Unearthing the Renaissance Art Market: Patronage, Power, and Enduring Value

As an artist, I often wonder: how did the Renaissance art market truly function? Join me on a deep dive into patronage, artist workshops, and the fascinating economics behind history's masterpieces, connecting past valuation with present-day collecting.

Beyond Beauty: A Quirky Dive into the Renaissance Art Market

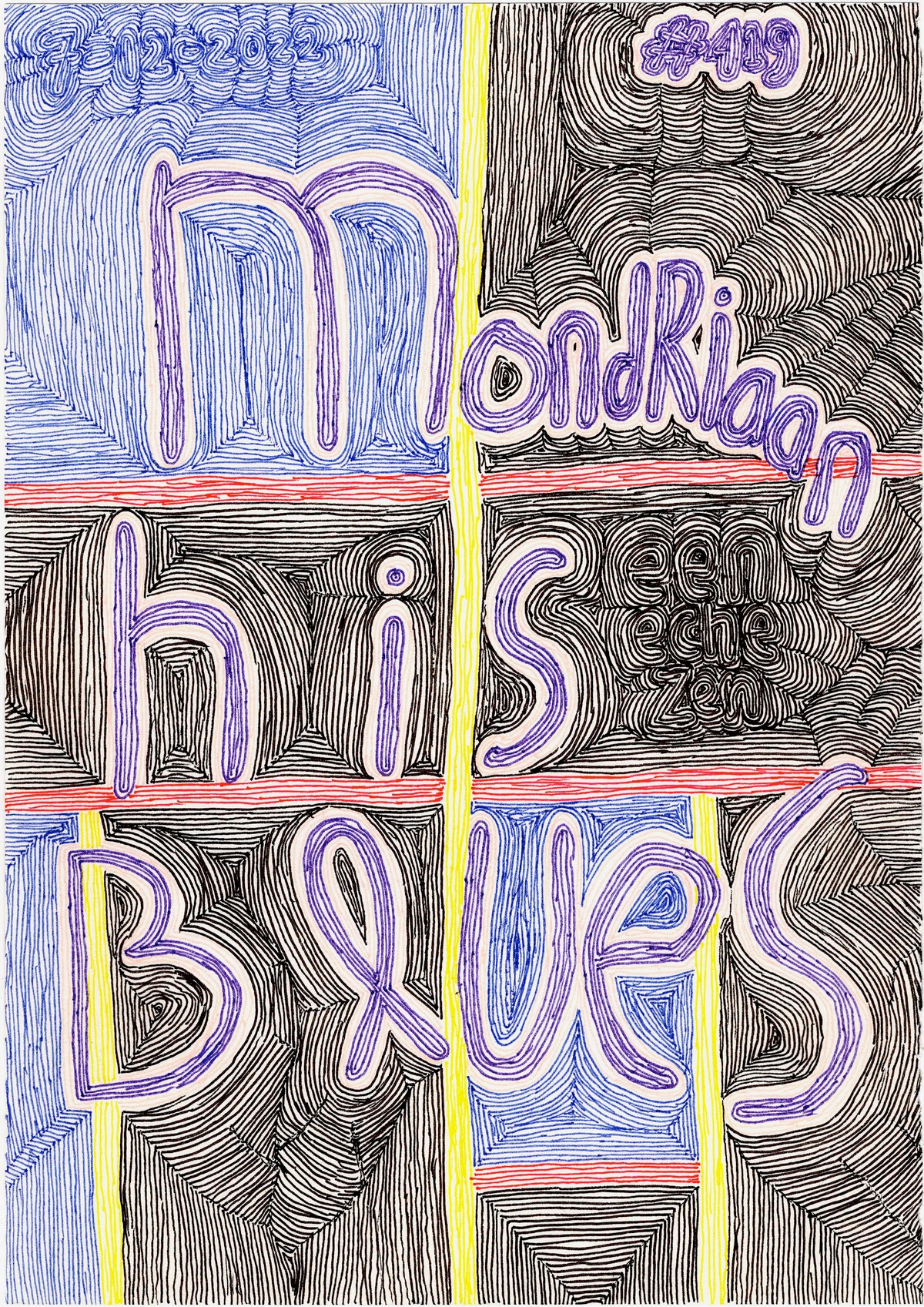

You know, sometimes I find myself staring at one of my abstract pieces – perhaps a swirl of blues and yellows, lines intersecting in a rhythm that feels just right to me – and I'll catch myself wondering: how would this have been valued, say, 500 years ago? It's a silly thought, really, given the radical differences in art and economics between then and now. But it does lead me down a rabbit hole of curiosity, especially about something as foundational as the Renaissance art market. What drove its engine? Who decided what was 'good' or 'worthwhile'? As someone creating art today, these questions are surprisingly resonant.

It certainly wasn't as simple as clicking a button on my website to purchase a print, that's for sure. The whole system was a beast of its own, deeply intertwined with power, religion, and social standing. So, come with me, let's pull back the curtain a bit and poke around, shall we?

The Patronage Puzzle: Who Held the Purse Strings?

When we talk about Renaissance art, the first word that should pop into your head (after, you know, 'art') is patronage. This wasn't just a casual transaction; it was the lifeblood of artistic creation. Forget about today's gallery system or individual collectors buying pieces off the wall. Back then, most art was commissioned. Think of it like this: if you wanted a masterpiece, you didn't just find one; you ordered one.

And who were these powerful patrons? Popes, cardinals, dukes, wealthy merchants – the rockstars of their day, really. Families like the Medici in Florence, or the Sforza in Milan, used art as a billboard for their piety, power, and prestige. I mean, imagine commissioning a painting, not just because you like the colors (though I'm sure they did), but because it solidified your family's status in society, or, you know, helped ensure your spot in the afterlife. Pretty high stakes for a painting, right? Take the Medici, for instance, commissioning Botticelli's Primavera or The Birth of Venus not just for beauty, but to symbolize their humanist ideals and cultural sophistication. Even powerful guilds and confraternities acted as patrons, commissioning grand public works to enhance their civic standing and express collective devotion.

This system meant artists often worked on specific projects, sometimes over many years, for a single, influential client. It dictated the subject matter (often religious, reflecting the era's profound faith), the size, even the materials used. It's a far cry from the freedom many contemporary artists (myself included, thankfully) often enjoy now. If you're keen to explore the artistic output of this period, my article on the ultimate guide to Renaissance art offers a great overview.

Artists: Not Always Starving, Often Savvy Businessmen

Now, about the artists themselves. I think there's this romanticized image of the starving artist, toiling away in obscurity. While some might have struggled, many prominent Renaissance artists were shrewd businessmen and respected craftsmen. Take someone like Leonardo da Vinci, for example – he wasn't just a painter; he was an inventor, an engineer, a bit of a polymath. His skills were highly sought after, and he knew his worth. Raphael, too, was known for his highly efficient workshop, capable of churning out numerous commissions under his masterful direction, while Titian was a particularly astute negotiator, commanding high prices from kings and emperors across Europe.

Artists ran workshops, essentially small businesses with apprentices and assistants. They trained young talent (sometimes from childhood!), managed commissions, sourced expensive materials like ultramarine pigment (derived from lapis lazuli, more precious than gold at one point, imagine that! Makes my current pigment budget feel like pocket change, though I'm grateful for it), and negotiated prices. The fee often covered not just the artist's labor but also the cost of materials and the work of their studio. It's a whole different ballgame compared to my own journey, which you can read about on my timeline.

What Made Art 'Valuable' Back Then?

This is where it gets really interesting for me. When I create a piece like this abstract composition you see here, its value is often in its aesthetic appeal, emotional resonance, or perhaps its conceptual depth – often intangible qualities that connect with a viewer. But in the Renaissance, while beauty was certainly appreciated, value was often far more tangible and layered. We're talking:

- Materials: Gold leaf, expensive pigments, large panels or frescoes – these were direct costs that contributed to the price. Think of the sheer amount of gold leaf used in an altarpiece, directly adding to its cost and visual splendor. The more precious the materials, the higher the cost, and often, the higher the perceived value.

- Labor & Skill: The sheer amount of time and skill required for complex compositions, detailed figures, or large-scale Renaissance sculpture played a huge role. Artists like Michelangelo were paid handsomely for their unparalleled talent, their name adding immense prestige to any work.

- Subject Matter: Religious depictions were paramount, often for churches and private devotion, carrying profound spiritual significance. But portraits and mythological scenes also carried significant cultural and social weight. The significance of the subject could amplify the work's importance and, therefore, its cost.

- Size & Location: A grand altarpiece for a cathedral obviously commanded a higher price than a small devotional piece for a private chapel. The intended placement – a public square, a private palace, a church – often determined the scale and ambition of the work, and thus its price.

So, it wasn't just about the 'art' of it. It was about investment, spiritual merit, and a very public display of power. Art's economic value was inextricably linked to its social, political, and religious function, a stark contrast to today's market where an artist's signature alone can sometimes dictate millions.

How was Renaissance art experienced?

Beyond commissioning and creating, how was this art actually seen? Much of it was public – grand frescoes in churches and civic buildings, altarpieces, and sculptures in town squares – intended to educate, inspire, and project power to a broad audience. For the elite, private works adorned palaces, chapels, and especially studioli – small, highly personal studies where humanist scholars would contemplate their collections in a more intimate setting. The viewing experience was often a blend of spiritual devotion, intellectual engagement, and social spectacle.

The Dawn of the Art Collector (Kind Of)

While patronage dominated, a nascent form of art collecting began to emerge, particularly towards the later Renaissance. Wealthy individuals, often humanists or scholars, started acquiring art not just through commission but sometimes through purchase, appreciating works for their artistic merit or historical significance, not solely for their immediate religious or political utility. Isabella d'Este, for example, a powerful Marchesa of Mantua, was renowned for her exquisite studiolo, filled with commissioned and acquired works by leading artists, collected for their aesthetic and intellectual value.

These collections, often housed in these private studioli, hinted at a future where art would be bought and sold more freely, eventually leading to the art market we recognize today. It was a slow shift, a ripple in the vast ocean of patronage, but a significant one nonetheless.

My Thoughts Today: Echoes of the Past

Thinking about all this makes me appreciate the contemporary art market, for all its complexities, just a little bit more. I mean, my art is bought by individuals who connect with its energy, its color, its form – a far more personal transaction, often directly with me. It’s less about asserting power and more about personal expression and connection, both for me as the artist and for you as the collector. Yet, I wonder if a part of that ancient desire for prestige, for something truly unique and valued, still lingers when someone decides to bring a piece of art into their home.

It’s a different world, yes, but the human desire to create, appreciate, and even own beauty, well, that's truly timeless. And sometimes, walking through an exhibition, maybe even at a place like my own museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, I can almost feel the echoes of those Renaissance patrons, their grand visions, and the artists who brought them to life.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Renaissance Art Market

How did Renaissance artists get paid?

Renaissance artists were primarily paid through commissions from wealthy patrons (such as the Church, royalty, noble families, and successful merchants). They would often receive an initial deposit, followed by payments in installments as the work progressed, with the final payment upon completion. The contract typically specified the subject, materials (often including expensive pigments like gold and ultramarine), size, and deadline.

Was there an 'art market' in the Renaissance like today?

Not in the modern sense of galleries, auctions, and speculative buying. The Renaissance market was largely driven by commissions and patronage, where art was custom-ordered. While there were some dealers and secondary sales, it was a much smaller, less organized component compared to the direct patron-artist relationship.

Who were the biggest patrons of Renaissance art?

The most prominent patrons included:

- The Catholic Church: Popes and cardinals commissioned countless religious works for cathedrals, chapels, and private devotion, often as a means of expressing piety and authority.

- Noble Families: Families like the Medici in Florence, the Sforza in Milan, and the Borgia in Rome used art to display their wealth, power, and cultural sophistication, often commissioning works with political or personal iconography.

- Guilds and Confraternities: Professional associations and religious brotherhoods commissioned public works (like altarpieces for their chapels or sculptures for public squares) to enhance their civic standing and piety.

How was art valued during the Renaissance?

Art valuation was complex. It considered:

- Cost of Materials: Expensive pigments (like ultramarine), gold leaf, and large canvases/panels directly increased cost, making a work inherently more valuable.

- Labor and Skill: The artist's reputation, the complexity of the design, and the time invested were crucial. Master artists commanded higher fees due to their unique talent.

- Size and Scale: Larger, more ambitious works for prominent locations commanded higher prices, reflecting the effort and materials involved.

- Subject Matter: The religious, political, or social significance of the work could also add value, as it fulfilled specific functions for the patron.

Essentially, art was seen as both a spiritual investment and a tangible asset, often a public declaration of one's status.