Neoclassicism: Order, Virtue, & Its Unexpected Echoes in Abstract Art

Dive into Neoclassicism, the powerful art movement that championed reason, classical ideals, and civic duty. Explore its precise visual language, moral purpose, influential artists like David, and its surprising, enduring legacy in architecture and modern abstract art today.

Neoclassicism in Art: My Journey into Order and Enduring Ideals

Ever walked into your studio after a particularly wild painting session and thought, 'Right, time for some serious decluttering?' I know that feeling all too well. Sometimes, after wrestling with a particularly vibrant and chaotic abstract piece that just wasn't 'gelling,' I crave order. A sense of things being just so, like hitting a reset button. It’s a yearning for an underlying framework, the architectural bones of a composition, before letting the colors dance. Well, imagine the art world having that exact same urge after centuries of Baroque drama and Rococo exuberance. That, to me, is Neoclassicism entering the stage – an artistic sigh of relief, bringing back a bit of discipline and dignity. And here’s the kicker: even in my own vibrant, often abstract work today, I find myself circling back to these very principles, discovering surprising echoes of order and structure. Let's dive into Neoclassicism, from its ancient roots to its enduring ideals, and see how it still shapes art, even the art I create.

What is Neoclassicism? A Quick Blueprint

So, before we get too deep into the 'why,' let's lay out the 'what.' What did this 'return to basics' actually look like on the canvas, or in marble? For me, it boils down to a few key principles that shaped not just what was depicted, but how it was depicted. Honestly, you can find artists grappling with these ideas even in the most abstract corners of contemporary art, just in different clothes – because these aren't just rigid rules; they're fundamental questions about form and meaning that echo even in today's art, just in different guises. This inspiration from the past wasn't just about subject matter; it profoundly shaped how artists approached their craft, dictating a new visual vocabulary. To give you a quick cheat sheet, think of these as the building blocks of that artistic reset, a stark departure from the fleeting pleasures of Rococo or the sensory overload of Baroque:

Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Ancient Ideals | Channeling the spirit of Greece and Rome: stoicism, heroism, noble simplicity, civic virtue. Art serves a moral or political purpose – a stark departure from purely decorative Rococo fancies. |

| Visual Language | Precision, clear lines, balanced compositions, meticulous draftsmanship, virtually invisible brushwork, sculptural figures, muted palettes. Emphasis on form and line over flamboyant spectacle. |

| Idealism | Depicting the ideal, heroic, perfectly formed figures over gritty reality. An aspiration of how things should be, reflecting universal truths and perfect forms, not fleeting moments. |

| Moral Purpose | Art as a visual sermon, call to patriotism, reinforcement of virtue. Often commissioned to project power, legitimacy, or moral authority, with clear, unambiguous messages, unlike the often whimsical or secular themes preceding it. |

These principles weren't just academic exercises; they were the very soul of the Neoclassical movement, guiding artists in their quest for clarity, moral authority, and timeless beauty. Now, let's explore why this artistic movement burst onto the scene with such conviction.

The Great Artistic Reset: Why the 18th Century Yearned for Order

I've always been fascinated by why movements happen. It's rarely a random thing, right? Like, my decision to finally organize my art supplies wasn't out of nowhere; it was a desperate plea from my brain for calm amidst the chaos of tubes and brushes. For art in the late 18th century, the 'mess' was the delightful, yet for many, ultimately excessive, Rococo style. Picture canvases dripping with ornate curves, frothy pastels, and scenes of aristocratic leisure that, while beautiful, often felt intellectually light, focused more on fleeting pleasure than profound meaning.

Before that, there was the dramatic, emotionally charged rollercoaster of the Baroque – all intense chiaroscuro, theatrical compositions, and a sensory overload designed to sweep you off your feet. Don't get me wrong, there’s a place for that kind of opulent drama (and a little bit of Rococo fluff never hurt anyone, in its own right!). But there was a growing yearning for something solid, something rational, something that spoke to bigger ideas than just fleeting pleasures or overwhelming spectacle. A lot of people, myself included, needed to hit that reset button.

Enter the Enlightenment, a period where reason and logic were the absolute rockstars. This intellectual revolution wasn't confined to academic debate; it actively shaped the very themes and purpose of Neoclassical art. Influential thinkers like Rousseau, Voltaire, and Diderot championed ideas of civic duty, morality, patriotism, and the fundamental foundations of society. Art became a powerful vehicle for these lofty ideals, a visual sermon for public virtue, a tool to educate and inspire a new kind of citizen, especially in the ferment of pre-revolutionary France and other nations embracing burgeoning nationalism.

And then, serendipity! The incredible discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum literally unearthed the ancient world, giving artists a direct, tangible link to the past. It wasn't just dusty old books and academic theories anymore; it was real, preserved beauty, architecture, and sculpture. It felt like finding a perfectly preserved ancient blueprint for how to "do" art with purpose and grandeur, a stark and inspiring contrast to the perceived decadence and frivolity of the preceding eras. It was as if history itself was whispering, 'Go back to basics. Go back to what truly matters.' The Grand Tour, where young aristocrats traveled Europe studying classical ruins, further fueled this hunger for antiquity.

These currents – the intellectual vigor of the Enlightenment and the raw, unearthing power of archaeology – forged the very soul of Neoclassicism, guiding artists toward a new, principled way of seeing and creating. Now, let's look at how these foundational ideas took shape on the canvas and in marble.

The Neoclassical Canvas: Principles in Practice

These principles weren't just theoretical; they were actively woven into the fabric of every Neoclassical creation. Let's unwrap each one, shall we, and see how artists brought this blueprint to life?

Embracing the Ancients: Greek and Roman Ideals in Action

What does it mean to truly learn from the past? For Neoclassical artists, it wasn't simply about copying statues of toga-clad figures – though, let's be honest, there was plenty of that, sometimes to an almost obsessive degree! It was more about channeling the very spirit of ancient Greece and Rome. These cultures were seen as the cradle of Western civilization, embodying ideals of democracy, rationalism, and civic virtue. We're talking about ideas like stoicism (that calm, rational endurance in the face of adversity, often depicted through serene expressions even in dramatic scenes), heroism (often depicted as self-sacrifice for a greater good, rather than individual glory, as seen in legendary figures like Brutus or Socrates), noble simplicity (a rejection of excess and ornamentation in favor of clear forms and essential narratives, a direct counterpoint to Rococo's frills), and a profound sense of civic virtue (the idea that individual actions serve the community and state above personal desire).

The notion of art serving a moral or political purpose, perhaps to inspire patriotism or commemorate great deeds, became absolutely paramount. It reminds me of how the Renaissance masters also drew heavily from classical antiquity, though their echoes felt warmer, more humanistic. Neoclassicism, on the other hand, had its own distinct, almost austere, flavor. This wasn't just about rejecting ornamentation; it was a deliberate embrace of structural clarity and a deeper, often more overtly philosophical and political message, a direct reflection of Enlightenment rationalism. It said, 'Look at these ancient heroes! Be like them!' Influential figures like Anton Raphael Mengs championed a return to classical rigor, urging artists to study ancient sculpture and master drawing to achieve a 'noble simplicity.' The powerful art academies of the era, such as the French Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, played a crucial role in codifying and promoting these Neoclassical ideals through their rigorous training and annual salons, further embedding these principles into the artistic consciousness.

Visual Language: Precision and Poise on Canvas

This is where Neoclassicism really shines for me in its execution, especially if you appreciate the craft. After the swirling drama and elaborate flourishes of previous eras, artists craved clear lines, balanced compositions, and a sense of visual logic that felt almost mathematical. Every element felt intentional, placed with purpose. This meant an incredible precision in draftsmanship, achieved through countless life drawing sessions, rigorous anatomical studies, and meticulous preparatory sketches, where forms were meticulously outlined and perfected. The emphasis was on clarity and control, mirroring the rational spirit of the age.

I find their decision to make brushwork virtually invisible fascinating; it removes the artist's personal 'hand' from the painting, creating a sense of objective truth and permanence, as if the scene has always existed and always will. It's not about the painter's fleeting emotion; it's about the timeless subject. (And honestly, a part of me, after a particularly expressive piece, sometimes wishes for that kind of clean, invisible finish in my own work – though my studio often tells a different story!). Figures themselves had a monumental, sculptural quality, appearing solid and eternal, often posed like classical statues. The color palettes tended to be more muted and restrained, focusing on blues, reds, golds, and grays, but used sparingly not for dramatic spectacle, but to ensure that the forms and lines remained the absolute stars of the show, keeping the focus on clarity and structure. This precision wasn't merely aesthetic; it served the narrative, ensuring the viewer could easily grasp the intended moral or historical message without distraction. It was about creating a harmonious whole, where the eye could follow the narrative without getting lost in a visual labyrinth – a visual order that was both calming and didactic.

Idealism Over Gritty Reality

Neoclassical art wasn't interested in your everyday problems, your messy studio, or the gritty reality of life. Oh no. It was about depicting the ideal, the heroic, the perfectly formed human figure. Think of it as ancient Greek Instagram – everyone's flexing, perfectly proportioned, and perpetually noble. Honestly, the only thing perfectly proportioned in my studio on a Tuesday morning is the pile of discarded sketches threatening to take over my easel! This art was an aspiration, a vision of how things should be, rather than a mirror of how they are. Paradoxically, achieving this ideal perfection required immense anatomical accuracy, painstakingly rendered from classical models and life drawing, showcasing a rigorous observation within their pursuit of perfection.

This idealism was valued precisely because it reflected the Enlightenment's pursuit of universal truths and perfect forms, serving as a powerful counterpoint to what was perceived as contemporary 'decadence' or 'frivolity.' Neoclassical artists believed that by depicting the ideal, they could elevate human experience and encourage virtue. It actively pushed against the burgeoning interest in scientific observation and individual psychology that would later fuel movements like Romanticism or Impressionism, which reveled in capturing fleeting moments and ordinary life. Neoclassicism, instead, aimed for the eternal, the flawless. Not exactly my studio situation on a Tuesday morning, but inspiring nonetheless!

Moral Compass: Art with a Purpose and Political Edge

This art often had a very clear job to do. It was a visual sermon, a call to patriotism, a reinforcement of virtue – a kind of public service announcement in paint or marble. Jacques-Louis David’s 'Oath of the Horatii' is the ultimate example: three brothers pledging allegiance to Rome, their father presenting swords. It’s dramatic, yes, but it’s a drama of duty and sacrifice, not of personal anguish. It's less about individual self-expression and more about public service, if that makes sense. David's later work, 'The Death of Socrates,' further exemplifies this, showing the philosopher calmly accepting his fate for the sake of principle – a potent image of stoicism and moral courage. Even earlier, artists like Jean-Baptiste Greuze paved the way with sentimental genre scenes that highlighted moral lessons and domestic virtue, setting the stage for Neoclassicism's ethical focus.

David, in particular, became a sort of visual propagandist during the French Revolution, his canvases championing revolutionary ideals and later, Napoleon's imperial vision. His 'Death of Marat', depicting the murdered revolutionary, is a powerful example. David transforms a brutal assassination into a heroic, almost Christ-like sacrifice for a cause by depicting Marat in a serene pose, bathed in a soft light, directly referencing classical sculpture and religious martyrs to convey an ideal of stoic sacrifice and ultimate dedication. The humble wooden crate, serving as a tombstone, and the quill in his hand elevate his final moments. Neoclassical art was frequently commissioned by state or religious institutions to project power, legitimacy, and moral authority, its clear, unambiguous messages designed to rally public sentiment. Think of it as the ultimate in 'message art' – adaptable enough to serve shifting political tides, from revolution to empire.

Beyond David, other giants defined this era, showcasing the principles across various mediums:

- Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres: Known for his incredibly precise and idealized portraits and nudes, like 'La Grande Odalisque', which, despite its exotic subject, applies an almost clinical perfection to the human form, showcasing incredible draftsmanship. His monumental history painting, 'The Apotheosis of Homer,' also perfectly embodies Neoclassical grandeur and an homage to classical genius.

- Antonio Canova: A master sculptor who carved breathtakingly graceful marble figures such as 'Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss' and 'Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix', embodying ethereal beauty and classical harmony. His work often conveyed complex mythological narratives with an almost effortless elegance.

- Angelica Kauffman: A celebrated female artist of the era, known for her historical paintings and portraits that also championed classical themes and virtuous subjects, often with a distinctly graceful style. Her work frequently depicted scenes of classical antiquity or allegories of virtue, reflecting the moralizing tone of the movement.

It's clear that these artists weren't just painting pretty pictures; they were actively shaping public consciousness and reflecting the foundational shifts in societal values.

https://pxhere.com/en/photo/973226

Beyond the Easel: Neoclassical Architecture and Sculpture

But did Neoclassicism's influence truly stop with gilded frames and marble busts? Not at all! It had a massive, almost inescapable impact on architecture, sculpture, and even decorative arts. Just look around most major cities. Think of those grand, stately public buildings we often see today, like the US Capitol, the British Museum, the Pantheon in Paris, or countless banks and museums, with their imposing columns, symmetrical facades, and often, pediments, porticos, and elegant domes and arches.

These architectural elements are direct references to Roman temples and Greek civic buildings, repurposed in Neoclassical architecture to evoke specific qualities like authority, stability, and democracy. The rigorous symmetry, clear, rational design, and monumental scale were meant to inspire confidence and timeless grandeur in our institutions. Architects like Robert Adam in Britain and Claude Nicolas Ledoux in France embraced Palladian principles – drawing from the work of the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, who himself looked to ancient Rome – to create structures that were both imposing and harmonious. It’s a powerful statement, saying 'we are built on enduring foundations,' a visual assertion of stability and intellectual rigor that resonated deeply with the Enlightenment spirit.

Beyond buildings, Neoclassical sculpture, led by masters like Antonio Canova, also flourished. Sculptors sought to emulate the idealized forms and serene expressions of ancient Greek and Roman statuary, often depicting mythological figures or historical heroes with a refined elegance and technical mastery that evoked timeless beauty.

The Art World's Dialectic: Neoclassicism vs. Romanticism

But here’s the thing about art history, and perhaps about life itself: nothing exists in a vacuum. Even as Neoclassicism championed reason, order, and civic duty with such conviction, another powerful, almost diametrically opposed movement was stirring beneath the surface: Romanticism. These two often emerged concurrently, almost as artistic siblings arguing over who gets the last word on truth and beauty. Where Neoclassicism sought order and control, striving for the cool, objective clarity of marble, Romanticism embraced glorious chaos, untamed nature, and intense emotion. Critics found Neoclassicism's academic rigor and emotional restraint cold and sterile, creating fertile ground for the Romantic rebellion.

Where Neoclassicism valued reason and intellect, Romanticism championed individual feeling, imagination, and the wildness of nature, even the supernatural. It was a celebration of the unique human spirit, often passionate and suffering. Crucially, Romanticism often explored the sublime – that awe-inspiring, overwhelming feeling mixed with terror or reverence, often evoked by vast natural landscapes, dramatic historical events, or powerful forces beyond human control. Think towering mountains, raging storms, or dramatic shipwrecks, designed to humble and thrill the viewer. Where Jacques-Louis David’s 'Oath of the Horatii' epitomizes stoic duty and clear composition, Eugène Delacroix's 'Liberty Leading the People' pulsates with raw revolutionary fervor and dynamic chaos, or Caspar David Friedrich's 'Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog' embodies the individual confronting the overwhelming power of nature. Understanding this fascinating tension helps us appreciate the diverse artistic landscape of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a battle of the heart versus the head that shaped artistic expression for generations.

Enduring Echoes: Neoclassicism's Legacy Today

But does this seemingly rigid movement truly have anything to say to us today, especially those of us wrestling with the vibrant chaos of abstract art? Well, I think understanding Neoclassicism helps us appreciate everything that came after. It was a strong declaration, a definitive 'this is what art should be,' which then gave subsequent movements something powerful to react against. Think about Cubism, for instance, which completely shattered classical perspective, or even the wild abandon of Fauvism with its non-naturalistic colors. Yet, even in their rebellion, these movements implicitly acknowledged the structural foundations laid by earlier traditions.

But also, the underlying principles of structure, balance, and thoughtful composition never really go away. Even in my own abstract work, whether it's the deliberate reduction of forms to their purest geometric essence, or the carefully balanced interplay of a limited color palette in my abstract art from Cubism to contemporary expression, there’s an inherent quest for a kind of balance, a visual rhythm that holds the piece together. It's not the same classical balance, of course, but it’s a direct descendant. If an artist today wanted to explore civic duty through art, they might not paint a historical battle, but perhaps create a powerful installation highlighting the quiet heroism of everyday service providers, using form and structure to convey reverence, much like a Neoclassical master.

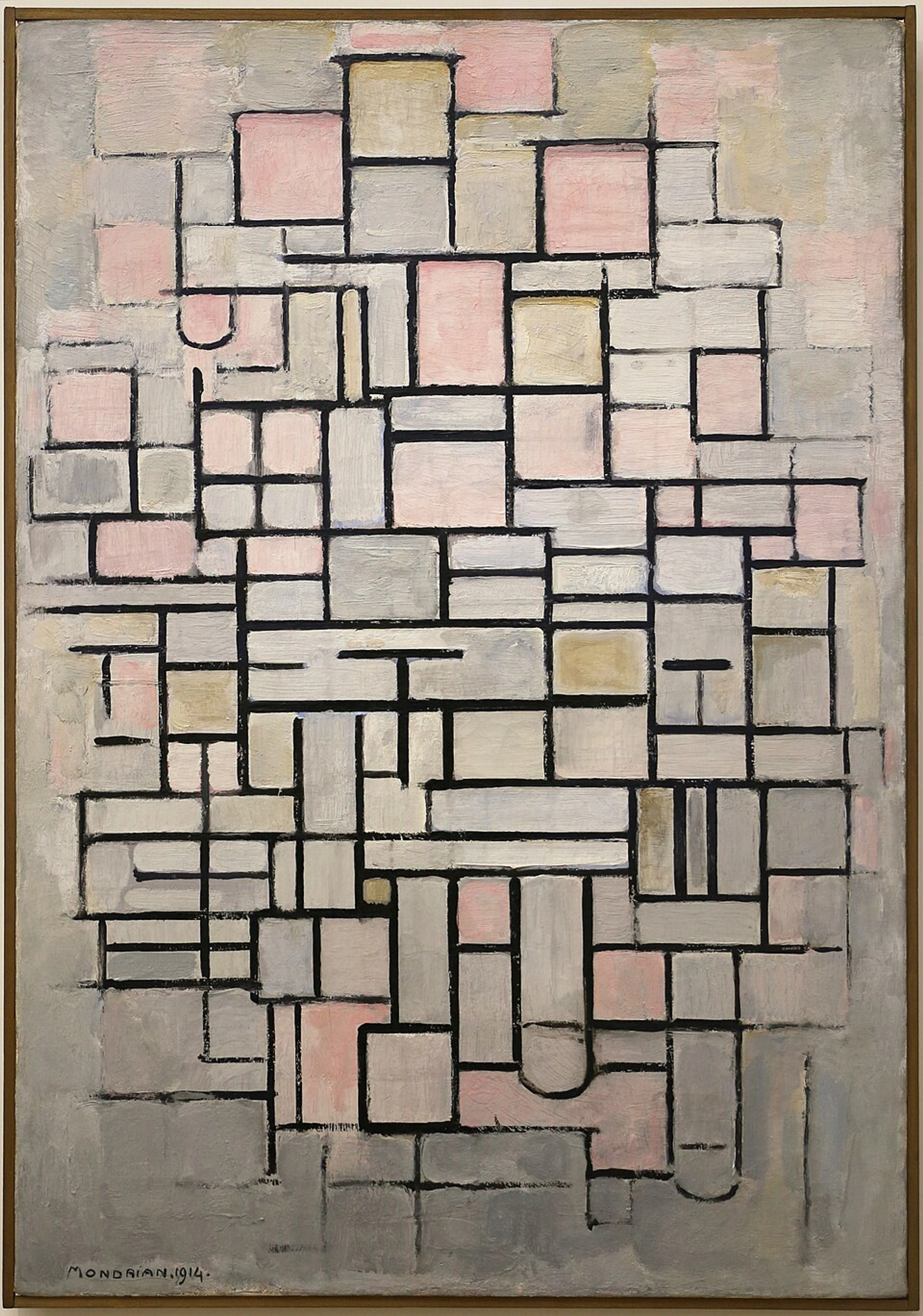

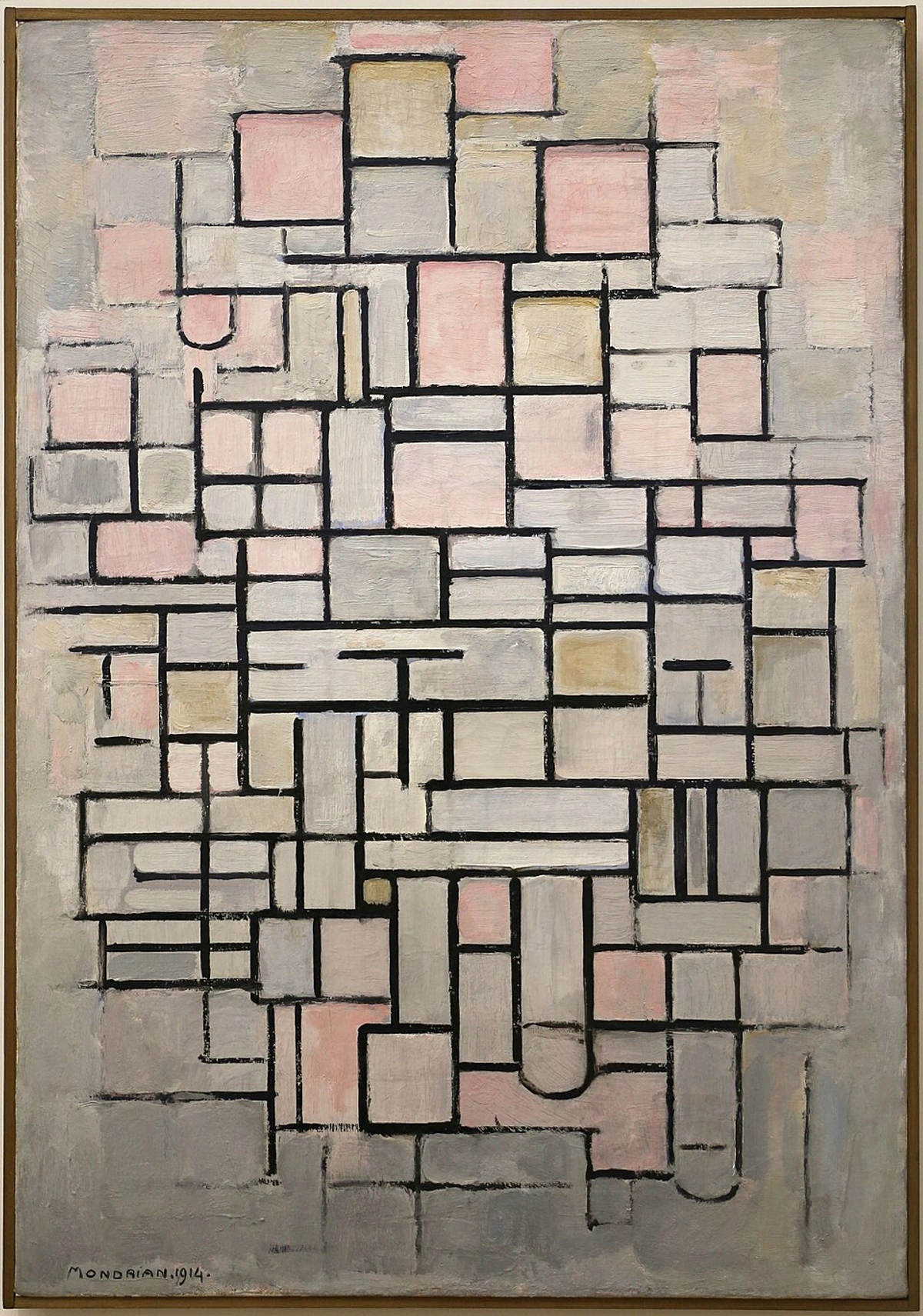

Take this early Mondrian, Evening; The Red Tree. While far from Neoclassical in its immediate style – actually, it’s quite Expressionistic – you can already sense a push towards simplifying forms, towards finding an underlying structure. It's like he's trying to get to the essence of the tree, even if it’s through color and bold outlines, not classical realism. This search for core structure, this desire for a coherent composition – a quest for the essence that, in a distant way, echoes the Neoclassical pursuit of universal forms – is a thread that runs through art history, no matter how wild the styles get.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/vintage_illustration/51913390730

The evolution from Neoclassicism's strict adherence to classical forms to this kind of abstract, yet disciplined, geometric art shows the fascinating journey artists embark on when exploring the very essence of composition. This pursuit of elemental forms and underlying order, even in abstract art, can be seen as a hyper-rational, almost distilled, form of the Neoclassical quest for universal truths and perfect forms, albeit in a radically different visual language. It's the same underlying hunger for clarity and structure, just expressed through a new vocabulary.

Here, with Mondrian’s Composition No. IV, we see order taken to an extreme purity. It’s a very different kind of order than David’s figures, but it’s an order nonetheless – a testament to the enduring human desire to find (or impose) structure, whether it’s in a heroic narrative or a grid of primary colors. Mondrian pushes order to an extreme purity, a distant echo of Neoclassicism's desire for fundamental structure, showing how the quest for ideal forms can manifest in wholly new visual languages. If you're curious about how artists like me translate these fundamental ideas into contemporary pieces, you might want to check out some of the art for sale or explore my artist's timeline to see my own journey with form and color.

So, next time you see a building with columns, or even a piece of abstract art, ask yourself: what underlying order is it trying to convey? You might be surprised by the echoes of Neoclassicism you find.

FAQ: Unpacking Neoclassicism Further

Alright, let's clear up a few common questions I get asked, or sometimes, questions I ask myself when I'm trying to wrap my head around these historical shifts and their modern resonance. Think of this as a quick Q&A to solidify our understanding:

Q: What's the core difference between Neoclassicism and plain old Classicism? A: Good question! Think of Classicism as the original Greek and Roman stuff – the direct historical period and its artistic output. Neoclassicism is a revival of those styles and ideals, happening much later (18th-19th century) as a conscious, deliberate reaction to other movements like the Rococo. It's like remaking an old movie – same core story, but with a new director and special effects (or lack thereof, in Neoclassicism's case, preferring austerity and philosophical depth!). It's a reinterpretation and reapplication of classical principles for a new age, often with a more explicitly moral or political agenda, whereas Classicism was the original expression, a natural outcome of its time.

Q: Who were the big names in Neoclassical art? A: The undisputed heavyweight champion is Jacques-Louis David, especially with his powerful, politically charged paintings. Then there’s Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, known for his incredibly precise and idealized portraits and nudes, and the sculptor Antonio Canova, who carved breathtakingly graceful marble figures. Also, don't forget Angelica Kauffman, whose historical paintings embodied many Neoclassical virtues. Other key figures include Anton Raphael Mengs (a major theorist and painter) and Jean-Baptiste Greuze (a precursor with moralizing genre scenes). They all, in their own ways, championed the return to classical principles and the Enlightenment's ideals.

Q: How did art academies influence Neoclassicism? A: Art academies, particularly the French Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, played a truly crucial role. They were the primary institutions for artistic training and exhibition, codifying Neoclassical principles into their curricula. Through rigorous instruction in drawing from classical casts and live models, and by promoting historical and mythological subjects that conveyed moral lessons, they essentially became the gatekeepers and chief proponents of the Neoclassical style. Their annual salons also dictated public taste, ensuring Neoclassicism's widespread adoption and authority.

Q: Did Neoclassicism only affect painting? A: Not at all! As we discussed, it had a massive impact on architecture (think stately public buildings, like the US Capitol, the British Museum, or the Pantheon in Paris), sculpture, and even decorative arts, influencing everything from furniture to fashion. It was a whole cultural vibe, a complete aesthetic package. Its influence shaped entire cities and left a lasting mark on public spaces, a visual assertion of enduring ideals and a calculated projection of power and stability by governing bodies.

Q: How was Neoclassicism received in its time, and what were its critiques? A: Generally, Neoclassicism was received very well, especially by the intellectual and political elite of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Its emphasis on reason, civic virtue, and a rejection of perceived decadence resonated strongly with the ideals of the Enlightenment and the revolutionary spirit. It was seen as a morally uplifting and intellectually serious art form. However, not everyone loved its rigorous formality. Some critics found it to be cold, sterile, and overly academic, lacking in warmth, spontaneity, or emotional depth. This criticism became a fertile ground for the emerging Romantic movement, which celebrated emotion and individualism, eventually leading to Neoclassicism’s gradual decline in artistic dominance as the 19th century progressed, though its influence never truly disappeared and can still be seen in various forms today.

My Final Thought: Beyond the Togas – Finding Order in Chaos

So, that’s my personal, slightly meandering take on Neoclassicism. It might seem like a rigid, almost academic movement, far removed from the vibrant, often chaotic abstract pieces you might find in my museum in Den Bosch or even what I create today. But I think it's vital. It reminds us that art, at its heart, is often a dialogue with what came before, a conversation across centuries. It’s about artists constantly asking: 'What are we trying to say? How can we say it with clarity and purpose?' Whether that purpose is civic virtue, as in David's powerful historical narratives, or pure visual joy and structure, as Mondrian later sought, the quest for meaning and form remains.

Even as Neoclassicism eventually gave way to the emotional fervor of Romanticism and the subsequent explosion of diverse modern movements, its fundamental appeal to order and clarity continued to resonate. The desire to find (or impose) structure, whether in heroic narratives or abstract grids, is an enduring human trait that Neoclassicism crystallized. In my own work, this manifests as a constant seeking of a coherent composition in a sometimes chaotic world – like the deliberate balance I strive for in a series of geometric abstractions, or the purposeful use of negative space to create a sense of calm, echoing that Neoclassic al pursuit of visual harmony. And that, I think, is a pretty beautiful principle to live by, a timeless artistic pursuit. So, I invite you: next time you see a building with imposing columns, consider not just its grandeur, but the conscious choice to evoke ancient Roman authority and democratic ideals. Or when you encounter a piece of abstract art, look past the colors and shapes to the underlying search for balance and coherence that might just be a distant echo of Neoclassical order.