Renaissance vs. Baroque Art: Unpacking the Grand Divide (and Why It Still Matters)

Ever wondered about the key differences between Renaissance and Baroque art? Join me as I dive into the philosophies, aesthetics, and enduring impact of these two monumental art movements, exploring what makes each unique and why they continue to captivate us today.

Renaissance vs. Baroque Art: Unpacking the Grand Divide (and Why It Still Matters)

Alright, settle in, because we're about to embark on a journey through two of art history's most compelling, and often misunderstood, periods: the Renaissance and the Baroque. What sets these two epochs apart isn't just a matter of dates or styles; it's a profound dialogue with human experience, a visual diary of an era's deepest convictions, its soaring ambitions, and its tumultuous anxieties. For me, art isn't just about pretty pictures; it's a vibrant, contrasting, and utterly pivotal conversation that continues to echo through the centuries. I mean, think about it: how often do we truly pause to consider why certain art movements captivate us, or why they emerged when they did? Beyond just looking at the 'what,' I'm always fascinated by the 'why' – the underlying currents, the societal shifts, the philosophical revolutions that shaped these masterpieces. This grand divide between Renaissance and Baroque art, for instance, continues to inform how we understand beauty, power, and humanity itself, resonating in contemporary discussions about art's purpose. In fact, if you've ever stood before a work of art and felt a tug, a whisper of a story from another time, you've already started this journey. I know I have. And that's exactly why we're going to dive deep, not just scratching the surface, but truly unearthing the beating heart of these two monumental periods, exploring how each era's unique spirit found expression in paint, marble, and grand architecture, and why their insights are still incredibly relevant today.

I remember staring at paintings, feeling their inherent difference, but struggling to put words to that intuition. Was it the costumes? The expressions? A general 'vibe' that whispered of something more? It was like trying to discern the secret ingredients of a master chef's dish without a recipe. But once you dive into the philosophical underpinnings, the seismic cultural shifts, and the distinctive visual languages each period forged, the 'why' becomes brilliantly clear. And trust me, this isn't just academic; understanding this grand divide illuminates so much about where we've come from, and even where we might be headed. It's a journey well worth taking – one that reveals how art isn't just created in a time, but actively shapes it. It's about seeing how the world, in all its messy glory, found its expression in paint, marble, and grand architecture. This isn't just a comparison; it's an exploration of how humanity grapples with its biggest questions, and how those questions are etched into the very fabric of our visual heritage. Personally, I find it's like learning the secret handshake of history; suddenly, everything clicks into place, revealing a much richer story than you ever imagined. It’s a bit like discovering the deep emotional currents beneath the surface of a beautiful melody – once you feel them, you can never just hear it the same way again. It's this deep dive into the 'why' that transforms mere looking into true understanding, and that's precisely what we're going to do together. I want to show you how these periods, despite their differences, are fundamentally connected, each a vital chapter in the ongoing story of human creativity. It’s a fascinating narrative of human ambition, spiritual yearning, and the constant evolution of how we choose to represent our world.

A Quick Peek at the Eras: When Did They Happen Anyway?

Before we dive headfirst into the juicy details, let's just ground ourselves with a quick timeline. Because knowing when these movements flourished, and where they truly took root, gives us crucial context for why they looked the way they did. It's not just about dates; it's about the cultural soil in which they grew, the hopes, fears, and triumphs of the people. Understanding the chronological relationship isn't just an academic exercise; it reveals a fascinating evolution, a conversation between epochs, each building upon or reacting against the last. It’s like watching a family tree grow, where each generation learns from and responds to the one before it. These periods, despite their distinct characteristics, were never truly isolated; they were in constant, dynamic conversation, shaping and reshaping the very definition of art itself. To truly appreciate the grand divide, we first need to anchor ourselves in their historical context and understand their foundational characteristics.

Art Period | Approximate Dates | Core Focus | Primary Geographical Centers | Key Historical Context | Key Artistic Innovations | Defining Mood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Renaissance | ~1280 - 1400 | Transition from Byzantine, early naturalism, human emotion | Tuscany (Florence, Siena) | Decline of feudalism, emergence of city-states, early mercantile wealth, pre-humanist stirrings. | Greater pictorial realism, emotional expressiveness, volumetric figures, early attempts at perspective, fresco cycles. | Dawning, formative, spiritual narrative |

| Early Renaissance | ~1400 - 1490 | Renewed classical interest, naturalism, civic humanism | Florence, Siena | Economic growth, rise of powerful city-states, early humanist scholarship. | Rediscovery of perspective, realistic portraiture, development of fresco. | Emerging, intellectual, observational |

| High Renaissance | ~1490 - 1527 | Ideal beauty, harmony, balance, universal genius | Rome, Florence | Zenith of papal power and patronage, flourishing of humanist ideals, Sack of Rome. | Sfumato, refined chiaroscuro, contrapposto, pyramidal composition, ultimate anatomical accuracy. | Serene, contemplative, idealized |

| Mannerism | ~1520 - 1600 | Artificiality, elegance, intellectual complexity | Florence, Rome, Northern Italy | Aftermath of High Renaissance, political and religious instability, desire for novelty. | Elongated figures, convoluted compositions, unsettling color palettes, exaggerated poses. | Elegant tension, sophisticated, unsettling |

| Baroque | ~1600 - 1750 | Drama, emotion, movement, grandeur, spiritual intensity | Italy (Rome), Spain, Flanders, France, Netherlands | Counter-Reformation (Catholic Church's response to Protestantism), absolutist monarchies (Louis XIV), Scientific Revolution (Newton), global expansion, colonization. | Tenebrism, illusionism (trompe l'oeil/quadratura), integrated arts (Gesamtkunstwerk), dramatic movement in sculpture, impasto, psychological realism. | Intense, theatrical, awe-inspiring |

See that overlap around 1600? That's not a typo. It's the moment the baton, or perhaps more accurately, the theatrical spotlight, began to pass. The Renaissance, with its calm, measured brilliance, started to give way to something more intense, more theatrical, more... extra. This wasn't just a shift in aesthetics; it was a profound cultural pivot. It's like the world decided it needed a bit more oomph – a direct response to a changing, often turbulent, world marked by religious upheaval, scientific revolutions, and global expansion. Think of it as a gradual crescendo, where the harmonies of the Renaissance slowly, but surely, built towards the dramatic complexities of the Baroque.

This period of transition, especially the latter half of the 16th century, is often referred to as Mannerism. It was a fascinating bridge, pushing the High Renaissance's harmonious balance towards more exaggerated, artificial forms – a kind of elegant tension that directly foreshadowed the Baroque's full-blown drama. Mannerist artists, reacting to the "perfection" of the High Renaissance, embraced elongated figures, convoluted compositions, and often unsettling color palettes, seeking novelty and intellectual complexity rather than naturalistic beauty. Think of Parmigianino's 'Madonna with the Long Neck' or El Greco's swirling, emotionally charged canvases; they deliberately distorted forms to create a sense of unease or sophisticated elegance. It was a stylistic 'twist' – a self-aware departure from the naturalism and serenity of the High Renaissance, almost a commentary on its own achievements. This era of stylish artificiality set the stage for the dramatic flair that would define the Baroque. Artists like Bronzino and Rosso Fiorentino also explored these exaggerated forms, focusing on elegant contortions and ambiguous narratives that challenged viewers to engage intellectually. The movement was a conscious departure, almost a rebellion, against the perceived 'perfection' of the High Renaissance, demonstrating that artistic merit could be found in sophisticated artifice and emotional tension rather than strict adherence to classical ideals. They really leaned into the 'style for style's sake' mentality, proving that art didn't always have to be about ideal naturalism to be compelling.

Beyond Italy, this period also saw the flourishing of the Northern Renaissance, a movement that, while sharing humanist ideals, diverged in its distinct focus on naturalism, meticulous detail, and everyday life. Unlike the grand, idealized forms of Italy, the Northern masters often explored rich symbolism in domestic scenes and grim realities, as you can explore further in our article on /finder/page/the-art-of-the-renaissance-in-northern-europe-beyond-italy. Masters like Jan van Eyck with his groundbreaking oil techniques and Albrecht Dürer with his profound engravings and woodcuts brought a different, equally compelling, dimension to the Renaissance spirit, often with a more stark and unvarnished realism. Their attention to minute detail and ability to render textures with incredible fidelity using newly refined oil paints set a benchmark for subsequent generations. This simultaneous flowering of diverse styles truly underlines the complexity of the transition from one epoch to the next. It’s like watching two different streams flow from the same source, each carving its own unique path through the landscape of art.

Beyond Italy, this period also saw the flourishing of the Northern Renaissance, a movement that, while sharing humanist ideals, diverged in its distinct focus on naturalism, meticulous detail, and everyday life. Unlike the grand, idealized forms of Italy, the Northern masters often explored rich symbolism in domestic scenes and grim realities, as you can explore further in our article on /finder/page/the-art-of-the-renaissance-in-northern-europe-beyond-italy. Masters like Jan van Eyck with his groundbreaking oil techniques and Albrecht Dürer with his profound engravings and woodcuts brought a different, equally compelling, dimension to the Renaissance spirit, often with a more stark and unvarnished realism. Their attention to minute detail and ability to render textures with incredible fidelity using newly refined oil paints set a benchmark for subsequent generations. Artists such as Hans Holbein the Younger also excelled in portraiture, capturing the psychological depth and individual character of their subjects with astounding precision. This simultaneous flowering of diverse styles truly underlines the complexity of the transition from one epoch to the next. It’s like watching two different streams flow from the same source, each carving its own unique path through the landscape of art.

The Core Philosophies: What Drove These Artists?

I really believe that to understand the art, you first have to grasp the headspace of the people creating it. What were they thinking? What were they trying to communicate? It's like trying to understand a conversation without knowing the language; the visual vocabulary of an era is deeply rooted in its dominant worldview. So, let's peel back the layers and explore the intellectual and spiritual currents that flowed through these artistic movements. For me, it’s about finding the beating heart of an era, the collective consciousness that guided the hands of these masters.

Renaissance: The Age of Reason and Human Potential

The Renaissance, a term that literally means "rebirth," was all about rediscovering the wisdom and beauty of ancient Greece and Rome. This wasn't just some dusty academic pursuit; it was a cultural explosion, re-evaluating everything from philosophy to civic life. People were absolutely enchanted by the idea of humanism – putting humanity at the center of existence, celebrating our achievements, our potential, our capacity for reason, and our individual worth. This intellectual movement, rooted in the rigorous study of classical Greek and Roman texts, fostered a profound belief in human dignity and the capacity for individual accomplishment. Figures like Petrarch, "the father of Humanism," and Erasmus championed a curriculum that focused on human values, rhetoric, and critical thought, directly influencing the arts and education across Europe. It was an optimistic time, despite all the wars and plagues (because, let's be honest, when is human history not complicated?). The emphasis shifted from the purely divine to the divine within humanity, leading artists to explore secular themes and portray religious figures with newfound psychological depth and individual character. Philosophers like Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, prominent in the Florentine Platonic Academy, integrated Neoplatonic ideas, seeing beauty as a reflection of divine perfection and the cosmos as an ordered, harmonious whole, which profoundly influenced artistic ideals of harmony, proportion, and idealized beauty. This pursuit of understanding the universe through human intellect was a driving force behind the era's scientific and artistic breakthroughs. The intellectual environment was further enriched by scholarly academies, such as the Florentine Platonic Academy, where thinkers engaged in lively debates and synthesized classical wisdom with Christian thought, fostering a truly interdisciplinary approach to knowledge. It’s almost as if humanity collectively decided to dust off its intellectual curiosity and see how far it could go, exploring the universe through both scientific observation and artistic creation. To truly grasp this philosophical backbone, I recommend our guide on /finder/page/what-is-humanism-in-renaissance-art.

Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo weren't just painters or sculptors; they were true Renaissance men – thinkers, scientists, anatomists, and engineers, embodying the era's ideal of universal accomplishment. They wanted to understand the world in all its rational glory, to depict it accurately, and to capture the ideal form of man and nature, often through rigorous study of anatomy and /finder/page/definitive-guide-to-perspective-in-art. There was a profound belief in order, balance, and harmony, echoing the perceived perfection of classical antiquity. It was about perfect proportions, clear lines, and compositions that felt utterly stable, almost serene, designed to invite calm, intellectual contemplation. This wasn't about raw emotion, but about elevating the human spirit through thoughtful beauty. The emphasis on classical ideals, scientific observation, and mathematical precision led to innovations like linear perspective and the ideal human form, as epitomized by Michelangelo's David and Leonardo's Vitruvian Man. Their dedication to capturing the world with scientific rigor, yet imbued with profound human emotion and idealized beauty, is what makes their work so enduring. It’s like they believed the universe itself was a perfectly structured masterpiece, and their art was an attempt to mirror that divine order, even exploring the subtle psychological depth of their subjects. The very concept of the Renaissance Man – a polymath skilled in many fields, like Leonardo himself – speaks to this era's high regard for universal accomplishment and intellectual versatility. If you haven't already, I highly recommend diving into our guide on /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-renaissance-art for a deeper look, exploring /finder/page/definitive-guide-to-perspective-in-art to understand their innovations in depth, or exploring the genius of /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-leonardo-da-vinci.

Baroque: Emotion, Drama, and the Divine

Then came the Baroque, and suddenly, everyone decided to turn up the volume! If the Renaissance was a thoughtful conversation in a quiet library, the Baroque was a grand opera, a fireworks display, a powerful sermon designed to move you to your core. This shift wasn't random; it was largely fueled by something called the Counter-Reformation. Following the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which sought to reform and reaffirm Catholic doctrine and address the challenges of the Protestant Reformation, the Church recognized the immense power of art as a spiritual weapon. Specific decrees from the Council, particularly those concerning religious imagery, explicitly encouraged art that would clarify doctrine, move the faithful to piety, and celebrate the saints and martyrs, directly opposing the iconoclasm and more austere aesthetics found in some Protestant traditions. This provided clear guidelines for artists, emphasizing legibility, emotional impact, and accuracy in depicting sacred subjects. The Church needed to reassert its power and appeal, to draw back the faithful, and to project an image of undeniable power and grandeur. And what better way to do that than through awe-inspiring, emotionally charged art that appealed directly to the senses, aiming to stir the soul and inspire profound devotion? This was a strategic, almost propagandistic, use of art to win back hearts and minds, proving that beauty and spectacle could be potent tools in a theological battle. It was a conscious, orchestrated effort to use art as a direct communication tool, a visual rhetoric to reaffirm faith and power.

But it wasn't just the Church; the rise of powerful, absolutist monarchs across Europe (like Louis XIV in France or the Habsburgs in Spain and Austria) also enthusiastically embraced the Baroque to glorify their own power and majesty. Art became a potent tool of state propaganda, with colossal palaces, heroic portraits, and grand public works designed to project an image of divine right to rule and unmatched splendor. Think of the opulent halls of Versailles, a testament to royal power and artistic collaboration, where the 'Sun King' meticulously crafted an image of unparalleled imperial grandeur. This dual patronage, both religious and secular, pushed Baroque art towards ever greater scales of ambition and emotional intensity, making it a truly 'public' art in a way the Renaissance rarely was. The philosophical underpinnings of this era, while complex, often grappled with the tension between human reason and divine revelation, as well as the absolute power of rulers. Thinkers like Hobbes articulated theories of strong central government, which mirrored the artistic expressions of absolute authority. It was a visual declaration, a constant, shimmering assertion of authority, both divine and earthly, aimed at impressing and controlling populations.

It was about eliciting a strong, often overwhelming, emotional response from the viewer, moving them to piety, wonder, awe, or even fear. Think about it: if you're standing in a dimly lit church and suddenly see a painting where a saint is dramatically ascending to heaven with light bursting from above, or a sculpture where a figure is caught in a moment of divine ecstasy, you're going to feel something profound, right? This visceral impact was a deliberate strategy. It was less about calm, rational contemplation and more about a direct, immediate experience designed to bypass the intellect and strike directly at the heart. There's an intensity, a sense of controlled chaos, and an undeniable theatricality, often blurring the lines between painting, sculpture, and architecture into a single, unified experience (a true Gesamtkunstwerk or "total work of art"). This dynamic energy sought to convey the grandeur and mystery of the divine, making the viewer a participant rather than a mere observer. It's like being swept up in a powerful current, you can't help but feel the force of it. It’s an art that grabs you by the collar and says, 'Look at this! Feel this!'. If this sounds like your cup of tea, you might enjoy exploring /finder/page/definitive-guide-to-baroque-art to learn more.

It's visually arresting, meant to grab your attention and hold it tight, often feeling much heavier and richer, like a rich tapestry of emotion and spectacle.

Patronage and Social Context: Who Paid for All This?

It's like understanding the client brief behind every grand project – it tells you a lot about the final product. And believe me, the patrons of these eras had very clear briefs indeed! You can't really talk about art without talking about who's funding it, can you? The patrons of the Renaissance and Baroque eras profoundly shaped the art that was created, reflecting their own values and ambitions. Their demands, their ideological needs, and their financial capabilities dictated the scale, subject matter, and even the style of the art produced, making patronage a fundamental force in shaping art history.

Renaissance Patronage: Church, City-States, and Wealthy Families

In the Renaissance, patronage was a complex web involving the powerful Catholic Church, independent city-states like Florence and Venice, and incredibly wealthy merchant families such as the Medicis. These patrons weren't just commissioning pretty decorations; they were investing in art as a symbol of their piety, power, and prestige. Think of the Medicis funding Michelangelo or Brunelleschi – it wasn't just for beauty, but to solidify their family's legacy and influence, assert their dominance, and even atone for sins. These powerful banking families, particularly the Florentine Medicis, transformed Florence into an artistic hub, viewing patronage as a form of political and social capital and a display of their sophisticated taste. Guilds, like the Wool Merchants' Guild, also played a significant role, commissioning public works (such as Ghiberti's "Gates of Paradise" for the Florence Baptistery) and ensuring high standards of craftsmanship through apprenticeships and workshops, fostering a vibrant artistic ecosystem. There was a strong civic pride, too, with public art commissions like Michelangelo's David becoming powerful symbols of liberty and civic virtue for city-states, standing defiantly against tyranny. Artists often worked for a mix of secular and religious clients, leading to a focus on idealized forms that celebrated both human achievement and divine glory. This blend of private wealth, civic ambition, and religious devotion created an unparalleled environment for artistic flourishing. Beyond the Medicis, other powerful families like the Strozzi and the Pitti also vied for artistic prestige, commissioning grand palaces and religious works that showcased their influence and taste. Guilds, representing various trades and crafts, were also crucial patrons, commissioning public sculptures and architectural projects that fostered a strong sense of civic identity and competition among artists. It was a symbiotic relationship, where artists gained commissions and patrons gained eternal glory, or at least, a really impressive display for their dinner guests. To truly appreciate their impact, I suggest exploring our /finder/page/art-lovers-guide-to-florence.

Baroque Patronage: The Church Triumphant and Absolute Monarchs

The Baroque era saw a shift, with the Catholic Church, invigorated by the Counter-Reformation, becoming an even more dominant patron. Art became a crucial tool in its spiritual arsenal, designed to overwhelm the senses and inspire profound religious devotion and loyalty, ensuring the faithful remained within the Catholic fold. Grand altarpieces, dramatic frescoes (often filling entire ceilings with illusionistic scenes), and elaborate church decorations were commissioned to awe the faithful and outshine the austere aesthetics of Protestantism. Simultaneously, the rise of powerful, absolute monarchs across Europe (like Louis XIV of France with his palace at Versailles, or the Spanish Habsburgs who commissioned Velázquez) also fueled the Baroque fire. They saw art and architecture as instruments of state power, commissioning colossal palaces, elaborate gardens, and heroic portraits to project their divine right to rule and their unmatched splendor. This era also saw the nascent rise of a broader art market and a burgeoning merchant class in places like the Netherlands and Flanders, leading to more genre scenes, portraits, and still lifes – reflecting a different kind of patronage entirely, focusing on secular subjects, domestic life, and the material world, as explored in /finder/page/the-art-of-the-dutch-golden-age-beyond-rembrandt. This diverse funding stream meant Baroque art could be found in the most sacred spaces, the grandest palaces, and the most intimate homes, a true reflection of its pervasive cultural influence. It was less about subtle influence and more about an overt display of wealth, power, and spiritual conviction, often with a theatrical flair that captured public imagination. The establishment of royal academies (like the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in France) during the Baroque era also centralized patronage and artistic control, dictating styles and subject matter to serve the interests of the monarchy, further solidifying the link between art and state power. This era saw art becoming a truly public spectacle, designed to impress and awe the masses.

Visual Language: The Artistic Signatures

Okay, so we've touched upon the 'why' – the philosophical and social currents that drove these movements. Now, let's get down to the 'how'. What specific visual tricks, techniques, and characteristic choices did these artists employ that make their work so distinct and instantly recognizable? This is where the real fun begins, peeling back the layers of paint and marble to understand their artistic fingerprints. You begin to understand their visual grammar, their deliberate choices, and the emotional resonance embedded in every brushstroke or chisel mark. To me, this is where the genius truly shines through – in the way they manipulated line, light, and color to tell their stories.

Here's a quick overview of their defining visual characteristics:

Feature | Renaissance Art | Baroque Art | Key Emotional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Aesthetic | Calm, rational, harmonious, balanced, idealized | Dramatic, emotional, dynamic, theatrical, opulent, sensuous | Serenity, contemplation vs. Awe, excitement, piety |

| Composition | Balanced, symmetrical, often pyramidal or rectangular. Figures arranged logically, often in clear groups. Emphasis on linear perspective and depth, closed compositions. | Dynamic, diagonal, swirling, often asymmetrical. Sense of movement and instability. Figures bursting out of the frame, dramatic foreshortening, open compositions. | Stability, order vs. Movement, tension |

| Lines | Clear, sharp, defined outlines (disegno). | Blurry, fluid, expressive lines, often dissolving forms into light and shadow (colorito). | Precision, clarity vs. Energy, emotion |

| Form | Clear, well-defined, sculptural, emphasizing ideal human anatomy. | Emotional, often exaggerated or twisted, emphasizing intense psychological states. | Idealized perfection vs. Intense realism |

| Realism | Idealized naturalism, striving for perfect beauty and anatomical accuracy. | Heightened, dramatic realism, sometimes gritty and unflinching, to evoke strong emotional responses. | Elevated, harmonious vs. Visceral, immediate |

| Space | Ordered, rational, receding into the distance logically, creating a window into a coherent world. | Expansive, theatrical, often overflowing, blurring the lines between painting and architecture (illusionism). The viewer feels drawn into the scene. | Predictable, infinite vs. Immersive, limitless |

| Light & Shadow | Gentle, diffused, sfumato for soft transitions. Early chiaroscuro for modeling. | Dramatic, high contrast, chiaroscuro and tenebrism with stark, often artificial illumination. | Naturalism, clarity vs. Mystery, revelation, intensity |

| Color Palette | Soft, naturalistic, harmonious, symbolic use of color, often built up with glazes. | Rich, vibrant, intense, often opulent golds, deep reds, blues, used for dramatic effect, bold impasto. | Grace, beauty vs. Grandeur, passion |

| Subject Matter | Idealized religious scenes, classical mythology, portraits emphasizing virtue, civic narratives. | Intense religious ecstasy/martyrdom, dramatic mythology, heroic portraits, genre scenes with earthy realism, allegories. | Reflection, dignity vs. Visceral engagement, wonder |

| Emotion | Dignified restraint, idealized emotional states, psychological depth for contemplation. | Raw, unbridled feeling, exaggerated gestures, peak moments of action/emotion, theatricality. | Serene, thoughtful vs. Overwhelming, immediate |

It's like learning to read the subtle cues in a person's body language; once you know what to look for, the art 'speaks' to you in a much richer way.

Composition: Order vs. Chaos (or Controlled Energy)

This is one of the most immediate giveaways, I've found. Just looking at how the elements are arranged in a piece tells you so much.

Feature | Renaissance Art | Baroque Art |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Balanced, symmetrical, often pyramidal or rectangular. Figures arranged logically, often in clear groups. Emphasis on linear perspective and depth. | Dynamic, diagonal, swirling, often asymmetrical. Sense of movement and instability. Figures bursting out of the frame, dramatic foreshortening. |

| Lines | Clear, sharp, defined outlines. | Blurry, fluid, expressive lines, often dissolving forms into light and shadow. |

| Movement | Static, restrained, controlled, figures often at rest or in contemplation. | Dynamic, swirling, dramatic, figures captured in moments of intense action or ecstasy, emotional fluidity. |

| Space | Ordered, rational, receding into the distance logically, creating a window into a coherent world. | Expansive, theatrical, often overflowing, blurring the lines between painting and architecture (illusionism). The viewer feels drawn into the scene. |

Renaissance artists were masters of /finder/page/definitive-guide-to-perspective-in-art, creating deep, rational spaces where every element felt perfectly placed, often using a central vanishing point to draw the eye. Think of a classic Raphael Madonna: perfectly centered, maybe a symmetrical background with a clear horizon. It just feels right, doesn't it? Even the most complex scenes, like Leonardo's 'Last Supper,' maintain an underlying geometric order, creating a sense of serene stability and intellectual calm, inviting a thoughtful, unhurried observation. This closed composition technique ensured that all elements were contained within the frame, fostering a contemplative engagement with the artwork. It's all about control, precision, and an almost scientific approach to visual harmony, reflecting a worldview that valued order and intellectual clarity.

Baroque art, on the other hand, embraces the diagonal. Everything seems to be twisting, turning, rushing into or out of the scene, creating a powerful sense of dynamism and emotional intensity. It's exhilarating! They really pushed the boundaries of foreshortening, making figures dramatically jut out or recede into the canvas, pulling you right into the action and often blurring the line between the artwork's space and our own. This use of open compositions (where elements extend beyond the visual confines of the canvas or frame) meant figures often extend beyond the traditional frame, suggesting a larger, unseen drama unfolding, inviting the viewer to imagine beyond the depicted moment. Think of the swirling heavens in a Bernini ceiling fresco, or the dynamic energy of Rubens's battle scenes; they almost burst out of their confines, demanding your full attention. This is a dramatic contrast to the more contained and stable compositions of the Renaissance, which often used closed compositions to create a sense of internal harmony within the artwork itself. It's like the difference between a perfectly framed portrait and a panoramic shot that spills off the edges, inviting you into a larger, more active world. This art wants to envelop you, not just show you a scene, making you a participant in its unfolding drama. Think of the way Tintoretto's compositions for the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice plunge figures into deep, dramatic spaces, or how Rubens's battle scenes burst with a chaotic yet controlled energy. These artists employed complex compositional devices, often leading the eye on a dramatic journey through the canvas, preventing any single focal point from dominating for too long, thus sustaining the viewer's engagement.

Light and Shadow: Chiaroscuro and Tenebrism

Here's where things get really dramatic. And I mean really dramatic. The way light behaves in a painting, how it falls, where it casts shadows – this is a masterstroke in both periods, but with vastly different intentions.

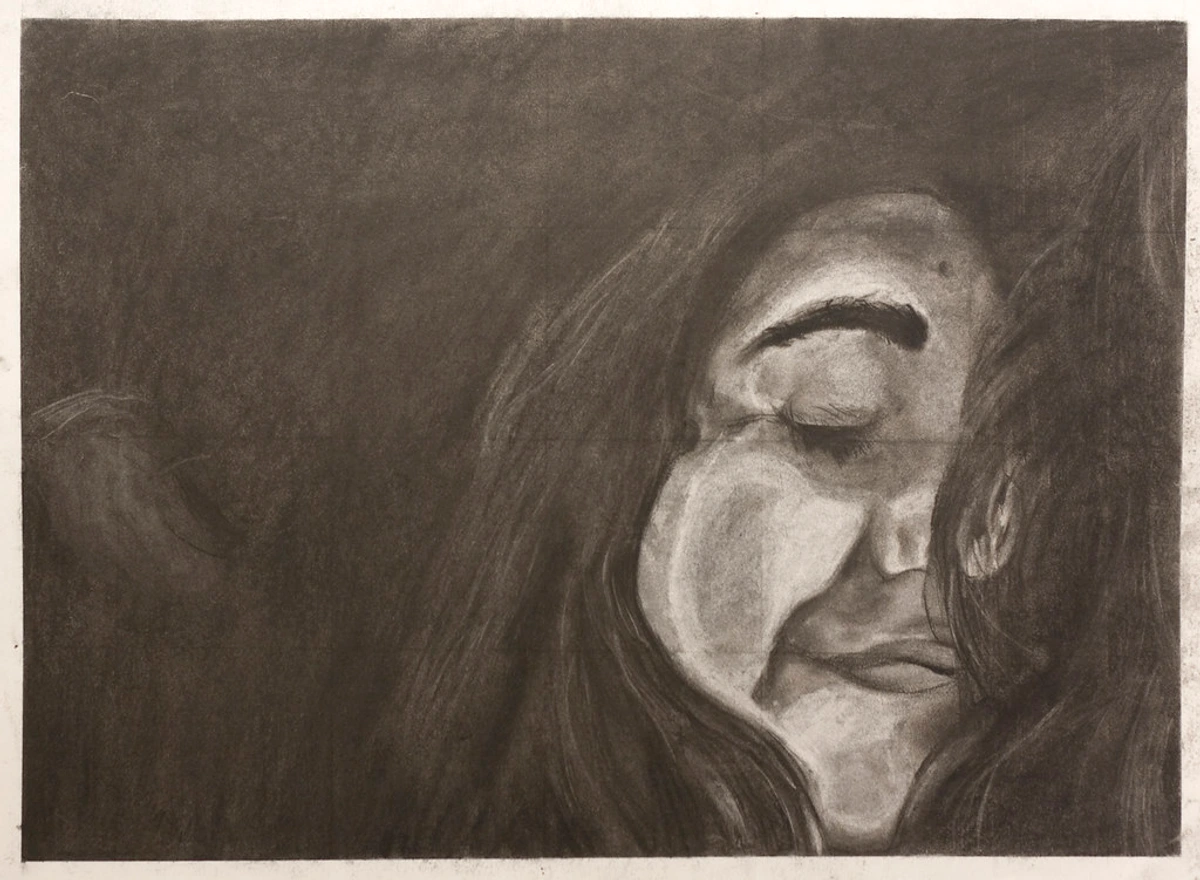

Renaissance painters used light to illuminate, to define forms softly and gradually, to create a sense of naturalism and harmony. It's often gentle, diffused, and evenly distributed, allowing you to appreciate the clear modeling of forms and figures with subtle gradations. Sfumato, famously perfected by Leonardo da Vinci, epitomizes this, creating a soft, hazy blurring of lines and colors, resulting in subtle transitions between light and shadow, giving figures a dreamlike, almost ethereal quality (think of the enigmatic smile of the Mona Lisa, which you can learn more about in our article on /finder/page/what-is-sfumato!). Early forms of chiaroscuro were also developed to give figures more volume and realism, meticulously modeling forms through gradual transitions of light and shade, enhancing the illusion of three-dimensionality. Think of the serene light in a Raphael fresco, bathing everything in a soft glow that emphasizes clarity and human grace, where every fold of drapery and every facial feature is softly but clearly defined. It was about revealing form, not obscuring it in drama. It’s light used for revelation, not agitation, creating a sense of calm intellectual contemplation. You can explore the technique further in our article on /finder/page/what-is-chiaroscuro-in-art-history-and-technique.

Baroque artists, however? They used light like a spotlight in a darkened theater, or a sudden burst of divine revelation. They practically perfected chiaroscuro – the strong, often theatrical, contrast between light and dark – and pushed it to its extreme with tenebrism, a technique where shadows dominate and only a few select areas are brightly, often starkly, illuminated. Caravaggio's work, for instance, is a masterclass in this, pulling figures out of oppressive darkness into a blinding, revelatory light in masterpieces like "The Calling of Saint Matthew" or "Judith Slaying Holofernes." This creates an incredible sense of drama, mystery, and often, an almost unsettling realism, pulling you directly into the emotional core of the scene. It's like someone turned off most of the lights and shone a single, intense beam right onto the most important part of the scene, making you feel the moment. You can't help but be drawn in, can you? It literally illuminates the narrative, making it feel like a sacred event unfolding before your very eyes. Beyond Caravaggio, artists like Artemisia Gentileschi and Georges de La Tour also employed tenebrism to profound effect, infusing their compositions with heightened emotional intensity and spiritual introspection. To learn more about these powerful techniques, check out our guides on /finder/page/what-is-chiaroscuro-in-art-history-and-technique and /finder/page/what-is-tenebrism-in-art.

This powerful use of light wasn't just aesthetic; it was designed to intensify the spiritual experience, to make the divine appear tangible and immediate. Beyond Caravaggio, artists like Artemisia Gentileschi used dramatic chiaroscuro to emphasize the heroism and suffering of her female protagonists, while Georges de La Tour employed a subtle, candlelit tenebrism to imbue humble scenes with profound spiritual introspection. This deliberate manipulation of light and shadow created a sense of theatricality and emotional urgency, drawing the viewer into the narrative with an almost palpable force. You can explore the technique further in our article on /finder/page/what-is-chiaroscuro-in-art-history and delve into its extreme form with /finder/page/what-is-tenebrism-in-art.

Color Palette: Serenity vs. Intensity

Another tell-tale sign is the color. It's not just what colors they used, but how they used them – the very psychology behind the palette. Renaissance art tends to favor softer, more naturalistic and harmonious colors, often applied in smooth, subtle transitions that create a gentle glow. Colors were often chosen for their symbolic value, like the deep Marian blue for the Virgin Mary, and pigments were carefully layered in thin, translucent glazes to achieve incredible luminosity, depth, and rich tonal variations – a hallmark of early oil painting mastery, particularly in the Venetian school with their emphasis on colorito. This focus on color and light distinguished the Venetians from the Florentine emphasis on disegno (drawing and design). Think of the delicate pastels on a Madonna's robe, the gentle blush on a cherub's cheek, or the verdant greens and muted blues of a Tuscan landscape, all rendered with an exquisite sense of clarity and detail. It's elegant, refined, and aims for a sense of calm beauty and idealized perfection, with colors serving to define form and volume with clarity and grace. It’s like a quiet, thoughtful conversation rendered in paint, where every hue plays its perfectly balanced part.

Baroque, on the other hand, isn't afraid to go bold. No, "bold" doesn't even begin to cover it! Rich, deep reds, intense blues, opulent golds, and dramatic blacks dominate. Colors are often more vibrant, more saturated, and used strategically to enhance the emotional impact, to draw the eye, and to create a sense of luxurious abundance or spiritual fervor. The use of rich, deep hues contributed to the overall sense of opulence and drama, often enhancing the perceived realism of the scene. Artists like Rubens, for example, used impasto (the thick, expressive application of paint, creating visible brushstrokes and palpable texture) to create palpable textures, energetic movement, and intensify the visual experience, making the surfaces almost tactile. It's less about delicate blending and more about powerful statements, sometimes even jarring or unexpected contrasts that add to the drama. It's visually arresting, meant to grab your attention and hold it tight, often feeling much heavier and richer, like a rich tapestry of emotion and spectacle. This was a deliberate move to heighten the sensory experience, to make the viewer feel the richness and intensity of the scene, rather than just observe it. It’s a full-throated symphony of color, demanding your full sensory engagement, making the divine feel strikingly immediate. To understand the deliberate choices behind these palettes, it's worth exploring /finder/page/definitive-guide-to-color-theory-in-art, as well as delving into /finder/page/the-emotional-language-of-color-in-abstract-art and /finder/page/the-psychology-of-color-in-abstract-art-beyond-basic-hues. Every artist, whether Renaissance or Baroque, employed color with purpose, and learning /finder/page/how-artists-use-color unlocks another layer of appreciation.

Subject Matter: From Humanism to Divine Spectacle

The stories they told also changed. Renaissance art, while often religious, focused on idealized forms and narratives that emphasized human dignity and intellectual achievement. Biblical scenes might show calm, collected figures, often presented with classical grace and profound psychological depth, inviting quiet contemplation of the sacred narrative. Portraits emphasized the individual's grace and composure, hinting at their inner virtue, intellectual prowess, and social standing, as seen in works like Leonardo's 'Mona Lisa'. Classical myths, rediscovered with renewed fervor, were depicted with clarity and often a moralizing or allegorical tone, reflecting the humanist rediscovery of antiquity and a burgeoning interest in secular learning. Themes of virtue, ideal beauty, and the dignity of man permeated much of the art. The focus was on universal ideals and a celebration of human potential, often through meticulously balanced compositions and harmonious colors. We've even touched upon the /finder/page/the-influence-of-byzantine-art-on-renaissance-painting in another article, showing the gradual evolution of themes and the expanding range of subject matter to include historical events, allegories, and even genre scenes with a refined touch. It’s a deliberate elevation of the human spirit, even when engaging with the divine. For a deeper dive into the meanings embedded in art, consider exploring /finder/page/understanding-symbolism-in-contemporary-art, which, while contemporary, often draws on historical precedents. You might also find fascination in /finder/page/understanding-the-symbolism-of-animals-in-art-history and /finder/page/understanding-the-symbolism-of-flowers-in-art-history to see how motifs transcended periods.

Baroque art, however, loved a good spectacle. Religious scenes often depicted moments of intense ecstasy (think Bernini's 'Ecstasy of Saint Teresa'), brutal martyrdom (like Caravaggio's dramatic depictions), or miraculous intervention, aiming to stir profound spiritual awe and reinforce Catholic doctrine. Battles were chaotic, myths were dramatic and often filled with sensuous energy, and portraits captured fleeting moments of emotion or grandeur, projecting power and psychological depth, as seen in Velázquez's court portraits. There's a heightened sense of movement, suffering, and divine power, reflecting the turbulent spiritual and political landscape of the era, deeply affected by the Thirty Years' War and colonial expansion. Everyday life scenes also took on a new vitality, particularly with artists in the Dutch Golden Age, who captured genre scenes with a raw, earthy energy and intricate detail, reflecting a burgeoning secular art market and the values of the rising merchant class. This shift ensured a broader range of human experience was immortalized in art, from grand historical narratives and profound spiritual visions to intimate domestic moments and still lifes brimming with symbolism (often referred to as vanitas). These artists didn't just tell stories; they performed them, drawing the viewer into a world of heightened sensation and moral contemplation. It's almost like they were directing a grand, visual play, and you, the viewer, were always in the front row.

Emotion and Expression: Restraint vs. Raw Feeling

Emotion and Expression: Restraint vs. Raw Feeling

This is perhaps the biggest, most visceral shift for me. How art handles human emotion tells you so much about the era's psyche. It’s the difference between a controlled sigh and an operatic scream, if you ask me.

Renaissance figures, even when depicting profound emotion like grief or adoration, often maintain a certain dignified restraint, a sense of controlled pathos. Their sorrow is noble; their joy is serene. It's about an idealized human form embodying a perfect, often generalized, emotional state – designed for calm, intellectual contemplation rather than immediate shock or visceral reaction. The emotion is certainly there, but it's contained, balanced, and harmonious, reflecting the era's belief in reason and order even in moments of passion. There's a profound psychological depth that invites quiet reflection, inviting you to connect with the subject on an intellectual and spiritual level, as seen in the contemplative expressions of many Madonnas, or the subtle tension in Leonardo's portraits. Think of the serene sorrow of Michelangelo's Pietà, where Mary's grief is profound but imbued with divine grace, inviting quiet reflection rather than overwhelming anguish. It's a testament to the power of inner strength and composure, even in the face of immense feeling, aiming for a universal expression of humanity's virtues. This measured approach to emotion is also reflected in the era's pursuit of compositional harmony, where even complex narratives are rendered with a sense of order. You can learn more about this in /finder/page/understanding-balance-in-art-composition.

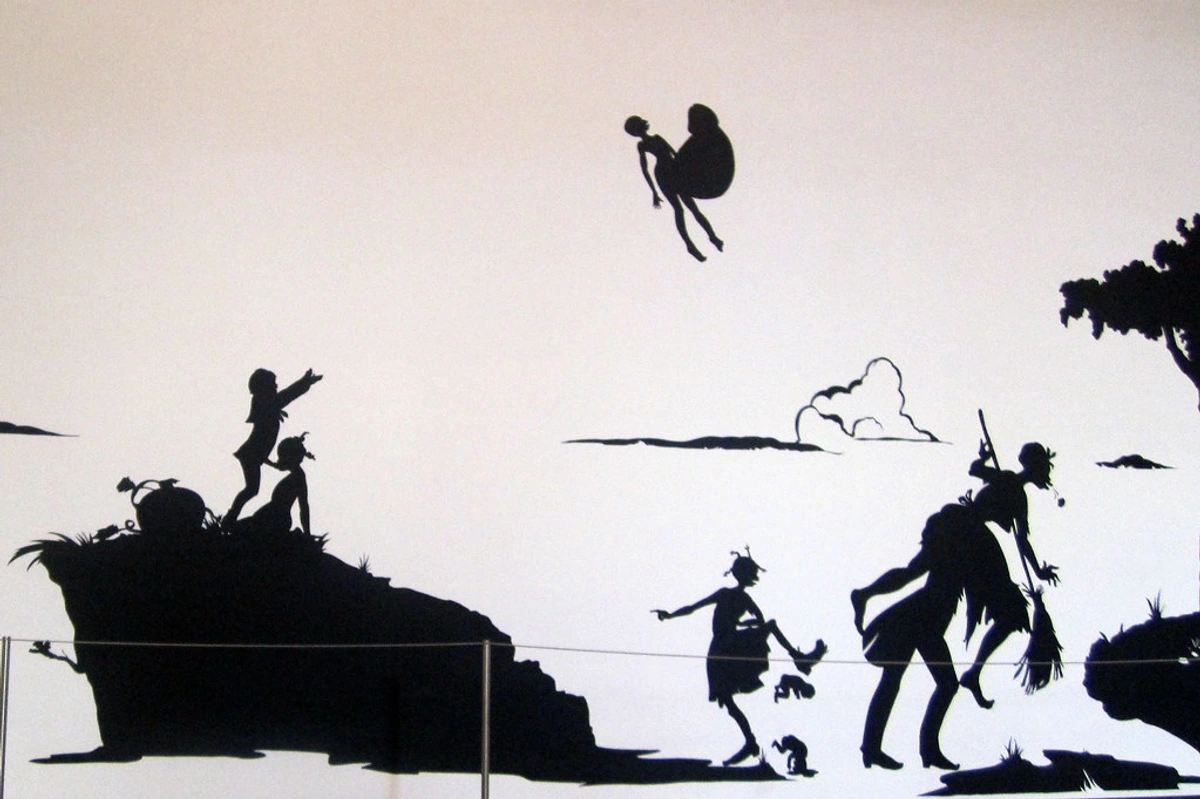

Baroque figures, conversely, wear their hearts on their sleeves, and then some! They are caught in the very act of feeling. Their faces are contorted in ecstasy or anguish, their bodies twisted in dynamic poses, their gestures exaggerated and expansive. You see anguish, ecstasy, terror, and passion in every muscle, every vein, and every swirling fold of drapery. It's about catching that peak moment of intensity, that raw, unbridled feeling, and pushing it to its dramatic extreme. It’s impossible not to react to it, isn't it? It demands your emotional engagement, right here, right now, as if you've stumbled into the climax of a grand play. Bernini's "Ecstasy of Saint Teresa" is a perfect embodiment of this, capturing a moment of profound spiritual rapture that is almost physically palpable, transforming marble into a vehicle for intense human emotion. This art doesn't just invite you to observe; it compels you to feel. The intensity of emotions often depicted in Baroque art, pushing the boundaries of human experience, can be seen as a precursor to later artistic movements that embraced raw psychological states. Though from a much later period, the visceral impact of Baroque emotionality perhaps foreshadowed the kind of dramatic expression seen in a work like Francis Bacon's 'Head VI' – an almost unsettling rawness.

This direct appeal to the emotions was a deliberate strategy to connect with viewers on a deeply personal and spiritual level, fostering devotion and wonder.

Key Innovations and Techniques: Beyond the Brushstroke

Beyond the stylistic differences, these periods were hotbeds of technical and conceptual innovation. Artists weren't just painting pretty pictures; they were pushing the boundaries of what art could do and be. It's almost like they were inventing new languages for expression, each with its own grammar and vocabulary. And for me, that's one of the most exciting aspects of art history – seeing how a new tool or technique can utterly transform the possibilities of creative expression, allowing artists to communicate complex ideas and emotions with unprecedented power.

Renaissance: Mastering Reality

The Renaissance was a period of intense scientific inquiry blended with artistic practice, fundamentally transforming how art was conceived and created. It was a time when artists were seen not just as craftsmen, but as intellectuals, scientists, and engineers, actively pushing the boundaries of knowledge. Key innovations include:

- Linear Perspective: A groundbreaking mathematical system to create the illusion of depth on a two-dimensional surface, codified and perfected by architects and artists like Filippo Brunelleschi and Masaccio. This literally changed how artists represented space, creating coherent, rational pictorial worlds that felt tangible and real, making the flat canvas a believable window into a three-dimensional scene. It was a revolution in how we perceive and represent reality, allowing for precise control over the illusion of depth. Pioneered by Filippo Brunelleschi and later meticulously documented and utilized by artists like Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, and Leonardo da Vinci, linear perspective transformed the two-dimensional surface into a convincing window onto a three-dimensional world. This mathematical approach to space not only enhanced realism but also reflected the era's broader intellectual curiosity and belief in rational order.

- Sfumato & Early Chiaroscuro: Leonardo da Vinci famously used sfumato, a soft, hazy blurring of lines and colors, to create subtle transitions between light and shadow, giving figures a dreamlike, almost ethereal quality (think the enigmatic smile of the Mona Lisa, which you can learn more about in our article on /finder/page/what-is-sfumato!). Early forms of chiaroscuro were developed to give figures more volume and realism, meticulously modeling forms through gradual gradations of light and shade, contributing to a heightened sense of three-dimensionality and weight. These techniques were about achieving a profound, yet subtle, naturalism, making figures feel truly present and psychologically real.

- Oil Painting Mastery: Though oil paints existed before (notably in the Northern Renaissance), Italian Renaissance artists fully embraced and mastered them, allowing for richer, more vibrant colors, smoother blends, longer working times (perfect for detailed rendering and corrections), and greater luminosity than tempera or fresco. This facilitated incredible realism, depth, and the ability to capture subtle atmospheric effects, bringing a new level of nuance and detail to their work. This was a game-changer for capturing the subtlety of the natural world and the texture of human skin. For a deeper dive into this revolutionary medium, you can explore our /finder/page/the-history-of-oil-painting-from-ancient-pigments-to-modern-masterpieces.

- Anatomical Study and Contrapposto: Artists undertook rigorous study of human anatomy, often through dissection, to depict the human form with unprecedented accuracy and naturalism. This was coupled with the revival of contrapposto, a natural, asymmetrical pose where the body's weight is shifted to one leg, giving figures a sense of dynamic potential and lifelike balance, moving away from rigid, frontal stances. This allowed for figures that felt truly alive and capable of movement, epitomized by masterpieces like Michelangelo's David. They wanted to understand the body, not just paint it, leading to a profound understanding of human physiology in art.

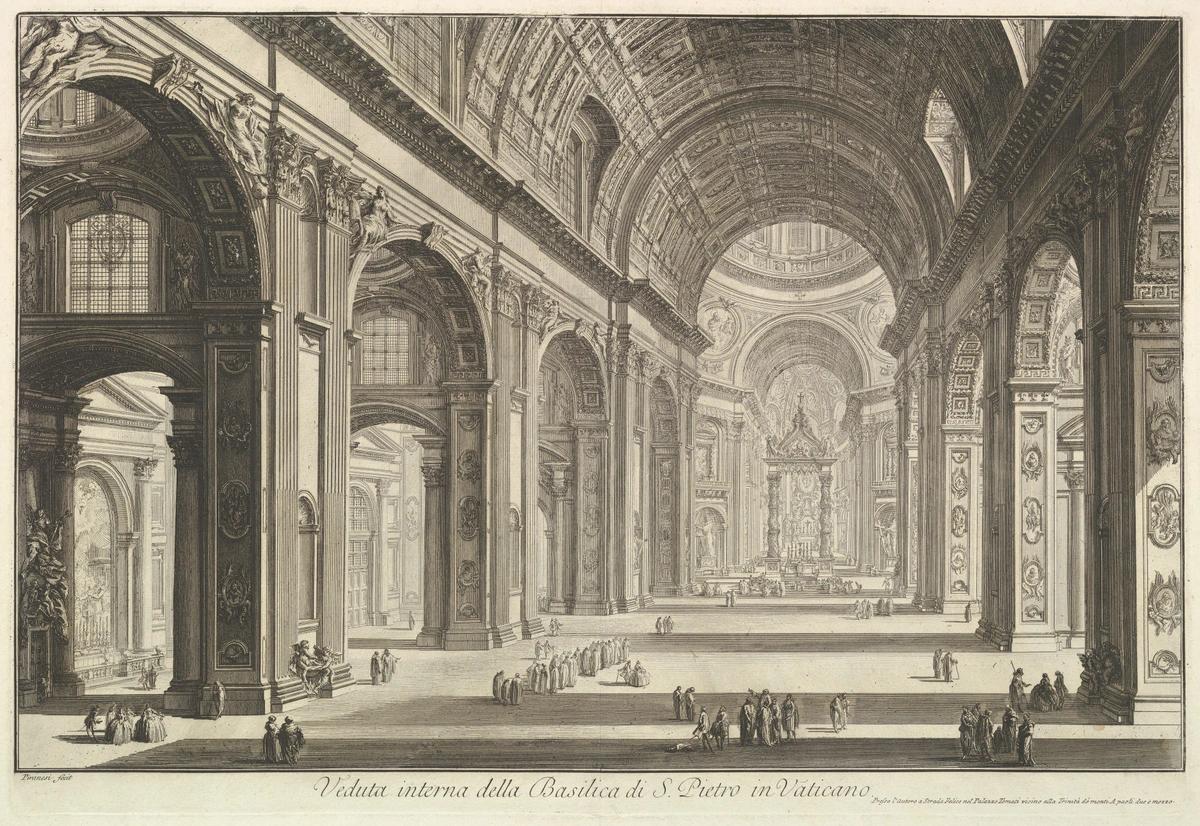

- Fresco Revival: Large-scale frescoes, like those in the Sistine Chapel or by Raphael in the Vatican, adorned churches and palaces, showcasing monumental narratives with vibrant colors, intricate compositions, and an enduring sense of classicism. This technique allowed for grand narratives to unfold across vast surfaces, creating immersive visual environments that reinforced sacred stories and civic ideals. Imagine creating a narrative on that scale – breathtaking, and a true test of an artist's skill and endurance!

- Classical Proportions: Drawing directly from ancient Greek and Roman architectural and sculptural theories (e.g., Vitruvius), Renaissance artists and architects like Leon Battista Alberti and Andrea Palladio applied mathematical ratios and ideal proportions to both figures and buildings, seeking universal beauty and harmony. The Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci perfectly encapsulates this pursuit of the perfectly proportioned human form as a microcosm of the universe. This mathematical rigor was seen as a path to divine beauty and order, a truly humanist endeavor. It was a belief that beauty could be found and understood through numbers, creating buildings that were both aesthetically pleasing and intellectually profound. Architects like Leon Battista Alberti, with his treatise 'De re aedificatoria,' and Andrea Palladio, known for his influential villas, meticulously applied these classical principles to create structures that were both visually striking and deeply resonant with humanist ideals of order and measure.

Baroque: Heightened Sensory Experience

The Baroque took many of these foundations and exaggerated them, harnessing new techniques to create a more immersive and emotionally powerful experience, pushing artistic boundaries to new heights of theatricality. They weren't content with merely showing you a scene; they wanted you to experience it, to be swept away by its drama.

- Tenebrism (Extreme Chiaroscuro): Caravaggio pushed chiaroscuro to its dramatic extreme, using deep, dominating shadows with stark, single-source illumination to create intense emotional and psychological effects. This technique dramatically heightened the realism and emotional impact, making sacred events feel immediate and relatable, drawing the viewer into the raw human experience, often with a gritty, unidealized portrayal of figures. His paintings became powerful, visceral sermons. It's like a sudden, blinding flash, revealing truth in the darkness.

- Illusionism (Trompe l'oeil & Quadratura): Especially in grand ceiling frescoes, Baroque artists used sophisticated perspective and quadratura (ceiling painting that extends architectural elements and dissolves into an illusion of open sky or heavens) to create breathtaking illusions, as if the ceiling had vanished entirely. Artists like Andrea Pozzo at the Church of Sant'Ignazio in Rome mastered this, dissolving architectural boundaries and offering a direct, overwhelming vision of the divine, as if the heavens themselves had opened above the viewer. It's truly a mind-bending experience, designed to transport the worshiper into a celestial realm. You genuinely feel like you're looking into another dimension, a trick of the eye that speaks to the era's ingenuity. These elaborate techniques, often featuring

trompe l'oeil(French for "deceive the eye") effects andquadratura(illusionistic ceiling painting), dissolved architectural boundaries and offered direct, overwhelming visions of the divine, as if the heavens themselves had opened above the viewer. Artists like Andrea Pozzo at the Church of Sant'Ignazio in Rome mastered this, transporting the worshiper into a celestial realm with breathtaking realism. - Integrated Arts (Gesamtkunstwerk): Baroque artists, particularly Gian Lorenzo Bernini, excelled at combining architecture, sculpture, and painting into a unified, theatrical experience within churches and chapels. This "total work of art" (Gesamtkunstwerk) was designed to overwhelm the senses, transforming sacred spaces into immersive spiritual dramas, as seen in the Cornaro Chapel with the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, where light, color, and form all converge to tell a powerful story, creating a truly all-encompassing sensory impact. This concept laid groundwork for later ornate styles like Rococo, which you can explore in our /finder/page/the-history-of-rococo-art-elegance-playfulness-and-grandeur and /finder/page/rococo-vs-baroque-art-key-differences articles. It was a deliberate fusion, an artistic symphony orchestrated to evoke a profound spiritual experience. Bernini's Cornaro Chapel, for instance, where the 'Ecstasy of Saint Teresa' is situated, exemplifies this, integrating sculpture, architecture, and hidden light sources to create a dramatic spiritual tableau that overwhelms the senses and truly makes the viewer a participant in a divine moment.

- Dramatic Movement in Sculpture: Figures in sculpture were no longer static but captured in moments of intense action, emotion, or divine ecstasy, often with swirling drapery and dynamic compositions that suggest fleeting moments of peak emotion or divine intervention. Bernini's 'Apollo and Daphne' is a prime example of this kinetic energy, capturing a mythological transformation mid-flight, making the marble seem to ripple with life and emotion. It was about depicting the climax of a narrative, a frozen moment of profound transformation, inviting the viewer to witness a sacred instant.

- Rich Color, Texture, and Impasto: Artists like Peter Paul Rubens employed vibrant, saturated colors and luxuriant textures, often using impasto (thick, visible application of paint) to enhance the visual and tactile richness of their works. This added a palpable sense of reality and emotional intensity to their dynamic compositions, making the paint itself feel alive and contributing to the overall sensuous appeal that was a hallmark of the Baroque. It's a feast for the eyes, and almost for the touch, too, creating an undeniable sense of vitality and abundance.

Key Artists and Their Masterpieces (A Taste of Genius)

Of course, no discussion of art history is complete without mentioning the titans who shaped these movements. These are the names that echo through the centuries, the artists whose visions continue to inspire and challenge us today. For me, diving into their individual contributions is like getting to know the distinct voices in a grand chorus.

Renaissance Heavyweights

When I think Renaissance, I immediately picture the big three: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Each brought their unique genius. Leonardo, with his enigmatic Mona Lisa (you can see her at the /finder/page/a-first-timers-guide-to-the-louvre-museum), mastered sfumato and anatomical precision, creating works of unparalleled psychological depth and a sense of profound mystery. Michelangelo, the divine artist, gave us the monumental Sistine Chapel ceiling, the powerful David (which you can learn more about in our /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-michelangelo), and the heart-wrenching Pietà, embodying 'terribilità' – a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur and sublime power that transcended mere human skill, deeply exploring the human condition. Raphael perfected the serene Madonna and monumental frescoes, renowned for their grace, clarity, and balanced compositions, creating scenes of ideal harmony and classical beauty. His 'School of Athens' in the Vatican is a prime example of his masterful composition and ability to celebrate classical philosophy alongside Christian theology, embodying the Renaissance's intellectual synthesis. These artists weren't just painting; they were redefining what art could be, setting a standard that would influence generations. Then there's Botticelli, whose Primavera and The Birth of Venus (explore his genius further in /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-botticelli-master-of-the-early-renaissance) burst with classical beauty and allegorical meaning, bringing pagan mythology to life with exquisite detail and a distinctly lyrical style. These artists weren't just painting; they were redefining what art could be, setting a standard that would influence generations.

We can't forget the vibrant Venetian Renaissance, with masters like Titian, whose rich colors (colorito) and painterly approach redefined portraiture and mythological scenes, challenging the Florentine emphasis on drawing (disegno). His ability to convey texture and light through color was revolutionary, creating works of incredible sensuality and psychological depth like 'Assumption of the Virgin' and 'Bacchus and Ariadne'. And Tintoretto, known for his dramatic use of perspective, light, and dynamic compositions that often foreshadowed the Baroque's intensity, creating emotionally charged narratives like 'The Last Supper' (San Giorgio Maggiore). Paolo Veronese also contributed with his opulent, grand-scale narratives, such as 'The Wedding Feast at Cana', which captured the lavishness of Venetian society. These artists, and many others across Italy, laid the foundation for Western art for centuries, pushing the boundaries of realism and idealization, and creating a dialogue between drawing and color that would last for generations. It’s like the Florentines gave us the perfect skeleton, and the Venetians dressed it in the most luxurious, shimmering robes. Then there's Botticelli, whose Primavera and The Birth of Venus (explore his genius further in /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-botticelli-master-of-the-early-renaissance) burst with classical beauty and allegorical meaning, bringing pagan mythology to life with exquisite detail and a distinctly lyrical style. We can't forget the vibrant Venetian Renaissance, with masters like Titian, whose rich colors (colorito) and painterly approach redefined portraiture and mythological scenes, challenging the Florentine emphasis on drawing (disegno). His ability to convey texture and light through color was revolutionary, creating works of incredible sensuality and psychological depth like 'Assumption of the Virgin' and 'Bacchus and Ariadne'. And Tintoretto, known for his dramatic use of perspective, light, and dynamic compositions that often foreshadowed the Baroque's intensity, creating emotionally charged narratives like 'The Last Supper' (San Giorgio Maggiore). Paolo Veronese also contributed with his opulent, grand-scale narratives, such as 'The Wedding Feast at Cana', which captured the lavishness of Venetian society. These artists, and many others across Italy, laid the foundation for Western art for centuries, pushing the boundaries of realism and idealization, and creating a dialogue between drawing and color that would last for generations. It’s like the Florentines gave us the perfect skeleton, and the Venetians dressed it in the most luxurious, shimmering robes.

It's also vital to acknowledge the Northern Renaissance, with figures like Albrecht Dürer, a master printmaker and painter known for his meticulous detail, intricate symbolism, and profound psychological realism in works like 'Melencolia I' or his self-portraits. And Jan van Eyck, whose revolutionary oil painting techniques and intense naturalism are exemplified in works like the Ghent Altarpiece or 'The Arnolfini Portrait', capturing exquisite detail and luminous effects. Hieronymus Bosch, with his surreal and moralizing narratives like 'The Garden of Earthly Delights', offered a distinct, imaginative vision. Their work, while sharing humanist ideals, often presented a more earthly realism, a focus on everyday life, and a moralizing tone, offering a rich counterpoint to the Italian masters. They showed that the Renaissance spirit could flourish with a different accent, focusing on the minute details of the world around us, often with a powerful, almost spiritual, intensity. Figures like Albrecht Dürer, a master printmaker and painter known for his meticulous detail, intricate symbolism, and profound psychological realism in works like 'Melencolia I' or his self-portraits, expanded the possibilities of artistic dissemination through printmaking. And Jan van Eyck, whose revolutionary oil painting techniques and intense naturalism are exemplified in works like the Ghent Altarpiece or 'The Arnolfini Portrait', captured exquisite detail and luminous effects, setting a new standard for realism. Hieronymus Bosch, with his surreal and moralizing narratives like 'The Garden of Earthly Delights', offered a distinct, imaginative vision that delved into the complexities of human sin and redemption. Their work, while sharing humanist ideals, often presented a more earthly realism, a focus on everyday life, and a moralizing tone, offering a rich counterpoint to the Italian masters.

You can delve into this fascinating regional variation in our guide to /finder/page/the-art-of-the-renaissance-in-northern-europe-beyond-italy.

Baroque Powerhouses

Now, for the Baroque crew, get ready for some intense personalities and unparalleled mastery of drama! Caravaggio practically invented modern tenebrism, his brutal realism, dramatic use of light and shadow, and unflinching depiction of human struggle revolutionized painting. Works like "The Calling of Saint Matthew" and "The Conversion of Saint Paul" are utterly gripping, pulling sacred events into the gritty reality of everyday life, making the divine accessible and immediate, almost shockingly so. You can delve deeper into his genius with our /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-caravaggio. His contemporary, Artemisia Gentileschi, was an incredibly powerful female artist whose work, like her "Judith Slaying Holofernes," is full of emotional raw power and frequently explores themes of strong women facing adversity, often drawing from her own traumatic experiences, as you can read more about in our /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-artemisia-gentileschi. Her powerful narratives offer a compelling perspective on the era's dramatic sensibilities, often with a psychological intensity that mirrors Caravaggio’s raw emotional force. Beyond her 'Judith Slaying Holofernes,' works like 'Susanna and the Elders' further exemplify her ability to infuse classical narratives with profound emotional depth and a sense of direct, unflinching confrontation with adversity. These two artists, in particular, weren't afraid to confront the raw, messy truth of human experience, even when depicting sacred stories, giving a voice to often overlooked narratives. These two artists, in particular, weren't afraid to confront the raw, messy truth of human experience, even when depicting sacred stories, giving a voice to often overlooked narratives.

Then there's Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the ultimate Baroque sculptor and architect, whose works like the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa practically redefine drama in marble, blurring the lines between media to create a truly immersive religious experience – a masterpiece of the Gesamtkunstwerk. His soaring Baldacchino in St. Peter's Basilica is another breathtaking example of his integrated artistic vision, an iconic symbol of the Counter-Reformation's grandeur and theatricality. And how could we forget the exuberant energy and lavish compositions of Peter Paul Rubens, whose large-scale altarpieces, mythological scenes, and portraits are a riot of color and movement, often depicting muscular figures, rich textures, and dynamic narratives, bringing a palpable sensuality to his canvases, as seen in works like 'The Elevation of the Cross' or 'The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus'. In Spain, Diego Velázquez captured the court with unparalleled psychological insight and technical brilliance, famously in "Las Meninas," a complex and intriguing portrait of royal life and artistic illusion that still confounds and delights viewers today, masterfully playing with perspective and the viewer's gaze. And in France, artists like Nicolas Poussin (with his more classical Baroque style, emphasizing order and intellectual rigor in works like 'Et in Arcadia Ego') and Georges de La Tour (with his stark, candlelit tenebrism, revealing intense spiritual introspection in humble settings like 'Magdalene with the Smoking Flame') offered their own unique interpretations of the era's spirit, demonstrating the breadth of Baroque expression. Each one, in their own unique way, contributed to the era's grand spectacle and profound emotional resonance. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the ultimate Baroque sculptor and architect, whose works like the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa practically redefine drama in marble, blurring the lines between media to create a truly immersive religious experience – a masterpiece of the Gesamtkunstwerk. His soaring Baldacchino in St. Peter's Basilica is another breathtaking example of his integrated artistic vision, an iconic symbol of the Counter-Reformation's grandeur and theatricality. And how could we forget the exuberant energy and lavish compositions of Peter Paul Rubens, whose large-scale altarpieces, mythological scenes, and portraits are a riot of color and movement, often depicting muscular figures, rich textures, and dynamic narratives, bringing a palpable sensuality to his canvases, as seen in works like 'The Elevation of the Cross' or 'The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus'. In Spain, Diego Velázquez captured the court with unparalleled psychological insight and technical brilliance, famously in "Las Meninas," a complex and intriguing portrait of royal life and artistic illusion that still confounds and delights viewers today, masterfully playing with perspective and the viewer's gaze. And in France, artists like Nicolas Poussin (with his more classical Baroque style, emphasizing order and intellectual rigor in works like 'Et in Arcadia Ego') and Georges de La Tour (with his stark, candlelit tenebrism, revealing intense spiritual introspection in humble settings like 'Magdalene with the Smoking Flame') offered their own unique interpretations of the era's spirit, demonstrating the breadth of Baroque expression.

Finally, we turn to the profound psychological depth and unparalleled mastery of light from Rembrandt van Rijn in the Dutch Golden Age, whose self-portraits and biblical scenes explore the human condition with intense introspection, revealing inner emotional states rather than external drama. His ability to convey profound emotion through subtle shifts in light and shadow is simply breathtaking. You can delve into his mastery with our /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-rembrandt-van-rijn. And speaking of Dutch masters, Johannes Vermeer brought a quiet, luminous intimacy to genre scenes, captivating us with works like "Girl with a Pearl Earring" (discover more at /finder/page/what-is-the-girl-with-a-pearl-earring), where a single beam of light illuminates inner worlds with exquisite detail, creating an almost timeless quality. These Dutch masters, operating in a different patronage system, showed that the Baroque spirit could thrive in diverse cultural and economic landscapes, focusing on the beauty of the everyday rather than grand narratives. Finally, we turn to the profound psychological depth and unparalleled mastery of light from Rembrandt van Rijn in the Dutch Golden Age, whose self-portraits and biblical scenes explore the human condition with intense introspection, revealing inner emotional states rather than external drama. His ability to convey profound emotion through subtle shifts in light and shadow is simply breathtaking. You can delve into his mastery with our /finder/page/ultimate-guide-to-rembrandt-van-rijn. And speaking of Dutch masters, Johannes Vermeer brought a quiet, luminous intimacy to genre scenes, captivating us with works like "Girl with a Pearl Earring" (discover more at /finder/page/what-is-the-girl-with-a-pearl-earring), where a single beam of light illuminates inner worlds with exquisite detail, creating an almost timeless quality. These Dutch masters, operating in a different patronage system, showed that the Baroque spirit could thrive in diverse cultural and economic landscapes, focusing on the beauty of the everyday rather than grand narratives. It's truly a testament to the versatility of the Baroque spirit, adaptable to both sacred drama and quiet domesticity.

Each one, in their own way, pushed the boundaries of what art could express, leaving an indelible mark on art history.

Beyond the Canvas: Music, Literature, and Philosophy

It’s fascinating to me how the artistic spirit of an era doesn’t just confine itself to visual arts; it permeates every creative and intellectual endeavor. The Renaissance and Baroque periods, in their distinct ways, birthed revolutionary movements in music, literature, and philosophy that echoed the same underlying shifts we see in painting and sculpture. It's like the whole intellectual and emotional atmosphere of the time found expression in every possible medium.

Renaissance: Harmony, Humanism, and Polyphony

In literature, the Renaissance saw a resurgence of classical forms and a profound focus on human experience. Think of the epic poetry of Dante Alighieri, whose Divine Comedy bridged medieval and Renaissance thought; the lyrical sonnets of Petrarch, which explored the depths of individual emotion; the witty storytelling of Boccaccio in The Decameron, capturing secular life; or Shakespeare's profound exploration of human nature in his timeless plays, reflecting the era's fascination with individual character and moral dilemmas. Castiglione's The Courtier defined the ideal Renaissance gentleman, influencing social norms for centuries with its emphasis on grace, sprezzatura, and intellectual accomplishment. Machiavelli's incisive political philosophy in The Prince boldly broke from traditional moralizing, offering a pragmatic, sometimes ruthless, view of leadership, a true reflection of the era's evolving political landscape and the rise of powerful, often secular, rulers. Philosophy, deeply influenced by humanism and Neoplatonism, sought to reconcile classical thought with Christian theology, fostering intellectual inquiry and a new understanding of the individual's place in the cosmos. Figures like Erasmus advocated for a return to original classical and biblical texts, promoting critical thought and individual spiritual experience, laying groundwork for the Reformation. In literature, the Renaissance saw a resurgence of classical forms and a profound focus on human experience. Think of the epic poetry of Dante Alighieri, whose Divine Comedy bridged medieval and Renaissance thought; the lyrical sonnets of Petrarch, which explored the depths of individual emotion; the witty storytelling of Boccaccio in The Decameron, capturing secular life; or Shakespeare's profound exploration of human nature in his timeless plays, reflecting the era's fascination with individual character and moral dilemmas. Castiglione's The Courtier defined the ideal Renaissance gentleman, influencing social norms for centuries with its emphasis on grace, sprezzatura, and intellectual accomplishment. Machiavelli's incisive political philosophy in The Prince boldly broke from traditional moralizing, offering a pragmatic, sometimes ruthless, view of leadership, a true reflection of the era's evolving political landscape and the rise of powerful, often secular, rulers. It was a period of intellectual awakening that spanned every discipline, seeing humanity as capable of immense intellectual and creative achievement.

Musically, this was the age of polyphony, where multiple independent melodic lines intertwined harmoniously. Composers like Josquin des Prez and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina created intricate masses, motets, and chansons, characterized by balance, clarity, and a serene beauty that mirrors the visual arts' emphasis on order and proportion. The development of music printing also helped disseminate these compositions, spreading the Renaissance sound across Europe, making complex music more accessible. Madrigals, secular vocal pieces, also flourished, allowing for expressive storytelling through music, often reflecting the humanistic themes of love, nature, and pastoral ideals, providing a delightful sonic counterpart to the era's paintings. Musically, this was the age of polyphony, where multiple independent melodic lines intertwined harmoniously. Composers like Josquin des Prez, famed for his expressive motets and masses, and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, whose sacred music epitomized the Counter-Reformation's ideals of clarity and reverence, created intricate masses, motets, and chansons, characterized by balance, clarity, and a serene beauty that mirrors the visual arts' emphasis on order and proportion. The development of music printing also helped disseminate these compositions, spreading the Renaissance sound across Europe, making complex music more accessible. Madrigals, secular vocal pieces, also flourished, allowing for expressive storytelling through music, often reflecting the humanistic themes of love, nature, and pastoral ideals, providing a delightful sonic counterpart to the era's paintings. Imagine a choir, each voice distinct yet perfectly blended – that's the Renaissance in sound, a testament to intricate design and harmonious cooperation.

Baroque: Drama, Emotion, and the Grand Scale

Literature in the Baroque period embraced drama, emotion, and grand narratives, often reflecting the era's spiritual and political turbulence. John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost explores themes of good, evil, and free will with immense grandeur and heightened language, much like a Baroque altarpiece, using vivid imagery and complex narrative structures. Spanish playwrights like Lope de Vega and Calderón de la Barca produced vast numbers of plays, often with complex plots and moral dilemmas that thrilled audiences, while French dramatists like Molière brilliantly satirized society with his comedies, revealing the foibles of the time and the dramatic contrasts of human behavior. Philosophers like René Descartes questioned reality, famously declaring "I think, therefore I am," ushering in an era of rationalism that paradoxically coexisted with the Baroque's emotional intensity and religious fervor, demonstrating the era's intellectual dynamism. Thinkers like Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz further developed complex systems of thought that grappled with the nature of existence, God, and human knowledge, influencing the Age of Enlightenment that followed. Literature in the Baroque period embraced drama, emotion, and grand narratives, often reflecting the era's spiritual and political turbulence. John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost explores themes of good, evil, and free will with immense grandeur and heightened language, much like a Baroque altarpiece, using vivid imagery and complex narrative structures. Spanish playwrights like Lope de Vega and Calderón de la Barca produced vast numbers of plays, often with complex plots and moral dilemmas that thrilled audiences, while French dramatists like Molière brilliantly satirized society with his comedies, revealing the foibles of the time and the dramatic contrasts of human behavior. It’s a period where the human intellect soared, even as emotions ran wild, reflecting a society grappling with profound spiritual and scientific shifts.

Baroque Philosophy: Reason, Faith, and the Human Condition

Philosophers like René Descartes questioned reality, famously declaring "I think, therefore I am," ushering in an era of rationalism that paradoxically coexisted with the Baroque's emotional intensity and religious fervor, demonstrating the era's intellectual dynamism. Thinkers like Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz further developed complex systems of thought that grappled with the nature of existence, God, and human knowledge, influencing the Age of Enlightenment that followed. This was a time of immense intellectual ferment, as humanity sought to reconcile new scientific discoveries with deeply held spiritual beliefs, leading to a richer, more complex understanding of the human condition.