Still Life Painting: My Artistic Journey, Dynamic History & Ultimate Guide

Embark on a personal journey through still life painting, from ancient symbolism to modern abstraction. Discover its dynamic history, profound meanings, and how this evolving genre inspires my vibrant abstract art practice. Your comprehensive guide awaits.

Still Life Painting: My Artistic Journey, Dynamic History & Ultimate Guide

I've got a confession to make. For the longest time, whenever someone mentioned “still life,” my mind immediately conjured images of dusty fruit bowls and wilting flowers. Pleasant enough, sure, but… still. The art equivalent of beige wallpaper, utterly forgettable, I used to think. It felt like art without a story, devoid of the human drama or grand landscapes I gravitated towards. I remember a particularly dreary art history lecture, where the professor droned on about a classical Dutch banquet scene, brimming with game and ornate goblets, which at the time just felt... heavy, static. That initial dismissal, viewing it as mere 'beige wallpaper,' ironically sparked a personal journey into the true, often surprisingly dynamic, history of still life painting, or as the Dutch so aptly call it, stilleven (meaning 'still life' or 'static model'). It wasn't a grand epiphany, but rather a slow, dawning realization as I peeled back the layers of history, discovering that this genre was a canvas for profound human stories and observations, a static model revealing dynamic truths across centuries and cultures. Perhaps I was too focused on the dramatic, the 'shouting' art, to appreciate the quiet power these objects held. It was a personal revelation, forcing me to confront my own biases and truly see what I had overlooked. This guide, blending personal reflection with historical insight, aims to be your ultimate resource for understanding this surprisingly dynamic story, uncovering the profound conversations these objects can hold across centuries and cultures, just as I did.

This personal excavation revealed a genre far richer and more dynamic than I'd ever imagined. I'm excited to share that journey with you, revealing artistic insights and reflections woven throughout centuries. So, grab a coffee, and let's unravel this surprisingly dynamic story together.

Artist's Workspace Photo, Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication

The Seeds of Stillness: Ancient Roots

So, still life didn’t just pop up out of nowhere. Its roots stretch way back, further than you might imagine, long before it was even a concept like we understand it today. For me, the immediate jump is always ancient Egypt, probably because those tomb paintings of feasts and offerings were some of the first art I ever truly saw and understood – a visceral connection to the past, even then. Images of food and everyday objects like bread, fruit, and finely crafted tools weren't just decorative; they were essential, ensuring eternal prosperity, sustenance, and magically appeasing deities for the deceased in the afterlife, almost like a spiritual provisioning list.

But even before that, in ancient Mesopotamia, we find early depictions of natural forms and vessels, often carved reliefs or painted pottery depicting things like harvested crops, animals destined for sacrifice, or vessels for libations to appease deities. These weren't just pretty pictures; the depictions themselves were vital tools in rituals, meant to ensure bountiful harvests, represent fertility, or even serve as records of abundance for future generations. This foundational practice of imbuing objects with symbolic, ritualistic power has echoed through the centuries, subtly influencing later artists who sought to convey deeper meanings through their arrangements of inanimate forms. It wasn’t "art for art's sake," but rather art serving a very practical, spiritual, and sometimes administrative purpose. A bit like packing for a very, very long trip, only for the afterlife, and with more artistic flair.

Then you had the Greeks and Romans. They were pretty keen on everyday objects too, often depicting them in frescoes and mosaics. Remember the Roman concept of Xenia? It was all about hospitality, offering gifts to guests, a fundamental code of reciprocal hospitality and a sacred duty to welcome strangers. To me, this resonates with the artist's role – offering a visual 'gift' to the viewer, a carefully prepared still life scene meant to invite contemplation and connection. So, these painted feasts weren't merely decoration; they were visual promises, an extension of that ingrained cultural value, signalling warmth and welcome, with carefully arranged food and drink symbolizing the bounty awaiting visitors. Before the Romans, the Etruscans also showed a remarkable sensitivity to the material world, with tomb frescoes depicting elaborate banquets, luxury goods, and everyday objects, reflecting their appreciation for life's earthly pleasures and ensuring comfort in the afterlife – a fascinating precursor to Roman opulence.

And let's not forget the incredible skill of things like trompe l'oeil, where objects were painted with such realism they seemed to pop right off the wall. Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian, even recounted tales of ancient Greek painters like Zeuxis, whose painted grapes were so realistic birds tried to peck at them. Imagine a fresco depicting a cracked wall, or a dog straining at its leash, so convincing you'd reach out to touch it. I remember standing before a particularly convincing trompe l'oeil fresco in Pompeii, feeling that delightful jolt of confusion – a testament to humanity’s age-old desire to blur the lines between art and reality, and a trick I sometimes play with perspective in my own works, though perhaps with less ancient grandeur! This mastery of illusionism, while not yet a genre in itself, was crucial because it demonstrated the immense power of paint to convincingly mimic reality, laying foundational groundwork for the hyperrealism that would later define still life painting, pushing the boundaries of what paint could achieve.

Moving into the Medieval period, the focus shifted dramatically. Art was almost exclusively religious, and objects in paintings served a higher purpose, dictated by the pervasive influence of the Church. The art wasn't just decorative; it was didactic – meaning it was intended to teach biblical stories and moral lessons to a largely illiterate populace, reinforcing doctrine and spiritual authority. For instance, you might spot a single lily, symbolizing the purity of the Virgin, or a scattered book, representing divine knowledge. In a masterpiece like Jan van Eyck's Annunciation, the single lily in a vase on the floor isn't just a decorative element; it's a potent symbol of purity, its presence integral to the divine message. Lilies often spoke of purity, while grapes alluded to the Eucharist. A dog might symbolize loyalty, or a peacock, immortality. Every object had a message, carefully placed to guide the viewer towards spiritual contemplation, often found in the intricate marginalia of illuminated manuscripts or subtle details of altarpieces. Still life elements were there, but always in service of a grander, divine narrative, acting as visual sermons. It reminds me a bit of how we might secretly assign special meaning to a mundane object in our home – a worn teacup from a grandparent, for example – knowing its true significance even if no one else does. This personal meaning-making is, in a way, an ancestor to the symbolic language still life would later develop, where objects were imbued with universally understood meanings. However, as the Middle Ages drew to a close and a new intellectual curiosity dawned, this 'silent narrative' of objects, conveying profound truths without a human figure, began to shift its focus from the purely divine to an emerging interest in the material world. Objects were slowly preparing for a grander entrance, moving beyond mere supporting roles to demand their own spotlight on the artistic stage.

What echoes of these ancient practices do you still see in how we arrange objects today?

Renaissance Foundations: Objects Find Their Voice

As the world began to reawaken after the Middle Ages, so too did the appreciation for the tangible world, paving the way for objects to step out of the shadows and into the Renaissance spotlight. Artists began to look at the world around them with fresh eyes, slowly shifting from purely divine narratives to a burgeoning interest in the secular. The era's burgeoning scientific inquiry, alongside detailed botanical illustrations and anatomical studies, fostered an unprecedented naturalism in art. Think of breakthroughs in optics, or early observations through nascent microscopes – these pushed artists to see and depict with unparalleled accuracy.

Crucially, the development and refinement of oil painting techniques during this era played a pivotal role, allowing for unprecedented detail, rich textures, luminous glazes, and subtle plays of light and shadow. These qualities were perfect for capturing the minute realities of objects with breathtaking realism. As someone who's wrestled with the nuances of different mediums, I can tell you that oil's capacity for layering and luminosity is a true game-changer. I still chase that rich, deep color and illusion of tangible texture in my own abstract explorations, often using layered glazes to achieve a similar internal glow, much like the Renaissance masters. I often think back to my initial dismissal of still life as 'beige wallpaper,' and chuckle at how much I simply wasn't seeing then, much like a novice artist overlooking the subtle magic in a simple pigment. These advancements in observation and technique provided the perfect toolkit for artists to begin exploring the tangible world with unprecedented fidelity, paving the way for still life to emerge as a distinct artistic pursuit.

Historically, art operated under a strict artistic hierarchy, where grand narratives like history paintings and religious scenes sat at the top, followed by portraiture, then genre scenes, landscapes, and finally, still life. Challenging this hierarchy, 'cabinets of curiosities,' filled with natural specimens (like exotic shells or fossils), exotic artifacts, and scientific instruments, were essentially early, curated still lifes themselves, reflecting a burgeoning scientific curiosity and a growing fascination with the material world. They subtly demonstrated the intrinsic worth of the inanimate, advocating for its artistic value beyond mere supporting roles and paving the way for still life to truly flourish as an independent genre.

In the early Renaissance, objects in religious paintings started to gain more prominence, not just as symbols, but for their intrinsic beauty and realistic rendering. Think of the glistening pearls, the richly embroidered fabrics, or the incredibly detailed tools in a workshop setting within works by Flemish masters like Jan van Eyck or Robert Campin. The shimmering gold of a chalice or the precise folds of a velvet cloak weren't just background filler; they spoke of wealth, status, and an almost divine order, but also of the sheer mastery of rendering texture and light. It’s like a supporting actor finally getting their well-deserved close-up, and honestly, the audience loved it. This newfound appreciation for the detailed depiction of objects, and the evolving worldview of the Renaissance—fueled also by a growing interest in collecting natural specimens and curiosities in 'cabinets of curiosities'—would lay crucial groundwork for still life to truly flourish as an independent genre in the centuries to come.

Still life with flowers, Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0

What seeds of future artistic revolutions do you think were being sown in these meticulously rendered objects?

The Golden Age of Dutch Still Life: When Objects Took Center Stage

So, are you ready for the main event? Ah, the 17th century! This is where still life really exploded, especially in the Netherlands. I mean, these guys went all in! It became a genre in its own right, no longer just a backdrop or an accessory, but a highly sought-after commodity in a booming art market. The Dutch Republic was experiencing unprecedented economic growth, fueled by trade and a burgeoning merchant class. Unlike countries dominated by the Church or monarchy, there was a vast, wealthy middle class eager to decorate their homes with art that reflected their prosperity and values, free from overtly religious or mythological narratives. Still life, visually appealing, technically brilliant, and often infused with subtle moral reminders, was the perfect fit. This period also saw the burgeoning Scientific Revolution, with a keen interest in empirical observation and the cataloging of the natural world. This scientific curiosity directly fueled the meticulous botanical accuracy in flower pieces and the detailed rendering of insects, shells, and exotic imports in many still lifes, intertwining art with emerging scientific thought and fostering a sense of wonder in viewers. The Republic's vast trade networks also brought exotic goods from afar – spices, rare fruits, and shells – which found their way into these opulent arrangements, reflecting both wealth and a burgeoning global awareness. This led to a rich diversity of still life types. I love this period because it’s so rich with detail and hidden narratives. It also significantly influenced still life practices across other European countries, though perhaps never with the same independent dominance as in the Netherlands. Still life truly became a mirror of society, reflecting the values, anxieties, and aspirations of the era.

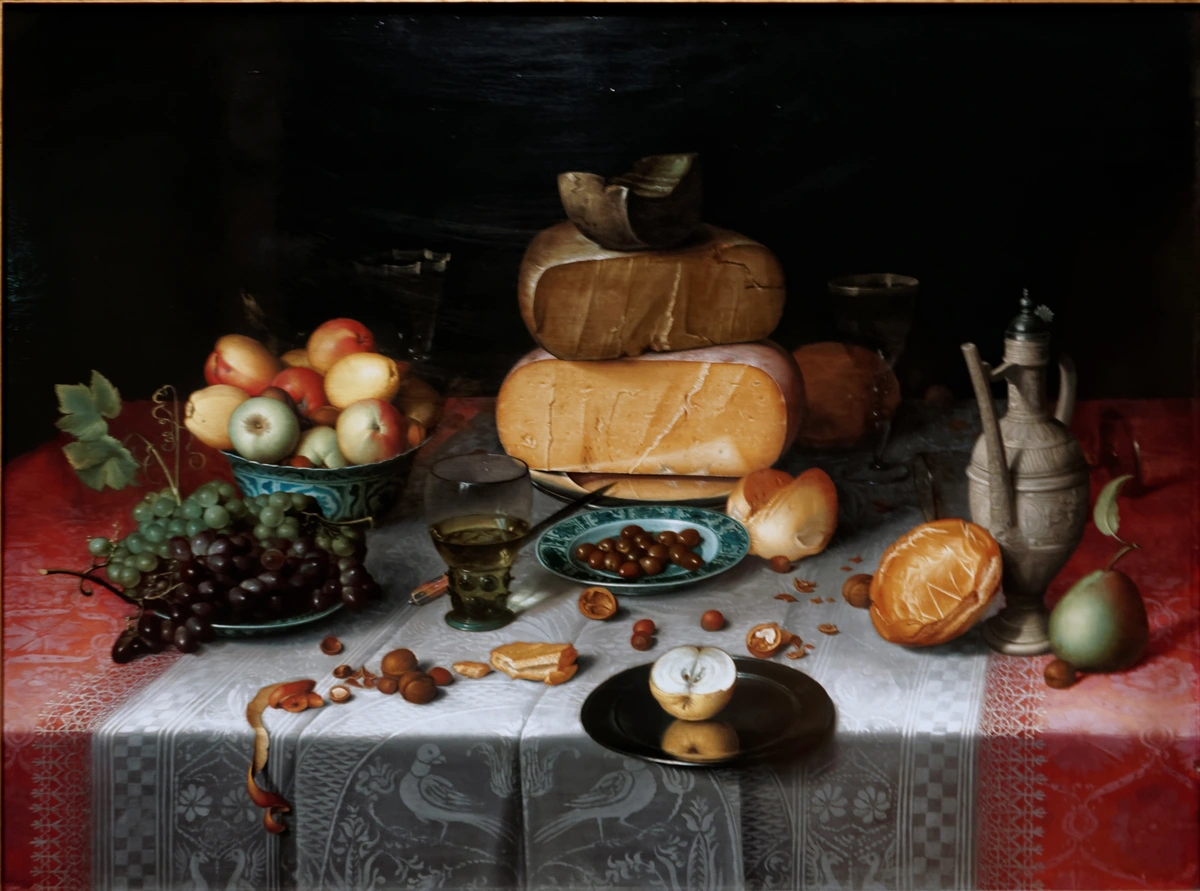

Dutch Golden Age Still Life, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Here's a quick overview of some prominent Dutch still life categories:

Type of Still Life | Description | Common Elements & Artists |

|---|---|---|

| Flower Pieces | Lavish displays of bouquets, celebrating beauty and often symbolizing transience, specific virtues, or the cycle of life. These were particularly popular as displays of wealth and the exotic trade goods available to the Dutch Republic. | Exotic flowers, insects, dewdrops. Artists: Rachel Ruysch, Jan van Huysum |

| Breakfast Pieces (Ontbijtjes) | Modest depictions of simple spreads, emphasizing everyday abundance, domestic virtue, and the quiet comfort of home. Often with subtle moralizing undertones, appealing to the growing middle class. | Bread, cheese, wine, simple utensils. Artists: Willem Claesz. Heda, Pieter Claesz, Clara Peeters |

| Banquet Pieces (Banketjes) | More elaborate arrangements of food and drink, showcasing luxury, culinary skill, and often an overt display of social standing, sometimes with subtle warnings against excess or the fleeting nature of wealth. | Roasted meats, exotic fruits, opulent vessels. Artists: Abraham van Beyeren, Frans Snyders |

| Pronkstillevens | "Ostentatious still lifes" displaying expensive, exotic goods as a show of wealth, refined taste, and global reach. These were status symbols. | Silverware, imported fruits, elaborate glassware. Artists: Willem Kalf, Jan Davidsz. de Heem |

| Vanitas Still Lifes | Moralizing works explicitly illustrating the ultimate futility of earthly possessions and pleasures, reminding viewers of mortality and admonishing against worldly vanity. | Skulls, snuffed candles, wilting flowers, luxury items. Artists: Harmen Steenwyck, Pieter Claesz |

| Trompe l'oeil | "Deceive the eye" paintings that masterfully create the illusion of three-dimensional reality, making viewers question what is real and what is painted. A technical showcase. | Curtains, documents, everyday objects appearing to pop out. Artists: Samuel van Hoogstraten, Cornelis Gysbrechts |

This is where we get into the juicy bits like Vanitas and Memento Mori. I know, fancy Latin terms, but they’re pretty straightforward. This was a period marked by religious upheaval, scientific discovery challenging old beliefs, and the ever-present reality of plague and war. These paintings often carried profound moralizing messages, particularly in the Vanitas subgenre. While Memento Mori (Latin for "remember you must die") is a broader concept urging reflection on mortality – perhaps a skull on a tomb or a poignant epitaph – Vanitas (meaning "vanity" or "emptiness") is a specific visual argument within still life. It uses symbolic objects like skulls, snuffed candles, and wilting flowers, often juxtaposed with luxury items, to explicitly illustrate the ultimate futility and emptiness of earthly possessions and pleasures, admonishing against worldly vanity. Think of it this way: Memento Mori is a general nudge to remember mortality, like a skull carving on an old church. Vanitas, on the other hand, is a full-blown, symbolic sermon within a painting, explicitly warning against worldly attachments and often showcasing a lavish spread of goods you're meant to eventually lose.

A Pieter Claesz Vanitas Still Life might feature a skull, a snuffed-out candle, and wilting flowers – all stark reminders that life is short, and we’re all heading the same way. A real conversation starter, or perhaps a mood killer for a dinner party, but undeniably powerful. It's a powerful testament to the layers of meaning we can embed in art, and specifically, the enduring power of symbolism in art, a topic I find endlessly fascinating. Beyond Vanitas, other still lifes conveyed moral reminders about temperance, diligence, or the dangers of excess through their arrangements.

Alongside these profound messages, Dutch artists also celebrated everyday life, capturing opulent banquet tables, beautiful flowers, and exotic imports. It wasn’t all about death; sometimes, it was about showing off wealth and taste. And the technical skill involved? Mind-blowing. As someone who tries to capture the essence of things with my own brush, I still marvel at the precision and realism. The way they rendered textures – the gleam of metal, the fuzz of a peach, the delicate transparency of a glass – it’s just incredible. I still think, 'How did they do that?' This mastery of light, even in humble objects, is something I strive to capture in my own abstract pieces, albeit with a different palette. For me, it's not about replicating realism, but about distilling that luminous quality, that interplay of light and shadow, into pure color and form through layered glazes. It pushes me to think about my own craft, even if my results are wildly different. What does this duality of earthly pleasure and mortality tell us about the human condition, then and now?

Shifting Tides: 18th & 19th Centuries – Evolving Perspectives

After the glorious peak of the Dutch Golden Age, still life didn't fade away; it continued its remarkable evolution, proving it was anything but 'still', adapting to new artistic philosophies and societal shifts. While the 18th century often leaned towards lighter, more decorative Rococo styles, with their playful charm and ornate details, artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin anchored still life back to earth with his profoundly beautiful depictions of humble kitchen objects. His canvases glow with an inner light, making a simple copper pot, a jar of olives, or a half-peeled turnip feel monumental, almost spiritual. He achieved this through his masterful use of subtle tonal gradations, soft brushwork, and a quiet dignity that elevated the domestic and the ordinary to subjects of serious artistic contemplation. Think of his masterpiece, 'The Rayfish', where a grotesque sea creature is rendered with such a luminous, almost spiritual quality, transforming the macabre into something profoundly beautiful. He captured the tactile quality of surfaces, the profound beauty hidden in the everyday, inviting viewers to slow down and truly see. Sometimes, the simplest things are the most profound, wouldn't you agree? I find myself often pausing in my studio, not at a grand canvas, but at the way light falls on a simple coffee mug, finding a similar quiet dignity in its form, inspiring me to distill that luminous quality into my abstract work. Interestingly, even as avant-garde movements began to challenge traditional art, still life maintained a strong presence in academic circles and salons, valued for its rigorous training potential in composition, observational skills, and realism.

Still Life with Rayfish, Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication

Neoclassicism, too, brought a restrained elegance to still life, with crisp, clear lines, balanced compositions, and idealized forms – often featuring classical motifs like urns, busts, or laurel wreaths – reflecting an age that valued reason, order, and a return to Enlightenment ideals. The 19th century brought us Impressionism, and still life, naturally, got a makeover. Artists like Paul Cézanne, often considered the father of modern art, used still life to explore form, color, and perspective in revolutionary ways. His apples aren't just apples; they're studies in geometry, light, and how our eyes perceive things from multiple angles. He meticulously focused on fundamental geometric forms like spheres, cones, and cylinders, breaking down objects into these basic elements. This breaking down of form wasn't just aesthetic; it was an intellectual quest to capture the essence of perception itself, a bit like watching a scientist dissecting the very idea of vision, but with paint and apples instead of scalpels. Cézanne’s meticulous explorations of geometric forms and shifting viewpoints in his still lifes were a direct precursor, a vital stepping stone, to the revolutionary ideas that would soon define Cubism, directly inspiring artists like Picasso and Braque to shatter and reassemble objects on canvas. Simultaneously, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England, in their quest for truth to nature, incorporated meticulously rendered still life elements into their allegorical and narrative paintings, often with symbolic significance such as lilies for purity or hourglasses for fleeting time. Their almost hyper-realistic approach to details served their commitment to realism and vivid storytelling, often imbued with moral allegories and religious symbolism, providing a fascinating counterpoint to the emerging Impressionist dissolution of form. And speaking of new ways of seeing...

Modernism: Still Life Reimagined

This is where things get really exciting for me, probably because it starts hinting at the abstract art I love so much. Modern artists didn’t just paint what they saw; they painted what they felt or what they thought about what they saw. Still life became a playground for experimentation, pushing boundaries in radical ways – challenging traditional representation of form, color, perspective, and even the very definition of what an object could represent. This period saw a dismantling of traditional representation that paved the way for full abstraction.

Neo-Impressionist painting by Maximilien Luce depicting a still life with oranges and other fruits on a table with textured brushstrokes in warm and cool tones, Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0

Before diving into the full abstraction, the Symbolist movement also utilized still life, but not for its visual accuracy. For Symbolists, objects were evocative vessels, imbued with psychological or mystical meanings, stirring emotions and subconscious associations rather than merely depicting reality. Think of Odilon Redon’s ethereal arrangements, like a single, unsettling eye floating in a landscape or a vase of poppies that seem to weep, prompting introspection rather than observation, or the evocative objects in a Gustave Moreau painting, loaded with hidden emotional weight and often hinting at dreams or the supernatural. This paved the way for more radical departures. Even a lesser-known but vibrant movement like Orphism, with artists like Robert Delaunay, used still life elements like musical instruments as a starting point to explore pure color, light, and abstract forms, creating a dynamic, almost musical rhythm that anticipates later abstract movements. In Futurism, objects were fragmented, shattered, and depicted with multiple outlines, conveying movement and speed, reflecting the era's fascination with technology and urban life. Imagine Umberto Boccioni’s Still Life with Bottle and Glasses where static objects seem to burst with dynamic energy, or a violin exploding into a series of overlapping planes, each capturing a different moment in time or angle of observation. It wasn't just about seeing; it was about experiencing the dynamism and exhilarating chaos of the modern world, the energy of movement itself. Surrealists, on the other hand, used still life to create dreamlike and unsettling arrangements of everyday items, challenging perception and delving into the subconscious. Artists like Meret Oppenheim created unsettling, tactile still lifes, like her fur-lined teacup, a disquieting invitation to touch, challenging our comfortable perceptions of everyday items and delving into the uncanny subconscious.

Take Henri Matisse, a master of Fauvism. His still lifes, like 'The Red Room', explode with color and pattern, not necessarily aiming for realism but for emotional impact. The objects are just a starting point for a riot of vibrant hues. It's a reminder that art doesn't have to be a mirror; it can be a window into a different, more expressive reality, something that deeply informs my own use of bold colors in abstract art, where feeling often overrides exact representation, much like Matisse captured the emotional truth of a scene rather than its photographic one. I often look at his arrangements and think about how he distilled complex forms into pure, joyful color – a principle I constantly strive for.

Henri Matisse - The Red Room, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

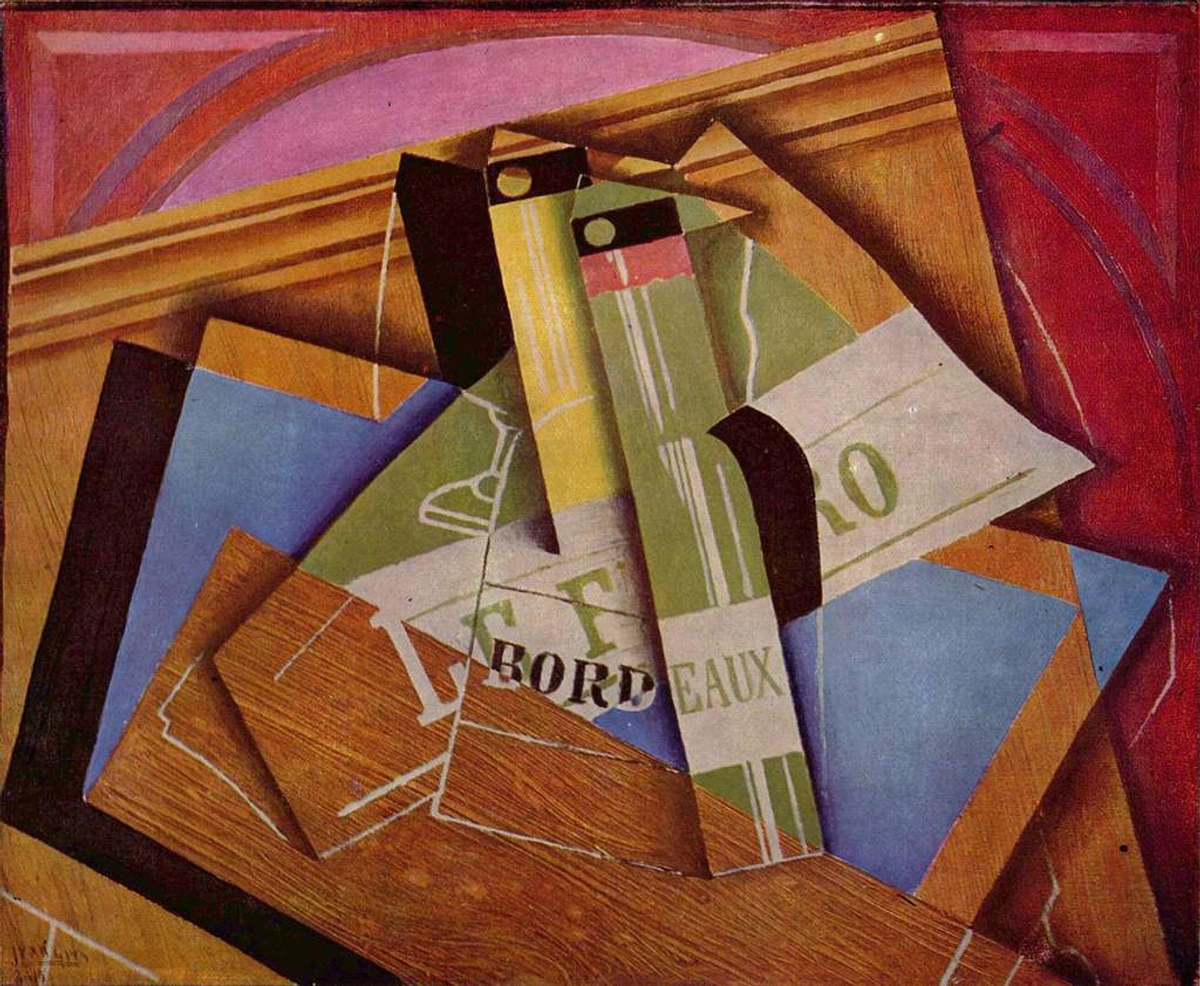

And then there’s Cubism. Oh, Cubism! I wrote a whole ultimate guide to Cubism because it fascinates me so much. Artists like Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris took objects and absolutely shattered them, reassembling them from multiple viewpoints on a single canvas. A bottle isn't just a bottle; it’s a collection of facets, lines, and planes, allowing you to see an object simultaneously from all sides at once. This revolutionary approach, initially termed Analytical Cubism, focused on dissecting forms. Later, Synthetic Cubism saw artists reassembling these fragments and introducing collage elements, further blurring the lines between art and reality. It truly makes you question how we perceive reality, shattering the singular, fixed viewpoint that had dominated Western art for centuries. Is there one fixed view, or are our experiences always a fascinating, fragmented collage pieced together by our minds? Its profound questions about perception and reality resonate deeply with me; the Cubist fragmentation of form, for instance, directly informs my approach to deconstructing objects into pure color and line in my abstract pieces, challenging the idea of a singular, fixed viewpoint – a concept I grapple with and celebrate in my own multi-layered abstract works. And honestly, the first time I saw a Cubist still life, my mind felt delightfully broken, but in the best possible way!

Juan Gris Violin and Grapes, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

Still Life with a Bottle of Bordeaux, Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0

This spirit of audacious experimentation, born in the crucible of Modernism, continues to fuel still life today, making it one of the most resilient and adaptable genres in art. What new ways of seeing do you think these modern masters opened up for us?

Still Life as a Training Ground for Artists

Before we dive into how still life manifests across different cultures and today, it's worth taking a moment to appreciate its fundamental role in artistic training. For centuries, and still today, still life has served as an indispensable classroom for artists, myself included. Why? Because it offers a controlled environment to master core artistic principles without the complexities of a moving model or an ever-changing landscape. Here, an artist can meticulously study composition, honing the skill of arranging elements within a frame to create balance, tension, and flow. It’s also the perfect arena for understanding light and shadow – how light falls on different textures, creating highlights, mid-tones, and deep shadows, and how these elements define form. Then there's the challenge of rendering texture: capturing the sheen of metal, the translucence of glass, the softness of fabric, or the rough skin of a fruit. These seemingly 'still' arrangements push an artist to truly see, to observe every minute detail, and to translate that observation into a convincing visual narrative. For me, it was a crucial step in learning to deconstruct reality, a skill that now underpins my abstract compositions. It’s a quiet but rigorous discipline that builds the foundational skills necessary for any artistic pursuit, regardless of the ultimate stylistic direction.

A Universal Language: Still Life Across Cultures

But is this fascination with arranging objects solely a Western phenomenon? While this journey has largely focused on the Western tradition, it's crucial to acknowledge that the impulse to arrange and imbue objects with meaning is a universal human trait, manifesting across diverse cultures and millennia. Long before the term "still life" existed, we find practices that echo its essence. From the meticulously arranged offerings in ancient Mesoamerican civilizations – often featuring maize, cacao, or precious stones as expressions of reverence and supplication – to the symbolic placements in some Indigenous traditions, where objects might represent ancestral connections or spiritual power, the inanimate has always held profound significance. These arrangements, much like Western still lifes, involve deliberate composition, focus on form and texture, and an invitation to contemplation.

Consider the profound meditative art of Japanese Ikebana flower arranging, rooted in principles of harmony, balance, and impermanence, where each branch and blossom carries philosophical weight, embodying a spiritual still life that communicates balance and continuity. Chinese scholar's rocks, revered for their aesthetic and philosophical qualities (often linked to Taoist principles of balance and harmony with nature), are essentially still life sculptures curated from nature, chosen for their ability to evoke vast landscapes or stimulate quiet contemplation. Even in many African and Oceanic cultures, everyday or ceremonial objects are arranged in ways that carry deep spiritual or social significance, inviting contemplation of their inherent power and interconnectedness with the human and natural world. Think of the intricate arrangements of power figures, sacrificial materials, or tools used in rites of passage in some West African traditions, where each object's placement is deliberate, conveying stories, status, and spiritual energy. Consider the symbolic offerings in ancient Chinese bronze rituals, the meticulously arranged altars in Hindu pujas, or the spiritual significance of grouped objects in some Indigenous Australian artworks, where each element might represent a story, a lineage, or a connection to the land.

Even in the intricate world of Islamic art, particularly in decorative arts, calligraphy, and architectural motifs, we find a profound appreciation for ordered arrangements, often featuring geometric patterns, floral designs (arabesques), and calligraphic elements that, while not representational still life in the Western sense, create a powerful visual harmony and symbolic resonance, elevating inanimate forms to a spiritual plane. This rich tapestry of global traditions demonstrates that still life isn't a uniquely Western invention, but a worldwide narrative of human observation, reverence, and artistic expression through the inanimate. Learning about these diverse approaches has profoundly broadened my own artistic perspective, reinforcing my belief in the universal language of objects and their power to communicate beyond words. I often find myself reflecting on these cross-cultural compositional philosophies when arranging elements in my own abstract pieces, seeking a similar harmony and symbolic depth. It’s a powerful reminder that the desire to find meaning and beauty in the objects around us transcends borders and time.

Still Life Today: An Enduring Conversation

So, where does that leave us today? Still life is still very much alive and kicking, probably more diverse and experimental than ever. Contemporary artists continue to push boundaries, using everyday objects to comment on consumerism, identity, politics, environmental concerns, or simply to explore aesthetic possibilities in new ways. Take, for instance, the hyperrealist sculptures of Ron Mueck; while depicting human figures, their uncanny stillness, meticulous detail, and carefully chosen poses often evoke a "still life" quality, forcing us to re-examine the ordinary and the nature of presence. Or consider the conceptual still lifes of artists like Gabriel Orozco, who uses found objects such as discarded bottle caps or flattened cardboard boxes to create poetic and thought-provoking arrangements, often commenting on urban decay, transience, and overlooked beauty.

Beyond traditional painting and sculpture, contemporary artists experiment with still life in photography, video installations, digital art, and even performance art, using curated arrangements to explore digital culture, the transient nature of consumerism, or algorithmic aesthetics. Think of the meticulous, often humorous, food photography of Wolfgang Tillmans, with his casual, yet intensely composed images of supermarket shelves or half-eaten takeaway meals, where even seemingly mundane objects are carefully framed and lit to adhere to classic still life principles. Or the sculptural assemblages of artists like Haim Steinbach, who elevates mass-produced objects like ceramics, books, or toys into thought-provoking displays by arranging them on custom-designed shelves, turning consumer goods into critical commentaries on commodity culture. Even in fields like set design for theatre or film, or the art of culinary presentation, the principles of still life – composition, lighting, symbolism through object arrangement – are subtly at play, demonstrating its pervasive influence, creating mood, conveying information, and enhancing aesthetic appeal.

Messy colorful artist's palette, Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication

It’s a testament to still life’s enduring power – the challenge artists embrace in bringing life and meaning to inanimate objects, often without the aid of narrative or human expression, proving that even seemingly static arrangements can tell compelling stories. Perhaps a discarded piece of plastic, much like a conceptual still life artist might use, inspires a particular abstract form or a combination of vibrant colors in my studio, transforming the overlooked into something new and expressive. It's about finding that resonance in the mundane and elevating it through color and form, much like my own process of creating abstract art.

Modern Still Life, Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication

For me, as an artist exploring vibrant, often abstract forms, I find the core idea of still life incredibly inspiring. It's about finding beauty and meaning in the simple arrangements around us. Whether it's the composition of objects on my desk or the way light hits a bowl of fruit, there’s always a story, a feeling, waiting to be captured. It's about bringing life and meaning to inanimate things, much like I strive to do in my own abstract art with bold colors and dynamic forms, finding resonance in the mundane and elevating it. And yes, sometimes it's also a challenge to convey all of that purely through static objects, which I think is part of the enduring appeal for artists throughout history. Even today, still life remains a crucial foundational practice for artists, honing observational skills, composition, and understanding of light and shadow, regardless of their ultimate stylistic direction. It's a fundamental exercise that pushes artists, including myself, to truly see.

Abstract Flower Still Life, Zen Dageraad, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

And that, my friends, is the magic. Still life reminds us to slow down, to observe, and to find the extraordinary in the ordinary. It’s not just about a painted object; it’s about a painted meditation, a profound meditation on the overlooked beauty of the everyday. Maybe that’s why I find myself increasingly drawn to the calm introspection it offers, a balance to the more energetic pieces I create for sale. It truly is a genre that belies its name, proving itself to be anything but 'still,' and perhaps, the most profound testament to humanity's ongoing quest to find meaning in the world around us. This deep connection between historical art and my contemporary practice is something I explore daily in my studio; often finding echoes of ancient symbolism or Cubist fragmentation in my vibrant abstract pieces. So, the next time you encounter a still life, whether it's in a museum or just the arrangement of items on your kitchen counter, I encourage you to look beyond the surface – what stories are these objects whispering to you? What quiet conversations are they having? It's often more than you think. And if you're ever near my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, I invite you to see how these historical threads subtly weave into even the most contemporary pieces. Or, for a broader sense of my creative journey, check out my timeline. It's all connected, really, in this wild, wonderful world of art, and it's why I also love creating pieces for sale.

Frequently Asked Questions About Still Life Painting

As we've journeyed through the dynamic history of still life, from ancient offerings to contemporary provocations, you might have some lingering questions. To address some common curiosities about this enduring and surprisingly vital genre, let's dive into some frequently asked questions.

What is still life painting?

Still life painting is a genre of art that depicts inanimate objects, typically common household items, natural objects (like fruit, flowers, or dead game), or man-made artifacts. The term "still life" itself comes from the Dutch word "stilleven," emphasizing its focus on static, everyday objects. It allows artists to explore composition, light, shadow, texture, and symbolism without the complexities of human figures or landscapes, offering a profound meditation on the overlooked beauty of the everyday. It's an artistic challenge I find incredibly rewarding: to infuse inert objects with a sense of life and narrative, a genre that, for me, transformed from 'beige wallpaper' into a profound meditation on the overlooked beauty of the everyday.

Why is still life painting important?

Still life painting is important because it elevates everyday objects to subjects worthy of contemplation, inviting viewers to find beauty and meaning in the mundane. It allows artists to explore fundamental artistic principles like composition, light, and texture, often serving as a training ground for mastery. Historically, still life has conveyed rich symbolism, moral lessons, and reflections on mortality or prosperity. It also plays a crucial role in documenting historical objects, materials, and cultural practices, offering a valuable historical record. In modern and contemporary art, it provides a versatile platform for experimentation, commenting on consumerism, identity, and the nature of perception itself, proving its enduring adaptability and relevance. For artists today, including myself, it remains a crucial exercise for honing observational skills and understanding how light and form interact, a journey I've personally experienced from dismissing it as 'beige wallpaper' to finding profound inspiration and relevance in its quiet power.

What are the different types of still life paintings?

Still life painting encompasses various sub-genres, particularly prominent during the Dutch Golden Age. These include:

- Flower Pieces: Paintings exclusively featuring bouquets and floral arrangements, often symbolizing beauty, transience, or specific virtues. Famous artists include Rachel Ruysch and Jan van Huysum.

- Breakfast Pieces (Ontbijtjes): Modest depictions of simple meals, often emphasizing everyday abundance and a quiet celebration of simple, Protestant virtues. Artists like Willem Claesz. Heda and Clara Peeters excelled in this genre.

- Banquet Pieces (Banketjes): More elaborate displays of food and drink, showcasing luxury, culinary skill, and often an overt display of social standing, sometimes with subtle warnings against excess or the fleeting nature of wealth. Abraham van Beyeren is a notable artist.

- Pronkstillevens: "Ostentatious still lifes" characterized by lavish arrangements of expensive, exotic, or rare objects, serving as a display of wealth and taste. Willem Kalf was a master of these.

- Vanitas Still Lifes: Moralizing works featuring symbols of mortality and the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures (skulls, hourglasses, snuffed candles). Harmen Steenwyck produced iconic Vanitas works.

- Trompe l'oeil: A French term meaning "deceive the eye," these paintings masterfully create the illusion of three-dimensional reality, making viewers question what is real. Samuel van Hoogstraten and Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts were key practitioners.

What is the difference between Vanitas and Memento Mori?

While often used interchangeably and sharing similar themes, Vanitas and Memento Mori have distinct nuances. Memento Mori, meaning "remember you must die," is a broader concept that encourages reflection on mortality and the transience of life, often to inspire piety or a focus on eternal salvation. It can appear in many forms, from skulls in still lifes to tomb effigies. Vanitas, meaning "vanity" or "emptiness," is a specific subgenre of still life painting that flourished particularly in the Dutch Golden Age. Vanitas paintings explicitly use symbolic objects (like skulls, snuffed candles, wilting flowers, luxury items) to illustrate the ultimate futility and emptiness of earthly possessions and pleasures, explicitly admonishing against worldly vanity. So, while all Vanitas paintings are Memento Mori, not all Memento Mori are Vanitas paintings; Vanitas focuses specifically on the vanity of material life, acting as a direct critique of worldly attachments.

What is the difference between a still life and a genre painting?

A still life focuses exclusively on inanimate objects, arranged for artistic study or symbolic meaning. A genre painting, on the other hand, depicts scenes from everyday life, often featuring human figures engaged in ordinary activities like household chores, celebrations, or market scenes. While both capture aspects of daily existence, a genre painting tells a story or portrays a moment with human interaction (e.g., Jan Steen's lively household scenes), whereas a still life finds its narrative purely in the arrangement and symbolism of objects.

What are common themes or symbols in still life?

Common themes often include mortality (vanitas, memento mori), the fleeting nature of life, wealth and abundance, the five senses, the passage of time, domesticity, science, and the celebration of everyday objects. Symbolism is often layered, with elements like skulls (mortality), wilting flowers (transience), fresh fruit (life, fertility), insects (decay), books (knowledge), or clocks (time) carrying specific meanings that viewers of the time would have understood. The interpretation of these symbols has also evolved over time, reflecting changing cultural values and philosophical ideas about life, death, and material existence, making understanding historical context crucial.

What are the challenges of creating a still life?

Creating a compelling still life, despite its apparent simplicity, presents unique artistic challenges. Artists must imbue inert objects with life and narrative, often without the aid of human figures or dynamic landscapes. This requires masterful control over composition, lighting, texture, and color to evoke emotion or convey meaning. For me, the challenge lies in distilling the essence of the objects, finding that luminous quality and interplay of light and shadow, and then translating it through a unique, often abstract lens. It's a constant exercise in finding the extraordinary in the seemingly mundane, pushing me to truly see beyond the surface. It demands patience, keen observation, and the ability to find a compelling story in silence.

When did still life become a recognized genre?

While still life elements appeared in ancient art, it wasn't until the 17th century, particularly in the Netherlands, that still life painting emerged as an independent and respected genre. Dutch Golden Age artists specialized in these works, leading to its widespread popularity and development across Europe.

Who are some famous still life painters?

Many artists have excelled in still life across different periods. Key figures include: Jan Brueghel the Elder (Flemish Baroque, known for lush flower pieces), Clara Peeters (Dutch Golden Age, pioneering female artist known for her meticulously detailed and symbolic breakfast pieces), Willem Kalf (Dutch Golden Age, master of pronkstillevens), Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (18th-century French, celebrated for his humble domestic still lifes), Paul Cézanne (Post-Impressionism, father of modern art, revolutionized perspective), Vincent van Gogh (Post-Impressionism, known for expressive flower paintings), Henri Matisse (Fauvism, master of color and pattern), and Pablo Picasso (Cubism, fragmented forms and multiple viewpoints). Contemporary artists like Wolfgang Tillmans, Haim Steinbach, and Audrey Flack (known for photorealist still lifes) continue to push its boundaries today, evolving a tradition that I, too, engage with in my vibrant abstract pieces, particularly drawing inspiration from the color and emotionality of Matisse and the fragmented perspectives of Cubists like Picasso.

Glossary of Still Life Terms

- Stilleven: Dutch term meaning "still life" or "static model," from which the English term derives.

- Xenia: Ancient Greek concept of hospitality, often visually represented in Roman art through depictions of food and drink offered to guests.

- Trompe l'oeil: (French for "deceive the eye") An art technique that creates an optical illusion, making objects appear three-dimensional.

- Didactic: Art intended to teach a moral lesson or convey information, particularly common in Medieval religious art.

- Artistic Hierarchy: A traditional ranking of art genres, prevalent until the Modern era, placing history painting highest and still life lowest.

- Pronkstillevens: (Dutch for "ostentatious still life") A subgenre of Dutch Golden Age still life characterized by lavish displays of expensive and exotic objects.

- Vanitas: A specific subgenre of still life painting (primarily Dutch Golden Age) that uses symbolic objects to illustrate the transience of life, the futility of worldly pleasures, and the inevitability of death.

- Memento Mori: (Latin for "remember you must die") A broader artistic or symbolic trope that serves as a reminder of mortality. All Vanitas are Memento Mori, but not vice versa.

- Analytical Cubism: Early phase of Cubism (c. 1907-1912) characterized by the fragmentation and geometric deconstruction of objects from multiple viewpoints.

- Synthetic Cubism: Later phase of Cubism (c. 1912-1914) featuring simpler forms, bolder colors, and the integration of collage elements.

- Ikebana: The traditional Japanese art of flower arrangement, emphasizing harmony, balance, and impermanence.

- Arabesques: Intricate and curvilinear decorations found in Islamic art, often featuring interweaving foliage, scrolls, and geometric patterns.