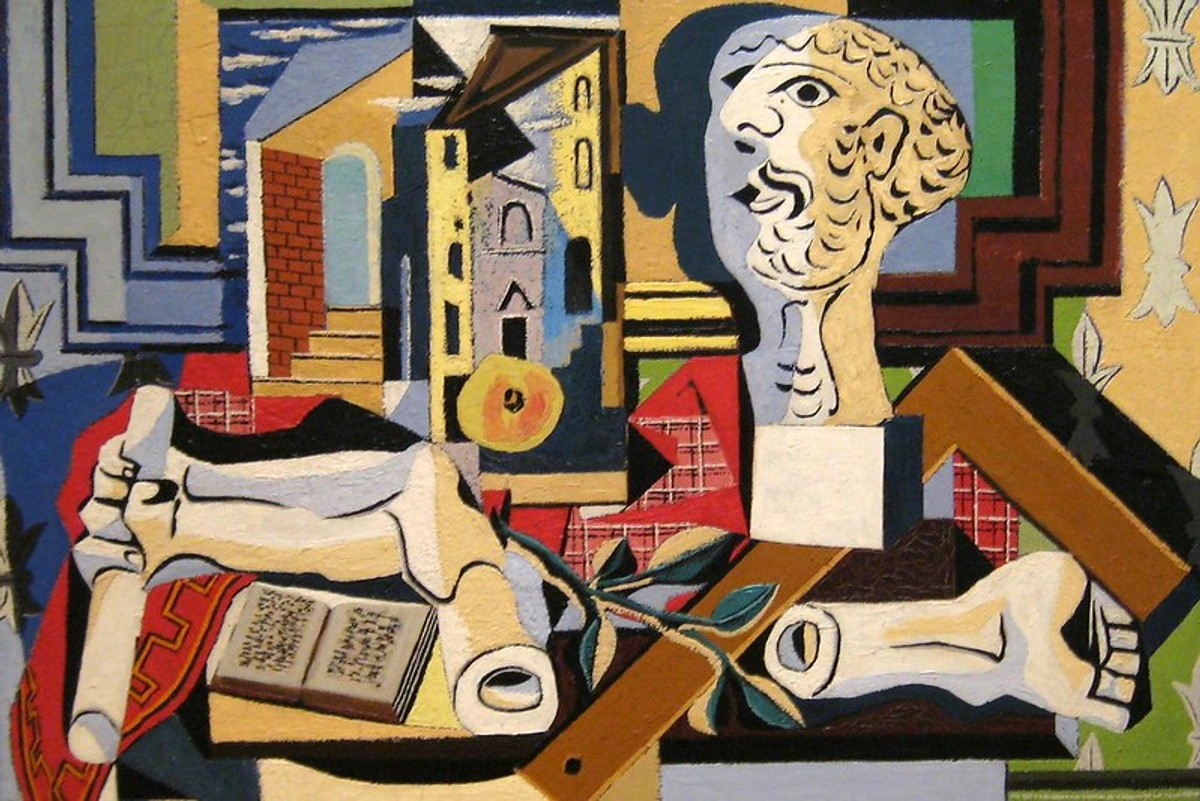

Renaissance Sculpture: A Curator's Timeless Dialogue with Abstract Art

Join a curator's personal journey through Renaissance sculpture – its humanism, innovative techniques, and master creators – discovering how these timeless principles unexpectedly resonate in contemporary abstract art and the artist's own studio.

A Curator's Timeless Dialogue: Renaissance Sculpture and its Echoes in Modern Art

To stand before a Renaissance sculpture, for me, is more than just appreciating art; it's a silent conversation across centuries. It’s a dialogue, often a deeply personal one, between the artist's hands and my own observing eye, a whispered secret about the human condition, the relentless pursuit of beauty, and that almost audacious quest for perfection. This "perfection" in Renaissance art wasn't just about flawless execution; it was about idealizing humanity, finding divine order and harmony in human form—a profound ambition deeply rooted in the era's burgeoning humanism and a re-evaluation of humanity's place in the cosmos. In contrast, much of modern and contemporary art often embraces imperfection, chaos, or subjective experience as its own form of truth, yet the underlying human drive to express remains a constant.

The whispered secret? It's about our shared vulnerabilities, our capacity for grace, the quiet dignity of suffering, and the explosive joy of creation, all meticulously rendered to capture a universal emotional truth. As a curator and artist, I often find myself wondering how these historical works, seemingly distant in time, still spark a dialogue with the vibrant, complex spirit of contemporary art. In this exploration, we'll embark on a journey through the foundational principles of Renaissance sculpture, meet the masters who shaped it, understand the craft that brought it to life, explore the forces that drove its creation, and ultimately, discover how its enduring spirit continues to resonate in my own abstract practice today.

Think about it: the meticulous detail, the raw emotional depth, the sheer audacity of carving life from stone. It’s a pursuit that, in its very essence, mirrors my own journey as an artist – whether it's (hypothetically) chiseling marble or layering paint on canvas in my modern studio. There’s a relentless dedication to form and feeling, a timeless pursuit that, I believe, defines true artistry. Sometimes, I muse about the quiet, almost defiant ambition held by sculptors like Michelangelo, not unlike the burning drive I find in contemporary artists today. There’s a shared language of expression, a universal ache to create, that genuinely transcends eras.

The Renaissance: A Rebirth of Form and Spirit That Still Grips My Imagination

Reflecting on the vibrant energy of my city, Den Bosch, and the ceaseless drive of creativity, I’m drawn back to the very foundations of an artistic revolution. The Renaissance, that explosive period of cultural, artistic, and intellectual rebirth (roughly 14th to 17th century), saw sculpture quite literally emerge from the symbolic shadow of the Middle Ages. It wasn't just a timid revival of classical forms; it was a brazen reinterpretation, infused with a distinctly human spirit and a psychological depth that, honestly, still gives me goosebumps. For me, the shift is palpable, almost like a sigh of relief after centuries of artistic restraint, and for the public, it meant seeing themselves, their emotions, and their stories reflected in art with an unprecedented intimacy. Indeed, it was as if art finally looked back at humanity, acknowledging its worth, particularly in flourishing centers like Florence, the undisputed cradle of the Renaissance, where families like the Medici fueled an artistic explosion. Rome, with its ancient ruins and papal patronage, became a hub for monumental works, while Venice fostered a slightly different, more color-focused approach that still valued sculptural presence.

Before the Renaissance's bold reawakening, medieval sculpture, while possessing its own profound spiritual beauty and didactic purpose, often prioritized symbolic representation over anatomical realism. Figures were typically elongated, frontal, and less concerned with dynamic movement or individual psychological depth. Materials like wood, ivory, and often polychromed stone were used, but the focus was less on exploiting the inherent properties of the material for naturalistic effect and more on conveying theological narratives. The Renaissance, by contrast, looked back to classical antiquity, not just for forms, but for an entirely new philosophy: humanism, which put human experience and potential at the center. This philosophical shift was deeply influenced by the rediscovery of ancient Greek and Roman texts, including Neoplatonic ideas that sought to reconcile classical thought with Christian theology, viewing the human form as a reflection of divine perfection.

This profound fascination with the human form wasn't merely aesthetic; it was deeply intertwined with the era's burgeoning scientific inquiry and empirical observation. Artists, driven by a desire for accuracy and a belief in the human body as a reflection of divine order, studied human dissection—a radical act for its time. They devoured newly rediscovered texts on anatomy and proportion, drawing inspiration from classical ideals like the concept of the "ideal form," rooted in Platonic philosophy, which sought to represent the most perfect and harmonious manifestation of humanity. The advent of the printing press greatly aided in the dissemination of these anatomical studies and classical treatises, accelerating artistic innovation. This scientific understanding directly informed their aesthetic choices, allowing for anatomical precision and dynamic poses previously unseen. It was as if they were saying: if God made man in his own image, then the study of man's physical form was a pathway to understanding the divine itself.

They masterfully employed perspective and foreshortening to create astonishing depth and realism, making marble and bronze seem to occupy real, three-dimensional space with breathtaking conviction. It was, in many ways, the ultimate celebration of humanity's potential, a concept that continues to inspire artists and thinkers to this very day. Imagine the sheer audacity of it all – presenting humanity as a subject worthy of such detailed, glorious study! I can't help but feel a deep kinship with that aspiration, a burning desire to capture something universal through my own personal, often messy, lens. How did this radical shift in focus transform art forever? It also transformed the public's relationship with art, making it more accessible and relatable, moving from purely allegorical to profoundly human. This period undeniably laid the groundwork for a new era in art history.

Core Principles That Defined Renaissance Sculpture

When I look at these pieces, certain traits jump out at me, almost like a mental checklist of what made this era so revolutionary. They were not just technical innovations, but a philosophical reimagining of art's purpose, reflecting humanity's newfound confidence, often achieved through the careful choice and manipulation of materials like the finest Carrara marble or the versatile bronze.

Principle | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Humanism | At its heart, Renaissance sculpture embraced humanism, shifting focus from the divine to the human. There’s this profound, almost reverent, focus on human values and concerns. It's a celebration of our capabilities and achievements, often depicting figures in their ideal physical form. It’s like they were saying, “Look at us! Aren't we magnificent?” a notion I sometimes secretly whisper to my own finished canvases. It truly was a revolution of human pride, seeing man as the measure of all things. | |

| Realism and Naturalism | A huge departure from the more stylized medieval forms. These sculptors had a keen eye for anatomical correctness, for capturing movement, and for expressions so lifelike, you almost expect them to speak. Working primarily with marble and bronze, but also materials like terracotta and wood, they pushed the boundaries of what was possible, creating textures and details that brought their figures to vivid life. It takes a certain kind of stubborn dedication to achieve that – a dedication I understand when I’m trying to get a specific curve just right in an abstract line. | |

| Classical Influence | They were absolutely obsessed with ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, and it shows. You see it in the poses, the elegant drapery, and the mythological subjects. Sculptors meticulously studied surviving classical fragments, drawing inspiration from iconic works like the Laocoön Group (for its intense emotional drama and dynamic composition), the Belvedere Torso (for its powerful musculature and implied movement), the Apollo Belvedere (for its idealized masculine beauty and graceful pose), or the Venus de' Medici (for its elegant, sensual form and delicate contrapposto). These became touchstones for understanding ideal human proportion, order, balance, and dynamic tension. They weren't just copying, though; they were learning, absorbing, and then making it their own. Imagine stumbling upon a forgotten masterpiece and letting it completely redefine your artistic worldview – that’s what happened. | |

| Contrapposto | This one's a game-changer. It's that dynamic, natural pose where a figure's weight shifts to one leg, causing the hips and shoulders to tilt in opposite directions. It creates this wonderful sense of relaxed, yet engaged, movement, as if a figure has momentarily paused mid-action or is simply shifting their weight in contemplation. For me, it's about finding that delicate balance in an otherwise chaotic composition, a visual counterpoint that creates dynamic harmony, a hint of life and potential motion in stillness. | |

| Emotional Depth | Sculptors weren't content with just pretty faces; they sought to convey complex psychological states. Their figures aren't just stoic; they're grieving, defiant, contemplative. Consider the subtle tension in Michelangelo's David's brow, hinting at the intense psychological anticipation before battle, or the overwhelming sorrow palpable in Mary's resigned slump in the Pietà. It makes them relatable, even across half a millennium, and challenges me to find equally profound, albeit abstract, expressions of emotion in my own work – perhaps through the dynamic interplay of color and form to evoke a feeling of longing or triumph, without ever resorting to literal representation. | n |

| These principles coalesced to create an art form that was both intellectually rigorous and deeply moving, fundamentally reshaping how humanity perceived itself and its place in the world. |

The Craft: From Raw Stone to Immortal Form

Have you ever considered the sheer physical grit involved in turning a raw material into a masterpiece? Underpinning the emotion and form of Renaissance sculpture was the fundamental mastery of the material. The choice of marble, bronze, terracotta, or even wood was not trivial; it dictated the scale, the detail, and the very endurance of the artwork. I sometimes stand in my studio, staring at a blank canvas, and think of the sheer physical and mental fortitude it must have taken to approach a block of raw marble. The initial strike, the careful chiseling, the endless hours of sanding and polishing – it was an act of profound dedication, almost a battle between will and stone. And before that first chisel hit, there were countless preparatory drawings and clay models, where the artist meticulously worked out the pose, composition, and emotional nuance, a process not unlike my own extensive sketching before a complex mixed-media piece.

Beyond the familiar marble and bronze, Renaissance sculptors also utilized a range of other materials. Terracotta, a versatile and malleable clay, was often used for smaller, more intimate works, portrait busts, or crucial preparatory studies because it allowed for spontaneous modeling and expressive detail before committing to more costly materials. It was also frequently polychromed (painted in vibrant colors), a practice that carried over from medieval sculpture, which often used bright, symbolic hues. While Renaissance sculpture generally moved towards appreciating the natural color of stone or the patination of bronze, polychromy was still employed, especially for wooden figures or stucco reliefs, to enhance their lifelike quality. Stucco, a plaster-based medium, offered similar flexibility and was frequently used for intricate relief work, decorative elements, or even large-scale figures that mimicked more expensive stone. Wood, though less durable, was carved for religious figures, choir stalls, or crucifixes, often painted to enhance their lifelike quality. Each material presented its unique challenges and possibilities, allowing for diverse forms of expression.

Bronze casting, too, was a monumental undertaking, requiring mastery of metallurgy, mold-making, and the dramatic, fiery pour. The risks involved were immense: a single misstep in the temperature, mixture, or mold could lead to catastrophic failure, wasting months of work and precious materials. For large-scale bronze works, the engineering challenges were significant, involving complex armatures for internal support and careful management of the cooling process to prevent cracking. The lost-wax technique, a complex multi-step process involving intricate molds and a precise understanding of material properties, was revolutionary because it allowed for incredibly detailed and dynamic compositions that would be impossible to carve from a single block of stone. This advancement in casting techniques enabled sculptors to create hollow, lighter, and more complex figures with outstretched limbs or flying drapery that defied the limitations of solid marble. It's a reminder that art isn't always quiet contemplation; sometimes, it's a monumental, industrial process. When I consider the complexity of Renaissance workshops and the sheer dedication required, it makes my own occasional struggles with a difficult brushstroke seem, well, a little less dramatic. Just last week, I nearly threw a canvas across the room because a particular shade of blue just wouldn't behave, insisting on muddying itself – a minor skirmish compared to a miscast bronze, I suppose! But the principle is the same: pushing against the limits of the material to bring a vision to life, whether it's marble, bronze, or the diverse acrylics and mixed media I use in my abstract art today. Do you ever feel that intense push-and-pull with your own creative medium? This profound understanding and manipulation of materials are central to the history of sculpture.

The Driving Forces: Patrons, Workshops, and the Public Eye

But how did such monumental works come to be, and how were they brought to the public? Many works were destined for prominent public display in churches, civic squares, or grand palaces, ensuring wide accessibility and contributing to civic pride and collective identity. The public's enthusiastic reception of these innovative works further fueled the artistic boom, creating a vibrant demand for art that transcended purely religious or aristocratic circles. Beyond mere appreciation, the public often engaged with these works in public debates and critiques, interpreting their civic, religious, and political meanings, thereby actively participating in the cultural discourse. But how were these colossal undertakings funded and executed?

Behind every colossal marble David or tender Pietà stood a patron, but also an entire ecosystem of economic and social structures that fostered artistic creation. These were often powerful families like the Medici, influential popes, or even civic guilds commissioning public works, whose immense wealth and, let's be honest, sometimes formidable egos, fueled the artistic engine of the Renaissance. Their commissions weren't just transactions; they were statements of power, piety, and prestige, but also acts of intellectual curiosity and cultural investment, fostering artistic innovation for generations. The sheer scale of patronage from the newly prosperous merchant class and religious institutions created an unprecedented demand for art, elevating artists to new social standing. Sculptors, previously seen as mere craftsmen, began to gain considerable social status, often working closely with powerful figures and even influencing cultural discourse.

Take the Medici family, for instance: their extensive patronage of artists like Michelangelo, particularly early in his career, not only provided him with financial stability and access to materials but also allowed him the creative freedom to tackle monumental projects that would define the High Renaissance. This symbiotic relationship between artist and patron became a crucial engine of artistic output and innovation throughout the era. What a complex dance of power, money, and vision, right?

Renaissance workshops were not merely individual studios; they were bustling hubs of collaborative learning and production, often run by a master artist who would guide apprentices through every stage of the process, from preparing materials to executing complex commissions. These workshops operated much like modern-day creative agencies, often organized under powerful guilds – such as the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname (Guild of Stone and Wood Masters) in Florence, or the Arte della Seta (Silk Guild) for bronze founders – that regulated quality, training, and commercial practices. This systematic approach, from initial preparatory drawings and clay models for working out poses and compositions to the final execution, ensured consistency and quality across major projects. It reminds me of the structured (yet chaotic) thought processes behind my own larger mixed-media pieces, where initial sketches and small studies are vital before the final canvas, a process of refinement and collaboration, even if that collaboration is mostly with my own internal critic!

As an artist in today's world, the dynamic of patronage, of a shared vision (or sometimes, a clashing one!), is something I find endlessly fascinating – how much of a piece belongs to the artist, and how much to the one who paid for its existence? While less common now, this relationship still echoes in commissions for public art or private collections, reminding us that art never exists in a vacuum. It always has a story, and often, an unexpected origin. The notion of a shared legacy, where art transcends the individual creators and owners to become part of a larger cultural narrative, is quite profound, much like the ongoing journey of my own timeline as an artist. This intricate dance of funding, creation, and public reception propelled Renaissance sculpture to unprecedented heights.

Master Innovators and Their Immortal Creations

From the sheer physical effort and technical mastery of the craft, we now turn our gaze to the giants who wielded these techniques to create legacies. While countless hands contributed to this golden age, a few names stand as colossal figures, their works continuing to awe and inspire me. I often ponder the sheer audacity of these artists, polymaths in their own right, working with tools and materials that demanded immense physical and intellectual prowess. It’s a testament to the enduring power of human creativity, a deep drive to understand and represent the human condition that many contemporary artists still embark on, albeit with different mediums. The challenges might change, but the core drive remains – much like how my own artistic journey, documented on my timeline, reflects a continuous evolution of approach, yet a consistent pursuit of expression.

Lorenzo Ghiberti (c. 1378–1455): The Gatekeeper of a New Era

Before the individual brilliance of Donatello, the groundwork for Renaissance sculpture was laid by pioneers like Lorenzo Ghiberti, whose monumental achievements heralded a new age of artistic ambition and technical prowess. His innovative mastery of low relief and linear perspective allowed him to create an illusion of incredible depth on a shallow surface, a pivotal technical advancement that influenced generations.

- The Gates of Paradise (1425–1452): Ghiberti’s gilded bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery are, quite simply, revolutionary. Michelangelo himself supposedly declared them 'The Gates of Paradise.' These ten panels, depicting Old Testament scenes, mastered linear perspective and foreshortening to create astonishing illusionistic depth within the low relief. Figures recede convincingly into space, and the emotional narratives are conveyed with a fluidity and grace previously unseen. For me, they represent a monumental commitment to storytelling through form, where every detail serves the larger narrative – much like the carefully orchestrated layers in a complex abstract composition aim to tell an emotional story without literal imagery. The delicate integration of figures into their landscape also subtly conveys a sense of divine order and harmony.

Donatello (c. 1386–1466): The Pioneer, The Rebel

Donatello, in my opinion, was the true harbinger of Renaissance sculpture, pushing boundaries with an innovative spirit that was almost punk rock for its time. His bold use of schiacciato (flattened relief) to create atmospheric perspective, and his pioneering freestanding figures, were a decisive break from the Gothic tradition, ushering in a new, more expressive realism. He made sculpture feel human again.

- David (c. 1440s): This bronze masterpiece is revolutionary. It's the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity, depicting a youthful David after his victory over Goliath. The contrapposto is subtle, the gaze confident yet serene, almost a little cocky, and Goliath's head rests symbolically under his foot. It speaks to a certain vulnerability and strength that many artists, including those working in post-impressionism or even Fauvism, would later explore through vastly different means, each trying to capture that complex human spirit. It's a truly iconic piece of youthful defiance.

- Gattamelata (c. 1453): A monumental equestrian statue of a Venetian condottiero (mercenary captain). It's a powerful statement of individual authority and heroism, reviving the classical equestrian portrait with unparalleled grandeur. The scale and presence are immense – a challenge for any artist to convey such gravitas, to make bronze breathe with power and purpose, giving the illusion of a living, breathing monument. The subtle symbolism of the commander's steady gaze and the horse's poised stance reinforce themes of leadership and unwavering resolve.

Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435–1488): The Teacher, The Refiner

Verrocchio, a generation after Donatello, was a crucial figure, bridging the early Renaissance with its High Renaissance peak. He ran a highly successful workshop, training luminaries like Leonardo da Vinci (an incredible interdisciplinary mind who excelled across art and science, mirroring the diverse interests I sometimes wrestle with myself!), and his work often blended the robust naturalism of Donatello with a refined elegance and a precise understanding of anatomy, which he rigorously taught.

- David (c. 1473–1475): Verrocchio’s bronze David offers a fascinating contrast to Donatello’s. His David is slender, elegant, and almost aristocratic, depicted with a swaggering confidence. Goliath's head rests at his feet, emphasizing the hero's victory and perhaps a youthful arrogance. It’s a wonderful example of how two great artists could approach the same subject with dramatically different interpretations – a reminder that even objective forms can hold subjective truths.

- Christ and St. Thomas (c. 1467–1483): Commissioned for Orsanmichele in Florence, this group is a masterclass in dynamic composition. St. Thomas reaches to touch Christ's wound, creating a sense of dramatic interaction and psychological tension. The way the figures occupy and interact with their niche, almost spilling out into the viewer's space, is something I always appreciate – it pulls you right into the narrative, much like a powerful abstract painting can draw you into its emotional landscape, inviting you to step into its world.

Michelangelo (1475–1564): The Divine One, The Tormented Soul

Michelangelo Buonarroti, a true polymath of the High Renaissance, famously considered himself primarily a sculptor, often lamenting the painting commissions – a sentiment I sometimes echo when I find myself bogged down in administrative tasks instead of being lost in the flow of creation! His ability to coax profound emotion and monumental form from marble is legendary. His works are not merely statues; they are raw expressions of the human spirit, often reflecting an intense inner turmoil or divine grace. He saw the figure already within the stone, and it was his job to set it free, a concept I deeply resonate with when I feel a painting 'emerging' from the canvas rather than being merely applied. His unique approach to carving, often described as working per forza (by force) or a levare (by taking away), involved attacking the block directly, seeing the final form within.

- Pietà (1498–1499): Housed in St. Peter's Basilica, this work depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus. The drapery, the delicate facial expressions, the overwhelming sorrow, and the tender resignation are rendered with breathtaking sensitivity. The composition is a masterclass in balance and flow, often utilizing a triangular composition to create stability and guide the viewer's eye gently through the heartbreaking scene, echoing the classical principles of harmony. It's a poignant exploration of grief and love, a theme universal enough to resonate in any era, perhaps even inspiring some of the more contemplative contemporary pieces one might find for sale on my site, exploring similar profound human experiences through different lenses.

- David (1501–1504): Standing over 17 feet tall, Michelangelo’s David is an icon. Unlike Donatello’s youthful victor, Michelangelo’s David is poised before the battle, muscles tensed, eyes fixed on an unseen Goliath. It captures a moment of intense psychological anticipation and moral courage – not just physical prowess, but the internal struggle before action. It’s a profound reflection on human potential and decision, an incredible feat of both physical and emotional realism that leaves me speechless every time. It’s a piece that demands you consider the unseen narrative, and how even the negative space around the figure contributes to its overwhelming presence.

- Moses (c. 1513–1515): Part of the monumental, though ultimately unfinished, tomb for Pope Julius II, Moses is depicted with a powerful, commanding presence, his gaze stern, his body coiled with a barely contained energy. The iconic 'horns' he bears are, in fact, a widespread mistranslation of the original Hebrew word for "radiating" or "shining" (often depicted as rays of light) into cornuta ("horned") in the Latin Vulgate Bible. This fascinating linguistic nuance only adds to his formidable, almost otherworldly aura, influencing centuries of artistic representation and sparking countless art historical debates. It's a testament to Michelangelo's ability to imbue marble with dynamic tension and a palpable sense of inner life, making Moses seem ready to spring into action or deliver a thunderous pronouncement, forever captured in that moment of profound spiritual and earthly power.

| Artist | David Description