Beyond the Canvas: More Quirky & Surprising Art Facts from an Artist

Okay, let's be honest. Sometimes, when you walk into a museum or gallery, art can feel a bit... intimidating, right? Like there's a secret handshake you missed, or everyone else got a memo about what you're supposed to feel. I remember standing in front of a massive abstract painting once, feeling utterly lost, wondering if I was 'getting it' or just pretending. Art history, with its grand narratives and revered masterpieces, can seem like a distant, serious subject. But art, at its core, is just people making things. And people are weird, wonderful, and full of surprises. So is art! My goal here is to pull back that curtain a little, sharing some facts that make you go, "Huh, really?" and remind us that the art world is full of drama, innovation, and sometimes, pure absurdity. These aren't just dry historical notes; they're glimpses into the human stories, the struggles, the triumphs, and the sheer oddity that fuels creativity and shapes the art we see today. As an artist myself, these stories resonate deeply, sometimes mirroring my own journey, sometimes offering a wild contrast. We'll touch on everything from famous struggles and bizarre materials to notorious thefts and even the art you can't see. These are just a few examples; the world of art history is vast and full of human interest. Let's explore some of my favorites, and maybe a few you haven't heard before. Ever wondered if the Mona Lisa gets fan mail? Or if some colors were literally worth more than gold? Or perhaps if an artist ever tried to sell... nothing? Stick around.

Did Van Gogh Really Only Sell One Painting? (And Why Wasn't He an Instant Hit?)

So, Vincent van Gogh. We all know "The Starry Night." It's iconic, right? On posters, mugs, socks... everywhere. But during his lifetime? Not so much. His unique style, often categorized under Post-Impressionism, with its intense colors, visible brushstrokes, and emotional intensity, was a radical departure from the academic norms of the time. Academic art often favored smooth, invisible brushwork and idealized subjects, like historical or mythological scenes, a stark contrast to Van Gogh's raw, expressive approach focused on everyday life and landscapes. This subjective use of color and visible texture felt chaotic and unfinished to many contemporary viewers, challenging their very definition of what constituted a 'good' painting. He wasn't showing in the prestigious Salon system, the official art exhibition in Paris that dictated taste and success, or selling through major galleries like some of his contemporaries who adhered to more traditional styles. The Salon held immense power, acting as a gatekeeper for artistic careers and public perception. To be excluded or ignored by it was a significant hurdle. Critics often dismissed his work, finding his colors too jarring and his forms too distorted. Imagine creating something so universally loved centuries later, but struggling to make ends meet while you were actually doing it. It makes me think about my own journey as an artist, wondering if my work will ever truly connect with people on that level, or if the things I feel are radical now will just be... weird. It's a specific feeling, creating something that feels vital and necessary to you, but seeing it met with indifference or confusion.

It's often said he only sold one painting during his life, The Red Vineyard. While there's some debate among historians about whether he might have sold a few more drawings or received payment in kind, the fact remains: he wasn't exactly a commercial success story while he was alive. The Red Vineyard is often cited as the only painting sold for a monetary price during his lifetime because documented sales records for others are scarce or non-existent, making this single transaction a concrete, if lonely, data point in his commercial life. Talk about a delayed reaction! It makes you think about how we value things, doesn't it? And maybe gives a little perspective to any artist (like me!) wondering if anyone will ever 'get' their work. Interestingly, The Red Vineyard was reportedly sold in 1890, just months before Van Gogh's death, to Anna Boch, a fellow painter and collector, for 400 Belgian francs. This specific sale is often cited because it's one of the few documented instances of him selling a painting for a monetary price, making it a concrete, albeit small, commercial transaction in a life otherwise devoid of them.

His posthumous fame owes a huge debt to his sister-in-law, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, who inherited his work and dedicated her life to promoting it. But even before that, his brother Theo van Gogh was his constant support, both emotionally and financially, and the recipient of those famous letters that give us such insight into Vincent's mind. Theo's unwavering belief and practical assistance were absolutely crucial during Vincent's most prolific and challenging years. After Theo's untimely death shortly after Vincent's, Jo took on the monumental task. She meticulously organized exhibitions across Europe, published his extensive letters to his brother Theo (which offered invaluable insight into his mind and process and became a cornerstone of his legacy), and tirelessly championed his art to critics, collectors, and the public. Her business acumen and unwavering belief were crucial, not just for showing his work, but for actively shaping the narrative around his genius and ensuring his place in art history. Without her tireless efforts, his genius might have remained largely unknown, gathering dust in an attic. It's a powerful reminder that sometimes, the greatest art needs an advocate, a champion who believes in it even when the world doesn't yet. It makes me wonder who my 'Jo' will be!

https://www.rawpixel.com/image/3864631, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

(Image: Vincent van Gogh's 'Starry Night Over the Rhône', a different, though equally stunning, starry night scene than the more famous 'The Starry Night' discussed in the text.)

Speaking of universally recognized art that sparks unexpected connections...

Who Sends Mail to the Mona Lisa?

Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa" is arguably the most famous painting in the world. She's got that enigmatic smile, the mysterious background... and apparently, a fan club so dedicated they send her mail. Yes, the "Mona Lisa" at the Louvre Museum in Paris actually receives letters from admirers. People write to her, propose marriage, confess secrets, or even send job applications! It's said she receives hundreds of letters a year! The Louvre even has a dedicated staff member whose job it is to sort through this correspondence. I mean, imagine that job description! "Sorting love letters for a 500-year-old painting." The Louvre staff reportedly archives these letters, a testament to the painting's enduring cultural impact and the strange ways people connect with art. It's a testament to the deep, personal connection people can feel with a piece of art, even one so ancient and revered. Perhaps it's the power of her celebrity status, the psychological phenomenon of pareidolia that makes us see a living presence in her gaze, or simply the mystery of her identity, the mastery of Leonardo's technique, or the sheer weight of history and cultural projection placed upon her over centuries – whatever the reason, she clearly resonates with people on a level that transcends time and space. It also makes me wonder if she ever writes back. Probably just a cryptic smile emoji.

Adding another layer to her mystique and fame, the "Mona Lisa" was famously stolen in 1911 by an Italian handyman named Vincenzo Peruggia, who believed it belonged in Italy. The theft caused a sensation, making headlines worldwide and drawing even more attention to the painting. When it was recovered two years later, its global celebrity status was cemented. This event significantly contributed to the painting's mystique and enduring fame, adding another layer to her already considerable "celebrity status."

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pedrosz/41067351765, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/deed.en

From fan mail to cold hard cash... and the surprising value of color.

Some Colors Were Literally Worth Their Weight in Gold

Ever wonder how artists afforded those vibrant blues centuries ago? Think of the stunning blues in Renaissance works by masters like Titian or in Vermeer's luminous scenes. That was often thanks to Ultramarine, a pigment made from grinding up the semi-precious stone Lapis Lazuli. This stuff was imported from Afghanistan and was incredibly expensive, often more costly than gold. Artists or their patrons had to specifically budget for it. Using a lot of Ultramarine was a flex, a way to show off wealth and status. Imagine having to justify the cost of your blue paint to a client! "Yes, sir, this shade of blue requires importing crushed rocks from a war-torn region, hence the price." Historically, preparing pigments was a laborious process; imagine hours spent grinding minerals like lapis lazuli by hand in a mortar and pestle, or the smell of boiling animal hides for glue binders, a far cry from squeezing paint from a tube today. You can see the incredible depth and richness Ultramarine provides in paintings like Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring or the robes in many paintings by Fra Angelico. It wasn't just blue; it was precious blue.

Other historically expensive pigments included Tyrian Purple (derived from sea snails, used by royalty because its extreme rarity and difficult extraction made it prohibitively expensive for commoners) and Carmine (made from crushed cochineal insects). And let's not forget the truly bizarre: Mummy Brown, a pigment made from grinding up actual Egyptian mummies! It was popular in the 17th-19th centuries until artists realized... well, what it was made of, and presumably, the supply ran low or ethical concerns (finally) arose. Another unusual historical material was Sepia, a brown pigment derived from the ink sacs of cuttlefish. As an artist, I've definitely winced at the price of certain pigments, especially high-quality cadmiums or cobalts, but needing a second mortgage for a tube of blue, or using ground-up ancient remains? That's a whole other level! This history of costly and unusual pigments ties directly into how artists use color and the psychology of color. Color isn't just visual; it has history, cost, and emotional weight.

The later development of synthetic pigments in the 19th and 20th centuries, like Cobalt Blue or Cadmium Yellow, dramatically changed this. These synthetic alternatives weren't just cheaper; they offered greater chemical stability, lightfastness, and a wider range of consistent hues, enabling artists to experiment with color in ways previously impossible and making vibrant palettes accessible to everyone. This invention had a huge impact on the democratization of color, making vibrant palettes accessible to artists of all economic levels, not just the wealthy or those with rich patrons. Imagine the freedom that must have felt like! It makes my modern tubes of acrylic paint feel incredibly mundane, though I'm eternally grateful for the accessibility. Thinking about modern pigments, even today some are incredibly expensive or ethically complex, like certain rare earth pigments or those derived from endangered sources, though thankfully none involve mummies anymore. It's a reminder that the cost and source of materials are still part of the artistic equation.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/artist-brush-mix-color-oil-painting-8382705/, https://creativecommons.org/public-domain/cc0/

From the enduring value of color to the fleeting nature of movements...

The Shortest Art Movement? Maybe the 'Brilliant Flash' Movement

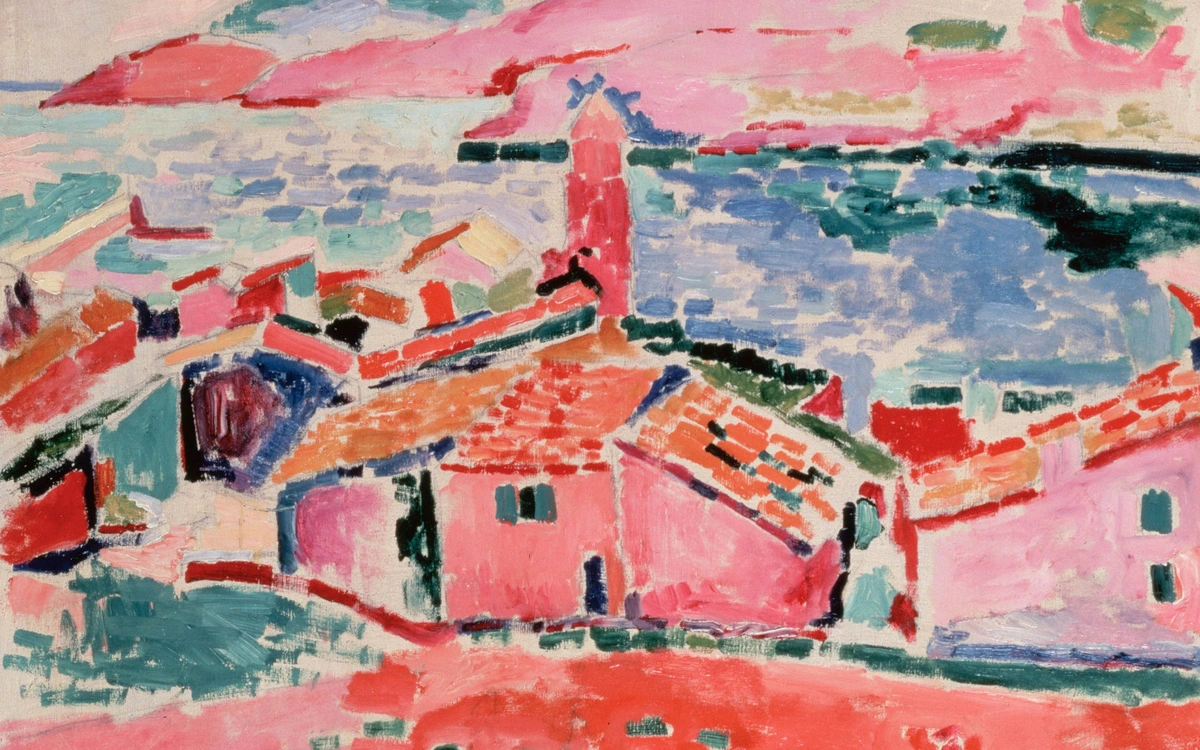

Okay, I might have made that name up, but there have been incredibly short-lived art movements or intense periods of collaboration. Take Les Fauves, for example. Their reign of vibrant, non-naturalistic color and bold brushstrokes, led by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, lasted intensely for only a couple of years around 1905-1907. While their influence lingered and spread, the core, unified movement with its shared exhibitions and manifestos was fleeting. Why was it so radical and short-lived? Fauvism directly challenged the more subdued palettes and descriptive brushwork of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism that preceded it. Their use of pure, unmixed color straight from the tube, applied in broad, expressive strokes, was shocking to many viewers accustomed to more traditional representation or even the nuanced color mixing of the Impressionists. The intensity of their shared exploration burned brightly but quickly.

Or think of the explosive, brief period of the Dada cabaret Voltaire in Zurich (1916), a hub of radical performance and ideas that burned brightly but briefly, giving birth to the wider Dada movement. Other movements like Vorticism (roughly 1914-1915), a British movement influenced by Cubism and Futurism, or certain intense, focused phases of Futurism also had very intense, short lifespans as unified groups. Why so short? Often, these intense, experimental movements are driven by a small group of artists pushing boundaries together, fueled by a specific reaction to the current art world or societal events. The presence of shared manifestos and clearly defined goals often characterized these intense, short-lived movements, providing a focused burst of collective energy that contrasts with longer, more diffuse cultural eras like the Renaissance. Once those initial ideas are explored, or artists develop their own distinct paths, the collective energy disperses. Compared to something like the Renaissance or even Impressionism, which spanned decades, Fauvism was a brilliant, explosive flash in the pan. It makes you think about how some ideas burn brightly and quickly, leaving a lasting impact despite their brevity. As an artist, I sometimes feel like my own style goes through these intense, short-lived phases before evolving again. It's a reminder that not everything needs to last forever to be significant. Thinking about truly micro movements, you could even look at specific, intense collaborations between just a few artists for a single project or exhibition – sometimes those burn out even faster, leaving behind just a handful of works but sparking ideas that ripple outwards. It's like a creative supernova.

https://www.goodfon.com/painting/wallpaper-henri-matisse-anri-matiss-vid-kolliur-kartina-fovizm.html, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

From fleeting movements to permanent disappearances...

The Case of the Missing Masterpieces: The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Heist

Art isn't just about creation; sometimes, it's about disappearance. One of the most famous unsolved art crimes happened in 1990 at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Thieves disguised as police officers stole 13 works, including priceless Old Masters and Renaissance pieces. The stolen items included:

- Rembrandt's The Storm on the Sea of Galilee (his only seascape)

- Vermeer's The Concert (one of only 35 known Vermeers)

- Govaert Flinck's Landscape with an Obelisk

- Five drawings by Edgar Degas

- Édouard Manet's Chez Tortoni

- A Chinese bronze beaker

- A French imperial eagle finial

The total value was estimated at $500 million, and the museum still offers a substantial $10 million reward for information leading to the recovery of the stolen items. The frames are still hanging empty in the museum today, a haunting reminder of the loss and a deliberate choice by the museum to mark the absence. It feels like something out of a movie, doesn't it? This wasn't just property theft; it was the theft of cultural heritage, leaving a void that still aches.

The case remains unsolved, despite ongoing FBI investigations. The FBI's main theory is that the theft was carried out by individuals associated with organized crime, though this has never been definitively proven. It highlights the dark side of the art market and the difficulty of selling such high-profile stolen works – they are often too hot to handle, disappearing into private collections or remaining hidden. This is where the concept of provenance becomes crucial – the documented history of ownership of an artwork. Stolen art lacks legitimate provenance, making it virtually impossible to sell openly on the legal market. The enduring mystery, the empty frames, the sheer audacity of the crime... it all adds up to a story that captures the imagination but also underscores the vulnerability of beauty and how much value, both monetary and emotional, we place on these objects. The empty frames are a stark, silent scream in the halls, a constant question mark. It makes me think about the 'holes' in my own creative process sometimes, the ideas that get stolen away by distraction or doubt, the blank spaces where something beautiful should be but just... isn't.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/paintings-on-wall-in-museum-19036603/, https://creativecommons.org/public-domain/cc0/

Speaking of challenging expectations... and materials.

Art Made From... Unexpected Materials

Artists are constantly pushing boundaries, and sometimes that means using materials you'd never expect. Think beyond paint and clay. Tracey Emin's controversial installation "My Bed" (1998) featured her unmade bed, surrounded by detritus like empty vodka bottles, cigarette butts, and stained sheets. It was deeply personal, raw, and definitely not traditional. Or consider Chris Ofili, who famously used elephant dung in his paintings, sometimes as a support for the canvas or incorporated directly into the paint, often decorating the dung balls with pins. These choices aren't just for shock value; they often carry symbolic meaning, challenging our perceptions of what art can be and what materials are 'worthy'.

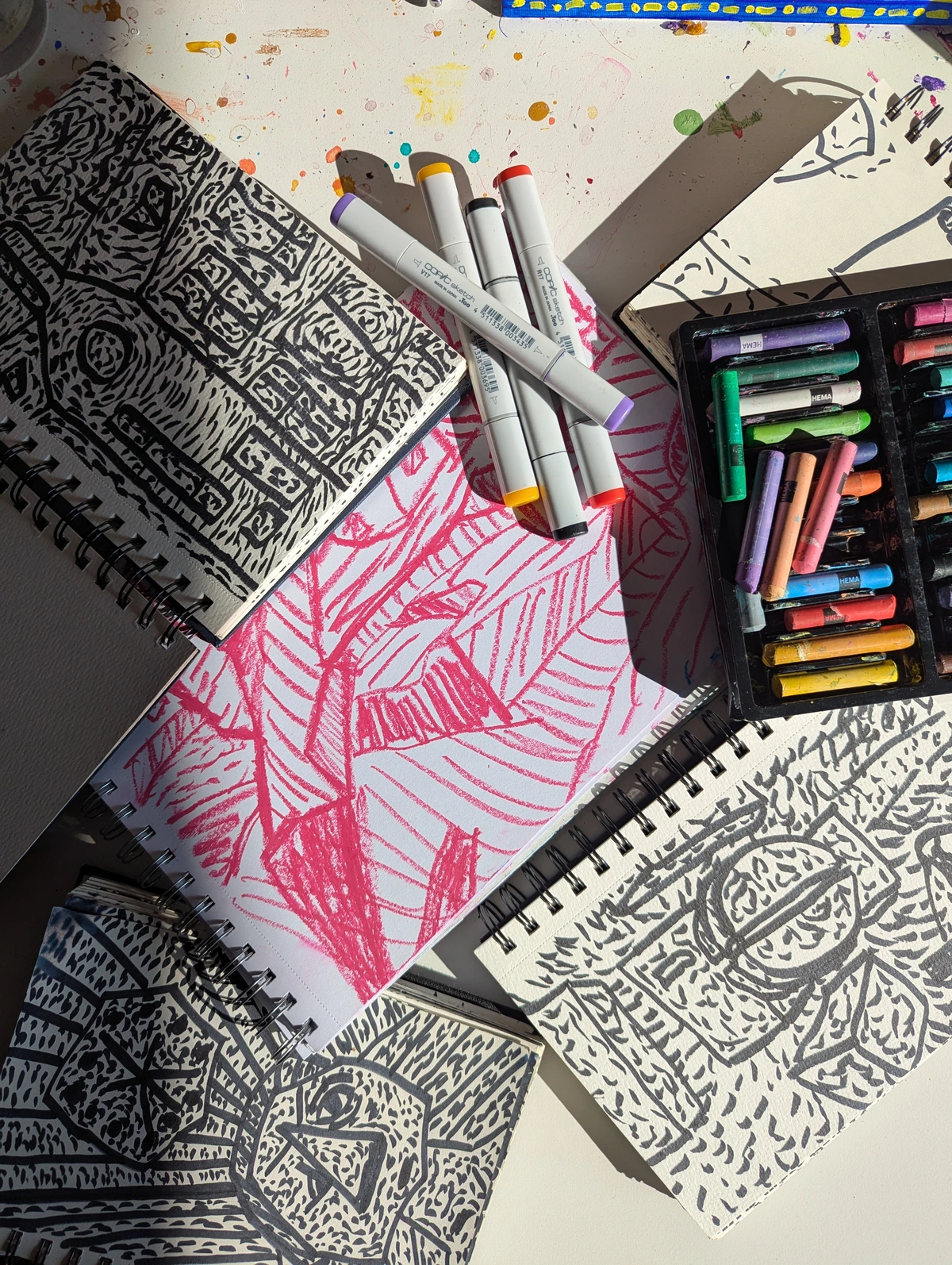

Even historically, artists used materials that might seem strange today, like egg tempera (using egg yolk as a binder, common in medieval and early Renaissance painting) or animal glues for preparing surfaces. Some historical pigments involved urine (used in preparing indigo dye) or even ground insects (Carmine). And yes, Mummy Brown pigment was literally made from ground-up mummies. More recently, we see artists incorporating textile art in unexpected ways, using recycled materials, natural elements like dirt or leaves, or even light, sound, or biological matter (BioArt). Artists also frequently use found objects and everyday items, transforming them through techniques like assemblage into something new and thought-provoking. Think of artists using human hair, blood, or even food items that decay over time, forcing viewers to confront themes of mortality or consumption. Contemporary artists continue to surprise; for instance, artist Dustin Yellin creates intricate collages embedded within layers of resin, sometimes incorporating found objects and even biological specimens, or artists who create ephemeral sculptures purely from light projections or accumulated dust. We also see artists working with purely digital materials, creating art from code, data, or even algorithms, pushing the boundaries beyond the physical object entirely. The choice of material can be as much a part of the message as the image itself. As an artist, I'm always experimenting, trying new textures or mediums, pushing my own comfort zone, but I haven't quite gotten to elephant dung yet... maybe someday? It's fascinating how artists find ways to make the mundane or the bizarre speak volumes, reminding me that creativity isn't limited by what's in the art supply store.

https://freerangestock.com/photos/177284/artists-workspace-filled-with-paint-brushes-and-supplies.html, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

From the bizarre to the utterly practical... a small invention that changed everything.

The Humble Paint Tube: A Revolution in a Cap

Here's a fact that might seem mundane but had a massive impact: the invention of the collapsible metal paint tube. Before the mid-19th century, artists had to store paint in pig bladders or glass syringes, which was messy, wasteful, and made painting outside incredibly difficult. Imagine trying to capture a fleeting sunset en plein air while wrestling with a pig bladder! Other practical innovations like the portable easel and pre-primed canvases also began to appear around the same time, freeing artists from the confines of their studios and making outdoor work truly feasible.

American painter John Goffe Rand patented the metal tube in 1841, and it quickly became the standard. This simple invention, combined with the other portable tools, revolutionized landscape painting and made spontaneous work much easier. It also meant pigments could be manufactured and packaged with greater consistency and quality control than when artists had to grind and mix them by hand, leading to more reliable and vibrant colors. It directly contributed to the rise of Impressionism, the Barbizon School, and other movements that embraced painting outdoors and capturing the changing effects of light and atmosphere. It's a reminder that sometimes, the biggest artistic leaps come from the most practical innovations. As someone who loves painting outside, I am eternally grateful for this little metal tube. It's the unsung hero of modern painting! It makes me think about how much we take simple tools for granted in our own creative processes.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Painter_David_Brewster_creating_work_for_the_Art_of_Action_project.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0

When is creating art... about destroying it?

When is Destroying Art... Art?

Art isn't always about creating something new; sometimes, it's about interacting with what already exists, even if that means destruction or alteration. One famous example is Robert Rauschenberg's Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953). Rauschenberg admired Willem de Kooning and asked him for a drawing to erase. De Kooning, after some hesitation, gave him a drawing that he knew would be difficult to erase, filled with dense marks. Rauschenberg spent weeks doing it, and the final piece is the framed, nearly blank paper with the title and Rauschenberg's explanation. It's a controversial piece that challenges ideas of authorship, value, and the very definition of art. It also sparked debates about conservation – how do you 'conserve' a work whose essence is its erasure? How do you preserve something whose core identity is its own disappearance? This adds a fascinating layer of philosophical complexity, raising questions about the "conservation of conceptual art" itself. How do you preserve the idea or the act when the physical object is meant to be altered or destroyed?

Other artists have explored destruction or alteration too, like Gustav Metzger's auto-destructive art (art that destroys itself) or Banksy's self-shredding painting Love is in the Bin (formerly Girl with Balloon) which partially shredded itself after being sold at auction. Ai Weiwei famously dropped and smashed a Han Dynasty vase in his 1995 work Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, an act of destruction intended to critique cultural values and history. It makes you question: What is the 'art' here? The original drawing? The act of erasing? The concept? The resulting object? It's definitely quirky, and it forces you to think differently about creativity and destruction.

This idea of non-permanence is also central to performance art, where the artwork exists only in the moment of its execution. Artists like Marina Abramović or Tino Sehgal create experiences that cannot be bought or sold as physical objects in the traditional sense; the 'art' is the live interaction or event itself, which then only exists in memory, documentation, or retelling. Ephemeral installations, like Christo and Jeanne-Claude's wrapped buildings or land art that changes with the weather, also challenge the idea of art as a permanent, sellable object. It's a reminder that art can be a question, not just an object, and sometimes that question is about its own existence or disappearance. It makes me wonder about the fleeting nature of my own creative impulses – are they art even if they don't result in a finished piece? This whole concept really pushes the boundaries of defining art as a physical, sellable object, doesn't it?

https://www.flickr.com/photos/abstract-art-fons/30634352376, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Speaking of things that disappear... sometimes not by the artist's hand.

The Most Stolen Masterpiece?

If the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist sounds dramatic, imagine a single artwork with a rap sheet longer than some criminals! The Ghent Altarpiece, formally known as The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, is a massive and complex 15th-century [polyptych] (a multi-paneled painting) by Hubert and Jan van Eyck housed in St. Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium. This incredible work, featuring detailed panels depicting biblical scenes and figures, holds the dubious distinction of being, arguably, the most stolen artwork in history. It's been stolen, hidden, or seized a staggering seven times throughout its existence, surviving everything from Calvinist iconoclasts (who sought to destroy religious images) and Napoleonic looters to World War I German forces and Nazi theft during World War II. Its immense artistic mastery, religious significance, and sheer scale made it a prime target throughout history.

One panel, The Just Judges, is still missing since 1934 after being stolen and held for ransom; its whereabouts remain one of the art world's great mysteries. It's a painting that seems to attract trouble, a silent witness to centuries of conflict and desire. It makes you wonder what kind of energy or fate clings to objects of such immense historical and artistic value. Does the art itself have a will to survive, or is it just a magnet for human greed and conflict? As an artist, the idea of my work being so desired it's repeatedly stolen is... well, it's a strange thought. Flattering, I guess? But mostly terrifying.

https://freerangestock.com/photos/127949/baroque-dome-.html, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

From objects that are stolen to art that isn't even there...

Selling the Invisible?

What if the art isn't even there? This might sound like a punchline, but it's a real concept explored in the art world, particularly within Conceptual Art. One of the most famous examples is Yves Klein's work in the late 1950s. He held exhibitions where the gallery was completely empty, presenting "zones of immaterial pictorial sensibility" – essentially, selling the idea or the experience of art, not a physical object. Buyers would pay in gold, and Klein would sometimes throw half the gold into the Seine River as a gesture of immateriality. As proof of purchase for these invisible works, buyers would often receive a receipt or certificate, sometimes with the understanding that destroying the receipt would make the ownership of the immaterial zone more complete. In a way, the certificate was the artwork. It's wild! Can you imagine explaining that purchase to your insurance company?

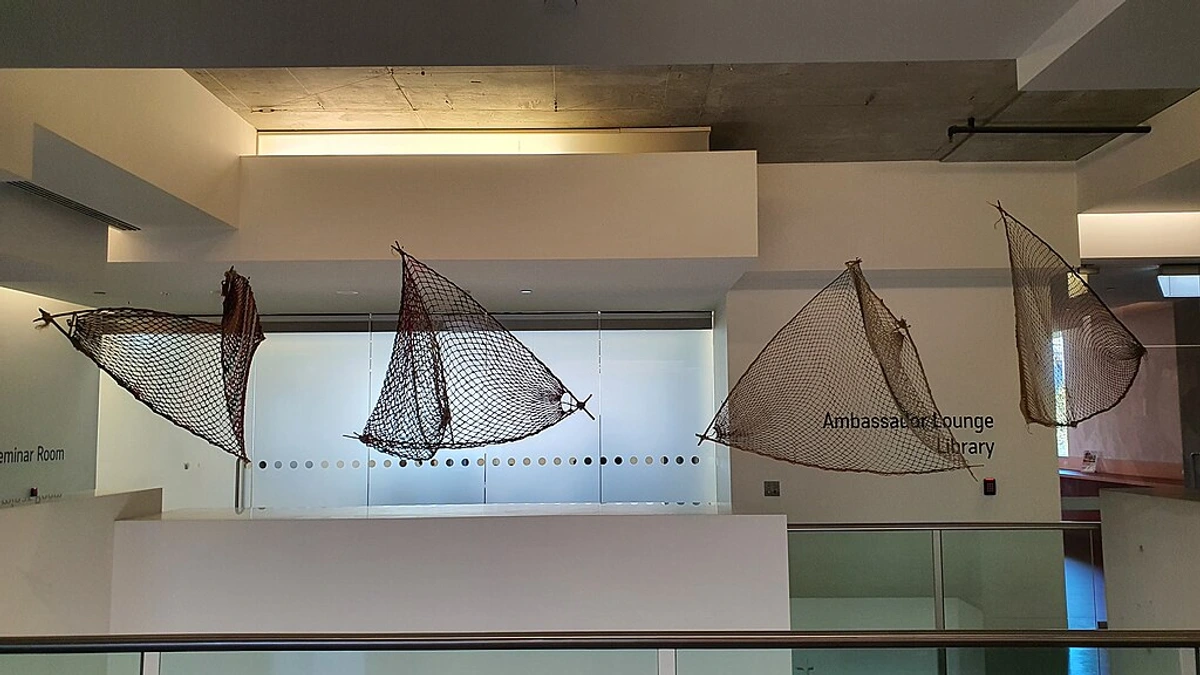

As mentioned earlier with performance art, artists like Marina Abramović or Tino Sehgal create works that exist only in the moment of their performance or interaction, leaving behind no physical artifact to collect or display in a traditional sense. Ephemeral installations, like Christo and Jeanne-Claude's wrapped buildings or land art that changes with the weather, also challenge the idea of art as a permanent, sellable object. This explicitly connects their work back to the core idea of challenging the definition of art as a physical, sellable object, reinforcing the conceptual shift initiated by artists like Duchamp and Klein. It forces us to question our assumptions about what art is and what it means to own it. Can you really own an experience or an idea? As someone who makes physical objects, the idea of selling something invisible is both baffling and strangely liberating. It pushes the boundaries of what we define as 'art', making me wonder if the 'art' of my work is the paint on the canvas, or the feeling it evokes, or the idea behind it. Maybe it's all a bit invisible in the end.

https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hanging_objects_in_the_second_floor_of_Museum_of_Contemporary_Art_%282%29.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

Speaking of challenging definitions... what about a urinal?

The Readymade Revolution: Is a Urinal Art?

Let's talk about Marcel Duchamp and the readymade. In 1917, Duchamp submitted a porcelain urinal, signed "R. Mutt," to an exhibition organized by the Society of Independent Artists, of which he was a board member. He titled it "Fountain." The art world was, understandably, scandalized, and the work was famously rejected by the exhibition committee despite the show's non-juried policy. Was this art? Duchamp argued that by selecting the object and presenting it as art, the artist conferred upon it a new meaning, shifting its context from a functional object to an object of contemplation. It wasn't about the skill of creation, but the idea behind the selection and presentation. This simple act had a seismic impact, fundamentally shifting the focus from manual skill and aesthetics to conceptual idea and challenging the very notion of what constitutes art and authorship. It paved the way for Conceptual Art and forever changed the conversation about what art could be. It's a fact that still sparks debate today and makes me chuckle a little. The sheer audacity of it! It reminds me that sometimes, the most profound artistic statements come from the most unexpected places and objects, simply by reframing how we look at them. It makes me look at everyday objects in my studio a little differently – could that crumpled paint tube be art? Probably not, but the thought is there.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/gandalfsgallery/49088374138, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

From the artist's idea to their mark...

Artist Signatures: More Than Just a Name

We often look for an artist's signature, assuming it's always there and always a simple mark of authenticity. But artist signatures have their own quirky history. Some famous artists rarely signed their work, or only did so inconsistently, especially in earlier periods when art was often commissioned and the patron's status was more prominent than the artist's individual fame. Others signed in unusual places (like on a collar or a piece of paper within the painting) or used monograms or symbols instead of their full name. The practice of consistently signing and dating work became more common relatively recently in art history, as the concept of the artist as an individual genius gained prominence. Forgeries are a constant issue, making signatures a complex part of authentication, requiring expert analysis beyond just looking for a match. Artists like Rembrandt famously changed their signature over their career, adding another layer of complexity. Albrecht Dürer's prominent monogram is another well-known example of a non-name signature. A quirky example? James McNeill Whistler used a butterfly signature, sometimes incorporating a stinger, reflecting his personality and aesthetic philosophy. As an artist, signing my work feels like a final, personal touch, a little stamp of 'me' on the piece. It's a small ritual, a moment of completion. But knowing the history, it makes me appreciate that the relationship between artist and signature hasn't always been so straightforward. It's another layer of the human story behind the art, sometimes a clear declaration, sometimes a subtle hint, sometimes absent entirely. It makes me wonder if I should develop a quirky symbol instead of just my name... though honestly, remembering to sign at all can be a challenge sometimes!

Speaking of authenticity and value... what about fakes?

The Art of the Fake: Notorious Forgeries

The high value and desirability of art have, perhaps inevitably, led to a fascinating and sometimes scandalous history of forgery. Art forgery isn't just about copying a painting; it often involves creating a convincing backstory, fabricating provenance, and understanding the artist's life and techniques intimately. Some forgers become incredibly skilled, able to fool even experts for a time. Think of Han van Meegeren, who forged Vermeer paintings in the 1930s and 40s, even selling one to the Nazi leader Hermann Göring. His forgeries were so convincing that when he was arrested after the war for collaborating with the Nazis (by selling Dutch cultural property), he had to paint a 'new' Vermeer in court to prove he was a forger, not a traitor! Or the case of Wolfgang Beltracchi, a German forger active for decades, whose sophisticated forgeries of early 20th-century masters like Max Ernst and Heinrich Campendonk flooded the market and were included in museum collections before being exposed. The stories behind these fakes are often as dramatic as the art itself, highlighting the complex interplay of expertise, greed, ego, and the subjective nature of value in the art world.

Modern technology has added a new layer to this cat-and-mouse game. Scientific analysis like pigment analysis, X-ray fluorescence, and carbon dating can reveal inconsistencies in materials or age that weren't detectable by eye, making it harder for forgers to use historically accurate materials. However, forgers also adapt, using period canvases or even incorporating tiny amounts of modern pigments strategically. It's a constant technological arms race. It makes me wonder about the line between imitation and creation, and how much of our appreciation is tied to the 'authentic' hand of the artist versus the visual experience itself. It's a reminder that even the art world has its con artists and thrilling mysteries. As an artist, the idea of someone copying my work is... well, it's unlikely to be worth forging, but the principle is fascinatingly twisted.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/ciaomilano/14224092656/, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

From the meticulous work of forgers to the sometimes less-than-meticulous habits of genuine artists...

Eccentric Habits of Famous Artists

Artists are often seen as eccentric, and sometimes the reality lives up to the stereotype. These quirks aren't just random oddities; they often seem tied to their creative process or worldview. Here are a few:

- Salvador Dalí: The master of Surrealism, famously had many bizarre habits, including sleeping with a key in his hand over a plate – if he fell asleep too deeply, the key would drop and wake him with a clatter, allowing him to capture fleeting dream images before they vanished. A practical method for tapping into the unconscious, perhaps? He also gave lectures in a diving suit and once filled a limousine with cauliflowers. Just... Dalí being Dalí.

- Francis Bacon: His studio was legendary for its chaotic, paint-splattered mess, a deliberate environment he claimed fueled his creativity by providing visual stimulation and a sense of controlled chaos. He needed that visual noise to work.

- Claude Monet: The quintessential Impressionist, was famously obsessed with his garden at Giverny, meticulously designing and tending it as a source of inspiration for his later works, particularly the water lilies. He even had gardeners manage the water lily pond to his precise specifications – talk about controlling your subject matter!

- Frida Kahlo: Surrounded herself with pets, including monkeys, parrots, and dogs, which often appeared in her self-portraits and were clearly a vital part of her emotional and creative life. Her animal companions were her muses and confidantes.

- Egon Schiele: Was known for his intense, often contorted self-portraits, exploring his own body and psyche in ways that were considered highly unusual and provocative at the time. He turned introspection into a public performance, often drawing himself in awkward or vulnerable poses.

- Georgia O'Keeffe: Deeply connected to the landscape of New Mexico, she often collected bones and other natural objects from the desert, bringing them back to her studio to study and incorporate into her work. This intense focus on natural forms, particularly bones, became a signature element of her art, reflecting her profound relationship with the environment.

These stories, while perhaps exaggerated over time, add to the mystique and remind us that the creative process isn't always neat and tidy, or even conventionally 'normal'. It makes me feel slightly better about the state of my own studio sometimes! It's a peek into the unique ways different minds approach the challenge of making something from nothing, often blurring the lines between life and art. It makes me wonder what my own quirky habits are... probably just drinking too much coffee and staring blankly at a canvas for hours.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/21022123@N04/15694508911, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Art in Unexpected Places: Beyond the Gallery Walls

When we think of art, we often picture museums and galleries. But art pops up in the most unexpected places, sometimes deliberately placed, sometimes just... happening. Think of street art and graffiti, transforming urban landscapes into vibrant, often temporary canvases. Artists like Banksy (again!) or Shepard Fairey use public spaces to make statements, challenge norms, or simply add beauty. But it's not just large-scale murals. You can find small installations tucked away in alleyways, sculptures appearing overnight in parks, or even temporary performances in public squares. Temporary public art installations or land art that interacts directly with the environment, like a sculpture made of ice that melts or a pattern mowed into a field, are fantastic examples of art existing outside traditional venues, often for a limited time. I love stumbling upon art when I'm not expecting it – it feels like a little secret gift from the universe.

Beyond the street, art is increasingly found in cafes, restaurants, hotels, and even retail spaces. These aren't always formal exhibitions, but curated selections that enhance the atmosphere and give emerging artists a platform. It democratizes art, bringing it into our daily lives outside of dedicated cultural institutions. It reminds me that art isn't confined to white walls; it's a living, breathing part of the world, ready to surprise you around any corner. It makes me think about where my own art might end up – maybe not in the Louvre, but perhaps brightening someone's favorite coffee shop?

https://freerangestock.com/photos/152787/a-colorful-graffiti-on-a-building.html, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

Bizarre Commissions and Patron Requests

Throughout history, artists have often worked on commission, creating pieces for wealthy patrons, religious institutions, or governments. And sometimes, those patrons had... unusual requests. While many commissions were straightforward portraits or historical scenes, others were downright strange. Imagine being asked to paint a portrait of a beloved pet monkey in elaborate clothing, or to create a sculpture that also functions as a bizarre fountain. Some patrons demanded specific, often obscure, mythological or allegorical scenes that required extensive research or interpretation. Others were incredibly demanding about materials, like the insistence on expensive Ultramarine we discussed earlier. There are tales of patrons dictating everything from the composition to the artist's working hours. One famous (and possibly apocryphal) story involves a Renaissance patron who insisted the artist include a tiny, anatomically correct depiction of a specific mole on their back in a grand fresco! Another anecdote tells of a patron demanding a painting that would perfectly match the specific shade of green of their favorite dress, requiring the artist to mix custom pigments repeatedly. Or how about the story of a wealthy eccentric who commissioned an artist to paint a series of portraits... of his collection of prize-winning giant pumpkins, each depicted with the same gravitas and detail usually reserved for royalty? It makes me appreciate the relative freedom contemporary artists have, even with the pressures of the market. The idea of a patron demanding I paint their cat wearing a tiny hat is... well, I'd probably do it, but I'd definitely write about it later. It highlights the complex, often power-imbalanced relationship between the creator and the buyer throughout history.

https://itoldya420.getarchive.net/amp/media/an-architectural-capriccio-with-figures-by-a-colonnaded-portico-630f09, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/

Artists and Pseudonyms: Hiding in Plain Sight

While many artists proudly sign their work with their own name (or a variation, as we saw), some have chosen to work under pseudonyms or even anonymously. The reasons vary: protecting their identity for political or personal reasons (like street artists), creating a distinct persona separate from their 'real' life, or simply for the sheer fun or mystery of it. The most famous example today is arguably Banksy, whose anonymity is central to his mystique and allows him to operate outside the traditional art world structure. But historically, artists might use pseudonyms to distance themselves from a particular style, to work in a genre considered less 'serious', or even to allow multiple artists to work under a single 'brand'. It adds another layer of intrigue to the art world – who is the person behind the work? Does it matter? As an artist, the idea of creating under a different name is appealing sometimes, a way to experiment without the baggage of my established identity. But then, who would get the credit? It's a quirky thought experiment.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/man-making-art-14377465/, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/

Art and Animals: More Than Just Pets

We touched on Frida Kahlo's animal companions, but the relationship between art and animals goes much deeper and stranger. Animals have been subjects, symbols, and even collaborators or materials in art throughout history. Think of the detailed animal studies by Renaissance masters like Albrecht Dürer, capturing the natural world with scientific precision. The study of animal forms and anatomy has been a crucial part of artistic training and inspiration for centuries, from Renaissance sketches to modern wildlife art. Or the symbolic animals in medieval tapestries and religious paintings. Moving into more quirky territory, the Blue Rider group (Expressionism), particularly Franz Marc, famously used animals to represent spiritual or emotional states, painting horses blue (Blue Horse I) or cows yellow, assigning specific colors symbolic meaning related to the animal's essence. Marc saw animals as more pure and spiritual than humans, and his vibrant, non-naturalistic colors were meant to convey their inner life. Then there's the truly bizarre, like the aforementioned Mummy Brown pigment. Beyond pigments, animal products have historically been fundamental to art materials – think of bone black pigment (made from charred animal bones), brushes made from animal hair, or vellum (treated animal skin) used as a surface for manuscripts and drawings. Or even contemporary artists who incorporate live animals into installations (often controversially, raising ethical questions), or use animal products in unexpected ways. It makes you look at a simple depiction of an animal and wonder about the layers of meaning, history, or even strange materials involved. As an artist, I find the energy and form of animals incredibly inspiring, though I'll stick to paint and canvas for now – no live chickens in the studio! It's a reminder of the deep, sometimes uncomfortable, historical link between art creation and the natural world.

rawpixel.com, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

Bizarre Art Events and Performances

Beyond the formal gallery opening, the art world has a rich history of strange, shocking, or downright bizarre events and performances designed to challenge, provoke, or simply entertain. We mentioned the Dada Cabaret Voltaire, a hub of chaotic, multi-disciplinary performances. But consider Yves Klein's Anthropometries (late 1950s), where female models covered in blue paint made imprints of their bodies on canvas in front of an audience, accompanied by a small orchestra playing a single note for 20 minutes, followed by 20 minutes of silence. Or Chris Burden's Shoot (1971), where he arranged for a friend to shoot him in the arm with a rifle in a gallery setting – a performance piece exploring vulnerability and violence that remains highly controversial. More recently, artists have staged elaborate, often absurd, public interventions or created temporary, site-specific works that exist only for a brief time. These events push the boundaries of what art can be, often blurring the lines between art, life, and spectacle. They make me think about the performance aspect of even showing my own work – the anxiety of the opening, the interaction with viewers... maybe it's all a subtle form of performance art?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rocking_chairs,_21st_Century_Museum_of_Contemporary_Art.jpg, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0

Art and Food: A Strange Pairing

Food and drink appear frequently in art, from lavish still lifes depicting banquets to symbolic representations in religious works. But sometimes, the relationship gets a little... weird. Artists have used food as material, like Dieter Roth's works incorporating cheese, chocolate, or other organic materials designed to decay over time, exploring themes of mortality and transformation. Or Claes Oldenburg's giant, soft sculptures of everyday food items like hamburgers and ice cream cones, transforming the mundane into monumental, often humorous, art. There's also the performance aspect, like Marina Abramović and Ulay's Relation in Time (1977), where they sat back-to-back for 16 hours, their hair tied together, without food or water, pushing physical and mental limits. And let's not forget the simple act of artists depicting food in unusual or symbolic ways, making us look at something as common as a piece of fruit with new eyes. It makes me wonder about the snacks in my own studio – could that half-eaten apple be a future masterpiece? Probably not, but it's a fun thought.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/

Art and Technology: From Camera Obscura to AI

Art has always intersected with the technology of its time, but some moments are particularly quirky or revolutionary. Before photography, artists used tools like the camera obscura (a darkened box with a lens that projects an image onto a surface) or the camera lucida (a prism-based drawing aid) to help with perspective and accuracy. While not strictly 'art', these were technological tools that influenced artistic practice. The invention of photography itself was initially met with skepticism by some in the art world – was it truly art, or just a mechanical reproduction? Artists like Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy quickly embraced photography, experimenting with techniques like photograms (placing objects directly on photographic paper) to push its artistic boundaries. More recently, we've seen the rise of digital art, video art, interactive installations, and now, art created with the help of Artificial Intelligence. These technologies challenge traditional notions of skill, authorship, and even the physical form of art. And let's not forget the recent, often controversial, explosion of NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) as a way to represent ownership of digital art on the blockchain, adding a whole new layer of complexity to value and authenticity in the digital space. It makes me think about the tools I use today – my digital drawing tablet, the software I use for planning... are they just tools, or are they subtly shaping my creative process in ways I don't fully understand? The intersection of art and technology is constantly evolving, and who knows what bizarre forms it will take next?

https://www.flickr.com/photos/42803050@N00/31171785864, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/

The Human Story Behind the Masterpiece

These facts, from the struggles of a genius like Van Gogh to the bizarre materials, strange thefts, notorious forgeries, eccentric habits, hidden identities, unexpected locations, unusual commissions, animal connections, bizarre events, food experiments, or technological intersections of art, all point to one thing: art is deeply, wonderfully human. It's not just about the finished product hanging on a wall; it's about the person who made it, their life, their struggles, their quirks, and the world they lived in. It's about the people who loved it, stole it, wrote letters to it, or were scandalized by it. Every artwork has a story, often many stories, that go far beyond the canvas. Looking at art with this perspective, seeking out the surprising human elements, can make the experience so much richer and less intimidating. It transforms a static object into a dynamic narrative, connecting us across centuries to the minds and lives of others. So next time you're in a gallery or looking at a picture online, remember the weird, wonderful, surprising history behind it. Let these stories be your secret handshake into the art world, a reminder that it's filled with fascinating people and unexpected tales. And maybe, just maybe, you'll feel that connection too, that sense of shared humanity that transcends time and medium. As an artist, sharing these stories feels like sharing a bit of my own world, a world where the unexpected is often the most interesting part, and where every brushstroke, every idea, every choice of material, carries echoes of the strange and wonderful history that came before. Go find your own quirky art facts – they're out there, waiting to be discovered. What unexpected art story will you uncover next?

Want to see some art made by a real, quirky artist? Check out my art for sale or visit my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch. You can also learn more about my journey as an artist.