The Art of the Dutch Golden Age: Beyond Rembrandt's Shadow

Explore the rich tapestry of the Dutch Golden Age art, delving beyond Rembrandt to discover masters like Vermeer, Hals, Steen, and the diverse genres that defined this extraordinary era.

The Art of the Dutch Golden Age: Beyond Rembrandt's Shadow - A Comprehensive Guide

The Dutch Golden Age, a period spanning roughly the 17th century, is renowned for its explosive economic growth, scientific advancement, and a flourishing of the arts. While the name Rembrandt van Rijn often stands as the preeminent symbol of this era's artistic brilliance, his genius represents merely one facet of a remarkably diverse and innovative artistic landscape. To truly appreciate the depth of this period, one must venture beyond his monumental legacy and explore the myriad of artists and genres that shaped this unique cultural moment. This comprehensive guide will illuminate the artistic brilliance of the era, exploring the societal shifts, diverse genres, influential artists, and enduring legacy that continue to captivate audiences worldwide.

Table of Contents

- A Flourishing Canvas: The Context of the Golden Age

- Masters of Light and Everyday Life

- Judith Leyster: The Independent Female Master

- Johannes Vermeer: The Enigmatic Master of Domesticity

- Pieter de Hooch: Intimate Glimpses of Domestic Life

- Frans Hals: The Master of the Spontaneous Brushstroke

- Jan Steen: The Humorous Storyteller

- Diverse Genres of the Golden Age

- Aelbert Cuyp: The Master of Golden Light and Pastoral Landscapes

- Landscape Painting

- Still Life

- Flower Painting: A Vibrant Specialization

- Marine Painting

- History Painting

- Architectural Painting

- Portraiture: Beyond the Individual

- Tronje: The Character Study

- The Workshop System and Artistic Training

- Rembrandt's Enduring Influence

- The Enduring Legacy

- Frequently Asked Questions About Dutch Golden Age Art

- Conclusion

A Flourishing Canvas: The Context of the Golden Age

The Netherlands in the 17th century was a new republic, driven by unparalleled global trade, religious freedom, and a powerful merchant class. The economic might, largely fueled by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and its vast colonial ventures (which, let's be frank, had a complicated and often brutal impact globally), created unprecedented wealth. This era saw the rise of Amsterdam as a global financial hub, and the innovative practices of mercantile capitalism fundamentally reshaped Dutch society. This prosperity, coupled with a relatively tolerant Protestant (primarily Calvinist) environment, profoundly impacted art patronage and the very nature of artistic output. The Protestant Reformation, which valued piety and simplicity, meant less demand for grand religious iconography in churches. Unlike the Catholic countries where the Church and aristocracy were primary patrons, commissioning grand religious or mythological narratives, in the Dutch Republic, a burgeoning middle class fueled a demand for art that reflected their daily lives, values, and aspirations. This included sober portraits, moralistic genre scenes, and serene landscapes, all reflecting a deep pride in their newfound nation and its bourgeois virtues. This societal shift led to a remarkable diversification of subject matter and a departure from traditional themes towards the intimate narratives of genre scenes, realistic portraits, evocative landscapes, and meticulously rendered still lifes.

This unique confluence of economic power, religious landscape, and social structure fostered an art market unlike any other in Europe. Civic institutions, like hospitals, orphanages, and various guilds, also emerged as significant patrons, commissioning large group portraits that celebrated communal achievements and identity. The absence of a dominant state-sponsored artistic academy meant that artists had greater freedom, but also faced intense competition in a highly commercialized environment.

Dutch Golden Age Society and Art Patronage Comparison

Feature | Dutch Republic (Protestant) | Other European Countries (Catholic) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Patrons | Wealthy merchants, middle class burghers, civic institutions | Church, aristocracy, monarchy |

| Artistic Themes | Genre scenes, portraits, landscapes, still lifes, marine painting | Grand religious narratives, mythological scenes, royal portraits |

| Scale of Works | Generally smaller, suitable for domestic display | Often large-scale for churches, palaces, and public buildings |

| Purpose of Art | Decoration, status symbol, moral instruction, reflection of daily life | Religious devotion, propaganda, glorification of rulers and saints |

| Art Market | Open, competitive, market-driven with public auctions | Patron-driven, often through commissions with stable patronage |

| Artist Status | Craftsmen, entrepreneurs, often specialized | Court painters, often elevated social status |

The Rise of New Patrons

With less demand for large-scale religious commissions, artists found a new market among wealthy burghers who sought art for their homes. Imagine a successful merchant, perhaps a tulip trader, commissioning a lavish still life or a serene landscape to adorn his newly built canal house – this was the reality. This democratisation of art created a vibrant, competitive environment where artists specialised in particular genres, leading to an incredible output of high-quality work. This period essentially created the modern art market, driven by supply and demand rather than top-down patronage. Artists often specialised in particular genres, becoming adept at specific subjects to meet the demands of an increasingly sophisticated and diverse clientele. This specialisation further drove the quality and variety of Dutch Golden Age art, making it accessible to a broader segment of society, a revolutionary concept at the time.

Masters of Light and Everyday Life

While Rembrandt excelled in dramatic narratives and profound portraiture, other masters captured the essence of Dutch life with distinct styles and thematic focuses. The period fostered an environment where individual artistic voices could flourish, leading to a rich tapestry of artistic expressions. It was a time when painters didn't just reproduce reality, but interpreted it, infusing scenes of daily life with profound observation and often, subtle moral messages.

Judith Leyster: The Independent Female Master

Judith Leyster (1609-1660) from Haarlem stands as a significant, though often historically overlooked, female artist of the Golden Age. A contemporary and likely rival of Frans Hals, she was one of only a few women admitted to the Haarlem painters' guild and ran her own successful workshop. Leyster excelled in genre scenes and portraits, often depicting lively musicians, merry companies, and quiet domestic moments with a distinctive, spirited brushwork and a keen sense of light. Her work, exemplified by "The Carousing Couple" or "The Last Drop," shares similarities with Hals's vivacious style but often introduces a more intimate and contemplative mood, sometimes imbued with moralizing undertones. Her ability to capture a sense of immediacy and human warmth, particularly in her children's portraits and genre scenes, marks her as an artist of exceptional talent and independence, a trailblazer in a male-dominated field.

Johannes Vermeer: The Enigmatic Master of Domesticity

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) is arguably the most famous artist to emerge from Rembrandt's shadow, celebrated for his serene and exquisitely rendered genre scenes. His works, often depicting solitary women engaged in quiet domestic tasks or musical pursuits, are characterised by their masterful use of light, precise compositions, and an almost photographic realism. Vermeer's sparse output and meticulous technique make each of his surviving works a treasure.

Consider his ability to infuse everyday moments with a profound sense of dignity and mystery, making us ponder the inner lives of his subjects. His use of light, often entering from a window on the left, became his signature, bathing his interiors in a soft, ethereal glow. Works like "Girl with a Pearl Earring" (c. 1665) and "The Milkmaid" (c. 1658) exemplify his unparalleled ability to render texture, light, and atmosphere, transforming mundane scenes into timeless masterpieces. Vermeer's connection to Delft, his native city, is also crucial, as his serene interiors often evoke a sense of the quiet, orderly life of the Dutch bourgeoisie. His meticulous technique and almost spiritual rendering of light have captivated audiences for centuries, influencing artists far beyond the Golden Age.

Frans Hals: The Master of the Spontaneous Brushstroke

Frans Hals (c. 1582-1666) from Haarlem stands in stark contrast to Vermeer's quietude. Hals was a brilliant portraitist, known for his lively, almost audacious brushwork that conveyed a sense of immediacy and vitality. His portraits, whether of individual citizens or large civic guard companies, capture the fleeting expressions and individual personalities of his sitters with unparalleled psychological insight.

He avoided the rigid formality common in contemporary portraiture, instead creating dynamic compositions that make the subjects appear to be caught in a moment of conversation or laughter. His bold technique would later influence Impressionists centuries later. Hals's focus on capturing the dynamism of his sitters, from individual portraits to sprawling civic guard groups like "The Merry Company" (also known as "Banquet of the Officers of the St. George Civic Guard," c. 1616), revolutionized the art of portraiture in the Netherlands. These large-scale group portraits were highly significant, celebrating the collective identity and status of Haarlem's elite citizens. For more on the art of capturing human likeness, explore our definitive-guide-to-portraiture.

Jan Steen: The Humorous Storyteller

Jan Steen (c. 1626-1679) was the master of the genre scene, famed for his boisterous and often moralistic depictions of everyday life, particularly merry companies, family gatherings, and disorderly households. His paintings are rich in detail, humour, and symbolic meaning, often serving as visual parables about human folly.

Steen's ability to weave complex narratives into his scenes, replete with anecdotal details and expressive figures, offers a lively window into 17th-century Dutch society. Works like "The Feast of Saint Nicholas" (c. 1665-1668) perfectly encapsulate his boisterous and morally didactic style. The phrase "a Jan Steen household" even became a Dutch idiom for a chaotic or untidy home, a testament to the vivid and relatable nature of his depictions. His intricate compositions are often filled with symbolism, requiring careful observation to uncover the full extent of his moralizing messages. To understand more about this popular subject, see our article on What is genre painting: history and examples.

This painting by Nicolaes Maes, a student of Rembrandt, exemplifies the genre painting popular during the Dutch Golden Age, focusing on domestic life and often imbued with moral or religious sentiment. His work showcases the stylistic diversity even within Rembrandt's circle. The emphasis on everyday life scenes and the increasing demand for art led to a flourishing of diverse artistic specialties, moving beyond the grand narratives of earlier periods to capture the world as it was observed.

Diverse Genres of the Golden Age

Beyond the celebrated individual artists, the Dutch Golden Age saw the flourishing of specialised genres, each revealing a unique aspect of Dutch culture and artistic skill and often attracting dedicated masters who refined their chosen subject. This specialization was a direct response to the market demands of a burgeoning middle class, eager to decorate their homes with art that resonated with their daily lives, values, and national pride.

Aelbert Cuyp: The Master of Golden Light and Pastoral Landscapes

Aelbert Cuyp (1620-1691) from Dordrecht is celebrated for his serene and luminous landscapes, often bathed in a warm, golden light that became his signature. His pastoral scenes, frequently featuring tranquil rivers, cattle, and distant cities or figures, evoke a profound sense of peace and natural grandeur. Cuyp's masterful handling of atmospheric perspective and his ability to capture the specific quality of light at dawn or dusk, often featuring backlighting that silhouettes figures and animals, set him apart. His influences often came from Italianate landscape painters, but he uniquely applied this luminosity to the distinctly Dutch countryside, as seen in "Maas at Dordrecht" (c. 1650), making his works particularly sought after by later generations.

The Golden Age saw the flourishing of specialised genres, each revealing a unique aspect of Dutch culture and artistic skill.

Landscape Painting

Dutch landscape artists moved beyond mere topographical representation to capture the mood and vastness of their flat, often watery homeland. Artists like Jacob van Ruisdael (1628-1682) created dramatic and evocative landscapes, featuring stormy skies, powerful trees, and subtle light effects. His works are often imbued with a sense of melancholic grandeur, reflecting a deep connection to nature, as exemplified in his powerful "The Jewish Cemetery." His uncle, Salomon van Ruysdael (c. 1602-1670), often depicted more tranquil river views and ferries, contributing to the development of the "monochromatic" landscape style, using subtle tonal variations to create depth and atmosphere. Other notable landscape artists include Meindert Hobbema (1638-1709), known for his detailed and realistic depictions of wooded landscapes and watermills, and the "Italianate" landscape painters like Jan Both, who introduced a warmer, more idealized Mediterranean light into Dutch scenes. The variety ranged from dramatic mountainscapes (often imagined) to serene river vistas and bustling winter scenes, each offering a unique perspective on the natural world and the human interaction with it. These landscapes often carried symbolic weight, reflecting national pride in the reclaimed land and the harsh beauty of the Dutch environment.

Still Life

Still life paintings, ranging from opulent pronkstillevens (sumptuous still lifes) to humble ontbijtjes (breakfast pieces), were immensely popular and offered artists a chance to display incredible technical skill. Artists like Willem Kalf (1619-1693), famed for his luxurious compositions, and Willem Claesz. Heda (1596-1680), known for his monochromatic "breakfast pieces," alongside Pieter Claesz (c. 1597-1660), mastered the depiction of textures – gleaming metals, shimmering glass, and ripe fruit. These works often incorporated vanitas symbols that reminded viewers of the transience of life, such as wilting flowers, skulls, overturned goblets, or extinguished candles. This genre allowed for both dazzling displays of wealth and profound contemplation on mortality, a subtle yet powerful moral message embedded within exquisite realism.

A notable female artist in this field was Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750). For a deeper understanding of this rich art form, delve into the history-of-still-life-painting.

Flower Painting: A Vibrant Specialization

Within the broader genre of still life, flower painting blossomed into a highly specialized and celebrated art form during the Dutch Golden Age. Artists like Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), mentioned above, and Jan van Huysum (1682–1749) achieved international fame for their breathtakingly intricate and scientifically accurate floral arrangements. These paintings were more than just beautiful decorations; they were botanical marvels, often featuring flowers from different seasons depicted together, a testament to artistic imagination and the careful study of nature. They frequently incorporated subtle symbolism, reminding viewers of beauty's ephemeral nature and the passage of time. The sheer detail and vibrant color in these works are astounding, almost asking you to lean in and smell the blossoms.

Marine Painting

Given the Netherlands' existential reliance on the sea for trade, defence, and exploration, marine painting was a vital and highly patriotic genre. Artists like Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633-1707), often working alongside his father Willem van de Velde the Elder, depicted naval battles, calm seascapes, and bustling harbours with incredible detail and atmospheric effect, celebrating Dutch maritime power and its crucial role in the nation's prosperity. Other notable marine painters include Jan Porcellis (c. 1584-1632) and Simon de Vlieger (c. 1601-1653), who masterfully captured the dramatic shifts in light and weather over the North Sea. These paintings not only served as decorative pieces but also as historical records and symbols of national pride, showcasing the Dutch mastery of the seas and their advancements in cartography and scientific exploration, which were often intertwined with maritime ventures.

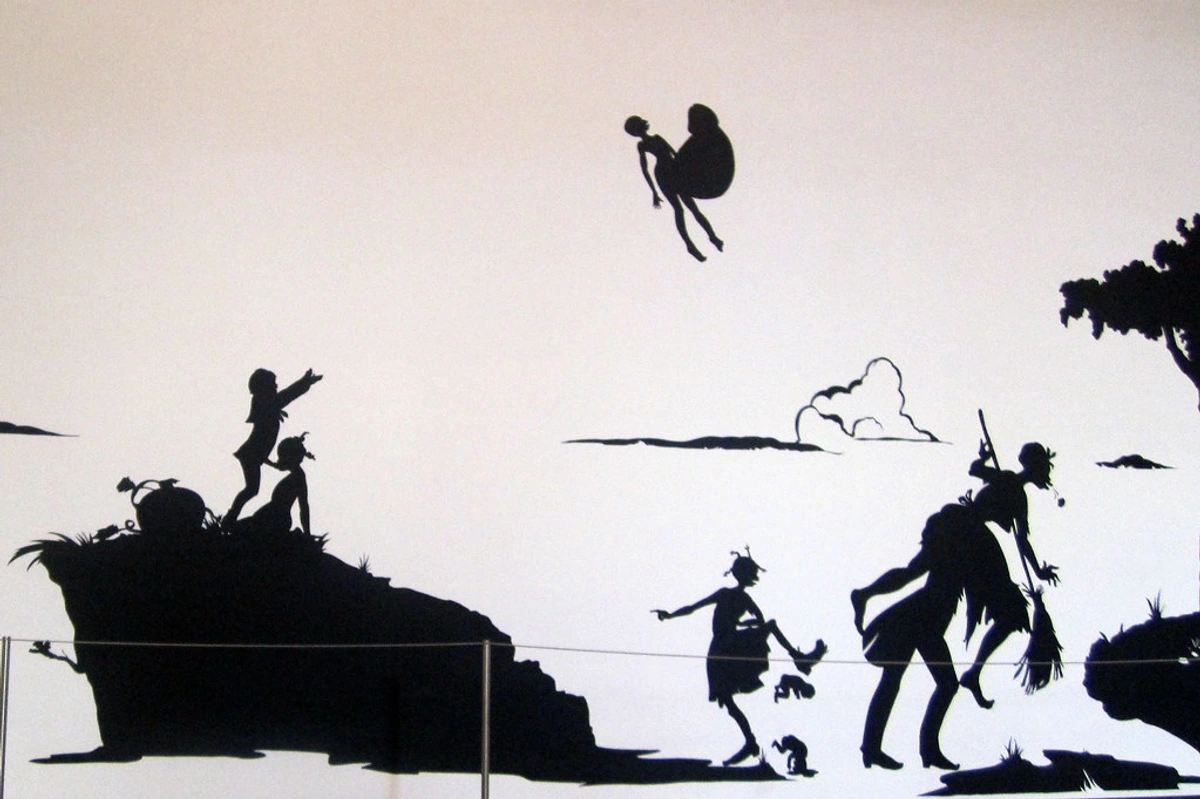

History Painting

While genre scenes, portraits, and landscapes gained immense popularity, History Painting—encompassing biblical, mythological, and historical narratives—was still considered the most prestigious genre. Artists often sought to demonstrate their academic training and ability to convey complex narratives and human emotion. Masters like Carel Fabritius (a brilliant student of Rembrandt, known for "The Goldfinch") and Ferdinand Bol excelled in this field, often drawing inspiration from classical antiquity and religious texts to create compelling and dramatic compositions. The Utrecht Caravaggists, including Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656), also brought a dramatic chiaroscuro and intense realism to history painting, influenced by Italian Baroque masters. These works served to educate, inspire, and often to reinforce moral virtues, providing lessons from history and scripture that resonated with the populace.

Architectural Painting

Another highly specialised genre was architectural painting, where artists focused on depicting church interiors or imaginary buildings with astounding precision and linear perspective. Pieter Saenredam (1597-1665) is a prime example, known for his meticulously rendered, often stark church interiors that convey a sense of quiet reverence. His precise linear perspective and cool, subdued palette highlight the grandeur and geometric harmony of the buildings, often focusing on the structural elements rather than anecdotal details. Other artists, like Emanuel de Witte, captured church interiors with a more active, genre-like quality, often including figures and emphasizing the play of light and shadow. The technical skill required for such precise renderings, particularly in mastering one-point perspective, was immense, often involving careful measurements and preparatory drawings.

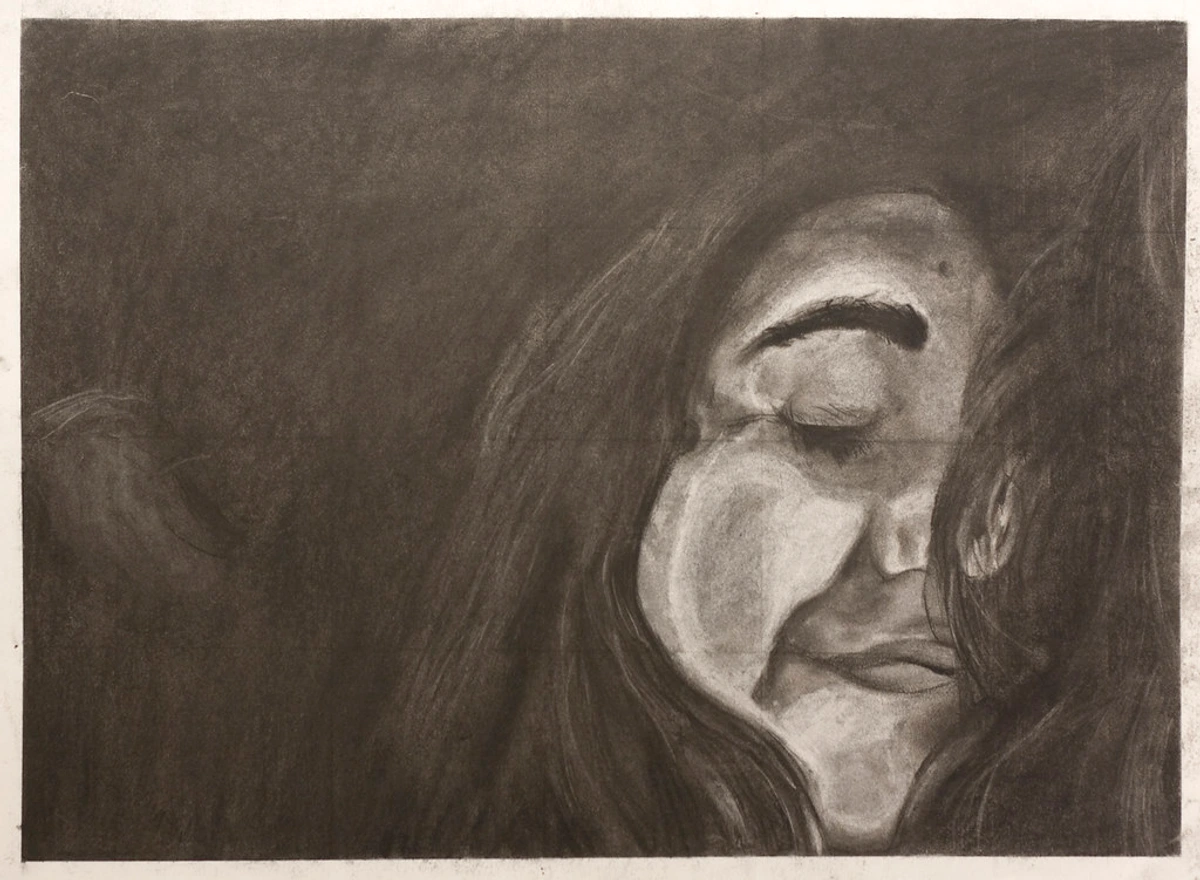

Tronje: The Character Study

A fascinating sub-genre that emerged during the Golden Age was the tronje (plural: tronjes). These were not traditional portraits of specific, identifiable individuals but rather studies of facial expressions, exotic costumes, or intriguing character types. Often depicting ordinary people, soldiers, or figures in unusual garb, tronjes allowed artists to experiment with light, shadow, and vivid expression. Rembrandt himself painted many famous tronjes, such as "Self-Portrait with Two Circles" (c. 1665-1669) or "Man in Oriental Costume" (c. 1635), exploring the depths of human character and emotion. Frans Hals also contributed to this genre with his lively character studies. These works served as both artistic exercises, allowing painters to hone their skills in capturing fleeting expressions and dramatic lighting, and highly collectible pieces, valued for their dramatic intensity and technical brilliance. Pieter Saenredam (1597-1665) is a prime example, known for his meticulously rendered, often stark church interiors that convey a sense of quiet reverence. His precise linear perspective and cool, subdued palette highlight the grandeur and geometric harmony of the buildings, often focusing on the structural elements rather than anecdotal details. Other artists, like Emanuel de Witte, captured church interiors with a more active, genre-like quality, often including figures and emphasizing the play of light and shadow.

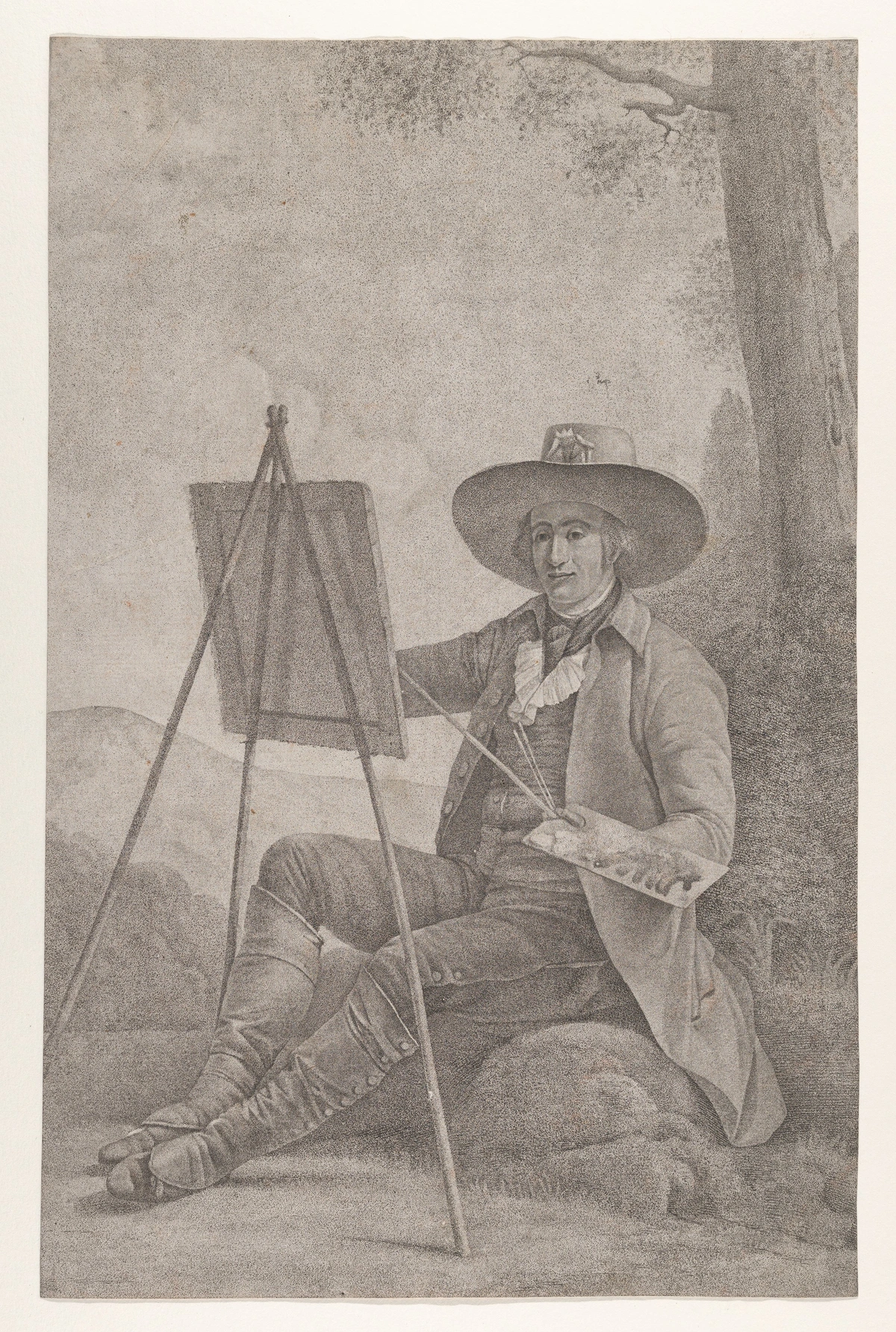

The Workshop System and Artistic Training

The success of the Dutch Golden Age art market fostered a robust workshop system, which was the primary mode of artistic training and production. Young aspiring artists, often starting around age 10-14, would enter an apprenticeship, typically for 4-6 years, under an established master. During this period, they learned fundamental skills like drawing from plaster casts and prints, preparing pigments and canvases, mastering painting techniques, and understanding the intricate business of art. This system was strictly governed by city guilds, such as the prominent Guild of Saint Luke in Delft or Amsterdam, which regulated the training of apprentices, the practice of master painters, and the sale of art. These guilds played a crucial role in maintaining artistic standards and protecting local markets, acting as both a professional body and a quality control mechanism.

Young aspiring artists, such as Govert Flinck (1615-1660) and Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), trained under established masters like Rembrandt, learning techniques and developing their own styles. Many of these students went on to have significant careers, often developing distinctive individual styles while still bearing the mark of their master's influence, further enriching the artistic landscape and contributing to the era's prolific output. The workshop acted as both a school and a studio, ensuring a continuous supply of skilled artists and fostering vibrant artistic communities where ideas and techniques were constantly exchanged.

Rembrandt's Enduring Influence

While this article champions the breadth of the Dutch Golden Age, it is impossible to overlook the monumental figure of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). His profound psychological insight, revolutionary use of chiaroscuro (the strong contrast between light and dark), and textured brushwork set him apart. His influence extended not only through his direct students, but also by shaping the very trajectory of European art. His capacity to convey deep human emotion and spiritual intensity in his portraits, historical scenes, and self-portraits remains unparalleled. Exploring his works, such as the iconic "The Night Watch" (1642), is crucial to understanding the era's artistic pinnacle. For a deeper dive into his unparalleled artistry, explore our ultimate-guide-to-rembrandt-van-rijn.

The Enduring Legacy

The innovations of the Dutch Golden Age artists left an indelible mark on Western art. Their focus on realism, masterful handling of light, and the dignity of everyday life paved the way for future movements. The emphasis on individual expression and the depiction of ordinary subjects directly foreshadowed the Realists of the 19th century, and their bold brushwork and study of light deeply influenced the Impressionists. This period also refined concepts of composition and perspective, establishing foundational principles that would guide artists for centuries. Furthermore, the commercial success and structure of the Dutch art market fundamentally influenced the development of art as a commodity and the concept of the artist as an independent entrepreneur, shaping aspects of art education and patronage for generations. The sheer volume and quality of work from this period continue to captivate audiences worldwide, solidifying its place as one of the most vibrant and influential chapters in art history. For a look at how other historical movements shaped art, see our ultimate-guide-to-baroque-art-movement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dutch Golden Age Art

To further illuminate this fascinating period, here are answers to common questions:

Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What characterized Dutch Golden Age art? | Dutch Golden Age art was characterized by its diversity in genre (portraits, genre scenes, landscapes, still lifes, marine paintings), a focus on realism, masterful use of light (chiaroscuro, subtle domestic light), detailed brushwork, and a shift from religious patronage to a strong bourgeois market, reflecting daily life and secular values. |

| Who were the most famous artists of the Dutch Golden Age besides Rembrandt? | Beyond Rembrandt van Rijn, key figures include Johannes Vermeer, Frans Hals, Jan Steen, Jacob van Ruisdael, Pieter de Hooch, Aelbert Cuyp, Judith Leyster, and Willem Kalf. Each contributed significantly to distinct genres and styles. |

| What subjects were popular in Dutch Golden Age painting? | Popular subjects included intimate genre scenes depicting domestic life, lively tavern scenes, formal and informal portraits (both individual and group), vast landscapes (including seascapes and cityscapes), intricate still lifes (often with moral undertones or 'vanitas' elements), and historical or biblical narratives. |

| Why is it called the 'Golden Age'? | The term 'Golden Age' refers to a period of exceptional economic prosperity, cultural flourishing, and political dominance for the Dutch Republic, roughly the 17th century. This era saw remarkable achievements in trade, science, military power, and particularly the arts. |

| How did patronage differ in the Dutch Golden Age compared to other European countries? | In most Catholic European countries, the Church and aristocracy were the primary patrons, commissioning large religious works or grand portraits. In the Protestant Dutch Republic, a wealthy merchant class and burgeoning middle class became the main patrons, leading to a demand for smaller, more domestic art reflecting everyday life and secular themes, as well as civic group portraits. |

| What was the Guild of Saint Luke? | The Guild of Saint Luke was the most common name for a city guild for painters and other artists in early modern Europe, particularly in the Low Countries. It regulated the training of apprentices, the practice of master painters, and the sale of artworks, playing a crucial role in maintaining artistic standards and market structure. |

| Were there prominent female artists in the Dutch Golden Age? | Yes, though fewer in number than male artists, notable female artists achieved significant recognition. Key examples include Judith Leyster, a master of genre scenes and portraits, and Rachel Ruysch, highly celebrated for her intricate and scientifically accurate still life flower paintings. |

| What is a 'Tronje' in Dutch Golden Age art? | A 'tronje' is a specific type of character study or head study that depicts an anonymous model, often with exaggerated expressions or in exotic costume. Unlike a formal portrait, a tronje focuses on the artistic exploration of human character, emotion, and physiognomy, allowing artists to experiment with light, shadow, and vivid brushwork. Rembrandt painted many notable examples. |

| How did scientific advancements influence Dutch Golden Age art? | The era's scientific advancements, particularly in optics and anatomy, significantly influenced Dutch Golden Age art. Artists often employed principles of linear perspective, understood light and shadow with increasing sophistication, and demonstrated accurate anatomical rendering in figures. The invention of the camera obscura, for instance, is believed to have influenced artists like Vermeer in achieving their precise and luminous compositions. |

| What was the role of the Guild of Saint Luke? | The Guild of Saint Luke was the most common name for a city guild for painters and other artists in early modern Europe, particularly in the Low Countries. It regulated the training of apprentices, the practice of master painters, and the sale of artworks, playing a crucial role in maintaining artistic standards and market structure. |

| What kind of light is characteristic of Dutch Golden Age painting? | Dutch Golden Age painting is renowned for its masterful depiction of light, which varies significantly by artist and genre. This includes the dramatic chiaroscuro of Rembrandt, the soft, ethereal domestic light of Vermeer, the luminous golden light in Cuyp's landscapes, and the crisp, clear light of architectural interiors by Saenredam. It's less about a single type of light and more about an unparalleled sensitivity to its effects. |

| Did the Dutch Golden Age influence later art movements? | Absolutely. Its focus on realism, everyday life, and secular themes directly impacted 19th-century Realism. The dynamic brushwork of artists like Frans Hals and Rembrandt prefigured Impressionism, while the sophisticated handling of light and composition continued to inspire artists for centuries, establishing foundational principles in Western art. |

| Where can one see Dutch Golden Age art today? | Major collections of Dutch Golden Age art can be found in the Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam), Mauritshuis (The Hague), Frans Hals Museum (Haarlem), and museums worldwide such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the National Gallery (London), and the Louvre (Paris). |

Conclusion

The Dutch Golden Age stands as a testament to unparalleled artistic innovation and cultural dynamism. While Rembrandt's name rightly commands profound respect and admiration, the period's true richness lies in the collective brilliance of a multitude of artists who explored every facet of human experience and the natural world with fresh eyes and innovative techniques. From Vermeer's quiet domesticity to Hals's vibrant portraits, Steen's lively narratives, and the serene landscapes of Cuyp, these masters collectively forged an artistic legacy that continues to resonate with powerful realism and enduring beauty. They invite viewers to immerse themselves in a world that extends far beyond the shadow of a single genius, revealing an entire epoch of artistic marvels, a true "golden age" that continues to inspire and instruct us in the power of observation and artistic expression. Discover more timeless art and perhaps even your next piece of inspiration at our online gallery.