Who is the Father of Modern Art? A Personal Exploration of a Revolution

Okay, let's dive into one of those questions that art history buffs (and maybe even casual museum-goers like you and me) love to ponder: Who is the father of modern art? It sounds simple, right? Like there's one guy, probably with a dramatic beard and a paint-splattered smock, who woke up one morning and said, "Right, let's invent modern art!" But, as with most things worth thinking about, it's a lot more complicated and, frankly, a lot more interesting than that. This article isn't just about naming a single figure; it's about exploring why the question is complex and highlighting the key artists who collectively ignited a revolution that changed art forever.

My own journey into art, starting with just putting paint on canvas and eventually leading to selling my own work, has taught me that art movements aren't born in a vacuum. They bubble up, often messy and misunderstood at first, from the collective energy of artists pushing boundaries. So, the idea of a single "father" feels a bit... neat. Too neat for the glorious chaos that was the birth of modern art. It's more like a complex family tree with many influential ancestors, some acknowledged, some less so. It makes me think about my own process – sometimes a breakthrough feels like a sudden spark, but really, it's the culmination of countless hours of experimentation and frustration, building on everything that came before.

Why "Father" is a Tricky Term Here: A Revolution, Not a Single Birth

First off, let's unpack that word "father." In art history, it often implies a singular, foundational figure who directly spawned a new era. Think Giotto for the Renaissance, maybe? But modern art wasn't a single birth; it was more like an explosion of ideas, techniques, and philosophies that happened over several decades, roughly from the mid-19th century through the early 20th century. It was a rebellion against the established norms of academic art, a shift in focus from depicting the world as it was seen (or idealized) to depicting it as it was felt or as it could be imagined. It was less about perfect realism and historical scenes and more about capturing fleeting moments, exploring subjective experience, and experimenting with form, color, and composition.

But what exactly was this academic art they were rebelling against? Imagine a system where art was dictated by strict rules, focusing on idealized beauty, historical or mythological subjects, and a highly polished, invisible brushstroke. This was the world of the official Salon, controlled by powerful institutions like the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Salon held immense power, determining artists' reputations and livelihoods through its exhibitions and awards. To be rejected by the Salon was often professional death. The artists we'll discuss were the ones rattling that cage, often exhibiting independently or in smaller, controversial shows.

Why did this revolution happen then? The mid-19th century was a time of immense change. Industrialization was transforming cities and daily life, new technologies like photography were challenging painting's traditional role, and social structures were shifting. The rise of the bourgeoisie created a new class of patrons less tied to traditional aristocratic tastes, allowing artists more freedom to explore new subjects and styles outside the rigid Salon system. Artists were reacting to this rapidly changing world, seeking new ways to represent their experiences and perceptions that the rigid academic system couldn't accommodate.

This revolutionary period didn't just appear out of nowhere. You could even look back to figures like Goya, whose later, darker works like the Black Paintings hinted at a departure from classical ideals and explored psychological depth, or Turner, who dissolved form in atmospheric studies, as artists who were already nudging the boundaries. Even someone like Honoré Daumier, known for his caricatures and lithographs depicting everyday Parisian life and social issues with raw honesty, challenged academic norms by elevating the mundane and the contemporary. You could also point to the Barbizon School of painters, who moved outdoors to paint landscapes directly from nature, a small but significant step away from studio-bound academic practice. These were the early tremors before the earthquake.

A pivotal moment was the Salon des Refusés in 1863. Emperor Napoleon III, faced with the sheer volume of works rejected by the official Salon jury and public outcry, decreed that the rejected artists could exhibit their work in a separate exhibition. This wasn't an act of support, but rather an attempt to appease the crowds and perhaps ridicule the rejected art. Instead, it became a landmark event, providing a platform for the avant-garde and solidifying the divide between the traditionalists and the innovators. Manet's controversial Luncheon on the Grass was a central piece in this exhibition, drawing both outrage and attention, and serving as a rallying point for younger artists like Whistler, Pissarro, and Jongkind, who also exhibited there. It wasn't just Manet; it was a collective statement of defiance.

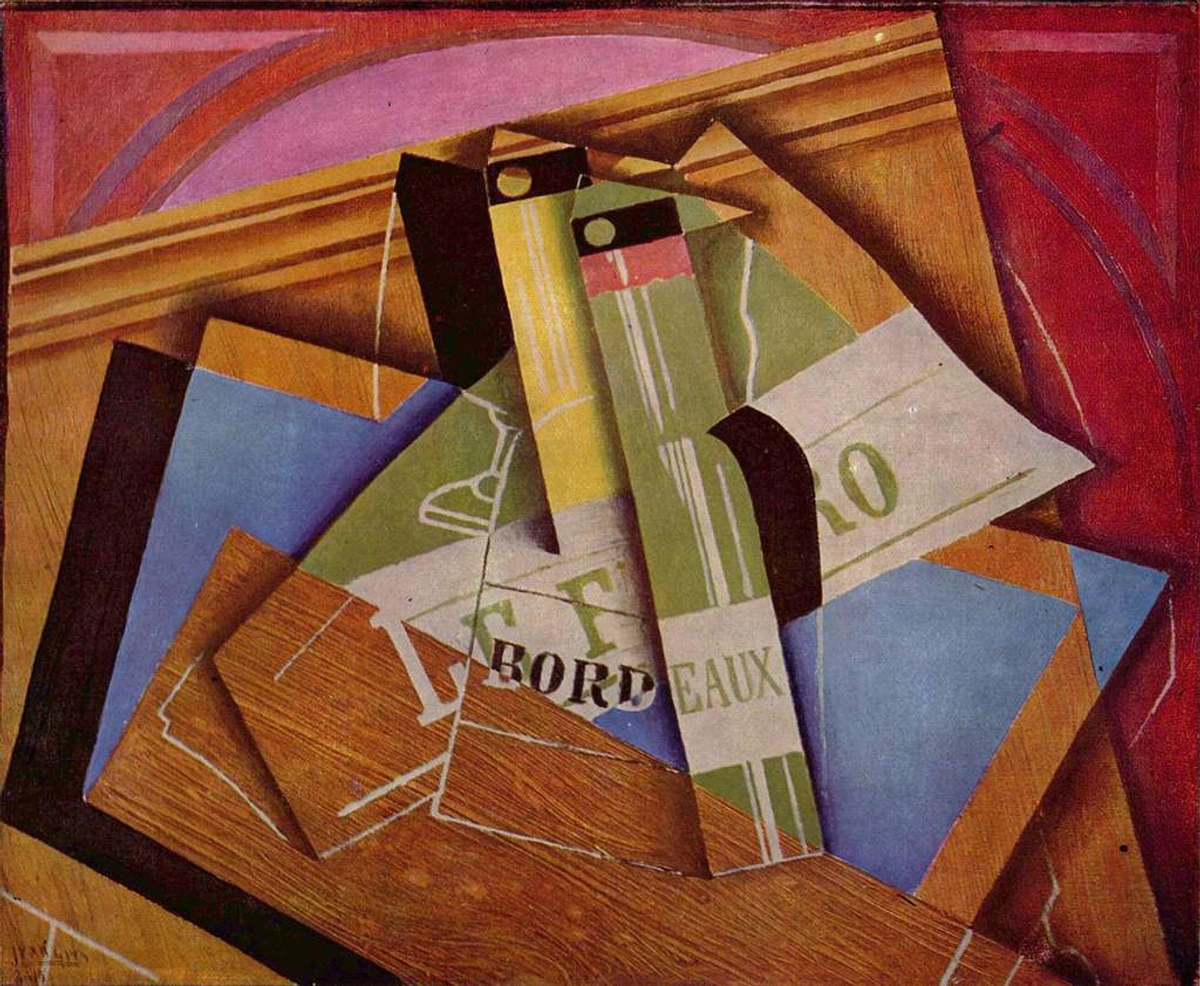

It was, in short, a revolution. And revolutions rarely have just one leader. (Though they often have key instigators! Think of the critics who championed them, like Charles Baudelaire or Émile Zola who initially supported Manet, or the dealers like Paul Durand-Ruel who dared to show the Impressionists outside the Salon.) This period also saw the increasing influence of non-Western art on European artists, adding another layer to the complex mix of influences that fueled this shift. For example, Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) influenced Impressionist composition (cropping, flattened perspective) and color palettes, while African masks and sculpture profoundly impacted the development of Cubism's fragmented forms, notably seen in Picasso's groundbreaking Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. It's fascinating how ideas travel and cross-pollinate, isn't it? Like finding unexpected connections between seemingly disparate things in your own creative process.

And let's not forget the rise of photography. Suddenly, the camera could capture reality with a precision painting couldn't match, freeing artists to explore what painting could do beyond mere representation – focusing on light, emotion, and abstract ideas. Photography also influenced composition, leading artists to experiment with asymmetrical arrangements and cropped perspectives, much like a snapshot. It also captured the fleeting moment with undeniable accuracy, pushing painters like the Impressionists to find new ways to render movement and transient effects of light and atmosphere.

If you're curious about what exactly constitutes this revolutionary period, I've got a whole guide on what is modern art and its fascinating history.

The Usual Suspects: Key Instigators of the Revolution

Okay, so if there's no single 'father,' who were the absolute game-changers? Who were the ones really shaking things up and laying the groundwork for everything that came after? It's like trying to pick the single most important ingredient in a complex stew – you can, but you miss the richness of the whole thing. Still, some figures were undeniably more... disruptive than others. Let's look at a few key players who fundamentally challenged the status quo and paved the way for the 20th century.

Gustave Courbet: The Grumpy Realist Uncle

Let's start with Gustave Courbet. While maybe not the father of modern art, he was definitely the grumpy uncle who showed up and refused to play by the rules. His Realism movement in the mid-19th century was a direct challenge to the idealized, historical, or mythological subjects favored by the official Salon. Courbet insisted on painting everyday life, ordinary people, and unvarnished reality – scandalous stuff back then! His monumental scale for everyday subjects, like in A Burial at Ornans, was a radical departure. Why? Because traditionally, only grand historical or religious scenes were painted on such a large scale. Applying that scale to a common funeral elevated the mundane to the level of the heroic, a truly revolutionary act that declared, "This life, our life, is worthy of grand art." He also used thick, visible brushstrokes (impasto), drawing attention to the paint itself, not just the illusion it created. He set a precedent for artists to depict the world around them, not just some imagined, perfect version. Think of his painting The Stone Breakers – two ordinary laborers depicted with the same gravitas previously reserved for kings or saints. It was a shock to the system. As an artist myself, I can appreciate the sheer nerve it took to say, "No, this is important," when everyone else was looking the other way. It reminds me that sometimes the most powerful statements in art are the simplest ones, just showing things as they are, without embellishment.

Édouard Manet: The Grenade Thrower

Then there's Édouard Manet. Ah, Manet. The guy who basically threw a grenade into the art world. Building on Courbet's focus on modern life, he combined it with techniques that shocked the establishment. His paintings, like Luncheon on the Grass or Olympia, featured contemporary figures, sometimes nude, looking directly at the viewer, challenging conventions of perspective and finish. He used flatter planes of color and visible brushstrokes, which felt unfinished and crude to academic eyes. This wasn't just sloppy; it was a deliberate choice that drew attention to the act of painting itself, not just the illusion of reality. Manet didn't set out to start a movement, but his controversial work became a rallying point for younger artists who would become the Impressionists. His direct gaze in Olympia, depicting a contemporary prostitute, was particularly scandalous, forcing viewers to confront modern reality head-on. That kind of directness, that refusal to look away, is something I constantly strive for in my own work, even in abstract art. It's about honesty, even when it's uncomfortable.

The Impressionists: Capturing the Fleeting Moment

![]()

The Impressionists, including giants like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, took Manet's lead and ran with it, focusing on capturing the fleeting impression of a moment, particularly the effects of light and color outdoors. Their emphasis on plein air painting (painting outdoors) and visible, broken brushwork was revolutionary. They used unblended dabs of pure color placed side-by-side, allowing the viewer's eye to mix them optically, creating a vibrant, shimmering effect. While the theory was optical mixing, the reality is that the texture and vibrancy of the unblended paint itself also contribute significantly to the visual impact. Think of Monet's Impression, soleil levant (which gave the movement its name) or his later Water Lilies series – it's all about the subjective experience of light and atmosphere. They weren't trying to paint a tree; they were trying to paint the light hitting the tree at that specific moment. While their focus was still largely on the visible world, their emphasis on subjective perception and the act of seeing itself was a crucial step away from strict academic representation. Notable women artists like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt were also integral to the Impressionist movement, pushing boundaries alongside their male counterparts. If you've ever tried to capture the exact color of light at a specific time of day, you'll understand the Impressionists' obsession. It's maddeningly difficult, and their dedication was incredible. You can dive deeper into their world with this ultimate guide to Impressionism.

The Post-Impressionists: Pushing Beyond Impressionism

Following the Impressionists came the Post-Impressionists, a diverse group who built upon Impressionism but pushed in different directions. It's important to note that "Post-Impressionism" wasn't a formal movement they belonged to, but a term coined later to group artists who reacted to Impressionism while retaining some of its innovations, like brighter palettes and a focus on subjective experience. They reacted against what they saw as Impressionism's limitations, such as a lack of structure or emotional depth.

Key figures include:

- Vincent van Gogh: Explored emotional expression through swirling brushstrokes and intense, symbolic color, as seen in his iconic Starry Night. His use of color wasn't just about light; it was about conveying feeling. How artists use color for emotional impact is something I think about constantly. It's like trying to paint a feeling, which is much harder than painting a thing.

- Paul Gauguin: Sought symbolic meaning and flattened forms, heavily influenced by non-Western art (particularly art from Tahiti and other Polynesian cultures he encountered) during his time abroad, moving towards more decorative and expressive uses of line and color. His works like Vision After the Sermon show this move towards symbolism and non-naturalistic color to convey spiritual or emotional states.

- Paul Cézanne: Arguably the artist most frequently cited as the bridge to truly modern art, particularly abstract art. He wasn't just interested in the impression of light; he was obsessed with the underlying structure of forms. He would paint the same subject (like Mont Sainte-Victoire or a bowl of apples) repeatedly, exploring how to render three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional canvas by breaking them down into basic geometric shapes (cylinders, spheres, cones) and showing multiple viewpoints simultaneously. This technique, sometimes called 'passage' where forms bleed into one another, challenged traditional perspective. It's like he was trying to show you the object from all sides at once, flattened onto the canvas. Think of looking at a bottle – you know it's round, even if you only see one side. Cézanne tried to put that knowledge of its roundness, its underlying structure, into the painting. This analytical approach to form and space directly influenced the development of Cubism by artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who explicitly acknowledged his foundational importance. His painting Mont Sainte-Victoire series clearly shows this process of breaking down the landscape into geometric facets. You can explore this further in the ultimate guide to Cubism.

When I look at a Cézanne, I don't just see a landscape or a still life; I see the bones of the image, the underlying architecture. It feels like he's showing you how to build a painting, not just copy something. It's a perspective that deeply resonates with my own process, constantly thinking about form and structure, even in abstract work. You can see echoes of this structural thinking in everything from abstract art to composition basics.

- Georges Seurat: Also pushed Impressionism in new directions, developing Pointillism (or Neo-Impressionism), using tiny, distinct dots of pure color applied in patterns to form an image, based on optical theories. His monumental A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte is the most famous example, applying scientific rigor to the Impressionist study of light and color. You can learn more in the ultimate guide to Pointillism.

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Captured the energy of Parisian nightlife with flattened forms and bold lines, influencing graphic design and showing another facet of modern life ripe for artistic exploration.

The Legacy: Paving the Way for the 20th Century and Beyond

The groundwork laid by these pioneers didn't just stop there. Their innovations directly fueled the explosion of art movements in the early 20th century. The shift from Paris as the undisputed center of the art world began, with other cities like Berlin and Vienna becoming important hubs for new ideas.

While figures like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse are often the first names that come to mind when thinking of modern art, they are more accurately described as the revolutionary sons or grandsons of the movement. They built directly upon the foundations laid by the Post-Impressionists, taking those initial breaks from tradition and pushing them into entirely new territories. They didn't start the revolution, but they certainly escalated it dramatically.

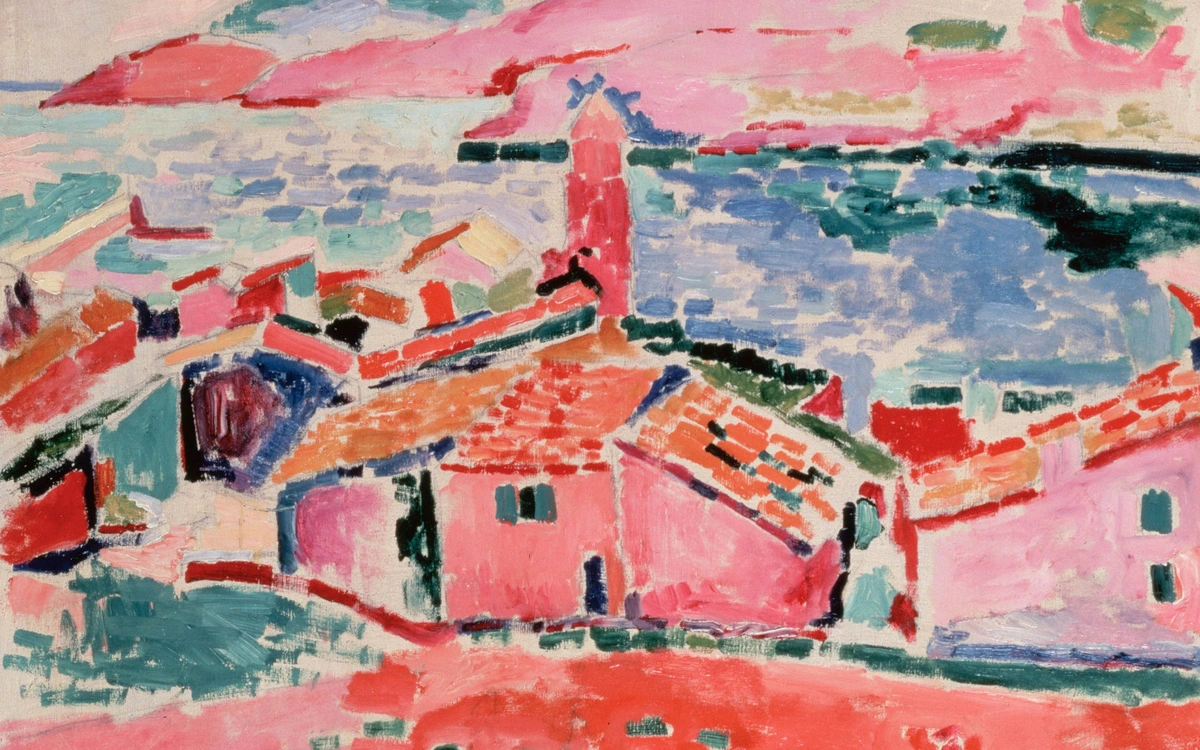

- Fauvism, led by artists like Henri Matisse, took the expressive use of color seen in Van Gogh and Gauguin and pushed it to new, non-representational extremes, using color for its emotional impact rather than descriptive accuracy. This was revolutionary because color was freed from its traditional role of describing the visible world; it became an autonomous element used to convey feeling and structure the composition. Think of the vibrant, almost jarring palettes in Matisse's work, like View of Collioure. You can explore this wild use of color in the ultimate guide to Fauvism.

- Cubism, spearheaded by Picasso and Braque, took Cézanne's analysis of form and space to its logical conclusion, fragmenting objects and depicting them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously within a single image. This radical departure from traditional representation opened the door for almost all subsequent abstract art. It was like shattering reality and reassembling it on the canvas, showing not just what you see, but what you know about an object. You can learn more in the ultimate guide to Cubism.

These movements, and others like German Expressionism (building on the emotional intensity of Van Gogh and Munch, explore it in the ultimate guide to Expressionism), Futurism (influenced by Cubist dynamism), and eventually Surrealism (think Dalí and Magritte) and Abstract Expressionism (like Rothko, explore it in the ultimate guide to Abstract Expressionism), were direct descendants of the late 19th-century revolution. The focus shifted definitively from external reality to internal experience, formal experimentation, and the very nature of art itself. The influence of non-Western art continued to be a significant, though often uncredited, factor in many of these developments.

It's also worth remembering the initial reaction to many of these works. They were often ridiculed, called crude, unfinished, or even immoral. The public and critics accustomed to academic polish and idealized subjects were genuinely shocked and confused. This resistance highlights just how radical these artists truly were. It makes you wonder what revolutionary art is being dismissed today, doesn't it? Maybe the next 'father' figure is out there right now, being told their work is 'too messy' or 'doesn't make sense'.

The Verdict (Sort Of)

So, who is the father of modern art? If you have to pick one figure who most profoundly altered the course of painting and directly paved the way for the formal experiments of the 20th century, many art historians (and I'd lean this way too) would point to Paul Cézanne. His systematic exploration of form and space was revolutionary and deeply influential on Cubism and subsequent abstract movements.

However, it's crucial to remember that he stood on the shoulders of giants like Manet and the Impressionists, who themselves built on the challenges posed by Courbet and even earlier precursors. Modern art was a collaborative, chaotic, and thrilling birth, not a single immaculate conception. It involved artists, critics, dealers, and a rapidly changing world shaped by industrialization, urbanization, and new technologies like photography. The term "modern art" itself is vast and encompasses a huge range of styles and ideas, making a single "father" even less likely.

Here's a quick summary of the key contenders and their main contributions:

Artist/Movement | Key Contribution to Modern Art | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gustave Courbet | Realism, depicting everyday life on a grand scale, visible brushwork (impasto). | |||

| Édouard Manet | Bridging Realism and Impressionism, challenging academic finish and subject matter, flat forms. | |||

| Impressionism | Capturing fleeting moments, effects of light, plein air painting, broken color. | |||

| Post-Impressionism | Diverse explorations: emotional color (Van Gogh), symbolism/form (Gauguin), structure (Cézanne), optical theory (Seurat). | n | Paul Cézanne | Analyzing form into geometric shapes, multiple viewpoints, structural approach to painting (passage). |

These artists didn't just change what art looked like; they changed how artists thought and what art could be about. Their collective impact is far greater than any single individual's.

For me, as an artist, this history isn't just trivia. It's a reminder that pushing boundaries, questioning how we see and represent the world, and building on the innovations of others is the heart of artistic progress. It's a legacy that continues to inspire, whether you're visiting a modern art museum (maybe even my favorite, the Den Bosch Museum in the Netherlands, which has some great modern pieces) or just trying to make something new in your own studio. It's a conversation that's still happening, and we're all invited to join in. Maybe you'll find your own connection to this history the next time you're exploring a gallery or even just looking closely at the world around you. It's all part of the same messy, wonderful journey. You can even see how these historical movements influence contemporary art today and the work of painters of today.