Humanism in Renaissance Art: Humanity's Daring Self-Portrait & Enduring Legacy

Dive deep into Humanism's revolutionary impact on Renaissance art. Explore its philosophical roots, Neoplatonic ideals, the 'Virtù' and 'Uomo Universale' concepts, and how it transformed realism, perspective, and the classical revival. This authoritative guide covers key thinkers, artistic techniques, and its profound, enduring legacy, offering a comprehensive look at the eternal quest to define humanity.

Humanism in Renaissance Art: Humanity's Daring Self-Portrait and Enduring Questions

I used to think of "Humanism in Renaissance Art" as one of those dry academic topics, something you just had to get through. But honestly, I've found it's anything but. For me, digging into this period isn't just about art history; it's about witnessing a profound realization – a moment when humanity collectively decided to look inward and celebrate its own incredible capabilities, acknowledging its flaws but emphasizing its boundless potential. It’s about art that started reflecting us – in all our complex, sometimes messy, often glorious capacity. This revelation still resonates today, asking us, "What does it truly mean to be human? And how do we express that?" This journey will take us from a visceral encounter with art to unpacking the core tenets of humanism, exploring its profound impact on visual expression and beyond, and finally, reflecting on its enduring legacy and those very same eternal questions.

The Moment Art Stopped Whispering and Started Speaking: My First Encounter with Humanist Art

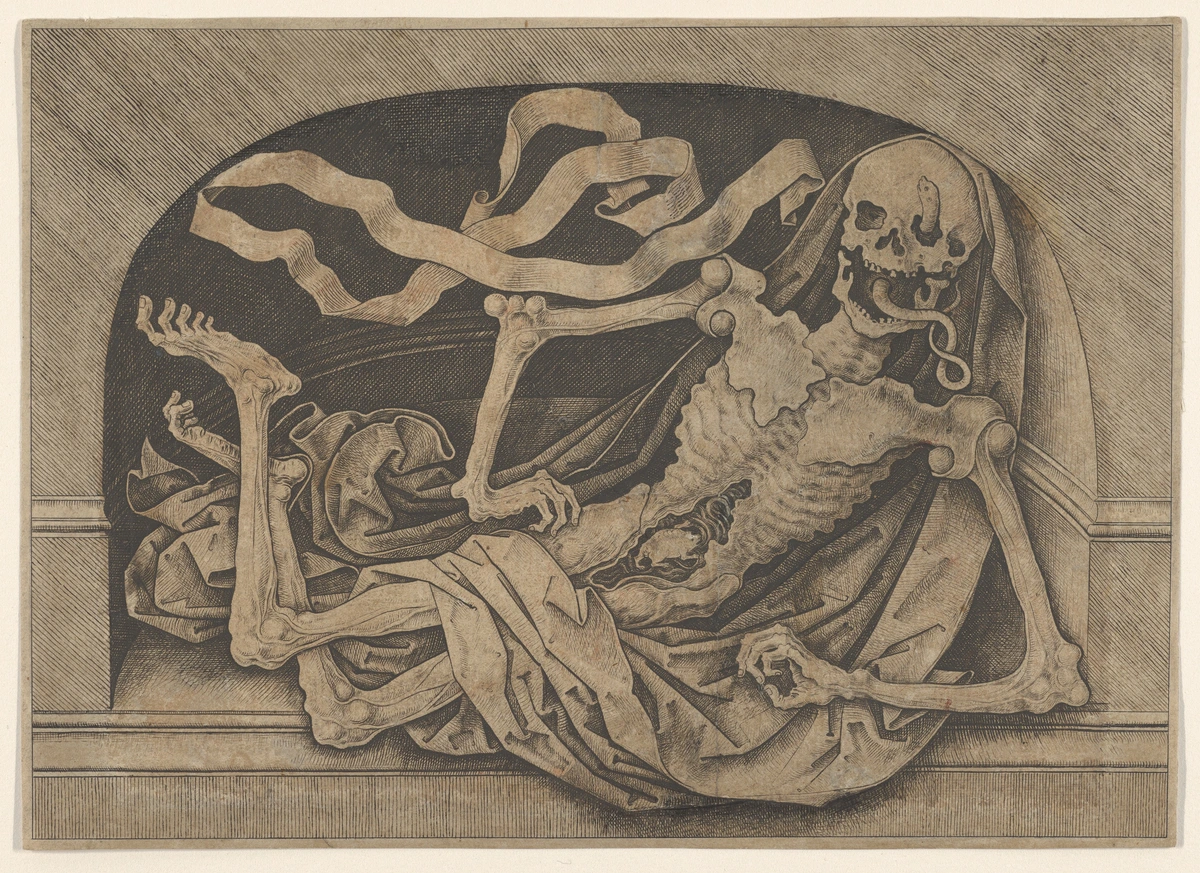

I remember a specific museum visit years ago, probably trying to impress myself (we’ve all been there, right?). I was standing before a gilded medieval altarpiece, shimmering with divine light and ethereal figures. Beautiful, yes, but it felt distant, a story whispered from another realm, full of religious symbolism rather than direct emotion. It was less about us and more about an abstract, transcendent ideal – a world where human struggle and physical reality often took a backseat to spiritual allegory.

Then, I turned a corner, and it was almost a physical jolt. I was confronted by Donatello’s Saint George, an early 15th-century marble statue. He wasn’t floating in divine grace; he was a young man, jaw firm, shield ready, thinking. His gaze was focused, his stance resolute yet vulnerable, utterly, undeniably human. His armor seemed to cling to a real body underneath, his expression conveyed a believable sense of determination, and his very posture suggested a man about to embark on a difficult, earthly task. It hit me hard: this wasn't just a change in style. It was a philosophical earthquake, a radical declaration of human worth, and humanism was its profound epicenter. The shift from the purely divine to the deeply human felt almost tangible in that marble, a testament to Donatello's groundbreaking vision and a powerful example of early Renaissance sculpture.

Unpacking Humanism: Beyond a Historical Label to a Worldview Revolution

So, when we talk about humanism in the Renaissance, let’s clear up a common modern misunderstanding right away. It's not about rejecting God or being strictly secular in the contemporary sense. Rather, it was a transformative intellectual and cultural movement that rediscovered and profoundly emphasized the inherent value, reason, and achievements of human beings. It didn't negate the divine but integrated it with a newfound, fervent appreciation for the earthly human experience. It was about expanding the scope of human concern, blending piety with a powerful sense of human agency.

Defining Renaissance Humanism: Faith, Reason, and a Human-Centered World

For the most part, we're talking about Christian humanism, where faith and human potential were seen as complementary. Humanists sought to understand God's creation more deeply through the meticulous study of humanity and the natural world. While the focus here is on this dominant form, it's worth noting that some modern interpretations later diverged into what might be called 'secular humanism', a focus solely on human experience without direct religious ties, but that was not the defining characteristic of the Renaissance movement itself. It’s also crucial to clarify that humanists didn't believe humans were inherently perfect; rather, they celebrated our potential for greatness and self-improvement, acknowledging our flaws and capacity for sin, but emphasizing our ability to overcome them through reason, moral action, and diligent effort.

The Potent Brew: Italy's Catalyst for Change

This seismic shift was rooted in several key factors that converged in Italy during the 14th and 15th centuries. Imagine a potent brew of burgeoning, independent city-states like Florence where civic pride flourished, the rise of a wealthy merchant class eager to patronize new ideas and assert their own status, and crucially, the fervent rediscovery of long-lost classical texts. Scholars like Petrarch tirelessly sought out and translated ancient manuscripts, laying the groundwork for what would become a cultural revolution. This intellectual ferment was further amplified by the establishment and flourishing of universities (like Padua, Bologna, and Florence) and smaller academies, which became vital hubs for humanist thought and debate.

Rediscovering the Ancients: Classical Wisdom and Neoplatonic Ideals

Humanists resurrected the works of Cicero, Virgil, Seneca, and, profoundly, Plato. These philosophies, particularly Neoplatonism, encouraged a holistic view of humanity’s dignified place in the cosmos. Neoplatonism, to simplify, was a Renaissance intellectual current that sought to reconcile Plato's philosophical ideas (especially about ideal forms and beauty) with Christian thought. It emphasized the divine spark within humanity and saw the earthly world, including the human body, as a reflection of divine perfection. This allowed for the celebration of human achievement and beauty without necessarily rejecting God, creating a powerful intellectual justification for the new artistic and cultural focus. For instance, the pursuit of anatomical accuracy in art wasn't just about realism; it was about understanding and celebrating the divine order expressed through the human form. Similarly, the harmonious compositions and perfect geometric ratios in paintings and architecture were seen as echoes of a higher, divine harmony, making the earthly beautiful a pathway to the spiritual. It was a beautiful paradox, a spiritual quest through earthly understanding.

Core Tenets of Humanism: A Paradigm Shift

For me, the essence of humanism distills into a few critical shifts in perspective, fundamentally altering how humanity perceived itself:

- Rebirth of Classical Antiquity: Humanists immersed themselves in the wisdom, literature, philosophy, and art of ancient Greece and Rome. They saw these classical civilizations not just as historical relics, but as living blueprints for human excellence, civic virtue, and aesthetic perfection. Think of Cicero’s rhetoric and his emphasis on public service, Virgil’s epic poetry celebrating human struggle and triumph, Seneca’s moral philosophy guiding ethical living, and Plato’s ideals of beauty and truth – these weren't merely subjects of study, but guides for a richer individual life and a better society. This profound return to the roots of Western thought profoundly influenced all aspects of Renaissance art and culture, giving birth to what we now call classical art. What's crucial to remember here is that this wasn't mere imitation; it was a reinterpretation, a creative dialogue with the past that energized ancient forms with a distinctly Renaissance spirit, making classical wisdom relevant to their contemporary world and inspiring new narratives in painting and sculpture.

- Elevation of Human Reason and Potential (Virtù): This was, quite frankly, revolutionary. Diverging from a medieval worldview that often perceived humanity as inherently flawed, sinful, and subservient to divine will, humanists celebrated our innate capacity for logic, creativity, moral action, and self-improvement. This belief meant that humans, through their intellect and will, could achieve extraordinary things and shape their own destinies – a belief that directly fueled the creation of art that dared to challenge previous conventions, like the static, hierarchical compositions often seen in earlier periods. This optimistic, yet grounded, view of human agency was epitomized by the concept of virtù. Far more than just "virtue," virtù in the Renaissance sense was a powerful blend of individual skill, excellence, talent, moral strength, and the capacity to achieve greatness in any field, particularly in public life, scholarship, and the arts. It was the active demonstration of human potential, a pursuit of fame and lasting legacy through one's deeds and creations. Artists, too, embodied this virtù through their mastery of technique, innovative problem-solving, and ambitious projects, like Brunelleschi's daring dome for Florence Cathedral – a feat of engineering and artistic vision that stands as a monumental testament to human ingenuity. Patrons also sought to display their virtù through commissioning magnificent artworks that projected their power, taste, and intellectual sophistication. This also led to the concept of the Uomo Universale (the "Universal Man" or "Renaissance Man"), an ideal of a well-rounded individual skilled in multiple disciplines – art, science, philosophy, and warfare – seeing man as a microcosm of the universe, capable of mastering all aspects of knowledge and creation. Figures like Leon Battista Alberti (architect, painter, philosopher, humanist, and athlete) became living embodiments of this aspiration, truly pushing the boundaries of what a single individual could achieve. While few truly achieved this ideal, it served as a powerful aspirational goal, a constant challenge to strive for excellence, a goal that even I, in my own artistic journey, sometimes find daunting!

- The Studia Humanitatis: At its academic core, humanism championed a curriculum focused on grammar (the study of language for clarity and eloquence), rhetoric (the art of persuasive speaking and writing, vital for civic life), poetry (for moral instruction and aesthetic pleasure), history (to learn from the past and understand human action), and moral philosophy (for ethical living and good governance). The goal? To cultivate a well-rounded, articulate, and virtuous citizen capable of both intellectual thought and active public service. These studies, unlike the often abstract theological debates of medieval scholasticism (a system of philosophy and theology characterized by the careful use of dialectic, developed and taught in medieval European universities, primarily concerned with reconciling classical philosophy with Christian dogma), were seen as practical tools for a fulfilling and impactful life in the earthly realm. Think of it as a foundational liberal arts education, something that still feels incredibly relevant today for developing well-rounded individuals. This emphasis on eloquent communication and historical understanding directly impacted how artists conceived of narrative, composition, and even the expressive gestures of their figures. The invention of the printing press, dramatically accelerating the dissemination of these classical texts and humanist ideas across Europe, made them accessible to a wider audience than ever before, fostering a more literate and intellectually curious public, even beyond the intellectual elite, and allowing art theory to spread rapidly.

- Civic Virtue and Active Engagement: Humanists often championed active participation in civic life and public service. This was known as civic humanism, particularly strong in Italian city-republics. Figures like Leonardo Bruni, who wrote treatises on the Florentine republic emphasizing the importance of active participation for the common good, exemplified this ideal. They believed that individuals had a duty to contribute positively to their communities and states, rather than retreating into monastic contemplation. This focus on making a tangible difference in the world translated into art that celebrated civic leaders, important historical events, and allegories of good government, reinforcing the values of the republic. Botticelli’s allegorical paintings, though often mythological, sometimes carried undertones of civic virtue, as did the many portraits of influential Florentine citizens. Even political thinkers like Machiavelli, while controversial, engaged with humanist ideas of virtù in the context of effective statecraft, illustrating the pervasive nature of these ideals. Patrons frequently commissioned works that not only beautified their cities but also served as visual propaganda, celebrating their power, lineage, and the civic identity they wished to project.

To truly grasp this paradigm shift, I find it helpful to look at it as a direct contrast. It’s like comparing two entirely different lenses through which humanity viewed itself and its place in the universe. Medieval art, for instance, often featured static, hieratic compositions that emphasized symbolic meaning over physical reality, and figures frequently lacked the anatomical precision and emotional nuance that would become hallmarks of the Renaissance:

Feature | Medieval Worldview | Renaissance Humanist Worldview |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | The Divine, Salvation, Afterlife, often expressed through religious symbolism | Human Experience, Earthly Life, Individual Potential, Civic Engagement, Fame, Legacy |

| Knowledge Source | Religious texts, Church authority, Dogma (accepted beliefs considered true without question), Scholasticism | Classical texts, Human reason, Empirical observation, Direct experience, Scholarly Debate, Virtù |

| Artistic Ideal | Symbolic, Transcendent, Hierarchical (divine above human), Often stylized, less concerned with anatomical accuracy or earthly beauty | Realistic, Naturalistic, Individualized (celebrating human form and emotion), Harmonious, seeking ideal beauty and proportion |

| Purpose of Life | Glorify God, prepare for eternity, endure earthly suffering | Cultivate virtù, achieve excellence, contribute to society, explore human capacity, leave a lasting legacy |

| Human Role | Fallen, dependent on divine grace, pilgrim on Earth | Capable of greatness, worthy of study and celebration, agent of change in the world, microcosm of the universe, endowed with reason and free will |

This shift wasn't just aesthetic; it was a profound reorientation of humanity's gaze, from the ethereal heavens to the tangible, vibrant world around them, making art a mirror of humanity's newfound confidence and intellectual curiosity.

The Art of Humanity: How Humanism Remade Visual Expression from the Ground Up

This profound intellectual shift wasn’t just confined to scholars and their manuscripts; it exploded onto the canvas and into marble, irrevocably transforming Italian Renaissance art in truly revolutionary ways. If philosophy was the blueprint, art was the magnificent construction. Artists, now seen as intellectual geniuses rather than mere craftsmen, literally remade the canvas and the chisel to mirror this new worldview.

The Individual and the Uomo Universale Take Center Stage

Remember that jolt I felt with Donatello's Saint George? That's the individual stepping out of the symbolic shadows and into the spotlight. Medieval art often depicted figures as archetypes, symbols of faith rather than distinct personalities. Humanism, however, pushed artists to portray people with unprecedented psychological depth, anatomical accuracy, and a sense of unique agency. This was a radical departure, emphasizing the unique worth and dignity of each human life. It was a recognition that humanity itself was a masterpiece, worthy of meticulous study and glorious celebration – a reflection of the divine spark within us.

- Portraits: Patrons, driven by humanist ideals of individual worth and achievement, increasingly commissioned portraits that captured not just physical likeness, but also their unique personality, social status, and even inner thoughts. Consider Leonardo da Vinci's enigmatic Mona Lisa. It's not merely a woman; it's a personality, an individual with a subtle, complex expression that we’re still debating centuries later. This is the power of focusing on the individual. Botticelli's portraits, like his Portrait of a Young Man, also beautifully exemplify this focus on individual character, as do works by artists like Ghirlandaio or Giovanni Bellini. Even in the Northern Renaissance, artists like Jan van Eyck, while steeped in religious tradition, likewise embraced hyper-realism and individual character in his portraits, showing a parallel humanist influence.

- The Idealized Human Form & the Uomo Universale: Inspired by classical Greek and Roman sculptures (like those you might see in Skulpturhalle Basel), artists like Michelangelo with his iconic David, celebrated the human body as a testament to beauty, divine perfection, and incredible potential. Michelangelo's David, poised yet powerful, embodies the humanist ideal of physical and moral strength (virtù), reflecting the concept of the Uomo Universale (the "Universal Man" or "Renaissance Man"). This ideal championed the well-rounded individual, skilled in multiple disciplines – art, science, philosophy, and warfare – seeing man as a microcosm of the universe, capable of mastering all aspects of knowledge and creation. Figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Leon Battista Alberti (an architect, painter, writer, and theorist) became living embodiments of this aspiration, embodying that relentless pursuit of mastery, the dedication to continuous learning and improvement that truly encapsulates virtù for me.

Mastering the World: Realism, Perspective, and Empirical Observation

Humanists championed understanding the world through direct observation and rational inquiry. Artists, embracing this spirit, revolutionized their techniques to capture reality with breathtaking accuracy. But how did artists translate this newfound intellectual curiosity into tangible, breathtaking art? They literally remade the canvas and the sculptural form.

- Linear Perspective: Brunelleschi and later Masaccio famously developed and applied linear perspective, creating the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. This wasn't just a clever trick; it was a rational, mathematical method for ordering the visual world, literally placing the human viewer at its logical, measurable center. Imagine standing before Masaccio's Holy Trinity and feeling drawn into the architectural space, as if it were a window into another world. It was a profound statement about the human mind's ability to comprehend, organize, and even control reality. This revolution in rendering space is so fundamental, we explore it more deeply in our definitive guide to perspective in art.

- Anatomical Accuracy & Foreshortening: Artists undertook rigorous, sometimes illicit (let's just say a few churchyards might have been disturbed in the name of art), studies of the human body – including dissections – to achieve unprecedented lifelike depictions of muscles, bones, and skin. This commitment to realism brought immense gravitas and believability to both religious and secular scenes. Coupled with foreshortening, a technique for depicting an object or human body part as if it is receding into space, this created a powerful illusion of depth and dynamism. This reflected a profound humanist desire to truly understand the physical world, rather than merely abstracting it or depicting it symbolically. This dedication to empirical observation was a cornerstone of the humanist approach, directly linking to early scientific inquiry, a true fusion of art and nascent science. This level of realism, particularly in sculpture, transformed the way the human form was represented, as detailed in our ultimate guide to Renaissance sculpture.

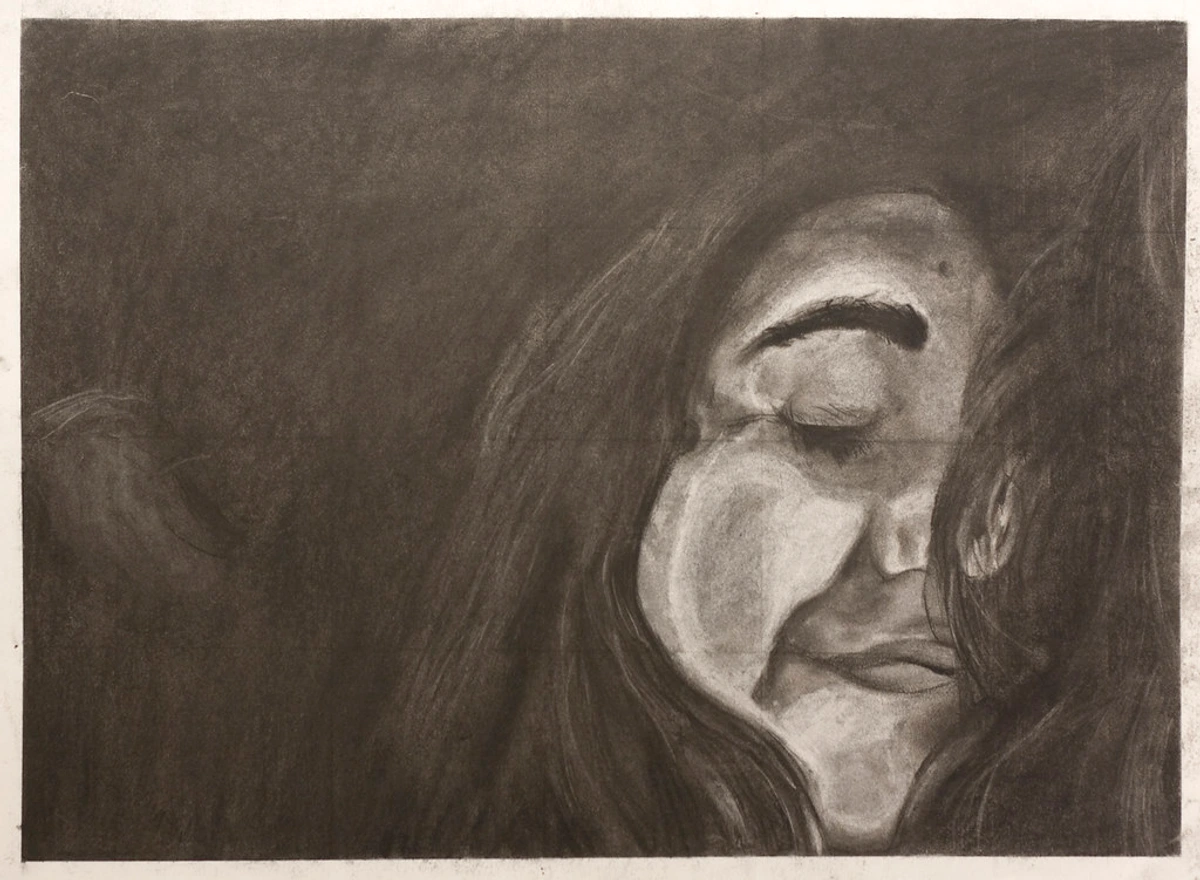

- Naturalism in Emotion, Drapery, and Atmosphere: Figures in Renaissance art expressed a far wider and more nuanced spectrum of human emotions, making their stories relatable and impactful. Techniques like chiaroscuro (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark to create depth and volume, emphasizing form and drama) and sfumato (the subtle blending of colors or tones so that they melt into one another without perceptible transitions, creating a soft, hazy effect, which you can learn more about in what is sfumato in Renaissance art) were masterfully employed to create depth, volume, and a profound sense of psychological presence. Drapery, too, was rendered with meticulous naturalism, falling realistically and hinting at the body beneath, a stark contrast to the abstract, stylized folds of earlier periods. Furthermore, atmospheric perspective was utilized to create the illusion of distance by making objects appear progressively paler, less detailed, and bluer as they receded, mimicking how the atmosphere affects our perception. Beyond these, innovations in pigment use and the mastery of fresco and especially new oil painting techniques allowed for richer colors, greater detail, and more complex light effects, further enhancing the illusion of reality and emotional depth.

Secular Subjects and Classical Echoes: Expanding Art's Horizon

Humanist interest in classical literature and history led to a surge in mythological and historical scenes, greatly expanding art's thematic range beyond solely religious narratives. Artists, commissioned by wealthy patrons, depicted stories from Ovid or Livy, celebrating human drama, heroic tales, and classical ideals. Consider Botticelli's Primavera or The Birth of Venus, which, while mythological, celebrate beauty and life through a Neoplatonic lens, or scenes of Roman history by artists like Mantegna, emphasizing human triumph and civic virtue. This marked a significant expansion of artistic themes, a reflection of the broadened humanist worldview that valued human narrative and ancient wisdom as much as divine revelation.

This reverence for classical culture permeated every aspect of Renaissance art. Artists masterfully incorporated classical architectural elements, mythological themes, and sculptural poses into their work, creating a vibrant dialogue with the past. Principles of classical architecture – order, symmetry, and proportion – became foundational, championed by humanists like Leon Battista Alberti in his influential treatises such as De pictura and De re aedificatoria. These principles informed not just buildings but also the harmonious compositions within paintings, reflecting the ideal of a rationally ordered human world. This wasn't mere imitation; it was a reinterpretation and re-energizing of ancient forms with a new, distinctly Renaissance spirit, adapting and innovating while integrating classical principles into their Christian narratives and secular subjects, creating something wholly new and powerful. Our definitive guide to proportion in art delves deeper into how these principles were applied.

Raphael's The School of Athens is, to my mind, a quintessential visual manifesto of humanism. It's a grand fresco that brings together ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle within a magnificent, classically inspired architectural setting. It celebrates intellectual pursuit, reasoned debate, and the enduring legacy of human thought. The interactions, the vibrant discussions, the sheer intellectual energy emanating from those arches – it screams humanist vibrancy, a timeless tribute to the human mind. Raphael’s masterful use of linear perspective and harmonious composition creates an idealized space for intellectual exchange, embodying the humanist belief in humanity's capacity for rational inquiry and intellectual discourse.

The Enduring Echoes: Humanism's Broader Impact and Legacy Across Fields

Humanism wasn't an isolated academic pursuit; it fundamentally reshaped Renaissance society and profoundly influenced many other fields. Wealthy patrons, like the powerful Medici family in Florence, the Sforza dukes of Milan, and even popes like Julius II, enthusiastically embraced humanist ideals. They commissioned art that celebrated civic pride, individual accomplishment, and classical erudition, moving beyond purely religious themes to include secular subjects and individual portraits. This patronage was absolutely vital, providing artists with the freedom and resources to experiment, innovate, and push the boundaries of artistic expression. Patrons sought not just aesthetic pleasure but also used art to assert their own intellectual authority, cultural sophistication, and to secure their lasting legacy, embodying a form of virtù themselves. To truly understand the dynamics, it helps to consider the broader context of the Renaissance art market.

The humanist emphasis on education and the studia humanitatis also led to the establishment of new schools and fostered a more literate, intellectually curious public. The printing press, by dramatically increasing access to classical texts and humanist treatises (including on art theory), further accelerated this intellectual awakening, allowing artistic ideas to spread much faster across Europe than ever before. This created fertile ground for an unprecedented artistic and intellectual exchange, making these human-centered ideas accessible to a broader audience than just the elite.

Humanism Beyond Italy: The Northern Renaissance

Beyond Italy, humanism subtly permeated the Northern Renaissance, influencing artists like Jan van Eyck and Albrecht Dürer. While maintaining strong religious elements, they also embraced hyper-realism, individual portraiture, and an empirical understanding of the natural world, often integrating meticulous detail and a quiet sense of human dignity into their often spiritual narratives. Dürer's introspective self-portraits, for instance, are profound explorations of individual identity, much like his Italian counterparts, blending Northern precision with Italian humanist ideals of self-discovery and intellectual pursuit. The Northern focus, however, often maintained a stronger connection to Christian devotional practices, integrating humanist observation into their religious narratives, whereas Italian humanism more readily embraced overt classical mythological themes.

Shaping Science, Literature, and the Artist's Status

Artists, once often viewed as mere skilled laborers, began to be revered as intellectual geniuses – polymaths like Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo, who excelled across disciplines, truly embodying the ideal of the Uomo Universale. This elevation of the artist as a creative intellectual profoundly impacted their social status and the very perception of art itself. Moreover, humanism’s emphasis on rational inquiry and empirical observation laid crucial groundwork for the scientific revolution (think of Leonardo's anatomical drawings or Galileo's astronomical observations), while its focus on classical literature spurred new developments in secular poetry, drama, and historical writing, fundamentally altering the literary landscape of Europe. Even in architecture, classical principles of order, symmetry, and proportion, championed by humanists like Leon Battista Alberti, became foundational for many Renaissance buildings, reflecting the ideal of a rationally ordered human world.

Legacy and Modern Reflections

As a quick note, it’s worth remembering that this flourishing of human-centric art eventually met with challenges. Later, during the Counter-Reformation (the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation), the Council of Trent issued decrees on art, sometimes reasserting stricter control over artistic expression. This led to a shift back towards more overtly didactic, emotional, and dramatic religious art, aimed at inspiring piety and countering Protestant critiques, as seen in the intense works of Caravaggio or Bernini. However, many humanist principles of realism, dramatic expression, and the enduring power of the human figure persisted, even within this new context. Baroque artists, for instance, often utilized the heightened drama and emotional intensity championed by humanism, coupled with its naturalism and illusionistic techniques, to serve religious ends, morphing into the dynamic forms of Baroque art and later inspiring movements like Neoclassicism, which explicitly drew on humanist ideals of reason, order, and classical aesthetic perfection. Interestingly, while the Renaissance celebrated physical, lasting masterpieces, the modern art world increasingly grapples with ephemeral digital forms like NFTs. While they represent a new frontier of artistic expression and ownership, the long-term cultural legacy and enduring value of such creations, compared to the centuries-old marble and frescoes of the humanists, is still a matter of contemporary debate, and one that I approach with a healthy dose of critical skepticism.

FAQs: Unpacking Your Questions About Renaissance Humanism

Here, I'll address some of the most common questions that pop up when discussing this fascinating period and its pivotal intellectual movement.

Q: What is the main idea of humanism in Renaissance art?

A: The core idea is a transformative shift from a primary focus on the divine to a profound celebration of human beings – their inherent dignity, immense potential, reason, achievements, and earthly experience. Art became more realistic, anatomically accurate, individual-focused, and drew heavily on classical ideals, emphasizing human agency, the concept of virtù, the Uomo Universale, and the beauty of the human form, all within a framework that often integrated Christian faith.

Q: Was humanism in the Renaissance anti-religious, or was there a distinction between 'Christian' and 'secular' humanism?

A: Not at all, typically. Renaissance humanism was largely compatible with Christian faith, and many prominent humanists were devout Christians. This is often referred to as Christian humanism. Humanists often sought to integrate classical wisdom with Christian theology, emphasizing human dignity as a reflection of divine creation, rather than rejecting God. It was more about expanding the scope of intellectual and artistic focus to encompass human concerns, not replacing religion entirely. While some later developments might be termed 'secular humanism' for their focus solely on human experience without direct religious ties, the dominant form in the Renaissance was deeply intertwined with faith, often seeking to understand God's creation through the study of humanity and the natural world.

Q: Who were some key humanist thinkers and artists that influenced this period?

A: Key thinkers include Petrarch (often considered the "father of humanism"), Pico della Mirandola (Oration on the Dignity of Man), Leonardo Bruni (a prominent civic humanist), Leon Battista Alberti (a true Uomo Universale and influential art theorist), and Erasmus (a leading Christian humanist). Artists like Donatello, Masaccio, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo deeply absorbed and expressed humanist ideals through their revolutionary work in Italian Renaissance art. In the Northern Renaissance, figures like Albrecht Dürer and Jan van Eyck also infused their art with humanist attention to individual detail and empirical observation, adapting these ideals to their unique artistic traditions.

Q: How did humanism fundamentally change art compared to the medieval period?

A: Medieval art frequently featured symbolic, otherworldly depictions with less emphasis on individual realism or emotion. Humanism, in stark contrast, championed naturalism, the innovative use of linear perspective, precise anatomical correctness, foreshortening, and the vivid portrayal of distinct human emotions and personalities. This reflected a powerful belief in human agency and the beauty of the earthly world, leading to more relatable and impactful art. The shift from abstract allegory to tangible reality, from divine focus to human experience, was immense. Art became a window into the human condition, rather than solely a doorway to the divine.

Q: What role did patronage play in fostering humanism in art?

A: Patronage was absolutely crucial. Wealthy individuals, powerful families (like the Medici in Florence), and even popes, inspired by humanist ideals, actively commissioned art. This provided artists with the freedom and financial support to experiment with new techniques, explore secular themes (like mythology and portraits), and celebrate individual achievement and civic pride, directly translating humanist philosophy into visual masterpieces. Without this dedicated financial and intellectual support, driven by the patrons' own desire to express their virtù and leave a lasting cultural legacy, the Renaissance artistic revolution would not have been possible. They used art not just for beauty, but as a powerful tool for self-representation, intellectual discourse, and political messaging.

Q: Why is humanism still profoundly relevant today?

A: For me, humanism's legacy is immense and enduring. It championed critical thinking, the relentless pursuit of knowledge, the inherent dignity of the individual, and the empowering idea that humanity is capable of extraordinary achievement. These are timeless values that continue to inspire education, ethical thought, artistic creation, and societal progress. When I'm working on my own art, whether it's abstract or more expressive, I often reflect on this timeless quest for meaning, for understanding the human condition, and for expressing that. It's a journey that gained incredible momentum during the Renaissance, and it’s a journey we're still deeply embedded in. You can see how these themes resonate in contemporary art and culture, often touching upon similar aspects of what it means to be human, to explore emotion, and to create something that speaks to universal experiences. Humanism, in many ways, laid the philosophical groundwork for concepts like individual rights, scientific inquiry, and the liberal arts education that still shape our world. Perhaps you can even see a flicker of that Renaissance spirit in my contemporary art or by visiting my Den Bosch museum. You can also follow my timeline to see how my own artistic journey evolves.

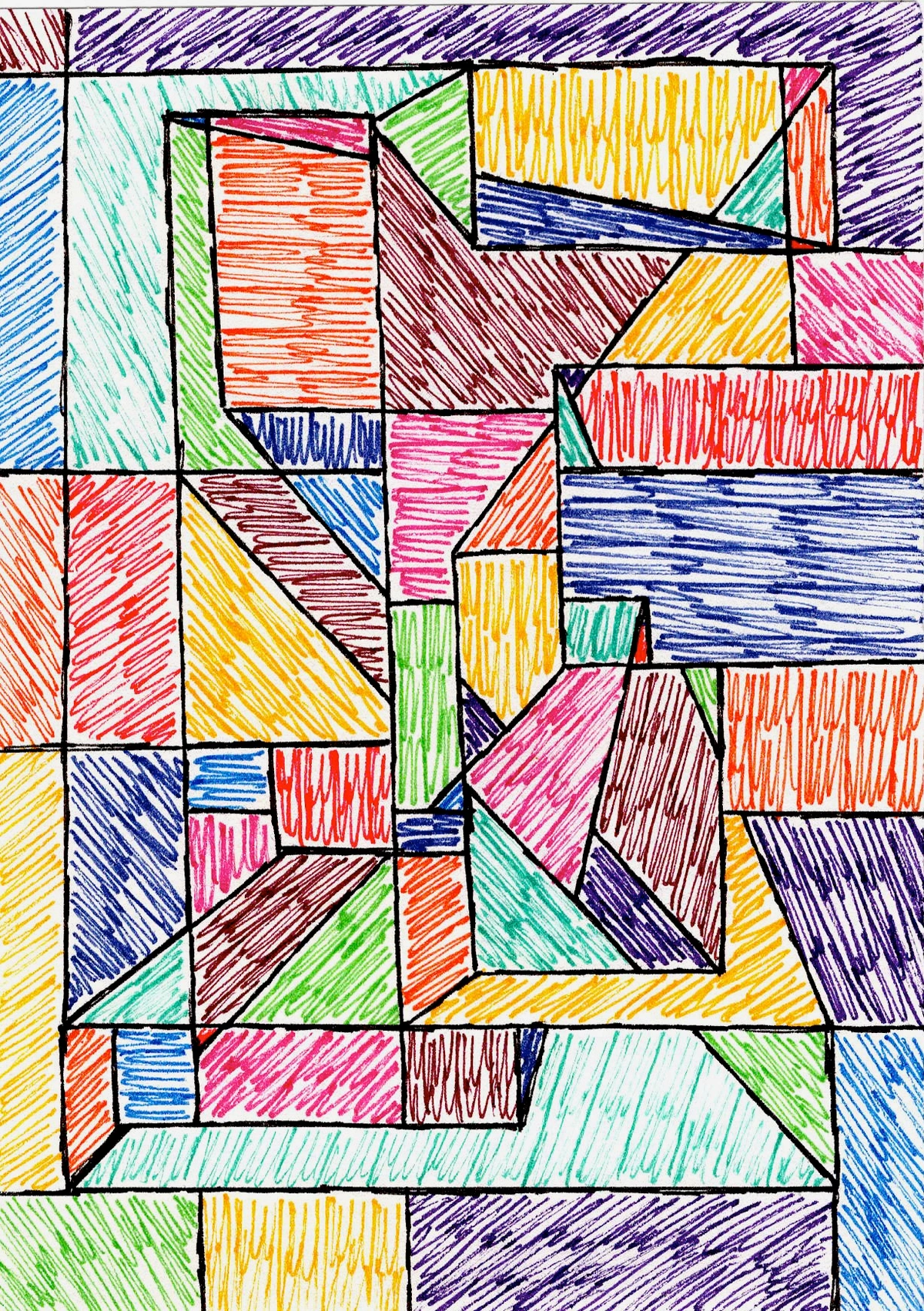

My Enduring Reflection on Human Potential and Its Artistic Echoes

So, what began as a casual observation in a museum, that almost physical jolt of recognition years ago, has blossomed into a profound, ongoing appreciation for the transformative power of ideas. Humanism in Renaissance art is far more than a historical chapter; it's a vibrant, essential conversation about what it truly means to be human. It’s about that undeniable spark within us – our incredible capacity for creation, for introspection, for empathy, for shaping our world, and yes, even for grappling with its complexities and "messiness." When I look at a piece of art, whether it’s Donatello's Saint George, Raphael’s The School of Athens, or the vibrant, abstract pieces I create in my studio, like this one, I see not just pigment or marble, but a reflection of ourselves – our struggles, our triumphs, our dreams, and that endless, fascinating quest to define what it means to be truly human. Humanism, with its daring self-portrait of humanity, challenged us to celebrate our potential, understand our world, and leave a lasting mark. And that, my friends, is a legacy worth celebrating, studying, and carrying forward in our own creations and explorations. What will your contribution be to humanity's ongoing self-portrait? And how will you express that?