Italian Renaissance Art: A Beginner's Personal Guide & My Take

Dive into Italian Renaissance art with me! A personal, engaging guide covering key artists, characteristics, and why this timeless era still fascinates a modern artist.

Italian Renaissance Art: My Personal Journey into a Timeless Era

Sometimes, a period in history just clicks. For me, the Italian Renaissance wasn't an immediate love affair; it was a slow burn, a gradual unveiling of a world so rich with innovation and human spirit that it eventually captivated me entirely. It's like finding that perfect, slightly worn bookstore where every shelf whispers a new story, and you just know you're going to spend hours getting lost. This era, a true explosion of creativity and intellect, laid the foundations for so much of what we value in Western culture, a concept so grand it still makes my head spin a little when I think about it. It’s a period often framed as a rediscovery, but it was so much more: a bold reimagining of what humanity could achieve when fueled by curiosity, classical wisdom, and a fierce drive to create. This era, a true watershed moment in Western history, marked a profound departure from the medieval mindset, ushering in a new reverence for human achievement and artistic innovation. Its influence continues to shape our understanding of art, science, and philosophy even today. Okay, so I’m going to be completely honest with you. For a long time, the words "Italian Renaissance Art" conjured up images of dusty museum halls, overly serious paintings, and a feeling that I probably wasn’t smart enough to truly "get" it. It felt… intimidating, you know? Like walking into a really fancy restaurant where everyone seems to know which fork to use, and I’m just trying not to spill my water. But you know what? That initial feeling of awe and slight bewilderment is part of the charm – it's the feeling of standing before something truly ambitious, something that dared to redefine beauty and human potential. It's like staring at a really complex piece of music and thinking, "How did they do that?" The answers are always more human and fascinating than you'd expect. And that's exactly what I hope to share with you here: a journey through the human stories, the groundbreaking ideas, and the sheer audacity that made the Italian Renaissance so transformative.

But then, something shifted. I started looking closer, past the initial awe and the sheer scale of it all, and began to see the stories, the humanity, and the sheer audacious innovation that defines this period. It was a rebirth, not just for Europe, but for my own artistic understanding, sparking a profound shift in how I perceived art, history, and the very act of creation. So, let’s peel back those layers together, shall we? This isn't your average art history textbook; this is more like a chat over coffee about why this stuff still moves me, and why it absolutely should move you too. The Italian Renaissance wasn't just a moment in time; it was a seismic shift, a profound cultural awakening that, spurred by a renewed interest in classical antiquity and a burgeoning intellectual movement, laid the groundwork for so much of what we consider art and culture today. It was a period when Europe truly began to look back to its classical roots, not to merely imitate, but to innovate, creating something entirely new and breathtaking from the ashes of medieval thought. From grand cathedrals to intimate portraits, it redefined beauty, human potential, and the very role of the artist, initiating a fundamental re-evaluation of humanity's place in the cosmos that continues to resonate today. It's a story worth telling, and experiencing.

Renaissance Sculpture: Bringing Stone to Life

While painting often gets the spotlight, Renaissance sculpture was equally revolutionary, marking a profound break from the stylized forms of the Middle Ages. Sculptors, much like painters, embraced humanism and classical ideals, aiming for a naturalistic portrayal of the human form, imbued with emotion and narrative power. Think of Lorenzo Ghiberti’s gilded bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery, often called the “Gates of Paradise” – a true marvel of perspective and narrative complexity that signaled a new era in sculptural storytelling, all before the major titans even arrived! Ghiberti spent over two decades crafting these magnificent doors, featuring ten panels that depicted biblical scenes with an unprecedented illusion of depth and classical grandeur, almost like paintings in bronze. The East Doors, specifically, are a testament to his virtuosity, where Old Testament stories unfold with narrative fluidity and innovative spatial effects, truly earning their famous nickname from Michelangelo himself. They were like the opening act, setting the stage for what was to come, hinting at the sculptural masterpieces that would soon emerge from workshops across Italy, showcasing a newfound expressive power and anatomical realism. Figures began to stand freely in space, often in contrapposto – a naturalistic pose where the weight is shifted to one leg, giving the figure a dynamic, lifelike quality, directly inspired by ancient Greek and Roman statues. Sculptors also mastered schiacciato, a technique of 'flattened relief' where the carving is so shallow that it relies on subtle changes in plane and line to create an illusion of great depth and distance, almost like a drawing on marble. Imagine trying to paint a landscape with just tiny bumps on a surface – that's the genius of schiacciato, making marble breathe with distant horizons and crowded figures, a truly mind-bending optical trick! Materials like marble and bronze were worked with incredible skill, allowing for intricate details and a sense of volume and presence that was truly breathtaking. From monumental public commissions to delicate private reliefs, Renaissance sculpture conveyed dignity, psychological depth, and a newfound celebration of the human body as a vessel of both physical and spiritual beauty. It was an art form that quite literally brought stone to life, making viewers feel a direct connection to the figures depicted. From monumental public commissions to delicate private reliefs, Renaissance sculpture conveyed dignity, psychological depth, and a newfound celebration of the human body as a vessel of both physical and spiritual beauty. And of course, the groundbreaking work of artists like Donatello, whose raw emotional intensity and psychological depth in bronze and marble truly pushed the boundaries, set a powerful precedent for future sculptors like Michelangelo. His 'St. George,' for instance, embodies a quiet defiance and inner strength that speaks volumes, while his 'Judith and Holofernes' explodes with dramatic narrative and visceral power, showing the full range of human emotion in rigid materials.

What Even Is Renaissance Art? A Quick Chat

"Renaissance" means "rebirth" in French, and honestly, that's the perfect way to describe it. After what we generally call the Middle Ages – a period some people unfairly label the "Dark Ages," though it was far from artistically barren, merely different in its focus, focusing more on symbolic representations and spiritual narratives rather than naturalistic human forms (but that's a whole other conversation, perhaps one for a deep dive into the history of art guide or even the influence of Byzantine art on Renaissance painting!) – Europe felt like it was waking up. The shift wasn't a rejection of faith, but a broadening of focus, where human experience began to share the canvas with the divine, a bit like realizing there are more colors in your palette than you first thought. This wasn't a sudden jolt, but a gradual, exhilarating dawn, ignited by a new sense of intellectual curiosity and a changing worldview. It was like emerging from a long, restful sleep and realizing the world was a canvas just waiting for a fresh coat of vibrant ideas and breathtaking forms. The groundwork for this awakening, however, was subtly laid by economic changes and increased trade, which led to a demand for new forms of cultural expression. Think of how silk roads and burgeoning maritime trade routes brought not just goods, but also new ideas and wealth, setting the stage for patrons to invest in art on an unprecedented scale. There was a renewed interest in the classical ideas of ancient Greece and Rome: their philosophy, their art, their architecture, and even their political structures. It was like everyone collectively decided, "Hey, those guys had some really good ideas, let's bring them back, but with our own spin!" This wasn't mere imitation, but a vibrant conversation across centuries, where the past provided a blueprint for future glory, blending classical aesthetics with Christian spirituality.

This wasn't just about copying old statues, though. It was about putting humans at the center of the universe, a concept called humanism. Imagine, after centuries of art largely dedicated to God and the saints, artists suddenly felt permission – even inspiration – to celebrate human potential, emotion, and achievement. This new intellectual movement didn't reject faith, but rather sought to harmonize it with reason and human experience, drawing wisdom from classical texts from thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, and emphasizing a robust education in the liberal arts. Humanists believed that through the study of these classical works, individuals could cultivate virtue, eloquence, and a deeper understanding of the world, fostering active and engaged citizenship. Figures like Coluccio Salutati and Leonardo Bruni in Florence championed civic humanism, linking classical learning to active participation in the republic, directly impacting the city's intellectual and artistic vibrancy. They saw the public square and the artist's studio as interconnected, each a place where civic virtue could be expressed and nurtured. This emphasis on individual growth and societal contribution was truly revolutionary. It's a bit like my own journey into art – you start by learning from what came before, then you find your own voice, right? It's about building on tradition, not just replicating it. This shift meant a new focus on individual portraits, mythological tales, and everyday life, all imbued with a profound respect for human dignity. Think of it: your local baker could now commission a portrait, celebrating his own individual existence, not just his saintly namesake! If you're curious about the broader sweep of the era, my friends over at the ultimate guide to Renaissance art have a fantastic overview. This era marked a profound move from the symbolic, almost abstract representations of the Middle Ages to a startlingly realistic depiction of the world as seen through human eyes, often with a newfound emphasis on narrative clarity and emotional expression. Beyond the visual arts, humanism profoundly impacted literature, philosophy, and political theory, laying the intellectual foundations for much of the modern world.

The Social Canvas: Why Art Flourished

But why then? Why did this rebirth happen in Italy, and why was art so central to it? Well, it wasn't just a sudden burst of creativity. It was fueled by a unique confluence of factors. Italy, particularly cities like Florence, Venice, and Rome, was a hotbed of economic prosperity, thanks to flourishing trade, banking, and strategic geographic locations. This wealth allowed powerful merchant families (like the legendary Medici in Florence), noble courts (such as the Sforza family in Milan or the Este family in Ferrara), and the Papacy itself, to become incredible patrons. They commissioned lavish artworks not just for devotion, but also as symbols of their immense power, status, and intellectual sophistication, often using art as a form of political propaganda and cultural display. For instance, the Doges of Venice used art to project the glory and independence of their maritime republic, commissioning grand narrative paintings for the Doge's Palace. Think of it: if you had the money, wouldn't you want to surround yourself with beauty and innovation, and leave a lasting legacy? This kind of patronage wasn't just about showing off; it created a vibrant, competitive environment where artists were constantly pushed to innovate and surpass each other, leading to an explosion of artistic genius. The Medici, for instance, didn't just bankroll artists; they hosted them, nurtured them, and even shaped their careers, seeing art as an essential expression of their family's intellectual and political power. Cosimo de' Medici, known as the 'Pater Patriae' (Father of the Fatherland), was a key early patron, sponsoring architects like Brunelleschi and sculptors like Donatello, laying the groundwork for Florence's artistic dominance. His grandson, Lorenzo the Magnificent, continued this legacy, famously fostering young talents like Michelangelo in his household and creating the Platonic Academy, a center for Neo-Platonic philosophy. They even ran academies, providing artists with classical models and intellectual discourse. Pope Julius II in Rome, on the other hand, was a warrior pope who used art on a monumental scale to project the authority and grandeur of the Papacy, literally rebuilding Rome and filling it with masterpieces to solidify his legacy. Beyond these titans, families like the Sforza in Milan and the Este in Ferrara also built magnificent courts, attracting artists and intellectuals, creating a mosaic of artistic hubs across Italy. This patronage system, often complemented by the structure of artists' workshops and powerful guilds, created a competitive, yet incredibly fertile, environment for artists to push boundaries and experiment like never before, leading to an explosion of artistic genius. Guilds, like the Guild of St. Luke, provided training, regulated quality, and offered a social safety net, ensuring a steady stream of skilled artisans.

The Florentine Spark: Where It All Began

If the Renaissance was a grand party, Florence was absolutely the dazzling host city. This wasn't a coincidence. Wealthy merchant families, like the Medici, became incredible patrons of the arts. They built magnificent palaces (like the Palazzo Medici Riccardi), sponsored brilliant artists (hosting figures like Botticelli and Michelangelo in their own household), and even founded academies for intellectual discourse (such as the Platonic Academy), fostering an environment where philosophy, art, and science intertwined. Florence, a hub of banking, commerce, and textiles, had accumulated immense wealth, and its leading families were eager to display their prosperity and influence not just through politics, but through beauty and intellect. They weren't just commissioning pretty altarpieces; they were investing in genius, seeing art as a way to show off their power, piety, and cultural sophistication. Imagine having that kind of budget! Lorenzo de' Medici, often called 'Lorenzo the Magnificent,' epitomized this era, fostering a dazzling intellectual and artistic environment that attracted the brightest minds. It makes my art studio feel positively modest, though I suppose my goal isn't quite the same as commissioning a fresco for a cathedral ceiling. The city's intense civic pride also played a huge role, leading to monumental public commissions like the competition for the Florence Cathedral's dome and the Baptistery doors, which spurred innovation and artistic rivalry. Brunelleschi's daring construction of the dome without traditional scaffolding, for example, became a symbol of Florentine ingenuity and engineering prowess. He used an innovative double-shell design, employing a herringbone brick pattern and horizontal stone and wood chains to counteract outward thrust, a feat that had not been achieved since antiquity, earning him immense fame and respect. It was a monumental challenge, and his solution was a testament to Renaissance problem-solving. The construction of masterpieces like the Ponte Vecchio and the Palazzo della Signoria also reflected this pride, making the city itself a testament to its citizens' ambition and artistic vision. Beyond these, the Uffizi Gallery, originally designed as administrative offices, and the Palazzo Pitti, a grand ducal palace, stand as further testaments to Florence's enduring architectural and artistic legacy. If the Renaissance was a grand party, Florence was absolutely the dazzling host city. This wasn't a coincidence. Wealthy merchant families, like the Medici, became incredible patrons of the arts. They built magnificent palaces (like the Palazzo Medici Riccardi), sponsored brilliant artists (hosting figures like Botticelli and Michelangelo in their own household), and even founded academies for intellectual discourse (such as the Platonic Academy), fostering an environment where philosophy, art, and science intertwined. Florence, a hub of banking, commerce, and textiles, had accumulated immense wealth, and its leading families were eager to display their prosperity and influence not just through politics, but through beauty and intellect. They weren't just commissioning pretty altarpieces; they were investing in genius, seeing art as a way to show off their power, piety, and cultural sophistication. Imagine having that kind of budget! Lorenzo de' Medici, often called 'Lorenzo the Magnificent,' epitomized this era, fostering a dazzling intellectual and artistic environment that attracted the brightest minds. It makes my art studio feel positively modest, though I suppose my goal isn't quite the same as commissioning a fresco for a cathedral ceiling. The Palazzo Pitti, another Medici palace, later became a grand symbol of Florentine power and a repository for incredible art. The Uffizi Gallery itself, initially an administrative office building, now houses an unparalleled collection of Renaissance masterpieces, a testament to Florence's enduring artistic legacy. The city's intense civic pride also played a huge role, leading to monumental public commissions like the competition for the Florence Cathedral's dome and the Baptistery doors, which spurred innovation and artistic rivalry. Imagine the buzz in the city as artists competed for these prestigious projects, each striving to outdo the other in skill and vision! The construction of masterpieces like the Ponte Vecchio and the Palazzo della Signoria also reflected this pride, making the city itself a testament to its citizens' ambition and artistic vision. The famous competition for the Baptistery doors in 1401, won by Lorenzo Ghiberti over Filippo Brunelleschi, is a perfect example of this intense artistic ferment, pushing sculptors to new heights of technical and narrative skill, not just for personal glory but for the glory of Florence itself. Both submitted bronze panels depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac, and while Brunelleschi's was dramatic, Ghiberti's displayed a more classical grace and technical finesse that won the commission – a decision that, ironically, freed Brunelleschi to focus on architecture, leading to the dome!

If you ever find yourself wandering through Florence, it’s like stepping directly into a living museum. Seriously, it's an experience. The city itself became a canvas, reflecting the intense civic pride and competitive spirit among its citizens and families. For a deeper dive into why Florence was the place to be, check out this art lover's guide to Florence.

And while we're talking about Florence's magic, you simply can't ignore Filippo Brunelleschi. Primarily an architect, his revolutionary dome for the Florence Cathedral wasn't just an engineering marvel; it embodied the Renaissance spirit of innovation and daring. He solved a problem that had baffled architects for centuries, showcasing the era's blend of practical ingenuity and classical knowledge. His studies in mathematics and optics directly led to the "rediscovery" of linear perspective, a technique that would utterly transform painting and sculpture, allowing for the creation of convincing three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. He not only theorized it but practically demonstrated it through famous experiments, like the one involving a mirror and the Florence Baptistery, literally showing how a painting could perfectly match reality from a specific viewpoint, providing a blueprint that artists like Masaccio and Alberti would swiftly adopt. It's like he handed artists the keys to a whole new dimension, offering a scientific framework for artistic representation! His genius lay in bridging art and science, making the invisible rules of optics visible and usable for artists, transforming art from a craft into a true intellectual pursuit.

And while we're talking about Florence's magic, you simply can't ignore Filippo Brunelleschi. Primarily an architect, his revolutionary dome for the Florence Cathedral wasn't just an engineering marvel; it embodied the Renaissance spirit of innovation and daring. He solved a problem that had baffled architects for centuries, showcasing the era's blend of practical ingenuity and classical knowledge. His studies in mathematics and optics directly led to the "rediscovery" of linear perspective, a technique that would utterly transform painting and sculpture, allowing for the creation of convincing three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. He not only theorized it but practically demonstrated it through famous experiments, like the one involving a mirror and the Florence Baptistery, literally showing how a painting could perfectly match reality from a specific viewpoint, providing a blueprint that artists like Masaccio and Alberti would swiftly adopt. It's like he handed artists the keys to a whole new dimension, offering a scientific framework for artistic representation! His genius lay in bridging art and science, making the invisible rules of optics visible and usable for artists, transforming art from a craft into a true intellectual pursuit. It's like he handed artists the keys to a whole new dimension, offering a scientific framework for artistic representation!

And while we're talking about Florence's magic, you simply can't ignore Filippo Brunelleschi. Primarily an architect, his revolutionary dome for the Florence Cathedral wasn't just an engineering marvel; it embodied the Renaissance spirit of innovation and daring. He solved a problem that had baffled architects for centuries, showcasing the era's blend of practical ingenuity and classical knowledge. His studies in mathematics and optics directly led to the "rediscovery" of linear perspective, a technique that would utterly transform painting and sculpture, allowing for the creation of convincing three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. He not only theorized it but practically demonstrated it through famous experiments, like the one involving a mirror and the Florence Baptistery, literally showing how a painting could perfectly match reality from a specific viewpoint, providing a blueprint that artists like Masaccio and Alberti would swiftly adopt. It's like he handed artists the keys to a whole new dimension, offering a scientific framework for artistic representation! His genius lay in bridging art and science, making the invisible rules of optics visible and usable for artists, transforming art from a craft into a true intellectual pursuit. It's like he handed artists the keys to a whole new dimension, offering a scientific framework for artistic representation!

Other Italian Powerhouses: Rome and Venice

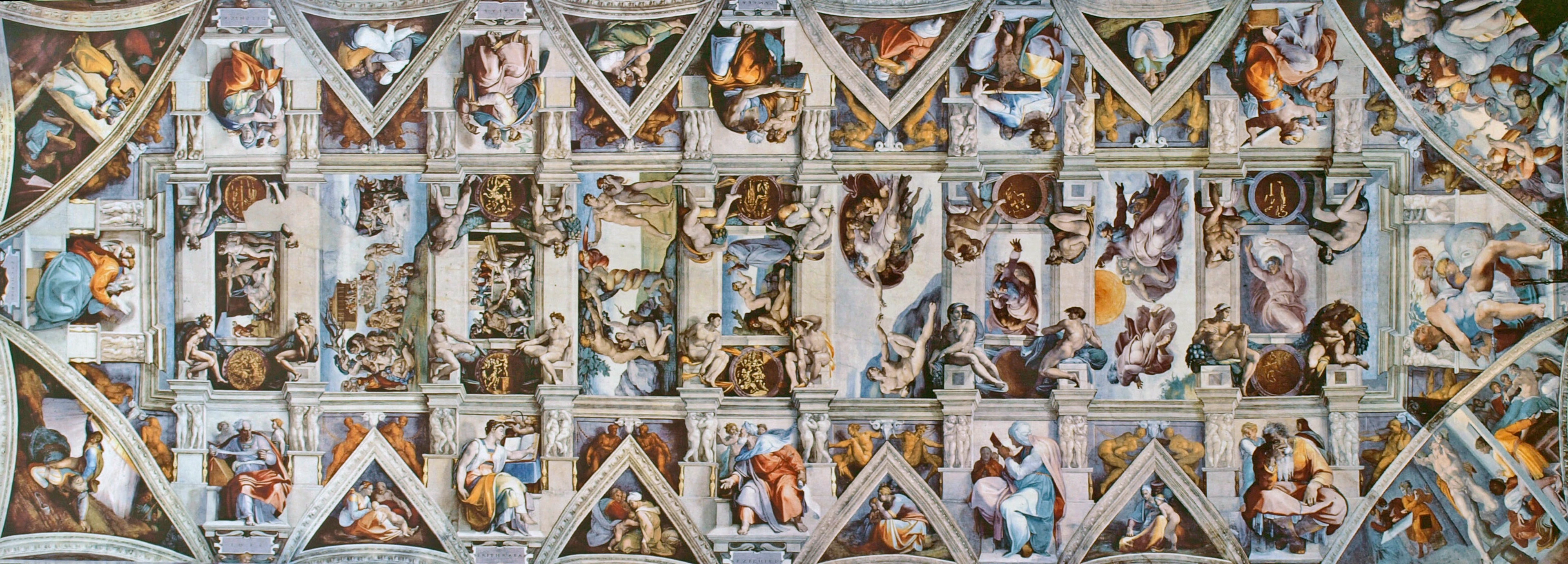

While Florence might have sparked the flame, the Renaissance wasn't confined to its walls. Rome quickly became another epicenter, especially during the High Renaissance. Popes like Julius II were just as ambitious, if not more so, than the Medici. They actively sought to re-establish Rome as the spiritual and artistic capital of the Christian world, commissioning monumental works for the Vatican, drawing in masters like Michelangelo (Sistine Chapel, hello! and the awe-inspiring dome of St. Peter's Basilica) and Raphael (with his magnificent frescoes in the Vatican's Stanze della Segnatura, like 'The School of Athens' which brilliantly brought together ancient philosophers and artists). Rome's ancient ruins also provided direct inspiration, creating a powerful link to classical grandeur and offering a tangible connection to the imperial past that the Popes aimed to emulate. It was a city undergoing its own magnificent rebirth, transforming from a medieval town into a dazzling capital of art and faith, with its urban fabric becoming a testament to papal power and artistic patronage.

While Florence might have sparked the flame, the Renaissance wasn't confined to its walls. Rome quickly became another epicenter, especially during the High Renaissance. Popes like Julius II were just as ambitious, if not more so, than the Medici. They actively sought to re-establish Rome as the spiritual and artistic capital of the Christian world, commissioning monumental works for the Vatican, drawing in masters like Michelangelo (Sistine Chapel, hello! and the awe-inspiring dome of St. Peter's Basilica) and Raphael (with his magnificent frescoes in the Vatican's Stanze della Segnatura, like 'The School of Athens' which brilliantly brought together ancient philosophers and artists). Rome's ancient ruins also provided direct inspiration, creating a powerful link to classical grandeur and offering a tangible connection to the imperial past that the Popes aimed to emulate. It was a city undergoing its own magnificent rebirth, transforming from a medieval town into a dazzling capital of art and faith, with its urban fabric becoming a testament to papal power and artistic patronage. The excavation of classical sculptures like the Laocoön group in 1506, for instance, had a profound impact on artists like Michelangelo, directly inspiring his powerful, dynamic figures. The sheer drama and emotional intensity of the Laocoön, rediscovered during a time of intense artistic fervor, fueled a new wave of expressive realism.

And then there's Venice. The Venetian Renaissance had its own distinct flavor, often characterized by a love of rich colors, sensual forms, and the interplay of light and shadow, perhaps influenced by the city's unique luminous quality and its connection to the East. Artists like Titian, Giorgione, and Veronese emerged from this vibrant, mercantile city, creating works that celebrated worldly beauty and opulent textures. They were masters of color (colorito over Florence's disegno, which emphasized drawing and intellectual design), capturing the luminous quality of their city, often depicting sensuous nudes, grand festivals, and dramatic religious scenes with a unique emphasis on light and atmospheric effects. Imagine the light shimmering on the canals, reflected in a canvas full of deep reds and blues – it’s a whole different vibe, but just as breathtaking. Venetian architecture, with its Byzantine and Gothic influences, also developed a unique, ornate style, often incorporating rich marbles and intricate details that reflected the city's wealth and cosmopolitan nature. Artists like Giovanni Bellini, an earlier Venetian master, laid crucial groundwork for this distinctive style, influencing generations with his serene Madonnas and innovative use of landscape, often featuring soft, atmospheric light that seemed to glow from within the canvas. Later, the audacious Tintoretto brought dramatic energy and dynamic compositions, while Veronese dazzled with opulent feasts and vibrant color, truly solidifying Venice's unique contribution to the Renaissance. Tintoretto, in particular, was known for his dramatic use of perspective and dynamic compositions, filling vast canvases with swirling figures and intense emotional narratives, pushing the boundaries of what a painting could convey. Unlike Florence's intellectual rigor, Venice's art often felt more immediate, more sensual, a reflection of its cosmopolitan, pleasure-seeking culture and its mastery of luminous effects.

More Than Just Pretty Pictures: Key Characteristics That Blew My Mind

When I first looked at Renaissance paintings, I thought, "Wow, they look real!" And that's true, but it's how they achieved that realism that really grabbed me – the dedication, the science, the sheer ingenuity behind it all. It wasn't magic; it was a combination of groundbreaking techniques and a fresh way of seeing the world, allowing artists to tell stories with unprecedented clarity and emotional depth. This era also marked a crucial shift in the perception of the artist: no longer merely skilled craftsmen, they were increasingly seen as intellectual "geniuses," capable of profound thought and innovative creation, much like poets or philosophers. Artists began to sign their works more frequently, and their individual styles became highly prized, reflecting a new understanding of artistic originality and personal expression, a far cry from the anonymity of many medieval artisans. It was almost like they developed a secret language to communicate directly with your senses, bypassing the purely intellectual. This elevation of the artist's status was revolutionary, allowing for greater creative freedom and recognition. It wasn't magic; it was a combination of groundbreaking techniques and a fresh way of seeing the world, allowing artists to tell stories with unprecedented clarity and emotional depth. This era also marked a crucial shift in the perception of the artist: no longer merely skilled craftsmen, they were increasingly seen as intellectual "geniuses," capable of profound thought and innovative creation, much like poets or philosophers. It was almost like they developed a secret language to communicate directly with your senses, bypassing the purely intellectual.

Perspective: The Ultimate Illusion

This was probably the biggest game-changer. Before the Renaissance, paintings often looked flat, like cut-outs pasted onto a background. Then, artists like Brunelleschi (yes, the architect from Florence, actually!) famously conducted experiments that proved how linear perspective worked. His friend and fellow Florentine, Leon Battista Alberti, then codified these principles in his influential treatise On Painting (1435), providing a theoretical framework for artists. Alberti's work was crucial because it translated Brunelleschi's practical discoveries into a written guide, making linear perspective accessible and teachable across Europe, a true intellectual gift to the art world. Painters like Masaccio swiftly applied these principles to their frescoes, most notably in his Holy Trinity, where the architectural setting appears to recede convincingly into space, placing the figures within a rational, tangible environment, making the viewer feel like they could step right into the sacred scene. Suddenly, you had the illusion of depth, of a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, creating a believable, immersive world for the viewer. It wasn't just a trick; it was a scientific approach to art, rooted in mathematics and optics. It’s like they unlocked a cheat code for reality! I mean, think about it: creating an entire world within a frame that felt utterly real. It totally changed everything, much like understanding the foundational elements of art can change how you approach your own work. And if you’re a visual person like me, seeing how they mastered it is fascinating. This innovation not only revolutionized painting but also profoundly influenced architecture and stage design, creating a new visual language for the era. Even artists like Paolo Uccello, with his almost obsessive dedication to foreshortening and complex geometric compositions, pushed the boundaries of what perspective could achieve, creating dynamic, almost dizzying spatial effects in his battle scenes. This was probably the biggest game-changer. Before the Renaissance, paintings often looked flat, like cut-outs pasted onto a background. Then, artists like Brunelleschi (yes, the architect from Florence, actually!) famously conducted experiments that proved how linear perspective worked. His friend and fellow Florentine, Leon Battista Alberti, then codified these principles in his influential treatise On Painting (1435), providing a theoretical framework for artists. Painters like Masaccio swiftly applied these principles to their frescoes, most notably in his Holy Trinity, where the architectural setting appears to recede convincingly into space, placing the figures within a rational, tangible environment. Suddenly, you had the illusion of depth, of a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, creating a believable, immersive world for the viewer. It wasn't just a trick; it was a scientific approach to art, rooted in mathematics and optics. It’s like they unlocked a cheat code for reality! I mean, think about it: creating an entire world within a frame that felt utterly real. It totally changed everything, much like understanding the foundational elements of art can change how you approach your own work. And if you’re a visual person like me, seeing how they mastered it is fascinating. This innovation not only revolutionized painting but also profoundly influenced architecture and stage design, creating a new visual language for the era.

Composition & Symbolism: More Than Meets the Eye

Beyond the technical innovations, Renaissance artists were masters of composition. They carefully arranged figures and elements within their paintings to guide the viewer's eye, create balance, and enhance the narrative. This often involved using geometric principles, like pyramids, triangles, or circles, to create a sense of order, harmony, and monumental stability, grounding their figures within a rational space. And while their art became more realistic, symbolism didn't disappear; in fact, it often became more subtly integrated. Objects, gestures, and even colors often carried deeper meanings, weaving layers of interpretation into the visual story, appealing to both the intellect and the emotions. For instance, in many Madonna and Child paintings, a small, symbolic detail like a specific flower (such as a red carnation symbolizing divine love or a white lily for purity) or fruit (like an apple for original sin or cherries for the blood of Christ) might allude to Christ's future sacrifice or resurrection, adding profound layers to seemingly simple scenes. The integration of classical mythology also often carried symbolic weight, with figures like Venus or Mars subtly representing philosophical concepts. Beyond these, everyday objects could be imbued with meaning: a broken eggshell for resurrection, a dog for fidelity, or a mirror for self-knowledge. Even the placement of figures or the orientation of a gaze could carry profound theological or humanistic meaning. It's like finding hidden messages in plain sight, making the act of looking a delightful puzzle that rewards close examination. This rich tapestry of symbolism allowed artists to communicate complex ideas and emotions to an educated audience, adding layers of intellectual engagement to the visual experience.

Even in seemingly chaotic modern abstract art, like the one above, you can often find underlying principles of composition and balance, demonstrating how these timeless concepts transcend specific eras and styles.

Beyond the technical innovations, Renaissance artists were masters of composition. They carefully arranged figures and elements within their paintings to guide the viewer's eye, create balance, and enhance the narrative. This often involved using geometric principles, like pyramids, triangles, or circles, to create a sense of order, harmony, and monumental stability, grounding their figures within a rational space. And while their art became more realistic, symbolism didn't disappear; in fact, it often became more subtly integrated. Objects, gestures, and even colors often carried deeper meanings, weaving layers of interpretation into the visual story, appealing to both the intellect and the emotions. For instance, in many Madonna and Child paintings, a small, symbolic detail like a specific flower (such as a red carnation symbolizing divine love or a white lily for purity) or fruit (like an apple for original sin or cherries for the blood of Christ) might allude to Christ's future sacrifice or resurrection, adding profound layers to seemingly simple scenes. Even the placement of figures or the orientation of a gaze could carry profound theological or humanistic meaning. It's like finding hidden messages in plain sight, making the act of looking a delightful puzzle that rewards close examination.

Anatomy & Idealism: The Perfect Human Form

The Renaissance was obsessed with the human body – not just as a physical entity, but as a divine creation capable of extraordinary beauty and grace. Artists meticulously studied anatomy, sometimes controversially dissecting cadavers, to understand every muscle, bone, and tendon. Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical drawings, for example, are masterpieces of scientific observation and artistic rendering, revealing an unparalleled understanding of the human form. This wasn't just for realism; it was often to achieve an idealized form, drawing inspiration from classical Greek and Roman sculpture. Artists like Polyclitus's Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) provided a canon of ideal proportions that Renaissance masters studied and adapted, seeing in these ancient forms a perfection to aspire to. They meticulously measured and drew, internalizing these classical ideals to create figures that were both lifelike and transcendent. It was an homage, yes, but also a bold reinterpretation. They sought to represent humans not just as they were, but as they could be – perfect, heroic, and embodying intellectual and physical excellence, a true reflection of the humanist ideal. This blend of scientific observation and philosophical idealism is a hallmark of the era, elevating the human figure to a subject worthy of profound artistic exploration. This quest for ideal beauty also extended to the depiction of emotions, which were rendered with a newfound psychological depth, reflecting the inner life of the individual, not just a surface portrayal. Think of Michelangelo's 'David' – not just a man, but an ideal, powerful, and deeply contemplative embodiment of human potential. They sought to represent humans not just as they were, but as they could be – perfect, heroic, and embodying intellectual and physical excellence. This blend of scientific observation and philosophical idealism is a hallmark of the era, elevating the human figure to a subject worthy of profound artistic exploration.

The Renaissance was obsessed with the human body – not just as a physical entity, but as a divine creation capable of extraordinary beauty and grace. Artists meticulously studied anatomy, sometimes controversially dissecting cadavers, to understand every muscle, bone, and tendon. Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical drawings, for example, are masterpieces of scientific observation and artistic rendering, revealing an unparalleled understanding of the human form. This wasn't just for realism; it was often to achieve an idealized form, drawing inspiration from classical Greek and Roman sculpture. Artists like Polyclitus's Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) provided a canon of ideal proportions that Renaissance masters studied and adapted. They sought to represent humans not just as they were, but as they could be – perfect, heroic, and embodying intellectual and physical excellence. This blend of scientific observation and philosophical idealism is a hallmark of the era, elevating the human figure to a subject worthy of profound artistic exploration. This quest for ideal beauty also extended to the depiction of emotions, which were rendered with a newfound psychological depth, reflecting the inner life of the individual. They sought to represent humans not just as they were, but as they could be – perfect, heroic, and embodying intellectual and physical excellence. This blend of scientific observation and philosophical idealism is a hallmark of the era, elevating the human figure to a subject worthy of profound artistic exploration.

Naturalism & Realism: Seeing Humans as Humans

This went hand-in-hand with humanism. Artists wanted to depict the human body accurately, celebrating its beauty and anatomical correctness. They studied anatomy (sometimes quite controversially, if you read the history, with artists even participating in dissections to understand the human form!). It wasn’t just about making people look good; it was about making them look real, with all their emotions and physical presence, reflecting the era's broader scientific curiosity and reverence for creation. This focus on naturalism extended beyond figures to include landscapes and objects too, rendering textures, light, and atmospheric effects with unprecedented fidelity. This was a massive departure from the more symbolic, less naturalistic figures and settings often seen in medieval art, where hierarchical scaling (larger figures representing greater importance) and abstract gold-leaf backgrounds were common. Medieval art, while rich in its own spiritual language, often prioritized conveying theological truths over mimetic reality. Renaissance artists instead grounded the divine in the tangible, giving sacred stories a relatable, earthly setting and making them feel more immediate and human, bringing the spiritual down to earth, quite literally. Their meticulous rendering of textiles, architectural details, and natural phenomena also contributed to this sense of believable reality, inviting the viewer into a fully realized world. This naturalism also extended to portraiture, capturing the unique features and personalities of individuals with unprecedented fidelity, a clear reflection of humanism's influence, allowing us to 'meet' people from centuries ago. This wasn't just about technical skill; it was a philosophical statement, asserting the dignity and importance of human existence within the divine order. This went hand-in-hand with humanism. Artists wanted to depict the human body accurately, celebrating its beauty and anatomical correctness. They studied anatomy (sometimes quite controversially, if you read the history, with artists even participating in dissections to understand the human form!). It wasn’t just about making people look good; it was about making them look real, with all their emotions and physical presence, reflecting the era's broader scientific curiosity and reverence for creation. This focus on naturalism extended beyond figures to include landscapes and objects too, rendering textures, light, and atmospheric effects with unprecedented fidelity. This was a massive departure from the more symbolic, less naturalistic figures and settings often seen in medieval art, where hierarchical scaling and abstract backgrounds were common. Renaissance artists instead grounded the divine in the tangible, giving sacred stories a relatable, earthly setting and making them feel more immediate and human. This naturalism also extended to portraiture, capturing the unique features and personalities of individuals with unprecedented fidelity, a clear reflection of humanism's influence. It grounded the divine in the tangible, and gave sacred stories a relatable, earthly setting, making them feel more immediate and human.

Chiaroscuro & Sfumato: The Magic of Light and Shadow

These are two fancy words that just mean "really clever ways with light and shadow."

- Chiaroscuro (what is chiaroscuro in art?) is about using strong contrasts between light and dark, usually bold and dramatic. Think of a spotlight hitting a figure in a dark room, creating powerful emotional impact and emphasizing three-dimensionality, much like the intense lighting in Caravaggio's later works (though he's Baroque, his dramatic use of chiaroscuro owes much to Renaissance foundations). Even early Renaissance artists like Masaccio, in his Tribute Money, used chiaroscuro to give his figures a profound sense of weight and presence, making them feel like they could step right out of the fresco, as if illuminated by a single, dramatic light source. This technique didn't just add drama; it fundamentally made the painted figures feel real, occupying real space, a sensation often lacking in earlier art. It sculpts forms out of shadow, making them feel incredibly solid and present. The dramatic interplay of light and shadow could also intensify emotional narratives, drawing the viewer deeper into the psychological drama of the scene.

- Sfumato (what is sfumato?) (Leonardo da Vinci’s specialty, bless his genius!) is softer. It's about subtle gradations of light and shadow, blurring outlines so they blend into one another, creating a delicate, hazy effect. This technique was particularly effective in rendering delicate transitions in skin tones, creating a lifelike softness that was unparalleled. It gives everything a soft, misty, almost dreamy quality, lending an air of mystery and psychological depth, perfectly exemplified in the hazy backgrounds and soft contours of the Mona Lisa. The Mona Lisa’s smile? Pure sfumato magic, contributing to its enigmatic allure! It's that subtle, almost imperceptible blurring of contours around her mouth and eyes that makes her expression seem to shift, a trick of light and shadow that keeps us guessing and returning to her gaze, a testament to Leonardo's unparalleled skill.

credit, licence It's that subtle, almost imperceptible blurring of contours around her mouth and eyes that makes her expression seem to shift, a trick of light and shadow that keeps us guessing and returning to her gaze, a testament to Leonardo's unparalleled skill. These are two fancy words that just mean "really clever ways with light and shadow."

- Chiaroscuro (what is chiaroscuro in art?) is about using strong contrasts between light and dark, usually bold and dramatic. Think of a spotlight hitting a figure in a dark room, creating powerful emotional impact and emphasizing three-dimensionality, much like the intense lighting in Caravaggio's later works (though he's Baroque, his dramatic use of chiaroscuro owes much to Renaissance foundations). It sculpts forms out of shadow, making them feel incredibly solid and present.

- Sfumato (what is sfumato?) (Leonardo da Vinci’s specialty, bless his genius!) is softer. It's about subtle gradations of light and shadow, blurring outlines so they blend into one another, creating a delicate, hazy effect. It gives everything a soft, misty, almost dreamy quality, lending an air of mystery and psychological depth, perfectly exemplified in the hazy backgrounds and soft contours of the Mona Lisa. The Mona Lisa’s smile? Pure sfumato magic, contributing to its enigmatic allure!

Balance & Proportion: The Classical Comeback

The Renaissance artists looked back to the Greeks and Romans for ideals of beauty, which often involved perfect balance and proportion. They used mathematical ratios (like the Golden Ratio, often seen as embodying "divine proportion," if you're into that sort of thing) to create compositions that felt harmonious, stable, and visually satisfying. This applied not only to the placement of figures in paintings but also to architectural designs, ensuring that buildings like Brunelleschi's Pazzi Chapel or Bramante's Tempietto embodied perfect geometric harmony. This rigorous application of geometry and mathematics ensured that their artworks possessed an inherent order and beauty that transcended mere representation. It's a bit like getting all the pieces of a puzzle to fit just right, creating a profound sense of calm and order. Architects like Brunelleschi and Alberti meticulously applied classical ratios (derived from ancient Roman architect Vitruvius) to their buildings, aiming for structures that embodied divine harmony and rational order, creating spaces that felt both grand and utterly human. Think of Alberti's Santa Maria Novella facade, with its perfect geometric divisions, or Brunelleschi's Ospedale degli Innocenti, with its rhythmic arcades – each a visual symphony of order and beauty. It's like every column, every arch, every window was placed with a mathematical precision designed to soothe the eye and uplift the spirit, a visible manifestation of ideal beauty and order. This is a concept I still grapple with in my own abstract work—how to create balance in art composition without literal symmetry. The pursuit of perfect proportion in art was a serious business back then, believed to reflect the divine order of the cosmos.

The Renaissance artists looked back to the Greeks and Romans for ideals of beauty, which often involved perfect balance and proportion. They used mathematical ratios (like the Golden Ratio, often seen as embodying "divine proportion," if you're into that sort of thing) to create compositions that felt harmonious, stable, and visually satisfying. This applied not only to the placement of figures in paintings but also to architectural designs, ensuring that buildings like Brunelleschi's Pazzi Chapel or Bramante's Tempietto embodied perfect geometric harmony. This rigorous application of geometry and mathematics ensured that their artworks possessed an inherent order and beauty that transcended mere representation. It's a bit like getting all the pieces of a puzzle to fit just right, creating a profound sense of calm and order. This is a concept I still grapple with in my own abstract work—how to create balance in art composition without literal symmetry. The pursuit of perfect proportion in art was a serious business back then, believed to reflect the divine order of the cosmos. Architects like Brunelleschi and Alberti meticulously applied classical ratios (derived from ancient Roman architect Vitruvius) to their buildings, aiming for structures that embodied divine harmony and rational order, creating spaces that felt both grand and utterly human. Think of Alberti's Santa Maria Novella facade, with its perfect geometric divisions, or Brunelleschi's Ospedale degli Innocenti, with its rhythmic arcades – each a visual symphony of order and beauty, a conscious effort to manifest mathematical and divine perfection in stone. Architects like Brunelleschi and Alberti meticulously applied classical ratios (derived from ancient Roman architect Vitruvius) to their buildings, aiming for structures that embodied divine harmony and rational order, creating spaces that felt both grand and utterly human.

The Titans: Artists Who Still Speak to Me

Early Stars: More Voices from the Florentine Dawn

While we often jump straight to the 'big three,' it's like skipping the amazing opening acts at a concert to get to the headliners. The Early Renaissance was a vibrant period teeming with groundbreaking artists, each contributing essential brushstrokes to the canvas of this new era. These were the thinkers and doers who truly laid the conceptual and technical groundwork for the artistic explosion that followed.

Before the giants of the High Renaissance, a constellation of brilliant artists in the Early Renaissance laid the essential groundwork, experimenting with new techniques and forms that would define the era. Their innovations were crucial in setting the stage for the artistic explosion that followed.

While we justly celebrate the "big three" of the High Renaissance, it's crucial to remember the trailblazers who laid the groundwork. One name that always comes to mind is Masaccio. Working in the early 15th century, he was a genius of perspective and emotional realism, often considered the father of Renaissance painting. His frescoes, like "The Tribute Money" in the Brancacci Chapel, don't just depict a biblical scene; they create a believable world with figures that feel weighty, anatomically correct, and real, bathed in a consistent, natural light. The way he rendered the light source as if coming from the chapel window itself was a revolutionary step towards unifying painted space with the viewer's reality. The drama of Peter retrieving the coin from the fish's mouth and Jesus's calm authority are made tangible through this groundbreaking realism. He literally made the space recede with revolutionary linear perspective, drawing you into the narrative as if you were standing right there, setting a new standard for monumental painting. And speaking of groundbreaking perspective, Paolo Uccello was famously obsessed with it, using complex geometric constructions in his battle scenes (like 'The Battle of San Romano') to create dynamic, almost fantastical, deep spaces. His work sometimes feels like a delightful puzzle of receding forms and foreshortened figures, pushing the boundaries of spatial illusion, transforming battle into a geometric ballet. Then there's the lyrical beauty of Sandro Botticelli. While many of his contemporaries were mastering linear perspective, Botticelli was weaving tales of classical mythology and delicate beauty, often with a distinctly Florentine elegance. His "Birth of Venus" and "Primavera" are iconic for their flowing lines, vibrant colors, and dreamlike, almost melancholic quality, capturing a different facet of humanism – one steeped in poetry, allegory, and a nostalgic longing for classical antiquity rather than strict scientific realism. These works are often interpreted through the lens of Neo-Platonism, blending classical ideals with Christian spirituality, creating layers of symbolic meaning that reward careful contemplation. Botticelli, influenced by the Platonic Academy in Florence, often used classical myths as vehicles for profound philosophical and theological concepts, elevating his art beyond mere storytelling. His figures possess an almost ethereal grace that feels both ancient and utterly new, with a distinct decorative flair that sets his work apart. His unique style, characterized by its elegant contours and decorative beauty, truly stands out from the more robust naturalism of his peers, offering a poetic interpretation of classical themes. But before these Florentine stars truly shone, we have to acknowledge the proto-Renaissance giant, Giotto di Bondone. Often considered the bridge from the Byzantine style to the Renaissance, his frescoes (like those in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua) broke away from flat, symbolic representations. He introduced emotional intensity, dramatic narrative, and a powerful sense of three-dimensionality and weight to his figures, making sacred stories feel profoundly human and relatable. He really set the stage for the human-centered narrative and the psychological realism that would define the Renaissance. His Lamentation scene, for instance, is a raw outpouring of human grief, a stark departure from earlier, more impassive depictions, showing angels and humans alike consumed by sorrow, making the divine tragedy deeply human.

Speaking of trailblazers, we can't forget Giotto (even though he's often considered late Gothic, his influence on the Renaissance is undeniable). He was a true precursor, setting the stage for the human-centered narrative and psychological realism that would define the Renaissance, making sacred stories feel profoundly human and relatable.

credit,

licence His frescoes, like those in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, broke away from the flat, symbolic art of the Byzantine tradition, introducing emotional intensity, dramatic narrative, and a powerful sense of three-dimensionality and weight to his figures. His Lamentation scene, for instance, is a raw outpouring of human grief, a stark departure from earlier, more impassive depictions. Giotto’s ability to imbue his figures with genuine human emotion and to create a sense of deep space, even without full linear perspective, was a crucial precursor to the Renaissance, truly making sacred stories relatable. He really set the stage for the human-centered narrative and the psychological realism that would define the Renaissance, making sacred stories feel profoundly human and relatable. And then there's Fra Angelico, a Dominican friar whose works beautifully blended the spiritual with the burgeoning naturalism of the Early Renaissance, creating serene and luminous paintings that evoke deep devotion and heavenly grace. He showed that piety and artistic innovation could go hand-in-hand, depicting saints and angels with both ethereal beauty and a grounded sense of presence. His frescoes in the monastery of San Marco in Florence are not just artworks; they're meditations, designed to aid devotion, yet infused with the new language of perspective and light, making the divine feel intimately present. Fra Angelico's delicate touch and radiant color palette created an atmosphere of spiritual serenity, a perfect blend of devout purpose and burgeoning artistic innovation. His works, like the frescoes in the Vatican's Niccoline Chapel, exemplify a gentle yet profound religious feeling infused with the era's new artistic language. We also can't forget Andrea del Verrocchio, a masterful sculptor and painter who ran one of the most important workshops in Florence, where young Leonardo da Vinci trained! Imagine the sheer talent gathered under one roof! His influence as a teacher and innovator, particularly in bronze sculpture (like his 'David,' whose youthful swagger is a marvel, or 'Christ and St. Thomas' on Orsanmichele, a dialogue in bronze that radiates moral authority, where the drapery and interaction between figures are masterfully rendered), was immense, shaping the next generation of artistic giants, emphasizing anatomical precision and expressive naturalism and preparing them for the monumental tasks ahead. His rigorous training and emphasis on both drawing (disegno) and observation ensured his students were well-prepared for the challenges of the burgeoning art world. Imagine Leonardo, Botticelli, and Perugino all learning under his roof – what an artistic melting pot!

When we talk about the Italian Renaissance, a few names invariably pop up, and for good reason. These were truly exceptional individuals who pushed boundaries, broke rules, and created works that still captivate us centuries later. It was a fiercely competitive, yet incredibly fertile, environment where genius spurred on genius.

Leonardo da Vinci: The Ultimate Polymath

Seriously, what didn't this man do? Painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist, writer… I get tired just listing it all! His notebooks are filled with meticulous observations, visionary inventions (from flying machines to military defenses like a giant crossbow or an armored tank), and anatomical studies that were centuries ahead of their time, demonstrating a profound understanding of the human body and natural world. He was relentless in his curiosity, a trait I deeply admire in any artist. The Mona Lisa, The Last Supper – these aren't just paintings; they're cultural touchstones. The Last Supper, in particular, revolutionized fresco painting with its innovative composition, capturing a pivotal moment of psychological intensity and individual human emotion among the apostles, each reacting distinctly to Christ's revelation. Its daring use of perspective draws the viewer directly into the dramatic moment of Christ's announcement of betrayal. Each apostle's reaction, from shock to denial to anger, is exquisitely captured, making it a profound study in human psychology. Tragically, Leonardo's experimental fresco technique meant the work began to deteriorate even in his lifetime, a poignant reminder of his restless quest for innovation over traditional methods, prioritizing novel solutions even at the risk of longevity. But beyond these famous works, consider his incredibly detailed anatomical drawings, his engineering designs for bridges and fortifications (including a giant crossbow and an armored tank), or his studies of water currents and plant life. His visionary sketches of flying machines, submarines, and even armored tanks illustrate a mind constantly pushing the boundaries of what was conceivable, laying theoretical groundwork centuries before actualization. He saw art and science not as separate disciplines, but as two sides of the same coin, both aimed at understanding the world and revealing its underlying truths. His anatomical studies, for instance, not only served his painting but also advanced medical knowledge, showing how deeply intertwined his artistic and scientific pursuits truly were. This holistic approach is what makes his genius so enduring. If you want to dive deeper into his genius, you absolutely have to read the ultimate guide to Leonardo da Vinci. Seriously, what didn't this man do? Painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist, writer… I get tired just listing it all! His notebooks are filled with meticulous observations, visionary inventions (from flying machines to military defenses like a giant crossbow or an armored tank), and anatomical studies that were centuries ahead of their time, demonstrating a profound understanding of the human body and natural world. He was relentless in his curiosity, a trait I deeply admire in any artist. The Mona Lisa, The Last Supper – these aren't just paintings; they're cultural touchstones. The Last Supper, in particular, revolutionized fresco painting with its innovative composition, capturing a pivotal moment of psychological intensity and individual human emotion among the apostles. Its daring use of perspective draws the viewer directly into the dramatic moment of Christ's announcement of betrayal. But beyond these famous works, consider his incredibly detailed anatomical drawings, his engineering designs for bridges and fortifications, or his studies of water currents and plant life. His visionary sketches of flying machines, submarines, and even armored tanks illustrate a mind constantly pushing the boundaries of what was conceivable. He saw art and science not as separate disciplines, but as two sides of the same coin, both aimed at understanding the world and revealing its underlying truths. This holistic approach is what makes his genius so enduring. If you want to dive deeper into his genius, you absolutely have to read the ultimate guide to Leonardo da Vinci.

Michelangelo: Emotion in Stone (and Fresco!)

Michelangelo Buonarroti, now there was a force of nature. He famously considered himself a sculptor first and foremost, and his "David" is just… monumental. The sheer skill, the emotional intensity – it’s breathtaking. And then he painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a project he initially resisted, creating one of the most iconic frescoes in human history. Talk about being versatile! His figures are powerful, muscular, full of terribilità (a kind of awesome, sublime grandeur that evokes terror and awe simultaneously, expressing a powerful, almost overwhelming emotional and physical force), reflecting his belief in the divine spark within humanity. It's a sense of divine power manifested in human form, a truly unique characteristic. Beyond his monumental achievements in sculpture and painting, he was also a significant architect, contributing to St. Peter's Basilica (designing its magnificent dome, a triumph of engineering and classical harmony, a crowning achievement in both scale and symbolism that defined the Roman skyline for centuries, completed after his death but to his vision) and the Laurentian Library (a masterclass in Mannerist architectural innovation, where walls seem to press in and staircases cascade like stone waterfalls, creating a dynamic and unsettling space), and even a poet, expressing his inner turmoil and spiritual longing in verse. His 'terribilità' isn't just about raw power; it's about the overwhelming sublime, the feeling of standing before something so grand it humbles and inspires you simultaneously. It's an almost terrifying beauty, a divine energy made manifest, that demands reverence and introspection from the viewer, an experience that transcends mere aesthetic appreciation. His sonnets reveal a profound spiritual struggle and an intense devotion, often reflecting on the nature of beauty and the divine, grappling with themes of mortality and salvation. Beyond his painting and sculpture, Michelangelo was also a significant architect, contributing to the magnificent dome of St. Peter's Basilica (a crowning achievement in both scale and symbolism that defined the Roman skyline for centuries) and the Laurentian Library (a masterclass in Mannerist architectural innovation, where walls seem to press in and staircases cascade like stone waterfalls). Michelangelo's struggles and fierce personality are also part of his legend. He was a difficult, solitary genius, but his relentless pursuit of perfection left an indelible mark on art history. If his work speaks to your soul, the ultimate guide to Michelangelo is a must-read. Michelangelo Buonarroti, now there was a force of nature. He famously considered himself a sculptor first and foremost, and his "David" is just… monumental. The sheer skill, the emotional intensity – it’s breathtaking. And then he painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a project he initially resisted, creating one of the most iconic frescoes in human history. Talk about being versatile! His figures are powerful, muscular, full of terribilità (a kind of awesome, sublime grandeur that evokes terror and awe simultaneously, expressing a powerful, almost overwhelming emotional and physical force), reflecting his belief in the divine spark within humanity. It's a sense of divine power manifested in human form, a truly unique characteristic. Beyond his monumental achievements in sculpture and painting, he was also a significant architect, contributing to St. Peter's Basilica (designing its magnificent dome, a triumph of engineering and classical harmony) and the Laurentian Library (a masterclass in Mannerist architectural innovation), and even a poet, expressing his inner turmoil and spiritual longing in verse. His sonnets reveal a profound spiritual struggle and an intense devotion, often reflecting on the nature of beauty and the divine. Michelangelo's struggles and fierce personality are also part of his legend. He was a difficult, solitary genius, but his relentless pursuit of perfection left an indelible mark on art history. If his work speaks to your soul, the ultimate guide to Michelangelo is a must-read.

Raphael: The Master of Harmony

Compared to the stormy genius of Michelangelo or the restless curiosity of Leonardo, Raphael Sanzio brought a sense of serene beauty, grace, and harmonious composition to his art. His figures are graceful, his colors vibrant, and his compositions perfectly balanced, often employing dynamic yet stable arrangements. Think of his "School of Athens" in the Vatican's Stanze della Segnatura – a masterpiece of perspective, humanism, and intricate detail, bringing together ancient philosophers and artists in a grand, idealized setting that celebrates intellectual exchange. His Madonnas, too, like the Sistine Madonna or the Madonna della Sedia, are renowned for their tender grace and perfect beauty, imbued with a profound sense of human connection. He just had this incredible knack for making everything look effortless, even though we know it was anything but. Raphael's influence on subsequent generations of artists was immense, largely due to his mastery of composition, his tender Madonnas (such as the exquisite Sistine Madonna with its iconic cherubs, those little rascals peering up from the bottom, or the intimate Madonna della Sedia), and his ability to convey both dignity and grace. His frescoes in the Stanze della Segnatura, like 'The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament' (symbolizing Theology) or 'Parnassus' (symbolizing Literature and Poetry), demonstrate his unparalleled ability to organize complex narratives with clarity and expressive power, each wall representing a different branch of human knowledge: Philosophy, Theology, Poetry, and Justice. It’s a complete intellectual universe rendered in paint. He truly set a standard for classical beauty and the ideal Renaissance style, leading a highly productive workshop that disseminated his artistic vision, with numerous assistants helping to fulfill his many commissions and spread his elegant style across Italy, ensuring his harmonious aesthetic permeated the artistic landscape for centuries. His ability to synthesize the dramatic power of Michelangelo with the intellectual depth of Leonardo, while maintaining his own unique grace, cemented his reputation as the quintessential High Renaissance master. Compared to the stormy genius of Michelangelo or the restless curiosity of Leonardo, Raphael Sanzio brought a sense of serene beauty, grace, and harmonious composition to his art. His figures are graceful, his colors vibrant, and his compositions perfectly balanced, often employing dynamic yet stable arrangements. Think of his "School of Athens" in the Vatican's Stanze della Segnatura – a masterpiece of perspective, humanism, and intricate detail, bringing together ancient philosophers and artists in a grand, idealized setting that celebrates intellectual exchange. His Madonnas, too, like the Sistine Madonna or the Madonna della Sedia, are renowned for their tender grace and perfect beauty, imbued with a profound sense of human connection. He just had this incredible knack for making everything look effortless, even though we know it was anything but. Raphael's influence on subsequent generations of artists was immense, largely due to his mastery of composition, his tender Madonnas (such as the exquisite Sistine Madonna with its iconic cherubs, or the intimate Madonna della Sedia), and his ability to convey both dignity and grace. He truly set a standard for classical beauty and the ideal Renaissance style, leading a highly productive workshop that disseminated his artistic vision, with numerous assistants helping to fulfill his many commissions and spread his elegant style across Italy.

Donatello: The Sculptural Innovator

Before Michelangelo, there was Donatello. He was a pioneer of the Early Renaissance, pushing sculpture into new, expressive territory. His bronze "David" is often cited as the first freestanding nude sculpture since antiquity, a truly bold and revolutionary statement that signaled a return to classical ideals of the human form, yet imbued with a startling psychological depth and a playful sensuality. This youthful, almost effeminate figure, standing triumphantly over Goliath's severed head, was a revolutionary departure from medieval depictions, celebrating human beauty and individual heroism. He also created powerful narrative reliefs, like those for the Siena Baptistery, which showcased his innovative use of schiacciato (flattened relief) to create the illusion of deep space, a technique where forms are barely raised from the surface but convey immense depth through subtle carving and perspective. Donatello's willingness to break from convention, to imbue his figures with raw emotion and psychological complexity, makes him one of the most vital figures of the Early Renaissance. He brought a raw emotional intensity and a sense of psychological depth to his figures that was revolutionary. His works, like the intensely expressive 'Mary Magdalene Penitent' carved in wood, show a remarkable departure from the idealized forms of antiquity, favoring a stark realism that captures spiritual suffering with brutal honesty. Her emaciated form and haggard expression convey a profound spiritual and physical torment, a raw human vulnerability that is both shocking and deeply moving. My own ultimate guide to Donatello goes into more detail about his groundbreaking work. His equestrian monument of Gattamelata, for instance, revived the classical tradition of large-scale bronze equestrian portraits, imbuing the military commander with a powerful, almost stoic presence that speaks volumes about Renaissance ideals of leadership. This masterpiece, located in Padua, not only celebrated military might but also conveyed a sense of timeless authority and civic virtue, influencing countless future equestrian sculptures. Donatello wasn't just carving statues; he was bringing stone to life, making it breathe and feel, often expressing profound human experience and pushing the boundaries of what sculpture could convey, from the playful sensuality of his bronze 'David' to the stark agony of the Magdalene. Before Michelangelo, there was Donatello. He was a pioneer of the Early Renaissance, pushing sculpture into new, expressive territory. His bronze "David" is often cited as the first freestanding nude sculpture since antiquity, a truly bold and revolutionary statement that signaled a return to classical ideals of the human form, yet imbued with a startling psychological depth and a playful sensuality. He also created powerful narrative reliefs, like those for the Siena Baptistery, which showcased his innovative use of schiacciato (flattened relief) to create the illusion of deep space, a technique where forms are barely raised from the surface but convey immense depth through subtle carving and perspective. Donatello's willingness to break from convention, to imbue his figures with raw emotion and psychological complexity, makes him one of the most vital figures of the Early Renaissance. He brought a raw emotional intensity and a sense of psychological depth to his figures that was revolutionary. His works, like the intensely expressive 'Mary Magdalene Penitent' carved in wood, show a remarkable departure from the idealized forms of antiquity, favoring a stark realism. My own ultimate guide to Donatello goes into more detail about his groundbreaking work. His willingness to break from convention, to imbue his figures with raw emotion and psychological complexity, makes him one of the most vital figures of the Early Renaissance. He wasn't just carving statues; he was bringing stone to life, making it breathe and feel, often expressing profound human experience.

My Takeaway: Why This History Matters to a Modern Artist (and You!)

So, why am I, a contemporary artist who splashes vibrant colors onto canvases, obsessing over art that’s hundreds of years old? Well, for me, the Renaissance isn't just history; it's a profound lesson in artistic courage, observation, and the enduring power of human creativity.

It reminds me that art isn't static. It evolves, it reacts, it rebirths itself. The Renaissance artists were innovators, and their era really solidified the idea of the "artist as genius," a creative force much like a scientist or philosopher, a concept that endures to this day. This shift from anonymous craftsman to celebrated intellectual was monumental, elevating the status of art and its creators to unprecedented heights. Just as modern artists strive to be today, they broke free from conventions, challenged perspectives (literally!), and sought new ways to express their world. That spirit of exploration, that relentless pursuit of beauty and truth – whether it's through hyper-realistic figures or abstract explosions of color like those you can buy here on my site – is timeless. Honestly, there are days I stare at a blank canvas and feel that same pressure, that same thrill of creating something new, and it's then I feel a kinship with those old masters, separated by centuries but united by the act of creation. They were, in their own time, pushing against the established norms, much like contemporary artists strive to break new ground today. Their legacy is a potent reminder that art is a continuous conversation, a bridge across millennia. They were, in their own time, pushing against the established norms, much like contemporary artists strive to break new ground today. Their legacy is a potent reminder that art is a continuous conversation, a bridge across millennia.

Studying these masters has certainly shaped my own artistic journey and timeline, showing me that every brushstroke and every decision is part of a larger conversation that spans centuries. And it makes me think about what I want to leave behind, how my work fits into the grand tapestry of human expression, and how I can continue to innovate while respecting tradition. The Renaissance taught artists to look inward, and outward, with equal intensity – a profound lesson in self-awareness and universal observation. That's a lesson I carry into my own studio, whether I'm working in 's-Hertogenbosch at my museum here or just sketching at home, always seeking to bridge the past and the present. It reminds me that even in abstract, non-representational art, the echoes of balance, composition, and human expression resonate, connecting us across the centuries. It reminds me that every stroke, every decision, carries echoes of those who came before, building on a shared human story of creativity. This continuity, this conversation across centuries, is what makes art such a powerful and enduring force in the human experience, and it's something I try to honor in my own practice.

Frequently Asked Questions (The Stuff I Used to Wonder About)

Q: What's the main difference between Early and High Renaissance?

A: Good question! The Early Renaissance (roughly 1400-1490s) was all about discovery and experimentation. Artists were figuring out linear perspective, anatomy, and naturalism for the first time, primarily centered in Florence. Think Masaccio, Donatello, Botticelli. The Early Renaissance also saw a resurgence of portraiture and a greater focus on naturalistic depictions of the human form, moving away from the more stylized and symbolic figures of the preceding Gothic period. The High Renaissance (roughly 1490s-1527) was a shorter, incredibly intense period where those discoveries were perfected and brought to their absolute peak, expanding its influence to Rome and Venice. This is the era of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael, producing works of incredible balance, harmony, and technical mastery that defined an ideal, a kind of artistic golden age. It's like the early period laid the foundation, and the high period built the glorious penthouse, complete with frescoes on the ceiling! The High Renaissance masters, building on the innovations of their predecessors, achieved an unparalleled synthesis of classical ideals, technical virtuosity, and profound human emotion.