The Ultimate Guide to Michelangelo: Beyond the Marble and Myths

Ever wondered about Michelangelo, the fiery soul of the Renaissance? Join me on a personal journey through his masterpieces – David, Sistine Chapel, Pietà – and discover why his genius still resonates today. More than just an artist, he was a force of nature.

The Ultimate Guide to Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564): Sculptor, Painter, Architect, Poet, and Force of Nature

You know, it's not every day you encounter a work of art that doesn't just hang there, passively observing. Sometimes, a masterpiece reaches out, grabs you by the collar, and demands your full, undivided attention. That's the kind of electrifying, almost visceral jolt I get from Michelangelo Buonarroti. It's like he's still here, whispering secrets from the marble and paint. This wasn't just a sculptor, a painter, or an architect; he was a force of nature, a seismic event who bent the very arc of art history to his will. Trying to write about him? Honestly, it feels a bit like attempting to capture a supernova in a teacup – utterly daunting, profoundly inspiring, and probably a little messy, but oh-so-thrilling! But isn't that what truly great art is? A magnificent, untamed force of nature that leaves you breathless, perhaps a little intimidated, and absolutely changed. It’s like standing before a colossal waterfall; you can try to describe it, but until you feel the spray, hear the roar, and witness its power, you’re missing the essence. Five centuries later, and this guy still has us gasping, myself included, wondering how one human could pour so much intensity, so much raw human spirit, into everything he touched.

We've all seen the iconic images, of course. But to truly immerse ourselves in his story, to grasp the sheer audacity of his vision, and the raw, volcanic power of his execution? That's more than just flipping through a dusty history book; it's a thrilling, sometimes unsettling, journey deep into the mind of a genius who felt deeply, worked obsessively, and quite frankly, bent the arc of art history to his will. Forget those dry, academic accounts for a moment; this is about the intensely human soul pulsating beneath the divine creations. So, grab your favorite brew, settle in, and let's dig in, shall we? It's going to be a journey – one I hope reveals not just the genius of Michelangelo, but perhaps a piece of yourself in his struggles, his ambitions, and his relentless pursuit of beauty, just like I have.

Glossary of Key Terms

- Contrapposto: An Italian term describing a pose in sculpture or painting in which the weight is typically shifted to one leg, causing a natural asymmetry and counter-positioning of the body, creating a more dynamic and lifelike figure. Michelangelo mastered this technique, pushing its expressive potential to imbue his figures with an intense, latent energy. When you see it, you can almost feel the potential for movement, the story about to unfold, all within the stillness of the stone.

- Terribilità: An Italian term used to describe the awe-inspiring grandeur, intense emotional power, and commanding presence found in Michelangelo's art. Think of his Moses – it's not just a statue; it's a force, a storm in marble, that makes you feel a little tremor of awe and fear. That's 'terribilità' for you.

- Fresco: An ancient painting technique where pigment is applied to wet plaster. As the plaster dries, the paint becomes an integral part of the wall, creating durable, vibrant artworks. Michelangelo’s masterful use of fresco in the Sistine Chapel exemplifies the technical demands and artistic potential of this medium, where speed and precision are paramount, as the artist must work quickly before the plaster dries.

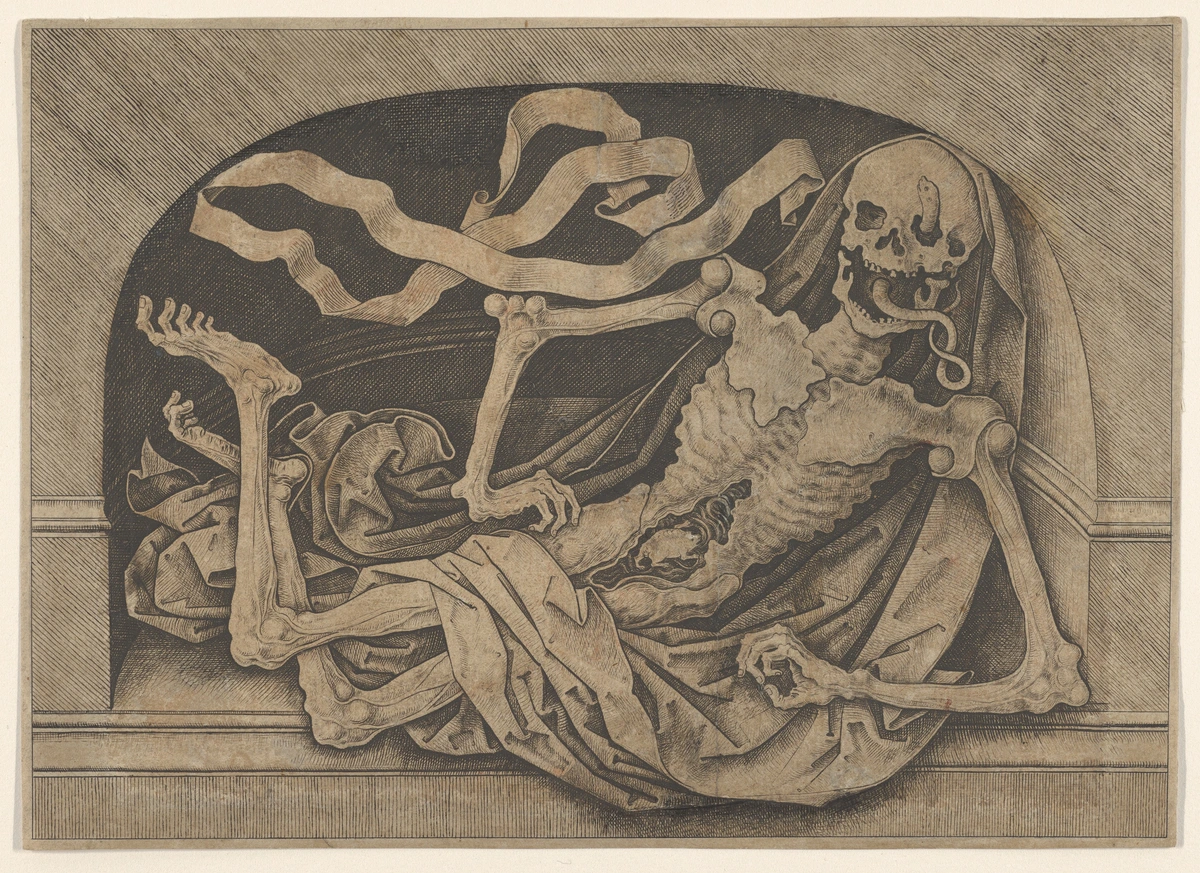

- Non-finito: Italian for 'unfinished,' this term describes sculptures or paintings that appear incomplete. For Michelangelo, it often became a deliberate artistic choice, especially in his later years, emphasizing the struggle of the form emerging from the raw material. It’s like he’s inviting you, the viewer, to finish the work in your mind, to become a co-creator, making it a profound statement about the creative process and the hidden life within the stone – and perhaps within us all.

- Patronage: The support, encouragement, financial aid, or 'sponsorship' that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the Renaissance, wealthy families (like the Medici) and the Church (like Pope Julius II) acted as vital patrons, commissioning monumental works that allowed artists like Michelangelo to thrive and create masterpieces. It was a symbiotic relationship, where power sought glory through art, and artists found the means to realize their grandest visions.

- Ignudi: The magnificent nude male figures depicted on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, often seen as allegories of the human soul, representations of classical ideals of beauty and strength, or symbols of humanity's spiritual potential.

- Renaissance Man: An individual with broad intellectual and artistic interests, proficient in various fields. Michelangelo, mastering sculpture, painting, architecture, and poetry, epitomized this ideal, constantly pushing boundaries and excelling across diverse disciplines, truly living up to the term 'uomo universale'.

- Schiacciato: An Italian term, meaning 'flattened relief,' a sculptural technique pioneered by Donatello and masterfully employed by Michelangelo. It creates the illusion of depth and perspective with extremely shallow carving, allowing for subtle gradations and intricate details, almost like drawing on marble. Michelangelo pushed its expressive potential to suggest immense space and fine detail with minimal projection, a testament to his nuanced understanding of sculptural illusion.

- Mannerism: An artistic style that emerged in Europe after the harmonious and balanced ideals of the High Renaissance. It's characterized by artificiality, elongated forms, complex compositions, and often a deliberate distortion of reality, almost as if artists were saying, "Okay, Michelangelo set the bar for naturalism, now let's push it further, bend the rules!" It was a reaction, a deliberate choice for drama and complexity, and heavily influenced by Michelangelo's later, more dramatic works, especially his Last Judgment.

- Baroque: An artistic style prevalent from the early 17th to mid-18th century, characterized by drama, movement, elaborate ornamentation, and often intense emotional expression. This was art that wanted to grab you and pull you into the action, much like a good thriller! It was heavily influenced by the theatricality, dynamism, and psychological depth inherent in Michelangelo's later works, setting the stage for a new era of artistic grandeur and emotional storytelling. You can almost feel his influence in every swirling drapery and dramatic gesture.

A Brief Chronology of a Genius

For a life so rich and prolific, a quick timeline helps anchor the monumental achievements:

- 1475: Born in Caprese, Tuscany.

- 1488: Apprenticed to Domenico Ghirlandaio in Florence.

- 1490-92: Studies in the Medici sculpture garden.

- 1496: First journey to Rome; carves Bacchus and begins the Pietà.

- 1501-04: Carves David for Florence.

- 1505: Commissioned for the Tomb of Pope Julius II (a project that would haunt him for decades).

- 1508-12: Paints the Sistine Chapel ceiling (reluctantly!).

- 1515: Completes Moses for the Julius II tomb.

- 1520s-30s: Works on the Medici Chapel and Laurentian Library in Florence.

- 1534: Permanently moves to Rome.

- 1536-41: Paints The Last Judgment on the Sistine Chapel altar wall.

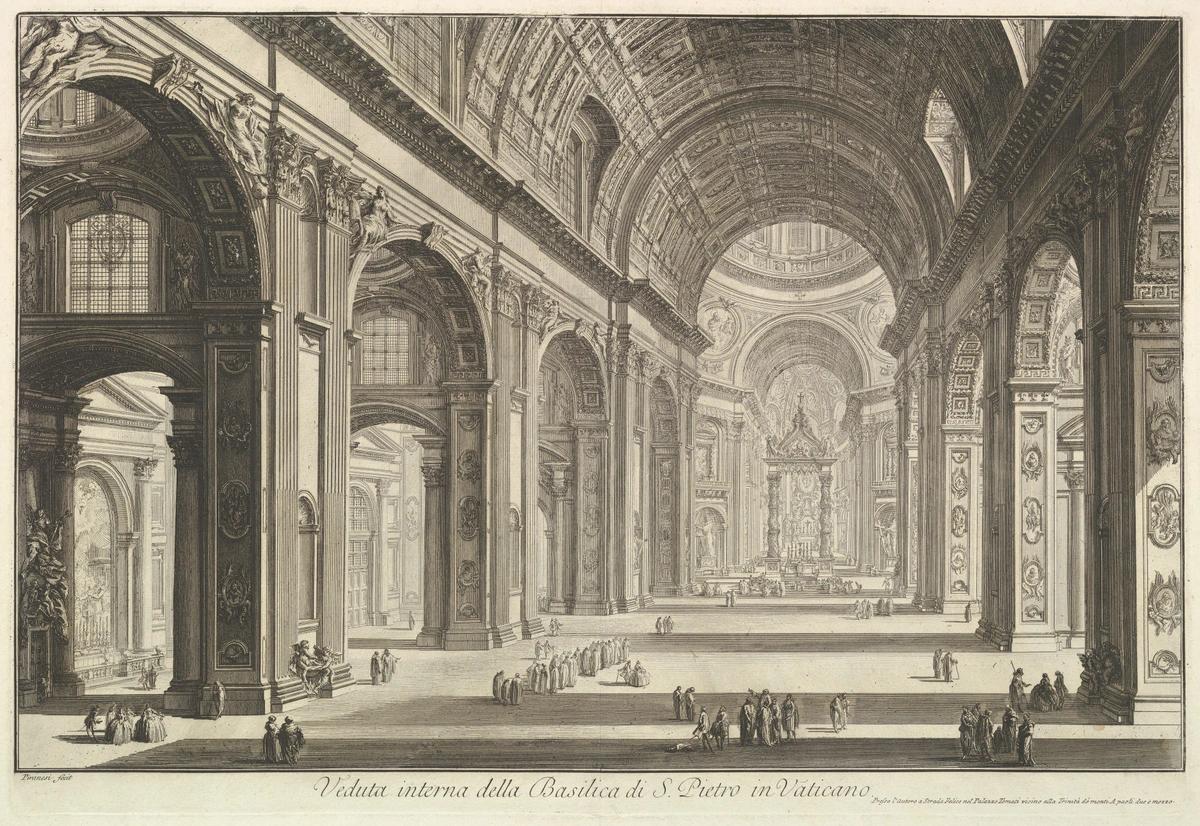

- 1546: Appointed chief architect of St. Peter's Basilica.

- 1564: Dies in Rome, buried in Santa Croce, Florence.

Further Reading and Viewing

To dive even deeper into the world of Michelangelo, consider exploring these resources:

- Books:

- Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces by Miles Unger (A fantastic dive into his pivotal works, offering a more focused lens on his monumental achievements.)

- Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling by Ross King (If you want to feel like you're right there, experiencing the drama and physical agony of the Sistine Chapel commission, this is your book!)

- The Agony and the Ecstasy by Irving Stone (historical novel) (This might be fiction, but it brings Michelangelo's life and inner world to vivid, unforgettable life. It's the kind of book that makes you feel like you truly know him, flaws and all.)

- Documentaries:

- Michelangelo: Love and Death (2017) (A beautifully produced documentary that offers fresh insights into his complex personality and relationships, especially with Vittoria Colonna.)

- Inside the Vatican: The Sistine Chapel (PBS) (Get a rare, behind-the-scenes look at the conservation efforts and the intricate details of his most famous fresco cycle.)

- The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965 film adaptation of Irving Stone's novel) (Charlton Heston as Michelangelo and Rex Harrison as Pope Julius II? Pure cinematic drama that captures the clash of titans and the sheer scale of the Sistine project!)

Michelangelo's Drawings: The Soul on Paper

While his monumental sculptures and frescoes often steal the show (and understandably so!), Michelangelo's surviving drawings offer a unique, intimate glimpse into his creative process and his relentless pursuit of anatomical perfection and expressive power. These aren't just preparatory sketches; they are masterpieces in their own right, revealing the raw energy of his ideas before they were fully realized in stone or paint.

He used drawing for everything, truly: quick compositional studies to block out monumental ideas, meticulous anatomical observations from secret dissections (a controversial, dangerous, and sometimes illegal practice at the time, but absolutely essential to his unparalleled understanding of the human form), detailed drapery studies to understand how cloth fell and folded, and even for designing intricate architectural elements. It was his laboratory, his sketchbook, and his confessional, all rolled into one. His drawings are characterized by a powerful, almost sculptural line, emphasizing volume and muscularity. You can almost feel the weight and tension in the figures he renders on paper, a direct transfer of his sculptor's mindset. Often, his figures appear in complex, twisting, almost contorted poses, exploring the human body's full expressive potential, pushing its limits in a way that feels both classical and incredibly modern. You can see him working out the terribilità on paper, that raw power and dramatic tension that would explode onto his sculptures and frescoes. This obsessive study of the human figure, his constant sketching and redrawing, was the bedrock of his genius, allowing him to create works that feel profoundly alive and dynamic. Looking at these drawings, for me, it’s like seeing the lightning flash of an idea, raw and untamed, captured on paper before the thunder of the finished masterpiece even begins to roll. It's where the magic truly begins, isn't it?

Early Life and Apprenticeship: The Spark of Genius

Before the colossal statues and breathtaking frescoes, there was a young, often tempestuous boy named Michelangelo Buonarroti. His story truly begins not in the grand studios of Rome, but in the heart of Renaissance Florence.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, born in 1475 in Caprese, a small town near Arezzo, was not your average kid. His family, though of minor nobility, was not wealthy, and his father, Lodovico, initially resisted his artistic inclinations with a stubbornness that, I confess, I can sometimes relate to when I'm told to do something I don't want to do! Lodovico, clinging to a fading aristocratic lineage, viewed manual labor and the guild system associated with art as beneath his family's dignity. He envisioned a more "respectable" profession for his son, perhaps something in commerce or law – anything but the messy, uncertain, and often socially precarious path of an artist. Can you imagine the pressure, a young boy with an undeniable, burning urge to create, constantly clashing with paternal expectations and societal norms, with the added burden of his family's precarious financial situation? It's a familiar human drama, played out against the opulent, yet often harsh, backdrop of one of history's most vibrant eras, Florence. Growing up in Florence during the peak of the High Renaissance – a city absolutely brimming with artistic and intellectual ferment, a vibrant hub where creativity seemed to bloom on every corner, a place you can still feel pulsing with history if you visit today, maybe following an Art Lover's Guide to Florence. It's like being a musician growing up in Nashville, or a tech whiz in Silicon Valley. The stakes were high, the talent pool immense.

Florence itself was a crucible of intellectual and artistic ferment. This wasn't just a city; it was a living, breathing university of humanism, where ancient philosophies were rediscovered, scientific inquiry bloomed, artistic patronage was a civic duty, and a vibrant guild system ensured the highest standards of craftsmanship. Imagine the conversations, the debates, the sheer intellectual energy buzzing through its piazzas and workshops, where artists, philosophers, and merchants mingled, pushing the boundaries of thought and expression. Beyond the formal academies, the city’s very fabric—its bustling markets, its grand cathedrals, its lively public squares—served as an informal school, a constant stimulus for ambitious minds. For a young, impressionable Michelangelo, this environment, rich with both classical heritage and contemporary innovation, was both an immense opportunity and an intense challenge, forcing him to push the boundaries of his budding genius from day one, internalizing the ideals of civic pride and artistic excellence that permeated every stone of the city.

At just 13, he convinced his father – no small feat, I'm sure, given the stubborn streak they both shared, a trait I can personally attest makes negotiations… spirited – to apprentice him to Domenico Ghirlandaio, one of Florence's leading and most prolific fresco painters. Here, amidst the rich pigments, the pungent smell of linseed oil, and the demanding precision of plaster work, he absorbed the rigorous techniques of fresco painting, a skill that requires incredible speed and precision. He wasn't just learning to paint; he was mastering drawing, composition, linear perspective, and the swift, precise application of paint that would later prove invaluable for a certain chapel ceiling he initially wanted nothing to do with! Ghirlandaio's workshop was a bustling, high-pressure hub, constantly buzzing with activity, a true production line for Renaissance art, exposing young Michelangelo to large-scale commissions and the demanding practicalities of running a major artist's studio. Here, he didn't just learn to draw; he learned discipline, speed, and the sheer logistics of massive fresco projects. He meticulously studied Ghirlandaio’s masterful use of light and shadow, the subtle rendering of human emotion, and the intricate details in drapery, absorbing a visual vocabulary that would later define his own monumental style. You can almost see the seeds of his future genius being sown in those early, demanding years. Legend has it, his prodigious talent was almost immediately apparent, bordering on insolence to his older peers and even his master – he reportedly corrected Ghirlandaio's drawings, a move that would surely earn you a stern talking-to today! (Talk about a prodigy with an attitude, but one that certainly got results!). It was during this period that he meticulously copied frescoes by Giotto and Masaccio, internalizing the grandeur and emotional power of earlier masters, laying the deep foundations for his own revolutionary style. He wasn't just copying; he was dissecting their compositions, their drapery, their emotional expression, learning directly from the titans who came before him. This intense early training instilled in him a foundational mastery of the human figure, narrative composition, and the discipline of large-scale projects that would underpin all his later works, even if his heart, from the very beginning, passionately belonged to marble. He stayed with Ghirlandaio for barely a year, leaving before his contract was fulfilled, a testament to his restless ambition and his desire to pursue sculptural forms. It was clear even then that this young artist would not be confined to existing conventions; his spirit yearned for the three-dimensional drama that only sculpture could fully provide, a premonition of the colossal works that would soon erupt from his genius.

Yet, his true calling, his undeniable siren song, whispered in marble. Soon, his path led him to the sculpture garden of Lorenzo de' Medici, 'the Magnificent,' Florence's most powerful patron and a true titan of the Renaissance. This wasn't just a garden; it was an informal academy, a living museum filled with classical antiquities and newly excavated Roman masterpieces, where young talents like Michelangelo could study, sketch, and learn from masters like Bertoldo di Giovanni, a pupil of Donatello and a master of bronze. Under Bertoldo, Michelangelo not only honed his carving skills but also developed a deep reverence for classical sculpture – particularly the powerful forms of Roman sarcophagi and fragments like the awe-inspiring Belvedere Torso, which profoundly influenced his muscular figures and informed his vision of heroic nudes. This exposure to ancient Roman and Greek art, particularly the monumental, idealized forms, was foundational. It was here that he began to truly understand the expressive potential of the human body, not just as a physical entity, but as a vessel for heroic narrative and profound emotion. He wasn't just copying; he was internalizing the very essence of classical grandeur, preparing to reinterpret it for a new age. He learned to imbue his figures with a heroic monumentality that echoed the ancients but vibrated with a new Renaissance intensity. Here, under the direct, discerning gaze of Lorenzo de' Medici, who himself was a poet and philosopher, his unique vision truly began to blossom, nurtured by exposure to ancient ideals of beauty and heroic form, a powerful synthesis of classical grace and emerging Renaissance power that would define his life's work. It was like a masterclass in art and philosophy, all rolled into one, where the study of antiquity merged seamlessly with contemporary humanism, shaping not just his hand, but his mind. His early marble reliefs, like the Madonna of the Stairs (circa 1490-92, a tender, almost intimate domestic scene, yet with a monumental quality that belies its size, already hinting at his future mastery of scale, and notably utilizing the 'schiacciato' or flattened relief technique, a technique he learned from Donatello and pushed to new expressive heights) and the Battle of the Centaurs (circa 1492, a swirling, dynamic composition of struggling nudes that overtly references classical sarcophagi and powerfully foreshadows his later heroic nudes and epic narratives, almost a manifesto of his future sculptural language), already showed a profound understanding of the human form, a nascent 'terribilità,' and a dramatic intensity that would define his career. The Battle of the Centaurs, in particular, with its dense, intertwined figures, is a dizzying display of anatomical mastery and compositional skill, an explosive prelude to the grand dramas he would later carve and paint. It's like seeing the raw, unpolished diamond that you just know will become something breathtaking, a promise of colossal things to come, waiting to be freed from its stony prison. This period in the Medici household also exposed him to leading humanist thinkers, such as Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, further shaping his intellectual and philosophical foundations with the profound ideas of Neoplatonism, which would permeate his entire artistic output.

I often wonder what it must be like to possess such innate, undeniable genius, a talent that seemed to burst forth almost fully formed, like a volcano erupting with pure artistic energy. My own journey as an artist (you can see some of it on my timeline) has been more about persistence than pure prodigy, more about chipping away at my own 'stone' day by day, and honestly, I'm okay with that. But Michelangelo? He was a comet from the start, a force of nature even before he truly knew it. But Michelangelo? He was a comet from the start. He had a temper, a fierce independence, and a belief in his own abilities that bordered on arrogance – traits, I confess, I sometimes see a glimmer of in myself (though hopefully less of the arrogance!). He was a sculptor first and foremost, though he would become a prodigious painter, architect, and poet, truly embodying the ideal of the 'Renaissance Man.' He believed marble already held the form, waiting for him to simply set it free. Now, if that isn't a powerful metaphor for life, I don't know what is. To chip away the excess, to reveal the hidden beauty – it's a philosophy I often reflect on when facing my own blank canvas, wondering what story is waiting to emerge. His burgeoning reputation soon took him beyond Florence. After the death of Lorenzo de' Medici in 1492 and the subsequent political instability – a truly tumultuous period marked by the expulsion of the Medici, the rise of the fiery Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola who preached austerity, burned vanities, and condemned secular art, and a general climate of profound uncertainty – Michelangelo, ever the pragmatist and ambitious artist, felt compelled to leave Florence. The city was undergoing a profound moral and political upheaval, a difficult environment for an artist whose very essence was about celebrating the human form and classical ideals, especially when bonfires of the vanities were literally consuming artistic creations. It was a period of turmoil, where artistic patronage was uncertain, and the city itself was in flux, making Rome, the Eternal City, a beacon for his ambitions. The city was undergoing a profound moral and political upheaval. The fiery Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola, a fervent preacher of austerity and a staunch opponent of the perceived decadence of Renaissance culture, had gained immense influence. He led "bonfires of the vanities" where secular art, books, and luxuries were publicly destroyed, creating a deeply hostile environment for an artist whose very essence was about celebrating the human form and classical ideals. This turbulent period, marked by the expulsion of the Medici and a climate of profound uncertainty, meant that artistic patronage was unstable, making Rome, the Eternal City, with its promise of grand papal commissions, a compelling beacon for his ambitions, a chance for an ambitious young artist to escape the confines of a city in turmoil and truly test his mettle on a grander stage. He found temporary refuge in Bologna (1494-1495), where he completed several figures for the Ark of St. Dominic, including a kneeling angel, a St. Proculus, and a St. Petronius. Even in these less dramatic, smaller-scale commissions, you can already sense the nascent power in his forms, the unmistakable Michelangelo touch, a stepping stone to the monumental works that awaited him. Then, in 1496, he made his first journey to Rome, the Eternal City – a place teeming with classical ruins, newly excavated treasures, and ambitious papal projects. But even before Rome, during his time in Florence after Lorenzo de' Medici's death, he created the exquisite wooden Crucifix for Santo Spirito (c. 1492). This tender work, carved for the Augustinian friars of the Santo Spirito church in gratitude for allowing him to dissect cadavers in their hospital, stands as a testament to his early anatomical studies and his profound engagement with the human form. It's a remarkably intimate piece, far removed from his later monumental scale, revealing a nascent understanding of human suffering and divine grace that is almost startling in its empathetic rendering. This crucifix, carved from polychrome wood, highlights a lesser-known but crucial aspect of his early development: his direct, hands-on study of human anatomy from cadavers, a practice both controversial and invaluable for his later hyper-realistic yet idealized figures. It was a city that breathed ancient grandeur and promised new opportunities. There, in the heart of Christendom, he would carve two of his earliest masterpieces that would cement his burgeoning fame: the Bacchus, a daringly sensual and classical interpretation of the god of wine, a surprising choice that shows his versatility even then, and the profoundly moving Pietà, a work that would establish him as a sculptor of unparalleled tenderness and skill.

David: The Soul of a City, Carved in Stone

Ah, David. My first truly impactful encounter with this colossus of marble was... well, it was humbling. You see it in books, you know it's big, but standing before it in Florence, feeling the sheer scale and the incredible detail, it's something else entirely. It’s over 17 feet of pure, defiant beauty. Carved from a single block of marble – a colossal, fifteen-foot block that had been lying in the Florence cathedral workshop for over 40 years, deemed unusable after other sculptors (including Donatello and Agostino di Duccio) had attempted and abandoned it due to its perceived flaws and awkward shape. Michelangelo took on an immense technical challenge that many deemed impossible. Imagine the audacity! Where others saw only difficulty and an impossible task, a damaged piece of stone, he saw the potential, a heroic figure waiting to be liberated from its stony prison. The block, often referred to as 'the Giant,' was not only narrow and poorly cut but also had existing chisel marks and a large hole from a previous attempt, making it incredibly challenging to work with. Yet, with an almost supernatural intuition, Michelangelo meticulously studied the block for months, drawing numerous sketches, visualizing the figure imprisoned within, reportedly finding a way to incorporate its inherent imperfections into the dynamism of David's pose, turning flaws into features. For instance, the shallow depth of the block meant David is rendered somewhat thinly from front to back, a constraint Michelangelo turned into an advantage by emphasizing the figure's frontal impact and the dramatic tension of the moment. This wasn't just a technical feat; it was an act of profound artistic vision, where he didn't just overcome limitations but transformed them into integral parts of the masterpiece itself. It's a testament not just to his unparalleled technical skill in extracting such a perfect form from such a challenging piece of stone, but to his visionary courage, to look at something 'damaged' and see greatness, a powerful metaphor for his entire artistic philosophy, teaching us that limitations can be the very crucible of creation.

When Michelangelo carved David between 1501 and 1504, it wasn't just a statue; it was a thundering political statement, a declaration of independence in marble. Florence, at the time, was a fiercely independent republic, a relatively small city-state that often felt like a vulnerable David surrounded by powerful Goliaths – whether the recently expelled Medici family, ambitious rival city-states like Milan or Venice, or powerful papal forces intent on extending their dominion. Originally placed with immense ceremony in the Piazza della Signoria, Florence's main civic square, right outside the Palazzo della Signoria (the seat of Florentine government), it served as an unmistakable symbol of the Florentine Republic's defiance against tyranny and external aggressors. This wasn't just art for art's sake; it was a potent, living piece of propaganda, a beacon of republican ideals, a daily, colossal reminder to both citizens and enemies of Florence's strength, courage, and unwavering resolve, a tangible representation of their collective identity and aspirations. It embodied the very civic virtues they wished to project: courage in the face of overwhelming odds, self-reliance, and divine favor, much like a young hero from scripture. It’s hard to imagine a more perfect synthesis of artistic genius and political purpose, a true testament to the power of art to embody a city's soul, and for David to be both a protector and an inspiration.

Later, centuries later, due to concerns about weathering and preservation, the original masterpiece was moved indoors to the Accademia Gallery in 1873, where it stands today, still commanding awe. The process of moving the colossal statue from the Piazza della Signoria to the Accademia was a massive undertaking, requiring specially designed carriages, a special track, and considerable engineering ingenuity, taking four days to traverse the relatively short distance, a testament to its immense weight (over six tons!) and priceless value. A magnificent replica now takes its place in the piazza, ensuring that the spirit of defiance continues to watch over Florence, reminding us that even the most enduring symbols sometimes need a little help to stay protected for future generations.

credit, licence Florence, a small republic surrounded by powerful enemies, saw itself in this young hero, facing down a giant. David isn't depicted after his victory, head held high, proudly displaying Goliath's head, as was common in earlier representations by artists like Donatello. No, he's captured before the fight, in that terrifying, electrifying moment just before action, his youth emphasized by his lean, powerful physique. His muscles are tensed, his brow furrowed in deep, almost painful concentration, eyes narrowed with an almost palpable intensity, scanning the horizon for his adversary, Goliath. Notice the subtle sling resting over his shoulder, a small detail that underscores his reliance not on brute physical force, but on skill, unwavering faith, and sharp intellect – a profoundly potent message for the Florentine Republic, which often felt like a small David against mighty Goliaths. That precise, pregnant moment of intense, focused vulnerability before the storm – it’s a stroke of absolute genius, a psychological masterpiece in marble, and it still speaks volumes to anyone who's ever faced an uphill battle. It's a powerful reminder that true strength often lies not in physical might, but in courage, cunning, and unshakeable conviction, a lesson I try to remember when facing my own seemingly insurmountable tasks. It’s a powerful reminder that true strength often lies not in physical might, but in courage, cunning, and unshakeable conviction, a lesson I try to remember when facing my own seemingly insurmountable tasks.

The Sistine Chapel: A Universe on a Ceiling

And then there’s the Sistine Chapel. I mean, seriously, can we just take a moment? This was a project he didn't even want. He famously resisted, considering himself a sculptor, not a painter, and initially proposed a plan for the tomb that was far grander. But Pope Julius II, a formidable and ambitious patron known as the 'Warrior Pope,' insisted with characteristic force. Julius was driven by an almost imperial ambition to restore the glory of the papacy and make Rome the unrivaled center of Christian art and power, and he saw the Sistine Chapel, the Pope's private chapel, as the perfect canvas for a profound theological and political statement, a visual manifesto of divine authority. He wanted a program that would not only glorify God and the papacy but also implicitly link the papacy's authority to a divine lineage, emphasizing humanity's journey from creation to redemption, presenting a coherent vision of salvation history to the throngs of pilgrims and cardinals who would gather beneath it. It was a clash of titans, patron versus artist, and the artist reluctantly yielded, a decision that would forever change art history, and perhaps, Michelangelo himself. Their relationship was legendary for its intensity, marked by mutual respect, profound frustration, and explosive arguments – a true Italian opera of patronage, where the stakes were not just artistic, but eternal. For four intense years, from 1508 to 1512, Michelangelo essentially lived on his back, painting a narrative masterpiece that would cover 5,000 square feet of ceiling. He famously refused the conventional scaffolding designed by Bramante, which would have required holes in the vault and thus damaged the pre-existing frescoes and the chapel structure itself, and instead devised his own innovative system of wooden platforms cantilevered from brackets in the walls, allowing him to work closer to the ceiling and achieve a unified vision. This ingenious, self-supporting structure not only protected the existing architecture but also allowed Michelangelo greater freedom of movement and a better vantage point for his monumental task. I get tired just thinking about painting a small canvas in my studio, let alone that. I get tired just thinking about painting a small canvas in my studio, let alone that. Imagine the neck cramps so severe he could barely look down, the paint and plaster dust constantly dripping into his eyes, the sheer physical strain of working overhead for such extended periods, often in isolation, plagued by self-doubt and the constant pressure of his demanding patron. These were grueling conditions, which he often complained about in his letters and poems. It makes my own artistic endeavors feel like a leisurely stroll through a park! (Though, let's be honest, they're not always that either).

It’s a visual Bible, a sweeping narrative from the Creation to the Flood, arranged in nine central panels depicting scenes from the Book of Genesis. Starting from the altar, the narrative progresses chronologically from the Separation of Light from Darkness, then the monumental Creation of the Sun, Moon, and Plants, the Separation of the Land and Water, the Creation of Adam (that iconic moment!), the Creation of Eve, the Temptation and Expulsion (a powerfully dramatic portrayal of both sin and its consequences), the Sacrifice of Noah, and culminates with the poignant Drunkenness of Noah. It’s a carefully conceived theological journey, guiding the viewer through salvation history. At its heart is arguably the most famous fresco in history: The Creation of Adam. That iconic image of God, dynamic and muscular, surrounded by angelic figures (and perhaps Eve-to-be, sheltering under God’s protective arm, a sublime prefiguration of salvation!), reaching out to touch Adam's languid, almost receptive, finger – it’s not just a religious scene; it's the very spark of life itself, the divine connection, the moment humanity receives its soul, rendered with such breathtaking dynamism and profound emotional resonance it still makes me shiver. This iconic moment, infused with powerful Neoplatonic philosophy—which posits that physical beauty and intellectual contemplation are pathways to understanding the divine—symbolizes the infusion of the divine into the human, the awakening of intellect and soul, and the potential for humanity to ascend towards God. The entire ceiling unfolds as a complex, meticulously planned visual Bible, progressing from the weighty tales of Creation, through the fall of man, and culminating in the tragic Flood, all designed to guide the viewer through salvation history, a monumental theological statement painted on a grand scale that speaks to humanity’s journey from its divine origin to its ultimate fate. While primarily known for his frescoes, it's worth noting his only undisputed panel painting, the Doni Tondo (or Holy Family), completed around 1507. This vibrant, circular oil painting, commissioned for Florentine merchant Agnolo Doni and likely intended to commemorate his marriage to Maddalena Strozzi, stands out with its vivid colors and complex, twisting figures, almost a sculptural composition rendered in paint, showcasing his evolving mastery of the medium even before the Sistine Chapel, particularly in its rich, luminous palette and intricate figure arrangements. The unusual, almost acrobatic poses of the figures, particularly the Christ Child and St. John the Baptist in the background, are a clear precursor to the ignudi and other dynamic figures of the Sistine Chapel, revealing a distinct preference for idealized, muscular forms even in a domestic religious scene. It's a powerful foreshadowing of the dynamism and color palette he would later unleash on the papal ceiling, a true hidden gem of his painting career. Surrounding these central narratives are monumental figures of prophets (like Isaiah and Jeremiah) and sibyls (pagan prophetesses), each embodying a profound emotional and spiritual intensity, foretelling Christ's coming. These figures are masterclasses in psychological portraiture, each conveying a distinct mood and internal struggle, sitting within trompe l'oeil architecture that creates an illusion of three-dimensional space. And then there are the ignudi, the magnificent, powerfully muscled nude male figures perched above the architectural elements. These aren't just decorative flourishes; they seemingly exist purely for their artistic beauty and anatomical perfection. These figures, holding ribbons and medallions, have long fascinated scholars who debate their symbolic significance, forming one of the most compelling enigmas of the ceiling. Are they angelic beings, witnessing God’s creations? Are they allegories of the human soul striving for divine connection, caught between the earthly and the celestial? Are they representations of classical ideals of beauty and strength, a nod to the ancient world that so inspired the Renaissance, perhaps even figures from classical mythology appropriated for a Christian context? Another compelling theory suggests they represent the human desire for knowledge and beauty, perhaps even embodying different stages of human perfection before the fall. Their muscular, idealized forms, drawn directly from his deep anatomical studies, serve as a bridge between the physical and the spiritual narratives unfolding below, celebrating the dignity and potential of humanity, created in God’s image. For me, they are a bold, almost audacious, declaration of the beauty of the human form itself, a central tenet of the Renaissance that Michelangelo, the sculptor, championed with every fiber of his being. They stand as a testament to humanity's potential, both physical and spiritual, and a powerful assertion that the human body is, in itself, a divine work of art. Some theories even propose they represent the transition between the Old Testament narratives and the figures of prophets and sibyls, acting as symbolic bridges or purely aesthetic complements. It’s about more than just faith; it’s about existence, humanity's place in the divine order, and the sheer, breathtaking expressive power of the human body, a contemplation of beauty for beauty's sake, in a truly sacred space that forces us to reconcile the divine and the gloriously human. Later, much later, almost twenty-five years after completing the ceiling, from 1536 to 1541, he returned to paint The Last Judgment on the altar wall. This monumental work, spanning the entire wall, presents a darker, more dramatic, almost apocalyptic vision than the soaring optimism of the ceiling. It’s a powerful reflection not only of the artist's own profound spiritual anxieties and deepening introspection in his old age but also of the turbulent times of the Counter-Reformation (the Catholic Church's fierce, often zealous, response to the Protestant Reformation, which challenged its authority and doctrines with a renewed focus on doctrine and moral rectitude) and the devastating Sack of Rome in 1527 (a brutal military occupation that saw widespread looting, destruction, and a profound crisis of faith for many). These cataclysmic events deeply impacted Michelangelo, fostering a more somber, introspective, and even despairing worldview, a stark contrast to the youthful vigor of the ceiling frescoes. The shift in tone from the optimistic humanism of the ceiling to the stark, almost terrifying judgment on the altar wall perfectly encapsulates the profound spiritual and political anxieties gripping Europe during his later life, reflecting a Church desperately trying to reassert its authority in a fragmented world and an artist grappling with his own mortality and ultimate salvation. The shift in tone from the optimistic humanism of the ceiling to the stark, almost terrifying judgment on the altar wall perfectly encapsulates the profound spiritual and political anxieties gripping Europe during his later life, reflecting a Church desperately trying to reassert its authority in a fragmented world. It's a painting that doesn't just depict judgment; it feels like judgment. It’s a raw, visceral outpouring of human fate, a stark reminder of mortality and divine judgment, and an intense reflection of the spiritual turmoil of its age. Experiencing something like that in person, feeling the history and the human effort, really puts things in perspective. It's why I believe so strongly in the immersive power of art, something we try to capture in our own museum experience in Den Bosch.

credit, licence Commissioned by Pope Paul III, this swirling panorama of damned and saved souls, with Christ as a powerful, almost wrathful judge, challenged artistic and theological conventions and ignited fierce controversy. Its extensive nudity, in particular, drew the ire of critics like Biagio da Cesena, the Papal Master of Ceremonies, who famously declared it more fit for a public bath than a sacred chapel. This controversy, known as the "Fig-Leaf Campaign," which began even before Michelangelo's death, eventually led to parts of the fresco being later painted over by Daniele da Volterra, Michelangelo’s assistant, for modesty – a task that earned him the unfortunate nickname "Il Braghettone" (the breeches-painter)! Michelangelo, in his characteristic prickly fashion, immortalized Cesena as Minos, judge of the underworld, complete with ass’s ears and a serpent biting his genitals – a testament to his biting wit and disdain for his detractors, proving even a pope’s master of ceremonies was not immune to his artistic vengeance! It's a raw, visceral outpouring of human fate, a stark reminder of mortality and divine judgment, and an intense reflection of the spiritual turmoil of its age, capturing the fear and hope of an entire era. It's a raw, visceral outpouring of human fate, a stark reminder of mortality and divine judgment, and an intense reflection of the spiritual turmoil of its age. Experiencing something like that in person, feeling the history and the human effort, really puts things in perspective. It's why I believe so strongly in the immersive power of art, something we try to capture in our own museum experience in Den Bosch.

Michelangelo's Later Years and Enduring Influence

Even in his final decades, Michelangelo remained incredibly active and productive, though his focus shifted increasingly towards architecture and poetry. He spent much of his later life in Rome, overseeing the construction of St. Peter's Basilica, a task he considered a sacred duty, dedicating himself to it without salary for 18 years. Despite personal losses (like the death of Vittoria Colonna in 1547), recurring bouts of illness, and the general hardships of old age, his creative fire never diminished. He continued to draw, sketch, and even began a new series of Pietàs (the Florentine Pietà and the Rondanini Pietà), which show a profound stylistic shift towards a more attenuated, almost abstract form, reflecting a deeper spiritual contemplation and a return to the 'non-finito' to express emotional rawness rather than physical perfection. The Florentine Pietà, intended for his own tomb, depicts a dramatically struggling Nicodemus (or perhaps a self-portrait of Michelangelo) supporting the dead Christ, while Mary Magdalene looks on. The Rondanini Pietà, his very last work, left unfinished at his death, is perhaps the most moving: a slender, elongated Christ almost merging with Mary, a haunting vision of shared suffering and spiritual fusion, devoid of classical idealization and reflecting a deeply personal spiritual journey. These late works are less about monumental heroism and more about intimate suffering and quiet devotion, revealing a master still evolving, still searching for new ways to express the inexpressible, grappling with themes of mortality and salvation until his very last breath. For instance, the Florentine Pietà, initially intended for his own tomb, dramatically depicts a struggling Nicodemus (or perhaps a self-portrait of Michelangelo, bearing the immense burden of the dead Christ), while Mary Magdalene looks on, a powerful reflection of personal faith and the weight of human suffering. The Rondanini Pietà, his very last work, left unfinished at his death, is perhaps the most moving: a slender, elongated Christ almost merging with Mary, a haunting vision of shared suffering and spiritual fusion, devoid of classical idealization and revealing a deeply personal, almost abstract, spiritual journey. These pieces are profoundly different from the idealized Pietà of his youth, showcasing a powerful shift from external perfection to internal, raw emotion, reminding us that even in old age, true genius continues to find new forms of expression.

He died in Rome on February 18, 1564, just shy of his 89th birthday, leaving behind a legacy unmatched in its scope and influence. His body was, according to his wishes, secretly brought back to Florence, the city of his artistic birth, and buried with great ceremony in the Basilica of Santa Croce, cementing his place among Florence's most celebrated sons. His impact, as we've seen, reverberated for centuries, shaping not just the Renaissance but subsequent movements like Mannerism and Baroque.

Pietà: Tender Sorrow, Masterfully Rendered

The Pietà is a piece that, for me, embodies profound tenderness and sorrow, all within the cold hardness of marble. Carved when he was only 24 (just let that sink in for a moment – at that age, I was still trying to figure out how to boil pasta!), it depicts Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus after the Crucifixion. This monumental work was commissioned by Cardinal Jean de Bilhères-Lagraulas, a French cardinal in Rome, for his tomb in Old St. Peter's Basilica, with a very specific, and ambitious, contractual requirement for "the most beautiful work in marble that exists today in Rome." The contract, signed in 1498, also stipulated that the work be completed within one year and be "acceptable to all experts." Talk about pressure! And Michelangelo delivered, infusing a potentially melodramatic subject with an almost unbearable grace, surpassing all expectations and securing his reputation as a sculptor of prodigious talent, even at such a young age. The technical mastery required to carve such delicate drapery and human forms from a single block of marble was astounding, immediately elevating him above his contemporaries and silencing any doubts about his prodigious skill. Mary's youthful appearance has often been discussed – a point of contention even in Michelangelo's own time. Some interpret it as symbolizing her eternal purity and virginity, untainted by sin or age, others as representing the timelessness of a mother's grief, universal and unending. For me, it feels like a deliberate, profound choice to elevate the emotional impact beyond mere realism, focusing on the universal feeling of sorrow and grace rather than a literal age, pushing past mere literalism to a higher, more symbolic truth. Michelangelo himself, reportedly challenged on Mary's youth by onlookers, responded with characteristic sharpness, stating, "Do you not know that chaste women retain their youth longer than those who are not chaste?" – a powerful artistic, theological, and perhaps even a little cheeky, statement wrapped in marble, typical of his often sharp-tongued responses to critics. This intentional idealization, rather than strict naturalism, speaks volumes about his artistic philosophy, where the divine ideal was paramount, and earthly beauty served as a window to higher truths. It’s a genius move, really, to transform potential criticism into an affirmation of divine purity, emphasizing spiritual grace over earthly age. This intentional idealization, rather than strict naturalism, speaks volumes about his artistic philosophy, where the divine ideal was paramount. The work's smooth, polished surface and the exquisite finish are also notable, showcasing Michelangelo's early mastery of marble before his later embrace of the 'non-finito.' Every surface, from the tender skin of Christ to the flowing folds of Mary's garments, is rendered with breathtaking realism and meticulous attention to detail, a stark contrast to the rougher, more evocative surfaces of his later, unfinished works. This deliberate perfection speaks to his youthful ambition to demonstrate complete command over his material, creating a piece of such ethereal beauty that it almost transcends the physical.

If you've ever experienced deep grief, you recognize the quiet devastation in Mary's face, the impossible weight of her son's body. The exquisite way the fabric drapes, with such naturalistic folds and a sense of monumental weight, perfectly complementing the graceful curve of Mary's form, the palpable texture of the flesh, the meticulous rendering of sinews and bones beneath the skin, the vulnerability and strength woven together – it’s a masterclass in human emotion, anatomical accuracy, and sculpted with unparalleled skill. The intricate detail in Mary's voluminous drapery serves not only a compositional purpose but also highlights the artist's profound technical virtuosity in transforming cold marble into flowing cloth. In a rare, almost defiant moment of asserting authorship, Michelangelo carved his name across Mary's sash – MICHAEL.ANGELVS.BONAROTVS.FLORENT.FACIEBAT (Michelangelo Buonarroti of Florence Made It). This act of signing, deeply unusual for an artist of his stature in that era, was the only time he ever inscribed his name on a major work, almost as if to say, "This one is mine, and you'd better remember it!" The story goes that he overheard a group of onlookers attributing the masterpiece to a different, less famous sculptor, Cristoforo Solari, a rival from Lombardy, and in a fit of pride and youthful indignation (and perhaps a touch of ego, let's be honest!), he returned to carve his name, ensuring his authorship was clear for all eternity. He was reportedly quite upset about the misattribution, a testament to his pride in his work, a very human response for someone who poured so much of himself into his creations. It makes you realize that even for a genius, recognition could be fleeting, and pride in one's creation a powerful force, almost a human need, isn't it? True power in art isn't always about grand gestures, but often about capturing the most intimate, vulnerable moments, and sometimes, making sure everyone knows you were the one who captured them, for all eternity, a timeless assertion of artistic identity. It makes you realize that even for a genius, recognition could be fleeting, and pride in one's creation a powerful force, almost a human need, isn't it? True power in art isn't always about grand gestures, but often about capturing the most intimate, vulnerable moments, and sometimes, making sure everyone knows you were the one who captured them, for all eternity.

The Tragic Masterpiece: Pope Julius II's Tomb

Among Michelangelo's most celebrated yet ultimately frustrating commissions was the tomb of Pope Julius II, a project that consumed over four decades of his life and became a source of immense personal anguish, what he later called "the tragedy of the tomb." My heart goes out to him; we all have those projects that just seem to drag on and on, don't we? This commission, begun in 1505, was initially envisioned as a colossal, multi-tiered structure with over 40 life-size statues – a veritable mountain of marble, almost a freestanding mausoleum, that would have been the grandest funerary monument in Christendom, a testament to the "Warrior Pope's" imperial ambition and Michelangelo's boundless vision. Imagine the sheer audacity and ambition! This project, however, became an artistic albatross, spanning over 40 years of his life and repeatedly scaled back and revised due to fluctuating papal finances, Julius II's shifting priorities (he famously diverted Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel!), and the political machinations of the Roman Curia. The initial design alone would have required Michelangelo to spend years in the Carrara quarries, personally selecting the marble, overseeing its extraction and transport, a testament to his dedication and the project's monumental scale, a true testament to the artist's unwavering commitment to his vision, even when his patron was notoriously fickle. But with the Pope's changing whims, the project was reduced to a wall tomb, then further simplified, becoming a constant source of lawsuits, bitter disagreements, and profound personal anguish for Michelangelo, a tragic masterpiece of unfulfilled potential that haunted him until his death. He called it "the tragedy of the tomb," and honestly, I get it. We all have those projects that just won't die, right?

While David, the Sistine Chapel, and the Pietà are his undisputed megahits, Michelangelo was far from a one-trick pony. The tomb of Pope Julius II, a commission he began in 1505, was initially envisioned as a colossal, multi-tiered structure with over 40 life-size statues – a veritable mountain of marble that would have been the grandest funerary monument in Christendom, a monument to the "Warrior Pope's" imperial ambition. Imagine the sheer audacity and ambition! This project, however, became an artistic albatross, spanning over 40 years of his life and repeatedly scaled back and revised due to fluctuating papal finances, Julius II's shifting priorities (he diverted Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel!), and the political machinations of the Roman Curia. It became a source of immense personal anguish and profound frustration for the artist, a tragic masterpiece of unfulfilled potential that haunted him until his death. The sheer scale of the original design speaks volumes about both Julius's almost imperial ego and Michelangelo's unparalleled, often unrestrained, vision. It was meant to be a statement for eternity, a monument to papal power and artistic genius, a truly epic undertaking that ultimately became a symbol of creative struggle. Its centerpiece, the monumental figure of Moses (completed around 1515), is a testament to Michelangelo's unparalleled ability to imbue cold marble with raw, simmering, almost volcanic emotion. Depicting the prophet with the Tablets of the Law clutched in his hand, his dynamic pose, furrowed brow, and piercing gaze capture a moment of intense, barely contained fury, a visceral reaction to seeing his people worship the Golden Calf. He seems on the very verge of rising, of shattering the tablets, a force of divine wrath frozen in stone, a perfect embodiment of the concept of 'terribilità' – awesome grandeur and intense emotional power, a figure so alive you almost expect him to thunder. The iconic "horns" on Moses' head are a result of a literal (and now somewhat controversial) translation of the Hebrew word 'karan' (meaning 'radiant' or 'emitting rays' of light from his face, as described in the Book of Exodus) into Latin as 'cornutus' (horned), a fascinating philological detail that only adds to the sculpture's enduring mystique and powerful symbolism, inviting endless interpretation and debate about his divine connection. It’s a powerful example of how translation can dramatically shape our understanding of an ancient text, and in this case, a masterpiece, turning a prophet into an almost mythological, horned figure. The statue was initially intended to be placed much higher on the multi-tiered tomb, specifically on the second tier and designed to be viewed from below, which explains the slightly elongated proportions and the powerful, upward-looking gaze that make it so impactful at eye level today. His genius lay in anticipating the viewer's perspective and adjusting the sculpture accordingly, ensuring its dramatic effect would be maintained regardless of its ultimate placement.

Also intended for the tomb, though ultimately removed from the final, much-reduced monument, were the powerful Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave, along with the four so-called 'Captives' now in the Accademia Gallery in Florence. These figures, now housed in the Louvre and Accademia respectively, perfectly embody Michelangelo's 'non-finito' (unfinished) style. They appear to writhe and struggle, almost agonizingly, for release from the stone, capturing not just a physical struggle but perhaps the universal human experience of constraint, longing, and the aspiration for freedom – both physical and spiritual. It’s as if the figures are truly trapped within their material prison, waiting for the master to set them free, a powerful visual metaphor for his own artistic philosophy, where the sculpture is revealed rather than created. The 'non-finito' here isn't merely incompleteness; it's a profound, deliberate artistic statement, inviting the viewer to engage directly with the raw material and the artistic process itself, suggesting the enduring human struggle against earthly bonds, and indeed, the very process of creation itself. It’s a bold, almost defiant, embrace of the un-finished, allowing the viewer to fill in the gaps with their own imagination and empathy, making the viewer a silent collaborator in the artist’s vision, a powerful testament to the idea that the creative process itself is as profound as the finished product. Two other completed figures for the tomb, Rachel and Leah, representing Contemplative Life (Rachel, with her gaze directed heavenward, symbolizing faith and meditation) and Active Life (Leah, holding a mirror and a wreath, symbolizing labor and virtuous action) respectively, were integrated into the much-reduced final monument in San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome, adding to the psychological depth and complex allegorical program of the overall design. These figures, though less dramatic than Moses, demonstrate Michelangelo's continued exploration of human experience and spiritual allegories, even within the confines of a perpetually frustrating commission. The 'non-finito' here isn't merely incompleteness; it's a profound, deliberate artistic statement, inviting the viewer to engage directly with the raw material and the artistic process itself, suggesting the enduring human struggle against earthly bonds, and indeed, the very process of creation itself. It’s a bold, almost defiant, embrace of the un-finished, allowing the viewer to fill in the gaps with their own imagination and empathy. ## Architect of Empires: From Chapels to Basilicas

While his sculptural and painting achievements often overshadow his architectural genius, Michelangelo left an indelible mark on Florence and Rome, designing structures that reshaped the urban landscape and pushed the boundaries of Renaissance design. The Medici Chapel, or New Sacristy, in Florence, is a sublime and haunting integration of architecture and sculpture, a funerary monument that feels less like a chapel and more like a profoundly meditative, sculptural environment. Commissioned by the Medici family (Pope Leo X and Clement VII), it houses the tombs of Giuliano and Lorenzo de' Medici (not the Magnificent!), adorned with Michelangelo's allegorical figures of Night, Day, Dawn, and Dusk. These reclining figures, heavy with symbolism and often depicted in strained, twisting, and almost contorted poses, express a profound melancholia and psychological depth that resonates with anyone who has contemplated the passage of time and the oppressive weight of human existence. The dynamic interplay between the polished marble figures and the architectural setting creates a powerful, almost unsettling, emotional resonance, where the viewer is invited to reflect on the inexorable march of time and the fragility of human ambition, even in death. Night is shrouded in weary sleep, an owl lurking in the shadows, a powerful symbol of unknowing; Day is a powerfully muscled, unfinished male nude, struggling from the stone, representing raw, untamed force; Dawn awakens with a look of existential dread, a metaphor for the pain of existence; and Dusk sinks into thoughtful weariness, embodying the quiet resignation of evening. Each figure, positioned dynamically on the sarcophagi, seems to embody the inescapable cycle of time and the human condition's inherent struggles, transforming the funerary chapel into a profound meditation on life, death, and the passage of generations. It's a space that truly feels a certain way, a masterpiece of emotional architecture. Each figure is a masterclass in psychological portrayal, creating a space of profound introspection. Night is shrouded in weary sleep, an owl lurking in the shadows; Day is a powerfully muscled, unfinished male nude, struggling from the stone; Dawn awakens with a look of existential dread; and Dusk sinks into thoughtful weariness. The architectural elements – the niches, pilasters, and cornices – are sculpted with the same precision and expressive power as his figures, creating a harmonious, if decidedly somber, whole, where every detail contributes to the overall introspective mood. It's a space that feels deeply personal, designed to evoke deep contemplation on mortality, the fleeting nature of earthly power, and the inescapable march of time. Another architectural marvel in Florence is the Laurentian Library (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana), commissioned by the Medici family to house their vast collection of manuscripts. This wasn't just a library; it was a powerful statement of intellectual prestige and a groundbreaking architectural experiment, a true precursor to Mannerism. Its striking vestibule, with its monumental, triple-branched staircase that seems to pour down like a viscous waterfall, or perhaps a petrified lava flow, dominates the space, almost overwhelming the viewer with its dramatic presence, practically inviting you to experience it as a sculpture in itself. This dramatic, somewhat disorienting design, where colossal columns are recessed into walls as if trapped, and windows are blind or serve purely decorative purposes, is an early and quintessential example of Mannerist architecture. The very walls seem to undulate, and the architectural elements, such as the paired columns and pilasters, are often purely decorative or even structurally ambiguous, creating a deliberate tension and sense of compressed energy that challenged the harmonious and rational ideals of the High Renaissance. It’s like a building that's actively messing with your perceptions, playing with architectural conventions, pushing and pulling at classical forms, and I, for one, absolutely love how it defies expectations, forcing you to reconsider what architecture can be. He deliberately played with classical forms, subverting expectations; for instance, the columns don't support anything, and the wall-mounted corbels appear to hang precariously, creating a deliberate tension and sense of compressed energy, challenging the harmonious and rational ideals of the High Renaissance. It’s like a building that's actively messing with your perceptions, playing with architectural conventions, pushing and pulling at classical forms, and I, for one, absolutely love how it defies expectations, forcing you to reconsider what architecture can be. It's a powerful statement about intellectual freedom and artistic audacity. It's playful, powerful, and deliberately unsettling, challenging the harmonious and rational ideals of the High Renaissance, almost as if Michelangelo was having a subtle, architectural chuckle. It’s like a building that's actively messing with your perceptions, playing with architectural conventions, pushing and pulling at classical forms, and I, for one, absolutely love how it defies expectations, forcing you to reconsider what architecture can be. It’s an intellectual puzzle, designed to be experienced rather than simply observed, a truly revolutionary space that still feels incredibly modern. And let's not forget his later years, when he took over the design of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, leaving his indelible mark on one of the world's most iconic buildings with its awe-inspiring dome.

credit, licence Taking over as chief architect in 1546, at the ripe old age of 71, Michelangelo inherited a complex, fragmented project that had seen several architects come and go (including Bramante, Raphael, and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger), each leaving their own mark and creating a somewhat disunified design. He simplified Bramante's original Greek cross plan, unifying the exterior, introducing colossal orders (a single order of columns or pilasters that extends for two or more stories, creating a powerful sense of verticality and grandeur), and giving the basilica its majestic, soaring presence and sense of cohesive power. His vision was to imbue the structure with the same muscularity, drama, and unified monumentality he brought to his sculpture, rejecting some of the more elaborate or fragmented proposals of his predecessors and striving for a powerful, centralized design. Though he died before its completion, his design for the dome – a revolutionary double-shelled structure that ingeniously combined structural integrity with breathtaking aesthetic grace, directly influencing future domes like St. Paul's in London and countless others – was faithfully executed, remaining a symbol of papal Rome, architectural brilliance, and human ingenuity. He also simplified the complex ground plan, aiming for a more unified and majestic exterior, and introduced the colossal order of pilasters that sweep up the facade, integrating the different levels into a cohesive whole, transforming a collection of disparate ideas into a singular, monumental statement of faith and power. His vision transformed the fragmented project into a monument of unparalleled grandeur and structural harmony, a true synthesis of his sculptural and architectural sensibilities. Standing beneath it, you can't help but feel utterly insignificant and yet profoundly connected to something vast and eternal, a testament to what human creativity can achieve. The man was a polymath, a true Renaissance Man in every sense of the word, constantly pushing boundaries and mastering diverse forms. (For more on this incredible period, check out our Ultimate Guide to Renaissance Art). I mean, I sometimes struggle to pick a Netflix show, and this guy mastered sculpture, painting, architecture, and poetry. It puts my own ambitions into a rather humbling perspective, but also an inspiring one – what more could I learn? What other mediums could I explore?

Architectural Masterpieces Beyond St. Peter's: The Capitoline Hill

While St. Peter's is his crowning architectural achievement, Michelangelo's work on the Campidoglio, or Capitoline Hill, in Rome, commissioned by Pope Paul III in 1538, is another monumental testament to his urban planning and architectural genius. He transformed what was once a chaotic, asymmetrical medieval square into a harmonious, classical masterpiece, a truly revolutionary act of urban design. His design included the renovation of the Palazzo dei Conservatori and the Palazzo Senatorio, and the construction of the Palazzo Nuovo (though completed posthumously), creating a unified facade that embraced the classical past while looking to the future, essentially creating a new, coherent civic center. The most striking feature is the trapezoidal piazza, deliberately designed to counteract the hill's awkward, irregular shape and give a sense of classical order where none existed before, and the magnificent Cordonata, a gently sloping ramped staircase that leads visitors grandly to the square, almost like a ceremonial ascent, rather than a steep, forbidding climb. The pavement design, a subtle, intricate oval pattern radiating from its center, creates a powerful optical illusion, drawing the eye upwards and outwards, making the piazza appear larger and more perfectly proportioned than it actually is, unifying the entire complex. This was more than just a decorative choice; it was a masterful stroke of urban design, subtly altering the perception of space and movement, guiding the visitor's eye and creating a monumental, processional approach to the civic center, culminating in the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius (then mistakenly believed to be Constantine) at its heart. It feels like he sculpted the very air and space of the city, not just its buildings, a truly immersive experience of his genius, where every element contributes to a carefully choreographed spatial and visual experience. This was not just architecture; it was a total urban design, creating a civic space that was both functional and aesthetically profound, a powerful expression of papal authority and Roman glory. It feels like he sculpted the very air and space of the city, not just its buildings, a truly immersive experience of his genius.

Michelangelo and the Human Form: An Obsession

It’s impossible to talk about Michelangelo without delving into his almost obsessive, lifelong fascination with the human form. For him, the human body, particularly the idealized male nude, was the ultimate vehicle for expressing divine beauty, spiritual struggle, and heroic potential. He didn't just depict bodies; he imbued them with soul, raw emotion, and an almost palpable inner life. His figures are muscular, dynamic, often idealized, yet profoundly, intensely human. His anatomical studies, often conducted by secretly dissecting cadavers – a controversial, dangerous, and sometimes illegal practice at the time – were revolutionary. This wasn't merely for academic accuracy; it was to understand the underlying structure, the tension of muscles, the intricate network of veins, the weight of bones, so he could manipulate and exaggerate them for maximum expressive impact, creating figures that felt hyper-real, more alive than life itself, to make his figures truly live and breathe on stone or fresco. When you look at David, or the ignudi on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, you're not just seeing a beautiful body; you're seeing a body that tells a story, a vessel for profound Neoplatonic ideas about strength, vulnerability, creation, and divine grace. For Michelangelo, profoundly influenced by Neoplatonic thinkers like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, earthly beauty, especially the perfected human form, was a direct reflection of divine beauty and a pathway to understanding God. He believed that the human soul, created in God's image, could ascend to the divine through contemplation of beauty, moving from the physical to the spiritual. His idealized figures weren't merely beautiful; they were meant to elevate the viewer's soul, inspiring contemplation of the divine order and humanity's inherent nobility, making his art a profound spiritual experience, a silent sermon in stone and paint that sought to reveal the divine within the human. He saw the human body as the pinnacle of God’s own perfection, a reflection of the divine, and through his art, he sought to elevate it to its most sublime form, often pushing anatomical realism into the realm of the heroic and the monumental, almost creating a new, more perfect human. He saw the human body as the pinnacle of God’s own perfection, a reflection of the divine, and through his art, he sought to elevate it to its most sublime form, often pushing anatomical realism into the realm of the heroic and the monumental, almost creating a new, more perfect human. It's a powerful reminder that art can transform the ordinary into the extraordinary, simply by looking deeper, by truly seeing the soul within the physical.

Why Michelangelo Still Matters: A Legacy That Echoes

So, why do we still talk about Michelangelo with such reverence? For me, it's not just about the technical brilliance, though that's undeniable. It’s about the raw human emotion, the ambition, the struggle, the sheer force of will that he poured into every piece. It's also about his profound spirituality and the way he channeled his faith and inner turmoil into transcendent art. He elevated art, pushing the boundaries of what sculpture and painting could achieve, influencing countless artists who followed. His dramatic, muscular forms, the raw emotional power (often termed 'terribilità'), and profound psychological depth were a hallmark of the High Renaissance and set a new, almost impossible, standard for artistic expression. His influence on subsequent sculpture is particularly profound; nearly every sculptor for centuries after him grappled with his innovations in carving, composition, and emotional expression. Indeed, his bold experimentation, emotional intensity, and even his 'non-finito' approach served as a crucial, electrifying bridge to the next artistic movement, Mannerism. Indeed, his bold experimentation, emotional intensity, and even his 'non-finito' approach served as a crucial, electrifying bridge to the next artistic movement, Mannerism. This style, which emerged after the harmonious and balanced ideals of the High Renaissance, embraced artifice, elongated forms, complex compositions, and often a deliberate distortion of reality, directly inspired by the dramatic tension, psychological depth, and sometimes unsettling beauty of Michelangelo's later works, such as the Last Judgment and the Medici Chapel figures. Think of artists like Jacopo Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino, Bronzino, or Parmigianino, who took his dramatic forms and pushed them into new, more stylized, and often highly subjective directions, valuing a sophisticated artifice and elegant complexity over the balanced naturalism of the High Renaissance. They saw his work and thought, 'How can we make it even more intense, more dramatic, more intellectually intricate, even if it meant distorting reality for expressive effect?' It's like they took his volume knob and cranked it all the way up! This deliberate departure from classical ideals, prioritizing sophisticated intellectualism over naturalism, was deeply indebted to Michelangelo's bold explorations of form and emotion.

Later still, the theatricality, grand scale, and intense emotional fervor of the Baroque period, spearheaded by artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini (whose own dynamic David, twisting in action, directly references and dramatically expands upon Michelangelo's quieter, pre-action hero, almost as if picking up exactly where Michelangelo left off, mid-swing!) and Caravaggio (whose dramatic chiaroscuro and intense realism owe much to Michelangelo's psychological depth and emotional intensity), clearly drew upon the dramatic power, psychological depth, and monumental scale inherent in Michelangelo's creations. His figures, bursting with energy and emotion, often in complex, twisting poses, paved the way for the dynamic narratives and heightened drama characteristic of the Baroque, emphasizing movement, grandeur, and heightened emotion. He essentially provided the emotional and formal vocabulary that later artists would expand upon, creating a lineage of artistic innovation that stretches across centuries, echoing in everything from Ruben's vibrant canvases to Borromini's dynamic architecture, proving that a true master's influence never truly fades. It’s like he laid the groundwork, and others built magnificent, soaring cathedrals on it, each adding their own magnificent flourish.

His story is a powerful reminder that true genius often comes intertwined with intense passion, tireless dedication, and, yes, a healthy dose of stubbornness. It inspires me to keep pushing my own artistic boundaries, to explore new ideas for my art for sale, and to embrace the challenging, exhilarating journey of creation, much like he did. But beyond that, his art asks us to engage, to feel, to question – it's art that demands a response, and that, I believe, is its greatest legacy.

The Pen and the Passion: Michelangelo as Poet

Beyond chisel and brush, Michelangelo also found profound expression in words, composing over 300 sonnets and madrigals throughout his life. These poems, written primarily in his later years, offer a rare, intimate, and often poignant glimpse into his inner world – a world filled with profound spiritual struggles, artistic anxieties, and a passionate, yet often solitary, nature. His verses often explore profound themes of divine love (frequently expressed through Neoplatonic ideals, where earthly beauty serves as a pathway to the divine, echoing his artistic philosophy), human suffering, the beauty and burden of art, and the soul's yearning for God, revealing a deep intellect and a soul wrestling with complex philosophical and theological questions, particularly in the turbulent wake of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. He often grappled with the tension between earthly and divine love, finding in the former a reflection of the latter, elevating human emotion to a spiritual plane. His poetry is not always easy reading; it's dense, often melancholic, but powerfully authentic, like a direct line into the mind of a genius grappling with his faith and his mortality, exposing a vulnerability rarely seen in his monumental public works. Many of his sonnets are structured as dialogues, further highlighting his internal debates and intellectual struggles. His poetry is not always easy reading; it's dense, often melancholic, but powerfully authentic, like a direct line into the mind of a genius grappling with his faith and his mortality, exposing a vulnerability rarely seen in his monumental public works.