using only these colors. This forces you to focus on color mixing and understanding color relationships in natural light.

- Timed Sketch: Set a timer for 15-30 minutes. Choose a scene and try to capture its essence as quickly as possible. Don't worry about finishing; focus on getting down the main shapes, colors, and feeling before the time is up. Do this multiple times in different locations or at different times of day.

- Focus on One Element: Instead of painting the whole landscape, focus on just one tree, a section of a building, or a single flower. Study how the light hits it and try to capture that specific observation.

Managing Expectations and Embracing Imperfection

This is perhaps the most important tip. Your first plein air paintings probably won't be masterpieces. Mine certainly weren't! I've had canvases attacked by bugs, smeared by rain, and abandoned halfway through because the light vanished. It's okay. The value is in the experience and the learning. Each outing teaches you something new about observation, speed, and resilience. Embrace the happy accidents and the 'character-building' moments.

It's about the experience as much as the finished piece. Some of my favorite plein air pieces are quick, messy studies that perfectly capture the feeling of a windy afternoon or the glow of a sunset, even if they're not technically perfect. Remember, it's perfectly valid to use plein air studies as reference for larger, more refined works completed in the studio. Don't be afraid to call a piece a study and move on. Plein air is a skill, and like any skill, it improves with practice. Don't be discouraged by initial difficulties; see them as part of the learning curve. What do you do with these studies? Some artists frame them as they are, celebrating the raw energy of the moment. Others use them purely as visual notes, referring back to them in the studio to capture the light, color, or feeling of a scene more accurately in a larger, more controlled piece. They are invaluable reference material, a direct connection back to the experience of being there.

Documenting Your Process

Many plein air artists take photos or videos of their setup, the location, the scene they're painting, and the work in progress. This isn't just for social media! It serves as a valuable visual diary, helping you remember the conditions, the light, and the decisions you made during the session. These photos can be invaluable references if you decide to create a larger studio piece based on your outdoor study.

Being a Responsible Outdoor Artist

Painting outdoors means being a good steward of the environment. Always pack out everything you pack in. Be mindful of where you dispose of solvents or dirty water – ideally, take them home to dispose of properly. Avoid setting up in sensitive areas or trampling delicate vegetation. Leave the spot as you found it.

Essential Safety Tips Outdoors

Beyond just finding a safe location, there are other practical safety considerations when painting outdoors:

- Sun Protection: Wear sunscreen, a hat, and consider sun-protective clothing, even on cloudy days. The sun's glare can also make it hard to see your colors accurately, so a painting umbrella helps with this too.

- Hydration: Always bring plenty of water, especially in warm weather. It's easy to get absorbed in painting and forget to drink. I learned this the hard way once, getting so focused I didn't realize how dehydrated I was until I packed up.

- Dress Appropriately: Check the forecast and dress in layers. Weather can change quickly. Comfortable, sturdy shoes are a must, especially if you're hiking to a location.

- Awareness: Be aware of your surroundings. This includes uneven terrain, potential wildlife (beyond just bugs – think snakes, ticks, etc.), and traffic if you're in an urban area. Research the area beforehand for any specific hazards or local wildlife advisories. Be aware of poisonous plants like poison ivy, oak, or sumac.

- Inform Someone: Let someone know where you're going and when you expect to be back, especially if you're painting in a remote or less-trafficked area.

- Emergency Kit: Consider carrying a small first-aid kit, especially if you're in a remote location. Include basics like bandages, antiseptic wipes, pain relievers, and any personal medications.

Famous Plein Air Artists

While the Impressionists are the most famous proponents, the tradition continues today. Many contemporary artists work outdoors, finding inspiration and challenge in the direct observation of the world.

Beyond Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro, you can look at artists like John Singer Sargent, known for his dazzling portraits and watercolors that often captured figures and landscapes with a fresh, direct approach influenced by working outdoors, particularly his ability to render light on fabric and skin. Winslow Homer, particularly in his later works, masterfully captured the power and light of the sea in his watercolors, often painted en plein air, conveying the raw energy of the ocean. Contemporary artists like Richard Schmid are celebrated for their technical skill in capturing light and atmosphere outdoors, creating highly realistic landscapes, while others like Stephanie Birdsall continue the tradition with vibrant floral and garden scenes painted from life. Even artists known for other styles, like David Hockney, have experimented extensively with painting landscapes outdoors, often using vibrant colors and simplified forms to capture the essence of a place.

Is Plein Air for Everyone?

Honestly? Maybe not. If you prefer total control, pristine conditions, and the ability to tweak endlessly, the studio might be more your jam. And that's perfectly okay! There's no single 'right' way to make art. I've certainly had days where I packed up in frustration after battling the wind and decided the studio was my happy place.

But if you crave spontaneity, love being outdoors, and enjoy the challenge of working against the clock (and the elements), plein air might just open up a whole new world for you. It certainly has for me, adding a vibrant, sometimes chaotic, but always rewarding dimension to my artistic journey (see my timeline for proof of the chaos!). It's also a fantastic way to connect with other artists; joining a local plein air group or 'paint-out' can be incredibly motivating and a great way to share experiences and tips. Have you tried plein air? What was your most memorable moment (good or bad)?

It's a practice that teaches you flexibility, resilience, and a deeper appreciation for the ever-changing beauty of the world. It has profoundly influenced how I see light and color, even when I'm back in the controlled environment of my studio. It's taught me to be more decisive, to trust my initial impressions, and to find beauty in imperfection – lessons that spill over into all aspects of my art, including my more abstract work.

If you're interested in bringing some of that outdoor energy inside, you might find something you love in my collection.

FAQ: Your Plein Air Questions Answered

Here are some common questions people ask about painting outdoors:

- What kind of paint is best for plein air? It depends on your preference and the conditions. Oils stay wet longer, allowing for blending, but require solvents (or water-mixable oils) and wet transport solutions. Acrylics dry faster, which can be good for quick studies but challenging in hot, dry weather (they can 'color shift', meaning they dry darker than they appear wet). Watercolors, gouache, and pastels are also great, especially for portability and speed. (See the section "Choosing Your Medium for Plein Air" for more detail).

- How long does a typical plein air session last? It varies, but often artists work for 1-3 hours, focusing on capturing the light at a specific time. Any longer and the light changes too much, unless you're specifically studying the light's progression.

- How do I choose a subject or simplify a complex scene? Look for strong shapes, interesting light, and a clear focal point. Don't try to include everything! Use a viewfinder or squint to simplify the scene into basic shapes and values. Focus on capturing the essence rather than every detail.

- What's the most important piece of gear? A sturdy, portable easel is crucial. It needs to hold your canvas or panel securely, even in a breeze. A good painting umbrella is a close second for managing light and weather.

- How do you deal with glare from the sun? A painting umbrella is a lifesaver! It shades your canvas and palette, allowing you to see colors accurately. Positioning yourself with the sun behind you or to the side also helps.

- Can you finish a painting entirely outdoors? Sometimes, but often artists use plein air studies as reference for larger works completed in the studio. It's a personal choice – some aim for finished pieces, others for capturing information and feeling.

- What do you do with wet paintings? For oils, you need a wet panel carrier or a box designed to hold wet canvases/panels without them touching. Acrylics, watercolors, and gouache dry fast enough that this is usually less of an issue.

- How do you stay safe painting outdoors? Choose locations you know or that are well-trafficked during the day. Be aware of your surroundings – this includes checking for potential hazards like unstable ground, poison ivy, or even traffic in urban settings. Inform someone where you are going and when you expect to be back. Bring your phone and emergency supplies. Check the weather forecast before you go, and be prepared to pack up quickly if conditions change. (See the section "Essential Safety Tips Outdoors" for more detail).

Plein air painting is more than just a technique; it's an experience. It's about embracing the moment, connecting with your surroundings, and learning to work with, rather than against, the unpredictable beauty of the world. It has profoundly influenced how I see light and color, even when I'm back in the controlled environment of my studio. It's taught me to be more decisive, to trust my initial impressions, and to find beauty in imperfection – lessons that spill over into all aspects of my art, including my more abstract work.

If you're interested in bringing some of that outdoor energy inside, you might find something you love in my collection.

Happy painting!